Abstract

Nimbolide, a tetranortriterpenoid (limonoid) compound isolated from the leaves of Azadirachta indica, was screened both in vitro and in silico for its antimicrobial activity against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, Macrophomina phaseolina, Pythium aphanidermatum, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, and insecticidal activity against Plutella xylostella. Nimbolide exhibited a concentration-dependent, broad spectrum of antimicrobial and insecticidal activity. P. aphanidermatum (82.77%) was more highly inhibited than F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (64.46%) and M. phaseolina (43.33%). The bacterium X. oryzae pv. oryzae forms an inhibition zone of about 20.20 mm, and P. xylostella showed about 66.66% mortality against nimbolide. The affinity of nimbolide for different protein targets in bacteria, fungi, and insects was validated by in silico approaches. The 3D structure of chosen protein molecules was built by homology modelling in the SWISS-MODEL server, and molecular docking was performed with the SwissDock server. Docking of homology-modelled protein structures shows most of the chosen target proteins have a higher affinity for the furan ring of nimbolide. Additionally, the stability of the best-docked protein–ligand complex was confirmed using molecular dynamic simulation. Thus, the present in vitro and in silico studies confirm the bioactivity of nimbolide and provide a strong basis for the formulation of nimbolide-based biological pesticides.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12088-023-01104-6.

Keywords: Azadirachta indica, Nimbolide, In vitro, In silico molecular docking, Simulation, SwissDock

Introduction

Synthetic pesticides with broad-spectrum action are used in agriculture to protect plants from insects, pests, and weeds and to increase crop yield [1, 2]. The ceaseless use of pesticides had a devastating effect on soil health, the environment, human wellbeing [3], and the ecosystem [4, 5]. In Integrated Pest Management (IPM), botanical pesticides (botanicals) obtained from plants are used as an alternative to synthetic pesticides [6]. These are naturally present as secondary metabolites (phytochemicals), which have anti-feeding, anti-microbial, insecticidal, and repellent activity [7]. The advantages of botanicals compared to synthetic pesticides includes less bioaccumulation, the absence of residue in ecosystems, their selectiveness against pests, and their very low toxicity to humans. More than 250 natural bioactive compounds, including diterpenoids, triterpenoids, tetranortriterpenoids, steroids, flavonoids, coumarins, hydrocarbons, fatty acids, etc., have been isolated from different parts of the neem tree [8–10]. The tree extract of neem contains a large number of active constituents such as azadirachtin, nimbin, meliantriol, desacetylnimbin, nimbidin, salannin, nimbolide, and desacetylsalannin. Nimbolide is one of the most important limonoid compounds present in the leaves of A. indica. Nimbolide (5,7,4′-trihydroxy-3′,5′-diprenylflavanone) is characterised by a classical limonoid skeleton comprising of an α, β unsaturated ketone and a δ-lactone ring [11]. Nimbolide has not been fully explored for its antimicrobial and insecticidal activity against plant pathogens and insect pests. Hence, in this study, globally important plant pathogens and insect pests were chosen to elucidate the antimicrobial and insecticidal properties of nimbolide.

To understand the mode of action of nimbolide, molecular docking was carried out to predict protein – ligand binding at molecular level. Since, in silico studies have not been carried out for nimbolide against agriculturally significant microbial pathogens and insect pests, this present work aims to explore the mode of action of nimbolide through in silico investigation against Plutella xylostella, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, Pythium aphanidermatum, and Macrophomina phaseolina that helps to develop an eco-friendly biological pesticide by assessing the in vitro bioactivity of nimbolide and decipher the mode of action through molecular docking and simulation approaches.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Test Organisms

Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves were collected from healthy trees at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore (11°00′ 41.8″ N 76°56′ 11.5″ E). The leaves were shade-dried for 7 days, ground to a fine powder, and stored for further use. Fungal pathogens, namely Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (MK981549), Macrophomina phaseolina (MN636186), Pythium aphanidermatum (MK841487), and bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (MZ825435), were chosen for antimicrobial study, and the isolated cultures of fungus and bacterium were obtained from the Department of Plant Biotechnology, Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore. Fungal cultures were maintained in Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium and bacterium in Luria Bertani (LB) media. The Diamond Back Moth (DBM), Plutella xylostella cultures were reared in the Insect Bioassay Laboratory and used for in vitro insecticidal studies. The entire research work was carried out at the Department of Plant Biotechnology, Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore.

Nimbolide Isolation

Neem leaf powder (600 g) was soaked in 1800 mL of acetone for 3 days, then it was filtered and concentrated in vacuo at 40 °C to obtain dark green oil. This dark green oil was washed with hot hexane (150 ml) for about 8–10 times until the hexane wash became colourless. Then 150 mL of methanol was added, and the residue was completely dissolved. It is then kept at 40 °C for 24 h. The dark green powder formed after refrigeration was filtered and washed with cold methanol to form a green colour powder. This green powder was again washed with hexane (25 mL) and cold methanol (25 mL) to obtain a pale green powder (1.4 g). This pale green powder was crystallised using hexane and dichloromethane (1:1) to obtain a white colour powder which was then identified by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy.

In Vitro Antimicrobial and Insecticidal Studies

Neem Leaf Extract Sample Preparation

Neem leaf powder (100 g) was soaked in 300 mL of methanol for 3 days. Then it was filtered through a column of celite and the filtered methanol was evaporated in vacuo. The dark green residue obtained was diluted with methanol to give different concentrations of 250 ppm, 500 ppm, 750 ppm and 1000 ppm.

Nimbolide Sample Preparation

Nimbolide stock was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of purified nimbolide in 10 mL of methanol. From the stock solution, the working concentration was diluted with methanol to give 250 ppm, 500 ppm, 750 ppm and 1000 ppm concentrations.

Agar Well Diffusion method

The antibacterial and antifungal potentials of nimbolide against plant pathogens were assessed by agar-well diffusion method [12, 13]. For the antibacterial assay, X. oryzae pv. oryzae was grown in LB broth at 28 °C at 180 rpm in an incubator cum shaker for 12 h. One mL of bacterial culture containing 106 CFU mL−1 was seeded with 25 mL of LB media in a Petri plate and was uniformly spread by rotating both clockwise and anti-clockwise. Wells of 4 mm diameter were formed by using a cork borer at the four corners of the petri plate. Fifty µL of different concentrations, viz. 250 ppm, 500 ppm, 750 ppm, and 1000 ppm, of filter-sterilized neem leaf extract and isolated nimbolide were added separately into different plates in three replicates. Each replicate consisted of 10 Petri plates. It was incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h. Later, the zone of inhibition was measured (mm).

