Abstract

The catecholamines dopamine and norepinephrine are key central neurotransmitters that participate in many neurobehavioral processes and disease states. Norepinephrine is also the main neurotransmitter mediating regulation of the circulation by the sympathetic nervous system. Several neurodegenerative disorders feature catecholamine deficiency. The most common is Parkinson’s disease (PD), in which putamen dopamine content is drastically reduced. PD also entails severely decreased myocardial norepinephrine content, a feature that characterizes two other Lewy body diseases—pure autonomic failure and dementia with Lewy bodies. It is widely presumed that tissue catecholamine depletion in these conditions results directly from loss of catecholaminergic neurons; however, as highlighted in this review, there are also important functional abnormalities in extant residual catecholaminergic neurons. We refer to this as the “sick-but-not-dead” phenomenon. The malfunctions include diminished dopamine biosynthesis via tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase (LAAAD), inefficient vesicular sequestration of cytoplasmic catecholamines, and attenuated neuronal reuptake via cell membrane catecholamine transporters. A unifying explanation for catecholaminergic neurodegeneration is autotoxicity exerted by 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), an obligate intermediate in cytoplasmic dopamine metabolism. In PD, putamen DOPAL is built up with respect to dopamine, associated with a vesicular storage defect and decreased aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Probably via spontaneous oxidation, DOPAL potently oligomerizes and forms quinone-protein adducts with (“quinonizes”) α-synuclein (AS), a major constituent in Lewy bodies, and DOPAL-induced AS oligomers impede vesicular storage. DOPAL also quinonizes numerous intracellular proteins and inhibits enzymatic activities of TH and LAAAD. Treatments targeting DOPAL formation and oxidation therefore might rescue sick-but-not-dead catecholaminergic neurons in Lewy body diseases.

Keywords: dopamine, norepinephrine, dopal, autonomic, synuclein, sympathetic nervous system

Dopamine and norepinephrine (NE) are catecholamines that play important roles as central neurotransmitters in movement, learning, memory, reward, attention, and distress.1–3 Outside the brain, NE is the major neurotransmitter of the sympathetic nervous system in circulatory regulation.4,5

Catecholamine Depletion in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Catecholamine depletion characterizes a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, the most common of which is Parkinson’s disease (PD). Other such conditions involving catecholamine deficiency in affected regions include pure autonomic failure (PAF),6,7 multiple system atrophy (MSA),8–10 and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).11

PD features profoundly decreased dopamine content in the striatum12,13—especially in the putamen.14 Frontal cortex normally contains relatively low dopamine concentrations that do not seem to be decreased in PD.15 Contents of NE in most brain areas are also decreased,16–18 including in frontal cortex.15 In the locus ceruleus, the main source of NE in the brain, NE deficiency has been reported specifically in PD with dementia.19 Since frontal cortical noradrenergic innervation is derived from the locus ceruleus, there seems to be greater loss of NE at the level of the terminals than at the level of the neuronal cell bodies. It has been reported that in PD there is even greater loss of neurons in the locus ceruleus than in the substantia nigra.20

Outside the brain, in PD there is very prominent loss of NE in the left ventricular myocardium.21–23 The extent of decrease in PD—90 to 99%—is similar to that of putamen dopamine. Several in vivo neuroimaging studies have indicated that in PD noradrenergic deficiency is cardioselective24–27; however, postmortem NE tissue contents in extracardiac regions in PD have not yet been reported.

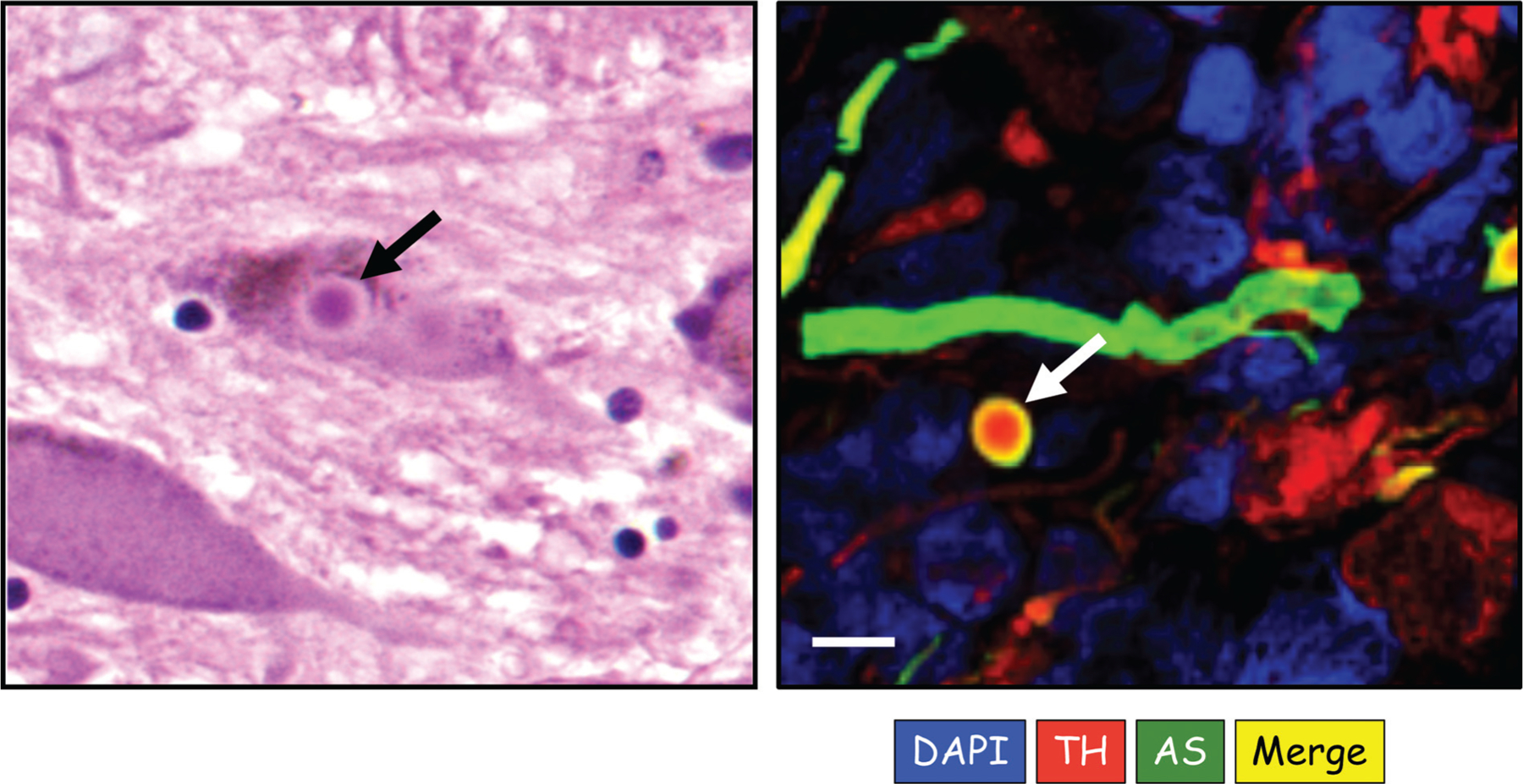

PD is characterized pathologically by Lewy bodies, which are intraneuronal cytoplasmic inclusions that have particular light microscopic characteristics upon hematoxylin/eosin staining (►Fig. 1, left panel). Lewy bodies contain deposits of the protein α-synuclein (AS)28 as well as of two proteins intimately involved with catecholaminergic functions—tyro-sine hydroxylase (TH)29,30 (►Fig. 1, right panel), which is the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis, and the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2),31 which is required for vesicular uptake of cytoplasmic catecholamines.

Fig. 1.

Lewy bodies. The left panel shows an intracellular Lewy body stained with hematoxylin/eosin from a patient with pure autonomic failure (PAF). The right panel shows an immunofluorescence microscopic image of an extracellular Lewy body and nearby Lewy neurite from sympathetic ganglion tissue of a patient with Parkinson’s disease and orthostatic hypotension. In the right panel, red corresponds to immunoreactive tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), green α-synuclein (AS), blue DAPI to stain nuclei, and yellow TH-AS colocalization. Note TH in the center of the Lewy body and colocalized TH and AS in the halo. The Lewy neurite contains AS. Scale bar 10 μm. (Image courtesy of R. Isonaka.)

Two other Lewy body diseases related to PD are PAF and DLB. All PAF patients have neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH) without clinical signs or symptoms of central neurodegeneration.32,33 PAF is a rare disease, and so the literature on Lewy bodies in PAF is sparse; however, all postmortem studies of PAF have noted Lewy bodies in the brain or sympathetic ganglion tissue.34–38 PAF patients have AS deposition in sympathetic ganglion tissue29,36,39 and sympathetic nerves.40–43 Moreover, PAF can evolve into PD or DLB.44 It is therefore reasonable to conceptualize that PAF is by definition a form of Lewy body disease. If so, then a patient with nOH and noradrenergic deficiency but lacking demonstrable Lewy bodies or AS in sympathetic nerves would not be considered to have PAF.45,46

DLB patients also have AS deposition in Lewy bodies,47 including in sympathetic ganglion tissue29,48 and cutaneous sympathetic nerves.43,48 The frequency of nOH in DLB seems to be intermediate between PAF and PD.49

As in PD, in MSA there is drastic putamen dopamine deficiency.9 Catecholamine levels in other brain regions have not been reported; however, counts of catecholaminergic neurons are decreased in the A1 and C1 regions of the ventrolateral medulla.50 Cerebrospinal fluid levels of homovanillic acid, the end-product of dopamine metabolism, are decreased in MSA,8 as are levels of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, the main neuronal metabolite of NE.51 Outside the brain, there is no evidence for generalized catecholamine deficiency in MSA,6,7,52 although a minority of MSA patients do have neuroimaging or postmortem neuropathologic evidence of loss of cardiac noradrenergic nerves.53–55

Functional Abnormalities in Residual Catecholaminergic Neurons: The “Sick-but-not-Dead” Phenomenon

In PD, the extent of loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons56 or striatal dopaminergic innervation as indicated by immunoreactive TH57 is far less than the extent of decrease in putamen dopamine content.14 How can there be a greater loss of a neurotransmitter than of the nerves that contain the neurotransmitter?

