Abstract

Conditions that resulted in unstable expression and heat instability of a cell surface epitope associated with a 66-kDa antigen in Listeria monocytogenes serotypes were identified with the probe monoclonal antibody (MAb) EM-7G1 in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. This epitope appeared to be absent in three serotypes (serotypes 3b, 4a, and 4c), which did not react with MAb EM-7G1 irrespective of the enrichment broth tested. The remaining 10 serotypes were detected by MAb EM-7G1 only when cells were grown in nonselective brain heart infusion broth (BHI) or selective Listeria enrichment broth (LEB). When cells were grown in Listeria repair broth (LRB), only 6 of the 13 serotypes were detected by MAb EM-7G1, and recognition of serogroup 4 was completely lost. None of the 13 serotypes was detected by MAb EM-7G1 when cells were grown in two other commonly used Listeria-selective media, UVM1 broth and Fraser broth (FRB), indicating that possible loss of epitope expression occurred under these conditions. MAb EM-7G1 maintained species specificity without cross-reacting with live or heat-killed cells of six other Listeria spp. (Listeria ivanovii, Listeria innocua, Listeria seeligeri, Listeria welshimeri, Listeria grayi, and Listeria murrayi) irrespective of the enrichment conditions tested. Due to heat instability of the cell surface epitope when it was exposed to 80 or 100°C for 20 min, MAb EM-7G1 is suitable for detection of live cells of L. monocytogenes in BHI or LEB but not in LRB, UVM1, or FRB enrichment medium.

Many antibody probes (2) that recognize genus-specific Listeria antigens have been developed based on cell surface antigens (4, 7, 12, 18, 28, 29), intracellular antigens (14, 16), extracellular toxins (15, 24), or flagellar antigens (10, 11). However, only limited success has been achieved in efforts to develop species-specific polyclonal antibody (PAb) or monoclonal antibody (MAb) probes capable of distinguishing Listeria monocytogenes from nonpathogenic Listeria species (2, 14). PAbs raised against a unique sequence of p60 (5) or against a 90-kDa ActA protein (25) have been proved to be specific for L. monocytogenes, but the usefulness of these PAbs in diagnostic assays has not been determined yet. A species-specific MAb probe for L. monocytogenes, MAb EM-7G1, was developed previously in our laboratory (3). MAb EM-7G1 recognizes an epitope on a 66-kDa cell surface antigen of L. monocytogenes, which was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blot analysis of crude cell surface proteins (3). In the present study, the reactivity patterns of MAb EM-7G1 were fully characterized with all serotypes of L. monocytogenes and with other Listeria species by using both live and heat-killed cells in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The main objective of this study was to identify growth and assay conditions under which this MAb probe can recognize the greatest number of serotypes of L. monocytogenes in the ELISA. All antibody-based detection methods require enrichment of bacterial cells prior to detection. In protocols devised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service (9, 19) and the Food and Drug Administration (13, 17) different selective enrichment media are used for isolation of L. monocytogenes from suspect food samples. Enrichments of samples in Listeria-selective media are widely used in conjunction with antibody-based Listeria diagnostic assays. Production of some Listeria antigens recognized by antibody probes (e.g., hemolysin or flagellar antigens) has been shown to be affected by the growth conditions, including temperature, pH, and the salt or preservatives present (8, 27). However, it has been widely assumed that cell surface Listeria antigens are stably produced irrespective of the culture conditions. In this report, we identify for the first time conditions that result in unstable expression of a cell surface epitope associated with the 66-kDa species-specific antigen in L. monocytogenes. This information should enable accurate use of MAb EM-7G1 as a probe in a diagnostic assay for L. monocytogenes.

(Part of this work was presented previously at the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology [22] and at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the International Association of Milk, Food and Environmental Sanitarians [21].)

Growth of L. monocytogenes serotypes.

