Abstract

Background

In 2016, two Canadian hospitals participated in a quality improvement (QI) program, the International Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Collaborative, and sought to adapt and implement a transition coach intervention (TCI). Both hospitals were challenged to provide optimal continuity of care for an increasing number of older adults. The two hospitals received initial funding, coaching, educational materials, and tools to adapt the TCI to their local contexts, but the QI project teams achieved different results. We aimed to compare the implementation of the ACE TCI in these two Canadian hospitals to identify the factors influencing the adaptation of the intervention to the local contexts and to understand their different results.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective multiple case study, including documentary analysis, 21 semi-structured individual interviews, and two focus groups. We performed thematic analysis using a hybrid inductive-deductive approach.

Results

Both hospitals met initial organizational goals to varying degrees. Our qualitative analysis highlighted certain factors that were critical to the effective implementation and achievement of the QI project goals: the magnitude of changes and adaptations to the initial intervention; the organizational approaches to the QI project implementation, management, and monitoring; the organizational context; the change management strategies; the ongoing health system reform and organizational restructuring. Our study also identified other key factors for successful care transition QI projects: minimal adaptation to the original evidence-based intervention; use of a collaborative, bottom-up approach; use of a theoretical model to support sustainability; support from clinical and organizational leadership; a strong organizational culture for QI; access to timely quality measures; financial support; use of a knowledge management platform; and involvement of an integrated research team and expert guidance.

Conclusion

Many of the lessons learned and strategies identified from our analysis will help clinicians, managers, and policymakers better address the issues and challenges of adapting evidence-based innovations in care transitions for older adults to local contexts.

Keywords: care transition, frailty, older adults, transition coach, implementation evaluation, multiple case study, quality improvement collaborative

INTRODUCTION

Frail older Canadians have complex health and social needs.(1,2) Frailty is a common geriatric syndrome characterized by age-associated declines in physiologic reserve and function across multiple organ systems, leading to increased vulnerability for adverse health outcomes when exposed to endogenous or exogenous stressors.(2,3) Frail older adults are at high risk of hospitalization(2,4) and are more likely to experience organizational failures in access, integration and, especially, coordination and continuity of care.(2,5) In particular, care transitions are high-risk moments in the care continuum that expose frail older adults to avoidable adverse events, threatening their autonomy and lives.(6–8)

The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) program(9) is a widely recognized evidence-informed quality improvement care model that addresses the many issues facing older adults across the continuum of care. In 2010, Sinai Health in Toronto, Canada, developed a context-adapted ACE strategy guideline.(10) Their ACE strategy is a multicomponent intervention within the continuum of care to reduce functional decline, hospital readmissions, emergency room visits, functional disability, and long-term care (LTC) admissions. The ACE strategy includes 1) emergency department (ED) care components; 2) inpatient care components; and 3) community-based interventions.(10) To improve post-discharge care, inpatient care components include care transition interventions involving a “transition coach”—an advanced practice nurse who educates and helps hospitalized patients develop self-management skills.(11) After implementing the ACE strategy, Sinai Health significantly improved overall care quality, reduced inappropriate resource use, and lowered costs.(10)

In 2015, the Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement (CFHI) (now Healthcare Excellence Canada) partnered with the Canadian Frailty Network (CFN) and Sinai Health to launch the International Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Collaborative, a twelve-month quality improvement (QI) program to help implement effective practices leading to better patient outcomes. The CFHI-CFN-Sinai Health partnership provided 18 improvement teams (17 in Canada and 1 in Iceland) with funding (CAD $40,000), coaching, educational materials, and tools to adapt Sinai Health’s ACE strategy to their local contexts. Two francophone hospitals participated: Hôpital Montfort (HM) in Ottawa, Ontario, and Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis (HDL), in Lévis, Québec. Both hospitals aimed to improve their hospital-to-community care transitions for a growing frail elderly population. Both hospitals chose to implement a Transition Coach Intervention (TCI) based on Sinai Health’s ACE strategy. The HM team successfully implemented the TCI, introduced practice changes, and achieved positive organizational outcomes, while the HDL team experienced many challenges and failed to move beyond the pre-implementation phase.

One of the implementation barriers limiting the spread of evidence-based innovations is the difficulty of adapting knowledge tools (e.g., practice guidelines) to other cultural and organizational contexts.(6) How to effectively adapt the ACE strategy TCI component to different cultural and provincial contexts is still poorly understood. Although a previous study has been conducted to determine the effectiveness of the ACE strategy at Mount Sinai Hospital,(10) to our knowledge, no study has previously analyzed the process of adaptation and implementation of the TCI in other Canadian contexts. This study was also the first to be conducted in two francophone hospital settings which adds an additional challenge to translate knowledge implementation material from one language to another.

We aimed to compare the implementation of the ACE TCI in these two Canadian hospitals to identify the factors influencing the adaptation of the intervention to the local contexts and to understand their different results. This study provides a unique opportunity to learn more about the process of implementing and adapting the ACE TCI to different settings and cultural backgrounds.

METHODS

We conducted comparative analyses to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each implementation process. We used a retrospective evaluation approach with a multiple case study design, following Yin’s methodology,(12) to identify factors influencing the TCI implementation and adaptation, and to understand the different outcomes in both contexts. According to Yin, case study methodology allows us to use multiple data sources, both qualitative and quantitative, to explore complex relationships between contexts, processes, and outcomes of interventions.(12) Sites selected represented two Canadian provinces with different health systems but many similar characteristics. Both hospitals 1) selected the same ACE TCI; 2) shared a common cultural and linguistic background; 3) were university-teaching hospitals; 4) received the same support and funding. The ethics committees of both hospitals approved our study. We used the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) to report our findings.(13)

Theoretical Framework

We used the Strategic Framework for a Useful and Used Evaluation(14) to analyze the following key elements: 1) stakeholders; 2) issues identified for different stages and levels (local, regional, provincial); 3) strategies for implementation and knowledge-sharing; and 4) contexts and environments that influenced the project’s implementation. This framework also analyzes the theoretical approaches, methods, and strategies tailored to complex projects.(14)

Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted 1) a documentary analysis (e.g., progress and final reports, CFHI documents); 2) semi-structured interviews until thematic saturation; and 3) two focus groups to validate interview findings. Documentary analysis helped document the project (history, context, actors, decisions, and outcomes), identify organizational and environmental factors, and better plan and understand interviews and focus groups.(12)

Quantitative data were obtained through documentary analysis. Both hospitals identified measures that allowed them to monitor activities and identify areas for improvement. HM selected 6 indicators, while HDL selected 3. Only the 30-day hospital readmission rate was common to both organizations (Table 1). Management teams, supported by the organization’s data analysis specialists, led the ongoing collection and analysis of field measurements.

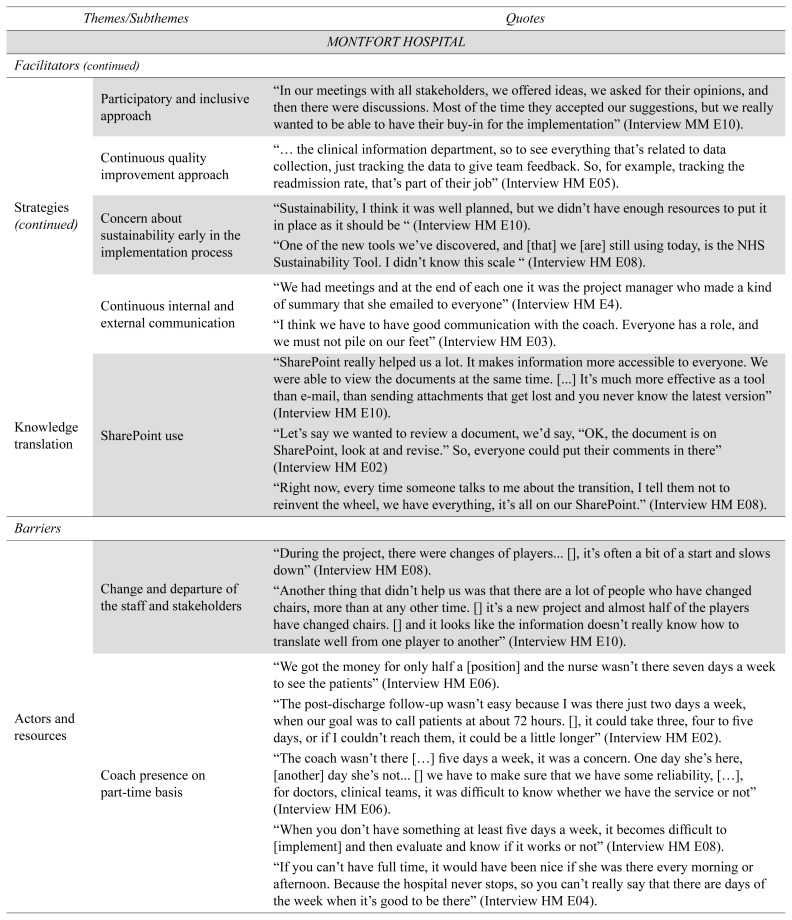

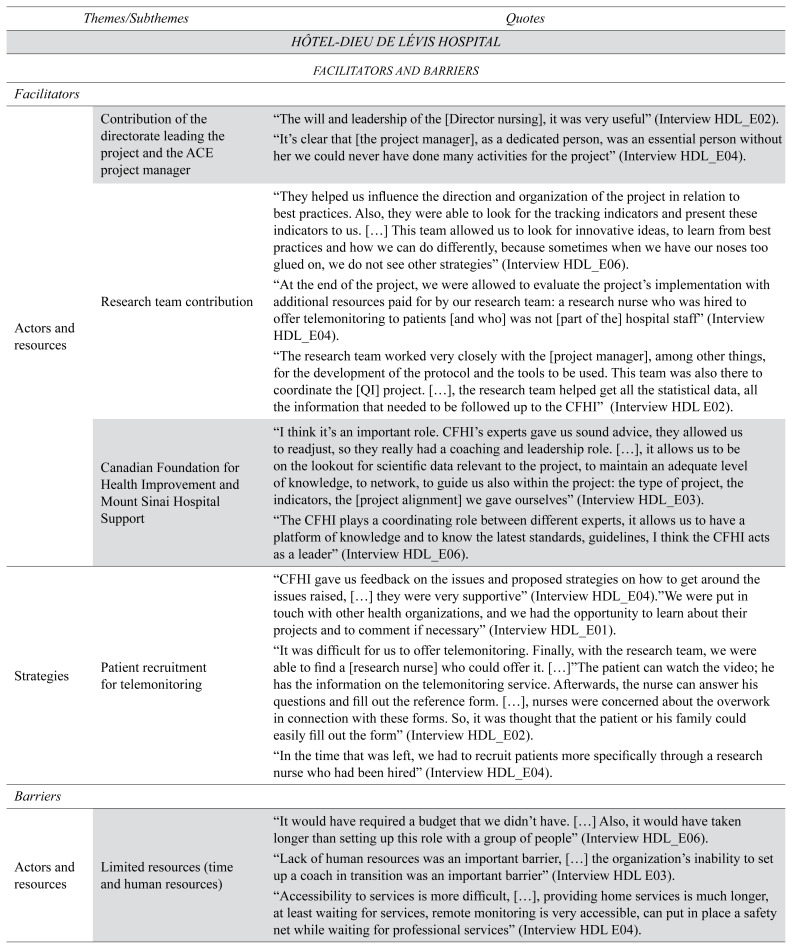

Table 1.

ACE project organizational target achievement

| Organization | Measurement | Baseline Measures a | Target | Value Measured b c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hôpital Montfort | Hospital readmission rate | 6% | 4.5% (reduction of 25%) | 3.42% (Mean) (43% Relative Risk Reduction) |

| Rate of compliance with the comparative review of drugs on discharge | 88.1% | 90% | N/Ad | |

| NRC Picker Surveye: Patients answering “YES” to the question as to whether “Families have sufficient information about recovery” | 52.5% | 60% | N/Ad | |

| Number of scheduled appointments with a family doctor or specialist | No baseline data (new measurement) | 100% | 88% | |

| Number of consultations with the Community Care Centre program (patients/month) | 3.6 | 7.2 | 4 (11% Relative Risk Increase) | |

| Patient satisfaction with their care transition (CTM-3f, Mean score) | No baseline data (new measurement) | > or = 3.5/5 | 3.8 | |

|

| ||||

| Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis (HDL) | Hospital readmission rate | 14% | 12% | 12% (14% Relative Risk Reduction) |

| Rate of emergency room visits within 30 days of hospital discharge | 22% | 20% | 20.5% (7% Relative Risk Reduction) | |

| Enrolling patients with a high risk of readmission to the telemonitoring service | No baseline data (new measurement) | 50% | 4% (1/24)g | |

Measured at baseline in 2015.

Value measured after the project started in 2016 or at the end of the ACE project in 2017.

Reported values represent absolute intervention effect and relative risk reductions (RRR) or increase (RRI) are presented in parentheses.

Missing data

NRC Picker Survey: National Research Corporation Picker Survey (https://nrchealth.com/)

CTM-3: Three-item Care Transition Measure (https://caretransitions.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/CTM-3.pdf)

Twenty-four patients agreed to participate in the ACE project and provide personal information (e.g., sociodemographic data), but only one person accepted the telemonitoring service.

We conducted qualitative interviews and focus groups with key stakeholders identified by each local ACE team leader, including clinicians, patient partners, and managers. We developed the interview guides based on our theoretical framework. Interviews and focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. We simultaneously collected and analyzed the data using an iterative approach. This helped in refining our interview guide.

Two independent researchers (EKG and SB) performed thematic analysis according to Braun et al.(15) using Nvivo 12.0 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia). We used a hybrid inductive-deductive approach to identify themes based on our theoretical framework. The researchers developed a coding structure with themes based on the framework and refined it as new themes emerged.(12) We used a descriptive and interpretive approach to assign codes before grouping similar codes into broader themes and theme categories. Disagreements were resolved by discussion (EKG, SB, PA, LB).

