Abstract

Background

Several studies have reported the association between pure hypercholesterolemia (PH) and psoriasis, but the causal effect remains unclear.

Methods

We explored the causal effect between PH and psoriasis using two‐sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis using data from genome‐wide association studies. Single nucleotide polymorphisms related with exposures at the genome‐wide significance level (p < 5×10–8) and less than the linkage disequilibrium level (r 2 < 0.001) were chosen as instrumental variables. Subsequently, we used inverse variance weighting (IVW), MR‐Egger and weighted median (WM) methods for causal inference. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity was tested using Cochran's Q‐test, and horizontal pleiotropy was examined using the MR‐Egger intercept. Leave‐one‐out analyses were performed to assess the robustness and reliability of the results.

Results

MR results showed a positive causal effect of PH on psoriasis [IVW: odds ratios (OR): 1.139, p = 0.032; MR‐Egger: OR: 1.434, p = 0.035; WM: OR: 1.170, p = 0.045] and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (IVW: OR: 1.210, p = 0.049; MR‐Egger regression: OR: 1.796, p = 0.033; WM: OR: 1.317, p = 0.028). However, there is no causal relationship between PH and psoriasis vulgaris as well as other unspecified psoriasis. Inverse MR results suggested a negative causal relationship between PsA and PH (IVW: OR: 0.950, p = 0.037). No heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy exist, and these results were confirmed to be robust.

Conclusion

PH has a positive casual effect on psoriasis and PsA, and PsA may reduce the risk of having PH.

Keywords: Mendelian randomization, psoriasis, psoriasis arthritis, psoriasis vulgaris, pure hypercholesterolemia

1. INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease with erythema, papules and scaling as the main manifestations. 1 It is basically characterized by excessive and abnormal proliferation of keratinocytes. 2 Psoriasis can occur worldwide, at any age, though it is more common in adults than children. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Psoriasis is associated with many diseases, such as psychiatric disorders, cardiometabolic diseases, diabetes mellitus, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, etc. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 There are a number of studies that utilize genetic techniques to evaluate a role of various comorbidities in psoriasis. 11 Infection, vaccine injection, smoking, alcohol consumption, mental stress, and other factors may all contribute to psoriasis flare‐ups and worsening. 12 Psoriasis is prone to recurrence and there are no effective clinical cure methods, imposing a huge burden to patients' physiological and psychosocial health as well as their economic conditions, and seriously reduces their quality of life. 13 , 14 Despite the fact that a large number of scientists have dedicated themselves to the research of psoriasis, the pathogenesis remains unknown. As a result, it is essential to explore potential causes of psoriasis that might guide therapy.

Pure hypercholesterolemia (PH) is a clinical feature of dyslipidemia that is generally recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. 15 , 16 Cholesterol metabolism is an important bio‐metabolic process in the body and has been linked to the development of autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) as well as psoriasis. 17 Several studies have suggested that the prevalence of PH is significantly higher in psoriasis patients than in controls. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 In addition, a cohort study discovered that PH increases the risk of psoriasis. 22 Quite a few studies have identified the association between PH and psoriasis, but the causal relationship and potential mechanisms of action between the two remain unclear limited by the properties of previous studies and the presence of various biases.

The Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is a method in epidemiology that uses genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to investigate the causal relationship between exposure and outcome. 23 It is extremely similar to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Since genes are naturally and randomly assigned during meiosis and largely unaffected by acquired environmental factors, 24 , 25 MR method has the advantages of avoiding potential confounding factors and reverse causality compared to traditional observational studies and RCTs, and is now widely used. This study conducted a two‐sample bidirectional MR analysis using the genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) publicly available dataset to explore the causal relationship between PH and psoriasis and some of its subtypes.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

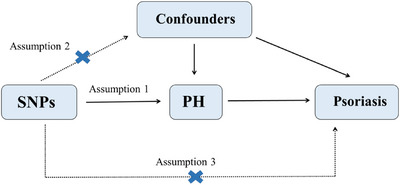

We used a two‐sample bidirectional MR analysis to estimate the causal relationships between exposures and outcomes. A genetic variant can be regarded as an effective IV for exposure when it meets three core assumptions: 1) single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) should be strongly associated with the exposure; 2) SNPs should be independent of confounders; 3) SNPs must affect outcomes only through exposure and not through direct correlation, 26 as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study design. Three assumptions in MR analysis.

In order to determine whether there is a reverse relationship between them, we also looked at the reverse causal effect in the MR analyses using PH as the outcome and psoriasis as the exposure.

2.2. Data sources

The data used in MR analysis were retrieved from the FinnGen biobank by IEU OpenGWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). Table 1 displays data information for PH, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), psoriasis vulgaris, other and unspecific psoriasis, including IEU GWAS ID, sample size, etc.

TABLE 1.

