Abstract

We characterized the regulated activity of the lactococcal nisA promoter in strains of the gram-positive species Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, and Bacillus subtilis. nisA promoter activity was dependent on the proteins NisR and NisK, which constitute a two-component signal transduction system that responds to the extracellular inducer nisin. The nisin sensitivity and inducer concentration required for maximal induction varied among the strains. Significant induction of the nisA promoter (10- to 60-fold induction) was obtained in all of the species studied at a nisin concentration just below the concentration at which growth is inhibited. The efficiency of the nisA promoter was compared to the efficiencies of the Spac, xylA, and lacA promoters in B. subtilis and in S. pyogenes. Because nisA promoter-driven expression is regulated in many gram-positive bacteria, we expect it to be useful for genetic studies, especially studies with pathogenic streptococci in which no other regulated promoters have been described.

Many gram-positive cocci, such as Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus), Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and some strains of Enterococcus faecalis (previously classified as group D streptococcus), are important pathogens that are major causes of a variety of infectious diseases in humans. The illnesses caused by these pathogenic streptococci range from local infections of moderate severity, such as impetigo, pharyngitis, sinusitis, and otitis media, to life-threatening invasive diseases, such as pneumonia, meningitis, endocarditis, bacteremia, myositis, necrotizing fasciitis, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. In addition, some types of streptococcal infections can result in severe complications, such as arthritis, rheumatic fever, and acute glomerulonephritis (2). Major progress has been made in the last decade in the genetic study of pathogenic streptococci due to the development of molecular tools such as vectors, reporter genes, transducing phages, and transposons that are functional in these bacteria (6, 13). However, the absence of other important tools, such as controlled gene expression systems, significantly limits the study of these gram-positive pathogens.

Bacterial pathogens often regulate the expression of virulence genes in a coordinated manner in response to changes in the environment. The ability to manipulate the expression of different genes is an important tool for understanding the regulatory cascade mechanisms and the importance of gene regulation in pathogenesis. In addition, to study the importance of the relative quantities of gene products on their interactions, it is essential to be able to control their expression independently. For these purposes, a regulated heterologous promoter system is essential.

In gram-negative bacteria, a variety of promoters (native or chimeric) and vectors (ranging from low to high copy number) have been developed to allow quantitative modulation of gene expression over a range of levels. Unfortunately, many of these systems do not function in gram-positive organisms, probably because the requirements for promoter usage are more stringent in these bacteria than in Escherichia coli (34, 35). Only a few regulated promoters have been described for gram-positive bacteria, and some of these, such as the Bacillus subtilis sporulation promoters, require factors unique to the native species that are not present in heterologous systems, like specific sigma factors and their regulators (19). Some sugar-regulated promoters might not be functional in all hosts because they depend both on sugar entry and on some initial steps to convert the sugar into the inducer that relieves repression of the promoter involved. The appropriate enzymes to carry out these processes might not be present in all hosts. A considerable portion of the available information regarding gene expression in gram-positive bacteria was obtained from the extensively studied species B. subtilis and Lactococcus lactis (10, 11).

One well-characterized lactococcal gene expression system is based on the autoregulatory properties of the L. lactis nisin gene cluster. Two genes in the cluster, nisA and nisF, are induced by nisin via a two-component signal transduction pathway consisting of a histidine protein kinase, NisK, and a response regulator, NisR. Expression of both nisR and nisK is driven from the constitutive promoter of nisR (9, 29). Nisin acts as an inducer on the outside of the cell and is sensed by NisK. Recently, it has been reported that a two-plasmid system in which the nisA promoter and the regulatory genes nisR and nisK are used allows efficient control of gene expression by nisin in a variety of lactic acid bacteria (27, 30).

Another controllable expression system of L. lactis is based on the lactose-inducible transcription of the lac operon. Expression of this operon is repressed during growth on glucose and is regulated at the transcriptional level by the LacR repressor (40). LacR expression is repressed during growth on lactose, which allows expression from the lacA promoter. The lacA promoter and the LacR repressor have been used to express several heterologous genes in a lactose-glucose-dependent manner in L. lactis (40, 42).

In B. subtilis, expression of the xylose utilization operon is inducible via a repressor-mediated mechanism (18). The xylA promoter and the XylR repressor have been used to control expression of heterologous genes in bacillus species. In addition to such native promoters, a chimeric promoter, designated Spac, consisting of the E. coli lac operator fused to the SPO-1 phage promoter was constructed to regulate gene expression in bacillus (45). The promoter and the ribosome-binding site of the penicillinase gene of Bacillus licheniformis were linked to the E. coli lacI repressor gene to allow expression of lacI in bacillus. In this system, transcription from Spac is repressed by the LacI repressor and can be induced by lactose and the gratuitous inducer isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG).

