ABSTRACT

The orientation of mouse hair follicles is controlled by the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway. Mutations in PCP genes result in two categories of hair mis-orientation phenotype: randomly oriented and vertically oriented to the skin surface. Here, we demonstrate that the randomly oriented hair phenotype observed in frizzled 6 (Fzd6) mutants results from a partial loss of the polarity, due to the functional redundancy of another closely related frizzled gene, Fzd3. Double knockout of Fzd3 and Fzd6 globally, or only in the skin, led to vertically oriented hair follicles and a total loss of anterior-posterior polarity. Furthermore, we provide evidence that, contrary to the prevailing model, asymmetrical localization of the Fzd6 protein is not observed in skin epithelial cells. Through transcriptome analyses and in vitro studies, we show collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 (Cthrc1) to be a potential downstream effector of Fzd6, but not of Fzd3. Cthrc1 binds directly to the extracellular domains of Fzd3 and Fzd6 to enhance the Wnt/PCP signaling. These results suggest that Fzd3 and Fzd6 play a redundant role in controlling the polarity of developing skin, but through non-identical mechanisms.

Keywords: Planar cell polarity, Skin, Hair follicle, Fzd3, Fzd6, Mouse development

Summary: The combined signaling intensity of Fzd3 and Fzd6 determines the orientation of hair follicles in developing mouse skin: tilted, randomly oriented or vertically oriented.

INTRODUCTION

The skin of mammals is a highly organized tissue with many structures in it that exhibit a precise orientation to the body axes. One apparent example is the hair, which is positioned at a fixed angle to the skin surface, rather than straight up. The orientation that each hair follicle extends from the dermis toward the skin surface is correlated to the body axes. For example, in the skin on the back of a mouse, all hair follicles point from anterior (head) to posterior (tail); on the limbs, hair follicles point from proximal (body trunk) to distal (digits). In addition to hairs and hair follicles, many other structures in the skin are also polarized. For example, Merkel cell clusters, the epithelial derivatives that are involved in mechanosensation, are arranged in a semicircle around the base of the guard follicles, with the opening of the semicircle always pointing toward the anterior (Nurse and Diamond, 1984; Boulais and Misery, 2007; Maricich et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2010). Other hair follicle-associated structures, such as sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles and sensory nerve endings, are also polarized in a direction that matches the central hair follicle (Wu et al., 2012; Chang and Nathans, 2013).

The orientation of mammalian skin structures and other surface structures in invertebrates and vertebrates are controlled by a conserved tissue polarity or planar cell polarity (PCP) system. Over 30 years of studies in Drosophila and mammals have revealed a core set of three membrane proteins that regulate PCP: Frizzled (Fzd), Strabismus (Stbm, also known as Vang; Vangl in mammals), and Flamingo (Fmi, also known as Stan; Celsr in mammals) (Wang and Nathans, 2007; Jenny, 2010; Goodrich and Strutt, 2011; Aw and Devenport, 2017; Butler and Wallingford, 2017). Mutations in all three families of PCP genes lead to aberrant hair orientations in mice: Fzd family Fzd6−/− mice (Guo et al., 2004); Vangl family Vangl2lp/lp and Vangl1/2 skin conditional knockout mice (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008; Chang et al., 2016); and Celsr family Celsr1crsh/crsh and Celsr1 knockout mice (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008; Ravni et al., 2009). Interestingly, there appear to be two different types of hair follicle mis-orientation associated with PCP mutants: randomly oriented and oblique to the skin surface, as seen in the Fzd6−/− mice, and vertically oriented, as seen in the Celsr1crsh/crsh, Vangl2lp/lp, and Vangl1/2 skin conditional knockout mice. It is still unclear whether the phenotype differences between these two groups reflect the severities of follicle mis-orientation or distinct categories of polarity disruption.

Genetic analyses in Drosophila and mammals have identified many components of the PCP pathway and expanded our knowledge on the role of PCP genes in controlling tissue polarity. However, the mechanisms through which PCP integrates the global and local signal to orient diverse structures is still largely unknown. A widely accepted model of PCP signaling has emerged from studies in Drosophila wing epithelial cells, which involves the asymmetrical localization of core PCP proteins to different sides of each cell (Wong and Adler, 1993; Usui et al., 1999; Lawrence et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2008; Strutt and Strutt, 2008; Wu and Mlodzik, 2009; Struhl et al., 2012). Fzd proteins are enriched on the distal side of each cell, and Vang/Vangl proteins are enriched exclusively on the opposite proximal side. The multiple cadherin-domain proteins Fmi/Celsr are present on both sides of the cell. This asymmetrical assembly of PCP complex (Fzd versus Vangl) is suggested to create the polarity information across the tissue plane. Recently, studies in developing mouse skin appear to support the same model: before the polarization of mouse skin at embryonic day (E)14.5, Vangl2, Celsr1 and Fzd6 proteins are uniformly distributed at cell-cell borders; after the polarization of mouse skin at E15.5, PCP proteins are enriched on the anterior-posterior sides of epithelial cells and under-represented on the medial-lateral sides (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008). Furthermore, studies on transgenic mice that mosaically express a GFP-Vangl2 fusion protein show that Vangl2 is enriched on the anterior side of the epithelial cells in polarized skins (Devenport et al., 2011). It is unknown whether Fzd6 is also asymmetrically localized in the epithelial cells to provide the vector information when the skin is polarized during development.

The present paper focuses on answering several open questions related to the role of one of the core PCP genes, Fzd6, in controlling skin polarity. (1) Is the random hair orientation in Fzd6−/− mice an intermediate and/or weaker phenotype compared with the vertically oriented hair follicles observed in other PCP mutant mice? We have found that hair follicles only partially lose the anterior-posterior polarity upon loss of Fzd6. Fzd3, a close homolog for Fzd6, is also expressed in the developing skin. Combined deletion of Fzd3 and Fzd6 results in vertically oriented hair follicles and a total loss of anterior-posterior polarity. (2) Is Fzd6 protein asymmetrically localized on the posterior side of the epithelial cells, as predicted by the Drosophila model? We have used genetic mosaic approaches to examine the subcellular localization of both endogenous and ectopically expressed Fzd6 proteins and found a consistent distribution of Fzd6 to all cell-cell borders. (3) What are the possible downstream effectors of Fzd6-induced signaling? Using Affymetrix gene chip analyses, we have identified collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 (Cthrc1) as one potential downstream effector of Fzd6. Cthrc1 directly binds to the extracellular domain of Fzd3 and Fzd6 and might promote skin polarity establishment by selectively enhancing the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway.

