Abstract

Photosynthesis, as one of the most important chemical reactions, has powered our planet for over four billion years on a massive scale. This review summarizes and highlights the major contributions of Govindjee from fundamentals to applications in photosynthesis. His research included primary photochemistry measurements, in the picosecond time scale, in both Photosystem I and II and electron transport leading to NADP reduction, using two light reactions. He was the first to suggest the existence of P680, the reaction center of PSII, and to prove that it was not an artefact of Chlorophyll a fluorescence. For most photobiologists, Govindjee is best known for successfully exploiting Chlorophyll a fluorescence to understand the various steps in photosynthesis as well as to predict plant productivity. His contribution in resolving the controversy on minimum number of quanta in favor of 8–12 vs 3–4, needed for the evolution of one molecule of oxygen, is a milestone in the area of photosynthesis research. Furthermore, together with Don DeVault, he is the first to provide the correct theory of thermoluminescence in photosynthetic systems. His research productivity is very high: ~ 600 published articles and total citations above 27,000 with an h-index of 82. He is a recipient of numerous awards and honors including a 2022: Lifetime Achievement Award of the International Society of Photosynthesis Research. We hope that the retrospective of Govindjee described in this work will inspire and stimulate the readers to continue probing the photosynthetic apparatuses with new discoveries and breakthroughs.

Keywords: Bicarbonate, Chlorophyll a fluorescence, Emerson enhancement effect, Quantum requirement, Red drop, Water splitting complex

Introduction

Photosynthesis is a process by which plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria capture and store solar energy on a massive scale (Shevela et al. 2018; Blankenship 2021). The great advances in the molecular mechanisms of this amazing natural process have made it possible for artificial means to improve photosynthesis itself and to produce energy, biofuel, and food to address emerging global issues (Hou et al. 2014, 2023; Ort et al. 2022). Govindjee was fascinated by the phenomenon of photosynthesis when he was a graduate student at the University of Allahabad. One of his teachers Prof. Shri Ranjan, who was a student of F.F. Blackman, always motivated the students to go to the library and read scientific articles. While visiting the library, Govindjee came across a 1943 paper by Robert Emerson and Charlton Lewis (Emerson and Lewis 1943), in which he became mesmerized by the phenomenon of the ‘red drop’ in photosynthesis, i.e., inefficient photosynthesis when chlorophyll (Chl a) is the only absorbing pigment. Taking the lead from this, he wrote to Emerson that he would like to join him to do research on this topic in photosynthesis and the rest became history. The sudden unexpected tragic death of Emerson in a plane accident, on February 4, 1959 shattered his dreams. Govindjee and his spouse Rajni Govindjee decided to return to India, but Prof. Eugene Rabinowitch, a physical chemist, offered them research positions under his supervision to continue their research without changing their topics (for Rabinowitch, see Ref. Govindjee et al. 2019). They accepted the offer, finished their Ph. D.s in 1960 and 1961, respectively (Govindjee 1960, 1961), and later became successful in what they dreamt to be. For Rajni’s contributions, (see Ebrey 2015 and Balashov et al. 2023).

Govindjee was born in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, on October 24, 1932. In 1952, he completed his Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.; Botany, Zoology, and Chemistry), and in 1954 his Masters in Botany (Plant Physiology), both in first class. His father was a progressive person, who had decided to drop the family name (Asthana) which indicates the caste of a person. This he did because he wanted to eradicate the caste system and inequality between people which was quite prominent in India at that time. Thus Govindjee has only one name- Govindjee and had much trouble due to this. In view of this, he has recently changed his legal name to be: Govindjee Govindjee (also see the reference Seibert et al. 2022; Jajoo et al. 2023). But his discoveries in the field of photosynthesis have made his name famous and recognized worldwide as Govindjee. The area of photosynthesis that he has enriched, along with many international collaborators, includes the experimental evidence for the presence and operation of two distinct spectral forms of Chl a, each associated with a separate photosystem differing in their photochemical activity. His research during the 1970s and 1980s includes steps in the Z-scheme with the appropriate time sequence of the charge separations and the kinetic model of oxygen evolution (Allakhverdiev et al. 2013).

This current review is an attempt to focus on Govindjee’s research contributions to ‘photosynthesis’. In this tribute paper, we summarize his personal life as well as his research on Photosystem II (PSII), oxygen evolution, Chl a fluorescence, thermoluminescence, artificial photosynthesis, and his so-called ‘Photosynthesis Museum’. After his retirement, in 1999, he is continuing, in his splendid way, participating in research and enriching the knowledge of the magnificent phenomenon of photosynthesis. We also list here the numerous awards and honors received by him for his contributions to photosynthesis research.

Family and education

Savitri Devi, his mother, was a very kind and gentle woman who adhered to strict religious and ritual practices, and Vishveshwar Prasad, his father belonged to ‘Arya Samaj’, a socio-religious movement (See https://www.britannica.com/topic/Arya-Samaj for further information). Being the youngest of four siblings, Govindjee’s entire family had a significant role in shaping him.

In 1953, Govindjee met Rajni Varma when they were students at Allahabad University and she was his junior by one year. On October 24, 1957, while both were Robert Emerson’s Ph.D. students, they were married in Urbana, Illinois. From there onwards, Rajni Govindjee played a major role in his life and early research. They have two children: a son Sanjay Govindjee (a professor in engineering) and a daughter Anita Govindjee (a computer scientist).

From 1943 to 1948, he was a student at Colonelganj High School, Allahabad, right from the 4th class (grade) to the 10th grade (also see the reference Block 2022). After graduating, in first class, from high school, he studied, from 1948 to 1950, at Kayastha Pathshala Intermediate College for his 11th and 12th grade education. He received first class in his 1950 Intermediate Board Exam (to know more about him see Block 2022).

He received his Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree in Botany, Chemistry and Zoology in 1952 and secured first class at the University of Allahabad (see https://www.life.illinois.edu/govindjee/g/CurriculumVitae.html). He was good at taking plant sections rather than animal dissection which also was a factor in choosing botany as his major in his Masters with specialisation in Plant Physiology in 1954.

Govindjee worked as a lecturer in Botany from 1954 to 1956 at the University of Allahabad. In the year 1956, he immigrated to the US with a Fulbright Scholarship to the University of Illinois (see reference Block 2022). He then collaborated with Eugene Rabinowitch earning his Ph.D. in Biophysics in September 1960. After obtaining his doctoral degree, Govindjee worked as a postdoctoral fellow for the United States Public Health (USPH) Service from 1960 to 1961, at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A A photo of the gate of the Botany Department of the University of Allahabad. Courtesy;HarbansKehri Kaur. B A 2006 photo of Rajni and Govindjee, relaxing at Bandelier national monument near Santa Fe in New Mexico, USA; see < https://www.life.illinois.edu/govindjee/g/Photos.html > Source: Govindjee’s Family Archives. C A 2020 photograph of the Natural History building (NHB) of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, as seen from Mathews Avenue. Source: Personal collection of Govindjee D Govindjee standing beside the plaque that honors his professors of photosynthesis Robert Emerson and Eugene Rabinowitch. Source https://www.life.illinois.edu/govindjee/

