Abstract

Machine learning and deep learning are two subsets of artificial intelligence that involve teaching computers to learn and make decisions from any sort of data. Most recent developments in artificial intelligence are coming from deep learning, which has proven revolutionary in almost all fields, from computer vision to health sciences. The effects of deep learning in medicine have changed the conventional ways of clinical application significantly. Although some sub-fields of medicine, such as pediatrics, have been relatively slow in receiving the critical benefits of deep learning, related research in pediatrics has started to accumulate to a significant level, too. Hence, in this paper, we review recently developed machine learning and deep learning-based solutions for neonatology applications. We systematically evaluate the roles of both classical machine learning and deep learning in neonatology applications, define the methodologies, including algorithmic developments, and describe the remaining challenges in the assessment of neonatal diseases by using PRISMA 2020 guidelines. To date, the primary areas of focus in neonatology regarding AI applications have included survival analysis, neuroimaging, analysis of vital parameters and biosignals, and retinopathy of prematurity diagnosis. We have categorically summarized 106 research articles from 1996 to 2022 and discussed their pros and cons, respectively. In this systematic review, we aimed to further enhance the comprehensiveness of the study. We also discuss possible directions for new AI models and the future of neonatology with the rising power of AI, suggesting roadmaps for the integration of AI into neonatal intensive care units.

Subject terms: Translational research, Paediatric research

Introduction

The AI tsunami fueled by advances in artificial intelligence (AI) is constantly changing almost all fields, including healthcare; it is challenging to track the changes originated by AI as there is not a single day that AI is not applied to anything new. While AI affects daily life enormously, many clinicians may not be aware of how much of the work done with AI technologies may be put into effect in today’s healthcare system. In this review, we fill this gap, particularly for physicians in a relatively underexplored area of AI: neonatology. The origins of AI, specifically machine learning (ML), can be tracked all the way back to the 1950s, when Alan Turing invented the so-called “learning machine” as well as military applications of basic AI1. During his time, computers were huge, and the cost of increased storage space was astronomical. As a result, their capabilities, although substantial for their day, were restricted. Over the decades, incremental advancements in theory and technological advances steadily increased the power and versatility of ML2.

How do machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) work? ML falls under the category of AI2. ML’s capacity to deal with data brought it to the attention of computer scientists. ML algorithms and models can learn from data, analyze, evaluate, and make predictions or decisions based on learning and data characteristics. DL is a subset of ML. Different from this larger class of ML definitions, the underlying concept of DL is inspired by the functioning of the human brain, particularly the neural networks responsible for processing and interpreting information. DL mimics this operation by utilizing artificial neurons in a computer neural network. In simple terms, DL finds weights for each artificial neuron that connects to each other from one layer to another layer. Once the number of layers is high (i.e., deep), more complex relationships between input and output can be modeled3–5. This enables the network to acquire more intricate representations of the data as it learns. The utilization of a hierarchical approach enables DL models to autonomously extract features from the data, as opposed to depending on human-engineered features as is customary in conventional ML3. DL is a highly specialized form of ML that is ideally modified for tasks involving unstructured data, where the features in the data may be learnable, and exploration of non-linear associations in the data can be possible6–8.

The main difference between ML and DL lies in the complexity of the models and the size of the datasets they can handle. ML algorithms can be effective for a wide range of tasks and can be relatively simple to train and deploy6,7,9–11. DL algorithms, on the other hand, require much larger datasets and more complex models but can achieve exceptional performance on tasks that involve high-dimensional, complex data7. DL can automatically identify which aspects are significant, unlike classical ML, which requires pre-defined elements of interest to analyze the data and infer a decision10. Each neuron in DL architectures (i.e., artificial neural networks (ANN)) has non-linear activation function(s) that help it learn complex features representative of the provided data samples9.

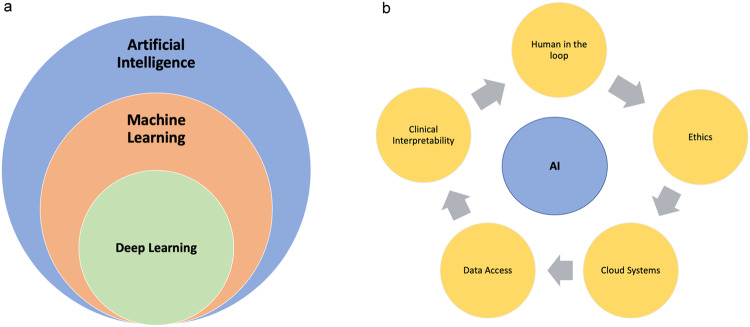

ML algorithms, hence, DL, can be categorized as either supervised, unsupervised, or reinforcement learning based on the input-output relationship. For example, if output labels (outcome) are fully available, the algorithm is called “supervised,” while unsupervised algorithms explore the data without their reference standards/outcomes/labels in the output3,12. In terms of applications, both DL and ML are typically used for tasks such as classification, regression, and clustering6,9,10,13–15. DL methods’ success depends on the availability of large-scale data, new optimization algorithms, and the availability of GPUs6,10. These algorithms are designed to autonomously learn and develop as they gain experience, like humans3. As a result of DL’s powerful representation of the data, it is considered today’s most improved ML method, providing drastic changes in all fields of medicine and technology, and it is the driving force behind virtually all progress in AI today5 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Exploring AI Hierarchy and Challenges in Healthcare.

a Hierarchical diagram of AI. How do machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) work? ML falls under the category of AI. DL is a subset of ML. b Ongoing hurdles of AI when applied to healthcare applications. Key concerns related to AI and each concern affects the outcome of AI in Neonatology including; (1) challenges with clinical interpretability; (2) knowledge gaps in decision-making mechanisms, with the latter requiring human-in-the-loop systems (3) ethical considerations; (4) the lack of data and annotations, and (5) the absence of Cloud systems allowing for secure data sharing and data privacy.

There are three major problem types in DL in medical imaging: image segmentation, object detection (i.e., an object can be an organ or any other anatomical or pathological entity), and image classification (e.g., diagnosis, prognosis, therapy response assessment)3. Several DL algorithms are frequently employed in medical research; briefly, those approaches belong to the following family of algorithms:

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are predominantly employed for tasks related to computer vision and signal processing. CNNs can handle tasks requiring spatial relationships where the columns and rows are fixed, such as imaging data. CNN architecture encompasses a sequence of phases (layers) that facilitate the acquisition of hierarchical features. Initial phases (layers) extract more local features such as corners, edges, and lines, later phases (layers) extract more global features. Features are propagated from one layer to another layer, and feature representation becomes richer this way. During feature propagation from one layer to another layer, the features are added certain nonlinearities and regularizations to make the functional modeling of input-output more generalizable. Once features become extremely large, there are operations within the network architecture to reduce the feature size without losing much information, called pooling operations. The auto-generated and propagated features are then utilized at the end of the network architecture for prediction purposes (segmentation, detection, or classification)3,16.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are designed to facilitate the retention of sequential data, namely text, speech, and time-series data such as clinical data or electronic health records (EHRs). They can capture temporal relationships between data components, which can be helpful for predicting disease progression or treatment outcomes11,17,18. RNNs use similar architecture components that CNNs have. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models are types of RNNs and are commonly used to overcome their shortcomings because they can learn long-term dependencies in data better than conventional RNN architectures. They are utilized in some classification tasks, including audio17,19. LSTM utilizes a gated memory cell in the network architecture to store information from the past; hence, the memory cell can store information for a long period of time, even if the information is not immediately relevant to the current task. This allows LSTMs to learn patterns in data that would be difficult for other types of neural networks to learn.

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) are a class of DL models that can be used to generate new data that is like existing data. In healthcare, GANs have been used to generate synthetic medical images. There are two CNNs (generator and discriminator); the first CNN is called the generator, and its primary goal is to make synthetic images that mimic actual images. The second CNN is called the discriminator, and its main objective is to identify between artificially generated images and real images20. The generator and discriminator are trained jointly in a process called adversarial training, where the generator tries to create data that is so realistic that the discriminator cannot distinguish it from real data. GANs are used to generate a variety of different types of data, including images, videos, and text. GANs are used to enhance image quality, signal reconstruction, and other tasks such as classification and segmentation too20–22.

Transfer learning (TL) is a concept derived from cognitive science that states that information is transferred across related activities to improve performance on a new task. It is generally known that people can accomplish similar tasks by building on prior knowledge23. TL has been implemented to minimize the need for annotation by transferring DL models with knowledge from a previous task and then fine-tuning them in the current task24. The majority of medical image classification techniques employ TL from pretrained models, such as ImageNet, which has been demonstrated to be inefficient due to the ImageNet consisting of natural images25. The approaches that utilized ImageNet pre-trained images in CNNs revealed that fine-tuning more layers provided increased accuracy26. The initial layers of ImageNet-pretrained networks, which detect low-level image characteristics, including corners and borders, may not be efficient for medical images25,26.