In pathogenic streptococci, no regulated foreign promoters have been identified. Furthermore, there is a paucity of information regarding comparative expression of specific promoters in different pathogenic streptococcal species. We demonstrate here that the L. lactis nisA promoter is active in all of the gram-positive species that we used, including the pathogenic streptococci. Furthermore, expression from the nisA promoter can be efficiently regulated experimentally in all of these organisms. When the same reporter gene was used, the nisA promoter was found to be stronger than the lacA, xylA, or Spac promoter in both B. subtilis and S. pyogenes and to show the greatest degree of induction in S. pyogenes. We expect the nisA promoter to allow manipulation of gene expression in pathogenic streptococci and to bring the level of sophistication of genetic studies of these gram-positive bacteria closer to that of gram-negative pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Experiments were performed with the following gram-positive strains: S. pyogenes JRS4 (group A streptococcus) (15), S. agalactiae COH31 (group B streptococcus) (38), S. pneumoniae 1131 (47), E. faecalis OG1RF (12), and B. subtilis W168 (7). L. lactis FMCB1, derived from MG1363 (5), was used as a host for plasmids pNZ9520 and pNZ9530 (Table 1), and E. coli JM109 (44) and DH5α (20) were used as hosts for all of the other plasmids (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pDG1832 | xylR, xylA promoter, pUC19 replicon | 1 |

| pDH88 | laclq, Spac promoter, Amp | 45 |

| pEU308 | laclq, Spac promoter, pSH71 replicon, Spec | This study |

| pEU327 | xylR, xylA promoter, pSH71 replicon, Spec | This study |

| pEU352 | pEU308 derivative carrying the gusA gene transcriptionally fused to the Spac promoter | This study |

| pEU356 | pEU327 derivative carrying the gusA gene transcriptionally fused to the xylA promoter | This study |

| pLZ12Spec | pSH71, Spec | 23 |

| pMLK99 | gusA gene, Bluescript-SK derivative, Amp | 26 |

| pMLK100a | gusA gene, Bluescript-SK replicon, Amp | 26 |

| pNZ276 | lacR, gusA gene transcriptionally fused to the lacA promoter, pSH71 replicon, Cm | 37 |

| pNZ8008 | Promoterless gusA gene transcriptionally fused to the nisA promoter, pSH71 replicon, Cm | 9 |

| pNZ9520 | nisR and nisK (both expressed from rep promoter), pAMβ1 replicon, Erm | 27 |

| pNZ9530 | nisR and nisK (both expressed from rep promoter), derivative of pAMβ1 replicon with a deletion in repF repressor gene, Erm | 27 |

Plasmid pMLK100 is identical to pMLK99 except that the gusA gene is in the opposite orientation.

Media.

S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, and E. faecalis were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (16). S. pyogenes was also grown on L3 medium (22). S. pneumoniae cells were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract. B. subtilis and E. coli cells were grown in Luria broth (39). L. lactis cells were grown in M17 broth (Becton-Dickinson) supplemented with 0.5% glucose. The following antibiotics were used: for S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, and S. pneumoniae, 0.5 μg of erythromycin per ml and 2 μg of chloramphenicol per ml; for E. faecalis, B. subtilis, and L. lactis, 5 μg of erythromycin per ml and 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml; and for all species, 100 μg of spectinomycin per ml.

Plasmid DNA preparation and transformation.

Plasmid DNA was prepared from L. lactis by using glass beads for cell lysis (17) and from E. coli by the alkaline lysis method (32). Naturally competent S. pneumoniae and B. subtilis cells were transformed with plasmid DNA as previously described (43, 46). Electroporation was used as previously described to transform S. pyogenes (36), S. agalactiae (14), and E. faecalis (33).

Plasmid construction.

The plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Plasmid pEU308 was obtained by ligating the 2.1-kb StyI-EcoRI fragment of plasmid pDH88 (45), containing the Spac promoter and the laclq repressor gene, to a 3.4-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of plasmid pLZ12Spec (23) carrying the pSH71 origin of replication and the spectinomycin resistance gene add9. The protruding ends of StyI and HindIII were filled in by using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I prior to digestion with EcoRI. Plasmid pEU352 was generated by ligating the 1.85-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment of plasmid pMLK99 (26) carrying a promoterless gusA gene to plasmid pEU308 cut with HindIII and BglII, creating a transcriptional fusion of the Spac promoter to the gusA gene.

Plasmid pEU327 was constructed by ligating the 3.4-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of plasmid pLZ12Spec containing the pSH71 origin of replication and the add9 spectinomycin resistance gene to the 1.5-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of plasmid pDG1832 (1) carrying the xylR repressor and the xylA promoter. Plasmid pEU356 was generated by ligating the 1.85-kb NotI-HindIII fragment of plasmid pMLK100 (26) carrying a promoterless gusA gene to plasmid pEU327 cut with HincII and HindIII, creating a transcriptional fusion of the xylA promoter and the gusA gene. The protruding ends of NotI were filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I prior to cutting with HindIII.