Antifungal assays were performed for F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc), P. aphanidermatum and M. phaseolina against nimbolide. For the antifungal assay, 4 mm-diameter wells were formed by using a cork borer at the four corners of a Petri plate containing PDA media. Fifty microlitre of different concentrations, viz. 250 ppm, 500 ppm, 750 ppm, and 1000 ppm, of filter-sterilised neem leaf extract and nimbolide were added separately into different plates in three replicates. Each replicate consisted of 10 Petri plates. Actively growing fungal disc of 4 mm diameter of respective pathogens were placed at the centre of PDA medium and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 5 days. After incubation, mycelial growth was measured (cm). In both assays, methanol without any of the compounds was used as an untreated control. The percent inhibition of mycelial growth over untreated control was calculated by the formula

Antifeedant Activity

The antifeedant activities of neem leaf extract and nimbolide were tested against P. xylostella at different concentrations (250 ppm, 500 ppm, 750 ppm, and 1000 ppm) by the leaf disc method [14]. Fresh and tender leaf discs (2 cm in diameter) of cauliflower were treated and placed in a Petri dish (90 × 15 mm) containing one layer of moist Whatman filter paper. Different concentrations of compounds (10 µL per side) were coated over the leaf disc and air-dried. The leaf discs treated with methanol and water served as a negative control. Thirty neonate larvae were used in each treatment, with three replications. The experiment was performed in a controlled environment of 26 ± 1 °C at 60% RH for 6 days. The larval mortality and development were recorded up to 6 days, and the percent larval mortality was assessed.

In-Silico Antimicrobial and Insecticidal Studies

Target selection

A small molecular nimbolide (Molecular formula: C27H30O7; Molecular weight: 466.5) from A. indica was docked to different protein targets of fungi (F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense, P. aphanidermatum, and M. phaseolina), bacteria (X. oryzae pv. oryzae), and insect (P. xylostella) to assess the probable inhibitory role. Protein targets were selected based on the literature search. The chosen protein targets are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Protein targets of fungus, bacteria and insect with its UniProt ID, Function, Protein length, QMEAN Score, Binding energy (kcal/mol), Full Fitness value (kcal/mol), hydrogen bond residues and their 2D, 3D Docking structures

| S. no. | Protein target (Uniprot ID) | Biological process | Protein length | QMEAN Score (Template PDB ID) | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Full Fitness value (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding residues | 2-D Docking structure | 3-D Docking structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fungal protein target: Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense | |||||||||

| 1 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein beta subunit (Q96VA6) [15] | Cellular function and metabolism (Soundarajan et al. 2011) | 359 | −5.02 (7AD3) | −7.23 | −1606.09 | LEU 60 |  |

|

| 2 |

GTP-binding protein RHO1 (N4UV59) [16] |

Morphogenesis, cell wall biosynthesis and virulence [17] |

314 | −2.94 (1WAZ) | −7.14 | −954.16 | LEU 118 |  |

|

| Pythium aphanidermatum | |||||||||

| 1 |

Necrosis- and ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1)-like proteins (NLPs)# |

Virulence and spread of disease [19] | 234 | 3GNU | −6.55 | −644.40 | Van der waals interaction |  |

|

| 2 |

Succinate dehydrogenase (F8T2Z6) [20] |

Essential component of cellular respiratory chain acid Krebs cycle [20] | 226 | −4.04 (6YMX) | −5.82 | −373.37 |

ASN 1 ARG 88 |

|

|

| 3 |

Cellulose synthase (H6D5B6) [21] |

Cell wall formation [21] | 1,137 | −7.26 (5EJ1) | −6.31 | −2712.12 | GLU 864 |  |

|

| Macrophomina phaseolina | |||||||||

| 1 |

Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein (K2S6W8) [22] |

Cell wall formation [22] | 346 | −5.15 (2AHN) | −7.84 | −1100.59 | PHE 228 |  |

|

| 2 |

Lectin (K2RG75) [23] |

Cell–cell contact [24] | 603 | −4.73 (6F9A) | −8.00 | −1056.97 | Van der waals interaction |  |

|

|

Bacteria protein targets Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | |||||||||

| 1 |

Peptide deformylase (A0A0M1KN68) [25] |

Catalyses the removal of the N-formyl group from N-terminal methionine following translation and helps in bacterial growth [26] | 170 | −2.38 (1LME) | −7.34 | −890.69 |

GLY 99 TYR 101 |

|

|

| 2 |

Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH]# |

Virulence protein involved in fatty acid synthesis [28] | 402 | 3S8M | −6.64 | −1378.35 | CYS 12 |  |

|

|

Insect target Plutella xylostella | |||||||||

| 1 |

Acetylcholinesterase (Ache) (A0A1L8D6U8) [29] |

Important enzyme in central nervous system of insect, playing a role in cholinergic synapses. [30] | 806 | −1.17 (5YDH) | −7.80 | −3537.46 | TRP 322 |  |

|

| 2 |

Ryanodine receptor# (G8EME3) [31] |

Calcium signaling and central role in excitation–contraction coupling of muscle cells [32] | 5117 | 5Y9V | −7.58 | −2139.84 | VAL 73 |  |

|

#Protein target with 3D PDB structure

Molecular Modelling and Docking

Among the chosen eleven protein targets, necrosis- and ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1)-like proteins (NLPs) of P. aphanidermatum, enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH] of X. oryzae, and ryanodine receptor of P. xylostella were found to have three-dimensional (3D) structures, and they were retrieved from the RCBS PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) [33]. For other targets, protein sequence retrieved from the UniprotKB database was used for homology modelling of 3D structure using the SWISS-MODEL server [34]. A template with high coverage and identity (Minimum 30 percent) and one that comes under the same taxonomy as the query protein was chosen for modelling the 3D structure. The generated three-dimensional structure of the protein targets was validated by the Ramachandran plot and Qmean Score. Active sites were identified by using the CASTp 3.0 server (Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of Proteins) [35]. Information regarding the protein target, Uniprot ID, function, Protein length, QMEAN Score, and template PDBID is listed in Table 1. Prior to docking, hydrogen bonds were added and energy was minimised using the Swiss-PDB Viewer tool. Structure of Nimbolide with CID: 100,017 was retrieved from the Pubchem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) database. Docking of Nimbolide against protein targets was performed using the SwissDock server (http://www.swissdock.ch/) [36]. BIOVIA Discovery Studio client visualizer 2020 (Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Modelling Environment, Release 2017, San Diego: Dassault Systemes, 2016) was used for visualising and interpreting compound interactions in the active site of amino acid residues.

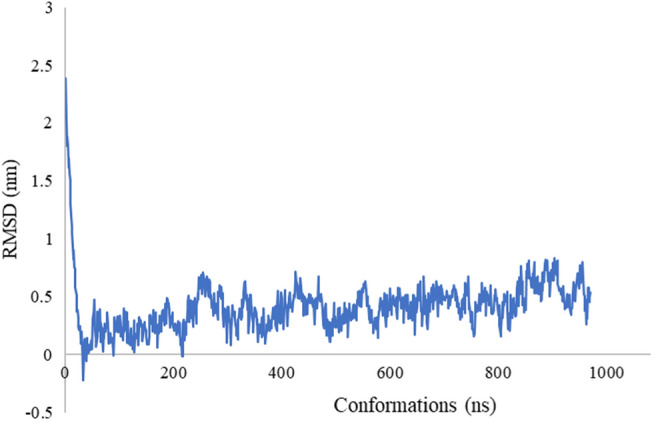

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

From the docking results, the protein–ligand complex with high binding energy was subjected to MD simulations. MD simulations were carried out with Dassault System BIOVIA, Discovery Studio software. The process was done in five steps using standard dynamics cascade module, the system was stimulated with CHARMm force field, starting with two steps of 500-cycle energy minimization of a complex with the steepest descent and conjugate gradient. For the simulation, the protein–ligand systems were solvated in an orthorhombic box with a minimum distance of 7 Å from the periodic boundary by adding sufficient water molecules to enable the protein to naturally interact with the solvent. To prevent the surface artefacts, the protein was solvated in a water box so that the simulation can run with periodic boundary conditions [37]. The energy minimization step was followed by heating, equilibration, and production. The whole system was heated from an initial temperature of 50 K to 300 K in 20 picoseconds (ps) without restraint. The equilibration was run in 300 K for 20 ps without restraint. The production was run in 300 K for a time of 20 ns with typed NPT. Root-Mean-Square-Deviation (RMSD) and the total energy of the protein–ligand complex structure were computed to examine the stability and flexibility during 20 nano second (ns) of simulation.

