Abstract

Background

Paid caregivers (e.g., home health aides) care for individuals living at home with functional impairment and serious illnesses (health conditions with high risk of mortality that impact function and quality of life).

Objective

To characterize those who receive paid care and identify factors associated with receipt of paid care in the context of serious illness and socioeconomic status.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Participants

Community-dwelling participants ≥ 65 years enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) between 1998 and 2018 with new-onset functional impairment (e.g., bathing, dressing) and linked fee-for-service Medicare claims (n = 2521).

Main Measures

Dementia was identified using HRS responses and non-dementia serious illness (e.g., advanced cancer, end-stage renal disease) was identified using Medicare claims. Paid care support was identified using HRS survey report of paid help with functional tasks.

Key Results

While about 27% of the sample received paid care, those with both dementia and non-dementia serious illnesses in addition to functional impairment received the most paid care (41.7% received ≥ 40 h of paid care per week). In multivariable models, those with Medicaid were more likely to receive any paid care (p < 0.001), but those in the highest income quartile received more hours of paid care (p = 0.05) when paid care was present. Those with non-dementia serious illness were more likely to receive any paid care (p < 0.001), but those with dementia received more hours of care (p < 0.001) when paid care was present.

Conclusions

Paid caregivers play a significant role in meeting the care needs of those with functional impairment and serious illness and high paid care hours are common among those with dementia in particular. Future work should explore how paid caregivers can collaborate with families and healthcare teams to improve the health and well-being of the seriously ill throughout the income spectrum.

KEY WORDS: serious illness, home care, palliative care, caregiving

INTRODUCTION

Caregivers provide essential support that enables people with functional impairment to remain living in the community.1,2 While family caregivers (e.g., unpaid spouses, adult children, friends) provide the majority of needed care, paid caregivers (e.g., home health aides, personal care attendants, other home care workers) may provide additional care in the home especially as needs grow. However, functional impairment rarely occurs in isolation and may co-exist with dementia and non-dementia serious illnesses (e.g., advanced cancer). Serious illness has been broadly defined to include a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacts a person’s daily function or quality of life or excessively strains their caregivers.3,4 While paid caregivers are often hired to meet discrete functional needs (e.g., bathing, dressing), evidence suggests that paid caregivers work closely with families5,6 and assist with the health-related, social, and emotional needs7–9 that are common in the setting of serious illnesses.

Yet little national information is available as to who among the functionally impaired receives paid care at home. The data that do exist provide an often cursory examination of receipt of paid care and often fail to consider the amount of paid care present, how paid care fits into total care received, or how the funding source of paid care (e.g., Medicaid, self-pay) impacts the quantity of care received. Importantly, existing data have not considered if and how co-existing serious illnesses may affect the receipt of paid care. Understanding how often and under what circumstances those with functional impairment and serious illnesses receive paid care is an essential first step to maximizing the positive impact of paid care among the vulnerable population of people with serious illnesses.10

In this study, we use a nationally representative sample of older adults with new-onset functional impairment linked with Medicare claims data to better understand receipt of paid care. Specifically, we aim to (1) compare characteristics, health utilization, and mortality of those with and without paid care, (2) describe the relationship between receipt of paid care, Medicaid, and wealth, (3) explore how paid care varies among those with dementia and non-dementia serious illnesses in the context of family caregiving, and (4) identify factors associated with receipt of paid care and higher hours of paid care in the context of socioeconomic status and serious illness.

METHODS

Sample

We identified all participants age 65 and older enrolled in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) between 1998 and 2018 (n = 24,367). HRS is a longitudinal study that uses both in-person and telephonic interviews to obtain detailed health and economic information about a nationally representative sample of older adults. We excluded those living in a nursing home or community-based residential care setting11 (n = 467). We then excluded those who had less than 12 months of fee-for-service Medicare data prior to their HRS interview (n = 14,578) so as to use claims data to identify non-dementia serious illness.4 To create a sample of individuals with functional impairment that combined observations from multiple years of HRS, we then limited our sample to those with new-onset need for help in at least one daily functional task (i.e., self-reported need for help with toileting, dressing, eating, getting in and out of bed, or bathing when no help was needed during prior HRS interview) in a given survey year. Our final sample was comprised of 2521 unique functionally impaired, community-dwelling individuals.

