Abstract

BACKGROUND

Individuals who have certain personality traits may be particularly at risk for developing technological addictions. Binge-watching, which includes watching several episodes of a television series consecutively, is seen as a behavior that is out of control and even addictive. Binge-watching also can isolate the individual socially, or it can be a buffer against the individual’s feeling of loneliness. This study was conducted to examine the mediating role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

570 adults older than 18 years of age who were reached by the convenience sampling method participated in the study. The data were collected with the Type D Personality Scale, UCLA Loneliness Scale, and the Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire.

RESULTS

As a result of the study, binge-watching mediated the relationship between type D personality and loneliness, and fit values of this model were within the acceptable range. It can be said that individuals with type D personality tend to decrease their loneliness by watching more series.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings provide a nuanced explanation about how type D personality is associated with loneliness. The results also shed light on effective prevention and intervention strategies to reduce binge-watching. Therapeutic interventions are important especially for individuals with personality traits that cause a feeling of loneliness.

Keywords: binge-watching, type D personality, loneliness, watching series, mediating role

BACKGROUND

While internet-based television and video platforms have developed rapidly in the last few years, ease of use and content that can easily be used and accessed on demand have made these services a daily routine for millions of television viewers (Flayelle et al., 2020). It is known that new digital technologies promote different watching methods. Viewers are not limited to only one screen in which certain content can be viewed only at fixed time intervals (Feijter et al., 2016). While in the past people put up with the tension of waiting a week until the television programs they liked aired next time, this uncertain waiting is gradually decreasing today. Instead of waiting for the next episode to be aired, many people just sit in front of the television or computer for hours and watch the episodes or all seasons of programs that can easily be accessed (Wheeler, 2015).

In this situation, which is called binge-watching, several episodes of a television series or a television program are watched consecutively at the desired time and place (Walton-Pattison et al., 2018). The definition of binge-watching is not clear for many researchers. Binge-watching is defined as watching 4-5 episodes of a series one after the other by some researchers (Moore, 2015), while it is defined as watching a series for at least 3 hours in one sitting by others (Jenner, 2014). One of the problems in these definitions is that the duration of one episode of a series varies (Olding, 2018). In general, ‘binge’ is considered as a negative behavior (Pierce-Grove, 2017) and it refers to getting out of control and even an addiction as in binge-eating or binge-drinking (Goldstein, 2013). Individuals who participated in the group focus study by Flayelle et al. (2017) also stated that watching series could lead to addiction.

Addiction is defined as a repetitive habit pattern that increases the risk of illness and/or associated personal and social problems (Marlatt et al., 1988). According to Griffiths (1996), the components of addiction are salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict and relapse. Similar symptoms are observed in non-chemical (i.e. behavioral) addictions. It has been suggested that the symptoms of binge-watching behavior meet the diagnostic criteria for addiction (Petersen, 2016). The symptoms of binge-watching are lack of self-control (Manley, 2016), feeling guilt and shame about spending a lot of time in watching series (Pierce-Grove, 2017), being able to give up on other life goals to continue binge-watching (Walton-Pattison et al., 2018), appearance of withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, irritability and depression in attempts to limit watching the shows, and failure to limit the behavior (Kubey & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). For this reason, binge-watching can be considered as an addictive behavior (Petersen, 2016). In terms of behavioral addiction, individuals who “go to the extreme” are considered to be in the high risk group (Trouleau, 2016); therefore, it is stated that binge-watching carries a risk of behavioral addiction (Starosta et al., 2019).

On the basis of the concept of behavioral addiction, mental health problems related to binge-watching may be of great concern (Sun & Chang, 2021). Binge-watching may cause psychological health problems such as loneliness and depression (Ahmed, 2017; Wheeler, 2015) and isolate the individual socially (Vaterlaus et al., 2019). Pierce-Grove (2017) emphasized that binge-watching hinders not only social life but also the responsibilities and other activities of individuals. In addition, binge-watching also causes physical problems (Walton-Pattison et al., 2018), reduced sleep quality (Oberschmidt, 2017) and sleep disorders (Exelmans & Van den Bulck, 2017) due to being immobile for a long time. However, it is also stated that binge-watching does not have completely negative consequences. For example, peers can get together and hold series watching sessions; thus, binge-watching also has a social aspect (Willens, 2013). Watching the series with a partner may have a positive effect on the relationship (Pierce-Grove, 2017). In addition, individuals may show binge-watching behavior to cope with loneliness and depression (Starosta et al., 2019) and therefore their psychological well-being may be higher (Olding, 2018).