The 21 strains representing all six Listeria species and 13 serotypes of L. monocytogenes selected for this study are listed in Table 1. The following five broth media were used for enrichment of Listeria cells: (i) brain heart infusion broth (BHI), a nonselective growth medium (1); (ii) Listeria repair broth (LRB) to which antibiotic supplements were added 4 h after the initial nonselective enrichment period (6); (iii) Listeria enrichment broth (LEB) (Oxoid Div., Unipath Co., Ogdensburg, N.Y.) (1); (iv) the UVM1 formulation of Listeria enrichment broth (Oxoid Div.) (1, 9); and (v) Fraser broth without ferric ammonium citrate (FRB) (Difco Laboratories) (1). Each of the 21 Listeria strains (Table 1) was inoculated into the broth media (three replicates, 10 ml per strain) by transferring 10-μl portions of a bacterial suspension from a pure culture and was incubated for 24 h at 37°C, which yielded final Listeria concentrations of 108 to 109 CFU/ml. Bacterial cell suspensions (live or heat killed) were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 10-ml portions of 0.1 M carbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) for the ELISA. Heat-killed cells were prepared by heating bacterial cell suspensions at 80 or 100°C for 20 min. All cell preparations were tested concurrently with the same MAb preparation so that we could accurately compare ELISA reactivities. All experiments were repeated three times, and each experiment included five media, 21 strains, and three cell preparations. In a separate experiment, the CFU of L. monocytogenes serotypes 1/2a and 4b were determined after growth for 24 h in different broth media. Concentrations of 3 × 108 to 6 × 108 CFU/ml were achieved within 24 h in UVM1 and FRB, while concentrations of 1 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU/ml were obtained in BHI, LEB, or LRB enrichments.

TABLE 1.

Listeria strains tested

| Species | Serotype | Strain | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. monocytogenes | 1/2a | V7 | FDA |

| L. monocytogenes | 1/2b | F4260 | CDC |

| L. monocytogenes | 1/2c | V2 | VICAM |

| L. monocytogenes | 3a | ATCC 19113 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 3b | ATCC 2540 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 3c | SLCC 2479 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 4a | ATCC 19114 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 4b | Scott A | FDA |

| L. monocytogenes | 4c | ATCC 19116 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 4d | ATCC 19117 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 4e | ATCC 19118 | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes | 4ab | Murray B | FDA |

| L. monocytogenes | 7 | C 2482 | ATCC |

| L. ivanovii | 5 | V12 | VICAM |

| L. innocua | 6a | V11 | VICAM |

| L. innocua | 6b | V24 | VICAM |

| L. innocua | 4ab | V51 | VICAM |

| L. seeligeri | 1/2b | V13 | VICAM |

| L. welshimeri | 6a | V14 | VICAM |

| L. grayi | ATCC 19120 | ATCC | |

| L. murrayi | LM 89 | VICAM |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.; VICAM, VICAM Inc., Watertown, Mass.; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

Determination of 66-kDa-antigen-associated epitope intensity by ELISA.

Live or heat-killed whole Listeria cells (approximately 108 to 109 CFU/ml) collected from each broth medium were immobilized on Immulon-1 microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Chantilly, Va.) in four replicate wells (3) by overnight incubation at 5°C and were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) containing 0.5% Tween 20. The microtiter wells were first probed for 1 h at 37°C with MAb EM-7G1 (1:1,000) in PBS, which bound to the epitope associated with the 66-kDa cell surface antigen, and then they were washed, treated for 1 h at 37°C with goat antimouse immunoglobulin G-peroxidase conjugate (1:2,000 in PBS; Sigma Chemical Co.) as a secondary antibody probe, and washed again. The plates were treated with 10 mg of o-phenylenediamine (Sigma Chemical Co.) in 10 ml of citrate buffer (pH 4.0) supplemented with 10 μl of H2O2, and the reactions were stopped with 2 N H2SO4 after 15 min. Absorbance at 490 nm (A490) was recorded with a model 3550 microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). In all ELISA the reaction volumes were 100 μl/well.

MAb EM-7G1 recognition of L. monocytogenes serotypes grown in BHI, LEB, LRB, UVM1, and FRB.