RESULTS

Partial loss of anterior-posterior polarity in hair follicles of Fzd6−/− mice

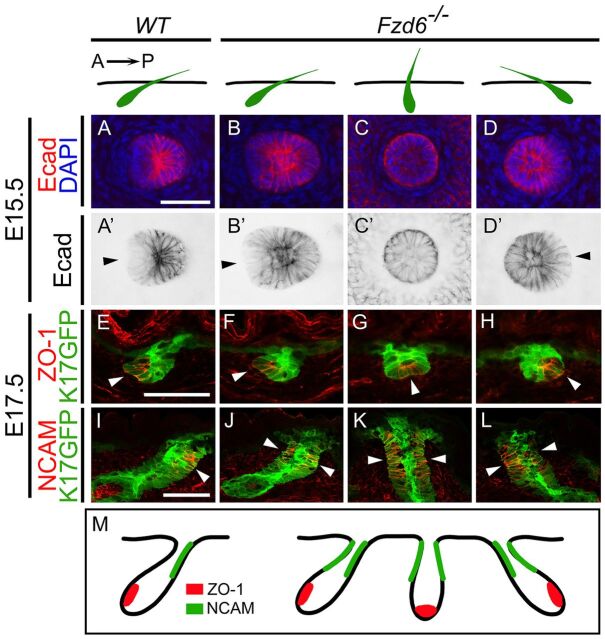

Previous studies have found that deletion of Fzd6 either globally or specifically in the skin caused hair follicle mis-orientations in mouse embryos (Wang et al., 2010; Chang and Nathans, 2013; Chang et al., 2016). In wild-type (WT) embryos, the early developing guard hair follicles on the back have parallel orientations, all pointing from the anterior (head) to the posterior (tail). In Fzd6 mutants, the hair follicles on the back have uncorrelated orientations. This phenotype is very different from the one observed in other PCP mutants (including Vangl2lp/lp, Vangl1/2 skin conditional knockout and Celsr1crsh/crsh mice), in which hair follicles are roughly perpendicular to the skin surface and lose the anterior-posterior polarity (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008; Chang et al., 2016). To determine whether individual mis-oriented hair follicles lose their polarity in Fzd6−/− mice, we collected back skins from E15.5 embryos, the time at which guard hair follicles acquire the first sign of an anterior-to-posterior tilt, and performed whole-mount immunostaining with E-cadherin antibodies to examine the initial hair polarization. Consistent with the literature (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008), hair follicles in WT skin showed a uniform asymmetry: anterior cells expressed reduced levels of E-cadherin and adopted cell shapes distinct from posterior cells (Fig. 1A). In Fzd6−/− skin, hair follicles were randomly oriented. In follicles with a tilted direction, either from anterior to posterior (same orientation as the anteroposterior axis), from posterior to anterior (a reversed orientation to the anteroposterior axis), or any other directions, hair follicles showed an asymmetry. The distribution of cells with low E-cadherin expression was closely correlated with the orientation of hair follicles (Fig. 1B,D, and data not shown). Interestingly, in hair follicles that point straight downward in the skin (about 30-40% of the follicles), this asymmetry in architecture was lost (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Partial loss of anterior-posterior polarity in Fzd6−/− hair follicles. Diagrams above panels depict the sectional view of hair follicles (green) in WT and Fzd6−/− skin. In WT skin, hair follicles extend from the dermis to the skin surface, all pointing from anterior to posterior. In Fzd6−/− skin, the orientations of hair follicles are nearly randomized. (A-D′) Whole-mount immunostaining of E15.5 back skins with E-cadherin (Ecad) antibodies. Hair follicles in WT skin show a tilted angle, hair follicles in anterior cells have reduced levels of E-cadherin and adopt shapes different from posterior cells. Hair follicles in Fzd6−/− skin show a combination of different orientations. Arrowheads indicate cells with low Ecad expression. (E-L) Sagittal sections of E17.5 back skins stained with an anterior marker, ZO-1 (E-H), or a posterior marker, NCAM (I-L). Hair follicles were visualized using the fluorescence of a K17GFP transgene (green). (M) Diagrams showing the asymmetrical distribution of ZO-1 and NCAM in WT hair follicles (left) and that the asymmetry of NCAM is lost in Fzd6−/− hair follicles (right). A→P, anterior-to-posterior. Scale bars: 50 µm.

To determine whether the asymmetry of hair follicles remains as they grow, we stained sagittal sections of back skin at E17.5 with markers for polarization, ZO-1 (also known as Tjp1) and NCAM (also known as Ncam1) (Devenport and Fuchs, 2008). As expected, we found that ZO-1 was highly expressed anteriorly in the lower germ, and NCAM was highly expressed posteriorly in the upper germ in WT skin (Fig. 1E,I). In Fzd6−/− skin, when follicles had an orientation from anterior to posterior, ZO-1 was highly expressed in the anterior compartment of the lower germ (Fig. 1F). In follicles with an orientation from posterior to anterior, ZO-1 was highly expressed in the posterior compartment (Fig. 1H). In follicles that point straight downward in the skin, ZO-1 was highly expressed in the middle compartment of the lower germ (Fig. 1G). These data suggest that the polarization of hair follicles still exists in E17.5 Fzd6−/− embryos, and that the asymmetrical distribution of ZO-1 correlates with the hair follicle orientation. Interestingly, NCAM was found at both the anterior and posterior sides of the upper germ in Fzd6−/− skin, no matter what direction the hair follicles pointed (Fig. 1J-L). Together, these data suggest that hair follicles in Fzd6−/− mice partially lose their anterior-posterior polarity (Fig. 1M).

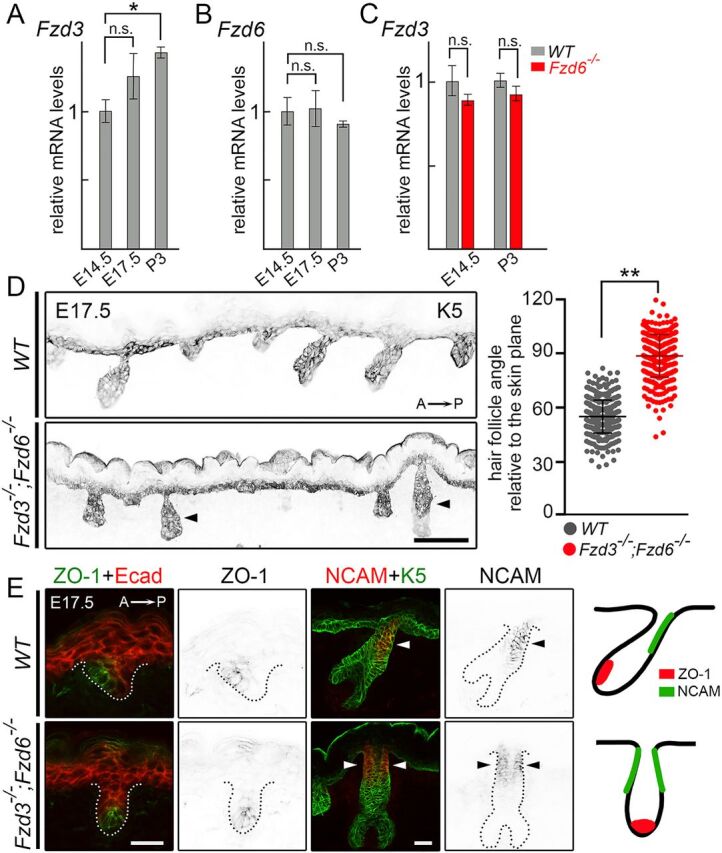

Total loss of anterior-posterior polarity in hair follicles of Fzd3/6 double knockout mice

There are ten Fzd genes in mammals, many of which are expressed in the developing skin (Reddy et al., 2004; Sennett et al., 2015). The partial loss of the anterior-posterior polarity in hair follicles of Fzd6−/− mice made us wonder whether other Fzd genes play a redundant role, especially Fzd3. Fzd3 expression in the skin is undetectable at postnatal ages by a Fzd3lacZ knock-in allele (Hua et al., 2014). However, its expression can be detected in the developing epidermis and hair follicles by RNA in situ hybridization and RT-PCR analyses (Hung et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2004). To characterize the expression pattern of Fzd3 in the skin in detail, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) on skin RNA at multiple developing time points. Fzd3 transcripts were readily detected in skin RNA at E14.5, consistent with earlier reports (Hung et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2004). The expression level of Fzd3 gradually increased over time and was 1.5-fold higher at postnatal day (P)3 than at E14.5 (Fig. 2A). Fzd6 expression in the developing skin did not change over time (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, there was no difference in Fzd3 transcript levels between WT and Fzd6−/− samples, suggesting that Fzd3 expression is not affected by Fzd6 deletion (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Fzd3 and Fzd6 act redundantly in controlling hair follicle polarity. (A) Expression of Fzd3 in WT skins by qRT-PCR. (B) Expression of Fzd6 in WT skins by qRT- PCR. (C) Expression of Fzd3 in WT and Fzd6−/− skin by qRT-PCR. All data are mean±s.e.m. of three biological replicates. GAPDH was used as a control. In A and B, the mRNA expression levels of Fzd3 and Fzd6 in E17.5 and P3 back skins were compared with E14.5 skins using ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test. In C, the Fzd3 expression levels in WT and Fzd6 knockout skins were compared using the Student's t-test at both time points (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant). (D) Epithelial cells and developing hair follicles were visualized by keratin 5 (K5) immunostaining on sagittal sections of E17.5 back skins. In the absence of both Fzd3 and Fzd6, hair follicles are vertically oriented. Hair follicle angles to the plane of the skin were compared using the Student's t-test. **P<0.01. WT, n=456 hair follicles; Fzd3−/−; Fzd6−/−, n=402 hair follicles. Arrowheads indicate vertically oriented hair follicles. (E) Complete loss of anterior-posterior polarity in Fzd3−/−; Fzd6−/− hair follicles. Sagittal sections of E17.5 back skins stained with anterior marker ZO-1 (left panels) or posterior marker NCAM (middle panels). E-cadherin (Ecad) and K5 antibodies were used to highlight skin epithelia and hair follicles. Dotted lines outline the hair follicles. Diagrams show the asymmetrical distribution of ZO-1 and NCAM in WT hair follicles and the complete loss of anterior-posterior polarity in Fzd3−/−; Fzd6−/− hair follicles (right panels). Arrowheads indicate NCAM expressing cells. A→P, anterior-to-posterior. Scale bars: 100 µm in D; 25 µm in E.