Statistical Analysis

The bioassay was performed in a completely randomized block design with three replications. The results were shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The effect of different treatments on the growth of pathogens and mortality of insects was analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) was performed at a 5% significance level to compare the treatment means in the SPSS statistical package.

Results and Discussion

Around 1.4 g of nimbolide was isolated by the acetone extraction method from A. indica leaves. The isolated nimbolide was confirmed by 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy, and it matched the spectral details reported earlier [38, 39].

Nimbolide: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH: 7.32 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.93 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.53 (m, 1H), 4.62 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, 12 0.4 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.54 (s, 1H), 3.25 (dd, J = 5.2 Hz, 16 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.39 (dd, J = 5.6 Hz, 16 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (dd, J = 6.8 Hz, 12.4 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (m, 1H), 1.70 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δC: 200.6 (CO), 174.8 (COO), 173.0 (COO), 149.6 (CH), 144.8 (C), 143.2 (CH), 138.9 (CH), 136.4 (C), 131.0 (CH), 126.5 (C), 110.3 (CH), 88.5 (CH), 82.9 (CH), 73.4 (CH), 51.8 (OCH3), 50.3 (C), 49.5 (CH), 47.7 (CH), 45.3 (C), 43.7 (C), 41.2 (CH2), 41.1 (CH), 32.1 (CH2), 18.5 (CH3), 17.2 (CH3), 15.2 (CH3), 12.9 (CH3).

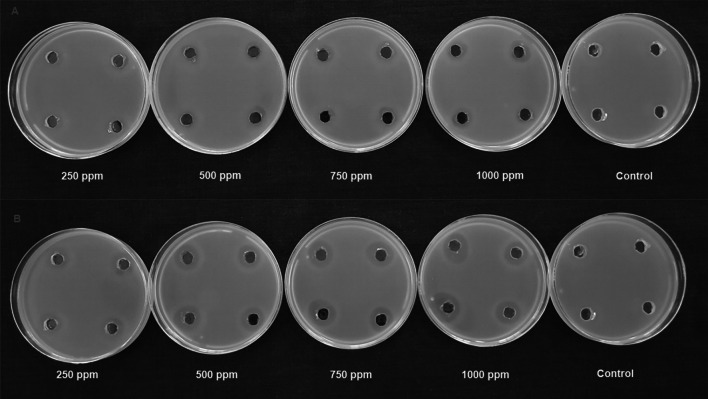

Antimicrobial Activity of Nimbolide

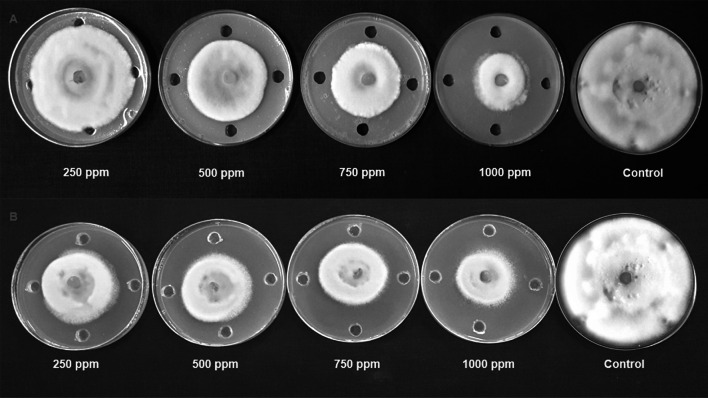

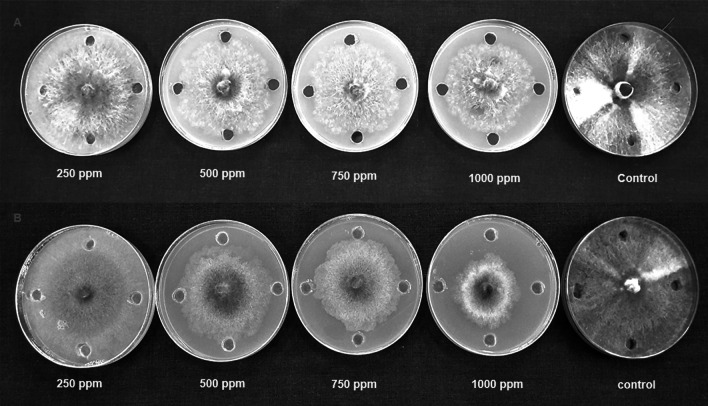

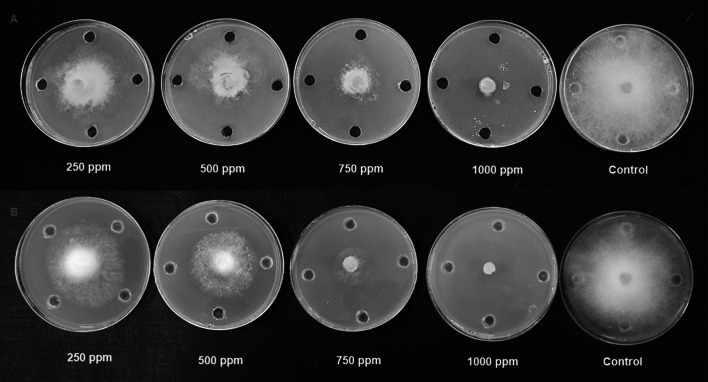

The antibacterial activity of neem leaf extract and nimbolide against X. oryzae pv. oryzae revealed the presence of a clear zone of inhibition around the wells at different concentrations. The maximum inhibition of 13.10 ± 0.30 mm was observed at 1000 ppm with neem leaf extract (Table 2). Besides the antibacterial assay with nimbolide at 1000 ppm, the maximum inhibition was 20.2 ± 0.22 mm against X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Fig. 1). Comparative analysis of the dose-dependent assay for antibacterial activity between neem leaf extract and nimbolide indicated that the antibacterial efficacy was maximum in nimbolide compared to neem leaf extract at 1000 ppm concentration, irrespective of other doses tested. Further, the antifungal activity of neem leaf extract and nimbolide indicated that the pathogens F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense, M. phaseolina, and P. aphanidermatum were inhibited at all the tested doses, irrespective of neem leaf extract and nimbolide (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Neem leaf extract exhibited 38.98% inhibition of mycelial growth of M. phaseolina over untreated control at 1000 ppm, whereas in nimbolide, mycelial growth was inhibited up to 43.33%. Furthermore, the antifungal assay at 1000 ppm concentration of neem leaf extract and nimbolide against F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense indicated that nimbolide was superior in suppressing the mycelial growth of Foc (64.46%) compared to neem leaf extract. Similarly, nimbolide at 1000 ppm inhibited the mycelial growth of P. aphanidermatum by up to 82.77% over the untreated control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of neem leaf extract and nimbolide against bacterial pathogen X. oryzae pv. oryzae, Fungal pathogens F. oxysporum, M. phaseolina, P. aphanidermatum and neonates of P. xylostella

