Abstract

Purpose

Little data exists on endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms with the Acandis Acclino low-profile self-expanding closed-cell stent systems and is mainly limited to short- or midterm results. We report our long-term, single-centre experience with three generations of Acclino stents treating complex intracranial aneurysms.

Methods

62 wide-necked intracranial aneurysms were treated electively using 88 Acclino stent systems. Single stent-assisted coiling was the preferred treatment in 38 cases and the kissing-Y stenting technique in 24 cases. We analysed demographic data and long-term follow-up results.

Results

All stents were successfully deployed with immediate complete (Raymond Roy occlusion classification, RROC I) or near-complete occlusion (RROC II) achieved in 93,5%. Follow-up was available in 55 cases with a mean follow-up of 36 months (range 9–80 months). Long-term RROC I or II was achieved in 49 cases (89,1%). Three cases of stable residual aneurysmal filling were observed (5,5%). Seven aneurysms (12,7%) demonstrated a worsening on follow-up leading either to a neck remnant (4 cases, 7,3%) or to an aneurysm recurrence (3 cases, 5,5%). One recurrent aneurysm was retreated with coilembolization (1,8%). The directly procedural-related complication rate was 4,8%. Seven cases of clinically silent in-stent stenosis (12,7%; morbidity n = 0) were detected on long-term follow-up, six of them using the kissing-Y stenting technique.

Conclusion

Endovascular treatment of various intracranial aneurysms using the Acandis Acclino stent systems is safe and efficient with high aneurysm occlusion rates combined with low complication rates on long-term follow-up. Overall, rates of in-stent stenosis are low but may depend on the treatment technique (single stent-assisted coiling versus kissing-Y stenting with coiling).

Keywords: Aneurysm, stent, coil, stenosis

Introduction

The stent-assisted coiling technique was developed to enable endovascular treatment of bifurcation aneurysms and aneurysms with an unfavourable dome-to-neck ratio, previously uncoilable. The aneurysmal recurrence rate compared to sole coiling was reduced. 1

Several different flexible self-expanding stents were introduced over the last years and clinically used for the treatment of those complex intracranial aneurysms. 2

The design of low profile self-expandable stents such as LVIS Jr. (MicroVention, Tustin, California), LEO baby (Balt, Montmorency, France), and Acclino (Acandis, Pforzheim, Germany) enables the deployment in small arteries and the delivery through microcatheters. The ongoing evolution of these stent systems with improved features and a broader spectrum of stent diameters further increased the technical possibilities of minimally invasive intracranial aneurysm treatment.

Risks of thrombosis, stent luxation and in-stent stenosis increase with the method of stent-assisted coiling compared to sole coiling. 3 Hence, long-term follow-up is essential to evaluate the safety and effectiveness and compare the different stent systems. 4

Acclino stents were introduced in 2012 as the second generation of low-profile closed-cell Acandis stents. The newest, fourth generation of Acclino stents was introduced in 2016, the Acclino flex plus stent. Only a few studies have described the initial clinical experiences and follow-up results with Acclino stents in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms in small cohorts.5–10 However, as far as we know, they focus on the second and third generations and are limited to short-term or mid-term results.

This retrospective study included all generations of Acclino stents used for stent-assisted coiling with single and multiple stenting, including the kissing-Y stenting technique. 11 We analysed the safety and effectiveness and evaluated the long-term results of 57 complex intracranial aneurysms treated with these stent systems.

Material and methods

Patients

In a retrospective review, 61 patients with 62 complex wide-necked intracranial aneurysms were treated electively with a total of 88 Acclino stents between 2012 and 2018. Ethical approval was obtained from our local hospital's institutional review board.

Primary endpoint of this study was the analysis of the long-term occlusion rate of the treated aneurysms, secondary endpoint the rate of in-stent stenosis on long-term follow-up. To ensure a long-term follow-up for each patient, no patients treated after December 2018 were included in this study.

Every case was interdisciplinarily discussed with the neurosurgical department. Endovascular, neurosurgical, and conservative management were discussed with all patients, and written informed consent was obtained.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the local hospital's Institutional Review Board for this retrospective study. Parts of the data have been published previously in a single-centre study on the initial and midterm results of the Acclino stent. 5

Premedication and anticoagulation

Before each procedure, dual antiplatelet therapy was administered with Acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg daily) and Clopidogrel (75 mg daily) for at least seven days before the procedure. Patients were not treated until adequate response to Clopidogrel and Acetylsalicylic acid was achieved, confirmed by Multiplate® test and since 07/2015, in vitro platelet function testing (Born method). Here, adequate response to Acetylsalicylic acid was defined as aggregation rates of < 30%, low-responders were defined with aggregation rates of 30–50% and non-responders with aggregation rates of more than 50%.