Measures

Paid Caregiving Support

All HRS respondents (or their proxies) are asked if help was received in the last month with daily functional tasks (as defined above) and/or household tasks (i.e., grocery shopping, meal preparation, phone calls, medications, managing money). Subsequent questions determine who helps with each task, the hours of help provided, and if the helper is paid. For each individual in our sample, we determined if paid care was present and how many hours of paid care were received. For ease of interpretation, monthly care hours were then divided by four to estimate average weekly hours of care received.

Dementia and Non-dementia Serious Illnesses

Following previous work that seeks to systematically identify people with serious illnesses using existing survey and claims data,3,4,12 people with dementia were identified using a clinically validated algorithm using data from HRS.13,14 People with non-dementia serious illness were identified through the following ICD-10 codes in Medicare claims: advanced cancer, end-stage renal disease, heart failure only if using home oxygen or hospitalized for the condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease only if using home oxygen or hospitalized for the condition, diabetes only if severe complications (ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, renal failure), liver disease with cirrhosis, hip fracture, and non-dementia neurodegenerative disorder (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and stroke only if hospitalized for the condition.3,4,14,15

Other Variables

Additional variables obtained from self-report or proxy-report in HRS included sociodemographic and family characteristics (i.e., age, gender, marital status, lives alone, lives in metropolitan area, high school education or greater, race and ethnicity, net worth, receipt of Medicaid, number of living children, family caregiving hours, ≥ 40 h of total care received per week) and functional and clinical characteristics (i.e., self-rated health, impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional tasks, impairment in ≥ 3 household tasks, number of chronic conditions). Quartile of net worth was determined for the full population. Given that financial resources impact the ability of those without Medicaid to privately hire paid caregivers, quartile of net worth was then separately calculated among those who did not have Medicaid.

Variables related to health care utilization in the year following the HRS interview included emergency department visits, hospitalizations, skilled nursing facility admissions, skilled home health services (i.e., short-term care in the home due to a need for skilled nursing or physical therapy), and hospice. These were identified through Medicare claims. Death within the 12 months following the interview was determined using data from HRS and was confirmed in Medicare claims.

Analysis

Characteristics, health utilization, and mortality of those who did and did not receive paid care were compared using the chi-square and Student’s t-test. Functional characteristics and paid and family caregiving received were described for those with dementia and non-dementia serious illnesses, as were relationships between paid care, Medicaid, and wealth. We then conducted two multivariable models. Variables in the models were chosen based on factors associated with paid care in other studies.6,16 The first examined factors associated with any paid care in the sample using logistic regression. The second examined factors associated with higher amounts of paid care among the portion of the sample who received paid care using negative binomial regressions.

Survey weights were used to obtain population estimates and for all analyses.

RESULTS

Our sample of 2521 individuals between 1998 and 2018 corresponds to an estimated population of approximately 8.8 million people living in the community with functional impairment; 27.2% received paid care. Those who received paid care were more likely to be older (84.0 vs. 79.3 years, p < 0.01), to be women (73% vs. 56.9%, p < 0.01), to live alone (51.9% vs. 19.2%, p < 0.01), and to have Medicaid (25.7% vs. 14.4%, p < 0.01) as compared to those without paid care. They were also more likely to receive ≥ 40 h of caregiving support per week (41.3% vs. 24.2%, p < 0.01) and have fewer living children (mean 3.0 vs. 3.6, p < 0.01). As compared to those without paid care, those with paid care had greater impairment in daily functional tasks (≥ 3 tasks impaired for 37.7% vs 16.6%, p < 0.01) and household tasks (≥ 3 household tasks impaired in 40.0% vs. 22.5%, p < 0.01), and were more likely to have dementia (79.4% vs. 61.7%, p < 0.01) and non-dementia serious illnesses (41.2% vs. 31.9%, p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample by Receipt of Paid Care

| Full sample (n = 2521) | Received paid care (n = 688) | No paid care (n = 1833) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and family characteristics | ||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 80.6 (9.0) | 84.0 (8.5) | 79.3 (8.7) | < 0.001 |

