Introduction

Liver transplantation is an effective treatment for end-stage liver disease1–3, but the shortage of available organs means that not all patients can undergo the procedure4. This is especially true for patients with low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) or MELD incorporating sodium level (MELD-Na) scores, as the organ allocation policy is based on these scores5–7. As a result, patients with low MELD or MELD-Na scores face a limited chance of receiving a deceased donor liver transplant, leading to high mortality rates. In the USA, the 5-year cumulative incidence of mortality rates for low MELD-Na patients (scores ≤15) can be as high as 18.6 per cent8. To address the organ shortage, living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) has emerged particularly in East Asian countries9, and more than half of the LDLT recipients in Korea over the past 5 years had MELD scores ≤1510.

A recent study using the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database from the USA found that LDLT was associated with a survival benefit in patients with MELD-Na scores as low as 1111. Given the extensive experience of Eastern expert centres in performing LDLT over the past three decades, this study was designed to determine the survival benefit of LDLT in patients with end-stage liver disease compared with best supportive care (BSC).

Methods

This retrospective study included patients aged 18 years or older who were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, between January 2001 and June 2022. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma at the time of diagnosis, previous or current transplantation, deceased donor transplantation or multiple organ transplantation were excluded. The study compared the effects of LDLT on patient survival with BSC.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), aetiology and lab findings, including serum creatinine, sodium, bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR) and dialysis prescription history, were collected and used to calculate the MELD-Na scores of each patient at the diagnosis of cirrhosis for BSC or at the time of transplant for LDLT. Patients with MELD-Na scores ranging from 21 to 40 were excluded from the analysis and all included participants were stratified by MELD-Na score at: 6–10, 11–12, 13–14, 15–16, 17–18 and 19–20. A detailed description of the statistical analysis and ethical approval can be found in the Supplementary material. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (SMC 2022-09-036-001).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Of 10 005 patients included in the study, 272 underwent LDLT and 9733 were treated with BSC (Fig. S1, Table S1). The LDLT group was younger (51.6 ± 9.3 versus 58.0 ± 11.5 years old, P <0.001) and the most common cause of cirrhosis in both groups was hepatitis B virus-related (HBV) cirrhosis (129 (47.4 per cent) versus 4403 (45.2 per cent)), but the proportion of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis was higher in the LDLT group (56 (20.6 per cent) versus 1199 (12.3 per cent), P <0.001). The LDLT group also had higher mean MELD-Na (14.3 ± 3.6 versus 9.7 ± 4.2, P <0.001) and MELD (13.6 ± 3.3 versus 8.4 ± 3.1, P <0.001) scores. Regarding mortality rates, within 100 days, there were 13 deaths (4.8 per cent) in the LDLT group compared with 158 deaths (1.6 per cent) in the BSC group after diagnosis of cirrhosis. There were four deaths following LDLT within 100 days after surgery in the MELD-Na score 11–12 group and they were due to hepatic artery occlusion, hepatic vein stricture, hepaticojejunostomy disruption and massive bleeding due to previous abdominal surgery that resulted in metabolic acidosis. The LDLT group experienced 30 deaths (11.0 per cent) compared with 773 deaths (7.9 per cent) in the BSC group within 1000 days. When stratified by MELD-Na scores, the MELD scores of the LDLT group were higher in every subgroup, but the MELD-Na scores were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics based on MELD-Na stratification

| MELD-Na 6–10 | MELD-Na 11–12 | MELD-Na 13–14 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | LDLT | P | BSC | LDLT | P | BSC | LDLT | P | |

| n | 6521 | 45 | 940 | 41 | 721 | 42 | |||

| Age (years), mean (s.d.) | 57.5 (11.4) | 49.5 (11.3) | <0.001 | 58.3 (11.7) | 52.2 (9.4) | <0.001 | 58.8 (11.7) | 52.8 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 3964 (60.8) | 29 (64.4) | 0.728 | 739 (78.6) | 26 (63.4) | 0.035 | 561 (77.8) | 26 (61.9) | 0.029 |

| Female | 2557 (39.2) | 16 (35.6) | 201 (21.4) | 15 (36.6) | 160 (22.2) | 16 (38.1) | |||

| BMI, mean (s.d.) | 25.3 (3.3) | 24.0 (3.8) | 0.022 | 25.5 (3.1) | 24.6 (4.2) | 0.195 | 25.5 (3.5) | 24.0 (3.9) | 0.018 |