New and more advanced DL algorithms are developed almost daily. Such methods could be employed for the analysis of imaging and non-imaging data in order to enhance performance and reliability. These methods include Capsule Networks, Attention Mechanisms, and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)27–30. Briefly, these are:

Capsule Networks are a relatively new form of DL architecture that aim to address some of the shortcomings of CNNs: pooling operations (reducing the data size) and a lack of hierarchical relations between objects and their parts in the data. Capsules can capture spatial relationships between features and are more capable of handling rotations and deformations of image objects thanks to their vectorial representations in neuronal space. Capsule Networks have shown potential in image classification tasks and could have applications in medical imaging analysis27. However, its implementation and computational time are two hurdles that restrict its widespread use.

Attention Mechanisms, represented by Transformers, have contributed to the development of computer vision and language processing. Unlike CNNs or RNNs, transformers allow direct interaction between every pair of components within a sequence, making them particularly effective at capturing long-term relationships29,30. More specifically, a self-attention mechanism in Transformers is an important piece of the DL model as it can dynamically focus on different parts of the input data sequence when producing an output, providing better context understanding than CNN based systems.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are a form of data structure that describes a collection of objects (nodes) and their relationships (edges). There are three forms of tasks, including node-level, edge-level, and graph level31. Graphs may be used to denote a wide range of systems, including molecular interaction networks, and bioinformatics31–33. GNNs have demonstrated potential in both imaging and non-imaging data analysis28,34.

Physics-driven systems are needed in imaging field. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of DL methods in the medical imaging field35–39. As the field of DL continues to evolve, it is likely that new methods and architectures will emerge to address the unique challenges and constraints of various types of data. One of the most common problems faced with DL-based MRI construction35. Specific algorithms for this problem can be essentially categorized into two groups: data driven and physics driven algorithms. In purely data-driven approaches, a mapping is learned between the aliased image and the image without artifacts39. Acquiring fully sampled (artifact-free) datasets is impractical in many clinical imaging studies when organs are in motion, such as the heart, and lung. Recently developed models can employ these under sampled MRI acquisitions as input and generate output images consistent with fully-sampled (artifact free) acquisitions37–39.

What is the Hybrid Intelligence? A highly desirable way of incorporating advances in AI is to let AI and human intellect work together to solve issues, and this is referred to as “hybrid intelligence“40 (e.g., one may call this “mixed intelligence” or “human-in-the-loop AI systems”). This phenomenon involves the development of AI systems that serve to supplement and amplify human decision-making processes, as opposed to completely replacing them3. The concept involves integrating the respective competencies of artificial intelligence and human beings in order to attain superior outcomes that would otherwise be unachievable41. AI algorithms possess the ability to process extensive amounts of data, recognize patterns, and generate predictions rapidly and precisely. Meanwhile, humans can contribute their expertise, understanding, and intuition to the discussion to offer context, analyze outcomes, and render decisions42. The hybrid intelligence strategy can help decision-makers in a variety of fields make decisions that are more precise, effective, and efficient by combining these qualities3,4,43,44. Human in the loop and hybrid intelligence systems are promising for time-consuming tasks in healthcare and neonatology.

Where do we stand currently? AI in medicine has been employed for over a decade, and it has often been considered that clinical implementation is not completely adapted to daily practice in most of the clinical field5,45,46. In recent years, increasingly complex computer algorithms and updated hardware technologies for processing and storing enormous datasets have contributed to this achievement6,7,46,47. It has only been within the last decade that these systems have begun to display their full potential6,9. The field of AI research appears to have been taken up with differing degrees of enthusiasm across disciplines. When analyzing the thirty years of research into AI, DL, and ML conducted by several medical subfields between the years 1988 and 2018, one-third of publications in DL yielded to radiology, and most of them are within the imaging sciences (radiology, pathology, and cell imaging)48. Software systems work by utilizing biomedical images with predictive/diagnostic/prognostic features and integrating clinical or pre-clinical data. These systems are designed with ML algorithms46. Such breakthrough methods in DL are nowadays extensively applied in pathology, dermatology, ophthalmology, neurology, and psychiatry6,47,49. AI has its own difficulties with the increasing utilization of healthcare (Fig. 1b).

What are the needs in clinics? Clinicians are concerned about the healthcare system’s integration with AI: there is an exponential need for diagnostic testing, early detection, and alarm tools to provide diagnosis and novel treatments without invasive tests and procedures50. Clinicians have higher expectations of AI in their daily practices than before. AI is expected to decrease the need for multiple diagnostic invasive tests and increase diagnostic accuracy with less invasive (or non-invasive) tests. Such AI systems can easily recognize imaging patterns on test images (i.e., unseen or not utilized efficiently in daily routines), allowing them to detect and diagnose various diseases. These methods could improve detection and diagnosis in different fields of medicine.

The overall goal of this systematic review is to explain AI’s potential use and benefits in the field of neonatology. We intend to enlighten the potential role of AI in the future in neonatal care. We postulate that AI would be best used as a hybrid intelligence (i.e., human-in-the-loop or mixed intelligence) to make neonatal care more feasible, increase the accuracy of diagnosis, and predict the outcome and diseases in advance. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In results, we explain the published AI applications in neonatology along with AI evaluation metrics to fully understand their efficacy in neonatology and provide a comprehensive overview of DL applications in neonatology. In discussion, we examine the difficulties of AI utilization in neonatology and future research discussions. In the methods section, we outline the systematic review procedures, including the examination of existing literature and the development of our search strategy.

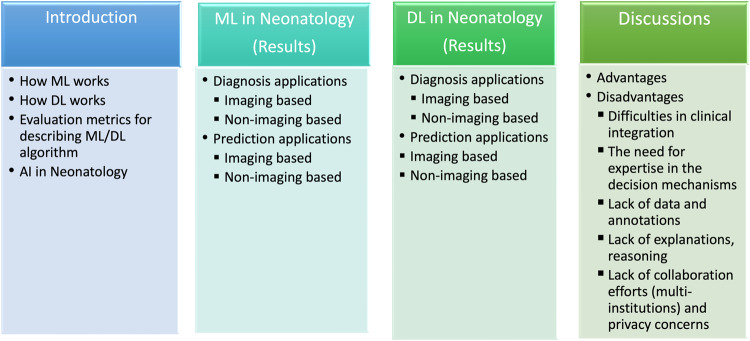

We review the past, current, and future of AI-based diagnostic and monitoring tools that might aid neonatologists’ patient management and follow-up. We discuss several AI designs for electronic health records, image, and signal processing, analyze the merits and limits of newly created decision support systems, and illuminate future views clinicians and neonatologists might use in their normal diagnostic activities. AI has made significant breakthroughs to solve issues with conventional imaging approaches by identifying clinical variables and imaging aspects not easily visible to human eyes. Improved diagnostic skills could prevent missed diagnoses and aid in diagnostic decision-making. The overview of our study is structured as illustrated in Fig. 2. Briefly, our objectives in this systematic review are:

to explain the various AI models and evaluation metrics thoroughly explained and describe the principal features of the AI models,

to categorize neonatology-related AI applications into macro-domains, to explain their sub-domains and the important elements of the applicable AI models,

to examine the state-of-the-art in studies, particularly from the past several years, with an emphasis on the use of ML in encompassing all neonatology,

to present a comprehensive overview and classification of DL applications utilized and in neonatology,

to analyze and debate the current and open difficulties associated with AI in neonatology, as well as future research directions, to offer the clinician a comprehensive perspective of the actual situation.

Fig. 2. An overview of the structure of this paper.

It is provided an overview of our paper’s structure and objectives: 1. Explaining AI Models and Evaluation Metrics: 2. Evaluating ML applied studies in Neonatology 3. Evaluating DL applied studies in Neonatology 4. Analyzing Challenges and Future Directions.

AI covers a broad concept for the application of computing algorithms that can categorize, predict, or generate valuable conclusions from enormous datasets46. Algorithms such as Naive Bayes, Genetic Algorithms, Fuzzy Logic, Clustering, Neural Networks (NN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, and Random Forests (RF) have been used for more than three decades for detection, diagnosis, classification, and risk assessment in medicine as ML methods9,10. Conventional ML approaches for image classification involve using hand-engineered features, which are visual descriptions and annotations learned from radiologists, that are encoded into algorithms.

