Abstract

N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) has shown promise as a putative neurotherapeutic for traumatic brain injury (TBI). Yet, many such promising compounds have limited ability to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), achieve therapeutic concentrations in brain, demonstrate target engagement, among other things, that have hampered successful translation. A pharmacologic strategy for overcoming poor BBB permeability and/or efflux out of the brain of organic acid-based, small molecule therapeutics such as NAC is co-administration with a targeted or nonselective membrane transporter inhibitor. Probenecid is a classic ATP-binding cassette and solute carrier inhibitor that blocks transport of organic acids, including NAC. Accordingly, combination therapy using probenecid as an adjuvant with NAC represents a logical neurotherapeutic strategy for treatment of TBI (and other CNS diseases). We have completed a proof-of-concept pilot study using this drug combination in children with severe TBI—the Pro-NAC Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01322009). In this review, we will discuss the background and rationale for combination therapy with probenecid and NAC in TBI, providing justification for further clinical investigation.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporters, Blood–brain barrier, Head injury, Organic anion transporters, Solute carriers

Introduction

N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) is a synthetic form of the amino acid cysteine and pharmacologic precursor to the vital intracellular antioxidant glutathione (GSH). It was initially used clinically as a mucolytic agent in patients with cystic fibrosis [1] and is most notorious for its use as an antidote for acetaminophen/paracetamol poisoning [2]. NAC emerged as a potential therapy for traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the 1990s in multiple experimental models (reviewed in: Bhatti et al. [3]) and has been evaluated in clinical trials in multiple neurological diseases including TBI [4]. NAC is highly hydrophilic and has recently been identified as a transporter substrate and, as such, has very limited ability to cross the intact blood–brain barrier (BBB) hampering successful translation [5]. A pharmacologic strategy for overcoming limited NAC BBB permeability and/or active efflux out of the brain includes co-administration with the membrane transporter inhibitor probenecid, a classic and promiscuous ATP-binding cassette (ABC), and solute carrier (SLC) inhibitor that blocks transport of organic acids [6]. Based on this premise, we completed a proof-of-concept pilot study using probenecid and NAC in combination in children with severe TBI—the Pro-NAC Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01322009) [7]. In this review, we will discuss the biological basis and preclinical and clinical evidence for NAC as a neurotherapeutic in TBI, the biologic basis for combination therapy with probenecid, and provide a rationale for further investigation of probenecid and NAC combination therapy for TBI.

