Abstract

Cell therapy is an integral modality of regenerative medicine. Macrophages are known for their sensitivity to activation stimuli and capability to recruit other immune cells to the sites of injury and healing. In addition, the route of administration can impact engraftment and efficacy of cell therapy, and modern neuro-interventional techniques provide the possibility for selective intra-arterial (IA) delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) with very low risk. The effects of radiolabelling and catheter transport on differentially activated macrophages were evaluated. Furthermore, the safety of selective IA administration of these macrophages to the rabbit brain was assessed by single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) and ultra-high-field (9.4 T) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Cells were successfully labeled with (111In)In-(oxinate)3 and passed through a microcatheter with preserved phenotype. No cells were retained in the healthy rabbit brain after IA administration, and no adverse events could be observed either 1 h (n = 6) or 24 h (n = 2) after cell administration. The procedure affected both lipopolysaccharide/gamma interferon (LPS/IFNγ) activated cells and interleukin 4 (IL4), interleukin 10 (IL10)/transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) activated cells to some degree. The LPS/IFNγ activated cells had a significant increase in their phagocytotic function. Overall, the major impact on the cell phenotypes was due to the radiolabeling and not passage through the catheter. Unstimulated cells were substantially affected by both radiolabeling and catheter administration and are hence not suited for this procedure, while both activated macrophages retained their initial phenotypes. In conclusion, activated macrophages are suitable candidates for targeted IA administration without adverse effects on normal, healthy brain parenchyma.

Keywords: endovascular, intra-arterial, MRI, SPECT/CT, rabbit

Introduction

In recent years, the field of regenerative medicine has expanded dramatically with the development of cell transplantations. Cell transplantations are used in a broad veracity of diseases with both stem cells and immune cells for the treatment of cancer, autoimmune diseases, and regeneration of damaged tissues1–4.

With the advent of more extensive clinical trials, translation from small rodents to humans has also brought new challenges to the field, such as scalability and covering a larger target area with the same cell graft density 5 . The development of cell therapy as an integral part of regenerative medicine has a long history 5 . During the past 15 years, a range of different cell types has been tested in several disease states, primarily in small rodents, with promising results including but not limited to stroke, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and cancer. A typical cell-based therapy is an injection of immune cells such as macrophages, T-cells, B-cells, and natural killer cells6–11. Macrophages are known for their sensitivity to activation stimuli and the capability to recruit other immune cells to the sites of injury and healing. These properties make macrophages viable treatment candidates in cancer and many other disease settings12,13. Clinical cell-based therapy has traditionally entailed the administration of monocytes, that is, naive macrophages14,15. These circulate in the blood until they reach a target tissue, where they may become differentially activated depending on the tissue stimuli, resulting in phenotypes that either drive or modulate the inflammatory process.

Compared with pharmacological treatment, in cell therapy, the route of administration requires more consideration due to the complexity of the cells’ biological characteristics, biodistribution, and tissue interactions16,17. The potential advantages of cell transplantation using an intra-arterial (IA) microcatheter are: (i) targeted delivery to the site of injury and consequently increased treatment efficacy and (ii) decreased off-target accumulation and therefore reduced risk of side effects. One disadvantage, compared with standard injections, is that it is significantly more invasive, hence the risk of tissue damage. Previous microcatheter-based cell delivery has proven to increase engraftment in organs such as the intestines and bone marrow 18 . Yet, the validation of microcatheter delivery of radiolabeled cells to the central nervous system (CNS) is currently lacking, such that the degree of in vivo cellular functionality post-transfer is unknown. The “cell quality” after radiolabeling has traditionally been assessed solely on the basis of viability staining, low-specificity biopsy staining, and treatment efficiency19–21. For the therapeutic efficiency of cell transplantation, it is thus crucial to ensure that the cells are unaltered by the delivery technique and maintain their functionality in vivo. Since a common cell type to administer is monocytes, it then implies that the cells reach their target site in a monocyte state. If cells instead were to be activated due to the administration technique, it could initiate an aggressive inflammatory response, hence damaging the tissue. This effect in some treatments is desirable while in others can cause severe complications and tissue damage or even support tumor growth22–24. If transplantation of unstimulated monocytes were to be used for cancer treatment, the desire would be for the cells to differentiate into lipopolysaccharide/gamma interferon (LPS/IFNγ) activated cells since they can cause an aggressive immune response against the tumor. If the monocytes were to differentiate into interleukin 4 (IL4), IL10/transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) activated cells, it would trigger a regenerative response that would amplify the tumor growth.

The same applies to stem cell treatment, if the stem cells were to prematurely differentiate due to cell stress, losing their regenerative properties, it could jeopardize the treatment efficiency.

The proposition of tracking cells in vivo is not new, and several methods are currently available for this purpose. However, cell tracking using nuclear imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET) and SPECT, combined with anatomical CT imaging, has the unique advantage of providing non-invasive, long-term biodistribution in vivo in real time 25 . For example, a common compound used for long-term nuclear cell tracking with SPECT imaging is the radiotracer (111In)In-(oxinate)3, an intracellular labeling agent with a half-life of 2.8 days26–30.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of the microcatheter cell delivery technique on human bone marrow-derived monocytes and monocyte-differentiated macrophages. The macrophage subtypes were either stimulated with LPS/IFNγ or IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 to differentiate into activated macrophages. To assess the effects of radiolabeling and delivery procedures on cells, we investigated the phagocytotic function and expression of phenotypic markers in both pre-radiolabeling and post-radiolabeling as well as pre-catheter and post-catheter passage. We further investigated the retention and possible adverse effects of IA administration of activated cells in healthy rabbit brains.

Materials and Methods

Cell Preparation

Human monocytes and macrophages were isolated from buffy coats donated by healthy volunteers (Clinical Immunology and Transfusion Medicine Department of Karolinska Institute, Sweden) (Ethical approval Dnr: 9328-2019), according to a previous publication 31 . Cells were purified from the peripheral blood layer of mononuclear cells (PBMC) using Ficoll-Hypaque separation (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Monocytes were isolated from the PBMC using a CD14+ Selection Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The human monocytes were further differentiated into macrophages in the presence of M-CSF (50 ng/ml) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and cultured for 6 days. Separate fractions of the human monocyte-differentiated macrophages were stimulated with either LPS/IFNγ or IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN) for 24 h as previously described 32 . All subtypes were analyzed with FACS for surface expression of immune markers.

Cell

Radiolabeling of human macrophages with Indium (111In)In-(oxinate)3 was performed according to the product description of lymphocyte labeling (Mallinckrodt Medical, London, UK) 33 . Briefly, 37 MBq (111In)In-(oxinate)3 in Tris buffer was added to the cells (27–30 × 106 cells, 1.3–1.2 Bq/cell) in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) suspension. The cells were incubated for 20 min in a humidity chamber at 37°C, and the cells were gently mixed every 10 min. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with PBS (0.5 mL of 0.5 M PBS) at 1,000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in warm PBS. Supernatants and cell pellets were measured for radioactivity in a dose calibrator (Capentec CRC-15R Dose Calibrator, ALT, New London, CT) to determine cell labeling efficiency. Cell viability was measured with trypan blue staining and analyzed using a Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher, Boston, MA). Cellular retention has previously been evaluated34–36.

