Abstract

Background

Vaccination is vital for achieving population immunity to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, but vaccination hesitancy presents a threat to achieving widespread immunity. Vaccine acceptance in chronic potentially immunosuppressed patients is largely unclear, especially in patients with asthma. The aim of this study was to investigate the vaccination experience in people with severe asthma.

Methods

Questionnaires about vaccination beliefs (including the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) scale, a measure of vaccination hesitancy-related beliefs), vaccination side-effects, asthma control and overall safety perceptions following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination were sent to patients with severe asthma in 12 European countries between May and June 2021.

Results

660 participants returned completed questionnaires (87.4% response rate). Of these, 88% stated that they had been, or intended to be, vaccinated, 9.5% were undecided/hesitant and 3% had refused vaccination. Patients who hesitated or refused vaccination had more negative beliefs towards vaccination. Most patients reported mild (48.2%) or no side-effects (43.8%). Patients reporting severe side-effects (5.7%) had more negative beliefs. Most patients (88.8%) reported no change in asthma symptoms after vaccination, while 2.4% reported an improvement, 5.3% a slight deterioration and 1.2% a considerable deterioration. Almost all vaccinated (98%) patients would recommend vaccination to other severe asthma patients.

Conclusions

Uptake of vaccination in patients with severe asthma in Europe was high, with a small minority refusing vaccination. Beliefs predicted vaccination behaviour and side-effects. Vaccination had little impact on asthma control. Our findings in people with severe asthma support the broad message that COVID-19 vaccination is safe and well tolerated.

Tweetable abstract

COVID-19 vaccination rate is high in patients with severe asthma. Half report mild side-effects and <6% severe side-effects. Negative vaccination beliefs predict severe side-effects. No evidence of poorer asthma control post-vaccination. https://bit.ly/46wiGNW

Introduction

Since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic emerged in December 2019, around 769 million cases and more than 6.9 million deaths were reported by week 32 (August) of 2023 [1]. Although population immunity can be achieved through infection, vaccination is a safer means of achieving this objective while reducing the societal and financial burden of COVID-19. Vaccination hesitancy, defined as the “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services” [2], is a major threat to achieving herd immunity without too many casualties. Hesitancy is not a modern phenomenon and was a feature of the first vaccine for smallpox in the 1790s [3]. Vaccination hesitancy is a top global health threat [4], an annual problem for preventing seasonal influenza and has presented challenges in previous pandemics, such as the 2009 H1N1 outbreak [5, 6]. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination hesitancy has become a global health problem [7, 8], with an increasing number of studies revealing decreased vaccine acceptance with a pattern of doubts about vaccine safety and effectiveness, exacerbated by ubiquitous unsubstantiated scientific misinformation [9] and distrust of politicians [10].

Vaccination hesitancy is often related to fears about personal safety. The main concern is the fear of a severe allergic reaction as a side-effect of vaccination contributes to COVID-19 hesitancy among people with allergic diseases [11], even though that risk is extremely low. Concerns may also focus on potential future effects; in COVID-19, these have been increased by a perception that the vaccine was developed more quickly than for previous vaccines and, therefore, may not have been rigorously tested [12]. Ideological concerns around profiteering by pharmaceutical companies and a general preference for natural immunity can also contribute to vaccine hesitancy, including in COVID-19 [6, 13]. A systematic review of 60 worldwide studies conducted from February to December 2020 reported that vaccination acceptance rates varied between 24% and 97% in different populations [8]. A further review and meta-analysis reported a similar range (28–93%) [14]. Overall, vaccination acceptance varies widely. A low vaccination intention was reported in healthcare personnel [15] as well as among vulnerable populations with a potentially decreased immune response, including HIV [16], cancer [17] and rheumatic diseases [18] in whom 38.4%, 28.3% and 35.5%, respectively, showed hesitancy to be vaccinated for one reason or another.

Around 3–10% of patients diagnosed with asthma experience severe disease [19] and these patients not only have many comorbidities [20] but often need treatment with high doses of inhaled steroids or oral corticosteroids [21] and/or biological therapies [22]. In patients with severe asthma, a dominating endotype of immune dysregulation is driven by type 2-high inflammation [23], with up to 80% having an allergic/atopic component. Underlying dysregulation of innate immunity can predispose individuals to viral infections [24]. Although asthma may be an independent risk factor for COVID-19 outcome, due to their comorbidities, severe asthma patients are likely to experience more severe disease and worse longer term outcomes [25–27]. Therefore, understanding or overcoming vaccine hesitancy in the population with severe asthma is particularly important. However, no studies to date have addressed this issue.

