Abstract

A fosmid library with inserts containing approximately 40 kb of marine bacterial DNA (J. L. Stein, T. L. Marsh, K. Y. Wu, H. Shizuya, and E. F. DeLong, J. Bacteriol. 178:591–599, 1996) yielded four clones with 16S rRNA genes from the order Planctomycetales. Three of the clones belong to the Pirellula group and one clone belongs to the Planctomyces group, based on phylogenetic and signature nucleotide analyses of full-length 16S rRNA genes. Sequence analysis of the ends of the genes revealed a consistent mismatch in a widely used bacterium-specific 16S rRNA PCR amplification priming site (27F), which has also been reported in some thermophiles and spirochetes.

Environmental 16S rRNA clone libraries have been extremely valuable as a source of information about microbial diversity in natural ecosystems but suffer from the drawback that they provide little information about the physiology of unknown organisms. One method that theoretically can yield more insight into the metabolism and genetics of uncultured organisms is the construction of fosmid libraries that contain up to 40 kb of environmental DNA in each clone. These clones can be screened for the presence of 16S rRNA genes, thereby allowing the clones to be phylogenetically identified by comparison of their genes to large 16S rRNA gene databases. Additionally, the sequencing of DNA surrounding the 16S rRNA gene can yield clues about the physiology of the organisms.

Phylogenetic surveys indicate that members of the order Planctomycetales are common in aquatic ecosystems (for a review, see reference 6). Although the habit of attachment to particles, which is common within this order, suggests a potential role for these organisms in the formation and dissolution of marine microaggregates (16), information on their ecology is very limited. We were intrigued to find that genomic DNA containing Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes was relatively common (4 clones) in a fosmid library containing on the order of 100 bacterial 16S rRNA genes (estimated from the size of the clone library, typical bacterial genome sizes, and average numbers of rRNA genes per genome).

The Planctomycetales genomic DNA clones that we encountered enabled us to phylogenetically identify the source organism and also to investigate the sequences of the 5′ regions of the 16S rRNA genes. We discovered a consistent substitution in a site that is widely used for PCR primers which was present both in our clones and in Planctomycetales and thermophilic bacterial sequences also obtained by methods other than PCR.

The fosmid library was constructed from particulates in marine water collected off the Oregon coast at a depth of 200 m in October 1992. An initial screen revealed an archaeal 16S rRNA gene clone (17). To further characterize the library, a PCR screen for Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes was conducted with the universal primer 519F (12) and a primer designed to be Planctomycetales-specific (1378R; 5′-ACAAHG CTDAGGAACA), with the following reaction components: 1× buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0 at 25°C], 0.1% [final concentration] Triton X-100; Promega, Madison, Wis.), 1.5 mM MgCl2, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at 50 μM, each primer at 200 nM, 5% acetamide, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase in a 20-μl reaction volume. Reactions were at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, for 35 cycles. Pooled rows and columns from the arrayed library were used as PCR templates, with positive clones being identified at the intersections of positive rows and columns (17). Four clones, designated 5H12, 6O13, 6N14, and 7F15, were identified as potentially containing Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes.

The fosmid inserts are flanked by NotI restriction enzyme sites; therefore, digestion of the fosmids with this enzyme, followed by gel electrophoresis, reveals insert sizes. Clones 5H12, 6O13, 6N14, and 7F15 had insert sizes of 33.8, 36.0, 40.6, and 40.3 kb, respectively (data not shown).

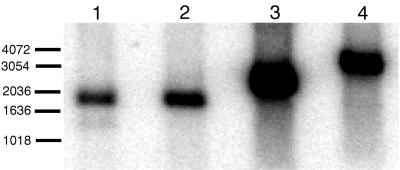

To verify that Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes were present on the fosmids, a Southern blot experiment was performed. The four fosmids were isolated with the Prep-A-Gene DNA Purification System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified fosmids were digested with the restriction endonucleases EcoRI and HindIII (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Digested DNA was separated in a 0.8% agarose gel. The fosmid DNA was then bound to a Zetaprobe (Bio-Rad) nylon membrane and probed with the 32P end-labeled oligonucleotide 53F (5′-TTGGCGGCNTGGATTAGG), which is designed to be Planctomycetales-specific, or 1406F (12), which hybridizes to universally conserved 16S rRNA sequences. The blot was washed at 37°C in 0.2× SSPE–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2 PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7]), and radioactive signals were detected with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Both probes hybridized to a single restriction fragment in each digested clone, indicating that each clone contained a nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene on a single fragment between 1.6 and 3.0 kb in size (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Southern blot of EcoRI- and HindIII-digested fosmids hybridized with 32P end-labeled Planctomycetales-specific 16S rRNA and universal rRNA oligonucleotides. Sizes (in base pairs) are indicated on the left. Lanes: 1, 5H12; 2, 6O13; 3, 6N14; 4, 7F15.