| Compound | Concentration of biomolecules (ppm) | Zone of Inhibition (mm) | Per cent inhibition over control (%) | Larval mortality (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense | Macrophomina phaseolina | Pythium aphanidermatum | Plutella xylostella | ||

| Neem leaf extract | 250 | 10.60 ± 0.50e | 33.14 ± 0.63e | 24.90 ± 0.45e | 43.79 ± 0.31 cd | 40.00 ± 0.00 (39.23)de |

| 500 | 11.50 ± 0.33e | 44.26 ± 0.34 cd | 29.62 ± 0.43cde | 56.38 ± 0.72bcd | 46.67 ± 5.77 (43.07)cd | |

| 750 | 12.60 ± 0.08d | 50.46 ± 0.20bc | 33.51 ± 0.09bcd | 70.27 ± 0.76ab | 50.00 ± 0.00 (45.00)bcd | |

| 1000 | 13.10 ± 0.30d | 55.46 ± 0.41b | 38.98 ± 0.10ab | 79.25 ± 0.25ab | 60.00 ± 10.00 (50.85)ab | |

| Nimbolide | 250 | 16.10 ± 0.40c | 41.85 ± 0.45d | 28.88 ± 0.19de | 45.00 ± 0.81d | 33.33 ± 5.77 (35.21)e |

| 500 | 16.30 ± 0.36c | 48.61 ± 0.13bcd | 31.57 ± 0.30 cd | 59.44 ± 0.40bc | 43.33 ± 5.77 (41.15)de | |

| 750 | 18.70 ± 0.33b | 55.46 ± 0.33b | 35.83 ± 0.21bc | 76.67 ± 0.85ab | 56.66 ± 5.77 (48.84)abc | |

| 1000 | 20.20 ± 0.22a | 64.25 ± 0.22a | 43.33 ± 0.49a | 82.78 ± 0.86a | 66.66 ± 11.54 (54.98)a | |

| Methanol* | 0.00f | 0.00f | 0.00f | 0.00e | 6.66 ± 2.89 (14.75)f | |

| Water* | 0.00f | 0.00f | 0.00f | 0.00e | 6.66 ± 2.89 (14.75)f | |

*Negative control

Values in the closed bracket are arc sin transformed

Data represented as mean ± SD and values followed by the same letter along the column are not significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other

Fig. 1.

In vitro antibacterial activity of neem leaf extract and nimbolide against X. oryzae pv. oryzae. A Neem leaf extract B Nimbolide

Fig. 2.

Antifungal activity of neem leaf extract (A) and nimbolide (B) against F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense

Fig. 3.

Antifungal activity of neem leaf extract (A) and nimbolide (B) against M. phaseolina

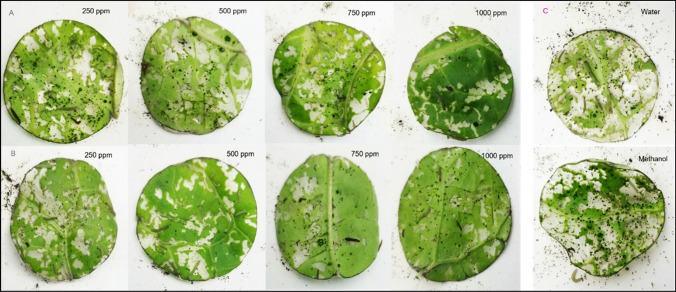

Fig. 4.

Antifungal activity of neem leaf extract (A) and nimbolide (B) against P. aphanidermatum

The antimicrobial activities of nimbolide against fungi and bacteria were also compared with those of the methanolic neem leaf extract. Neem leaf extract had a fungitoxic effect on M. phaseolina [40, 41]. Niaz et al. [42] stated that 0.1% of neem oil was effective in inhibiting the growth of M. phaseolina. Similarly, inhibition of mycelial growth was seen at 1000 ppm of both neem leaf extract and nimbolide. Neem extract inhibited the growth of F. oxysporum [43–45]. Pant et al. [46] reported a 5.32 percent inhibition of mycelial growth at 100 ppm of neem leaf extract. Similarly, in the present study, 55.46 percent inhibition was observed at 1000 ppm of neem leaf extract, whereas nimbolide exhibited 64.46 percent inhibition of mycelial growth. Suleiman and Emua [47] found that a 100 percent concentration of neem leaf extract inhibited P. aphanidermatum to an extent of 77 percent, whereas nimbolide inhibited up to 82.77 percent growth inhibition at 1000 ppm. Neem leaf extract was also effective in controlling P. aphanidermatum [48, 49]. Leaf extract of A. indica tends to inhibit the growth X. oryzae pv. oryzae [50, 51]. The chloroform extract of 24 different plant species assayed against X. oryzae pv. Oryzae showed the formation of zone of inhibition ranging from 7.5–18.5 mm [52], whereas the present study, nimbolide inhibited the growth of X. oryzae pv. oryzae up to a zone of about 20.20 mm at 1000 ppm. The results of the antimicrobial assay clearly indicated that the extracted nimbolide has better activity than the neem leaf extract.