Summary of genome‐wide association studies.

| GWAS data | IEU GWAS ID | Source | Sample size | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | finn‐b‐E4_HYPERCHOL | FinnGen biobank | 206 067 | European |

| Psoriasis | finn‐b‐L12_PSORIASIS | FinnGen biobank | 216 752 | European |

| PsA | finn‐b‐L12_PSORI_ARTHRO | FinnGen biobank | 213 879 | European |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | finn‐b‐L12_PSORI_VULG | FinnGen biobank | 215 044 | European |

| Other and unspecified psoriasis | finn‐b‐L12_PSORI_NAS | FinnGen biobank | 212 996 | European |

PH, pure hypercholesterolemia; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

2.3. Instrumental variables selection

In this study, we first extracted the SNPs intensely related with exposures at the genome‐wide significance level (p < 5×10−8) to be the IVs. Next, since strong linkage disequilibrium between IVs leads to biased estimations, only thresholds satisfying the clumping window size > 10 000 kb and less than the linkage disequilibrium level (r 2 < 0.001) were left. Moreover, because the exposed variants with low minor allele frequencies (MAF) would have lower causal estimation precision, we set the value of MAF to be greater than 0.05. F statistic was applied to ensure a strong association between IVs and exposure, and weak IVs were excluded to reduce bias in cases where F statistic value was less than 10.0. F statistic was calculated as follow:

where N is the sample size of exposure and K is the number of SNPs. R 2 is the proportion of exposure explained by IVs and was calculated using the following formula:

where EAF is the effect allele frequency, beta is the estimated genetic effect on exposure, Ν is the sample size, and SE is the standard error of the genetic effect.

In addition, SNPs with palindromic sequences were also excluded to guarantee that the effects of SNPs on exposure and outcome corresponding to the same allele. For the PH‐associated SNPs that were not available in the exposure datasets, a proxy SNP (r 2 > 0.8) was chosen. In order to satisfy the assumption 3, a phenome‐wide association study (PheWAS) was performed to exclude SNPs related to exposure.

The IVs screening process for reverse MR analysis is the same, with the difference being the swapping of exposure and outcome locations.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used three methods to perform the causality analysis between PH and psoriasis as well as some of its subtypes. The most effective test is inverse variance weighting (IVW) method, which combines the Wald ratios between each SNP and the outcome to calculate the combined causal effect by aggregating the data, and its overall bias is zero when all IVs are valid, so we used it as the main analysis method. 27 Otherwise, MR‐Egger and weighted median (WM) methods were also presented as complementary methods since they can provide reliable estimations in a wider range of situations. As for the MR‐Egger regression, it allows for the presence of a non‐zero intercept, which provides unbiased estimations even if all IVs are invalid. 28 , 29 The WM method requires at least 50% of the information comes from a valid SNP to give a consistent effect estimation. 30

The intercept of MR‐Egger regression was used to test for horizontal pleiotropy. 31 Cochran's Q test was used to determine whether heterogeneity existed in each SNP causal estimation in IVW and MR‐Egger. In addition, to verify the stability and reliability of the MR results, we performed leave‐one‐out sensitivity analysis to further confirm whether a single SNP would have a significant effect on the results. We considered the results statistically significant when p < 0.05.

To explore whether psoriasis and some of its subtypes have any causal effect on PH, we also performed reverse MR analyses using SNPs associated with psoriasis and its subtypes as IVs. (That is, psoriasis, PsA, psoriasis vulgaris, other and unspecified psoriasis are used as exposures respectively, and PH is used as the outcome).

All statistical analyses in this study were performed by the “TwosampleMR” package in the R (version 4.2.1) software, and no additional ethical approval was required because the data we used were publicly available.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Selection of instrumental variables

Sixteen SNPs are preliminarily screened to ensure a robust association with PH (p < 5 × 10−8) and less than the linkage disequilibrium level (r 2 < 0.001). After setting MAF > 0.05 and removing weak IVs (F > 10.0), five SNPs (rs11591147, rs149603090, rs77645768, rs182695896, rs117733303) were excluded from our study. At the same time, two palindrome SNPs (rs115478735, rs964184) were also eliminated. Eventually, nine SNPs for PH were obtained (Table S1). Besides, we verified manually by PheWAS that they were not potentially associated with the outcome “psoriasis”. These SNPs will be used as IVs to explore the relationship between PH and psoriasis.

In the reverse MR study, we used the same screening process described above to explore the effect of psoriasis and its subtypes on susceptibility to PH. We obtained 11 SNPs associated with psoriasis, four with PsA, six with psoriasis vulgaris, and three with other and unspecified psoriasis as IVs respectively, the detailed results of SNPs were shown in Table S2‐5.