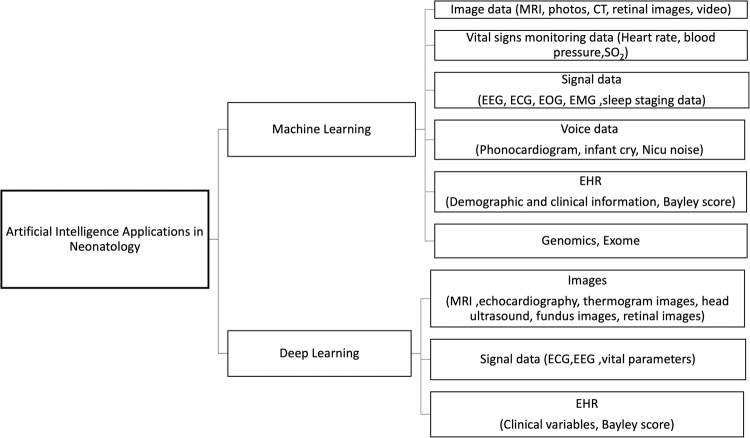

Images, signals, genetic expressions, EHR, and vital signs are examples of the various unstructured data sources that comprise medical data (Fig. 3). Due to the complexity of their structures, DL frameworks may take advantage of this heterogeneity by attaining high abstraction levels in data analysis.

Fig. 3. An overview of AI applications in neonatology.

Unstructured data such as medical images, vital signals, genetic expressions, EHRs, and signal data contribute to the wide variety of medical information. Analyzing and interpreting different data streams in neonatology requires a comprehensive strategy because each has unique characteristics and complications.

While ML requires manual/hand-crafted selection of information from incoming data and related transformation procedures, DL performs these tasks more efficiently and with higher efficacy9,10,46. DL is able to discover these components by analyzing a large number of samples with a high degree of automation7. The literature on these ML approaches is extensive before the development of DL5,7,45.

It is essential for clinicians to understand how the suggested ML model should enhance patient care. Since it is impossible for a single metric to capture all the desirable attributes of a model, it is customarily necessary to describe the performance of a model using several different metrics. Unfortunately, many end-users do not have an easy time comprehending these measurements. In addition, it might be difficult to objectively compare models from different research models, and there is currently no method or tool available that can compare models based on the same performance measures51. In this part, the common ML and DL evaluation metrics are explained so neonatologists could adapt them into their research and understand of upcoming articles and research design51,52.

AI is commonly utilized everywhere, from daily life to high-risk applications in medicine. Although slower compared to other fields, numerous studies began to appear in the literature investigating the use of AI in neonatology. These studies have used various imaging modalities, electronic health records, and ML algorithms, some of which have barely gone through the clinical workflow. Though there is no systematic review and future discussions in particular in this field53–55. Many studies were dedicated to introducing these systems into neonatology. However, the success of these studies has been limited. Lately, research in this field has been moving in a more favorable direction due to exciting new advances in DL. Metrics for evaluations in those studies were the standard metrics such as sensitivity (true-positive rate), specificity (true-negative rate), false-positive rate, false-negative rate, receiver operating characteristics (ROC), area under the ROC curves (AUC), and accuracy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation metrics in artificial intelligence.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| True Positive (TP) | The number of positive samples that have been correctly identified. |

| True Negative (TN) | The number of samples that were accurately identified as negative. |

| False Positive (FP) | The number of samples that were incorrectly identified as positive. |

| False Negative (FN) | The number of samples that were incorrectly identified as negative. |

| Accuracy (ACC) |

The proportion of correctly identified samples to the total sample count in the assessment dataset. The accuracy is limited to the range [0, 1], where 1 represents properly predicting all positive and negative samples and 0 represents successfully predicting none of the positive or negative samples. |

| Recall (REC) | The sensitivity or True Positive Rate (TPR) is the proportion of correctly categorized positive samples to all samples allocated to the positive class. It is computed as the ratio of correctly classified positive samples to all samples assigned to the positive class. |

| Specificity (SPEC) | The negative class form of recall (sensitivity) and reflects the proportion of properly categorized negative samples. |

| Precision (PREC) | The ratio of correctly classified samples to all samples assigned to the class. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | The proportion of correctly classified positive samples to all positive samples. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | The ratio of samples accurately identified as negative to all samples classified as negative. |

| F1 score (F1) | The harmonic mean of precision and recall, which eliminates excessive levels of either. |

| Cross Validation | A validation technique often employed during the training phase of modeling, without no duplication among validation components. |

| AUROC (Area under ROC curve - AUC) | A function of the effect of various sensitivities (true-positive rate) on false-positive rate. It is limited to the range [0, 1], where 1 represents properly predicting all cases of all and 0 represents predicting the none of cases. |

| ROC | By displaying the effect of variable levels of sensitivity on specificity, it is possible to create a curve that illustrates the performance of a particular predictive algorithm, allowing readers to easily capture the algorithm’s value. |

| Overfitting | Modeling failure indicating extensive training and poor performance on tests. |

| Underfitting | Modeling failure indicating inadequate training and inadequate test performance. |

| Dice Similarity Coefficient | Used for image analysis. It is limited to the range [0, 1], where 1 represents properly segmenting of all images and 0 represents successfully segmenting none of images. |

Results

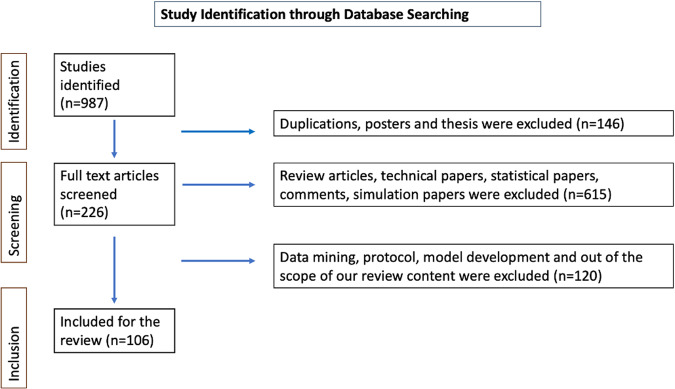

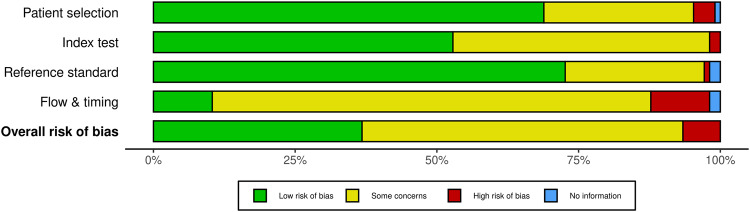

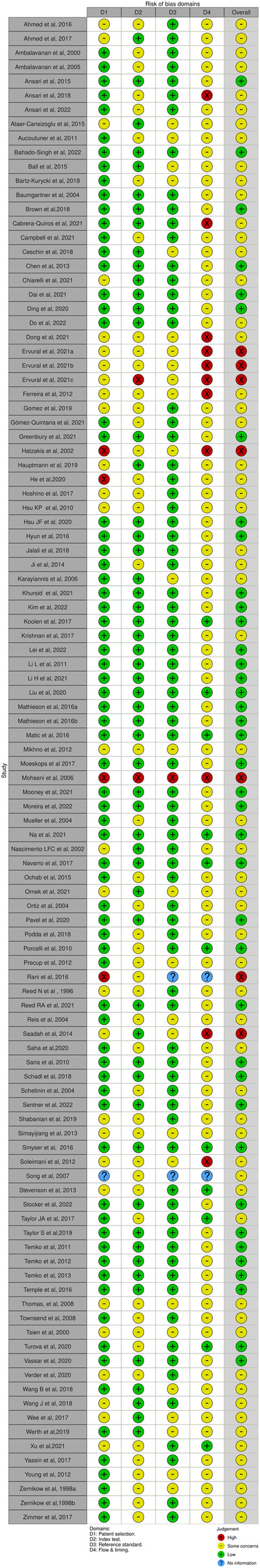

This systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol56. The search was completed on 11st of July 2022. The initial search yielded many articles (approximately 9000), and we utilized a systematic approach to identify and select relevant articles based on their alignment with the research focus, study design, and relevance to the topic. We checked the article abstracts, and we identified 987 studies. Our search yielded 106 research articles between 1996 and 2022 (Fig. 4). Risk of bias summary analysis was done by the QUADAS-2 tool (Figs. 5 and 6)57–59.

Fig. 4. Identification of studies through database searches.

Initial research conducted on 11th of July 2022, yielded 9000 articles, of which 987 article abstracts were screened. Of those, 106 research articles published between 1996 and 2022 were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process in more detail.

Fig. 5. Bias summary of all research according to the QUADAS-2.

Risk of bias summary analysis was done by the QUADAS-2 tool.

Fig. 6. Bias summary of all studies according to the QUADAS-2.

Risk of bias summary analysis was done by the QUADAS-2 tool.