Insecticidal Activity of Nimbolide

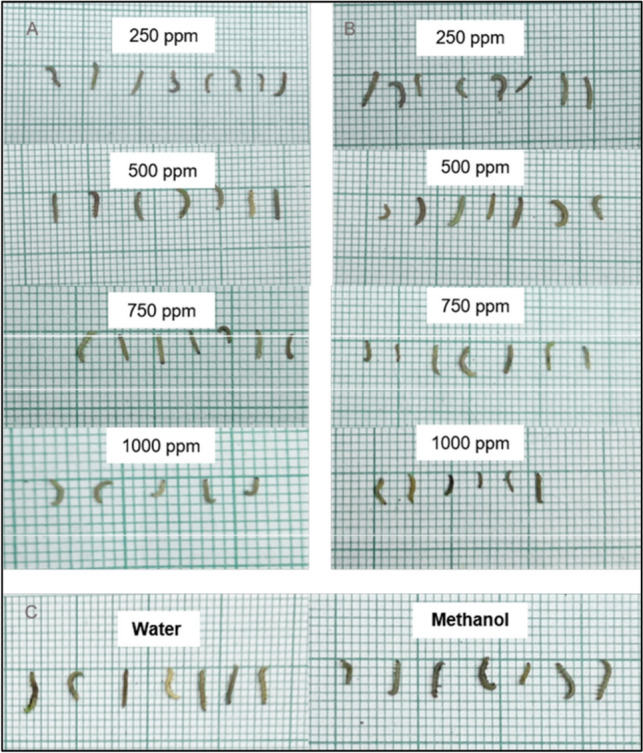

Bioassays were done to determine the susceptibility of P. xylostella to nimbolide. The larval mortality was recorded for up to 6 days. Though feeding damages were observed in both the treated and untreated leaves, less foliar damage was recorded in the treated than in the untreated control (Fig. 5). Significant lethal effects of the crude leaf extract and nimbolide against P. xylostella were observed 5 days after treatment when compared with water and methanol controls. The highest larval mortality was recorded (60.00% and 66.60%) at 1000 ppm in both neem leaf extract and nimbolide, whereas 6 percent of larval mortality was observed in both controls (Table 2). Retarded larval development was observed in the larvae fed on nimbolide compared to the neem leaf extract-treated leaf discs (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Feeding activity of P. xylostella on cauliflower leaf disc A Neem leaf extract B Nimbolide C Negative control – water and methanol

Fig. 6.

Length of surviving P. xylostella larvae recorded on sixth day at different concentrations. A Neem leaf extract B Nimbolide C Negative control – water and methanol

The larvae exposed to nimbolide showed a lower mortality percentage of 33.33 and 43.33 percent at 250 ppm and 500 ppm, respectively. Whereas 40 and 46.67 percent of larval mortality were observed in leaf discs treated with neem leaf extract. The highest larval mortality of 66.66 percent was recorded in the leaf disc treated with nimbolide at 1000 ppm compared to the leaf disc treated with neem leaf extract. This may be due to the fact that the bioactivity of nimbolide is increased by an increase in concentration. The other bioactive compounds present in the neem leaf extract may mask the effect of the compound that is responsible for causing mortality in larvae. The findings of the insecticidal study showed that the nimbolide treatment provided significant larval mortality in comparison with neem leaf extract. Though the nimbolide could provide a moderate level of toxicity against P. xylostella at 1000 ppm, this showed that an increase in concentration may provide better toxicity against the test insect. The above results suggest that the nimbolide compound can be an important component in developing biopesticides to manage P. xylostella. The earlier studies revealed that the seed and leaf extract of neem has antifeedant activity against insect pests [53–56], which inhibits the growth and development of different insect pests [57–59]. Gauvin et al. [60] reported that there was no correlation between the quantity of azadirachtin and the insecticidal activity of neem extract on target insects and suggested that the effect of azadirachtin on target insects may be due to the presence of other active chemical compounds in the neem extracts. In the present study, the growth of P. xylostella larvae was stunted and they were malformed when treated with nimbolide. It was in accordance with Liang et al. [61], as larval growth was prolonged and retarded by the application of neem-based insecticides.

In Silico Antimicrobial Insecticidal Activity of Nimbolide

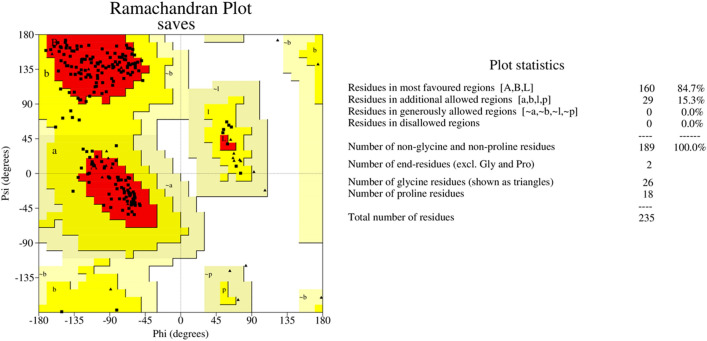

Homology modelled structures of target proteins (Table 3) were used for docking with nimbolide. Docking results showed that there was a promising interaction of nimbolide with all target proteins of fungus, bacteria and insect (Table 1). In F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense, the guanine nucleotide-binding protein beta subunit has a binding energy of −7.23 kcal/mol. It forms a hydrogen bond with LEU 60 amino acid residue. Furan ring of nimbolide being an amide-Pi stacked with LEU 60. GTP-binding protein RHO1 forms a hydrogen bond at the LEU 118 residue with a binding energy of −7.14 kcal/mol. Other amino acid residues such as TYR 156, ARG 117, MET 292, PHE 179, and SER 287 also had Van der Waals interactions with the nimbolide. In addition, nimbolide expressed a pi-sigma interaction with ILE 284 of the receptor. In P. aphanidermatum, NLPs showed only Van der Waals interactions with amino acid residues such as LYS 209, LYS 206, HIS 128, HIS 101, ASN 196, ASP 158, and LEU 157. Succinate dehydrogenase had two hydrogen bonds at ARG 88 and ASN 1 residues with a binding energy of −5.82 kcal/mol. It also forms a Van der Waals interaction with the furan ring of nimbolide at the ASN 91 residue. Cellulose synthase interacts with oxygen residues in the furan ring of nimbolide through a single H-bond at GLU 864 residue with a binding energy of −6.31 kcal/mol. In M. phaseolina, PHE 228 amino acids of the thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein target are hydrogen bonded to the ester oxygen atom of nimbolide with a binding energy of −7.84 kcal/mol, and they also have Pi-Pi interactions with the furan ring of nimbolide. Ramachandran plot of the modelled thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein was shown in Fig. 7. The lectin target protein formed Van der Waals interactions with LYS 221, LYS 223, SER 236, GLY 261, GLU 262, SER 253, ALA 255, LYS 222, THR 224, and ARG 256 residues. It also formed alkyl bond with LEU 257 residue. The effective binding of these protein targets may result in the disruption of the target proteins, which indicates reduced intracellular cAMP levels, decreased pathogenicity, and changes in physiological traits like heat resistance, colony morphology, spore production, host morphological changes, and germination frequency [62–64].

Table 3.

Protein targets of fungus, bacteria and insect with its UniProt ID, Protein length, QMEAN Score, Homology template PDB ID, Homology modelled structure and its functions

| S. no. | Protein target (Uniprot ID) | Homology Modelled structures | S. no. | Protein target (Uniprot ID) | Homology modelled structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bacteria protein targets Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | |||||

| 1 | Peptide deformylase (A0A0M1KN68) |  |

2 | Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH]# (Q2P9J6) |  |

|

Insect protein targets Plutella xylostella | |||||

| 1 | Acetylcholinesterase (Ache) (A0A1L8D6U8) |  |

2 | Ryanodine receptor# (G8EME3) |  |

|

Fungal protein targets Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense | |||||

| 1 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein beta subunit (Q96VA6) |  |

2 | GTP-binding protein RHO1 (N4UV59 |  |

| Macrophomina phaseolina | |||||

| 1 | Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein (K2S6W8) |  |

2 | Lectin (K2RG75) |  |

| Pythium aphanidermatum | |||||

| 1 | Necrosis- and ethylene-inducing peptide 1 (Nep1)-like proteins (NLPs)# (Q9SPD4) |  |

2 | Succinate dehydrogenase (F8T2Z6) |  |

| 3 | Cellulose synthase (H6D5B6) |  |

|||

#Protein target with 3D PDB structure

Fig. 7.

