Abstract

This meta‐analysis aimed to evaluate the impact of autologous platelet concentrates (APCs) on wound area reduction based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library to identify relevant literature. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of wound area reduction. Secondary outcome measures included wound healing time and the incidence of infection. A total of 14 studies were included in the meta‐analysis. The results showed that the percentage of wound area reduction was significantly greater in the APCs group compared to conventional treatments (standardized mean difference [SMD] 1.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.27–2.68, p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that the percentage of wound area reduction varied based on wound location, follow‐up duration, and type of APCs used. The healing time and incidence of infection presented no significant difference between the two groups. The findings suggest that APCs can effectively reduce wound areas when compared to conventional treatments, without increasing the risk of infection. In addition, the effectiveness of APCs in wound area reduction may vary depending on factors such as wound location, type of APCs used, and follow‐up duration.

Keywords: autologous platelet concentrates, impact, meta‐analysis, randomized controlled trial, wound area reduction

1. INTRODUCTION

The skin serves as both a physical and chemical barrier, safeguarding internal organs and the overall body from pathogens and dehydration. 1 Skin wounds can be categorized as acute or chronic. Chronic wounds result from disrupted natural healing processes and encompass conditions such as trauma, venous ulcers, pressure ulcers, and diabetic foot ulcers. In certain cases, the natural healing process is hindered, leading to the formation of chronic refractory wounds. These wounds cause a decline in patients' quality of life and impose a substantial societal burden. Although current practices for chronic wound management involve debridement and dressing changes, they often yield unsatisfactory outcomes, necessitating the development of novel treatment modalities.

Advancements in cellular histology and biochemistry have given rise to a multitude of options for wound management. 2 Platelet‐rich concentrates, known as autologous platelet concentrates (APCs), have garnered significant attention in recent years and demonstrate remarkable potential in wound treatment. 3 Extensive research has provided physicians and scientists with an improved understanding of the biological effects of APCs, particularly the crucial role played by specific platelet proteins and their biological components, which extend beyond their well‐established function in haemostasis, in the process of wound healing. 4 Previous studies have shown that activated platelets undergo exocytosis of intracellular granules containing growth factors such as platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β), epidermal growth factor (EGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and insulin‐like growth factor (IGF). These growth factors contribute to wound healing by promoting regeneration and wound repair, 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 thereby elucidating the efficacy of APCs therapy in skin regeneration, acne scar treatment, and enhanced wound healing.

APCs can be further classified into platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) and platelet‐rich fibrin (PRF) based on distinct preparation processes, each with varied clinical applications. PRP, as the first‐generation platelet concentrate, is plasma with a high platelet concentration obtained through specific centrifugation of fresh whole blood. It has demonstrated positive effects on bone regeneration and wound healing. 9 PRF, on the other hand, as the second‐generation platelet concentrate, exhibits a slow release of growth factors, thereby prolonging their action. 10 Compared with traditional wound treatment methods like Unna's paste or saline treatment, APCs has a greater capacity to modulate the local microenvironment and expedite tissue regeneration. It has also been observed to alleviate pain, accelerate epithelization, and facilitate complete wound healing. 11

Although APCs is widely regarded as effective, there are discrepancies in clinical study reports regarding its impact on reducing wound area. To address this, we conducted a meta‐analysis to integrate and analyse the results of multiple studies, aiming to elucidate the benefits of APCs in wound area reduction. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential variations in terms of region, wound location, type of APCs, and follow‐up duration between the two groups.

2. METHODS

This systematic review was conducted following the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The review protocol was registered in advance on PROSPERO (ID = CRD42023414290).

2.1. Literature search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, and the Cochrane Library from the inception of the databases up to June 1st, 2023 (Table S1). In addition, the reference lists of retrieved articles were examined for additional relevant studies. The search terms used included: ‘APCs’ or ‘autologous platelet concentrates’ or ‘PRP’ or ‘platelet‐rich plasma’ or ‘PRF’ or ‘platelet‐rich fibrin’ or ‘platelet gel,’ combined with ‘ulcer’ or ‘graft’ and ‘wound.’