Our findings are summarized in two groups of tables: Tables 2–5 summarize the AI methods from the pre-deep learning era (“Pre-DL Era”) in neonatal intensive care units according to the type of data and applications. Tables 6, 7, on the other hand, include studies from the DL Era. Applications include classification (i.e., prediction and diagnosis), detection (i.e., localization), and segmentation (i.e., pixel level classification in medical images).

Table 2.

ML based (non-DL) studies in neonatology using imaging data for diagnosis.

| Study | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | Type of data | Performance | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | ||||||

| Hoshino et al., 2017194 | CLAFIC, logistic regression analysis |

To determine optimal color parameters predicting Biliary atresia (BA)stools |

50 neonates | 30 BA and 34 non-BA images | 100% (AUC) |

+ Effective and convenient modality for early detection of BA, and potentially for other related diseases |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Dong et al., 2021195 | Level Set algorithm |

To evaluate the postoperative enteral nutrition of neonatal high intestinal obstruction and analyze the clinical treatment effect of high intestinal obstruction |

60 neonates | CT images | 84.7% (accuracy) | + Segmentation algorithm can accurately segment the CT image, so that the disease location and its contour can be displayed more clearly. |

|

- EHR (not included AI analysis) - Small sample size - Retrospective design | ||||||

| Ball et al., 201590 | Random Forest (RF) | To compare whole-brain functional connectivity in preterm newborns at term-equivalent age with healthy term-born neonates in order to determine if preterm birth leads in particular changes to functional connectivity by term-equivalent age. | 105 preterm infants and 26 term controls |

Both resting state functional MRI and T2-weighted Brain MRI |

80% (accuracy) |

+ Prospective + Connectivity differences between term and preterm brain |

| - Not well-established model | ||||||

| Smyser et al., 201688 |

Support vector machine (SVM)-multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) |

To compare resting state-activity of preterm-born infants (Scanned at term equivalent postmenstrual age) to term infants |

50 preterm infants (born at 23–29 weeks of gestation and without moderate–severe brain injury) 50 term-born control infants studied |

Functional MRI data + Clinical variables |

84% (accuracy) |

+ Prospective + GA at birth was used as an indicator of the degree of disruption of brain development + Optimal methods for rs-fMRI data acquisition and preprocessing for this population have not yet been rigorously defined |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Zimmer et al., 201793 | NAF: Neighborhood approximation forest classifier of forests | To reduce the complexity of heterogeneous data population, manifold learning techniques are applied, which find a low-dimensional representation of the data. |

111 infants (NC, 70 subjects), affected by IUGR (27 subjects) or VM (14 subjects). |

3 T brain MRI |

80% (accuracy) |

+ Combining multiple distances related to the condition improves the overall characterization and classification of the three clinical groups (Normal, IUGR, Ventriculomegaly) |

|

- The lack of neonatal data due to challenges during acquisition and data accessibility - Small sample size | ||||||

| Krishnan et al., 2017100 |

Unsupervised machine learning: Sparse Reduced Rank Regression (sRRR) |

Variability in the Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor (PPAR) pathway would be related to brain development |

272 infants born at less than 33 wk gestational age (GA) |

Diffusion MR Imaging Diffusion Tractography Genome wide Genotyping |

63% (AUC) | + Inhibited brain development found in individuals exposed to the stress of a preterm extrauterine world is controlled by genetic variables, and PPARG signaling plays a previously unknown cerebral function |

|

- Further work is required to characterize the exact relationship between PPARG and preterm brain development, notably to determine whether the effect is brain specific or systemic | ||||||

| Chiarelli et al., 202191 | Multivariate statistical analysis |

To better understand the effect of prematurity on brain structure and function, |

88 newborns |

3 Tesla BOLD and anatomical brain MRI Few clinical variables |

The multivariate analysis using motion information could not significantly infer GA at birth |

+ Prematurity was associated with bidirectional alterations of functional connectivity and regional volume |

|

- Retrospective design - Small sample size | ||||||

| Song et al., 200794 | Fuzzy nonlinear support vector machines (SVM). |

Neonatal brain tissue segmentation in clinical magnetic resonance (MR) images |

10 term neonates | Brain MRI T1 and T2 weighted |

70%–80% (dice score-gray matter) 65%–80% (dice score-white matter) |

+ Nonparametric modeling adapts to the spatial variability in the intensity statistics that arises from variations in brain structure and image inhomogeneity + Produces reasonable segmentations even in the absence of atlas prior |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Taylor et al., 2017137 | Machine Learning |

Technology that uses a smartphone application has the potential to be a useful methodology for effectively screening newborns for jaundice |

530 newborns |

Paired BiliCam images total serum bilirubin (TSB) levels |

High-risk zone TSB level was 95% for BiliCam and 92% for TcB (P = 0.30); for identifying newborns with a TSB level of ≥17.0, AUCs were 99% and 95%, respectively (P =0.09). |

+ Inexpensive technology that uses commodity smartphones could be used to effectively screen newborns for jaundice + Multicenter data + Prospective design |

| - Method and algorithm name were not explained | ||||||

| Ataer-Cansizoglu et al., 2015134 |

Gaussian Mixture Models i-ROP |

To develop novel computer based image analysis system for grading plus diseases in ROP | 77 wide-angle retinal images |

95% (accuracy) |

+ Arterial and venous tortuosity (combined), and a large circular cropped image (with radius 6 times the disc diameter), provided the highest diagnostic accuracy + Comparable to the performance of the 3 individual experts (96%, 94%, 92%), and significantly higher than the mean performance of 31 nonexperts (81%) |

|

|

- Used manually segmented images with a tracing algorithm to avoid the possible noise and bias that might come from an automated segmentation algorithm - Low clinical applicability | ||||||

| Rani et al., 2016133 | Back Propagation Neural Networks | To classify ROP |

64 RGB images of these stages have been taken, captured by RetCam with 120 degrees field of view and size of 640 × 480 pixels. |

90.6% (accuracy) |

- No clinical information - Required better segmentation - Clinical adaptation |

|

| Karayiannis et al., 2006101 | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) |

To aim at the development of a seizure-detection system by training neural networks with quantitative motion information extracted from short video segments of neonatal seizures of the myoclonic and focal clonic types and random infant movements |

54 patients |

240 video segments (Each of the training and testing sets contained 120 video segments (40 segments of myoclonic seizures, 40 segments of focal clonic seizures, and 40 segments of random movements |

96.8% (sensitivity) 97.8% (specificity) |

+ Video analysis |

|

- Not be capable of detecting neonatal seizures with subtle clinical manifestations (Subclinical seizures) or neonatal seizures with no clinical manifestations (electrical-only seizures - Not include EEG analysis - Small sample size - No additional clinical information |

Table 5.

ML based (non-DL) studies in neonatology using non-imaging data for prediction.

| Reference | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | Type of data | Performance | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | ||||||

| Soleimani et al., 2012141 |

Multilayer perceptron (MLP) (ANN) |

Predict developmental disorder | 6150 infants’ |

Infant Neurological International Battery (INFANIB) and prenatal factors |

79% (AUC) | + Neural network ability includes quantitative and qualitative data |

|

- Relying on preexisting data - Missing important topics - Small sample size | ||||||

| Zernikow et al., 199868 | ANN | To predict the individual neonatal mortality risk | 890 preterm neonates | Clinical records | 95% (AUC) | + ANN predict mortality accurately |

| - Its high rate of prediction failure | ||||||

| Ji et al., 2014139 | Generalized linear mixed-effects models |

To develop the NEC diagnostic and prognostic models |

520 infants | Clinical variables | 84%–85% (AUC) | + Prediction of NEC and risk stratification. |

| - Non-image data | ||||||

| Young et al., 2012203 | Multilayer perceptron (MLP) ANN |

To forecasting the sound loads in NICUs |

72 individual data | Voice record- | + Prediction of noise levels | |

| - Limited only to time and noise level | ||||||

| Nascimento LFC et al., 200264 | A fuzzy linguistic model |

To estimate the possibility of neonatal mortality. |

58 neonatal deaths in 1351 records. | EHR |

It depends on the GA, APGAR score and BW 90% (accuracy) |

+ Not to compare this model with other predictive models because the fuzzy model does not use blood analyses and current models such as PRISM, SNAP or CRIB do not use the fuzzy variables |

| - No change over the time | ||||||

| Reis et al., 2004204 | Fuzzy composition | Determine if more intensive neonatal resuscitation procedures will be required during labor and delivery |

Nine neonatologists facing which a degree of association with the risk of occurrence of perinatal asphyxia |

61 antenatal and intrapartum clinical situations | 93% (AUC) |

+ Maternal medical, obstetric and neonatal characteristics to the clinical conditions of the newborn, providing a risk measurement of need of advanced neonatal resuscitation measures |

|

- Implement a supplemental system to help health care workers in making perinatal care decisions. - Eighteen of the factors studied were not tested by experimental analysis, for which testing in a multicenter study or over a very long period of time in a prospective study would be probably needed | ||||||

| - No image | ||||||

| Jalali et al., 2018147 | SVM | To predict the development of PVL by analyzing vital sign and laboratory data received from neonates shortly following heart surgery | 71 neonates(including HLHS and TGA) |

