Abstract

PURPOSE

To assess the quantification accuracy of pulmonary nodules using virtual monoenergetic images (VMIs) derived from spectral-detector computed tomography (CT) under an ultra-low-dose scan protocol.

METHODS

A chest phantom consisting of 12 pulmonary nodules was scanned using spectral-detector CT at 100 kVp/10 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, 120 kVp/10 mAs, and 120 kVp/30 mAs. Each scanning protocol was repeated three times. Each CT scan was reconstructed utilizing filtered back projection, hybrid iterative reconstruction, iterative model reconstruction (IMR), and VMIs of 40–100 keV. The signal-to-noise ratio and air noise of images, absolute differences, and absolute percentage measurement errors (APEs) of the diameter, density, and volume of the four scan protocols and ten reconstruction images were compared.

RESULTS

With each fixed reconstruction image, the four scanning protocols exhibited no significant differences in APEs for diameter and density (all P > 0.05). Of the four scan protocols and ten reconstruction images, APEs for nodule volume had no significant differences (all P > 0.05). At 100 kVp/10 mAs, APEs for density using IMR were the lowest (APE-mean: 6.69), but no significant difference was detected between VMIs at 50 keV (APE-mean: 11.69) and IMR (P = 0.666). In the subgroup analysis, at 100 kVp/10 mAs, there were no significant differences between VMIs at 50 keV and IMR in diameter and density (all P > 0.05). The radiation dose at 100 kVp/10 mAs was reduced by 77.8% compared with that at 120 kVp/30 mAs.

CONCLUSION

Compared with IMR, reconstruction at 100 kVp/10 mAs and 50 keV provides a more accurate quantification of pulmonary nodules, and the radiation dose is reduced by 77.8% compared with that at 120 kVp/30 mAs, demonstrating great potential for ultra-low-dose spectral-detector CT.

Keywords: Spectral computed tomography, chest phantom, pulmonary nodule, low-dose computed tomography, reconstruction algorithm

Main points

• A 100 kVp/10 mAs scan protocol based on spectral-detector computed tomography (CT) can accurately quantify the diameter and density of pulmonary nodules.

• Iterative model reconstruction (IMR) demonstrated improved image quality under the 100 kVp/10 mAs scan protocol, and virtual monoenergetic images at 50 keV were similar to those obtained with IMR.

• The ultra-low-dose scan protocol (100 kVp/10 mAs) based on spectral-detector CT reduced the radiation dose by 77.8% compared with that at 120 kVp/30 mAs.

With increasing public attention on pulmonary nodules and lung cancer, low-dose chest computed tomography (CT) has become an effective modality for the diagnostic screening and prognostic evaluation of lung cancer.1,2 However, radiation dose remains a key public concern. Image quality in low-dose CT with frequently-used reconstruction algorithms has been widely discussed.3,4 With advances in reconstruction algorithms, iterative reconstruction (IR) and deep learning image reconstruction technologies have improved image quality.4,5,6,7 In particular, IR decreases image noise and ensures image quality by optimizing and correcting the raw data. The iDose4 is a hybrid IR algorithm containing filtered back projection (FBP) and IR components, which could obtain low-noise and high-resolution images with a more complete and comprehensive system model.8 Additionally, iterative model reconstruction (IMR), another IR algorithm based on the complete model but without FBP components, has been demonstrated to yield sufficiently high-quality images of the chest, abdomen, spine, and other organs.9,10,11

Dual-layer spectral CT (DLCT) with an energy level of 100 kVp is capable of energy analysis. Under a scanning protocol of 100 kVp/10 mAs, an effective radiation dose is reduced to 0.2954 mSv, equivalent to 5–6 times that of chest radiography exposures. The virtual monoenergy of spectral CT ranges from 40 to 200 keV; generally, the lower the keV value is, the higher the contrast and noise. Moreover, DLCT can reconstruct 161 virtual monoenergetic images (VMIs) at different keV levels (40–200 keV), but the accuracy of the quantitative evaluation of new-generation spectral CT is rarely reported. Additionally, studies have revealed that the radiation dose level, virtual monoenergetic level, and kVp tube voltage settings significantly affect the quantitative accuracy and image quality of spectral CT.12,13 Therefore, this study aimed to assess the impact of different scanning protocols and reconstruction techniques on the quantitative measurement of pulmonary nodules by performing low-dose CT and ultra-low-dose CT scans using different image reconstruction techniques on a chest phantom.14,15

Methods

Anthropomorphic chest phantom and synthetic lung nodules

A commercially available multipurpose anthropomorphic thoracic phantom (Lungman; Kyoto Kagaku, Kyoto, Japan; http://www.kyotokagaku.com) was utilized to simulate the human thorax. This phantom consisted of a life-size anatomical model of a human male thorax with substitute materials for soft tissues and synthetic bones. Three-dimensional synthetic pulmonary vessels and bronchi were inserted into the phantom lung.

In total, 12 spherical synthetic pulmonary nodules (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) were utilized. The attenuation levels of the ground-glass nodules (GGNs) were −800 and −630 Hounsfield unit (HU) and that of the solid nodules (SNs) was 100 HU. These nodules were randomly placed in the phantom by a technologist with 15 years of experience, and observers were blinded to the placement of the nodules. This retrospective study was approved by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University institutional review board (CZ-20220512-06), and the need for informed patient consent was waived.

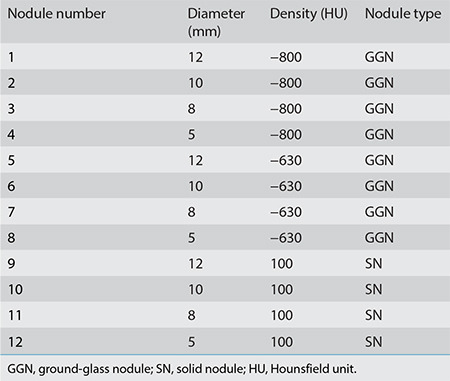

Supplementary Table 1. Characteristics of 12 spherical synthetic lung nodules.