For Clopidogrel, adequate response was defined as aggregation rates under 45%, low-responders with aggregation rates between 45% and 55%, while non-responders were defined with aggregation rates of more than 55%.

Low-responders to Clopidogrel received 150 mg daily until adequate response was proven.

There were no non-responders to Clopidogrel and no non- or low-responders to Acetylsalicylic acid.

Heparin was administered intraarterially during endovascular therapy with monitoring, keeping the activated clotting time (ACT) between 200–300 s. After treatment, all patients were prescribed 100 mg of Acetylsalicylic acid and 75 mg of Clopidogrel daily for a minimum of one year and twelve weeks, respectively. If the first control DSA and MRA showed no in-stent-stenosis, Clopidogrel was stopped while Acetylsalicylic acid was administered lifelong in most cases, depending on comorbidities or other anticoagulants.

After diagnosis of in-stent-stenosis the patients received dual antiplatelet therapy for at least six months. In cases of neurological symptoms or progression of the stenosis on following examinations, dual antiplatelet therapy was reestablished. In cases of Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) - morphologic stable stenosis and asymptomatic patients, Clopidogrel was stopped.

Interventional procedure

The angiographic examination was carried out on a biplane angiographic system (Artis BA Biplane, Siemens, Erlangen Germany) under general anesthesia.

A 6F Envoy® guiding catheter (Codman) was navigated through a 6F short sheath or a 6F long sheath into one internal carotid artery (ICA) or in one vertebral artery (VA) depending on the location of the aneurysm. To precisely plan the intervention, three-dimensional rotational angiography was obtained.

After correct placement of the stent(s) in the parent vessel using sole stenting or kissing-Y stenting technique, one of the microcatheters previously used for stent deployment or an Echelon™ 10 microcatheter was navigated through the interstices of the stent(s) into the aneurysm and detachable coils (Axium™: 3D, Helix, and Axium™ Prime: 3D, Helix; Covidien) were inserted.

Follow-Up

Immediately after stent-assisted coiling, postprocedural angiograms were performed, and all patients underwent cranial Computed Tomography (cCT) to evaluate potential complications. Complications were defined as periprocedural thrombus formation, material dislocation, acute hemorrhage or infarction.

The patients” first follow-up was performed after 3–6 months, usually using both DSA and Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) with 3D time-of-flight (TOF) and contrast-enhanced MRA. The second and third follow-ups were mainly obtained by MRA at 12–18 months and 24–30 months and after this every two years. In cases of MR-morphological suspected in-stent stenosis, complex progression, or MR-morphological evidence of aneurysm recanalization, additional DSA was carried out.

The Raymond-Roy Occlusion Classification (RROC) was used as the standard for evaluating treated aneurysms.

A possible in-stent stenosis was measured by comparing the in-stent diameter on DSA follow-up with the immediately postprocedural measured diameter. In-stent stenosis was defined as ≥ 50% narrowing of parent artery compared to original diameter on immediate post-interventional DSA. Additionally, an eventual post-stenotic flow deceleration in DSA was evaluated, and symptomatic patients received cMRI evaluating possible ischemic lesions.

All examinations were evaluated by experienced interventional neuroradiologists.

Acandis acclino stents:

Three different types of Acclino stent systems were used: the 1.9 F stent (the second generation), the Acclino flex stent (the third generation), and the Acclino flex plus stent (the fourth generation), all of them being self-expandable nitinol microstents with a closed-cell design.

Each stent system features three radio-opaque markers at the proximal and the distal end of the stent, indicating the correct position and expansion. The stents are retrievable and repositionable. In all used stent-systems the distal end of the transport wire has a highly flexible atraumatic soft tip.

The 1.9 F stent is compatible with any 0.0165“microcatheter. Most Acclino flex stent systems and Acclino flex plus stent systems are deliverable through microcatheters with 0.0165” – 0.017” ID. The stents with 6,5 mm diameter are compatible with any 0.021” microcatheter. Sequential coil embolization of the aneurysm can often be performed without changing the microcatheter after stent deployment.

