Abstract

Background

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing remains controversial due to the debate about overdetection and overtreatment. Given the lack of published data regarding PSA testing rates in the population with spinal cord injury (SCI) within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), there is concern for potential disparities and overtesting in this patient population. In this study, we sought to identify and evaluate national PSA testing rates in veterans with SCI.

Methods

Using the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure Corporate Data Warehouse, we extracted PSA testing data for all individuals with a diagnosis of SCI. Testing rates were calculated, analyzed by race and age, and stratified according to published American Urological Association guideline groupings for PSA testing.

Results

We identified 45,274 veterans at 129 VA medical centers with a diagnosis of SCI who had records of PSA testing in 2000 through 2017. Veterans who were only tested prior to SCI diagnosis were excluded. Final cohort data analysis included 37,243 veterans who cumulatively underwent 261,125 post-SCI PSA tests during the given time frame. Significant differences were found between African American veterans and other races veterans for all age groups (0.47 vs 0.46 tests per year, respectively, aged ≤ 39 years; 0.83 vs 0.77 tests per year, respectively, aged 40–54 years; 1.04 vs 1.00 tests per year, respectively, aged 55–69 years; and 1.08 vs 0.90 tests per year, respectively, aged ≥ 70 years; P < .001).

Conclusions

Significant differences exist in rates of PSA testing in persons with SCI based on age and race. High rates of testing were found in all age groups, especially for African American veterans aged ≥ 70 years.

Prostate cancer will be diagnosed in 12.5% of men during their lifetime. It is the most commonly diagnosed solid organ cancer in men.1 However, prostate cancer screening for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) remains controversial due to concerns about overdiagnosis, as the overall risk of dying of prostate cancer is only 2.4%.1

To address the risk and benefits of PSA testing, in 2012 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against routine PSA testing.2 Updated 2018 recommendations continued this recommendation in men aged > 70 years but acknowledged a small potential benefit in men aged 55 to 69 years and suggested individualized shared decision making between patient and clinician.3 In addition, American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for the early detection of prostate cancer recommend against PSA screening in men aged < 40 years or those aged > 70 years, shared decision making for individuals aged 55 to 70 years or in high-risk men aged 40 to 55 years (ie, family history of prostate cancer or African American race).4 PSA screening is not recommended for men with a life expectancy shorter than 10 to 15 years aged > 70 years.4

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US.5 In addition, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Spinal Cord Injury and Disorders System of Care operates 25 centers throughout the US.6 Life expectancy following spinal cord injury (SCI) increased significantly through the 1980s but has since plateaued, with life expectancy being impacted by age at injury, completeness of injury, and neurologic level.7,8 As part of a program of uniform care, all persons with SCI followed at the Spinal Cord Injury and Disorders System of Care centers are offered comprehensive annual evaluations, including screening laboratory tests, such as PSA level.9

Patients with SCI present a unique challenge when interpreting PSA levels, given potentially confounding factors, including neurogenic bladder management, high rates of bacteriuria, urinary tract infections (UTIs), testosterone deficiency, and pelvic innervation that differs from the noninjured population.10,11 Unfortunately, the literature on prostate cancer prevalence and average PSA levels in patients with SCI is limited by the small scope of studies and inconsistent data.10–16 Therefore, the purpose of the current investigation was to quantify and analyze the rates of annual PSA testing for all men with SCI in the VHA.

METHODS

Approval was granted by the Richmond VA Medical Center (VAMC) Institutional Review Board in Virginia, and by the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) data access request tracker system for extraction of data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Microsoft Structured Query Language was used for data programming and query design. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata version 15.1 with assistance from professional biostatisticians.

Only male veterans with a nervous system disorder affecting the spinal cord or with myelopathy were included, based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 9 and 10 codes, corresponding to traumatic and nontraumatic myelopathy. Veterans diagnosed with myelopathy based on ICD codes corresponding to progressive or degenerative myelopathies, such as multiple sclerosis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, were excluded.

For each veteran, extracted data included the unique identification number, date of birth, ICD code, date ICD code first appeared, race, gender, death status (yes/no), date of death (when applicable), date of each PSA test, PSA test values, and the VAMC where each test was performed. Only tests for total PSA were included. The date that the ICD code first appeared served as an approximation for the date of SCI. The time frame for the study included all PSA tests in the VINCI database for 2000 through 2017. However, only post-SCI PSA tests were included in the analysis. Duplicate tests (same date/time) were eliminated.