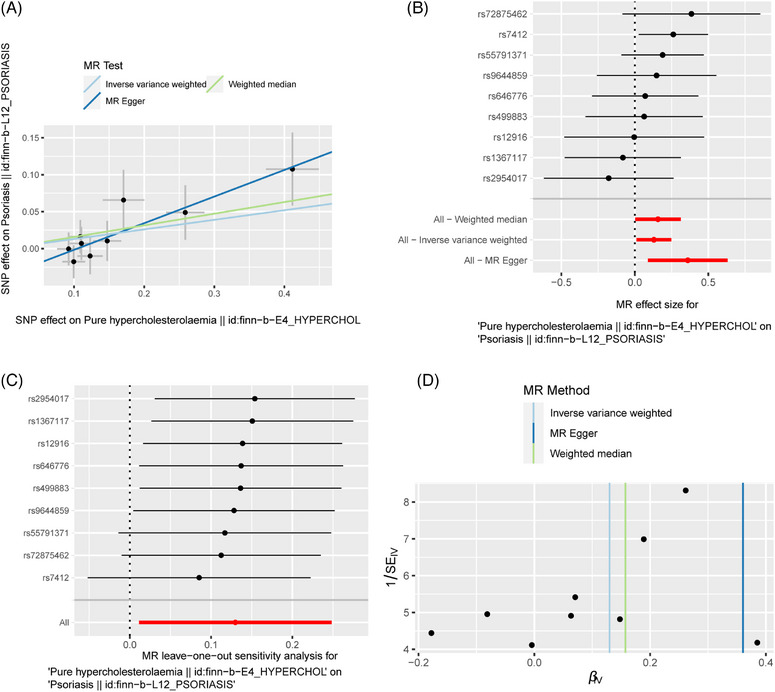

3.2. Causal effects of PH on psoriasis

The MR results of PH on psoriasis are listed in Table 2 and Figure 2. IVW method suggested that PH has a positive causal effect on psoriasis (OR: 1.139; 95% CI: 1.011‐1.282; p = 0.032). MR‐Egger (OR: 1.434; 95% CI: 1.093‐1.881; p = 0.035) and WM (OR: 1.170; 95% CI: 1.003‐1.365; p = 0.045) methods also reach the same results. According to Cochran's Q test, there is no heterogeneity (IVW:Q = 5.995, p = 0.648;MR‐Egger: Q = 2.568, p = 0.922), and MR‐Egger intercept indicates no horizontal pleiotropy (MR‐Egger intercept = −0.038; SE = 0.020; p = 0.107) (Table 3). To examine the stability and reliability of the results, the leave‐one‐out analysis was performed, showing that MR results do not fluctuate significantly as individual SNP excluded (Figure 2C).

TABLE 2.

The results of MR analyses and reverse MR analyses.

| Exposure | Outcome | MR method | No. of SNPs | OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | Psoriasis | IVW | 9 | 1.139 (1.011–1.282) | 0.032 |

| MR‐Egger | 9 | 1.434 (1.093–1.881) | 0.035 | ||

| WM | 9 | 1.170 (1.003–1.365) | 0.045 | ||

| PsA | IVW | 9 | 1.210 (1.001–1.462) | 0.049 | |

| MR‐Egger | 9 | 1.796 (1.166–2.766) | 0.033 | ||

| WM | 9 | 1.317 (1.030–1.683) | 0.028 | ||

| Psoriasis vulgaris | IVW | 9 | 1.110 (0.985–1.287) | 0.164 | |

| MR‐Egger | 9 | 1.383 (0.986–1.939) | 0.102 | ||

| WM | 9 | 1.126 (0.934–1.356) | 0.213 | ||

| Other and unspecified psoriasis | IVW | 9 | 1.186 (0.871–1.615) | 0.280 | |

| MR‐Egger | 9 | 0.939 (0.452–1.952) | 0.870 | ||

| WM | 9 | 1.080 (0.747–1.563) | 0.682 | ||

| Psoriasis | PH | IVW | 11 | 0.992 (0.947–1.038) | 0.719 |

| MR‐Egger | 11 | 0.988(0.918–1.064) | 0.765 | ||

| WM | 11 | 0.990 (0.936–1.048) | 0.736 | ||

| PsA | PH | IVW | 4 | 0.950 (0.906–0.997) | 0.037 |

| MR‐Egger | 4 | 0.872 (0.725–1.048) | 0.281 | ||

| WM | 4 | 0.949 (0.896–1.004) | 0.067 | ||

| Psoriasis vulgaris | PH | IVW | 6 | 0.956 (0.905–1.010) | 0.108 |

| MR‐Egger | 6 | 0.947 (0.849–1.056) | 0.381 | ||

| WM | 6 | 0.957 (0.912–1.004) | 0.074 | ||

| Other and unspecified psoriasis | PH | IVW | 3 | 00.984 (0.949–1.020) | 0.372 |

| MR‐Egger | 3 | 0.986 (0.910–1.069) | 0.794 | ||

| WM | 3 | 0.985 (0.957–1.014) | 0.299 |

CI, confidence interval; IVW, inverse variance weighting method; PH, pure hypercholesterolemia; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; OR, odds ratio; SNPs, single‐nucleotide polymorphisms; WM, weighted median.

FIGURE 2.

The MR result of the causal effect of PH on psoriasis. (A) Scatter plot about the causal effect of PH on psoriasis. (B) Forest plot for the overall causal effects of PH on psoriasis. (C) Leave‐one‐out analysis for the causal effect of PH on psoriasis. (D) Funnel plot of SNPs related to PH and psoriasis.