This information shows us that the effects of binge-watching cannot be unidirectional. The variables affecting binge-watching and the consequences of binge-watching should be examined more extensively. The present study examined the relationship of binge-watching behavior with loneliness and personality characteristics. Loneliness is a natural, subjective and negative emotional response resulting from negative external emotions triggered by the environment, personality characteristics and other factors such as lack of social interaction (Gierveld & Van Tilburg, 2010). The relationship between binge-watching and loneliness is controversial in the literature. While some studies report that binge-watching is not associated with loneliness (Ahmed, 2017), others emphasize that loneliness is positively associated with loneliness (Sung et al., 2015). It is also known that the individuals who binge-watch have a tendency to have escape motivation and motivation to deal with loneliness (Starosta et al., 2019). Viewers can allocate more time to binge-watching to escape social interaction and reality (Panda & Pandey, 2017). Watching television can be a buffer against the individual’s feeling of loneliness, like listening to music, eating and surfing the internet (Derrick et al., 2009). This is because viewers bond with media characters; they get involved in the “show” and create an indirect bond by building a parasocial relationship like friendship. Although this built parasocial relationship is unilateral in terms of the viewer, the bond gets stronger as the familiarity and friendliness with the characters increases (Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018). In a study by Erickson et al. (2019), it was found that binge-watching increased the power of parasocial relationships. This is because binge-watching is a stand-alone activity that occurs in a socially active context online (Feijter et al., 2016). Eyal and Cohen (2006) found that loneliness was positively associated with parasocial breakup distress. Individuals who watch television with friendship motives experience more parasocial breakup distress (Lather & Moyer-Guse, 2011). If individuals watch television to achieve a specific purpose rather than out of habit, they are likely to think that it may be more difficult to find activities alternative to watching television and therefore these individuals may be experiencing more parasocial breakup distress. If watching the preferred television programs creates a buffer against loneliness, it can be assumed that individuals who watch TV to fight loneliness will experience greater distress after a parasocial breakup. Ward (2014) stated that after finishing a season of a television program, he experienced a depressive feeling such as the inhibition he felt after finishing a good novel. In one study, depression levels of individuals who showed binge-watching behavior were found to be higher than those of other individuals (Ahmed, 2017).

These explanations bring to mind type D (distressed) personality, which is defined as the abundance of negative feelings and the inability to express feelings and behaviors in social interactions. Negative affect and social inhibition are seen in individuals with type D personality (Denollet, 2000). Negative affect refers to the tendency to express negative emotions between time/situations. Individuals with negative affect generally feel more hostile feelings, anxiety and tension in depressive mood and show more physical symptoms (Denollet, 2005). Social inhibition refers to the tendency to inhibit the expression of emotions/behaviors in social interactions to avoid not being approved of by others (Asendorpf, 1993). It is stated that socially introverted individuals feel tense, insecure and more suppressed (Denollet, 2005; Weng et al., 2013). Studies examining the relationship between binge-watching and mental health (Boudali et al., 2017; Jacobs, 2017; Sun & Chang, 2021; Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018; Wheeler, 2015) suggest that type D personality has an effect on binge-watching behavior. These studies have found that depressive mood and social interaction anxiety are associated with binge-watching behavior (Sun & Chang, 2021). Individuals with binge-watching behavior are more likely to be affected by depression (Ahmed, 2017) and they tend to binge-watch to distract themselves from negative emotions (Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018). On the other hand, it is seen that individuals who binge-watch feel more comfortable and happier and have lower depression levels (Boudali et al., 2017; Jacobs, 2017). A similar situation is also seen in individuals with anxiety. Individuals who spend time watching excessive TV tend to isolate socially (Hamer et al., 2010). Individuals with high anxiety may also try to relax and spend time by binge-watching (Wheeler, 2015). As can be understood from these different results, while depression and social anxiety may cause binge-watching, binge-watching may also reduce depression and social anxiety. In the present study, these traits which are associated with negative affect and social inhibition are discussed as a personality trait.

Although the relationship between personality and technological addictions (internet, game, social media, smart phone, etc.) has been described consistently by a large number of empiric studies, the causal path between these two structures is bidirectional; in other words, one can strengthen the other or one can lead to another. Individuals who have certain personality traits may particularly be at risk for developing technological addictions, such as individuals with type D personality having high internet addiction (Holdos, 2017). Research and theory on personality and technological addictions have developed significantly; however, further studies are needed to research the complicated relationship between personality and technological addiction (Hussain & Pontes, 2018). It is thought that type D personality has an effect on binge-watching behavior, as in other addictions. It is known that individuals with type D personality have high levels of loneliness (Denollet et al., 2013; Spek et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2008). This information suggests that type D personality affects loneliness through binge-watching behavior. Studies conducted focus on the causes and consequences of binge-watching. However, no studies were found in which addictions were discussed as factors mediating the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. The present study is the first known study to examine how binge-watching behavior mediates the negative effect of type D personality on loneliness. In the light of all this information, it is thought that explaining the relationship between binge-watching, type D personality and loneliness will contribute to the literature. Identifying the factors associated with new technological addictions seems to be important in order to take required precautions for high-risk individuals. Based on this, the aim of the present study is to examine the mediating role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. The independent variable of the study is type D personality, and the dependent variables are loneliness and binge-watching. The present study sought answer to the question “does binge-watching play a mediating role in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness?” Based on this research question, the following hypotheses were posited:

H1: Negative affectivity is positively correlated with loneliness and binge-watching, and also social inhibition is positively correlated with loneliness and binge-watching.