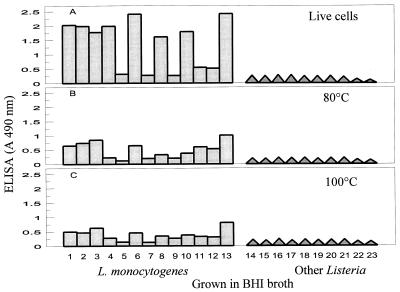

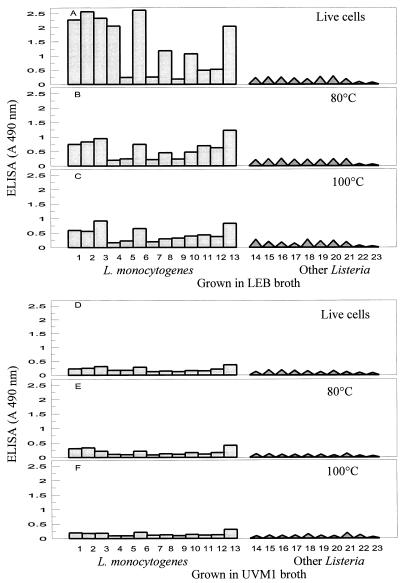

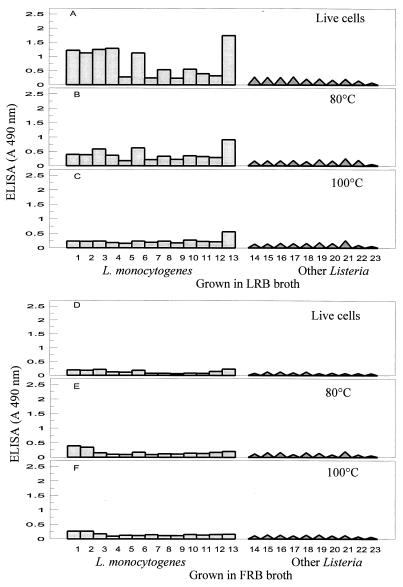

Our results show that the detectability of live L. monocytogenes cells by MAb EM-7G1 in an ELISA depends on the broth medium used for growth of cells prior to testing. MAb EM-7G1 was capable of detecting live cells of only 10 of the 13 serotypes of L. monocytogenes and did not detect serotypes 3b, 4a, and 4c. These patterns were observed when L. monocytogenes strains were grown in either nonselective BHI broth (Fig. 1A) or selective LEB (Fig. 2A) enrichment cultures. Also, MAb EM-7G1 revealed extensive variability in ELISA reactivities among serotypes of L. monocytogenes. With cells obtained from both BHI and LEB enrichments, MAb EM-7G1 exhibited the strongest reactions (A490, 2.0 to 2.5) with serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, 3a, 3c, and 7, moderate reactions (A490, 1.0 to 2.0) with serotypes 4b and 4d, and extremely weak reactions (A490, 0.5) with serotypes 4e and 4ab (Fig. 1A and 2A). When cells were grown in LRB, MAb EM-7G1 detected live cells of only 6 of the 13 serotypes of L. monocytogenes (Fig. 3A), exhibiting strong ELISA reactivity (A490, 2.0) with only one serotype, serotype 7, and moderate reactivities (A490, 1 to 1.5) with five other serotypes (serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, 3a, and 3c). Extremely weak reactivities were observed with all members of serogroup 4 from LRB enrichment cultures. By contrast, MAb EM-7G1 failed to react (A490, <0.3) with live cells of any of the 13 serotypes of L. monocytogenes from UVM1 (Fig. 2D) or FRB (Fig. 3D) enrichment cultures, confirming that this MAb probe is not suitable for use in conjunction with the latter two enrichment media, which are routinely recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (9, 19) or the Food and Drug Administration (13, 17) for use with L. monocytogenes. MAb EM-7G1 remained species specific for L. monocytogenes, without cross-reacting with live or heat-killed cells of six other Listeria spp. (Listeria ivanovii, Listeria innocua, Listeria seeligeri, Listeria welshimeri, Listeria grayi, and Listeria murrayi), irrespective of the enrichment media tested (Fig. 1 through 3). Substantial decreases in ELISA reactivities were noted for MAb EM-7G1 irrespective of the enrichment broth tested for all serotypes of L. monocytogenes subjected to both heat treatments, 80°C (Fig. 1B, 2B and E, and 3B and E) and 100°C (Fig. 1C, 2C and F, and 3C and F), for 20 min, suggesting that the 66-kDa-antigen-associated epitope may not be heat stable.