Race is considered a risk factor for prostate cancer only for African American patients, likely due to racial health disparities.17 Given this, we chose to categorize race as either African American or other, with a third category for missing/inconsistent reporting. Age at time of the PSA test was categorized into 4 groups (≤ 39, 40–54, 55–69, and ≥ 70 years) based on AUA guidelines.4 The annual PSA testing rate was calculated for each veteran with SCI as the number of PSA tests per year. A mean annual PSA test rate was then calculated as the weighted (by exposure time) mean value for all annual PSA testing rates from 2000 through 2017 for each age group and race. Annual exposure was calculated for each veteran and defined as the number of days a veteran was eligible to have a PSA test. This started with the date of SCI diagnosis and ended with either the date of death or the date of last PSA. If a veteran moved from one age group to another in 1 year, the first part of this year’s exposure was included in the calculation of the annual PSA testing rate for the younger group and the second part was included for the calculation of the older group. For deceased veterans, the death date was excluded from the exposure period, and their exposure period ended on the day before death.

Statistical Analysis

To compare PSA testing rates between African American race and other races, Poisson regression was used with exposure treated as an offset (exposures were summed across years for each veteran). An indicator (dummy) variable for African American race vs other races was coded, and statistical significance was set at P < .05. To check sensitivity for the Poisson assumption that the mean was equal to the variance, negative binomial regression was used. To assess for geographic PSA testing rate variability, the data were further analyzed based on the locations where PSA tests were performed. This subanalysis was limited to veterans who had all PSA tests in a single station. For each station, the average PSA testing rate was calculated for each veteran, and the mean for all annual PSA testing rates was used to determine station-specific PSA testing rates.

RESULTS

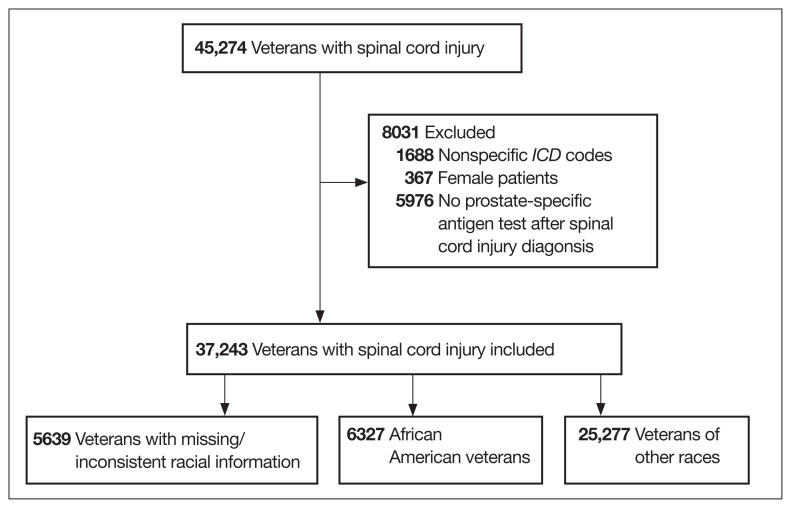

A total of 45,274 veterans were initially identified of which 367 females were excluded (Figure 1). Moreover, 1688 male veterans were excluded for ICD codes that were less relevant, yielding 43,219 male veterans with relevant ICD codes. From this group, an additional 5976 were excluded because no PSA test was found after the SCI date. The racial makeup of the remaining 37,243 male veterans included 6327 African American patients, 25,277 of other races, and 5639 with missing/inconsistent race data. The included sample received care in ≥ 1 of 129 VAMCs. The final cohort yielded 261,125 PSA tests. The Table shows PSA tests categorized by age group and race.

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion Criteria

TABLE.

PSA Tests in Veterans by Age and Race

| Age groups | African American race | Other races | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | PSA tests, No. | No.a | PSA tests, No. | ||

| ≤ 39 y | 268 | 489 | 1226 | 2184 | < .001 |

|

| |||||

| 40–54 y | 2195 | 9028 | 6776 | 25,753 | < .001 |

|

| |||||

| 55–69 y | 4438 | 27,604 | 17,308 | 105,308 | < .001 |

|

| |||||

| ≥ 70 y | 2144 | 11,391 | 11,664 | 52,765 | < .001 |

Abbreviation: PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Total number of veterans for all age groups does not match actual cohort size, as some received PSA testing in more than one age group.