β-Glucuronidase activity.

Nisin was obtained from Sigma as a 2.5% nisin solution in sodium chloride containing denatured milk solids. The nisin concentrations referred to below are in micrograms of total solids per milliliter. Stock solutions of nisin were made by suspending 100 mg of nisin per ml in 0.05% acetic acid and then diluting the preparations 10-fold with dimethyl sulfoxide and were stored at −20°C. Further dilutions were made with water and were used immediately.

Expression of the gusA gene was determined by assaying the rate of hydrolysis of the substrate p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide. Bacterial cultures were inoculated at concentrations of approximately 106 CFU/ml into selective media along with various concentrations of nisin. Most cultures were grown overnight at 37°C statically; the only exception was B. subtilis cultures, which were grown with aeration. A 1.0-ml aliquot of each culture was pelleted, resuspended in 0.4 ml of lysis buffer [60 mM K2HPO4, 33 mM KH2PO4, 7.4 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.7 mM sodium citrate; pH 7.0], and lysed with a FastPrep cell disrupter (model FP120; Bio 101, Inc.) in tubes containing a glass bead matrix (Bio 101, Inc.) at a speed of 5 m/s for 30 s. A 0.1-ml aliquot of cell extract was added to 0.9 ml of reaction buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM MgSO4 [pH 7.0], 20 mM dithiothreitol), and 0.2 ml of a 4-mg/ml solution of p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide in lysis buffer was then added. Samples were incubated at 30°C until yellow color development reached an optical density at 420 nm of approximately 0.2 to 0.6. Reactions were stopped by adding 0.5 ml of 1 M Na2CO3. Enzyme activity (units [U]) is given below as 1,000 times the increase in absorbance at 420 nm per minute per unit of optical density at 600 nm of the culture.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nisin gene expression system.

To characterize regulated expression driven from the L. lactis nisA promoter, we used a plasmid-based system with E. coli gusA as a reporter gene. This system consists of a reporter plasmid and a regulatory plasmid, each derived from a broad-host-range replicon. The reporter plasmid, pNZ8008, is a pSH71 derivative that carries a transcriptional fusion of the nisA promoter to gusA (9) (Table 1). The nisA regulatory genes, nisR and nisK, were carried on either of two alternative plasmids, both of which are pAMβ1 replicons. One of the regulatory plasmids, pNZ9530, carries the native pAMβ1 origin of replication, and the other, pNZ9520, is a derivative that has a deletion in the replication repressor gene, repF, which results in increased plasmid copy number in L. lactis (27) (Table 1). Consistent with their copy numbers, plasmids pNZ9530 and pNZ9520 are expected to provide low and high gene dosages, respectively, of the regulatory genes nisR and nisK.

Nisin sensitivity among the species tested.

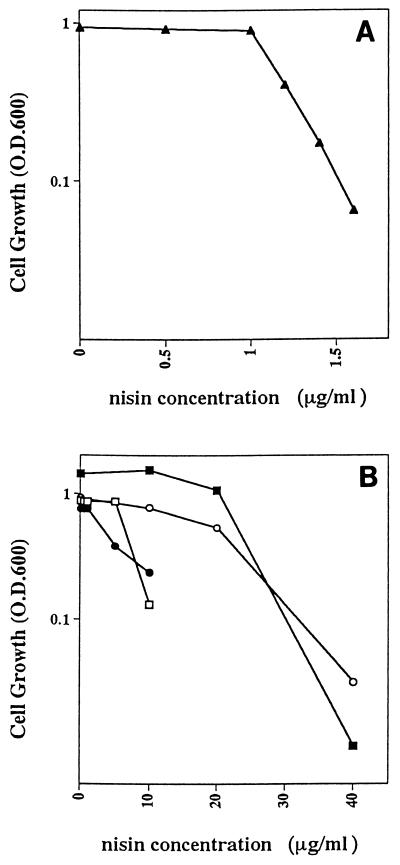

Nisin has bactericidal activity against many gram-positive bacteria, including staphylococci, streptococci, bacilli, clostridia, and mycobacteria (24). However, nisin sensitivity has been reported to vary significantly, even between members of the same species (3, 4, 8). We found that there is considerable variation in nisin sensitivity among S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, B. subtilis, and E. faecalis (Fig. 1), which is consistent with observations made for other gram-positive bacteria (4, 8, 24, 41).

FIG. 1.