The restriction fragments containing 16S rRNA genes from fosmid clones 5H12, 6O13, and 6N14 were subcloned into the vector pCRII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). For cloning, both overhanging ends resulting from restriction digestion were filled in and each was extended with an overhanging adenosine residue by using the PCR mixture with no primers and incubation at 72°C for 2 h. Transformants containing Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes were detected with the PCR assay described above. The size range for inserts containing 16S rRNA genes was from 1.6 to 2.3 kb.

Subclones from fosmid clone 7F15 were more difficult to obtain, most likely due to inefficient ligation of the 3.0-kb fragment. Following digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, fragments from 7F15 were directly ligated into a mixture of pUC18 vectors digested with either EcoRI or HindIII. The ligated fragments were then amplified by PCR with the primers M13R (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC) and either 519F or 1378R, as described above. The resulting PCR products of 2,000 bp and 1,800 bp were then ligated into the vector pCRII. The set of clones obtained by this procedure contained overlapping 5′ and 3′ regions of the 16S rRNA gene and neighboring sequences.

All 16S rRNA genes were bidirectionally sequenced with a fluorescent dideoxy termination reaction (ABI, Foster City, Calif.), analyzed on an ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer, and assembled with Staden software (4).

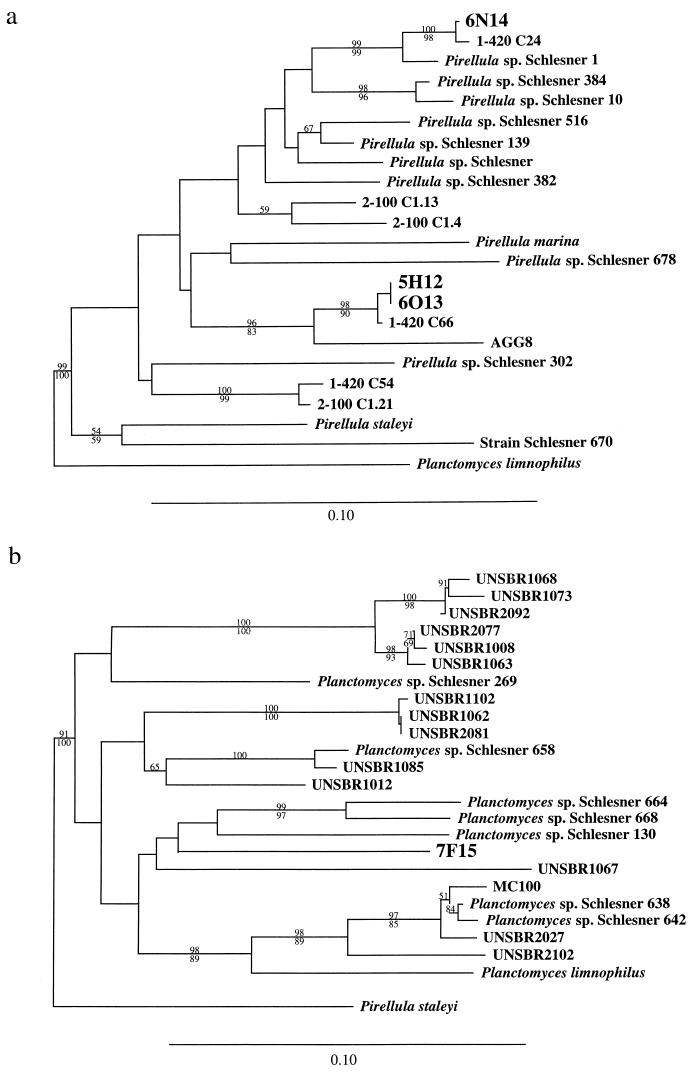

As expected, all four clones belonged to the order Planctomycetales (Fig. 2a). Three of the clones were most closely associated with cultured members of the genus Pirellula. Within this group, clones 5H12 and 6O13 were 99.7% similar to each other and closely related to environmental 16S rRNA gene clone 1-420 C66, retrieved by PCR and cloning from particulate samples collected 5.5 miles off the coast of Nice, France, at a depth of 420 m (2). The third clone, 6N14, was closely related to clone 1-420 C24, from the same library that yielded 1-420 C66. The fourth clone, 7F15, was phylogenetically related to members of the genus Planctomyces and was most closely related to Planctomyces sp. strain Schlesner 130, isolated from surface water of Kiel Fjord (18) (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

