Abstract

Carbapenems are effective drugs against bacterial pathogens and resistance to them is considered a great public health threat, especially in notorious nosocomial pathogens like Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In this study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa infections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and African Journal Online) were systematically searched following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2020 statements for articles reporting carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA) prevalence between 2012 and 2022. Pooled prevalence was determined with the random effect model and funnel plots were used to determine heterogeneity in R. A total of 47 articles were scanned for eligibility, among which 25 (14 for carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii and 11 for carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa) were included in the study after fulfilling the eligibility criteria. The pooled prevalence of CRPA in the present study was estimated at 8% (95% CI; 0.02–0.17; I2 = 98%; P <0.01). There was high heterogeneity (Q = 591.71, I2 = 98.9%; P<0.0001). In addition, this study’s pooled prevalence of CRAB was estimated at 20% (95% CI; 0.04–0.43; I2 = 99%; P <0.01). There was high heterogeneity (Q = 1452.57, I2 = 99%; P<0.0001). Also, a funnel plot analysis of the studies showed high degree of heterogeneity. The carbapenemase genes commonly isolated from A. baumannii in this study include blaOXA23, blaOXA48, blaGES., blaNDM, blaVIM, blaOXA24, blaOXA58, blaOXA51, blaSIM-1, blaOXA40, blaOXA66, blaOXA69, blaOXA91, with blaOXA23 and blaVIM being the most common. On the other hand, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaOXA48, blaOXA51, blaSIM-1, blaOXA181, blaKPC, blaOXA23, blaOXA50 were the commonly isolated carbapenemase genes in P. aeruginosa, among which blaVIM and blaNDM genes were the most frequently isolated. Surveillance of drug-resistant pathogens in Sub-Saharan Africa is essential in reducing the region’s disease burden. This study has shown that the region has significantly high multidrug-resistant pathogen prevalence. This is a wake-up call for policymakers to put in place measures to reduce the spread of these critical priority pathogens.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a leading public health threat globally, considerably escalating morbidity, mortality and treatment failure of microbial infections, as well as economic losses to individuals and nations [1]. According to the 2016 Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, AMR would be responsible for 10 million deaths yearly by 2050 with a large amount of these deaths occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa [2]. However, a recent report of almost 5 million deaths linked with AMR in 2019 alone has shown that we will be reaching the 10 million AMR-associated deaths sooner than earlier predicted [3].

Carbapenems are beta-lactam antibiotics with broad-spectrum bactericidal activities against both Gram-positive and negative pathogens [4]. They are often used as last-line drugs against bacterial infections [5]. Unfortunately, bacterial pathogens have developed resistance to this last-resort group of antibiotics through various genetic modifications and production of carbapenem-hydrolysing enzymes [6]. Treatment of infections have become more difficult and expensive, especially against the notorious Gram-negative bacteria, due to resistance to last-line antibiotics.

Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are Gram-negative pathogens that belong to the ESKAPE group (an acronym for the group of bacteria, encompassing both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, made up of Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species [7]. These are bacterial pathogens that are notorious for their resistance to clinically relevant antimicrobials. Furthermore, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) and P. aeruginosa (CRPA) have both been grouped as critical priority pathogens for which there is a need to develop new and effective antimicrobials. These have made the surveillance of these two pathogens a necessity, especially in low-middle-income countries where surveillance is poor. A recent report shows that CRAB and CRPA have mortality rates of 30.5% and 24.5% within 90 days of a positive culture [8]. Moreover, CRAB and CRPA were reported to be responsible for 57,700 and 38,100 deaths globally in 2019 respectively [3].

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is known for having a high burden of infectious diseases which might be linked to the poverty level and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices in the region [9,10]. The [3] report also showed that Sub-Saharan Africa suffers the highest prevalence of AMR-associated death globally. The scarcity of AMR data from SSA has made it difficult to determine the true risk and burden of AMR infections in the region. Also, a recent study predicting the global prevalence of carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa could not include majority of Sub-Saharan African countries in the analysis due to scarcity of data. This further emphasizes the need to surveillance of AMR pathogens in Africa, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis that reports the pooled prevalence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii in Sub-Saharan Africa. This systematic review is an extensive analysis of the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii with the aim to describe the epidemiology within Sub-Saharan Africa. This study also investigated the prevalence of carbapenemase genes in the region. This would provide insight on the public health risks posed by these priority pathogens and the development of sustainable prevention and control interventions in this region.