TABLE 3.

The results of sensitivity analysis.

| Cochran's Q test | Pleiotropy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Outcome | IVW | MR‐Egger | MR‐Egger intercept | se | p | |

| PH | Psoriasis | Q | 5.995 | 2.568 | ‐0.038 | 0.020 | 0.107 |

| p | 0.648 | 0.922 | |||||

| PsA | Q | 6.280 | 2.307 | ‐0.065 | 0.032 | 0.086 | |

| p | 0.616 | 0.941 | |||||

| Psoriasis vulgaris | Q | 3.712 | 1.716 | ‐0.036 | 0.025 | 0.201 | |

| p | 0.882 | 0.974 | |||||

| Other and unspecified psoriasis | Q | 10.144 | 9.490 | 0.038 | 0.055 | 0.509 | |

| p | 0.255 | 0.219 | |||||

| Psoriasis | PH | Q | 9.248 | 9.237 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.918 |

| p | 0.509 | 0.416 | |||||

| PsA | PH | Q | 1.546 | 0.642 | 0.039 | 0.041 | 0.442 |

| p | 0.672 | 0.726 | |||||

| Psoriasis vulgaris | PH | Q | 8.894 | 8.795 | 0.005 | 0.234 | 0.843 |

| p | 0.113 | 0.066 | |||||

| Other and unspecified psoriasis | PH | Q | 4.032 | 4.006 | ‐0.004 | 0.045 | 0.949 |

| p | 0.133 | 0.045 | |||||

IVW, inverse variance weighting method; PH, pure hypercholesterolemia; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

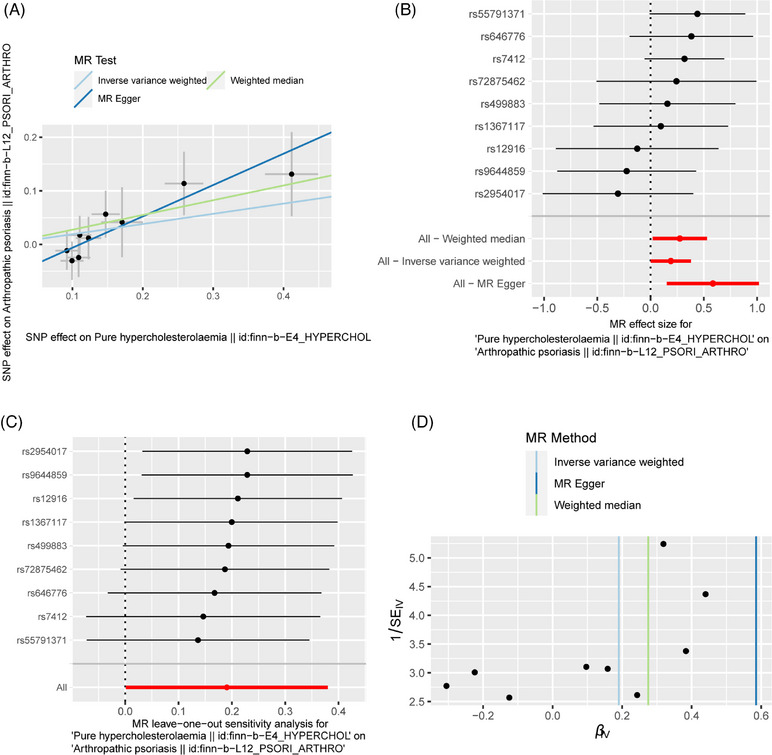

3.3. Causal effects of PH on PsA

As presented in the Table 2 and Figure 3, the IVW (OR: 1.210; 95% CI: 1.001‐1.462; p = 0.049), MR‐Egger regression (OR: 1.796; 95% CI: 1.166‐2.766; p = 0.033) and WM (OR: 1.317; 95% CI: 1.030‐1.683; p = 0.028) methods all concluded a positive relationship between PH and PsA. Sensitivity analysis did not reveal the presence of heterogeneity (IVW: Q = 6.280, p = 0.616; MR‐Egger: Q = 2.307, p = 0.941) and pleiotropy (MR‐Egger intercept = −0.065; SE = 0.032; p = 0.086) (Table 3). Leave‐one‐out analysis indicated that the results were very stable and reliable (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

The MR result of the causal effect of PH on PsA. (A) Scatter plot about the causal effect of PH on PsA. (B) Forest plot for the overall causal effects of PH on PsA. (C) Leave‐one‐out analysis for the causal effect of PH on PsA. (D) Funnel plot of SNPs related to PH and PsA.

