Abstract

Background

Achalasia is an oesophageal motility disorder, of unknown cause, which results in increased lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) tone and symptoms of difficulty swallowing. Treatments are aimed at reducing the LOS tone. Current endoscopic therapeutic options include pneumatic dilation (PD) or botulinum toxin (BTX) injection.

Objectives

To undertake a systematic review comparing the efficacy and safety of two endoscopic treatments, PD and intrasphincteric BTX injection, in the treatment of oesophageal achalasia.

Search methods

Trials were initially identified by searching MEDLINE (1966 to August 2008), EMBASE (1980 to September 2008), ISI Web of Science (1955 to September 2008), The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2008. Searches in all databases were conducted in October 2005 and updated in September 2008 and April 2014. The Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE, sensitivity maximising version in the Ovid format, was combined with specific search terms to identify randomised controlled trials in MEDLINE. The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted for use in the other databases that were searched.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing PD to BTX injection in individuals with primary achalasia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed study quality assessment and data extraction.

Main results

Seven studies involving 178 participants were included. Two studies were excluded from the meta‐analysis of remission rates on the basis of clinical heterogeneity of the initial endoscopic protocols. There was no significant difference between PD or BTX treatment in remission within four weeks of the initial intervention; with a risk ratio of remission of 1.11 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.27). There was also no significant difference in the mean oesophageal pressures between the treatment groups; with a weighted mean difference for PD of ‐0.77 (95% CI ‐2.44 to 0.91, P = 0.37). Data on remission rates following the initial endoscopic treatment were available for three studies at six months and four studies at 12 months. At six months 46 of 57 PD participants were in remission compared to 29 of 56 in the BTX group, giving a risk ratio of 1.57 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.08, P = 0.0015); whilst at 12 months 55 of 75 PD participants were in remission compared to 27 of 72 BTX participants, with a risk ratio of 1.88 (95% CI 1.35 to 2.61, P = 0.0002). No serious adverse outcomes occurred in participants receiving BTX, whilst PD was complicated by perforation in three cases.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this meta‐analysis suggest that PD is the more effective endoscopic treatment in the long term (greater than six months) for patients with achalasia.

Plain language summary

Endoscopic balloon dilation versus botulinum toxin (Botox) injection for managing achalasia, a condition causing difficulty in swallowing

Achalasia is an oesophageal motility disorder which results in increased lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) tone and symptoms of difficulty swallowing. Treatments are aimed at reducing the tone of the LOS and include the endoscopic options of pneumatic dilation (PD) or local botulinum toxin (BTX) injection. We set out to undertake a systematic review comparing randomised controlled trials that examined the efficacy and safety of PD and BTX injection in people with achalasia. We searched databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, ISI Web of Science, and The Cochrane Library) in April 2014 for reports of relevant randomised controlled trials. Seven randomised controlled trials were identified for inclusion in the review, and five were suitable for meta‐analysis. Meta‐analysis suggested that, although both interventions had similar initial response rates, the remission rates at six and 12 months were significantly greater with PD than with BTX injection.

Background

Description of the condition

Achalasia is an oesophageal motility disorder of unknown cause that manifests as symptoms of difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), with pooling of food and secretions in the lower oesophagus. The annual incidence has been estimated at approximately 1:100,000 (Mayberry 1987; Howard 1992). The onset of symptoms is often insidious, usually between the ages of 25 and 60 years, and symptoms gradually progress over a period of years (Eckardt 1997).

The condition is characterised by degeneration of ganglion cells, predominantly the inhibitory neurons in the myenteric plexus of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS). This leads to a rise in the basal tone of the sphincter, loss of peristalsis in the distal oesophagus, and a lack of coordinated LOS relaxation in response to swallowing. Achalasia may be suspected from the clinical history, however radiographic, endoscopic, and, most importantly, manometric assessment are need to confirm the diagnosis (Reynolds 1989).

The function of the degenerated myenteric plexus neurons cannot be restored, therefore treatments are aimed at reducing the tone of the LOS. These include pharmacological therapy, surgical myotomy, and endoscopic pneumatic dilation (PD) or intrasphincteric botulinum toxin (BTX) injection. Pharmacological treatments such as oral nitrates, calcium channel blockers, anticholinergic agents, and beta‐adrenergic agonists have proven disappointing to date (Bassotti 1999; Wen 2004).

Description of the intervention

Surgical myotomy (Heller's myotomy) is an effective treatment option with good long‐term results. Whilst laparoscopic Heller's myotomy is generally accepted as the operative procedure of choice, endoscopic therapy remains a valid option in the primary management of achalasia (Urbach 2001; Frantzides 2004; Vela 2004).

Standard endoscopic therapeutic options include PD or BTX injection. A variety of balloon types and protocols have been used to treat this condition, with reported long‐term efficacy of up to 90%. The major complication associated with PD is oesophageal perforation, which occurs in up to 3% of cases (Katz 1998; Kadakia 2001). PD appears to be the least costly treatment (Imperiale 2000). Recently, a novel endoscopic myotomy procedure, peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), has been developed which has shown similar short‐term outcomes to Heller's myotomy (Pasricha 2007; Inoue 2010; Von Renteln 2013). POEM is a complex endoscopic procedure which is only performed in specialist centres.

Why it is important to do this review

Intrasphincteric injection of BTX is an alternative endoscopic therapy to PD (Pasricha 1994; Pasricha 1995). It is a safe procedure, being associated with few side effects or complications (Cuilliere 1997). Usually 80 to 100 units of BTX are injected with a sclerotherapy needle in divided doses into the four quadrants of the LOS, under direct vision. Although an efficacy of about 85% in the short‐term period has been reported, this decreases to 50% at six months and 30% after one year (Annese 1998; Bassotti 1999; Kolbasnik 1999).