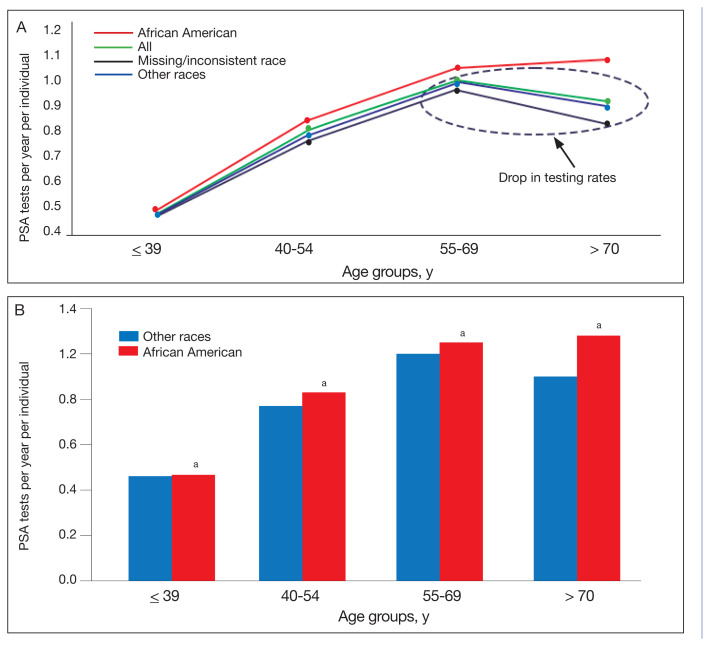

The PSA testing rate rose for veterans in the age groups ≤ 39, 40 to 54, and 55 to 69 years (Figure 2A). The PSA testing rate dropped for the oldest age group (≥ 70 years), for the entire population, and the other race and missing/inconsistent race groups; however, PSA testing rates continued to rise in the African American group aged ≥ 70 years. For the entire population, average PSA testing rates in tests per year for the age groups were 0.46 (aged ≤ 39 years), 0.78 (aged 40–54 years), 1.0 (aged 55–69 years), and 0.91 (aged ≥ 70 years). However, PSA testing rates were significantly higher for the African American vs other races group at all ages (0.47 vs 0.46 tests per year, respectively, aged ≤ 39 years; 0.83 vs 0.77 tests per year, respectively, aged 40–54 years; 1.04 vs 1.00 tests per year, respectively, aged 55–69 years; and 1.08 vs 0.90 tests per year respectively, aged ≥ 70 years; P < .001) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Average PSA Testing Rates for Veterans With SCI

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SCI, spinal cord injury.

aP <. 001.

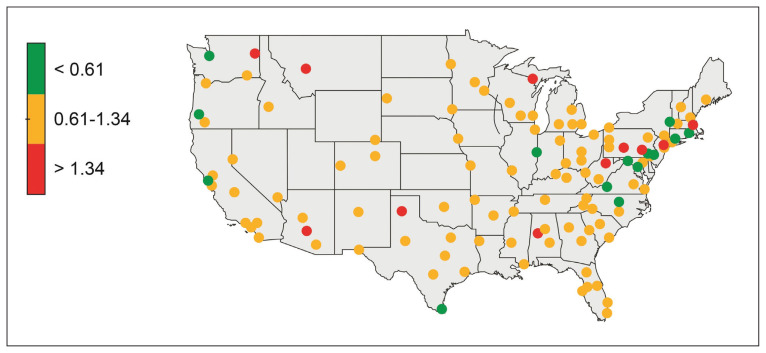

Of the cohort of 37,243 veterans, 28,396 (76.2%) had their post-SCI tests done at a single facility, 6770 (18.1%) at 2 locations, and 2077 (5.5%) at > 2 locations. Single-station group data were included in a subanalysis to determine the mean (SD) PSA testing rates, which for the 123 locations was 0.98 (0.36) tests per veteran per year (range, 0.2–3.0 tests per veteran per year). Figure 3 shows a heat map of the US: each dot represents a specific VAMC and shows PSA testing rate variability between stations.

FIGURE 3.

Heat Map Showing Annual PSA Testing Rates for Veterans With SCI at VA Facilities

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SCI, spinal cord injury; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Terciles of post-SCI average annual PSA testing rates for individual VA stations (colored dots) can be seen. Lowest tercile (green, < 0.61 tests per veteran per year); middle tercile (yellow, 0.61–1.34 tests per veteran per year); and highest tercile (red, > 1.34 tests per veteran per year).