H2: Binge-watching mediates the relationship between type D personality and loneliness.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study group consisted of 570 adults older than 18 years of age who were reached by the convenience sampling method. The online surveys were hosted on online platforms, and sent via social media and applications such as e-mail and WhatsApp, mainly among individuals older than 18 years of age. Inclusion criteria were being at least 18 years of age, and having watched TV series episodes on a regular basis. The exclusion criterion was having intellectual disability. Participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. Those who were willing to participate in the study completed the online form. Recruitment activities resulted in 589 adults completing and returning the survey. A total of ten questionnaires were excluded from the study due to wrong completion of data, and nine outliers were excluded. Therefore, data obtained from 570 adults were included in the analysis.

Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. 71.9% (n = 410) of the participants were women and 28.1% (n = 160) were men. Almost a third (32.1%, n = 183) of the sample group were students, while 54.9% (n = 313) were active workers, 10.2% (n = 58) were unemployed and 2.8% (n = 16) were retired. 37.4% (n = 213) of the participants were single, 47% (n = 268) were married, and 15.6% (n = 89) were in a relationship. The participants’ ages varied between 18 and 68 and mean age of the participants was 32.13 (SD = 10.40). The mean age of women was 30.98 (SD = 10.14) and the mean age of men was 35.08 (SD = 10.52).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the research group (N = 570)

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 410 | 71.9 |

| Men | 160 | 28.1 |

| Employment status | ||

| Student | 183 | 32.1 |

| Active worker | 313 | 54.9 |

| Unemployed | 58 | 10.2 |

| Retired | 16 | 2.8 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 213 | 37.4 |

| In a relationship | 89 | 15.6 |

| Married | 268 | 47.0 |

MEASURES

The Type D Personality Scale, UCLA Loneliness Scale, Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire and demographic information form were used in the study.

Type D Personality Scale (D-14 Form). The validity and reliability study of the scale, which was developed by Denollet (2005), in a healthy Turkish population was performed by Öncü and Vayısoğlu (2018). In the present study, the scale was used to evaluate type D personality characteristics of adults. Similar to the original form, the scale, consists of 14 items, has two factors, “negative affectivity” and “social inhibition”. The 5-point Likert-type scale has 7 items in each factor and a value between 0 and 28 can be taken from each factor. The cut-off point of the factors is ≥ 10. Cronbach’s α value of the scale is .85 for negative affectivity and .76 for social inhibition (Öncü & Vayısoğlu, 2018). In the present study, Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the scale was .90 for negative affectivity and .85 for social inhibition.

UCLA Loneliness Scale. The validity and reliability study of the scale, which was developed by Russell et al. (1978), in Turkish population was performed by Demir (1989). In the present study, the scale was used to evaluate loneliness levels of adults. The validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted with normal individuals and individuals who were diagnosed with depression. The 5-point Likert-type scale has 20 items and the scores from the scale vary between 20 and 80. Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the scale was found to be .96, while the test re-test correlation coefficient was found to be .94. It was found that the scale was sufficient to distinguish between individuals who were lonely and those who were not (Demir, 1989). In the present study, Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated as .90.

Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire (BWESQ). The validity and reliability of the Turkish form of the questionnaire, which was developed by Flayelle et al. (2019), was examined by Demir and Vural-Batık (2020). In the present study, the BWESQ was used to evaluate problematic TV series watching behavior. The scale includes items such as: “I watch more TV series than I should”, and “I get annoyed or angry when I’m interrupted while watching my favorite TV series.” Unlike the original questionnaire, the Turkish form shows a four-factor structure. The 4-point Likert-type questionnaire has 31 items and the scores from the questionnaire vary between 31 and 124. A high total score from the questionnaire shows that individuals have a high level of binge-watching. Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the questionnaire is .96 (Demir & Vural-Batık, 2020). In the present study, Cronbach’s α internal consistency coefficient of the questionnaire was calculated as .95.

Demographic information form. The form prepared by the researchers has questions relating to the socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, employment status, TV and series watching habits) of the participants.

DATA ANALYSIS

First, the Mahalanobis distance was calculated, nine outliers were found and the analyses were performed on 570 data by excluding these data. Multivariate normality assumptions were tested for multivariate analyses to be performed. Skewness and kurtosis coefficients were calculated as .35 and –.80 for negative affectivity, as .67 and –.13 for social inhibition, and as .69 and –.19 for loneliness, and as 1.05 and .92 for binge-watching, respectively. Following this, it was found that the scatter diagrams were elliptical and close to elliptical and in the residual plot, the values were found to gather around a linear axis. As a result of Box’s M test conducted to find out whether the variances of the groups were homogeneous, the variances were found to be homogeneous (Box’s M = 17.78, p = .062). In line with all these data, it was found that all assumptions required to perform multivariate analysis were met.