Photosynthesis research

Existence of two photosystems, photosystem II and oxygen evolution

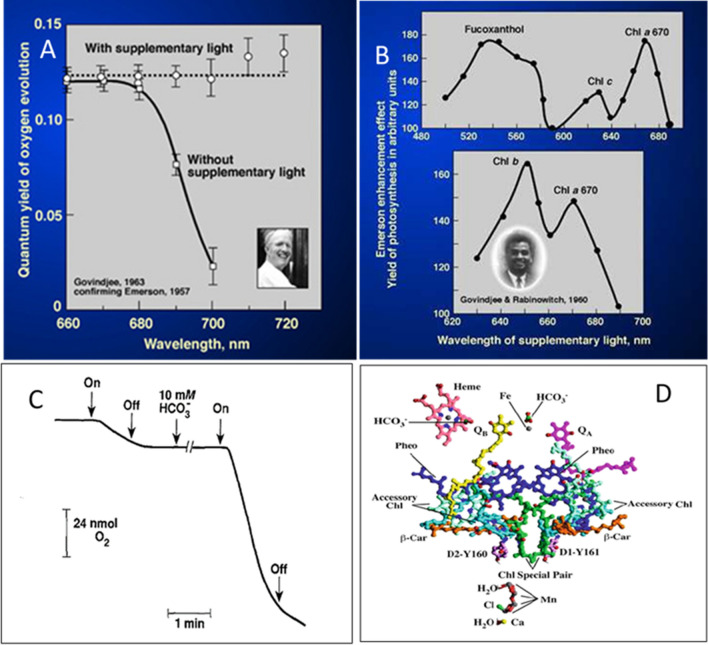

1960s: The discovery of the Red Drop in the quantum yield of photosynthesis beyond 680 nm in 1943 (Emerson and Lewis 1943) and the enhancement effect by the addition of supplementary light of different wavelengths in 1957 (Emerson et al. 1957) led Emerson to the concept of two photosystems in photosynthesis. He speculated that one of the photosystems was driven by Chl a while the other by Chl b (in green algae) and by other accessory pigments (in other systems). The existence of two photosystems and two light reactions was a new concept and was Emerson’s major contribution. However, there was no support for Chl b doing a reaction by itself. The fundamental idea behind photosynthesis was based on the idea that the only source of the photochemical processes in photosynthesis is the excitation energy in Chl a. Louis N.M. Duysens had already shown, in 1952, that accessory pigments, including Chl b, transferred their excitation energy to Chl a. Thus the hypothesis of accessory pigments (including Chl b) driving photosynthesis was not acceptable and was ambiguous (also see Govindjee 2023) for Govindjee’s story in his own words). This ambiguity was cleared by Govindjee in his Ph.D. thesis. Here, he provided the experimental proof for the existence, and function, of two different spectral forms of Chl a in the two photosystems; he used the unicellular Navicula (a diatom), Chlorella (a green alga), Anacystis (a cyanobacterium), and Porphyridium (a red alga) for performing these experiments (Govindjee and Rabinowitch 1960a, b) (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

A Plot of the maximum quantum yield of oxygen evolution in the green alga Chlorella as a function of wavelength of light with and without shorter wavelength of supplementary light. It is from unpublished 1963 data of Govindjee, confirming Emerson et al. (1957) enhancement effect on the “Red drop” of photosynthesis beyond ~ 685 nm, and plotted after correction of light-induced changes in respiration. Source: from presentation by Govindjee (2022) at International Conference at University of Calicut B Action spectra of the Emerson enhancement effect in the diatom Navicula minima and the green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa. It shows the discovery of Chl a 670 in both the organisms along with other pigments (Chl c and fucoxanthol in Navicula and Chl b on Chlorella) in what is now called Photosystem II (PSII). Source: from the presentation by Govindjee (2022) C Bicarbonate stimulation of photosynthetic electron transport in spinach thylakoid suspensions, using methyl viologenas an electron acceptor under aerobic conditions (initial rate, in µequiv. /mg chlorophyll per h, was 145, and after the addition of 10 mM bicarbonate, it was1074); reproduced from Eaton-Rye and Govindjee (1984), and presented by Govindjee (2022). D A model of PSII reaction center showing all cofactors in the PS II reaction center. See the predicted location of one of the bicarbonate ions near the Fe complex between the first plastoquinone electron acceptor QA and the second plastoquinone electron acceptor QB–essential for electron transfer in photosynthesis. Reproduced by Govindjee (2022) from Fig. 2A in

Xiong et al. (1998)

The use of manometry, as used by both Emerson and Govindjee, as an experimental set-up for discovering the enhancement effect led to some questions regarding the findings, since manometry cannot differentiate between the positive changes in the rate of photosynthesis from the negative changes in the rate of respiration. This dilemma was solved by Rajni Govindjee; she made measurements on the Hill reaction in which parabenzoquinone (pBQ) was used, as a respiratory inhibitor, as well as an electron acceptor in Chlorella cells. By using pBQ, not only respiration but also carbon dioxide fixation is inhibited. Rajni observed two peaks, one at 650 nm (for Chl b) and the other at 670 nm (for Chl a) in the action spectrum of the “Emerson Enhancement Effect” (Govindjee 1961). Thus, this effect led to support for the discovery and the existence of two types of Chl a in the photosystems I and II, as we know today (Govindjee and Rabinowitch 1960a, b).

The uncertainty and the dispute over the existence of the reaction center of PSII, labelled as “P680” (for the very first suggestion, see: Krey and Govindjee 1964; Rabinowitch and Govindjee 1965). Some said it was an artefact or Illinois fantasy, and one among them was Warren Butler, who thought that its discovery by Horst Witt’s group in Germany may have been a Chl a fluorescence artifact. This was clearly resolved by Govindjee and Rajni going to Berlin and proving that P680 was not a fluorescence artefact (Govindjee et al. 1970). The perseverance, patience and passion of Govindjee towards photosynthesis gave him the courage to fight against these (and other) battles and win. Rajni Govindjee, using isolated spinach chloroplasts clearly showed, in collaboration with George Hoch, the existence of the Emerson enhancement effect in NADP reduction, thus giving proof to the existence of two pigment systems and two light reactions in chloroplasts (Govindjee et al. 1962, 1964). In addition, using mass spectroscopy Govindjee and co-workers (Govindjee et al. 1963) proved that the Emerson Enhancement Effect was only in photosynthesis, not in respiration.

1970s and 1980s: Govindjee became interested in the primary photochemistry of both PSI and PSII, their charge separation, identification of the very first intermediate and the rate of charge separation. He was also in search of the minute details and performance of the oxygen-evolving or water-splitting complex (Eaton-Rye 2013). His collaboration with James (Jim) Fenton (who was then his graduate student, and had devised a picosecond transient absorption spectrometer in Ken Kaufman’s Laboratory in the Chemistry Department at UIUC) led to the first-ever measurement of PSI photochemistry. With Michael (Mike) R. Wasielewski (Argonne National Laboratory), and Michael (Mike) Seibert (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL), he made the dreams come true for PSII (Eaton-Rye 2007; Seibert et al. 2022). The rate of primary charge separation in the PSII reaction center (RC) was measured in isolated PSII RC from spinach. The earlier PSII RC preparations made by Govindjee and Wasielewski were photo labile, and thus they were not able to monitor the primary charge separation event there; they were then using the method of Nanba and Satoh (Nanba and Satoh 1987). Later Govindjee initiated collaboration with Seibert, who was also working in the same direction. Seibert was able to stabilize the isolated PSII RC preparations, thus they were able to measure the rate of primary charge separation between P680 (the primary electron of PSII) and pheophytin, one of the earliest electron acceptors of PSII (Wasielewski et al. 1989a, b).