FIG. 1.

MAb EM-7G1 reactivities with live and heat-killed cells of different serotypes of L. monocytogenes (lanes 1 through 13) and with other Listeria spp. (lanes 14 through 21) grown in BHI prior to ELISA. Lanes 1 to 13 show the results for the following L. monocytogenes serotypes: lane 1, 1/2a; lane 2, 1/2b; lane 3, 1/2c; lane 4, 3a; lane 5, 3b; lane 6, 3c; lane 7, 4a; lane 8, 4b; lane 9, 4c; lane 10, 4d; lane 11, 4e; lane 12, 4ab; and lane 13, 7. Lane 14, L. ivanovii; lane 15, L. innocua serotype 6a; lane 16, L. innocua serotype 6b; lane 17, L. innocua serotype 4ab; lane 18, L. seeligeri; lane 19, L. welshimeri; lane 20, L. grayi; lane 21, L. murrayi; lane 22, broth alone; lane 23, PBS alone. A 490 nm, absorbance at 490 nm.

FIG. 2.

MAb EM-7G1 reactivities with live and heat-killed cells of different serotypes of L. monocytogenes (lanes 1 through 13) and with other Listeria spp. (lanes 14 through 21) grown in LEB or UVM1 prior to ELISA. Lanes 1 to 13 show the results for the following L. monocytogenes serotypes: lane 1, 1/2a; lane 2, 1/2b; lane 3, 1/2c; lane 4, 3a; lane 5, 3b; lane 6, 3c; lane 7, 4a; lane 8, 4b; lane 9, 4c; lane 10, 4d; lane 11, 4e; lane 12, 4ab; lane 13, 7. Lane 14, L. ivanovii; lane 15, L. innocua serotype 6a; lane 16, L. innocua serotype 6b; lane 17, L. innocua serotype 4ab; lane 18, L. seeligeri; lane 19, L. welshimeri; lane 20, L. grayi; lane 21, L. murrayi; lane 22, broth alone; lane 23, PBS alone. A 490 nm, absorbance at 490 nm.

FIG. 3.

MAb EM-7G1 reactivities with live and heat-killed cells of different serotypes of L. monocytogenes (lanes 1 through 13) and with other Listeria spp. (lanes 14 through 21) grown in LRB or FRB prior to ELISA. Lanes 1 to 13 show the results for the following L. monocytogenes serotypes: lane 1, 1/2a; lane 2, 1/2b; lane 3, 1/2c; lane 4, 3a; lane 5, 3b; lane 6, 3c; lane 7, 4a; lane 8, 4b; lane 9, 4c; lane 10, 4d; lane 11, 4e; lane 12, 4ab; lane 13, 7. Lane 14, L. ivanovii; lane 15, L. innocua serotype 6a; lane 16, L. innocua serotype 6b; lane 17, L. innocua serotype 4ab; lane 18, L. seeligeri; lane 19, L. welshimeri; lane 20, L. grayi; lane 21, L. murrayi; lane 22, broth alone; lane 23, PBS alone. A 490 nm, absorbance at 490 nm.

As a result of its strong ELISA reactivities with some serotypes (serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, 3a, 3c, and 7) and weak reactivities with other serotypes (serotypes 4e and 4ab) when BHI or LEB enrichments were examined (Fig. 1A and 2A), MAb EM-7G1 is not appropriate for enumeration of L. monocytogenes cells based on a ELISA standard curve derived from a single serotype. Considering this limitation, MAb EM-7G1 is appropriate only for detecting the presence or absence of L. monocytogenes by ELISA. Although MAb EM-7G1 was not able to detect all serotypes, it appears to be suitable for detecting the three predominant serotypes of L. monocytogenes (serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) often associated with human listeriosis outbreaks if cells are first grown in BHI or LEB prior to the ELISA. Alternatively, in an another assay format, MAb EM-7G1 was found to be suitable for enumeration of the three predominant L. monocytogenes serotypes (serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) from food samples by the membrane overlay microcolony immunoblotting method in conjunction with colony growth on Oxford and lithium chloride phenylethanol moxalactam (LPM) agar plates (data not shown) (23).

