Abstract

Genetic lesions of IKZF1 are frequent events and well-established markers of adverse risk in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. However, their function in the pathophysiology and impact on patient outcome in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains elusive. In a multicenter cohort of 1606 newly diagnosed and intensively treated adult AML patients, we found IKZF1 alterations in 45 cases with a mutational hotspot at N159S. AML with mutated IKZF1 was associated with alterations in RUNX1, GATA2, KRAS, KIT, SF3B1, and ETV6, while alterations of NPM1, TET2, FLT3-ITD, and normal karyotypes were less frequent. The clinical phenotype of IKZF1-mutated AML was dominated by anemia and thrombocytopenia. In both univariable and multivariable analyses adjusting for age, de novo and secondary AML, and ELN2022 risk categories, we found mutated IKZF1 to be an independent marker of adverse risk regarding complete remission rate, event-free, relapse-free, and overall survival. The deleterious effects of mutated IKZF1 also prevailed in patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (n = 519) in both univariable and multivariable models. These dismal outcomes are only partially explained by the hotspot mutation N159S. Our findings suggest a role for IKZF1 mutation status in AML risk modeling.

Subject terms: Acute myeloid leukaemia, Risk factors

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is driven and maintained by a heterogenous set of genetic lesions that affect clinical phenotypes and patient outcomes. The recently revised European Leukemia Net recommendations [1] broaden the spectrum of molecular markers relevant for risk stratification and ultimately treatment allocation. The identification of novel recurrent molecular alterations associated with patient outcome may allow for a more personalized therapeutic approach where treatment concepts are tailored to patient genetics and baseline characteristics [2].

The Ikaros zinc finger (IKZF) family comprises a set of zinc-finger proteins including five members: IKAROS (IKZF1), HELIOS (IKZF2), AIOLOS (IKZF3), EOS (IKZF4), and PEGASUS (IKZF5) [3]. The IKZF1 gene is located on chromosome 7 at 7p12.2 [4] and is composed of 8 exons coding for 519 amino acids [5, 6]. These encode four N-terminal zinc finger domains that are essential for DNA-binding and two C-terminal zinc finger domains that are required for homo- and heterodimerization with other Ikaros family member proteins [5, 6]. Alternative splicing and intragenic deletion can lead to at least 16 different isoforms that have been described in the regulation of fetal hematopoiesis as well as lymphatic cell development and maturation [7–9]. For DNA-binding, at least three N-terminal zinc fingers are required and only a few isoforms (IKZF1-3) satisfy this criterion [4]. Functionally, IKZF1 regulates transcription via chromatin remodeling and epigenetic modification and affects signaling pathways that are crucial for lymphoid differentiation, such as PI3K/AKT, IL-7 signaling as well as integrin-dependent cell survival [10, 11]. Apart from its well-defined role in lymphoid development [12, 13], IKZF1 also plays a role in erythroid and myeloid differentiation via transcriptional regulation of GATA1 and RUNX1 as well as lineage determination and cell survival [14–21].

Genetic lesions of IKZF1 are recurrent events in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) conferring poor prognosis [12, 13]. In pediatric Ph-negative B-ALL, deletions of IKZF1 are reported in ~15% of cases while this frequency rises to 30% in high risk pediatric populations [22–24]. In adult B-ALL, the frequency of IKZF1 deletions reach 30–50% [23, 25, 26], while the highest prevalence of up to 80% is found in Ph+ ALL [27–29]. Numerous studies have reported deletions of IKZF1 to be an independent marker of adverse risk in ALL adjusting for age and cytogenetic ALL subtype, resulting in higher risk of relapse and substantially shortened survival [22, 30–35].

While its frequency and impact on patient outcome are well established in ALL, the clinical significance of IKZF1 alterations is less clear in AML. Previous studies have reported the frequency of altered IKZF1 in AML to range between 1.2% in a pediatric cohort of 258 patients [36] and 2.6% to 4.8% in three adult cohorts including 193, 475, and 522 patients, respectively [37–39]. Given the overlapping functions of IKZF1 in the regulation of both lymphatic and myeloid differentiation, an investigation into the clinical implications of altered IKZF1 in AML in a large scale study seems warranted.

Methods

Data set and definitions

We retrospectively investigated a cohort of 1606 newly diagnosed and intensively treated AML patients from previously reported multicenter trials (AML96 [40] [NCT00180115], AML2003 [41] [NCT00180102], AML60 + [42] [NCT 00180167], and SORAML [43] [NCT00893373]). Patients were treated and registered under the auspices of the German Study Alliance Leukemia (SAL [NCT03188874]). Eligibility was determined based on diagnosis of AML with curative treatment intent, age ≥18 years, and available biomaterial at initial diagnosis. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Technical University Dresden (EK 98032010). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before analysis in accordance with the revised Declaration of Helsinki [44]. When no prior malignancy and no prior treatment with chemo- and/or radiotherapy was documented, AML was defined as de novo. When prior myeloid neoplasms were reported, AML was defined as secondary (sAML). Finally, when previous exposure to chemo- and/or radiotherapy was reported, AML was defined as therapy-associated (tAML). Endpoints encompassing achievement of complete remission (CR) as well as event-free (EFS), relapse-free (RFS), and overall survival (OS) were defined according to ELN2022 criteria [1]. Patients treated in previous clinical trials were retrospectively assigned to ELN2022 risk groups [1].