Evolutionary relationships among Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes found in cultured isolates, environmental clone libraries generated by PCR, and fosmid clones. Sequences were aligned by eye. Phylogenetic analyses included all nucleotide positions for which unambiguously determined and aligned sequence data were available for the strains and clones examined. Since sequences in public databases are sometimes shorter than the ca. 1,550 bases determined for our fosmid clones, phylogenetic analyses included fewer nucleotide positions. Phylogenetic frameworks were inferred by neighbor-joining with Kimura 2-parameter genetic distances (2:1 transition:transversion ratio) with the PHYLIP version 3.5c computer program (5a). Bootstrap proportions were calculated from 100 resampled data sets by both neighbor-joining and maximum parsimony algorithms. Bootstrap proportions are indicated by small numbers; neighbor-joining proportions are shown above, and maximum parsimony proportions are shown below. Scale bars indicate the inferred frequency of substitutions per nucleotide position. Strains labeled “Schlesner” are from reference 18. (a) Pirellula group phylogeny inferred from 226 nucleotide positions. (b) Planctomyces group phylogeny inferred from 321 positions.

Several signature nucleotides for Planctomycetales (14, 19) and, in addition, for the Planctomycetales genera Pirellula and Planctomyces (7) have been described. All of the signature nucleotides for the Planctomycetales are present in the clones described here except for the U at Escherichia coli position 983:1, which is deleted in 5H12 and 6O13, and a G:C base pair at 784:798 which is replaced by an A:U base pair in clone 7F15. Analysis of the Pirellula-like clones confirms the presence of all Pirellula signature nucleotides (Table 1). All but two of the signature nucleotides were confirmed for the Planctomyces-like clone 7F15. However, the nucleotides at positions 948 and 1233 are predicted to form a base pair across a helix, and the substitutions in the 7F15 clone maintain this base pairing relationship.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Pirellula- and Planctomyces-specific 16S rRNA signature nucleotidesa for Pirellula-like and Planctomyces-like clones

| Positionb | Nucleotides

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pirellula group | Clones 5H12, 6O13, and 6N14 | Planctomyces group | Clone 7F15 | |

| 114 | A | A | G | G |

| 115 | G | G | U | U |

| 312 | C | C | A | A |

| 313 | U | U | C | C |

| 680 | A | A | C | C |

| 710 | U | U | G | G |

| 948 | G | G | C | G |

| 1100 | U | U | G or A | A |

| 1233 | C | C | G | C |

| 1420 | U | U | G(c) | C |

| 1480 | G(a) | G | C(g) | G |

Signature nucleotides are taken from reference 7. Bases in a minority of strains are represented in lowercase letters.

Based on the E. coli numbering system.

Since the Planctomycetales as a group have several unusual sequence features of the 16S rRNA gene as compared to the rest of the bacteria, we hypothesized that the 5′ and 3′ ends of the molecule commonly used as PCR priming sites might also be the sites of unusual substitutions. In most analyses of cultured organisms and environmental genes, unusual substitutions in these regions would be obscured because the general bacterial primers in common use can anneal to target DNA despite mismatches and thereby produce PCR products in which the primer sequences are substituted for the actual sequences. In the case of our fosmid clones, however, the natural 5′ and 3′ ends of the genes could be examined because the 16S rRNA genes were subcloned instead of being amplified by PCR.

The four Planctomycetales 16S rRNA subclones each exhibited a consistent, single base substitution within the region corresponding to bacterial primer 27F (E. coli positions 8 to 27) (8). In all cases a conserved A residue at position 10 was replaced by a G residue. However, in none of the four cases was there a compensatory change in the U residue at position 24, which is thought to interact with the base at position 10 (20). This substitution is also seen in a reverse transcriptase sequence of Isosphaera pallida (14) and a genomic clone of Pirellula marina (13), suggesting that it is a feature common to all of the members of the order Planctomycetales. Interestingly, this substitution has been reported in organisms related to the genera Thermotoga (1, 3, 9) and Fervidobacterium (10) and in two spirochetes (5, 15) as well. There were no changes for three of the clones in the 3′ hybridization site that we commonly use for amplifying bacterial 16S rRNA genes (bacterial primer 1518R, E. coli positions 1541 to 1518) (8); however, all three clones differ at position 1508 within the 1492R primer (11) that is in common use. In all three cases, a G residue is substituted for an A residue. The 16S rRNA subclone for 6O13 was missing the last 60 nucleotides at the 3′ end of the gene and, thus, could not be included in sequence analysis at either the 1492R or the 1518R site. The substitutions that we report cannot be verified in database sequences obtained by PCR using primers homologous to these regions.