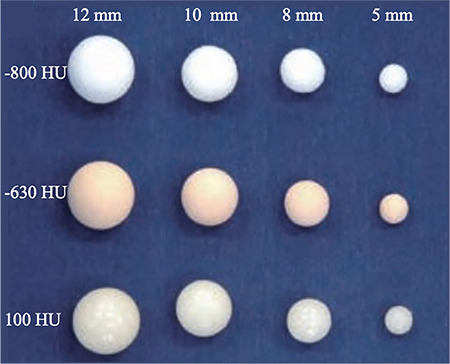

Supplementary Figure 1.

Artificial pulmonary nodules with four distinct diameters (5, 8, 10, and 12 mm) and three different densities (−800, −630, and 100 HU). HU, Hounsfield unit.

Computed tomography image acquisition

All CT images were obtained using second-generation DLCT equipment (Philips spectral CT 7500, Best, The Netherlands). These image acquisitions were performed using four different radiation dose levels (100 kVp/10 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, 120 kVp/10 mAs, and 120 kVp/30 mAs). The effective dose (ED) was determined as dose length product (DLP) × k (0.014), where DLP is the actual value. The scan parameters were as follows: collimation, 128 × 0.625 mm; beam width, 80 mm; slice thickness, 1 mm; pitch, 0.99; rotation time, 0.5 seconds. Each acquisition was repeated three times.

Image reconstruction

The dataset for each scanning dose contained conventional images and monoenergetic images from the original spectral base images data (SBI data) of Compton scattering and photoelectric effects. Conventional images were reconstructed using FBP, iDose4 (level 5), and IMR (body routine level 2). In addition, VMIs were generated from SBI data obtained at 40–100 keV (iDose4, spectral level 5) with a 10–keV interval (40/50/60/70/80/90/100 keV). In total, 40 reconstruction imaging datasets were obtained and analyzed.

Quantitative evaluation of nodules and image quality

The diameters and densities of the 12 nodules were manually measured independently by two radiologists with three years of experience in thoracic imaging. The longest nodule diameter on the maximum axial plane was measured. Nodule density was also measured on the maximum axial plane with a region of interest (ROI) large enough to cover the nodule, sparing the nodule margin to eliminate the partial volumetric effect. The images were transmitted to automatic volume measurement software (Infervision Medical Technology, Beijing, China) to automatically determine the volume of the nodules. Image quality was evaluated using the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and air noise (AN). The SNR was defined as the ratio of CT attenuation for the lung tissue to the standard deviation (SD) of AN. The ROIs were placed on the right lower lobe for the CT attenuation of the lung and in front of the middle of the sternum for the AN.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Python 3. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to analyze overall consistency, and a Bland–Altman analysis was utilized for subgroup consistency. The Kruskal–Wallis test of overall significance was used to assess the significance of image quality. In case of a significant difference in the whole population, a Nemenyi post-hoc test was further applied. The absolute percentage measurement error (APE) was determined for the comparison of measured and reference data. The dimension and density of the mold provided by the phantom’s manufacturer were used as reference data. The standard for volume was determined based on nodule dimension. The absolute difference and APE were presented as mean ± SD and compared among different scan protocols and reconstruction images. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Intra-observer and inter-observer consistencies of nodule parameters and image qualities

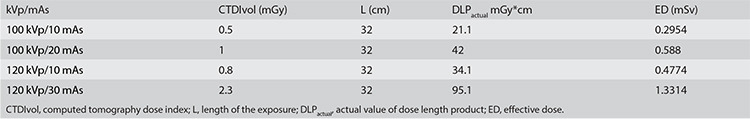

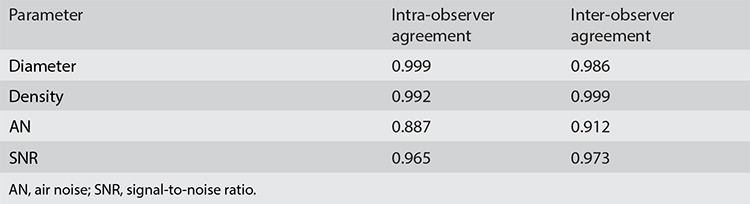

The ED values for the four scanning protocols were 0.2954, 0.588, 0.4774, and 1.3314 mSv (Supplementary Table 2). The intra-observer agreement levels for nodule diameter and density and the AN and SNR of images between observers were excellent, with ICCs of 0.999, 0.992, 0.887, and 0.965, respectively. The inter-observer agreement levels for nodule diameter and density and the AN and SNR of images between observers were excellent, with ICCs of 0.986, 0.999, 0.912, and 0.973, respectively (Table 1). The measurement results from one scanning are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Supplementary Table 2. Estimated radiation dose for various computed tomography protocols.

Table 1. Intra-observer agreement and inter-observer agreement of nodule parameters and image quality.

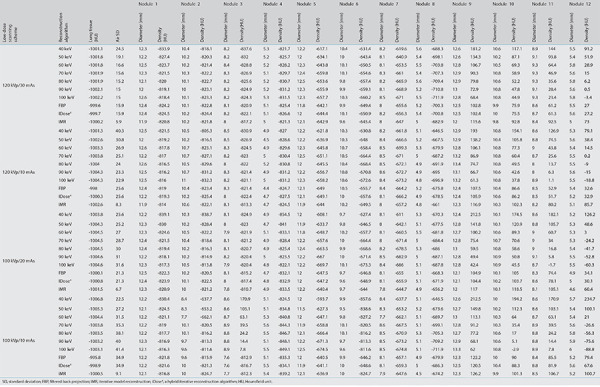

Supplementary Table 3. Nodule parameters and image quality for one scanning protocol.