Objectives

To undertake a systematic review comparing the efficacy and safety of two endoscopic treatments, intrasphincteric botulinum toxin (BTX) injection and pneumatic dilation (PD), in the treatment of oesophageal achalasia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding, comparing endoscopic intrasphincteric BTX injection to endoscopic PD in the treatment of achalasia.

Types of participants

Individuals of any age diagnosed with achalasia by a combination of clinical, endoscopic, radiographic, or manometric investigations, including patients who had received previous endoscopic treatments.

Types of interventions

The following interventions were compared in the treatment of achalasia:

endoscopic BTX injection;

endoscopic PD.

Varying doses and frequencies of BTX, and different types of balloon and methods of PD were considered.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Symptom remission rates within the first month, at six months, and at 12 months

Secondary outcomes

Lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) pressure confirmed by oesophageal manometry post‐treatment

Complications directly related to the endoscopic therapy

Quality of life post‐intervention

Cost‐effectiveness

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Searches were conducted to identify all published and unpublished randomised controlled trials. Articles published in any language were included. Trials were identified by searching MEDLINE (1946 to week 3 March 2014), EMBASE (1980 to week 12 2014), ISI Web of Science (1955 to March 2014), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(January 2014). Searches in all databases were conducted initially in October 2005 and updated in September 2008, July 2011, and April 2014. The Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE, sensitivity maximising version in the Ovid format (Higgins 2008), was combined with the search terms in Appendix 1 to identify randomised controlled trials in MEDLINE. The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted for use in the other databases that were searched for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists from trials selected by electronic searching were handsearched to identify further relevant trials. Published abstracts from conference proceedings in the United European Gastroenterology Week (published in Gut) and Digestive Disease Week (published in Gastroenterology) were handsearched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently scanned the abstract of each trial identified by the search to determine eligibility. The authors were not blinded to the sources of the trials. We selected full articles for further assessment if the abstract suggested the study was a randomised controlled trial of patients with achalasia comparing balloon dilation to BTX injection. If these criteria were unclear from the abstract, the full article was retrieved for clarification. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included for review and data extraction. Papers not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from published reports using predetermined standardised forms. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the review authors. The following data were extracted wherever possible:

method of randomisation;

blinding for outcome assessor, patient, and carer;

criteria for patient inclusion and exclusion;

history of previous treatment for achalasia;

participants' characteristics including mean or median age, age range, sex ratio;

number of participants assigned to each treatment group;

number of co‐morbid conditions, with details of intervention;

type of intervention per endoscopic session, type of balloon and pressures attained;

effect on symptoms;

effect on LOS pressure;

effect on quality of life;

number and frequency of procedure related complications;

duration of therapy and any co‐interventions;

frequency of re‐interventions;

number of participants withdrawn and reasons for these withdrawals;

adverse reactions and outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Quality assessment of trials

Two review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the selected trials using the following criteria:

the method of randomisation;

allocation concealment;

baseline comparability of study groups;

blinding and completeness of follow up.

We did not use blinding of participants or intervention providers as an assessment criterion given the nature of the interventions being studied. Trials were graded: A ‐ adequate, B ‐ unclear, C ‐ inadequate on each criterion and thus each randomised controlled trial (RCT) was graded as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias. If it was unclear whether a criterion had been met, we sought further information from the author. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data synthesis

Statistical analyses

Statistical guidance was available from the editorial base and the review authors' host institutions. The variation in type of balloon used and pressures attained at dilation, the dose of BTX injected, and the history of previous endoscopic treatment were considered as potential causes of heterogeneity. Dichotomous data were summarised using the risk ratio and reported with 95% confidence intervals. The relative risk of remission was calculated at each of the three time points. Continuous data were summarised using weighted mean difference and reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

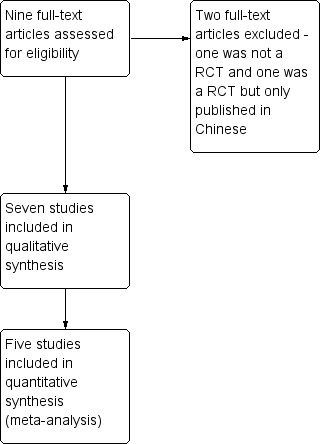

We identified studies using the search criteria and assessed nine full‐text articles for eligibility, as shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The seven included studies were RCTs involving patients with a diagnosis of primary achalasia based on clinical, endoscopic, manometric, and radiographic criteria. Please see Characteristics of included studies.

Treatments

A 30 mm diameter PD balloon was used in five studies (Annese 1996; Vaezi 1999; Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Zhu 2009). In one of these PD was performed on three consecutive days (Annese 1996), with a 35 mm balloon being used on the second and third day. The total BTX dose administered varied from 60 to 100 units in these five studies.

The two remaining studies compared a 40 mm balloon either as a single PD session (Bansal 2003) or two sessions one day apart (Muehldorfer 1999) to a total BTX dose of 80 U.

In one study participants not responding to the initial BTX injection received a further injection one week later (Muehldorfer 1999).

Some participants who either failed to respond to the initial endoscopic treatment or who relapsed during the study period underwent a repeat procedure or were crossed over to the alternative treatment in all six studies.

Outcomes

Changes in achalasia symptoms and LOS pressure in response to both treatments were assessed between one and four weeks after the initial treatment in all studies. The methods used for scoring achalasia symptoms varied between studies; however, most defined remission as 50% or greater improvement in the symptom score. The symptom scores were further assessed in all studies, and LOS pressure in three of the studies, over a 12 month period (Annese 1996; Bansal 2003; Zhu 2009). Data on the response to the initial endoscopic treatment only, at six and 12 months, were available in five of the studies (Annese 1996; Muehldorfer 1999; Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Zhu 2009).