N-Acetylcysteine

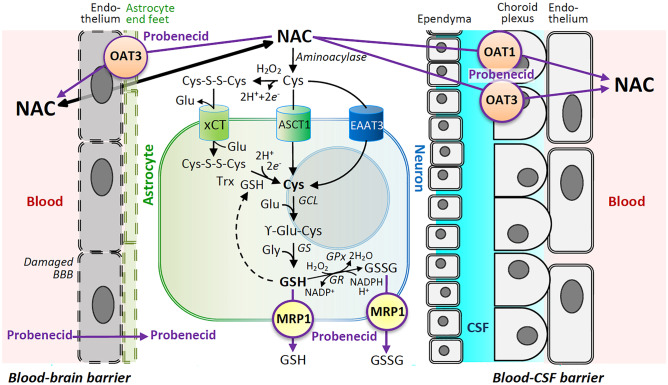

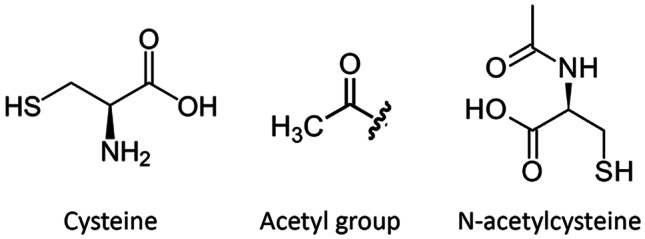

NAC has direct antioxidant effects via its thiol group (Fig. 1) and can react with and scavenge a number of radicals including ·OH, ·NO2, CO3·−, and thiyl radicals [5]. However, the major pharmacologic effect of NAC is thought to be related to its capacity to increase the cysteine pool necessary for replenishment of the vital intracellular antioxidant GSH (Fig. 2) [5, 8]. NAC is highly hydrophilic (logD − 5.4) and therefore has limited capacity to passively cross plasma membranes [5]. NAC can be deacetylated to cysteine by aminoacylase [9] which can then be directly imported into cells by the SLC excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3; SLC1A1) and the alanine, serine, and cysteine transporter 1 (ASCT1; SLC1A4). Cysteine can also be oxidized to the disulfide dimer cystine (Cys-S–S-Cys) and imported via the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc- (xCT; SLC7A11). EAAT3 is enriched in neurons, whereas ASCT1 and xCT are enriched in astrocytes [10]. Intracellular cystine can then be reduced to form two molecules of cysteine, a reaction that can be facilitated by GSH or thioredoxin [11]. GSH can then be synthesized from cysteine, glutamate, and glycine in a two-step process involving glutamate cysteine ligase and GSH synthetase (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of cysteine, an acetyl group, and N-acetylcysteine

Fig. 2.

Simplified schematic highlighting the biochemical effects of probenecid and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) combination therapy in traumatic brain injury (TBI). After TBI, NAC can more readily penetrate the disrupted blood–brain barrier (BBB) and then function as a cysteine (Cys) donor for formation of glutathione (GSH). Cys can be transported into cells via excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3) enriched in neurons or the alanine, serine, and cysteine transporter 1 (ASCT1) enriched in astrocytes. Cysteine can also be oxidized to the disulfide dimer cystine (Cys-S–S-Cys) and imported via the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc- (xCT) enriched in astrocytes and then reduced back to Cys via GSH or thioredoxin (Trx). GSH can then be synthesized from Cys, glutamate (Glu), and glycine (Gly) via a two-step process by Glu-Cys ligase (GCL) and GSH synthetase (GS). GSH can be oxidized by GSH peroxidase (GPx) to GSSG and recycled back to GSH by GSH reductase (GR). NAC can be transported out of the CNS via solute carriers (SLCs) including organic anion transporter 1 (OAT1) and OAT3 on the BBB and blood-CSF barriers. Multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP1), an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, exports GSH and GSSG as well as other glutathionylated substances and xenobiotics across plasma membranes. Probenecid inhibits OAT1, OAT3, and MRP1 and likely many other SLCs and ABC transporters to reduce the efflux of organic anions and peptides including GSH. Synergistic effects may be achieved by delivering the Cys donor NAC in combination with probenecid to replete/maintain endogenous stores of GSH and increase brain exposure to NAC by inhibiting its efflux

Preclinical Studies of N-Acetylcysteine for Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury

NAC emerged as a potential therapy for TBI in the 1990s with a report using an experimental model of fluid percussion injury (FPI) in cats showing that NAC treatment improved cerebrovascular responsivity [12]. Since then, NAC has shown promise in multiple preclinical studies using multiple experimental models [3, 13]. Several of these studies support the premise that NAC’s effects are linked to GSH or GSH-dependent pathways, i.e., target engagement. Treatment with NAC has been shown to preserve brain GSH levels and/or GSH peroxidase (GPx) activity after closed head injury (CHI) and preserve mitochondrial GSH levels after controlled cortical impact (CCI) in rats compared with vehicle [14–16]. Importantly, NAC has also been shown to be neuroprotective after experimental TBI, improving functional and histologic outcomes. Rats treated with NAC (50 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.)) 30 min after FPI and then daily for an additional 3 days showed improved performance in the Morris water maze on days 10–14 compared with vehicle [17]. In this same report, mice treated with a single 100 mg/kg dose of NAC i.p. 1 h after CHI showed improved performance in novel object recognition and Y-maze tasks at 7 and 30 days compared with vehicle [17]. Furthermore, NAC administered 5 min after FPI in rats reduced neuronal death and brain tissue loss compared with vehicle [18, 19]. NAC has also been used in combination with other potential neurotherapeutics including minocycline [20–26], topiramate [17], selenium [27], sulforaphane [28], levetiracetam, and gabapentin [29] and 2,4-disulfonyl alpha-phenyl tertiary butyl nitrone [30] with suggestion of synergy.