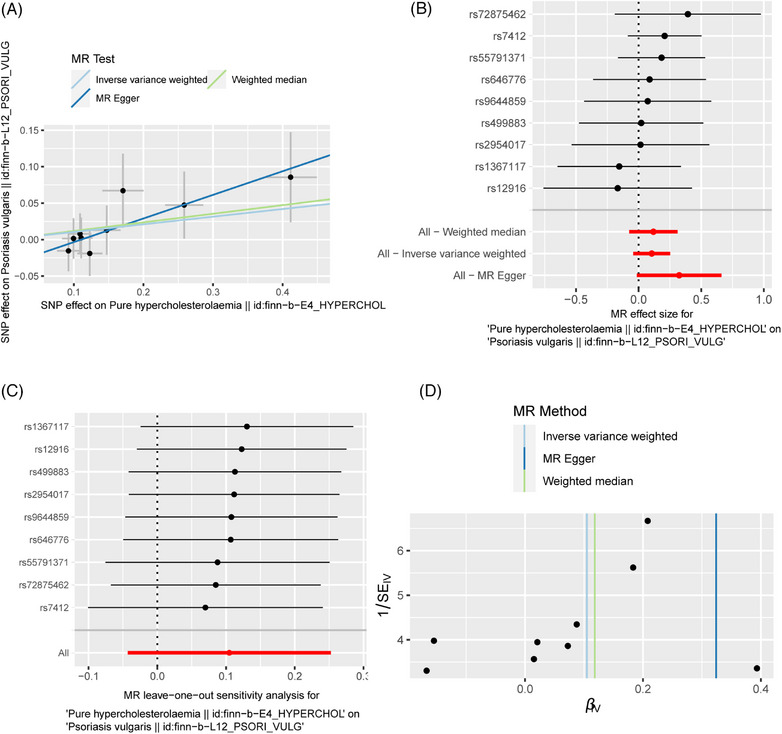

3.4. Causal effects of PH on psoriasis vulgaris

Our findings suggested that there was no causal relationship between PH and psoriasis vulgaris, with the IVW (OR: 1.110; 95% CI: 0.985‐1.287; p = 0.164), MR‐Egger regression (OR: 1.383; 95% CI: 0.986‐1.939; p = 0.102) and WM (OR: 1.126; 95% CI: 0.934‐1.356; p = 0.213) methods all yielded consistent results, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 4. Cochran's Q test showed no heterogeneity (IVW: Q = 3.712, p = 0.882; MR‐Egger: Q = 1.716, p = 0.974). What is more, no pleiotropy was observed (MR‐Egger intercept = −0.036; SE = 0.025; p = 0.201) (Table 3). Leave‐one‐out analysis indicated that the results were reliable (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

The MR result of the causal effect of PH on psoriasis vulgaris. (A) Scatter plot about the causal effect of PH on psoriasis vulgaris. (B) Forest plot for the overall causal effects of PH on psoriasis vulgaris. (C) Leave‐one‐out analysis for the causal effect of PH on psoriasis vulgaris. (D) Funnel plot of SNPs related to PH and psoriasis vulgaris.

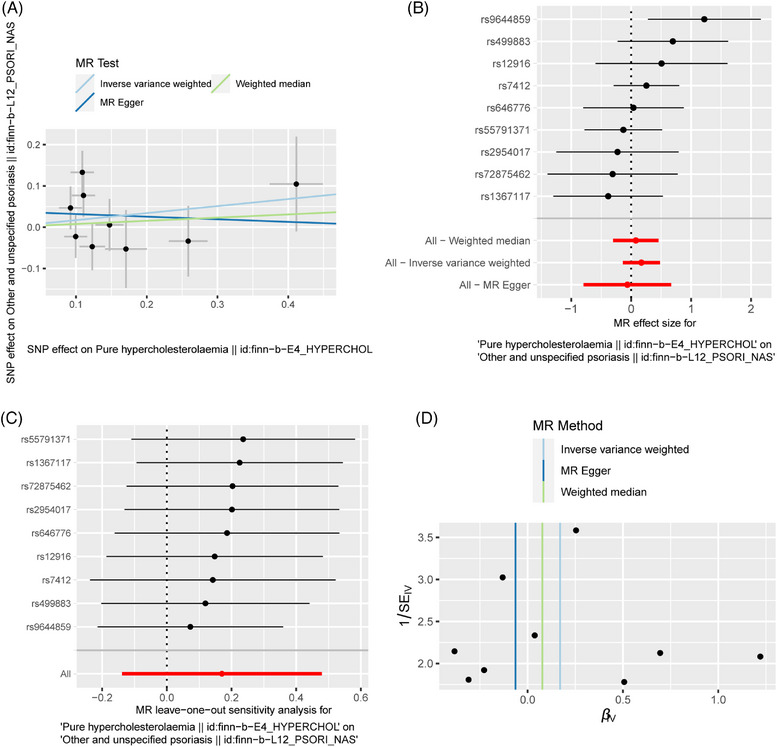

3.5. Causal effects of PH on other unspecified psoriasis

As regards PH and other unspecified psoriasis, the IVW (OR: 1.186; 95% CI: 0.871‐1.615; p = 0.280), MR‐Egger regression (OR: 0.939; 95% CI: 0.452‐1.952; p = 0.870) and WM (OR: 1.080; 95% CI: 0.747‐1.563; p = 0.682) methods all endorsed that there was no causal relationship between them (Table 2; Figure 5). Moreover, no heterogeneity (IVW: Q = 10.144, p = 0.255; MR‐Egger: Q = 9.490, p = 0.219) and pleiotropy (MR‐Egger intercept = 0.038; SE = 0.055; p = 0.509) were found (Table 3). We performed the leave‐one‐out analysis and found that the causal relationship between PH and other undifferentiated psoriasis was not influenced by individual SNP (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