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (I) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (II) participants: patients with skin wounds, such as skin ulcers and skin grafts; (III) intervention: treatment with APCs; (IV) comparison: conventional treatment such as silver sulfadiazine, saline, or placebo; (V) outcomes: percentage of wound area reduction.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: (I) non‐RCT design; (II) sample size less than 10; (III) lack of relevant outcome measures; (IV) absence of original or complete data.

2.3. Data extraction and management

Two independent investigators screened the remaining articles based on predefined selection criteria, with any disagreements resolved through consensus discussions. Data extraction was performed using standardized forms, including information on author, year of publication, patient characteristics, wound size, age, gender, sample size, wound location, follow‐up duration, and outcomes. The primary outcome measure was the percentage of wound area reduction, while secondary outcome measures included healing time and incidence of infection.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

The quality of each included study was independently assessed by two authors using the second version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB2.0). The evaluation criteria included random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential sources of bias.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The meta‐analysis was conducted using R 4.2.2 software. Continuous variables were reported as standardized mean differences (SMD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), while binary variables were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI. Forest plots were used to present the statistical results. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05. The degree of heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis was assessed using the I 2 statistic, with I 2 ≥ 50% indicating high heterogeneity and the random‐effects model being applied. Conversely, I 2 < 50% indicated low heterogeneity, and the fixed‐effects model was employed. Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted based on region, follow‐up duration, wound location, and type of APCs. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger's regression test.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Literature selection

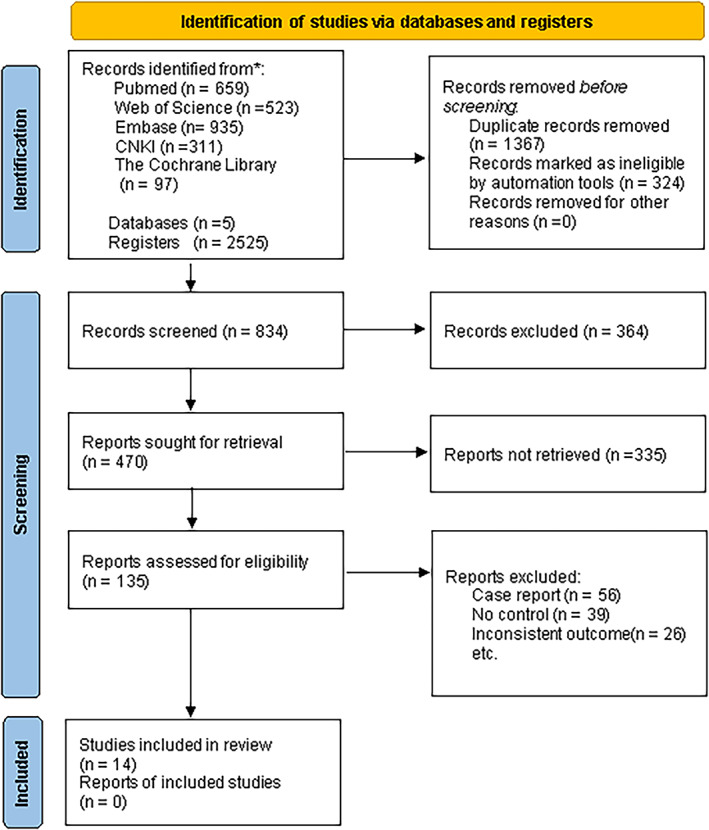

A total of 2525 records were identified from the initial search in the databases. After removing duplicates, 834 articles remained. Among these, 699 articles were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts. The remaining 135 full‐text articles underwent independent evaluation by two investigators, resulting in the exclusion of 121 articles. The reasons for exclusion included 39 articles not being control experiments, 26 articles having inconsistent outcomes, and 56 articles being case reports. Ultimately, 14 studies met the pre‐established selection criteria and were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

