Abstract

The Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP) aims to create a spatial atlas of the healthy human body at single cell resolution by applying advanced technologies and disseminating resources to the community. As HuBMAP moves past its first phase creating ontologies, protocols, and pipelines, this Perspective introduces the production phase: to generate reference spatial maps of functional tissue units across many organs from diverse populations and create mapping tools and infrastructure to advance biomedical research.

Introduction

The Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP) was founded with the goal of establishing state-of-the art frameworks for building spatial multiomic maps of non-diseased human organs at single-cell resolution1. During the first phase (2018–2022), the priorities of the project included validation and development of assay platforms, workflows for data processing, management, exploration, and visualization, and establishment of protocols, quality control standards, and standard operating procedures. Extensive infrastructure was established by a coordinated effort among the various HIVE (HuBMAP Integration, Visualization and Engagement) teams, Tissue Mapping Centers, Technology and Tools Development and Rapid Technology Implementation teams and working groups1. Single-cell maps, predominantly consisting of two-dimensional (2D) spatial data as well as data from dissociated cells, were generated for several organs. The HuBMAP data portal https://portal.hubmapconsortium.org was established for open access to the multiple data types2.

The infrastructure was augmented with software tools for tissue data registration, processing, annotation, visualization, cell segmentation and automated annotation of cell types and cellular neighborhoods from spatial data. Computational methods were developed for integrating multiple data types across scales and interpretation3. Standard reference terminology and a Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) spanning anatomical to biomolecular scales were established to ensure interoperability across organs, research groups and consortia4. Guidelines to capture high-quality multiplexed spatial data5 were established including validated panels of cell and structure-specific antibodies6. The first phase produced a large number of manuscripts7 including spatially resolved single cell maps8–13.

The production phase of HuBMAP was launched in the fall of 2022. The focus is on scaling data production spanning diverse biological variables (e.g., age, ethnicity) and deployment and enhancement of analytical, visualization and navigational tools to generate high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) accessible maps of major functional tissue units from >20 organs. This phase involves over 60 institutions and 400 researchers with opportunities for active intra- and inter-consortia collaborations and building a foundational resource for new biological insights and precision medicine. Below, we summarize major accomplishments and challenges encountered from the first phase of HuBMAP and describe the future roadmap of HuBMAP in the production phase and beyond.

Key Resources and Insights from the First Phase of HuBMAP

Data Types, Organs, and Technologies

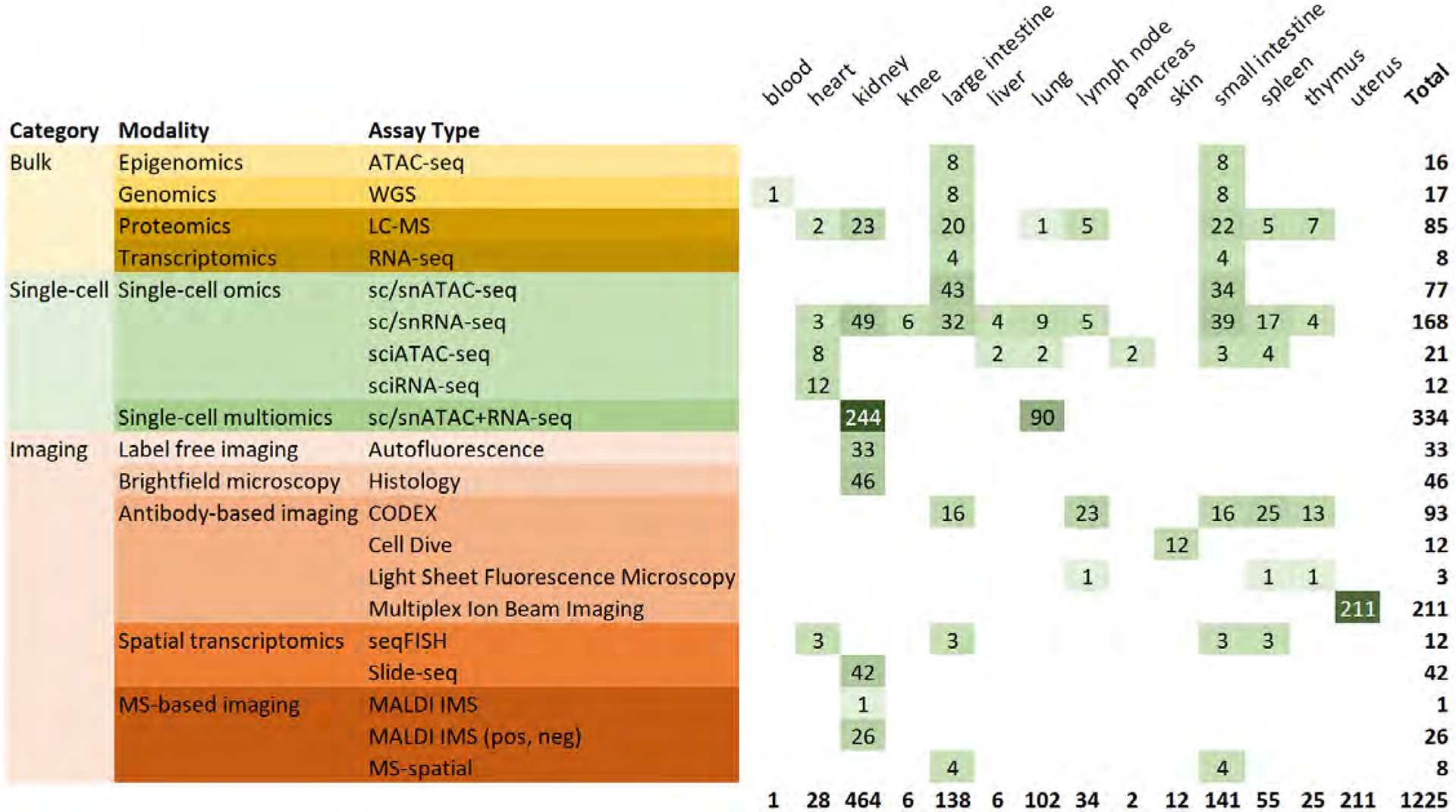

As of Q2 2023, HuBMAP datasets using 18 different analytical technologies or assay types are publicly available (Fig. 1a and Fig. 2). These encompass 1,672 publicly available datasets from regions with no histopathologic abnormality from 14 organs across 180 donors. Protocols were optimized for minimizing ischemia time of healthy donors. All published data are freely available via the HuBMAP Portal, https://portal.hubmapconsortium.org. These assays span spatial scales (from ~100 nm subcellular resolution to ~cm and organ level) and interrogate macromolecules using diverse technologies (Fig. 1 and 2, https://software.docs.hubmapconsortium.org/assays.html). The assays include Single-cell/nucleus transcriptomics and chromatin accessibility mapping (sc/snRNA-seq and ATAC-seq), spatial transcriptomics and proteomics, imaging mass spectrometry (IMS), FISH-based and antibody-based highly multiplexed fluorescence imaging assays as well as bulk tissue assays. Publicly available datasets include 2D or 3D spatially-resolved assays surveying RNA14,15, proteins16, and metabolites (light sheet microscopy17, co-detection by indexing (CODEX)18, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, desorption electrospray ionization, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), and IMS19,20) (Fig. 2).