Patterns of 66-kDa epitope expression in serotypes.

Our results are consistent with three distinct patterns of expression for the species-specific cell surface epitope associated with the 66-kDa antigen in L. monocytogenes serotypes that can be detected by the MAb EM-7G1 probe. The first possibility is that there is a permanent shutdown of epitope expression, as suggested by the complete absence of synthesis of the target epitope in the 66-kDa protein recognized by MAb EM-7G1 for three serotypes (serotypes 3b, 4a, and 4c) which were not detected by MAb EM-7G1 in ELISA irrespective of the enrichment medium used for growth. Additional tests in which SDS-PAGE was used revealed that a 66-kDa protein band was produced by each of the three nondetectable serotypes (serotypes 3b, 4a, and 4c). However, each band apparently lacked the specific epitope recognized by MAb EM-7G1 since the bands yielded negative reactions in Western blots (data not shown).

The second possibility is that there is a temporary shutdown of 66-kDa-antigen-associated epitope synthesis for all serotypes of L. monocytogenes, depending on the growth medium used. This possibility was illustrated by the strong positive ELISA reactivities obtained with cells from BHI or LEB enrichments and the complete absence of ELISA reactivities with cells from UVM1 or FRB enrichments. Studies are under way to determine if the loss of MAb EM-7G1 reactivity results from a lack of synthesis of the 66-kDa antigen or the absence of its associated species-specific epitope for different serotypes of L. monocytogenes in UVM1 or FRB enrichments as determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The limiting factors in UVM1 or FRB that may be responsible for the loss of L. monocytogenes cell recognition by MAb EM-7G1 in ELISA tests are unknown. Perhaps because of the lack of availability of certain key essential amino acids in UVM1 or FRB, the synthesis of a cell surface epitope recognized by EM-7G1 may be decreased or absent. Also, the presence of some inhibitory substances in UVM1 or FRB broth may contribute to a delay in expression of species-specific cell surface epitopes recognized by MAb EM-7G1. The inhibitory components in UVM1 and FRB that result in a lack of expression of the 66-kDa cell surface epitope have not been determined yet. The loss of ELISA reactivity with Listeria cells grown in UVM1 or FRB may be caused by blocking of cell surface epitopes recognized by MAb EM-7G1 with additional protective layers of other, interfering cell surface proteins. The epitope may be partially buried in some L. monocytogenes serotypes grown under these conditions. Direct inhibition of MAb EM-7G1 in ELISA by a residue from UVM1 or FRB can be ruled out as these broth media were removed by centrifugation before the bacterial suspensions were diluted in carbonate coating buffer for the ELISA. The slightly lower Listeria cell numbers (3 × 108 to 6 × 108 CFU/ml) observed in UVM1 or FRB enrichments compared to the numbers in BHI, LEB, or LRB enrichments (2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU/ml) should have caused only partial reductions in the MAb EM-7G1 ELISA reactivities.

The third possibility is that there is variable synthesis of the target epitope in the 66-kDa antigen of the different L. monocytogenes strains, which results in an unequal distribution of the target epitope in the serotypes. The extensive variability in the ELISA reactivities observed with BHI or LEB enrichments suggests that the epitope recognized by MAb EM-7G1 may be produced less or more densely on the cell surface depending on the serotype of L. monocytogenes. Our ELISA results for cells from BHI or LEB enrichments show that the 66-kDa species-specific antigen recognized by MAb EM-7G1 was produced most prominently by L. monocytogenes serotype 7 and least prominently by L. monocytogenes serogroup 4. This information concerning the phenotypic variations in cell surface antigenic expression of L. monocytogenes detected by MAb EM-7G1 should permit us to develop improved immunogen preparations and MAb screening strategies.