In the analysis of data, Pearson’s moment correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the relationship between type D personality, loneliness and binge-watching. Path analysis was conducted to examine the mediating role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. A bootstrap with 1000 iterations was carried out to obtain coefficients of total, direct and indirect effects. Due to bootstrapping, unstandardized coefficients were provided in the results. Standardized path coefficients and data used for analyses are available upon request.

RESULTS

PRELIMINARY ANALYSES

Table 2 lists the means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations, and Cronbach’s α for the study variables. As expected, positive correlations were found between negative affectivity and loneliness (r = .53, p < .001) and binge-watching (r = .37, p < .001); between social inhibition and loneliness (r = .63, p < .001) and binge-watching (r = .29, p < .001); between loneliness and binge-watching (r = .23, p < .001). Therefore Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients

| Variables | M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NA | 11.92 | 7.40 | .90 | – | .55* | .53* | .37* |

| 2. SI | 8.33 | 6.17 | .85 | – | .63* | .29* | |

| 3. Lon | 36.03 | 11.31 | .90 | – | .23* | ||

| 4. BW | 53.36 | 17.69 | .95 | – |

Note. N = 570; NA – negative affect, SI – social inhibition, Lon – loneliness, BW – binge-watching; *p < .001.

MEDIATING EFFECT ANALYSIS

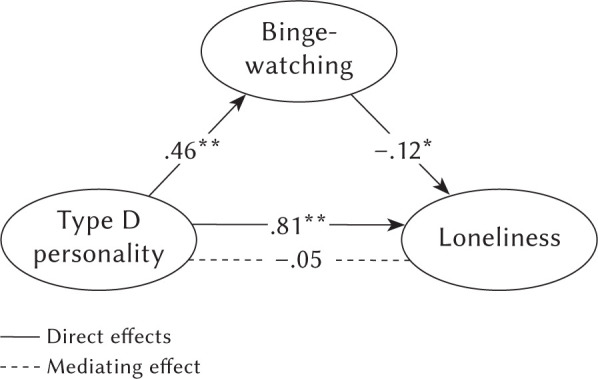

Path analysis was conducted to determine the mediating role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness (Hypothesis 2); the mediating role of binge-watching was examined according to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) model. According to this model, if the statistically significant relationship between type D personality (independent variable) and loneliness (dependent variable) decreases with the inclusion of the binge-watching variable (mediating variable) in the structural model, it is then possible to mention the presence of a mediating effect between the two variables. The results of parameters for the model proposed are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. Gender and age were included as control variables.

Table 3.

Coefficient of standardized β, direct effects and indirect effects

| Variables | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | DE | IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | –.004 | .06 | –.11 | .12 | ||

| Gender | .00 | 1.07 | –2.03 | 2.07 | ||

| Type D personalty | .65** | .03 | .55 | .67 | .81** | –.05 |

| Binge-watching | –.12** | .02 | .10 | .19 | –.12* |

Note. LLCI – lower level of confidence interval; ULCI – upper level of confidence interval; DE – direct effects; IE – indirect effects. Analyses are based on 1000 bootstrap samples. *p < .01, **p < .001.

Figure 1.

The mediating role of binge-watching.

Note. *p < .01, **p < .001

When the standardized coefficients in the path analysis were examined (see Figure 1), it was found that while type D personality was a significant predictor of loneliness (β = .81, p < .001), as a result of the addition of binge-watching to the model as a mediating variable, it was no longer a significant predictor (β = –.05, p = .091). Therefore, it was found that binge-watching had a mediating role in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. Model fit indices of this model are as follows: χ2/df = 3.91, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, GFI = .98, AGFI = .94, NFI = .98, CFI = .98. If the p value is higher than .05 (Çokluk et al., 2018), the χ2/df value lower than 5 (Sumer, 2000) and the RMSEA value is lower than .10 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2020), it can be said that the fit values of the model are within acceptable ranges. GFI and NFI values higher than .95 (Hooper et al., 2008) and a CFI value higher than .97 (Sumer, 2000) show that the model has a good fit. According to the results, it can be said that this model has acceptable fit values. Therefore, the mediating effect of binge-watching posited in Hypothesis 2 was confirmed. According to the model, binge-watching levels of individuals with type D personality are increased and their loneliness levels are decreased by watching more series. Based on this, it can be said that individuals with type D personality tend to decrease their loneliness by watching more series.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, TV series have become easier and faster to access due to technological developments. In this way, binge-watching, which is the most popular way to spend free time for people of almost all age groups (Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020), has also attracted the attention of researchers (Flayelle et al., 2020). These studies seem to focus on conditions of binge-watching as motivation or personality traits and on negative outcomes of binge-watching (Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). In the current study, the relationships between type D personality, loneliness, and binge-watching were examined. Unlike previous studies, binge-watching was treated as a mediating variable rather than a dependent or independent variable.