To determine whether Fzd3 plays any complementary role to Fzd6 in controlling skin polarity, we crossed Fzd6−/− mice to the Fzd3+/− background and generated Fzd3/6 double knockout embryos (Fzd3−/−;Fzd6−/−). As has been previously reported, all Fzd3−/−;Fzd6−/− embryos developed a fully open neural tube and died within minutes after birth (Wang et al., 2006). We collected back skins from E17.5 embryos and examined hair follicle orientations by staining the skin sagittal sections with keratin 5 (K5) antibodies (Fig. 2D). Whereas hair follicles in WT mice exhibited a tilted angle relative to the epithelial surface, knockout of both Fzd3 and Fzd6 led to vertically oriented hair follicles that resembled the phenotype observed in Vangl2lp/lp, Vangl1/2 skin conditional knockout, and Celsr1crsh/crsh mice. We also stained skin sections with ZO-1 and NCAM antibodies and found that both markers showed a symmetrical pattern in Fzd3/6 double knockout hair follicles, suggesting a total loss of anterior-posterior polarity (Fig. 2E). These data demonstrate that Fzd3/6 act together in controlling hair follicle polarity. The fact that Fzd3 single knockout mice did not show any obvious hair polarity phenotype (Fig. S1) suggests that Fzd6 plays a greater role than Fzd3 in patterning the skin.

Postnatal hair follicle refinement in mice with loss of both Fzd3 and Fzd6

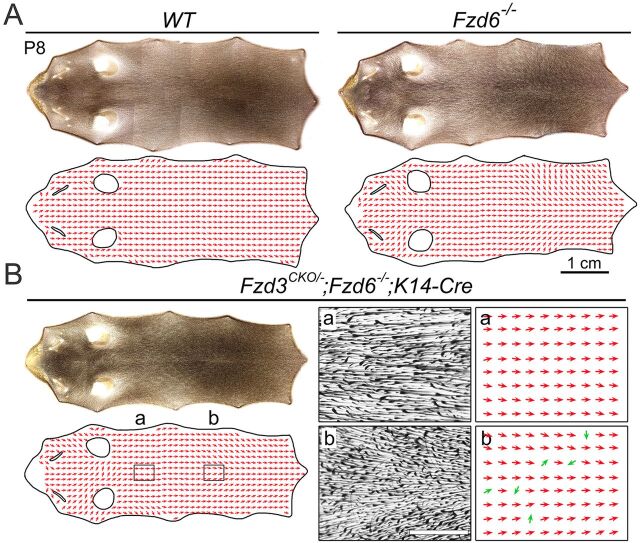

During the first postnatal week, hair follicles undergo a substantial refinement process that minimizes the angular difference among neighboring follicles (Wang et al., 2010; Cetera et al., 2017). By P8, most of the hair follicles in Fzd6−/− mice have aligned from a largely randomized orientation to a uniform anterior-to-posterior direction (Wang et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2015). The mechanism of this refinement is still unknown. To determine whether Fzd3 plays a role in the hair follicle refinement process, we deleted Fzd3 on the Fzd6−/− background using a conditional knockout allele of Fzd3 (Hua et al., 2013) and Keratin14-Cre (K14-Cre). K14-Cre was used to selectively delete Fzd3 in the epidermis starting at ∼E12.5 to bypass the neonatal lethality in Fzd3−/−; Fzd6−/− mice (Dassule et al., 2000; Chang et al., 2016). We observed that hair follicles in Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−; K14-Cre mice exhibited the identical hair polarity phenotypes as Fzd3−/−; Fzd6−/− mice, implying that K14-Cre acts sufficiently early to eliminate Fzd3-induced PCP signaling in the developing epidermis (Fig. S2). Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−; K14-Cre mice were born at an expected ratio and survived without evidence of any obvious growth retardation, allowing us to study the postnatal hair refinement process in these mutants. At P8, hair follicles in Fzd6−/− back skins exhibited limited deviations from the parallel anterior-to-posterior orientation of WT hair follicles (Fig. 3A). The combined loss of Fzd3 and Fzd6 in the epidermis produced a hair pattern that was indistinguishable from Fzd6 single knockouts and WT mice (Fig. 3B). We did observe a sparse population of hair follicles (less than 20 follicles per animal) on the lower back of Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−; K14-Cre mice that had orientations uncorrelated to those of their neighbors, which we did not see in the Fzd6−/− mice. These hair follicles might still be in the process of rotating to their final orientation, perhaps because of a slightly slower refinement. As most of the hair follicles in Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−; K14-Cre mice adopted an anterior-to-posterior direction at P8, similar to Fzd6−/− mice, we concluded that Fzd3 plays little or no role in hair reorientation during the refinement process.

Fig. 3.

Global patterns of hair follicle orientation in back skins of WT, Fzd6−/− and Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−;K14-Cre mice at P8. (A,B) Montage of images of back skin flatmounts and the corresponding vector maps: anterior is to the left and posterior is to the right. Vector maps are constructed by sampling hair follicle orientations at each point on the vector grid using a similar method to that described previously (Chang et al., 2015). The two narrow openings in vector maps mark the locations of eyes and the two round openings mark the locations of the ears. (A) WT and Fzd6−/− skin. (B) Fzd3CKO/−; Fzd6−/−; K14-Cre skin. The boxed areas a and b correspond to the enlarged images in the adjacent vector maps. Green arrows in b highlight the hair follicles that have orientations uncorrelated to those of their neighbors.

Distribution of Fzd6 protein in skin epithelial cells

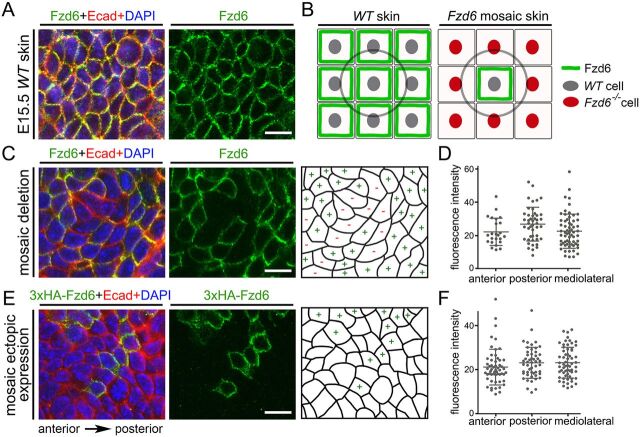

Asymmetrical localization of PCP proteins to different sides of epithelial cells (proximal or distal, anterior or posterior) has been proposed as a mechanism to render tissue polarity in both Drosophila and mammals (Aw and Devenport, 2017; Butler and Wallingford, 2017). Surprisingly, at E15.5, we found that Fzd6 was uniformly distributed at cell-cell borders of the basal cell membranes (Fig. 4A). To determine the subcellular localization of Fzd6 with greater accuracy, we developed a strategy to induce mosaic expression of Fzd6 and examine its localization in individual skin epithelial cells (Fig. 4B). The CAGG-CreERTM mice ubiquitously express a fusion protein of CreER, which enables tamoxifen-induced Cre-mediated recombination (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002). We crossed Fzd6+/−;CAGG-CreERTM males with Fzd6CKO/CKO females and injected pregnant females with low doses of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-HT, 0.2 mg per animal) at E10.5 to induce mosaic recombination. Back skins from E15.5 embryos with the genotype of Fzd6CKO/−;CAGG-CreERTM were collected and stained using Fzd6 and E-cadherin antibodies (E-cadherin was used to outline the plasma membrane). At this 4-HT dose, knockout cell patches comprising as few as four cells to more than 20 cells can be induced. In WT cells, the Fzd6 protein was observed on all sides of the plasma membrane, with no obvious enrichment along the anteroposterior axis or mediolateral axis (Fig. 4C). We quantified the fluorescence intensity on the anterior, posterior and mediolateral borders (113 cells in 20 clones) and identified no significant difference in Fzd6 immunostaining intensity among these sides (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Localization of Fzd6 in individual skin epithelial cells by genetic mosaic labeling. (A) Whole-mount immunostaining of E15.5 WT back skins with Fzd6 (green) and E-cadherin (Ecad, red) antibodies. (B) Diagrams showing the strategy used to visualize the localization of Fzd6 in individual skin epithelial cells. Flat-mount view of nine cells are shown. The cell in the middle (circled) is used to determine the localization of the Fzd6 protein. (C) Mosaic expression of Fzd6 was induced in Fzd6CKO/−; CAGG-CreERTM embryos treated with 4-HT at E10.5. E15.5 back skins were collected and stained with Fzd6 and E-cadherin antibodies. The right panel shows the schematic of the Fzd6+ versus Fzd6– cells. (D) Quantification of fluorescence intensity on anterior, posterior and mediolateral sides of the cells at the borders of Fzd6+ and Fzd6– clones. (E) Mosaic expression of 3×HA-tagged Fzd6 on a WT background was induced in Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6;CAGG-CreERTM embryos treated with 4-HT at E10.5. E15.5 back skins were collected and stained with 3×HA (green) and E-cadherin antibodies. The right panel shows the schematic of the 3×HA-Fzd6+ versus WT cells. (F) Quantification of fluorescence intensity on anterior, posterior and mediolateral sides of the cells at the borders of 3×HA-Fzd6+ and WT clones. Scale bars: 10 µm.