RESULTS

Both sites adapted the ACE TCI based on their local contexts and various organizational goals.

Documentary Analysis Results

The documentary analysis allowed us to describe the context, document the QI project governance decisions and adjustments, access the reported quantitative data, and examine how each organization implemented the project. Documentation supporting this and all analyses is available on request.

ACE Transition Coach Intervention Adaptation to Local Contexts

The Director of Medicine, Rehabilitation, Geriatrics, Therapeutic Services, Palliative Care and Discharge Planning supported the project at HM. HM slightly modified the original intervention to fit the local context. The HM team hired an advanced practice nurse to serve as a transition coach. Her role focused on pre-discharge patient education, chronic disease self-management, and coordinating post-discharge follow-up. The intervention targeted people aged ≥65 years, scoring 3–7 on the Clinical Frailty Scale(16) scheduled for discharge from an acute medical unit to the community, and able to attend health and medication management education sessions. Patients discharged to a nursing home, rehabilitation unit, intensive care unit, psychiatric unit, or palliative care unit were excluded. The ACE project was integrated into Montfort’s Senior Friendly Hospital strategy and managed by two teams: (1) an implementation team responsible for the project’s local planning and implementation; and (2) a project management team.

At HDL, the ACE project was initiated by an embedded clinician researcher and supported by the Director of Nursing, the Chief Executive Officer, and the Director of the Support for Elderly Autonomy Program. The HDL team did not hire a transition coach. Discharge planning and coordination were already initiated by nurse discharge coordinators. Instead, the team offered patients access to a telemonitoring service managed by a nonprofit, community-based organization (Télésurveillance-Santé-Chaudière-Appalaches), in partnership with Info-Santé-811, a free province-wide telephone helpline. Telemonitoring connects older patients or their family members with a nurse for non-emergency health or social issues 24 hours a day, seven days a week for a monthly fee (CAD $25/month in 2017). To meet eligibility criteria for the telemonitoring service, the HDL intervention targeted patients aged 50 years and older, at high risk for 30-day hospital readmission determined by a modified LACE Index Score (7/12 or higher),(17) able to give consent or have a caregiver who could provide proxy consent. Patients were excluded if they did not speak French or English, or were transferred to a long-term care home or to palliative care.

Since 2013, HDL had been implementing Quebec’s Specialized Approach to Senior Hospital Care (SASHC), aiming to improve the quality of hospital care of older adults.(18) Quebec’s SASHC is heavily influenced by the ACE strategy and included seven objectives overlapping with Ontario’s Senior Friendly Hospital Strategy.(19) HDL’s ACE project was seen as another lever for Quebec’s SASHC and was managed through two subcommittees: (1) an executive committee responsible for designing and implementing the local ACE initiative; and (2) an extended committee involving hospital executives, managers, and advisors.

ACE Projects Comparative Organizational Target Achievements at Both Sites

Each hospital set measurable targets to assess the effectiveness of its respective TCI. Table 1 compares how the two hospitals achieved these targets.

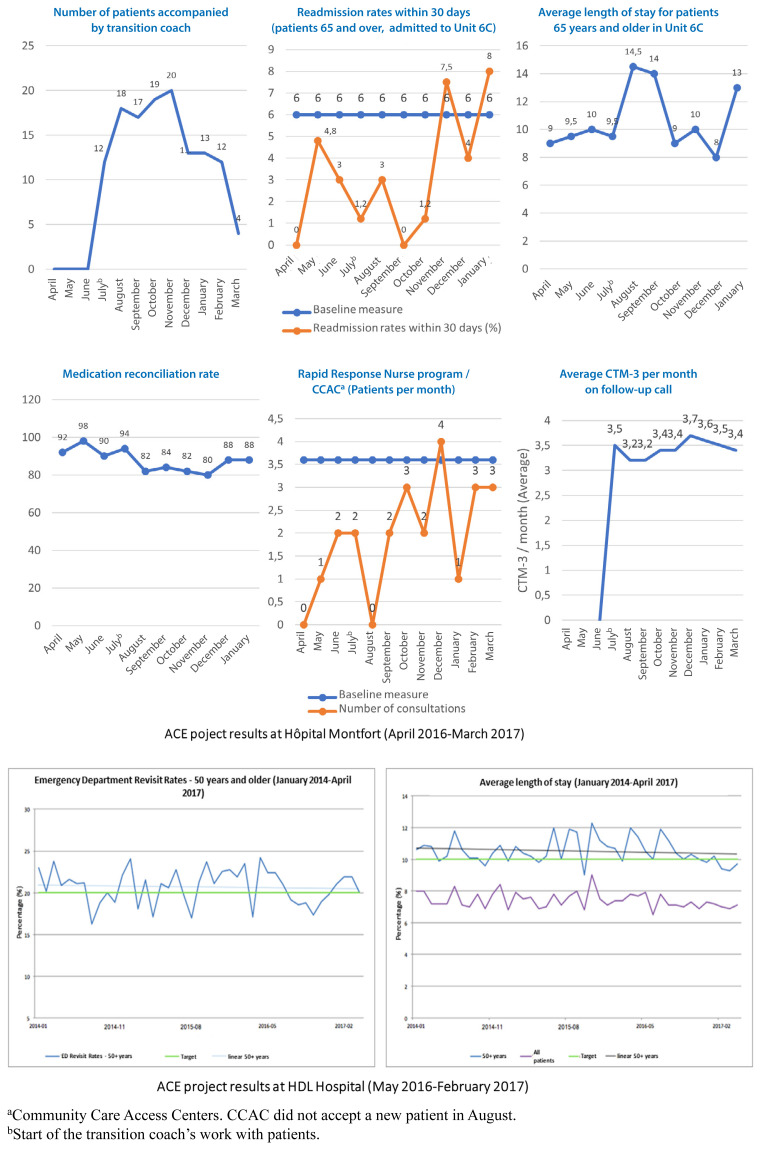

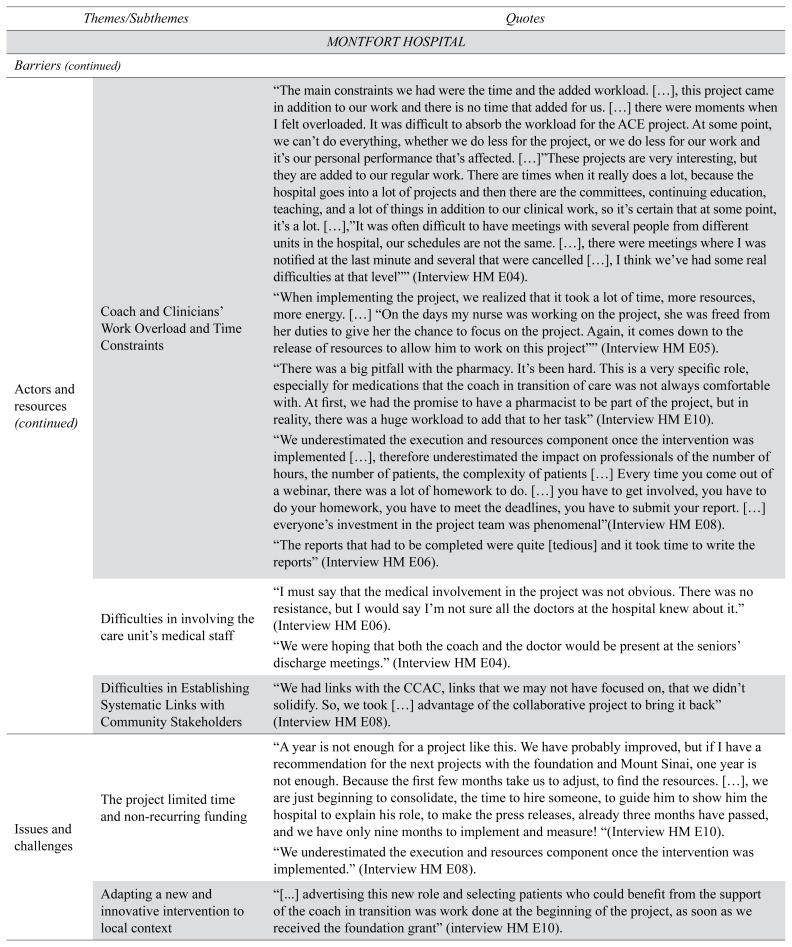

At HM, over a nine-month period (July 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017), the transition coach accompanied 128 patients (14.2 patients per month), whereas the initial goal was 20 patients per month. The transition coach dedicated the last month of the project (March 2017) to knowledge transfer activities to transfer her knowledge to the new discharge management team. HM met three of its six goals: reducing hospital readmission rates by 24%, reaching 88% of patients with a scheduled follow-up appointment with a family doctor or specialist, and exceeding its goal for patient satisfaction measured by the three-item Care Transition Measure (CTM-3) (mean score 3.8). The average length of stay for frail seniors in the care unit was stable. Medication reconciliation worsened; however, the small sample size analyzed does not allow for a robust analysis. The Transition Coach referred several patients to the Rapid Response Nurse Program—Community Care Access Centers (CCACs) (average of 2.6 patients/month). This service was almost unused before hiring the Transition Coach (average 0.9 patients/month, 2014–2015). The CTM-3 was used to monitor patient satisfaction after discharge. This self-report measure was administered by the coach during the follow-up call within 24–48 hours after discharge. The team achieved the CTM-3 target early and it remained stable until the end of the project. HDL achieved two of its three targets: reducing emergency department visits within 30 days of hospital discharge from 22% to 20.5% and hospital readmissions from 14% to 12%. Figure 1 summarizes the ACE project results.

FIGURE 1.

ACE Project Results at the Two Hospitals

aCommunity Care Access Centers. CCAC did not accept a new patient in August.

bStart of the transition coach’s work with patients.

Results of Qualitative Studies

The next sections summarize the characteristics of the participants interviewed, their initial expectations and perceptions, and the factors that contributed to the difference in achieving the two hospitals initial goals.

Participants Profile

A single interviewer conducted 13 semi-directed individual phone interviews with HM key informants (May–September 2018; length: 40 to 90 minutes); and eight semi-directed individual phone interviews with HDL key informants (November 2018–April 2019; length: 40 to 75 minutes). We also conducted a focus group in each hospital to validate our interview findings and to gather additional information. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of key informants at both hospitals.

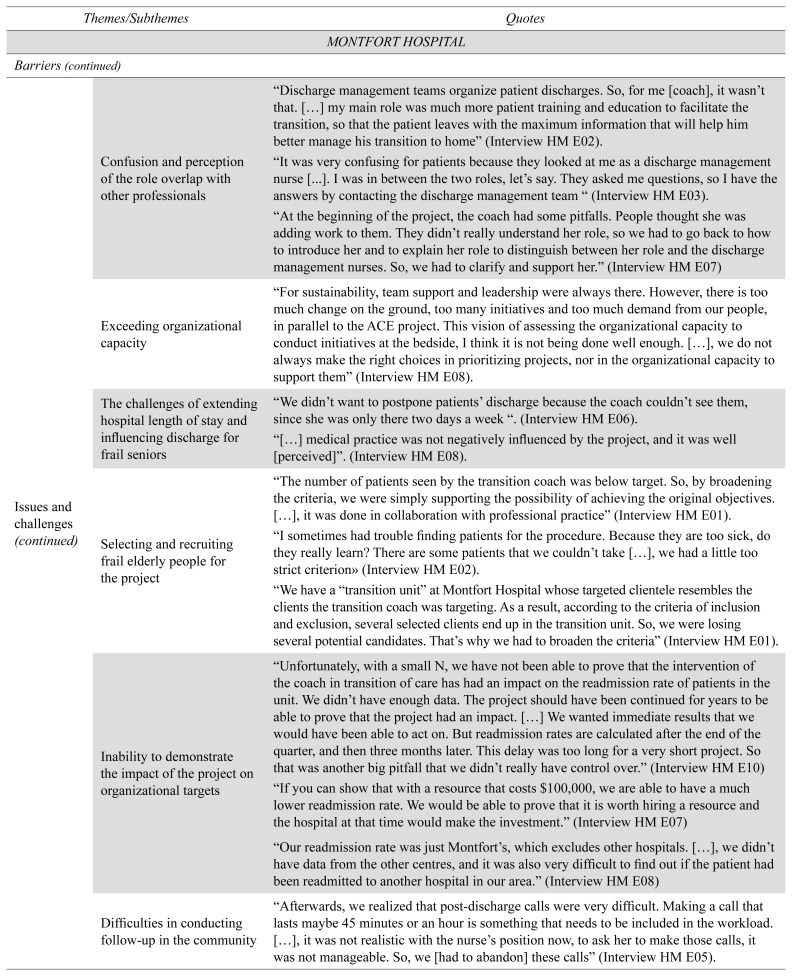

TABLE 2.

