Abstract

Primates are an important source of infectious disease in humans. Strongyloidiasis affects an estimated 600 million people worldwide, with a global distribution and hotspots of infection in tropical and subtropical regions. Recently added to the list of neglected tropical diseases, global attention has been demanded in the drive for its control. Through a literature review of Strongyloides in humans and non-human primates (NHP), we analysed the most common identification methods and gaps in knowledge about this nematode genus. The rise of molecular-based methods for Strongyloides detection is evident in both humans and NHP and provides an opportunity to analyse all data available from primates. Dogs were also included as an important host species of Strongyloides and a potential bridge host between humans and NHP. This review highlights the lack of molecular data across all hosts—humans, NHP and dogs—with the latter highly underrepresented in the database. Despite the cosmopolitan nature of Strongyloides, there are still large gaps in our knowledge for certain species when considering transmission and pathogenicity. We suggest that a unified approach to Strongyloides detection be taken, with an optimized, repeatable molecular-based method to improve our understanding of this parasitic infection.

This article is part of the Theo Murphy meeting issue ‘Strongyloides: omics to worm-free populations’.

Keywords: Strongyloides, primates, microscopy, molecular methods

1. Introduction

Due to their close phylogenetic relationship [1], pathogens are easily transmitted between humans and other primates, especially great apes [2]. Over 60% of infectious organisms known to be pathogenic to humans have an animal origin (are zoonotic) [3], and the origin of many human pathogens is in non-human primates (NHP). Although primates constitute a minority within the mammalian diversity, they are the original source for 20% of agents of human infectious diseases [4]. Notorious cases are among viruses, as major human viral diseases such as AIDS [5] and hepatitis B originate in NHP [6], and NHP also play a role as reservoirs for agents of other serious infections such as Ebola, yellow fever and monkeypox [7]. In addition to viruses, human parasites are evolutionarily linked to those in NHP. For example, Plasmodium falciparum, the most important parasite in humans [8], has been found to originate in the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) [9]. On the other hand, human pathogens can have devastating effects on endangered populations of NHP. Respiratory diseases caused by pneumoviruses and paramyxoviruses [10], or tuberculosis [11] and measles [12] have been responsible for morbidities and mortalities of free-ranging and captive animals. While humans and NHP have always had some degree of contact in areas where they overlap [13], increased anthropogenic pressure from altered landscape use and subsistence activities [14] has resulted in an increased incidence of human–NHP contacts, consequently resulting in increased infection risk not only for humans but also for NHP populations [15].

Neglected parasites, including several soil-transmitted nematodes, are frequently transmitted between humans and NHP [16–19]. Rhabditid nematodes of the genus Strongyloides are among the most common soil-transmitted nematodes in both humans and NHP [16,20]. The genus Strongyloides includes over 50 species, of which three species are capable of establishing infection in humans. Strongyloides stercoralis has a cosmopolitan distribution and infects a broader range of hosts, including primates and carnivores [21]. Two lineages within S. stercoralis were established based on the molecular analyses: lineage A is probably zoonotic and occurs in humans, mainly in captive NHP and dogs, while the lineage B is probably restricted to dogs only [17,22]. In Africa and Asia, occasional infections by Strongyloides fuelleborni in humans are reported. The species was formally further classified into two subspecies. Strongyloides f. fuelleborni occurs in African and Asian NHP, with occasional transmission events to humans, while S. f. kellyi is endemic to Papua New Guinea (PNG) and infects humans only [23,24]. Although eggs of Strongyloides sp. have been found in human stool in the Indonesian part of New Guinea [25], they have never been proven to be from the same Strongyloides as in PNG, and furthermore, there is no report of it causing acute infantile disease as in PNG [23]. The classification of S. f. kellyi as a subspecies of S. fuelleborni was based on morphological and a separate isoenzyme electrophoretic result, which were not sufficiently different to warrant a specific distinction [26]. By contrast, the phylogenetic analyses did not group S. f. kellyi together with S. f. fuelleborni, suggesting that S. f. kellyi should be elevated to a species rank [27]. Adhering to this taxonomic concept, we use S. fuelleborni for infections in humans and NHP in Africa and Asia, with the exception of infections in humans in PNG, which are referred to as S. kellyi. Both S. stercoralis and S. fuelleborni are shared by humans and NHP, but there are more Strongyloides species recorded from NHP that have not yet been recorded in humans.

2. Strongyloides in non-human primates

Strongyloides infections are commonly reported in free-ranging and captive NHP on all continents except for Antarctica and Australia, although it is possible that captive primates in Australia are infected, and we are just missing the data. Unfortunately, a large proportion of studies report only the genus Strongyloides without specified species, often even without note for whether the observed stages were eggs or larvae. Undoubtedly, some of these findings are misidentified embryonated eggs of strongylid nematodes.

Strongyloides fuelleborni, first described by Von Linstow [28] in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) in Africa, is the most common Strongyloides species found in African and Asian primates (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Strongyloides simiae was described in Asian macaque (Macaca sp.) based on assumed morphological differences from S. fuelleborni [29]. However, only a couple of years later, it was concluded that the morphological traits of S. simiae are not sufficient for its recognition as a valid species [30,31]. Later authors further confirmed the conspecificity of S. fuelleborni and S. simiae [32,33]. Since then, S. simiae is considered a junior synonym of S. fuelleborni, which therefore remains the only oviparous species in Old Word NHP [33]. Analyses of the cox1 sequences obtained from both African and Asian NHP show S. fuelleborni as a monophyletic, but quite highly diverse group [21]. At least two subclades—African and Indochinese peninsular clades—that may represent distinct species are distinguished [34]. Observed differences are rather connected to geographical distribution than to host species identity [21,35–37] and the geographically defined haplotypes can be shared among the sympatric primate species [38]. Historically, crossbreeding experiments with different strains of Strongyloides from chimpanzee, rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), tufted capuchin (Sapajus apella) and dog were performed [39]. No hybridization occurred, which led to the suggestion that strains from Asia, Africa and South America should be recognized as separate species. Nowadays, the South American Strongyloides is indeed treated as a separate species S. cebus. Nevertheless, Asian and African isolates are still referred to as a single species and discussion about the validity of S. simiae could be revisited as there is obviously a lack of gene flow between the distant geographical regions.

Strongyloides cebus has been identified only in NHP from the New World [27,40] and to date, there are no reports of human infection with this species. It was first described in capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus) [41] and redescribed based on the morphology of parasitic females [33]. In this species, ovaries are spiralled around the intestine and lips of the vulva are prominent, the tail tapers more gradually and is more sharply pointed than S. fuelleborni [33,40]. However, S. cebus differs also in the third-stage larvae (L3) and free-living adults' morphology and therefore, this species can be identified even without the necropsy of its host [40]. Strongyloides cebus was listed in several species of New World primates in America based on morphology of adults [40], although most studies from South America only report unidentified Strongyloides eggs or larvae when microscopic examination of faecal samples was conducted [42,43]. Strongyloides cebus was characterized genetically in an unspecified NHP from South America [27] and later in captive New World NHP in Japan [44] and the USA [45]. Phylogenetic analyses of mitochondrial sequences indicated S. cebus as a species rather distant from S. fuelleborni and S. stercoralis, suggesting that it evolved independently in the Americas as a parasite specific to NHP [44].