Nisin sensitivity. Bacteria harboring both the reporter vector and one of the regulatory plasmids were inoculated into media containing different nisin concentrations. Cell growth is expressed as the culture optical density at 600 nm (O.D.600) following overnight incubation at 37°C. (A) S. pyogenes cells carrying pNZ9520 and pNZ8008. (B) Strains of the following species carrying pNZ8008 and pNZ9530: S. agalactiae (□), S. pneumoniae (•), B. subtilis (■), and E. faecalis (○).

The nisA system is regulated by nisin in all strains tested.

Modulation of the nisA promoter activity by nisin was characterized in S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, B. subtilis, and E. faecalis. Cells harboring both the reporter vector pNZ8008 and one of the regulatory plasmids were incubated in media containing different amounts of nisin. The β-glucuronidase activity (expressed from the nisA promoter-gus transcriptional fusion) was determined following overnight incubation. In all strains tested, cells harboring only the gusA reporter plasmid exhibited very low levels of β-glucuronidase activity. This indicates that nisA promoter function is dependent on its regulatory components, NisR and NisK, even in heterologous hosts. However, the plasmid supplying the regulatory proteins NisR and NisK for optimal induction differed in the different hosts (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Regulated nisA promoter-driven expression

| Organisma | Fold inductionb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| pNZ9520 | pNZ9530 | |

| S. pyogenes | 59 | 4.6 |

| S. agalactiae | 4 | 11 |

| S. pneumoniae | 1 | 10 |

| B. subtilis | 1 | 10 |

| E. faecalis | 3 | 20 |

Cells carried both the reporter vector, pNZ8008, and one of the regulatory plasmids (pNZ9520 or pNZ9530).

Ratio of the β-glucuronidase activity observed after maximal induction to the constitutive activity observed in the absence of nisin.

It was expected that pNZ9520 would have a higher copy number than pNZ9530 because of a deletion in the replication repressor gene (27). Although this was the case in L. lactis (27), we found that it was not true in all of the strains which we used. We compared the amount of linearized plasmids pNZ9520 and pNZ9530 with the amount of the coresident plasmid pNZ8008 by using ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel electrophoresis and/or Southern blot analysis (data not shown). In B. subtilis, pNZ9520 had a copy number similar to that of pNZ8008, while pNZ9530 had a lower copy number. However, in S. pyogenes and in S. pneumoniae, there was no detectable difference between the amounts of pNZ9520 and pNZ9530, and their copy numbers appeared to be much lower than the copy number of pNZ8008. Therefore, the copy numbers of these broad-host-range plasmids, which replicate by a rolling-circle mechanism, cannot be predicted in different species, and the amounts of NisR and NisK expressed from each plasmid cannot be predicted either.

In S. pyogenes cells harboring both the expression plasmid pNZ8008 and the regulatory plasmid pNZ9520, very low constitutive activity was observed in the absence of nisin, and nisin caused about 59-fold induction (Table 2 and Fig. 2A). In S. pyogenes, the regulatory plasmid pNZ9530 was less useful than pNZ9520 because the constitutive activity was high, and little induction was observed (Table 2). In contrast, in the E. faecalis strain carrying pNZ9520, although the constitutive β-glucuronidase activity was low, addition of nisin to the medium resulted in no significant induction (Table 2). In the other strains investigated, the S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, and B. subtilis strains, cells harboring pNZ9520 exhibited such high levels of constitutive β-glucuronidase activity that little induction above these levels was detected in the presence of nisin (Table 2).

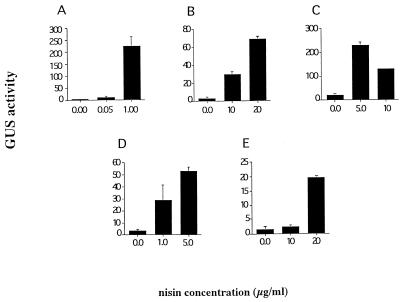

FIG. 2.

Dose response of the nisA promoter. Cells harboring both pNZ8008 and pNZ9520 (A) or pNZ9530 (B through E) were inoculated into media containing different nisin concentrations, and β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity was determined in cell extracts following overnight growth at 37°C. The enzyme activity is given as 1,000 times the increase in absorbance at 420 nm per minute per optical density unit of the culture. (A) S. pyogenes. (B) E. faecalis. (C) S. agalactiae. (D) S. pneumoniae. (E) B. subtilis.

In all of the strains tested in which pNZ9520 caused constitutive nisA promoter activity, the regulatory plasmid pNZ9530 resulted in controlled expression from the nisA promoter (Table 2 and Fig. 2). In response to nisin, 20-fold induction was observed in E. faecalis (Fig. 2B) and 10- to 11-fold induction of β-glucuronidase activity was observed in S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, and B. subtilis (Fig. 2C through E).