3.2. Basic characteristics of included literature

The included studies were published between 2003 and 2021, 1 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 encompassing a total of 616 patients. The sample sizes of individual studies ranged from 14 to 100 participants. Geographically, there were five studies from Europe, four studies from Africa, two studies from the Americas, and the remaining studies from Asia. Among the included studies, 13 focused on the use of platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) dressings for skin ulcers, while one study investigated patients with skin grafts. 13 PRP was utilized in 10 studies, while platelet‐rich fibrin (PRF) was used in four studies. All studies reported the duration of follow‐up, with an average follow‐up period of 7.8 weeks (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study (year) | Patients | Country | Wound size (cm2) | Age | Gender | Wound location | Period | Type | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group (n) | Comparison group (n) | Experimental group (n) | Comparison group (n) | Experimental group (n) | Control group (n) | ||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Male | Famle | Male | Famle | ||||||

| Yuvasri and Rai 12 | 20 | India | 4.90 | 3.09 | 8.28 | 6.69 | NR | NR | Ulcer | 4w | PRF | ||||||

| Goda 1 | 36 | Egypt | NR | 40.1 | 6.8 | 39.3 | 8.2 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 9 | Ulcer | 8w | PRF | |||

| Vaheb et al. 13 | 33 | Iran | 188.00 | 25.52 | 190.00 | 26.20 | 33.1 | 2.6 | NR | 17 | 16 | NR | Graft | 15d | PRF | ||

| Moneib et al. 14 | 40 | Egypt | NR | 36.4 | 10.2 | 32.5 | 7.5 | 19 | 1 | 20 | 0 | Ulcer | 6w | PRP | |||

| Escamilla et al. 15 | 58 | Spain | NR | 64.1 | 13.7 | 64.2 | 16.3 | 15 | 40 | NR | Ulcer | 24w | PRP | ||||

| Oliveira et al. 16 | 16 | Brazil | NR | 58 | 18 | 70 | 8 | NR | Ulcer | 90d | PRP | ||||||

| Senet et al. 17 | 15 | France | 13.70 | 7.90 | 10.90 | 8.40 | NR | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Ulcer | 12w | PRP | |||

| Somani et al. 18 | 15 | India | 3.14 | 4.86 | NR | NR | Ulcer | 4w | PRF | ||||||||

| Saldalamacchia et al. 19 | 14 | Italy | 2.73 | 1.56 | 1.70 | 0.89 | 61.1 | 9.4 | 58.1 | 7.8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | Ulcer | 5w | PRP |

| Ramos‐Torrecillas et al. 23 | 100 | Spain | NR | 82.5 | 4.7 | NR | 60 | 40 | NR | Ulcer | 36d | PRP | |||||

| Driver et al. 24 | 40 | US | 2.01 | 1.30 | 2.43 | 1.60 | 58.3 | 9.7 | 55.9 | 8.1 | 16 | 3 | 16 | 5 | Ulcer | 12w | PRP |

| Rainys 22 | 69 | Lithuanian | 12.90 | 16.60 | 10.40 | 11.30 | 62.23 | 14.72 | 68.01 | 14.89 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | Ulcer | 90d | PRP |

| Helmy et al. 20 | 80 | Egypt | 16.70 | 11.06 | 20.40 | 18.50 | 48 | 11 | 44 | 11.4 | 26 | 14 | 23 | 17 | Ulcer | 12m | PRP |

| Hossam et al. 21 | 80 | Egypt | 15.15 | 5.64 | 14.50 | 5.57 | 54.9 | 2.37 | 54.8 | 3.9 | 28 | 12 | 34 | 6 | Ulcer | 8w | PRP |