All studies compared cumulative remission over a 12 month period, however the definition of remission varied between studies. Remission was defined as a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms in three studies (Muehldorfer 1999; Vaezi 1999; Mikaeli 2001). A further study (Bansal 2003) calculated a total symptom score derived from the combination of the symptoms of dysphagia, chest pain, and regurgitation, each given a score of 0 to 3. This score was then divided into four grades (0 to 3), defined as symptom scores of 0 to 1, 2 to 3, 4 to 6, and > 6 respectively. Remission was defined as a symptom score reduction of > 1 grade, with a sustained response. Remission was not specifically defined in the study by Ghoshal (Ghoshal 2001) but all responders experienced at least a 50% reduction in symptoms. Annese (Annese 1996) calculated a similar symptom score (0 to 9) and defined remission as a score of < 2. Zhu (Zhu 2009) calculated a total symptom score derived from the combination of the symptoms of solid and liquid dysphagia, active and passive regurgitation, and chest pain. The severity of each of these symptoms was scored on a scale of 0 to 3, thus the highest obtainable score was 15. A symptom score < 4 was deemed a clinical response. Only two studies used Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis to assess remission rates after a single endoscopic treatment (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001).

Quality of life and cost‐effectiveness were not measured in any of the included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 10 studies from the analysis (Figure 1). One full‐text paper (Allescher 2001) and one meeting abstract (Jung 2012) reported non‐randomised studies. Three studies, published as meeting abstracts, were preliminary results of included studies (Bansal 1996; Muehldorfer 1998; Malekzadeh 2000). Four studies, published as meeting abstracts only, were excluded as we were unable to contact the authors to obtain additional information regarding the studies (Gaudric 1996; Nebendahl 1998; des Varannes 1999; Linghu 2013). One study (Zhou 2012) was not included as only the abstract was published in English and we were unable to contact the author to obtain additional information. Please see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Method of randomisation

The method of randomisation was adequate in four studies (Vaezi 1999; Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Zhu 2009), and unclear in the remaining three (Annese 1996; Muehldorfer 1999; Bansal 2003).

Blinding

Two of the seven studies were double blind trials (Bansal 2003; Zhu 2009). A further study reported blinding of those assessing LOS pressure (Vaezi 1999). In the studies by Annese 1996; Ghoshal 2001; and Mikaeli 2001 the assessors were not blinded. The study by Annese 1996 had been classified as double blind in the original review but has been reclassified in this update. Blinding was unclear in the remaining study (Muehldorfer 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

Follow up

A total of 11 out of 239 participants were excluded from the post‐treatment analysis either due to loss to follow up or non‐compliance with the study protocols. In one study five (11%) of the initially randomised patients were excluded from the post‐treatment analysis (Vaezi 1999).

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline comparability of treatment groups

The clinical characteristics of participants in both treatment groups were similar in all but one study: the BTX group were older in the study by Mikaeli 2001. Two studies included participants who had been unsuccessfully treated with PD in the past: eight of the PD group and seven of the BTX group in the study by Muehldorfer 1999; two of the BTX group in the study by Ghoshal 2001.

Effects of interventions

Response to initial endoscopic treatment

Five studies compared a single BTX injection to a single PD initially (Vaezi 1999; Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Bansal 2003; Zhu 2009). In the two remaining studies the initial PD treatment consisted of repeated dilatations within a period of three days and was compared to a single BTX injection (Annese 1996), or an initial injection and a subsequent injection one week later in non‐responders (Muehldorfer 1999). Due to this clinical heterogeneity in treatment protocols neither of these studies were included in this analysis.

Following the initial endoscopic therapy 82 out of 95 PD participants were in remission compared to 73 out of 94 BTX participants, with a risk ratio of remission of 1.11 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.27; Analysis 1.1) for PD. This did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.12).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection, Outcome 1 Initial remission.

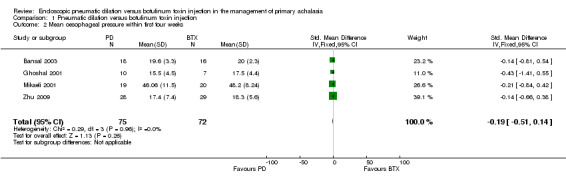

Four of the five studies reported mean oesophageal pressures within four weeks of the initial endoscopic treatment (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Bansal 2003; Zhu 2009). The remaining study reported median and interquartile scores; individual patient data were not available (Vaezi 1999). There was no significant difference in the mean oesophageal pressures between the treatment groups, with a weighted mean difference for PD of ‐0.79 (95% CI ‐2.29 to 0.71; Analysis 1.2). Sensitivity analysis was performed by altering the statistical test (odds ratio or risk difference) and model (random‐effects or fixed‐effect) and did not change the results. There was no statistical heterogeneity between the studies.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection, Outcome 2 Mean oesophageal pressure within first four weeks.