Ramachandran plot generated by PROCHECK validation server for the thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein

In X. oryzae pv. oryzae, two conventional hydrogen bonds were formed by peptide deformylase with amino acid residues of GLY 99 and TYR 101 having binding energy of −7.34 kcal/mol. This binding results in the deformation of protein production, development, and survival in bacteria [65]. Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH] showed an interaction energy of −6.64 kcal/mol and exhibited a hydrogen bond between the lactone ring of nimbolide and the CYS 12 amino acid residue of the protein. Any effect on this protein of bacteria causes deprivation of the fatty acid synthesis pathway, which results in retarding the conversion of intermediates to several beneficial end products that include lipid A and the vitamins biotin and lipoic acid that are necessary for the growth and development of bacteria [66].

In P. xylostella, acetylcholinesterase (Ache) was linked to the ligand with a single hydrogen bond in the TRP 332 amino acid residue of the receptor. It had a binding energy of −7.80 kcal/mol. This proves the inhibition of the activity of the acetylcholinesterase (AChE), which degrades acetylcholine (ACh), a crucial neurotransmitter in the insect central nervous system [67, 68]. Apart from hydrogen bonding, pi–pi interaction was observed with PHE 280. Ryanodine receptor was reported to have a binding energy of −7.58 kcal/mol and a conventional hydrogen bond with the VAL 73 residue of the receptor to the oxygen atom of the furan ring of the ligand. The specific binding of insecticides to RyRs in the muscles of insects causes an uncontrolled release of calcium from internal stores in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which causes the insects to stop feeding, become lethargic, paralyse their muscles, and eventually die [69]. Further, alkyl bonds were also observed between HIS 147 and VAL 168 residue of the Ryanodine receptor.

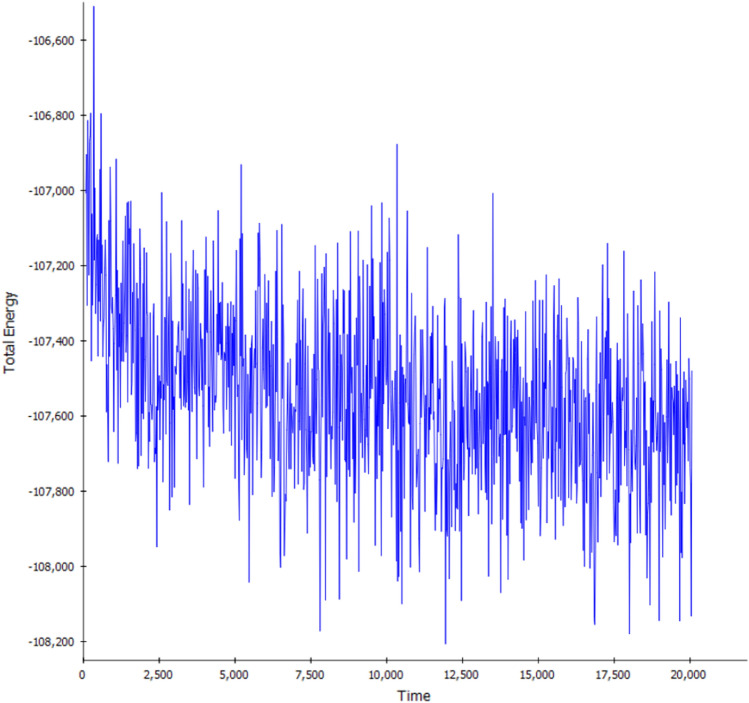

To further understand the stability, MD simulations were performed for nimbolide and Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein by 20 ns. The RMSD value is used to measure the structural alterations of atomic position in MD simulation [70]. The average root mean square deviation (RMSD) values were found to be 0.06 Å. The RMSD graph of the complex structure nimbolide and the Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein showed lesser deviation after 30th conformation (60 ps) as shown in (Fig. 8). The results indicate that nimbolide tightly bind to the binding pocket of Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein. Likewise, total energy of the complex structure was very low throughout the simulation at different conformations (Fig. 9). The complex attained equilibrium condition till the end of 20 ns simulation. The simulation of nimbolide and Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein showed well and have better inhibition activity. The results of biological activity experiments combined with structural analysis shows a single hydrogen bond interaction with PHE 228 in the Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein specificity pocket play an important role in inhibiting M. phaseolina activity.

Fig. 8.

RMSD patterns of the nimbolide and Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein complex obtained from MD simulation

Fig. 9.

Total energy of the nimbolide and Thaumatin pathogenesis-related protein complex obtained from MD simulation

Docking studies revealed the binding position of nimbolide to the active sites of all the protein targets except the NLPs of P. aphanidermatum and the lectin of M. phaseolina, which exhibited Van der Waals interactions alone and no hydrogen bonding was observed. Further, hydrogen bonds were mostly found with the furan ring of nimbolide. In-silico studies of nimbolide against different protein targets have shown possible inhibitory activity against plant pathogens. By the use of molecular dynamics simulations, the docked structure at the binding sites was shown to be stable. Thus, in silico studies on molecular docking of nimbolide have shown beyond doubt that it has increased binding energy and forms perfect bonding with the active sites of the target, which are responsible for the inhibition of F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense, P. aphanidermatum, M. phaseolina, X. oryzae pv. oryzae, and P. xylostella. in vitro and in silico studies confirmed the antimicrobial and insecticidal activity of the nimbolide. Hence, nimbolide could be explored as a novel molecule for the management of fungal pathogens, bacterial pathogens, and insect pests.

Conclusion

Since antiquity, humans have recognised and documented the importance of plant-derived natural products and their extracts that are utilised by the lay population. It's interesting to note that, due to their inherent qualities and lack of potential for resistance, secondary metabolites produced from plants became of significant interest to scientists and researchers. As a result, compounds derived from plants are frequently used for preventative and controlling measures against pathogens and pests in agriculture. For the first time, we investigated the potential of nimbolide, extracted from the leaves of Azadirachta indica, against agriculturally important pathogens and pests. The study confirmed the bioactivity of nimbolide against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, Pythium aphanidermatum, Macrophomina phaseolina, and Plutella xylostella and provided a strong basis for the formulation of nimbolide-based biological pesticides. As, Nimbolide was extracted from neem leaves, and not from the kernel or other parts of the tree, as others are seasonal. The isolated nimbolide has got good biological activity, hence, formulations can be developed and it can be used for field trails.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Navinraj S, acknowledges the Junior research fellowship grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. The authors duly acknowledge Dr. S. Velmathi, Professor and Head, Department of Chemistry, National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, for providing NMR facilities. The authors also thank the Department of Plant Biotechnology, Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, for providing infrastructure facilities to carry out the above research work.