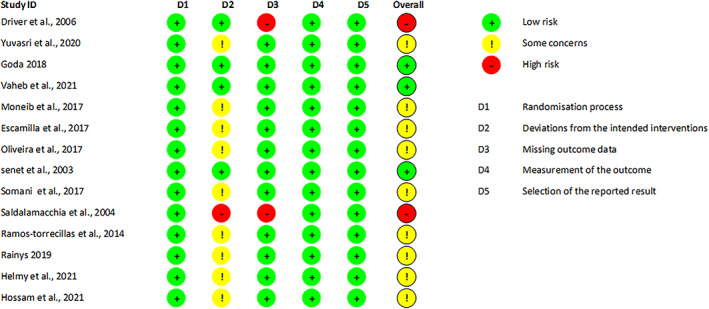

3.3. Quality of included literature

All the included studies incorporated randomization methods (Figure 2). Three RCTs were assessed as having a low risk of bias, while nine studies were rated as having a moderate risk of bias due to the lack of detailed explanations regarding specific randomization methods. Two studies were considered to have a high risk of bias due to concerns about missing data (Figure S1).

FIGURE 2.

Risk of bias summary.

3.4. Meta‐analysis

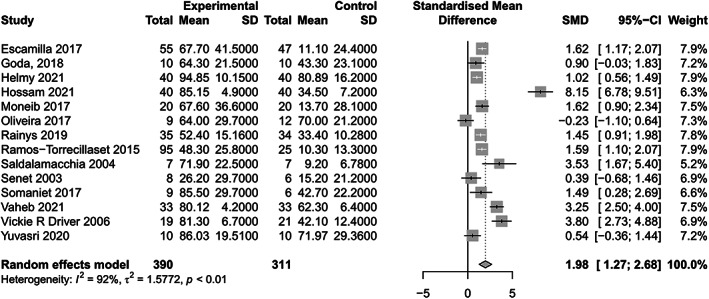

3.4.1. Results percentage of wound area reduction

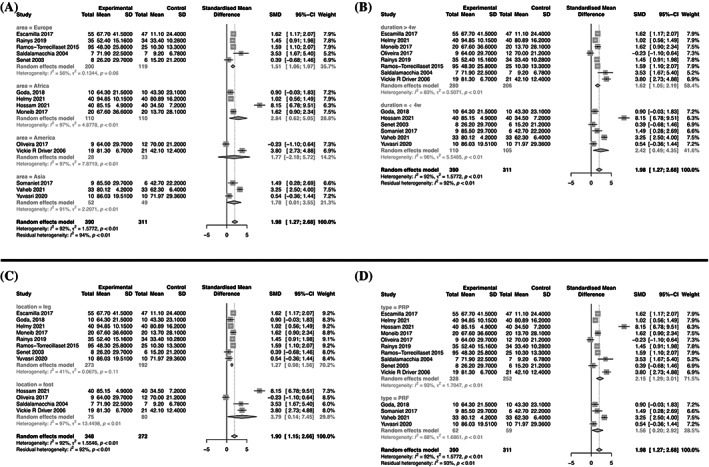

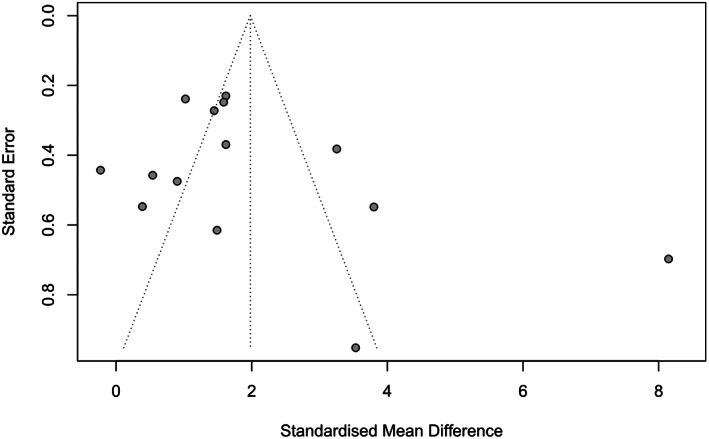

All studies reported the percentage of wound area reduction after APCs therapy. The statistical analysis indicated a significantly greater percentage of wound area reduction in the APCs group compared to the control group (SMD = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.27–2.68, p < 0.001, I 2 = 92%) (Figure 3). Subgroup analyses revealed no significant differences in the percentage of wound area reduction between different regions (Europe: SMD = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.06–1.97; Africa: SMD = 2.84, 95% CI: 0.62–5.05; Americas: SMD = 1.77, 95% CI: −2.18–5.72; Asia: SMD = 1.78, 95% CI: 0.01–3.55; Figure 4A). The results also indicated that the percentage of wound area reduction varied with follow‐up duration (duration >4 weeks: SMD = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.05–2.19; duration ≤4 weeks: SMD = 2.42, 95% CI: 0.49–4.35; Figure 4B), wound location (leg: SMD = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.98–1.56; foot: SMD = 3.79, 95% CI: 0.14–7.45; Figure 4C), and type of APCs used in the experimental group (PRP: SMD = 2.15, 95% CI: 1.29–3.01; PRF: SMD = 1.56, 95% CI: 0.20–2.92; Figure 4D). The funnel plot (Figure 5) displayed asymmetry on both sides, suggesting the possibility of publication bias. However, quantitative analysis using Egger's test showed no significant publication bias among the included studies (p > 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plots of wound healing size.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plots of subgroup analyses.

FIGURE 5.

Funnel plot of included studies.

3.4.2. Incidence of infection

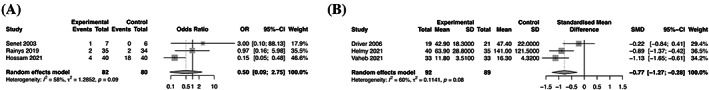