In the study by Annese 1996 eight participants were randomised to receive 100 U of BTX and eight to undergo PD. Two further PD sessions were performed on consecutive days. Remission was defined as a symptom score of 2 (range 0 to 9). All participants were in remission at one month. The mean LOS pressure was reduced by 73% (37 to 9.9 mm Hg) in the PD group and by 48% (34.1 to 17.6 mm Hg) in the BTX group at one month; this was not statistically significant (Table 1). In the study by Muehldorfer 1999 12 participants were randomised to receive 80 U BTX and 12 to undergo PD. A further PD was performed two days later. Remission was defined as a 50% or greater improvement in the median symptom score (range 0 to 20). At one week 10 of 12 (83%) PD participants compared to 8 of 12 (67%) BTX participants were in remission (P = 0.64). A second injection achieved therapeutic success in one of 4 non‐responders; thus, 9 of 12 BTX participants (75%) responded positively overall. Mean LOS pressure readings before and after treatment were assessed in 7 PD and 9 BTX participants. The mean LOS pressure was reduced by 50%, from 35 mm Hg to 17 mm Hg in the PD group (P < 0.001). In the BTX group a 44% reduction was observed, 39 mm Hg to 22 mm Hg (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

1. Studies meeting selection criteria but excluded from the meta‐analysis.

| Study | methods | Remission 1 month | Remission 6 months | Remission 12 months | Mean LOS pressure | Complications |

| Annese 1996 | 8 participants 100 U BTX and 8 participants PD PD: day 1 ‐ Rigiflex 30 mm. Day 2 and 3 ‐ 35 mm balloon BTX relapsers retreated | PD 8/8 BTX 8/8 | PD 8/8 BTX 6/8 | PD 8/8 BTX 1/8 | PD ‐72% BTX ‐44% | none |

| Muehldorfer 1999 | 12 participants 80 U BTX and 12 PD 40m day 1 and 3 BTX repeated at 1 week in 4 non‐responders | PD 10/12 BTX 9/12 | PD 9/12 BTX 6/12 | PD 8/12 BTX 3/12 | PD ‐50% BTX ‐44% | none |

Remission at six months and 12 months

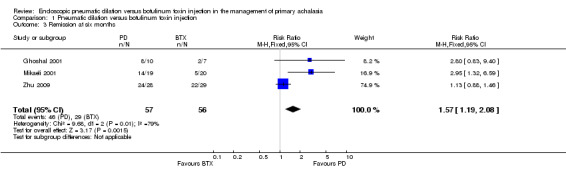

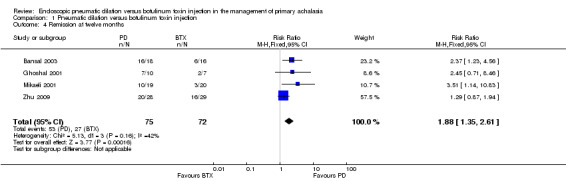

Data on remission rates following both initial treatments were available for three studies (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Zhu 2009) at six months, and four studies at 12 months (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001; Bansal 2003; Zhu 2009). The six and 12 month remission rates in the study by Vaezi 1999 included participants who had undergone a second endoscopic treatment, therefore these data were not included in our analysis.

At six months 46 of 57 PD participants were in remission compared to 29 of 56 in the BTX group, giving a risk ratio of 1.57 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.08, P = 0.0015; Analysis 1.3); whilst at 12 months 55 of 75 PD participants were in remission compared to 27 of 72 BTX participants, with a risk ratio of 1.88 (95% CI 1.35 to 2.61, P = 0.0002; Analysis 1.4). Sensitivity analysis was performed by altering the statistical test (odds ratio or risk difference) and model (random‐effects or fixed‐effect) and did not change the results at the one and 12 month analysis of remission but did at the six month analysis. The risk ratio random‐effects model in the six month analysis was 1.94 (95% CI 0.77 to 4.85, P = 0.16). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity in the six month remission analysis (Analysis 1.3). The remission rates for BTX in the largest study (Zhu 2009) were greater than the other two studies included in this analysis (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection, Outcome 3 Remission at six months.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection, Outcome 4 Remission at twelve months.

In the study by Annese 1996 six of eight (80%) BTX patients were in remission at six months, while only one (12.5%) was in remission at 12 months. All of the PD patients remained in remission (Table 1). In the study by Muehldorfer 9 of 12 (75%) PD patients were in remission at six months compared to 6 of 12 (50%) BTX patients, whilst the numbers in remission at 12 months were 8 (66%) and 3 (25%) respectively (Muehldorfer 1999) (Table 1).

Complications

A total of 188 PD procedures and 151 BTX injections were performed in the six studies, either as the initial treatment or as a subsequent treatment in those who failed to respond to the initial treatment (PD or BTX) or who relapsed. BTX injection was not associated with any serious complications. Three oesophageal perforations were reported following PD.

Quality of life and cost‐effectiveness

Quality of life and cost‐effectiveness analyses were not performed in this review as they were not assessed in any of the selected studies.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The initial PD protocols of two studies (Annese 1996; Muehldorfer 1999) involved repeated dilation over a short period, whilst the remaining five studies initially compared a single PD session to a single BTX injection. This was felt by both of the study authors to be clinically relevant but precluded these studies from inclusion in the meta‐analysis (Table 1). Ideally Kaplan‐Meier plots and log‐rank testing should be used to compare duration of remission, however only two studies used this approach to compare remission rates after a single endoscopic treatment (Ghoshal 2001; Mikaeli 2001).

There was no significant difference in remission within the first four weeks. Remission rates were greater at both six and 12 months for PD compared to BTX (PD rate approximately double the rate for BTX at 12 months), however two of the four studies were excluded from the six month analysis (Vaezi 1999; Bansal 2003) and one from the 12 month analysis (Vaezi 1999) due to incomplete data. Data on the remission rate at six months following BTX injection were not clear in the study by Bansal 2003. We were unable to contact the corresponding author for more information. In the study by Vaezi a second endoscopic treatment was performed in participants who relapsed during the study period and these participants were included in the outcomes analysis at six and 12 months (Vaezi 1999). It was not possible to obtain data from the corresponding author of this study on the outcomes at six and 12 months for participants who did not receive a second endoscopic treatment. It is unlikely that the missing data would significantly alter the outcome of this meta‐analysis. The differences in outcomes highlighted in this analysis could be due to differences in the number of studies and of participants included at the various time points.