The aims of the study were to: 1) determine the proportion and characteristics of people with severe asthma in Europe who report that they have either been or will be vaccinated, are unsure whether to get vaccinated, or have decided not to be vaccinated against COVID-19; 2) examine the relationship between vaccination hesitancy beliefs and vaccination status, the relationship between vaccination hesitancy beliefs and perceived side-effects, and perceived asthma symptom change following vaccination; and 3) identify the extent to which patients who have received COVID-19 vaccination feel safe following vaccination and whether they would recommend vaccination to other patients with severe asthma.

Data were obtained using a survey involving patients with severe asthma from the “Severe Heterogeneous Asthma Research collaboration, Patient-centred” (SHARP) Clinical Research Collaboration. This collaboration is hosted by the European Respiratory Society and engages a network of severe asthma experts and patients from clinical centres across 28 countries to promote Europe-wide, patient-centred severe asthma research [28].

Methods

Design, survey development and patient population

This was a cross-sectional study in which the survey was sent to patients with severe asthma within Europe from 5 May to 30 June 2021. The survey was developed iteratively by severe asthma experts (physicians and scientists), health psychologists and patients. Members of the European Lung Foundation's asthma Patient Advisory Group had a central role, consistent with the international guidelines for patient reporting [29]. Professional translators translated the patient surveys into the native languages of the 12 participating European countries and the translations were checked for medical accuracy by asthma specialists. Physicians were asked to recruit severe asthma patients for the survey as they came into their outpatient clinic to prevent selection bias using online and paper versions of the survey according to individual preference. The online survey was hosted by SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com). Paper versions of the survey were used if online versions were unavailable to patients and results from these were transferred into the SurveyMonkey system by the local research team. All data collection was anonymous. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had physician-diagnosed severe asthma and were under the care of a severe asthma clinic for at least 6 months prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Survey content

The survey consisted of 18 questions about demographics, asthma medication use, experience of COVID-19 infection, vaccination status and if the patient had been vaccinated, type of vaccine received. Those already vaccinated were asked about side-effects, whether they felt safer for being vaccinated and whether they would recommend vaccination to other patients with severe asthma. In addition, all patients were asked to complete the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) scale [30], a questionnaire which yields scores on four subscales representing beliefs that may underlie vaccination hesitancy: mistrust of vaccine benefit, worries about unforeseen future effects, concerns about commercial profiteering and preference for natural immunity. Participants responded to questions on a 5-point scale (1=agree strongly and 5=disagree strongly) and responses were averaged to obtain a score for each subscale. A higher score indicates a higher level of belief. The full survey is shown in the supplementary material.

Ethics

Approval for the study was obtained from the medical ethical board of Amsterdam University Medical Center (W20_463 # 20.512) and the ethical boards of every individual country where there was a requirement for approval for survey-based studies. All patients provided digital or written informed consent for participation in this study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics or proportions of positive (“Yes”) responses were calculated for each question, as appropriate. Patients were grouped according to whether or not they had been, or intended to be, vaccinated and we also examined the extent to which they reported vaccination hesitancy according to scores on the VAX questionnaire. Groups were compared using independent samples t-tests, Pearson's Chi-squared or ANOVA with post-hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. p-values ≤0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

In total, 798 surveys were sent through the SHARP network in 12 European countries and 697 patients were recruited, giving a response rate of 87.34%. 37 surveys were incomplete and were removed from the sample, leaving 660 for analysis (table 1). As the number of patients recruited from each country varied largely, no statistical comparisons between countries were possible. Vaccination rates for each country are presented in supplementary table S1. Thus we chose to address the whole population as one European population. The majority of patients were female (65%), over one-fifth (22%) were on daily oral corticosteroids and more than half (64%) were receiving biological therapy for their asthma. Most (70%) had not had a COVID-19 infection, 12% reported a positive COVID-19 test and only 22 (3%) reported hospitalisation due to COVID-19.

TABLE 1.