An Endovascular Catheter Passage In Vitro

Triplets of all cell types (2.4 ± 1.1 × 106 cells) suspended in 1 ml PBS were slowly passed through a 1.2 F microcatheter (Magic; Balt Extrusion, Montmorency, France), mimicking an approximately 4–8-minute in vivo injection, the catheter being washed with PBS after each cell passage. All unlabeled cell types were analyzed before and after passing through the microcatheter (Fig. 1). After the initial catheter passage, all cell types were then radiolabeled with (111In)In-(oxinate)3, and the procedure of catheter passage was repeated with analysis before and after passage through the catheter. This procedure provided data on all cell lines, both unlabeled pre-catheter and post-catheter passage and radiolabeled pre-catheter and post-catheter passage (Fig. 1). Cell samples were analyzed for (i) phenotype surface antigen expression, (ii) phagocytotic ability by flow cytometry, and (iii) viability by trypan blue staining.

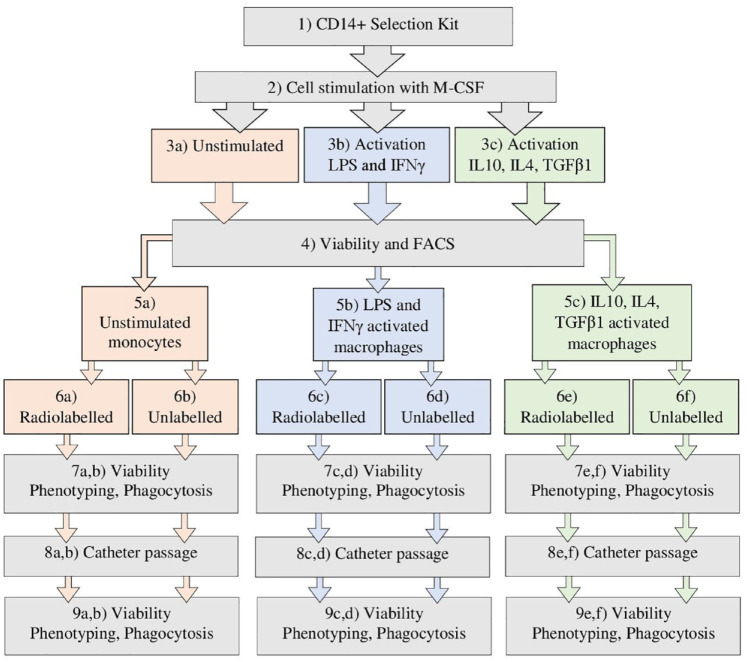

Figure 1.

A step-by-step graphic chart over the in vivo validation process of the radiolabeling and catheter passage of unstimulated monocytes, LPS/IFNγ or IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated macrophages.

Phenotype and Phagocytosis by Flow Cytometry

Cell phenotypes were analyzed with an antibody panel design to differentiate between the cell types CD14-FITC, CD16-APC-H7, CD86-BV421, CD163-PE, and CD206-APC (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (Table 1). The unstimulated M0 phenotype corresponds to a positive expression of CD14++, CD86++, and CD163+. The LPS/IFNγ activated cells phenotype shows a positive expression of CD14++, CD86+, CD163+, and CD206+. Finally, the IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells show a positive expression on CD14++ and CD206++. Phagocytosis was quantified by the uptake of Dextran Alexa Fluor™ 647 (Thermo Fisher, Boston, MA). Dextran and antibodies were added to samples of approximately 0.6–1 × 105 labeled/unlabeled, pre-catheter/post-catheter cells in 100 µl PBS and subsequently incubated at either 37°C with Dextran or 4°C with antibodies for 30 min. Samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer (Guava HT12®, Merck, Rahway, NJ) and software (Guava HT12®, Merck easyCyt system). The cellular morphology of cell size and intracellular structure was evaluated by forward scatter (FSC) and sideway scatter (SSC).

Table 1.

An Overview of the Antigens Used to Evaluate the Phenotypic Expression of Unstimulated Monocytes and Activated Macrophages and Their Role in Immune Cell Functions.

| Antigen role in immune cell functions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Unstimulated | LPS/IFNγ | IL4/IL10/TGFβ | Target receptor purpose and response |

| CD14 | ++ | ++ | ++ | Aka: lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Detects bacterial antigens 37 . |

| CD16 | – | – | – | Aka: FcγRIIIa receptor, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Positive for large granular lymphocytes T-cells and NK cells. The low expression on monocytes and macrophages 38 . |

| CD86 | ++ | + | – | Aka: B7-2. Antigen-presenting cells for costimulatory signals necessary for T-cell activation. Positive on monocytes and LPS/IFNγ activated macrophages 39 . |

| CD163 | + | + | – | Aka: hemoglobin scavenger receptor. The macrophage-specific protein responsible for inflammation type 1, binds TNF-α. Positive on monocytes and LPS/IFNγ activated macrophages40,41. |

| CD206 | – | + | ++ | Aka: mannose receptor and C-type lectin, identify pathogens, active in type 2 immune response. Positive for IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 macrophages 42 . |

Levels of expression are divided into high (++), low (+), and minimal expression (–). LPS/IFNγ: lipopolysaccharide/gamma interferon; IL4: interleukin 4; IL10: interleukin 10; TGFβ1: transforming growth factor beta 1.

Animal Model

Eight female New Zealand White rabbits weighing 3.5 ± 0.3 kg were used in the study (Ethical approval Dnr: 5.2.18-15846/17) due to their large size and availability. Animals were housed 7–10 days prior to experimental day and fed food and water ad libitum. General anesthesia was induced by subcutaneous (SC) injection of 0.5 ml/kg Hypnorm (fentanyl citrate 0.315 mg/ml, fluanisone 10 mg/ml; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Belgium) combined with 5 mg diazepam (Actavis Group PTC, Iceland). Rabbits were intubated and connected to a servo ventilator. Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved by continuous intravenous (IV) infusion of Propofol-Lipuro (Braun AB, Sweden) at a rate of 20 ml/h and IV injection of 0.1 ml Hypnorm every 30 min.

All large animal angiography and endovascular interventions were performed under sterile conditions using Philips XD20 angiographical equipment (Philips medical system, the Netherlands). Visipaque 270 contrast agent (GE Healthcare, USA) was used in all angiography applications.