| Aetiology | |||||||||

| HBV | 3147 (48.3) | 14 (31.1) | 0.042 | 412 (43.8) | 19 (46.3) | 0.726 | 290 (40.2) | 22 (52.4) | 0.021 |

| HCV | 492 (7.5) | 3 (6.7) | 91 (9.7) | 2 (4.9) | 72 (10.0) | 1 (2.4) | |||

| Alcohol | 638 (9.8) | 9 (20.0) | 127 (13.5) | 7 (17.1) | 129 (17.9) | 12 (28.6) | |||

| Others | 2244 (34.4) | 19 (42.2) | 310 (33.0) | 13 (31.7) | 230 (31.9) | 7 (16.7) | |||

| MELD, mean (s.d.) | 6.8 (1.2) | 8.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 9.6 (2.3) | 11.5 (0.6) | <0.001 | 10.7 (2.8) | 13.2 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| MELD-Na, mean (s.d.) | 7.1 (1.4) | 8.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 11.5 (0.5) | 11.5 (0.5) | 0.477 | 13.5 (0.5) | 13.6 (0.5) | 0.065 |

| 100-Day mortality rate | 34 (0.5) | 2 (4.4) | 0.011 | 26 (2.8) | 4 (9.8) | 0.037 | 19 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.578 |

| 1000-Day mortality rate | 236 (3.6) | 4 (8.9) | 0.139 | 107 (11.4) | 6 (14.6) | 0.698 | 101 (14.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0.055 |

| MELD-Na 15–16 | MELD-Na 17–18 | MELD-Na 19–20 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | LDLT | P | BSC | LDLT | P | BSC | LDLT | P | |

| n | 566 | 65 | 516 | 45 | 469 | 34 | |||

| Age (years), mean (s.d.) | 59.9 (11.4) | 53.0 (8.4) | <0.001 | 59.7 (11.9) | 50.2 (9.5) | <0.001 | 59.6 (11.6) | 51.2 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 434 (76.7) | 47 (72.3) | 0.529 | 391 (75.8) | 26 (57.8) | 0.013 | 354 (75.5) | 22 (64.7) | 0.233 |

| Female | 132 (23.3) | 18 (27.7) | 125 (24.2) | 19 (42.2) | 115 (24.5) | 12 (35.3) | |||

| BMI, mean (s.d.) | 25.4 (3.4) | 24.4 (3.1) | 0.012 | 25.2 (3.4) | 24.3 (4.5) | 0.199 | 25.3 (3.3) | 23.9 (4.1) | 0.07 |

| Aetiology | |||||||||

| HBV | 229 (40.5) | 36 (55.4) | 0.025 | 185 (35.9) | 20 (44.4) | 0.667 | 140 (29.9) | 18 (52.9) | 0.023 |

| HCV | 48 (8.5) | 5 (7.7) | 41 (7.9) | 2 (4.4) | 36 (7.7) | 2 (5.9) | |||

| Alcohol | 102 (18.0) | 14 (21.5) | 103 (20.0) | 7 (15.6) | 100 (21.3) | 7 (20.6) | |||

| Others | 187 (33.0) | 10 (15.4) | 187 (36.2) | 16 (35.6) | 193 (41.2) | 7 (20.6) | |||

| MELD, mean (s.d.) | 11.5 (3.6) | 14.8 (1.4) | <0.001 | 12.5 (4.0) | 16.2 (2.3) | <0.001 | 12.9 (4.3) | 17.6 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| MELD-Na, mean (s.d.) | 15.5 (0.5) | 15.5 (0.5) | 0.773 | 17.5 (0.5) | 17.5 (0.5) | 0.663 | 19.5 (0.5) | 19.4 (0.5) | 0.074 |

| 100-Day mortality rate | 19 (3.4) | 2 (3.1) | 0.999 | 28 (5.4) | 3 (6.7) | 0.993 | 32 (6.8) | 2 (5.9) | 0.999 |

| 1000-Day mortality rate | 94 (16.6) | 5 (7.7) | 0.091 | 102 (19.8) | 7 (15.6) | 0.625 | 133 (28.4) | 7 (20.6) | 0.437 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. BSC, best supportive care; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; MELD-Na, model for end-stage liver disease incorporating sodium levels; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Survival probabilities and hazard ratio based on MELD-Na score