The nisin concentration required for maximal induction of the nisA promoter was different for each of the strains. In general, the greatest induction was obtained with a concentration just below the inhibitory level (Fig. 1 and 2). A comparison of the growth curve obtained in the presence of this sublethal concentration of nisin to the growth curve obtained in the absence of nisin showed that the high nisin concentration had no effect on the growth rate (data not shown). The optimal nisin concentrations used for induction were 1 μg/ml in S. pyogenes, 5 μg/ml in S. agalactiae, 1 to 5 μg/ml in S. pneumoniae, and 20 μg/ml in B. subtilis and E. faecalis (Fig. 2). These concentrations are higher than those used to control the system in L. lactis, in which induction was observed with a nisin concentration far below the inhibitory concentration (27).

Characterization of nisA promoter strength.

The level of β-glucuronidase measured with the induced nisA promoter varied considerably among strains, as has been observed previously with Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Lactobacillus species (27). The highest enzyme activity which we found, about 230 U, was observed following nisin induction in the strains of S. pyogenes (Fig. 2A) and S. agalactiae (Fig. 2C). In the inducible S. pneumoniae system, which required nisR and nisK on pNZ9530, the maximal β-glucuronidase activity induced was 55 U (Fig. 2D), which is fivefold lower than the constitutive level observed in the presence of pNZ9520 in this organism (data not shown). In the strains of E. faecalis and B. subtilis tested, the highest induced levels of β-glucuronidase activity were 72 and 18 U, respectively (Fig. 2B and E). These variations may reflect differences in the efficiencies of the transcription and translation machinery of each of the strains tested for recognizing the nisA promoter. Consistent with this idea, identical promoter sequences were found to have significantly different activities in L. lactis and S. pneumoniae or B. subtilis (28, 31). It has also been suggested that differences between the amino acid sequences of the RNA polymerase holoenzymes in different hosts may lead to different affinities for the same promoter sequence (25). In addition, differences in codon usage probably affect the amount of β-glucuronidase produced in the strains studied here.

Comparison of the strength of the nisA promoter to the strengths of the other regulated promoters in B. subtilis.

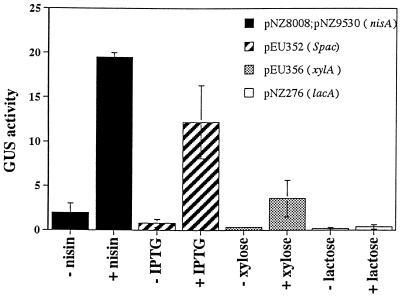

To evaluate nisA promoter strength, we compared the activity of this promoter to the activities of other regulated promoters known to function in gram-positive bacteria. This comparative study was performed first with B. subtilis, because it is the gram-positive organism in which gene expression has been most extensively investigated. In this comparison, we used transcriptional fusions of different promoters to the E. coli gusA gene. To avoid potential differences due to gene dosage, all fusions were carried on the same type of replicon containing the pSH71 origin. The following promoters were studied: the L. lactis nisA promoter, which is regulated by nisin through NisR and NisK; the L. lactis lacA promoter, which is regulated by lactose through the LacR repressor; the B. subtilis xylA promoter, which is regulated by xylose through the XylR repressor; and the chimeric Spac promoter, which is regulated by IPTG through the Lacl repressor. The following plasmids were used (Table 1): pNZ8008 and pNZ9530 (nisin system [see above]); pNZ276, carrying the xylA promoter-gusA transcriptional fusion and the repressor lacR; pEU356, carrying the xylA promoter-gusA transcriptional fusion and the repressor xylR; and pEU352, carrying the Spac promoter-gusA transcriptional fusion and the lacl repressor. To prevent catabolite repression of the promoters that are regulated by sugars (lacA and xylA), all assays were performed in Luria broth containing no sugar source other than that needed for induction. B. subtilis cells harboring the appropriate plasmids were grown under both inducing and noninducing conditions, and the β-glucuronidase activity was determined following overnight growth (Fig. 3 and Table 3).

FIG. 3.

nisA promoter strength in B. subtilis. B. subtilis cells harboring the following plasmids were used: pNZ8008 and pNZ9530 (nisA promoter), pEU352 (Spac promoter), pEU356 (xylA promoter), and pNZ276 (lacA promoter). Cells were grown in Luria broth or in Luria broth supplemented with 20 μg of nisin per ml, 20 mM IPTG, 2% xylose, or 2% lactose. The β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity was determined following overnight incubation at 37°C.

TABLE 3.

Induction of different regulated promoters in B. subtilis and P. pyogenesa

| Promoter | Inducer | Fold inductionb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | S. pyogenes | ||

| nisA (pNZ8008)c | Nisind | 10 | 11 |

| Spac (pEU352) | IPTG (20 mM) | 16 | 4 |

| xylA (pEU356) | Xylose (2%) | 11 | 1 |

| lacA (pNZ276) | Lactose (2%) | 2 | 5 |

Cells were grown in Luria broth (B. subtilis) or L3 medium (S. pyogenes) with or without inducer overnight.