Compared to the 1.9 F stent system, the Acclino flex stent system includes an optimized asymmetric cell design ensuring an improved vessel wall apposition even in tortuous vessels.

As the latest and fourth generation, the Acclino flex plus stent system is less thrombogenic (in vitro), allows increased visibility because of improved X-ray markers and allows an enhanced expansion behaviour.

Moreover, the Acclino flex plus stent system is available in a bigger range of diameters (newly available in 3 mm, 4 mm and 5,5 mm adding to the previous diameters of 3,5 mm, 4,5 mm and 6,5 mm), recommended for vessel diameters from 1,5 mm to 6 mm. Stent diameters of 5,5 mm and 6,5 mm are available in four different stent lengths (from 20 mm to 35 mm), diameters of 3 mm – 4,5 mm are available in five different stent lengths (from 15 mm to 35 mm). 12

Statistical assessment

A median test was used to compare continuous variables. Categorial variables are reported as n (%). Results were considered statistically significant with p-values <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Aneurysm characteristics

62 saccular aneurysms in 61 patients were treated electively using stent-assisted coiling. There were 18 male (29,5%) and 43 female (70,5%) patients with a mean age of 56 years (range 28 to 79 years).

Eleven patients initially presented with a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) caused by aneurysm rupture and were treated with coil embolization in the emergency situation. When angiographic follow-up showed an aneurysmal recanalization or no sufficient occlusion was possible initially, additional stent-assisted coiling was performed a few weeks later electively. No stents were placed in an acute SAH setting.

Nine unruptured aneurysms were pretreated and showed aneurysmal recanalization either after sole coiling (n = 7) or after initial neurosurgical clipping (n = 2).

The mean size of the treated aneurysms was 7 mm × 6 mm (range 2 mm – 18 mm). The distribution of the treated aneurysms is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of the treated aneurysms.

| location | AcomA | BA | ICA | MCA | PICA / VA | ACA | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases | 26 | 15 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 62 |

| percentage | 41,9% | 24,2% | 16,1% | 11,3% | 3,2% | 3,2% | 100% |

The aneurysms were located at the anterior communicating artery (AcomA), the basilar artery (BA), the internal carotid artery (ICA), the middle cerebral artery (MCA), the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), the vertebral artery (VA) and the anterior cerebral artery (ACA).

24 complex bifurcation aneurysms were treated using the kissing-Y stenting technique, including eight aneurysms located at the AcomA, six at the BA, six at the MCA, two at the ICA, one at the PICA, and one at the ACA.

Treatment

We used the Acclino 1.9 F stent treating 21 aneurysms (2012–2014), the Acclino flex stent for 25 aneurysms (2014–2016), and the Acclino flex plus stent for 16 aneurysms (2016–2018), depending on the year of treatment and thus the availability of the stent.

In the subgroup of 24 complex bifurcation aneurysms treated using the kissing-Y stenting technique, one BA aneurysm was treated by sole stenting without coiling because of a vessel origin at the aneurysmal fundus.

A total of 88 stents were used to treat 62 aneurysms. All stents were deployed successfully with a technical success rate of 100%. A single stent was used for stent-assisted coiling in most cases (n = 36). When using the kissing-Y stenting technique (n = 24), two stents were used. In one case, two stents were used placing one stent in each ACA-branch when coiling an aneurysm of the AcomA-complex. When treating one aneurysm located at the ICA, a second stent was placed because of coil-luxation despite an already placed stent.

Follow-up

Immediate angiographic control after stent-assisted coilembolization (n = 62) showed complete or near-complete occlusion in 93,5% (RROC I: 87,1% [n = 54]; RROC II: 6,5% [n = 4]) and incomplete occlusion in 6,5% (RROC III: n = 4).

Of the 62 cases, 55 were available for follow-up. The mean follow-up time was 36 months (range 9–80 months). 52 of these 55 cases (94,5%) initially presented complete or near-complete occlusion in immediate angiographic control (RROC I: 87,3% [n = 48]; RROC II: 7,3% [n = 4]), while three cases demonstrated incomplete occlusion (RROC III: 5,5%).

Follow-up demonstrated complete or near-complete aneurysmal occlusion in 49 cases (RROC I: 78,2% [n = 43]; RROC II: 10,9% [n = 6]). Incomplete occlusion on follow-up was seen in six cases (RROC III: 10,9%), either due to aneurysmal recanalization (n = 3; 5,5%) or due to stable residual aneurysmal filling without clinical significance (n = 3; 5,5%).