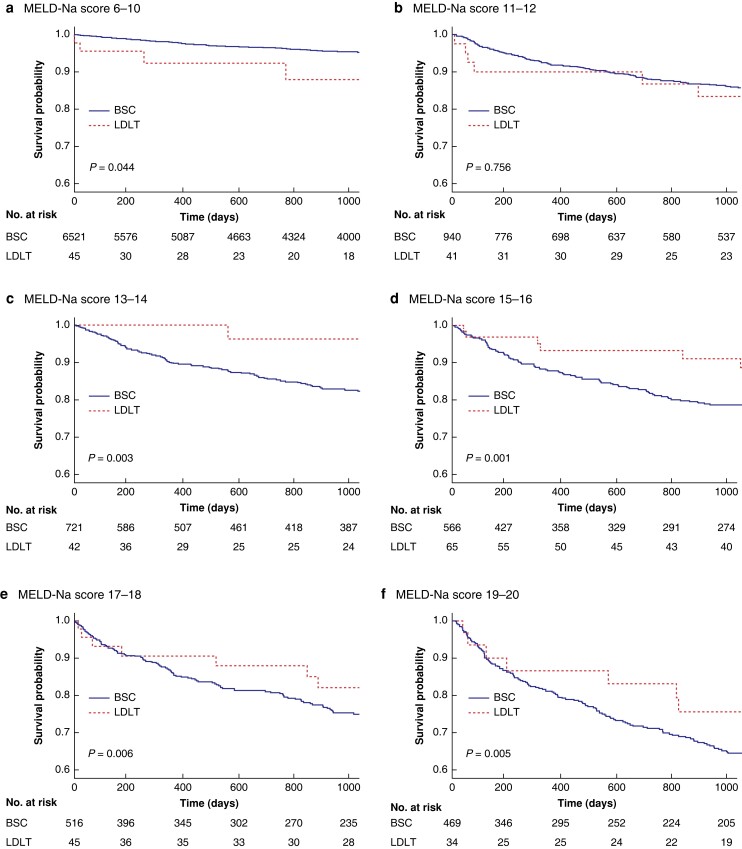

Survival probabilities of LDLT and BSC were compared based on stratified MELD-Na scores (Fig. 1). For patients with MELD-Na scores of 13 or higher, there was a survival benefit of LDLT (MELD-Na scores 13–14, 96.3 per cent versus 82.7 per cent, P = 0.003, Fig. 1c, 1000-day survival probabilities respectively). On the other hand, LDLT showed inferior survival compared with BSC in patients with MELD-Na scores of 6–10 (88.0 per cent versus 95.5 per cent, P = 0.044, 1000-day survival probabilities respectively, Fig. 1a) and there was no survival benefit of LDLT over BSC in patients with MELD-Na scores of 11–12 (83.4 per cent versus 86.2 per cent, P = 0.756, 1000-day survival probabilities respectively, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of survival probabilities based on MELD-Na scores (zero time point is the time of diagnosis of liver cirrhosis for the BSC group or transplantation for the LDLT group, 1000-day survival probabilities respectively) a, MELD-Na 6–10 (88.0 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 82.1 per cent–93.9 per cent) versus 95.5 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 95.2 per cent–95.8 per cent), P = 0.044). b, MELD-Na 11–12 (83.4 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 77.1 per cent–89.7 per cent) versus 86.2 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 85.0 per cent–87.4 per cent), P = 0.756). c, MELD-Na 13–14 (96.3 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 92.7 per cent–99.9 per cent) versus 82.7 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 81.1 per cent–84.3 per cent), P = 0.003). d, MELD-Na 15–16 (91.0 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 87.1 per cent–94.9 per cent) versus 78.6 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 76.6 per cent–80.6 per cent), P = 0.001). e, MELD-Na 17–18 (82.0 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 75.8 per cent–88.2 per cent) versus 75.3 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 73.1 per cent–77.5 per cent), P = 0.006). f, MELD-Na 19–20 (75.6 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 67.5 per cent–83.7 per cent) versus 65.2 per cent (95 per cent c.i., 62.7 per cent–67.7 per cent), P = 0.005). MELD-Na, model for end-stage liver disease incorporating sodium levels; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; BSC, best supportive care.

Covariate-adjusted mortality risk models confirmed the survival benefit of LDLT over BSC from MELD-Na scores as low as 13 (MELD-Na scores 11–12, HR 1.22 (95 per cent c.i. 0.59–2.5), P = 0.595; MELD-Na scores 13–14, HR 0.2 (95 per cent c.i. 0.05–0.8), P = 0.023, Table S2, Fig. S2).

Discussion

This retrospective single-centre study was designed to evaluate the survival benefit of LDLT in patients with end-stage liver disease. The severity of cirrhosis was measured using MELD-Na scores. The results show that the LDLT has survival benefit when MELD-Na scores are ≥13, with superior survival probability and a significantly lower covariate-adjusted mortality rate. On the other hand, the probability of death from LDLT for patients with very low MELD-Na scores (6–10) was greater and covariate-adjusted mortality risk was also higher.