Method

Search strategy

This study was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. Electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and African Journal Online) were searched for articles published on carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii and/or P. aeruginosa in sub-Saharan Africa. The last search was on the 31st of July 2022.

Eligibility criteria

This study only included studies published in Sub-Saharan Africa between January 2012 and July 2022. Only studies that reported A. baumannii and/or P. aeruginosa prevalence in humans were considered for the analysis. Studies that reported A. baumannii and/or P. aeruginosa prevalence from countries outside Sub-Saharan Africa were excluded from the analysis. Also, only studies that reported at least one case of carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii and/or P. aeruginosa were included. Only studies published in English or with English translations available were included in the final analysis. Lastly, cross-sectional studies, retrospective, and longitudinal analyses were considered in this analysis. Literature and systematic reviews were excluded from this analysis.

Screening strategy

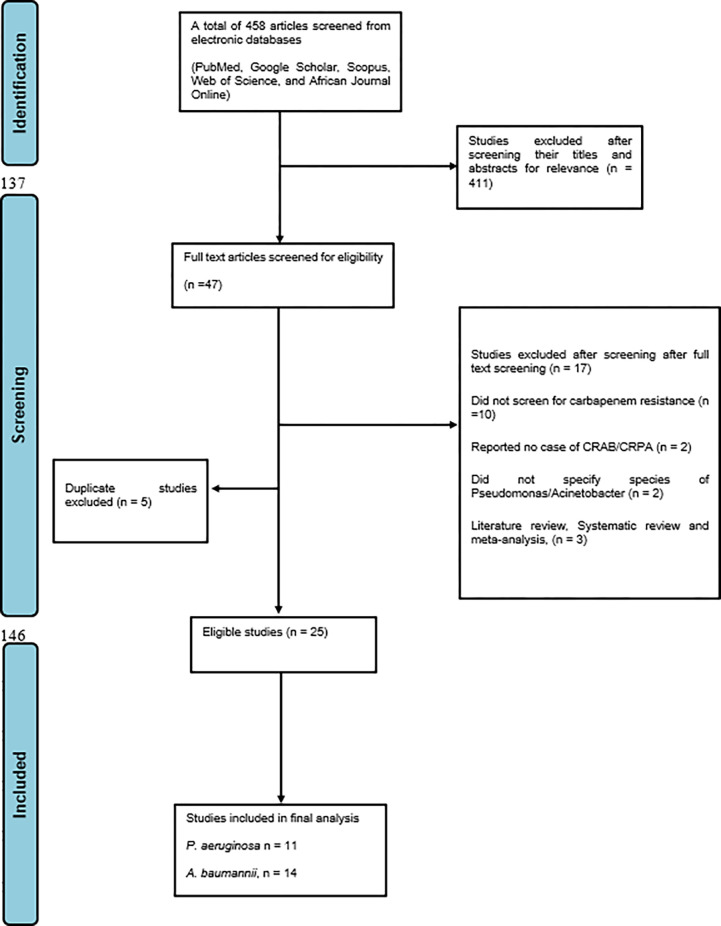

Articles were first screened based on their titles and abstracts by two independent researchers. Two other researchers then screened eligible articles by reading through their full text, ineligible articles were excluded and the reasons for their exclusion were stated (Fig 1). All disagreements were resolved through discussions. A third researcher confirmed the eligibility of the included studies before including them in the analysis. During extraction, for studies that reported different percentages for imipenem or meropenem, preference was given to meropenem since it has better activity against Gram-negative bacteria [12].

Fig 1. PRISMA flowchart for the search process.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

A data extraction table was created by one reviewer and two other reviewers extracted the following data from the eligible articles; first author, study design, study country, study aim, sample size, sample source, organism prevalence, carbapenem-resistance prevalence, Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) method, carbapenem used. All disagreements were resolved through discussions and a fourth reviewer confirmed the extracted data. This step was performed for each of the organisms.

Data analysis

The data extracted was cleaned for any eligibility criterion error, and the meta-analysis was performed using RStudio version 4.2.0. The Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) and P. aeruginosa (CRPA) pooled prevalence of the present study was analyzed using the random-effect model while subgroup prevalence was considered based on the source of the reported studies. Cochran Q statistics and the I2 (inverse variance index) were used to analyze the heterogeneity (low, 0–0.25; fair, 0.25–0.5; moderate, 0.5–0.75; and high, above 0.75). A p-value of <0.01 was considered significant. Publication bias and degree of heterogeneity was examined visually with the use of the funnel plot.