Image quality comparison

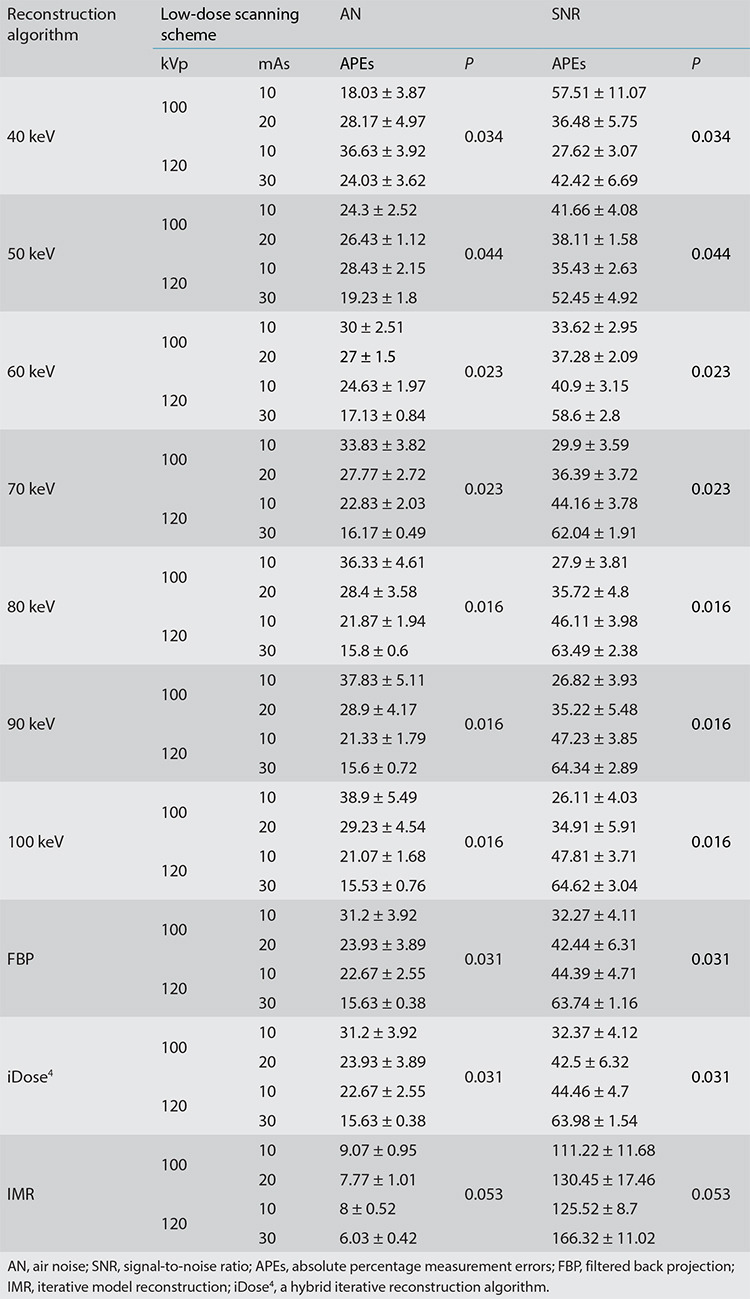

The image quality obtained using the four different scanning protocols (100 kVp/10 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, 120 kVp/10 mAs, and 120 kVp/30 mAs) revealed statistical differences (P < 0.05) among nine of the image reconstruction types (FBP, iDose4, and seven VMIs), with the exception of IMR (P = 0.053) (Table 2). The post-test analysis revealed no significant difference in image quality at 50 keV between 100 kVp/10 mAs and 120 kVp/30 mAs (P > 0.05). At doses of 100 kVp/10 mAs, 120 kVp/10 mAs, and 120 kVp/30 mAs, AN and SNR levels among the 10 image types demonstrated statistical differences (all P < 0.05).

Table 2. Air noise and signal-to-noise ratio using 10 reconstruction images.

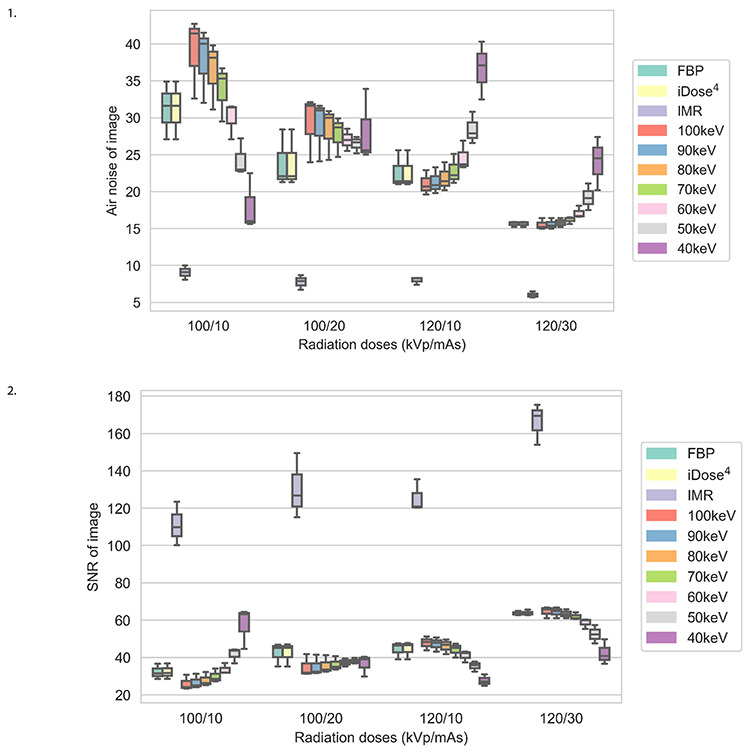

Under a scanning protocol of 120 kVp/30 mAs, IMR exhibited the best image quality (AN-mean: 6.03 and SNR-mean: 166.32). In addition, at 100 kVp/10 mAs, the image quality of IMR (AN-mean: 9.07 and SNR-mean: 111.22) was better than that of FBP (AN-mean: 31.20 and SNR-mean: 32.27) and iDose4 (AN-mean: 31.20 and SNR-mean: 32.37), and image quality at 100 keV was the poorest (AN-mean: 38.90 and SNR-mean: 26.11) (Figures 1, 2).

Figures 1, 2.

Box plots of air noise and signal-to-noise ratios for 10 reconstruction images using 4 low-dose scanning protocols. SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; FBP, filtered back projection; iDose4, a hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm; IMR, iterative model reconstruction.