A potential resolution of this apparent paradox is decreased neurotransmitter synthesis, vesicular storage, or recycling in the residual terminals. Let us presume that the innervation is 20% of control, whereas the dopamine content is 4% of control. If the ability to sequester dopamine in vesicles in the residual terminals were 20% of control, then the tissue content of the neurotransmitter would be 20%× 20%=4% of control.

We have introduced the term “sick-but-not-dead” to refer to the occurrence of functional abnormalities in extant residual catecholaminergic neurons in diseases involving catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.23 The following discussion describes examples of the sick-but-not-dead phenomenon in catecholaminergic neurons in the brain or heart in Lewy body diseases.

There is growing evidence for a vesicular storage defect in dopaminergic neurons in PD.58–62 Decreased VMAT2 activity can precede loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons,63 and mice with genetically determined low VMAT2 activity have aging-related denervation of central dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons.64,65 Meanwhile, animals with increased VMAT2 activity are relatively resistant to manipulations that produce catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.64–69

Several in vivo and postmortem studies have indicated an analogous vesicular storage defect in residual myocardial sympathetic noradrenergic neurons in Lewy body diseases.21–23,59,61

Another functional abnormality contributing to putamen dopamine deficiency in PD is decreased dopamine biosynthesis from 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) via L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase (LAAAD).9,70 Decreased LAAAD activity has also recently been reported in residual cardiac sympathetic nerves in PD.23

A third functional abnormality in putamen dopaminergic terminals is decreased activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). ALDH is gaining increasing attention as a factor relevant to PD pathogenesis.71–74 Postmortem neurochemical studies have reported decreased ALDH activity, based on low 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC)/3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) concentration ratios in putamen tissue from patients with PD or MSA.75,76

ALDH deficiency promotes DOPAL accumulation,77,78 because ALDH inhibition decreases the metabolism of cytoplasmic DOPAL. Animals with genetically determined low ALDH activity and DOPAL buildup have aging-related abnormalities resembling those in PD.77 Meanwhile, animals with increased ALDH activity are relatively resistant to manipulations that produce dopaminergic neurodegeneration.79 ALDH1A1, a marker of nigral dopaminergic neurons, seems to be protective.80 Overexpression of ALDH1A1 reduces oxidation-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells.81 The metabolic stressor and pesticide rotenone, which produces an adult rat model of PD,82–84 decreases ALDH activity indirectly by blocking mitochondrial complex 1; this decreases generation of NAD+, a required cofactor for ALDH. As one would predict from this effect, rotenone evokes DOPAL accumulation.85,86 DOPAL is not normally detected in myocardial tissue (unpublished observations).

Several clinical pathophysiologic states are associated with myocardial NE depletion. These include heart failure,87–92 myocardial infarction,93,94 long-term diabetes,95 and Lewy body diseases.21,22,96

As for putamen dopamine, one might presume that myocardial NE depletion in Lewy body diseases reflects denervation; however, studies using immunoreactive TH as a marker of myocardial noradrenergic innervation have noted about a 75% average decrease in PD,97–102 whereas the extent of decrease in tissue NE content is in the range of 90 to 99%.21–23 The greater magnitude of NE depletion than of loss of sympathetic noradrenergic innervation indicates the sick-but-not-dead phenomenon in residual myocardial noradrenergic nerves in Lewy body diseases.

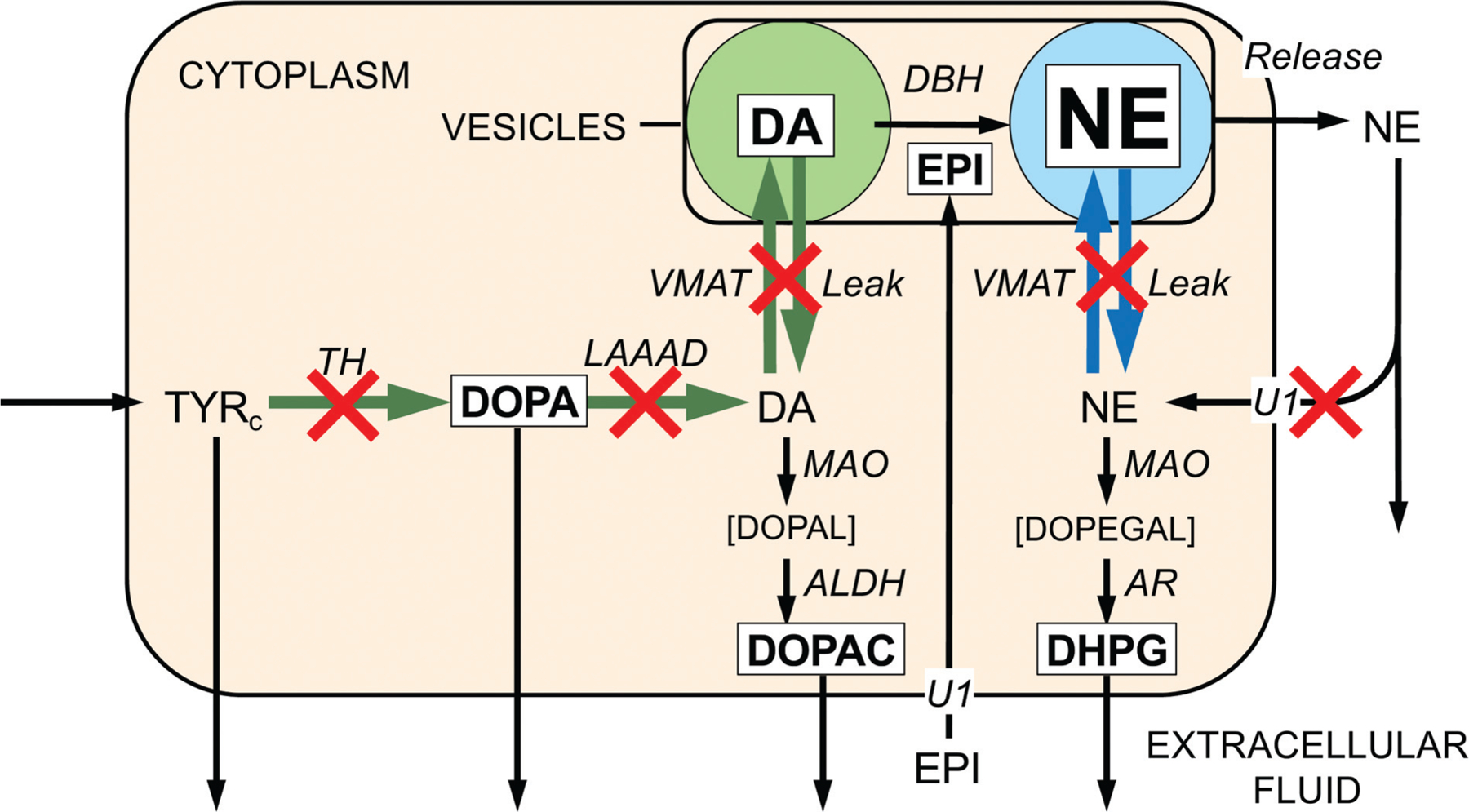

Numerous mechanisms might determine denervation-independent decreased NE stores in sympathetic nerves (►Fig. 2). These include decreased vesicular uptake of cytoplasmic catecholamines via the VMAT261; increased vesicular permeability103; decreased axonal transport of vesicles or vesicle-associated proteins104; decreased enzymatic activities of TH,105 LAAAD,106 or vesicular dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH)107; increased exocytotic release of vesicular NE108; and decreased neuronal NE recycling via the uptake-1 process mediated by the cell membrane NE transporter (NET).109

Fig. 2.

Sites of functional abnormalities of catecholamine synthesis, storage, release, recycling, and metabolism in myocardial sympathetic nerves in Lewy body diseases. Reactions are in italics and amounts of reactants in plain text. Font sizes correspond roughly to amounts of reactants. Green arrows indicate dopamine (DA) synthesis and blue arrows norepinephrine (NE) vesicular uptake and leakage. Red X marks placed to indicate sites of abnormalities in residual sympathetic nerves in Lewy body diseases. Application of a kinetic model to previously published data revealed three types of abnormal intraneuronal processes in the Lewy body disease group—(a) attenuated catecholamine biosynthesis via tyrosine hydroxylase and L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase, (b) impaired vesicular sequestration of cytoplasmic catecholamines, reflecting the balance of vesicular uptake versus leakage, and (c) inefficient recycling of released NE by reuptake through the cell membrane NE transporter. ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; AR, aldehyde/aldose reductase; Cys-DA, 5-S-cysteinylDA; Cys-DOPA, 5-S-cysteinyl DOPA; DAc, cytoplasmic DA; DBH, dopamine-β-hydroxylase; DHPG, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol; DOPAc, cytoplasmic DOPA; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; DOPEGAL, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde; DOPAL, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde; DOPET, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol; EPI, epinephrine; LAAAD, L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NEc, cytoplasmic NE; NEe, NE in the extracellular fluid; NESO, NE entering the cardiac venous drainage; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; TYR, tyrosine; TYRc, cytoplasmic TYR; U1 = Uptake-1, neuronal uptake; U2 = Uptake-2, extraneuronal uptake; VMAT, vesicular monoamine transporter.23

Until recently there was little information about which of these processes are affected in clinical disease states. Since NE is synthesized withinvesicles by DBHacting on dopamine after vesicular uptake, it is likely that a previously reported finding of an increased tissue dopamine/NE ratio in preterminal idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy reflected decreased vesicular uptake rather than the inferred decrease in DBH enzyme activity.88

We recently used a computational modeling approach to assess comprehensively all the known pathways of NE synthesis, storage, release, reuptake, and metabolism in cardiac sympathetic nerves in Lewy body diseases.23 Application of a novel kinetic model identified a pattern of dysfunctional steps contributing to NE deficiency. The model identified low rate constants for three types of processes in the Lewy body group—catecholamine biosynthesis via TH and LAAAD, vesicular storage of dopamine and NE, and neuronal NE reuptake via the cell membrane NET (►Fig. 2). Postmortem catechols and catechol ratios confirmed this triad of model-predicted functional abnormalities. Therefore, denervation-independent impairments of neurotransmitter biosynthesis, vesicular sequestration, and NE recycling contribute to the myocardial NE deficiency attending Lewy body diseases.