Physiological and clinical data Up to 12 h after cardiac surgery |

88% (AUC) | + Might be used as an early prediction tool |

|

- Retrospective observational study - Other variables did not collected which precipitated the PVL | ||||||

| Ambalavanan et al., 2000140 | ANN | To predict adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in ELBW |

218 neonates 144 for training 74 for test set |

Clinical variables and Bayley scores at 18 months | 62% (Major handicapped-AUC) | + Neural network is more sensitive detection individual mortality |

|

- Short follow-up - Underperformance of neural network | ||||||

| Saria et al., 2010 146 |

Bayesian modeling paradigm Leave one out algorithm |

To develop morbidity prediction tool | To identify infants who are at risk of short- and long-term morbidity in advance | Electronically collected physiological data from the first 3 hours of life in preterm newborns (<34 weeks gestation, birth weight <2000 gram) of 138 infants | 91.9% (AUC-predicting high morbidity) | + Physiological variables, notably short-term variability in respiratory and heart rates, contributed more to morbidity prediction than invasive laboratory tests. |

| Saadah et al., 2014205 | ANN |

To identify subgroups of premature infants who may benefit from palivizumab prophylaxis during nosocomial outbreaks of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection |

176 infants 31 (17.6%) received palivizumab during the outbreaks |

EHR |

In male infants whose birth weight was less than 0.7 kg and who had hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. |

- Retrospective analysis using an AI model - No external validation - Low generalizability - Small sample size |

| Mikhno et al., 2012128 | Logistic Regression Analysis |

Developed a prediction algorithm to distinguish patients whose extubation attempt was successful from those that had EF |

179 neonates |

EHR 57 candidate features Retrospective data from the MIMIC-II database |

87.1% (AUC) |

+ A new model for EF prediction developed with logistic regression, and six variables were discovered through ML techniques |

|

- 2 hour prior extubation took into consideration - Longer duration should be encountered | ||||||

| Gomez et al., 201974 |

AdaBoost Bagged Classification Trees (BCT) Random Forest(RF) Logistic Regression (LR) SVM |

To predict sepsis in term neonates within 48 hours of life monitoring heart rate variability(HRV) and EHR |

79 newborns 15 were diagnosed with sepsis |

4 EHR variables and HRV variables. HRV variables were analyzed with the ML methods |

94.3% (AUC) AdaBoost 88.8% (AUC) Bagged Classification Trees Lowest AUC 64% (k-NN) |

+ Noninvasive methods for sepsis prediction |

|

- Small sample size - Need an extra software for HRV analysis - Not included EHR into ML analysis - No Adequate Clinical Information | ||||||

| Verder et al., 2020125 | Support vector machine (SVM) |

To develop a fast bedside test for prediction and early targeted intervention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) to improve the outcome |

61 very preterm infants were included in the study |

Spectral pattern analysis of gastric aspirate combined with specific clinical data points |

Sensitivity: 88% Specificity: 91% |

+ Multicenter non-interventional diagnostic cohort study + Early prediction and targeted intervention of BPD have the potential to improve the outcome + First algorithm developed by AI to predict BPD after shortly birth with high sensitivity and specificity. |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Ochab et al., 2015126 | SVM and logistic regression | To predict BPD in LBW infant | 109 neonates | EHR (14 risk factors) | 83.2% (accuracy) | + Decision support system |

|

- Small sample size - Few clinical variables - Low accuracy with SVM - A single-center design leads to missing data and unavoidable biases in identifying and recruiting participants | ||||||

| Townsend et al., 200862 | ANN | To predict events in the NICU |

Data collected by the CNN between January 1996 and October 1997 contains data from 17 NICUs |

27 clinical variables | 85% (AUC) |

+ Modeling life-threatening complications will be combined with a case-presentation tool to provide physicians with a patient’s estimated risk for several important outcomes |

|

+ Annotations would be created prospectively with adequate details for understanding any surrounding clinical conditions occurring during alarms | ||||||

|

- The methodology employed for data annotation - Retrospective design - Not confirmed with real clinical situations - Data may not capture short-lived artifacts and thus these models would not be effectively designed to detect such artifacts in a prospective setting | ||||||

| Ambalavanan et al., 200563 | ANN and logistic regression | To predict death of ELBW infant | 8608 ELBW infants | 28 clinical variables |

84% (AUC) 85% (AUC) |

+ The difficulties of predicting death should be acknowledged in discussions with families and caregivers about decisions regarding initiation or continuation of care |

|

- Chorioamnionitis, timing of prenatal steroid therapy, fetal biophysical profile, and resuscitation variables such as parental or physician wishes regarding resuscitation) could not be evaluated because they were not part of the data collected. | ||||||

| Bahado-Singh et al., 2022200 |

Random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), prediction analysis for microarrays (PAM), and generalized linear model (GLM) |

Prediction of coarctation in neonates | Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of newborn blood DNA |

24 patients 16 controls |

97% (80%–100%) (AUC) |

+ AI in epigenomics + Accurate prediction of CoA |

|

- Small dataset - Not included other CHD | ||||||

| Bartz-Kurycki et al., 2018142 |

Random forest classification (RFC), and a hybrid model (combination of clinical knowledge and significant variables from RF) |

To predict neonatal surgical site infections (SSI) |

16,842 neonates | EHR | 68% (AUC) |

+ Large dataset + Important neonatal outcome |

|

-Retrospective study -Bias in missing data | ||||||

| Do et al., 202265 | Artificial neural network (ANN), random forest (RF), and support vector machine (SVM) | To predict mortality of very low birth weight infants (VLBWI) | 7472 VLBWI data from Korean neonatal network | EHR |

84.5% (81.5%–87.5%) (ANN-AUC) 82.6% (79.5%–85.8%) (RF-AUC) 63.1% (57.8%–68.3%). SVM-AUC |

+VLBWI mortality prediction using ML methods would produce the same prediction rate as the standard statistical LR approach and may be appropriate for predicting mortality studies utilizing ML confront a high risk of selection bias. |

| - Low prediction rate with ML | ||||||

| Podda et al., 201866 | ANN |

Development of the Preterm Infants Survival Assessment (PISA) predictor |

Between 2008 and 2014, 23747 neonates (<30 weeks gestational age or <1501 g birth weight were recruited Italian Neonatal Network | 12 easily collected perinatal variables |

91.3% (AUC) 77.9% (AUC) 82.8% (AUC) 88.6% (AUC) |

+ NN had a slightly better discrimination than logistic regression |

|

- Like all other model-based methods, is still too imprecise to be used for predicting an individual infant’s outcome - Retrospective design - Lack of variables | ||||||

| Turova et al., 202085 | Random Forest | To predict intraventricular hemorrhage in 23–30 weeks of GA infants | 229 infants |

Clinical variables and cerebral blood flow (extracted from mathematical calculation) were used 10 fold validation |

86%–93% (AUC) Vary on the extracted features in and feature weight in the model |

+ Good accuracy |

|

- Retrospective - Gender distribution was not standardized between the groups - Not corresponding lab value according to the IVH time | ||||||

| Cabrera-Quiros et al., 2021145 |

Logistic regressor, naive Bayes, and nearest mean classifier |

Prediction of late-onset sepsis (starting after the third day of life) in preterm babies based on various patient monitoring data 24 hours before onset |

32 premature infants with sepsis and 32 age-matched control patients |

Heart rate variability, respiration, and body motion, differences between late-onset sepsis and Control group were visible up to 5 hours preceding the cultures, resuscitation, and antibiotics started here (CRASH) point |

Combination of all features showed a mean accuracy 79% and mean precision rate 82% 3 hours before the onset of sepsis Naive Bayes accuracy: 71% Nearest Mean: 70% |

+ Monitoring of vital parameters could be predicted late onset sepsis up to 5 hours. |

|

- Small sample size - Retrospective - Gestational age, postnatal age, sepsis and culture | ||||||

| Reed et al., 2021143 |

Comparison least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and random forest (RF) to expert-opinion driven logistic regression modeling |

Prediction of 30-day unplanned rehospitalization of preterm babies |

5567 live-born babies and 3841 were included to the study Data derived exclusively from The population-based prospective cohort study of French preterm babies, EPIPAGE 2. |

The logistic regression model comprised 10 predictors, selected by expert clinicians, while the LASSO and random forest included 75 predictors |