Effects of the four scanning protocols and 10 image reconstruction approaches on the diameter and density of pulmonary nodules

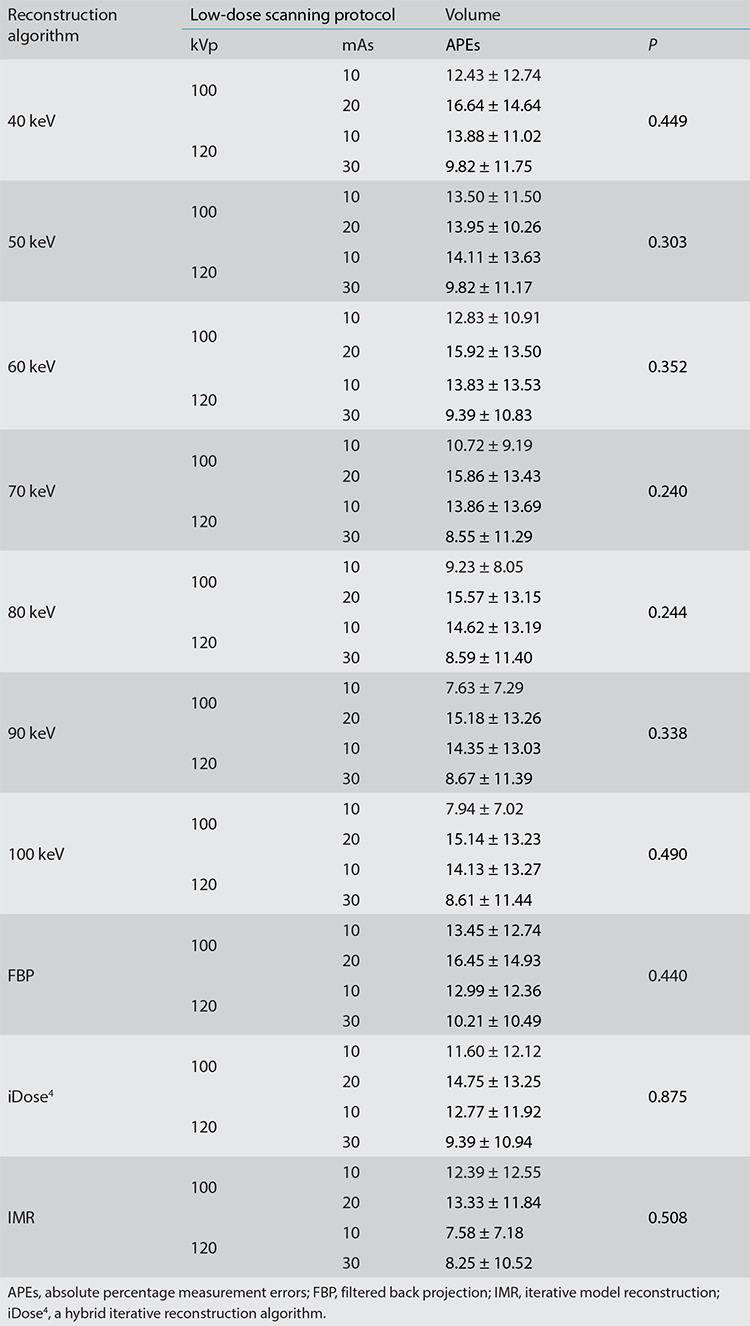

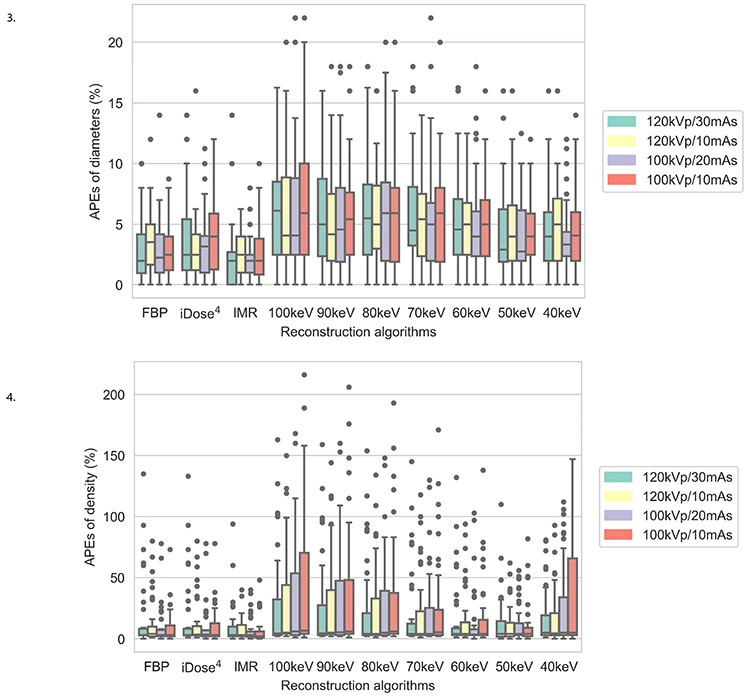

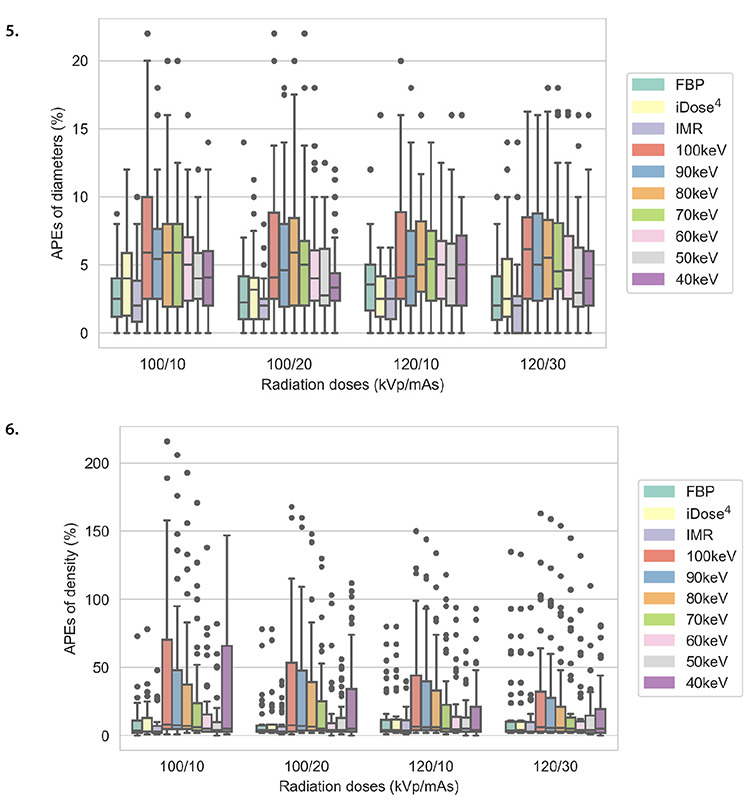

In each scanning group, the nodule volumes revealed no significant differences among the 10 reconstructed images (P > 0.05). The four scanning dose groups exhibited no significant statistical differences in the volume, diameter, and density of pulmonary nodules for each reconstruction image (all P > 0.05) (Tables 3, 4, Figures 3, 4). Nodules with a size of 5 mm were not detected by the automatic detection software. In three scanning groups (100 kVp/10 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, and 120 kVp/10 mAs), the pulmonary nodule densities obtained using the 10 reconstruction images were statistically different (all P < 0.05); however, at 120 kVp/30 mAs, no statistically significant difference was identified (P > 0.05). At 100 kVp/10 mAs, APEs for the density in IMR were the lowest (APE-mean : 6.69), and no significant difference was detected