| Woman, % | 61.5 | 73.0 | 56.9 | < 0.001 |

| Married, % | 46.0 | 23.2 | 54.9 | < 0.001 |

| Lives alone, % | 28.5 | 51.9 | 19.2 | < 0.001 |

| Lives in metropolitan area, % | 71.3 | 71.6 | 71.2 | 0.81 |

| Education ≥ HS, % | 66.5 | 67.2 | 66.2 | 0.69 |

| Non-Hispanic White, % | 80.9 | 81.2 | 80.8 | 0.84 |

| Receives Medicaid, % | 17.6 | 25.7 | 14.4 | < 0.001 |

| Net worth (median, IQ) | 122,500 (24,500–378,000) | 115,000 (11,764–406,000) | 125,000 (29,700–371,000) | 0.31 |

| Number of living children (mean, SD) | 3.4 (2.6) | 3.0 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 40 total care hours per week, % | 29.0 | 41.3 | 24.2 | < 0.001 |

| Functional and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Self-rated health poor/fair, % | 66.6 | 70.1 | 65.2 | 0.07 |

| Impaired ≥ 3 daily functional tasks, % | 22.4 | 37.1 | 16.6 | < 0.001 |

| Impaired ≥ 3 household tasks, % | 27.5 | 40.0 | 22.5 | < 0.001 |

| Number chronic conditions, (mean, SD) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.6) | 0.09 |

| Non-dementia serious illness, % | 34.5 | 41.2 | 31.9 | < 0.001 |

| Dementia, % | 66.4 | 79.4 | 61.7 | < 0.001 |

Those who received paid care (compared to those who did not) had higher health care utilization including emergency department visits (58.5% vs 46.7%, p < 0.01), hospitalizations (20.7% vs 17.5%, p < 0.01), skilled nursing facility admissions (18.7% vs. 12.2%, p < 0.01), and skilled home health services (47.1% vs. 23.1%, p < 0.01). They were also more likely to utilize hospice (13.7% vs 7.3%, p < 0.01) and to die within 12 months following interview (20.8% vs. 13.4%, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Healthcare Utilization and Mortality over 12 Months by Receipt of Paid Care

| Full sample (n = 2521) | Received paid care (n = 688) | No paid care (n = 1833) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency department visit, % | 50.1 | 58.5 | 46.7 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization, % | 18.4 | 20.7 | 17.5 | 0.07 |

| Skilled nursing facility admission, % | 14.0 | 18.7 | 12.2 | < 0.001 |

| Skilled home health services, % | 29.9 | 47.1 | 23.1 | < 0.001 |

| Hospice, % | 9.1 | 13.7 | 17.3 | < 0.001 |

| Died, % | 15.5 | 20.8 | 13.4 | < 0.001 |

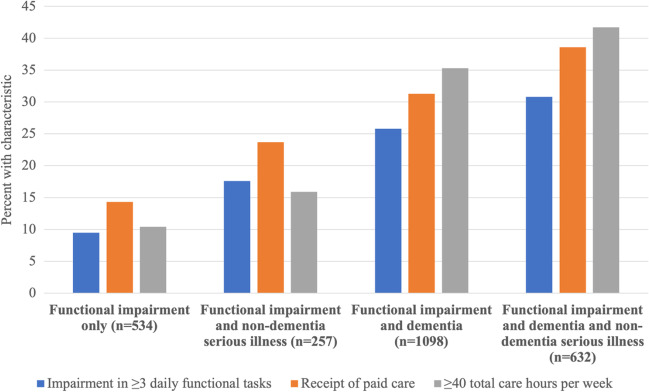

We then examined differences in the receipt of paid care by Medicaid status; those without Medicaid were divided into quartiles of wealth to facilitate more nuanced comparisons (Fig. 1). Those with Medicaid were more likely to receive any paid care compared to those without Medicaid regardless of their quartile of wealth (41.3% with paid care among those with Medicaid; on average 25.7% for those without Medicaid ranging from 19.8% in the mid-low wealth quartile to 29.2% in the highest wealth quartile). Among individuals who received paid care, average paid care hours per week were lowest among those with Medicaid (mean 25.8 h per week). Among those without Medicaid, hours of paid care received per week increased as wealth increased (26.7, 33.9, 38.6, and 43.4 h of paid care per week in the lowest, mid-low, mid-high, and highest wealth quartiles respectively).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence and hours of paid care by Medicaid status and wealth quartile.