Result

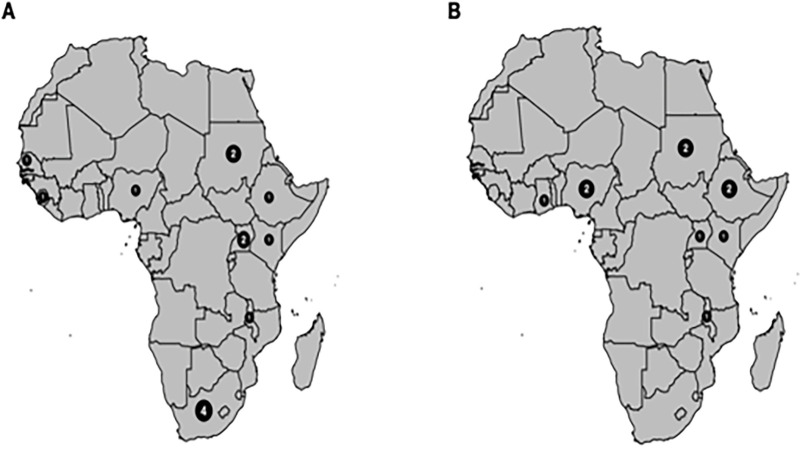

A total of 25 articles (CRAB, 14; CRPA 11) (Fig 2) were included in the final analysis after screening 458 articles from different electronic databases. These articles were from different countries and sub-regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Of the 14 articles analysed for the CRAB, South Africa had 4(28.6%), Sudan and Uganda had 2(14.3%) each, while Ethiopia, Senegal Malawi, Kenya, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone had one each. For the CRPA analysis, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Sudan each had 2 eligible articles included in the final analysis while Malawi, Ghana, and Kenya each had just one eligible article (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig 2. Distribution of eligible articles included in the final analysis.

A. A total of 14 articles were analysed to determine the pooled prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. A majority (4) were from South Africa, Sudan and Uganda had 2 each, while Ethiopia, Senegal, Malawi, Kenya, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone had one each. B. A total of 11 articles were analysed to determine the pooled prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 2 each from Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Sudan while Malawi, Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda had one each.

Table 1. Data extraction table for carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) studies.

| First author | Year | Study design | Study country | Study aim | Sample size | Sample source | A. baumannii prevalence | Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii prevalence (%) | AST method | Carbapenem use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | 2021 | cross-sectional study | Sudan | To assess the phenotypic and genotypic patterns of antimicrobial resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii at hospital settings, Khartoum, Sudan | 36 | Human | 36 | 17 (47%) | Disc diffusion | Imipenem |

| [14] | 2013 | cross-sectional | South Africa | To evaluate and optimise multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) assays for the rapid differentiation of the four subgroups of the OXA genes and the subgroups of the MBL genes of A. baumannii. | 97 | Human |

97 |

61 (62.8%) |

Vitek 2 | Meropenem and Imipenem |

| [15] | 2021 | Longitudinal | Ethiopia | To detect and phenotypically characterize carbapenem-resistant Gram negative bacilli from Ethiopian public health institute | 1337 | Human | 36 | 4 (0.3%) | Simplified carbapenem inactivation method | Meropenem |

| [16] | 2016 | cross sectional study | Uganda | To determine the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii at Mulago Hospital in Kampala Uganda, and to establish whether the hospital environment harbours carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative rods | 869 | Human | 29 | 9 (1.04%) | Disc diffusion | Imipenem |

| [17] | 2015 | cross-sectional study | South Africa | To determine the prevalence of β-lactamase genes in multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical A. baumannii isolates using Multiplex-PCR (M-PCR) assays. |