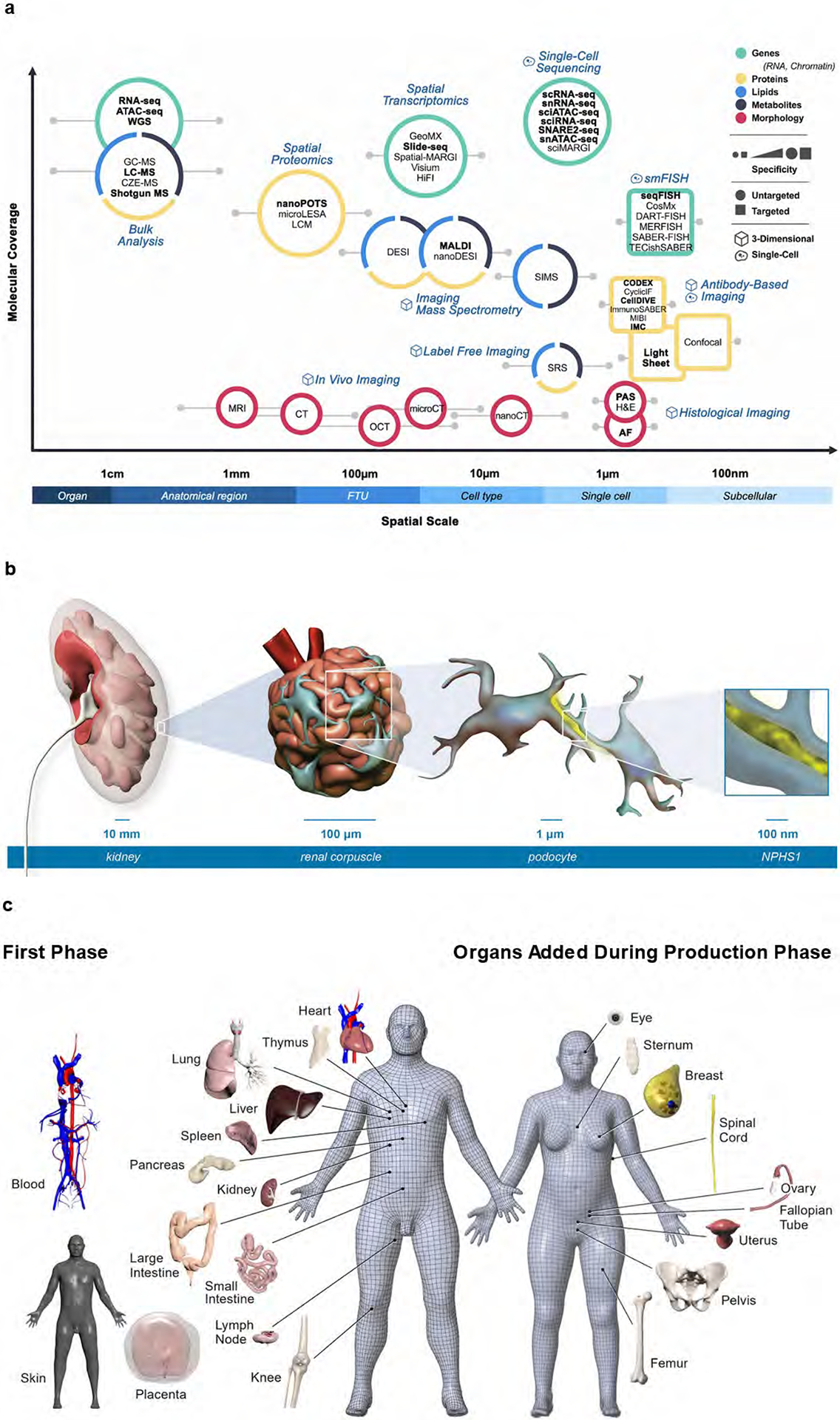

Figure 1. Molecular coverage and spatial scale of different assay types.

About 40 different analytical technologies are used in HuBMAP. a. Molecular coverage versus spatial scale. Data publicly available via the HuBMAP portal is rendered in bold. b. The multi-scale HRA covers more than 1,500 anatomical structures in the male and female body. A zoom into the kidney (10 mm level) reveals a representative view of a renal corpuscle (200 μm level), a subsegment of one of the ca. 1 million FTUs (nephron) of the kidney that is important in filtration. Podocytes, one of the cells important in filtration (μm level) with nucleus (in blue) and protein NPHS1 that maintains the structural integrity of the filtration barrier (yellow) is illustrated. c. Three-dimensional reference objects exist for 53 organs (counting left/right and female/male organs). Shown on left of the 3D reference bodies are female/male organs for which HRA data exists on the HuBMAP Portal, note that placenta is full-term; on right of the reference bodies are female/male organs that will be added during the production phase. The 3D reference organs are used during tissue registration to automatically assign anatomical structure tags and they serve as landmarks during spatial search for tissue datasets with specific anatomical structures, FTUs, cell types, or biomarkers.

Figure 2. Organs and assay types publicly available via HuBMAP portal (as of May 2023).

Organs are sorted alphabetically. Assay types are grouped into bulk, single-cell, and imaging. LC-MS includes Imaging Mass Cytometry (2D), Imaging Mass Cytometry (3D), LC-MS, LC-MS Bottom Up, and LC-MS Top Down. Abbreviations: Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq), Mass Spectrometry (MS), Whole-genome sequencing (WGS).

Detailed 2D single-cell maps have been generated for several organs, including the small and large intestine, kidney, placenta, lymph node, liver, and spleen, and 3D maps exist for skin. Informed consents permit the broad sharing of genomic data with the research community, either through controlled-access databases for raw sequencing files (e.g., the database of genotypes and phenotypes, dbGaP) or completely open access. Data that are not directly identifiable are freely available from the HuBMAP Portal. Extensive metadata are included for each donor, including clinical and epidemiological data, such as sex, race (self-reported), ethnicity, age, lab results, medications, comorbidities, tissue morphology, and processing parameters. The demographics of the donors can be explored at the portal.

Human Reference Atlas (HRA)

An important goal of the first phase of HuBMAP was establishing standard terminology, as well as 2D and 3D anatomical structure reference frameworks for mapping the human body across scales1: from the entire human body to organs, functional tissue units (FTUs), cells, and molecular markers (see Fig. 1b). FTUs are defined as the smallest multicellular tissue organization that performs a unique physiologic function in concert with the surrounding microenvironment and is replicated multiple times in a whole organ21; examples are alveoli in the lung, crypts in the large intestine, glomeruli in the kidney, and islets in the pancreas.