A 4F pediatric short introducer (Terumo Medical Corporation, Japan) was inserted into the femoral artery through a surgical incision, and a 4F catheter (Vertebral; Cook, USA) was navigated to the common carotid artery. A 1.2F microcatheter (Magic; Balt Extrusion, France) was then navigated to the internal carotid artery, and in that position, 20 million cells were infused at a concentration of 10,000 cells per microliter with a total injection time of 8 min (n = 3 for LPS/IFNγ activated cells and n = 3 for IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells). Digital subtraction angiography was performed following the injection and was not repeated at later time points.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained within 15 min of cell administration for all animals, and repeated after 24 h for the rabbits that received [111In]In-(oxinate)3 labeled cells. The MRI was conducted at 9.4 T in a horizontal magnet with a 30-cm-wide opening (Agilent Inc, UK). A 20-cm gradient insert, capable of generating 30 G/cm gradient fields, was used together with a birdcage coil of 150 mm inner diameter for transmission (Rapid Biomedical, Germany).

In a supine position, the rabbits were placed in the MRI-compatible bed designed for obese rats (Rapid Biomedical, Germany). The head was secured in a semi-circular surface coil designed for rat heart imaging (Rapid Biomedical, Germany), which was used for signal reception. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) was accomplished through a fat-suppressed spin-echo sequence [TR 2,900 ms, TE 22.96 ms, next 1, matrix size 128 × 96 field of view (FOV) 60 × 60 mm2, 27 contiguous slices of 1 mm thickness] with diffusion weighting gradients (18.64 G/cm, 23.8 ms, gradient separation 12.9 ms, b-value 951.8 s/mm2) applied along 12 directions and 2 reference images, where the diffusion weighting gradient intensities were set to 0. T1-weighted images were obtained using a fat-suppressed spin-echo sequence (TR 700 ms, TE 15.12 ms FOV 60 × 60 mm2, matrix size 192 × 192, 14 slices 1 mm with 1 mm gap, repeated in 2 min 17 s, repeated with the slice package translated 1 mm in the slice select direction to keep TR short to have T1 weighting and have complete coverage). Images with higher spatial resolution were acquired using a fast spin-echo 3D sequence (TR 800 ms, ETL 8, zero 4, effective TE 31.18 ms, FOV 51.2 × 51.2 × 51.2 mm3 matrix 256 × 192 × 192).

SPECT/CT Imaging

Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) was obtained after 24 h post-injection of the two animals that received [111In]In-(oxinate)3 labeled cells. The SPECT/CT system (Symbia T; Siemens GmbH, Germany) consisted of a dual-head variable-angle γ-camera equipped with low-energy high-resolution collimators and a multislice spiral CT component optimized for rapid rotation. The SPECT acquisition (128 × 128 matrix, 81 frames, 45 s/frame) was performed using 4.5° angular steps in a 50-s time frame. For CT (158 kV, 210 mA, B50s kernel, 512 × 512 matrix), 0.75-mm slices were obtained. After reconstruction, SPECT images were corrected for attenuation and scatter. SPECT and CT axial 5-mm slices were generated using Hermes Gold 450 (Hermes Medical Solution, Sweden). Images were then analyzed with OsiriX imaging software (OsiriX Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Statistical significance for paired samples was calculated using the Student t-test and for repeated measurement, the repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA) method with Bonferroni corrections was used. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statically significant.

Results

Cell and Cell Viability

Labeling efficiencies of the macrophage subtypes with (111In)In-(oxinate)3 were unstimulated cells 51.0 ± 2.9% (3.3 ± 1.3 × 106 cells) (n = 3), the LPS/IFNγ activated cells 57.7 ± 0.6% (1.5 ± 0.14 × 106 cells) (n = 3), and the IL-4/IL-10/TGFβ activated cells 71.1 ± 0.5% (2.4 ± 0.12 × 106 cells) (n = 3), respectively. Yielding a final radioactive cell dosage to unstimulated cells of 6.3 ± 0.7, LPS/IFNγ activated cells of 5.0 ± 0.4, and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells received a dose of 2.9 ± 0.6 Bq/cell, respectively. The viability was initially high for unstimulated cells (94.0 ± 0.8%) and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells (96.3 ± 0.5%), while LPS/IFNγ activated started with a slightly lower viability (85.7 ± 5.4). The complete procedure of radiolabeling and catheter passage resulted in a decrease in viability for all cell lines. Unactivated cell viability decreased by 5.0 ± 3.1%, LPS/IFNγ activated cells by 10.0 ± 8.2%, and IL-4/IL-10/TGFγ activated cells by 2.1 ± 0.8%. However, there was no significant difference in viability before and after radiolabeling and catheter passage for any cell types (Table 2).

Table 2.

Viability of Cells Measured During the Procedure of (111In)In-(oxinate)3 Radiolabeling and Catheter Passage Using Trypan Blue Staining Providing the Percentage of Live Cells.

| Cell viability during radiolabeling and catheter passage | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstimulated cells | LPS/IFNγ activated cells | IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells | |

| Control pre-catheter | 94.0 ± 0.8% | 85.7 ± 5.4% | 96.3 ± 0.5% |

| Control post-catheter | 94.7 ± 1.9% | 81.7 ± 2.5% | 95.7 ± 2.6% |

| (111In)In-(oxinate)3 pre-catheter | 91.7 ± 3.4% | 76.7 ± 5.9% | 95.7 ± 1.2% |

| (111In)In-(oxinate)3 post-catheter | 89.3 ± 3.4% | 76.7 ± 2.6% | 94.3 ± 0.5% |

| P-value | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Samples size | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 3 |

Measurements were obtained on unlabeled controls before and after catheter passage, as well as radiolabeled cells before and after catheter passage. Data are presented as mean value (%) ± SD, statistical analysis calculated by repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA), and statistical significance set to a p-value of 0.05. LPS/IFNγ: lipopolysaccharide/gamma interferon; IL4: interleukin 4; IL10: interleukin 10; TGFβ1: transforming growth factor beta 1.

Phagocytosis

The procedure of radiolabeling and catheter passage had no significant effect on phagocytosis of unstimulated and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells, but a weakly significant increased phagocytosis of 62 ± 20% (p = 0.049) was recorded in LPS/IFNγ activated cells. Catheter passage significantly affected the surface antigen expression for all cell types. Unstimulated and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells decreased by 4.7 ± 1.6% (p = 0.06) and 37 ± 27% (p = 0.03), respectively. For the LPS/IFNγ activated cells, the phagocytosis increased significantly with 74 ± 10% (p = 0.007) (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Table 3.