Catecholamine Autotoxicity and the Catecholaldehyde Hypothesis

Is there a single common cause for the pattern of functional abnormalities in catecholaminergic neurons in Lewy body diseases? Oxidative stress or decreased mitochondrial energy generation would seem likely culprits110,111; however, for LAAAD to catalyze dopamine synthesis from DOPA requires neither oxygen nor energy, yet LAAAD activity is substantially decreased. Widespread oxidative stress or deficient mitochondrial energy generation would not account easily for the syndromic nature of Lewy body diseases, nor the relatively selective, profound catecholamine deficiencies found in the putamen and heart compared with other regions receiving catecholaminergic innervation.

The catecholamine autotoxicity theory imputes pathologic interactions between catecholamine oxidation products and intracellular proteins in the pathogenesis of diseases involving catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.112

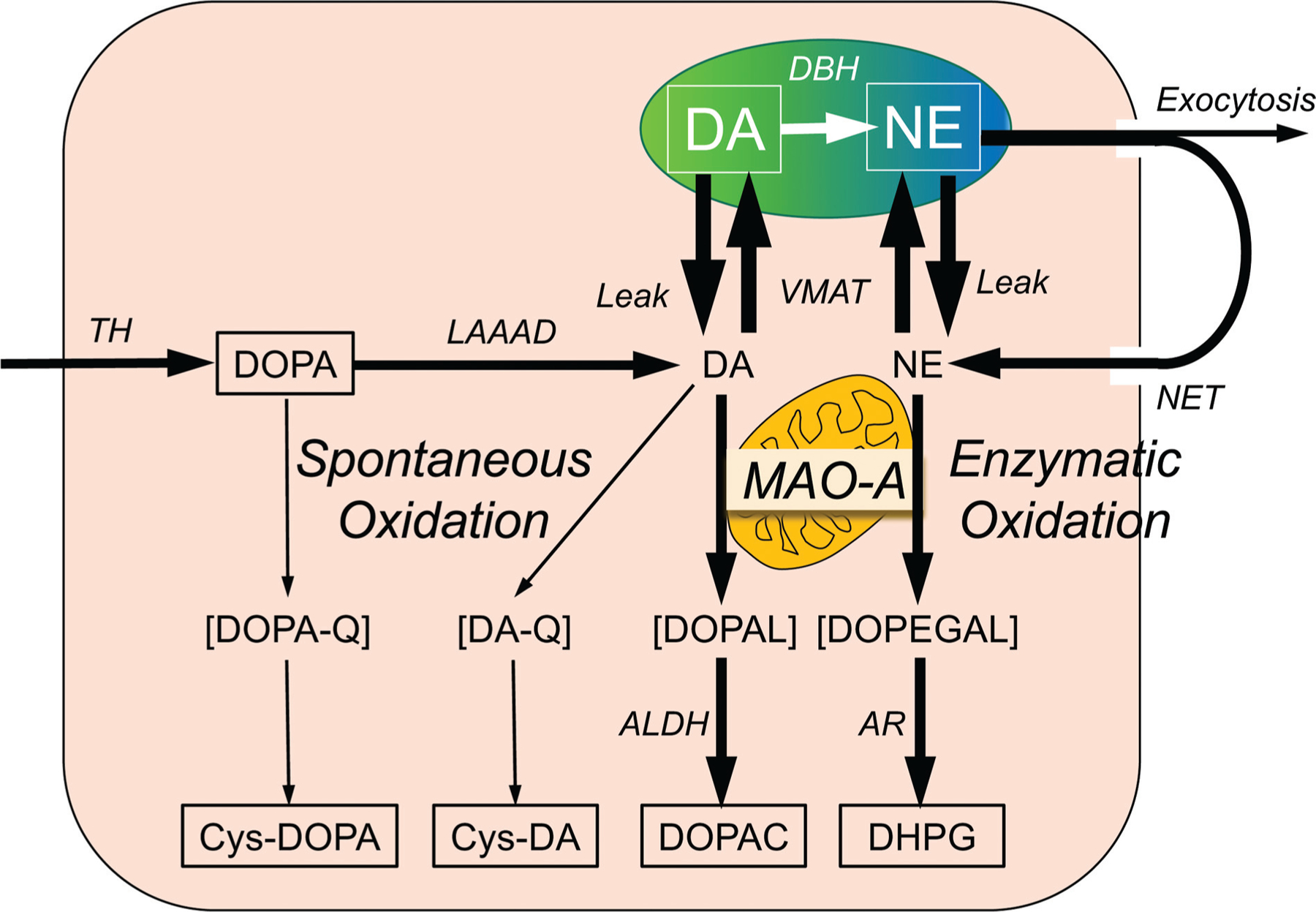

Many studies have implicated dopamine as an autotoxin. Most have focused on its spontaneous oxidation to dopamine-quinone and then a variety of distal oxidation products113–139 (►Fig. 3). Some of these are known to be neurotoxic, such as aminochrome,120,140,141 5-S-cysteinyldopamine,139,142 and isoquinolines.143,144 These compounds seem to have in common that they evoke mitochondrial dysfunction.127

Fig. 3.

Overview of the sources and fate of intraneuronal catecholamines, with emphasis on spontaneous and enzymatic oxidation of catechols. Dopamine (DA) is synthesized in the neuronal cytoplasmic via tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) acting on tyrosine to form 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) and then L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase (LAAAD) acting on DOPA. Most of cytoplasmic DA is taken up into vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT). Dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) in the vesicles catalyzes the conversion of DA to norepinephrine (NE). DA and NE in the cytoplasm are subject to oxidative deamination catalyzed by monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A) in the outer mitochondrial membrane to form 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde (DOPEGAL). DOPAL is converted to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) via aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), and DOPEGAL is converted to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) via aldehyde/aldose reductase (AR). Most of vesicular NE released by exocytosis is taken up into the cytoplasm via the cell membrane NE transporter (NET). DOPA can undergo spontaneous oxidation to DOPA-quinone (DOPA-Q), resulting in formation of 5-S-cysteinylDOPA (Cys-DOPA), and DA can undergo spontaneous oxidation to DA-quinone (DA-Q), resulting in formation of 5-S-cysteinylDA (Cys-DA).

An almost completely independent line of research has centered on DOPAL. DOPAL, an obligate intermediate in neuronal DA metabolism, is formed from the enzymatic oxidation of cytoplasmic dopamine by MAO.

DOPAL is toxic both in vitro and in vivo145–148 and is the centerpiece of the catecholaldehyde hypothesis. According to the catecholaldehyde hypothesis, DOPAL buildup causes or contributes to the death of catecholaminergic neurons in neurodegenerative diseases such as PD.148 DOPAL is far more toxic in vivo than is dopamine or its oxidized, reduced, or methylated metabolites.149 At concentrations as low as 100 ng, injected DOPAL destroys substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons.149 In energetically compromised mitochondria from PC12 cells, DOPAL induces the permeability transition pore, a harbinger of cell death.150

The pesticide rotenone, by inhibiting mitochondrial complex 1, decreases formation of NAD+, which is required for ALDH activity. Rotenone therefore builds up DOPAL.86 Some of rotenone-induced cytotoxicity in catecholamine-producing cells depends on DOPAL.151 Fungicides inhibit ALDH,78,152 and thefungicide benomyl blocks ALDHand builds up DOPAL.78

The enzymatic oxidative deamination of cytoplasmic dopamine by MAO results in concurrent equimolar formation of hydrogen peroxide and DOPAL. Reaction of DOPAL with hydrogen peroxide yields highly toxic hydroxyl radicals,153 and DOPAL oxidation results in formation of superoxide.154

When DOPAL is incubated with rat brain homogenates, the aldehyde disappears, independent of metabolic enzymes.155 This finding raises the possibility that DOPAL reacts with proteins, a suspicion that recently has been confirmed amply.156 DOPAL forms covalent quinone adducts with (“quinonizes”) many PD-related proteins, including TH, LAAAD, VMAT2, glucocerebrosidase, and AS.156 Quinonization may interfere with the functions of these proteins and thereby with numerous intracellular processes. Thus, DOPAL inhibits activities of TH,105,157 LAAAD,156 and ALDH,158 although whether these effects depend on quinonization is incompletely understood.

Interactions of Dopamine Oxidation Products with α-Synuclein

The catecholamine autotoxicity theory imputes pathologic interactions between catecholamine oxidation products and intracellular proteins in the pathogenesis of diseases involving catecholaminergic neurodegeneration.112

Oxidized dopamine can interact with AS117 and promote the formation of AS oligomers.121,129,159 Moreover, aminochrome and 5,6-dihydroxyindole, which are products of dopamine oxidation, can oligomerize AS.160–162 Most investigations on this topic have not considered the possibility that dopamine-dependent AS oligomerization depends on production of DOPAL from dopamine.117,121,129