between 50 keV (APE-mean: 11.69) and IMR (P = 0.666). In each scanning group, nodule diameters were statistically different for the 10 reconstruction images (P < 0.001). At 120 kVp/30 mAs, APEs for the nodule diameter in IMR were the lowest (APE-mean: 2.29) and no significant difference was identified between 50 keV (APE-mean: 4.41), and IMR (P = 0.726) (Figures 5, 6).

Table 3. Mean absolute percentage measurement errors of the volume of pulmonary nodules based on 4 low-dose scanning schemes using 10 reconstruction images.

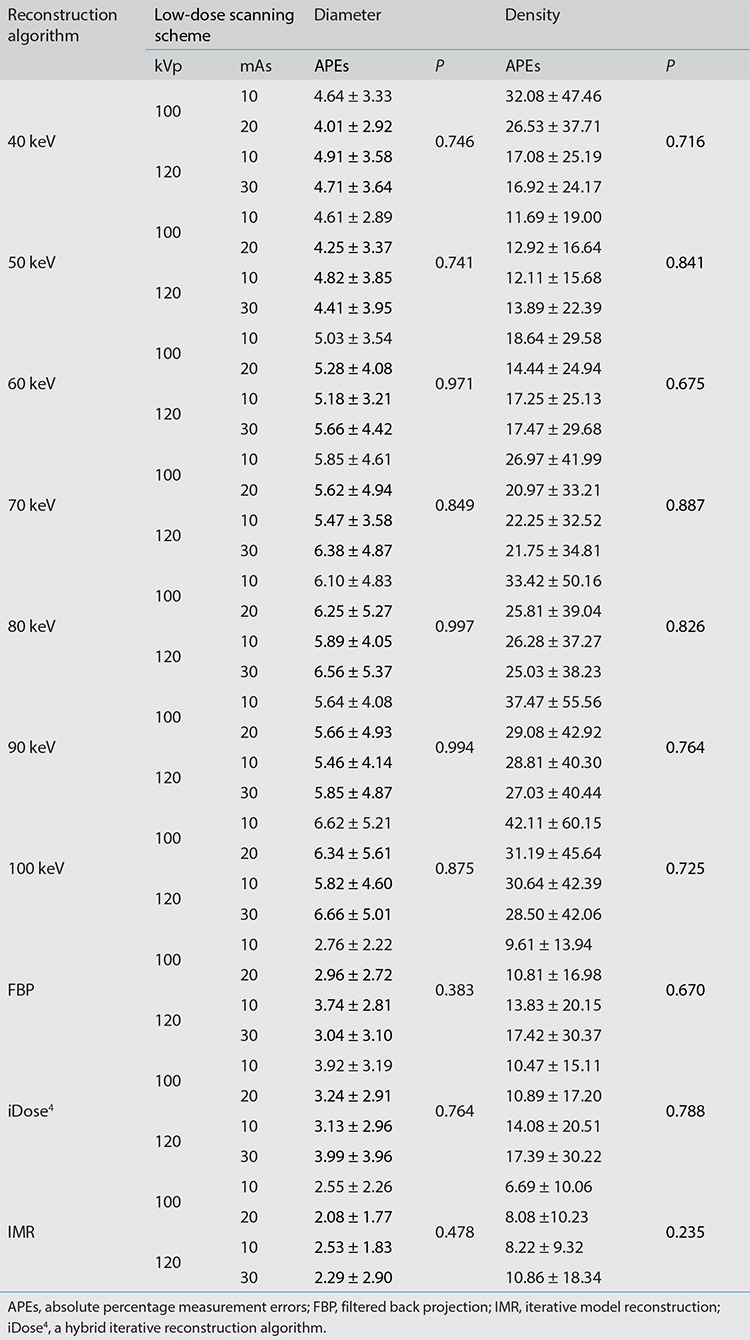

Table 4. Mean absolute percentage measurement errors of the diameter and density of pulmonary nodules based on 4 low-dose scanning protocols using 10 reconstruction images.

Figures 3, 4.

Box plots of the mean absolute percentage measurement errors of the diameter and density of pulmonary nodules for 4 low-dose scanning protocols using 10 reconstruction images. APEs, absolute percentage measurement errors; FBP, filtered back projection; iDose4, a hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm; IMR, iterative model reconstruction.