The Percental Change in Antigen Expression and p-Values for Phenotype Analysis and Phagocytosis Function of Unstimulated Monocytes, LPS/IFNγ, or IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 Activated Cells Measured During Each Step in the Procedure of Radiolabeling With (111In)In-(Oxinate)3 and Catheter Passage.

| Change in antigen expression and phagocytosis (%) P-values for antigen expression and phagocytosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstimulated monocytes | CD14 | CD16 | CD86 | CD163 | CD206 | Dextran |

| Catheter passage P-value |

+12 ± 6.1% 0.095 |

–17 ± 2.4% 0.13 |

+25 ± 3.6% 0.012* |

–5 ± 18% 0.65 |

+12 ± 28% 0.73 |

–4.7 ± 1.6% 0.011* |

| Radiolabeling P-value |

+38 ± 16% 0.065 |

–52 ± 12% 0.030* |

+2.1 ± 9.7% 0.75 |

+185 ± 25% 0.026* |

+26 ± 45% 0.54 |

+8.1 ± 7.6% 0.13 |

| Complete procedure P-value |

+45 ± 12% 0.007* |

–32 ± 4.1% 0.004* |

+18 ± 8.0% 0.05 |

+150 ± 26% 0.003* |

+24 ± 32% 0.53 |

+1.3 ± 7.8% 0.18 |

| LPS/IFNγ activated cells | CD14 | CD16 | CD86 | CD163 | CD206 | Dextran |

| Catheter passage P-value |

+5.2 ± 5.7% 0.33 |

+9.6 ± 7.2% 0.18 |

+8.1 ± 9.9% 0.37 |

–18 ± 4.9% 0.037* |

–30 ± 2.5% 0.009* |

+74 ± 10% 0.007* |

| Radiolabeling P-value |

+11 ± 6.4% 0.14 |

–17 ± 11% 0.19 |

–15 ± 2.9% 0.024* |

+77 ± 4.5% 0.002* |

–21 ± 11% 0.12 |

+78 ± 22% 0.054 |

| Complete procedure P-value |

–3.2 ± 4.8% 0.39 |

+0.14 ± 8.0% 0.94 |

–17 ± 3.8% 0.003* |

+70 ± 5.9% <0.001** |

–32 ± 8.8% 0.041* |

+62 ± 20% 0.049* |

| IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells | CD14 | CD16 | CD86 | CD163 | CD206 | Dextran |

| Catheter passage P-value |

+6.4 ± 19% 0.78 |

–7.6 ± 0.4% 0.11 |

–10 ± 9.6% 0.30 |

+71 ± 59% 0.11 |

+3.5 ± 7.3% 0.57 |

–37 ± 27% 0.030* |

| Radiolabeling P-value |

+5.5 ± 10% 0.59 |

–68 ± 1.0% 0.002* |

–20 ± 5.5% 0.049* |

+41 ± 50% 0.33 |

–10 ± 1.9% 0.021* |

+5.8 ± 20% 0.073 |

| Complete procedure P-value |

–1.9 ± 17% 0.87 |

–57 ± 6.5% <0.001** |

–34 ± 3.7% 0.002* |

+22 ±45% 0.39 |

–42 ± 7.8% 0.61 |

–10 ± 22% 0.98 |

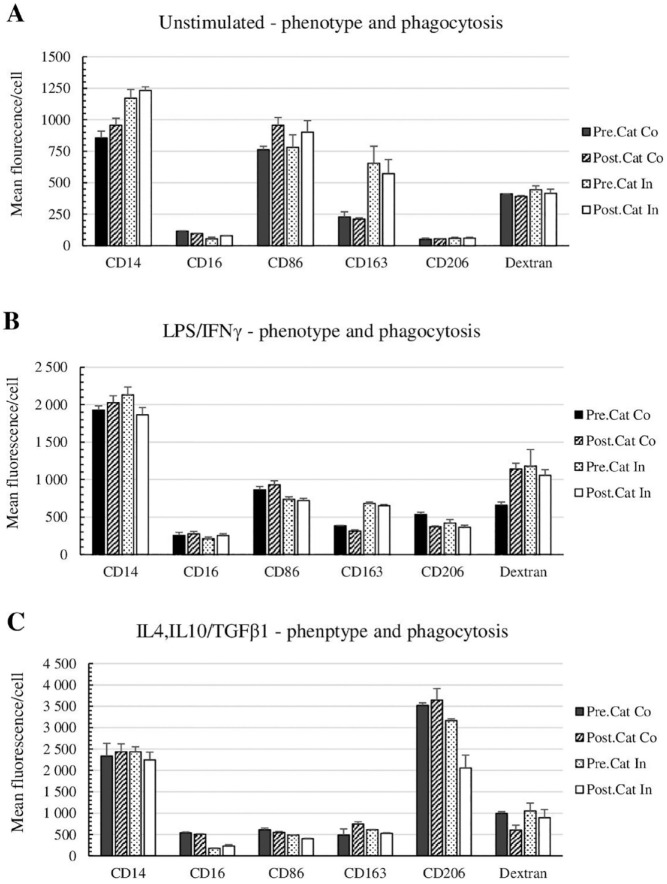

Figure 2.

Phenotype analysis and phagocytosis function of (A) M0, (B) LPS/IFNγ activated cells, and (C) IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells measured during each step of the radiolabeling procedure with (111In)In-(oxinate)3 and catheter passage. An antibody panel of CD14, CD16, CD86, CD163, and CD206 for phenotype and Dextran Alexa 640 for phagocytosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis was calculated with the Student t-test or rm-ANOVA. Data were considered statistically significant at a p-value <0.05, values under 0.05 are marked as *, and those under 0.001 are marked as <0.001**. P-values are presented in Table 3.

Each procedure is divided into three analysis groups; “Catheter passage” unlabeled cells before and after catheter passage; “Radiolabeling” unlabeled cells compared with radiolabeled cells; “Complete procedure” unlabeled cells versus radiolabeled cells after catheter passage, to evaluate the whole procedure of radiolabeling and cell delivery in vivo. An antibody panel of CD14, CD16, CD86, CD163, and CD206 for phenotype and Dextran for phagocytosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis was calculated with the Student t-test or rm-ANOVA. Data were considered statistically significant at a p-value <0.05, values under 0.05 are marked as *, and those under 0.001 are marked as <0.001**.

LPS/IFNγ: lipopolysaccharide/gamma interferon; IL4: interleukin 4; IL10: interleukin 10; TGFβ1: transforming growth factor beta 1.

Phenotyping

Monocytes naturally have a lower antigen expression and are easily differentiated through activation. The complete procedure of radiolabeling and catheter passage resulted in a substantial increase in antigen expression on unstimulated monocytes, including CD14 of 45 ± 12% (p = 0.007) and CD163 of 150 ± 26% (p = 0.003), and a slight increase of CD86 with 18 ± 8.0% (p = 0.05), while CD16 decreased significantly with 32 ± 4.1% (p = 0.004) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). However, the main reason for the change in antigen expression was caused by radiolabeling. Catheter passage only significantly affected the CD86 expression with a 25 ± 3.6% decrease (p = 0.012).

This procedure had no significant effect on LPS/IFNγ activated cell expression of CD14 and CD16 but caused a significant decrease of CD86 levels with 17 ± 3.8% (p = 0.003) and of CD206 expression with 32 ± 8.8% (p = 0.04) for which the catheter passage had a large impact. Only CD163 levels were substantially increased by 70±5.9% (p < 0.0001), solely caused by radiolabeling.