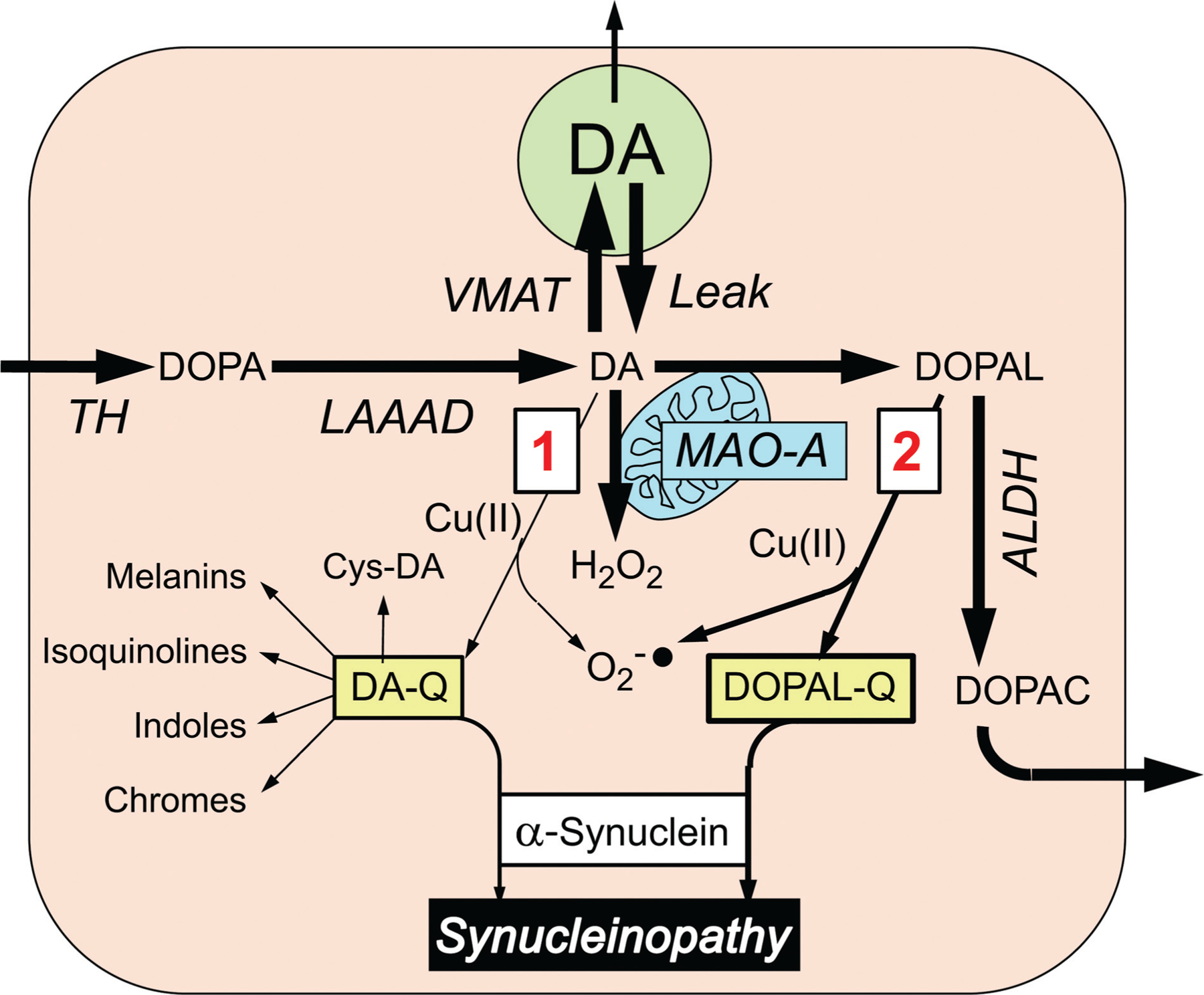

DOPAL potently reacts with AS,156,163 converting the protein to oligomeric forms163–167 that potentially are toxic.168–170 DOPAL-induced AS oligomers impede vesicular functions.103 Divalent metal cations—especially Cu(II)—augment DOPAL-induced AS oligomerization.171 Moreover, DOPAL quinonizes AS, probably following spontaneous oxidation of DOPAL to DOPAL-quinone.156 DOPAL also enhances AS-induced inhibitory effects on tyrosine receptor kinase B, a receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor.172 Meanwhile, AS itself inhibits LAAAD.106

The literature on dopamine oxidation and synucleinopathy has generally overlooked DOPAL,121,137,138,173–176 and the literature on DOPAL and synucleinopathy has generally over-looked dopamine and its spontaneous oxidation to dopamine-quinone.156,163,164,177 In the few studies where DOPAL and dopamine have been compared directly in terms of oligomerizing AS, DOPAL has been found to be more potent.156,163,171

We recently compared DOPAL and dopamine in terms of (1) AS oligomerization and quinonization in test tube experiments; (2) enhancing effects of Cu(II)171,178 and mitigating effects of antioxidation with N-acetylcysteine (NAC)134,156,179,180; and (3) quinonization of intracellular proteins in cultured cells.134,156 We found that DOPAL is far more potent than dopamine in both oligomerizing and quinonizing AS.181 Dopamine oxidation evoked by Cu(II) or tyrosinase does not quinonize AS. In cultured MO3.13 human oligodendrocytes, DOPAL, but not dopamine, results in the formation of numerous intracellular quinoproteins that can be visualized by near-infrared microscopy. Therefore, of the two routes by which oxidation of dopamine modifies AS and other proteins (►Fig. 4), that via DOPAL is more prominent.

Fig. 4.

Alternative routes by which dopamine (DA) oxidation may modify α-synuclein. Most of cytoplasmic DA is taken up into vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT), but a minority undergoes oxidation, by two routes (red numbers in boxes). In route 1, DA is oxidized to form DA-quinone (DA-Q), with subsequent interactions with α-synuclein directly or via various further products of DA-Q, including 5-S-cysteinyldopamine (Cys-DA). In route 2, DA is oxidized enzymatically by monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A) in the outer mitochondrial membrane to form 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Cu(II) promotes the oxidation of DA and DOPAL. Formation of DA-Q and DOPAL-Q is associated with generation of superoxide radicals (O2−•). DOPAL is metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to form 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), which exits the cell.

The differences in potencies of DOPAL and dopamine in oligomerizing and quinonizing AS can be explained by their different chemical structures.182 Whereas dopamine has a terminal amine group, DOPAL has a reactive aldehyde group that can bind covalently to lysine residues,180 which are abundant in the AS molecule.103,164,182 Occupation of lysine residues completely prevents DOPAL-induced oligomerization and quinonization of AS.156

A specific mechanism has been proposed relating DOPAL oxidation to AS oligomerization. Superoxide, which is generated pari passu with the oxidation of DOPAL, propagates a chain reaction oxidation resulting in a dicatechol pyrrole adduct with lysine (dicatechol pyrrole lysine, DCPL).165 The same investigators have reported that auto-oxidation of the catechol rings in DCPL produces an intermediate dicatechol isoindole lysine (DCIL) product formed by an intramolecular reaction of the two catechol rings, yielding an unstable tetracyclic structure. DCIL then reacts with a second DCIL to give a dimeric, di-DCIL. DOPAL-catalyzed formation of AS oligomers may therefore be separable into two steps, the first involving generation of DCPL and the second crosslinking of AS molecules via the interadduct reaction.

Potential Vicious Cycles Involving DOPAL

DOPAL-synuclein interactions might lower thresholds for induction of vicious cycles that threaten neuronal homeostasis. First, synucleinopathy impairs vesicular functions.31,183–188 In particular, DOPAL-induced AS oligomers permeabilize vesicles,103 which would interfere with vesicular sequestration,103 diverting the fate of cytoplasmic dopamine toward DOPAL.21

Second, when MAO acts on cytoplasmic dopamine, hydrogen peroxide and DOPAL are produced concurrently. In the setting of divalent metal cations this generates hydroxyl radicals,153 which peroxidate lipid membranes. The lipid peroxidation products inhibit ALDH, and this builds up DOPAL.189 Indeed, DOPAL may inhibit its own detoxification by ALDH.158

Third, DOPAL evokes mitochondrial dysfunction,150 and mitochondrial dysfunction decreases adenosine triphosphate availability; this decreases the efficiency of the proton pump that is required for vesicular storage and builds up DOPAL. Moreover, DOPAL-oligomerized AS enhances the mitochondrial inhibition exerted by DOPAL.190

The “Smoking Gun”

What links AS with catecholamine deficiency in Lewy body diseases? A straightforward explanation is toxic effects of AS within catecholaminergic neurons. The finding that in Lewy body diseases immunoreactive AS can be present in the same nerve fibers that contain immunoreactive TH seems like a “smoking gun” implicating intraneuronal AS in the death of catecholaminergic neurons.29,191 We have validated methodology to quantify AS colocalization with TH, a marker of catecholaminergic innervation, and assessed associations of AS-TH colocalization with myocardial NE content and cardiac sympathetic neuroimaging data in patients with nOH. Ganglionic AS-TH colocalization indices are higher and myocardial NE lower in Lewy body than in non-Lewy body nOH.192 Lewy body nOH is associated with both increased AS-TH colocalization indices in skin biopsies and decreased myocardial 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity.192 In this study, all Lewy body nOH patients had elevated colocalization indices in skin biopsies and decreased 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity, a combination not seen in non-Lewy body nOH patients. Thus, in Lewy body nOH AS deposition in sympathetic noradrenergic nerves is related to in vivo neuroimaging evidence of myocardial noradrenergic deficiency. This association fits with the view that intraneuronal AS deposition plays a pathophysiological role in the myocardial sympathetic neurodegeneration attending Lewy body nOH. Whether intraneuronal AS deposition is associated with NE deficiency in extracardiac tissues has not yet been reported.