Among the 55 cases available for follow-up, RROC remained stable in 48 patients (87,3%) and worsened in seven (12,7%). Among those seven patients, four patients demonstrated only slight recanalization, still showing near-complete occlusion (RROC II: 7,3%). The remaining three patients had an aneurysm recurrence with incomplete occlusion on long-term follow-up (RROC III: 5,5%) after initially presenting complete or near-complete occlusion (RROC I or II). Two small BA aneurysms (one of them treated with the kissing-Y stenting technique) recurred after 36 months and remained stable on the subsequent follow-up twelve months later, respectively. One ICA aneurysm demonstrated incomplete occlusion on 56 months follow-up after preceding perennial stable neck remnant leading to a retreatment by coiling (1,8%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Follow-up data.

| electively treated saccular aneurysms | total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| treated with sole stent-assisted coiling | treated with kissing-Y stenting + coiling | ||

| total cases* | n = 38 | n = 24 | n = 62 |

| periprocedural complications** - morbidity - mortality |

n = 2 (5,3%) - n = 0 (0%) - n = 1 (2,6%) |

n = 1 (4,2%) - n = 1 (4,2%) - n = 0 (0%) |

n = 3 (4,8%) - n = 1 (1,6%) - n = 1 (1,6%) |

| immediate angiographic control RROC I or II RROC III |

n = 36 (94,7%) n = 2 (5,3%) |

n = 22 (91,7%) n = 2 (8,3%) |

n = 58 (93,5%) n = 4 (6,5%) |

| available for follow-up | n = 33 | n = 22 | n = 55 |

| average follow-up (months) | 37,6 | 33,5 | 36 |

| immediate angiographic control RROC I or II RROC III |

n = 32 (97%) n = 1 (3%) |

n = 20 (90,9%) n = 2 (9,1%) |

n = 52 (94,5%) n = 3 (5,5%) |

| follow-up RROC I or II RROC III |

n = 30 (90,1%) n = 3 (9,1%) |

n = 19 (86,4%) n = 3 (13,6%) |

n = 49 (89,1%) n = 6 (10,9%) |

| in-stent-stenosis - morbidity |

n = 1 (3%) - n = 0 (0%) |

n = 6 (27,3%) - n = 0 (0%) |

n = 7 (12,7%) - n = 0 (0%) |

* One patient underwent two separate treatment sessions for two aneurysms, thus complications and morbidity are calculated in the cohort of aneurysms (n = 62), not the cohort of patients (n = 61).

** including periprocedural thrombosis, coil-luxation, or aneurysm-rupture with resulting SAH.

Complications

In total, the rate of periprocedural complications was n = 3 (4,8%) of the 62 treated aneurysms, leading to a morbidity in one case and mortality in another case.

Periprocedural complications included thrombosis in one case (n = 1), resulting in an ischemic stroke treated with Tirofiban. A following MRI showed acute ischemic lesions not only in the treated region of the anterior circulation but also in the posterior circulation, most probably due to a cardioembolic event or a catheter-associated embolism (morbidity: n = 1).

In another case, a coil dislocated despite correct stent placement, successfully treated with placement of another stent (n = 1) leading to no further complications.

One aneurysm located at the AcomA ruptured during endovascular treatment. After stent deployment of an Acclino flex stent contrast angiograms showed contrast extravasation indicating aneurysm rupture. Despite correct stent placement in the DSA control, aneurysm rupture presumably occurred during stent deployment resulting in SAH and the patient's death (mortality: n = 1). However, the exact cause remains unclear.

On long-term follow-up (n = 55), chronic in-stent stenosis occurred in seven cases (12,7%) with no symptoms or infarction in these cases (morbidity: n = 0). No cases of stent-occlusions were seen. Rates of in-stent stenosis were significantly higher (p < 0.05) when treating saccular aneurysms with the kissing-Y technique (6/22; 21,7%) compared to rates of in-stent stenosis after treating aneurysms with sole stent-assisted coiling (1/33; 3%).