To this end, HuBMAP developed the HRA4, which aims to unify terminology and data infrastructure across consortia, such as the Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN)22 and Human Cell Atlas (HCA)23, and to name and spatially characterize major anatomical structures, cell types, and biomarkers (ASCT+B). ASCT+B tables have been established for 26 organs (Fig. 1c, left of the male and female reference bodies). Additional organs will be added during the production phase, including the female reproductive system (ovary, fallopian tube, breast, and uterus), eye, lymphatic vessels, and skin (Fig. 1c, right of the two 3D reference bodies). ASCT+B table entities are linked to existing ontologies, Uberon24 and Foundational Model of Anatomy for anatomical structures25,26, Cell Ontology for cell types27, and HUGO Gene Nomenclature for gene and protein biomarkers28 (https://www.genenames.org). Standardization across these domains is necessary for quality control and integrated analysis of ASCT+B across different systems in the body. Publication evidence exists for approximately 80 percent of the 2,582 anatomical structures, 898 cell types, 2,548 biomarkers, and the 13,882 interlinkages between anatomical structures, cell types, and biomarkers. More than 6,000 experimental datasets have been registered into this spatially and semantically explicit HRA framework via the Registration User Interface21 (RUI) for 53 organs. HuBMAP tools and methods are being used to map high quality experimental data for healthy human adults from other consortia to increase the quality and coverage of the HRA. These include 47 kidney datasets from HuBMAP, 196 datasets of 49 organs from the Chan Zuckerberg CELLxGENE Discover Portal29 (https://cellxgene.cziscience.com), 25 datasets of 8 organs from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Portal30 (GTEx, https://gtexportal.org), 21 kidney datasets from the Kidney Precision Medicine Project31 (KPMP), and 14 brain datasets from the Neuroscience Multiomic (NeMO) Archive32 portal (https://nemoarchive.org).

A web- and R-based application called Azimuth was developed to automate the processing, analysis, and interpretation of scRNA-seq experiments using annotated reference datasets3. Azimuth performs normalization, visualization, cell annotation, and differential expression (biomarker discovery) on a user-provided count matrix of gene expression in single cells. As of May 2023, Azimuth references exist for ten healthy human organs that can be explored using Vitessce33; these references have been used to automatically annotate approximately 280 million cells in about 20,000 datasets. For seven organs, standardized Organ Mapping Antibody Panels (OMAPs; https://humanatlas.io/omap) have been established that make it possible to map new experimental data to the evolving atlas6.

The utility of healthy HRA data for understanding human development, aging34, and tissue function and dysfunction in health and disease has been showcased in several publications. Lake et al. provide high quality data for the kidney Azimuth reference and demonstrate how healthy and diseased tissue can be compared13. Hickey et al. provide linked single-cell multiome and spatial CODEX multiplexed imaging data to compare how cellular differentiation and organization change across the large and small intestine and code for hierarchical cell neighborhood analysis and visualization11. Greenbaum et al. provide the first spatio-temporal atlas of the human maternal-fetal interface and a statistical model of trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling in the first half of human pregnancy12. Ghose et al provide a first 3D map of skin showing shorter distances between immune and endothelial cells and higher immune cell densities in 3D vs 2D, highlighting the benefits of 3D for cell spatial analysis9.

HuBMAP Portal

All data generated in HuBMAP are made publicly available after rigorous quality assessment and control. A cloud-based database hosts raw experimental output as well as processed data and published downstream analyses. Extensive metadata concerning biospecimens, assays, and protocols are available (https://portal.hubmapconsortium.org). Users can search the HuBMAP portal for donors, samples, and datasets by sex, organ, data type, etc. Search results are displayed as a list with further filter options and data visualizations in Vitessce, with links to experimental, computational, and metadata information. Users can run spatial searches using the Exploration User Interface21 (EUI, https://portal.hubmapconsortium.org/ccf-eui) by placing a probing sphere to define a 3D space, enabling the exploration of tissue blocks and associated datasets in this space. Resulting datasets are listed on the right side of the EUI together with provenance and donor metadata along with thumbnails indicating assay types such as CODEX or LC MS (liquid chromatography mass spectrometry). The spatial search can be performed across more than 1,500 anatomical structures and more than 6,000 spatially registered datasets to retrieve cell types commonly located in these spatial areas.

HuBMAP Outreach

An important part of HuBMAP has been the dissemination of its data, code, methods, and results. Methodologic and didactic resources have been made available to the community. As of May 2023, HuBMAP published 215 protocols35 and 20+ standard operating procedures (SOPs) (https://humanatlas.io/standard-operating-procedures). More than 70 public talks, demos, and other videos are available from HuBMAP members on its YouTube channel36.

Biological Insights

Several biological concepts and insights emerged from initial atlasing efforts including 2D/3D cellular relationships in spatially resolved FTUs, rare or previously undocumented cell types and mechanisms associated with clinical outcomes, homeostasis, and disease.

Unique microenvironments in healthy and disease FTUs and remarkable cellular diversity associated with underlying pathobiology.