Individual interview and focus group participants’ characteristics

| Hôpital Montfort | Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Individual interviews (N=13) | Focus group (N=10) | Individual interviews (N=8) | Focus group (N=9) | |

|

| ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (11) |

| Female | 12 (92) | 9 (90) | 7 (87) | 8 (89) |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| 30–39 | 3 (23) | 2 (20) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (11) |

| 40–49 | 4 (30) | 4 (40) | 4 (50) | 4 (44) |

| 50–59 | 6 (46) | 4 (40) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (44) |

|

| ||||

| Occupation | ||||

| Health professionals | 6 (62) | 5 (50) | 2 (25) | 1 (11) |

| Physician | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | - | 1 (11) |

| Pharmacist | 1 (8) | - | - | |

| Advanced practice nurse | 2 (15) | 2 (20) | - | - |

| Registered nurse | 2 (15) | 2 (20) | 2 (25) | - |

| Researchers | - | - | 1 (12.5) | 1 (11) |

| Decision makers | 2 (15) | 2 (20) | 2 (25) | 3 (33) |

| Managers | 2 (15) | 2 (20) | 2 (25) | 3 (33) |

| Patient partners | 1 (8) | - | - | - |

| Others | 2 (15) | 1 (1) | - | - |

| Information technology specialist | 1(8) | 1 (10) | - | - |

| Administrative assistant | 1(8) | - | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Job Experience (years) | ||||

| Mean [min–max] | 18 [2.5–30] | 18.3 [2.5–30] | 21 [15–33] | 20.7 [15–33] |

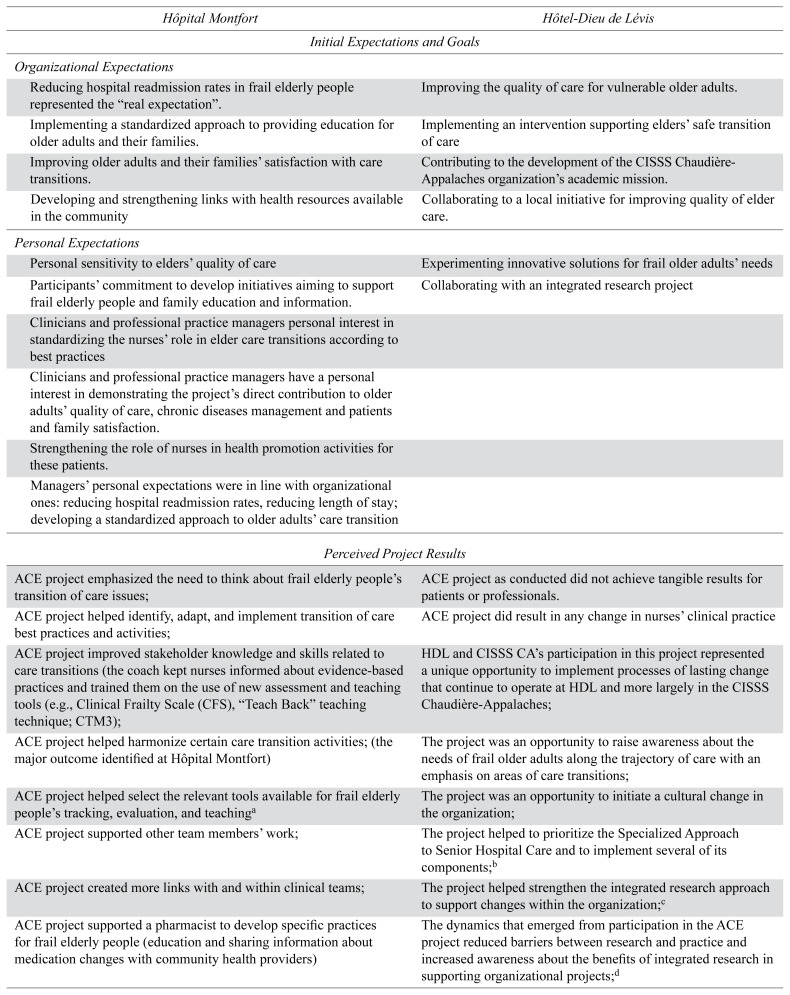

Initial Expectations and Perceived Results in Both Hospitals

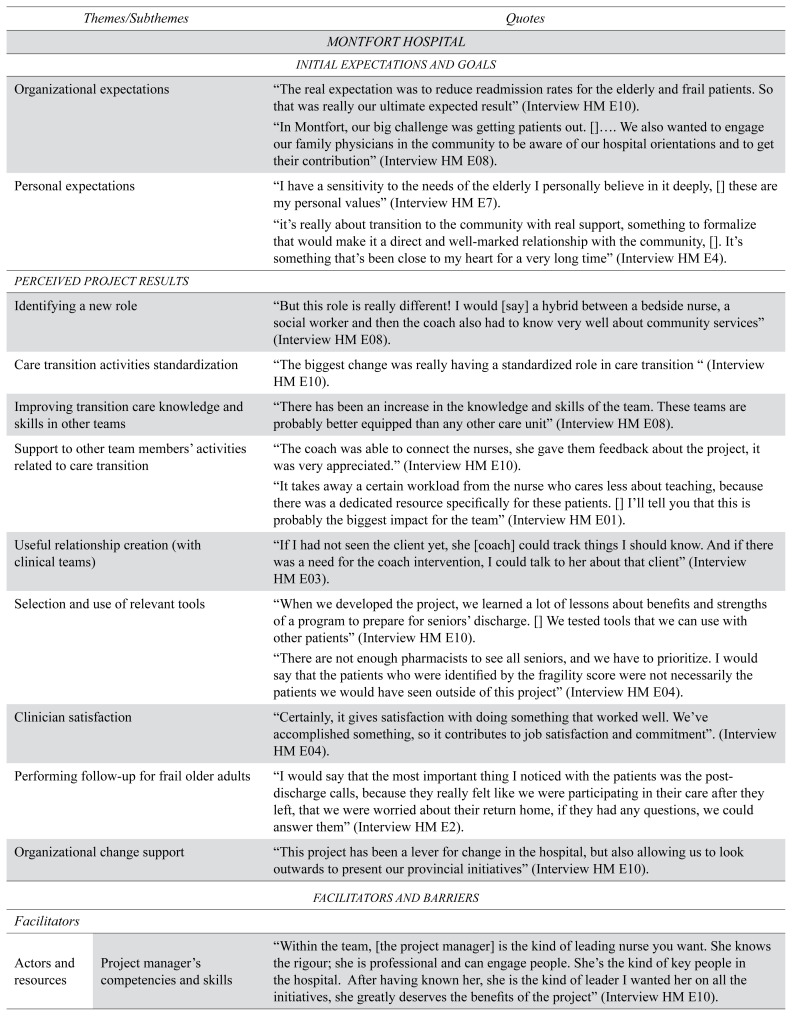

Main initial organizational expectations at both hospitals were implementing a standardized approach supporting safe transitions of care, improving the quality of care, and reducing hospital readmissions; improving elderly people and families’ satisfaction; and developing and strengthening links with community health resources. Actors were committed to developing QI initiatives to support older adults and families. At HM, clinicians expressed interest in strengthening the nurses’ role in elder care transitions. At HDL, participants wanted to collaborate on an integrated research project that was led by the senior author (PA) and the CISSS-CA Director of Nursing (JR) who proposed evidence-based strategies to assist decision makers in adapting and implementing the TCI.(6) Integrated research (a.k.a. embedded research) assumes that knowledge that is collected and generated in the field, through daily interaction and negotiation with clinicians, decision-makers and patients, provides better insight into the issues affecting these stakeholders, is more relevant to the local context, and is thus more easily translated into practice.(20,21) This is also the concept underlying the creation of Learning Health Systems, which was the basis for this project.(6) Appendix A summarizes both hospitals’ organizational and personal expectations and perceived ACE strategy results.