There are a lot of models that explain the oxygen evolution from water by PSII. Mar and Govindjee proposed a new kinetic model for oxygen evolution during photosynthesis and reviewed all the available models (Mar and Govindjee 1971). Later, Govindjee et al. 1978 reviewed the significance of Mn and Cl ions in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. To monitor the S states of the Mn- containing oxygen clock (Kok’s oxygen clock), Govindjee explored the technique of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) relaxation measurement in isolated chloroplasts, prepared from pea leaves (Wydrzynski et al. 1978). This was the initial solid experimental proof, albeit a bit indirect, showing changes in oxidation states of Mn during photosynthesis; they had observed a clear period 4 oscillations in proton relaxation rates. Further, the replacement of chloride with fluoride (19F) gave clear experimental proof for the role of chloride in O2 evolution. Thus, this pioneering work by Govindjee and his co-workers helped a lot in shaping our understanding of the oxygen evolution process as known then.

The perplexing topic of how many quanta are necessary for the evolution of one molecule of oxygen in photosynthesis first surfaced in the twentieth century. Many researchers tried their best with scientific explanations and experimentation to tackle this problem. German physiologists Otto Warburg and Erwin Negelein (1923) reported that a minimum of 4 to 5 quanta of light are needed to make one molecule of photosynthetic oxygen. This Warburg-Negelein estimate of 4 to 5 quanta was not questioned until the end of the 1930s. This value obviously matched the theoretical computation since for the evolution of one oxygen molecule, four electrons need to be removed from 2 molecules of H2O, and Albert Einstein’s law of photochemical equivalency meant one photon will do one photoact, i.e., move one electron. In contrast to 3–4 quanta, Robert Emerson measured the minimum number of quanta needed for one oxygen molecule formed in photosynthesis to be 8–12; this study was conducted by Emerson in 1943 while he was doing research, with the help of Charlton Lewis, at Stanford’s Carnegie Institute of Washington (Emerson and Lewis 1943).

Warburg and Emerson attempted to resolve their disagreement, but they were never able to agree on the minimal number of quanta per oxygen evolved during photosynthesis. Beginning in the middle of the 1930s, some researchers did experiments using various techniques and reported the higher (8–10) values for the minimum quantum requirement of photosynthesis (Hill and Govindjee 2014). The list includes Manning et al. (1938), who reported a minimum requirement of 16–20 quanta, and Magee et al. (1939) who observed 12 quanta. According to Arnold (1949), the minimal amount of light quanta needed to produce one oxygen molecule was not less than nine. A thorough analysis of the early to mid-twentieth century attempts to measure the minimum quantum requirement has been presented by Nickelsen and Govindjee (2011) -almost all supporting 8–10 quanta (Emerson), not 3–4 quanta (Warburg) per O2 released.

Chlorophyll a fluorescence

The most exciting aspect of Govindjee's job, in his words, was "to play with the red light that the plants throw out" when they are exposed to shorter wavelengths of light; this is Chl a fluorescence. After retiring in 1999, he has continued working in this area of study, publishing numerous papers, involving different Chl a fluorescence techniques and analytical methodologies; in addition, he has been writing reviews and book chapters on this topic. The well-known book “Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis” (edited by him and his Ph.D. student, the late George Papageorgiou) begins with the chapter “Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Little Background and History” and then moves on to chapters written by leading experts on a variety of applications of Chl a fluorescence techniques and analytical methods in the study of various photosynthetic processes, including excitation energy migration, primary reactions in photosynthesis, charge separation, thermoluminescence, water oxidation, and delayed fluorescence (see Kalaji et al. 2012; Stirbet and Govindjee 2011, 2016, for further information). In fact, Govindjee has worked with uncommon but important fluorescence techniques in his research on photosynthesis. As an example, he has emphasized NPQ (i.e., non-photochemical quenching of the excited state), that has proven to be crucial for understanding the regulatory mechanisms in photosynthesis. This research area of NPQ has identified and characterized the production of a quenching complex in PSII antenna with a relatively lower fluorescence lifetime, which was connected to the xanthophyll cycle-dependent quenching of PSII in plants (Matsubara et al. 2011; Schansker et al. 2003). Later, Govindjee and the late Robert M. Clegg (Department of Physics, at the UIUC) began to exploit fluorescence lifetime measurements, and they published a novel fluorescence method for studying photosynthesis, i.e., Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) (Holub et al. 2007).

The initial (minimum) fluorescence FO and an early inflection point of the transient curve at 2 ms illumination, which they designated ‘J’, were measured with great precision using a shutterless fluorometer device (Govindjee 1995). In this transient, ‘O’ represents the origin (FO), ‘J’ (FJ) and ‘I’ (FI) represent the fluorescence inflections at 2 and 30 ms, respectively, whereas, ‘P’ represents the peak (FP, which is maximum fluorescence, Fm, in saturating light), ‘S’ represents a semi-steady-state level, ‘M’ represents a later maximum, and ‘T’ represents the terminal steady state. Historically, Govindjee has been associated with the O-J-I-P-S-M-T transient’s current designation from the very beginning. Schansker et al. (2003) measured the O-J-I-P transient curves on many different plants, including Beta vulgaris, Camellia japonica, and Pisum sativum, and, this, simultaneously with the 820-nm transmission signal, the latter reflecting changes in P700, the reaction center of PSI. This allowed Govindjee and his collaborators to obtain, in parallel, additional data on P700, the primary electron donor of PSI, and plastocyanin (PC), which reduces P700+. These findings demonstrated that PC decreases after darkness and that its species-dependent contributions to the 820-nm signal range from 40% in sugar beet to 50% in pea and camellia plants.

Additionally, Yusuf et al. (2010) discovered, by analysing Chl a fluorescence, that transgenic Brassica juncea plants overexpressing a tocopherol methyl transferase (TMT) gene from Arabidopsis thaliana exhibit increased tolerance to various types of induced stress (i.e., salt, heavy metal, and osmotic). This effect was assumed to be brought on by higher levels of total tocopherol. Further, Chen et al. (2012) investigated the effects of a new photosynthetic inhibitor (tenuazonic acid, TeA) on Crofton weed and evaluated changes in the O-J-I-P transients on this plant using photoaffinity labelling with a radioactive method. The outcome of these tests showed that TeA does, in fact, bind to the QB binding site and prevents electron transport through QA. Despite their ability to serve as herbicides, experiments with [14C]-atrazine showed that TeA binds to a different location on PSII than atrazine does. All these complex results still need to be further examined.

On the other hand, Shabnam et al. (2015) investigated differences in photoinhibition between long-leaf pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus) leaves that were floating and those that were immersed. Floating leaf chloroplasts had a higher rate of photosynthetic electron transport, a higher maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry, and a higher level of PSI activity, as determined by the ratio between the variable fluorescence (Fv) and the maximum fluorescence (Fm). Additionally, under bright light, these leaves showed less photoinhibitory damage. Further, the cells of the floating leaves possessed a higher mitochondria/chloroplast ratio and an alternative oxidase in comparison to the cells of the submerged leaves. These experimental findings led Shabnam et al. (2015) to conclude that the floating leaves had a superior defense against photoinhibition for the photosynthetic apparatus because of a favourable connection between the mitochondria and chloroplasts. The JIP-test (for Chl a fluorescence transient) was, and is, a novel approach that Strasser and Strasser (1995) had earlier proposed for the investigation of the O-J-I-P transient. It was further refined by Merope Tsimilli-Michael and Reto Strasser in Switzerland. In order to calculate the parameters that largely characterise PSII activity, this method uses a number of chosen fluorescence parameters. Further, Shabnam et al. (2015) examined a number of potential uses for the energetic connection of PSII; additionally, these authors computed the JIP parameters using well- thought out assumptions and approximations. Chl a fluorescence induction was utilized to explore several kinds of abiotic stressors based on the results of these investigations- a rather promising approach (Demmig-Adams et al. 2014).