The above studies suggest bioavailability of systemically administered NAC in therapeutic concentrations after experimental TBI, likely facilitated by a disrupted BBB after trauma. Alternatively, NAC could be converted to cysteine by aminoacylases in the kidney or other tissues [31] with cysteine actively transported across the BBB [32]. Cysteine analogs with modifications designed to facilitate passive transfer across the intact BBB have been synthesized and include N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) and γ-glutamylcysteine ethyl ester (GCEE). Pandya et al. administered NACA as a bolus dose i.p. (150 mg/kg) followed by infusion pump delivery (18.5 mg/kg/h) 30 min after CCI in rats and reported cortical tissue sparing and improved Morris water maze performance vs. NAC or vehicle treatment [33]. Treatment with NACA has also been shown to reduce oxidative stress and apoptotic neurodegeneration after weight drop injury in mice [34] and reduce BBB damage and intracranial pressure (ICP) after blast injury in rats [35, 36]. Lai et al. reported that a single 150 mg/kg i.p. dose of GCEE administered 10 min after CCI in mice reduced lesion volume and improved Morris water maze performance vs. vehicle treatment [37].

N-Acetylcysteine Monotherapy for Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans

NAC has established clinical utility as the antidote for acetaminophen/paracetamol-induced hepatic necrosis [2]. NAC has also been evaluated in clinical trials targeting neurological diseases, including autism, depression, schizophrenia, epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease, and TBI (reviewed in Deepmala et al. [4]). To our knowledge, NAC as monotherapy for TBI has been reported in two clinical studies, both for treatment of mild TBI.

Hoffer et al. reported a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for symptomatic US service members exposed to significant ordnance blast and meeting criteria for mild TBI at a field forward military hospital [38]. Symptoms of mild TBI included dizziness, hearing loss, headache, memory loss, sleep disturbances, and neurocognitive dysfunction. Eighty-one patients, 41 in the NAC group and 40 in the control group, ranging in age from 18 to 43 years were enrolled. The intervention consisted of a NAC loading dose of 4 g administered orally (p.o.), followed by 2 g p.o. twice daily on days 2–5 and 1.5 g p.o. twice daily on days 6–7. Patients in the NAC treatment group were more likely to have their symptoms resolve by day 7 compared with patients in the placebo group.

A recent prospective, quasi-randomized controlled trial evaluated the effect of NAC and standard care vs. standard care alone in elderly patients (≥ 60 years old) who suffered mild TBI mostly from ground level falls [39]. Patients with reported head trauma evaluated in the emergency department within 3 h were eligible. Sixty-five patients, 34 in the NAC group and 31 in the control group, with an average age of 75 years and median Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15 were enrolled. The intervention consisted of a NAC loading dose of 4 g p.o. followed by 2 g p.o. twice daily on days 2–4 and 1.5 g p.o. twice daily on days 5–7. If the patients were discharged before day 7, the intervention was stopped. Patients in the NAC group had significantly lower Rivermead Postconcussion Symptoms Questionnaire scores assessed on days 7 and 30 vs. standard care alone.

These clinical studies have obvious limitations including small sample sizes, self-reported outcomes, and either no attempt at blinding [39] or potential challenges in double-blinding [38] given the unpleasant sulfur taste of NAC taken orally. Also notable is the relatively large dose of NAC used in these studies, possibly required because of NAC’s limited capacity to passively cross the BBB. It is unclear what degree of BBB disruption occurred in these patients and for what duration of the 7-day treatment period, particularly in patients whose mechanism of injury was a ground level fall. Nonetheless, no side effects of NAC were reported in either study or outcomes significantly favored NAC treatment in both, supporting a rationale for augmenting brain bioavailability of NAC as a neurotherapeutic strategy for mild TBI and possibly more severe TBI as well.

Probenecid

Probenecid (previously Benemid®) was developed due to shortages of penicillin needed to treat postsurgical infections in battlefield wounds in soldiers during the Second World War [40]. Co-administration of probenecid increases plasma penicillin concentration by inhibiting elimination via the SLC organic anion transporters 1 and 3 (OAT1/SLC22A6 and OAT3/SLC22A8) in the kidney [41]. Probenecid is nonselective and inhibits multiple other SLCs and ABC membrane transporters in the kidney, gut, brain, and several other tissues [42]. Probenecid is lipid soluble, and in and of itself has emerged as a putative neurotherapeutic [6]. In the brain, probenecid has been shown to inhibit OAT1- and 3-mediated transport of kynurenic acid, which has neuromodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects [43]. Probenecid has also been shown to prevent intracellular depletion of GSH via inhibition of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1)–mediated export of GSH, oxidized glutathione (GSSG), and glutathionylated substrates and xenobiotics [44]. GSH and GSSG recycling occurs via GPx and glutathione reductase, a process integral to regulation of ferroptosis, emerging as a contributor to neuronal death after TBI [45] and hemorrhagic stroke in mice [46]. In addition to effects related to SLCs and ABC transporters, probenecid may also have other neuroprotective effects, including inhibition of pannexin 1 channels and pyroptosis [47], and as a transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 agonist [6].