Molecular analysis

Screening for genetic alterations was performed on pre-treatment peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirates using the TruSight Myeloid Sequencing Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) covering 54 genes (Table S1) that are associated with myeloid neoplasms including full coding exons for IKZF1 according to the manufacturer’s recommendations as previously reported [45, 46]. DNA was extracted using the DNA Blood mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and quantified with the NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Pooled samples were sequenced paired-end (150 bp PE) on a NextSeq NGS-instrument (Illumina). Sequence data alignment of demultiplexed FastQ files, variant calling, and filtering was performed with the Sequence Pilot software package (JSI medical systems GmbH, Ettenheim, Germany) with default settings and a 5% variant allele frequency (VAF) mutation calling cut-off. Human genome build HG19 was used as reference genome for mapping algorithms. Dichotomization of dominant and subclonal (or secondary) mutations was performed by comparing VAFs of detected mutations with VAFs of co-mutated driver variants. For resolution of putative subclonal mutations a minimum difference of 10% VAF was applied. For cytogenetic analysis, standard techniques for chromosome banding and fluorescence-in-situ-hybridization (FISH) were used. Patients with mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) were explicitly not enrolled within the above-mentioned trials. Multicolor flow cytometry (MFC) reports (which were available from initial diagnosis for 32 IKZF1-mutated patients) confirmed the myeloid phenotype (Table S2). An extended MFC-analysis on stored viable cryopreserved material using several additional B- and T-cell markers confirmed a myeloid phenotype in all patients with sufficient material available (n = 17; Table S2).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using a significance level α of 0.05. All tests were carried out as two-sided tests. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If the assumption of normality was met, continuous variables between two groups were analyzed using the two-sided unpaired t-test. If the assumption of normality was violated, continuous variables between two groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Univariate analysis was carried out using logistic regression to obtain odds ratios (OR). Time-to-event analysis was performed using Cox-proportional hazard models to obtain hazard ratios (HR). Additionally, the Kaplan–Meier-method and the log-rank-test were used. For survival times, OR and HR, 95%-confidence-intervals (95%-CI) are reported. Median follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA BE 17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Mutations of IKZF1 are recurrent genetic lesions in AML with a distinct co-mutational pattern

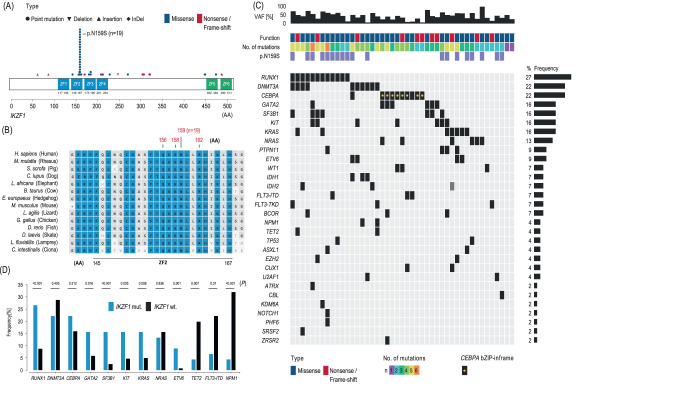

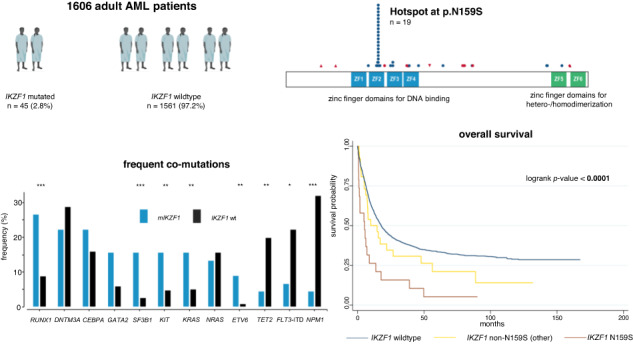

In our cohort of 1606 AML patients, we found IKZF1 to be altered in 45 cases (2.8%). Alterations were almost entirely heterozygous (n = 44, 97.8%). Single nucleotide variants (SNV) were the predominant mode of alteration (n = 39, 86.7%) while insertions (n = 4, 8.9%) were rare. Indels or deletions were only found in one instance each. Only four alterations lead to a frameshift (8.9%), all of which were predicted to resulted in premature truncation. Alterations of IKZF1 represented more often missense (n = 34, 75.6%) rather than nonsense (n = 11, 24.4%) mutations (Fig. 1A). The most commonly affected exons were exon 5 (n = 28, 62.2%), and exon 8 (n = 9, 20.0%), while alterations in exon 4 (n = 2, 4.4%), exon 6 (n = 4, 8.9%), as well as exon 7 (n = 2, 4.4%) were rare and no alterations were found in exons 1–3. IKZF1 harbors four N-terminal zinc finger domains which enable DNA binding and two C-terminal zinc finger domains for homo- and heterodimerization with other Ikaros proteins [5, 6]. The plurality of alterations were found in the second N-terminal zinc finger domain resulting in a change from adenine to guanine at base pair 476 with a consecutive switch from asparagine to serin at protein position 159 (p.N159S, n = 19, 42.2%, Fig. 1A). The N159 locus within the second zinc finger domain is highly conserved as cross-species comparisons unveil (Fig. 1B). Other alterations in that domain were rare (n = 4, 8.9%, Fig. 1A). The third and fourth N-terminal zinc finger domain were affected in three instances each (n = 3, 6.7%, respectively) while the second C-terminal zinc finger domain was only altered in one patient (n = 1, 2.2%, Fig. 1A). No patient in our cohort harbored alterations within both the first N-terminal and first C-terminal zinc finger domains (Fig. 1A). The 15 (33.3%) remaining patients showed alterations outside the zinc finger domains (Fig. 1A). Median VAF was 44.0% (Fig. 1C). Only three patients harbored mutated IKZF1 as subclonal (or secondary) mutations, while the majority (n = 42, 93.3%) of mutations were detected in dominant clonal constellations (Fig. 1C). The median number of co-occurring mutations was four (Fig. 1C). IKZF1-mutated AML patients showed significantly increased rates of alterations in RUNX1 (26.6% vs. 8.7%, p < 0.001), GATA2 (15.6% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.016), KRAS (15.6% vs. 5.0%, p = 0.008), KIT (15.6% vs. 4.6%, p = 0.005), SF3B1 (15.6% vs. 2.5%, p < 0.001), and ETV6 (8.9% vs. 0.7%, p = 0.001). In contrast, co-occurring mutations of NPM1 (4.4% vs. 32.0%, p < 0.001), FLT3-ITD (6.6% vs. 22.2%, p = 0.010), and TET2 (4.4% vs. 19.8%, p = 0.007) were significantly less prevalent (Fig. 1C, D). Patients with mutated IKZF1 less frequently had normal karyotypes (31.1% vs. 52.3%, p = 0.003) and were more frequently categorized within the ELN2022 adverse risk group (57.8% vs. 36.3%, p = 0.004). Table S3 provides a detailed numerical overview of co-occurring mutations in IKZF1-mutated AML.