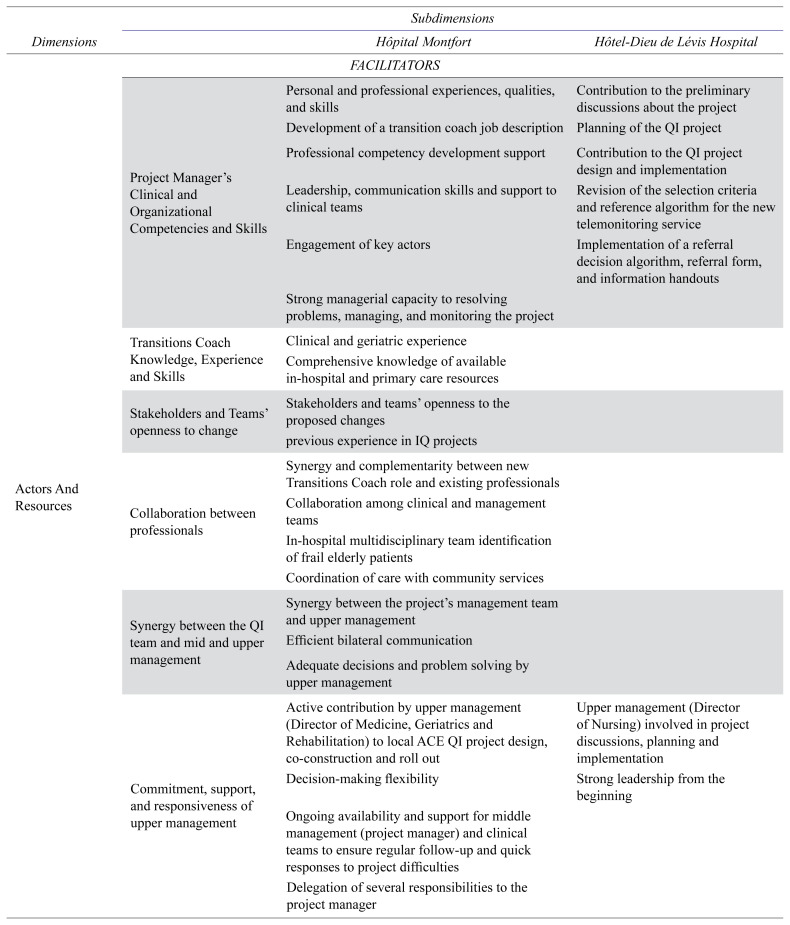

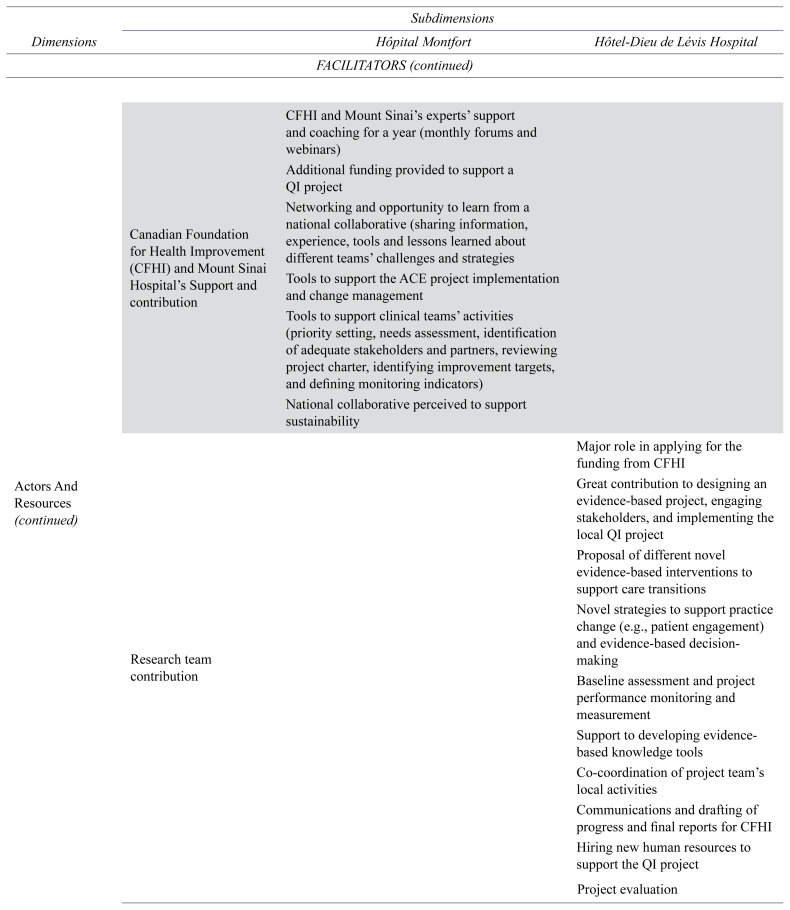

Facilitators and Barriers

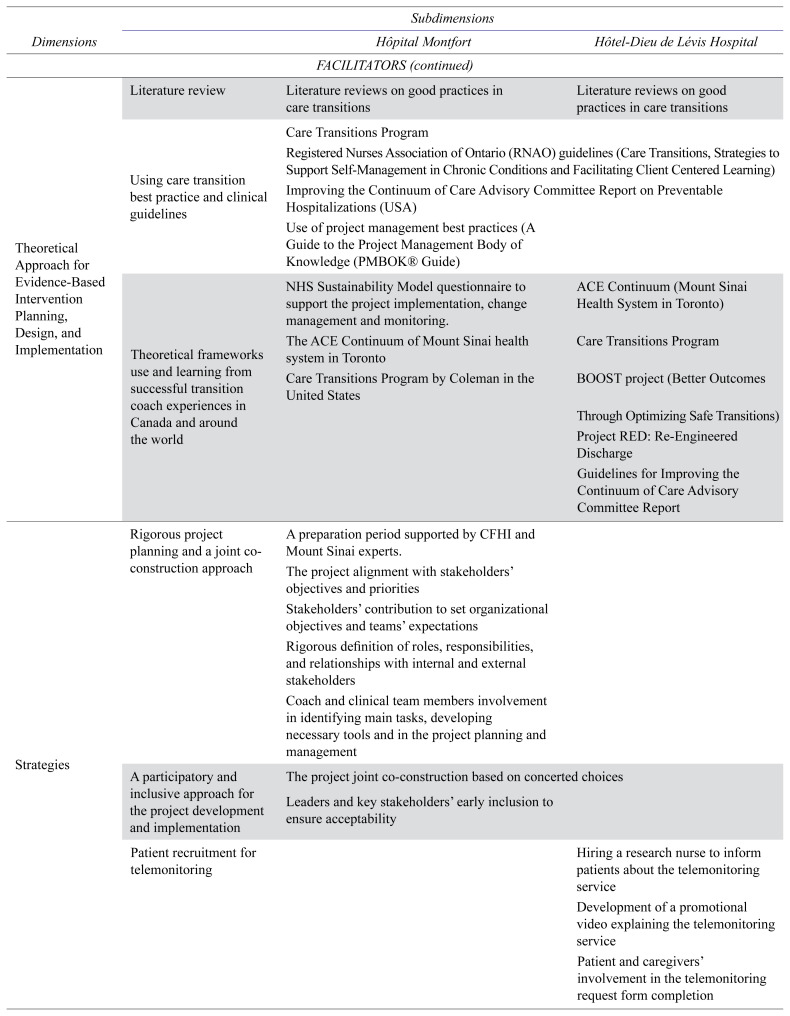

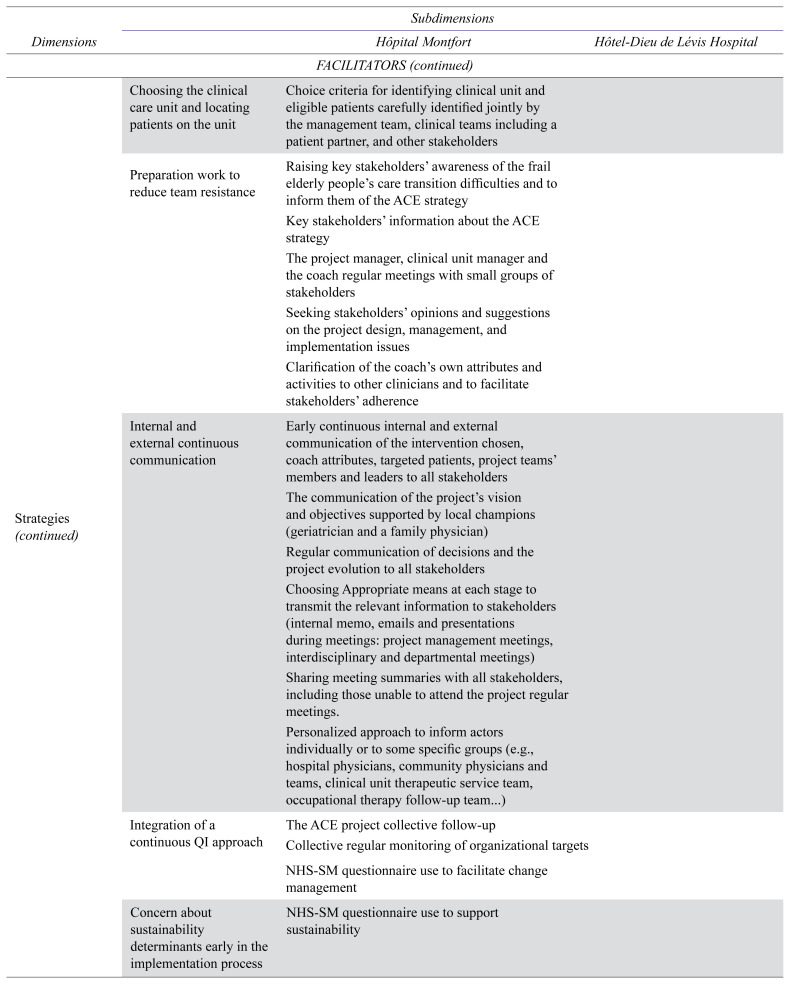

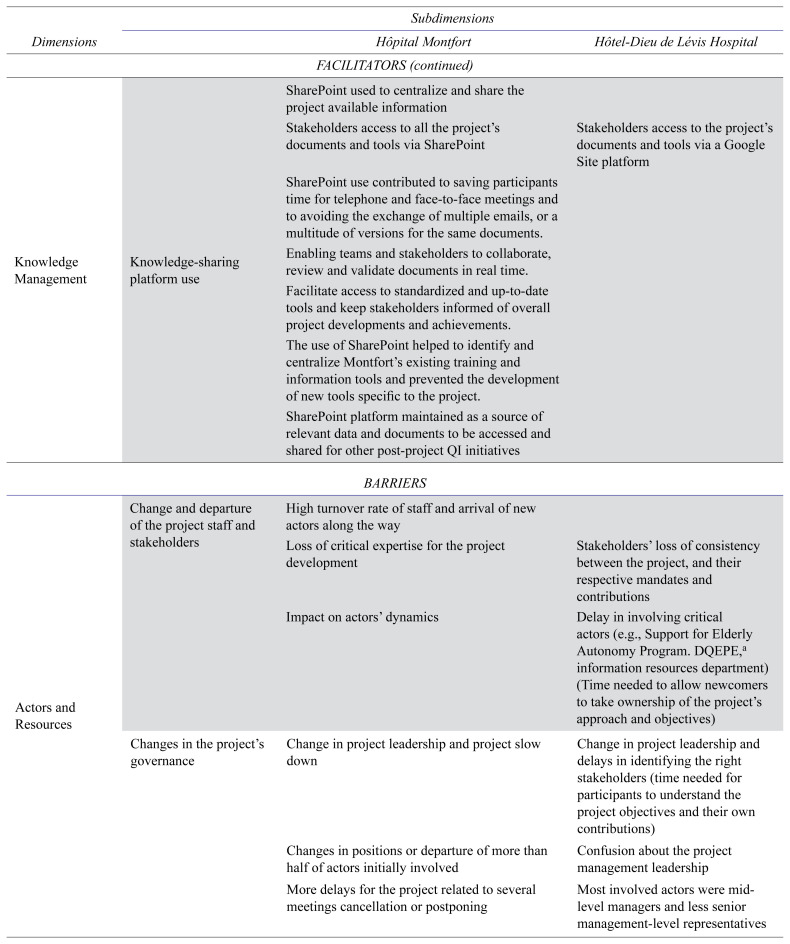

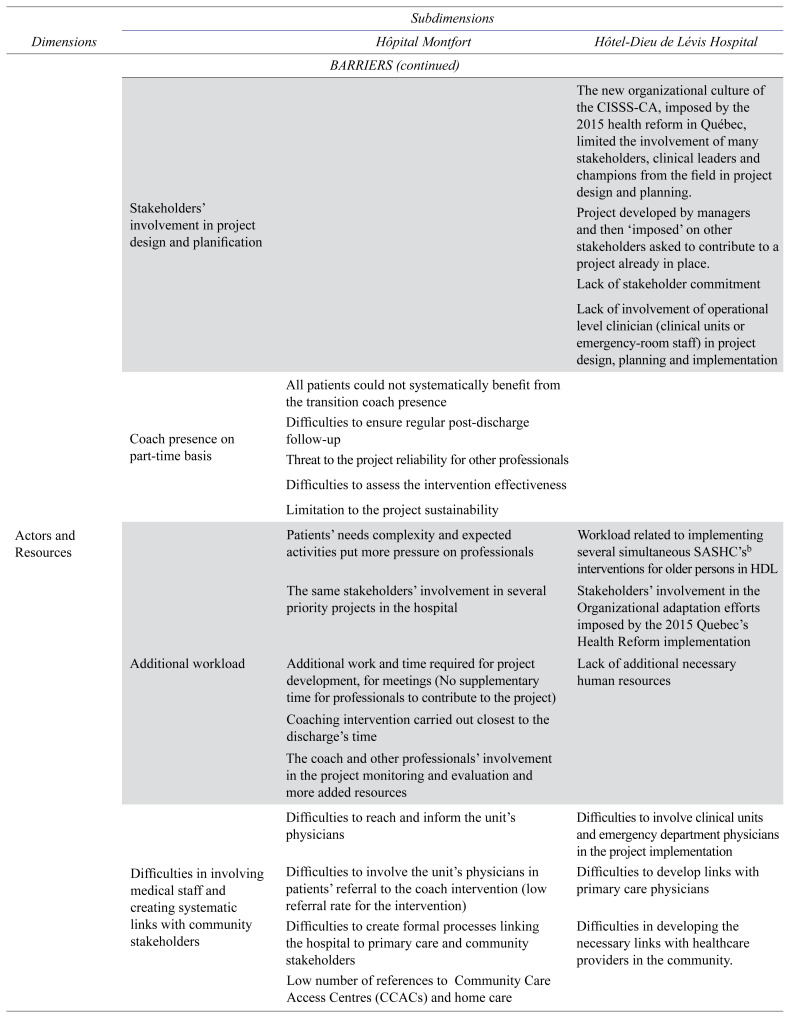

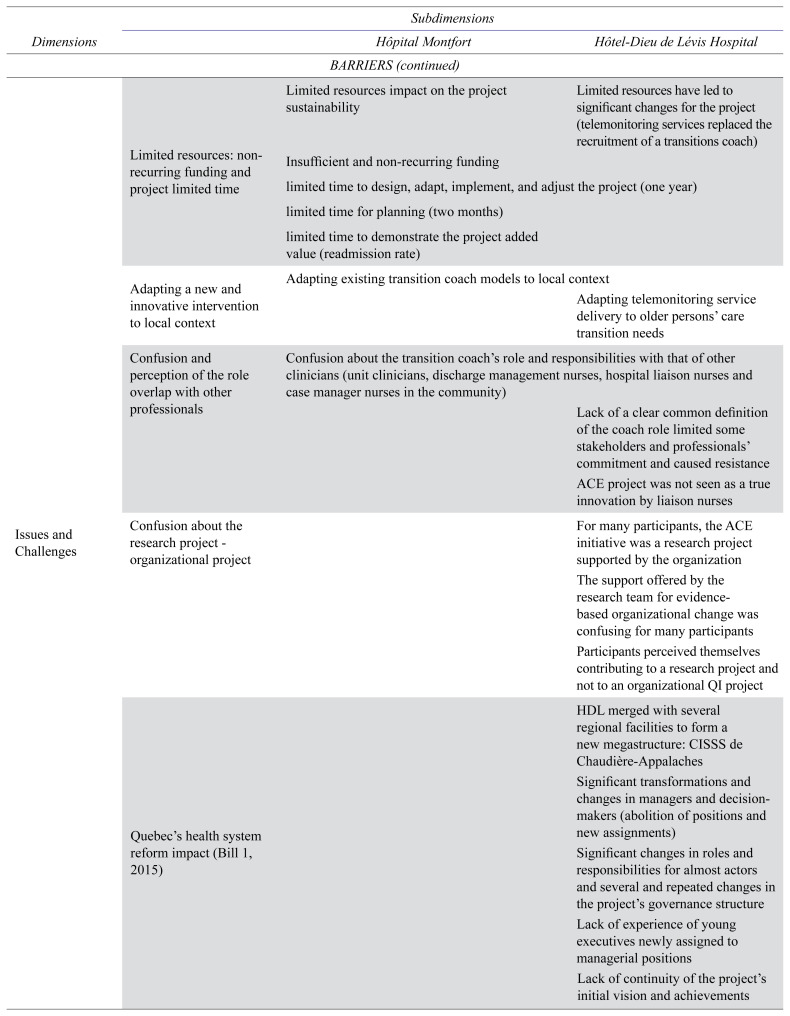

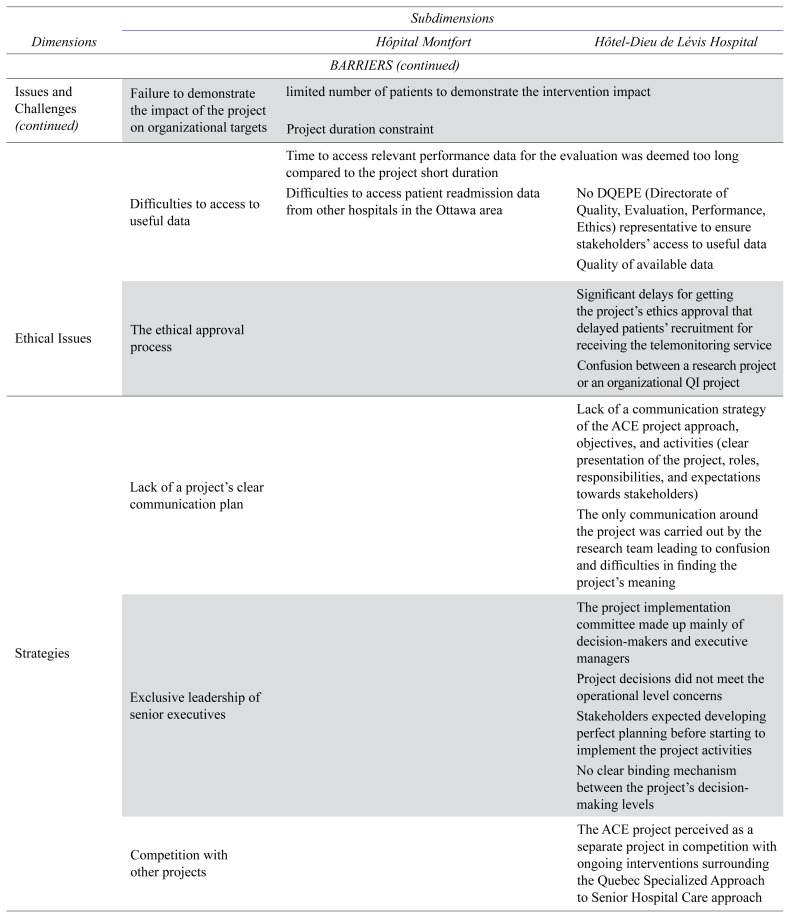

We analyzed the project facilitators and barriers according to our framework: actors and resources, theoretical approaches, issues and challenges, strategies, and knowledge transfer approaches.(14) Key barriers and facilitators are detailed in Appendix B. Appendix C provides citations for the dimensions and sub-dimensions of barriers and facilitators identified in our analysis.