It is possible to produce new immunogens with a mixture of all serotypes of L. monocytogenes grown in LEB, LRB, UVM1, or FRB that may activate spleen cells to produce antibodies that recognize epitopes common to all L. monocytogenes serotypes. Predominant protein fractions common to all L. monocytogenes serotypes expressed in different broth culture media can be isolated by electroelution from SDS-PAGE gels for use as immunogens and as ELISA screening antigens. L. monocytogenes serotypes that exhibit the strongest reactivities to MAb EM-7G1 from BHI, LEB, or LRB enrichments should be useful for isolation of a 66-kDa species-specific antigen. These approaches may lead to the development of MAbs that recognize other species-specific or serotype-specific epitopes of L. monocytogenes that may be produced irrespective of the enrichment broth medium used for cell growth.

Like the unstable expression and uneven distribution of the 66-kDa-antigen-associated cell surface epitope recognized by MAb EM-7G1 depending on the growth medium, there are several other examples of environmental cues that regulate expression of L. monocytogenes virulence genes (2, 20, 28). The presence of cellobiose in the culture medium has been shown to repress expression of L. monocytogenes virulence genes hly and plcA. The levels of listeriolysin O and ActA proteins were greatly reduced in the presence of cellobiose (26, 28). Expression of the 29-kDa extracellular flagellar antigens has been shown to be affected by the growth conditions, such as temperature, pH, salt, and preservatives in food samples (27).

Our studies show that MAb probes developed for any pathogen need to be fully characterized to determine the phenotypic variability in protein or epitope expression in different growth media and with both live and heat-killed cells. This study identified the limitations of the probe MAb EM-7G1 when it is used to detect L. monocytogenes serotypes and led to an understanding of assay conditions that should not be used with this MAb probe. Some other MAbs that recognize cell surface epitopes of Listeria spp. are heat stable (7, 12, 14), while some are not (14, 30). Only weak or partial reactivities with MAb EM-7G1 in the ELISA were observed when Listeria cells were heated at 80 or 100°C for 20 min irrespective of the strain or serotype or the growth medium used for enrichment of cells. Although MAb EM-7G1 was originally developed (3) by using heat-killed L. monocytogenes as an immunogen, data presented in this study show that MAb EM-7G1 is more suitable for detection of live cells of this pathogen and should not be used in conjunction with the heat killing step that is routinely recommended in commercial immunoassay protocols.

Like the MAb EM-7G1 that detected a maximum of 10 of the 13 serotypes of L. monocytogenes under specific conditions, an affinity-purified PAb probe raised against the 90-kDa ActA species-specific antigen detected only 11 of the 13 serotypes and did not detect serotypes 3a and 4ab (25). Due to a lack of uniform distribution of the species-specific 66-kDa- or 90-kDa-antigen-associated epitopes in different serotypes of L. monocytogenes, as illustrated by our examples, a combination of two or more antibody probes may be required for detection of all serotypes of L. monocytogenes in food or clinical samples.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance of Leonard Dunn in preparation of mouse ascites is gratefully acknowledged.

This research was supported in part by grants from the USDA-Food Safety Consortium.