Interestingly, both S. cebus and S. fuelleborni are also found in captive primates in zoos, commonly outside of South America [44,45] or Africa [46]. Still, S. fuelleborni is rather uncommon in zoos, and its prevalence in captive or pet animals in countries of origin was always lower than in the free-ranging counterparts [47]. Although S. cebus produces eggs shed in the host faeces without capability for endogenous autoinfections, the larvae hatch shortly after defecation [40]. This species also differs by the number of generations in the free-living cycle; there are at least two generations in S. cebus [33], although three generations with fourth-generation eggs and larvae was described [48], while only one generation is typical for S. fuelleborni [33]. This could be responsible for its long persistence, potential of re-infection and accumulation of L3 in the environment [40], which may explain the persistence in zoos animals.

Strongyloides stercoralis is mainly diagnosed in captive settings [49,50], often related to unsanitary conditions facilitating transmission from humans or other reservoir hosts. Strongyloides stercoralis is the only ovoviviparous species among-primate infecting Strongyloides, with first-stage larvae (L1) capable of endogenous autoinfection. This ability, combined with the fact that NHP are kept in closed facilities, enables S. stercoralis infections to persist in captive NHP settings for prolonged periods. Strongyloides stercoralis was molecularly confirmed in captive chimpanzees [35], as well as captive Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) and Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii) [50]. However, the presence of this species was reported also in Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania, in habituated free-ranging chimpanzees that were in contact with humans [35].

Molecular analyses revealed three cryptic and yet unnamed Strongyloides species in Bornean slow loris (Nycticebus borneanus) [38], spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) [51] and in a colony of baboons (Papio anubis, Papio hamadryas) in a research institute in Texas [52]. The cox1 sequences of Strongyloides from the loris clustered within the S. stercoralis/procyonis group [44,53], suggesting close phylogenetic relationships with these species. This clade also comprises a number of sequences of undetermined Strongyloides species found primarily in various hosts from the order Carnivora [54]. The Strongyloides sp. cox1 sequences from spider monkeys clustered closely to the S. papillosus/fuelleborni group; a monophyletic group consisting of S. fuelleborni in primates but also ruminant-infecting S. papillosus and S. vituli as well as S. venezuelensis found in rats [44]. Finally, a short (366 bp) 18S rDNA sequence from the unspecified baboon clustered in a clade comprising S. fuelleborni, S. stercoralis and a Strongyloides sp. from a snake, while the second clade comprising S. westeri, S. ratti, S. suis, S. venezuelensis, S. cebus, S. fuelleborni kellyi and S. papillosus was formed [52].

3. Transmission of Strongyloides between non-human primates and humans

Cases of S. fuelleborni infection in humans have been reported mainly in the tropics, exclusively in areas where humans share their habitat with NHP. Although human infections with S. fuelleborni have been detected in both Africa and Asia, most reports are from tropical Africa (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Strongyloides fuelleborni has been found in numerous ethnic groups, mainly in rainforest areas [55] with the highest prevalence found in hunter–gatherers. A S. fuelleborni prevalence of 25% was reported among Babinga hunter–gatherers in the Central African Republic, with children being the most commonly infected [56]. High prevalence (49%) was found also in the Bambuti hunter–gatherers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where the authors suggested that the transmission of S. fuelleborni may have occurred when the hunted monkeys were eviscerated and the gut contents contaminated areas where humans lived [16]. Persistent occurrence of S. fuelleborni in human communities inhabiting the rural areas of Africa and dominance of this species in African and Asian NHP suggests possible ongoing cross-transmission; however, further research is required to support this with molecular evidence. Following coproscopy, eggs referred to as S. fuelleborni have been found in both humans and NHP living in the Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas [57]. Possible transmission of Strongyloides spp. between humans and NHP in the same locality was investigated by analysing 18S rDNA and cox1 sequences [20], though on a limited number of larvae. Despite S. fuelleborni being found in all studied hosts, haplotypes from great apes differed from those in humans. By contrast, S. stercoralis was detected only in humans. Two studies report occurrence of S. fuelleborni in researchers who returned from Africa, where they had contact with NHP [35,58]. In the first case, the researcher returned from Tanzania, where she worked with chimpanzees [35], while the second researcher—in DRC—studied bonobos (Pan paniscus) [58], which are also known hosts of S. fuelleborni based on eggs detected in the bonobo faeces [59].

In contrast to tropical Africa, S. fuelleborni is rarely reported in Asian human populations. Using partial 18S rDNA and ITS-1, S. fuelleborni was detected in a human working closely with wild orangutans in Borneo [49]. Independent studies confirmed identical genotypes of S. fuelleborni in NHP and rural Asian human populations. People in Thailand, who have frequent contact with wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) harboured S. fuelleborni 18S rDNA and cox1 haplotypes, which were found later in wild long-tailed macaques sampled in Thailand and Laos [36,60]. Transmission was also suspected between captive pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) and their owner, as they shared the same S. fuelleborni 18S rDNA and cox1 haplotypes [37].

Similarly, transmission of S. stercoralis between captive NHP and zoo/sanctuary personnel and vice versa is very likely [21], facilitated by close contact in captive and semi-captive conditions [50]. Strongyloides stercoralis is commonly found in captive NHP in zoological gardens [50] and rehabilitation centres [49]. Strongyloides stercoralis infection was reported in wild great apes and humans sharing the same habitat in the Republic of the Congo [61]; however, this was concluded based only on a qPCR protocol using generic primers, which do not differentiate between Strongyloides species and therefore the results are highly speculative. Notably, humans as well as NHP are typically infected with S. stercoralis cox1 lineage A, for which domestic dogs could possibly be a source of infection [17]. Thus, dogs could play a role in transmission of S. stercoralis to NHP as well, especially in areas of mutual habitat encroachment or captivity.

In the case of S. cebus, there is no known transmission between NHP and humans. A volunteer was experimentally infected with larvae of S. cebus from the capuchin monkey Cebus capucinus hypoleucus, but infection was not established in humans [30]. However, successful infections with S. fuelleborni were achieved after human exposure to larvae cultured from the faeces of various Old World NHP [30,62–64].

4. Pathogenicity of Strongyloides for non-human primates

Numerous studies describe fatal cases in captive animals [65–67] and it seems that these cases have been caused exclusively by S. stercoralis or S. cebus. In humans, most infections with S. stercoralis are mild, but the infection can lead to complicated strongyloidiasis under certain conditions (e.g. immunosuppression) [68]. While uncomplicated disease is manifested by gastrointestinal, pulmonary and dermatological symptoms, infection in immunosuppressed patients can lead to severe systemic disease known as disseminated strongyloidiasis, with possible fatal consequences [69]. NHP under the age of five years appear to be most susceptible to clinical disease [49]. A lethal course of S. stercoralis infection has also been noted in young chimpanzees and gorillas at the San Diego Zoo [65] when more than a quarter of a million filariform larvae were found at autopsy in one individual in all parts of its gastrointestinal tract, in the lungs and in the urinary bladder [65]. Disseminated strongyloidiasis caused by S. stercoralis was reported in five captive common patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) [70] and fatal strongyloidiasis (identified as Strongyloides sp.) in a 5-month-old captive Sumatran orangutan [71]. By contrast, no clinical signs were observed in captive orangutans infected by S. stercoralis cox1 lineage A in Czech zoos [50]. When black-tufted monkeys (Callithrix penicillata) were subcutaneously inoculated with S. stercoralis of human origin [72], most animals showed no clinical signs but immunosuppressed individuals showed progressive disease leading to disseminated infection.

Clinical signs have also been reported in captive NHP with S. cebus infection. These included diarrhoea, weight loss, loss of appetite, dehydration and dyspnoea [40]. In fatal cases, post-mortem examination revealed inflammatory processes with a substantial presence of larvae and eggs in the pancreas, liver, heart and lungs, as well as lesions and haemorrhages in the small intestine and lungs [40].