Participant details by country: numbers and characteristics of participating patients per country

| Participants | Age, years | Female | Daily prednisolone | Biologics | |

| Belgium | 166 (25) | 59 (21–86) | 95 (57) | 33 (20) | 98 (59) |

| Estonia | 43 (7) | 57 (22–86) | 32 (74) | 11 (26) | 21 (49) |

| France | 1 (0.15) | 53 (53–53) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Greece | 104 (16) | 56 (18–80) | 75 (72) | 18 (17) | 88 (85) |

| Hungary | 73 (11) | 57 (23–84) | 49 (67) | 12 (16) | 47 (47) |

| Latvia | 23 (3) | 59 (42–81) | 16 (70) | 3 (3) | 8 (35) |

| Lithuania | 24 (4) | 54 (31–78) | 17 (71) | 3 (3) | 23 (96) |

| Netherlands | 62 (9) | 54 (25–75) | 35 (82) | 14 (14) | 53 (85) |

| Romania | 11 (2) | 56 (38–77) | 9 (82) | 1 (9) | 10 (91) |

| Russian Federation | 19 (3) | 49 (30–70) | 11 (58) | 3 (16) | 5 (26) |

| Serbia | 92 (14) | 53 (26–76) | 57 (62) | 38 (41) | 45 (49) |

| UK | 42 (6) | 51 (28–73) | 30 (71) | 7 (16.7) | 21 (50) |

| All patients | 660 (100) | 55 (18–86) | 427 (65) | 144 (22) | 420 (64) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (range).

COVID-19 vaccination status

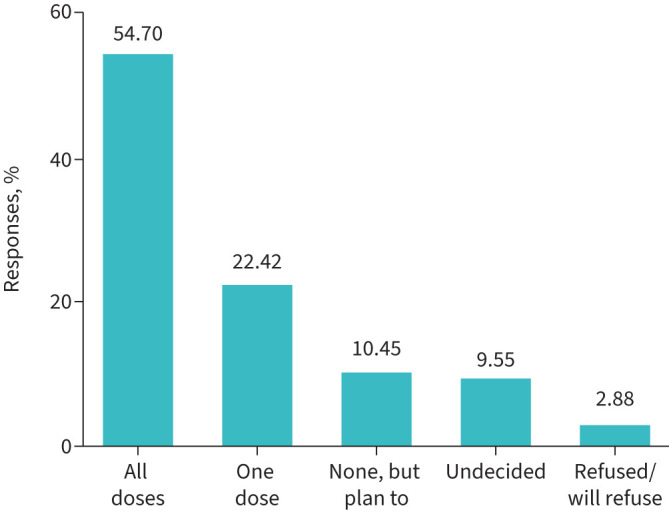

509 out of the 660 patients (77%) had already received at least one dose of vaccine at the time of the study, with a further 10.45% intending to be vaccinated, while 9.55% were still undecided and a smaller proportion (2.88%) had refused vaccination (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination status in patients with severe asthma who completed the survey. Graph showing patients with severe asthma reporting their vaccination status. Data are presented as percentage of the total population who replied to the survey (n=660).

Of the 509 patients who had been vaccinated, 300 (59%) had received an mRNA-based vaccine, with the remainder receiving vector and protein subunit technology vaccines. We grouped patients into three categories according to their reported vaccination status: accepters (patients who are accepting vaccination; vaccinated/will be vaccinated), hesitant (undecided) and refusers (see table 2 for patient characteristics). Patients accepting vaccination were significantly older than those in the other groups (F(2,653)=5.08, p=0.006, η2=0.02). Pearson's Chi-squared indicated that hesitators were most likely to have had a COVID-19 infection (χ2(2)=39.45, p<0.001) and refusers were least likely to be on a biological treatment (χ2(2)=6.19, p=0.05). Refusers were also least likely compared with other categories to use daily prednisolone, although this difference did not reach significance (p=0.23).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of patients according to their reported vaccination status: refusers, hesitant (undecided) and accepters (vaccinated/will be vaccinated)

| Refusers (n=18) | Hesitant (n=63) | Accepters (n=575) | |

| Age, years | 51.28±8.71 | 51.68±13.37 | 56.53±13.14 |

| Female | 61 | 76 | 64 |

| Had COVID-19 | 17 | 41 | 12 |

| Daily prednisolone | 11 | 29 | 22 |

| Biologics for asthma | 44 | 54 | 65 |

Data are presented as mean±sd or %. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Vaccination hesitancy among patients with severe asthma