Author Contribution

Santhanakrishnan VP, Manikanda Boopathi N and Gnanam R have conceptualized and designed the research work; Balasubramani V has designed the insect bioassay studies; Nakkeeran S and Raghu R have designed the microbial bioassay studies; and Navinraj S and Saranya N have performed the docking and simulation work; Navinraj S executed the overall research work and written the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar N, Pathera AK, Saini P, Kumar M. Harmful effects of pesticides on human health. Ann Agric Biol Res. 2012;17:125–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khursheed A, Rather MA, Jain V, Rasool S, Nazir R, Malik NA, Majid SA. Plant based natural products as potential ecofriendly and safer biopesticides: a comprehensive overview of their advantages over conventional pesticides, limitations and regulatory aspects. Microb Pathog. 2022;17A:105854. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grewal AS. Pesticide residues in food grains vegetables and fruits: a hazard to human health. J Med Chem Toxicol. 2017;2:1–7. doi: 10.15436/2575-808X.17.1355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brühl CA, Zaller JG. Biodiversity decline as a consequence of an inappropriate environmental risk assessment of pesticides. Front Environ Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2019.00177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schäfer RB, Liess M, Altenburger R, Filser J, Hollert H, Roß-Nickoll M, Scheringer M. Future pesticide risk assessment: narrowing the gap between intention and reality. Environ Sci Eur. 2019;31:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12302-019-0203-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngegba PM, Cui G, Khalid MZ, Zhong G. Use of botanical pesticides in agriculture as an alternative to synthetic pesticides. Agriculture. 2022;24:600. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12050600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grdiša M, Gršić K (2013) Botanical insecticides in plant protection. Agric Conspect Sci 78:85–93. https://hrcak.srce.hr/104637

- 8.Baby AR, Freire TB, Marques GD, Rijo P, Lima FV, Carvalho JC, Rojas J, Magalhães WV, Velasco MV, Morocho-Jácome AL. Azadirachta indica (Neem) as a potential natural active for dermocosmetic and topical products: a narrative review. Cosmetics. 2022;2:58. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics9030058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koul O, Isman MB, Ketkar CM. Properties and uses of neem Azadirachta indica. Can J Bot. 1990;68:1–11. doi: 10.1139/b90-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan QG, Luo XD. Meliaceous limonoids: chemistry and biological activities. Chem Rev. 2011;111:7437–7522. doi: 10.1021/cr9004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anitha G, Josepha Lourdu Raj J, Narasimhan S, Anand Solomon K, Rajan SS. Nimbolide and isonimbolide. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2006;8:445–449. doi: 10.1080/10286020500173267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magaldi S, Mata-Essayag S, De Capriles CH, Pérez C, Colella MT, Olaizola C, Ontiveros Y. Well diffusion for antifungal susceptibility testing. Int J Infect Dis. 2004;8:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valgas C, Souza SMD, Smânia EF, Smânia A., Jr Screening methods to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Braz J Microbiol. 2007;38:369–380. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822007000200034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh RP, Pant NC. Lycorine—a resistance factor in the plants of subfamily Amaryllidoideae (Amaryllidaceae) against desert locust Schistocerca gregaria F. Experientia. 1980;36:552–553. doi: 10.1007/BF01965795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrigach F, Rokni Y, Takfaoui A, Khoutoul M, Doucet H, Asehraou A, Touzani R. In vitro screening homology modeling and molecular docking studies of some pyrazole and imidazole derivatives. Biomed Pharma. 2018;103:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macías-Sánchez K, García-Soto J, López-Ramírez A, Martínez-Cadena G. Rho1 and other GTP-binding proteins are associated with vesicles carrying glucose oxidase activity from Fusarium oxysporum f sp lycopersici. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:671–680. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Rocha AL, Roncero MIG, López-Ramirez A, Mariné M, Guarro J, Martínez-Cadena G, Di Pietro A. Rho1 has distinct functions in morphogenesis cell wall biosynthesis and virulence of Fusarium oxysporum. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1339–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirc K, Hodnik V, Snoj T, Lenarčič T, Caserman S, Podobnik M, Böhm H, Albert I, Kotar A, Plavec J, Borišek J. Nep1-like proteins as a target for plant pathogen control. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009477. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pemberton CL, Salmond GP. The Nep1-like proteins-a growing family of microbial elicitors of plant necrosis. Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;5:353–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong L, Shen YQ, Jiang LN, Zhu XL, Yang WC, Huang W, Yang GF (2015) Succinate dehydrogenase: an ideal target for fungicide discovery Discovery and synthesis of crop protection products. Washington DC, pp 175–194. 10.1021/bk-2015-1204.ch013

- 21.Blum M, Gisi U. Insights into the molecular mechanism of tolerance to carboxylic acid amide (CAA) fungicides in Pythium aphanidermatum. Pest manag sci. 2012;68:1171–1183. doi: 10.1002/ps.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saima S, Wu G. Effect of Macrophomina phaseolina on growth and expression of defense related genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Natl Sci Found Sri Lanka. 2019;47:10–4038. doi: 10.4038/jnsfsr.v47i1.8934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narendrakumar P, Nageshwar L, Parameshwar J, Khan MY, Rayulu J, Hameeda B. In silico and in vitro studies of fungicidal nature of lipopeptide (Iturin A) from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens RHNK 22 and its plant growth-promoting traits. Indian Phytopathol. 2016;69:569–574. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varrot A, Basheer SM, Imberty A. Fungal lectins: structure function and potential applications. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi T, Joshi T, Sharma P, Chandra S, Pande V. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approach to screen natural compounds for inhibition of Xanthomonas oryzae pv Oryzae by targeting peptide deformylase. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:823–840. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guay DR. Drug forecast–the peptide deformylase inhibitors as antibacterial agents. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:513. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s12160427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaivel N, Rajesh R, Velmurugan D, Marimuthu P. Antimicrobial activity of a novel secondary metabolite from Streptomyces sp. and molecular docking studies against Bacterial Leaf Blight pathogen of rice. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017;6:2861–2870. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.611.337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapoor M, Gopalakrishnapai J, Surolia N, Surolia A. Mutational analysis of the triclosan-binding region of enoyl-ACP (acyl-carrier protein) reductase from Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem J. 2004;381:735–741. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sindhu T, Venkatesan T, Prabhu D, Jeyakanthan J, Gracy GR, Jalali SK, Rai A. Insecticide-resistance mechanism of Plutella xylostella (L) associated with amino acid substitutions in acetylcholinesterase-1: a molecular docking and molecular dynamics investigation. Comput Biol Chem. 2018;77:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier D, Bride JM, Hoffmann F, Karch F. Acetylcholinesterase Two types of modifications confer resistance to insecticide. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14270–14274. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)49708-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin L, Liu C, Qin J, Wang J, Dong S, Chen W, Yuchi Z. Crystal structure of ryanodine receptor N-terminal domain from Plutella xylostella reveals two potential species-specific insecticide-targeting sites. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;92:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Announcing the worldwide protein data bank. Struct Mol Biol. 2003;10:980–980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucle acids res. 2014;42:252–258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian W, Chen C, Lei X, Zhao J, Liang J. CASTp 3.0: Computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucle Acids Res. 2018;46:363–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. SwissDock a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucle acids res. 2011;39:270–277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CH, Chang TT, Sun MF, Chen HY, Tsai FJ, Chang KL, Fisher M, Chen CY. Potent inhibitor design against H1N1 swine influenza: structure-based and molecular dynamics analysis for M2 inhibitors from traditional Chinese medicine database. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2011;28:471–482. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2011.10508589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhanya SR, Kumar SN, Sankar V, Raghu KG, Kumar BD, Nair MS. Nimbolide from Azadirachta indica and its derivatives plus first-generation cephalosporin antibiotics: a novel drug combination for wound-infecting pathogens. RSC adv. 2015;5:89503–89514. doi: 10.1039/C5RA16071E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kigodi PG, Blaskó G, Thebtaranonth Y, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA. Spectroscopic and biological investigation of nimbolide and 28-deoxonimbolide from Azadirachta indica. J Nat Prod. 1989;52:1246–1251. doi: 10.1021/np50066a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choudhary S, Dwivedi AK, Singh P. Antifungal activities of neem leaf extracts on the growth of Macrophomina phaseolina in vitro and its chemical characterization. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol. 2017;11:44–48. doi: 10.9790/2402-1104014448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubey RC, Kumar H, Pandey RR. Fungitoxic effect of neem extracts on growth and sclerotial survival of Macrophomina phaseolina in vitro. J Am Sci. 2009;5:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niaz I, Sitara U, Kazmi S A R, Qadri S (2008) Comparison of antifungal properties of neem seed oil collected from different parts of Pakistan. Pak J Bot 40:403. http://142.54.178.187:9060/xmlui/handle/123456789/16954