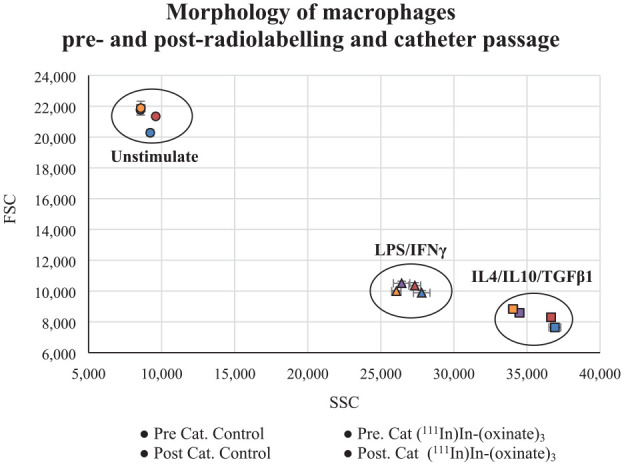

The overall procedure had a small impact on the phenotype expression for IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells. There were no significant changes in the expression of CD14, CD163, and CD206 (Table 3 and Fig. 2). There was, however, a significant loss in the expression of CD16 (57 ± 6.5%, p ≤ 0.0001) and CD86 (34 ± 3.7%, p = 0.002) primarily caused by radiolabeling. Although IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells have a naturally lower expression of both CD16 and CD86, it could be considered within the expression range of the phenotype. All cell types stayed within their respective range of FSC (density) and SSC (size) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry parameters sideway scatter (SSC) and forward scatter (FSC). SSC represents the intracellular structures providing information on the internal complexity of the cells. The FSC represents the cell size. Combined they provide the basic information of the cell morphology of unstimulated, LPS/IFNγ, or IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells. Values are presented as the mean SSC/FSC value for each step in the process; pre-catheter or post-catheter passage for controls and (111In)In-(oxinate)3 labeled cells.

Cell Transplantation

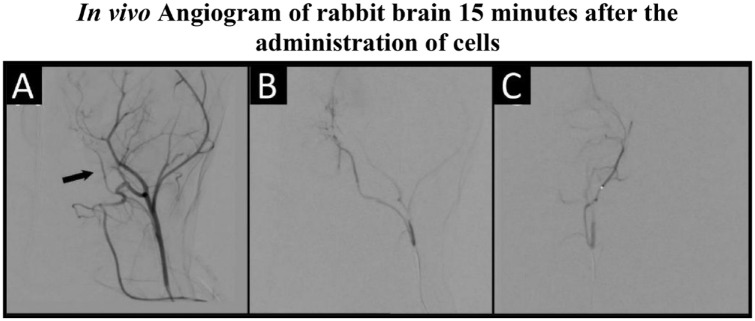

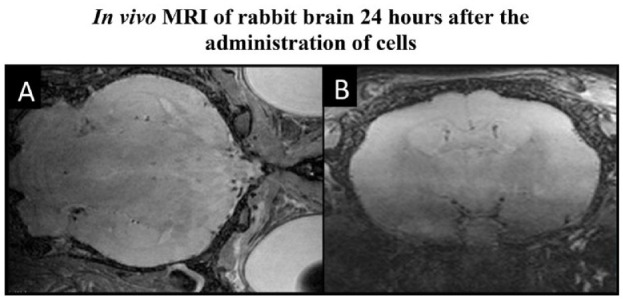

Surgical anesthesia and intubation were successfully achieved in all animals. Endovascular access was established in all animals. No acute adverse events occurred during endovascular navigation to the internal carotid artery. As verified by digital subtraction angiography, no thromboembolic events occurred during or after IA cell administration (Fig. 4). Animals were continuously monitored during infusion using a gamma counter. Fifteen minutes after cell administration, no radiotracer signal could be detected in the brain. Additionally, after 24 h, MRI further confirmed the absence of acute infarcts evaluated by DWI (n = 3 for LPS/IFNγ activated cells and n = 3 for IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells) (Fig. 5). The six animals receiving non-radioactive cells were then sacrificed after the completion of imaging on day 0.

Figure 4.

A representative digital subtraction angiogram taken 15 min after administration of LPS/IFNγ activated cells. Images are taken in the following order: the right internal carotid artery (ICA) (arrow, A) followed by selective ICA arteriograms in lateral (B) and frontal (C) planes.

Figure 5.

Volumetric MRI images, (A) T2- and (B) Diffusion-weighted, were taken 24 h post-cell administration of LPS/IFNγ activated cells through the catheter to rabbit brain. The illustration shows no adverse events caused by the procedure.

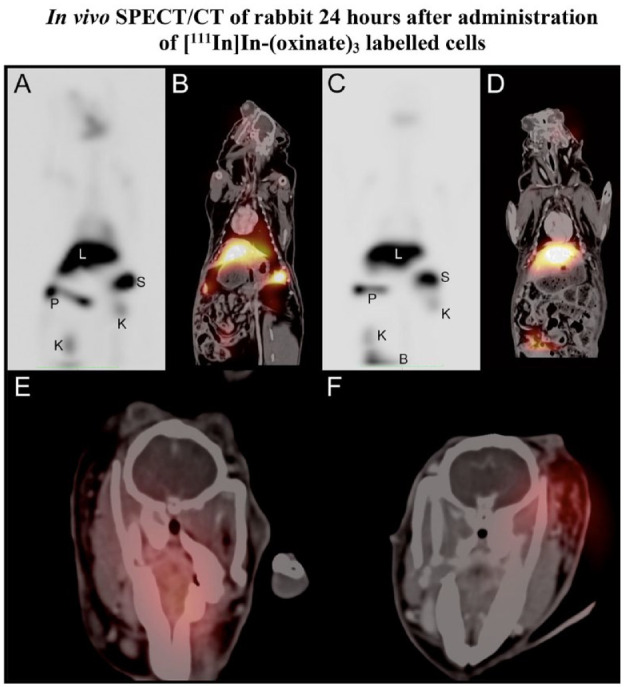

An additional two animals received either LPS/IFNγ activated cells (n = 1) or IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells (n = 1). The same procedure of angiography and MRI was conducted at the time of injection. These animals were then extubated and allowed to return to their cages. After 24 h, animals were sedated, intubated, and imaged by MRI and SPECT/CT. The MRI was performed using a high-resolution T2-weighted volumetric scan (voxel size 200 × 267 × 267 µm) in addition to DWI. The gamma counter showed a quick clearance of signal from the brain after cell administration. After 24 h, no signal could be detected in the brain with SPECT/CT imaging, indicating a complete passage through the brain without retention of administered cells (Fig. 6). The majority of the SPECT signal was detected in the liver, the spleen, and to some extent, the kidneys and bladder. No signal was detected in the lungs.

Figure 6.

SPECT coronal maximum intensity projections for the full rabbit scan 24 h following administration of LPS/IFNγ activated cells (A) and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells (C). Liver indicated by L, spleen by S, pancreas by P, kidneys by K and in panel C, and the top of the bladder marked by B. Coronal SPECT-CT fusion images demonstrating the colocalization of signal for LPS/IFNγ activated cells (B) and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells (D) to organs. Axial SPECT-CT fusion images demonstrate the lack of signal from the brain parenchyma for both LPS/IFNγ activated cells (E) and IL4, IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells (F), and the visible signals are due to accumulations in glands.