We then compared the three categories of patients in terms of their vaccination beliefs, as indicated by VAX scores (figure 2). ANOVA showed significant differences in all four beliefs as a function of vaccination status. Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment indicated that for mistrust of vaccine benefit, refusers and hesitators scored similarly (p=0.09) but more highly than accepters (patients who had been vaccinated or planned to be) (p<0.001). For worries about unforeseen future effects, refusers and hesitators scored very similarly (p=0.99) and more highly than accepters (p<0.04). In terms of concerns about commercial profiteering, refusers scored higher than hesitators (p=0.02) who, in turn, reported more concerns than accepters (p<0.001). Finally, the preference for natural immunity was similar in both hesitators and refusers (p=0.19) and higher than accepters (p=0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Vaccination hesitancy between patients with severe asthma (Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) subscale scores) according to their vaccination status. Descriptive statistics for the VAX questionnaire by reported vaccination status for a) mistrust of vaccine benefit, b) worries about unforeseen future effects, c) concerns about commercial profiteering and d) preference for natural immunity. Patients grouped as “accepters” of vaccination (vaccinated/will be vaccinated), “hesitant” (undecided) and “refusers”. Data show results of a 5-point scale (1=agree strongly and 5=disagree strongly) and responses were averaged to obtain a score for each subscale. Significance for paired comparisons with Bonferroni post-hoc tests: *: p<0.05; **: p<0.001.

Perceptions of vaccination safety, asthma symptoms and side-effects

The 509 patients who had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine were presented with a final set of questions about their perception of vaccination side-effects and effects on their asthma symptoms. These items required a “Yes” or “No” response. Most of the patients experienced mild or no side-effects; notably, only 7% reported a need for any treatment for side-effects (table 3). Markedly, the vast majority (89%) did not perceive a change in asthma symptoms following vaccination, with 12 patients (2%) reporting an improvement. 27 patients (5%) perceived that their asthma symptoms got slightly worse without needing any change in treatment, and only six (1%) patients reported that their asthma symptoms got worse and needed a treatment change. Little difference was observed as a function of the type of vaccine received.

TABLE 3.

Perceptions of vaccination side-effects and effects on asthma symptoms following vaccination by patients who had received at least one dose of vaccine (n=509)

| “Yes” responses | Type of vaccine | ||

| mRNA | Other | ||

| Perceived side-effects of vaccination | |||

| Severe side-effects | 29 (5.70) | 13 (2.55) | 16 (4.00) |

| Mild side-effects | 245 (48.16) | 154 (30.26) | 91 (17.88) |

| No side-effects | 223 (43.81) | 128 (25.15) | 95 (18.66) |

| Treatment sought for side-effects | 35 (6.88) | 6 (1.18) | 7 (1.38) |

| Perceived change in asthma symptoms following vaccination | |||

| No change in symptoms | 452 (88.80) | 265 (52.06) | 187 (36.74) |

| Symptoms got better | 12 (2.36) | 6 (1.18) | 6 (1.18) |

| Symptoms slightly worse, no change in treatment needed | 27 (5.30) | 18 (3.54) | 9 (1.77) |

| Symptoms worse, needed a change in treatment | 6 (1.18) | 6 (1.18) | 0 |

Data are presented as n (%). Only 497 surveys had complete answers and were analysed. Percentages represent the proportion of “Yes” responses overall and in terms of the type of vaccine received.

We then considered whether general beliefs about vaccination (and, by implication, vaccination hesitancy) were related to the perception of side-effects (table 4). A comparison of the four VAX subscales regarding the level of reported side-effects (none, mild or severe) revealed significant differences in all but the natural immunity subscale. In each case, there was no significant difference in scores between patients with no or mild side-effects (p=0.25–0.99), but those who reported severe side-effects scored significantly higher on all three subscales (p=0.001 in every case). We observed no significant differences in preference for natural immunity (p>0.50).

TABLE 4.

Vaccination hesitancy-related beliefs (Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) subscale scores) for patients with severe asthma according to their perception of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination side-effects

| Participants | VAX subscale | ||||

| Mistrust of vaccine benefit | Worries about unforeseen future effects | Concerns about commercial profiteering | Preference for natural immunity | ||

| Severe side-effects | 29 | 2.34±0.82 | 4.42±1.18 | 3.14±1.19 | 3.08±1.08 |

| Mild side-effects | 245 | 1.99±0.83 | 3.99±0.98 | 2.42±0.97 | 2.80±1.02 |

| No side-effects | 221 | 1.85±0.80 | 3.82±1.04 | 2.41±1.01 | 2.87±1.11 |

| Results of ANOVA |

F(2,492)=5.04, p=0.01, η2=0.02 |

F(2,492)=5.01, p=0.01, η2=0.02 |

F(2,492)=7.08, p=0.001, η2=0.03 |

F(2,492)=0.99, p=0.37, η2=0.004 |

|

Data are presented as n or mean±sd (VAX questionnaire scores) and results of between-group ANOVA for patients who reported no, mild or severe side-effects following COVID-19 vaccination.