A comparison of the effect of either treatment on achalasia symptoms was not possible due to inter‐study variation in the scoring of symptoms, therefore we looked at remission rates at the various time points. Remission was defined as a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms in the studies by Vaezi 1999 and Mikaeli 2001. Remission in the study by Ghoshal 2001 equated to a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms, whilst in the study by Bansal 2003 remission was approximately equivalent to a 50% reduction in achalasia symptoms (individual patient data were not available). Zhu 2009 calculated a total symptom score derived from symptoms of solid and liquid dysphagia, active and passive regurgitation, and chest pain; each scored on a scale of 0 to 3. A symptom score < 4 was deemed a clinical response, which roughly equated to a 50% or greater response. We analysed LOS pressure within the first four weeks of treatment as this was assessed in all six of the selected studies.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Both the number of studies and the number of participants randomised to either treatment were small. A total of 239 achalasia participants were enrolled across the seven studies, with the largest study having 60 participants (Zhu 2009); 122 participants were randomised to undergo PD and 117 to receive BTX. One RCT that involved 80 participants was not included as the only information that was available was from the abstract of the paper (Zhou 2012). The outcomes reported in the abstract are in keeping with the result of this meta‐analysis and allowing for the possibility of a high risk of bias, the 12 month clinical remission rates in this study were greater for PD than BTX, 73.2% and 61.5% respectively.

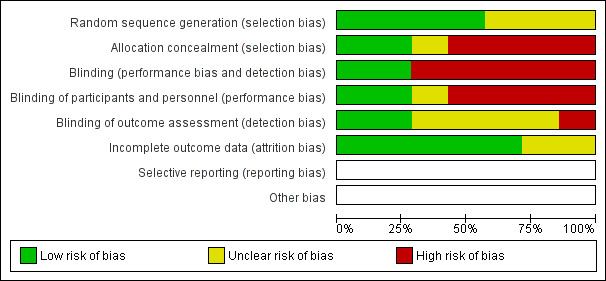

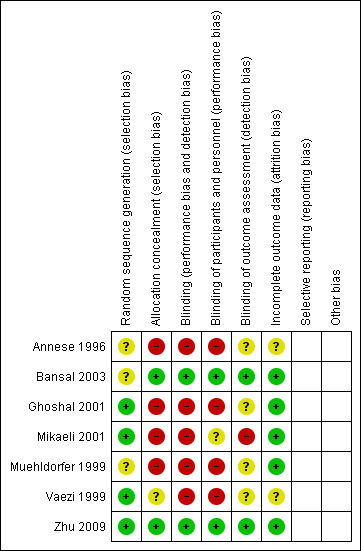

Quality of the evidence

The overall methodological quality of these studies was good although the risk of bias is high (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Only one of the included studies was double blind (Bansal 2003). Because of the nature of the interventions in the included studies blinding was not always possible; therefore these studies are open to the possibility of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The overall clinical characteristics of the participants in both treatment groups in the studies included in the meta‐analysis were similar. However, in the study by Mikaeli 2001 the BTX group were slightly older. Two patients who received BTX had previously had an unsuccessful PD (Ghoshal 2001). Of the 239 participants only 11 were excluded from the post‐treatment analysis; five of these were from the same study (Vaezi 1999).

Despite the small number of studies and participants, four of the studies that were identified by the search were excluded (Gaudric 1996; Nebendahl 1998; des Varannes 1999; Linghu 2013) as they were only published as meeting abstracts and further information regarding the exact nature of the treatments and methodological quality, in particular the method of randomisation and the baseline comparability of the treatment groups, was not available. A further study was excluded as only the information in the paper's abstract was available (Zhou 2012).

In summary, the results of this review suggest that PD has a better long‐term efficacy. These studies suggest little difference in the response rates to initial treatment, however at 12 months the remission rate with PD was approximately twice that of BTX. No serious adverse outcomes occurred in participants receiving BTX. PD was complicated by perforation in three cases.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Existing randomised controlled trials in this area measure multiple interventions and outcomes, making comparisons difficult for clinicians. Pneumatic dilation (PD) appears to be associated with better long‐term outcomes and reduced re‐intervention rates when compared to botulinum toxin (BTX) injection. However, oesophageal perforation remains a risk with balloon dilatation.

Implications for research.

Large blinded randomised controlled trials with comparable treatment protocols and outcome assessment criteria are lacking.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 August 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | One new RCT identified and included in meta‐analysis. Conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 23 July 2014 | New search has been performed | Searches rerun and review updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 October 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 2 July 2009 | Amended | Revision to the risk of bias characteristic of included studies. |

| 2 February 2009 | New search has been performed | Review updated. No new studies. Conclusions not changed. |

| 16 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 July 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. |

| 29 October 2005 | Amended | New studies found and included or excluded. |

| 18 October 2005 | Amended | New studies sought but none found. |

| 1 October 2005 | New search has been performed | Minor update. |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Disease Review Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt.

2. controlled clinical trial.pt.

3. randomized.ab.

4. placebo.ab.

5. drug therapy.fs.

6. randomly.ab.

7. trial.ab.

8. groups.ab.

9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

10. humans.sh.

11. 9 and 10

12. exp esophageal achalasia/

13.(esophageal adj2 achalasia).tw.

14. achalasi$.tw.

15. or/12‐14

16. exp botulinum toxins/

17. botox.tw.