Probenecid as an Adjuvant for N-Acetylcysteine

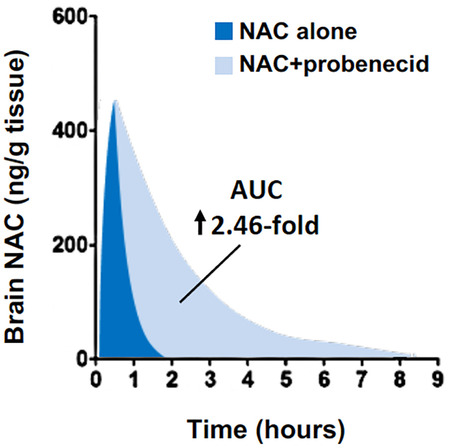

Given that NAC is a synthetic form of cysteine and renal excretion of cysteine-based mercapturic acids is inhibited by probenecid [48], we posited that NAC would also be a probenecid-inhibitable transporter substrate. 14C-Acetyl-L-cysteine uptake studies with human kidney cell lines stably overexpressing OAT1 and OAT3 confirmed that NAC exhibits time- and concentration-dependent uptake vs. mock-transfected cells and that uptake is inhibitable by probenecid [49]. Furthermore, in naïve Sprague–Dawley rats, co-administration of probenecid increased NAC concentration in both the brain and plasma by 2.41- and 1.65-fold, respectively. Despite NAC’s relative inability to cross the intact BBB, brain NAC concentrations were over 400 ng/g brain tissue measured 30 min after a bolus dose of 163 mg/kg intravenously (i.v.). These levels quickly dropped to below 80 ng/g brain tissue by 1 h and were undetectable after 4 h. Co-administration with probenecid not only increased the total NAC brain exposure, but it also extended the duration of detection in the normal brain to 8 h after a single bolus dose (Fig. 3). Taken together, these findings suggest that NAC can cross the intact BBB but then is rapidly eliminated via OAT1 and OAT3 (and perhaps other probenecid-inhibitable membrane transporters). This study provided valuable insight into how NAC bidirectionally crosses biological membranes and in particular the intact BBB.

Fig. 3.

Simplified schematic demonstrating post-bolus brain NAC exposure with or without probenecid in naïve rats. For details, please see Hagos et al. [49]

Figure 2 highlights potential synergism using combination therapy with probenecid and NAC. Probenecid can maintain brain exposure of NAC by preventing efflux transport at the BBB and blood-CSF barriers (BCSFB) by OAT1 and OAT3. Probenecid also increases plasma concentrations of NAC by inhibiting urinary excretion in the kidney by the same transporters; indeed, plasma concentrations are 1.65-fold higher when probenecid is co-administered with NAC [49]. In addition, probenecid can maintain intracellular GSH stores by delaying export of GSH and GSSG by MRP1. In primary cortical neurons in vitro, the combination of probenecid and NAC synergistically increases intracellular GSH and reduces neuronal death after traumatic stretch injury vs. probenecid or NAC alone [50]. It is unknown whether probenecid inhibits cysteine or cystine transport via SLCs EAAT3 (SLC1A1), ASCT1 (SLC1A4), or xCT (SLC7A11). Interestingly, genetic inhibition of EAAT3 decreases cysteine uptake and exacerbates oxidative stress and neuronal death after TBI in mice [51].

Pro-NAC Trial: Combination Therapy with N-Acetylcysteine and Probenecid After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Children

Given independent neurotherapeutic effects of probenecid [6] and NAC [3], potential synergism of combination therapy [50], favorable safety profiles and FDA approval of both drugs, and the fact that no targeted neurotherapeutics currently exist for treatment of TBI in humans, we embarked on a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase I study of the combination use of probenecid and NAC in children with severe TBI (Pro-NAC Trial; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01322009) [7].