Among the 14 studies, three reported the incidence of adverse events in patients. 17 , 21 , 22 These studies exhibited high heterogeneity (I 2 = 58%). The analysis revealed no increased risk of infection in the APCs group compared to the control group (OR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.09–2.75, p > 0.05; Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plots of secondary outcomes.

3.4.3. Wound healing time

Three out of the 14 included studies reported wound healing time. 13 , 20 , 24 Heterogeneity was observed in the literature (I 2 = 60%). The random‐effects model pooled analysis indicated no statistically significant difference in the time required for wound healing between the APCs group and the control group (SMD −0.77; 95% CI: −1.27 to −0.28; p > 0.05; Figure 6B).

4. DISCUSSION

Results from our study revealed a statistically significant increase in the percentage of wound area reduction in the group treated with APCs compared with the control group. The most favourable outcomes in terms of wound area reduction were observed in Africa, followed by Asia, America, and Europe. Furthermore, shorter follow‐up durations were associated with more pronounced effects on wound healing, highlighting the advantages of rapid wound closure. In addition, we found that APCs treatment appeared to be more effective for wounds on the feet than on the legs, and PRP demonstrated superior efficacy compared with PRF in this regard. However, the wound healing time did not differ significantly between the APCs group and the control group, and there was no indication of increased risk for infection associated with APCs treatment.

Previous reports have shown promising results for APCs therapy in accelerating the healing of chronic wounds. 11 , 25 By delivering PRP or PRF to wounds, the abundance of growth factors can be utilized to expedite healing and promote larger healing areas in various types of skin wounds. 10 , 26 A meta‐analysis conducted by Ebrahimi et al. assessed the efficacy of PRP, either alone or in combination with other modalities, for managing atrophic or hypertrophic/keloidal scars. 27 Similarly, Tasmania et al. reported the effectiveness of PRP in reducing the wound area of diabetic foot ulcers compared with conventional treatment alone, 28 which aligns with our findings. However, other studies failed to identify significant differences or positive effects. 12 , 29 , 30 Numerous factors influence the role of APCs in wound healing, including frequency of use, duration of follow‐up, and preparation method. 28