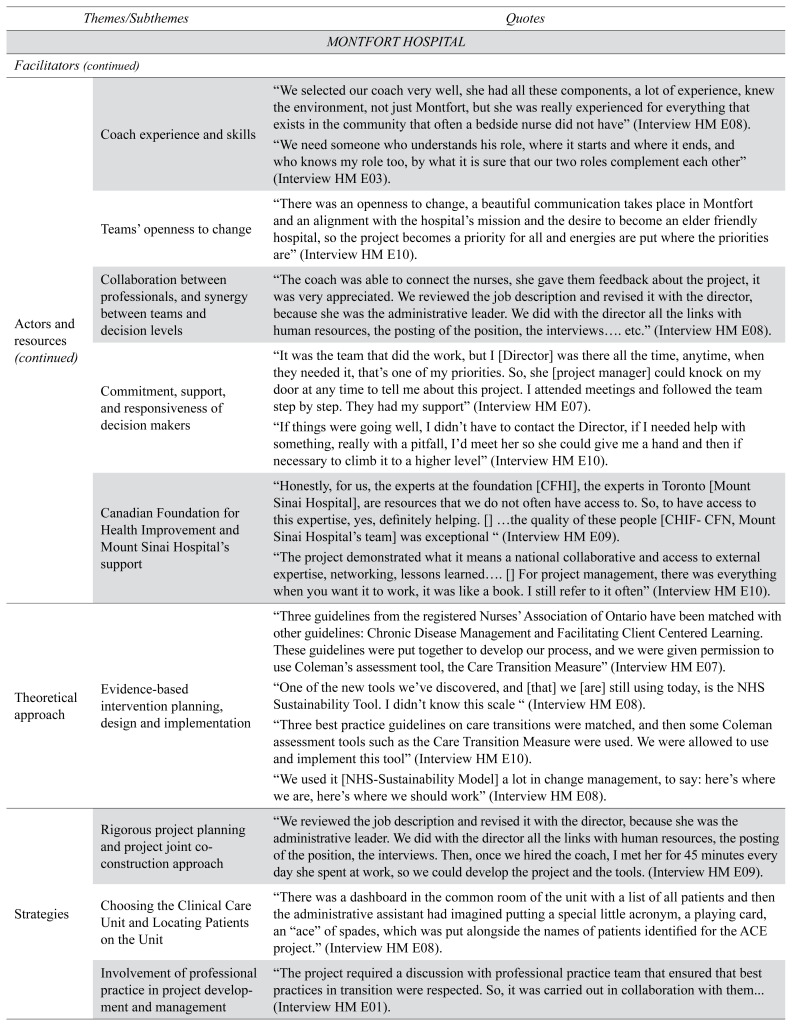

Facilitators at Hôpital Montfort

We identified the following facilitators, actors and resources: (1) the project manager’s clinical and organizational competencies, which facilitated project planning and implementation; (2) the transition coach’s clinical experience, skills, and knowledge; (3) the clinical and management teams’ openness to change; (4) the collaboration among clinicians and managers; (5) the decision-makers’ commitment, support, and responsiveness; and (6) the support and contributions of the CFHI, CFN and of Sinai Health. Theoretical approaches: Both the evidence-based ACE TCI and project management supported by the NHS Sustainability Model (NHS-SM) supported implementation. Strategies: Effective change strategies included (1) participative co-design and implementation; (2) mitigation of resistance to change; (3) continuous internal and external communication; (4) continuous QI approach; and (5) early focus on sustainability. Knowledge transfer approaches: The team used SharePoint (Microsoft, Redmond, CA, USA), a collaborative authoring and knowledge management platform that saved time and facilitated the sharing of data and documents.

Barriers at Hôpital Montfort

We identified the following barriers for actors and resources: (1) high human resource turnover (more than half of the initial team members changed positions); (2) the transition coach was only part-time; (3) additional workload for clinicians and team members; and (4) difficulty engaging medical staff and establishing community-based linkages (Community Care Access Centre (CCAC) home care providers). Issues and challenges: We found that: (1) the ACE project was limited in time and hampered by insufficient and non-recurrent funding; (2) adapting the intervention to local context proved challenging; (3) the transition coach’s role overlapped with the responsibilities of other professionals; (4) time constraints undermined the efforts of many stakeholders to help design and implement the project; (5) clinicians faced challenges in identifying frail elderly people; and (6) the project failed to demonstrate the impact on some organizational goals.

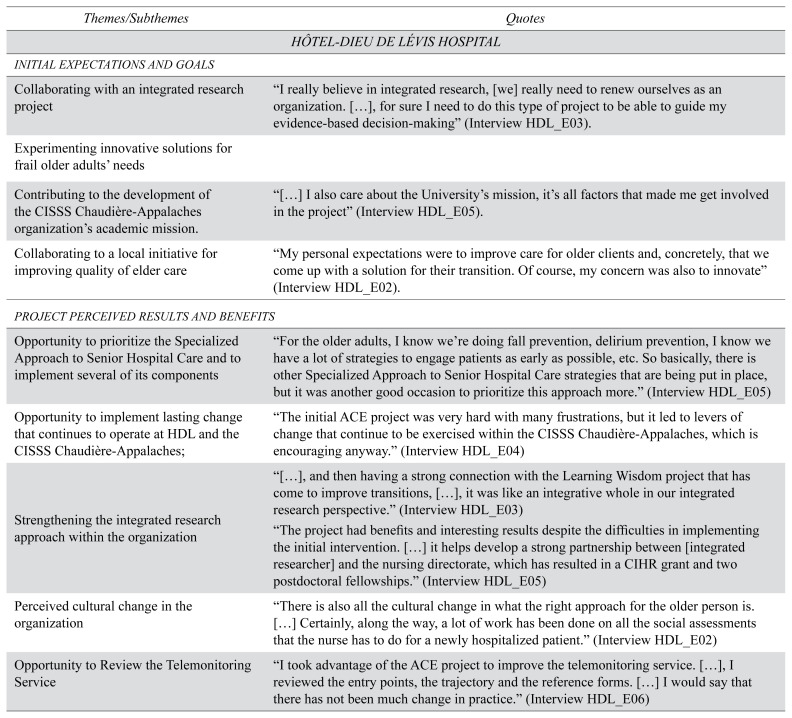

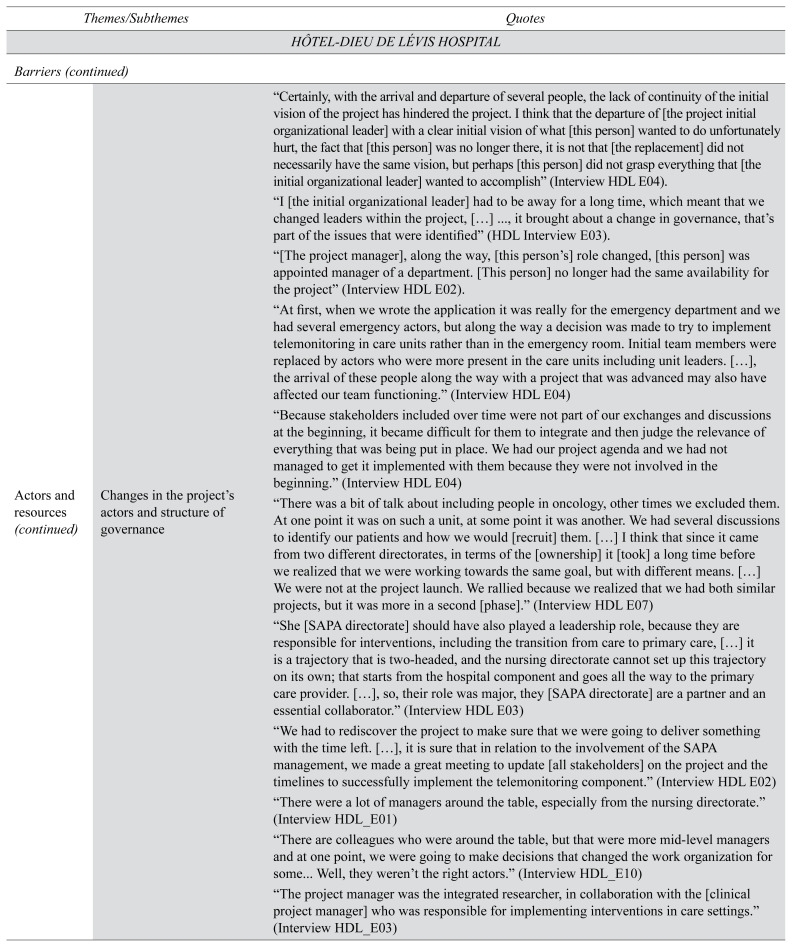

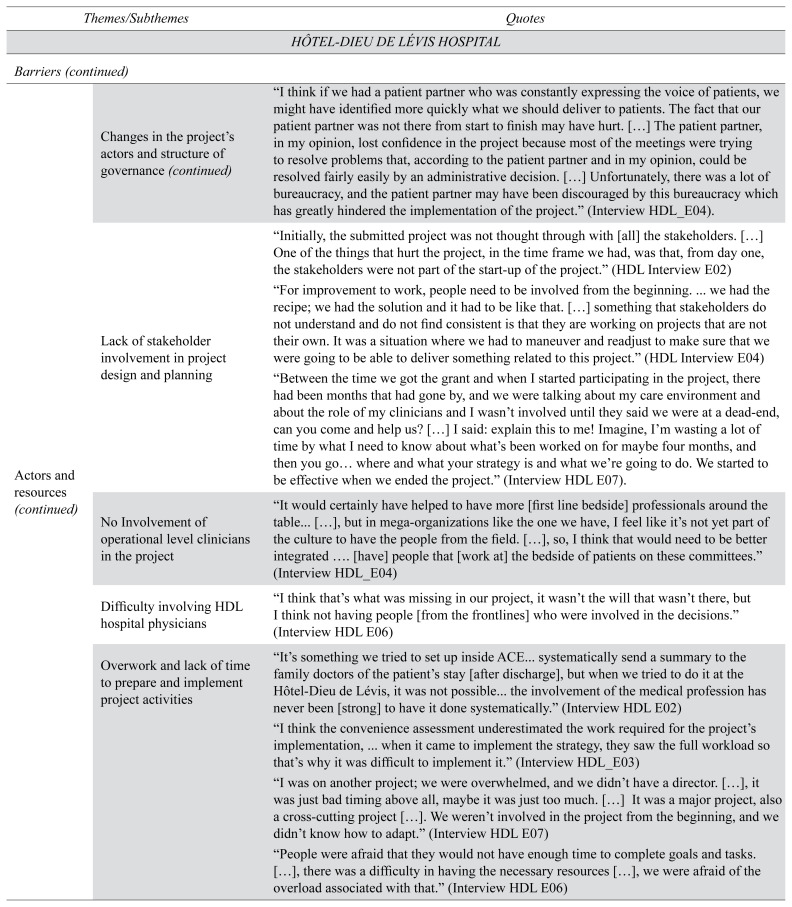

Facilitators at HDL Hospital

We identified the following facilitators regarding actors and resources: (1) nursing director and skilled project manager; (2) integrated research team; and (3) CFHI-CFN-Sinai Health financial support and mentorship. Theoretical approaches: We found that developing a guideline-based transition pathway (i.e., using the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario Care Transition Guideline(22)) facilitated local acceptability. Strategies: (1) Hiring a research nurse facilitated patient recruitment; (2) telemonitoring referrals; and (3) patient/caregiver completion of the telemonitoring referral form. Developing a video explaining the telemonitoring service was another helpful strategy. Knowledge transfer approaches: Using a Google Sites collaborative writing platform to support team knowledge management and document sharing facilitated the implementation of the ACE care transition component.