Children ages 2–18 years with severe TBI defined as a GCS ≤ 8 and requiring an externalized ventricular drain for measurement of ICP and obtaining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were eligible. Patients had isolated TBI and not polytrauma with the exception of orthopedic injuries. Fourteen patients were enrolled after obtaining informed consent and were randomized to treatment or placebo. Patient demographics, surgical interventions, adverse events, and complications are shown in Table 1. Seven patients received probenecid (25 mg/kg load, then 10 mg/kg/dose q6h × 11 doses) and NAC (140 mg/kg load, then 70 mg/kg/dose q4h × 17 doses), and 7 received placebos via naso/orogastric tube. Serum and CSF samples were collected at baseline, 1-h post-loading doses, and then daily for 4 more days and drug concentrations were measured via ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). At 24- to 72-h post-bolus, NAC concentrations ranged from 17.0 ± 2.2 to 16.8 ± 3.3 μg/mL in serum and 269.3 ± 113.0 to 467.9 ± 262.7 ng/mL in CSF. To our knowledge, one other study has reported CSF NAC concentrations in humans. Twelve adult patients with Parkinson’s disease received oral doses of NAC ranging from 7 to 70 mg/kg twice daily for 2 days [52]. Peak CSF NAC concentrations 90 min after the final dose were approximately fourfold higher than what we observed at steady state in children. However, in the study of adults with Parkinson’s disease, NAC peak levels were measured, and given that NAC elimination is two-compartmental, CSF NAC levels between these adults and pediatric studies are not readily comparable. Importantly, no adverse effects or undesirable physiological derangements, including raised ICP, related to administration of probenecid and NAC were observed in this study in children with severe TBI [7]. CNS-related and other adverse events/complications observed in the study population are provided in Table 1. Of note, anaphylaxis, refractory intracranial hypertension, or status epilepticus, reported in cases of NAC overdoses related to prescribing errors [53], attributable to probenecid and NAC treatment was not observed.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, mortality, surgical interventions, adverse events, and complications in the intention to treat population (data are n (%) unless otherwise stated)

| Placebo (n = 7) | Probenecid + NAC (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient demographics | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 9.7 (5.7) | 8.6 (4.9) |

| Male sex | 4 (57%) | 6 (86%) |

| White race | 7 (100%) | 6 (86%) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score, median (IQR) | 6 (3) | 6 (2) |

| Eye, median (IQR) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Verbal, median (IQR) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Motor, median (IQR) | 4 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| Passenger in motor vehicle collision | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) |

| Pedestrian struck by motor vehicle | 0 | 1 (14%) |

| All-terrain vehicle accident | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Fall | 0 | 1 (14%) |

| Other recreational activity | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Gunshot wound | 1 (14%) | 2 (29%) |

| Suspected abusive head trauma | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) |

| Mortality | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Surgical interventions | ||

| External ventricular drain placement | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Evacuation of hematoma/lesion | 1 (14%) | 3 (43%) |

| Decompressive craniectomy | ||

| Unilateral | 1 (14%) | 3 (43%) |

| Bilateral | 2 (29%) | 0 |

| CNS-related adverse event/complication | ||

| Refractory intracranial hypertension | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Ruptured aneurysm | 0 | 1 (14%) |

| Hydrocephalus | 0 | 1 (14%) |

| Vocal cord paralysis | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Diabetes insipidus | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Other adverse events/complication | ||

| Acute renal failure | 2 (29%) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) |

| Tracheitis | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) |

| Rash | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Refractory hypotension | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 (14%) | 0 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 1 (14%) | 3 (43%) |

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

Pharmacometabolomic Analysis of the Pro-NAC Trial

Pharmacometabolomics is a powerful tool that uses metabolic signatures to characterize responses to drug treatment(s). Pharmacometabolomics as classically defined predicts the biologic outcome of a drug or xenobiotic based on mathematical modeling of “preintervention metabolite signatures [54]” but can also capitalize on comparisons between treated and untreated populations. In a follow-up study, our group utilized CSF samples from the Pro-NAC trial to perform a pharmacometabolomic comparison of pediatric TBI patients vs. age-matched control subjects (n = 5) and placebo-treated TBI vs. probenecid + NAC-treated patients [55]. Remnant CSF was only available for five placebo- and seven probenecid + NAC-treated patients obtained 24 h after placebo or drug treatment in the Pro-NAC trial. A two-compartment principal component analysis demonstrated clustering between groups with distinct metabolomic signatures. A combination of metabolomics and pathway/network analyses identified several known mechanistic pathways altered in TBI patients vs. control subjects, as well as several novel metabolomic pathways that could play a role after TBI.