The MR result of the causal effect of PH on other unclassified psoriasis. (A) Scatter plot about the causal effect of PH on other unclassified psoriasis. (B) Forest plot for the overall causal effects of PH on other unclassified psoriasis. (C) Leave‐one‐out analysis for the causal effect of PH on other unclassified psoriasis. (D) Funnel plot of SNPs related to PH and other unclassified psoriasis.

3.6. Reverse MR analysis

To assess whether there were some reverse causalities, we also performed reverse MR analyses. Psoriasis, PsA, psoriasis vulgaris and other unclassified psoriasis were designated as exposures, while PH was designated as the outcome. The results showed that there were no reverse causal effects between psoriasis, psoriasis vulgaris, other unspecified psoriasis and PH (Table 2; Figure S1, 8–9). IVW method suggests that PsA is a protective factor for PH(OR: 0.950; 95% CI: 0.906‐0.997; p = 0.037), however, MR‐Egger regression (OR: 0.872; 95% CI: 0.725‐1.048; p = 0.281) and WM (OR: 0.949; 95% CI: 0.896‐1.100; p = 0.067) methods did not indicate any association between them (Table 2; Figure S2). Sensitivity analyses for each group of studies did not suggest the presence of pleiotropy or heterogeneity (Table 3), and leave‐one‐out analyses supported the stability of the results (Figure S1C, S2C, S3C, S4C).

4. DISCUSSION

We investigated the causal relationship between PH and psoriasis and some of its subtypes using MR analysis. We found PH may be a risk factor for psoriasis and PsA, but there is no association between PH and psoriasis vulgaris as well as other unspecified psoriasis. By performing reverse MR analyses, we found that PsA may reduce the risk of having PH, while psoriasis, psoriasis vulgaris, other and unspecified psoriasis may not.

Psoriasis is an immune‐mediated systemic inflammatory disease. PsA is the more clinically severe subtype of psoriasis, and psoriasis vulgaris is the most common type of psoriasis in clinical practice. The prevalence of PsA is 0.05‐0.25% in the whole population. 32 About one‐third of those with psoriasis will eventually progress to PsA. It is characterized by extensive muscle and bone involvement, and many patients also develop destructive arthritis with other serious complications and disabilities. 33 There are no specific clinical diagnostic criteria for PsA. It is diagnosed mostly through clinical manifestations and testing negative for rheumatoid factor (RF) and cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies. 34 Currently, psoriasis is difficult to achieve a clinical cure and is prone to recurrence. Thus, exploring the mechanisms of psoriasis pathogenesis can help us better understand the disease and identify novel strategies for therapy.

Several studies found that total cholesterol levels were statistically elevated in psoriasis patients compared to healthy controls. 35 , 36 According to a prospective cohort study, PH increased the risk of psoriasis and PsA, especially in those with a long course of hypercholesterolemia (≥7 years). 22 However, some studies suggested that no significant differences in total plasma cholesterol in patients with psoriasis compared to controls. 37 , 38 , 39 For example, a study reported that patients with psoriasis in the exacerbation state had increased plasma total cholesterol markedly in crude comparison, but not after adjustment for confounders. 40 We drew the same conclusions through MR analyses, that is, PH increased the risk of psoriasis and PsA, while there were no reverse causal effects between psoriasis and PH. As for the casual relationship of PsA and PH, many studies tend to consider PsA as a risk factor for PH currently. The incidence of PH was observed to be significantly higher in patients with PsA, 41 and a study mentioned PsA was associated with the incidence and prevalence of dyslipidemia, and this relationship was more significant than in other inflammatory arthritis such as RA. 42 Nevertheless, one study found that total serum cholesterol levels were lower in patients with PsA than in controls, which is consistent with our finding that PsA is a protective factor for PH. 43 As for psoriasis vulgaris, a cross‐sectional study reported that it was a risk factor for PH and was not associated with the presence of PsA and duration or severity of psoriasis. 44 Nevertheless, another case report of a 35‐year‐old patient with psoriasis vulgaris showed elevated total cholesterol levels after intravenous antitumor necrosis factor‐alpha therapy, based on this case report it can be hypothesized that psoriasis vulgaris may have the potential to decrease cholesterol levels. 45 In our study, we found no causal relationship between psoriasis vulgaris and PH. The reasons for the differences can be explained from two aspects. One is that the small number of SNPs screened in our study led to statistical bias, and the other is that previous observational studies were influenced by confounding factors (selection bias, information bias, confounding bias, etc.), which cannot well reflect the true association between exposures and outcomes. We also hypothesize that the different relationship between PH and PsA/psoriasis vulgaris may be related to the genetic background difference of the two diseases. Due to genotypic differences in the HLA region, PsA and psoriasis vulgaris exist different disease heterogeneity. 34 A thorough study is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Besides, we suggested that there is no causal relationship between PH and other unspecified psoriasis for the first time in our study, but more studies are necessary to support our finding due to the vague definition of other unspecified psoriasis in clinical practice.