94 | Human | 94 | 80 (85.1%) | Vitek 2 | Meropenem and Imipenem |

| [18] | 2019 | cross sectional study | South Africa | To investigated the 28 genetic determinants of multi-drug resistant A. baumannii (MDRAB) at a teaching hospital in 29 Pretoria, South Africa. | 100 | Human | 100 | 95 (95%) | Vitek 2 | Imipenem and Meropenem |

| [19] | 2012 | longitudinal prospective study | Senegal | To identify the presence of A. baumannii carbapenem-resistant encoding genes in natural reservoirs in Senegal, where antibiotic pressure is believed to be low | 717 | Human | 78 | 6 (0.8%) | Disc diffusion | Imipenem |

| [20] | 2019 | cross-sectional | Sudan | To characterize the genotypes and phenotypes associated with carbapenem-resistance in Gram-negative bacilli from patients in Sudan | 367 | Human | not stated | 1 (0.3%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [21] | 2022 | cross-sectional study | Malawi | To ascertain the antimicrobial resistance in clinical bacterial pathogens from in-patient adults in a tertiary hospital in Malawi | 694 | Human | 26 | 4 (0.58%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [22] | 2021 | cross sectional study | Kenya | To understand the antibiotic resistance profiles, genes, sequence types, and distribution of carbapenem-resistant gram from patients in six hospitals across five Kenyan counties. | 48 | Human | 27 | 27 (56%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [23] | 2013 | cross sectional study | Nigeria | To report the presence of carbapenem-encoding genes in imipenem-resistant A. baumannii among multidrug-resistant clinical isolates collected from the University College Hospital, Ibadan, south-western Nigeria. | 5 | Human | 3 | 3 (60%) | Combined disc diffusion test (CDDT) | Imipenem |

| [24] | 2017 | cross-sectional | Uganda | To determine the intra-species genotypic diversity among P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from hospitalized patients and the environment at Mulago Hospital | 736 | Human | 7 | 1 (0.14%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [25] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Sierra Leone | To assess antibiotic resistance rates from isolates in the urine and sputum samples of patients with clinical features of healthcare-associated infections HAIs. | 164 | Human | 16 | 2(1.2%) | Vitek 2 | Meropenem and Imipenem |

| [26] | 2018 | retrospective descriptive study | South Africa | To determine prevalence of culture confirmed sepsis due to A. baumannii, antimicrobial susceptibility and case fatality rates (CFR) due to this organism | 93527 | Human | 399 | 11 (0.01%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem and Imipenem |

CRAB = Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

AST = Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

*The percentage in the bracket is a fraction of the sample size.

Table 2. Data extraction table for carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA) studies.

| First author | Year | Study design | Study country | Study aim | Sample size | Sample source | P. aeruginosa prevalence | Carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa prevalence (%) | AST method | Carbapenem used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | 2022 | cross sectional | Malawi | To ascertain antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in clinical bacterial pathogens from in-hospital adult patients at a tertiary hospital in Malawi | 694 | Human | 29 | 18 (2.5%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [15] | 2021 | cross sectional | Ethiopia | To detect and phenotypically characterise carbapenemase no-susceptible Gram-negative bacilli at the Ethopian Public health institute | 1337 | Human | 36 | 4(0.2%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [16] | 2016 | cross sectional | Uganda | To determine the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii at Mulago Hospital in Kampala Uganda, and to establish whether the hospital environment harbours carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative rods | 869 | Human | 42 | 9 (1.15%) | Disc diffusion | Imipenem |

| [27] | 2019 | cross sectional | Nigeria | To investigate the occurrence of MBL-producing bacteria in a healthcare facility in Nigeria. | 110 | Human | Not reported | 13(11.8%) | Combined disc method | |

| [20] | 2019 | cross sectional | Sudan | To characterise the phenotypes and genotypes associated with carbapenems-resistant in gram-negative bacilli isolated | 367 | Human | Not reported | 14(3.8%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

| [28] | 2019 | cross sectional | Ghana | To apply phenotypic and genotypic methods to identify and characterise carbapenem-resistant (CR) Gram-negative bacteria from the hospital environment in Ghana. | 111 | Human | Not reported | 51(45.9%) | Disc synergy | Edoripenem (75%), imipenem (66.7%) and meropenem (58%) |

| [22] | 2021 | Cross-sectional | Kenya | To understand the antibiotic resistance profiles, genes, sequence types, and distribution of carbapenem-resistant Gram negative bacteria from patients in six hospitals across five Kenyan counties by bacterial culture, antibiotic susceptibility testing and whole genome sequence analysis. Culture, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and whole-genome sequence analysis. | 48 | Human | 14 | 14(29.2%) | Meropenem | |

| [29] | 2021 | cross sectional | Nigeria | To determine the incidence and Molecular Characterization of Carbapenemase Genes in Association with Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Tertiary Healthcare Facilities in Southwest Nigeria | 430 | Human | 430 | 71(16.5%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem and doripenem |