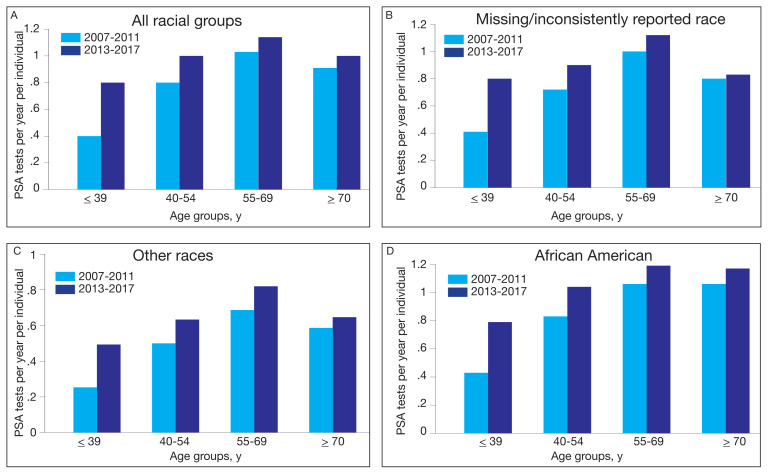

To assess the impact of the 2012 USPSTF recommendations on PSA testing rates in veterans with SCI, mean PSA testing rates were calculated for 5 years before the recommendations (2007–2011) and compared with the average PSA testing rate for 5 years following the updated recommendations (2013–2017). The USPSTF updated its recommendation again in 2018 and acknowledged the potential benefit for PSA screening in certain patient populations.2,3 Surprisingly, and despite recommendations, the results show a significant increase in PSA testing rates in all age groups for all races (P < .001) (Figure 4). For the entire population, the average PSA testing rates for 2007 to 2011 in tests per year were 0.39, 0.76, 1.03, and 0.89 for the ≤ 39 years, 40 to 54 years, 55 to 69 years, and ≥ 70 years age groups, respectively. Likewise, the average PSA testing rates for years 2013 to 2017 in tests per year were 0.75, 0.96, 1.13, and 0.98 for the ≤ 39 years, 40 to 54 years, 55 to 69 years, and ≥ 70 years age groups, respectively, with an increased rate of testing of 0.92, 0.26, 0.10, and 0.11, respectively, from years 2007– 2011 to 2013–2017 (P < .001).

FIGURE 4.

Rates of Annual PSA testing in Veterans With SCI Before and After USPSTF Recommendationsa

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SCI, spinal cord injury; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

aP < .001 for all comparisons.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to establish testing rates and analyze PSA testing trends across races and age groups in veterans with SCI. This is the largest cohort of patients with SCI analyzed in the literature. The key findings of this study were that despite clear AUA guidelines recommending against PSA testing in patients aged ≤ 39 years and ≥ 70 years, there are high rates of testing in veterans with SCI in these age groups (0.46 tests per year in those aged ≤ 39 years and 0.91 tests per year in those aged ≥ 70 years). In terms of race, as expected based on increased risk, African American veterans with SCI had higher PSA test rates.18 However, the continued increase in PSA testing rate for African American veterans aged ≥ 70 years was unexpected and not seen in other racial groups. As racial disparities are known to affect prostate cancer outcomes in African American men, it is reassuring that PSA testing was actually higher among African American men with SCI in our population, suggesting this vulnerable population is not being left behind in terms of screening. 17 In contrast to other studies that show a lower rate of PSA screening in patients with SCI, our study suggests general PSA overtesting in veterans with SCI and a need for improved education for both veterans and their health care practitioners.19

Prostate Cancer Incidence

Although the exact mechanism behind alterations in prostate function in the SCI population have yet to be fully elucidated, research suggests that the prostate behaves differently after SCI. Animal models of prostate gland denervation show decreased prostate volume and suggest that SCI may lead to a reduction in prostatic secretory function associated with autonomic dysfunction. Shim and colleagues hypothesized that impaired autonomic prostate innervation alters the prostatic volume and PSA in patients with SCI.10

Additional studies looking at actual PSA levels in men with SCI reveal conflicting data.10–15,20 Toricelli and colleagues retrospectively studied 140 men with SCI, of whom 34 had PSA levels available and found that mean PSA was not significantly different for patients with SCI compared with controls, but patients using clean intermittent catheterization had 2-fold higher PSA levels.21 In contrast, Konety and colleagues found that mean PSA was not significantly different from uninjured controls in their cohort of 79 patients with SCI, though they did find a correlation between indwelling catheter use and a higher PSA.22