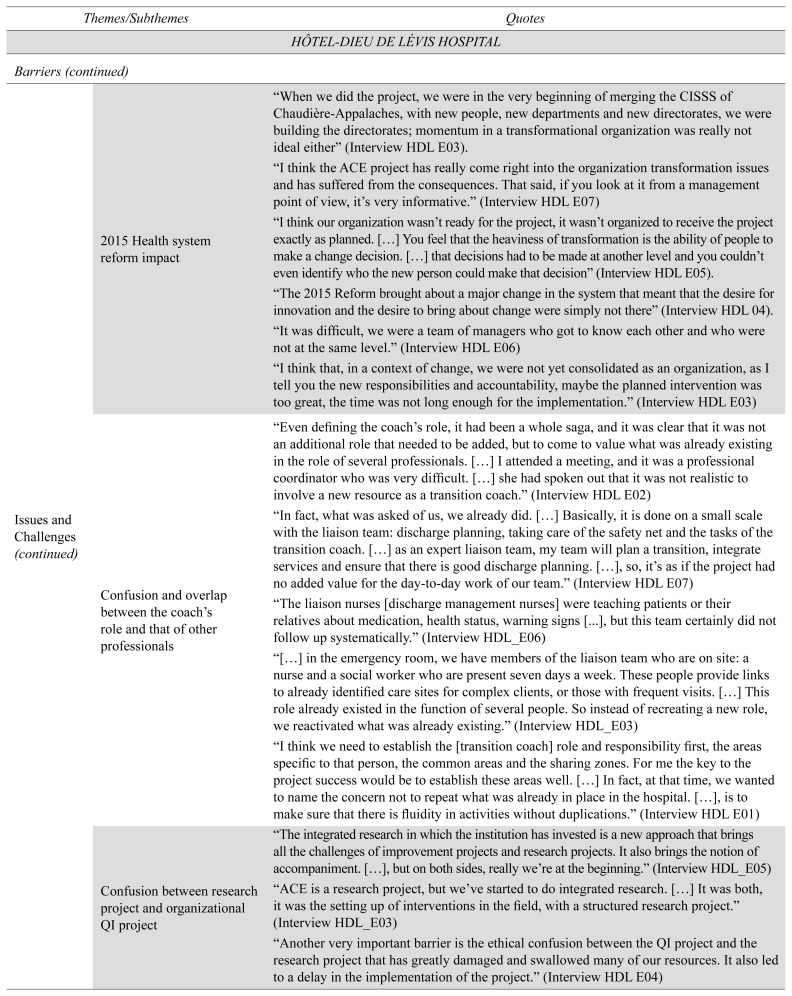

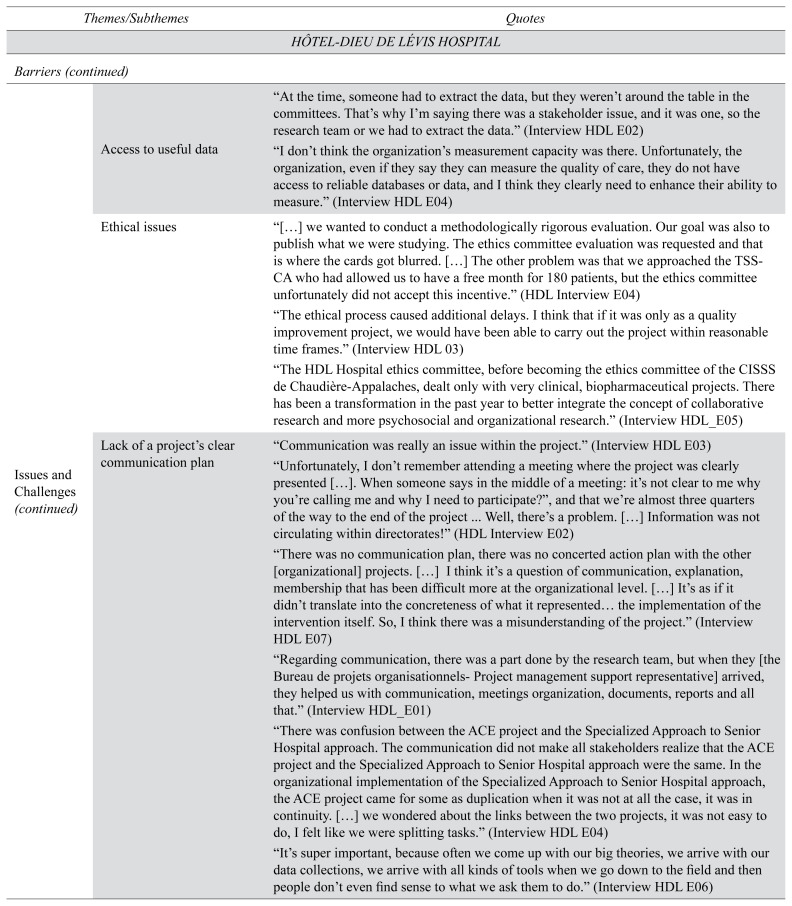

Barriers at HDL Hospital

The HDL team faced several difficulties that led to significant delays. Actors and resources: Major obstacles included: (1) limited human and financial resources; (2) changes in organizational leadership; (3) frequent turnover in key management roles; (4) changing governance structure; (5) lack of stakeholder involvement in project design and planning; (6) lack of involvement of frontline clinicians and physicians; (7) work overload from other concurrent initiatives; and (8) change in the intervention implementation site (the emergency department was changed to a regular medical ward). Issues and challenges: Quebec’s 2015 health-care reform (Quebec, Bill 1)(23) negatively impacted the project. Merging all Chaudière-Appalaches hospitals, community services and long-term care homes into one large health organization while eliminating many management positions created uncertainty and disorganization. Many newly appointed managers were not empowered to fully support the ACE project many months after the reform. There was also perceived overlap with the Quebec Specialized Approach to Senior Hospital Care, and existing liaison nurses’ duties. The lack of access to timely performance data was another barrier. There was also confusion about whether the project was a research project or a QI project. The ethics committee also struggled to understand the dual integrated research and QI status of the project, thus delaying the approval of the project. Finally, using Google Sites as the team’s knowledge-sharing platform raised cybersecurity risk issues. Strategies: Participants identified the following barriers: (1) lack of clear communication; (2) lack of clinical champions; (3) lack of communication between departments involved in the dysfunctional care transitions (e.g., hospital care to community care); (4) poor project planning to address clinical and operational concerns; and (5) selecting a technology-based intervention (i.e., telemonitoring) with complex care coordination challenges, access, and cost issues.

Conditions for Success and Sustainability

Table 3 shows the main conditions for success and determinants of sustainability for both QI projects identified through our qualitative analysis based on the theoretical framework. The findings are based on direct interviews with participants regarding their perceptions of the success and sustainability of the TCI.

TABLE 3.

Main conditions for success and sustainability for both quality improvement projects

| Conditions of Success | |

|---|---|

| External support | QI project supported by credible organizations and credentialed experts |

|

| |

| Organizational factors | Organizational stability and openness to change |

| Shared history of organizational change | |

| QI project based on clinical and organizational needs and in alignment with organizational, regional, and departmental priorities | |

| Accurate diagnosis of the problem and strategic selection of the solution to address it | |

|

| |

| Actors’ dynamics | Shared vision, developed with all stakeholders, of a common organizational QI project |

| Confirmed clinical leadership and solid support and responsiveness from the senior management team | |

| Actor dynamics aimed at changing practices and building consensus | |

|

| |

| Implementation strategies | Progressive/iterative approach supports incremental implementation |

|

| |

| Project management strategies | Plan, implement and manage projects based on evidence and successful experiences elsewhere |

| Integration of QI project governance into organizational decision-making process | |

| Collaborative, regular monitoring and ongoing communication of project progress | |

|

| |

| Determinants of Sustainability | |

|

| |

| Resources | Financial and human resources |

| Using relevant theoretical models and tools to systematically identify project sustainability conditions | |

|

| |

| Organizational factors | Developing interoperable information systems to support information continuity |

| Using knowledge management platforms | |

| Access to patient-level data and to performance indicators | |

| Access to the project financial cost-efficacy data | |

| Demonstrating the value and impact of QI interventions | |

|

| |

| Actors | Clinical leadership |

| Involvement of the physicians | |

| Developing more connections to increase awareness/involvement and partnerships with community stakeholders | |

DISCUSSION

In both hospitals, the ACE project demonstrated alignment with clinical and organizational priorities. Stakeholders at both hospitals cited access to external support, CFHI/Sinai Health experts, learning sessions, and access to knowledge tools and evidence-based strategies as facilitating factors for improvement. Participation in a national collaborative project allowed stakeholders to network, learn from other organizations, and discover the challenges different teams face and their strategies for overcoming them. Both hospitals used a collaborative approach to project development and implementation. Although the two projects had different outcomes, both teams learned numerous QI best practices and strategies. These continue to support sustainable change at both organizations. Understanding the key facilitating conditions and strategies used in both hospitals will benefit other centres planning the implementation of complex care transition interventions.

HM’s implementation strategies provided timely and effective guidance. HM undertook minor adjustments to the TCI design and implementation. In providing telemonitoring services to support older adults care transitions, HDL had to make significant project adjustments. Local stakeholders underestimated the complexity of new care transition projects especially when new technology is introduced.(24)

Both hospitals favoured a bottom-up approach to driving change. Adopting a bottom-up or top-down approach can make a big difference in driving clinical improvements in collaborative improvement projects.(25) To engage stakeholders, HM management team worked collaboratively and frequently communicated. Discussing evidence was key for ensuring project acceptability.(26) Senior management and CFHI experts helped HM overcome local barriers.(27) HM also used iterative implementation cycles.(28,29) Project milestones and accepted quality indicators were regularly tracked by all stakeholders. A recent review identified this as a facilitating factor.(30)

Prior to the ACE project, HM had a strong innovation and QI culture, all important in improving elder care transitions.(26,30,31) Like HM, HDL also embraced innovation and change. However, HDL’s efforts were focused elsewhere due to a major health reform (Quebec, Bill 1) and organizational restructuring. With high staff turnover and changing roles and responsibilities, many managers didn’t have enough time to fully understand their new roles or engage clinical leadership, a critical success factor for QI initiatives.(28) Establishing a governance structure and team composition took many months. Such systemic changes and team member instability disrupt QI projects.(28)

The ACE project was also one of HDL’s first experiences with an innovative form of integrated research supporting evidence-based organizational change. The integrated research team played a major role in engaging stakeholders, and in designing and implementing the ACE project. Involving an embedded clinician-researcher was confusing to some professionals who felt they were contributing to research rather than organizational QI. Although integrated research promises to support learning health-care organizations, many challenges remain, including creating a collaborative research/clinical culture where stakeholders work together in a trusting and open relationship to sustainably improve health system outcomes.(32) This first integrated research experience provided a strong, sustainable foundation for future integrated research. Several ongoing spin-off projects continue the work started during the ACE project.(6,33)

Finally, sustainability was an early concern for CFHI leaders. MH used the NHS-SM to monitor and manage change.(34) Addressing sustainability early helps participants avoid wasted effort and highlight the collective benefits of QI initiatives.(29,34) In both centres, three issues limited organizational capacity to measure sustainability: (1) barriers to accessing timely data; (2) lack of data systems for project performance monitoring and data analysis; and (3) lack of interoperable information systems to measure care continuity across transitions.

Our results complement the conclusions of the Acute Care for Elders Strategy Sustainment and Sustainability Study (ACES-SSS).(35) Similar to our study, ACES-SSS compared the sustainability of two different in-patient ACE interventions at two other ACE Collaborative intervention sites: a rural and remote community hospital (Whitehorse General Hospital) and an academic-affiliated hospital (Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre). Our study differed from ACES-SSS because we only focused on a TCI in two different hospitals with similar academic backgrounds, while ACES-SSSS studied the sustainment and sustainability of two in-patient care interventions in two different academic settings: the Braden Skin Assessment at the Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre and an ACE unit to offer optimal evidence-based in-patient acute care for older adults at the Whitehorse General Hospital. The ACES-SSSS found that adaptations to evidence-based interventions which respect as much as possible the fidelity of the original intervention are more likely to be sustainable. We also found this to be the case at HDL, where the TCI was adapted to the point that it differed significantly from the TCI implemented at HM and quite differently from the original TCI developed by Coleman et al.,(11) ultimately leading to successful sustainability at HM compared to HDL. Similar to Rappon,(35) we also found that frequent staff turnover and rapidly changing organizational priorities were major barriers to sustainability in both HM and HDL study sites. A common facilitator identified in both studies was the highly valued support of CFHI and Sinai Health experts in the form of additional funding, clinical expertise, and change management expertise. Our study adds to the ACES-SSS and existing implementation science literature by suggesting several facilitators to consider when adapting an evidence-based innovation to new organizations with different provincial contexts and change management cultures: minimal adaptation to the original evidence-based intervention; use of a collaborative, bottom-up approach; use of a theoretical model to support sustainability; support from clinical and organizational leadership; a strong organizational culture for QI; access to timely quality measures; financial support; use of a knowledge management platform; and involvement of an integrated research team and expert guidance.

Our study has several strengths. First, we interviewed a large sample of key participants representing a range of clinical, policy, and managerial stakeholders. We also included the patient perspective by involving a patient partner from HM. We used rigorous qualitative analysis methods, including focus group validation of our findings. Our rigorous approach and large sample size support generalizability to other Canadian francophone hospitals.

We also acknowledge some limitations. First, our retrospective analysis could be exposed to recall bias. Second, we were only able to report on the perspective of a single patient partner. Finally, analyzing other ACE Collaborative sites’ experiences, including international sites, would have provided more diverse and generalizable results.

CONCLUSION

We compared the implementation of a care transition intervention in two French-Canadian hospitals participating in an Acute Care for Elders QI collaborative. Emerging lessons and strategies will help clinicians, managers, and policymakers better address the challenges of implementing complex evidence-based care transition interventions. Notably, minimizing adaptations to original evidence-based interventions, using a bottom-up collaborative approach supported by strong clinical and organizational leadership, strong organizational culture for quality improvement, access to timely quality indicators, financial support, use of a knowledge management platform, and involvement of an integrated research team and expert guidance are key factors to successful care transition quality improvement projects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the two hospitals for supporting this study, as well as everyone who agreed to participate as key informants. We would also like to thank Thérèse Antoun and Linda Lessard for their assistance with access to key informants and the relevant data, and Denis Roy for supporting the first author and feeding our reflections during the writing of the manuscript.

APPENDIX A. ACE project initial expectations and perceived results

| Hôpital Montfort | Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis |

|---|---|

| Initial Expectations and Goals | |

| Organizational Expectations | |

| Reducing hospital readmission rates in frail elderly people represented the “real expectation”. | Improving the quality of care for vulnerable older adults. |

| Implementing a standardized approach to providing education for older adults and their families. | Implementing an intervention supporting elders’ safe transition of care |

| Improving older adults and their families’ satisfaction with care transitions. | Contributing to the development of the CISSS Chaudière-Appalaches organization’s academic mission. |

| Developing and strengthening links with health resources available in the community | Collaborating to a local initiative for improving quality of elder care. |

| Personal Expectations | |

| Personal sensitivity to elders’ quality of care | Experimenting innovative solutions for frail older adults’ needs |

| Participants’ commitment to develop initiatives aiming to support frail elderly people and family education and information. | Collaborating with an integrated research project |

| Clinicians and professional practice managers personal interest in standardizing the nurses’ role in elder care transitions according to best practices | |

| Clinicians and professional practice managers have a personal interest in demonstrating the project’s direct contribution to older adults’ quality of care, chronic diseases management and patients and family satisfaction. | |

| Strengthening the role of nurses in health promotion activities for these patients. | |

| Managers’ personal expectations were in line with organizational ones: reducing hospital readmission rates, reducing length of stay; developing a standardized approach to older adults’ care transition | |

| Perceived Project Results | |

| ACE project emphasized the need to think about frail elderly people’s transition of care issues; | ACE project as conducted did not achieve tangible results for patients or professionals. |

| ACE project helped identify, adapt, and implement transition of care best practices and activities; | ACE project did result in any change in nurses’ clinical practice |

| ACE project improved stakeholder knowledge and skills related to care transitions (the coach kept nurses informed about evidence-based practices and trained them on the use of new assessment and teaching tools (e.g., Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), “Teach Back” teaching technique; CTM3); | HDL and CISSS CA’s participation in this project represented a unique opportunity to implement processes of lasting change that continue to operate at HDL and more largely in the CISSS Chaudière-Appalaches; |

| ACE project helped harmonize certain care transition activities; (the major outcome identified at Hôpital Montfort) | The project was an opportunity to raise awareness about the needs of frail older adults along the trajectory of care with an emphasis on areas of care transitions; |

| ACE project helped select the relevant tools available for frail elderly people’s tracking, evaluation, and teachinga | The project was an opportunity to initiate a cultural change in the organization; |

| ACE project supported other team members’ work; | The project helped to prioritize the Specialized Approach to Senior Hospital Care and to implement several of its components;b |

| ACE project created more links with and within clinical teams; | The project helped strengthen the integrated research approach to support changes within the organization;c |

| ACE project supported a pharmacist to develop specific practices for frail elderly people (education and sharing information about medication changes with community health providers) | The dynamics that emerged from participation in the ACE project reduced barriers between research and practice and increased awareness about the benefits of integrated research in supporting organizational projects;d |

| ACE project created more links with the primary care providers and resources in the community (formal hospital discharge summary including discharge medication reconciliation; letter reminding family doctors to schedule a follow-up appointment); | ACE project was an opportunity to activate a “notice of admission” alert developed by the Support for Elderly Autonomy Program Directorate (SEAP) and Nursing Directorate, to inform Local Community Service Center (“CLSC”) professionals about an elderly patient’s hospital admission or emergency room visit; |

| The project helped establish some links with Community Care Access Centers’ (CCAC) (Rapid Response Nurses (RRN)e program for home visits and follow-up in the community. | The project was an opportunity to review the telemonitoring service referral and care trajectory processes; |

| The project contributed to improving clinicians’ satisfaction towards activities supporting the quality-of-care transitions and teamwork; | The project was an opportunity to review and harmonize the referral form allowing telemonitoring nurses to properly identify frail elderly people and helping liaison nurses identify and refer these people to the telemonitoring service. |

These changes remained on the unit after the end of the project.