Fig. 1. Localizations of deduced amino acid changes and co-mutational profile of IKZF1 alterations in acute myeloid leukemia.

IKZF1 was mutated in 45/1606 AML patients. Schematic representation of the IKZF1 protein (A). IKZF1 has four N-terminal zinc finger (ZF) domains (blue) and two C-terminal ZF domains (green). The x-axis represents amino acid positions with specific annotations for amino acids forming the ZF domains. The hotspot mutation p.N159S was present in 42.2% of cases (n = 19). This domain and locus are highly conserved across species (B). Median variant allele frequency (VAF) for IKZF1 was 44% (C). Alterations were predominantly missense rather than truncating mutations (C). AML patients bearing mutated IKZF1 had a median of four overall mutations (C). Compared to wildtype patients, patients with altered IKZF1 harbored significantly higher rates of co-occurring alterations in RUNX1, GATA2, KRAS, KIT, SF3B1, and ETV6 while co-occurrence of NPM1, FLT3-ITD, and TET2 were rare (D). For detailed information on frequency and statistical significance of associated co-mutations, please see Table S2.

IKZF1 mutations impact clinical phenotypes at initial diagnosis

Regarding clinical parameters, we found patients with mutated IKZF1 to less frequently present with de novo AML (71.1% vs. 83.7%, p = 0.038), while there was no significant difference with regard to sAML or tAML. Patients harboring mutated IKZF1 had significantly lower median Hb (5.3 mmol/l vs. 5.9 mmol/l, p = 0.036) and platelet count (35*109/l vs. 51*109/l, p = 0.029) at initial diagnosis while white blood cell count, peripheral and bone marrow blast count did not differ. There was no significant difference in age, sex or presence of extramedullary disease manifestations. Table 1 highlights baseline characteristics with respect to IKZF1 mutation status.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics with respect to IKZF1 mutation status.

| Parameter | IKZF1 mutated | IKZF1 wildtype | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | 45/1606 (2.8) | 1561/1606 (97.2) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 52 (43–64) | 56 (45–66) | 0.501 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.762 | ||

| Female | 20 (44.4) | 748 (47.9) | |

| Male | 25 (55.6) | 813 (52.1) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | |||

| de novo | 32 (71.1) | 1307 (83.7) | 0.038 |

| sAML | 9 (20.0) | 186 (11.9) | 0.107 |

| tAML | 2 (4.4) | 52 (3.3) | 0.662 |

| Missing | 2 (4.4) | 61 (3.9) | |

| Extramedullary disease, n (%) | 10 (22.2) | 204 (13.1) | 0.116 |

| missing | 3 (6.7) | 137 (8.8) | |

| ELN-Risk 2022, n (%) | |||

| Favorable | 10 (22.2) | 566 (36.3) | 0.079 |

| Intermediate | 8 (17.8) | 411 (26.3) | 0.297 |

| Adverse | 26 (57.8) | 567 (36.3) | 0.004 |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 17 (1.1) | |

| Complex karyotype, n (%) | 0.479 | ||

| No | 36 (80.0) | 1283 (82.2) | |

| Yes | 7 (15.6) | 181 (11.6) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.4) | 97 (6.2) | |

| Normal karyotype, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| No | 29 (64.5) | 644 (41.3) | |

| Yes | 14 (31.1) | 819 (52.4) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.4) | 98 (6.3) | |

| Allogeneic stem cell transplantation | |||

| In first CR | 6 (13.3) | 238 (15.2) | 0.836 |

| As salvage therapy | 10 (22.2) | 213 (13.6) | 0.123 |

| Other | 2 (4.4) | 50 (3.2) | 0.655 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | |

| Laboratory, median (IQR) | |||

| WBC (109/l) | 17.8 (5.0–43.0) | 19.1 (4.4–53.7) | 0.590 |

| HB (mmol/l) | 5.3 (4.7–6.7) | 5.9 (5.1–7.0) | 0.036 |

| PLT (109/l) | 35 (25–80) | 51 (28–95) | 0.029 |

| LDH (U/l) | 523.2 (287.0–751.0) | 443.7 (281.0–778.0) | 0.694 |

| PBB (%) | 45.5 (16.5–81.0) | 40.0 (12.0–73.0) | 0.150 |

| BMB (%) | 65.0 (43.0–80.5) | 63.0 (44.0–79.0) | 0.997 |

Bold typing indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

AML acute myeloid leukemia, sAML secondary AML, tAML therapy-associated AML, BMB bone marrow blasts, HB hemoglobin, IQR interquartile range, n/N number, PBB peripheral blood blasts, PLT platelet count, WBC white blood cell count. Bold typing indicates statistical significance.