Since many inflammatory cytokines enrolled in psoriasis, we sought to further elucidate the role of PH in psoriasis from the lipid metabolism and inflammation point of view. Numerous studies have revealed that psoriasis belongs to the helper T cell (Th) 1 type immune responses. Activated Th1 and Th17 immune cells, as well as excessive levels of inflammatory cytokines including interferon (IFN)‐α, IFN‐γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐17, IL‐22, IL‐12/IL‐23, chemokines and antimicrobial peptides, all play a significant part in the condition and may be related to the severity of the disease. 46 , 47 Currently, biologics targeting IL‐17, IL‐23 and TNF‐α have been shown to have powerful efficacy in moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA. 48 , 49 , 50 Interestingly, TNF‐α and IL‐17 has been shown to affect cholesterol and lipid metabolism, and PH can activate T lymphocytes in psoriasis. 15 Cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthetic programs are upregulated during the differentiation of Th17. 51 In particular, the study by Pallavi Varshney et al. revealed that high levels of intracellular cholesterol play a role in intracellular IL‐17A signaling. 52 Cholesterol‐lowering treatments such as low‐fat diets or statins have also been proven to be associated with clinical improvement of psoriasis. 53 , 54 In combination with our findings, we can assume that PH may be involved in the activation of the Th17 pathway and thus affect the onset and progression of psoriasis. The exact potential mechanism of action needs to be further confirmed. However, the specific mechanism by which PsA has a protective effect on PH as found in this study needs to be determined by further studies.

Our study has several advantages. First, multiple types of previous studies have pointed to an association between PH and psoriasis, but little has been mentioned about the relationship between PH and different subtypes of psoriasis. In addition to psoriasis, our study provides an in‐depth analysis of the causal relationship between PH and psoriasis vulgaris and PsA. First, we describe the absence of an association between PH and PsA, psoriasis vulgaris as well as other and unspecified psoriasis for the first time. Second, MR analysis used in our study can effectively overcome the bias introduced by unmeasured confounders, and by using genetic variation as an instrumental variable, we will have sufficient certainty to test for causality, which is more convincing compared to observational studies. Additionally, the subjects included in this study were all European populations, which minimizes potential bias due to population stratification.

Our study also has some limitations. First, our study selected data from European ancestry sources and therefore cannot be immediately generalized to all human races because of the variation in the incidence and characteristics of psoriasis in different ethnic groups. Second, hyperlipidemia includes hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and mixed hyperlipidemia. Cholesterol contains high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) and low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), since GWAS database did not contain dataset related to them, we were not in a position to perform further analyses to compare the various subtypes of hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, we have not studied some other subtypes of psoriasis, such as pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis, due to the lack of the data in the GWAS database.

5. CONCLUSION

This MR study supports a strong positive relationship between PH and psoriasis, PsA, while endorsing PsA as a protective factor for PH. It also suggests that there is no causal relationship between PH and psoriasis vulgaris and other unclassified psoriasis. This study may provide new insights into the role of PH in psoriasis pathogenesis and shed light on the prevention and treatment of psoriasis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the IEU OpenGWAS project for providing the data.

Bai E, Ren L, Guo J, Xian N, Luo R, Chang Y, et al. The causal relationship between pure hypercholesterolemia and psoriasis: A bidirectional, two‐sample Mendelian randomization study. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29:e13533. 10.1111/srt.13533

Ruimin Bai, Landong Ren and Jiaqi Guo contributed equally to this work and should be considered co‐first authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are publicly available from the IEU OpenGWAS project (http://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/).