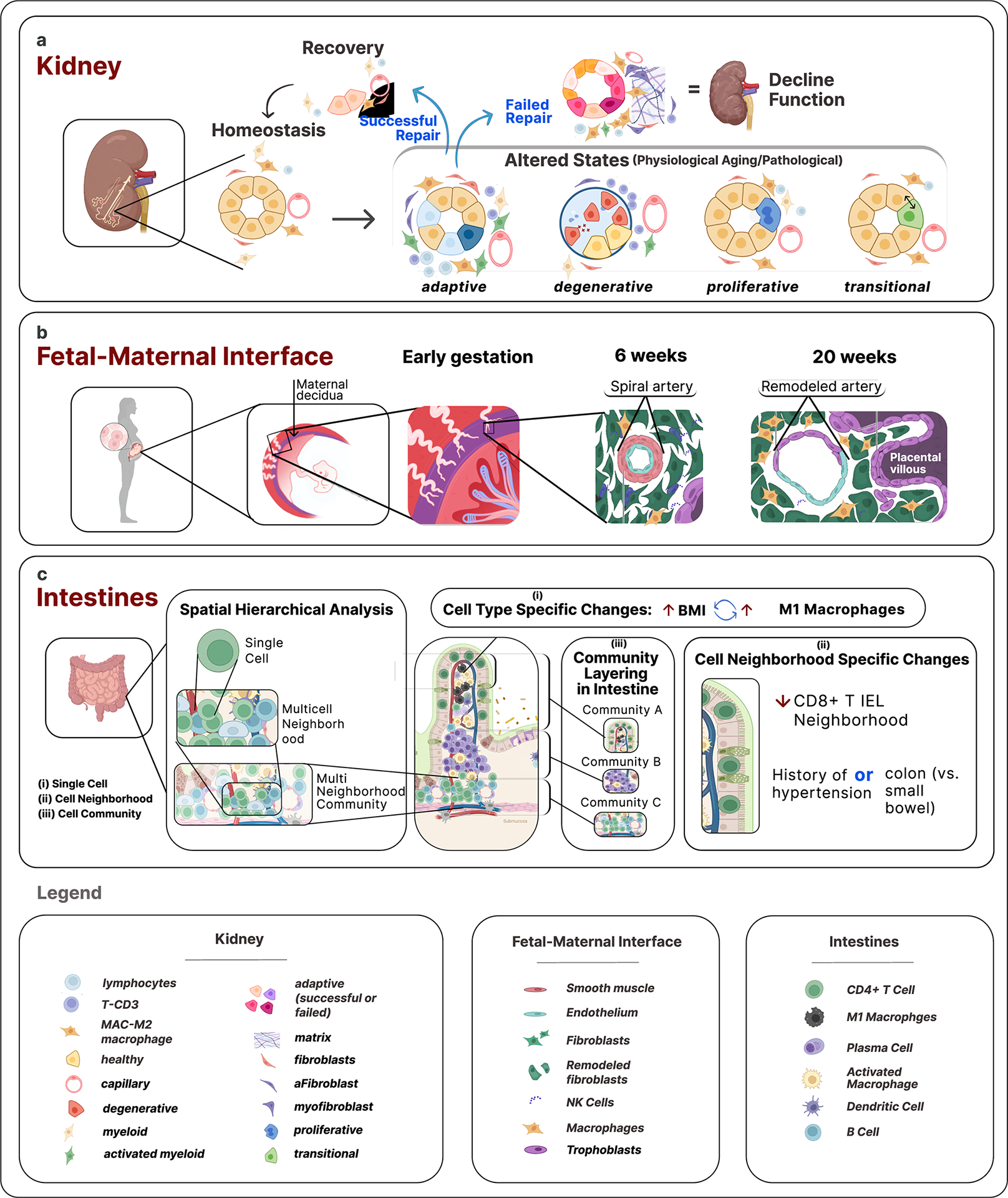

A consistent theme has been that the 2D and 3D maps reveal unique spatial association of parenchymal cells with different subtypes of immune or stromal cells in distinct FTUs of different tissues (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Unique functional tissue unit neighborhoods in different biological contexts in the human body.

Illustrated are three themes demonstrating functional and neighborhood relationships revealed through HuBMAP atlas data. a) Remarkable differences in interstitial neighborhood of kidney tubules in homeostasis and altered states. Single cell analysis of healthy and diseased kidneys uncovered healthy and several altered cell states. Spatial analysis (2D and 3D) led to the discovery of differential enrichment of immune and stromal cells in adaptive (successful or failed repair of tubules) and degenerative (severely injured cells with degenerative changes) states. The failed repair tubules show enrichment of macrophages, adaptive fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with fibrosis due to collagen deposition, while degenerative tubule cells associate more with CD3+ lymphocytes. b) Distinct immune cell neighborhood of immature and remodeled spiral arteries at the maternal-fetal interface at different gestational ages coincides with maturing placental villi. As gestation progresses, the immune cell composition changes from high-NK/low-macrophages to high-macrophages/ow-NK cells, a pattern that can ascertain gestational age and is associated with paracrine interactions between the placental villous trophoblasts and spiral artery endothelial cell mediated remodeling. c) The healthy human intestine was analyzed at the single-cell level with spatial resolution using a multi-hierarchical approach to define cellular neighborhoods and multi-neighborhood communities. Biological insights were obtained at three scales, for example: (i) at the cell type level, M1 macrophages positively correlate with body mass index (BMI); (ii) at the neighborhood level, the “CD8+ T cell IEL” multicellular neighborhood decreased in the colon compared to the small intestine and for patients with a history of hypertension; (iii) at the cellular community level, distinct cellular communities were identified and found to be layered from the submucosa to the lumen, driven by distinct compositions of epithelial, immune, and mesenchymal cells in these communities. These illustrations relay concepts and are not intended to be truly reflective of actual biological scale and cellular composition. Some of the icons were created with BioRender.com.

For example, integrated analyses through an interconsortium effort between HuBMAP and KPMP using single nucleus/cell RNA-seq, spatial transcriptomics of ~300K cells, and 3D neighborhoods of more than a million cells with imaging cytometry described unique immune and stromal cell microenvironment associated with healthy (reference or mature) and altered (non-reference) cell states13. Genes associated with altered tubular epithelium cell states were indicative of failed repair and associated with progression to kidney disease13 (Fig. 3a). Molecular maps of metabolites and lipids of key FTUs spanning the entire nephron along the kidney cortico-medullary axis revealed distinct patterns associated with filtration, secretion, absorption, solute transport, glucose metabolism and water balance, indicative of the unique functional organization of the nephron8.

In the human maternal-fetal interface atlas12, changes in decidual composition and structure were dependent on both temporal and microenvironmental queues (Fig. 3b). For example, time-dependent changes in the frequency of NK cells, T cells, and tolerogenic macrophages were sufficiently robust such that gestational age could be predicted based on these parameters alone. In contrast, the progression of spiral artery remodeling (SAR) was locally regulated in the nearby tissue microenvironment by placentally-derived extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs) that encircled and invaded each vessel. Using spatial transcriptomics, the investigators developed an integrated model of SAR supporting an intravasation mechanism where EVT vessel invasion is accompanied by upregulation of pro-angiogenic, immunoregulatory programs, promoting interactions with vascular endothelium while avoiding activation of circulating maternal immune cells. Together, these results support a coordinated model where gestational age drives a transition to an immune-permissive niche that is conducive to decidual invasion and vascular remodeling by genetically foreign EVTs.

Similarly, the intestine atlas11 provides a detailed overview of relationships of epithelial, mesenchymal, and immune cells across spatial hierarchies (Fig. 3c). At the cellular level, CD8+ T cell counts decreased from the small intestine to the large intestine, though primarily within the CD8+ T Cell Enriched Intraepithelial Lymphocyte (IEL) neighborhood. Interestingly, these intraepithelial-located CD8+ T cells were decreased in subjects with a history of hypertension. The investigators identified intestinal crypt neighborhoods containing adaptive immune cells in the small and large intestine. These aligned with Paneth cell-enriched neighborhoods in the small intestine, whereas in the large intestine, the stem cell crypt was identified with increasing neuroendocrine cell density toward the bottom of the crypt. Even beyond the stem cell zone, multi-neighborhood communities of cells were found based on the composition of immune, epithelial, and mesenchymal cells in each zone of the intestine and interestingly were distinctly layered with increasing proximity to the lumen of the intestine. These results reflect the complex and distinct cell type organization in the human intestine.

Unique epigenetic profiles associated with cell states and FTUs.

The kidney and intestine atlases interrogated epigenetic regulation at cellular resolution and identified transcription factor binding site (TFBS) activities unique to different FTUs and cell states using chromatin accessibility studies11,13. As cells transitioned from healthy to altered cell states in the kidney, TFBS activities and corresponding gene regulatory networks and pathways changed. For example, TFBS motifs of estrogen related receptor (ESSR), key regulator of healthy thick ascending limb (TAL) gene network, were inactivated in the altered TAL cells of the kidney. Further, TFBS activities of pathways associated with fibrosis (TGFß) and inflammation (REL/NF-Kß) were increased in maladaptive TAL cell state. In the intestine, ETV6 TFBS motifs were enriched in differentiated colon cells while that of ASCL2 in more undifferentiated cells11.

Translational potential of multimodal single-cell atlases.