Ratio of the β-glucuronidase activity observed after maximal induction to the constitutive activity (no inducer). For the lacA promoter in S. pyogenes, the constitutive activity was determined with cells grown in L3 medium containing 2% glucose.

Cells carried both plasmid pNZ8008 and one of the regulatory plasmids, either pNZ9530 (B. subtilis) or pNZ9520 (S. pyogenes).

Nisin was used at a concentration of 20 μg/ml with B. subtilis and at 1 μg/ml with S. pyogenes.

Sequence analysis of 236 promoters recognized by the B. subtilis sigma A subunit of RNA polymerase revealed an extended promoter structure (21). The most highly conserved bases include the −35 and −10 hexanucleotide core elements and a TG dinucleotide at positions −15, −14. In addition, several weakly conserved A and T residues are present upstream of the −35 region. All of these elements are found with different degrees of conservation in the four promoters which we tested (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of the sequences of the regulated promoters used in this studya

| Source of sequence | Sequence in the following regions:

|

Spacec | RBS sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −45 | −35 | −15 | −10 | −5 | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | Ta AAAAA | TTGAcA | a A a T TG | TATAAT | AAtAt | AAGGAGG | |

| Spac | TGCAAAAAGTTG | TTGACT | TTATCTACAAGGTGTGG | CATAAT | GTGTGGA | 26 | AAGGAGG |

| nisAb | ATAATAAACGGCT | CTGATT | AAATTCTGAAGTTTGTTAGA | TACAAT | GATTTCG | 26 | AAGGAGG |

| xylA | AAAAACTAAAAAAAATA | TTGAAA | ATACTGATGAGGTTATT | TAAGAT | TAAAATA | 124 | AAGGAGG |

| lacA | TAACAAAAATAG | TTGCGT | TTTGTTTGAATGTTTGA | TATCAT | ATAAACA | 77 | TAGGAGG |

Promoter sequences were aligned by using the −35 and Pribnow regions. The sequence derived from a compilation of 29 promoter sequences of gram-positive bacteria (18a) and the consensus sequence for the ribosome binding site (RBS) are shown. Bases in the consensus sequence that appear in more than 41% of the promoters tested are in lowercase letters, and bases that are present in more than 50% of the promoters tested are in uppercase letters. The bases in the regulated promoters that are the same as the bases in the consensus sequence are indicated by boldface type.

The nisA −35 and −10 regions are based on sequence homology data (9).

The space (in base pairs) between the transcription start site and the RBS is indicated.

In B. subtilis, the nisA, Spac, and xylA promoters were all regulated to similar extents (about 10-fold induction), while expression from the L. lactis lacA promoter was too low to be detected even under inducing conditions (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The maximum induced expression was highest for the nisA promoter.

There are several possible explanations for the differences in the strengths of these promoters. It has been shown that the sequence between the −10 and −35 elements affects promoter strength several hundred-fold (25), probably by altering the context in which these elements are presented to the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. The sequences of the promoters which we compared differ in this spacer region, and this may also have some effect on the strengths of the promoters.

Comparison of the strength of the nisA promoter to the strengths of other regulated promoters in S. pyogenes.

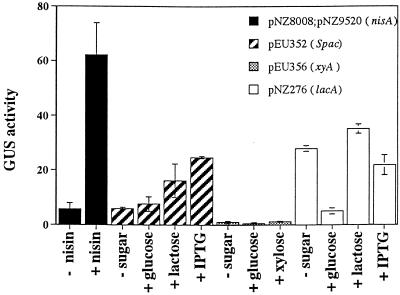

Each of the promoter systems mentioned above was also tested in S. pyogenes to learn whether it could be used to control gene expression in this organism. All assays were carried out in L3 medium with and without inducer. To study the effect of catabolic repression on the promoters that are regulated by sugars, expression from the Spac, xylA, and lacA promoters was also determined in L3 medium containing glucose (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

FIG. 4.

nisA promoter strength in S. pyogenes. S. pyogenes cells harboring the following plasmids were used: pNZ8008 and pNZ9520 (nisA promoter), pEU352 (Spac promoter), pEU356 (xylA promoter), and pNZ276 (lacA promoter). Cells were grown in L3 medium or in L3 medium supplemented with 1 μg of nisin per ml, 2% glucose, 2% lactose, 20 mM IPTG, or 2% xylose. The β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity was determined following overnight incubation at 37°C.

As in B. subtilis, in S. pyogenes the expression driven from the induced nisA promoter was higher than the induced activities of all of the other promoters (specific activity, about 67 enzyme units). The Spac and lacA promoters had lower activities (specific activities, about 35 and 24 enzyme units, respectively), and no activity from the xylA promoter was detectable. nisA and Spac were the only promoters that showed increased activity in response to the inducers. nisA activity was induced 11-fold by nisin, while only 4-fold induction of the Spac promoter was obtained with IPTG. Induction of Spac by lactose was slightly lower than induction by IPTG (Fig. 4).