Illustrative cases

Case 1

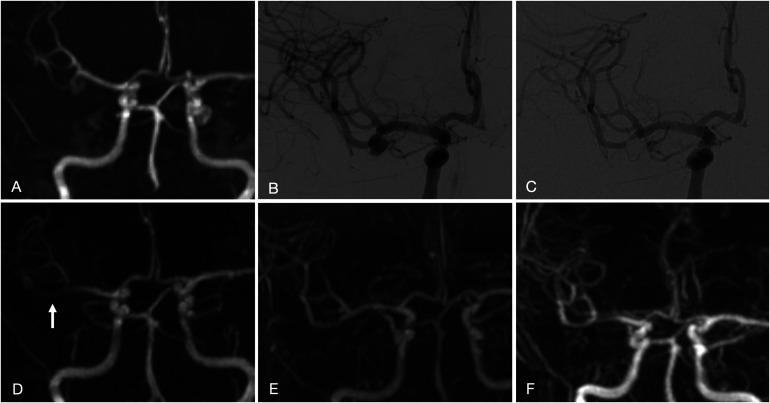

A middle-aged patient with a family history of ruptured intracranial aneurysms presented with three intracranial aneurysms incidentally found on MRI (Figure 1A, 1B). A 7 mm × 5 mm wide-necked aneurysm of the right MCA bifurcation was treated electively by stent-assisted coil embolization (Figure 1C). The patient refused neurosurgical clipping.

Figure 1.

3D TOF MRA (A, D) and DSA in frontal projection, right internal carotid artery (ICA) injection (B, C), showing a wide-necked right MCA bifurcation aneurysm before treatment (A, B) and at 16-month follow up after stent-assisted coil embolization with complete aneurysmal occlusion (C, D). Contrast-enhanced MRA at 16 months (E) and 80 months (F) demonstrate a stable complete occlusion of the aneurysm, and a patent preserved M2-branch (inferior trunk) without in-stent stenosis. Note the in-stent signal reduction of the stented inferior trunk on 3D TOF MRA at 16 months follow-up erroneously simulating in-stent stenosis (arrow in D). 5

Initially, a 3,5 mm × 25 mm Acclino stent was deployed from the inferior trunk of the M2 segment directly originating out of the aneurysm sac into the M1 segment. Complete occlusion of the aneurysm was achieved with additional coil embolization (Figure 1C, 1D).

Stable complete aneurysm occlusion was seen on the last DSA and MRA follow-up after 16 months (Figure 1E). Recently, the 80-month MRA follow-up showed unchanged complete aneurysmal occlusion (RROC 1) (Figure 1F). There was no symptomatic complication or device-related morbidity.

Case 2

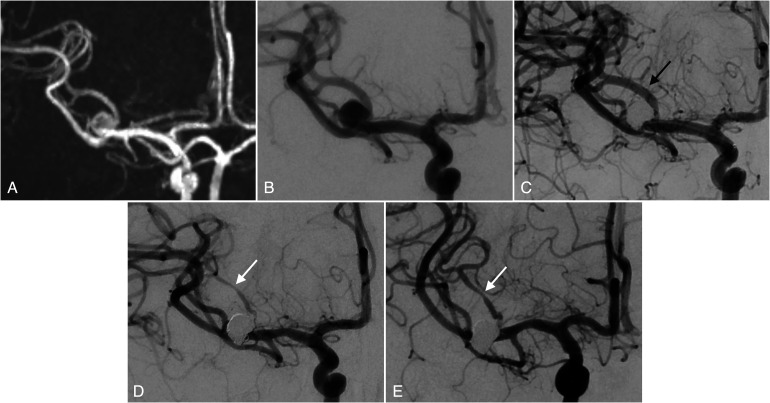

A middle-aged patient presented with an intracranial aneurysm with diameters of 6 mm × 7 mm located at the right MCA bifurcation, incidentally found on MRI (Figure 2A, 2B). The patient refused neurosurgical clipping.

Figure 2.

3D TOF MRA (A) and DSA in frontal projection, right internal carotid artery (ICA) injection (B-E), showing a wide-necked right MCA bifurcation aneurysm before treatment (A, B), immediately after stent-assisted coil embolization with kissing-Y stenting (C), DSA at 33-month follow up (D) and 57-month follow-up (E). Long-term follow-up demonstrates a stable complete occlusion of the aneurysm and in-stent stenosis of an M2-branch (superior trunk, white arrows), compared to the initial diameter after stenting (black arrow in C).