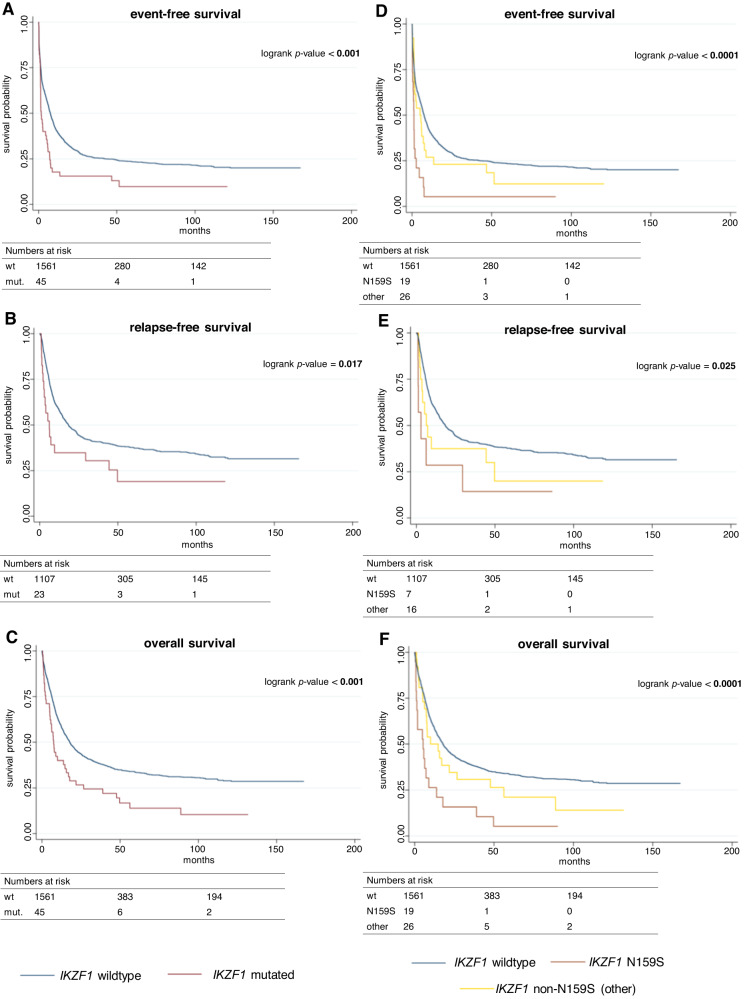

Mutated IKZF1 is an independent predictor of adverse outcome

All patients were treated within previously conducted trials of the SAL and received intensive induction therapy. Trial regimens are described in Table S4. Median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 93.3 months (95%-CI: 86.3–96.9). Regarding treatment response, patients harboring mutated IKZF1 had significantly lower odds to achieve complete remission after intensive induction therapy compared to IKZF1-wildtype patients (univariable OR: 0.42 [95%-CI: 0.23–1.77], p = 0.004, Table 2). Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 categories confirmed this to be an independent effect (multivariable OR: 0.45 [95%-CI: 0.22–0.91], p = 0.026, Table 3). Median EFS was significantly reduced for patients with mutated IKZF1 (1.7 months vs. 7.5 months, univariable HR: 1.69, p = 0.001, Table 2, Fig. 2A). Again, this effect was retained in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk groups (multivariable HR: 1.59 [95%-CI: 1.15–2.18], p = 0.004, Table 3). Further, patients with mutated IKZF1 also had significantly reduced median RFS compared to wildtype patients (6.1 months vs. 18.4 months, univariable HR: 1.75, p = 0.019, Table 2, Fig. 2B). Again, multivariable analysis revealed a persistent effect after adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk (multivariable HR: 1.87 [95%-CI: 1.17–3.00], p = 0.009, Table 3). Lastly, we also found significantly reduced median OS for patients with IKZF1-mutated AML (7.5 months vs. 17.8 months, univariable HR: 1.74, p = 0.001, Table 2, Fig. 2C). Again, this effect prevailed in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk groups (multivariable HR: 1.68 [95%-CI: 1.22–2.32], p = 0.002, Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of patient outcome with respect to IKZF1 mutation status.

| Outcome | mut. IKZF1 | wt-IKZF | OR/HR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | 45/1606 (2.8) | 1561/1606 (96.7) | ||

| CR rate, n (%) | 23/45 (51.1%) | 1112/1606 (69.2) | 0.42 [0.23–0.77] | 0.004 |

| EFS | 1.7 months [1.2–5.0] | 7.5 months [6.7–8.2] | 1.69 [1.23–2.32] | 0.001 |

| RFS | 6.1 months [2.6–29.4] | 18.4 months [15.8–22.3] | 1.75 [1.10–2.80] | 0.019 |

| OS | 7.5 months [5.1–14.7] | 17.8 months [16.1–19.9] | 1.74 [1.27–2.40] | 0.001 |

Survival times are displayed in months. Square brackets show 95%-confidence intervals. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

CR complete remission, EFS event-free survival, HR hazard ratio, Mut. mutated, n/N number, OR odds ratio, OS overall survival, RFS relapse-free-survival, wt wild-type.

Table 3.

Summary of patient outcome with respect to IKZF1 mutation status in multivariable analyses.

| Complete remission | OR [95%-CI] | p |

|---|---|---|

| Mutated IKZF1 | 0.45 [0.22–0.91] | 0.026 |

| Age | 0.95 [0.94–0.95] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 favorable risk | 2.92 [1.81–4.71] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 intermediate risk | 1.49 [0.94–2.37] | 0.091 |

| ELN2022 adverse risk | 0.55 [0.36–0.85] | 0.007 |

| de novo AML | 1.93 [1.13–3.30] | 0.017 |

| sAML | 1.74 [0.95–3.19] | 0.073 |

| Event-free survival | HR [95%-CI] | p |

| mutated IKZF1 | 1.59 [1.15–2.18] | 0.004 |

| age | 1.02 [1.02–1.03] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 favorable risk | 0.53 [0.42–0.66] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 intermediate risk | 0.95 [0.76–1.19] | 0.678 |

| ELN2022 adverse risk | 1.56 [1.27–1.94] | <0.001 |

| de novo AML | 0.90 [0.69–1.18] | 0.446 |

| sAML | 0.83 [0.61–1.12] | 0.227 |

| Relapse-free survival | HR [95%-CI] | p |

| mutated IKZF1 | 1.87 [1.17–3.00] | 0.009 |

| age | 1.02 [1.02–1.03] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 favorable risk | 0.58 [0.43–0.78] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 intermediate risk | 1.00 [0.74–1.35] | 0.935 |

| ELN2022 adverse risk | 1.30 [0.96–1.75] | 0.087 |

| de novo AML | 1.07 [0.70–1.63] | 0.767 |

| sAML | 0.98 [0.61–1.57] | 0.925 |

| Overall survival | HR [95%-CI] | p |

| Mutated IKZF1 | 1.68 [1.22–2.32] | 0.002 |

| Age | 1.03 [1.03–1.04] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 favorable risk | 0.56 [0.44–0.72] | <0.001 |

| ELN2022 intermediate risk | 1.00 [0.78–1.27] | 0.981 |

| ELN2022 adverse risk | 1.50 [1.19–1.88] | 0.001 |

| de novo AML | 0.80 [0.61–1.06] | 0.123 |

| sAML | 0.79 [0.58–1.08] | 0.143 |

Square brackets show 95%-confidence intervals. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

HR hazard ratio, OR odds ratio, sAML secondary AML (sAML).

Fig. 2. Survival analysis regarding IKZF1 mutation status in acute myeloid leukemia.

Survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier estimators and the log-rank test. First, differences in survival times were analyzed comparing mutated (mut.) vs. wildtype (wt) IKZF1 (A–C). AML patients with mut. IKZF1 (red) show significantly decreased event-free (A), relapse-free (B), and overall survival (C) compared to AML patients with wt IKZF1 (blue). The hotspot mutation N159S confers decreased event-free (D), relapse-free (E), and overall survival (F) while patients harboring non-N159S IKZF1 (other) alterations find themselves in between IKZF1-N159S and wt patients with regard to survival times. Survival times in months. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Given the number of IKZF1-mutations at the N159 locus, we also investigated the role of this hotspot mutation with regard to outcome. Patients harboring IKZF1-N159S showed a lower OR to achieve CR (univariable OR: 0.24 [95%-CI: 0.09–0.60], p = 0.003) compared to non-N159S (univariable OR: 0.65 [95%-CI: 0.29–1.43], p = 0.283) and wild-type patients (univariable OR: 2.37 [95%-CI: 1.31–4.29], p = 0.004, Table S5). However, this effect did not prevail in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 categories (multivariable OR: 0.41 [95%-CI: 0.15–1.12], p = 0.083, Table S6). For patients with IKZF1-N159S we found significantly reduced EFS compared to non-159S and wildtype patients (1.2 months vs. 5.0 months vs. 7.5 months, univariable HR: 2.81, p < 0.001, Fig. 2D Table S5), which remained significant in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk (multivariable HR: 1.69 p = 0.029, Table S6). RFS for patients with IKZF1-N159S was also significantly reduced compared to non-N159S and wildtype patients (2.9 months vs. 6.3 months vs. 18.4 months, univariable HR: 2.50, p = 0.025, Fig. 2E, Table S5), however, this effect was lost in multivariable analysis (multivariable HR: 1.59 p = 0.265, Fig. 2F, Table S6). Lastly, we also found significantly reduced OS for N159S-patients compared to non-N159S- and wildtype-patients (5.3 months vs. 9.9 months vs. 17.8 months, univariable HR: 2.66, p < 0.001, Table S5), which remained significant in multivariable analysis adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk (multivariable HR: 1.73 p = 0.023, Table S6). Further, we also investigated the effects of differentially affected zinc finger domains as well as haploinsufficiency of IKZF1 on outcome, however, individual sample sizes were too small to attribute any meaningful impact to alterations other than N159S, which lies within the second zinc finger domain (Fig. S1).

Within the cohort, 519 patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), 3.5% of them (n = 18) harbored alterations in IKZF1. The rates between patients with altered and wildtype IKZF1 that underwent allo-HSCT either in first CR or as a salvage therapy did not differ significantly (Table 1). Still, patients with IKZF1 alterations showed significantly decreased EFS (univariable HR: 1.81, p = 0.023, Fig. S2A, Table S7), RFS (univariable HR: 1.92, p = 0.034, Fig. S2B, Table S7), and OS (univariable HR: 1.99, p = 0.012, Fig. S2C, Table S7). All these effects remained significant in multivariable analyses adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk (Table S8). The deleterious effect of IKZF1 alterations in patients undergoing alloHSCT was then further narrowed down on the hotspot alteration N159S. Patients bearing IKZF1-N159S showed substantially poorer outcomes (EFS: univariable HR: 4.27, p < 0.001, Fig. S2D; RFS: univariable HR: 3.90, p = 0.003, Fig. S2E; OS: univariable HR: 3.22, p = 0.002, Fig. S2F; Table S9) compared to patients with other alterations in IKZF1 or wildtype. Again, these effects prevailed in multivariable analyses adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 risk (Table S10).

Discussion

The role and implications of IKZF1 mutations and deletions are well studied in ALL [12, 13], while their prevalence and impact in AML remain elusive. In ALL, IKZF1 alterations are found in 10–80%, depending on ALL subtype and patient age [22–29], however, studies in AML are scarce and report much lower frequencies ranging from 1.3–2.6% [36, 37], which is comparable to the 2.8% of patients harboring IKZF1 alterations in our cohort. In ALL, the most common mode of alteration is heterozygous deletion either of the whole gene or of specific exons with subsequent loss-of-function [22, 28, 33, 47], while impact on outcome is dependent on the affected exon [48]. In chronic myeloid leukemia, deletions and mutations of IKZF1 have been described upon progression to predominantly lymphoid blast crisis [49]. Among 258 pediatric AML cases, de Rooij et al. [36] found eleven patients with IKZF1 deletions of whom eight had a complete loss of chromosome 7 and three had a focal deletion resulting in loss-of-function of IKZF1 while only three patients displayed a SNV. In a cohort of 193 adult AML patients, Zhang et al. [37] reported five patients with IKZF1 mutations and identified five frameshift or nonsense mutations as well as two missense mutations. In a subsequent study, Zhang et al. [38] investigated 522 newly diagnosed AML patients, 20 of whom harboring IKZF1 mutations. They found a significant co-occurrence of mutations in SF3B1, CSF3R, and CEBPA, while IKZF1 mutations were mutually exclusive with mutated NPM1 [38]. While the authors describe a significantly reduced CR rate for patients with IKZF1 mutations, they did not find a difference in RFS or OS in their overall cohort, however, for patients with high mutational burden of IKZF1 (VAF > 0.2), OS was significantly reduced [38]. Wang et al. [39] found 23 (4.8%) of 475 AML patients to bear mutated IKZF1. In RNA sequencing, they delineated three clusters of IKFZ-mutated patients: N159S (40%), co-occurring CEBPA mutations (43%), and others (17%) [39]. They report higher expression of HOXA/B as well as native B-cell fractions with IKZF1 N159S suggesting a deregulation of MYC and CPNE7 targets in pathogenesis [39].