For example, the implementation of the Emergency Geriatric Nurse Project (GEM Nurse), the design of a project to assess the impact of telemonitoring use for older persons with high use of emergency rooms.

The integrated research team obtained, in collaboration with the Director of Nursing, funding from CIHR to conduct a second phase of the ACE project, on a larger scale in the CISSS CA (Learning Wisdom Project(6)). Also, a team member was able to obtain a CIHR Postdoctoral Health System Impact Fellowship (https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51211.html).

Several partnerships have been developed between the research team and two CISSS Chaudière-Appalaches Directorates, whose managers are currently acting as co-investigators and knowledge users in several research projects. Collaborative links were also noted between researchers, managers and clinicians from emergency departments and some care units.

The Rapid Response Nursing program is a dedicated team of Registered Nurses providing a variety of intensive in-home services to patients with complex care needs and their families to support smooth and safe transitions from hospital to the patient’s home (http://healthcareathome.ca/centraleast/en/care/patient/Documents/Rapid-Response-Nurses-Fact-Sheet.pdf).

APPENDIX B. Facilitators and barriers to the implementation of the ACE projects at Hôpital Montfort and Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis

| Dimensions | Subdimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hôpital Montfort | Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis Hospital | ||

| Actors And Resources | FACILITATORS | ||

|

| |||

| Project Manager’s Clinical and Organizational Competencies and Skills | Personal and professional experiences, qualities, and skills | Contribution to the preliminary discussions about the project | |

| Development of a transition coach job description | Planning of the QI project | ||

| Professional competency development support | Contribution to the QI project design and implementation | ||

| Leadership, communication skills and support to clinical teams | Revision of the selection criteria and reference algorithm for the new telemonitoring service | ||

| Engagement of key actors | Implementation of a referral decision algorithm, referral form, and information handouts | ||

| Strong managerial capacity to resolving problems, managing, and monitoring the project | |||

|

| |||

| Transitions Coach Knowledge, Experience and Skills | Clinical and geriatric experience | ||

| Comprehensive knowledge of available in-hospital and primary care resources | |||

|

| |||

| Stakeholders and Teams’ openness to change | Stakeholders and teams’ openness to the proposed changes | ||

| previous experience in IQ projects | |||

|

| |||

| Collaboration between professionals | Synergy and complementarity between new Transitions Coach role and existing professionals | ||

| Collaboration among clinical and management teams | |||

| In-hospital multidisciplinary team identification of frail elderly patients | |||

| Coordination of care with community services | |||

|

| |||

| Synergy between the QI team and mid and upper management | Synergy between the project’s management team and upper management | ||

| Efficient bilateral communication | |||

| Adequate decisions and problem solving by upper management | |||

|

| |||

| Commitment, support, and responsiveness of upper management | Active contribution by upper management (Director of Medicine, Geriatrics and Rehabilitation) to local ACE QI project design, co-construction and roll out | Upper management (Director of Nursing) involved in project discussions, planning and implementation | |

| Decision-making flexibility | Strong leadership from the beginning | ||

| Ongoing availability and support for middle management (project manager) and clinical teams to ensure regular follow-up and quick responses to project difficulties | |||

| Delegation of several responsibilities to the project manager | |||

|

| |||

| Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement (CFHI) and Mount Sinai Hospital’s Support and contribution | CFHI and Mount Sinai’s experts’ support and coaching for a year (monthly forums and webinars) | ||

| Additional funding provided to support a QI project | |||

| Networking and opportunity to learn from a national collaborative (sharing information, experience, tools and lessons learned about different teams’ challenges and strategies | |||

| Tools to support the ACE project implementation and change management | |||

| Tools to support clinical teams’ activities (priority setting, needs assessment, identification of adequate stakeholders and partners, reviewing project charter, identifying improvement targets, and defining monitoring indicators) | |||

| National collaborative perceived to support sustainability | |||

|

| |||

| Research team contribution | Major role in applying for the funding from CFHI | ||

| Great contribution to designing an evidence-based project, engaging stakeholders, and implementing the local QI project | |||

| Proposal of different novel evidence-based interventions to support care transitions | |||

| Novel strategies to support practice change (e.g., patient engagement) and evidence-based decision-making | |||

| Baseline assessment and project performance monitoring and measurement | |||

| Support to developing evidence-based knowledge tools | |||

| Co-coordination of project team’s local activities | |||

| Communications and drafting of progress and final reports for CFHI | |||

| Hiring new human resources to support the QI project | |||

| Project evaluation | |||

|

| |||

| Theoretical Approach for Evidence-Based Intervention Planning, Design, and Implementation | Literature review | Literature reviews on good practices in care transitions | Literature reviews on good practices in care transitions |

|

| |||

| Using care transition best practice and clinical guidelines | Care Transitions Program | ||

| Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO) guidelines (Care Transitions, Strategies to Support Self-Management in Chronic Conditions and Facilitating Client Centered Learning) | |||

| Improving the Continuum of Care Advisory Committee Report on Preventable Hospitalizations (USA) | |||

| Use of project management best practices (A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) | |||

|

| |||

| Theoretical frameworks use and learning from successful transition coach experiences in Canada and around the world | NHS Sustainability Model questionnaire to support the project implementation, change management and monitoring. | ACE Continuum (Mount Sinai Health System in Toronto) | |

| The ACE Continuum of Mount Sinai health system in Toronto | Care Transitions Program | ||

| Care Transitions Program by Coleman in the United States | BOOST project (Better Outcomes | ||

| Through Optimizing Safe Transitions) | |||

| Project RED: Re-Engineered Discharge | |||

| Guidelines for Improving the Continuum of Care Advisory Committee Report | |||

|

| |||

| Strategies | Rigorous project planning and a joint co-construction approach | A preparation period supported by CFHI and Mount Sinai experts. | |

| The project alignment with stakeholders’ objectives and priorities | |||

| Stakeholders’ contribution to set organizational objectives and teams’ expectations | |||

| Rigorous definition of roles, responsibilities, and relationships with internal and external stakeholders | |||

| Coach and clinical team members involvement in identifying main tasks, developing necessary tools and in the project planning and management | |||

|

| |||

| A participatory and inclusive approach for the project development and implementation | The project joint co-construction based on concerted choices | ||

| Leaders and key stakeholders’ early inclusion to ensure acceptability | |||

|

| |||

| Patient recruitment for telemonitoring | Hiring a research nurse to inform patients about the telemonitoring service | ||

| Development of a promotional video explaining the telemonitoring service | |||

| Patient and caregivers’ involvement in the telemonitoring request form completion | |||

|

| |||

| Choosing the clinical care unit and locating patients on the unit | Choice criteria for identifying clinical unit and eligible patients carefully identified jointly by the management team, clinical teams including a patient partner, and other stakeholders | ||

|

| |||

| Preparation work to reduce team resistance | Raising key stakeholders’ awareness of the frail elderly people’s care transition difficulties and to inform them of the ACE strategy | ||

| Key stakeholders’ information about the ACE strategy | |||

| The project manager, clinical unit manager and the coach regular meetings with small groups of stakeholders | |||

| Seeking stakeholders’ opinions and suggestions on the project design, management, and implementation issues | |||

| Clarification of the coach’s own attributes and activities to other clinicians and to facilitate stakeholders’ adherence | |||

|

| |||

| Internal and external continuous communication | Early continuous internal and external communication of the intervention chosen, coach attributes, targeted patients, project teams’ members and leaders to all stakeholders | ||

| The communication of the project’s vision and objectives supported by local champions (geriatrician and a family physician) | |||

| Regular communication of decisions and the project evolution to all stakeholders | |||

| Choosing Appropriate means at each stage to transmit the relevant information to stakeholders (internal memo, emails and presentations during meetings: project management meetings, interdisciplinary and departmental meetings) | |||

| Sharing meeting summaries with all stakeholders, including those unable to attend the project regular meetings. | |||

| Personalized approach to inform actors individually or to some specific groups (e.g., hospital physicians, community physicians and teams, clinical unit therapeutic service team, occupational therapy follow-up team...) | |||

|

| |||

| Integration of a continuous QI approach | The ACE project collective follow-up | ||

| Collective regular monitoring of organizational targets | |||

| NHS-SM questionnaire use to facilitate change management | |||

|

| |||

| Concern about sustainability determinants early in the implementation process | NHS-SM questionnaire use to support sustainability | ||

|

| |||

| Knowledge Management | Knowledge-sharing platform use | SharePoint used to centralize and share the project available information | |

| Stakeholders access to all the project’s documents and tools via SharePoint | Stakeholders access to the project’s documents and tools via a Google Site platform | ||

| SharePoint use contributed to saving participants time for telephone and face-to-face meetings and to avoiding the exchange of multiple emails, or a multitude of versions for the same documents. | |||

| Enabling teams and stakeholders to collaborate, review and validate documents in real time. | |||

| Facilitate access to standardized and up-to-date tools and keep stakeholders informed of overall project developments and achievements. | |||

| The use of SharePoint helped to identify and centralize Montfort’s existing training and information tools and prevented the development of new tools specific to the project. | |||

| SharePoint platform maintained as a source of relevant data and documents to be accessed and shared for other post-project QI initiatives | |||

|

| |||

| BARRIERS | |||

|

| |||

| Actors and Resources | Change and departure of the project staff and stakeholders | High turnover rate of staff and arrival of new actors along the way | |

| Loss of critical expertise for the project development | Stakeholders’ loss of consistency between the project, and their respective mandates and contributions | ||

| Impact on actors’ dynamics | Delay in involving critical actors (e.g., Support for Elderly Autonomy Program. DQEPE,a information resources department) (Time needed to allow newcomers to take ownership of the project’s approach and objectives) | ||

|

| |||

| Changes in the project’s governance | Change in project leadership and project slow down | Change in project leadership and delays in identifying the right stakeholders (time needed for participants to understand the project objectives and their own contributions) | |

| Changes in positions or departure of more than half of actors initially involved | Confusion about the project management leadership | ||

| More delays for the project related to several meetings cancellation or postponing | Most involved actors were mid-level managers and less senior management-level representatives | ||

|

| |||

| Stakeholders’ involvement in project design and planification | The new organizational culture of the CISSS-CA, imposed by the 2015 health reform in Québec, limited the involvement of many stakeholders, clinical leaders and champions from the field in project design and planning. | ||

| Project developed by managers and then ‘imposed’ on other stakeholders asked to contribute to a project already in place. | |||

| Lack of stakeholder commitment | |||

| Lack of involvement of operational level clinician (clinical units or emergency-room staff) in project design, planning and implementation | |||

|

| |||

| Coach presence on part-time basis | All patients could not systematically benefit from the transition coach presence | ||

| Difficulties to ensure regular post-discharge follow-up | |||

| Threat to the project reliability for other professionals | |||

| Difficulties to assess the intervention effectiveness | |||

| Limitation to the project sustainability | |||

|

| |||

| Additional workload | Patients’ needs complexity and expected activities put more pressure on professionals | Workload related to implementing several simultaneous SASHC’sb interventions for older persons in HDL | |

| The same stakeholders’ involvement in several priority projects in the hospital | Stakeholders’ involvement in the Organizational adaptation efforts imposed by the 2015 Quebec’s Health Reform implementation | ||

| Additional work and time required for project development, for meetings (No supplementary time for professionals to contribute to the project) | Lack of additional necessary human resources | ||

| Coaching intervention carried out closest to the discharge’s time | |||

| The coach and other professionals’ involvement in the project monitoring and evaluation and more added resources | |||

|

| |||

| Difficulties in involving medical staff and creating systematic links with community stakeholders | Difficulties to reach and inform the unit’s physicians | Difficulties to involve clinical units and emergency department physicians in the project implementation | |

| Difficulties to involve the unit’s physicians in patients’ referral to the coach intervention (low referral rate for the intervention) | Difficulties to develop links with primary care physicians | ||

| Difficulties to create formal processes linking the hospital to primary care and community stakeholders | Difficulties in developing the necessary links with healthcare providers in the community. | ||

| Low number of references to Community Care Access Centres (CCACs) and home care | |||

|

| |||

| Issues and Challenges | Limited resources: non-recurring funding and project limited time | Limited resources impact on the project sustainability | Limited resources have led to significant changes for the project (telemonitoring services replaced the recruitment of a transitions coach) |

| Insufficient and non-recurring funding | |||

| limited time to design, adapt, implement, and adjust the project (one year) | |||

| limited time for planning (two months) | |||

| limited time to demonstrate the project added value (readmission rate) | |||

|

| |||

| Adapting a new and innovative intervention to local context | Adapting existing transition coach models to local context | ||