Figures 5, 6.

Box plots of mean absolute percentage measurement errors of the diameter and density of pulmonary nodules for 10 reconstruction images and four low-dose scanning protocols. APEs, absolute percentage measurement errors; FBP, filtered back projection; iDose4, a hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm; IMR, iterative model reconstruction.

Comparison of quantitative parameters between ground-glass nodules and solid nodules for fixed reconstruction images

For fixed reconstruction images, no significant differences in diameter and density measurements were detected for GGNs at −800 and −630 HU and SNs at 100 HU in the reconstruction images obtained using the four scanning protocols (all P > 0.05). However, with the exception of the density of SNs (100 HU), a difference was identified between the 100 kVp/10 mAs and 120 kVp/30 mAs scanning protocols for the 40-keV reconstruction image (P = 0.036).

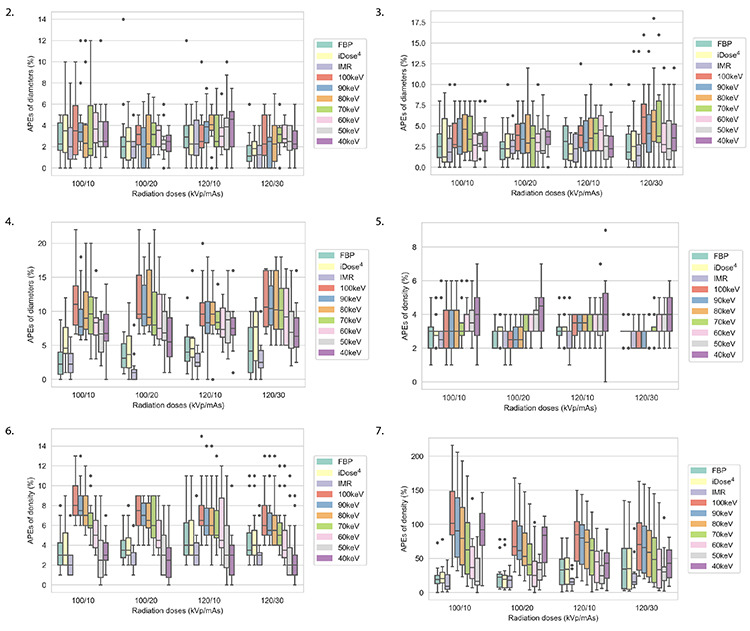

Comparison of quantitative parameters between ground-glass nodules and solid nodules for fixed scanning protocols

For each scanning protocol, the diameters of the SNs at 100 HU measured using the 10 reconstruction images were statistically different (P < 0.001), but no significant statistical difference was detected in the diameter of GGNs (CT value: −800 and −630 HU) (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the post-test analysis revealed no significant statistical differences at 100 kVp/10 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, and 120 kVp/30 mAs between 50 keV and IMR in the diameters of SNs (CT value: 100 HU) (all P > 0.05). However, at 120 kVp/10 mAs, a statistically significant difference was identified between 50 keV and IMR in the diameters of SNs (P = 0.029) (Supplementary Figures 2-4).

Supplementary Figures 2-7.

Diameter and density mean absolute percentage measurement error box plots of nodules obtained at densities of −800, −630, and 100 HU for 10 reconstruction images under 4 scanning protocols. HU, Hounsfield unit; APEs, absolute percentage measurement errors; FBP, filtered back projection; iDose4, a hybrid iterative reconstruction algorithm; IMR, iterative model reconstruction.

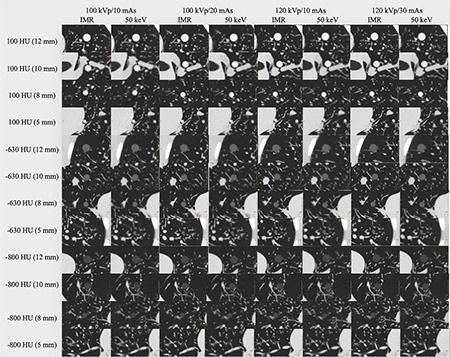

For GGNs examined at −630 HU and SNs assessed at 100 HU, all four scanning protocols exhibited statistical differences in density measurements in the 10 reconstruction images (P < 0.05). For GGNs examined at −800 HU, scanning protocols at 100 kVp/20 mAs and 120 kVp/30 mAs displayed statistical differences in density measurements in the 10 reconstruction images (P < 0.05). For GGNs assessed at −800 HU, scanning protocols at 100 kVp/10 mAs and 120 kVp/10 mAs had no statistical differences in density measurements in the 10 reconstruction images (P > 0.05). For SNs assessed at 100 HU and GGNs examined at −630 and −800 HU, no significant differences in density were detected between 50 keV and IMR at 100 kVp/10 mAs (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Figures 5-7). The CT images for the pulmonary nodules with different diameters and densities using IMR and the 50-keV reconstruction images under the four scanning protocols are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Computed tomography images of pulmonary nodules with different diameters and densities for iterative model reconstruction and 50-keV reconstruction images under four scanning protocols. IMR, iterative model reconstruction; HU, Hounsfield unit.

Discussion

This study elucidated the differences in the accurate quantification of pulmonary nodules using different reconstruction protocols under ultra-low-dose scanning conditions based on spectral-detector CT. Furthermore, the effects of 10 image reconstruction approaches on the diameter and density of lung nodules in a phantom were investigated. Scanning at 100 kVp/10 mAs and 50 keV was applied to GGNs and SNs without affecting the quantification of nodule diameter and density. The image quality obtained using the IMR algorithm was superior; moreover, VMIs at 50 keV exhibited similar performance in the measurement of pulmonary nodules. This protocol reduced the effective radiation dose (ED: 0.2954 mSv) by 77.8% compared with that at 120 kVp/30 mAs (ED: 1.3314 mSv).