Unlike S. stercoralis and S. cebus, asymptomatic infections with S. fuelleborni occur in free-ranging primates [21]. In experimental infections of humans with S. fuelleborni from NHPs, clinical symptoms often did not occur even though the infection was successful [30,62,63]. Infection with clinical symptoms has been described only in humans after exposure to Strongyloides larvae from gibbons [64]. Nevertheless, an apparently mild and self-limiting infection with S. fuelleborni has been described in local people in Central African Republic, who share an environment with NHP [73]. Clinical symptoms have also been observed in a person working with NHP in Tanzania [35]. In general, clinical signs, if present, are similar to those of S. stercoralis infection, such as localized skin symptoms, dry cough with possible tracheal irritation, abdominal pain and diarrhoea [73]. However, disseminated and fatal strongyloidiasis infections in humans have only been reported with S. stercoralis, which may be due to the capability of autoinfection, unknown in S. fuelleborni. While in S. stercoralis direct (homogony) and indirect (heterogony) cycles can alter, one indirect developmental cycle is necessary for S. fuelleborni [30].

5. Diagnostic methods for Strongyloides detection in primates

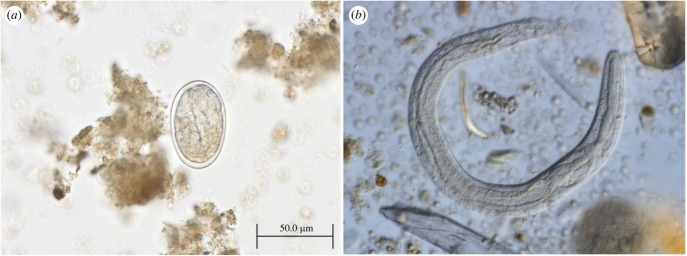

Despite fresh faecal smears being frequently mentioned in the literature (electronic supplementary material, table S1), the microscopy methods predominantly used for parasite detection in NHP are based on concentration techniques in various modifications [74]. Flotation methods commonly use sucrose, sodium nitrate and zinc sulfate solutions, while sedimentation techniques such as formalin–ethyl acetate and formalin–ether sedimentation are also employed. In contrast to diagnostics in humans, where sedimentation techniques and the Kato-Katz technique are routinely used for Strongyloides detection [75], flotation is the most commonly used method for parasite detection in veterinary medicine and, as such, predominates as a diagnostic tool for helminth detection also in captive NHP. Most quantification methods such as McMaster, FLOTAC and MiniFLOTAC© are also based on flotation. In many cases, faecal samples from NHP, especially those collected in the field, are preserved and examined later. Formalin-based preservation increases fragility of thin-walled nematode eggs that tend to rupture or collapse under high osmotic pressure in flotation solutions [57]. This is a well-documented limitation for detection of strongylid nematode eggs and applies also for the thin-walled Strongyloides eggs that can be consequently overlooked. Proper identification of the eggs of oviparous Strongyloides species represents another complication as they are commonly misidentified as the embryonated eggs of strongylids (i.e. hookworms), a factor that should be considered in any further analyses of published data. Strongyloides stercoralis larvae do not float easily, so they also cannot be detected using flotation-based techniques, stressing the need for sedimentation-based diagnostic techniques. In general, all microscopy-based methods have a very low detection rate for Strongyloides compared to the more specific methods [75] that are discussed below. Still, microscopy is the only non-molecular method that can easily distinguish S. stercoralis L1 larvae, from oval eggs containing U-shape larva in other Strongyloides species, including S. fuelleborni, S. kellyi and S. cebus in the examined faeces (figure 1). Unfortunately, neither larvoscopic nor larval culture methods are routinely used to detect parasites in NHP. Baermann larvoscopy or Koga agar plate culture are essential methods to detect the L1 larvae from fresh faeces [76], but as L1 develop within a few hours for all Strongyloides spp., this method does not provide a means for distinguishing species. Infective L3 larvae and free-living adults can be developed by culturing in sterile sawdust [77] or by using a Harada Mori filter paper culture, although distinguishing different species based on L3 larvae is impossible due to overlapping morphological characteristics. Taxonomy and species identification for Strongyloides are commonly based on the morphology of parasitic females, which are collected at the necropsy of hosts [40]. This is often impossible due to the protected status of the NHP or lack of facilities where necropsy could be safely performed. Nevertheless, despite molecular methods being prioritized, morphology-based approaches are crucial for clarifying taxonomic ambiguities and new species description. For example, in S. fuelleborni, two cox1-based lineages are formed—an African and an Asian strain [21]—suggesting that they may be two separate species, but morphological confirmation is essential for new species establishment.

Figure 1.

(a) Strongyloides fuelleborni egg from lowland gorilla faeces, Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas, Central African Republic and (b) S. stercoralis L1 rhabditiform larva from captive Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) that are both passed in the faeces.

Serological methods such as a range of ELISA tests are routinely used in humans [78]. Although these tests have relatively high sensitivity, specificity is less assured and cross-reactivity can occur in cases of coinfection with other parasites [79]. These tests are hard to apply in wild NHP, as it is not possible to obtain invasive samples such as blood, and to our knowledge serology has not been used for Strongyloides detection in captive NHP either.

A range of DNA-based diagnostic techniques that target 18S rRNA gene (18S rDNA; mainly hypervariable regions HVR-I and HVR-IV), 28S rRNA gene (28S rDNA), ITS-1 and cox1 were introduced for Strongyloides diagnostics (electronic supplementary material, table S2). A qPCR protocol based on 18S rRNA gene was developed for detection and quantification of Strongyloides at the genus level [80]. Genus-specific 28S rDNA-based loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) allows detection of Strongyloides without temperature cycling and is therefore suitable for resource-limited conditions [81]. However, none of the above methods can be used for accurate species identification without subsequent sequencing. Considering the diversity of Strongyloides species occurring in primates and their epidemiology, host spectrum and host specificity, genetic characterization should be a standard for epidemiological studies as well as for case reports. The aforementioned genetic markers are suitable for discrimination to the species level [21]. However, recent studies discovered host preferences of different S. stercoralis lineages (possibly subspecies or even cryptic species) and geographical clusters of S. fuelleborni that were detected only by certain markers [21,82,83]. Specifically, lineages A and B of S. stercoralis were discriminated by cox1, and this separation is also reflected by HVR-IV of 18S rDNA, while HVR-I clustering is rather random and thus does not represent a suitable marker [83,84]. Suitability of the remaining two markers (28S rDNA and ITS-1) for characterization of the lineages is yet to be determined. In a study from Myanmar [22], 13 28S rDNA haplotypes from dogs and humans were identified and formed two clades—human/dog and dog only, corresponding to cox1 clade I (now Lineage A) and clade II (Lineage B), respectively. However, there was a 28S haplotype H3 from the dog-only clade that was obtained from isolates that clustered in both cox1 clades I and II. The topology of the 28S rDNA tree did not show clear distinction to two separate and strongly supported clades that would reflect the cox1 topology. Therefore, this marker deserves further attention. Providing sequences of multiple loci, covering both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, is crucial for building up public databases allowing for deep analyses [34].