Following retirement in 1999, Govindjee co-authored several articles on Chl a fluorescence with Alexendria (Sandra) Stirbet that have offered newer perspectives on its significance and use. Stirbet et al. (2014, 2019) discussed Chl a fluorescence induction modelling and its relationship to photosynthesis and the “ins” and “outs” of the different current models of Chl a fluorescence. Stirbet and Govindjee (2012) discussed the disagreement over the cause of the variable PSII fluorescence and the J-I-P phase of the fluorescence transient. The Chla fluorescence of all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms increases quickly at the beginning, and Govindjee's reviews elegantly and simply describe the reasons behind it all. The claim here is that a decrease in [QA] is both necessary and sufficient to reach Fm in all of the active PSII centers. This model was demonstrated to be highly successful and is often used in labs throughout the world since it was supported by data on diverse species under a wide range of environmental and experimental situations. However, some experimental results could be challenging or even impossible to explain in terms of this widely accepted idea. Govindjee keeps an open eye on these developments, and with his extensive knowledge and impressive expertise, he will definitely be able to shed some new light on this matter and provide a better grasp of the underlying physical mechanics.

Bicarbonate in photosynthesis

Govindjee had a fervent desire to solve the vagueness with regard to the importance of bicarbonate in oxygen evolution. During the 1960s, Warburg and Krippahl discovered that during Hill reaction, when ferricyanide was used as an electron acceptor, the rate of oxygen evolution in isolated chloroplast was dependent on the presence of CO2 (Warburg and Krippahl 1960). Even though several scientists continued to work on this phenomenon, a clear picture was not developed. But in every experiment conducted the importance of CO2 was confirmed, but its significance was not deciphered. Little was known about the active species (CO2 or HCO3−) and the site of action in the electron transport chain. Govindjee gave a lecture about this, in a graduate level course on ‘Photosynthesis’, at the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, and one of his graduate students Alan Stemler became interested and took this problem for his Ph.D. thesis entitled “The bicarbonate ion and photosynthetic oxygen evolution” (Stemler 1965). He used chloroplasts from maize and oats to study the phenomenon; Stemler attempted to figure out the site of action of bicarbonate, by heating chloroplasts to stop oxygen evolution. He confirmed the role of bicarbonate in oxygen evolution and this was a shred of direct experimental evidence and a foundation for further work in this direction (Stemler and Govindjee 1973). But the use of diphenyl carbazide (DPC), and dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP) to study the importance of bicarbonate on the acceptor side of PSII did not provide any further clue. However, experiments of Wydrzynski and Govindjee (1975) on Chl a florescence transients, and of Govindjee et al. (1976) on fluorescence changes after a different number of flashes gave the clear conclusion that bicarbonate was needed for the formation of plastoquinol on the QB site, which is on the electron acceptor site of PSII. In addition, the extensive work of another Ph.D. student Julian Eaton-Rye clinched the idea that one of the major functions of bicarbonate was indeed, as hinted above, on the electron acceptor side of PSII (Eaton-Rye 1987; Eaton-Rye and Govindjee 1988a, b) (Fig. 2C).

Another student of Govindjee, Rita Khanna, probed again the site of action of bicarbonate in chloroplasts. Through biochemical experiments, she confirmed the site of action of bicarbonate, to be between QA and the formation of PQH2 in the electron transport chain (Khanna et al. 1977). Further, her experiments also gave clear supporting data for the hypothesis on the interaction of bicarbonate with essential proteins mediating electron flow between QA and the formation of PQH2 (Khanna 1980; Khanna et al. 1980). Later, another student of Govindjee, Jiancheng Cao demonstrated the same effect of bicarbonate in cyanobacteria, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Cao 1992). Govindjee and others have, by now, extended the concept of the influence of the bicarbonate on PSII in all oxygenic photosynthetic organisms.

Jin Xiong, the last Ph.D. student of Govindjee, focussed on the bicarbonate effect in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. He examined the role of arginine 257 and 269 of the D1 protein for this effect; he concluded that these amino acids are located near the proposed bicarbonate binding site. The mutants, where arginine 269, near the non-heme iron binding site, was changed to glycine, were unable to grow photo-autotrophically; here, both the acceptor and the donor side of the PSII were altered. Thus it was proposed that this site has some role in bicarbonate binding, and it is evident from the experiment that bicarbonate is required for the activity of PSII. However, the mutants where arginine-257 was changed to glutamate and methionine were able to live photo-autotrophically but showed a slower growth rate, with the acceptor side of the PSII affected. Further, bicarbonate binding was very low in these mutants, which indicates the essentiality of this region for bicarbonate binding (Xiong 1996). To elucidate the mechanism of bicarbonate binding in PSII, a computational model for the reaction centre of C. reinhardtii and of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, was made by Govindjee and Jin Xiong in collaboration with Shankar Subramaniam (Xiong et al. 1998). This led to a model of putative bicarbonate mediated catalytic protonation, also a bicarbonate transport channel, for the movement of bicarbonate and water molecules to PSII (Fig. 2D). Thus through collaboration and extensive research work, Govindjee was able to establish the importance of bicarbonate in PSII, particularly on the electron acceptor side of PSII and on oxygen evolution (Shevela et al. 2012). We are told that currently, Govindjee is quite interested in knowing in what way (or ways) bicarbonate functions on the electron donor side of PSII as he, himself, has observed effects on that site. This is now an important topic of research.

Thermoluminescence

Thermoluminescence is a light emitting property displayed by some crystalline substances when they are previously exposed to radiations of high energy. Electron displacements, taking place inside the crystal lattice upon irradiation to high-energy radiation result, in the release of light energy (Govindjee et al. 1997). Several biological systems are known to produce thermoluminescence. The ability of dried chloroplasts to produce thermoluminescence was initially discovered by William Arnold, and Helen Sherwood (1957). It was later found that all photosynthetic organisms share this characteristic. When pre-illuminated photosynthetic sample is warmed, thermoluminescence takes place at a temperature that corresponds to the energy level of the charge separated state (Vass and Govindjee 1996). Here, we give a brief overview of Govindjee’s innovative achievements in the application of thermoluminescence in photosynthetic research.

In pre-illuminated spinach chloroplasts and cells of Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Mar and Govindjee (1971) observed that temperature- jump caused the back reaction of PSII of photosynthesis, which was, a significant new observation. However, in collaboration with Don DeVault, Govindjee provided the first correct theory of how thermoluminescence is produced in photosynthetic systems (DeVault et al. 1983), which was possible because of earlier experimental observations with the research group of P.V. Sane (Tatake et al. 1981). According to Govindjee et al. (1985), the Q and B bands of thermoluminescence curve appear at temperatures of 35 °C and 50–55 °C, respectively in thermophilic cyanobacteria. Consequently, the charge pair that causes the peak's emission cannot be determined from its TM alone. DeVault and Govindjee (1990) established a foundation for connecting changes in the redox potentials of the participating charge pairs to changes in total free energy resulting from shifts in the TM (Absolute Temperature at maximum intensity of a thermoluminescence band) of the glow peaks. Additionally, despite without knowing the actual redox potentials of the redox carriers, one can deduce changes in their mid-point potentials according to this relationship. Data on thermoluminescence have immense importance in understanding the photosynthetic activity of organisms and Govindjee is greatly acknowledged for his incredible research contributions in this area. Hopefully, others, will exploit thermoluminescence in their future studies.