One of the key advantages of healthy atlas efforts is that the healthy state can be used as a benchmark to understand the progression to altered states due to aging, infections, injury, or biological variables. These comparisons inform biomarkers, mechanisms, and disease course. For example, joint analyses of healthy and disease specimens in the kidney atlas identified cell states, neighborhoods, and genes in different FTUs that drive kidney injury and are associated with a decline in kidney function13. This work identified a senescence-associated phenotype in injured cells that likely drive maladaptive repair. Comparative analysis of papilla cells of healthy and kidney stone disease patients identified increased expression of MMP7 and MMP9, genes associated with cell injury and matrix remodeling, in a number of cell types in patients with active stone disease and in regions of mineralization in the papilla10. Further, both these secreted proteins were increased in urine of patients and might become clinically informative markers of kidney stone disease10. In the intestine, M1 macrophages were associated with changes in body mass index, which potentially indicates an early stage of gastrointestinal disease11.

Multimodal analysis enhances opportunities for discovery of cell types and empowers comparisons among organs.

Multi-modal interrogation of cellular and molecular features including different cell states and genes using different technologies (sc/snRNA-seq, sc/snATAC-seq, multiplex immunofluorescence and spatial transcriptomics) enabled discovery of cell types and tissue sub-compartmentalization at the FTU level, orthogonal validation, spatial resolution of high-dimensional single-cell data, and discovery of similarities among gene expression patterns across organs. While single-cell transcriptomics data helped uncover cellular diversity, detected rare cell types and associated expression profiles, concomitant analysis of specific regions of interest using CODEX identified a MUC6+ mucous-producing cell type in a specific region of the intestine11. The transcription factor ETV6 was expressed in the colon, only in differentiated absorptive cells, and in the kidney, where its chromatin accessibility and expression levels were high in altered tubules and not in differentiated tubules13.

Future Steps, Challenges and Opportunities

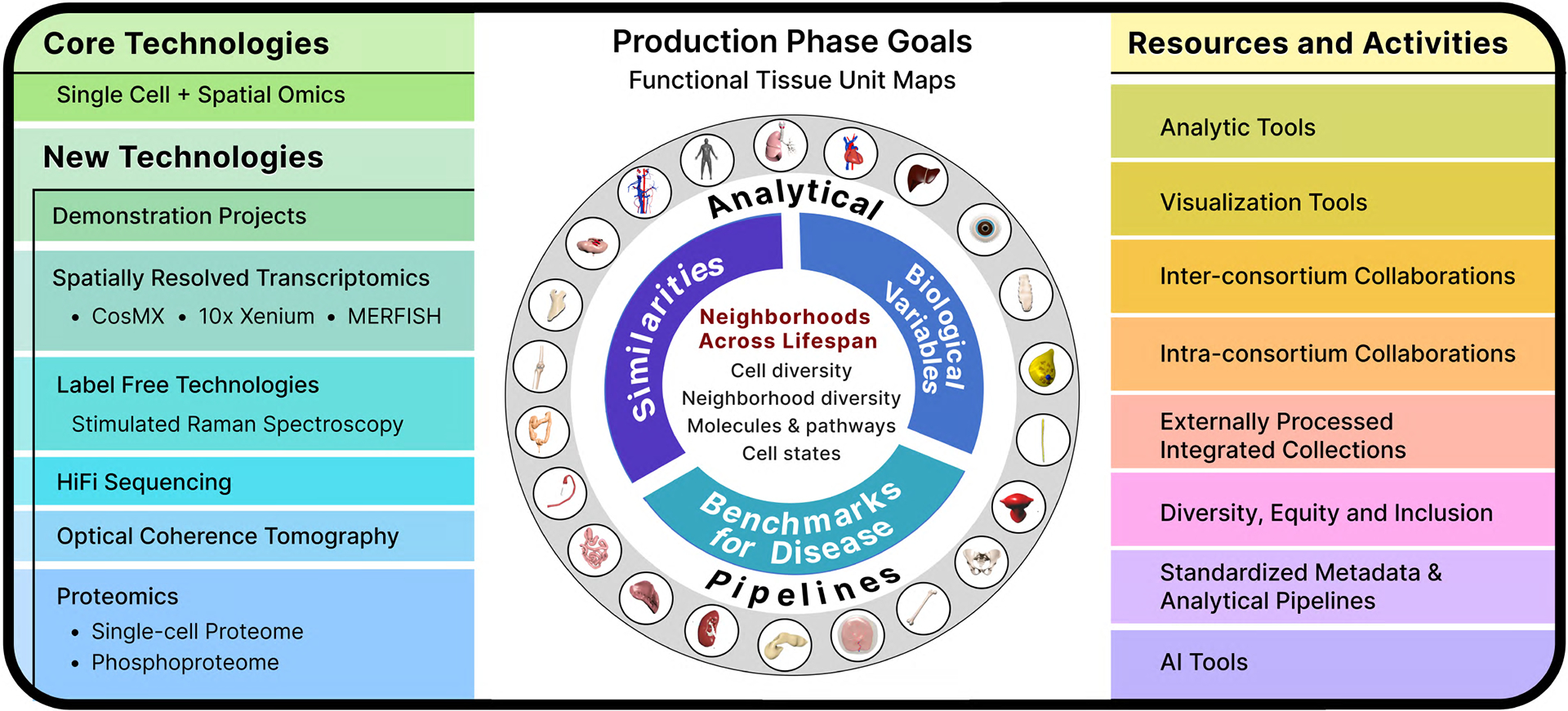

The HuBMAP production phase (2022–2026) has several goals, many of which are unique to HuBMAP (Fig. 4). First, it will generate many reference datasets, including from several new technologies, with an emphasis on building 3D maps as well as collecting data from diverse donors that represent a range of demographic features (sex, race/ethnicity, and age). Second, it will develop methods to overcome challenges and gaps in aligning outputs of the different technologies. Finally, it will improve metadata standards, analytical and visualization tools, data integration and interpretation to enhance the tissue atlases of the human body through collaborative efforts. The production phase plans to deliver 3D multiscale molecular tissue maps at single-cell (or even subcellular - nucleus, mitochondria) resolution from human organs, as well as across systems that span many organs throughout the entire body (e.g., the vascular and lymphatic systems). We will adapt workflows for collecting and processing data at scale, as well as creating tools for the community to navigate and leverage the HuBMAP data and resources. HuBMAP aims to establish procedures and build resources to address several challenges that are expected in integrating diverse data types from many organs by generating robust, orthogonally validated spatial maps by standardizing nomenclature, metadata, and identifying “bridges or anchors” across assays for integrated analysis.

Figure 4. New technologies, resources, integrated knowledge base and mapping in the production phase.