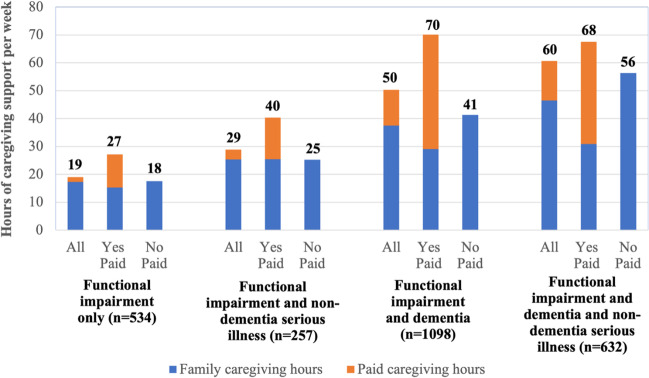

Next, we compared the functional needs and paid caregiving received among those with dementia and non-dementia serious illness (Fig. 2). Individuals with dementia and/or non-dementia serious illnesses in addition to functional impairment had a greater degree of functional impairment, more paid care, and more total care hours. For example, among those with functional impairment alone (n = 534), 9.5% had impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional tasks, 14.3% received any paid care, and 10.4% had ≥ 40 h per week of total care hours. By contrast, among those with functional impairment and both dementia and non-dementia serious illnesses (n = 632), 30.8% had impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional tasks, 38.6% received any paid care, and 41.7% had ≥ 40 h per week of total care hours.

Fig. 2.

Degree of functional impairment, receipt of paid care, and total care hours among older adults with functional impairment and serious illnesses.

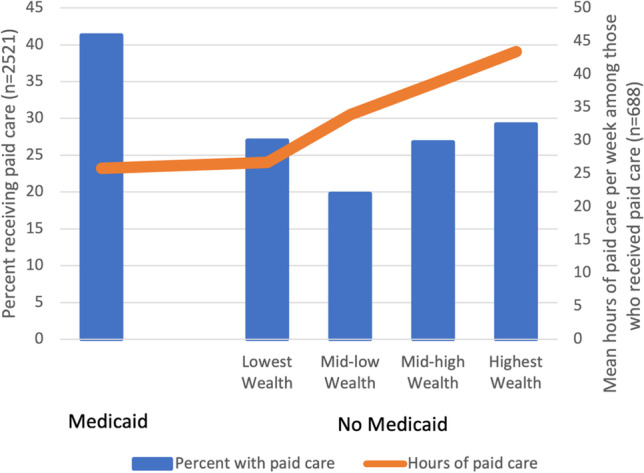

As seen in Figure 3, hours of paid, family, and total care received were higher among people with dementia and/or non-dementia serious illnesses in addition to functional impairment. When paid care was present, it accounted for about half of total care hours received (44% among those with functional impairment only, 37% among those with functional impairment and non-dementia serious illness, 58% among those with functional impairment and dementia, 54% among those with functional impairment and dementia and non-dementia serious illness). In general, those who received paid care received more total hours of care than those who did not receive paid care.

Fig. 3.

Hours of paid and family care among older adults with functional impairment and serious illnesses.

Results of multivariable models evaluating factors associated with paid care (in the full sample, n = 2521) and number of paid caregiving hours (among the subsample who received any paid care, n = 688) are in Table 3. Advanced age, being a woman, having Medicaid, being in the highest wealth quartile, living alone, impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional activities, and having at least one non-dementia serious illness were all independently associated with receipt of paid care. Being in the highest wealth quartile, impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional activities, and having dementia were all independently associated with having more paid care hours when paid care was present.

Table 3.