Discussion

Cell-based therapy administered by IV injection is the golden standard for many different types of treatment, such as cancer and autoimmune diseases5–11. Nonetheless, several treatments suffer from side effects and unpredictable treatment efficiency due to off-target accumulation of cells when using IV or IA. Other types of injection for a more direct tissue delivery have been evaluated for several diseases. Cell delivery by SC has been used to treat Diabetes type 1, intramuscular (IM) to treat amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and post-organ transplantation treatment with intraosseous (IO) injections to mention a few. Although this avoids the passage through the lungs and liver, other limitations emerge. It has been shown to increase the risk of an aggressive immune response in the sight of injection as well and the cells’ capacity for tissue penetration and mobilization is limited compared with IV and IA injections. The delivery of cells into enclosed tissues shows a high risk of cell clogging and a high level of cell death43–46. By using alternative administration methods with targeted cell delivery via an IA catheter, it is possible to avoid accumulation in the lungs and liver, hence increasing the proportion of cells reaching the target tissue. However, this delivery system needs to be evaluated to ensure that the procedure itself does not damage the cells or cause severe damage to brain tissue due to the invasive penetration of the catheter. In this study, we evaluated the effects on phenotypic expression and phagocytic function of unstimulated monocytes and activated macrophages after radiolabeling with (111In)In-(oxinate)3 followed by catheter passage in vitro. Subsequently, we evaluated the safety by administering cells in vivo to rabbit brains, the animals being assessed using SPECT and MRI imaging to locate the cells and to identify potential complications from the catheter navigation.

The procedure of radiolabeling and catheter passage entailed no significant difference in cell viability for any of the cell types. One of the batches of LPS/IFNγ activated cells showed a slightly lower viability compared with the other cell types, hence the higher SD. This is, however, not unlikely when handling immune cells due to their sensitivity, therefore, there was no need to exclude them from the study. The radioactive cellular retention of [111In]In-(oxinate)3 has previously been reported and has shown that [111In]In-(oxinate)3 can be unpredictable. In general, [111In]In-(oxinate)3 labeled cells retain 60–85% of the radioactivity after 24–48 h34–36. What all studies disclose is that retention is determined by the health of the cells, hence with high cell viability the radioactive efflux is minimized.

Monocytes can differentiate into the desired activated macrophage type when exposed to different stimuli; LPS/IFNγ which induces a primarily pro-inflammatory activation phenotype or IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 which induces a primarily immunomodulatory activation phenotype (Table 1).

The antigen expression panel for surface phenotyping was designed to distinguish the subtype-specific antigen expression (Table 1). The cell line-specific antigen CD14 is expressed on all macrophage subtypes, and its primary function is to detect and bind foreign antigens (bacteria, viruses, and parasites) 37 . CD16 has an overall low expression on monocytes and macrophages, separating them from other CD16+ cells such as large granular lymphocytes, T-cells, and NK cells 38 . CD86 is a T-cell activation antigen highly expressed on LPS/IFNγ activated cells and moderately expressed on unstimulated cells. The IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells have a low expression of CD86 and CD16339–41. The inflammation type 2 associated antigen CD206 is activated explicitly by parasites and is therefore solely expressed on IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 cells 42 . The unstimulated cells generally have lower surface antigen expression and hence reduced phagocytic abilities.

The unstimulated cells were strongly affected by radiolabeling and catheter passage, with a significant change in all surface antigen expressions except for CD206. The shift in CD163 levels is a strong indicator of inflammatory activation40,41. The lack of increase in CD206 also supports that the unstimulated cells differentiated toward a pro-inflammatory LPS/IFNγ activated phenotype 42 . The high increase in CD14, although usually expressed on unstimulated cells, also points toward differentiation to activated macrophage phenotypes 37 . Unstimulated cells that passed through the catheter showed a significant decrease in phagocytic function, yet radiolabeled cells showed an increasing effect; however, the completed procedure had no significant effect on phagocytosis. The catheter passage had no significant effect on IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 cells, while the radiolabeling procedure had apparent adverse effects on these cells. The morphological appearance of unstimulated and IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 activated cells have an elongated shape, hence a larger variety in SSC and FSC, while LPS/IFNγ activated cells have a rounded shape, hence lower deviations 47 .

The standard procedure to administer transplanted cells is IV infusions and has proven very successful in numerous treatments due to the quick biodistribution through the bloodstream and extensive tissue penetration. However, this strength is also a weakness. A particular challenge during cell migration via this route is the passage through the lungs, followed by the high blood flow through the liver. Indeed, several preclinical studies of nuclear cell tracking in vivo following IV injection have demonstrated that some cells linger in the lung and have high accumulation in the liver and spleen. Which subsequentially increased organ dosage, a lower target-to-background ratio and fewer cells available to migrate to the intended tissue18,33,48–53. A portion of the liver and spleen signal is caused by dead cells and radiotracer leakage, as discussed above. Furthermore, not only does the off-target accumulation reduce the treatment efficacy, administration of stem cells and immune cells such as CAR T-cells has been shown to cause severe side effects such as graft-versus-host disease4,54–56. Hence, developing and evaluating the alternative delivery system of IA catheter delivery would substantially contribute to cell-based therapy, especially when the target tissue is difficult to access, like the brain, or is in proximity to the lungs or liver.

We further performed in vivo experiments to establish safety data for the interaction between intra-arterially administered activated cells and the healthy brain parenchyma. As no cell retention could be visualized in the brain by SPECT/CT after 24 h, the epithelium of the healthy brain does not attract the activated cells. The signal was mainly detected in the liver and spleen which was expected since the cells migrated threw the artery and first reached the liver instead of the lungs. Immediate side effects such as thromboembolism were excluded by the normal appearance of the arterial tree on DSA following cell administration and confirmed by lack of acute infarction on MRI after 24 h. In addition, there were no delayed side effects such as cerebral infarcts or edema, on high-resolution 3D T2-weighted images at 24 h when using the cell transplantation parameters in this study. This is essential baseline information for further clinical translation of macrophage cell transplantation to the injured central nervous system.

Conclusion

IA selective macrophage injection by microcatheter technique to the brain vasculature does not cause ischemic or other adverse events and the intact blood–brain barrier of the normal brain prevents cell diapedesis. Radiolabeling of cells in vitro and administration by a catheter in vivo caused different effects on cell activation phenotypes. Both radiolabeling and catheter passage showed significant changes in all cell types. Despite this change, both LPS/IFNγ activated cells and IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 macrophages stay within their natural phenotypic pattern range. We propose that they are thus suitable candidates for targeted administration via IA transplantation. The unstimulated monocytes showed signs of activation, especially toward LPS/IFNγ activated cells. As unstimulated monocytes are highly sensitive and easily activated and, from this study, are not an appropriate choice for radiolabeling and cell transplantation using this administration technique. The consequences of an increased inflammatory response at the target site should be considered when administering immune cells. Monocytes that undesirably differentiate into LPS/IFNγ activated cells can cause tissue damage, while IL4/IL10/TGFβ1 cells will trigger tissue repair. These effects can both be desirable or cause severe consequences depending on the therapeutic application.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: All animal studies were conducted according to Karolinska Institutet guidelines for animal experiments on small rodents and rabbits (Dnr: 5.2.18-15846/17). The regional ethics committee approved the studies for animal research at the Karolinska University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden). In addition, the regional ethical review board approved the differentiation of human macrophages at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr: 9328-2019).