Conventional PCR analyses followed by Sanger sequencing are suitable for the barcoding of isolated Strongyloides larvae [20,50], but molecular identification of Strongyloides spp. from total DNA extracted from faeces or cultures, which might contain multiple Strongyloides strains and/or species, requires more complex genotyping approaches. Next generation sequencing (NGS) is an effective tool for dealing with multiple infections [83]. A genotyping assay adapted for deep amplicon sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform targeting the mitochondrial cox1 locus and 18S rDNA HVR-I and HVR-IV was designed and used for sequencing multiple Strongyloides haplotypes in faecal samples from different hosts, including humans [83] and NHP [46], but such methods await their use in epidemiological studies aimed at detecting transmission of Strongyloides species between humans and NHP. Portable third-generation sequencers such as MinION Oxford Nanopore enable genetic identification of nematodes from complex natural environments, including faecal samples [85], and represent a promising alternative for epidemiological studies of Strongyloides spp. The main limitations of such metagenomic approaches are the (un)availability of equipment and reagents in many endemic countries, necessity of thorough optimization of the protocols because the current protocol for the three loci is not perfect (63%, 80% and 68% of sequencing success rate for cox1, HVR-I and HVR-IV, respectively) and an incomplete reference library, as well as the required expertise for raw data processing.

6. Strongyloides distribution based on the literature and sequencing data

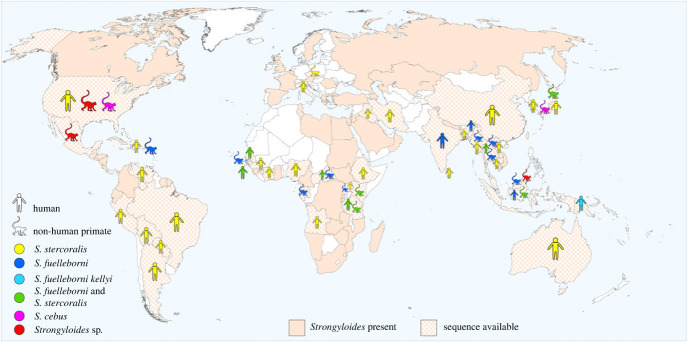

Initial estimates in 1989 indicated 100 million people to be infected with Strongyloides nematodes [86]; this increased to 370 million in 2013 [87] and was most recently (in 2020) estimated at 600 million people infected worldwide, focussed largely in tropical and subtropical regions [88] but with an ever more global distribution, excluding only the far north and south [89] (figure 2). This continuous increase in cases is more likely due to improvements in diagnostic methods than actual increases in infected persons [88]. Nevertheless, the number of people infected with Strongyloides tends to be underestimated due to the sustained use of inadequate methods with low detection rates. In the case of NHP, the global estimates of prevalence are lacking; available prevalence data range from <1% to 100% [91], being probably highly influenced by the methods used.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of Strongyloides spp. in primates, including humans. Chequered filling marks the countries from which any DNA sequences are available in GenBank, together with the host's (human/non-human primate) and the parasite's identity. The overall distribution (presence of Strongyloides in a particular country) is based on several publications in humans [88–90], supplemented with data on the distribution of Strongyloides spp. in non-human primates.

We searched all papers (search of the databases Web of Science and Scopus) dealing with NHP and parasites (keywords included parasites, Strongyloides, strongyloidiasis, primates and apes). Therefore, we not only entered the keyword Strongyloides, but also manually checked all papers on primate parasites, since many papers do not contain Strongyloides as a keyword and would be overlooked. All parasitological articles on NHP were manually checked and those reporting the presence of Strongyloides were included, so we finally selected and analysed 147 reports (electronic supplementary material, table A1). The majority of the studies present the overall parasite spectrum in investigated NHP and only a few publications addressed Strongyloides directly [20,44]. Most of the studies (73%) employed microscopy methods and Strongyloides was therefore classified as Strongyloides sp./spp. or to the assumed species based on presence of eggs or larvae. In Asia, mainly molecular-based identification data are available as all articles are recent, published in the past 15 years. Still, the number of publications is low in comparison with data from Africa, limiting information on the actual diversity and distribution of parasites in NHP, including Strongyloides, from this continent. In general, when Strongyloides is classified to the species level, S. fuelleborni is the most commonly cited species in African and Asian NHP (electronic supplementary material, table S1) [91], but it apparently occurs also in NHP introduced in the Americas [46]. In South America, data are primarily available from New World NHP from Brazil, Mexico and Peru. Coproscopic methods also dominate in these studies and therefore the Strongyloides species cannot be specified. Most of the data from African great apes, but also from other NHP, come from well-established research sites. A majority of the data are retrieved from the limited number of NHP populations that are habituated to frequent contact with humans. By contrast, a very limited amount of data is available from non-habituated animals.

The rise of molecular-based methods for Strongyloides detection is evident in both humans and NHP and their use has grown exponentially in the past few years [91]. This prompted us to investigate the Strongyloides spp. sequences obtained from humans and NHP that are available in the GenBank database (figure 2). Genomic DNA sequences labelled as S. stercoralis, S. fuelleborni, S. cebus and Strongyloides sp. and having a primate indicated as the host were downloaded from GenBank; commonly used markers such as 18S rDNA, ITS-1, 5.8S, ITS-2, 28S rDNA, cox1, 16S rDNA and complete mitochondrial genomes were included in the analysis (n = 2347). Sequences were imported to Geneious Prime 2023.1.2 (www.geneious.com) and sorted based on the marker, host species and country as provided in GenBank. In cases where the metadata were not provided, the publication linked to the sequences was searched for the relevant information.

The analysed Strongyloides sequences originated from 45 countries across Africa, Europe, Asia, the Americas and Australia (figure 2). The vast majority of sequences were labelled as S. stercoralis (n = 1966), mainly from humans (n = 1662) from 37 countries, with mostly cox1 (n = 1022) sequences followed by 28S rDNA (n = 696) and 18S rDNA HVR-I (n = 120). The other hosts and markers were significantly less represented. Similarly, most of the S. fuelleborni (n = 295) sequences were cox1 (n = 203). Almost all sequences were obtained from African and Asian NHP (n = 272), but S. fuelleborni was also detected in a colony of African vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) living on the Caribbean Island of St. Kitts [46]. As the Caribbean haplotypes clustered closely with the African isolates, it is likely that the parasites arrived with the animals originally brought to the island from Africa by Europeans in the seventeenth century [46]. The number of unidentified Strongyloides spp. sequences from NHP was significantly lower (n = 325) than from humans, but all three Strongyloides spp. known from NHP were represented in GenBank, with an additional three undetermined Strongyloides spp. from Bornean slow loris, spider monkeys and baboons. Twenty-three sequences of S. fuelleborni are available from humans from eight countries. Notably, only a single 18S rDNA HVR-I sequence is available for S. kellyi. There were also 46 sequences of S. stercoralis for which it was not possible to confirm the host species and/or locality.

Strongyloides sequences from Africa, but also from Europe, are clearly underrepresented in available datasets. Although the data from Asia and South America seem comparably more represented, they are mainly from a single study, a single sampling, or from multiple studies but focused on the same area (electronic supplementary material, table A2). Very little data are available from sites where humans and NHP share the same habitat. 18S rDNA and cox1 regions are preferably targeted markers, however, the methods used were not uniform, making the phylogeny impossible or difficult to evaluate as different genetic markers are available for different species in GenBank (electronic supplementary material, table A2). Unfortunately, some studies have identified Strongyloides species/haplotypes using molecular methods, but have not entered sequences into databases [58], leaving them unavailable for further analyses.