First, significant positive correlations were found between type D personality, loneliness and binge-watching in this study. In parallel with the results of this study, studies in the literature report that individuals with type D personality have higher levels of loneliness (Bagherian et al., 2011; Ginting et al., 2016; Nefs et al., 2012). Individuals with type D personality feel lonelier and experience lower social support (Spek et al., 2018). However, it can be seen that studies conducted on binge-watching are limited in number. No studies discussing the relationship between binge-watching and type D personality were found; however, characteristics associated with negative affect and social inhibition, which express type D personality, were examined. In these studies, it was found that depressive mood (Ahmed, 2017; Sun & Chang, 2021) and social interaction anxiety (Sun & Chang, 2021; Wheeler, 2015) were associated with binge-watching behavior. These results support the finding that binge-watching is associated with type D personality. It has been stated that personality traits constitute an important factor affecting binge-watching (Orosz et al., 2016; Shim & Kim, 2018) and that individuals who cannot control their behaviors tend to binge watch (Sung et al., 2015). Personality traits determine the results of problematic screen-based activities (Orosz et al., 2016). Individuals showing specific personality traits may particularly be at risk of developing technological addictions. For example, it can be seen that internet addiction, one of the screen-based activities, and type D personality are associated (Holdos, 2017). Individuals with type D personality, who are characterized by a higher level of negative affectivity and higher level of social inhibition, have a higher internet addiction tendency than individuals who do not have type D personality. Individuals with type D personality tend to use the internet more excessively, thinking that it provides a safer environment than the real world to meet the need to socialize (Leung, 2007). As with other behavioral addictions, it seems likely that type D personality may also have an effect on binge-watching behavior.

Unlike a few studies which report no relationship between binge-watching behavior and loneliness (Ahmed, 2017; Tefertiller & Maxwell, 2018; Tukachinsky & Eyal, 2018), the present study reports a positive relationship between binge-watching and loneliness. Similar to this finding, there are a large number of studies which show a positive association between binge-watching and loneliness (Adams & Gordon, 2020; Simmons et al., 2019; Sun & Chang, 2021; Wheeler, 2015). The positive association between binge-watching and loneliness, which was also found in the present study, shows the presence of the cyclical relationship between these two variables. On the one hand, loneliness follows binge-watching behavior, while on the other hand, binge-watching follows loneliness. The individuals who binge-watch to deal with loneliness (Starosta et al., 2019) also seem likely to have decreased loneliness. At this point, it was predicted that this cyclical relationship between loneliness and binge-watching may differ in line with personality traits, and the role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness was also examined.

The results obtained in this area show that binge-watching has a mediating role in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. According to this, binge-watching levels of individuals with type D personality increase and their levels of loneliness decrease as their binge-watching levels increase. Based on this, it can be said that individuals with type D personality tend to decrease their loneliness by watching more series. Similar to this result, Derrick et al. (2009) emphasized the protection of watching favorite television programs against loneliness. In addition, individuals may tend towards binge-watching to cope with loneliness (Pena, 2015; Starosta et al., 2019; Sung et al., 2015). These findings also support the results of the current study.

In addition to the motivation to cope with loneliness, escaping from daily problems (Govaert, 2014; Pena, 2015; Sung et al., 2015), relaxation (Granow et al., 2018) and the need for socialization (Pittman & Sheehan, 2015) can also cause binge-watching. These motivations which lead to binge-watching point to psychological theories which emphasize the importance of gratifying needs (Pittman & Sheehan, 2015). For example, the theory of uses and gratification assumes that viewers look for ways to satisfy their needs by using media such as television and the internet (Rubin, 2008). Binge-watching can be both adaptive and entertaining; it can also be an obsessive and compensatory behavior (Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). For example, while binge-watching can be a social activity (Olding, 2018; Willens, 2013), it can also lead to long-term negative consequences (Ahmed, 2017; Feijter et al., 2016). Binge-watching can increase the feelings of loneliness and isolation (Jacobs, 2017); following this individuals who feel lonely may engage in addictive behaviors to cope with this temporarily (Sung et al., 2015) and show a stronger tendency for binge-watching (Wheeler, 2015). Behavioral addiction symptoms may then occur such as failed attempts to limit watching series, emergence of withdrawal symptoms, and neglect of family and friends (Kubey & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). What is more, individuals who spend too much time in front of the screen can have decreased face-to-face communication with family and friends or experience social isolation (Hamer et al., 2010), which in turn increases the risk of loneliness (Sun & Chang, 2021). It is thought that one of the most important factors determining this cyclical relationship is personality traits and therefore studies produce different results. According to the findings of the current study, it can be said that individuals who have type D personality tend to watch more TV series to cope with the feelings of loneliness and thus try to decrease the feeling of loneliness.