Overall evaluation of vaccination experience

Finally, we were interested in how vaccinated patients felt concerning their safety. Importantly, the vast majority of patients (90%) felt safer following vaccination. Virtually all (98%) would recommend vaccination to other severe asthma patients, irrespective of the vaccine type they received.

Discussion

This survey was conducted in 12 European countries between May and June 2021, about 6 months after COVID-19 vaccines were authorised and at a time when COVID-19 was prevalent, causing significant societal disruption and burden on the healthcare systems. Most severe asthma patients had positive behaviour or intentions to COVID-19 vaccination, with 88% of the participant sample already vaccinated or intending to be. Less than 3% of the respondents said they did not intend to be vaccinated, with the remaining 9% being undecided. Vaccinated patients were slightly older than the other two groups and were less likely to be on a biological treatment. Patients who reported more negative beliefs about vaccination were more likely to be undecided about vaccination or to deny it. Among the vaccinated, those with more negative beliefs were more likely to report severe side-effects. Almost all patients who had received at least one vaccination dose (98%) stated that they would recommend vaccination to other patients with severe asthma.

Vaccination beliefs assessed through the VAX scale showed greater hesitancy for the refuser or undecided groups on all four VAX subscales: mistrust of vaccine benefit, worries about unforeseen future effects, concerns about commercial profiteering and preference for natural immunity. These results are broadly in line with those from general public samples. In terms of the subscales of the VAX, a recently published study reported worries about unforeseen future effects to be the most highly endorsed belief (mean 3.32), followed by a preference for natural immunity (mean 2.44), concerns about commercial profiteering (mean 2.17) and lastly mistrust of vaccine benefit (mean 1.97) [13]. Our survey showed a similar overall pattern.

General public samples often report higher levels of hesitancy than observed in the present study. In a large-scale general population study from the UK, with 32 361 adults, 14% of the sample reported unwillingness to receive a vaccine, with a further 23% unsure/hesitant [31]. Some studies refer to patient groups that have reported high hesitancy rates. Notably, the severe asthmatic population sample in the current study showed more positive attitudes when compared with other chronic or malignant diseases and, generally, when comparing people from outside Europe. In HIV patients surveyed in India between January and February 2021, 38.4% reported being hesitant [16, 17]. Among cancer patients from Tunisia asked about COVID-19 vaccination acceptance between February and May 2021 (close chronologically to the present study), 28.3% were refusers and 21.2% were undecided [17]. Similarly, a survey of 521 adults with chronic disease in Saudi Arabia found COVID-19 vaccine acceptance as low as 52% [32]. Intentions to be vaccinated may change over time. UK hesitancy rates in the general public have been reported to fall from over 25% prior to vaccine development to just 13% once the UK vaccination programme was underway [12]. During the first wave of the pandemic (April 2020), COVID-19 vaccination acceptance was examined in two French high-risk groups: patients above 65 years old and patients with chronic airway disease, asthma or COPD (n=216; mean age 43.8 years). In the second group, most relevant to the present context, vaccination acceptance was 85% [33].

This survey showed that vaccines were well tolerated. Of the 509 participants who had received at least one vaccine dose, the majority reported mild or no side-effects. However, there was evidence of a nocebo effect: people with negative beliefs towards vaccination had more severe side-effects. A minority of patients reported an improvement in asthma symptoms or reported a worsening of symptoms following vaccination. Severe asthma exhibits idiopathic variation in symptoms, so these results may be due to natural variation in asthma control, and the slightly larger number of patients experiencing mild worsening can be explained by a nocebo effect.