Recently, Jackson et al. reported that LDLT is associated with survival benefit for patients with end-stage liver disease at MELD-Na scores as low as 1111. The study compared the survival probabilities of recipients of LDLT and patients assigned to the waitlist from the SRTR database in the USA. The 900-day survival probability of an LDLT recipient was 90 per cent, while it was 75 per cent for patients on the waitlist with MELD-Na scores of 11–13. In contrast, the result from this study found that the 1000-day survival probability of LDLT recipients was 83.4 per cent, and that of BSC was 86.2 per cent in patients with MELD-Na scores of 11–12. The difference in survival probabilities of the control group resulted in different cutoff values, where a distinct survival benefit for LDLT begins in terms of the MELD-Na score. The 83.4 per cent survival probability for LDLT recipients in the MELD-Na 11–12 group in our centre surpassed 75 per cent survival probability of patients on the SRTR waitlist, which indicates a survival benefit of LDLT at a MELD-Na score as low as 11.

Every cause of death following LDLT within 100 days after surgery in the MELD-Na score 11–12 group was related to surgical procedures. This suggests that complications associated with surgical procedures may negate the potential survival benefit of LDLT, particularly for those with low MELD-Na scores. Therefore, the potential risks associated with surgical procedures should be carefully evaluated when deciding to perform LDLT in patients with low MELD-Na scores.

Several limitations of this study are acknowledged. The study design is retrospective and conducted at a single centre, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Our clinical data warehouse prevented us from providing detailed information regarding the aetiology of liver disease in our ‘other indications’ group, and we were unable to access information on the reason for patients not being candidates for transplantation in the BSC group and the cause of death in this group.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Namkee Oh, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jong Man Kim, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Seungwook Han, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Sung Jun Jo, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Sunghyo An, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Sunghae Park, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Sang Oh Yoon, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jaehun Yang, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jieun Kwon, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Nuri Lee, Department of Surgery, Veterans Health Service Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jinsoo Rhu, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Gyu-Seong Choi, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jae-Won Joh, Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Funding

This study was supported by Future Medicine 2030 Project of the Samsung Medical Center (SMX1230771).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Namkee Oh (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Jong Man Kim (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—review & editing), Seungwook Han (Investigation), Sung Jun Jo (Investigation), Sunghyo An (Investigation), Sunghae Park (Investigation), Sang Oh Yun (Investigation), Jaehum Yang (Investigation), Ji Eun Kwon (Investigation), Nuri Lee (Investigation), Jinsoo Rhu (Investigation), Gyu Seong Choi (Investigation) and Jae Won Joh (Investigation).

References

- 1. Merion RM, Schaubel DE, Dykstra DM, Freeman RB, Port FK, Wolfe RA. The survival benefit of liver transplantation. Am J Transplantat 2005;5:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berg CL, Merion RM, Shearon TH, Olthoff KM, Brown RS Jr, Baker TB et al. Liver transplant recipient survival benefit with living donation in the model for endstage liver disease allocation era. Hepatology 2011;54:1313–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kwong AJ, Lai JC, Dodge JL, Roberts JP. Outcomes for liver transplant candidates listed with low model for end-stage liver disease score. Liver Transpl 2015;21:1403–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwong AJ, Ebel NH, Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Schladt DP et al. OPTN/SRTR 2020 annual data report: liver. Am J Transplant 2022;22 Supp 2:204–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asrani SK, Kim WR. Organ allocation for chronic liver disease: model for end-stage liver disease and beyond. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park HS, Lee J-M, Hong K, Han ES, Hong SK, Choi Y et al. Impact of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease allocation system on outcomes of deceased donor liver transplantation: a single-center experience. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2021;25:336–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goudsmit BFJ, Putter H, Tushuizen ME, de Boer J, Vogelaar S, Alwayn I et al. Validation of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease sodium (MELD-Na) score in the Eurotransplant region. Am J Transplant 2021;21:229–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atiemo K, Skaro A, Maddur H, Zhao L, Montag S, VanWagner L et al. Mortality risk factors among patients with cirrhosis and a low model for end-stage liver disease sodium score (≤15): an analysis of liver transplant allocation policy using aggregated electronic health record data. Am J Transplant 2017;17:2410–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rela M, Rammohan A. Why are there so many liver transplants from living donors in Asia and so few in Europe and the US? J Hepatol 2021;75:975–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Health, The Korean Society of Transplantation, Korean Organ Transplant Registry, KOTRY annual data report. 2021

- 11. Jackson WE, Malamon JS, Kaplan B, Saben JL, Schold JD, Pomposelli JJ et al. Survival benefit of living-donor liver transplant. JAMA Surg 2022;157:926–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.