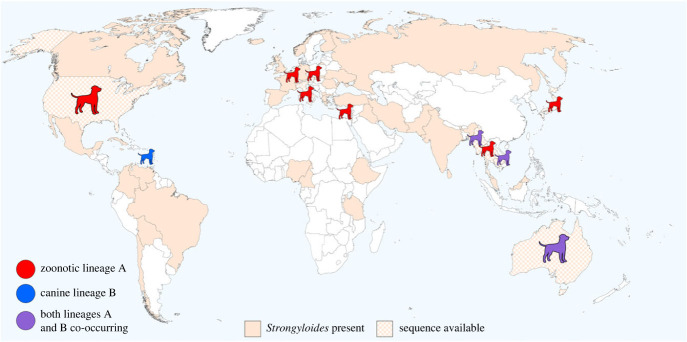

Finally, considering that dogs could play a role in the dissemination of Strongyloides, we also investigated Strongyloides sequencing data available in GenBank from domestic dogs (figure 3) and their possible overlap with those from humans and NHP. Dogs frequently come into contact with NHP either as free-roaming intruders into natural habitats [94] or in villages and similar rural locations visited by NHP. Strongyloides cox1 lineage A could likely be shared between dogs and humans [95] and therefore possibly also NHP. Analysing Strongyloides circulation among humans, dogs, and NHP is a critical gap in epidemiology, however, data enabling such analyses are not available. Notably, there are only seven countries (USA, Japan, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Japan, Australia and Italy) where sequences from dogs and humans (and also from NHP in the first four countries) are deposited in the GenBank, despite the fact that Strongyloides occurrence in canines and primates including humans, mostly overlaps (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 3.

Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs. For chequered-filled countries, DNA sequences are available in GenBank. Lineages A and B are based on cox1 and 18S rDNA HVR-IV as defined in Jaleta et al. [17]. The range of occurrence is based on several publications in dogs [91,92], supplemented with information from other studies about Strongyloides in dogs. There is an ongoing debate about whether the Strongyloides lineage B should be separated as a different species [68], considering S. canis, which was already proposed by Brumpt [93].

7. Message for Strongyloides control projects

Considering zoonotic features of strongyloidiasis, management of infection in the human population is a challenge and a research opportunity at the same time, deserving a One Health perspective. Our review has highlighted persisting knowledge gaps related to the diversity and global distribution of Strongyloides spp. in humans and NHP. To move forward in Strongyloides research, traditional microscopy-based techniques applied both in captive and free-ranging NHP should not be abandoned, but complemented with unified DNA-based tools shared among researchers on a global scale. The NGS metabarcoding (cox1 and HVR-IV of 18S rDNA) appears as the pre-eminent scientific approach; however, there are significant obstacles to overcome such as success rate, demanding equipment and subsequent processing of the obtained data (see above). Elucidating the diversity of Strongyloides is critical for determining species and lineages that infect humans and for uncovering animal reservoirs, transmission pathways and impact on human health in areas of higher incidence of Strongyloides infections. Accurate diagnostics requires novel diagnostic assays (e.g. multiplex qPCR-based), that would allow the easy distinguishing S. stercoralis, S. fuelleborni and possibly S. cebus and S. kelleyi in the diagnostic routine. To date, we know little about the pathology of S. fuelleborni both in humans and NPH, or of S. kelleyi in humans. Considering that these ‘non-stercoralis' taxa might dominate in some areas, such information is necessary for decision-making related to control of these infections.

In higher-incidence areas, active surveillance that involves not only samples from humans, but also from domestic dogs, sympatric NHP and eDNA is necessary to uncover sources of environmental contamination and to understand the role of animal reservoirs of human strongyloidiasis. Active penetration of Strongyloides larvae through the host's skin increases the transmission risk in shared environments. This applies not only for captive settings such as zoos, but also generally for a plethora of situations at the human–wildlife–domestic animals interface. Although experimental data confirming the transmission of Strongyloides between humans and NHP are very limited, the occurrence of identical haplotypes in humans and NHP indicates that the parasite can be shared among multiple hosts under natural conditions [20,37]. NHP frequently visit villages and feed on crops and could directly contaminate food or water sources. NHP are also traded and consumed as bushmeat or are kept as pets in villages and often played with by children. Importantly, terrestrial NHP were more likely positive for Strongyloides than the arboreal ones [96,97]; baboons as typically terrestrial primates are the most frequent visitors to human settlements in Africa [98]. In Asia, NHP play an important cultural role and are revered as deities, allowed to roam freely in villages and towns, visiting fields, parks, gardens and temples. Even people complying with hygiene standards and treated with anthelmintics can be infected/re-infected by Strongyloides shed by NHP in a shared environment. Preventing the NHP from entering the villages and human proximity is hardly achievable, but an effort should be made towards public awareness to minimize crop raiding, access of NHP to garbage and other food resources and intentional feeding of NHP by the public.

Possibility of repeated transmission from NHP and domestic dogs should be taken into account in all initiatives dealing with Strongyloides control in human populations. Regular dehelminthization is an advisable approach to control helminths in domestic dog populations [99]; however, there are no anthelmintic products formally licensed for treatment and prophylaxis of canine Strongyloides infections [100]. In the case of wildlife, such as NHP, administration of any anthelmintics has ethical constraints, including potential adverse impacts on the animals as well as on the environment [101], and the decision to medicate should not be made on the basis of individuals' own will or initiatives. Although human strongyloidiasis has recently been added to the list of neglected tropical diseases requiring control measures in endemic areas [102], effective treatment strategies are far from being optimized. Elimination of infection from an infected individual is difficult to achieve both in animals and humans; classical dosing of anthelmintics (e.g. ivermectin, albendazole and triabendazole) [103] is commonly not sufficient in the case of Strongyloides. In dogs, macrocyclic lactone-based anthelmintics show the desired effect [104] and the efficacy of ivermectin for the treatment of S. fuelleborni [105] and S. cebus [40] has also been demonstrated in NHP. Conversely, other data from captive NHP showed that treatment with anthelmintics does not effectively eliminate Strongyloides larvae shed in faeces [106]. The dosage and treatment regimen of ivermectin—the most appropriate drug to treat Strongyloides—need to be defined for both humans [103] and captive NHP [107], while the suitability of other macrocyclic lactones should be studied [108].

To conclude, we are still facing significant knowledge gaps concerning the diversity and distribution of Strongyloides spp., as well as its epidemiology and health consequences of resulting infections. We advocate for the adoption of a comprehensive and unified approach employing advanced molecular tools in the research and management of Strongyloides infection at the One Health platform, always considering zoonotic potential and possible animal reservoirs in the local contexts.

Data accessibility

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [109].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors' contributions

E.N.: data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; K.M.S.: data curation, validation, writing—review and editing; K.J.P.: data curation, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing; B.Č.: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing; D.M.: investigation, supervision, writing—review and editing; B.P.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Czech Science Foundation grant no. 22-16475S, Morris Animal Foundation, grant no. D21ZO-042, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—Great Ape Conservation Fund, grant no. F22AP02231-00 and by institutional support from the Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic (RVO:68081766) and Masaryk University (MUNI/A/1422/2022).