Artificial photosynthesis

Artificial photosynthesis is any chemical process that replicates natural photosynthesis by absorbing and conserving the energy from sunlight in the chemical bonds of e.g., a photovoltaic source. Photocatalytic water splitting is one of the processes that contributes to artificial photosynthesis. One of the fundamental processes that contributes to artificial photosynthesis is photocatalytic water splitting. Govindjee's golden eyes have already recognized the potential of the water-splitting mechanism (PSII), upon which he has written numerous papers since 1999. The same interest has led him to shed light on a young researcher’s mind, prompting the researcher to investigate the significance of irreplaceable manganese in PSII. The results of this investigation were so astounding that Mahdi Najafpour, proposed oxide forms of manganese mono-sheets as a feasible solution for simulating the function of PSII’s Mn4CaO5 (tetra-manganese calcium penta-oxygenic) cluster (Najafpour and Govindjee 2011; Najafpour et al. 2012b). In this field of study, Govindjee has co-authored a number of interesting papers, such as literature reviews that highlight the significance of hydrogen production by water splitting complexes, which subsequently aid in artificial photosynthesis (Najafpour et al. 2012b), and research papers on artificial photosynthesis that discusses the function of water splitting complexes (Najafpour and Govindjee 2011; Najafpour et al. 2012a; Hou et al. 2014; Hou and Allakhverdiev 2023). In addition, Govindjee once again contributed to the field of artificial photosynthesis in 2019 by actively participating in and promoting the international conference on “From the Biophysics of Natural and Artificial Photosynthesis to Bioenergy Conversion” that was held in the USA (Kaur et al. 2020). In addition to the aforementioned research, Govindjee has also edited a book (Shevela et al. 2018) and a special issue in the journal Frontiers in Plant Science (Vass and Govindjee 1996) devoted to this topic.

Photosynthesis museum

Govindjee is an archivist of important discoveries in the field of photosynthesis. Govindjee's laboratory has always been a place of great companionship where he offered his students the freedom to pursue their scientific interests. His office suite has a massive collection of documents, reports, artifacts, and photos related to photosynthesis research (Jajoo et al. 2009; Eaton-Rye 2013). He keeps gathering papers, posters, letters, books, photographs, and artifacts, and he frequently writes about interesting developments in photosynthesis research. He has documented the development of photosynthesis research through interviews, tributes, obituaries, personal thoughts, and news from experts from all around the world. A large portion of this documentation was made available via Photosynthesis Research's "Historical Corner" section (Eaton-Rye 2019).

At the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, Govindjee's room is rich with history. A tour of Govindjee's office is comparable to an excursion to a museum. A cabinet of curiosities is waiting for the visitors to share with them the saga of photosynthesis research. Even though Govindjee has used the most modern equipment, he has kept wonderful old instruments from a time when instrument-making was still considered an art. There is a rare collection of microscopes used by Govindjee and his colleagues from the 1950s, the times of Robert Emerson and Eugene Rabinowitch to observe algal cells. There is a dodecahedron with 12 photocells which was used for demonstrating the presence of various spectral forms of Chl a. This instrument was made by Carl Cederstrand, Govindjee’s former graduate student. Govindjee’s collections include a flask containing the copper sulphate solution used for filtering out heat from white light, a hand-held spectroscope for testing the spectral distribution of light, a syringe for transferring algal cells, an electrometer for measuring low light intensities, feathers for dusting glass vessels, a manometer, capillary tube, glass filters, a distillation column and a telescope that were used in early photosynthesis research. Govindjee still has the blackboard used for the weekly evening seminars held in his living room at 1101 McHenry Street, Urbana (Eaton-Rye 2007).

An excerpt from Diana Yates' article (https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/801235): “Govindjee retains a clear catalogue of almost every genius who had contributed towards unveiling the puzzle of photosynthesis machinery in plants and algae” (Yates 2019, 2022). Photos of these scientists with scribbled notes mentioning their names, contributions, and life history are displayed on the walls like: “Andy Benson, co-discoverer of Carbon Fixation Cycle. September 24, 1917–Feb. 6, 2015. A dear friend”. The “museum” is loaded with the devices and instruments that were used decades back, but still remain as ageless “innovative lusters”. Govindjee’s treasures also include Robert Emerson’s 1927 Ph.D. dissertation on “Cyanide-insensitive respiration in Chlorella”, who was his mentor at UIUC during his early stages of research. There is a yellow logbook with a list of the names of people who visited Govindjee’s lab over the years (some of the above items are now in the archives of the UIUC). Hanging on the door just outside the office, there is a large hand-painted diagram of photosynthesis which was made in the early 1960s. From a conference in the early 1970s, a researcher wrote on Govindjee’s poster that the photosynthesis pathway, particularly the existence of “P680”, reaction center of PSII, proposed by Govindjee is nothing but an “Illinois Fantasy”. This chart still hangs in a prominent space in the suite (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A A collection of reports, images, papers, and artefacts related to the study of photosynthesis found in Govindjee's office suite-Photo by Fred Zwicky. B Dodecahedron constructed by Carl Cederstrand (Govindjee’s former graduate student), which was used to demonstrate the physical existence of different spectral forms of chlorophyll a. C Coloured filters used by researchers for measuring photosynthesis under different wavelengths of light. D A device to provide far-red light, used to discover two light reactions and two pigment systems involved in photosynthesis. E A portable hand spectroscope for measuring the spectral distribution of light during photosynthesis studies- Photos by Fred Zwicky (see https://las.illinois.edu/news/2019-09-27/govindjees-photosynthesis-museum; Yates D 2022)-with permission

Publications

Govindjee’s research career includes nearly 600 research articles and has a total citation of above 30,000 with an h-index of 86 (we note upfront that this is so when in a large number of papers, his name is automatically deleted because of the use of one name only). Together with the Late M.M. Laloraya, he co-authored his first research paper in the journal "Nature" titled "Effect of Tobacco Leaf-curl and Tobacco Mosaic Virus on the Amino Acid Content of Nicotiana sp."(Laloraya and Govindjee 1955). His most cited (1658) work is his 1969 “Photosynthesis” book in which Eugene Rabinowitch is a co-author, who was Govindjee’s professor for his Ph.D. (Rabinowitch and Govindjee 1969). With him, Govindjee has published many articles and one of them is “Two forms of chlorophyll a in vivo with distinct Photochemical Function” (Govindjee and Rabinowitch 1960c) published in Science. Along with Rabinowitch and with Jan B. Thomas, who temporarily was his official Ph.D. advisor, Govindjee published “Inhibition of photosynthesis in some algae by extreme-red light” which was also published in Science (Rabinowitch et al. 1960). And his most cited (1526) research article is “Polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence transient in plants and cyanobacteria” (1995) with Alaka Srivastava and Reto J. Strasser in ‘Photochemistry and Photobiology’ (Srivastava et al. 1995).

What is important, from the point of view of education, is that Govindjee has published three articles in Scientific American (Rabinowitch and Govindjee 1965; Govindjee and Govindjee 1974; Govindjee and Coleman 1990). In addition, the books titled ‘Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis’; ‘Discoveries in Photosynthesis’; and ‘Photosynthesis in silico: Understanding Complexity from Molecules to Ecosystems’ are all part of Govindjee and his colleagues very successful ‘Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration’ book series, which were published in 2004, 2005 and 2009, respectively (Papageorgiou and Govindjee 2004; Govindjee et al. 2005; Laisk et al. 2009). Govindjee, with his collaborators, has produced one of the best Z-scheme graphical depiction of the origin of the two photosystems and two light reactions that has progressively developed over many years in Photosynthesis Research in 2017 as a part of his educational paper series (Govindjee et al. 2017).