REFERENCES

- 1. Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983‐994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii18‐23. discussion ii24‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Psoriasis Barker J.. Psoriasis Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301‐1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Green AC. Australian Aborigines and psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 1984;25(1):18‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lomholt G. Prevalence of skin diseases in a population; a census study from the Faroe Islands. Dan Med Bull. 1964;11:1‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945‐1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li WQ, Han JL, Manson JE, et al. Psoriasis and risk of nonfatal cardiovascular disease in U.S. women: a cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(4):811‐818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(3):425‐440.e2 e422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korman NJ. Management of psoriasis as a systemic disease: what is the evidence? Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(4):840‐848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xian N, Bai R, Guo J, et al. Bioinformatics analysis to reveal the potential comorbidity mechanism in psoriasis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(9):e13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Risk factors for the development of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(2):236‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi J, Koo JY. Quality of life issues in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 Suppl):S57‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stokes KY. Microvascular responses to hypercholesterolemia: the interactions between innate and adaptive immune responses. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(7‐8):1141‐1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matwiejuk M, Mysliwiec H, Jakubowicz‐Zalewska O, Chabowski A, Flisiak I. Effects of hypolipidemic drugs on psoriasis. Metabolites. 2023;13(4):493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ryu H, Kim J, Kim D, Lee JE, Chung Y. Cellular and molecular links between autoimmunity and lipid metabolism. Mol Cells. 2019;42(11):747‐754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kimhi O, Caspi D, Bornstein NM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of atherosclerosis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(4):203‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gyldenlove M, Jensen P, Linneberg A, et al. Psoriasis and the Framingham risk score in a Danish hospital cohort. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(9):1086‐1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu Y, Mills D, Bala M. Psoriasis: cardiovascular risk factors and other disease comorbidities. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(4):373‐377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piskin S, Gurkok F, Ekuklu G, Senol M. Serum lipid levels in psoriasis. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44(1):24‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu S, Li WQ, Han J, Sun Q, Qureshi AA. Hypercholesterolemia and risk of incident psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in US women. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2014;66(2):304‐310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wehby GL, Ohsfeldt RL, Murray JC. ‘Mendelian randomization’ equals instrumental variable analysis with genetic instruments. Stat Med. 2008;27(15):2745‐2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan S. Mendelian randomization JAMA. 2017;318(19):1925‐1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hartwig FP, Borges MC, Horta BL, Bowden J, Davey Smith G. Inflammatory biomarkers and risk of schizophrenia: a 2‐sample Mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1226‐1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boef AG, Dekkers OM, le Cessie S. Mendelian randomization studies: a review of the approaches used and the quality of reporting. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):496‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartwig FP, Davies NM, Hemani G, Davey Smith G. Two‐sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1717‐1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Assessing the suitability of summary data for two‐sample Mendelian randomization analyses using MR‐Egger regression: the role of the I2 statistic. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1961‐1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR‐Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(5):377‐389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted Median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304‐314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512‐525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545‐568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):957‐970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. FitzGerald O, Ogdie A, Chandran V, et al. Psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bajaj DR, Mahesar SM, Devrajani BR, Iqbal MP. Lipid profile in patients with psoriasis presenting at Liaquat University Hospital Hyderabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59(8):512‐515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vanizor Kural B, Orem A, Cimsit G, Yandi YE, Calapoglu M. Evaluation of the atherogenic tendency of lipids and lipoprotein content and their relationships with oxidant‐antioxidant system in patients with psoriasis. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;328(1‐2):71‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uyanik BS, Ari Z, Onur E, Gunduz K, Tanulku S, Durkan K. Serum lipids and apolipoproteins in patients with psoriasis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40(1):65‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Toker A, Kadi M, Yildirim AK, Aksoy H, Akcay F. Serum lipid profile paraoxonase and arylesterase activities in psoriasis. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27(3):176‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Farshchian M, Zamanian A, Farshchian M, Monsef AR, Mahjub H. Serum lipid level in Iranian patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(6):802‐805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mallbris L, Granath F, Hamsten A, Stahle M. Psoriasis is associated with lipid abnormalities at the onset of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(4):614‐621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Papadavid E, Katsimbri P, Kapniari I, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis and its correlates among patients with psoriasis in Greece: results from a large retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):1749‐1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karmacharya P, Ogdie A, Eder L. Psoriatic arthritis and the association with cardiometabolic disease: a narrative review. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2021;13:1759720X2199827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tam LS, Tomlinson B, Chu TT, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with psoriatic arthritis compared to controls–the role of inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):718‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santos‐Juanes J, Coto‐Segura P, Fernandez‐Vega I, Armesto S, Martinez‐Camblor P. Psoriasis vulgaris with or without arthritis and independent of disease severity or duration is a risk factor for hypercholesterolemia. Dermatology. 2015;230(2):170‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Antoniou C, Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Stratigos AJ. Elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels after intravenous antitumour necrosis factor‐alpha therapy in a patient with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(5):1090‐1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lowes MA, Suarez‐Farinas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:227‐255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takahashi H, Tsuji H, Hashimoto Y, Ishida‐Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Serum cytokines and growth factor levels in Japanese patients with psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(6):645‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti‐interleukin‐17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137‐1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti‐interleukin‐17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1190‐1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu JJ. Anti‐interleukin‐17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):274‐275. author reply 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1327‐1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Varshney P, Narasimhan A, Mittal S, Malik G, Sardana K, Saini N. Transcriptome profiling unveils the role of cholesterol in IL‐17A signaling in psoriasis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aktas O, Waiczies S, Smorodchenko A, et al. Treatment of relapsing paralysis in experimental encephalomyelitis by targeting Th1 cells through atorvastatin. J Exp Med. 2003;197(6):725‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shirinsky IV, Shirinsky VS. Efficacy of simvastatin in plaque psoriasis: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(3):529‐531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available from the IEU OpenGWAS project (http://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/).