The aneurysm was treated electively using the kissing-Y stenting technique and coiling. 11 The two 3,5 mm × 30 mm Acclino flex stents were simultaneously deployed from the efferent branches of the superior and inferior trunk of the right MCA to the bifurcation, and in parallel „kissing” fashion from the distal to the proximal portion of the parent vessel (M1-trunk of the right MCA). Deployment was performed by slowly unsheathing the stents alternately. After withdrawing one microcatheter, the coiling of the aneurysm sac followed.

Immediate angiographic control (Figure 2C) and follow-up DSA after 33 (Figure 2D) and 57 months (Figure 2E) showed a stable complete aneurysmal occlusion (RROC I).

Compared to immediate angiographic control, in-stent stenosis was detected on follow-up DSA in the superior trunk of the right MCA (Figure 2D, 2E). No infarction was detected in MRI controls, and the patient was asymptomatic.

Discussion

Our retrospective study of 62 aneurysms treated with stent-assisted coiling using all generations of low-profile Acclino stents led to several interesting findings:

First, long-term occlusion rates were high, with 89% of aneurysms achieving RROC I and II.

Second, in our 9-year experience of aneurysm treatment with these stent systems, they have proven to be a safe treatment option with low complication rates and low aneurysmal recurrence rates, even on long-term follow-up.

Furthermore, we detected a noteworthy number of clinically silent in-stent stenoses in our cohort when using the kissing-Y stenting technique.

Finally, our study results demonstrate that previous promising short- and midterm results of endovascularly treated aneurysms using Acclino stents are applicable to a very long-term follow-up period of up to 80 months.

Various stent systems are available for intracranial stent-assisted coiling. In the last decade, low-profile stents such as the Acclino, LVIS Jr, Neuroform Atlas and LEO Baby expanded the range of treatment options of complex intracranial aneurysms. They can be delivered by a microcatheter with an internal diameter of 0,0165 inches enabling deployment even in small arteries.

Technical feasibility, procedural safety, and short- and midterm occlusion rates of these currently used low-profile stents are mainly reported to be satisfactory.5, 13–15 However, data about long-term treatment efficacy and potential late complications are still limited.

To date, the mean follow-up of 36 months in our study (range 9–80 months) is longer than in previously published studies of low-profile stents.5–10 Recently, Goertz et al. reported a RROC I or II rate of 98,5% on immediate angiographic control and 89,5% on 21-months follow-up using the Acclino stents. Interestingly, only 38,8% of patients were available for follow-up evaluation. 7 We observed similar immediate occlusion rates (93,5% RROC I/II) in our cohort. 88,7% of the cases (55/62) were reached for follow-up with comparable occlusion rates of 89,1% on our mean follow-up of 36 months. Incomplete occlusion was noticed in 10,9% (6/55), including three aneurysm recurrences (5,5%). One of them was recoiled. In a comparative study between the Acclino 1.9 and the Acclino flex stent, the authors report a recoiling rate of 8,4% and an RROC I or II on follow-up of 70,5% and 27,4%, respectively. 6 Until now, the latest generation of Acclino stents, the Acclino flex plus stent, was not included in larger studies to the best of our knowledge. In contrast, our data included a total of 16 cases treated with the latest Acclino stent generation with 15 cases available for follow-up (mean follow-up 25,7 months). Additional data about the three different stent systems used in our study are provided in a supplementary table.

Most studies on other low-profile stents present follow-up results of 12 months or less. The short- and midterm adequate occlusion rates (RROC I or II) with the Neuroform Atlas stent (92,3%), 14 the LVIS jr. stent (91,5%) 15 and the LEO Baby stent (82,8%) 16 compare favourably with our long-term occlusion rates. However, Djurdjevic et al. reported a lower RROC I/II rate of 63,2% in their LEO Baby series. 17 Whether these other low-profile stents provide a long-term efficacy and safety profile comparable to Acclino stents needs to be investigated in future larger comparative studies.

Until now, long-term follow-up evaluations of stent-assisted coiling of complex intracranial aneurysms are primarily available for non-low-profile stents, including the Enterprise 18 and the Neuroform stent 19 which show aneurysmal occlusion rates similar to our findings.

In-stent stenoses on follow-up in our study population were observed in 12,7% of cases (7/55). Feng et al. reported similar rates of in-stent stenoses with the LVIS stent (10,2%) and the Enterprise stent (16,8%). 20 Interestingly, our rate of in-stent stenosis in aneurysms treated with sole stent-assisted coiling was only 3% (n = 1/33). Using the kissing-Y stenting technique led to notably higher rates of in-stent stenosis (27,3%; n = 6/22). However, there was no morbidity associated with the in-stent stenoses in our study.