PCP can propagate from cell to cell through communication between neighboring cells. To exclude the possibility that the localization of Fzd6 in WT cells was affected by neighboring knockout cells, we took an overexpression approach. We induced mosaic expression of epitope-tagged Fzd6 in the skin using Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6 mice. Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6 is a conditional overexpression allele of Fzd6 that we have previously generated, in which ectopic expression of 3× hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Fzd6 can be induced in a Cre-dependent manner (Hua et al., 2014). We crossed CAGG-CreERTM males with Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6 females to obtain the Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6;CAGG-CreERTM embryos. We induced mosaic Cre activity, harvested back skins and performed whole-mount immunostaining in the same way as described in the previous section. The 3×HA antibody was used to detect the ectopic Fzd6 protein. We found that the localization pattern of ectopic Fzd6 protein was similar to that observed in the mosaic knockout experiments: Fzd6 was observed on all sides of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4E). Quantification of the fluorescence intensity showed no significant difference between the anterior, posterior and mediolateral borders (102 cells in 12 clones) (Fig. 4F). We also performed the mosaic deletion and overexpression experiments in E16.5 skin and observed a similar immunostaining pattern of Fzd6 (Fig. S3). Together, these data suggest that Fzd6 is not asymmetrically distributed in the mouse skin epithelium.

Identifying Cthrc1 as a potential downstream effector of Fzd6

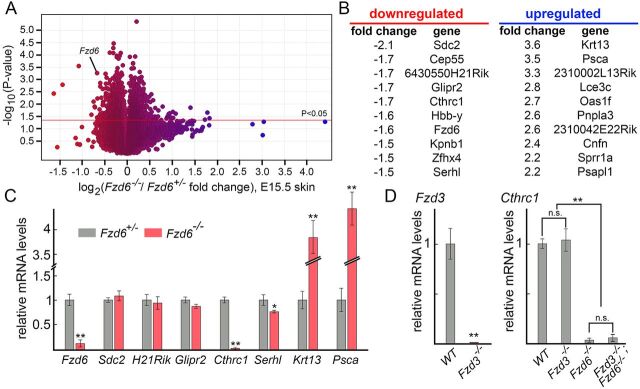

The hair follicle mis-orientation phenotype in Fzd6−/− mice appears to act through the PCP signaling system, but the downstream effectors of Fzd6 remain unknown. In humans, FZD6 loss-of-function mutations have been identified in several families with autosomal recessive nail dysplasia (Fröjmark et al., 2011). A follow-up histological analysis in Fzd6−/− mice shows dysplastic claw development (Cui et al., 2013). Interestingly, transcriptome analysis identified many changes, including downregulation of multiple genes encoding claw-specific keratin, Wnt, bone morphogenetic protein and hedgehog. These data imply that Fzd6 signaling can function through the regulation of gene expression, at least in nail bed epithelial cells during mouse claw development. To search for potential downstream effectors of the Fzd6 signaling pathway in regulating hair follicle orientation, we profiled the transcriptomes of back skins from E15.5 Fzd6+/– and Fzd6–/– embryos by hybridization of three independent samples to Affymetrix MOE430 2.0 gene chips (Fig. 5A). As expected, Fzd6 transcripts were substantially under-represented in the Fzd6–/– samples. In the Fzd6+/– versus Fzd6–/– comparison, about 50 genes exhibited greater than 1.5-fold abundance changes that were statistically significant (P<0.05) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Identification of Cthrc1 as a potential downstream effector of Fzd6. (A) Transcriptome changes in response to the loss of Fzd6. Mouse MOE430 2.0 Affymetrix arrays were hybridized in three biologically independent experiments with RNA from E15.5 Fzd6+/– and Fzd6–/– back skins. As expected, the probe set representing Fzd6 transcripts shows reduced hybridization with RNA from Fzd6–/– skins. Blue, upregulated; red, downregulated expression. (B) Lists of top ten genes with the highest fold-change, including both up- and downregulated genes. (C) Validation of the Affymetrix gene chip data by qRT-PCR using RNA extracted from E15.5 Fzd6+/– and Fzd6–/– back skins. (D) Expression of Cthrc1 in the skin is not affected by Fzd3 deletion. All data are mean±s.e.m. of three biological replicates. GAPDH was used as a control. Quantification of data between two groups was compared using the Student's t-test. The expression levels of Cthrc1 in panel D were compared using ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. n.s., not significant.

We next validated the Affymetrix gene chip data by qRT-PCR. Consistent with the chip hybridization data, we found the expression of Fzd6, Cthrc1 and Serhl was significantly reduced in E15.5 Fzd6–/– skins compared with control skins, and the expression of Krt13 and Psca was significantly increased. Three transcripts that exhibited a significant decline in the chip data were Sdc2, 6430550H21Rik (also known as Tmem255a) and Glipr2 (with estimated declines of ∼2.1-fold, ∼1.7-fold and ∼1.7-fold, respectively; Fig. 5B,C); however, these did not show statistically significant changes in Fzd6–/– skins by qRT-PCR. Among these genes with a validated expression level change, we focused on Cthrc1 because it has been identified as a Wnt co-factor protein that selectively activates the PCP pathway by stabilizing the Wnt-Fzd/Ror2 complex in vitro (Yamamoto et al., 2008). We collected skin RNA from Fzd6+/– and Fzd6–/– mice at multiple developmental time points (E14.5, E15.5, E17.5 and P3) and performed qRT-PCR analysis on Cthrc1. We found the expression level of Cthrc1 in the skin was consistently downregulated upon Fzd6 deletion (data not shown). Furthermore, we compared the expression level of Cthrc1 in E17.5 Fzd3–/– with that found in WT back skins and found no significant difference, suggesting that either Cthrc1 is a specific downstream effector of Fzd6 or the transcriptional changes only occur when the PCP signaling intensity is near or below the threshold for polarization in the skin (Fig. 5D).

To test whether Fzd6 can directly regulate the expression of Cthrc1, we transiently transfected HEK293T cells with Fzd6 expression plasmids and harvested cells 2 days after transfection. CTHRC1 expression levels were then analyzed by qRT-PCR. We chose HEK293T cells because the basal levels of FZD6 and CTHRC1 expression were undetectable in these cells (based on qRT-PCR, data not shown). As expected, the expression of Fzd6 was dramatically increased in transfected HEK293T cells. However, the expression of CTHRC1 was not significantly increased (Fig. S4). Adding the recombinant Wnt ligands Wnt5a and Wnt11 also did not change the CTHRC1 expression level. These data suggest that Fzd6 is not sufficient to drive the expression of CTHRC1 in HEK293T cells. We note that this assay might have uncertainties that limit its interpretation. For example, to activate the signaling pathway, Fzd6 might require additional proteins that are not present in HEK293T cells or, if present, are too divergent for human proteins to interact with the expressed mouse Fzd6.