Left. All organs generate molecular data from core technologies that include single-cell/single-nucleus RNA-seq, morphology, antibody-based protein expression and metabolomics. Several new technologies will be applied in addition. Right. Resources for the community and atlasing efforts. Analytical tools include Azimuth for ATAC-seq and RNA-seq, cell segmentation and neighborhood mapping. Visualization tools include enhancement of Vitessce for 2D and 3D viewing of single cell and spatial data and tracking of specimens with associated data and ASCT+B on the Human Reference Atlas portal. Inter-consortium efforts include harmonizing nomenclature via ASCT+B tables and 2D/3D anatomical structure references, tissue exchange and community tools for mapping and visualization. Intra-consortium efforts include collaborations among the various components of HuBMAP, such as common antibody or targeted transcriptome panels, cross organ comparative analysis such as vasculature or extracellular matrix. External processed integrated collections will provide a mechanism to import external QC data into HuBMAP portal and create opportunities for synergies in organ mapping projects and discovery. Diversity, equity and inclusion efforts are dedicated to establishing infrastructure to attract individuals from underrepresented and disadvantaged backgrounds and provide opportunities for cutting-edge research and to foster their career goals. Standardized data and analytical pipelines will enhance quality control by harmonizing metadata standards across tissue mapping centers and technologies with detailed documentation of metadata, assays, and analytical parameters. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools are resources where users will be able to visualize omics data integrated with histology, quantify tissue components at the level of cell state and predict gene or protein expression or cell identity from histology slides. Center. The information from technologies and resources will be leveraged to create spatial maps of Functional Tissue Units (FTUs) and 2D/3D neighborhoods across HuBMAP organs. The knowledge base created will enable comparative analysis of cell types and neighborhoods across organs to identify similarities, understand how diversity (age, sex, and race) affects FTU maps and create a benchmark reference atlas of FTUs for studying changes in disease and targets for therapies. Some of the icons were created with BioRender.com.

Expanding Production and Molecular Technologies for Comprehensive Maps

HuBMAP is implementing cutting-edge pipelines that bring together single-cell and spatial transcriptomics workflows37, as well as expanding existing assays (e.g., multiplex ion beam imaging38,39, highly multiplexed antibody-based imaging strategies) and adding imaging approaches. Newly added assays include HiFi-Slide sequencing40, CosMx38, and Xenium (10xGenomics) spatially resolved transcriptomics, SIMS imaging39, Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy41,42, optical coherence tomography43,44, spatially driven mass spectrometry technologies, and quantitative proteome imaging45. Single-cell proteome and phosphoproteome analyses can be readily related to phenotype and are amenable to integrate with other multiomic analyses including lipidomes and metabolomes. Spatial mapping protocols, datasets and analytical pipelines will be enhanced to achieve at or near single-cell resolution of several organs using these technologies.

One of the challenges in various atlas efforts is the need to standardize vocabularies and enhance interoperability for successful integration. To this end, HuBMAP will work to strengthen collaborations with other atlasing efforts (e.g., HTAN22 (NIH), Cellular Senescence Network34 (SenNet, NIH), KPMP31 (NIH), LungMAP46 (NIH), Human Cell Atlas23 (HCA, CZI), Human Protein Atlas47 (HPA), Genotype-Tissue Expression project48 (GTEx, NIH)), and create an ecosystem of data and code for mapping the human body at high resolution. These collaborations will align preanalytical metadata, tissue procurement, processing, preservation, and analytical methods to enable running multiple assay types and data analysis workflows on the same tissue across institutions. The organs will be extensively sampled with a goal of 20–50 donors per organ using detailed protocols and operating procedures to ensure reproducibility. This will enhance quality control and facilitate generation of comprehensive organ and body reference maps with several layers of orthogonal validation, increasing confidence in results that are essential for new biological insights, hypotheses, and benchmarks for disease.

Data Analysis, Tools and Integration Across Scales and Modalities

HuBMAP is developing data integration and analytical approaches during its production phase. Machine learning and deep learning tools are being developed and applied to single cell and spatial data to identify cell types, to match their spatially registered molecular profiles with morphology, and to describe relationships with the microenvironment49 (Fig. 4). Innovative approaches and tools are being developed to automate molecular and cell type predictions and segmentation of morphological features in light microscopy images49–51. HuBMAP data and analytical pipelines will enable comparison of molecular profiles and neighborhoods of the same general cell type across different regions and organs to identify shared functions and features for a given cell type across organs in homeostasis (Fig. 4). We will also focus on organ vasculature (veins, arteries, and lymphatics) and rigorous evaluation of its spatial relationships between different cell types (epithelial, immune, stroma etc.). Defining these spatial relationships in conjunction with multiomic data will enable identification of biologically relevant ligand-receptor interactions in these microenvironments (e.g., cells within glomeruli and their relationship with the extracellular matrix in kidneys) and how the molecular and cellular functions for a given cell type compares across organs (e.g., genes important in water transport across kidney, intestine, and lung). Furthermore, we will extend and generalize the automated discovery of cross-modality relationships and their capture into computational models for prediction52 as well as interpretation. One example of the latter is the automated biomarker candidate discovery for FTUs, where imaging mass spectrometry measurements covering hundreds of molecular species are integrated with coregistered microscopy-derived tissue annotations and interpretable supervised machine learning is used to automatically discern FTU-specific molecular markers53. An important aspect of the HuBMAP production phase will be to help identify how the diverse donor demographics affect cellular diversity and spatial relationships. Thus, efforts will be made to collect samples from diverse populations through enhanced local or consortium-wide procurement efforts and shared across groups for atlas construction and comparative analyses. Single donors contributing multiple organs will be pursued to enable comparisons of tissues from the same donor.

Enabling Broad Utility for Different Users, Education and Outreach

The production phase of HuBMAP is committed to improving data access and utilization tools (Fig. 4). These include enhanced spatial data registration and indexing of all tissue datasets using anatomical structure tags. Single cell and FTU segmentation workflows will be produced and automated for all major organs. Azimuth and OMAPs will be expanded to include all organs and also within existing mapped organs to include cell states and associated biomarkers in single cells, FTUs, and anatomical structures. In this way, HuBMAP experimental data will be linked (spatially and semantically) to the HRA and atlas user interfaces. A vasculature-based common coordinate framework (VCCF) will be developed to facilitate comparison and coordination across tissues4,54. As splicing results in multiple forms of protein, or proteoforms, from a single gene, the concept of proteoform biomarkers will be implemented to capture this greater proteome diversity in the HRA, recently shown to correlate strongly with cell types55. Importantly, it will be possible to explore the resulting data and ontology linkages not only via visual interactive user interfaces21,54, but also via application programming interfaces (APIs). The full integration of the HRA into the HuBMAP portal will make it possible to define the exact experimental data used to construct the HRA (full data provenance, transparency, and reproducibility). In addition, it will allow querying different experimental data and results generated by multiple teams using a unified metadata schema, such as spatial data, cell, FTU annotation and segmentation, and donor information. This infrastructure will enable a clinician or scientist to readily localize the site of action of a drug target in multiple organs of diverse populations. In addition, we envision HuBMAP data and tools becoming an important part of general education both in classrooms and for public engagement.