The kissing-Y stenting technique was used for the treatment of selected wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms when sole stent-assisted coiling was not possible due to anatomical features and complexity of the appropriate bifurcation aneurysms. The placement of two stents next to each other in the parent vessel and vascular angular remodelling by the kissing-Y technique in wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms seem to impact the development of in-stent stenoses on follow-up. 21

The Enterprise stent has a closed cell design like the Acandis Acclino stent. Using the crossing-Y technique Limbucci et al. reported no in-stent-stenosis with the Enterprise stent with a mean follow-up of 27 months. 22 In this technique the second stent is deployed through the interstices and then within the first deployed stent, while in the kissing-Y technique the parallel deployed stents lie next to each other in the parent artery. The latter are possibly not deployed fully, probably promoting a stenosis. However, since the in-stent stenosis in our series occurred in the distal vessels containing one stent, a reduction in blood flow due to the stents, that may not be fully expanded in the parent artery, may promote a stenosis.

A meta-analysis by Cagnazzo et al. reported in-stent stenosis rates after Y-stent-assisted coiling of bifurcation aneurysms in 2,3% including different types of Y-stenting and different stent systems. 23 The results of our study show higher rates of in-stent stenosis, probably based on the used technique. However, Cagnazzo et al. did not distinguish and compare the different techniques and stent systems concerning their rates of in-stent stenosis making an explanation for us more difficult.

In previous follow-up studies of Acclino stents, Goertz et al. observed no in-stent stenosis, and Dietrich et al. reported a 1,1% rate of in-stent stenoses in their respective cohort of patients.7, 8 The lower rates of in-stent stenoses might be attributable to the lower number of cases treated with Y-configurated stenting.

The periprocedural complication rates in our series were low (3/62; 4,8%). We observed one case of periprocedural thromboembolism (1,6%) with resulting infarction in the right anterior circulation and the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) territory, probably due to cardiac embolism. Hemorrhagic complication occurred in one case (1,6%) when placing the stent resulting in the patient's death. Coil-luxation occurred in one case (1,6%) and was resolved by placing a second stent with no resulting morbidity.

Dietrich et al. found a periprocedural thromboembolic event rate of 7.4% and a hemorrhagic complication rate of 2,1% for the Acclino stents. 6 Goertz et al. reported a thromboembolic complication rate of 10.7% for the Acclino and the Neuroform Atlas stents. 8 Comparable rates of thromboembolic events (9,9%) are noted by Djurdjevic et al. for the Leo Baby stent. 17 Grossberg et al. reported periprocedural complications in 8 of 83 patients treated with LVIS Jr device, including a hemorrhagic rate of 4,8%. 21

Our study is limited by its retrospective design. Further, Acclino stents were not used in all patients undergoing elective stent-assisted aneurysm treatment in our institution. The respective treatment strategy and stent selection were based upon the neurointerventionalist's discretion and therefore might lead to a selection bias. Follow-up angiographic results were not independently assessed by a core laboratory.

However, with its long follow-up period of up to 80 months, the study contributes essentially to a better understanding of the true efficacy and safety of stent-assisted coilembolization using Acclino stents, which is of utmost importance for the patients. Nonetheless, these promising long-term results have to be confirmed by future prospective registry studies.

Conclusion

Endovascular treatment of various complex intracranial aneurysms using the Acandis Acclino stent systems for stent-assisted coiling is safe and efficient with high aneurysm occlusion rates on long-term follow-up (mean 36 months). High occlusion rates on long-term follow-up (RROC II or II in 89,1%) combined with low rates of periprocedural complications (n = 3; 4,8%; morbidity in 1 case and mortality in 1 case) and low rates of aneurysm recurrence (3 cases, 5,5%). In-stent stenosis occurred in a total of seven cases (12,7%), leading to morbidity in no cases. Concerning in-stent stenosis, the kissing-Y technique showed higher rates (27,3%) than sole stent-assisted coiling (3%). Here, further research seems necessary to compare the kissing-Y technique with other techniques and devices available for treating complex bifurcation aneurysms.