Although the utilization of APCs varied across regions, our findings suggest that the efficacy of APCs therapy was most prominent in Africa. Helmy et al. conducted a study in Egypt involving 80 participants, demonstrating a 94.85% reduction in wound size in the APCs group compared to 80.89% in the control group. 21 Conversely, a study conducted in America indicated that hydrocolloid treatment was more beneficial for wound healing than APCs (70% vs. 64%). 16 Furthermore, our results indicated that the effect of PRP on wound reduction was more noticeable in patients followed up for less than 4 weeks. For instance, one study reported an 85.15% reduction in wound area in the APCs group at week 4 compared with 34.5% in the control group, 21 while another study revealed reductions of 67.7% and 11.2% in the APCs group, respectively, after 24 weeks of treatment, 15 suggesting that the effect of APCs on wound reduction is not necessarily greater with longer follow‐up periods. In addition, our results showed that PRP was more effective in reducing wounds on the feet than on the legs. A randomized controlled study on diabetic foot ulcers presented a proportion of area reduction approximately eight‐fold greater in the control group (71.9% vs. 9.2%), 19 whereas another study on venous leg ulcers showed a reduction in ulcer area of less than 30% (26.2% in the APCs group vs. 15.2% in the conventional group). 17 Moreover, some studies have suggested that PRF contains higher levels of growth factors than PRP. 31 However, a study by Pravin et al. comparing PRF to PRP dressings in the management of skin ulcers found that more ulcers completely healed in the PRF group compared to the PRP group, 32 which contradicts our findings. This discrepancy may be attributed to the slow release of growth factors by PRF and the inactivation of certain growth factors by protein‐digesting enzymes in the chronic wound environment, resulting in insufficient concentrations of growth factors to facilitate wound repair. The tubular structure of PRF may hinder the migration, proliferation, and differentiation of reparative cells. 33

Despite reports indicating that APCs usage can expedite wound healing, 34 our study did not find a similar association. Healing time have been shown to lack a clear relationship with ulcer area, and venous ulcers have been found to exhibit a significant negative effect on healing speed. 35 Furthermore, our results revealed that the use of PRP did not increase the incidence of infection. Notably, two studies indicated that PRP may reduce the occurrence of adverse events. However, the limited number of articles included in this paper may have contributed to these discrepancies. 28 , 36

Platelet concentrates offer not only wound healing and tissue regeneration benefits but also aid in pain reduction and infection prevention during treatment. 13 , 37 However, the precise mechanism of action of growth factors within APCs in different wound types and stages of wound healing remains unclear. Furthermore, the influence of platelet activation and potential adverse reactions associated with the preparation of certain APCs products require further elucidation, along with the establishment of standardized preparation protocols. 38 Moreover, other components present in APCs, such as blood‐derived proteins and lipids, have also been shown to promote wound healing, 39 , 40 but their mechanisms of action remain unclear. Consequently, larger, high‐quality RCTs are necessary to provide more robust evidence.

Several important limitations need to be addressed. First, our analysis did not encompass a comprehensive and exhaustive collection of studies due to limitations in our search strategy, which is a common drawback in systematic reviews. Second, certain outcome indicators reported in previous studies, such as the rate of complete wound closure, recurrence rate, treatment cost, and pain levels, were not included in our analysis, leading to statistical incompleteness. Third, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, which may have introduced bias. Moreover, treatment durations varied across different studies, further contributing to potential biases. Finally, our sample size was relatively small, emphasizing the need for larger, well‐designed RCTs to yield more robust evidence. Addressing these limitations in future studies will provide more comprehensive insights into the effectiveness of APCs therapy.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our study findings elucidate the efficacy of APCs in promoting accelerated wound reduction while concurrently minimizing the occurrence of infection. Notably, we observed variations in the influence of wound locations, types of APCs employed, and durations of follow‐up on the extent of wound area reduction. Nonetheless, it is imperative to emphasize the necessity for more substantial evidence substantiating the impact of APCs on wound area reduction. To achieve this, rigorous clinical trials encompassing a large sample size and adherence to a standardized treatment protocol are warranted.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Mianyang Municipal Health Commission Research Project (Grant No. 201989).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Search Strategy.