Four clones containing Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes were recovered in a fosmid library made from seawater, suggesting that the Planctomycetales may be an important group in this environment. These genes exhibited an unusual substitution in a widely conserved nucleotide region that is commonly used as a target site for the amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes in PCR clone libraries. Despite the single mismatch, a PCR with the 27F-1518R primer pair should amplify Planctomycetales 16S rRNA genes, although the effect of the mismatch on amplification efficiency is unknown. PCR amplification using these primers may lead to an underrepresentation of Planctomycetales and other, closely related microorganisms in these libraries. One advantage of cloning large genomic DNA fragments into fosmid vectors is that this approach provides access to information about rRNA genes missed by other approaches, such as the cloning of genes amplified by PCR. Complete sequencing and analysis of these fosmids also could yield important information about the physiology and evolutionary history of the members of the order Planctomycetales, and the clones themselves might serve as templates for manufacturing probes for microbial detection.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences described in this paper have been submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: 5H12, AF029076; 6O13, AF029077; 6N14, AF029078; and 7F15, AF029079.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant OCE-9618530 from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achenbach-Richter L, Gupta R, Stetter K O, Woese C R. Were the original eubacteria thermophiles? Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;9:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(87)80053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christen, R. 1997. Personal communication.

- 3.Davey M E, Wood W A, Key R, Nakamura K, Stahl D A. Isolation of three species of Geotoga and Petrotoga: two new genera, representing a new lineage in the bacterial line of descent distantly related to the “Thermotogales.”. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dear S, Staden R. A sequence assembly and editing program for efficient management of large projects. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3907–3911. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Defosse D L, Johnson R C, Paster B J, Dewhirst F E, Fraser G J. Brevinema andersonii gen. nov., sp. nov., an infectious spirochete isolated from the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:78–84. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogenetic inference package), version 3.57c. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuerst J A. The planctomycetes: emerging models for microbial ecology, evolution and cell biology. Microbiology. 1995;141:1493–1506. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuerst J A, Gwilliam H G, Lindsay M, Lichanska A, Belcher C, Vickers J E, Hugenholtz P. Isolation and molecular identification of planctomycete bacteria from postlarvae of the giant tiger prawn, Penaeus monodon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:254–262. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.254-262.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovannoni S J. The polymerase chain reaction. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber R, Woese C R, Langworthy T A, Fricke H, Stetter K O. Thermosipho africanus gen. nov., represents a new genus of thermophilic eubacteria within the “Thermotogales.”. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1989;12:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber R, Woese C R, Langworthy T A, Kristjansson J K, Stetter K O. Fervidobacterium islandicum sp. nov., a new extremely thermophilic eubacterium belonging to the “Thermotogales.”. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1991. pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane D J, Pace B, Olsen G J, Stahl D A, Sogin M L, Pace N R. Rapid determination of 16S RNA sequences for phylogenetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6955–6958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liesack W, Soller R, Stewart T, Haas H, Giovannoni S, Stackebrandt E. The influence of tachytelically (rapidly) evolving sequences on the topology of phylogenetic trees—intrafamily relationships and the phylogenetic position of Planctomycetaceae as revealed by comparative analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liesack W, Stackebrandt E. Occurrence of novel groups of the domain Bacteria as revealed by analysis of genetic material isolated from an Australian terrestrial environment. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5072–5078. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5072-5078.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paster B J, Dewhirst F E, Weisburg W G, Tordoff L A, Fraser G J, Hespell R B, Stanton T B, Zablen L, Mandelco L, Woese C R. Phylogenetic analysis of the spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6101–6109. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6101-6109.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staley J T. Budding bacteria of the Pasteuria-Blastobacter group. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:609–614. doi: 10.1139/m73-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein J L, Marsh T L, Wu K Y, Shizuya H, DeLong E F. Characterization of uncultivated prokaryotes: isolation and analysis of a 40-kilobase-pair genome fragment from a planktonic marine archaeon. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:591–599. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.591-599.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward N, Rainey F A, Stackebrandt E, Schlesner H. Unraveling the extent of diversity within the order Planctomycetales. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2270–2275. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2270-2275.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woese C R, Gutell R, Gupta R, Noller H F. Detailed analysis of the higher-order structure of 16S-like ribosomal ribonucleic acids. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:621–669. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.621-669.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]