REFERENCES

- 1.Perelman P, et al. 2011. A molecular phylogeny of living primates. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001342. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001342) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunay E, Apakupakul K, Leard S, Palmer JL, Deem SL. 2018. Pathogen transmission from humans to great apes is a growing threat to primate conservation. Ecohealth 15, 148-142. ( 10.1007/s10393-017-1306-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. 2001. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 356, 983-989. ( 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe ND, Dunavan CP, Diamond J. 2007. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 447, 279-283. ( 10.1038/nature05775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharp PM, Hahn BH. 2010. The evolution of HIV-1 and the origin of AIDS. Phil. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B 365, 2487-2494. ( 10.1098/rstb.2010.0031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paraskevis D, Magiorkinis G, Magiorkinis E, Ho SY, Belshaw R, Allain JP, Hatzakis A. 2013. Dating the origin and dispersal of hepatitis B virus infection in humans and primates. Hepatology 57, 908-916. ( 10.1002/hep.26079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wachtman L, Mansfield K. 2012. Viral diseases of nonhuman primates. Nonhum. Primates Biomed. Res. 2012, 1-104. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-381366-4.00001-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips MA, Burrows JN, Manyando C, van Huijsduijnen RH, Van Voorhis WC, Wells TNC. 2017. Malaria. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 17050. ( 10.1038/nrdp.2017.50) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu W, et al. 2010. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature 467, 420-425. ( 10.1038/nature09442) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negrey JD, et al. 2019. Simultaneous outbreaks of respiratory disease in wild chimpanzees caused by distinct viruses of human origin. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 8, 139-149. ( 10.1080/22221751.2018.1563456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montali RJ, Mikota SK, Cheng LI. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in zoo and wildlife species. Rev. Sci. Tech. 20, 291-303. ( 10.20506/rst.20.1.1268) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogadov DI, Kyuregyan KK, Goncharenko AM, Mikhailov MI. 2023. Measles in non-human primates. J. Med. Primatol. 52, 135-143. ( 10.1111/jmp.12630) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narat V, Alcayna-Stevens L, Rupp S, Giles-Vernick T. 2017. Rethinking human–nonhuman primate contact and pathogenic disease spillover. Ecohealth 14, 840-850. ( 10.1007/s10393-017-1283-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bloomfield LSP. 2020. Global mapping of landscape fragmentation, human–animal interactions, and livelihood behaviors to prevent the next pandemic. Agric Hum. Values 37, 603-604. ( 10.1007/s10460-020-10104-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devaux CA, Mediannikov O, Medkour H, Raoult D. 2019. Infectious disease risk across the growing human–non human primate interface: a review of the evidence. Front. Public Health 7, 305. ( 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00305) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pampiglione S, Nájera E, Ricciardi ML, Junginger L. 1979. Parasitological survey on Pygmies in Central Africa. III. Bambuti group (Zaire). Rivista Di Parassitol. 40, 187-234. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaleta TG, Zhou S, Bemm FM, Schär F, Khieu V, Muth S, Odermatt P, Lok JB, Streit A. 2017. Different but overlapping populations of Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs and humans—dogs as a possible source for zoonotic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005752. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thamsborg SM, Ketzis J, Horii Y, Matthews JB. 2017. Strongyloides spp. infections of veterinary importance. Parasitology 144, 274-284. ( 10.1017/S0031182016001116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sirima C, et al. 2021. Soil-transmitted helminth infections in free-ranging non-human primates from Cameroon and Gabon. Parasit Vectors 14, 354. ( 10.1186/s13071-021-04855-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa H, Kalousova B, Mclennan MR, Modry D, Profousova-Psenkova I, Shutt-Phillips KA, Todd A, Huffman MA, Petrzelkova KJ. 2016. Strongyloides infections of humans and great apes in Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas, Central African Republic and in degraded forest fragments in Bulindi, Uganda. Parasitol. Int. 65, 367-370. ( 10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradbury RS, Pafčo B, Nosková E, Hasegawa H. 2021. Strongyloides genotyping: a review of methods and application in public health and population genetics. Int. J. Parasitol. 51, 1153-1166. ( 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.10.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagayasu E, et al. 2017. A possible origin population of pathogenic intestinal nematodes, Strongyloides stercoralis, unveiled by molecular phylogeny. Sci. Rep. 7, 4844. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-05049-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashford RW, Barnish G, Viney ME. 1992. Strongyloides fuelleborni kellyi: Infection and disease in Papua New Guinea. Parasitol Today 8, 314-318. ( 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90106-c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradbury RS. 2021. Strongyloides fuelleborni kellyi in New Guinea: neglected, ignored and unexplored. Microbiol. Aust. 42, 169-172. ( 10.1071/MA21048) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller R, Lillywhite J, Bending JJ, Catford JC. 1987. Human cysticercosis and intestinal parasitism amongst the Ekari people of Irian Jaya. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90, 291-296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viney ME, Ashford RW, Barnish G. 1991. A taxonomic study of Strongyloides Grassi, 1879 (Nematoda) with special reference to Strongyloides fuelleborni von linstow, 1905 in man in Papua New Guinea and the description of a new subspecies. Syst. Parasitol. 18, 95-109. ( 10.1007/BF00017661) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorris M, Viney ME, Blaxter ML. 2002. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the genus Strongyloides and related nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 1507-1517. ( 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00156-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Linstow. 1905. ‘Strongyloides fülleborni n.sp’ Centralbl. f.Bakt. 1 Abt. Originale. Bd. 38 Heft, 5: 532–4.