In our large cohort of 1606 adult AML patients, we found heterozygous SNVs to be the most common mode of alteration while we observed only four frame-shift mutations and only one small deletion of IKZF1. In accordance with previous results [37, 39], we also identified a mutational hotspot in the second N-terminal zinc finger domain at p.N159S, which was present in 19 cases (42.2%). Furthermore, in our cohort alterations were restricted to exons 5–8 while no alterations were detected in exons 1–3. Interestingly, in the majority of cases, we found IKZF1 to be altered in dominant clonal constellations suggesting these mutations to be earlier events in leukemogenesis. With regard to the co-mutational landscape, we found alterations of IKZF1 to be associated with alterations in RUNX1, GATA2, KRAS, KIT, SF3B1, and ETV6 while concomitant alterations in NPM1, TET2 as well as FLT3-ITD and normal karyotypes were less frequent. The high co-occurrence of alterations in RUNX1 and GATA2 hints at a synergistic pathway in leukemogenesis, arguably converging on NOTCH signaling, with possible dysregulation of lineage determination and perturbance of erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis as well as survival regulation in myeloid progenitors [14–21]. Co-occurring mutations in SF3B1 have also been described by Zhang et al. [37, 38], however, they also reported a significantly increased rate of concomitant biallelic alterations of CEBPA. Although we also observed a substantial number of CEBPA-mutant patients (n = 10), this association did not reach statistical significance. Interestingly, most patients with IKZF1 mutations in the CEBPA-cohort had mutations outside exon 5. IKZF1-mutated AML patients less frequently had de novo AML, however, the rates of sAML or tAML were not significantly increased in our cohort. Jäger et al. [50] found deletions of IKZF1 to occur in ~20% of AML cases that arose secondary to myeloproliferative neoplasms suggesting a differential role of deletions and mutations in myeloid leukemogenesis.

With regard to clinical phenotypes, we found patients with IKZF1-mutated AML to show a significantly lower Hb and platelet count upon initial diagnosis, possibly corresponding to the suggested dysregulation of erythro- and megakaryopoiesis. In our cohort, patients with IKZF1-mutated AML were more frequently categorized within the ELN2022 adverse risk group. While deletions of IKZF1 are a well-established marker of adverse outcomes in ALL portraying substantially higher relapse rates and shortened survival [22, 30–35], evidence on the impact of IKZF1 alterations in AML is sparse. In pediatric AML, de Rooij et al. [36] found no differences between focal deletions of IKZF1 or monosomy 7 compared to non-affected patients. In the studies by Zhang et al. [37, 38], the adverse effect of IKZF1 was limited to high VAF and only demonstrated for overall survival. In a comprehensive study of multiple genetic lesions, Milosevic et al. [51] did not find any significant effects of del(7p) or deletions of IKZF1 on overall survival in 203 AML cases.

In our cohort, we found IKZF1 mutations to be an independent marker of adverse outcomes in AML. Univariable analyses revealed patients with IKZF1-mutated AML to have significantly lower odds of achieving CR upon intensive induction therapy in line with recent findings by Zhang et al. [38]. Furthermore, for those patients EFS, RFS, and OS were substantially shorter compared to IKZF1-wildtype patients. These dismal effects of IKZF1-mutated AML on CR rate, EFS, RFS, and OS persisted in multivariable analyses adjusting for age, de novo or sAML, and ELN2022 categories (which include monosomy 7 in the adverse risk group) for all outcome variables. Interestingly, for the hotspot mutation N159S, we only found significant effects on EFS and OS in multivariable models, while the effect on CR rate and RFS was only present in univariable analysis. This hints at considerable heterogeneity within IKZF1-altered AML. Since the N-terminal zinc finger domains are critical for IKZF1’s DNA-binding function, an alteration in these domains could arguably reduce IKZF1’s ability to bind to DNA and thus impair its role as a tumor suppressor by disrupted regulation of target genes [9]. These deleterious effects of alterations in IKZF1 were also highly relevant within the context of allo-HSCT, where patients harboring the N159S variant showed substantially worse outcomes than patients with other IKZF1 alterations or IKZF1-wildtype. Even considering our large sample size, the differential effects of other IKZF1 alterations than the N159S hotspot mutation still remain elusive. The heterogeneity of the functional aspects of different IKZF1-mutants has been previously documented for several germline variants, with mutations affecting the highly conserved region in zinc finger 2 appearing to affect most physiological roles of IKZF1, including DNA-binding, transcriptional repression, adhesion, and protein localization [52]. Interestingly, among these mutations, the N159S variant further steps out in that it appears to have a dominant negative effect on the IKZF1-wt protein [53]. Thus, a differential analysis of IKZF1 alterations is warranted both in an in vitro and clinical setting in an even larger cohort to elucidate the potential effect of the IKZF1 mutation type. Our findings are, however, limited by the fact that we investigated a Caucasian adult patient sample and thus our results may not necessarily be generalizable to pediatric or non-Caucasian populations. Further, all patients in our analysis received intensive induction regimens while hypomethylating agents or targeted therapy was not applied except for a minority of patients from the SORAML study who received sorafenib in addition to intensive chemotherapy. However, sorafenib did not impact CR rate or OS in the original report [43]. This warrants further investigation into the role of IKZF1 mutations and deletions in such populations as well as external validation in comparable cohorts. Furthermore, preclinical evidence suggests a therapeutic implication of immunomodulatory imide drugs (IMiDs) and targeted therapy in the context of altered IKZF1 in a variety of hematological neoplasms. For instance, lenalidomide causes selective ubiquitination and degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 conferring cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma cells [54, 55]. These effects could arguably be leveraged in MDS and AML as cytotoxic effects of lenalidomide have been demonstrated to be mediated by CRBN and IKZF1 in AML [56] as well as de-repression of both GPR68 and RCAN1 in MDS [57]. The so far limited success of lenalidomide in the general AML patient population could, therefore, arguably be attributed to a lack of molecular stratification in the context of, for example, IKZF1 mutation status. Further, IKZF1 cooperates with MLL1/MENIN and combined degradation of IKZF1 via IMiDs as well as MENIN inhibition, i.e., via ziftometinib (KO539) or VTP-50469, has been demonstrated to effectively kill leukemic cells in preclinical studies [58, 59]. This may yield a novel therapeutic approach in myeloid neoplasms based on IKZF1 mutation status. Moreover, BTX-1188, a myc inhibitor and specific degrader of GSPT1 and IKZF1/3, is currently under investigation in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial (NCT05144334) enrolling patients with advanced solid tumors, non-Hodgkin-lymphomas and AML [60], however without specified molecular stratification regarding IKZF1 mutation status.