18. botulinum$.tw.

19. or/16‐18

20. exp balloon dilatation/

21. angioplasty.tw.

22. (balloon adj5 dilat$).tw.

23. (pneumatic adj5 balloon).tw.

24. or/20‐23

25. 11 and 15 and 19 and 24

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Initial remission | 5 | 189 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.97, 1.27] |

| 2 Mean oesophageal pressure within first four weeks | 4 | 147 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.19 [‐0.51, 0.14] |

| 3 Remission at six months | 3 | 113 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.19, 2.08] |

| 4 Remission at twelve months | 4 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.88 [1.35, 2.61] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Annese 1996.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation was not stated Initially BTX versus placebo saline injection. All placebos relapsed and treated by PD BTX relapsers were retreated Remission ‐ symptom score ≤ 2 Exclusion criteria: < 18 yrs, previous PD or myotomy, sigmoid shaped oesophagus | |

| Participants | 16 treatment naive adult participants Baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were similar | |

| Interventions | 8 participants received 100 U BTX and 8 participants underwent PD PD: day 1 ‐ Rigiflex 30 mm, day 2 and 3 ‐ 35 mm balloon | |

| Outcomes | Clinical assessment using mean symptom score ‐ dysphagia, chest pain and regurgitation; each scored 0 to 3 Mean LOS pressure (mm Hg) Barium retention studies (mean % retained at 10 min) Outcomes assessed at 1, 6, 12 months Remission defined as a symptom score ≤ 2 | |

| Notes | No complications reported All patients were assessed at 6 months; 6 participants were lost to follow up at 12 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Initial randomisation and therapy was double blind ‐ BTX or placebo saline injection. The placebo group then had three PD sessions as they all failed to respond. This aspect of the study was not blinded |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Initial randomisation and therapy was double blind ‐ BTX or placebo saline injection. The placebo group then had three PD sessions as they all failed to respond. This aspect of the study was not blinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Initial randomisation and therapy was double blind ‐ BTX or placebo saline injection. The placebo group then had three PD sessions as they all failed to respond. This aspect of the study was not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the assessors were blinded to the therapies |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Low attrition bias at 1 and 6 months but high at 12 months |

Bansal 2003.

| Methods | Double blind RCT Method of randomisation was not stated Crossover to other treatment if failed treatment at any time Exclusion criteria: previous treatment, < 18 yrs, poor surgical candidates Remission ‐ decrease in symptom grade ≥ 1 | |

| Participants | 34 treatment naive adults Baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were similar | |

| Interventions | BTX 80 U 4 quadrants Witzel 40 mm balloon ‐ 180 to 300 mm Hg x 3 min Sham injection or dilatation | |

| Outcomes | Mean symptom score ‐ dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation (0 to 9) Dysphagia score (0 to 21) Dysphagia severity (0 to 10) Pain severity (0 to 10) Global assessment (0 to 10, graded 0, 1, 2, 3) Weight gain (%) Mean LOS pressure (mm Hg)at 3 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months | |

| Notes | 2 perforations in PD group 2 lost to follow up Low bias | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment and sham procedures |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blinding to initial therapy |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blinding to initial therapy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Assessors blinded to therapy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two lost to follow up |

Ghoshal 2001.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation ‐ computer generated random numbers Non‐responders and relapsers retreated with PD Remission ‐ dysphagia score 0 or 1 | |

| Participants | 17 participants 2 BTX group had previous PD Baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were similar | |

| Interventions | BTX 60 to 80 units Rigiflex 30 mm ‐ 1 min 10 to 15 psi | |

| Outcomes | Dysphagia (0 to 3), chest pain (Yes or No), regurgitation (Yes or No) Symptoms assessed at 1 week, 3 to 6 monthly Mean LOS pressure at 1 week | |

| Notes | No complications | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Method of randomisation ‐ computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients were unblinded |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the assessors were blinded to the therapies |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

Mikaeli 2001.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation ‐ computer generated random numbers Repeat treatment for non‐response and relapse (same BTX dose or 35 mm PD) Remission ‐ > 50% improvement in symptom score Exclusion criteria: < 40 yrs | |

| Participants | 40 treatment naive participants (> 40 yr old) BTX group older | |

| Interventions | BTX 200 (80) U 4 quadrants Rigiflex 30 mm ‐ 10 psi x 30 sec | |

| Outcomes | Mean symptom (0 to 15) 1, 6, 12 months Mean LOS pressure at 1 month | |

| Notes | No complication 1 lost to follow up High risk of bias as not double blind | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients were unblinded |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Clinical assessor was aware of the treatment received by the patient |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | One participant lost to follow up |

Muehldorfer 1999.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation not stated Exclusion criteria: secondary achalasia, dysphagia score < 10/20, previous gastro‐oesophageal surgery Remission ‐ ≥ 50% reduction in symptoms | |

| Participants | 24 participants ‐ 15 had previously undergone PD Baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were similar | |

| Interventions | BTX 80 Units 40 mm PD ‐ up to 300 mm Hg x 3 min day 1 and 3 | |

| Outcomes | Median score (0 to 20) for 4 symptoms ‐ dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, and heartburn at 1 week, 1 month and 6 monthly for 30 months Mean LOS pressure post‐treatment in 16 patients | |

| Notes | No complications | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients were unblinded |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the assessors were blinded to the therapies |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No participants lost to follow up |

Vaezi 1999.