Multivariable Models of Factors Associated with Receipt of Any Paid Care and Number of Hours of Paid Care Received

| Any paid care | Hours of paid care* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | p value | 95% CI | Coef | p value | 95% CI |

| Age | 1.05 | < 0.001 | 1.03–1.08 | 0.00 | 0.56 | − 0.01 to 0.02 |

| Woman | 1.58 | 0.01 | 1.14–2.18 | 0.04 | 0.70 | − 0.18 to 0.27 |

| White | 1.21 | 0.24 | 0.87–1.67 | 0.12 | 0.38 | − 0.15 to 0.38 |

| Medicaid | 1.98 | < 0.001 | 1.44–2.74 | − 0.14 | 0.43 | − 0.49 to 0.21 |

| Highest quartile wealth | 1.65 | < 0.001 | 1.2–2.25 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 0.52 |

| Lives alone | 4.03 | < 0.001 | 3.08–5.3 | 0.04 | 0.75 | − 0.21 to 0.29 |

| Impairment in ≥ 3 daily functional tasks | 3.16 | < 0.001 | 2.45–4.07 | 0.92 | < 0.001 | 0.69 to 1.14 |

| Non-dementia serious illness | 1.43 | < 0.001 | 1.15–1.8 | 0.08 | 0.51 | − 0.16 to 0.32 |

| Dementia | 1.17 | 0.37 | 0.82–1.64 | 0.89 | < 0.001 | 0.58 to 1.21 |

*Hours of paid were assessed only among those receiving paid care

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative study, we found that about 30% of people with functional impairment living in the community received paid care in the home and those with dementia and/or non-dementia serious illnesses in addition to functional impairment received more paid care. While the high care needs of older adults with serious illness is well-known,2,17 the role that paid caregivers play in meeting these care needs in the community has not been previously described. This has important implications for how overall care is provided to this vulnerable population.

Our results highlight that even among a high-needs population with functional impairment, those who received paid care were more functionally impaired, medically complex, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and had greater healthcare utilization as compared to those who did not receive paid care. This suggests there may be an opportunity for paid caregivers to support the health and well-being of people with co-existing functional impairment and serious illnesses through enhanced collaboration with the healthcare teams that also provide care. Future work should specifically explore if and how high-quality paid care may help reduce unnecessary or unwanted healthcare utilization among those with functional impairment in general and with serious illnesses in particular.

However, existing evidence suggests that although many paid caregivers have the desire to work with healthcare teams to support patient health,8,9 paid caregivers are not routinely considered part of the healthcare team.18–21 Given that the contributions of paid caregivers (who are frequently women of color who earn low wages) have been historically undervalued,22,23 those providers who care for people who receive paid care need to appropriately include paid caregivers in the healthcare team. To help facilitate these collaborations, additional training in communication skills and palliative care for paid caregivers is important; currently, training for paid caregivers is highly variable state-by-state and usually focuses on skills needed to complete discrete tasks (e.g., bathing) rather than the communication skills and end of life knowledge essential for collaboration with the serious illness care team.7,24,25

Our results also underscore the important ways that financial considerations impact receipt of paid care. Those with Medicaid were more likely to receive paid care than those without Medicaid, but when paid care was present, they received fewer hours of paid care; those in the highest wealth quartile were no more likely to receive paid care as compared to all others, yet when paid care was present those in the highest wealth quartile received more paid care hours as compared to those with less wealth. These nuanced relationships between Medicaid, wealth, and paid care may help in part to explain the seemingly paradoxical finding from other studies that paid care is actually associated with more rather than less unmet care needs.26,27 Even if paid care is present, low amounts of paid care may not be sufficient to meaningfully improve patient experiences and outcomes, particularly among those with Medicaid-funded paid care. As the locus of Medicaid-funded long-term care continues to shift from institutions to the community,28 we need to consider whether or not the paid care provided is of sufficient quantity and quality to meet the extensive care needs of Medicaid recipients and explicitly examine how paid care impacts patient outcomes.29,30

Our findings also reveal how paid and family caregivers work together to meet the total care needs of the seriously ill. Particularly for those with functional impairment and dementia and/or non-dementia serious illnesses, high hours of paid care (≥ 40 h per week) are the norm. However, paid care does not simply replace family care and high paid caregiving hours occur in the context of high family caregiver hours too. Previous work suggests that additional research is needed to improve paid and family caregiver communication about roles and care expectations so that the full team of caregivers can function more effectively;31,32 our results underscore the particular importance of such communication among paid and family caregivers of the seriously ill. As growing attention is being paid to the role family caregivers play supporting the seriously ill,33,34 it is important to also consider how paid caregivers can support caregiving families.5,35