Studies have shown an overall decreased risk of prostate cancer in patients with SCI, though the mechanism remains unclear. A large cohort study from Taiwan showed a lower risk of prostate cancer for 54,401 patients with SCI with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.73.23 Patel and colleagues found the overall rate of prostate cancer in the population of veterans with SCI was lower than the general uninjured VA population, though this study was limited by scope with only 350 patients with SCI.24 A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 9 studies evaluating the prevalence of prostate cancer in men with SCI found a reduction of up to 65% in the risk of prostate cancer in men with SCI, and PSA was found to be a poor screening tool for prostate cancer due to large study heterogeneity.16

PSA Screening

This study identified widespread overscreening using the PSA test in veterans with SCI, which is likely attributable to many factors. Per VHA Directive 1176, all eligible veterans are offered yearly interdisciplinary comprehensive evaluations, including laboratory testing, and as such veterans with SCI have high rates of annual visit attendance due to the complexity of their care.9 PSA testing is included in the standard battery of laboratory tests ordered for all patients with SCI during their annual examinations. Additionally, many SCI specialists use the PSA level in patients with SCI for identifying cystitis or prostatitis in patients with colonization who may not experience typical symptoms. Everaert and colleagues demonstrated the clinical utility for localizing UTIs to the upper or lower tract, with elevated PSA indicating prostatitis. They found that serum PSA has a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 100% in the differential diagnosis of prostatitis and pyelonephritis.25 As such, the high PSA screening rates may be reflective of diagnostic use for infection rather than for cancer screening.

Likely as a response to the USPSTF recommendations, there has been a national slow decline in overall PSA screening rates since 2012.26–28 A study from Vetterlein and colleagues examining changes in the PSA screening trends related to USPSTF recommendations found an 8.5% decline in overall PSA screening from 2012 to 2014.29 However, the increase in PSA testing across all ages and races in the VA population with SCI over the same period is not entirely understood and suggests the need for further research and education in this area. Additionally, as factors associated with SCI impact the life expectancy of these patients, further shared decision making is needed in deciding whether to pursue PSA screening in this population to minimize unnecessary screening in patients with a life expectancy of < 10 to 15 years.

Limitations

This study is limited by the use of data identified by ICD codes rather than by review of individual health records. This required the use of decision algorithms for data points, such as the date of SCI. In addition, analysis was not able to capture shared decision making that may have contributed to PSA screening outside the recommended age ranges based on additional risk factors, such as family history of lethal malignancy. Furthermore, a detailed attempt to define specific age-adjusted PSA levels was beyond the scope of this study but will be addressed in later publications. In addition, we did not exclude individuals with a diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma, prostatitis, or recurrent UTIs because the onset, duration, and severity of disease could not be definitively ascertained. Finally, veterans with SCI are unique and may not be reflective of individuals with SCI who do not receive care within the VA. However, despite these limitations, this is, to our knowledge, the largest and most comprehensive study evaluating PSA testing rates in individuals with SCI.

CONCLUSIONS

Currently, PSA screening is recommended following shared decision making for patients at average risk aged 55 to 70 years. Patients with SCI experience many conditions that may affect PSA values, but data regarding normal PSA ranges and rates of prostate cancer in this population remain sparse. The study demonstrated high rates of overtesting in veterans with SCI, higher than expected testing rates in African American veterans, a paradoxical increase in PSA testing rates after the 2012 publication of the USPSTF PSA guidelines, and wide variability in testing rates depending on VA location.

African American men were tested at higher rates across all age groups, including in patients aged > 70 years. To balance the benefits of detecting clinically significant prostate cancer vs the risks of invasive testing in high-risk populations with SCI, more work is needed to determine the clinical impact of screening practices. Future work is currently ongoing to define age-based PSA values in patients with SCI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part through funding from the Center for Rehabilitation Science and Engineering, Virginia Commonwealth University Health System.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Ethics and consent

Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study at Central Virginia Veterans Affairs Health Care System and from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure Data Access Request Tracker system for extraction of data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest or outside sources of funding with regard to this article.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Key statistics for prostate cancer. [Accessed June 2, 2023]. Updated January 12, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html .

- 2.Moyer VA U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):120–134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901–1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013;190(2):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. [Accessed June 2, 2023]. Updated August 15, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutVHA.asp .