A Resource for Understanding Development, Aging and Disease

The HuBMAP knowledge base and tools are expected to both catalyze and promote the generation of biological and clinical hypotheses as well as provide insights into human biology and disease. For example, technologies applied to biological samples covering lifespan will allow investigations of individual cells and neighborhoods in healthy aging. Such information can be integrated with projects such as SenNet34, which aims to define and map human senescent cells across human organs [https://sennetconsortium.org]. Using the HuBMAP reference, one can better understand changes in the context of acute and chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease) and during the human lifespan. For example, KPMP31 aims to understand the molecular basis of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease at single-cell resolution and help glean insights into the molecular trajectories and changes in neighborhoods during transition from healthy to disease states.

HuBMAP will serve as a valuable reference for cancer atlas maps. Tumor formation, progression and treatment are influenced by the cellular environment56. 2D and 3D single-cell maps are being generated by the HTAN and others and rely on a normal tissue reference for comparison. These maps are built on both tumor tissue as well as early-stage precancerous samples (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ and precancerous polyps). In addition to spatial relationships, such maps reveal early events involved in cancer formation or progression, such as the presence of stem cells or transcriptional regulatory events57.

Another area of opportunity is to expand beyond HuBMAP’s focus on adult tissues to include fetal and pediatric organs, which are at earlier stages of development with different physiology and biology than adult organs. Inclusion of comprehensive and longitudinal fetal and pediatric atlases of various organs will help understand physiological maturation, aging, and progression of disease, thereby providing a holistic perspective of human biology across the entire life span.

Demonstration Use Cases

In the production phase, HuBMAP initiated Demonstration Projects highlighting the utility of HuBMAP data. These include: 1) investigating mitochondrial DNA variant accumulation with aging; 2) building the human extracellular matrix atlas; 3) identifying organotypic and disease-specific vascular cell populations; and 4) reverse engineering the extracellular neighborhood to restore ovarian function. As an example, somatic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations accumulate with age and contribute to aging-related diseases such as immune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegeneration58,59. Whether accumulation of specific mtDNA variants during aging occurs similarly across different cell types, organs, sexes, and races is unclear. Demonstration Project 1 aims to analyze mtDNA information in human single-cell genomics datasets to obtain insights into how cell/organ type, aging, sex, race, and other factors impact mtDNA and how mtDNA variants affect nuclear gene expression and cell function.

Conclusions

In the next three years, HuBMAP will develop and validate analytical and visualization tools and apply emerging technologies, generating a wealth of molecular data spanning major aspects of the central dogma (DNA, RNA, protein) and defining cellular phenotypes and FTU neighborhoods that will serve as benchmarks to understand homeostasis, aging, and disease. This granular characterization of cells, including their chromatin, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic states, and spatially resolved molecular maps of FTU microenvironments will define the biologically relevant cellular and extracellular communities for each tissue and organ, providing opportunities to explore interrelatedness across organ systems. Such knowledge will be critical in understanding disease or syndromes that affect multiple organs and help design better informed and more precise drug targets (Fig. 4). The molecular landscape of human tissues in biologically diverse populations across the lifespan created in HuBMAP will provide instrumental insights for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. The atlas of each organ will provide an important healthy reference to identify molecules associated with altered cell states that are linked to disease or repair defects. Scientists can use the HuBMAP data to develop experimental models to further understand the underlying biology and mechanisms. HuBMAP data and resources will also enable the discovery of relevant autocrine and short- and long- range paracrine effects that regulate organ crosstalk necessary for homeostasis and potentially impact clinical practice in predicting disease outcomes. To fully realize the potential of these datasets, we must continue to improve access to data and resources with minimum restrictions, and to develop methods that use minimal amounts of tissue for interrogation by multiple single-cell and spatial technologies and application to clinical specimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lettie Margaret McGuire, SciStories LLC, Francesca Goncalves, Heidi Schlehlein and Vikrant Anil Deshpande for their efforts in designing and creating graphics. We thank Alexander Honkala for assistance with manuscript formatting. We thank Zorina Galis from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute for many useful comments. Support for title page creation and format was provided by AuthorArranger, a tool developed at the National Cancer Institute. The authors gratefully acknowledge National Institutes of Health HuBMAP grants U54HL165442 and U01HL166058 (LP), U54DK134301 and OT2OD033753 (SJ), U54EY032442, U54DK120058, U54DK134302 (JMS), OT2OD033756, OT2OD026671 (KB), UH3 CA246635 (NLK), UG3CA256967 (HL), U54HG010426 (MPS), UH3CA246633 (MA), U54HD104393 (LCL, PR), U54DK127823 (ESN, JPC, WJQ), OT2OD033758 (NG), UH3CA246594 (FG), U54EY032442, U54DK134302 (JPG), U54HL145611 (SL, YL), U01HG012680 (U01HG012680), U54DK120058, U54EY032442, U54DK134302 (BRS), UG3CA256959 (MZ) and U54HL165440 (ISV). The authors are also supported by these grants: 2U01DK114933, P50DK133943, U24DK135157 (SJ), U54HL145608 (JSH), U54 HL165443 (JSH) U24CA268108, U2CDK114886 (KB), Department of Defense W81XWH-22-1-0058 and Additional Ventures (LP). JWH was supported by an NIH T32 Fellowship (grant no. T32CA196585) and an American Cancer Society: Roaring Fork Valley Postdoctoral Fellowship (grant no. PF-20-032-01-CSM). This work was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID, and NCI (A.J.R.).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare the following competing interests.

F.G. are employees of GE Research. B.R.S. is an inventor on patents and patent applications involving small molecule drug discovery, and the 3F3-FMA antibody, co-founded and serves as a consultant to Inzen Therapeutics, Nevrox Limited, Exarta Therapeutics, and ProJenX Inc.; and serves as a consultant to Weatherwax Biotechnologies Corporation and Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP. M.P.S. is cofounder and advisory board member of Personalis, Qbio, January AI, Mirvie, Filtricine, Fodsel, Lollo, and Protos. I.S.V. consults for Guidepoint Global, Cowen, Mosaic, and NextRNA. N.G. is a co-founder and equity owner of Datavisyn. H.L. is a co-founder and equity owner of ExoMira Medicine, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Code

The HuBMAP Consortium GitHub at https://github.com/hubmapconsortium has 120 repositories that support data ingest, analysis, visualization, and search plus HRA construction and usage. Documentation is available at https://software.docs.hubmapconsortium.org/apis.html.

References

- 1.Snyder MP et al. The human body at cellular resolution: the NIH Human Biomolecular Atlas Program. Nature 574, 187–192 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HuBMAP Data Portal. https://portal.hubmapconsortium.org/.

- 3.Hao Y et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587.e29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Börner K et al. Anatomical structures, cell types and biomarkers of the Human Reference Atlas. Nat. Cell Biol 23, 1117–1128 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickey JW et al. Spatial mapping of protein composition and tissue organization: a primer for multiplexed antibody-based imaging. Nat. Methods 19, 284–295 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quardokus EM et al. Organ Mapping Antibody Panels: a community resource for standardized multiplexed tissue imaging. Nat. Methods 10.1038/s41592-023-01846-7 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP) Manuscript Repository.