In summary, we found IKZF1 mutations to be recurrent events in a large multicenter cohort of adult AML patients with a hotspot lesion at N159S. AML with mutated IKZF1 displayed a distinct co-mutational pattern hinting at synergistic and convergent pathways contributing to leukemogenesis and resulting in clinical phenotypes associated with cytopenia. Further, we identified mutated IKZF1 to be an independent marker of adverse outcomes in multivariable analyses demonstrating a substantially decreased CR rate and shortened EFS, RFS, and OS, which can only partially be attributed to the hotspot lesion N159S. These findings warrant the further evaluation of IKZF1 mutation status for clinical decision making as well as the development of therapeutic strategies to alleviate the dismal outcomes of IKZF1-mutated AML, for example, using combinatorial strategies including IMiDs.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out under the auspices of the Study Alliance Leukemia. We thank all involved patients, nurses, laboratory technicians and physicians for their contributions.

Author contributions

J-NE, CT, and JMM designed the study. SSt and CT performed NGS analysis. J-NE performed statistical analysis and wrote the draft. All authors contributed patient samples, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All authors revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

CT is co-owner of Agendix GmbH, a company performing molecular analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jan Moritz Middeke, Christian Thiede.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-023-02061-1.

References

- 1.Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140:1345–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Döhner H, Wei AH, Löwenberg B. Towards precision medicine for AML. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:577–90. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00509-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John LB, Ward AC. The Ikaros gene family: transcriptional regulators of hematopoiesis and immunity. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molnár A, Wu P, Largespada DA, Vortkamp A, Scherer S, Copeland NG, et al. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of lymphocyte-restricted zinc finger DNA binding proteins, highly conserved in human and mouse. J Immunol. 1996;156:585–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.156.2.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne MA. Zinc finger structure-function in Ikaros. World J Biol Chem. 2011;2:161–6. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v2.i6.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufmann C, Yoshida T, Perotti EA, Landhuis E, Wu P, Georgopoulos K. A complex network of regulatory elements in Ikaros and their activity during hemo-lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2003;22:2211–23. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgopoulos K, Moore DD, Derfler B. Ikaros, an early lymphoid-specific transcription factor and a putative mediator for T cell commitment. Science. 1992;258:808–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1439790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, Molnar A, Wu P, Winandy S, et al. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winandy S, Wu P, Georgopoulos K. A dominant mutation in the Ikaros gene leads to rapid development of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell. 1995;83:289–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koipally J, Kim J, Jones B, Jackson A, Avitahl N, Winandy S, et al. Ikaros chromatin remodeling complexes in the control of differentiation of the hemo-lymphoid system. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:79–86. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreirós-Vidal I, Carroll T, Taylor B, Terry A, Liang Z, Bruno L, et al. Genome-wide identification of Ikaros targets elucidates its contribution to mouse B-cell lineage specification and pre-B-cell differentiation. Blood. 2013;121:1769–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-450114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vairy S, Tran TH. IKZF1 alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the good, the bad and the ugly. Blood Rev. 2020;44:100677. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marke R, Leeuwen FN, van, Scheijen B. The many faces of IKZF1 in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2018;103:565–74. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.185603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malinge S, Thiollier C, Chlon TM, Doré LC, Diebold L, Bluteau O, et al. Ikaros inhibits megakaryopoiesis through functional interaction with GATA-1 and NOTCH signaling. Blood. 2013;121:2440–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-450627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida T, Ng SYM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Georgopoulos K. Early hematopoietic lineage restrictions directed by Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:382–91. doi: 10.1038/ni1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez RA, Schoetz S, DeAngelis K, O’Neill D, Bank A. Multiple hematopoietic defects and delayed globin switching in Ikaros null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:602–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022412699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao KN, Smuda C, Gregory GD, Min B, Brown MA. Ikaros limits basophil development by suppressing C/EBP-α expression. Blood. 2013;122:2572–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-494625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumortier A, Kirstetter P, Kastner P, Chan S. Ikaros regulates neutrophil differentiation. Blood. 2003;101:2219–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papathanasiou P, Perkins AC, Cobb BS, Ferrini R, Sridharan R, Hoyne GF, et al. Widespread failure of hematolymphoid differentiation caused by a recessive niche-filling allele of the Ikaros transcription factor. Immunity. 2003;19:131–44. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dijon M, Bardin F, Murati A, Batoz M, Chabannon C, Tonnelle C. The role of Ikaros in human erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2008;111:1138–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz A, Williams O, Brady HJM. The Ikaros splice isoform, Ikaros 6, immortalizes murine haematopoietic progenitor cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1240–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, Radtke I, Phillips LAA, Miller CB, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:470–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, Miller CB, Coustan-Smith E, Dalton JD, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–64. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran TH, Harris MH, Nguyen JV, Blonquist TM, Stevenson KE, Stonerock E, et al. Prognostic impact of kinase-activating fusions and IKZF1 deletions in pediatric high-risk B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2018;2:529–33. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017014704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tokunaga K, Yamaguchi S, Iwanaga E, Nanri T, Shimomura T, Suzushima H, et al. High frequency of IKZF1 genetic alterations in adult patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2013;91:201–8. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsson K, Cazier JB, MacDougall F, Stevens J, Stasevich I, Vrcelj N, et al. Microdeletions are a general feature of adult and adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia: unexpected similarities with pediatric disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6708–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Dalton J, Ma J, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iacobucci I, Storlazzi CT, Cilloni D, Lonetti A, Ottaviani E, Soverini S, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of recurrent genomic deletions on 7p12 in the IKZF1 gene in a large cohort of BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients: on behalf of Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto Acute Leukemia Working Party (GIMEMA AL WP) Blood. 2009;114:2159–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Veer A, Zaliova M, Mottadelli F, De Lorenzo P, Te Kronnie G, Harrison CJ, et al. IKZF1 status as a prognostic feature in BCR-ABL1-positive childhood ALL. Blood. 