Contributors

Katharina Melber and Frederik W. Boxberg contributed equally to this paper and share first authorship. Katharina Melber: designed the study, analysed and interpreted data for the work, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Frederik W. Boxberg: designed the study, analysed and interpreted data for the work, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Martin Schlunz-Hendann, Friedhelm Brassel: acquired, analysed, and interpreted data for the work, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dominik F. J. Grieb: acquired, analysed, and interpreted data for the work, designed the study, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from our local hospital's institutional review board.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

ORCID iDs: Frederik W Boxberg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4055-5751

Dominik F J Grieb https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8842-8903

References

- 1.Wanke I, Doerfler A, Schoch B, et al. Treatment of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms with a self-expanding stent system: initial clinical experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 1192–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park SY, Oh JS, Oh HJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of low-profile, self-expandable stents for treatment of intracranial aneurysms: initial and midterm results - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interv Neurol 2017; 6: 170–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro M, Becske T, Sahlein D, et al. Stent-supported aneurysm coiling: a literature survey of treatment and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012; 33: 159–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phan K, Huo YR, Jia F, et al. Meta-analysis of stent-assisted coiling versus coiling-only for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2016; 31: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brassel F, Grieb D, Meila D, et al. Endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms using acandis acclino stents. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 854–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietrich P, Gravius A, Mühl-Benninghaus R, et al. Single center experience in stent-assisted coiling of Complex intracranial aneurysms using low-profile stents : the ACCLINO® Stent Versus the ACCLINO® Flex Stent. Clin Neuroradiol 2021; 31: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goertz L, Smyk MA, Mpotsaris A, et al. Long-term angiographic results of the low-profile acandis acclino stent for treatment of intracranial aneurysms : a multicenter study. Clin Neuroradiol 2020; 30: 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goertz L, Smyk MA, Siebert E, et al. Low-Profile Laser-cut stents for endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms : incidence, clinical presentation and risk factors of thromboembolic events. Clin Neuroradiol 2021; 31: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tureli D, Sabet S, Senol S, et al. Stent-assisted coil embolization of challenging intracranial aneurysms: initial and mid-term results with low-profile ACCLINO devices. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158: 1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pflaeging M, Goertz L, Smyk MA, et al. Treatment of recurrent and residual aneurysms with the low-profile Acandis Acclino stent: multi-center review of 19 patients. J Clin Neurosci 2021; 90: 199–205.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brassel F, Melber K, Schlunz-Hendann M, et al. Kissing-Y stenting for endovascular treatment of complex wide necked bifurcation aneurysms using acandis acclino stents: results and literature review. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 386–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://www.acandis.com/acclino-flex-plus-stent-122-en, Accessed 17 Nov 2021.

- 13.Aydin K, Arat A, Sencer S, et al. Stent-Assisted coiling of wide-neck intracranial aneurysms using low-profile LEO baby stents: initial and midterm results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 1934–1941.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pranata R, Yonas E, Deka H, et al. Stent-Assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms using a nitinol-based stent (neuroform atlas): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2020; 43: 1049–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poncyljusz W, Biliński P, Safranow K, et al. The LVIS/LVIS Jr. stents in the treatment of wide-neck intracranial aneurysms: multicentre registry. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luecking H, Struffert T, Goelitz P, et al. Stent-Assisted coiling using Leo+ baby stent : immediate and mid-term results. Clin Neuroradiol 2021; 31: 409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djurdjevic T, Young V, Corkill R, et al. Treatment of broad-based intracranial aneurysms with low profile braided stents: a single center analysis of 101 patients. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fargen KM, Hoh BL, Welch BG, et al. Long-term results of enterprise stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2012; 71: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulcsár Z, Göricke SL, Gizewski ER, et al. Neuroform stent-assisted treatment of intracranial aneurysms: long-term follow-up study of aneurysm recurrence and in-stent stenosis rates. Neuroradiology 2013; 55: 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng X, Qian Z, Liu P, et al. Comparison of recanalization and in-stent stenosis between the low-profile visualized intraluminal support stent and enterprise stent-assisted coiling for 254 intracranial aneurysms. World Neurosurg 2018; 109: e99–e104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melber K, Meila D, Draheim P, et al. Vascular angular remodeling by kissing-Y stenting in wide necked intracranial bifurcation aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 1233–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limbucci N, Renieri L, Nappini S, et al. Y-stent assisted coiling of bifurcation aneurysms with enterprise stent: long-term follow-up. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cagnazzo F, Limbucci N, Nappini S, et al. Y-Stent-Assisted coiling of wide-neck bifurcation intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 122–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]