The lung is filled with air and receives a lower dose of radiation compared with the other parts of the body. The radiation dose for routine chest radiography in two planes is approximately 0.1 mSv; the radiation dose for conventional chest CT scanning is 5–7 mSv versus only 1–2 mSv for low-dose CT scanning.16,17,18 Based on the principle that a dose as low as reasonably achievable should be used, low-dose CT scanning is preferred without affecting the diagnosis.19,20 Additionally, studies have demonstrated that distinct radiation doses have no significant effects on the measurement of pulmonary nodules.21 Under different kVp/mAs scanning conditions, the higher the kVp/mAs is, the better the image quality, but the radiation dose also increases. However, tube voltage has a well-known exponential association with radiation dose; thus, lowering tube voltage can significantly decrease the radiation dose.22,23 A radiation dose is linearly related to mAs; with decreasing mAs, the radiation dose decreases correspondingly. Four low-dose scanning protocols (120 kVp/30 mAs, 100 kVp/20 mAs, 120 kVp/10 mAs, and 100 kVp/10 mAs) exhibited no significant differences in the diameter and density of GGNs and SNs (P > 0.05). Therefore, the 100 kVp/10 mAs protocol may be recommended (ED: 0.2954 mSv) for the evaluation of pulmonary nodules, which would greatly reduce the radiation dose for ultra-low-dose CT (0.13–0.49 mSv).24

The reconstruction algorithm is critical for CT examination, and image quality varies with different reconstruction algorithms. The traditional FBP has been used in CT image reconstruction for a long time with an obvious disadvantage; its key characteristic is that image noise is related to dose, with image noise increasing significantly when the radiation dose is reduced, affecting the accuracy of diagnosis.25,26 The IR aims to reduce noise and improve image quality through the cost function, and based on the task, the cost function differs. As a result of technological developments, we are able to obtain low-noise and high-resolution CT images through iDose4 and IMR technology.8 This study revealed that under a scanning protocol of 100 kVp/10 mAs, superior image quality can be obtained using IMR (AN-mean: 9.07, SNR-mean: 111.22), and AN and SNR are significantly more effective than FBP and iDose4, which is consistent with a study by Kim et al.27 When they applied five scanning protocols at 120 kVp (100/50/20/10 mAs) and 80 kVp/10 mAs, the volume APE and image noise analysis of partly solid nodules (PSNs) and SNs demonstrated that IMR was significantly more effective than iDose4 and FBP. For GGNs, IMR reduced the diameter measurement error and improved image quality.28 Gavrielides et al.29 determined that IMR improved measurement accuracy for 5-mm GGNs (−800 and −630 HU),30 but its advantage needs to be verified for the measurement of smaller nodules. This study did not measure nodules with a diameter below 5 mm; therefore, the accuracy of IMR for the evaluation of nodules with a diameter below 5 mm also needs to be further elucidated. In the evaluation of nodules larger than 5 mm in diameter, IMR improved image quality in low-dose CT, allowing patients to obtain an accurate diagnosis without increasing the radiation dose. In first-generation DLCT, at the same kVp and mAs, the repeatability of monoenergetic reconstructed images was significantly higher than that of conventional images. The measurement repeatability of VMIs for pulmonary nodules were equivalent to that of conventional images using the IR algorithm at a standard dose, suggesting the use of monoenergetic images might allow lung cancer screening at a lower radiation dose.31 Other data revealed that images at a low single-energy level have lower noise and higher image contrast.32 Regarding spectral CT, low VMIs exhibited better image quality than conventional images from the same system.33 This outcome is consistent with that of the present study. At a VMI energy level of 50 keV, image quality is not optimal, but 50 keV did not affect the diameter and density of lung nodules in the examined chest phantom.

This study has some limitations. First, the phantom involved in this study was a simple simulation of the adult chest, with a scanning length of 33 cm, which does not represent the actual clinical situation, including the influence of factors such as respiratory movement and patient body shape on the quantitative accuracy and image quality of spectral CT. Additionally, studies have indicated that scan length also affects the radiation dose received by patients,34,35 which was not evaluated in the present study. Second, second-generation DLCT was applied, and first-generation should be further validated in patients. Third, during scanning, the phantom was scanned 12 times under four scanning conditions (three times for each scanning condition). The positions of nodules in the phantom were inevitably changed when they entered and left the bed, which might impact the measurements. Fourth, the phantom only contained 12 nodules, and pulmonary nodules in this study were circular; however, irregular nodules were not included in the phantom, and PSNs were not evaluated. Therefore, this study may only be applicable to circular GGNs and SNs.