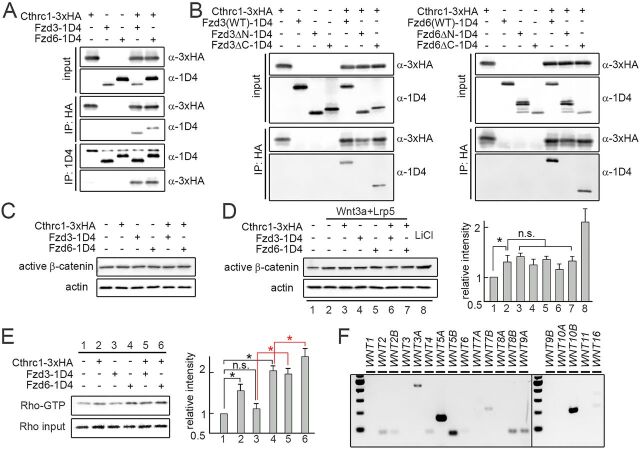

Cthrc1-Fzd3/6 binding promotes the activation of Wnt/PCP signaling

Cthrc1 can directly bind to several components of the Wnt signaling pathway, including Wnt ligands (Wnt3a, Wnt5a and Wnt11), Fzd receptors (Fzd3, Fzd5 and Fzd6) and the co-receptor Ror2, to form a stabilized complex (Yamamoto et al., 2008). Given the evidence that this complex involves both the ligands and receptors, we sought to determine whether the extracellular (N-terminal) domain of Fzd receptors are required for the Cthrc1-Fzd binding. We made expression plasmids for 3×HA-tagged Cthrc1 (referred to as Cthrc1-3×HA) and 1D4-tagged Fzd3 or Fzd6 with the extracellular or intracellular domain deleted (referred to as Fzd3/6ΔN-1D4 and Fzd3/6ΔC-1D4, respectively). We transiently expressed these proteins in HEK293T cells and studied the domain requirement for binding using a co-immunoprecipitation assay. Western blotting of the mutant Fzd3/6 proteins expressed in HEK293T cells following SDS-PAGE revealed a band at the expected size, which suggests that these tagged mutant proteins are stable (Fig. 6B). As expected, when we pulled down Cthrc1 with HA antibodies, we observed that Fzd3 and Fzd6 were co-precipitated. When we pulled down full-length Fzd3 and Fzd6 with 1D4 antibodies, we also observed that Cthrc1 was co-precipitated (Fig. 6A). Deletion of the N-terminal domain of Fzd3 and Fzd6 abolished the Cthrc1-Fzd binding, as Fzd3/6ΔN-1D4 failed to co-precipitate with Cthrc1. However, deletion of the C-terminal domain did not affect the Cthrc1-Fzd binding, as Fzd3/6ΔC-1D4 co-precipitated with Cthrc1 (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that the N-terminal (extracellular) domains of Fzd3 and Fzd6 play a crucial role in the Cthrc1-Fzd interaction.

Fig. 6.

Effects of Cthrc1-Fzd3/6 on canonical and PCP signaling. (A) Binding of Cthrc1 and Fzd3/6 in vitro. Protein extracts from HEK293T cells expressing 1D4-tagged Fzd3 or Fzd6, with or without 3×HA-Cthrc1, were pulled-down with either anti-HA or anti-1D4 antibodies. Both 1D4-Fzd3 and 1D4-Fzd6 co-immunoprecipitate with 3×HA-Cthrc1 and vice versa. (B) Domain requirements of Fzd3/6 for their binding to Cthrc1. Deletion of the N-terminal domain of Fzd3 and Fzd6 abolishes the Cthrc1-Fzd binding, as Fzd3/6ΔN-1D4 fail to co-precipitate with Cthrc1. However, deletion of the C-terminal domain does not affect the Cthrc1-Fzd binding, as Fzd3/6ΔC-1D4 still co-precipitate with Cthrc1. These data suggest the N-terminal (extracellular) domains of Fzd3 and Fzd6 are required for the Cthrc1-Fzd interactions. (C) Cthrc1-Fzd3/6 does not affect the basal level of β-catenin activation in HEK293T cells, as western blotting shows no changes in the active form of β-catenin level in transiently transfected HEK293T cells. Actin was used as a control. (D) Cthrc1-Fzd3/6 does not affect the β-catenin activation induced by Wnt3a. Cells treated with 20 mM LiCl were used as a positive control. (E) There is an increase in RhoA activation in transiently transfected HEK293T cells with Cthrc1 or Fzd6 (lanes 2 and 4 versus lane 1) but not with Fzd3 (lane 3 versus lane 1). A synergistic effect between Fzd3/6 and Cthrc1 in RhoA activation is observed (lane 5 versus lane 3, lane 6 versus lane 4). Experiments were performed three times in D and E and the quantification data are mean±s.e.m. Quantification of data was compared using ANOVA followed by Tukey's t-test. *P<0.05. n.s., not significant. (F) Endogenous expression of WNT genes in HEK293T cells. Among 19 WNT genes, WNT5A, WNT5B and WNT10B are expressed at a high level, as assessed by RT-PCR.

Next, we investigated the effects of Cthrc1-Fzd3/6 binding on the activities of canonical Wnt and PCP signaling in HEK293T cells. For canonical Wnt signaling, we transfected Fzd3/6-encoding cDNAs with or without Cthrc1 and measured the activation of the canonical Wnt signaling by qRT-PCR on known downstream target genes. We found that co-expression of Cthrc1 and Fzd3/6 had no effects on the expression level of LEF1 and AXIN2 (Fig. S5). Western blotting analysis on the lysates also showed no significant changes in the stabilization of β-catenin (Fig. 6C). These data suggest that the basal level of canonical Wnt signaling in HEK293T cells is not significantly affected by Cthrc1-Fzd3/6. We performed similar experiments with the presence of recombinant Wnt3a protein and co-transfection of the canonical Wnt signaling co-receptor Lrp5. We found that Wnt3a/Lrp5 induced a significant increase in stabilization of β-catenin (30% increase in the active form of β-catenin, compared with 110% increase in cells treated with 20 mM LiCl). Co-expression of Cthrc1 and Fzd3/6 caused no significant changes in the stabilization of β-catenin that was induced by Wnt3a/Lrp5 (Fig. 6D). Wnt3a/Lrp5 also induced the upregulation of LEF1 (17% by qRT-PCR, compared with 76% in cells treated with 20 mM LiCl); co-expression of Cthrc1 and Fzd3/6 did not change the expression level of LEF1 (Fig. S5). These data suggest that the activation of canonical Wnt signaling induced by Wnt3a/Lrp5 in HEK293T cells is also not significantly affected by Cthrc1-Fzd3/6.

To test whether the Cthrc1-Fzd interaction can activate non-canonical Wnt signaling, we measured Rho activation using a pulldown assay in which Rho-GTP, but not Rho-GDP, is selectively captured by the Rho-binding domain from rhotekin fused to glutathione-S-transferase. This experiment showed that either Cthrc1 or Fzd6 alone increased the activation of RhoA, and enhanced activation of RhoA was observed in co-expression of Cthrc1 with either Fzd3 or Fzd6 (Fig. 6E). The fact that Fzd6 transient transfection alone in HEK293T cells promotes RhoA activation (lane 4 versus lane 1 in Fig. 6E) suggests that the ligand of Fzd6 is naturally present (e.g. Wnts produced by HEK293T cells). We next examined the endogenous expression level of all 19 WNT genes by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and found that several of them, including WNT5A, WNT5B and WNT10B, are highly expressed in the HEK293T cells (Fig. 6F).

DISCUSSION

The experiments described here establish an essential role for Fzd3 and Fzd6 in controlling hair follicle polarity in mouse skin. In particular, we report that: Fzd6 plays a major role, and loss of Fzd6 leads to a partial loss of the anterior-posterior polarity in hair follicles; Fzd3 plays a minor but supportive role, and loss of both Fzd3 and Fzd6 leads to a total loss of the anterior-posterior polarity in hair follicles; asymmetrical Fzd6 localization is not a mechanism to polarize the mouse skin; and Fzd6 knockout causes significant transcriptome changes, and a positive feedback loop of Wnt/Fzd6-Cthrc1 might play a crucial role in controlling skin polarity.