| [24] | 2017 | cross sectional | Uganda | To report the intra-species genotypic diversity among P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii isolated from hospitalized patients and the environment at Mulago Hospital, using repetitive elements-based PCR (Rep-PCR) genotyping. | 736 | Human | 9 | 3(0.4%) | Meropenem | |

| [29] | 2018 | Cross sectional | Sudan | To detect (blaVIM, blaIMP and blaNDM) Metallo-β-lactamase genes in Khartoum state | 200 | Human | 54 | 33(16.5%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem and/ or imipenem. |

| [30] | 2019 | Cross sectional | Ethopia | To identify and determine multi-drug resistant, extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase producing bacterial isolates among blood culture specimens from pediatric patients less than five years of age from Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital using an automated BacT/Alert instrument. | 340 | Human | Not reported | 4(1.1%) | Disc diffusion | Meropenem |

CRPA = Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

AST = Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

*The percentage in the bracket is a fraction of the sample size.

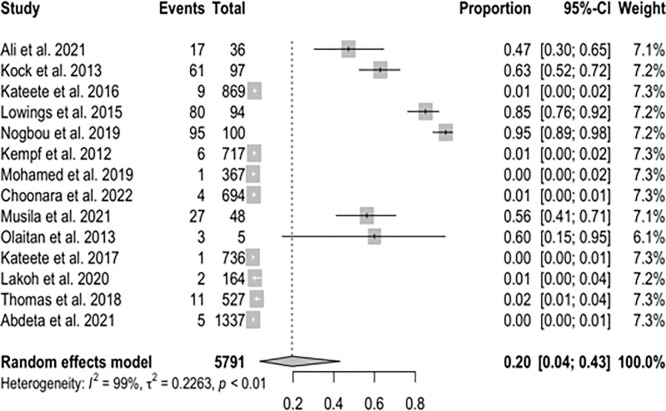

Meta-analysis of Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii

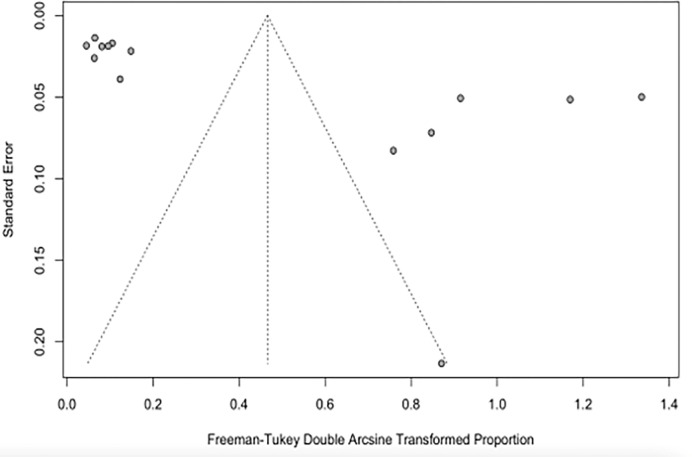

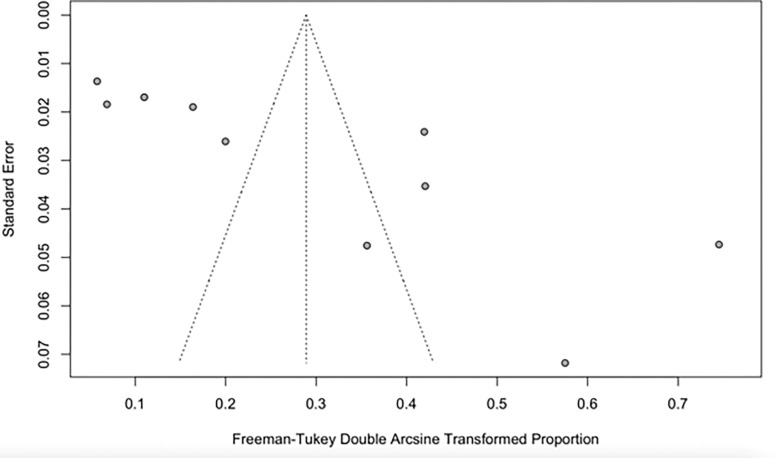

The pooled prevalence of CRAB in the present study was estimated at 20% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]; 0.04–0.43; I2 = 99%; P <0.01) (Fig 3). The funnel plot (Fig 4) and Q statistics show high heterogeneity (Q = 1452.57, I2 = 99%; P<0.0001) (S1 Fig) between the CRAB studies.