- 29.Hung SL, Höppli R. 1923. Morphologische und histologische beiträge zur Strongyloides-infection der tiere. Arch. f. Schiffs-u. Tropen-Hyg. 27, 118-129. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandground JH. 1925. Speciation and specificity in the nematode genus Strongyloides. J. Parasitol. 12, 59-80. ( 10.2307/3270768) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodey T. 1926. Observations on Strongyloides Fülleborni von Linstow, 1905, with some remarks on the genus Strongyloides. J. Helminthol. 4, 75-86. ( 10.1017/S0022149X00029576) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Premvati G. 1959. Studies on Strongyloides of primates: V. Synonymy of the species in monkeys and apes. Can. J. Zool. 37, 75-81. ( 10.1139/z59-009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little MD. 1966. Comparative morphology of six species of Strongyloides (Nematoda) and redefinition of the genus. J. Parasitol. 52, 69-84. ( 10.2307/3276396) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barratt JLN, Sapp SGH. 2020. Machine learning-based analyses support the existence of species complexes for Strongyloides fuelleborni and Strongyloides stercoralis. Parasitology 147, 1184-1195. ( 10.1017/S0031182020000979) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasegawa H, et al. 2010. Molecular identification of the causative agent of human strongyloidiasis acquired in Tanzania: dispersal and diversity of Strongyloides spp. and their hosts. Parasitol. Int. 59, 407-413. ( 10.1016/j.parint.2010.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thanchomnang T, et al. 2017. First molecular identification and genetic diversity of Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni in human communities having contact with long-tailed macaques in Thailand. Parasitol. Res. 116, 1917-1923. ( 10.1007/s00436-017-5469-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janwan P, Rodpai R, Intapan PM, Sanpool O, Tourtip S, Maleewong W, Thanchomnang T. 2020. Possible transmission of Strongyloides fuelleborni between working Southern pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) and their owners in Southern Thailand: molecular identification and diversity. Infect. Genet. Evol. 85, 104516. ( 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104516) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frias L, Stark DJ, Lynn MS, Nathan SK, Goossens B, Okamoto M, MacIntosh AJJ. 2018. Lurking in the dark: cryptic Strongyloides in a Bornean slow loris. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 7, 141-146. ( 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.03.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Augustine DL. 1940. Experimental studies on the validity of species in the genus Strongyloides. Am. J. Hyg. 32, 24-32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mati VL, Ferreira Junior FC, Pinto HA, de Melo AL. 2013. Strongyloides cebus (Nematoda: Strongyloididae) in Lagothrix cana (Primates: Atelidae) from the Brazilian Amazon: aspects of clinical presentation, anatomopathology, treatment, and parasitic biology. J. Parasitol. 99, 1009-1018. ( 10.1645/13-288.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darling ST. 1911. Strongyloides infections in man and animals in the Isthmian Canal Zone. J. Exp. Med. 14, 1-24. ( 10.1084/jem.14.1.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helenbrook WD, Wade SE, Shields WM, Stehman SV, Whipps CM. 2015. Gastrointestinal parasites of Ecuadorian mantled howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata aequatorialis) based on fecal analysis. J. Parasitol. 101, 341-350. ( 10.1645/13-356.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Solano S, Carrillo-Bilbao GA, Ramirez W, Celi-Erazo M, Huynen MC, Levecke B, Benitez-Ortiz W, Losson B. 2017. Gastrointestinal parasites in captive and free-ranging Cebus albifrons in the Western Amazon, Ecuador. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 6, 209-218. ( 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.06.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko PP, et al. 2023. Population genetics study of Strongyloides fuelleborni and phylogenetic considerations on primate-infecting species of Strongyloides based on their mitochondrial genome sequences. Parasitol. Int. 92, 102663. ( 10.1016/j.parint.2022.102663) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hiebert K, Gardhouse S, Sarvi J, Herrin B, Miller K, Chelladurai JJ. 2023. Identification and treatment of Strongyloides cebus in captive ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) in the midwestern United States. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 39, 100839. ( 10.1016/j.vprsr.2023.100839) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richins T, Sapp SGH, Ketzis JK, Willingham AL, Mukaratirwa S, Qvarnstrom Y, Barratt JLN. 2023. Genetic characterization of Strongyloides fuelleborni infecting free-roaming African vervets (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 20, 153-161. ( 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2023.02.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pourrut X, Diffo JL, Somo RM, Bilong Bilong CF, Delaporte E, LeBreton M, Gonzalez JP. 2011. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in primate bushmeat and pets in Cameroon. Vet. Parasitol. 175, 187-191. ( 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.09.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beach TD. 1936. Experimental studies on human and primate species of Strongyloides. V. The free-living phase of the life cycle . Am. J. Hyg. 23, 243-277. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Labes EM, Nurcahyo W, Deplazes P, Mathis A. 2011. Genetic characterization of Strongyloides spp. from captive, semi-captive and wild Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in Central and East Kalimantan, Borneo, Indonesia. Parasitology 138, 1417-1422. ( 10.1017/S0031182011001284) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nosková E, et al. 2023. Identification of potentially zoonotic parasites in captive orangutans and semi-captive mandrills: phylogeny and morphological comparison. Am. J. Primatol. 85, e23475. ( 10.1002/ajp.23475) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solórzano-García B, Pérez-Ponce de León G. 2017. Helminth parasites of howler and spider monkeys in Mexico: Insights into molecular diagnostic methods and their importance for zoonotic diseases and host conservation. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 6, 76-84. ( 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.04.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson J, Upadhayay R, Sudimack D, Nair S, Leland M, Williams JT, Anderson TJ. 2012. Trichuris sp. and Strongyloides sp. infections in a free-ranging baboon colony. J. Parasitol. 98, 205-208. ( 10.1645/GE-2493.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ko PP, et al. 2020. Phylogenetic relationships of Strongyloides species in carnivore hosts. Parasitol. Int. 78, 102151. ( 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takaki Y, Kadekaru S, Takami Y, Yoshida A, Maruyama H, Une Y, Nagayasu E. 2021. First demonstration of Strongyloides parasite from an imported pet meerkat – Possibly a novel species in the stercoralis/procyonis group. Parasitol. Int. 84, 102399. ( 10.1016/j.parint.2021.102399) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pampiglione S, Ricciardi ML. 1971. The presence of Strongyloides fülleborni von Linstow, 1905, in man in Central and East Africa. Parassitologia 13, 257-269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pampiglione S, Ricciardi M. 1974. Parasitological survey on Pygmies in Central Africa. I. Babinga group (Central African Republic). Rivista Di Parassitol. 35, 161-188. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pafčo B, et al. 2017. Do habituation, host traits and seasonality have an impact on protist and helminth infections of wild western lowland gorillas? Parasitol. Res. 116, 3401-3410. ( 10.1007/s00436-017-5667-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Potters I, Micalessi I, Esbroeck MV, Gils S, Theunissen C. 2020. A rare case of imported Strongyloides fuelleborni infection in a Belgian student. CLIP 7–8, 100031. ( 10.1016/j.clinpr.2020.100031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Narat V, Guillot J, Pennec F, Lafosse S, Grüner AC, Simmen B, Bokika Ngawolo JC, Krief S. 2015. Intestinal helminths of wild bonobos in forest-savanna mosaic: risk assessment of cross-species transmission with local people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ecohealth 12, 621-633. ( 10.1007/s10393-015-1058-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thanchomnang T, et al. 2019. First molecular identification of Strongyloides fuelleborni in long-tailed macaques in Thailand and Lao People's Democratic Republic reveals considerable genetic diversity. J. Helminthol. 93, 608-615. ( 10.1017/S0022149X18000512) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medkour H, et al. 2020. Parasitic infections in African humans and non-human primates. Pathogens 9, 561. ( 10.3390/pathogens9070561) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blackie WK. 1932. A helminthological survey of southern Rhodesia. London, UK: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomita S. 1940. Experiment on susceptibility of humans to infection by Strongyloides fülleborni and with S. papillosus. J. Med. Ass. Formosa 39, 1885. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desportes C. 1945. Sur Strongyloides stercoralis (Bavay 1876) et sur les Strongyloides de primates. Ann. Parasite Hum. Comp. 20, 160-190. (https://www.parasite-journal.org/articles/parasite/abs/1944/03/parasite1944-1945203p160/parasite1944-1945203p160.html) [Google Scholar]