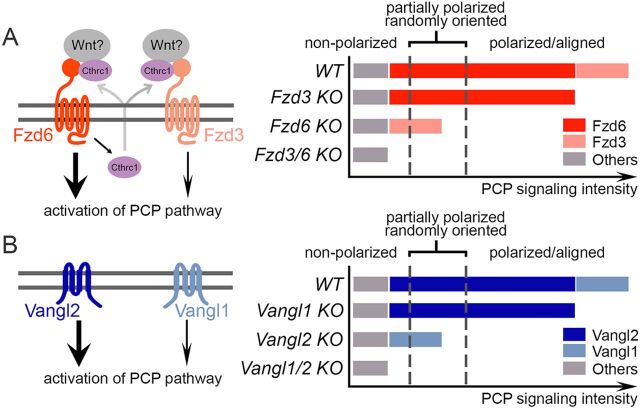

Models of Fzd3/6 signaling in controlling the polarity of hair follicles

All three core PCP gene families (Fzd, Vangl and Celsr) have been shown to control hair follicle orientation (Guo et al., 2004; Devenport and Fuchs, 2008; Ravni et al., 2009). However, the hair follicle polarity defects are different among these PCP mutant mice. Hair follicles in Vangl2lp/lp, Vangl1/2 skin conditional knockout, and Celsr1crsh/crsh mice are oriented perpendicular to the skin plane, whereas Fzd6–/– mice are tilted. We found that hair follicles in Fzd6–/– mice still partially retain their anterior-posterior polarity and a combined loss of Fzd3 and Fzd6 causes a total loss of the polarity. These observations led us to propose a threshold model for Fzd signaling in controlling skin polarity (Fig. 7): the mouse skin receives PCP signaling by both Fzd3 and Fzd6 (Fzd6 plays a greater role than Fzd3) and their combined signaling intensity determines the fate of epithelial cells – polarized and aligned, partially polarized but randomly oriented, or non-polarized. For example, in WT skin, the combined signaling intensity of Fzd3 and Fzd6 is above the threshold for polarization, allowing for hair follicles to grow in an asymmetrical tilt. In the Fzd3 and Fzd6 double knockout skin, the PCP signaling intensity is below the threshold for non-polarization, resulting in hair follicles that grow upright with symmetry. When the signaling intensity is in between the two thresholds, a partial loss of polarity can occur, as observed in Fzd6–/– mice. The observations that Vangl1 single knockout does not affect skin polarity, and that mice with loss of both Vangl1 and Vangl2 have a more severe skin polarity phenotype than Vangl2 single knockout mice, support our threshold model (Chang et al., 2016; Cetera et al., 2017).

Fig. 7.

A threshold model of PCP signaling intensity and polarity outcomes in the developing skin. (A) Left, models of Fzd3/6 signaling. Both Fzd3 and Fzd6 can induce activation of the PCP pathway. Cthrc1, the co-factor that enhances Wnt/PCP signaling, is a potential downstream effector of Fzd6. Right, the threshold model of PCP signaling intensity in determining the polarity outcomes of developing mouse skin. Black dotted lines indicate two thresholds – non-polarization and polarization (see text for details). PCP signaling contributed by Fzd6 (dark red bar), by Fzd3 (light red bar) and by others (gray bar). Note that Fzd6 plays a major role compared with Fzd3. (B) Models of Vangl1/2 signaling. Both Vangl1 and Vangl2 can induce activation of the PCP pathway, but Vangl2 plays a major role compared with Vangl1. Similar to Fzd3/6, the combined signaling intensity of Vangl1 and Vangl2 determines the fate of epithelial cells. PCP signaling contributed by Vangl2 (dark blue bar), by Vangl1 (light blue bar) and by others (gray bar).

Fzds are the principal receptors for the Wnt family of ligands (Bhanot et al., 1996). There are ten mammalian Fzd family members, which can be divided into five subfamilies based on the similarities in amino acid sequences and gene structures (Wang et al., 2016a). Functional redundancy has been found between Fzd genes within the same subfamilies and even in different subfamilies (Wang et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2010, 2012; Ye et al., 2011). Fzd3 and Fzd6 are the most distant subfamily of Fzd receptors, and they mainly function through the non-canonical Wnt/PCP pathway. Recent studies have identified that Fzd3 and Fzd6 play redundant roles in several developmental processes, including neural tube and eyelid closure, inner-ear sensory hair cell patterning and lingual papillae patterning (Wang et al., 2006, 2016b; Hua et al., 2014). Our findings extend the concept of functional redundancy between Fzd3 and Fzd6 to the developing skin and hair follicles.

Asymmetrical localization of membrane PCP proteins and polarity

Asymmetrical distribution of membrane PCP proteins to different sides of a single cell is believed to be the hallmark of PCP establishment (Wang and Nathans, 2007; Goodrich and Strutt, 2011; Aw and Devenport, 2017; Butler and Wallingford, 2017). For example, in Drosophila wing epithelial cells, Stbm is localized to the proximal side, whereas Fzd is localized to the distal side. Fmi is localized at both the proximal and distal sides. These proteins form asymmetrical cell-surface complexes together with their associated cytosolic proteins, and they convey the proximal-distal information from cell to cell within the epithelium. In the developing mouse back skin, Vangl2 has been reported to accumulate on the anterior side of the basal epithelial cells in transgenic mice that mosaically express GFP-Vangl2 fusion protein (Devenport et al., 2011). Whether Fzd family proteins are also asymmetrically localized in the skin epithelium is unknown.

In the present studies, we took genetic sparse labeling approaches to examine the distribution of Fzd6 proteins in skin epithelium in vivo and surprisingly found no asymmetrical localization of Fzd6 (predicted to be the posterior side of the cell by what has been seen in Drosophila). At E15.5, the Fzd6 protein was indeed enriched at cell-cell junctions in skin epithelial cells, but not on any side of the single cell (posterior, anterior or mediolateral). These results contradict the model that Fzd and Vangl proteins are localized to the opposite sides of the cell and convey polarity information. We speculate that either Fzd6 is asymmetrically modified in some manner that changes its activity (e.g. post-translational modifications) or Fzd6-associated protein(s) might establish the subcellular asymmetry. We interpret the data as a fundamental difference between Drosophila and mammalian PCP, or among various tissue types. Different interactions and colocalizations of PCP proteins might contribute specifically to the development of polarity in a given tissue, but not in others. Observations that Fzd3/6 colocalize with Vangl2 at the surface of hair cells in the inner ear support our interpretation (Montcouquiol et al., 2006).

A positive feedback loop of Wnt/Fzd6-Cthrc1 in controlling hair follicle polarity

Among many transcriptional changes identified through non-biased transcriptome analysis in the developing skin upon the loss of Fzd6, we focused on Cthrc1, which is known to be a co-factor of non-canonical Wnt signaling (Yamamoto et al., 2008). We provided biochemical evidence that Cthrc1 can bind directly to the N-terminus of Fzd3 and Fzd6, and demonstrated that the binding between Cthrc1 and Fzd3/6 can enhance Fzd3/6-induced PCP signaling. We concluded, based on the functional analysis in vitro, that Cthrc1 is a potential downstream effector of Fzd6. Our in vitro data led us to hypothesize that the major function of Cthrc1 in the skin is to enhance the Fzd3- and Fzd6-induced PCP signaling (model in Fig. 7A). It will be interesting to know whether Cthrc1 mutant mice show any skin polarity defects or whether there are genetic interactions between Fzd3/Fzd6 and Cthrc1 in skin polarity control. In mice, it has been shown that Cthrc1 genetically interacts with Vangl2 as Cthrc1lacZ/lacZ;Vangl2Lp/+ embryos display typical PCP phenotypes, including a neural tube closure defect in the midbrain region and mis-orientation of the sensory hair cells in the cochlea (Yamamoto et al., 2008). How Cthrc1 interacts with Vangl2 or other core PCP proteins needs further investigation.