- 43.Govindachari TR, Suresh G, Gopalakrishnan G, Masilamani S, Banumathi B. Antifungal activity of some tetranortriterpenoids. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:317–320. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(99)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hassanein NM, Abou Zeid MA, Youssef KA, Mahmoud DA. Efficacy of leaf extracts of neem (Azadirachta indica) and chinaberry (Melia azedrach) against early blight and wilt diseases of tomato. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2008;2:763–772. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mengane SK, Kamble SS. Bio efficacy of plant extracts on Fusarium oxysporum f sp cubense causing panama wilt of banana. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2014;4:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pant B, Manandhar S, Manandhar C, Baidhya S. In vitro Evaluation of Fungicides and Botanicals against Fusarium oxysporum f sp cubense of Banana. J Plant Prot Soc. 2020;6:118–126. doi: 10.3126/jpps.v6i0.36478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suleiman MN, Emua SA. Efficacy of four plant extracts in the control of root rot disease of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L] Walp) Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:3806–3808. doi: 10.4314/AJB.V8I16.62063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Islam MT, Faruq AN. Effect of some medicinal plant extracts on damping-off disease of winter vegetable. World Appl Sci J. 2012;17:1498–1503. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khatik SS, Lal AA. Evaluation of bio-agents and botanical against Tomato damping-off (Pythium aphanidermatum) Ann Plant Protect Sci. 2019;27:77–80. doi: 10.5958/0974-0163.2019.00015.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naqvi SAH, Umar UD, Hasnain A, Rehman A, Perveen R. Effect of botanical extracts: A potential biocontrol agent for Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae causing bacterial leaf blight disease of rice. Pak J Agric Res. 2018;32:59–72. doi: 10.17582/journal.pjar/2019/32.1.59.72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanthi S, Sivakumar N, Rajapandian K, Panneerselvam A, Radha N. Anti-bacterial activity of cow urine extract of neem against Xanthomonas oryzae-the causative agent of bacterial leaf blight disease of paddy. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2015;17:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jabeen R, Manzoor M, Irfan S, Iftikhar T. Potential of azadirachtin-d fraction against bacterial leaf blight disease in rice caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae. Pak J Bot. 2013;45:1789–1794. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantzoukas S, Ntoukas A, Lagogiannis I, Kalyvas N, Eliopoulos P, Poulas K. Larvicidal action of cannabidiol oil and neem oil against three stored product insect pests: effect on survival time and in progeny. Bio. 2020;9:321. doi: 10.3390/biology9100321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mikami AY, Ventura MU. Repellent antifeedant and insecticidal effects of neem oil on Microtheca punctigera. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2008;51:1121–1126. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132008000600006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nisbet AJ. Azadirachtin from the neem tree Azadirachta indica: its action against insects. An Soc Entomol Bras. 2000;29:615–632. doi: 10.1590/S0301-80592000000400001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saidi N, Nasution R. Antifeedant activity from neem leaf extract (Azadirachta indica A Juss) J Nat. 2018;18:7–10. doi: 10.24815/jn.v18i1.8781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abla DM, Wolali SN, Komina A, Guillaume KK, Philippe G, Isabelle AG. Treatment and post-treatment effects of neem leaves extracts on Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Afr J Agric Res. 2015;10:472–476. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2014.9314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adhikari K, Niraula D, Shrestha J. Use of neem (Azadirachta indica A Juss) as a biopesticide in agriculture: a review. J Agric Appl Biol. 2020;1:100–117. doi: 10.11594/jaab.01.02.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma T, Qamar A, Khan MA. Evaluation of neem (Azadirachta indica) extracts against the eggs and adults of Dysdercus cingulatus (Fabricius) World Appl Sci. 2010;J9:398–402. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gauvin MJ, Bélanger A, Nébié R, Boivin G. Azadirachta indica: l’azadirachtineest-elle le seulingrédientactif. Phytoprotection. 2003;84:115–119. doi: 10.7202/007814ar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang GM, Chen W, Liu TX. Effects of three neem-based insecticides on diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Crop prot. 2003;22:333–340. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(02)00175-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Konska G, Guillot J, Dusser M, Damez M, Botton B. Isolation and characterization of an N-acetyllactosamine-binding lectin from the mushroom Laetiporus sulfureus. J Biochem. 1994;116:519–523. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lengeler KB, Davidson RC, D'souza C, Harashima T, Shen WC, Wang Pan X, Waugh M, HeitmanJ, Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:746–785. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.746-785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Soundararajan P, Sakkiah S, Sivanesan I, Lee KW, Jeong BR. Macromolecular docking simulation to identify binding site of FGB1 for antifungal compounds. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2011;32:3675–3681. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2011.32.10.3675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chan PF, O’Dwyer KM, Palmer LM, Ambrad JD, Ingraham KA, So C, Lonetto MA, Biswas S, Rosenberg M, Zalacain HDJ, M, Characterization of a novel fucose-regulated promoter (P fcsK) suitable for gene essentiality and antibacterial mode-of-action studies in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2051–2058. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.2051-2058.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang YM, White SW, Rock CO. Inhibiting bacterial fatty acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17541–17544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nabeshima T, Mori A, Kozaki T, Iwata Y, Hidoh O, Harada S, Kasai S, Severson DW, Kono Y, Tomita T. An amino acid substitution attributable to insecticide-insensitivity of acetylcholinesterase in a Japanese encephalitis vector mosquito, Culex tritaeniorhynchus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sattelle DB, Cordova D, Cheek TR. Insect ryanodine receptors: molecular targets for novel pest control chemicals. Invert Neurosci. 2008;8:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s10158-008-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hyndman RJ, Koehler AB. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int J Forecast. 2006;22:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.