Our results are in accordance with an Italian study that evaluated COVID-19 vaccination safety and its effect on asthma control in 253 patients with severe asthma [34]. Less than 20% of patients reported side-effects, and vaccination positively affected asthma symptoms and quality of life. Our present study corroborates these important findings with a larger and more diverse sample, including patients treated with biologics and oral corticosteroids (patients receiving >10 mg prednisolone were excluded from the Italian study). Furthermore, we examined the effects of mRNA and vector/protein subunit technology vaccines, with no differences reported in perceptions of either side-effects or changes in asthma symptoms. A recent meta-analysis of studies involving over 26 million vaccine recipients [34] reported a low prevalence of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-associated anaphylaxis, with nonanaphylactic reactions occurring at a higher rate and being largely self-limited. This was the case in a study of patients with mastocytosis, a group with an increased risk of anaphylaxis where COVID-19 mRNA vaccination was well tolerated [35]. The low number of side-effects reported in our study supports this conclusion. An important finding in our study is that perception of side-effect severity is highest in patients with a general mistrust of vaccines, suggesting that perceptions may be influenced by psychological factors linked to negative expectations. The nocebo effect is recognised as a cause of side-effect reporting for COVID-19 vaccination [36], but we provide evidence for the first time that side-effect reporting is increased with negative beliefs about vaccination.

Finally, this study has shown that 90% of severe asthma patients feel safe following vaccination and 98% would recommend COVID-19 vaccination to other patients with severe asthma. The experience of vaccination in those patients who received the vaccine was positive.

The current recommendation on COVID-19 vaccination from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is that everyone from the age of 5 years should get one dose of an updated vaccine to protect against serious illness from COVID-19 [37]. However, COVID-19 booster vaccination represents a challenge as it rises up to 30% globally [38]. Safety concerns and doubts about safety represent the main reasons [39, 40], which our report shows are unwarranted.

Our study has some limitations. We cannot exclude the possibility that patients with strong vaccination refusal beliefs chose not to respond, thereby introducing an element of bias. Different vaccine availability between countries may have affected the results. In addition, we conducted no clinical evaluations and our data, therefore, rely on self-reported perceptions, with their inherent limitations. However, patients with severe asthma tend to have accurate perceptions of their asthma and can be considered “experts by lived experience”. In addition, people react to their perceptions of events, be they accurate or not, so understanding perceptions can be as important as measuring biomedical data. This survey also does not have the power to compare attitudes towards vaccination between individual countries.

Most of our population was on biologics (64%), which may increase the relationship between health practitioners and patients, as we presume frequent and more close contact, i.e. frequent visits for injections. This relationship could have made it easier for patients to accept vaccinations. However, patients with severe asthma, not on biologics, may have less frequent visits and thus might not have the same acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccination. We address this risk in table 2, where we found that the vaccine refusers were least likely to be on biological treatment. This finding points to the importance of developing regular contact and trust between health professionals and patients in agreement with earlier studies, where lack of trust has been identified among the reasons for vaccination hesitancy [41].

Conclusions and future implications

In our study, only 9% of patients with severe asthma remained undecided about the COVID-19 vaccine. This hesitant minority is important as they are still potentially persuadable. With this study, we provide evidence that might be able to persuade that hesitant minority. First, COVID-19 vaccines are medically safe for people with severe asthma, with no evidence of adverse asthma-related side-effects. Second, people with severe asthma feel safe after having vaccinations. Finally, 98% of patients who had received vaccination would recommend it to other asthma patients, sending a powerful message to patients with asthma and other chronic immune-related diseases who are hesitant about getting vaccinated. This message is valuable for convincing asthma patients and patients with other immune-related diseases, as well as other patients and healthy individuals, to receive a booster vaccine for COVID-19 [37] and overall our preparation for future pandemics [42].

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Table S1 00590-2023.SUPPLEMENT (202.6KB, pdf)

Supplementary material 00590-2023.SUPPLEMENT2 (128.4KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The SHARP Clinical Research Collaboration wishes to acknowledge the help and expertise of the following individuals and groups without whom the study would not have been possible: Courtney Coleman (European Lung Foundation), Emmanuelle Berret (European Respiratory Society), Natalya Isayevska Natalya (Ida-Viru Keskhaigla), Renata Melnikova (Medicum Estonia), Petra Hirmann (Medisch Centrum Leeuwarden), Marina Peredelskaya (Russian Medical Academy of Continuous Professional Education of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation) and Sabina Skrgat (Pulmonary Department, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Medical Faculty, University of Ljubljana).

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Ethics statement: Approval for the study was obtained from the medical ethical board of the Amsterdam University Medical Center (W20_463 # 20.512) and the ethical boards of every individual country where there was a requirement for approval for survey-based studies. All patients provided digital or written informed consent for participation in this study.