The list of Govindjee’s co-authors has scientists from almost all part of the earth which indicates the world wide acceptance of his work. This list includes researchers from USA, India, China, Russia, Germany, France, The Czech Republic, The Netherlands, Japan, Canada, Hungary, Mexico, UK, Australia, Finland, Azerbaijan, Israel, Sweden, Switzerland, Greece, Iran, Poland, Slovak Republic, Belgium, Estonia, Egypt, Bulgaria, Korea, Norway, and New Zealand. This list shows his willingness to help young researchers and scientists to get in-depth insight in the field of photosynthesis.

Honors and awards

Govindjee has received numerous awards and honors. In 1976, he became a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). He received the Distinguished Lecturer Award from the University of Illinois at Urbana-School Champaign's of Life Sciences in 1978. In 1979, he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences of India as a Fellow and Life Member. For this publication, we emphasize his election as President of the American Society for Photobiology in 1981. On December 2, 2002, the Indian Society of Plant Physiology, the Indian Society of Photobiology, and the Society for Plant Physiology and Biochemistry honored him for his “Lifetime Contributions in the Field of Photosynthesis” with a Symposium on “Light and Life” at the School of Life Sciences (SLS), Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, India. Govindjee was the first recipient of the Rebeiz Foundation for Basic Research’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the International Society of Photosynthesis Research's Communication Award in 2007, and the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign’s Alumni Achievement Award in 2008.

In honor of Govindjee's 80th birthday, “Photosynthesis Research” released a tribute to his life's efforts in photosynthesis in 2013. In 2016, the Indian Society for Plant Research presented him with the Dr. B.M. Johri Memorial Award. The National Academy of Agricultural Sciences of India then elected Govindjee as a Pravasi (Foreign) Fellow in 2018, and a special issue of Photosynthetica was released to celebrate his 85th birthday. An article on his photosynthesis research and the "Photosynthesis Museum" was published by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2019.

In 2022, Govindjee received the highly prestigious lifetime achievement award from the International Society of Photosynthesis Research (ISPR); he is the second American to get this. Award, the first one was the Late Kenneth Sauer of UC Berkeley (see Nonomura and Kumar 2022). In addition, and to our delight, a special issue of ‘Plant Physiology Reports’ was published celebrating his 90th birthday; see the Editorial by Ort et al. (2022), and the papers therein on the topic of ‘Photosynthesis: diving deep into the process in the era of climate change’, which is very dear to Govindjee’s current interest.

Finally, Govindjee was honored at the international conference on “Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms for Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants” jointly organized by the Department of Botany, University of Calicut, Kerala and Indian Society for Plant Physiology (ISPP, South Zone) held in Kerala, India on the occasion of his 90th birthday (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A 2022 Photograph taken during International Conference cum Workshop on ‘Physiological and molecular mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance in plants’ conducted at University of Calicut, Kerala, India, from October 26 to November 4, 2022. Coinciding with this event, Govindjee’s 90th birthday was celebrated. Left to right Dr.Umesh Bageshwar, Dr.Gomathi R, Dr. Shakira A. M, Dr. Sylvia Z Toth, Prof. P. Pardha Saradhi, Prof. A. S. Raghavendra, Prof. Rajagopal Subramanyam, Dr. M.B Chetti, Prof. Jos T. Puthur, Dr. Om Parkash Dhanker, at the background on top left Prof. Govindjee can be seen, he joined the meeting online through zoom meeting

Conclusion

Govindjee’s passion and perseverance to understand and elucidate the mechanism of photosynthesis has shaped our current understanding of this phenomenon. Now on his 90th birthday, and even now, he is continuing his legacy by inspiring and giving insights into the minute details of photosynthetic research. He even invites young minds to continue research in this direction and even tells them to challenge his ideology, so that greater findings and achievements can be obtained in this direction. One of his greatest dreams is to realise artificial photosynthesis as an eco-friendly, renewable source of energy. We are indebted to him for his countless contributions to the world of knowledge on the basics of photosynthesis and, more importantly, on its future use for the benefit of us all.

Acknowledgements

VM, SPP, SGN, NL, ARKP, AMS, RJ, JJ, AKS and JTP thank the University of Calicut for providing all the resources to carry out this work. VM, NL, ARKP, JJ thank the University Grant Commission (UGC) for providing fund in the form of JRF and SRF. AMS and AKS thank the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India (CSIR) for providing fund in the form of JRF and SRF. RJ thank Bayers MEDHA Fellowship Program (PHD- 2023-10454) in the form of JRF.We all thank Govindjee for sharing his own articles (Govindjee 2019a, 2023) and for reading this article before its publication.

Author contribution

All the authors declare to have made substantial contributions to the article conception; Writing- original draft preparation: VM, SPP, SGN, NL, ARKP, AMS, RJ, JJ, AKS; Figure setting: ARKP, AMS, VM; Writing- Review and Editing: VM, SPP, JTP and HJMH; Supervision: JTP, HJMH.

Funding

VM, NL, ARKP, JJ thank the University Grant Commission (UGC) for providing fund in the form of JRF and SRF. AMS and AKS thank the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India (CSIR) for providing fund in the form of JRF and SRF. RJ thank Bayers MEDHA Fellowship Program (PHD-2023-10454) for providing fund in the form of JRF.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Harvey J. M. Hou, Email: jtputhur@yahoo.com

Jos T. Puthur, Email: hhou@alasu.edu

References

- Allakhverdiev SI, Shen JR, Edwards GE. Special issues on photosynthesis education honoring Govindjee. Photosynth Res. 2013;116:107–110. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W. A calorimetric determination of the quantum yield in photosynthesis. In: Franck J, Loomis WE, editors. Photosynthesis in plants. Ames: Iowa State College Press; 1949. pp. 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W, Sherwood HK. Are chloroplasts semiconductors? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1957;43:105–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balashov S, Ella Imasheva E, Misra S, Masahiro K, Liu S, Govindjee Govindje G, Ebrey TG. Contributions of Rajni Govindjee in the life sciences: celebrating her 88th birthday. Int J Life Sci. 2023;12(1):1–14. doi: 10.5958/2319-1198.2023.00001.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship RE (2021) Molecular mechanisms of photosynthesis, 3rd edition (Wiley).

- Block JE. Life of Govindjee, known as Mister Photosynthesis. J Plant Sci Res. 2022;38(1):1–22. doi: 10.32381/JPSR.2021.38.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J (1992) Effects of amino acid residue substitutions on bicarbonate function in the plastoquinone reductase in cyanobacteria. PhD Dissertation, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Chen S, Strasser RJ, Qiang S, Govindjee G (2012) Tenuazonic acid, a novel natural PSII inhibitor, impacts on photosynthetic activity by occupying the QB-binding site and inhibiting forward electron flow. In: Lu C (ed) Photosynthesis: research for food, fuel and future-15th international conference on photosynthesis, symposium. Zhejiang University Press (China), Springer, pp 453–456. 10.1007/978-3-642-32034-7_93