65% (AUC) RF 59% (AUC) LASSO 57% (AUC) LR |

+ The first comparison of different modeling methods for predicting early rehospitalization + Large cohort with data variation |

|

- No accurate evaluation of rehospitalization causes - Data collection after discharge based on survey filled by mothers - 9% of babies were rehospitalized | ||||||

| Khursid et al., 202170 |

K-nearest neighbor, random forest, artificial neural network, stacking neural network ensemble |

To predict, on days 1, 7, and 14 of admission to neonatal intensive care, the composite outcome of BPD/death prior to discharge. |

<33 weeks GA cohort (n = 9006) And < 29 weeks GA were included |

For each set of models (Days 1, 7, 14), stratified random sampling. 80% of used were training. 20% of used were test set. 10-fold cross validation for test dataset |

81%–86% (AUC) for, 33 weeks 70–79% (AUC) for, 29 weeks |

+ Large dataset |

|

- Not having good performance scores - No data sharing - Not included important predictors (FiO2 and presence of PDA before 7th days) | ||||||

| Moreira et al., 202272 | Logistic regression and Random Forest | To develop an early prediction model of neonatal death on extremely low gestational age(ELGA) infants |

< 28 weeks Swedish Neonatal Quality Registry 2011- May 2021 3752 live born ELGA infants |

Birthweight, Apgar score at 5 min, gestational age were selected as features and new model (BAG) designed to predict mortality |

76.9%(AUC) Validation cohort 68.9% (AUC) |

+ Model development cohort and validation cohort included + BAG model had better AUC than individual birthweight and gestational age model. + Code is available + Online calculator is available |

|

- BAG model does not include clinical variables and clinical practice. Birthweight and gestational age could not be changed. Only Apgar scores could be changed. | ||||||

| Hsu et al., 202071 |

RF KNN ANN XGBoost Elastic-net |

To predict mortality of neonates when they were on mechanical intubation |

1734 neonates 70% training 30% test |

Mortality scores Patient demographics Lab results Blood gas analysis Respirator parameters Cardiac inotrop agents from onset of respiratory failure to 48 hours |

93.9% (AUC) RF has achieved the highest prediction of mortality |

+ Employed several ML and statistics + Explained the feature analysis and importance into analysis |

|

- Two center study - Algorithmic bias - Inability to real time prediction | ||||||

| Stocker et al., 202275 | RF | To predict blood culture test positivity according to the all variables, all variables without biomarkers, only biomarkers, only risk factors, and only clinical signs |

1710 neonates from 17 centers Secondary analysis of NeoPInS data |

Biomarkers(4 variables) Risk factors (4 variables) Clinical signs(6 variables) Other variables(14) All variables (28) They included to RF analysis to predict culture positive early onset sepsis |

Only biomarkers 73.3% (AUC) All variables 83.4% (AUC) Biomarkers are the most important contributor |

+ CRP and WBC are the most important variables in the model + Decrease the overtreatment + Multi-center data |

|

- Overfitting of the model due to the discrepancy with currently known clinical practice - Seemed not evaluated the clinical signs and risk factors which are really important in daily practice | ||||||

| Temple et al., 2016229 | supervised ML and NLP |

To identify patients that will be medically ready for discharge in the subsequent 2–10 days. |

4693 patients (103,206 patient-days178 |

NLP using a bag of words (BOW) surgical diagnoses, pulmonary hypertension, retinopathy of prematurity, and psychosocial issues |

63.3% (AUC) 67.7% (AUC) 75.2% (AUC) 83.7% (AUC) |

+ Could potentially avoid over 900 (0.9%) hospital days |

Table 6.

DL-based studies in neonatology using imaging and non-imaging data for diagnosis.

| Study | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | Type of data (image/non-image) | Performance | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | ||||||

| Hauptmann et al., 2019187 | 3D (2D plus time) CNN architecture |

Ability of CNNs to reconstruct highly accelerated radial real‐time data in patients with congenital heart disease |

250 CHD patients. | Cardiovascular MRI with cine images | +Potential use of a CNN for reconstruction real time radial data | |

| Lei et al., 2022158 | MobileNet-V2 CNN | Detect PDA with AI |

300 patients 461 echocardiograms |

Echocardiography | 88% (AUC) |

+Diagnosis of PDA with AI - Does not detect the position of PDA |

| Ornek et al., 2021189 |

VGG16 (CNN) |

To focus on dedicated regions to monitor the neonates and decides the health status of the neonates (healthy/unhealthy) |

38 neonates | 3800 Neonatal thermograms | 95% (accuracy) | +Known with this study how VGG16 decides on neonatal thermograms |

| -Without clinical explanation | ||||||

| Ervural et al., 2021190 | Data Augmentation and CNN | Detect health status of neonates | 44 neonates |

880 images Neonatal thermograms |

62.2% to 94.5% (accuracy) | +Significant results with data augmentation |

|

-Less clinically applicable -Small dataset | ||||||

| Ervural et al., 2021191 | Deep siamese neural network(D-SNN) | Prediagnosis to experts in disease detection in neonates | 67 neonates, |

1340 images Neonatal thermograms |

99.4% (infection diseases accuracy in 96.4% (oesophageal atresia accuracy), 97.4% (in intestinal atresia-accuracy, 94.02% (necrotising enterocolitis accuracy) |

+D-SNN is effective in the classification of neonatal diseases with limited data |

| -Small sample size | ||||||

| Ceschin et al., 2018188 | 3D CNNs |

Automated classification of brain dysmaturation from neonatal MRI in CHD |

90 term-born neonates with congenital heart disease and 40 term-born healthy controls |

3 T brain MRI | 98.5% (accuracy) |

+ 3D CNN on small sample size, showing excellent performance using cross-validation for assessment of subcortical neonatal brain dysmaturity + Cerebellar dysplasia in CHD patients |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Ding et al., 2020169 | HyperDense-Net and LiviaNET | Neonatal brain segmentation |

40 neonates 24 for training 16 for experiment |

3T Brain MRI T1 and T2 |

94% 95%/ 92% (Dice Score) 90%/90%/88% (Dice Score) |

+Both neural networks can segment neonatal brains, achieving previously reported performance |

| - Small sample size | ||||||

| Liu et al., 202099 |

Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) |

Brain age prediction from MRI | 137 preterm |

1.5-Tesla MRI + Bayley-III Scales of Toddler Development at 3 years |

Show the GCN’s superior prediction accuracy compared to state-of-the-art methods |

+ The first study that uses GCN on brain surface meshes to predict neonatal brain age, to predict individual brain age by incorporating GCN-based DL with surface morphological features |

| -No clinical information | ||||||

| Hyun et al., 2016155 |

NLP and CNN AlexNet and VGG16 |

To achieve neonatal brain ultrasound scans in classifying and/or annotating neonatal using combination of NLP and CNN |

2372 de identified NS report |

11,205 NS head Images |

87% (AUC) |

+ Automated labeling |

| - No clinical variable | ||||||

| Kim et al., 2022157 |

CNN(VGG16) Transfer learning |

To assesses whether a convolutional neural network (CNN) can be trained via transfer learning to accurately diagnose germinal matrix hemorrhage on head ultrasound |

400 head ultrasounds (200 with GMH, 200 without hemorrhage) |

92% (AUC) |

+ First study to evaluate GMH with grade and saliency map + Not confirmed with MRI or labeling by radiologists |

|

|

- Small sample size which limited the training, validation and testing of CNN algorithm | ||||||

| Li et al., 2021159 | ResU-Net |

Diffuse white matter abnormality (DWMA) on VPI’s MR images at term-equivalent age |

98 VPI 28 VPI |

3 Tesla Brain MRI T1 and T2 weighted |

87.7% (Dice Score) 92.3% (accuracy) |

+Developed to segment diffuse white matter abnormality on T2-weighted brain MR images of very preterm infants |

| + 3D ResU-Net model achieved better DWMA segmentation performance than multiple peer deep learning models. | ||||||

|

- Small sample size - Limited clinical information | ||||||

| Greenbury et al., 2021170 |

Agnostic, unsupervised ML Dirichlet Process Gaussian Mixture Model (DPGMM) |

To acquire understanding into nutritional practice, a crucial component of neonatal intensive care |

n = 45,679) over a six-year period UK National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD) |

EHR clustering on time analysis on daily nutritional intakes for extremely preterm infants born <32 weeks gestation |

+Identifying relationships between nutritional practice and exploring associations between nutritional practices and outcomes using two outcomes: discharge weight and BPD +Large national multi center dataset |

|

| - Strong likelihood of multiple interactions between nutritional components could be utilized in records | ||||||

| Ervural et al., 2021192 |

CNN Data augmentation |

To detect respiratory abnormalities of neonates by AI using limited thermal image |

34 neonates 680 images 2060 thermal images (11 testing) 23 training) |

Thermal camera image |

85% (accuracy) |

+ CNN model and data enhancement methods were used to determine respiratory system anomalies in neonates. |

|

-Small sample size -There is no follow-up and no clinical information | ||||||

| Wang et al., 2018174 | DCNN | To classify automatically and grade a retinal hemorrhage |