LIMITATIONS

The present study has some limitations. First of all, the factors motivating the individuals to watch series were not discussed and how these motivational sources affected binge-watching and loneliness was not examined. The source of motivation that pushes an individual to watch series can be an important factor that determines how they will be affected by binge-watching. Thus, it can be recommended to identify the factors motivating individuals to binge-watch and to examine the associations of these motivational sources with loneliness in future studies. Another limitation of the study is the different number of female and male participants and that this difference may have affected the study results. Similar to the participant characteristics of the present study, it has been reported by most of the studies conducted on binge-watching that participants mostly consist of women (Flayelle et al., 2020). Due to the fact that women have more series watching habits (Exelmans & Van den Bulck, 2017; Starosta et al., 2019), it can be seen that women are more willing to participate in such studies (Starosta & Izydorczyk, 2020). For this reason, there is a need to conduct studies on groups more balanced in terms of gender and to explore men’s binge-watching behavior. In future studies, it can also be recommended to evaluate individuals immediately after binge-watching behavior and to examine other psychological variables associated with behavioral addictions. Conducting studies on different population groups will also help to better understand binge-watching behavior. On the other hand, it is thought that discussing type D personality and binge-watching behaviors in terms of characteristics related to family, culture, academic and business life will contribute to the literature.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study examined binge-watching, which is a worrying issue for mental health. Binge-watching was discussed as the underlying mechanism of how type D personality is associated with loneliness. The results show that type D personality is associated with loneliness and binge-watching mediates this relationship. It can be said that individuals with type D personality tend to decrease their loneliness by watching series more. Flayelle et al. (2020) stated that it is important to distinguish the healthy way of consuming TV series from the problematic forms of binge-watching. Healthy watching may be a method that can be used in coping with negative behaviors; however, binge-watching may cause more negative consequences. It is recommended to inform individuals about the possible risks of binge-watching and to develop applications and strategies to minimize its negative consequences. Preventive and therapeutic interventions are important, especially for individuals who have personality traits that cause the feeling of loneliness. Preventive interventions should be planned to make these individuals realize the possible risks of binge-watching, to make them explore alternative healthy methods to cope with loneliness and to develop self-regulation skills. In addition, therapeutic interventions should be planned to develop the coping sources and to reduce behavioral addictions of individuals who binge-watch with the motivation to cope with loneliness.

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE – Vural Batik, M., & Demir, M. (2022). The mediating role of binge-watching in the relationship between type D personality and loneliness. Health Psychology Report, 10(3), 157–167.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The American Psychological Association’s ethical standards were followed in conducting the study. Approval was obtained from the Social and Human Sciences Ethics Committee of Ondokuz Mayis University (number of decision: 2021/131). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the first data collection.

References

- 1.Adams, P., & Gordon, H. (2020). Exploring potential psychosocial subgroup differences in the links between binge-watching and loneliness. Paper presented at 23rd Annual Georgia College Student Research Conference.

- 2.Ahmed, A. A. A. M. (2017). New era of TV watching behavior: Binge watching and its psychological effects. Media Watch, 8, 192–207. 10.15655/mw/2017/v8i2/49006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asendorpf, J. B. (1993). Social inhibition: a general-developmental perspective. In H. C. Traue & J. W. Pennebaker (Eds.), Emotion, inhibition, and health (pp. 80–99). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagherian, S. R., Sanei, H., & Baghbanian, A. (2011). The relationship between type D personality and perceived social support in myocardial infarction patients. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 16, 627–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. 10.37//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudali, M., Hamza, M., Bourgou, S., Jouini, L., Charfi, F., & Belhadj, A. (2017). Depression and anxiety among Tunisian medical students “binge viewers”. European Psychiatry, 41, S675–S676. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Çokluk, Ö., Şekercioğlu, G., & Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2018). Sosyal bilimler için çok değişkenli istatistik: SPSS ve LİSREL uygulamaları [Multivariate statistics for social sciences: SPSS and LISREL applications]. Pegem Akademi. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demir, A. (1989). UCLA Yalnızlık ölçeğinin geçerlik ve güvenirliği [Validity and reliability of the UCLA Loneliness Scale]. Psikoloji Dergisi, 7, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demir, M., & Vural-Batık, M. (2020). The study of validity and reliability of the Watching TV Series Motives Questionnaire and the Binge-Watching Engagement and Symptoms Questionnaire. Online Journal of Technology Addiction and Cyberbullying, 7, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denollet, J. (2000). Type D personality. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 255–266. 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00177-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denollet, J. (2005). DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 89–97. 10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denollet, J., Pedersen, S. S., Vrints, C. J., & Conraads V. M. (2013). Predictive value of social inhibition and negative affectivity for cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: The type D personality construct. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75, 873–881. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derrick, J. L., Gabriel, S., & Hugenberg, K. (2009). Social surrogacy: How favored television programs provide the experience of belonging. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 352–362. 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson, S. E., Dal Cin, S., & Byl, H. (2019). An experimental examination of binge watching and narrative engagement. Social Sciences, 8, 19. 10.3390/socsci8010019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Exelmans, L., & Van den Bulck, J. B. (2017). Binge viewing, sleep, and the role of pre-sleep arousal. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13, 1001–1008. 10.5664/jcsm.6704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyal, K., & Cohen, J. (2006). When good friends say goodbye: a parasocial breakup study. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 50, 502–523. 10.1207/s15506878jobem5003_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feijter, D., Khan, V. J., & van Gisbergen, M. S. (2016). Confessions of a ‘guilty’ couch potato understanding and using context to optimize binge watching-behavior. Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video, 59–67. 10.1145/2932206.2932216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flayelle, M., Canale, N., Vögele, C., Karila, L., Maurage, P., & Billieux, J. (2019). Assessing binge-watching behaviors: Development and validation of the “Watching TV Series Motives” and “Binge-watching Engagement and Symptoms” questionnaires. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 26–36. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flayelle, M., Maurage, P., & Billieux, J. (2017). Toward a qualitative understanding of binge-watching behaviors: a focus group approach. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6, 457–471. 10.1556/2006.6.2017.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flayelle, M., Maurage, P., Di Lorenzo, K. R., Vögele, C., Gainsbury, S. M., & Billieux, J. (2020). Binge-watching: What do we know so far? A first systematic review of the evidence. Current Addiction Reports, 7, 44–60. 10.1007/s40429-020-00299-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gierveld, J. D. J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7, 121–130. 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginting, H., Van de Ven, M., Becker, E. S., & Näring, G. (2016). Type D personality is associated with health behaviors and perceived social support in individuals with coronary heart disease. Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 727–737. 10.1177/1359105314536750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein, J. (2013). Television binge watching. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/television-binge-watching-if-it-sounds-so-bad-why-doesit-feel-so-good/2013/06/06/fd658ec0-c198-11e2-ab6067bba7be7813_story.html