The observations that Fzd3 plays a complementary role to Fzd6 in controlling hair follicle polarity and several other developmental processes suggest that they induce a similar signaling cascade upon activation. However, it has been previously reported that ubiquitous overproduction of Fzd3 in mice can rescue a Fzd6–/– phenotype, but ubiquitous overproduction of Fzd6 can only partially rescue a Fzd3–/– phenotype (Hua et al., 2014). The lack of total interchangeability could be due to functional differences between Fzd3 and Fzd6. Our finding that Cthrc1 is transcriptionally regulated by Fzd6 but not Fzd3 might be one manifestation of such signaling specificity. What accounts for the different activities of Fzd3 and Fzd6 is still unknown. As these two proteins share 50% amino acid identity in the N-terminal extracellular domain, 68% in the transmembrane domain and less than 30% identity in the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail (Hua et al., 2014), generating chimeric proteins by domain swapping will be helpful to determine what region(s) might contribute to the functional specificity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse lines and husbandry

The following mouse alleles were used: Fzd6−/− (Guo et al., 2004), Fzd6CKO/CKO (Chang et al., 2016), Rosa26-LSL-Fzd6 (Hua et al., 2014), K17-GFP (Bianchi et al., 2005), Fzd3+/− (Wang et al., 2002), Fzd3CKO/CKO (Hua et al., 2013), CAGG-CreERTM (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002) and K14-Cre (Dassule et al., 2000). Mice were handled and housed according to the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol M005675 of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Immunostaining

For immunostaining of sagittal sections, embryos were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, fresh frozen, cryosectioned at 14 μm and fixed for 10 min in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Sections were washed with PBST (0.1% Triton in PBS) for 10 min and blocked for 1 h with 5% normal donkey or goat serum in PBST. Primary antibodies were incubated for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: goat anti-Fzd6 (AF1526; R&D Systems; 1:400), rat anti-E-cadherin (ab11512-100; Abcam; 1:400), ZO-1 (61-7300; Life Technologies, 1:200), anti-NCAM (MAB310; Millipore; 1:200), Keratin 5 (905501; BioLegend; 1:2000), and rabbit anti-3×HA antiserum (JH5604; the Nathans Lab, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, MD, USA, 1:50,000). Secondary antibodies in PBST were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488-, 594- or 647-conjugated donkey anti-goat, donkey anti-rat or goat anti-rat IgG antibodies (A-11055, A-21209, A-21247, respectively; Invitrogen; 1:500). Finally, sections were washed 3× in PBST and mounted on slides with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech). For whole-mount immunostaining of embryonic skins, embryos were fixed for 1 h in 4% formaldehyde. Back skins were dissected, rinsed with PBS, washed with 0.3% PBST for 30 min and incubated with primary antibodies in 0.3% PBST containing 5% normal goat or donkey serum overnight at 4°C. Skins were then washed in 0.3% PBST for 3× 30 min, incubated in secondary antibodies in 0.3% PBST at room temperature for 2 h, washed in 0.3% PBST and flatmounted in Fluoromount-G. Immunostained samples were imaged using Zeiss LSM500/700 confocal microscopes with Zen software.

Skin wholemounts

The procedures for preparation and processing of skin wholemounts for imaging of hair follicles based on melanin content were similar to previously described methods (Chang and Nathans, 2013; Chang et al., 2014). Dorsal back skins were dissected and flattened by pinning the edges to a flat Sylguard surface, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series and then clarified with benzyl benzoate: benzyl alcohol in a glass dish. Images were collected with a Zeiss Stemi 508 microscope with a color Axiocam 105 in combination with Zen software.

Plasmids and cell culture

Mouse Cthrc1 full-length cDNA was purchased from Open Biosystems (EMM1002-99258104, clone ID 40130184). A 3×HA tag was inserted at the very C-terminus by PCR, and the 3×HA-tagged Cthrc1 was subcloned into the pRK5 vector. 1D4-tagged mouse Fzd3 and Fzd6 plasmids have been described before (Yu et al., 2012). To generate 1D4-tagged Fzd3 and Fzd6 with the extracellular domain deletion (Fzd3/6ΔN-1D4), PCR mutagenesis was used to delete amino acids from Leu25 to Arg203 and from Leu21 to Lys199, respectively. To generate 1D4-tagged Fzd3 and Fzd6 with the intracellular domain deletion (Fzd3/6ΔC-1D4), PCR mutagenesis was used to delete amino acids from Lys501 to Thr664 and from Lys497 to Ser707, respectively. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Standard procedures were used to transfect plasmid DNA into HEK293T grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. For each well of cells to be transfected in a 12 well tray, 0.5 µg of DNA was diluted in 50 µl of serum-free media. 1.5 µl of FuGENE® HD Reagent (Promega) was added into the diluted DNA solution, mixed gently and incubated for 10 min at room temperature before adding to the cells. For all mammalian cell transfections, cells were incubated for 48 h posttransfection before assaying for protein/mRNA expression, unless otherwise specified. Recombinant human Wnt3a, Wnt5a, and Wnt11 (R&D Systems, 5036-WN-010, 645-WN-010, and 6179-WN-010) were used at 100 ng/ml, LiCl (Fisher) at 20 mM.

Cell lysis, gel electrophoresis, co-immunoprecipitation assay and immunoblotting

Transfected cells were lysed with 350 μl ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% deoxycholate] supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, complete mini cocktail tablets). The cell lysates were incubated at 4°C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. A total of 5 μl of the lysates was used as whole-cell lysates by adding 5 μl 2× SDS sample buffer. 50 μl HEK293 T cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation by incubation with 0.2 μl of anti-1D4 monoclonal antibody or 0.4 μl of anti-HA monoclonal antibody (3724S; Cell Signaling; 1:2000) at 4°C overnight. Then, 30 μl Protein G Sepharose (GE Healthcare, 17-0618-01) was added to the lysates, which were further incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Immune complexes were precipitated by centrifugation at 1000 g for 2 min, washed 4× with 1 ml lysis buffer, and dissolved in 30 μl 2× SDS sample buffer. Immunoprecipitates or whole-cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 12.5%, 10% or 7.5% gel and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, IPFL0010). Immunoblots were incubated at 4°C overnight in the primary antibodies: rabbit anti-3×HA antiserum (1:250,000), mAb 1D4 ascites (the Nathans Lab, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, MD, USA; 1:50,000), rabbit anti-active-β-catenin (8814; Cell Signaling Technology; 1:2000); the blots were then incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (32210, 68071; LI-COR Biosciences; 1:10,000). Rho activation was assayed using the Rho Activation Kit (Cytoskeleton, BK036-S) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microarray hybridization

Back skins were dissected from E15.5 Fzd6+/− and Fzd6−/− embryos. RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen) and RNeasy (Qiagen) kits. Three biologically independent sets of hybridizations were hybridized to Affymetrix mouse genome 430 2.0 microarrays and the data analyzed using Spotfire. The microarray data have been deposited in GEO under accession number GSE119928.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

cDNA synthesis was performed using GoScript reverse transcriptase (Promega, A5000) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate in 20 μl reactions with SYBR Premix E×Taq II ROX plus (Takara, RR82LR) with 40 ng first-strand cDNA and 0.2 μg each forward and reverse primers. Samples were cycled once at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C, 58°C and 72°C for 30 s each. Relative mRNA level was calculated using the ΔΔCT method with GAPDH as an endogenous control. Primers used for semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR were selected from the PrimerBank (pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank) database (listed in Table S1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test between two experimental groups and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for more than two experimental groups, followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's test for multiple comparisons, using the GraphPad Prism 7 software. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Megan Maguire and three anonymous referees for assistance and/or advice.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: B.D., H.C.; Formal analysis: B.D., S.V., H.C.; Investigation: B.D., S.V., C.O.-J., H.C.; Data curation: B.D., S.V., C.O.-J., H.C.; Writing - original draft: B.D., S.V., H.C.; Visualization: B.D., S.V., H.C.; Supervision: H.C.; Project administration: H.C.; Funding acquisition: H.C.

Funding

H.C. is supported by the startup funds from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Marjorie Hagan Endowed Professorship.

Data availability

The microarray data have been deposited in GEO under accession number GSE119928.