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article contain studies with human tissue and animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was supported by the Söderberg Foundations, Cancerfonden, Barncancerfonden, Swedish Medical Research Council, and MedTechLabs. In addition, we thank Pellina Jansson and Johanna Doshé for their excellent technical assistance.

ORCID iD: Ida Friberger  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6770-7380

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6770-7380

References

- 1. Lukawska JJ, Livieratos L, Sawyer BM, Lee T, O’Doherty M, Blower PJ, Kofi M, Ballinger JR, Corrigan CJ, Gnanasegaran G, Sharif-Paghaleh E, et al. Real-time differential tracking of human neutrophil and eosinophil migration in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(1). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/23953710/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Puncher MRB, Blower PJ. Autoradiography and density gradient separation of technetium-99m-exametazime (HMPAO) labelled leucocytes reveals selectivity for eosinophils. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21(11):1175–82. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/7859768/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tavaré R, Sagoo P, Varama G, Tanriver Y, Warely A, Diebold SS, Southworth R, Schaeffter T, Lechler RI, Razavi R, Lombardi G, et al. Monitoring of in vivo function of superparamagnetic iron oxide labelled murine dendritic cells during anti-tumour vaccination. Plos One. 2011;6(5). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/21637760/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrett AJ, Battiwalla M. Relapse after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3(4):429–41. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/21083034/ [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mason C, Dunnill P. A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2008;3(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenberg SA. IL-2: the first effective immunotherapy for human cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):5451–58. https://www.jimmunol.org/content/192/12/5451 [accessed 2022 Oct 19]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Braunschweig I, Oluwole OO, Siddiqi T, Lin Y, Timmerman JM, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(26):2531. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5882485/ [accessed 2022 Oct 19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mackensen A, Müller F, Mougiakakos D, Böltz S, Wilhelm A, Aigner M, Völkl S, Simon D, Kleyer A, Munoz L, Kretschmann S, et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy for refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Medicine. 2022;28(10):2124–32. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-02017-5 [accessed 2022 Oct 19]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erkers T, Nava S, Yosef J, Ringdén O, Kaipe H. Decidual stromal cells promote regulatory T cells and suppress alloreactivity in a cell contact-dependent manner. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(19):2596–2605. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/23701127/ [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sato N, Stringaris K, Davidson-Moncada JK, Reger R, Adler SS, Dunbar C, Choyke PL, Childs RW. In vivo tracking of adoptively transferred natural killer cells in rhesus macaques using 89 zirconium-oxine cell labeling and pet imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2573–81. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32034075/ [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dazzi F, Van Laar JM, Cope A, Tyndall A. Cell therapy for autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(2). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17367542/ [accessed 2022 Oct 19]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41(1):49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanazawa M, Ninomiya I, Hatakeyama M, Takahashi T, Shimohata T. Microglia and monocytes/macrophages polarization reveal novel therapeutic mechanism against stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(10):2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Olingy CE, Dinh HQ, Hedrick CC. Monocyte heterogeneity and functions in cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106(2):309–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aizik G, Grad E, Golomb G. Monocyte-mediated drug delivery systems for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2018;8(4):868–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borlongan CV. Concise review: stem cell therapy for stroke patients: are we there yet? Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8(9):983–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lundberg J, Le Blanc K, Söderman M, Andersson T, Holmin S. Endovascular transplantation of stem cells to the injured rat CNS. Neuroradiology. 2009;51(10):661–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arnberg F, Lundberg J, Olsson A, Samén E, Jaff N, Jussing E, Dahlén U, Nava S, Axelsson R, Ringdén O, Kaipe H, et al. Intra-arterial administration of placenta-derived decidual stromal cells to the superior mesenteric artery in the rabbit: distribution of cells, feasibility, and safety. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(2):401–10. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/25976072/ [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li K, Vela D, Migliati E, da Graca Cabreira M, Wang X, Buja LM, Perin EC. Pilot study of endovascular delivery of mesenchymal stromal cells in the aortic wall in a pig model. Cell Transplant. 2021;30:3009636897211010652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ng NN, Thakor AS. Locoregional delivery of stem cell-based therapies. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(547):eaba4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee KS, Santagostino SF, Li D, Ramjit A, Serrano K, Ginsberg MD, Ding B, Sen Rafii S, Madoff DC. Catheter-directed intraportal delivery of endothelial cell therapy for liver regeneration: a feasibility study in a large-animal model of cirrhosis. Radiology. 2017;285(1):114–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson NR, Minutolo NG, Gill S, Klichinsky M. Macrophage-based approaches for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2021;81(5):1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheng P, Li S, Chen H. Macrophages in lung injury, repair, and fibrosis. Cells. 2021;10(2):436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mills CD. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32(6):463–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lappalainen RS, Narkilahti S, Huhtala T, Liimatainen T, Suuronen T, Närvänen A, Suuronen R, Hovatta O, Jolkkonen J. The SPECT imaging shows the accumulation of neural progenitor cells into internal organs after systemic administration in middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440(3):246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu CH, Chen YA, Ke CC, Chiu SJ, Chen CC, Hsieh YJ, Yang BH, Liu RS. Preclinical characterization and in vivo imaging of 111in-labeled mesenchymal stem cell–derived extracellular vesicles. Mol Imaging Biol. 2021;23(3):361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahevas M, Van Eeckhoudt S, Moulis G, Limal N, Languille L, Bierling P, Dossier A, Duriez F, Galicier L, Morin AS, Tamburini J, et al. Autologous111Indium-oxinate-labelled platelet sequestration study in patients with immune thrombocytopenia treated by thrombopoietin receptor-agonists. Br J Haematol. 2019;186(3):e44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elgazzar AH, Dannoon S, Sarikaya I, Farghali M, Junaid TA. Scintigraphic patterns of indium-111 oxine-labeled white blood cell imaging of gram-negative versus gram-positive vertebral osteomyelitis. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(5):415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weeks AJ, Blower PJ, Lloyd DR. p53-dependent radiobiological responses to internalised indium-111 in human cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40(1):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zamora E, Valdivia AY, Kumar A, Chun KJ. 111In-oxine-WBC SPECT/CT of lumbosacral facet joint septic arthritis. Clin Nucl Med. 2021;46(1):e54–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang J, Cao Z, Zhang XM, Nakamura M, Sun M, Hartman J, Harris RA, Sun Y, Cao Y. Novel mechanism of macrophage-mediated metastasis revealed in a zebrafish model of tumor development. Cancer Res. 2015;75(2):306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mia S, Warnecke A, Zhang XM, Malmström V, Harris RA. An optimized protocol for human M2 macrophages using M-CSF and IL-4/IL-10/TGF-β yields a dominant immunosuppressive phenotype. Scand J Immunol. 