3770 newborns with retinal hemorrhage of different severity (grade 1, 2 and 3) and normal controls from a large cross-sectional investigation in China. |

48,996 digital fundus images |

97.85% to 99.96% (accuracy) 98.9%–100% AUC) |

+The first study to show that a DCNN can detect and grade neonatal retinal hemorrhage at high performance levels |

| Brown et al., 2018171 | DCNN |

To develop and test an algorithm based on DL to automatically diagnose plus disease from retinal photographs |

5511 retinal photographs (trained) independent set of 100 images |

Retinal images |

94% (AUC) 98% (AUC) |

+ Outperforming 6 of 8 ROP expert + Completely automated algorithm detected plus disease in ROP with the same or greater accuracy as human doctors + Disease detection, monitoring, and prognosis in ROP-prone neonates |

|

-No clinical information and no clinical variables | ||||||

| Wang et al., 2018179 |

DNN (Id-Net Gr-Net) |

To automatically develop identification and grading system from retinal fundus images for ROP |

349 cases for identification 222 cases for grading |

Retinal fundus images |

Id-Net: 96.64% (sensitivity) 99.33% (specificity) 99.49% (AUC) Gr-Net: 88.46% (sensitivity) 92.31% (specificity) 95.08% (AUC) |

+ Large dataset including training, testing and, comparison with human experts. + Good example of human in the loop models + Code is available |

|

- No clinical grading included - Dataset is not available | ||||||

| Taylor et al., 2019172 |

DCNN Quantitative score |

To describe a quantitative ROP severity score derived using a DL algorithm designed to evaluate plus disease and to assess its utility for objectively monitoring ROP progression |

Retinal images | 871 premature infants | + ROP vascular severity score is related to disease category at a specific period and clinical course of ROP in preterm | |

|

-Retrospective cohort study -No follow-up for patients -Low generalizability | ||||||

| Campbell et al., 2021173 |

DL(U-Net) Tensor Flow ROP Severity Score(1-9) |

Evaluate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence (AI)-based screening in an Indian ROP telemedicine program and whether differences in ROP severity between neonatal care units (NCUs) identified by using AI are related to differences in oxygen-titrating capability |

4175 unique images from 1253 eye examinations retinopathy of Prematurity Eradication Save Our Sight ROP telemedicine program |

363 infants from 32 NCUs | 98% (AUC) |

+ Integration of AI into ROP screening programs may lead to improved access to care for secondary prevention of ROP and may facilitate assessment of disease epidemiology and NCU resources |

| Xu et al., 2021193 |

-Wireless sensors -Pediatric focused algorithm -ML and data analytics -cloud based dashboards |

To enhance monitoring with wireless sensors |

By the middle of 2021, there were 15,000 pregnant women and up to 500 newborns. 1000 neonates |

+ Future predictive algorithms of clinical outcomes for neonates +As small as 4.4 cm 2.4 cm and as thin as 1 mm in totally wirelessly powered versions, these devices provide continuous monitoring in this sensitive group |

||

| Werth et al., 2019186 |

Sequential CNN ResNet |

Automated sleep state requirement without EEG monitoring | 34 stable preterm infants |

Vital signs were recorded ECG R peaks were analyzed |

Kappa of 0.43 ± 0.08 Kappa of 0.44 ± 0.01 Kappa of 0.33 ± 0.04 |

+ Non-invasive sleep monitoring from ECG signals |

|

- Retrospective study - Video were not used in analysis | ||||||

| Ansari et al., 2022185 | A Deep Shared Multi-Scale Inception Network | Automated sleep detection with limited EEG Channels | 26 preterm infants | 96 longitudinal EEG recordings |

Kappa 0.77 ± 0.01 (with 8-channel EEG) and 0.75 ± 0.01 (with a single bipolar channel EEG |

+ The first study using Inception-based networks for EEG analysis that utilizes filter sharing to improve efficiency and trainability. + Even a single EEG channel making it more practical |

|

- Small sample size - Retrospective - No clinical information | ||||||

| Ansari et al., 2018184 | CNN |

To discriminate quiet sleep from nonquiet sleep in preterm infants (without human labeling and annotation) |

26 preterm infants |

54 EEG recordings for training 43 EEG recording for the test (at 9 and 24 months corrected age, a normal neurodevelopmental outcome score (Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II, mental and motor score >85)) |

92% (AUC) 98% (AUC) |

+ CNN is a viable and rapid method for classifying neonatal sleep phases in preterm babies + Clinical information |

|

- Retrospective - The paucity of EEG recordings below 30 weeks and beyond 38 weeks postmenstrual age - Lack of interpretability of the features | ||||||

| Moeskops et al., 2017199 |

CNN for MRI segmentation230 SVM for neurocognitive outcome prediction |

To predict cognitive and motor outcome at 2–3 years of preterm infants from MRI at 30th and 40th weeks of PMA |

30 weeks (n = 86) 40 weeks (n = 153) |

3 T Brain MRI at 30th and 40th weeks of PMA BSID-III at average age of 29 months (26–35) |

Cognitive Outcome (BSID<85) 78% (AUC) 30 weeks of PMA 70% (AUC) 40 weeks of PMA Motor Outcome BSID<85 80% (AUC) 30 weeks of PMA 71% (AUC) 40 weeks of PMA |

+ Brain MRI can predict cognitive and motor outcome + Segmentations, quantitative descriptors, classification were performed and + Volumes, measures of cortical morphology were included as a predictor |

|

- Small sample size -Retrospective design |

Table 7.

DL-based studies in neonatology using imaging and non-imaging for prediction.

| Study | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | #Non-Image data | #-Image data | AUC/accuracy | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | |||||||

| Saha et al., 2020176 | CNN |

To predict abnormal motor outcome at 2 years from early brain diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquired between 29 and 35 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) |

77 very preterm infants (born <31 weeks gestational age (GA)) |

At 2 years CA, infants were assessed using the Neuro-Sensory Motor Developmental Assessment (NSMDA) |

3 T brain diffusion MRI |

72% (AUC) |

+ Neuromotor outcome can be predicted directly from very early brain diffusion MRI (scanned at ~30 weeks PMA), without the requirement of constructing brain connectivity networks, manual scoring, or pre-defined feature extraction + Cerebellum and occipital and frontal lobes were related motor outcome |

| -Small sample size | |||||||

| Shabanian et al., 2019175 | Based on MRIs, the 3D CNN algorithm can promptly and accurately diagnose neurodevelopmental age |

Neurodevelopmental age estimation |

112 individuals | 1.5T MRI from NIMH Data Achieve |

95% (accuracy) 98.4% (accuracy) |

+ 3D CNNs can be used to accurately estimate neurodevelopmental age in infants based on brain MRIs |

|

|

- Restricted clinical information - No clinical variable - Small sample size which limited the training, validation and testing of CNN algorithm | |||||||

| He et al., 2020177 | Supervised and unsupervised learning | In terms of predicting abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes in extremely preterm newborns, multi-stage DTL (deep transfer learning) outperforms single-stage DTL. |

33 preterm infants Retrained in 291 neonates |

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III at 2 years corrected age |

3 Tesla Brain MRI T1 and T2 weighted |

86% (cognitive deficit-AUC) 66% (language deficit-AUC) 84% (motor deficit-AUC) |

+ Risk stratification at term-equivalent age for early detection of long-term neurodevelopmental abnormalities and directed earlier therapies to enhance clinical outcomes in extremely preterm infants |

| - The investigation of the brain’s functional connectome was based on an anatomical/structural atlas as opposed to a functional brain parcellated atlas. |

ML applications in neonatal mortality

Neonatal mortality is a major factor in child mortality. Neonatal fatalities account for 47 percent of all mortality in children under the age of five, according to the World Health Organization60. It is, therefore, a priority to minimize worldwide infant mortality by 203061.

ML investigated infant mortality, its reasons, and its mortality prediction62–68. In a recent review, 1.26 million infants born from 22 weeks to 40 weeks of gestational age were enrolled67. Predictions were made as early as 5 min of life and as late as 7 days. An average of four models per investigation were neural networks, random forests, and logistic regression (58.3%)67. Two studies (18.2%) completed external validation, although five (45.5%) published calibration plots67. Eight studies reported AUC, and five supplied sensitivity and specificity67. The AUC was 58.3–97.0%67. Sensitivities averaged 63 to 80%, and specificities 78 to 98%67. Linear regression analysis was the best overall model despite having 17 features67. This analysis highlighted the most prevalent AI neonatal mortality measures and predictions. Despite the advancement in neonatal care, it is crucial that preterm infants remain highly susceptible to mortality due to immaturity of organ systems and increased susceptibility to early and late sepsis69. Addressing these permanent risks necessitates the utilization of ML to predict mortality63–66,68,70. Early studies employed ANN and fuzzy linguistic models and achieved an AUC of 85–95% and accuracy of 90%62,68. New studies in a large preterm populations and extremely low birthweight infants found an AUC of 68.9–93.3%65,71. There are some shortcomings in these studies; for example, none of them used vital parameters to represent dynamic changes, and hence, there was no improvement in clinical practice in neonatology. Unsurprisingly, gestational age, birthweight, and APGAR scores were shown as the most important variables in the models64,72. Future research is suggested to focus on external evaluation, calibration, and implementation of healthcare applications67.