| Adapting telemonitoring service delivery to older persons’ care transition needs | |||

|

| |||

| Confusion and perception of the role overlap with other professionals | Confusion about the transition coach’s role and responsibilities with that of other clinicians (unit clinicians, discharge management nurses, hospital liaison nurses and case manager nurses in the community) | ||

| Lack of a clear common definition of the coach role limited some stakeholders and professionals’ commitment and caused resistance | |||

| ACE project was not seen as a true innovation by liaison nurses | |||

|

| |||

| Confusion about the research project - organizational project | For many participants, the ACE initiative was a research project supported by the organization | ||

| The support offered by the research team for evidence-based organizational change was confusing for many participants | |||

| Participants perceived themselves contributing to a research project and not to an organizational QI project | |||

|

| |||

| Quebec’s health system reform impact (Bill 1, 2015) | HDL merged with several regional facilities to form a new megastructure: CISSS de Chaudière-Appalaches | ||

| Significant transformations and changes in managers and decision-makers (abolition of positions and new assignments) | |||

| Significant changes in roles and responsibilities for almost actors and several and repeated changes in the project’s governance structure | |||

| Lack of experience of young executives newly assigned to managerial positions | |||

| Lack of continuity of the project’s initial vision and achievements | |||

| Failure to demonstrate the impact of the project on organizational targets | limited number of patients to demonstrate the intervention impact | ||

| Project duration constraint | |||

|

| |||

| Difficulties to access to useful data | Time to access relevant performance data for the evaluation was deemed too long compared to the project short duration | ||

| Difficulties to access patient readmission data from other hospitals in the Ottawa area | No DQEPE (Directorate of Quality, Evaluation, Performance, Ethics) representative to ensure stakeholders’ access to useful data | ||

| Quality of available data | |||

|

|

|||

| Ethical Issues | The ethical approval process | Significant delays for getting the project’s ethics approval that delayed patients’ recruitment for receiving the telemonitoring service | |

| Confusion between a research project or an organizational QI project | |||

|

| |||

| Strategies | Lack of a project’s clear communication plan | Lack of a communication strategy of the ACE project approach, objectives, and activities (clear presentation of the project, roles, responsibilities, and expectations towards stakeholders) | |

| The only communication around the project was carried out by the research team leading to confusion and difficulties in finding the project’s meaning | |||

|

| |||

| Exclusive leadership of senior executives | The project implementation committee made up mainly of decision-makers and executive managers | ||

| Project decisions did not meet the operational level concerns | |||

| Stakeholders expected developing perfect planning before starting to implement the project activities | |||

| No clear binding mechanism between the project’s decision-making levels | |||

|

| |||

| Competition with other projects | The ACE project perceived as a separate project in competition with ongoing interventions surrounding the Quebec Specialized Approach to Senior Hospital Care approach | ||

|

| |||

| Implementing telemonitoring as a “complex” technological innovation | Challenges associated with the telemonitoring service implementation as a complex technology for care and services delivery (need to review the telemonitoring recruitment and referral processes) | ||

| Need for revising actors’ roles and responsibilities and for establishing a new trajectory involving hospital units, emergency department and community healthcare providers | |||

| Technological issues related to the equipment availability, patient acceptance and consent. | |||

| The challenges of technology cost and use for older persons. | |||

|

| |||

| Knowledge Management | Knowledge-sharing platform use | Google Sites platform blocked by the organization’s Information Resources Directorate for security issues | |

| Limited access and sharing of useful information and documents | |||

A Directorate of Quality, Evaluation, Performance, Ethics.

Quebec’s Specialized Approach to Senior Hospital Care.

APPENDIX C. Key themes related to initial expectations and goals, facilitators and barriers, and related verbatim quotes

| Themes/Subthemes | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| MONTFORT HOSPITAL | ||

|

| ||

| INITIAL EXPECTATIONS AND GOALS | ||

|

| ||

| Organizational expectations | “The real expectation was to reduce readmission rates for the elderly and frail patients. So that was really our ultimate expected result” (Interview HM E10). | |

|

| ||

| “In Montfort, our big challenge was getting patients out. []…. We also wanted to engage our family physicians in the community to be aware of our hospital orientations and to get their contribution” (Interview HM E08). | ||

|

| ||

| Personal expectations | “I have a sensitivity to the needs of the elderly I personally believe in it deeply, [] these are my personal values” (Interview HM E7). | |

| “it’s really about transition to the community with real support, something to formalize that would make it a direct and well-marked relationship with the community, []. It’s something that’s been close to my heart for a very long time” (Interview HM E4). | ||

|

| ||

| PERCEIVED PROJECT RESULTS | ||

|

| ||

| Identifying a new role | “But this role is really different! I would [say] a hybrid between a bedside nurse, a social worker and then the coach also had to know very well about community services” (Interview HM E08). | |

|

| ||

| Care transition activities standardization | “The biggest change was really having a standardized role in care transition “ (Interview HM E10). | |

|

| ||

| Improving transition care knowledge and skills in other teams | “There has been an increase in the knowledge and skills of the team. These teams are probably better equipped than any other care unit” (Interview HM E08). | |

|

| ||

| Support to other team members’ activities related to care transition | “The coach was able to connect the nurses, she gave them feedback about the project, it was very appreciated.” (Interview HM E10). | |

| “It takes away a certain workload from the nurse who cares less about teaching, because there was a dedicated resource specifically for these patients. [] I’ll tell you that this is probably the biggest impact for the team” (Interview HM E01). | ||

|

| ||

| Useful relationship creation (with clinical teams) | “If I had not seen the client yet, she [coach] could track things I should know. And if there was a need for the coach intervention, I could talk to her about that client” (Interview HM E03). | |

|

| ||

| Selection and use of relevant tools | “When we developed the project, we learned a lot of lessons about benefits and strengths of a program to prepare for seniors’ discharge. [] We tested tools that we can use with other patients” (Interview HM E10). | |

| “There are not enough pharmacists to see all seniors, and we have to prioritize. I would say that the patients who were identified by the fragility score were not necessarily the patients we would have seen outside of this project” (Interview HM E04). | ||

|

| ||

| Clinician satisfaction | “Certainly, it gives satisfaction with doing something that worked well. We’ve accomplished something, so it contributes to job satisfaction and commitment”. (Interview HM E04). | |

|

| ||

| Performing follow-up for frail older adults | “I would say that the most important thing I noticed with the patients was the post-discharge calls, because they really felt like we were participating in their care after they left, that we were worried about their return home, if they had any questions, we could answer them” (Interview HM E2). | |

|

| ||

| Organizational change support | “This project has been a lever for change in the hospital, but also allowing us to look outwards to present our provincial initiatives” (Interview HM E10). | |

|

| ||

| FACILITATORS AND BARRIERS | ||

|

| ||

| Facilitators | ||

|

| ||

| Actors and resources | Project manager’s competencies and skills | “Within the team, [the project manager] is the kind of leading nurse you want. She knows the rigour; she is professional and can engage people. She’s the kind of key people in the hospital. After having known her, she is the kind of leader I wanted her on all the initiatives, she greatly deserves the benefits of the project” (Interview HM E10). |

|

| ||

| Coach experience and skills | “We selected our coach very well, she had all these components, a lot of experience, knew the environment, not just Montfort, but she was really experienced for everything that exists in the community that often a bedside nurse did not have” (Interview HM E08). | |

| “We need someone who understands his role, where it starts and where it ends, and who knows my role too, by what it is sure that our two roles complement each other” (Interview HM E03). | ||

|

| ||

| Teams’ openness to change | “There was an openness to change, a beautiful communication takes place in Montfort and an alignment with the hospital’s mission and the desire to become an elder friendly hospital, so the project becomes a priority for all and energies are put where the priorities are” (Interview HM E10). | |

|

| ||

| Collaboration between professionals, and synergy between teams and decision levels | “The coach was able to connect the nurses, she gave them feedback about the project, it was very appreciated. We reviewed the job description and revised it with the director, because she was the administrative leader. We did with the director all the links with human resources, the posting of the position, the interviews…. etc.” (Interview HM E08). | |

|

| ||

| Commitment, support, and responsiveness of decision makers | “It was the team that did the work, but I [Director] was there all the time, anytime, when they needed it, that’s one of my priorities. So, she [project manager] could knock on my door at any time to tell me about this project. I attended meetings and followed the team step by step. They had my support” (Interview HM E07). | |

| “If things were going well, I didn’t have to contact the Director, if I needed help with something, really with a pitfall, I’d meet her so she could give me a hand and then if necessary to climb it to a higher level” (Interview HM E10). | ||

|

| ||

| Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement and Mount Sinai Hospital’s support | “Honestly, for us, the experts at the foundation [CFHI], the experts in Toronto [Mount Sinai Hospital], are resources that we do not often have access to. So, to have access to this expertise, yes, definitely helping. [] …the quality of these people [CHIF-CFN, Mount Sinai Hospital’s team] was exceptional “ (Interview HM E09). | |

| “The project demonstrated what it means a national collaborative and access to external expertise, networking, lessons learned…. [] For project management, there was everything when you want it to work, it was like a book. I still refer to it often” (Interview HM E10). | ||

|

| ||

| Theoretical approach | Evidence-based intervention planning, design and implementation | “Three guidelines from the registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario have been matched with other guidelines: Chronic Disease Management and Facilitating Client Centered Learning. These guidelines were put together to develop our process, and we were given permission to use Coleman’s assessment tool, the Care Transition Measure” (Interview HM E07). |

| “One of the new tools we’ve discovered, and [that] we [are] still using today, is the NHS Sustainability Tool. I didn’t know this scale “ (Interview HM E08). | ||

| “Three best practice guidelines on care transitions were matched, and then some Coleman assessment tools such as the Care Transition Measure were used. We were allowed to use and implement this tool” (Interview HM E10). | ||

| “We used it [NHS-Sustainability Model] a lot in change management, to say: here’s where we are, here’s where we should work” (Interview HM E08). | ||

|

| ||

| Strategies | Rigorous project planning and project joint co-construction approach | “We reviewed the job description and revised it with the director, because she was the administrative leader. We did with the director all the links with human resources, the posting of the position, the interviews. Then, once we hired the coach, I met her for 45 minutes every day she spent at work, so we could develop the project and the tools. (Interview HM E09). |

|

| ||

| Choosing the Clinical Care Unit and Locating Patients on the Unit | “There was a dashboard in the common room of the unit with a list of all patients and then the administrative assistant had imagined putting a special little acronym, a playing card, an “ace” of spades, which was put alongside the names of patients identified for the ACE project.” (Interview HM E08). | |

|

| ||

| Involvement of professional practice in project development and management | “The project required a discussion with professional practice team that ensured that best practices in transition were respected. So, it was carried out in collaboration with them... (Interview HM E01). | |

|

| ||

| Participatory and inclusive approach | “In our meetings with all stakeholders, we offered ideas, we asked for their opinions, and then there were discussions. Most of the time they accepted our suggestions, but we really wanted to be able to have their buy-in for the implementation” (Interview MM E10). | |

|

| ||

| Continuous quality improvement approach | “… the clinical information department, so to see everything that’s related to data collection, just tracking the data to give team feedback. So, for example, tracking the readmission rate, that’s part of their job” (Interview HM E05). | |

|

| ||

| Concern about sustainability early in the implementation process | “Sustainability, I think it was well planned, but we didn’t have enough resources to put it in place as it should be “ (Interview HM E10). | |

| “One of the new tools we’ve discovered, and [that] we [are] still using today, is the NHS Sustainability Tool. I didn’t know this scale “ (Interview HM E08). | ||

|

| ||

| Continuous internal and external communication | “We had meetings and at the end of each one it was the project manager who made a kind of summary that she emailed to everyone” (Interview HM E4). | |

| “I think we have to have good communication with the coach. Everyone has a role, and we must not pile on our feet” (Interview HM E03). | ||

|

| ||

| Knowledge translation | SharePoint use | “SharePoint really helped us a lot. It makes information more accessible to everyone. We were able to view the documents at the same time. [...] It’s much more effective as a tool than e-mail, than sending attachments that get lost and you never know the latest version” (Interview HM E10). |

| “Let’s say we wanted to review a document, we’d say, “OK, the document is on SharePoint, look at and revise.” So, everyone could put their comments in there” (Interview HM E02) | ||

| “Right now, every time someone talks to me about the transition, I tell them not to reinvent the wheel, we have everything, it’s all on our SharePoint.” (Interview HM E08). | ||

|

| ||

| Barriers | ||

|

| ||

| Actors and resources | Change and departure of the staff and stakeholders | “During the project, there were changes of players... [], it’s often a bit of a start and slows down” (Interview HM E08). |

| “Another thing that didn’t help us was that there are a lot of people who have changed chairs, more than at any other time. [] it’s a new project and almost half of the players have changed chairs. [] and it looks like the information doesn’t really know how to translate well from one player to another” (Interview HM E10). | ||

|

| ||

| Coach presence on part-time basis | “We got the money for only half a [position] and the nurse wasn’t there seven days a week to see the patients” (Interview HM E06). | |

| “The post-discharge follow-up wasn’t easy because I was there just two days a week, when our goal was to call patients at about 72 hours. [], it could take three, four to five days, or if I couldn’t reach them, it could be a little longer” (Interview HM E02). | ||

| “The coach wasn’t there […] five days a week, it was a concern. One day she’s here, [another] day she’s not... [] we have to make sure that we have some reliability, […], for doctors, clinical teams, it was difficult to know whether we have the service or not” (Interview HM E06). | ||

| “When you don’t have something at least five days a week, it becomes difficult to [implement] and then evaluate and know if it works or not” (Interview HM E08). | ||

| “If you can’t have full time, it would have been nice if she was there every morning or afternoon. Because the hospital never stops, so you can’t really say that there are days of the week when it’s good to be there” (Interview HM E04). | ||

|

| ||