Conflict of interest: A. Bossios reports support from Novartis for attending meetings, outside the submitted work; participation on a data safety monitoring or advisory board for AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Teva and Sanofi, outside the submitted work; and is a member of the Steering Committee of SHARP, Secretary of Assembly 5 (Airway Diseases, Asthma, COPD and Chronic Cough) of the European Respiratory Society and Vice-chair of the Nordic Severe Asthma Network, outside the submitted work. K. Katsoulis reports payment or honoraria for lectures presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from GSK, Novartis and AstraZeneca; and support received from Menarini and Novartis for attending meetings and/or travel, outside the submitted work. K. Kostikas reports grants or contracts from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Innovis, ELPEN, GSK, Menarini, Novartis and NuvoAir, outside the submitted work; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, ELPEN, GSK, Menarini, Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme, outside the submitted work; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, ELPEN, GSK, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme and WebMD, outside the submitted work; and is a member of the GOLD Assembly, disclosures made outside the submitted work. N. Rovina reports receiving honoraria for lectures and presentations from Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Menarini, Gilead and Baxter, outside the submitted work. K. Bieksienė reports receiving lecture honoraria from Berlin-Chemie, AstraZeneca and Norameda, outside the submitted work. A. ten Brinke reports grants from Teva and GSK, outside the submitted work; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme and Teva, outside the submitted work; and payment or honoraria for lectures received from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi-Genzyme and Teva, outside the submitted work; and is Chair of the Dutch severe asthma registry RAPSODI, outside the submitted work, and ERS SHARP CRC national lead for the Netherlands. R. Chaudhuri reports grants or contracts from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work; payment of honoraria for lectures from GSK, AstraZeneca, Teva, Chiesi, Sanofi and Novartis, outside the submitted work; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Chiesi, Sanofi and GSK, outside the submitted work; and participation in advisory board meetings for GSK, AstraZeneca, Teva, Chiesi and Novartis, outside the submitted work. H. Rupani reports grant funding from GSK and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work; payments for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis and Teva, outside the submitted work; and is an associate editor of this journal. P. Howarth is an employee of GSK, disclosure made outside the submitted work. C. Porsbjerg reports grants or contracts from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Chiesi and ALK, outside the submitted work; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Chiesi and ALK, outside the submitted work; personal honoraria from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Chiesi and ALK, outside the submitted work; participation on a data safety monitoring or advisory board for AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Chiesi and ALK, outside the submitted work. E.H. Bel reports research grants from GSK and Teva, outside the submitted work; and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sterna Biologicals, Chiesi Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi/Regeneron and Teva, outside the submitted work. M.E. Hyland reports grants or contracts from Teva outside the submitted work; and payment received from GSK for writing educational material for respiratory nurses, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Support statement: The SHARP CRC has been supported by financial and other contributions from the following consortium partners: European Respiratory Society, GlaxoSmithKline Research and Development Limited, Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA, Novartis Pharma AG, Sanofi-Genzyme Corporation and Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2023. https://covid19.who.int Date last accessed: 10 August 2023.

- 2.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015; 33: 4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern AM, Markel H. The history of vaccines and immunization: familiar patterns, new challenges. Health Aff 2005; 24: 611–621. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. 2019. www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 Date last accessed: 14 October 2023.