Footnotes

Published with the approval of the director of the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station as publication no. 98002.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlas R M. P. 198, 564, and 762. In: Parks C L, editor. Handbook of microbiological media. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhunia A K. Antibodies to Listeria monocytogenes. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1997;23:77–107. doi: 10.3109/10408419709115131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhunia A K, Johnson M G. Monoclonal antibody specific for Listeria monocytogenes associated with a 66-kilodalton cell surface antigen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1924–1929. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1924-1929.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhunia A K, Ball P H, Fuad A T, Kurz B W, Emerson J W, Johnson M G. Development and characterization of a monoclonal antibody specific for Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3176–3184. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3176-3184.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bubert A, Schubert P, Kohler S, Frank R, Goebel W. Synthetic peptides derived from Listeria monocytogenes p60 protein as antigens for the generation of polyclonal antibodies specific for secreted cell-free L. monocytogenes p60 proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3120–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3120-3127.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch S V, Donnelly C W. Development of a repair-enrichment broth for resuscitation of heat-injured Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:14–20. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.14-20.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butman B T, Plank M C, Durham R J, Mattingly J A. Monoclonal antibodies which identify a genus-specific Listeria antigen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1564–1569. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.6.1564-1569.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datta A R, Kothary M H. Effects of glucose, growth temperature, and pH on listeriolysin O production in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3495–3497. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3495-3497.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly C W, Baigent G J. Method for flow cytometric detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:689–695. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.4.689-695.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber J M, Spiers J I. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the flagellar antigens of Listeria species and their potential in EIA-based methods. J Food Prot. 1987;50:479–484. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-50.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavalchin J, Tortorello J L, Malek R, Landers M, Batt C A. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies that react preferentially with Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol. 1991;8:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hitchins A D. FDA bacteriological analytical manual. 8th ed. Gaithersburg, Md: AOAC International; 1995. Listeria monocytogenes; pp. 10.01–10.13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kathariou S, Mizumoto C, Allen R D, Fok A K, Benedict A A. Monoclonal antibodies with a high degree of specificity for Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3548–3552. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3548-3552.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn M, Goebel W. Identification of an extracellular protein of Listeria monocytogenes possibly involved in intracellular uptake by mammalian cells. Infect Immun. 1989;57:355–358. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.55-61.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loisearu O, Cottin J, Robert R, Tronchin G, Mahaza C, Senet J M. Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for the genus Listeria. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;11:219–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovett J. Isolation and identification of Listeria monocytogenes in dairy foods. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1988;71:658–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattingly J A, Butman B T, Plank M C, Durham R J. A rapid monoclonal antibody-based ELISA for the detection of Listeria in food products. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1988;71:669–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClain D, Lee W H. Development of USDA-FSIS method for isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from raw meat and poultry. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1988;71:660–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mekalanos J J. Environmental signals controlling expression of virulence determinants in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.1-7.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nannapaneni R, Story R, Bhunia A K, Johnson M G. IAMFES 83rd Annual Meeting 1996. Des Moines, Iowa: International Association of Milk, Food and Environmental Sanitarians, Inc.; 1996. Differences in ELISA reactions of monoclonal antibodies EM-6E11 (genus-specific) and EM-7G1 (species-specific) against live and heat killed cells of Listeria and Listeria monocytogenes, abstr. no. 36; pp. 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nannapaneni R, Story R, Bhunia A K, Johnson M G. 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Phenotypic variability in the expression of 66 kDa species-specific antigen of Listeria monocytogenes recognized by monoclonal antibody EM-7G1, abstr. no. P-12; p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nannapaneni R, Story R, Bhunia A K, Johnson M G. 98th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1998. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Immunoblot reactivity patterns of species-specific MAb EM-7G1 against serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes grown on four selective plating media, abstr. no. 13289. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nato F, Reich K, Lhopital S, Rouyre S, Geoffroy C, Mazie J C, Cossart P. Production and characterization of neutralizing and nonneutralizing monoclonal antibodies against listeriolysin O. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4641–4644. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4641-4646.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niebuhr K, Chakraborty T, Rohde M, Gazlig T, Jansen B, Kollner P, Wehland J. Localization of the ActA polypeptide of Listeria monocytogenes in infected tissue culture cell lines: ActA is not associated with actin “comets.”. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2793–2802. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2793-2802.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park S F, Kroll R G. Expression of listeriolysin and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C is repressed by the plant-derived molecule cellobiose in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peel M N, Donachie W, Shaw A. Temperature-dependent expression of flagella of Listeria monocytogenes: studies by electron microscopy, SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2171–2178. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-8-2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renzoni A, Klarsfeld A, Dramsi S, Cossart P. Evidence that PrfA, the pleiotropic activator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes, can be present but inactive. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1515–1518. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1515-1518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siragusa G R, Johnson M G. Monoclonal antibody specific for Listeria monocytogenes, Listeria innocua, and Listeria welshimeri. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1897–1904. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1897-1904.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torensma R, Visser M J C, Aarsman C J M, Poppelier M J J G, Fluit A C, Verhoef J. Monoclonal antibodies that react with live Listeria spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2713–2716. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2713-2716.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]