Finally, our findings provide insight into how co-existing serious illnesses shape receipt of paid care. While non-dementia serious illness was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving paid care in multivariable models, those with dementia received more paid caregiving hours when paid care was present. Evidence suggests family caregivers of people with dementia provide higher levels of care for longer periods of time as compared to family caregivers of those with other diseases.36,37 This may be driven not only by increased need for support with discrete functional tasks like those measured in HRS, but also by the need for overall supervision and continued support throughout the day. While a singular focus on dementia may obscure the fact that dementia frequently occurs in a larger context of non-dementia serious illnesses, additional training and support for the large number of paid caregivers providing dementia care is essential to make sure the unique care needs of those with dementia are met.27,38,39

This study has several limitations. Because HRS assessments occur every 2 years, our cohort of those with new-onset daily functional impairment may capture people anywhere between 0 and 2 years after functional impairment began. Our analysis relied on existing, self-report measures of caregiving received included in HRS and detailed information about payment source for paid care (e.g., Veterans Affairs, long-term care insurance), quality of paid care received, or whether unmet care needs remained despite paid care was not available. We did not include interaction terms in our analysis of factors associated with receipt of paid care. Finally, our analysis combined data from multiple years of HRS surveys among a national sample, which may obscure secular trends at the state or regional level that impact receipt of paid care.

Paid caregivers provide essential support to older adults with functional impairment and the role of paid caregivers grows when people also experience co-existing dementia and/or non-dementia serious illnesses; social and clinical factors are also associated with receipt of paid care. Future work should specifically address the role of paid caregivers in the care of the seriously ill throughout the income spectrum and identify ways to engage paid caregivers to improve the health and well-being of those living with functional impairment in the community.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23AG066930, P01AG066605, K24AG062785, R01AG054540, K23AG072037). Dr. Nothelle also acknowledges funding from Harold Young Scholarship and the Tom Secunda Foundation.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: None

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Roche-Dean M, Baik S, Moon H, Coe NB, Oh A, Zahodne LB. Paid Care Services and Transitioning Out of the Community among Black and White Older Adults with Dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/23606. [PubMed]

- 3.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the Population with Serious Illness: The “Denominator” Challenge. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S7–S16. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley AS, Covinsky KE, Gorges RJ, et al. Identifying Older Adults with Serious Illness: a Critical Step toward Improving the Value of Health Care. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(1):113–131. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reckrey JM, Boerner K, Franzosa E, Bollens-Lund E, Ornstein KA. Paid Caregivers in the Community-Based Dementia Care Team: Do Family Caregivers Benefit? Clin Ther. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reckrey JM, Li L, Zhan S, Wolff J, Yee C, Ornstein KA. Caring Together: Trajectories of Paid and Family Caregiving Support to Those Living in the Community With Dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(Suppl_1):S11–S20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reckrey JM, Tsui EK, Morrison RS, et al. Beyond Functional Support: the Range Of Health-Related Tasks Performed In The Home By Paid Caregivers In New York. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(6):927–933. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. Home Health Aides’ Perceptions of Quality Care: Goals, Challenges, and Implications for a Rapidly Changing Industry. New Solut. 2018;27(4):629–647. doi: 10.1177/1048291117740818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterling MR, Silva AF, Leung PBK, et al. “It’s Like They Forget That the Word ‘Health’ Is in ‘Home Health Aide’”: Understanding the Perspectives of Home Care Workers Who Care for Adults With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(23):e010134. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spetz J, Stone RI, Chapman SA, Bryant N. Home And Community-Based Workforce For Patients With Serious Illness Requires Support To Meet Growing Needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(6):902–909. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toth M, Palmer L, Bercaw L, Voltmer H, Karon SL. Trends in the Use of Residential Settings Among Older Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022 Feb 3;77(2):424-428. 10.1093/geronb/gbab092. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Nothelle S, Bollens-Lund E, Covinsky KE, Kelley A. Frequency and Implications of Coexistent Manifestations of Serious Illness in Older Adults with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jgs.18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):489–490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley AS, Hanson LC, Ast K, et al. The Serious Illness Population: Ascertainment via Electronic Health Record or Claims Data. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(3):e148–e155. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley AS, Ferreira KB, Bollens-Lund E, Mather H, Hanson LC, Ritchie CS. Identifying Older Adults With Serious Illness: Transitioning From ICD-9 to ICD-10. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(6):1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reckrey JM, Morrison RS, Boerner K, et al. Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(1):186–191. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nothelle S, Chamberlain AM, Jacobson D, et al. Prevalence of Co-occurring Serious Illness Diagnoses and Association with Health Care Utilization at the End of Life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2621–2629. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone RI, Bryant NS. The Future of the Home Care Workforce: Training and Supporting Aides as Members of Home-Based Care Teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S444–S448. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reckrey JM. COVID-19 Confirms It: Paid Caregivers Are Essential Members of the Healthcare Team. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1679–1680. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reckrey JM, Ornstein KA, McKendrick K, Tsui EK, Morrison RS, Aldridge M. Receipt of Hospice Aide Visits Among Medicare Beneficiaries Receiving Home Hospice Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(4):503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai D, Cloyes KG, Clayton MF, et al. We’re the Eyes and the Ears, but We Don’t Have a Voice: Perspectives of Hospice Aides. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2018;20(1):47–54. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. “Who’s Caring for Us?”: Understanding and Addressing the Effects of Emotional Labor on Home Health Aides’ Well-being. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.PHI. Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts. Accessed 16 Dec 2021. https://phinational.org/resource/direct-care-workers-in-the-united-states-key-facts-2/.