| Methods | RCT Method of randomisation ‐ computer generated random numbers Retreated if no response at 1 month (35 mm PD balloon) Exclusion criteria: previous treatment, < 18 yrs, neuromuscular disorder, NYHA grade III or IV Remission ‐ > 50% improvement in symptoms | |

| Participants | 47 treatment naive participants Baseline characteristics of both treatment groups were similar 5 participants were excluded from the analysis ‐ 2 BTX group and 3 PD group | |

| Interventions | BTX 100 U Rigiflex 30 mm ‐ 9 to 15 psi x 1 minute | |

| Outcomes | Median symptom score (0 to 15) Symptoms assessed at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months Median LOS pressure at 1 month Barium retention ‐ height and width 1, 6, 12 months | |

| Notes | 1 perforation in PD group ‐ excluded from analysis 4 lost to follow up ‐ excluded from analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Method of randomisation ‐ computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Patients were unblinded |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Patients were unblinded. Nature of therapies administered did not allow blinding of endoscopists |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the assessors were blinded to the therapies |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 5 patients not included in analysis, 4 in the PD group |

Zhu 2009.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 90 participants divided into three groups. Adults > 40 yrs. Treatment naive Three treatment groups ‐ A) 100 U BTX, B) PD with 30 mm Rigifex balloon, C) PD followed by BTX injection 15 days later Baseline characteristics similar in the two relevant groups Outcomes based on single treatment |

|

| Interventions | Three treatment groups ‐ A) 100 U BTX, B) PD with 30 mm Rigifex balloon, C) PD followed by BTX injection 15 days later | |

| Outcomes | Clinical assessment (mean symptoms score based on dysphagia for solids and liquids, active and passive regurgitation. and chest pain; each scored 0 to 3) and mean lower oesophageal sphincter pressure were assessed after therapy at 1 month, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months | |

| Notes | No major complications reported ‐ significant bleeding requiring hospitalisation, oesophageal perforation, and aspiration 3 lost to follow up (one from BTX and 2 from PD group) ‐ excluded from analysis |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealed, randomisation occurred after enrolment. Patients blinded to therapy |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and assessors blinded to therapy |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and assessors blinded to therapy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and assessors blinded to therapy |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 3 lost to follow up |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Allescher 2001 | Not a RCT |

| Bansal 1996 | Duplicate ‐ meeting abstract. Full paper later published |

| des Varannes 1999 | Meeting abstract ‐ unable to contact author for more information |

| Gaudric 1996 | Meeting abstract ‐ unable to contact author for more information |

| Jung 2012 | Not a RCT ‐ meeting abstract |

| Linghu 2013 | Meeting abstract ‐ unable to contact author for more information |

| Malekzadeh 2000 | Duplicate ‐ meeting abstract. Full paper later published |

| Muehldorfer 1998 | Duplicate ‐ meeting abstract. Full paper later published |

| Nebendahl 1998 | Meeting abstract ‐ unable to contact author for more information |

| Zhou 2012 | RCT published in Chinese Unable to contact author to obtain more information Key points from abstract:

|

Contributions of authors

Leyden J: protocol development, eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction and analysis, drafting of final review.

Moss A: protocol development, eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction and analysis, drafting of final review.

MacMathuna P: clinical and scientific advice, assessment of eligibility and quality, drafting of final review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Gastroenterology, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland.

External sources

Upper GI and Pancreatic Cochrane Group, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Annese 1996 {published data only}

- Annese V, Basciani M, Perri F, Lombardi G, Frusciante V, Simone P, et al. Controlled trial of botulinum toxin injection versus placebo and pneumatic dilation in achalasia. Gastroenterology 1996;111(6):1418‐24. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bansal 2003 {published data only}

- Bansal R, Nostrant TT, Scheiman JM, Koshy S, Barnett JL, Elta GH, et al. Intrasphincteric botulinum toxin versus pneumatic balloon dilation for treatment of primary achalasia. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2003;36(3):209‐14. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghoshal 2001 {published data only}

- Ghoshal UC, Chaudhuri S, Pal BB, Dhar K, Ray G, Banerjee PK. Randomized controlled trial of intrasphincteric botulinum toxin A injection versus balloon dilatation in treatment of achalasia cardia. Diseases of the Esophagus 2001;14(3‐4):227‐31. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mikaeli 2001 {published data only}

- Mikaeli J, Fazel A, Montazeri G, Yaghoobi M, Malekzadeh R. Randomized controlled trial comparing botulinum toxin injection to pneumatic dilatation for the treatment of achalasia. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2001;15(9):1389‐96. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muehldorfer 1999 {published data only}

- Muehldorfer SM, Schneider TH, Hochberger J, Martus P, Hahn EG, Ell C. Esophageal achalasia: intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin A versus balloon dilation. Endoscopy 1999;31(7):517‐21. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vaezi 1999 {published data only}

- Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, et al. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut 1999;44(2):231‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhu 2009 {published data only}

- Zhu Q, Liu J, Yang C. Clinical study on combined therapy of botulinum toxin injection and small balloon dilation in patients with esophageal achalasia. Digestive Surgery 2009;26:493‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Allescher 2001 {published data only}

- Allescher HD, Storr M, Seige M, Gonzales‐Donoso R, Ott R, Born P, et al. Treatment of achalasia: botulinum toxin injection vs. pneumatic balloon dilation. A prospective study with long‐term follow‐up. Endoscopy 2001;33(12):1007‐17. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bansal 1996 {published data only}

- Bansal R, Koshy S, Scheiman JM, Barnett JL, Nostrant TT. Interim analysis of a randomized trial of Witzel pneumatic dilation vs intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin (Botox) for achalasia. Gastroenterology 1996;110(4):A56. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

des Varannes 1999 {published data only}

- Varannes SB, Lemiere S, Guillemot JF, Ducrotte P, Zerbib F, Rolachon A, et al. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in achalasia: Results of a multicentre controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1999;116(4):G0557. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Gaudric 1996 {published data only}

