Abstract

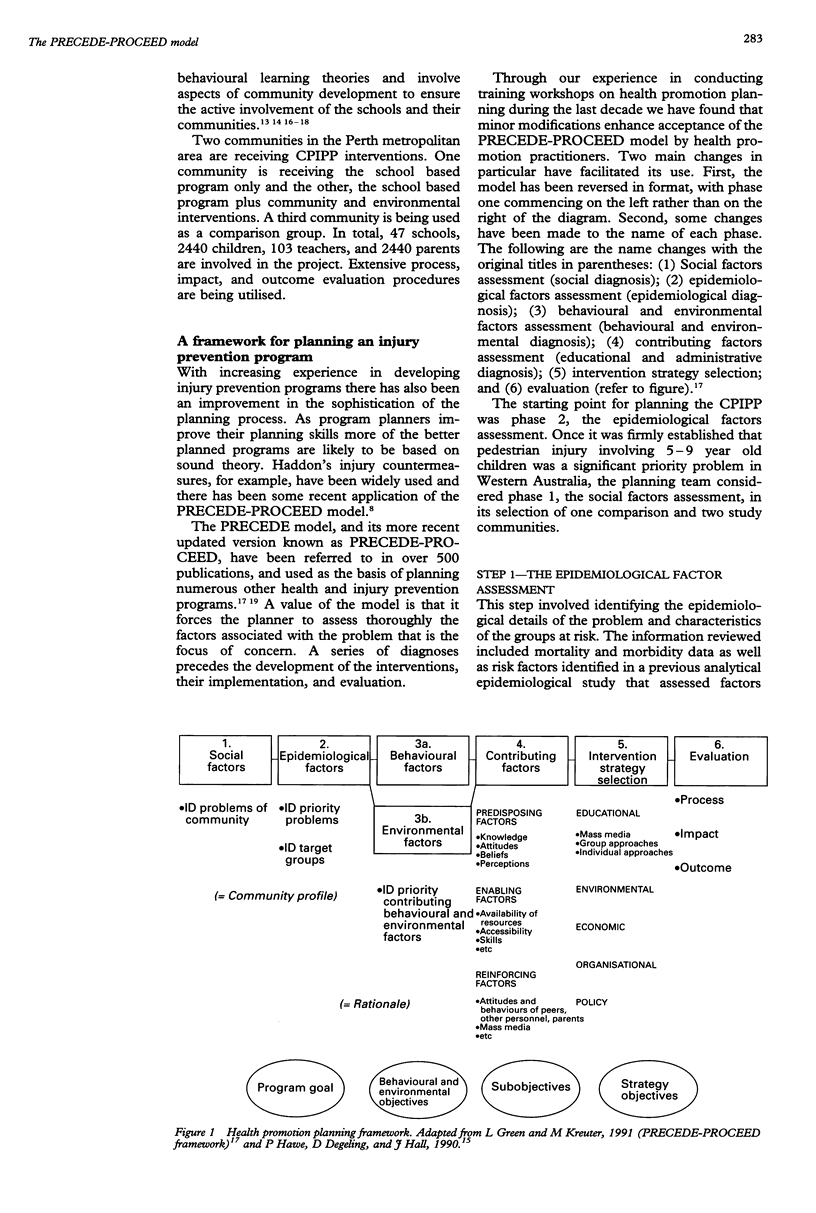

OBJECTIVES: The objectives were first, to modify the PRECEDE-PROCEED model and to use it is as a basis for planning a three year intervention trial that aims to reduce injury to child pedestrians. A second objective was to assess the suitability of this process for planning such a relatively complex program. SETTING: The project was carried out in 47 primary schools in three local government areas, in the Perth metropolitan area. METHODS: The program was developed, based on extensive needs assessment incorporating formative evaluations. Epidemiological, psychosocial, environmental, educational, and demographic information was gathered, organised, and prioritised. The PRECEDE-PROCEED model was used to identify the relevant behavioural and environmental risk factors associated with child pedestrian injuries in the target areas. Modifiable causes of those behavioural and environmental factors were delineated. A description of how the model facilitated the development of program objectives and subobjectives which were linked to strategy objectives, and strategies is provided. RESULTS: The process used to plan the child pedestrian injury prevention program ensured that a critical assessment was undertaken of all the relevant epidemiological, behavioural, and environmental information. The gathering, organising, and prioritising of the information was facilitated by the process. CONCLUSIONS: The use of a model such as PRECEDE-PROCEED can enhance the development of a child injury prevention program. In particular, the process can facilitate the identification of appropriate objectives which in turn facilitates the development of suitable interventions and evaluation methods.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bjärås G. The potential of community diagnosis as a tool in planning an intervention programme aimed at preventing injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 1993 Feb;25(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(93)90091-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders W. D., Kleinbaum D. G. Basic models for disease occurrence in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1995 Feb;24(1):1–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen A. C. Health education and injury control: integrating approaches. Health Educ Q. 1992 Summer;19(2):203–218. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B. H., Schwaitzberg S. D., Seman T. M., Herrmann C. The hidden morbidity of pediatric trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 1989 Jan;24(1):103–106. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Ashton T., Dunn R., Lee-Joe T. Preventing child pedestrian injury: pedestrian education or traffic calming? Aust J Public Health. 1994 Jun;18(2):209–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Norton R., Dunn R., Hassall I., Lee-Joe T. Environmental factors and child pedestrian injuries. Aust J Public Health. 1994 Mar;18(1):43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I., Norton R. Sensory deficit and the risk of pedestrian injury. Inj Prev. 1995 Mar;1(1):12–14. doi: 10.1136/ip.1.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B. G., Brink S. G., Simons-Morton D. G., McIntyre R., Chapman M., Longoria J., Parcel G. S. An ecological approach to the prevention of injuries due to drinking and driving. Health Educ Q. 1989 Fall;16(3):397–411. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]