2014;79(5):305–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roca M, De Vries EFJ, Jamar F, Israel O, Signore A. Guidelines for the labelling of leucocytes with 111In-oxine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(4):835. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2844966/ [accessed 2022 Nov 25). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blocklet D, Toungouz M, Kiss R, Lambermont M, Velu T, Duriau D, Goldman M, Goldman S. 111In-oxine and 99mTc-HMPAO labelling of antigen-loaded dendritic cells: in vivo imaging and influence on motility and actin content. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(3):440–47. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/12722741/ [accessed 2023 Aug 29]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nowak B, Weber C, Schober A, Zeiffer U, Liehn EA, Von Hundelshausen P, Reinartz P, Schaefer WM, Buell U. Indium-111 oxine labelling affects the cellular integrity of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(5):715–21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17096094/ [accessed 2023 Aug 29]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Man F, Khan AA, Carrascal-Miniño A, Blower PJ, de Rosales RTM. A kit formulation for the preparation of (89Zr).Zr(oxinate)4 for PET cell tracking: white blood cell labelling and comparison with (111In)In(oxinate)3. Nucl Med Biol. 2020;90–91:31–40. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32979725/ [accessed 2023 Aug 29]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Naeim F, Nagesh Rao P, Song SX, Grody WW. Principles of immunophenotyping. In: Atlas of Hematopathology. London: Elsevier Inc., 2013, pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cho D, Kim SK, Carson WE. NK cell-based immunotherapy for treating cancer: will it be promising. Korean J Hematol. 2011;46(1):3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delves PJ. The role of glycosylation in autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity. 1998;27(4):239–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Etzerodt A, Moestrup SK. CD163 and inflammation: biological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(17):2352–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maniecki MB, Etzerodt A, Moestrup SK, Møller HJ, Graversen JH. Comparative assessment of the recognition of domain-specific CD163 monoclonal antibodies in human monocytes explains wide discrepancy in reported levels of cellular surface CD163 expression. Immunobiology. 2011;216(8):882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Suzuki Y, Shirai M, Asada K, Yasui H, Karayama M, Hozumi H, Furuhashi K, Enomoto N, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y, Inui N, et al. Macrophage mannose receptor, CD206, predict prognosis in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geijo-Barrientos E, Pastore-Olmedo C, De Mingo P, Blanquer M, Gómez Espuch J, Iniesta F, Iniesta NG, García-Hernández A, Martín-Estefanía C, Barrios L, Moraleda JM, et al. Intramuscular injection of bone marrow stem cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a randomized clinical trial. Front Neurosci. 2020;14. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32265627/ [accessed 2023 Aug 28]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Preda MB, Lupan AM, Neculachi CA, Leti LI, Fenyo IM, Popescu S, Rusu EG, Marinescu CI, Simionescu M, Burlacu A. Evidence of mesenchymal stromal cell adaptation to local microenvironment following subcutaneous transplantation. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(18):10889–97. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32785979/ [accessed 2023 Aug 28]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yu M, Agarwal D, Korutla L, May CL, Wang W, Griffith NN, Hering BJ, Kaestner KH, Velazquez OC, Markmann JF, Vallabhajosyula P, et al. Islet transplantation in the subcutaneous space achieves long-term euglycaemia in preclinical models of type 1 diabetes. Nat Metab. 2020;2(10):1013–20. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32895576/ [accessed 2023 Aug 28]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. El-Halawani SM, Gabr MM, El-Far M, Zakaria MM, Khater SM, Refaie AF, Ghoneim MA. Subcutaneous transplantation of bone marrow derived stem cells in macroencapsulation device for treating diabetic rats; clinically transplantable site. Heliyon. 2020;6(5). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/32395661/ [accessed 2023 Aug 28]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McWhorter FY, Wang T, Nguyen P, Chung T, Liu WF. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(43):17253–58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24101477/ [accessed 2023 Oct 4]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chin BB, Nakamoto Y, Bulte JWM, Pittenger MF, Wahl R, Kraitchman DL. 111In oxine labelled mesenchymal stem cell SPECT after intravenous administration in myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24(11):1149–54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14569169/ [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Elster JL, Rathbone CR, Liu Z, Liu X, Barrett HH, Rhoads RP, Allen RE. Skeletal muscle satellite cell migration to injured tissue measured with 111In-oxine and high-resolution SPECT imaging. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2013;34(5–6):417–27. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/24190365/ [accessed 2023 Aug 17]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Friberger I, Nilsson JN, Lu L, Siikanen J, Ardenfors O, Milton S, Samén E, Goos JACM, Carlsten M, Holmin S, Tran TA. Comparative in vivo biodistribution of cells labelled with (89Zr).Zr-(oxinate)4 or (89Zr).Zr-DFO-NCS using PET. EJNMMI Res. 2023;13(1):1–12. https://ejnmmires.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13550-023-01021-1 [accessed 2023 Aug 16]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang S, Wang Y, Xu B, Qin T, Lv Y, Yan H, Shao Y, Fang Y, Zheng S, Qiu Y. Biodistribution of 89Zr-oxine-labeled human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by micro-PET/computed tomography imaging in Sprague-Dawley rats. Nucl Med Commun. 2022;43(7):834–46. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/35438673/ [accessed 2023 Jun 15]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee SH, Soh H, Chung JH, Cho EH, Lee SJ, Ju JM, Sheen JH, Kim H, Oh SJ, Lee SJ, Chung J, et al. Feasibility of real-time in vivo 89Zr-DFO-labeled CAR T-cell trafficking using PET imaging. Plos One. 2020;15(1). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6946129/ [accessed 2022 Nov 23) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Erkers T, Kaipe H, Nava S, Molldén P, Gustafsson B, Axelsson R, Ringdén O. Treatment of severe chronic graft-versus-host disease with decidual stromal cells and tracing with (111)indium radiolabeling. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(2):253–63. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/25162829/ [accessed 2022 Mar 31]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sugita J, Atsuta Y, Nakamae H, Maruyama Y, Ishiyama K, Shiratori S, Fukuda T, Kurata M, Shingai N, Ozawa Y, Masuko M, et al. Comparable survival outcomes with haploidentical stem cell transplantation and cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022;57(11):1681–88. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/35987912/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang J, Chang CY, Yang X, Zhou F, Liu J, Zhu S, Yu XZ, Liu C, O’Sullivan TE, Xie P, Feng Z, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor protects against graft-versus-host disease while preserving graft-versus-leukemia activity. Blood. 2022;140(19):2076–90. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/35981499/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Childs RW, Tian X, Vo P, Purev E, Kotecha RR, Carlsten M, Clara J, Flegel WA, Adams SD, Khuu HM, Stroncek DF, et al. Combined haploidentical and cord blood transplantation for refractory severe aplastic anaemia and hypoplastic myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(5):951–60. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.kib.ki.se/33993466/ [accessed 2023 Aug 21]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]