Treatment Implications of the Sick-but-not-Dead Phenomenon and Catecholaldehyde Hypothesis

There is no way to treat neurons that are dead; however, sick-but-not-dead neurons might be salvageable. As noted above, both DOPAL and AS inhibit LAAAD. LAAAD therefore offers a promising target for a form of gene therapy to increase LAAAD levels via an adeno-associated virus. This technology is being applied in PD.193,194

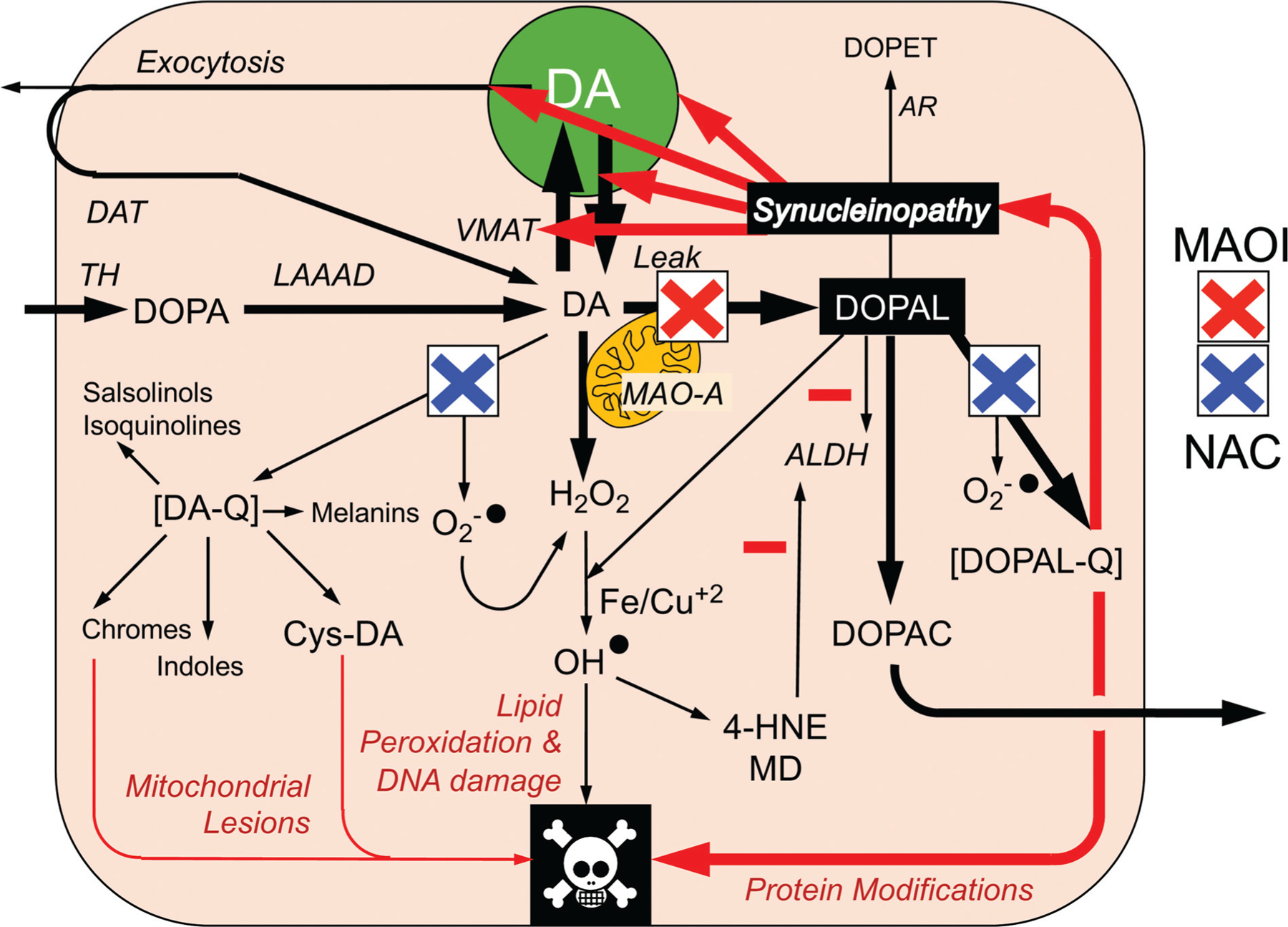

The catecholaldehyde hypothesis predicts that MAO inhibition to decrease DOPAL formation combined with an antioxidant to decrease DOPAL-quinone (DOPAL-Q) formation from DOPAL should prevent autotoxicity from DOPAL-AS interactions and thereby slow catecholaminergic neurodegeneration (►Fig. 5). MAO inhibition alone might not suffice, because although MAO inhibition decreases DOPAL formation,195 concurrently there is increased formation of dopamine oxidation products, and the oxidation products are toxic—the “MAOI tradeoff.”195 Concurrent treatment with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) prevents the increase in endogenous Cys-DA levels exerted by the MAO-B inhibitor selegiline without interfering with the decrease in DOPAL levels.179 NAC also mitigates the protein modification exerted by DOPAL, including oligomerization and quinonization of AS.156

Fig. 5.

Sites of action of a combination of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in testing the catecholaldehyde hypothesis. Cytoplasmic DA oxidizes spontaneously to DA-quinone (DA-Q) and then several oxidation products including aminochrome and 5-S-cysteinyldopamine (Cys-DA). DOPAL oxidizes spontaneously to DOPAL-quinone (DOPAL-Q). DA oxidation products are toxic, via mitochondrial and other lesions. DOPAL reacts with hydrogen peroxide and divalent metal cations to form hydroxyl radicals, which peroxidate membrane lipids. The lipid peroxidation products 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde inhibit ALDH. DOPAL, probably via oxidation to DOPAL-Q, oligomerizes and forms quinoprotein adducts with (“quinonizes”) α-synuclein. DOPAL-induced synucleinopathy impedes vesicular functions. According to the “catecholaldehyde hypothesis,” interactions of DOPAL and α-synuclein set the stage for vicious cycles that challenge homeostasis in catecholaminergic neurons.

Many clinical trials of NAC have been done or are ongoing.196 The results from a recently completed uncontrolled, unblinded clinical trial support the utility of an oral and intravenous dosing regimen197 in motor PD. In humans selegiline also inhibits MAO-A in the brain.198 This is relevant, as MAO-A is the isoform in dopaminergic neurons. Combining NAC with selegiline might protect sick-but-not-dead central dopaminergic and cardiac noradrenergic neurons and test the catecholaldehyde hypothesis for the pathogenesis of PD.

The advantages of MAOI + NAC treatment are that (1) it is likely to be safe, (2) there is a strong hypothesis-driven rationale predicting synergism that is supported by preclinical data, and (3) neurochemical and neuroimaging surrogate biomarkers exist to track the functional status of central and peripheral catecholaminergic neurons. The main weaknesses are that (1) neither treatment is novel; (2) large MAOI trials have failed to slow symptomatic progression of PD199; (3) the bioavailability of NAC at central dopaminergic neurons is unclear; (4) the catecholaldehyde hypothesis so far has not gained traction, although the situation may be changing200; (5) drugs cannot target disease mechanisms specifically; and (6) the field seems to have moved on from focusing on dopamine deficiency to emphasizing genetic, exotoxic, mitochondrial, inflammatory, microbiome, lysosome, proteasome, and exosome theories that seem distantly related to catecholamine metabolism.