2014;123:1691–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-509794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Veer A, Waanders E, Pieters R, Willemse ME, Van Reijmersdal SV, Russell LJ, et al. Independent prognostic value of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2 expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122:2622–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-462358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, Cheok MH, Buijs-Gladdines JGCAM, Peters STCJM, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:125–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsson L, Castor A, Behrendtz M, Biloglav A, Forestier E, Paulsson K, et al. Deletions of IKZF1 and SPRED1 are associated with poor prognosis in a population-based series of pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosed between 1992 and 2011. Leukemia. 2014;28:302–10. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dörge P, Meissner B, Zimmermann M, Möricke A, Schrauder A, Bouquin JP, et al. IKZF1 deletion is an independent predictor of outcome in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated according to the ALL-BFM 2000 protocol. Haematologica. 2013;98:428–32. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.056135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribera J, Morgades M, Zamora L, Montesinos P, Gómez-Seguí I, Pratcorona M, et al. Prognostic significance of copy number alterations in adolescent and adult patients with precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia enrolled in PETHEMA protocols. Cancer. 2015;121:3809–17. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang W, Kuang P, Li H, Wang F, Wang Y. Prognostic significance of IKZF1 deletion in adult B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:215–25. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2869-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Rooij JDE, Beuling E, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Obulkasim A, Baruchel A, Trka J, et al. Recurrent deletions of IKZF1 in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100:1151–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Zhang X, Li X, Lv Y, Zhu Y, Wang J, et al. The specific distribution pattern of IKZF1 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:140. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00972-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Huang A, Liu L, Qin J, Wang C, Yang M, et al. The clinical impact of IKZF1 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2023;12:33. doi: 10.1186/s40164-023-00398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Cheng W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Sun T, Zhu Y, et al. Identification of IKZF1 genetic mutations as new molecular subtypes in acute myeloid leukaemia. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13:e1309. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Röllig C, Thiede C, Gramatzki M, Aulitzky W, Bodenstein H, Bornhäuser M, et al. A novel prognostic model in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of 909 patients entered into the prospective AML96 trial. Blood. 2010;116:971–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-267302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaich M, Parmentier S, Kramer M, Illmer T, Stölzel F, Röllig C, et al. High-dose cytarabine consolidation with or without additional amsacrine and mitoxantrone in acute myeloid leukemia: results of the prospective randomized AML2003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2094–102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Röllig C, Kramer M, Gabrecht M, Hänel M, Herbst R, Kaiser U, et al. Intermediate-dose cytarabine plus mitoxantrone versus standard-dose cytarabine plus daunorubicin for acute myeloid leukemia in elderly patients. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:973–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Röllig C, Serve H, Hüttmann A, Noppeney R, Müller-Tidow C, Krug U, et al. Addition of sorafenib versus placebo to standard therapy in patients aged 60 years or younger with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia (SORAML): a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1691–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gebhard C, Glatz D, Schwarzfischer L, Wimmer J, Stasik S, Nuetzel M, et al. Profiling of aberrant DNA methylation in acute myeloid leukemia reveals subclasses of CG-rich regions with epigenetic or genetic association. Leukemia. 2019;33:26–36. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stasik S, Schuster C, Ortlepp C, Platzbecker U, Bornhäuser M, Schetelig J, et al. An optimized targeted next-generation sequencing approach for sensitive detection of single nucleotide variants. Biomol Detect Quantif. 2018;15:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bdq.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwab CJ, Chilton L, Morrison H, Jones L, Al-Shehhi H, Erhorn A, et al. Genes commonly deleted in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: association with cytogenetics and clinical features. Haematologica. 2013;98:1081–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.085175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boer JM, van der Veer A, Rizopoulos D, Fiocco M, Sonneveld E, de Groot-Kruseman HA, et al. Prognostic value of rare IKZF1 deletion in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an international collaborative study. Leukemia. 2016;30:32–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grossmann V, Kohlmann A, Zenger M, Schindela S, Eder C, Weissmann S, et al. A deep-sequencing study of chronic myeloid leukemia patients in blast crisis (BC-CML) detects mutations in 76.9% of cases. Leukemia. 2011;25:557–60. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jäger R, Gisslinger H, Passamonti F, Rumi E, Berg T, Gisslinger B, et al. Deletions of the transcription factor Ikaros in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2010;24:1290–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milosevic JD, Puda A, Malcovati L, Berg T, Hofbauer M, Stukalov A, et al. Clinical significance of genetic aberrations in secondary acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:1010–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Churchman ML, Qian M, te Kronnie G, Zhang R, Yang W, Zhang H, et al. Germline genetic IKZF1 variation and predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:937–48.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boutboul D, Kuehn HS, Van de Wyngaert Z, Niemela JE, Callebaut I, Stoddard J, et al. Dominant-negative IKZF1 mutations cause a T, B, and myeloid cell combined immunodeficiency. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3071–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI98164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krönke J, Udeshi ND, Narla A, Grauman P, Hurst SN, McConkey M, et al. Lenalidomide causes selective degradation of IKZF1 and IKZF3 in multiple myeloma cells. Science. 2014;343:301–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1244851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu YX, Braggio E, Shi CX, Kortuem KM, Bruins LA, Schmidt JE, et al. Identification of cereblon-binding proteins and relationship with response and survival after IMiDs in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2014;124:536–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-557819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fang J, Liu X, Bolanos L, Barker B, Rigolino C, Cortelezzi A, et al. A calcium- and calpain-dependent pathway determines the response to lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Med. 2016;22:727–34. doi: 10.1038/nm.4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dou A, Fang J. Cyclosporine broadens the therapeutic potential of lenalidomide in myeloid malignancies. J Cell Immunol. 2020;2:237–44. doi: 10.33696/immunology.2.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fiskus W, Daver N, Boettcher S, Mill CP, Sasaki K, Birdwell CE, et al. Activity of menin inhibitor ziftomenib (KO-539) as monotherapy or in combinations against AML cells with MLL1 rearrangement or mutant NPM1. Leukemia. 2022;36:2729–33. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01707-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aubrey BJ, Cutler JA, Bourgeois W, Donovan KA, Gu S, Hatton C, et al. IKAROS and MENIN coordinate therapeutically actionable leukemogenic gene expression in MLL-r acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:595–613. doi: 10.1038/s43018-022-00366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chourasia AH, Majeski H, Pasis A, Erdman P, Oke A, Hecht D, et al. BTX-1188, a first-in-class dual degrader of GSPT1 and IKZF1/3, for treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and solid tumors. JCO. 2022;40:7025. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.