- 24.Govaert, H. (2014). How is the concept of “binge-watching” of TV shows by customers going to impact traditional marketing approaches in entertainment sector? (Master’s thesis). Ghent University.

- 25.Granow, V. C., Reinecke, L., & Ziegele, M. (2018). Binge-watching and psychological wellbeing: Media use between lack of control and perceived autonomy. Communication Research Reports, 35, 392–401. 10.1080/08824096.2018.1525347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths, M. D. (1996). Nicotine, tobacco and addiction. Nature, 384, 18. 10.1038/384018a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamer, M., Stamatakis, E., & Mishra, G. D. (2010). Television-and screen-based activity and mental well-being in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 375–380. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holdos, J. (2017). Type D personality in the prediction of internet addiction in the young adult population of Slovak internet users. Current Psychology, 36, 861–868. 10.1007/s12144-016-9475-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hussain, Z., & Pontes, H. M. (2018). Personality, internet addiction, and other technological addictions: a psychological examination of personality traits and technological addictions. In B. Bozoglan (Ed.), Psychological, social, and cultural aspects of internet addiction (pp. 45–71). Information Science Reference/IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs, R. A. (2017). Is there a relationship between binge-watching and depressive symptoms? (Ph.D. thesis). Immaculata University. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenner, M. (2014). Is this TVIV? On Netflix, TVIII and binge-watching. New Media & Society, 18, 257–273. 10.1177/1461444814541523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubey, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). Television addiction is no mere metaphor. Scientific American, 286, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lather, J., & Moyer-Guse, E. (2011). How do we react when our favorite characters are taken away? An examination of a temporary parasocial breakup. Mass Communication and Society, 14, 196–215. 10.1080/15205431003668603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung, L. (2007). Stressful life events, motives for internet use, and social support among digital kids. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10, 204–214. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manley, M. (2016). Netflix and procrastinate: The art of binge-watching in college. Retrieved from https://www.thenortherner.com/arts-and-life/2016/02/23/netflix-and-procrastinate-the-art-of-binge-watching-in-the-college-climate/

- 37.Marlatt, G. A., Baer, J. S., Donovan, D. M., & Kivlahan, D. R. (1988). Addictive behaviors: Etiology and treatment. Annual Review of Psychology, 39, 223–252. 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.001255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore, A. E. (2015). Binge watching: Exploring the relationship of binge watched television genres and colleges at Clemson University. Proceedings of the Graduate Research and Discovery Symposium (GRADS), 138. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nefs, G., Pouwer, F., Pop, V., & Denollet, J. (2012). Type D (distressed) personality in primary care patients with type 2 diabetes: Validation and clinical correlates of the DS14 assessment. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72, 251–257. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oberschmidt, K. (2017). The relationship between binge-watching, compensatory health beliefs and sleep (Bachelor dissertation). University of Twente. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olding, T. (2018). Psychological consequences and antecedents of binge-watching in young adults (Bachelor thesis). University of Twente.