The levels of expression driven from the lacA promoter in L3 medium and in L3 medium containing lactose were similar; however, these levels of expression were about fivefold higher than the lacA activity in L3 medium supplemented with glucose (Fig. 4). This indicates that the differences in lacA promoter activity resulted from glucose repression rather than induction by lactose. Since lactose did not induce the L. lactis lacA promoter in either B. subtilis or S. pyogenes, it is possible that in these hosts lactose is not processed to the inducer form.

Because the constitutive expression of the lacA promoter was high in S. pyogenes, we investigated the effect of glucose on this system. There was a fivefold reduction in expression from the lacA promoter when S. pyogenes was grown in glucose compared to when it was grown either in the presence of lactose or with no added sugar (Fig. 4). Since the lacA promoter contains a catabolite repression element that is functional in L. lactis (11), it is possible that glucose causes catabolite repression of this system in S. pyogenes as well.

Expression from the uninduced xylA promoter was undetectable in both S. pyogenes and B. subtilis. However, although this promoter was induced in the latter, it was not in the former. We believe that it is likely that xylose does not enter S. pyogenes, since we also found that xylose was not able to serve as a carbon source in this organism. An overnight culture in which glucose was added to L3 medium reached a higher optical density than a culture with no added sugar, while addition of xylose had no effect (data not shown).

Conclusions.

In this study we demonstrated that the lactococcal nisA promoter is recognized in many different gram-positive species, including pathogenic streptococci. In B. subtilis and S. pyogenes, it was the most efficient of the regulatable promoters studied.

For efficient induction, the regulatory protein must be able to interact with the RNA polymerase, whose sequence differs in different bacteria. We have extended the list of species in which NisR is able to activate transcription to include B. subtilis and some of the pathogenic streptococci. We concluded that nisin interacts effectively with NisK in all of these strains since the nisA promoter was regulated by nisin in all species of AT-rich gram-positive bacteria which we studied.

The nisA gene expression system can be moved easily between strains of different species because it is contained on two broad-host-range replicons, and it should provide an alternative to the commonly used Spac promoter, which may not be active in all gram-positive organisms. Furthermore, in strains in which Spac is active, nisA should be compatible with the Spac system to allow independent regulation of different cloned genes. For all of these reasons and because it is the first heterologous regulatable promoter described for pathogenic streptococci, we expect the nisA gene expression system to be extremely useful in the future, especially for genetic studies of important gram-positive human pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to F. Arigoni for plasmid pDG1832 and to Craig Rubens for S. agalactiae COH31. We also thank Robert Feldman for the protocol for transformation of S. agalactiae.

This work was performed during the tenure of a research fellowship to Z.E. from the American Heart Association, Georgia Affiliate, and was supported by Public Health Service grant R37-AI20723.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arigoni, F. 1998. Personal communication.

- 2.Arnold K E, Farley M M, Stephens D S. Infections caused by streptococci and enterococci. In: Hurst J W, editor. Medicine for the practicing physician. Stamford, Conn: Appleton and Lange; 1996. pp. 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennik M H, Verheul A, Abee T, Naaktgeboren-Stoffels G, Gorris L G, Smid E J. Interactions of nisin and pediocin PA-1 with closely related lactic acid bacteria that manifest over 100-fold differences in bacteriocin sensitivity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3628–3636. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3628-3636.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breuer B, Radler F. Inducible resistance against nisin in Lactobacillus casei. Arch Microbiol. 1996;65:114–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bringel F, Van Alstine G L, Scott J R. Transfer of Tn916 between Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strains is nontranspositional: evidence for a chromosomal fertility function in strain MG1363. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5840–5847. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5840-5847.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Genetic manipulation of pathogenic streptococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:556–586. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04028-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craven M G, Henner D J, Alessi D, Schauer A T, Ost K A, Deutscher M P, Friedman D I. Identification of the rph (RNase PH) gene of Bacillus subtilis: evidence for suppression of cold-sensitive mutations in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4727–4735. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4727-4735.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daeschel M A, Jung D S, Watson B T. Controlling wine malolactic fermentation with nisin and nisin-resistant strains of Leuconostoc oenos. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:601–603. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.601-603.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Ruyter P G, Kuipers O P, Beerthuyzen M M, van Alen-Boerrigter I, de Vos W M. Functional analysis of promoters in the nisin gene cluster of Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3434–3439. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3434-3439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Vos W M, Kleerebezem M, Kuipers O P. Expression systems for industrial Gram-positive bacteria with low guanine and cytosine content. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:547–553. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vos W M, Simons G F M. Gene cloning and expression systems in lactococci. In: Gasson M J, de Vos W M, editors. Genetics & biotechnology of lactic acid bacteria. New York, N.Y: Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc.; 1994. pp. 52–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunny G M, Craig R A, Carron R L, Clewell D B. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid. 1979;2:454–465. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(79)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichenbaum Z, Scott J R. Use of Tn917 to generate insertion mutations in the group A streptococcus. Gene. 1997;186:213–217. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman, B. 1998. Personal communication.