- 24.Kelly CM, Morgan JC, Jason KJ. Home Care Workers: Interstate Differences in Training Requirements and Their Implications for Quality. J Appl Gerontol. 2013;32(7):804–832. doi: 10.1177/0733464812437371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsui EK, Wang WQ, Franzosa E, et al. Training to Reduce Home Care Aides’ Work Stress Associated with Patient Death: a Scoping Review. J Palliat Med. 2019 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins Morales M, Robert SA. Examining Consequences Related to Unmet Care Needs Across the Long-Term Care Continuum. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(Suppl_1):S63–S73. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabius CD, Okoye SM, Mulcahy J, Burgdorf J, Wolff JL. Associations between Use of Paid Help and Care Experiences among Medicare-Medicaid Enrolled Older Adults with and without Dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbac072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Malley Watts M, Musumeci M, Chidambaram P. Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Enrollment and Spending. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. February 2020 Issue Brief.

- 29.Allen SM, Piette ER, Mor V. The Adverse Consequences of Unmet Need Among Older Persons Living in the Community: Dual-Eligible Versus Medicare-Only Beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S51–8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorges RJ, Sanghavi P, Konetzka RT. A National Examination of Long-Term Care Setting, Outcomes, and Disparities Among Elderly Dual Eligibles. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1110–1118. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw AL, Riffin CA, Shalev A, Kaur H, Sterling MR. Family Caregiver Perspectives on Benefits and Challenges of Caring for Older Adults With Paid Caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(12):1778–1785. doi: 10.1177/0733464820959559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reckrey JM, Watman D, Tsui EK, et al. “I Am the Home Care Agency”: the Dementia Family Caregiver Experience Managing Paid Care in the Home. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3). doi:10.3390/ijerph19031311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Schulz R, Martire LM. Family Caregiving of Persons with Dementia: Prevalence, Health Effects, and Support Strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240–249. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson P, Morrison RS, Schulz R, et al. Improving Support for Family Caregivers of People with a Serious Illness in the United States: Strategic Agenda and Call to Action. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):6–17. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falzarano FB, Cimarolli V, Boerner K, Siedlecki KL, Horowitz A. Use of Home Care Services Reduces Care-Related Strain in Long-Distance Caregivers. Gerontologist. 2022;62(2):252–261. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnab088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1642–1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reckrey JM, Bollens-Lund E, Husain M, Ornstein KA, Kelley AS. Family Caregiving for Those With and Without Dementia in the Last 10 Years of Life. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):278–279. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reckrey JM, Perez S, Watman D, Ornstein KA, Russell D, Franzosa E. The Need for Stability in Paid Dementia Care: Family Caregiver Perspectives. J Appl Gerontol. 2022:7334648221097692. doi:10.1177/07334648221097692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Goh AMY, Gaffy E, Hallam B, Dow B. An Update on Dementia Training Programmes in Home and Community Care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(5):417–423. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]