- 6.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Spinal cord injuries and disorders system of care. [Accessed June 2, 2023]. Updated January 31, 2022. https://www.sci.va.gov/VAs_SCID_System_of_Care.asp .

- 7.DeVivo MJ, Chen Y, Wen H. Cause of death trends among persons with spinal cord injury in the United States: 1960–2017. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(4):634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y, DiPiro N, Krause JS. Health factors and spinal cord injury: a prospective study of risk of cause-specific mortality. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(7):594–602. doi: 10.1038/s41393-019-0264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1176(2): Spinal Cord Injuries and Disorders System of Care. [Accessed June 2, 2023]. Published September 30, 2019. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8523 .

- 10.Shim HB, Jung TY, Lee JK, Ku JH. Prostate activity and prostate cancer in spinal cord injury. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9(2):115–120. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynne CM, Aballa TC, Wang TJ, Rittenhouse HG, Ferrell SM, Brackett NL. Serum and semen prostate specific antigen concentrations are different in young spinal cord injured men compared to normal controls. J Urol. 1999;162(1):89–91. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartoletti R, Gavazzi A, Cai T, et al. Prostate growth and prevalence of prostate diseases in early onset spinal cord injuries. Eur Urol. 2009;56(1):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pannek J, Berges RR, Cubick G, Meindl R, Senge T. Prostate size and PSA serum levels in male patients with spinal cord injury. Urology. 2003;62(5):845–848. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00654-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pramudji CK, Mutchnik SE, DeConcini D, Boone TB. Prostate cancer screening with prostate specific antigen in spinal cord injured men. J Urol. 2002;167(3):1303–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexandrino AP, Rodrigues MA, Matsuo T. Evaluation of serum and seminal levels of prostate specific antigen in men with spinal cord injury. J Urol. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2230–2232. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125241.77517.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbonetti A, D’Andrea S, Martorella A, Felzani G, Francavilla S, Francavilla F. Risk of prostate cancer in men with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Androl. 2018;20(6):555–560. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_31_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vince RA, Jr, Jiang R, Bank M, et al. Evaluation of social determinants of health and prostate cancer outcomes among black and white patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2250416. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50416. Published 2023 Jan 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith ZL, Eggener SE, Murphy AB. African-American prostate cancer disparities. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18(10):81. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0724-5. Published 2017 Aug 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong SH, Werneburg GT, Abouassaly R, Wood H. Acquired and congenital spinal cord injury is associated with lower likelihood of prostate specific antigen screening. Urology. 2022;164:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2022.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benaim EA, Montoya JD, Saboorian MH, Litwiller S, Roehrborn CG. Characterization of prostate size, PSA and endocrine profiles in patients with spinal cord injuries. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1998;1(5):250–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torricelli FC, Lucon M, Vicentini F, Gomes CM, Srougi M, Bruschini H. PSA levels in men with spinal cord injury and under intermittent catheterization. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(8):1522–1524. doi: 10.1002/nau.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konety BR, Nguyen TT, Brenes G, et al. Evaluation of the effect of spinal cord injury on serum PSA levels. Urology. 2000;56(1):82–86. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee WY, Sun LM, Lin CL, et al. Risk of prostate and bladder cancers in patients with spinal cord injury: a populationbased cohort study. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(1):51.e1–51.e517. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel N, Ngo K, Hastings J, Ketchum N, Sepahpanah F. Prevalence of prostate cancer in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. PM R. 2011;3(7):633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Everaert K, Oostra C, Delanghe J, Vande Walle J, Van Laere M, Oosterlinck W. Diagnosis and localization of a complicated urinary tract infection in neurogenic bladder disease by tubular proteinuria and serum prostate specific antigen. Spinal Cord. 1998;36(1):33–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drazer MW, Huo D, Eggener SE. National prostate cancer screening rates after the 2012 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation discouraging prostate-specific antigen-based screening. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(22):2416–2423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sammon JD, Abdollah F, Choueiri TK, et al. Prostate-specific antigen screening after 2012 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. JAMA. 2015;314(19):2077–2079. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemal A, Fedewa SA, Ma J, et al. Prostate cancer incidence and PSA testing patterns in relation to USPSTF screening recommendations. JAMA. 2015;314(19):2054–2061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.14905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vetterlein MW, Dalela D, Sammon JD, et al. State-bystate variation in prostate-specific antigen screening trends following the 2011 United States Preventive Services Task Force panel update. Urology. 2018;112:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]