Fig 3. The Forest plots of random-effects meta-analysis show the pooled prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

CI = Confidence interval.

Fig 4. The Funnel plot of CRAB studies shows the publication bias of the study sample.

Meta-analysis of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa

The pooled prevalence of CRPA in the present study was estimated at 8% (95% CI; 0.02–0.17; I2 = 98%; P <0.01) (Fig 5). Similarly, there was high heterogeneity between CRPA studies analysed as shown by the Q statistics (Q = 591.71, I2 = 98.9%; P<0.0001) and the funnel plot (Figs 6 and S2).

Fig 5. Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Fig 6. The Funnel plot of CRPA studies shows the publication bias of the study sample.

Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant genes in A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa in Sub-Saharan Africa

The carbapenemase genes isolated from A. baumannii reported in the articles analysed include blaOXA23, blaOXA48, blaGES, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaOXA24, blaOXA58, blaOXA51, blaSIM-1, blaOXA40, blaOXA66, blaOXA69, blaOXA91. The most common carbapenemase gene in the studies analysed are the blaOXA23 and blaVIM. On the other hand, the carbapenemase genes reported in P. aeruginosa from studies in Sub-Saharan Africa included in this analysis are blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaOXA48, blaOXA51, blaSIM-1, blaOXA181, blaKPC, blaOXA23, blaOXA50. The most frequent among them are the blaVIM and blaNDM genes.

Discussion

Carbapenems are important broad-spectrum antimicrobials of last-resort; hence, resistance to them signifies increased infection mortality, hospital stay duration, and cost of treatment [31]. This challenge is mostly common to infections associated with notorious clinical pathogens such as A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa [32]. These two Gram-negative pathogens have been linked to varieties of hospital-acquired infections and multidrug resistance.

Carbapenemase-resistant A. baumannii in Sub-Saharan Africa in this study was estimated at 20% (95% CI; 0.04–0.43; I2 = 99%; P <0.01). [33] in their study on the occurrence and frequency of hospital-acquired (carbapenem-resistant) A. baumannii in Europe (EUR), Eastern Mediterranean (EMR) and Africa (AFR) stated similar results with a pooled incidence of Hospital Acquired-CRAB of 21.4 (95% CI 11.0–41.3) cases per 1,000 patients in the EUR, EMR and AFR WHO regions. On the other hand, our study revealed the pooled prevalence of CRPA in Sub-Saharan Africa to be 8% (95% CI; 0.02–0.17; I2 = 98%; P <0.01). This value is relatively low compared to the prevalence of carbapenem resistance reported in Indonesia, India, Italy, China, Germany, and Spain [34]. An additional study from Asia recounted a prevalence of 18.9% CRPA in the Asia-Pacific region. The unexpectedly lower prevalence reported in this study might be due to the absence data from many of the Sub-Saharan African countries. The high heterogeneity observed in this study is most likely not due to publication bias but a result of the different prevalence rates reported in the different studies analysed from different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa and the low number of eligible articles analysed in this study (Figs 5 and 6).

The most common carbapenem-resistant genes in P. aeruginosa in the compared studies in this analysis are the NDM and VIM genes. In the reports of [34] the blaVIM and blaIMP were the most prevalent carbapenemase genes in P. aeruginosa in Italy and Indonesia. The dominance of OXA-23 genes in CRAB isolates in many of the studies is not surprising as this gene has been associated with carbapenem resistance in this organism since the 1980s [35]. Furthermore, an earlier study indicated that the existence of plasmid encoding OXA-23 alone in A. baumannii is sufficient to confer resistance to carbapenem in A. baumannii [36]. Even though some of the studies analysed reported carbapenemase genes, many of them did not report the molecular basis of carbapenem resistance in their study. This might be a result of low resources for molecular techniques in many Sub-Saharan African labs.

The pooled prevalence during 2012–2022 should maximally reflect the current status of antibiotic resistance (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, we believe that the current prevalence of antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii infection is similar in the Sub-Saharan countries where these studies were carried out, most of which are facing the same degree of severity of antibiotic resistance. Most published studies have concentrated on the hospital epidemiology of these organisms and animal healthcare settings making it difficult to demonstrate the extra-hospital origin of A. baumannii. Thus, although antibiotic resistance has long been considered as a modern phenomenon, it predates the concept of selective antibiotic pressure due to clinical antibiotic usage [37].