In conclusion, 100 kVp/10 mAs with 50-keV reconstruction demonstrated more accurate quantification of pulmonary nodules than IMR, and the radiation dose was reduced by 77.8% compared with that at 120 kVp/30 mAs, revealing great potential for ultra-low-dose spectral-detector CT.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ke Chen and Lijun Wang for providing technical support. Permission was provided by them.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 81871321, 82171926, 81930049, and 82202140); the program of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant number 21DZ2202600); National Key R&D Program of China (grant number: 2022YFC2010000, 2022YFC2010002, 2017YFC1308703); the construction of CT standardized database for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (grant number: YXFSC2022JJSJ002); Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan Project of Shanghai (grant number: 19411951300); Shanghai Sailing Program (grant number: 20YF1449000); Clinical Innovation Project of Shanghai Changzheng Hospital (grant number: 2020YLCYJ-Y24).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States-2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1278–1281. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruano-Ravina A, Pérez-Ríos M, Casàn-Clará P, Provencio-Pulla M. Low-dose CT for lung cancer screening. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(3):e131–e132. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmann D, Boas FE. Computed tomography--old ideas and new technology. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(3):510–517. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fält T, Söderberg M, Hörberg L, et al. Simulated dose reduction for abdominal CT with filtered back projection technique: effect on liver lesion detection and characterization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;212(1):84–93. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padole A, Ali Khawaja RD, Kalra MK, Singh S. CT radiation dose and iterative reconstruction techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(4):W384–W392. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, Li H, Li J, et al. Improving the image quality of pediatric chest CT angiography with low radiation dose and contrast volume using deep learning image reconstruction. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021;11(7):3051–3058. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geyer LL, Schoepf UJ, Meinel FG, et al. State of the art: iterative ct reconstruction techniques. Radiology. 2015;276(2):339–357. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015132766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laqmani A, Avanesov M, Butscheidt S, et al. Comparison of image quality and visibility of normal and abnormal findings at submillisievert chest CT using filtered back projection, iterative model reconstruction (IMR) and iDose4™. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(11):1971–1979. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Jiang Y, Han X, Wang M, Gao J. Application of low-tube current with iterative model reconstruction on Philips Brilliance iCT Elite FHD in the accuracy of spinal QCT using a European spine phantom. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8(1):32–38. doi: 10.21037/qims.2018.02.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim C, Lee KY, Shin C, et al. Comparison of filtered back projection, hybrid iterative reconstruction, model-based iterative reconstruction, and virtual monoenergetic reconstruction images at both low- and standard-dose settings in measurement of emphysema volume and airway wall thickness: a ct phantom study. Korean J Radiol. 2018;19(4):809–817. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greffier J, Frandon J, Larbi A, Beregi JP, Pereira F. CT iterative reconstruction algorithms: a task-based image quality assessment. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(1):487–500. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cester D, Eberhard M, Alkadhi H, Euler A. Virtual monoenergetic images from dual-energy CT: systematic assessment of task-based image quality performance. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022;12(1):726–741. doi: 10.21037/qims-21-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabli D, Frandon J, Belaouni A, et al. Optimization of image quality and accuracy of low iodine concentration quantification as function of dose level and reconstruction algorithm for abdominal imaging using dual-source CT: a phantom study. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2022;103(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao R, Sui X, Qin R, et al. Can deep learning improve image quality of low-dose CT: a prospective study in interstitial lung disease. Eur Radiol. 2022;32(12):8140–8151. doi: 10.1007/s00330-022-08870-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du Y, Shi GF, Wang YN, Wang Q, Feng H. Repeatability of small lung nodule measurement in low-dose lung screening: a phantom study. BMC Med Imaging. 2020;20(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12880-020-00510-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye K, Zhu Q, Li M, Lu Y, Yuan H. A feasibility study of pulmonary nodule detection by ultralow-dose CT with adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction-V technique. Eur J Radiol. 2019;119:108652. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messerli M, Kluckert T, Knitel M, et al. Ultralow dose CT for pulmonary nodule detection with chest x-ray equivalent dose - a prospective intra-individual comparative study. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(8):3290–3299. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller AR, Jackson D, Hui C, et al. Lung nodules are reliably detectable on ultra-low-dose CT utilising model-based iterative reconstruction with radiation equivalent to plain radiography. Clin Radiol. 2019;74(5):409.e17–409.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mechlem K, Ehn S, Sellerer T, et al. Joint statistical iterative material image reconstruction for spectral computed tomography using a semi-empirical forward model. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37(1):68–80. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2726687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren L, Rajendran K, McCollough CH, Yu L. Quantitative accuracy and dose efficiency of dual-contrast imaging using dual-energy CT: a phantom study. Med Phys. 2020;47(2):441–456. doi: 10.1002/mp.13912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hein PA, Romano VC, Rogalla P, et al. Linear and volume measurements of pulmonary nodules at different CT dose levels - intrascan and interscan analysis. Rofo. 2009;181(1):24–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalender WA, Buchenau S, Deak P, et al. Technical approaches to the optimisation of CT. Phys Med. 2008;24(2):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hadamitzky M, et al. Radiation dose estimates from cardiac multislice computed tomography in daily practice: impact of different scanning protocols on effective dose estimates. Circulation. 2006;113(10):1305–1310. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carey S, Kandel S, Farrell C, et al. Comparison of conventional chest x ray with a novel projection technique for ultra-low dose CT. Med Phys. 2021;48(6):2809–2815. doi: 10.1002/mp.14142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laqmani A, Kurfürst M, Butscheidt S, et al. CT pulmonary angiography at reduced radiation exposure and contrast material volume using iterative model reconstruction and iDose4 technique in comparison to FBP. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willemink MJ, de Jong PA, Leiner T, et al. Iterative reconstruction techniques for computed tomography Part 1: technical principles. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(6):1623–1631. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SK, Kim C, Lee KY, et al. Accuracy of model-based iterative reconstruction for CT volumetry of part-solid nodules and solid nodules in comparison with filtered back projection and hybrid iterative reconstruction at various dose settings: an anthropomorphic chest phantom study. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20(7):1195–1206. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H, Park CM, Chae HD, Lee SM, Goo JM. Impact of radiation dose and iterative reconstruction on pulmonary nodule measurements at chest CT: a phantom study. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21(6):459–465. doi: 10.5152/dir.2015.14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavrielides MA, Berman BP, Supanich M, et al. Quantitative assessment of nonsolid pulmonary nodule volume with computed tomography in a phantom study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2017;7(6):623–635. doi: 10.21037/qims.2017.12.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maruyama S, Fukushima Y, Miyamae Y, Koizumi K. Usefulness of model-based iterative reconstruction in semi-automatic volumetry for ground-glass nodules at ultra-low-dose CT: a phantom study. Radiol Phys Technol. 2018;11(2):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s12194-018-0442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim J, Lee KH, Kim J, Shin YJ, Lee KW. Improved repeatability of subsolid nodule measurement in low-dose lung screening with monoenergetic images: a phantom study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019;9(2):171–179. doi: 10.21037/qims.2018.10.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellerer T, Noël PB, Patino M, et al. Dual-energy CT: a phantom comparison of different platforms for abdominal imaging. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(7):2745–2755. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doerner J, Hauger M, Hickethier T, et al. Image quality evaluation of dual-layer spectral detector CT of the chest and comparison with conventional CT imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2017;93:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanal KM, Butler PF, Sengupta D, Bhargavan-Chatfield M, Coombs LP, Morin RL. U.S. diagnostic reference levels and achievable doses for 10 adult CT examinations. Radiology. 2017;284(1):120–133. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badawy MK, Galea M, Mong KS, U P. Computed tomography overexposure as a consequence of extended scan length. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2015;59(5):586–589. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]