- Demmig-Adams B, Garab G, Adams W, Govindjee G. Non-photochemical quenching and energy dissipation in plants, algae and cyanobacteria. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DeVault D, Govindjee G. Photosynthetic glow peaks and their relationship with the free energy changes. Photosynth Res. 1990;24:175–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00032597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVaunlt D, Govindjee G, Arnold W. Energetics of photosynthetic glow peaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:983–987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ. Snapshots of the Govindjee lab from the late 1960s to the late 1990s, and beyond. Photosynth Res. 2007;94:153–178. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9275-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ. Govindjee at 80: more than 50 years of free energy for photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2013;116:111–144. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ. Govindjee: a lifetime in photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2019;139:9–14. doi: 10.1007/s11120-018-0592-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ, Govindjee G. Electron transfer through the quinone acceptor complex of photosystem II after one or two actinic flashes in bicarbonate-depleted spinach thylakoid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;935:248–257. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(88)90221-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ, Govindjee G. Electron transfer through the quinone acceptor complex of photosystem II in bicarbonate-depleted spinach thylakoid membranes as a function of actinic flash number and frequency. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;935:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(88)90220-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Rye JJ (1987) Bicarbonate reversible anionic inhibition of the quinone reductase in photosystem II. Ph.D Dissertation, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Ebrey T. Brighter than the sun: Rajni Govindjee at 80 and her fifty years in photobiology. Photosynth Res. 2015;124:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11120-015-0106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R, Lewis CM. The dependence of the quantum yield of Chlorellaphotosynthesis on wavelength of light. Am J Bot. 1943;30(3):165–178. doi: 10.2307/2437236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R, Chalmers RV, Cederstrand CN. Some factors influencing the long wave limit of photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1957;43:133–143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.43.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee E. 63 Years since Kautsky-chlorophyll-a fluorescence. Aust J Plant Physiol. 2014;22(2):131–160. doi: 10.1071/PP9950131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G. On the evolution of the concept of two light reactions and two photosystems for oxygenic photosynthesis: a personal perspective. Photosynthetica. 2023;61:37–47. doi: 10.32615/ps.2023.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Coleman W. How plants make oxygen. Sci Am. 1990;262:50–58. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0290-50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Govindjee R. Primary events in photosynthesis. Sci Am. 1974;231:68–82. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1274-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Rabinowitch E. a) Two forms of chlorophyll a in vivo with distinct photochemical function. Science. 1960;132:355–356. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3423.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Rabinowitch E. b) Action spectrum of the second Emerson effect. Biophys J. 1960;43:73–89. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(60)86877-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Rabinowitch E. c) Two forms of chlorophyll a in vivo with distinct photochemical function. Science. 1960;132:355–356. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3423.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee R, Govindjee G, Hoch G. The Emerson enhancement effect in TPN-photoreduction by spinach chloroplasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1962;9:222–225. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(62)90062-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, OvH O, Hoch G. A mass spectroscopic study of the Emerson enhancement effect. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;75:281–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)90611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee R, Govindjee G, Hoch G. Emerson Enhancement Effect in chloroplast reactions. Plant Physiol. 1964;39:10–14. doi: 10.1104/pp.39.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Döring G, Govindjee R. The active chlorophyll a11 in suspensions of lyophilized and tris-washed chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;205:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(70)90260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Pulles MPJ, Govindjee R, van Gorkom HJ, Duysens LNM. Inhibition of the reoxidation of the secondary electron acceptor of Photosystem II by bicarbonate depletion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;449:602–605. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Wydrzynski T, Marks SB. Manganese and chloride: their roles in photosynthesis. In: Metzner H, editor. Symposium on photosynthetic oxygen evolution. London: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 321–344. [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Koike H, Inoue Y. Thermoluminiscence and oxygen evolution from a thermophilic blue-green alga obtained after single-turnover light flashes. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;42:579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1985.tb01613.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Xu C, Schansker G, van Rensen JJS. Chloroacetates as inhibitors of photosystem II: effects on electron acceptor side. J Photochem Photobiol b: Biol. 1997;37:107–117. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(96)07347-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Shevela D, Björn LO. Evolution of the Z-scheme of photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2017;133:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s11120-016-0333-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Papageorgiou GC, Govindjee R. Eugene I. Rabinowitch: A prophet of photosynthesis and of peace in the world. Photosynth Res. 2019;141:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s11120-019-00641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindjee G, Beatty JT, Gest H, Allen JF (2005) Discoveries in Photosynthesis, Adv Photosyn Respir, Springer, Dordrecht, 20

- Govindjee G (1960) Effect of combining two wavelengths of light on the photosynthesis of algae, Ph.D. Thesis in Biophysics, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign.

- Govindjee R (1961) The action spectrum of the hill reaction in whole algal cells and chloroplast suspensions (red drop, second emerson effect and inhibition by extreme red light), Ph.D. Thesis in Biophysics, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign.

- Hill JF, Govindjee G. The controversy over the minimum quantum requirement for oxygen evolution. Photosynth Res. 2014;122:97–112. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holub O, Seufferheld MJ, Gohlke C, Govindjee G, Heiss GJ, Clegg RM. Flourescence lifetime imaging microscopy of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: non-photochemical quenching mutants and the effect of photosynthetic inhibitors on the slow chlorophyll fluorescence transient. J Microsc. 2007;226(2):90–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou HJM, Allakhverdiev SI. Photosynthesis: From Plants to Nanomaterials. Elsevier; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hou HJ, Allakhverdiev SI, Najafpour MM, Govindjee, Current challenges in photosynthesis: from natural to artificial. Front Plant Sci. 2014;28(5):232. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou HJM, Najafpour MM, Allakhverdiev SI, Govindjee G. Editorial: Current challenges in photosynthesis: from natural to artificial, volume II. Front Plant Sci. 2023;5(13):1113693. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1113693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jajoo A, Guruprasad KN, Bharti S, Mohanty P. International conference “Photosynthesis in the Global Perspective” held in honor of Govindjee, November 27–29, 2008, Indore, India. Photosynth Res. 2009;100:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jajoo A, Subramanyam R, Garab G, Allakhverdiev SI. Honoring two stalwarts of photosynthesis research: Eva-Mari Aro and Govindjee. Photosynth Res. 2023;27:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11120-022-00988-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaji HM, Goltsev V, Bosa K, Allakhverdiev SI, Strasser RJ, Govindjee G. Experimental in-vivo measurements of light emission in plants: a perspective dedicated to David Walker. Photosynth Res. 2012;114:69–96. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur D, Gisriel C, Burnap R, Fromme P, Govindjee G. Gordon research conference 2019: From the biophysics of natural and artificial photosynthesis to bioenergy conversion. Curr Plant Biol. 2020;22:100129. doi: 10.1016/j.cpb.2019.100129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Govindjee G, Wydrzynski T. Site of bicarbonate effect in Hill reaction: evidence from the use of artificial electron acceptors and donors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;462:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(77)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Wagner R, Junge W, Govindjee G. Effects of CO2-depletion on proton uptake and release in thylakoid membranes. FEBS Lett. 1980;121:222–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80347-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R (1980) Role of bicarbonate and of manganese in photosystem II reactions of photosynthesis. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Krey A, Govindjee G. Fluorescence changes in Porphyridium exposed to green light of different intensity: a new emission band at 693 nm: its significance to photosynthesis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1964;52:1568–1572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.6.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Nedbal L, Govindjee G. Photosynthesis in silico: understanding complexity from molecules to ecosystems, advances in photosynthesis and respiration. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laloraya MM, Govindjee G. Effect of tobacco leaf-curl and tobacco mosaic virus on the amino acid content of Nicotiana sp. Nature (london) 1955;175:907–908. doi: 10.1038/175907a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JL, de Witt TW, Smith EC, Daniels F. A photocalorimeter: the quantum efficiency of photosynthesis in algae. J Am Chem Soc. 1939;61:3529–3533. doi: 10.1021/ja01267a089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WM, Stauffer JF, Duggar BM, Daniels F. Quantum efficiency of photosynthesis in Chlorella. J Am Chem Soc. 1938;60:266–274. doi: 10.1021/ja01269a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mar T, Govindjee G. Thermoluminescence in spinach chloroplasts and in Chlorella. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;226:200–203. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara S, Chen YC, Caliandro R, Govindjee G, Robert Clegg M. Photosystem II fluorescence lifetime imaging in avocado leaves: contributions of the lutein-epoxide and violaxanthin cycles to fluorescence quenching. J Photochem Photobiol b: Biol. 2011;104:271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafpour MM, Govindjee G. Oxygen evolving complex in photosystem II: better than excellent. Dalton Trans. 2011;40(36):9076–9084. doi: 10.1039/C1DT10746A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafpour MM, Tabrizi MA, Haghighi B, Govindjee G. A manganese oxide with phenol groups as a promising structural model for water oxidizing complex in Photosystem II: a ‘golden fish’. Dalton Trans. 2012;41(14):3906–3910. doi: 10.1039/C2DT11672C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafpour MM, Moghaddam AN, Allakhverdiev SI. Biological water oxidation: lessons from nature. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2012;8:1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanba O, Satoh N. Isolation of a photosystem II reaction center consisting of D-1 and D-2 polypeptides and cytochrome b-555. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:109–112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickelsen K, Govindjee G (2011) The Maximum quantum yield controversy: otto warburg and the midwest gang. Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Bern, Switzerland; Institute für Philosophie.