- Gaudric M, Guimbaud R, Chaussade S, Palazzo L, Quartier G, Samama J, et al. Pneumatic dilatation (PD) versus intrasphincteric botulinum toxin (BT) in the treatment of achalasia: Preliminary results of a controlled study. Gastroenterology 1996;110(4):A667. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Jung 2012 {published data only}

- Jung HE, Lee JS, Kim JO, Hong SJ, Lee TH, Kim HG, et al. The long‐term outcome in patients with primary achalasia according to the balloon dilatation or intrasphincteric botulinum toxin injection. Neurogastroenterology and Motility 2012;24 Suppl 2:97. [Google Scholar]

Linghu 2013 {published data only}

- Linghu E, Li H. Randomized study comparing peroral endoscopic myotomy, botulinum toxin injection and balloon dilation for achalasia: one‐year follow‐up. Program and abstracts of the American College of Gastroenterology 2013 Annual Scientific Meeting; October 11‐16, 2013; San Diego, California. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2013;108:Abstract 28. [Google Scholar]

Malekzadeh 2000 {published data only}

- Malekzadeh R, Milkaeli J, Fazel A, Montazeri G, Yaghoobi M, Khatibian M, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing botulinum toxin injection to pneumatic dilatation for treatment of achalasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2000;51(4):4468. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Muehldorfer 1998 {published data only}

- Muehldorfer SM, Schneider T, Hochberger J, Hahn EG, Ell C. Intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin A versus balloon dilation in patients with achalasia. A randomized prospective comparative trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1998;47(4):199. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Nebendahl 1998 {published data only}

- Nebendahl JC, Brand B, Schrenck T, Matsui U, Thonke F, Bohnacker S, et al. Prospective randomised comparison of dilation (high compliance balloon) vs. botulinum toxin injection (BTX) in esophageal achalasia. Gastroenterology 1998;114(4):G0985. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

Zhou 2012 {published data only}

- Zhou H, Dai Y, Lu L, Luo S, Qian Y, Wan X. Endoscopic water‐filled balloon dilatation and botulinum toxin injection for treatment of achalasia: A comparison of clinical effectiveness. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University 2012;33(9):1000‐6. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Annese 1998

- Annese V, Basciani M, Borrelli O, Leandro G, Simone P, Andriulli A. Intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin is effective in long‐term treatment of esophageal achalasia. Muscle & Nerve 1998;21:1540‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bassotti 1999

- Bassotti G, Annese V. Pharmacological options in achalasia. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1999;13:1391‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cuilliere 1997

- Cuilliere C, Ducrotte P, Zerbib F, et al. Achalasia: outcome of patients treated with intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin. Gut 1997;41:87‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eckardt 1997

- Eckardt VF, Kohne U, Junginger T, Westermeier T. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in achalasia. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 1997;42(3):580‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frantzides 2004

- Frantzides CT, Moore RE, Carlson MA, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: a 10‐year experience. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2004;8(1):18‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Howard 1992

- Howard PJ. Maher L, Pryde A, et al. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edingburgh. Gut 1992;33:1011‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Imperiale 2000

- Imperiale TF, O'Connor JB, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. A cost‐minimization analysis of alternative treatment strategies for achalasia. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000;95(10):2737‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Inoue 2010

- Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy 2010;42:265‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kadakia 2001

- Kadakia SC, Wong RK. Pneumatic balloon dilation for esophageal achalasia. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 2001;11(2):325‐46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Katz 1998

- Katz PO, Gilbert J, Costell D. Pneumatic dilation is effective long‐term treatment for achalasia. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 1998;43:1973‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kolbasnik 1999

- Kolbasnik J, Waterfall WE, Fachnie B, Chen Y, Tougas G. Long‐term efficacy of Botulinum toxin in classical achalasia: a prospective study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 1999;94(12):3434‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mayberry 1987

- Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Variations in the prevalence of achalasia in Great Britain and Ireland: an epidemiological study based on hospital admissions. The Quarterly Journal of Medicine 1987;62:67‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pasricha 1994

- Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendric TR, Kalloo AN. Treatment of achalasia with intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin: a pilot trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 1994;121:590‐1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pasricha 1995

- Pasricha PJ, Ravich WJ, Hendrix TR, Sostre S, Jones B, Kalloo AN. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of achalasia. The New England Journal of Medicine 1995;322:774‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pasricha 2007

- Pasricha PJ, Hawari R, Ahmed I, Chen J, Cotton PB, Hawes RH, et al. Submucosal endoscopic esophageal myotomy: a novel experimental approach for the treatment of achalasia. Endoscopy 2007;39:761‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reynolds 1989

- Reynolds, JC, Parkman, HP. Achalasia. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 1989;18:223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Urbach 2001

- Urbach DR, Hansen PD, Khajanchee YS, Swanstrom LL. A decision analysis of the optimal initial approach to achalasia: laparoscopic Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication, thoracoscopic Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilatation, or botulinum toxin injection. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2001;5(2):192‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vela 2004

- Vela MF, Richter JE, Wachsberger D, Connor J, Rice TW. Complexities of managing achalasia at a tertiary referral center: use of pneumatic dilatation, Heller myotomy, and botulinum toxin injection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2004;99(6):1029‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Von Renteln 2013

- Renteln D, Fuchs KH, Fockens P, Bauerfeind P, Vassiliou MC, Werner YB, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: an international prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology 2013;145(2):309‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wen 2004

- Wen ZH, Gardener E, Wang YP. Nitrates for achalasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002299.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]