- 8.Neumann EK et al. A multiscale lipid and cellular atlas of the human kidney. 2022.04.07.487155 Preprint at 10.1101/2022.04.07.487155 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghose S et al. Human Digital Twin: Automated Cell Type Distance Computation and 3D Atlas Construction in Multiplexed Skin Biopsies. 2022.03.30.486438 Preprint at 10.1101/2022.03.30.486438 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canela Victor Hugo et al. A spatially anchored transcriptomic atlas of the human kidney papilla identifies significant immune injury and matrix remodeling in patients with stone disease. Nature Communication, 2023, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickey J et al. High Resolution Single Cell Maps Reveals Distinct Cell Organization and Function Across Different Regions of the Human Intestine. Nature, 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenbaum S et al. Spatiotemporal coordination at the maternal-fetal interface promotes trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling in the first half of human pregnancy. Nature, 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lake Blue B et al. An atlas of healthy and injured cell states and niches in the human kidney. Nature, 2023, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eng C-HL et al. Transcriptome-scale super-resolved imaging in tissues by RNA seqFISH. Nature 568, 235–239 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriques SG et al. Slide-seq: A scalable technology for measuring genome-wide expression at high spatial resolution. Science 363, 1463–1467 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guilliams M et al. Spatial proteogenomics reveals distinct and evolutionarily conserved hepatic macrophage niches. Cell 185, 379–396.e38 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stelzer EHK Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for quantitative biology. Nat. Methods 12, 23–26 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black S et al. CODEX multiplexed tissue imaging with DNA-conjugated antibodies. Nat. Protoc 16, 3802–3835 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann EK et al. Protocol for multimodal analysis of human kidney tissue by imaging mass spectrometry and CODEX multiplexed immunofluorescence. STAR Protoc. 2, 100747 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spraggins JM et al. High-Performance Molecular Imaging with MALDI Trapped Ion-Mobility Time-of-Flight (timsTOF) Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 91, 14552–14560 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Börner K et al. Tissue registration and exploration user interfaces in support of a human reference atlas. Commun. Biol 5, 1–9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozenblatt-Rosen O et al. The Human Tumor Atlas Network: Charting Tumor Transitions across Space and Time at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 181, 236–249 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Stubbington MJT, Regev A & Teichmann SA The Human Cell Atlas: from vision to reality. Nature 550, 451–453 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mungall CJ, Torniai C, Gkoutos GV, Lewis SE & Haendel MA Uberon, an integrative multi-species anatomy ontology. Genome Biol. 13, R5 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosse C & Mejino JLV A reference ontology for biomedical informatics: the Foundational Model of Anatomy. J. Biomed. Inform 36, 478–500 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golbreich C, Grosjean J & Darmoni SJ The Foundational Model of Anatomy in OWL 2 and its use. Artif. Intell. Med 57, 119–132 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meehan TF et al. Logical development of the cell ontology. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 6 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Home | HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. https://www.genenames.org/.

- 29.Chan Zuckerberg CELLxGENE Discover. Cellxgene Data Portal https://cellxgene.cziscience.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eraslan G et al. Single-nucleus cross-tissue molecular reference maps toward understanding disease gene function. Science 376, eabl4290 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boer I. H. de et al. Rationale and design of the Kidney Precision Medicine Project. Kidney Int. 99, 498–510 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NeMO Archive - Home. https://nemoarchive.org/.

- 33.Manz T et al. Viv: Multiscale Visualization of High-Resolution Multiplexed Bioimaging Data on the Web. Preprint at 10.31219/osf.io/wd2gu (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee PJ et al. NIH SenNet Consortium to map senescent cells throughout the human lifespan to understand physiological health. Nat. Aging 2, 1090–1100 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP) Method Development Community - research workspace on protocols.io. protocols.io https://www.protocols.io/workspaces/human-biomolecular-atlas-program-hubmap-method-development. [Google Scholar]

- 36.HuBMAP Consortium - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/@hubmapconsortium4358.

- 37.Keren L et al. MIBI-TOF: A multiplexed imaging platform relates cellular phenotypes and tissue structure. Sci. Adv 5, eaax5851 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He S et al. High-plex imaging of RNA and proteins at subcellular resolution in fixed tissue by spatial molecular imaging. Nat. Biotechnol 40, 1794–1806 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian H et al. Successive High-Resolution (H2O)n-GCIB and C60-SIMS Imaging Integrates Multi-Omics in Different Cell Types in Breast Cancer Tissue. Anal. Chem 93, 8143–8151 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu T-Y, Calandrelli R, Lin P, Zhu D & Zhong S HiFi-Slide spatial RNA-Sequencing. (2022).

- 41.Fung AA & Shi L Mammalian cell and tissue imaging using Raman and coherent Raman microscopy. WIREs Syst. Biol. Med 12, e1501 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang W et al. Multi-Molecular Hyperspectral PRM-SRS Imaging. 2022.07.25.501472 Preprint at 10.1101/2022.07.25.501472 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balaratnasingam C et al. Histologic and Optical Coherence Tomographic Correlates in Drusenoid Pigment Epithelium Detachment in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 124, 644–656 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spaide RF & Curcio CA ANATOMICAL CORRELATES TO THE BANDS SEEN IN THE OUTER RETINA BY OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY: Literature Review and Model. RETINA 31, 1609 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y et al. Nanodroplet processing platform for deep and quantitative proteome profiling of 10–100 mammalian cells. Nat. Commun 9, 882 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ardini-Poleske ME et al. LungMAP: The Molecular Atlas of Lung Development Program. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 313, L733–L740 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uhlén M et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lonsdale J et al. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet 45, 580–585 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brbić M et al. Annotation of spatially resolved single-cell data with STELLAR. Nat. Methods 19, 1411–1418 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Govind D et al. Integrating image analysis with single cell RNA-seq data to study podocyte-specific changes in diabetic kidney disease. in Medical Imaging 2022: Digital and Computational Pathology vol. 12039 160–166 (SPIE, 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lutnick B et al. A user-friendly tool for cloud-based whole slide image segmentation with examples from renal histopathology. Commun. Med 2, 1–15 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van de Plas R, Yang J, Spraggins J & Caprioli RM Image fusion of mass spectrometry and microscopy: a multimodality paradigm for molecular tissue mapping. Nat. Methods 12, 366–372 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tideman LEM et al. Automated biomarker candidate discovery in imaging mass spectrometry data through spatially localized Shapley additive explanations. Anal. Chim. Acta 1177, 338522 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weber GM, Ju Y & Börner K Considerations for Using the Vasculature as a Coordinate System to Map All the Cells in the Human Body Front. Cardiovasc. Med 7, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melani RD et al. The Blood Proteoform Atlas: A reference map of proteoforms in human hematopoietic cells. Science 375, 411–418 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackenzie NJ et al. Modelling the tumor immune microenvironment for precision immunotherapy. Clin. Transl. Immunol 11, e1400 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Becker WR et al. Single-cell analyses define a continuum of cell state and composition changes in the malignant transformation of polyps to colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet 54, 985–995 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wallace DC Mitochondrial DNA variation in human radiation and disease. Cell 163, 33–38 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace DC Mitochondrial genetic medicine. Nat. Genet 50, 1642–1649 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]