- Nonomura A, Kumar A. Celebrating the 2022 lifetime achievement award of the international society of photosynthesis research to Govindjee, who hails from Allahabad. LS-an Int J Life Sci. 2022;11(3):153–155. doi: 10.5958/2319-1198.2022.00014.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR, Chinnusamy V, Pareek A. Photosynthesis: diving deep into the process in the era of climate change. Plant Physiol Rep. 2022;27:539–542. doi: 10.1007/s40502-022-00703-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou GC, Govindjee G. Chlorophyll a fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis, advances in photosynthesis and respiration. Dordrecht: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch E, Govindjee G. The role of chlorophyll in photosynthesis. Sci Am. 1965;213:74–83. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0765-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch E, Govindjee G, Thomas JB. Inhibition of photosynthesis in some algae by extreme-red light. Science. 1960;132(3424):422–422. doi: 10.1126/science.132.3424.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitch E, Govindjee G (1969) Photosynthesis. John Wiley and Sons Inc. New York, p 273

- Schansker G, Srivastava A, Govindjee G, Strasser RJ. Characterization of the 820-nm transmission signal paralleling the chlorophyll a fluorescence rise (OJIP) in pea leaves. Funct Plant Biol. 2003;30:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert M, Mattoo A, Kumar A. A special toast to Govindjee Govindjee on celebrating his 90th birthday on 24 October 2022. Int J Life Sci. 2022;11(3):156–175. doi: 10.5958/2319-1198.2022.00015.X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shabnam N, Sharmila P, Sharma A, Strasser RJ, Govindjee G, Pardha-Saradhi P. Mitochondrial electron transport protects floating leaves of long leaf pondweed (Potamogeton nodosus Poir) against photoinhibition: comparison with submerged leaves. Photosynth Res. 2015;125:305–319. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-0051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevela D, Eaton-Rye JJ, Shen JR, Govindjee G. Photosystem II and unique role of bicarbonate: a historical perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:1134–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevela D, Bjorn LO, Govindjee G. Photosynthesis: solar energy for life. World Scientific Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Strasser RJ, Govindjee G. Polyphasic rise of chlorophyll a fluorescence in herbicide-resistant D1 mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res. 1995;43:131–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00042970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemler A, Govindjee G. Bicarbonate ion as a critical factor in photosnthetic oxygen evolution. Plant Physiol. 1973;52:119–123. doi: 10.1104/pp.52.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemler AJ (1965) Effect of combining two wavelengths of light on the photosynthesis of algae. Ph.D. Thesis in Biophysics, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign.

- Stirbet A, Govindjee G. On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and Photosystem II: Basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J Photochem Photobiol b: Biol. 2011;104:236–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet A, Govindjee G. Chlorophyll a fluorescence induction: a personal perspective of the thermal phase, the J-I-P rise. Photosynth Res. 2012;113:15–61. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet A, Govindjee G. The slow phase of chlorophyll a fluorescence induction in silico: origin of the S-M fluorescence rise. Photosynth Res. 2016;130:193–213. doi: 10.1007/s11120-016-0243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet A, Yu RG, Rubin AB, Govindjee G. Modeling chlorophyll a fluorescence transient: relation to photosynthesis. Biochem (moscow) 2014;79:291–323. doi: 10.1134/S0006297914040014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet A, Lazár D, Papageorgiou GC, Govindjee G (2019) Chlorophyll a fluorescence in cyanobacteria: relation to photosynthesis. In: Mishra AN, Tiwari DN, Rai AN (eds) Cyanobacteria: from basic science to applications, Elsevier Publishers Academic Press, pp 79–130. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814667-5.00005-2

- Strasser BJ, Strasser RJ (1995) Measuring fast fluorescence transients to address environmental questions: the JIP test. In: Mathis P (ed) Photosynthesis: from light to Biosphere. Vol. 5. Dordrecht, Kluwer, pp 977–980. 10.1007/978-94-009-0173-5_1142

- Tatake VG, Desai TS, Govindjee G, Sane PV. Energy storage states of photosynthetic membranes: activation energies and lifetimes of electrons in the trap states by thermoluminescence method. Photochem Photobiol. 1981;33:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1981.tb05331.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vass I, Govindjee G. Thermoluminescence from the photosynthetic apparatus. Photosynth Res. 1996;48:117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00041002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O, Krippahl G (1960) Notwendigkeit der Kohlensäure für die Chinon und Ferricyanidreaktionen in grünen Grana. Z. Naturforsch 15b:367–369. 10.1515/znb-1960-0605

- Warburg O, Negelein E. Über den Einfluss der Wellenlänge auf den Energieumsatz bei der Kohlensäureassimilation. Zeit Physik Chem. 1923;106:191–218. doi: 10.1515/zpch-1923-10614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasielewski MR, Johnson DG, Govindjee G, Preston C, Seibert M. Determination of the primary charge separation rate in photosystem II reaction centers at 15 K. Photosynth Res. 1989;22:89–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00114769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasielewski MR, Johnson DG, Seibert M, Govindjee G. Determination of the primary charge separation rate in isolated photosystem II reaction centers with 500 femtosecond time resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:524–548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wydrzynski T, Govindjee G. A new site of bicarbonate effect in photosystem II of photosynthesis: evidence from chlorophyll fluorescence transients in spinach chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;387:403–408. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(75)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wydrzynski TJ, Marks SB, Schmidt PG, Govindjee G, Gutowsky HS. Nuclear magnetic relaxation by the manganese in aqueous suspensions of chloroplasts. Biochemistry. 1978;17:2155–2162. doi: 10.1021/bi00604a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Subramanian S, Govindjee G. A knowledge-based three dimensional model of the photosystem II reaction center of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res. 1998;56:229–254. doi: 10.1023/A:1006061918025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J (1996) Experimental and theoretical studies of the photosystem II reaction center: implications for bicarbonate binding and function. PhD Dissertation, The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Yates D. Govindjee’s photosynthesis museum. Int J Life Sci. 2022;11(2):93–97. doi: 10.5958/2319-1198.2022.00008.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yates D (2019) Govindjee’s Photosynthesis Museum. Illinois News Bureau, University of Illinois. https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/801235

- Yusuf MA, Kumar D, Rajwanshi R, Strasser RJ, Tsimilli-Michael M, Govindjee G, Sarin NB. Overexpression of gamma-tocopherol methyl transferase gene in transgenic Brassica juncea plants alleviates abiotic stress: physiological and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1428–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]