Figure S1. Risk of bias graph.

Figure S2. Egger's test of included studies.

Tang B, Huang Z, Zheng X. Impact of autologous platelet concentrates on wound area reduction: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Wound J. 2023;20(10):4384‐4393. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14310

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goda AA. Autogenous leucocyte‐rich and platelet‐rich fibrin for the treatment of leg venous ulcer: a randomized control study. Egypt J Surg. 2018;37:316‐321.29. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong DG, Marston WA, Reyzelman AM, Kirsner RS. Comparative effectiveness of mechanically and electrically powered negative pressure wound therapy devices: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:332‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Badran Z, Abdallah MN, Torres J, Tamimi F. Platelet concentrates for bone regeneration: current evidence and future challenges. Platelets. 2018;29(2):105‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Everts PA, Pinto PC, Girão L. Autologous pure platelet‐rich plasma injections for facial skin rejuvenation: biometric instrumental evaluations and patient‐reported outcomes to support antiaging effects. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(4):985‐995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Na J‐I, Choi J‐W, Choi H‐R, et al. Rapid healing and reduced erythema after ablative fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing combined with the application of autologous platelet‐rich plasma. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:463‐468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yuan T, Zhang CQ, Tang MJ, Guo SC, Zeng BF. Autologous platelet‐rich plasma enhances healing of chronic wounds[J]. Wounds. 2009;21(10):280‐285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirn DH, Je YJ, Lee K, et al. Can platelet‐rich plasma be used for skin rejuvenation? Evaluation of effects of platelet‐rich plasma on human dermal fibroblast. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(4):424‐431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Redaelli A. Face and neck revitalization with platelet‐rich plasma (PRP): clinical outcome in a series of 23 consecutively treated patients. J Drug Dermatol. 2010;9(5):466‐467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans AG, Ivanic MG, Botros MA, et al. Rejuvenating the periorbital area using platelet‐rich plasma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021;313(9):711‐727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karimi K, Rockwell H. The benefits of platelet‐rich fibrin. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(3):331‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen J, Wan Y, Lin Y, Jiang H. Platelet‐rich fibrin and concentrated growth factors as novel platelet concentrates for chronic hard‐to‐heal skin ulcers: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(2):613‐621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yuvasri G, Rai R. Comparison of efficacy of autologous platelet‐rich fibrin versus Unna's paste dressing in chronic venous leg ulcers: a comparative study. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11:58‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaheb M, Karrabi M, Khajeh M, Asadi A, Shahrestanaki E, Sahebkar M. Evaluation of the effect of platelet‐rich fibrin on wound healing at Split‐thickness skin graft donor sites: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, triple‐blind study. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2021;20(1):29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moneib HA, Youssef SS, Aly DG, Rizk MA, Abdelhakeem YI. Autologous platelet‐rich plasma versus conventional therapy for the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers: a comparative study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(3):495‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Escamilla Cardeñosa M, Domínguez‐Maldonado G, Córdoba‐Fernández A. Efficacy and safety of the use of platelet‐rich plasma to manage venous ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2017;26(2):138‐143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oliveira MG, Abbade LPF, Miot HA, Ferreira RR, Deffune E. Pilot study of homologous platelet gel in venous ulcers. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(4):499‐504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Senet P, Bon FX, Benbunan M, et al. Randomized trial and local biological effect of autologous platelets used as adjuvant therapy for chronic venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(6):1342‐1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Somani A, Rai R. Comparison of efficacy of autologous platelet‐rich fibrin versus saline dressing in chronic venous leg ulcers: a randomised controlled trial. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2017;10:8‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saldalamacchia G, Lapice E, Cuomo V, et al. A controlled study of the use of autologous platelet gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;14(6):395‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Helmy Y, Farouk N, Ali Dahy A, et al. Objective assessment of platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) potentiality in the treatment of chronic leg ulcer: RCT on 80 patients with venous ulcer. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(10):3257‐3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hossam EM, Alserr AHK, Antonopoulos CN, Zaki A, Eldaly W. Autologous platelet rich plasma promotes the healing of non‐ischemic diabetic foot ulcers. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022;82:165‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rainys D, Cepas A, Dambrauskaite K, Nedzelskiene I, Rimdeika R. Effectiveness of autologous platelet‐rich plasma gel in the treatment of hard‐to‐heal leg ulcers: a randomised control trial. J Wound Care. 2019;28(10):658‐667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramos‐Torrecillas J, García‐Martínez O, de Luna‐Bertos E, Ocaña‐Peinado FM, Ruiz C. Effectiveness of platelet‐rich plasma and hyaluronic acid for the treatment and care of pressure ulcers. Biol Res Nurs. 2015;17(2):152‐158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Driver VR, Hanft J, Fylling CP, Beriou JM, Autologel diabetic foot ulcer study group . A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous platelet‐rich plasma gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006;52(6):68‐70. 72, 74. Ostomy/wound management. 52. 68–70, 72, 74 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martinez‐Zapata MJ, Martí‐Carvajal AJ, Solà I, et al. Autologous platelet‐rich plasma for treating chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(5):CD006899 Published 2016 May 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolton L. Platelet‐rich plasma: optimal use in surgical wounds. Wounds. 2021;33(8):219‐221. PMID: 34357880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebrahimi Z, Alimohamadi Y, Janani M, Hejazi P, Kamali M, Goodarzi A. Platelet‐rich plasma in the treatment of scars, to suggest or not to suggest? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022;16(10):875‐899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. del Pino‐Sedeño T, Trujillo‐Martín MM, Andia I, et al. Platelet‐rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a meta‐analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2019;27(2):170‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burgos‐Alonso N, Lobato I, Hernández I, et al. Adjuvant biological therapies in chronic leg ulcers. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2561 Published 2017 Nov 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet‐rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(8):1742‐1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qiao J, An N, Ouyang X. Quantification of growth factors in different platelet concentrates. Platelets. 2017;28(8):774‐778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pravin AJS, Sridhar V, Srinivasan BN. Autologous platelet rich plasma (prp) versus leucocyte‐platelet rich fibrin (l‐prf) in chronic non‐healing leg ulcers – a randomised, open labelled, comparative study. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2016;5(102):7460‐7462. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang CQ, Yuan T. The controversy and research progress of platelet‐rich plasma in clinical application. Chin J Joint Surg: Electronic Edition. 2016;10(6):4. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zheng W, Zhao DL, Zhao YQ, Li ZY. Effectiveness of platelet rich plasma in burn wound healing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(1):131‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shen Z, Zheng S, Chen G, et al. Efficacy and safety of platelet‐rich plasma in treating cutaneous ulceration: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(2):495‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang H, Sun X, Zhao Y. Platelet‐rich plasma for the treatment of burn wounds: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;60(1):102964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reksodiputro MH, Hutauruk SM, Widodo DW, Fardizza F, Mutia D. Platelet‐rich fibrin enhances surgical wound healing in total laryngectomy. Facial Plast Surg. 2021;37(3):325‐332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Villela DL, Santos VL. Evidence on the use of platelet‐rich plasma for diabetic ulcer: a systematic review. Growth Factors. 2010;28(2):111‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yaprak E, Kasap M, Akpinar G, Islek EE, Sinanoglu A. Abundant proteins in platelet‐rich fibrin and their potential contribution to wound healing: An explorative proteomics study and review of the literature. J Dent Sci. 2018;13(4):386‐395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoeferlin LA, Huynh QK, Mietla JA, et al. The lipid portion of activated platelet‐rich plasma significantly contributes to its wound healing properties. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4(2):100‐109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search Strategy.

Figure S1. Risk of bias graph.

Figure S2. Egger's test of included studies.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.