Over the last few decades, the intensive use of antibiotics in humans and as growth-promoting and as prophylactic agents in livestock have resulted in serious environmental and public health problems since this enhances antimicrobial selective pressure [38]. According to a study by [39], it was discovered that A. baumannii isolated from various environmental locations has been linked to nosocomial spread. The resistant bacteria from the extra-hospital environments may be transmitted to humans, to whom they cause diseases that are difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics.

A major strength of our study is that we included studies comprising both in-patients and out-patients and from a range of different samples, which ensured the representativeness of our estimates for these institutions. However, our study has some limitations. Firstly, the country representativeness of the individual studies is unclear in most cases, limiting our findings’ external validity. Secondly, studies are not evenly distributed across the Sub-Saharan regions. Some countries have more studies included in the analysis while there were no studies from others. Consequently, possible differences in CRAB and CRPA incidence and prevalence between the countries may be masked by geographical proximity. Thirdly, due to the relatively low number of hospital-wide studies, our hospital-wide estimates of hospital-acquired A. baumannii infections are unlikely to be generalizable.

Conclusion

Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are two important public health pathogens due to their increasingly multidrug-resistant nature. The prevalence of CRAB and CRPA reported in Sub-Saharan Africa indicates a serious threat to the Sub-Saharan African populace. Sensitization on the dangers of self-medication and poor antibiotics stewardship should be intensified as well as advocacy for the reduction in the use of antibiotics for growth promotion and prophylactics in animals. There is a need for urgent and comprehensive surveillance studies including both hospital environments and communities to determine the true prevalence of these drug-resistant pathogens in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, finally, infection control policies promoting personal and environmental hygiene, and appropriate administration of antibiotics by clinicians and veterinarians should be made and enforced to facilitate the reduction of CRAB in the region.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathogens and Global Health. 2015;109:309–318. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’ Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016;84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Ikuta KS, Sharara F. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong T, Fenn SJ, Hardie KR. JMM Profile: Carbapenems: a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2021. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma CW, Ng KKH., Yam BHC. Rapid Broad Spectrum Detection of Carbapenemases with a Dual Fluorogenic-Colorimetric Probe. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2021;143:6886–6894. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c00462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meletis G. Carbapenem resistance: overview of the problem and future perspectives. Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease. 2016;3:15–21. doi: 10.1177/2049936115621709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santajit S, Indrawattana N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Biomed Res Int. 2016:2475067. doi: 10.1155/2016/2475067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vivo A, Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, Jones MM, Perencevich EN, Rubin MA et al. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a retrospective cohort. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2022;22:291. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07436-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteside A, Zebryk N. New and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2017;299–313. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerbo A, Delgado RC, González PA. Water sanitation and hygiene in Sub-Saharan Africa: Coverage, risks of diarrheal diseases, and urbanization. Journal of Biosafety and Biosecurity. 2021;3:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jobb.2021.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Review. 2021;10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhanel GG, Simor AE, Vercaigne L. Imipenem and Meropenem: Comparison of In Vitro Activity, Pharmacokinetics, Clinical Trials and Adverse Effects. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;9:215–228. doi: 10.1155/1998/831425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali KM, Ali AH, Ali MA, Hamza SH, Hassan SM, Osman WA, et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Patterns of Antimicrobial Resistant Strains of Acinetobacter baumannii at Hospital Settings, Khartoum State, Sudan. EC Microbiology. 2021;17(3):44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kock MM, Bellomo AN, Storm N, Ehlers MM. Prevalence of carbapenem resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from clinical specimens obtained from an academic hospital in South Africa. South African Journal of Epidemiology Infection. 2013;28(1):28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdeta A, Bitew A, Fentaw S, Tsige E, Assefa D, Lejisa T, et al. Phenotypic characterization of carbapenem non-susceptible Gram-negative bacilli isolated from clinical specimens. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0256556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kateete DP, Nakanjako R, Namugenyi J, Erume J, Joloba ML, Najjuka CF. Carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii at Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda (2007–2009). Springer Plus. 2016;5:1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowings M, Ehlers MM, Dreyer AW, Kock MM. High prevalence of oxacillinases in clinical multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from the Tshwane region, South Africa–an update. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nogbou ND, Phofa DT, Nchabeleng M, Musyoki AM. Genetic determinants of multi-drug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii at an academic hospital in Pretoria, South Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;101(1):35–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempf M, Rolain JM, Diatta G, Azza S, Samb B, Mediannikov O, et al. Carbapenem Resistance and Acinetobacter baumannii in Senegal: The Paradigm of a Common Phenomenon in Natural Reservoirs. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Mohamed MEA, Ahmed AO, Kidir ESB, Sirag B, Ali MA. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carbapenems-resistant clinical Gram-negative bacteria from Sudan. Edorium Journal of Microbiology. 2019;5:100011M08MM2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choonara FE, Haldorsen BC, Ndhlovu I, Saulosi O, Maida T, Lampiao F et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of clinically important bacterial pathogens at the Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal 2022;34 (1):9–16. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v34i1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musila L, Kyany’a C, Maybank R, Stam J, Oundo V, Sang W. Detection of diverse carbapenem and multidrug resistance genes and high-risk strain types among carbapenem non-susceptible clinical isolates of target gram-negative bacteria in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olaitan AO, Berrazeg M, Fagade OE, Adelowo OO, Alli JA, Rolain JM. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii producing OXA-23 carbapenemase, Nigeria. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17:e469–e470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kateeta DP, Nakanjako R, Okee M, Joloba ML, Najjuka CF. Genotypic diversity among multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species at Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Research Notes. 2017;10:284–294. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2612-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakoh S, Li L, Sevalie S, Guo X, Adekanmbi O, Yang G et al. Antibiotic resistance in patients with clinical features of healthcare-associated infections in an urban tertiary hospital in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2020;9:38–48. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-0701-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas R, Wadula J, Seetharam S, Velaphi S. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and case fatality rates of Acinetobacter Baumannii sepsis in a neonatal unit. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2018;12(4):211–219. doi: 10.3855/jidc.9543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olowo-okere A, Abdullahi MA, Ladidi BK, Suleiman S, Tanko N, Ungokore HY et al. Emergence of Metallo-β-Lactamase Producing Gram-negative Bacteria in a Hospital with no History of Carbapenem Usage in Northwest Nigeria. Ife Journal of Science. 2019;21(2):323–332. doi: 10.4314/ijs.v21i2.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Codejoe FS, Donkor ES, Smith TJ, Miller K. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli Pathogens from Hospitals in Ghana. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2019;25(10):1449–1457. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olaniran OB, Adeleke OE, Donia A, Shahid R, Bokhari H. Incidence and Molecular Characterization of Carbapenemase Gene in Association with Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Tertiary Healthcare Facilities in Southwest Nigeria. Current Microbiology. 2022;79:27–41. doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02706-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adam MA, Elhag WI. Prevalence of metallo-β-lactamase acquired genes among carbapenems susceptible and resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates using multiplex PCR, Khartoum hospitals, Khartoum Sudan. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2018;18:668–674. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tadesse MM, Matebie ZA, Tullu KD. Multi-drug resistant, extended spectrum beta-lactamase and carbapenemase-producing bacterial isolates among children under five years old suspected of bloodstream infection in a specialized Hospital in Ethiopia: Cross- Sectional Study. Research Square. 2019: 1–14. doi: 10.212031rs.2.149521/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2016;22:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olaniyi A, Niklas W, Thomas H, Iruka NO, Tim E, Robby M. The incidence and prevalence of hospital-acquired (carbapenem resistant) Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe, Eastern Mediterranean and Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerging Microbes and Infections. 2019;8(1):1747–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang MG, Liu ZY, Liao XP. Retrospective Data Insight into the Global Distribution of Carbapenemase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics. 2021;10:548. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans BA, Amyes SGB. OXA β- Lactamases. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2014;27:241–263. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00117-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heritier C, Poirel L, Lambert T, Nordmann P. Contribution of acquired carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxicillinases to carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial Agents of Chemotheraphy. 2005;49:3198–3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, Morar M, Sung WW. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature. 2011;477:457–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anane AY, Apalata T, Vasaikar S, Okuthe GE, Songca S. Prevalence and molecular analysis of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in the extra-hospital environment in Mthatha, South Africa. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;23(6):371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gros M, Petrovic M, Barcelo D. Multi-residue analytical methods using LC-tandem MS for the determination of pharmaceuticals in environmental and wastewater samples: a review. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2006;386:941–952. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0586-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]