Neonatal sepsis, which includes both early onset sepsis and late onset sepsis, is a significant factor contributing to neonatal mortality and morbidity73. Neonatal sepsis diagnosis and antibiotic initiation present considerable obstacles in the field of neonatal care, underscoring the importance of implementing comprehensive interventions to alleviate their profound negative consequences. The studies have predicted early sepsis from heart rate variability with an accuracy of 64–94%74. Another secondary analysis of multicenter data revealed that clinical biomarkers weighed the ML decision by integrating all clinical and lab variables and achieved an AUC of 73–83%75.

ML applications in neurodevelopmental outcome

Recent advancements in neonatal healthcare have resulted in a decrease in the incidence of severe prenatal brain injury and an increase in the survival rates of preterm babies76. However, even though routine radiological imaging does not reveal any signs of brain damage, this population is nonetheless at significant risk of having a negative outcome in terms of neurodevelopment77–80. It is essential to discover early indicators of abnormalities in brain development that might serve as a guide for the treatment of preterm children at a greater risk of having negative neurodevelopmental consequences81,82.

The most common reason for neurodevelopmental impairment is intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) in preterm infants83. Two studies predicted IVH in preterm infants. Both studies have not deployed the ultrasound images in their analysis, they only predicted IVH according to the clinical variables84,85.

Morphological studies have demonstrated that preterm birth is linked to smaller brain volume, cortical folding, axonal integrity, and microstructural connectivity86,87. Studies concentrating on functional markers of brain maturation, such as those derived from resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) analyses of blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) fluctuations, have revealed further impacts of prematurity on the developing connectome, ranging from decreased network-specific connectivity82,88,89. Many studies investigated brain connectivity in preterm infants88,90–92 and brain structural analysis in neonates93 and neonatal brain segmentation94 with the help of ML methods. Similarly, one of the most important outcomes of neurodevelopment at 2-year-old-age is neurocognitive evaluations. The studies evaluated the morphological changes in the brain in relation to neurocognitive outcome95–97 and brain age prediction98,99. It has been found that near-term regional white matter (WM) microstructure on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) predicted neurodevelopment in preterm infants using exhaustive feature selection with cross-validation96 and multivariate models of near-term structural MRI and WM microstructure on DTI might help identify preterm infants at risk for language impairment and guide early intervention95,97 (Table 4). One of the studies that evaluated the effects of PPAR gene activity on brain development with ML methods100 revealed a strong association between abnormal brain connectivity and implicating PPAR gene signaling in abnormal white matter development. Inhibited brain growth in individuals exposed to early extrauterine stress is controlled by genetic variables, and PPARG signaling has a formerly unknown role in cerebral development100 (Table 2).

Table 4.

ML based (non-DL) studies in neonatology using imaging data for prediction.

| Study | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | Type of data | Performance | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | ||||||

| Vassar et al., 202095 |

Multivariate models with leave-one-out cross-validation and exhaustive feature selection |

Very premature infants' structural brain MRI and white matter microstructure as evaluated by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in the near term and their impact on early language development | 102 infants |

Brain MRI and DTI + (Bayley Scales of Infant- Toddler Development-III at 18 to 22 months) |

50.2% (language composite score -AUC) 61.7% (expressive language subscore-AUC) 32.2% (receptive language subscore-AUC) |

+ Preterm babies at risk for language impairment may be identified using multivariate models of near-term structural MRI and white matter microstructure on DTI, allowing for early intervention |

|

- Demographic data is not included - Cross validation? - Small sample size | ||||||

| Schadl et al., 201896 |

-Linear models with exhaustive feature selection and leave-one-out cross-validation |

To predict neurodevelopment in preterm children in near term MRI and DTI |

66 preterm infants |

Brain MRI and DTI 51 WM regions (48 bilateral regions, 3 regions of corpus callosum) Bayley Scales of Infant-Toddler Development, 3rd-edition (BSID-III) at 18–22 months. |

100% (AUC, cognitive impairment) 91% (AUC, motor impairment |

- Using structural brain MRI findings of WMA score, lower accuracy - Small cohort - DTI has better implementation and interpretation |

| Wee et al., 201797 | SVM and canonical correlation analysis (CCA) |

To examine heterogeneity of neonatal brain network and its prediction to child behaviors at 24 and 48 months of age |

120 neonates |

1.5-Tesla DW MRI Scans Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography + Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) at 24 and 48 months of age. |

89.4% (accuracy) |

+ Neural organization established during fetal development could predict individual differences in early childhood behavioral and emotional problems |

| - Small sample size |

Alternative to morphological studies, neuromonitorization is shown to be an important tool for which ML methods have been frequently employed, for example, in automatic seizure detection from video EEG101–103 and EEG biosignals in infants and neonates with HIE104–108. The detection of artifacts109,110, sleep states102, rhythmic patterns111, burst suppression in extremely preterm infants112,113 from EEG records were studied with ML methods. EEG records are often used for HIE grading114 too. It has been shown in those studies that EEG recordings of different neonate datasets found an AUC of 89% to 96%104,105,115, accuracy 78–87%114,116 regarding seizure detection with different ML methods (Table 3).

Table 3.

ML based (non-DL) studies in neonatology using non-imaging data for diagnosis.

| Study | Approach | Purpose | Dataset | Type of data | Performance | Pros(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons(-) | ||||||

| Reed et al., 1996135 | Recognition-based reasoning | Diagnosis of congenital heart defects | 53 patients |

Patient history, physical exam, blood tests, cardiac auscultation, X-ray, and EKG data |

+ Useful in multiple defects | |

| - Small sample size-Not real AI - implementation | ||||||

| Aucouturier et al., 2011148 |

Hidden Markov model architecture (SVM, GMM) |

To identify expiratory and inspiration phases from the audio recording of human baby cries |

14 infants, spanning four vocalization contexts in their first 12 months | Voice record- |

86%–95% (accuracy) |

+ Quantify expiration duration, count the crying rate, and other time-related characteristics of baby crying for screening, diagnosis, and research purposes over large populations of infants + Preliminary result |

|

- More data needed - No clinical explanation - Small sample size - Required preprocessing | ||||||

| Cano Ortiz et al., 2004149 |

Artificial neural networks (ANN) |

To detect CNS diseases in infant cry |

35 neonates, nineteen healthy cases and sixteen sick neonates |

Voice record (187 patterns) |

85% (accuracy) |

+ Preliminary result |

| - More data needed for correct classification for | ||||||

| Hsu et al., 2010151 |

Support Vector Machine (SVM) Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) |

To diagnose Methylmalonic Acidemia (MMA) |

360 newborn samples |

Metabolic substances data collected from tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) |

96.8% (accuracy) |

+Better sensitivity than classical screening methods |

|

-Small sample size - SVM pilot stage education not integrated | ||||||

| Baumgartner et al., 2004152 |

Logistic regression analysis (LRA) Support vector machines (SVM) Artificial neural networks (ANN) Decision trees (DT) k-nearest neighbor classifier (k-NN) |

Focusing on phenylketonuria (PKU), medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD |

During the Bavarian newborn screening program all newborns |

Metabolic substances data collected from tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) |

99.5% (accuracy) |

+ ML techniques, LRA (as discussed above), SVM and ANN, delivered results of high predictive power when running on full as well as on reduced feature dimensionality. |

|

- Lacking direct interpretation of the knowledge representation | ||||||

| Chen et al., 2013153 | Support vector machine (SVM) |

To diagnose phenylketonuria (PKU), hypermethioninemia, and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA-carboxylase (3-MCC) deficiency |

347,312 infants (220 metabolic disease suspect) |

Newborn dried blood samples |

99.9% (accuracy) 99.9% (accuracy) 99.9% (accuracy) |

+ Reduced false positive cases |

|

- The feature selection strategies did not include the total features for establishing either the manifested features or total combinations | ||||||

| Temko et al., 2011105 |

Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation method. |

To measure system performance for the task of neonatal seizure detection using EEG |

17 newborns system is validated on a large clinical dataset of 267 h All seizures were annotated independently by 2 experienced neonatal electroencephalographers using video EEG |

EEG data | 89% (AUC) |