- 5.Bangerter A, Krings F, Mouton A, et al. . Longitudinal investigation of public trust in institutions relative to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Switzerland. PLoS One 2012; 7: e49806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor S. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease. Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021; 9: 160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiysonge CS, Ndwandwe D, Ryan J, et al. . Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022; 18: 1–3. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1893062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinzierl MA, Harabagiu SM. Automatic detection of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation with graph link prediction. J Biomed Inform 2021; 124: 103955. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo H, Qu H, Basu R, et al. . Willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine and reasons for hesitancy among Medicare beneficiaries: results from a national survey. J Public Health Manag Pract 2022; 28: 70–76. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams EM, Shaker M, Sinha I, et al. . COVID-19 vaccines: addressing hesitancy in young people with allergies. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 1090–1092. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00370-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacon AM, Taylor S. Vaccination hesitancy and conspiracy beliefs in the UK during the SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Int J Behav Med 2021; 29: 448–455. doi: 10.1007/s12529-021-10029-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslin G, Dempster M, Berry E, et al. . COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy survey in Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland: applying the theory of planned behaviour. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0259381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Amer R, Maneze D, Everett B, et al. . COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2022; 31: 62–86. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas N, Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, et al. . The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. J Community Health 2021; 46: 1244–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekstrand ML, Heylen E, Gandhi M, et al. . COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLWH in South India: implications for vaccination campaigns. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 88: 421–425. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mejri N, Berrazega Y, Ouertani E, et al. . Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: another challenge in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2022; 30: 289–293. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06419-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guaracha-Basáñez G, Contreras-Yáñez I, Álvarez-Hernández E, et al. . COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Mexican outpatients with rheumatic diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021; 17: 5038–5047. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2003649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen S, von Bülow A, Sandin P, et al. . Prevalence and management of severe asthma in the Nordic countries – findings from the NORDSTAR cohort. ERJ Open Res 2023; 9: 00687-02022. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00687-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porsbjerg C, Menzies-Gow A. Co-morbidities in severe asthma: clinical impact and management. Respirology 2017; 22: 651–661. doi: 10.1111/resp.13026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eger K, Amelink M, Hashimoto S, et al. . Overuse of oral corticosteroids, underuse of inhaled corticosteroids, and implications for biologic therapy in asthma. Respiration 2021; 101: 116–121. doi: 10.1159/000518514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eyerich S, Metz M, Bossios A, et al. . New biological treatments for asthma and skin allergies. Allergy 2020; 75: 546–560. doi: 10.1111/all.14027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bossios A. Inflammatory T2 biomarkers in severe asthma patients: the first step to precision medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 2689–2690. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wark PA, Johnston SL, Bucchieri F, et al. . Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med 2005; 201: 937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YJ, Park JY, Lee HS, et al. . Effect of asthma and asthma medication on the prognosis of patients with COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2002226. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02226-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izquierdo JL, Almonacid C, González Y, et al. . The impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2003142. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03142-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selberg S, Karlsson Sundbaum J, Konradsen JR, et al. . Multiple manifestations of uncontrolled asthma increase the risk of severe COVID-19. Respir Med 2023; 216: 107308. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Bragt J, Adcock IM, Bel EHD, et al. . Characteristics and treatment regimens across ERS SHARP severe asthma registries. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901163. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01163-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. . GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017; 358: j3453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin LR, Petrie KJ. Understanding the dimensions of anti-vaccination attitudes: the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) scale. Ann Behav Med 2017; 51: 652–660. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9888-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021; 1: 100012. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Hanawi MK, Ahmad K, Haque R, et al. . Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination among adults with chronic diseases in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 2021; 14: 1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams L, Gallant AJ, Rasmussen S, et al. . Towards intervention development to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among those at high risk: outlining evidence-based and theoretically informed future intervention content. Br J Health Psychol 2020; 25: 1039–1054. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alhumaid S, Al Mutair A, Al Alawi Z, et al. . Anaphylactic and nonanaphylactic reactions to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2021; 17: 109. doi: 10.1186/s13223-021-00613-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazarinis N, Bossios A, Gülen T. COVID-19 vaccination in the setting of mastocytosis – Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine is safe and well tolerated. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 1377–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amanzio M, Mitsikostas DD, Giovannelli F, et al. . Adverse events of active and placebo groups in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine randomized trials: a systematic review. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 12: 100253. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Stay Up to Date with COVID-19 Vaccines. 2023. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html Date last accessed: 22 September 2023.

- 38.Limbu YB, Huhmann BA. Why some people are hesitant to receive COVID-19 boosters: a systematic review. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023; 8: 159. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed8030159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noh Y, Kim JH, Yoon D, et al. . Predictors of COVID-19 booster vaccine hesitancy among fully vaccinated adults in Korea: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Health 2022; 44: e2022061. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2022061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah A, Coiado OC. COVID-19 vaccine and booster hesitation around the world: a literature review. Front Med 2022; 9: 1054557. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1054557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viskupič F, Wiltse DL, Meyer BA. Trust in physicians and trust in government predict COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Soc Sci Q 2022; 103: 509–520. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alakija A. Leveraging lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to strengthen low-income and middle-income country preparedness for future global health threats. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23: e310–e317. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00279-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Table S1 00590-2023.SUPPLEMENT (202.6KB, pdf)

Supplementary material 00590-2023.SUPPLEMENT2 (128.4KB, pdf)