- 15.Fischetti V A, Jarymowycz M, Jones K F, Scott J R. Streptococcal M protein size mutants occur at high frequency within a single strain. J Exp Med. 1986;164:971–980. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischetti V A, Jones K F, Scott J R. Size variation of the M protein in group A streptococci. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1384–1401. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frere J. Simple method for extracting plasmid DNA from lactic acid bacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:227–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1994.tb00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gartner D, Geissendorfer M, Hillen W. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis xyl operon is repressed at the level of transcription and is induced by xylose. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3102–3109. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3102-3109.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Graves M C, Rabinowitz J C. In vivo and in vitro transcription of the Clostridium pasteurianum ferredoxin gene. Evidence for “extended” promoter elements in gram-positive organisms. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11409–11415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmann J D. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma A-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2351–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.13.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill J E, Wannamaker L W. Identification of a lysin associated with a bacteriophage (A25) virulent for group A streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:696–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.696-703.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husmann L K, Scott J R, Lindahl G, Stenberg L. Expression of protein Arp, a member of the M protein family, is not sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 1995;63:345–348. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.345-348.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jack R W, Tagg J R, Ray B. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:171–200. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen P R, Hammer K. The sequence of spacers between the consensus sequences modulates the strength of prokaryotic promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:82–87. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.82-87.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karow M L, Piggot P J. Construction of gusA transcriptional fusion vectors for Bacillus subtilis and their utilization for studies of spore formation. Gene. 1995;163:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00402-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleerebezem M, Beerthuyzen M M, Vaughan E E, de Vos W M, Kuipers O P. Controlled gene expression systems for lactic acid bacteria: transferable nisin-inducible expression cassettes for Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Lactobacillus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4581–4584. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4581-4584.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koivula T, Sibakov M, Palva I. Isolation and characterization of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:333–340. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.333-340.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuipers O P, Beerthuyzen M M, de Ruyter P G, Luesink E J, de Vos W M. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27299–27304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuipers O P, de Ruyter P G, Kleerebezem M, de Vos W M. Controlled overproduction of proteins by lactic acid bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez de Felipe F, Corrales M A, Lopez P. Comparative analysis of gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;122:289–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIntyre D A, Harlander S K. Improved electroporation efficiency of intact Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis cells grown in defined media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2621–2626. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2621-2626.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moran C P, Jr, Lang N, LeGrice S F, Lee G, Stephens M, Sonenshein A L, Pero J, Losick R. Nucleotide sequences that signal the initiation of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;186:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00729452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison D A, Jaurin B. Streptococcus pneumoniae possesses canonical Escherichia coli (sigma 70) promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1143–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Casal J, Caparon M G, Scott J R. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component regulatory systems. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2617–2624. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2617-2624.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Platteeuw C, Simons G, de Vos W M. Use of the Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase (gusA) gene as a reporter gene for analyzing promoters in lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:587–593. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.587-593.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubens C E, Wessels M R, Heggen L M, Kasper D L. Transposon mutagenesis of type III group B streptococcus: correlation of capsule expression with virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7208–7212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott J R. A new gene controlling lysogeny in phage P1. Virology. 1972;48:282–283. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Rooijen R J, Gasson M J, de Vos W M. Characterization of the Lactococcus lactis lactose operon promoter: contribution of flanking sequences and LacR repressor to promoter activity. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2273–2280. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2273-2280.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verheul A, Russell N J, Van’T Hof R, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Modifications of membrane phospholipid composition in nisin-resistant Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3451–3457. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3451-3457.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells J M, Wilson P W, Norton P M, Gasson M J, Le Page R W. Lactococcus lactis: high-level expression of tetanus toxin fragment C and protection against lethal challenge. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1155–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson G A, Bott K F. Nutritional factors influencing the development of competence in the Bacillus subtilis transformation system. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:1439–1449. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.4.1439-1449.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yansura D G, Henner D J. Use of the Escherichia coli lac repressor and operator to control gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yother J, McDaniel L S, Briles D E. Transformation of encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1463–1465. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1463-1465.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y B, Ayalew S, Lacks S A. The rnhB gene encoding RNase HII of Streptococcus pneumoniae and evidence of conserved motifs in eucaryotic genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3828–3836. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3828-3836.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]