- 42.Orosz, G., Vallerard, J., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Paskuj, B. (2016). On the correlates of passion for screen-based behaviors: The case of impulsivity and the problematic and non-problematic Facebook use and TV series watching. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 167–176. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Öncü, E., & Vayısoğlu, S. K. (2018). D tipi kişilik ölçeğinin Türk toplumunda geçerlilik ve güvenirlilik çalışması [Validity and reliability study of the Type D Personality Scale in Turkish society]. Ankara Medical Journal, 18, 646–656. 10.17098/amj.497485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panda, S., & Pandey, S. C. (2017). Binge watching and college students: Motivations and outcomes. Young Consumers, 18, 425–438. 10.1108/YC-07-2017-00707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pena, L. (2015). Breaking binge: Exploring the effects of binge watching on television viewer reception (Master thesis). Syracuse University. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen, T. (2016). To binge or not to binge: a qualitative analysis of college students’ binge-watching habits. Florida Communication Journal, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pierce-Grove, R. (2017). Just one more: How journalists frame binge watching. First Monday, 22. 10.5210/fm.v22i1.7269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pittman, M., & Sheehan, K. (2015). Sprinting a media marathon: Uses and gratifications of binge-watching television through Netflix. First Monday, 20. 10.5210/fm.v20i10.6138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubin, A. M. (2008). The uses-and-gratifications perspective of media effects. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 165–182). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42, 290–294. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shim, H., & Kim, K. J. (2018). An exploration of the motivations for binge-watching and the role of individual differences. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 94–100. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simmons, S., Eswine, S. A., Horne, C., Shover, A. M., Davis, K., Knox, K., & Heppner, W. (2019). Examining the health and wellness costs associated with binge-watching behaviors. Paper presented at 22nd Annual Georgia College Student Research Conference.

- 53.Spek, V., Nefs, G., Mommersteeg, P. M. C., Speight, J., Pouwer, F., & Denollet, J. (2018). Type D personality and social relations in adults with diabetes: Results from diabetes MILES–the Netherlands. Psychology & Health, 33, 1456–1471. 10.1080/08870446.2018.1508684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starosta, J. A., & Izydorczyk, B. (2020). Understanding the phenomenon of binge-watching: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 4469. 10.3390/ijerph17124469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Starosta, J., Izydorczyk, B., & Lizyńczyk, S. (2019). Characteristics of people’s binge-watching behavior in the “entering into early adulthood” period of life. Health Psychology Report, 7, 149–164. 10.5114/hpr.2019.83025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sumer, N. (2000). Structural equation modeling: Basic concepts and sample applications. Turkish Psychology Writings, 3, 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun, J. J., & Chang, Y. J. (2021). Associations of problematic binge-watching with depression, social interaction anxiety, and loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1168. 10.3390/ijerph18031168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sung, Y. H., Kang, E. Y., & Lee, W. N. (2015). A bad habit for your health? An exploration of psychological factors for binge-watching behavior. Paper presented at 65th Annual International Communication Association Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

- 59.Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2020). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Nobel Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tefertiller, A. C., & Maxwell, L. C. (2018). Depression, emotional states, and the experience of binge-watching narrative television. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 26, 278–290. 10.1080/15456870.2018.1517765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trouleau, W. (2016) Just one more: Modeling binge watching behaviour. Proceeding of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1215–1224. 10.1145/2939672.2939792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tukachinsky, R., & Eyal, K. (2018). The psychology of marathon television viewing: Antecedents and viewer ınvolvement. Mass Communication and Society, 21, 275–295. 10.1080/15205436.2017.1422765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaterlaus, J. M., Spruance, L. A., Frantz, K., & Kruger, J. S. (2019). College student television binge watching: Conceptualization, gratifications, and perceived consequences. The Social Science Journal, 56, 470–479. 10.1016/j.soscij.2018.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walton-Pattison, E., Dombrowski, S. U., & Presseau, J. (2018). Just one more episode: Frequency and theoretical correlates of television binge watching. Journal of Health Psychology, 23, 17–24. 10.1177/1359105316643379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ward, B. (2014). Binge TV viewing is a popular indulgence, for better or worse. Star Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.startribune.com/lifestyle/238655421.html

- 66.Weng, C. Y., Denollet, J., Lin, C. L., Lin, T. K., Wang, W. C., Lin, J. J., Wong, S. S., & Mols, F. (2013). The validity of the Type D construct and its assessment in Taiwan. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 46. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wheeler, K. S. (2015). The relationships between television viewing behaviors, attachment, loneliness, depression, and psychological well-being (Honors master thesis). Georgia Southern University. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Willens, M. (2013). Face it: Binge-viewing is the new date night. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michelewillens/binge-watching-downton-abbey-breaking-bad-house-ofcards_b_2764830.html

- 69.Williams, L., O’Connor, R. C., Howard, S., Hughes, B. M., Johnston, D. W., Hay, J. L., O’Connor, D. B., Lewis, C. A., Ferguson, E., Sheehy, N., Grealy, M. A., & O’Carroll, R. E. (2008). Type-D personality mechanisms of effect: The role of health-related behavior and social support. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64, 63–69. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]