References

- Aw, W. Y. and Devenport, D. (2017). Planar cell polarity: global inputs establishing cellular asymmetry. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 44, 110-116. 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot, P., Brink, M., Samos, C. H., Hsieh, J.-C., Wang, Y., Macke, J. P., Andrew, D., Nathans, J. and Nusse, R. (1996). A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 382, 225-230. 10.1038/382225a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, N., Depianto, D., McGowan, K., Gu, C. and Coulombe, P. A. (2005). Exploiting the keratin 17 gene promoter to visualize live cells in epithelial appendages of mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7249-7259. 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7249-7259.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulais, N. and Misery, L. (2007). Merkel cells. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 57, 147-165. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, M. T. and Wallingford, J. B. (2017). Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 375-388. 10.1038/nrm.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetera, M., Leybova, L., Woo, F. W., Deans, M. and Devenport, D. (2017). Planar cell polarity-dependent and independent functions in the emergence of tissue-scale hair follicle patterns. Dev. Biol. 428, 188-203. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. and Nathans, J. (2013). Responses of hair follicle-associated structures to loss of planar cell polarity signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E908-E917. 10.1073/pnas.1301430110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H., Wang, Y., Wu, H. and Nathans, J. (2014). Flat mount imaging of mouse skin and its application to the analysis of hair follicle patterning and sensory axon morphology. J Vis Exp. 88, e51749. 10.3791/51749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H., Cahill, H., Smallwood, P. M., Wang, Y. and Nathans, J. (2015). Identification of astrotactin2 as a genetic modifier that regulates the global orientation of mammalian hair follicles. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005532. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H., Smallwood, P. M., Williams, J. and Nathans, J. (2016). The spatio-temporal domains of Frizzled6 action in planar polarity control of hair follicle orientation. Dev. Biol. 409, 181-193. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-S., Antic, D., Matis, M., Logan, C. Y., Povelones, M., Anderson, G. A., Nusse, R. and Axelrod, J. D. (2008). Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell 133, 1093-1105. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.-Y., Klar, J., Georgii-Heming, P., Fröjmark, A.-S., Baig, S. M., Schlessinger, D. and Dahl, N. (2013). Frizzled6 deficiency disrupts the differentiation process of nail development. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 1990-1997. 10.1038/jid.2013.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassule, H. R., Lewis, P., Bei, M., Maas, R. and McMahon, A. P. (2000). Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development 127, 4775-4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenport, D. and Fuchs, E. (2008). Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1257-1268. 10.1038/ncb1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenport, D., Oristian, D., Heller, E. and Fuchs, E. (2011). Mitotic internalization of planar cell polarity proteins preserves tissue polarity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 893-902. 10.1038/ncb2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröjmark, A.-S., Schuster, J., Sobol, M., Entesarian, M., Kilander, M. B. C., Gabrikova, D., Nawaz, S., Baig, S. M., Schulte, G., Klar, J., et al. (2011). Mutations in Frizzled 6 cause isolated autosomal-recessive nail dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 852-860. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, L. V. and Strutt, D. (2011). Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development 138, 1877-1892. 10.1242/dev.054080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, N., Hawkins, C. and Nathans, J. (2004). Frizzled6 controls hair patterning in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9277-9281. 10.1073/pnas.0402802101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, S. and McMahon, A. P. (2002). Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 244, 305-318. 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Z. L., Smallwood, P. M. and Nathans, J. (2013). Frizzled3 controls axonal development in distinct populations of cranial and spinal motor neurons. Elife 2, e01482. 10.7554/eLife.01482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Z. L., Chang, H., Wang, Y., Smallwood, P. M. and Nathans, J. (2014). Partial interchangeability of Fz3 and Fz6 in tissue polarity signaling for epithelial orientation and axon growth and guidance. Development 141, 3944-3954. 10.1242/dev.110189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung, B. S., Wang, X.-Q., Cam, G. R. and Rothnagel, J. A. (2001). Characterization of mouse Frizzled-3 expression in hair follicle development and identification of the human homolog in keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 116, 940-946. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny, A. (2010). Planar cell polarity signaling in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 93, 189-227. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385044-7.00007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P. A., Casal, J. and Struhl, G. (2004). Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development 131, 4651-4664. 10.1242/dev.01351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricich, S. M., Wellnitz, S. A., Nelson, A. M., Lesniak, D. R., Gerling, G. J., Lumpkin, E. A. and Zoghbi, H. Y. (2009). Merkel cells are essential for light-touch responses. Science 324, 1580-1582. 10.1126/science.1172890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol, M., Sans, N., Huss, D., Kach, J., Dickman, J. D., Forge, A., Rachel, R. A., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., Bogani, D., et al. (2006). Asymmetric localization of Vangl2 and Fz3 indicate novel mechanisms for planar cell polarity in mammals. J. Neurosci. 26, 5265-5275. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4680-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, C. A. and Diamond, J. (1984). A fluorescent microscopic study of the development of rat touch domes and their Merkel cells. Neuroscience 11, 509-520. 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90041-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravni, A., Qu, Y., Goffinet, A. M. and Tissir, F. (2009). Planar cell polarity cadherin Celsr1 regulates skin hair patterning in the mouse. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 2507-2509. 10.1038/jid.2009.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, S. T., Andl, T., Lu, M.-M., Morrisey, E. E. and Millar, S. E. (2004). Expression of Frizzled genes in developing and postnatal hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol. 123, 275-282. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R., Wang, Z., Rezza, A., Grisanti, L., Roitershtein, N., Sicchio, C., Mok, K. W., Heitman, N. J., Clavel, C., Ma'ayan, A., et al. (2015). An integrated transcriptome atlas of embryonic hair follicle progenitors, their niche, and the developing skin. Dev. Cell 34, 577-591. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl, G., Casal, J. and Lawrence, P. A. (2012). Dissecting the molecular bridges that mediate the function of Frizzled in planar cell polarity. Development 139, 3665-3674. 10.1242/dev.083550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt, H. and Strutt, D. (2008). Differential stability of flamingo protein complexes underlies the establishment of planar polarity. Curr. Biol. 18, 1555-1564. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui, T., Shima, Y., Shimada, Y., Hirano, S., Burgess, R. W., Schwarz, T. L., Takeichi, M. and Uemura, T. (1999). Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell 98, 585-595. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80046-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. and Nathans, J. (2007). Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: new insights and new questions. Development 134, 647-658. 10.1242/dev.02772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Thekdi, N., Smallwood, P. M., Macke, J. P. and Nathans, J. (2002). Frizzled-3 is required for the development of major fiber tracts in the rostral CNS. J. Neurosci. 22, 8563-8573. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08563.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Guo, N. and Nathans, J. (2006). The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 26, 2147-2156. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Chang, H. and Nathans, J. (2010). When whorls collide: the development of hair patterns in frizzled 6 mutant mice. Development 137, 4091-4099. 10.1242/dev.057455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Chang, H., Rattner, A. and Nathans, J. (2016a). Frizzled receptors in development and disease. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 117, 113-139. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Williams, J., Rattner, A., Wu, S., Bassuk, A. G., Goffinet, A. M. and Nathans, J. (2016b). Patterning of papillae on the mouse tongue: A system for the quantitative assessment of planar cell polarity signaling. Dev. Biol. 419, 298-310. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L. L. and Adler, P. N. (1993). Tissue polarity genes of Drosophila regulate the subcellular location for prehair initiation in pupal wing cells. J. Cell Biol. 123, 209-221. 10.1083/jcb.123.1.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.-H., Stumpfova, M., Jensen, U. B., Lumpkin, E. A. and Owens, D. M. (2010). Identification of epidermal progenitors for the Merkel cell lineage. Development 137, 3965-3971. 10.1242/dev.055970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. and Mlodzik, M. (2009). A quest for the mechanism regulating global planar cell polarity of tissues. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 295-305. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H., Williams, J. and Nathans, J. (2012). Morphologic diversity of cutaneous sensory afferents revealed by genetically directed sparse labeling. Elife 1, e00181. 10.7554/eLife.00181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S., Nishimura, O., Misaki, K., Nishita, M., Minami, Y., Yonemura, S., Tarui, H. and Sasaki, H. (2008). Cthrc1 selectively activates the planar cell polarity pathway of Wnt signaling by stabilizing the Wnt-receptor complex. Dev. Cell 15, 23-36. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X., Wang, Y., Rattner, A. and Nathans, J. (2011). Genetic mosaic analysis reveals a major role for frizzled 4 and frizzled 8 in controlling ureteric growth in the developing kidney. Development 138, 1161-1172. 10.1242/dev.057620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H., Smallwood, P. M., Wang, Y., Vidaltamayo, R., Reed, R. and Nathans, J. (2010). Frizzled 1 and frizzled 2 genes function in palate, ventricular septum and neural tube closure: general implications for tissue fusion processes. Development 137, 3707-3717. 10.1242/dev.052001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H., Ye, X., Guo, N. and Nathans, J. (2012). Frizzled 2 and frizzled 7 function redundantly in convergent extension and closure of the ventricular septum and palate: evidence for a network of interacting genes. Development 139, 4383-4394. 10.1242/dev.083352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.