Reviving the view that PD fundamentally involves catecholamine deficiencies in the brain and autonomic nervous system and that those deficiencies are due to autotoxicity involving catecholamine oxidation products, thereby rationalizing MAOI + NAC treatment, seems to be an uphill battle. It is hoped that recognition of the sick-but-not-dead concept in diseases involving catecholaminergic neurodegeneration will be a first step in the ascent.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G, McCarty R. Catecholamines: Bridging Basic Science with Clinical Medicine. New York: Academic Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagatsu T, Nabeshima T, Goldstein DS, eds. Catecholamine Research: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Medicine. New York, NY: Plenum; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiden LE. A New Era of Catecholamines in the Laboratory and Clinic. In: Eiden LE ed. New York: Elsevier; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esler M The sympathetic nervous system through the ages: from Thomas Willis to resistant hypertension. Exp Physiol 2011;96 (07):611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grassi G, Mark A, Esler M. The sympathetic nervous system alterations in human hypertension. Circ Res 2015;116(06):976–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziegler MG, Lake CR, Kopin IJ. The sympathetic-nervous-system defect in primary orthostatic hypotension. N Engl J Med 1977; 296(06):293–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Sharabi Y, Brentzel S, Eisenhofer G. Plasma levels of catechols and metanephrines in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Neurology 2003;60(08):1327–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polinsky RJ, Brown RT, Burns RS, Harvey-White J, Kopin IJ. Low lumbar CSF levels of homovanillic acid and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in multiple system atrophy with autonomic failure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51(07):914–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Mash DC, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Determinants of denervation-independent depletion of putamen dopamine in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;35:88–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato S, Oda M, Hayashi H, et al. Decrease of medullary catecholaminergic neurons in multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease and their preservation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1995;132(02):216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M, Kurita A, Hashimoto M, et al. Impaired myocardial 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine uptake in Lewy body disease: comparison between dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2006;240(1–2):15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system [in German]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1960;38:1236–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernheimer H, Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, Jellinger K, Seitelberger F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J Neurol Sci 1973;20(04):415–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N Engl J Med 1988;318 (14):876–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Basile MJ, Mash DC. Catechols in post-mortem brain of patients with Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol 2011;18(05):703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scatton B, Javoy-Agid F, Rouquier L, Dubois B, Agid Y. Reduction of cortical dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin and their metabolites in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res 1983;275(02):321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kish SJ, Shannak KS, Rajput AH, Gilbert JJ, Hornykiewicz O. Cerebellar norepinephrine in patients with Parkinson’s disease and control subjects. Arch Neurol 1984;41(06):612–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannak K, Rajput A, Rozdilsky B, Kish S, Gilbert J, Hornykiewicz O. Noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin levels and metabolism in the human hypothalamus: observations in Parkinson’s disease and normal subjects. Brain Res 1994;639(01):33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cash R, Dennis T, L’Heureux R, Raisman R, Javoy-Agid F, Scatton B. Parkinson’s disease and dementia: norepinephrine and dopa-mine in locus ceruleus. Neurology 1987;37(01):42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarow C, Lyness SA, Mortimer JA, Chui HC. Neuronal loss is greater in the locus coeruleus than nucleus basalis and substantia nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Arch Neurol 2003;60(03):337–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Miller GW, Sharabi Y, Kopin IJ. A vesicular sequestration to oxidative deamination shift in myocardial sympathetic nerves in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2014;131(02):219–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein DS, Sharabi Y. The heart of PD: Lewy body diseases as neurocardiologic disorders. Brain Res 2019;1702:74–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein DS, Pekker MJ, Eisenhofer G, Sharabi Y. Computational modeling reveals multiple abnormalities of myocardial noradrenergic function in Lewy body diseases. JCI Insight 2019; 5:130441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taki J, Nakajima K, Hwang EH, et al. Peripheral sympathetic dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease without autonomic failure is heart selective and disease specific. taki@med. kanazawa-u.ac.jp. Eur J Nucl Med 2000;27(05):566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein DS, Holmes CS, Dendi R, Bruce SR, Li ST. Orthostatic hypotension from sympathetic denervation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2002;58(08):1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tipre DN, Goldstein DS. Cardiac and extracardiac sympathetic denervation in Parkinson’s disease with orthostatic hypotension and inpure autonomic failure. J Nucl Med 2005;46(11):1775–1781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsui H, Udaka F, Oda M, Kubori T, Nishinaka K, Kameyama M. Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy at various parts of the body in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Auton Neurosci 2005;119(01):56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997;388 (6645):839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isonaka R, Sullivan P, Jinsmaa Y, Corrales A, Goldstein DS. Spectrum of abnormalities of sympathetic tyrosine hydroxylase and alpha-synuclein in chronic autonomic failure. Clin Auton Res 2018;28(02):223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakabayashi K, Takahashi H, Ohama E, Ikuta F. Parkinson’s disease: an immunohistochemical study of Lewy body-containing neurons in the enteric nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 1990;79(06):581–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto S, Fukae J, Mori H, Mizuno Y, Hattori N. Positive immunoreactivity for vesicular monoamine transporter 2 in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in substantia nigra. Neurosci Lett 2006;396(03):187–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garland EM, Hooper WB, Robertson D. Pure autonomic failure. Handb Clin Neurol 2013;117:243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coon EA, Singer W, Low PA. Pure autonomic failure. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(10):2087–2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ingelghem E, van Zandijcke M, Lammens M. Pure autonomic failure: a new case with clinical, biochemical, and necropsy data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994;57(06):745–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hague K, Lento P, Morgello S, Caro S, Kaufmann H. The distribution of Lewy bodies in pure autonomic failure: autopsy findings and review of the literature. Acta Neuropathol 1997;94(02): 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arai K, Kato N, Kashiwado K, Hattori T. Pure autonomic failure in association with human alpha-synucleinopathy. Neurosci Lett 2000;296(2–3):171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miura H, Tsuchiya K, Kubodera T, Shimamura H, Matsuoka T. An autopsy case of pure autonomic failure with pathological features of Parkinson’s disease [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2001;41(01):40–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Sato T, et al. Central dopamine deficiency in pure autonomic failure. Clin Auton Res 2008;18(02):58–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufmann H, Hague K, Perl D. Accumulation of alpha-synuclein in autonomic nerves in pure autonomic failure. Neurology 2001; 56(07):980–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shishido T, Ikemura M, Obi T, et al. Alpha-synuclein accumulation in skin nerve fibers revealed by skin biopsy in pure autonomic failure. Neurology 2010;74(07):608–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donadio V, Incensi A, Cortelli P, et al. Skin sympathetic fiber α-synuclein deposits: a potential biomarker for pure autonomic failure. Neurology 2013;80(08):725–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donadio V, Incensi A, Piccinini C, et al. Skin nerve misfolded α-synuclein in pure autonomic failure and Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 2016;79(02):306–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donadio V, Incensi A, El-Agnaf O, et al. Skin α-synuclein deposits differ in clinical variants of synucleinopathy: an in vivo study. Sci Rep 2018;8(01):14246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufmann H, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Palma JA, et al. ; Autonomic Disorders Consortium. Natural history of pure autonomic failure: a United States prospective cohort. Ann Neurol 2017;81 (02):287–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isonaka R, Holmes C, Cook GA Jr, Sullivan P, Sharabi Y, Goldstein DS. Is pure autonomic failure a distinct nosologic entity? Clin Auton Res 2017;27(02):121–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isonaka R, Holmes C, Cook GA, Sullivan P, Sharabi Y, Goldstein DS. Pure autonomic failure without synucleinopathy. Clin Auton Res 2017;27(02):97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95(11):6469–6473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gelpi E, Navarro-Otano J, Tolosa E, et al. Multiple organ involvement by alpha-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders. Mov Disord 2014;29(08):1010–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thaisetthawatkul P, Boeve BF, Benarroch EE, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2004;62 (10):1804–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benarroch EE. Brainstem in multiple system atrophy: clinic-pathological correlations. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2003;23(4–5):519–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Patronas N, Kopin IJ. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of catechols in patients with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104(06):649–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldstein DS, Polinsky RJ, Garty M, et al. Patterns of plasma levels of catechols in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Ann Neurol 1989;26(04):558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raffel DM, Koeppe RA, Little R, et al. PET measurement of cardiac and nigrostriatal denervation in Parkinsonian syndromes. J Nucl Med 2006;47(11):1769–1777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orimo S, Kanazawa T, Nakamura A, et al. Degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve can occur in multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol 2007;113(01):81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cook GA, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Cardiac sympathetic denervation without Lewy bodies in a case of multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20(08):926–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kordower JH, Olanow CW, Dodiya HB, et al. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2013;136(Pt 8):2419–2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DelleDonne A, Klos KJ, Fujishiro H, et al. Incidental Lewy body disease and preclinical Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2008;65 (08):1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pifl C, Rajput A, Reither H, et al. Is Parkinson’s disease a vesicular dopamine storage disorder? Evidence from a study in isolated synaptic vesicles of human and nonhuman primate striatum. J Neurosci 2014;34(24):8210–8218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Sullivan P, et al. Deficient vesicular storage: a common theme in catecholaminergic neurodegeneration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21(09):1013–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller GW, Erickson JD, Perez JT, et al. Immunochemical analysis of vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) protein in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol 1999;156(01):138–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Intra-neuronal vesicular uptake of catecholamines is decreased in patients with Lewy body diseases. J Clin Invest 2011;121(08):3320–3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phan JA, Stokholm K, Zareba-Paslawska J, et al. Early synaptic dysfunction induced by α-synuclein in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 2017;7(01):6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen MK, Kuwabara H, Zhou Y, et al. VMAT2 and dopamine neuron loss in a primate model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2008;105(01):78–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caudle WM, Richardson JR, Wang MZ, et al. Reduced vesicular storage of dopamine causes progressive nigrostriatal neurode-generation. J Neurosci 2007;27(30):8138–8148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taylor TN, Alter SP, Wang M, Goldstein DS, Miller GW. Reduced vesicular storage of catecholamines causes progressive degeneration in the locus ceruleus. Neuropharmacology 2014;76(Pt A):97–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor TN, Caudle WM, Shepherd KR, et al. Nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease revealed in an animal model with reduced monoamine storage capacity. J Neurosci 2009;29(25):8103–8113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guillot TS, Miller GW. Protective actions of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in monoaminergic neurons. Mol Neurobiol 2009;39(02):149–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lohr KM, Stout KA, Dunn AR, et al. Increased vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2; Slc18a2) protects against meth-amphetamine toxicity. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015;6(05):790–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lohr KM, Bernstein AI, Stout KA, et al. Increased vesicular monoamine transporter enhances dopamine release and opposes Parkinson disease-related neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(27):9977–9982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ciesielska A, Samaranch L, San Sebastian W, et al. Depletion of AADC activity in caudate nucleus and putamen of Parkinson’s disease patients; implications for ongoing AAV2-AADC gene therapy trial. PLoS One 2017;12(02):e0169965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grünblatt E, Riederer P. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016;123(02):83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fitzmaurice AG, Rhodes SL, Lulla A, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition as a pathogenic mechanism in Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110(02):636–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen CH, Ferreira JC, Gross ER, Mochly-Rosen D. Targeting aldehyde dehydrogenase 2: new therapeutic opportunities. Physiol Rev 2014;94(01):1–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen CH, Joshi AU, Mochly-Rosen D. The role of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) in neuropathology and neurodegeneration. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2016;25(04):111–123 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, et al. Determinants of buildup of the toxic dopamine metabolite DOPAL in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2013;126(05):591–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y, Mash DC. Decreased vesicular storage and aldehyde dehydrogenase activity in multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015; 21(06):567–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wey MC, Fernandez E, Martinez PA, Sullivan P, Goldstein DS, Strong R. Neurodegeneration and motor dysfunction in mice lacking cytosolic and mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenases: implications for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 2012;7(02):e31522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Casida JE, Ford B, Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan P, Cooney A, Goldstein DS. Benomyl, aldehyde dehydrogenase, DOPAL, and the catecholaldehyde hypothesis for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Chem Res Toxicol 2014;27(08):1359–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiu CC, Yeh TH, Lai SC, et al. Neuroprotective effects of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activation in rotenone-induced cellular and animal models of parkinsonism. Exp Neurol 2015;263:244–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu G, Yu J, Ding J, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 defines and protects a nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuron subpopulation. J Clin Invest 2014;124(07):3032–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang M, Shoeb M, Goswamy J, et al. Overexpression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 reduces oxidation-induced toxicity in SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res 2010;88(03):686–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sherer TB, Kim JH, Betarbet R, Greenamyre JT. Subcutaneous rotenone exposure causes highly selective dopaminergic degeneration and alpha-synuclein aggregation. Exp Neurol 2003;179 (01):9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cannon JR, Tapias V, Na HM, Honick AS, Drolet RE, Greenamyre JT. A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2009;34(02):279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang ZN, Zhang JS, Xiang J, et al. Subcutaneous rotenone rat model of Parkinson’s disease: dose exploration study. Brain Res 2017;1655:104–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lamensdorf I, Eisenhofer G, Harvey-White J, Hayakawa Y, Kirk K, Kopin IJ. Metabolic stress in PC12 cells induces the formation of the endogenous dopaminergic neurotoxin, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde. J Neurosci Res 2000;60(04):552–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Cooney A, Jinsmaa Y, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Rotenone decreases intracellular aldehyde dehydrogenase activity: implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2015;133(01):14–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chidsey CA, Braunwald E. Sympathetic activity and neurotransmitter depletion in congestive heart failure. Pharmacol Rev 1966;18(01):685–700 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pierpont GL, Francis GS, DeMaster EG, Levine TB, Bolman RM, Cohn JN. Elevated left ventricular myocardial dopamine in preterminal idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1983;52(08):1033–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schofer J, Tews A, Langes K, Bleifeld W, Reimitz PE, Mathey DG. Relationship between myocardial norepinephrine content and left ventricular function–an endomyocardial biopsy study. Eur Heart J 1987;8(07):748–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Port JD, Gilbert EM, Larrabee P, et al. Neurotransmitter depletion compromises the ability of indirect-acting amines to provide inotropic support in the failing human heart. Circulation 1990; 81(03):929–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Anderson FL, Port JD, Reid BB, Larrabee P, Hanson G, Bristow MR. Myocardial catecholamine and neuropeptide Y depletion in failing ventricles of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Correlation with beta-adrenergic receptor downregulation. Circulation 1992;85(01):46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Correa-Araujo R, Oliveira JS, Ricciardi Cruz A. Cardiac levels of norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and histamine in Chagas’ disease. Int J Cardiol 1991;31(03):329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Popov VG, Lazutin VK, Khitrov NK, Zhelnov VV, Svistukhin AI. Noradrenaline and adrenaline content in different areas of the heart in patients dying of myocardial infarct [in Russian]. Kardiologiia 1975;15(10):102–107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li W, Knowlton D, Van Winkle DM, Habecker BA. Infarction alters both the distribution and noradrenergic properties of cardiac sympathetic neurons. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004;286 (06):H2229–H2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Neubauer B, Christensen NJ. Norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine contents of the cardiovascular system in long-term diabetics. Diabetes 1976;25(01):6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kontos HA, Richardson DW, Norvell JE. Norepinephrine depletion in idiopathic orthostatic hypotension. Ann Intern Med 1975; 82(03):336–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amino T, Orimo S, Itoh Y, Takahashi A, Uchihara T, Mizusawa H. Profound cardiac sympathetic denervation occurs in Parkinson disease. Brain Pathol 2005;15(01):29–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dickson DW, Fujishiro H, DelleDonne A, et al. Evidence that incidental Lewy body disease is pre-symptomatic Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2008;115(04):437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, et al. Axonal alpha-synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2008;131(Pt 3):642–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fujishiro H, Frigerio R, Burnett M, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation correlates with clinical and pathologic stages of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2008;23(08):1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K, Langston JW, Braak H. Diminished tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the cardiac conduction system and myocardium in Parkinson’s disease: an anatomical study. Acta Neuropathol 2009;118(06):777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takahashi M, Ikemura M, Oka T, et al. Quantitative correlation between cardiac MIBG uptake and remaining axons in the cardiac sympathetic nerve in Lewy body disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86(09):939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Plotegher N, Berti G, Ferrari E, et al. DOPAL derived alpha-synuclein oligomers impair synaptic vesicles physiological function. Sci Rep 2017;7:40699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Volpicelli-Daley LA. Effects of α-synuclein on axonal transport. Neurobiol Dis 2017;105:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mexas LM, Florang VR, Doorn JA. Inhibition and covalent modi-fication of tyrosine hydroxylase by 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite. Neurotoxicology 2011;32 (04):471–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tehranian R, Montoya SE, Van Laar AD, Hastings TG, Perez RG. Alpha-synuclein inhibits aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity in dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem 2006;99(04):1188–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nagatsu T, Sawada M. Biochemistry of postmortem brains in Parkinson’s disease: historical overview and future prospects. J Neural Transm Suppl 2007;•••(72):113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meredith IT, Eisenhofer G, Lambert GW, Dewar EM, Jennings GL, Esler MD. Cardiac sympathetic nervous activity in congestive heart failure. Evidence for increased neuronal norepinephrine release and preserved neuronal uptake. Circulation 1993;88 (01):136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Polinsky RJ, Goldstein DS, Brown RT, Keiser HR, Kopin IJ. Decreased sympathetic neuronal uptake in idiopathic orthostatic hypotension. Ann Neurol 1985;18(01):48–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Perfeito R, Cunha-Oliveira T, Rego AC. Reprint of: revisiting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease-resemblance to the effect of amphetamine drugs of abuse. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;62:186–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schapira AH, Jenner P. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2011;26(06):1049–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Catecholamine autotoxicity. Implications for pharmacology and therapeutics of Parkinson disease and related disorders. Pharmacol Ther 2014;144(03): 268–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carlsson A, Fornstedt B. Possible mechanisms underlying the special vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 1991;136:16–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weingarten P, Zhou QY. Protection of intracellular dopamine cytotoxicity by dopamine disposition and metabolism factors. J Neurochem 2001;77(03):776–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dukes AA, Korwek KM, Hastings TG. The effect of endogenous dopamine in rotenone-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005;7(5–6):630–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Khan FH, Sen T, Maiti AK, Jana S, Chatterjee U, Chakrabarti S. Inhibition of rat brain mitochondrial electron transport chain activity by dopamine oxidation products during extended in vitro incubation: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005;1741(1–2):65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hasegawa T, Matsuzaki-Kobayashi M, Takeda A, et al. Alpha-synuclein facilitates the toxicity of oxidized catechol metabolites: implications for selective neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS Lett 2006;580(08):2147–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bisaglia M, Mammi S, Bubacco L. Kinetic and structural analysis of the early oxidation products of dopamine: analysis of the interactions with alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem 2007;282(21): 15597–15605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chen L, Ding Y, Cagniard B, et al. Unregulated cytosolic dopamine causes neurodegeneration associated with oxidative stress in mice. J Neurosci 2008;28(02):425–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paris I, Lozano J, Perez-Pastene C, Muñoz P, Segura-Aguilar J. Molecular and neurochemical mechanisms in PD pathogenesis. Neurotox Res 2009;16(03):271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Leong SL, Cappai R, Barnham KJ, Pham CL. Modulation of alpha-synuclein aggregation by dopamine: a review. Neurochem Res 2009;34(10):1838–1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mosharov EV, Larsen KE, Kanter E, et al. Interplay between cytosolic dopamine, calcium, and alpha-synuclein causes selective death of substantia nigra neurons. Neuron 2009;62(02): 218–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hastings TG. The role of dopamine oxidation in mitochondrial dysfunction: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2009;41(06):469–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bisaglia M, Greggio E, Maric D, Miller DW, Cookson MR, Bubacco L. Alpha-synuclein overexpression increases dopamine toxicity in BE2-M17 cells. BMC Neurosci 2010;11:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Surmeier DJ, Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Goldberg JA. The origins of oxidant stress in Parkinson’s disease and therapeutic strategies. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011;14(07):1289–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wu YN, Johnson SW. Dopamine oxidation facilitates rotenone-dependent potentiation of N-methyl-D-aspartate currents in rat substantia nigra dopamine neurons. Neuroscience 2011; 195:138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jana S, Sinha M, Chanda D, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by quinone oxidation products of dopamine: implications in dopamine cytotoxicity and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1812(06):663–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Surh YJ, Kim HJ. Neurotoxic effects of tetrahydroisoquinolines and underlying mechanisms. Exp Neurobiol 2010;19(02):63–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lee HJ, Baek SM, Ho DH, Suk JE, Cho ED, Lee SJ. Dopamine promotes formation and secretion of non-fibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers. Exp Mol Med 2011;43(04):216–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gautam AH, Zeevalk GD. Characterization of reduced and oxidized dopamine and 3,4-dihydrophenylacetic acid, on brain mitochondrial electron transport chain activities. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1807(07):819–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Muñoz P, Paris I, Sanders LH, Greenamyre JT, Segura-Aguilar J. Overexpression of VMAT-2 and DT-diaphorase protects substantia nigra-derived cells against aminochrome neurotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1822(07):1125–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bisaglia M, Greggio E, Beltramini M, Bubacco L. Dysfunction of dopamine homeostasis: clues in the hunt for novel Parkinson’s disease therapies. FASEB J 2013;27(06):2101–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Su Y, Duan J, Ying Z, et al. Increased vulnerability of parkin knock down PC12 cells to hydrogen peroxide toxicity: the role of salsolinol and NM-salsolinol. Neuroscience 2013;233:72–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Banerjee K, Munshi S, Sen O, Pramanik V, Roy Mukherjee T, Chakrabarti S. Dopamine cytotoxicity involves both oxidative and nonoxidative pathways in SH-SY5Y cells: potential role of alpha-synuclein overexpression and proteasomal inhibition in the etiopathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2014;2014:878935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cai H, Liu G, Sun L, Ding J. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 making molecular inroads into the differential vulnerability of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuron subtypes in Parkinson’s disease. Transl Neurodegener 2014;3:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Herrera A, Muñoz P, Steinbusch HWM, Segura-Aguilar J. Are dopamine oxidation metabolites involved in the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease? ACS Chem Neurosci 2017;8(04):702–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Burbulla LF, Song P, Mazzulli JR, et al. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science 2017;357(6357):1255–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mor DE, Tsika E, Mazzulli JR, et al. Dopamine induces soluble α-synuclein oligomers and nigrostriatal degeneration. Nat Neurosci 2017;20(11):1560–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Badillo-Ramírez I, Saniger JM, Rivas-Arancibia S. 5-S-cysteinyl-dopamine, a neurotoxic endogenous metabolite of dopamine: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 2019;129:104514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Linsenbardt AJ, Wilken GH, Westfall TC, Macarthur H. Cytotoxicity of dopaminochrome in the mesencephalic cell line, MN9D, is dependent upon oxidative stress. Neurotoxicology 2009;30(06): 1030–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Segura-Aguilar J On the role of aminochrome in mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci 2019;13:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Montine TJ, Picklo MJ, Amarnath V, Whetsell WO Jr, Graham DG. Neurotoxicity of endogenous cysteinylcatechols. Exp Neurol 1997;148(01):26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Storch A, Ott S, Hwang YI, et al. Selective dopaminergic neurotoxicity of isoquinoline derivatives related to Parkinson’s disease: studies using heterologous expression systems of the dopamine transporter. Biochem Pharmacol 2002;63(05):909–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Nagatsu T Isoquinoline neurotoxins in the brain and Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Res 1997;29(02):99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mattammal MB, Haring JH, Chung HD, Raghu G, Strong R. An endogenous dopaminergic neurotoxin: implication for Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegeneration 1995;4(03):271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Marchitti SA, Deitrich RA, Vasiliou V. Neurotoxicity and metabolism of the catecholamine-derived 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde: the role of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Pharmacol Rev 2007;59(02):125–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Panneton WM, Kumar VB, Gan Q, Burke WJ, Galvin JE. The neurotoxicity of DOPAL: behavioral and stereological evidence for its role in Parkinson disease pathogenesis. PLoS One 2010;5 (12):e15251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Burke WJ, Li SW, Chung HD, et al. Neurotoxicity of MAO metabolites of catecholamine neurotransmitters: role in neuro-degenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology 2004;25(1–2):101–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Burke WJ, Li SW, Williams EA, Nonneman R, Zahm DS. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde is the toxic dopamine metabolite in vivo: implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Brain Res 2003;989(02):205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kristal BS, Conway AD, Brown AM, et al. Selective dopaminergic vulnerability: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde targets mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 2001;30(08):924–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lamensdorf I, Eisenhofer G, Harvey-White J, Nechustan A, Kirk K, Kopin IJ. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde potentiates the toxic effects of metabolic stress in PC12 cells. Brain Res 2000;868(02): 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Leiphon LJ, Picklo MJ Sr. Inhibition of aldehyde detoxification in CNS mitochondria by fungicides. Neurotoxicology 2007;28(01): 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Li SW, Lin TS, Minteer S, Burke WJ. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide generate a hydroxyl radical: possible role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2001;93(01):1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Anderson DG, Mariappan SV, Buettner GR, Doorn JA. Oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopaminergic metabolite, to a semiquinone radical and an ortho-quinone. J Biol Chem 2011;286(30):26978–26986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Nilsson GE, Tottmar O. Biogenic aldehydes in brain: on their preparation and reactions with rat brain tissue. J Neurochem 1987;48(05):1566–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Jinsmaa Y, Sharabi Y, Sullivan P, Isonaka R, Goldstein DS. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde-induced protein modifications and their mitigation by N-acetylcysteine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2018;366(01):113–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Vermeer LM, Florang VR, Doorn JA. Catechol and aldehyde moieties of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde contribute to tyrosine hydroxylase inhibition and neurotoxicity. Brain Res 2012; 1474:100–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.MacKerell AD Jr, Pietruszko R. Chemical modification of human aldehyde dehydrogenase by physiological substrate. Biochim Biophys Acta 1987;911(03):306–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Saha S, Khan MAI, Mudhara D, Deep S. Tuning the balance between fibrillation and oligomerization of α-synuclein in the presence of dopamine. ACS Omega 2018;3(10): 14213–14224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Huenchuguala S, Sjödin B, Mannervik B, Segura-Aguilar J. Novel alpha-synuclein oligomers formed with the aminochrome-glutathione conjugate are not neurotoxic. Neurotox Res 2019;35 (02):432–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Muñoz P, Cardenas S, Huenchuguala S, et al. DT-diaphorase prevents aminochrome-induced alpha-synuclein oligomer formation and neurotoxicity. Toxicol Sci 2015;145(01):37–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Pham CL, Leong SL, Ali FE, et al. Dopamine and the dopamine oxidation product 5,6-dihydroxylindole promote distinct on-pathway and off-pathway aggregation of alpha-synuclein in a pH-dependent manner. J Mol Biol 2009;387(03):771–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Burke WJ, Kumar VB, Pandey N, et al. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein by DOPAL, the monoamine oxidase metabolite of dopamine. Acta Neuropathol 2008;115(02):193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Follmer C, Coelho-Cerqueira E, Yatabe-Franco DY, et al. Oligomerization and membrane-binding properties of covalent adducts formed by the interaction of α-synuclein with the toxic dopamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL). J Biol Chem 2015;290(46):27660–27679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Werner-Allen JW, Levine RL, Bax A. Superoxide is the critical driver of DOPAL autoxidation, lysyl adduct formation, and cross-linking of α-synuclein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017;487 (02):281–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Werner-Allen JW, DuMond JF, Levine RL, Bax A. Toxic dopamine metabolite DOPAL forms an unexpected dicatechol pyrrole adduct with lysines of α-synuclein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2016;55(26):7374–7378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Werner-Allen JW, Monti S, DuMond JF, Levine RL, Bax A. Isoindole linkages provide a pathway for DOPAL-mediated cross-linking of α-synuclein. Biochemistry 2018;57(09):1462–1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Winner B, Jappelli R, Maji SK, et al. In vivo demonstration that alpha-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(10):4194–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Gustafsson G, Lindström V, Rostami J, et al. Alpha-synuclein oligomer-selective antibodies reduce intracellular accumulation and mitochondrial impairment in alpha-synuclein exposed astrocytes. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14(01):241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Deas E, Cremades N, Angelova PR, et al. Alpha-synuclein oligomers interact with metal ions to induce oxidative stress and neuronal death in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016;24(07):376–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan P, Gross D, Cooney A, Sharabi Y, Goldstein DS. Divalent metal ions enhance DOPAL-induced oligomerization of alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett 2014;569:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Kang SS, Zhang Z, Liu X, et al. TrkB neurotrophic activities are blocked by α-synuclein, triggering dopaminergic cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114(40): 10773–10778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Asanuma M, Miyazaki I, Ogawa N. Dopamine- or L-DOPA-induced neurotoxicity: the role of dopamine quinone formation and tyrosinase in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox Res 2003;5(03):165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Segura-Aguilar J On the role of endogenous neurotoxins and neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2017; 12(06):897–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Mazzulli JR, Mishizen AJ, Giasson BI, et al. Cytosolic catechols inhibit alpha-synuclein aggregation and facilitate the formation of intracellular soluble oligomeric intermediates. J Neurosci 2006;26(39):10068–10078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Mor DE, Daniels MJ, Ischiropoulos H. The usual suspects, dopa-mine and alpha-synuclein, conspire to cause neurodegeneration. Mov Disord 2019;34(02):167–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Cagle BS, Crawford RA, Doorn JA. Biogenic aldehyde-mediated mechanisms of toxicity in neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Toxicol 2019;13:16–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Dell’Acqua S, Bacchella C, Monzani E, et al. Prion peptides are extremely sensitive to copper induced oxidative stress. Inorg Chem 2017;56(18):11317–11325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Goldstein DS, Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan P, Sharabi Y. N-acetylcysteine prevents the increase in spontaneous oxidation of dopamine during monoamine oxidase inhibition in PC12 cells. Neurochem Res 2017;42(11):3289–3295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Anderson DG, Florang VR, Schamp JH, Buettner GR, Doorn JA. Antioxidant-mediated modulation of protein reactivity for 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite. Chem Res Toxicol 2016;29(07):1098–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Jinsmaa Y, Sharabi Y, Sullivan P, Isonaka R, Goldstein DS. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde-induced protein modifications and their mitigation by N-Acetylcysteine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2018;366(01):113–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Rees JN, Florang VR, Eckert LL, Doorn JA. Protein reactivity of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite, is dependent on both the aldehyde and the catechol. Chem Res Toxicol 2009;22(07):1256–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Gaugler MN, Genc O, Bobela W, et al. Nigrostriatal overabun-dance of α-synuclein leads to decreased vesicle density and deficits in dopamine release that correlate with reduced motor activity. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123(05):653–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Guo JT, Chen AQ, Kong Q, Zhu H, Ma CM, Qin C. Inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporter-2 activity in alpha-synuclein stably transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2008;28 (01):35–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Park SS, Schulz EM, Lee D. Disruption of dopamine homeostasis underlies selective neurodegeneration mediated by alpha-synuclein. Eur J Neurosci 2007;26(11):3104–3112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Volles MJ, Lansbury PT Jr. Vesicle permeabilization by protofibrillar alpha-synuclein is sensitive to Parkinson’s disease-linked mutations and occurs by a pore-like mechanism. Biochemistry 2002;41(14):4595–4602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Lotharius J, Barg S, Wiekop P, Lundberg C, Raymon HK, Brundin P. Effect of mutant alpha-synuclein on dopamine homeostasis in a new human mesencephalic cell line. J Biol Chem 2002;277(41): 38884–38894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Mosharov EV, Staal RG, Bové J, et al. Alpha-synuclein over-expression increases cytosolic catecholamine concentration. J Neurosci 2006;26(36):9304–9311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Jinsmaa Y, Florang VR, Rees JN, Anderson DG, Strack S, Doorn JA. Products of oxidative stress inhibit aldehyde oxidation and reduction pathways in dopamine catabolism yielding elevated levels of a reactive intermediate. Chem Res Toxicol 2009;22(05): 835–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Sarafian TA, Yacoub A, Kunz A, et al. Enhanced mitochondrial inhibition by 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl-acetaldehyde (DOPAL)-oligomerized α-synuclein. J Neurosci Res 2019;97(12):1689–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Del Tredici K, Braak H. Lewy pathology and neurodegeneration in premotor Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2012;27(05): 597–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Isonaka R, Rosenberg AZ, Sullivan P, et al. Alpha-synuclein deposition within sympathetic noradrenergic neurons is associated with myocardial noradrenergic deficiency in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Hypertension 2019;73(04):910–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Mittermeyer G, Christine CW, Rosenbluth KH, et al. Long-term evaluation of a phase 1 study of AADC gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Hum Gene Ther 2012;23(04):377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Christine CW, Bankiewicz KS, Van Laar AD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided phase 1 trial of putaminal AADC gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2019;85(05): 704–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Goldstein DS, Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Comparison of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in decreasing production of the autotoxic dopamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde in PC12 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016; 356(02):483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Deepmala SJ, Slattery J, Kumar N, et al. Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;55:294–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Monti DA, Zabrecky G, Kremens D, et al. N-acetyl cysteine is associated with dopaminergic improvement in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2019;106(04):884–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Fowler JS, Logan J, Volkow ND, et al. Evidence that formulations of the selective MAO-B inhibitor, selegiline, which bypass first-pass metabolism, also inhibit MAO-A in the human brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40(03):650–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. ; ADAGIO Study Investigators. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361(13):1268–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Masato A, Plotegher N, Boassa D, Bubacco L. Impaired dopamine metabolism in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Mol Neurodegener 2019;14(01):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]