- 65.Penner LR. 1981. Concerning threadworm (Strongyloides stercoralis) in great apes: Lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Zool. Anim. Med. 12, 128-131. ( 10.2307/20094543) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harper JS, Rice JM, London WT, Sly DL, Middleton C. 1982. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in Erythrocebus patas. Am. J. Primatol. 3, 89-88. ( 10.1002/ajp.1350030108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toft JD. 1982. The pathoparasitology of the alimentary tract and pancreas of nonhuman primates: a review. Vet. Pathol. Suppl. 7, 44-92. ( 10.1177/030098588201907s06) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Streit A. 2021. Strongyloidiasis: really a zoonosis? In Dog parasites endangering human health (eds Strube C, Mehlhorn H), pp. 195-226. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hagelskjaer LH. 1994. A fatal case of systemic strongyloidiasis and review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13, 1069-1074. ( 10.1007/BF02111831) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harper JS 3rd, Genta RM, Gam A, London WT, Neva FA. 1984. Experimental disseminated strongyloidiasis in Erythrocebus patas. I. Pathology. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33, 431-443. ( 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.431) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kleinschmidt LM, Kinney ME, Hanley CS. 2018. Treatment of disseminated Strongyloides spp. infection in an infant Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii). J. Med. Primatol. 47, 201-204. ( 10.1111/jmp.12338) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mati VL, Raso P, de Melo AL. 2014. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in marmosets: replication of complicated and uncomplicated human disease and parasite biology. Parasit Vectors 7, 579. ( 10.1186/s13071-014-0579-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freedman DO. 1991. Experimental infection of human subject with Strongyloides species. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13, 1221-1226. ( 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1221) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jirků-Pomajbíková K, Hůzová Z. 2018. Coproscopic examination techniques. In Parasites of apes. An atlas of coproscopic diagnostics (eds Modrý D, Pafčo B, Petrželková KJ, Haegawa H), pp. 22-28. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Chimaira. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watts M, Robertson G, Bradbury R. 2016. The laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis. Microbiol. Aust. 37, 4-9. ( 10.1071/MA16003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kristanti H, Meyanti F, Wijayanti MA, Mahendradhata Y, Polman K, Chappuis F, Utzinger J, Becker SL, Murhandarwati EEH. 2018. Diagnostic comparison of Baermann funnel, Koga agar plate culture and polymerase chain reaction for detection of human Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Maluku, Indonesia. Parasitol. Res. 117, 3229-3235. ( 10.1007/s00436-018-6021-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou S, Harbecke D, Streit A. 2019. From the feces to the genome: a guideline for the isolation and preservation of Strongyloides stercoralis in the field for genetic and genomic analysis of individual worms. Parasit Vectors 12, 496. ( 10.1186/s13071-019-3748-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bisoffi Z, et al. 2014. Diagnostic accuracy of five serologic tests for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2640. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002640) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buonfrate D, et al. 2015. Accuracy of five serologic tests for the follow up of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003491. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003491) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, Ziem J, Brienen EA, Polderman AM, van Lieshout L. 2009. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103, 342-346. ( 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watts MR, et al. 2014. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for Strongyloides stercoralis in stool that uses a visual detection method with SYTO-82 fluorescent dye. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90, 306-311. ( 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0583) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barratt JLN, et al. 2019. A global genotyping survey of Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni using deep amplicon sequencing. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007609. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007609) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beknazarova M, Barratt JLN, Bradbury RS, Lane M, Whiley H, Ross K. 2019. Detection of classic and cryptic Strongyloides genotypes by deep amplicon sequencing: a preliminary survey of dog and human specimens collected from remote Australian communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 13, e0007241. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007241) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aupalee K, Wijit A, Singphai K, Rödelsperger C, Zhou S, Saeung A, Streit A. 2020. Genomic studies on Strongyloides stercoralis in northern and western Thailand. Parasit Vectors 13, 250. ( 10.1186/s13071-020-04115-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Knot I, Zouganelis G, Weedall G, Wich S, Rae R. 2020. DNA barcoding of nematodes using the MinION. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8, 100. ( 10.3389/fevo.2020.00100) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Genta RM. 1989. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev. Infect Dis. 11, 755-767. ( 10.1093/clinids/11.5.755) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bisoffi Z, et al. 2013. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 7, e2214. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Buonfrate D, et al. 2020. The global prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Pathogens 9, 468. ( 10.3390/pathogens9060468) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Marti H, Vounatsou P, Odermatt P. 2013. Strongyloides stercoralis: global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2288. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Puthiyakunnon S, Boddu S, Li Y, Zhou X, Wang C, Li J, Chen X. 2014. Strongyloidiasis—an insight into its global prevalence and management. PLoS Negl Trop. Dis. 88, e3018. ( 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.White MAF, Whiley HE, Ross K. 2019. A review of Strongyloides spp. environmental sources worldwide. Pathogens 8, 91. ( 10.3390/pathogens8030091) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eslahi AV, Hashemipour S, Olfatifar M, Houshmand E, Hajialilo E, Mahmoudi R, Badri M, Ketzis JK. 2022. Global prevalence and epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors 15, 21. ( 10.1186/s13071-021-05135-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brumpt E. 1922. Strongyloides stercoralis (Bavay, 1877) [in French]. In Précis de parasitologie. 3ème edition ed (ed. Brumpt E), pp. 691-697. Paris, France: Mason et Cie. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Parsons MB, Gillespie TR, Lonsdorf EV, Travis D, Lipende I, Gilagiza B, Kamenya S, Pintea L, Vazquez-Prokopec GM. 2014. Global positioning system data-loggers: a tool to quantify fine-scale movement of domestic animals to evaluate potential for zoonotic transmission to an endangered wildlife population. PLoS ONE 9, e110984. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0110984) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanpool O, Intapan PM, Rodpai R, Laoraksawong P, Sadaow L, Tourtip S, Piratae S, Maleewong W, Thanchomnang T. 2019. Dogs are reservoir hosts for possible transmission of human strongyloidiasis in Thailand: molecular identification and genetic diversity of causative parasite species. J. Helminthol. 94, e110. ( 10.1017/S0022149X1900107X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Karere GM, Munene E. 2002. Some gastro-intestinal tract parasites in wild De Brazza's monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus) in Kenya. Vet. Parasitol. 110, 153-157. ( 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00348-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bezjian M, Gillespie TR, Chapman CA, Greiner EC. 2008. Coprologic evidence of gastrointestinal helminths of forest baboons, Papio anubis, in Kibale National Park, Uganda. J. Wildl Dis. 44, 878-887. ( 10.7589/0090-3558-44.4.878) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hill CM. 2000. Conflict of interest between people and baboons: crop raiding in Uganda. Int. J. Primatol. 21, 299-315. ( 10.1023/A:1005481605637) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Mihalca AD, Traub RJ, Lappin M, Baneth G. 2017. Zoonotic parasites of sheltered and stray dogs in the era of the global economic and political crisis. Trends Parasitol. 33, 813-825. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2017.05.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Paradies P, Iarussi F, Sasanelli M, Capogna A, Lia RP, Zucca D, Greco B, Cantacessi C, Otranto D. 2017. Occurrence of strongyloidiasis in privately owned and sheltered dogs: clinical presentation and treatment outcome. Parasit Vectors 10, 345. ( 10.1186/s13071-017-2275-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.de Souza RB, Guimarães JR. 2022. Effects of avermectins on the environment based on its toxicity to plants and soil invertebrates—a review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 233, 259. ( 10.1007/s11270-022-05744-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.World Health Organization. 2017. Guideline: Preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buonfrate D, Rodari P, Barda B, Page W, Einsiedel L, Watts MR. 2022. Current pharmacotherapeutic strategies for Strongyloidiasis and the complications in its treatment. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 23, 1617-1628. ( 10.1080/14656566.2022.2114829) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paradies P, et al. 2019. Efficacy of ivermectin to control Strongyloides stercoralis infection in sheltered dogs. Acta Trop. 90, 204-209. ( 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.11.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dufour JP, Cogswell FB, Phillippi-Falkenstein KM, Bohm RP. 2006. Comparison of efficacy of moxidectin and ivermectin in the treatment of Strongyloides fulleborni infection in rhesus macaques. J. Med. Primatol. 35, 172-176. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2006.00154.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gomez MS, Gracenea M, Gosalbez P, Montolium I, Feliu C, Eensenat C. 1992. Intestinal protozoa in the great apes of the Barcelona Zoo. Post-treatment control. VIth EMOP 7-1, The Hague. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Reichard MV, Thomas JE, Chavez-Suarez M, Cullin CO, White GL, Wydysh EC, Wolf RF. 2017. Pilot study to assess the efficacy of ivermectin and fenbendazole for treating captive-born Olive baboons (Papio anubis) coinfected with Strongyloides fülleborni and Trichuris trichiura. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 56, 52-56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hofmann D, Smit C, Sayasone S, Pfister M, Keiser J. 2022. Optimizing moxidectin dosing for Strongyloides stercoralis infections: Insights from pharmacometric modeling. Clin. Transl Sci. 15, 700-708. ( 10.1111/cts.13189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nosková E, Sambucci KM, Petrželková KJ, Červená B, Modrý D, Pafčo B. 2023. Strongyloides in non-human primates: significance for public health control. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6890521) [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [109].