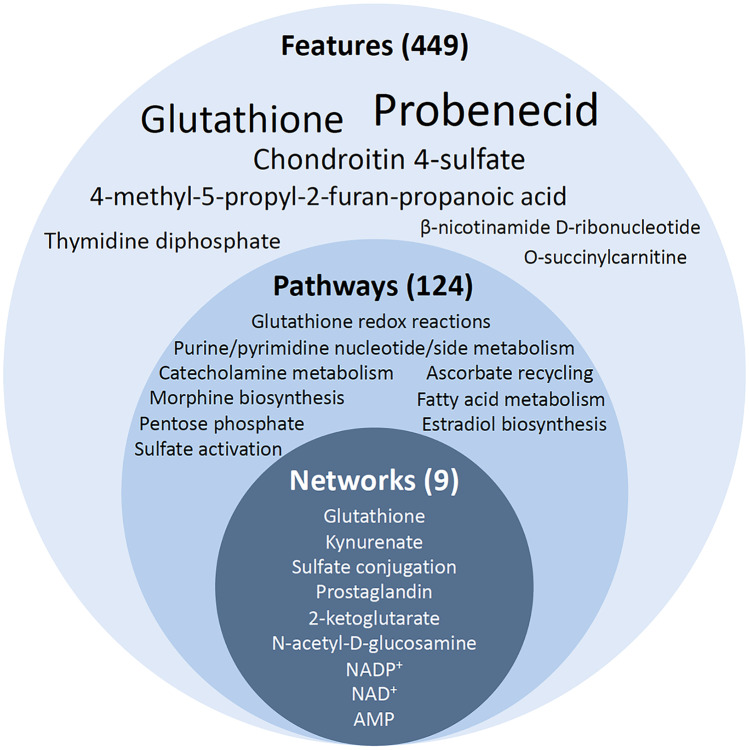

When comparing the placebo- and probenecid + NAC-treated groups, 449 features were identified that were significantly increased or decreased by probenecid + NAC treatment after TBI (Fig. 4). Probenecid was the most prominently altered feature (7731-fold increase) providing internal validity of the UPLC-MS/MS approach. This was followed by GSH (665-fold increase) supporting therapeutic target engagement. Of 124 pathways enriched in the CSF of probenecid + NAC- vs. placebo-treated TBI patients, seven glutathione-centered pathways were identified involving GSH redox, synthesis, and detoxification reactions, as well as other pathways involving GSH including ascorbate recycling. Of nine networks enriched in the CSF of probenecid + NAC- vs. placebo-treated TBI patients, two glutathione-centered networks were identified involving GSH redox and detoxification reactions. Other pathways/networks consisting of components that are known substrates of probenecid-inhibitable membrane transporters such as prostaglandins, kynurenate, and urate were also enriched, providing additional mechanistic validation. The pharmacometabolomic approach provided verification of target engagement when using combined treatment with probenecid and NAC in children with severe TBI. Furthermore, the approach provided valuable understanding of the range of substrates and functions of probenecid inhibitable SLC and ABC transporters and both desirable and undesirable pharmacologic and/or metabolic consequences of probenecid treatment after TBI.

Fig. 4.

Summary of pharmacometabolomic features (449, font size represents relative increase vs. placebo), pathways (124), and networks (9) altered by probenecid and NAC combination therapy after TBI. For details, please see Hagos et al. [55]

Conclusion

Both preclinical and clinical studies directly support the use of NAC as a neurotherapeutic for TBI, with a few preclinical studies also suggesting that probenecid may have efficacy. Combination therapy with probenecid and NAC has a strong biological basis, and target engagement has been demonstrated using a pharmacometabolomic approach in children with severe TBI. Given potential neurotherapeutic effects of NAC alone, potential synergism of combination therapy with probenecid, favorable safety profiles and FDA approval of both drugs, and the fact that no targeted neurotherapeutics currently exist for treatment of TBI in humans, further investigation using the combination of probenecid and NAC appears warranted. Moreover, strategies using other membrane transport inhibitors with corresponding drug substrates to improve therapeutic brain exposure should also be pursued.

Acknowledgements

The Pro-NAC trial and pharmacometabolomic study were supported by R01 NS069247 (RSBC, PEE, PMK, MJB). PMK is supported by the Ake Grenvik Endowment.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Imperato PJ, Palanca LM, Fernandez JP. Successful treatment with the mucolytic agent acetylcysteine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1964;90:111–115. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1964.90.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Efficacy of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Analysis of the national multicenter study (1976 to 1985). N Engl J Med. 1988;319(24):1557–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bhatti J, Nascimento B, Akhtar U, Rhind SG, Tien H, Nathens A, et al. Systematic review of human and animal studies examining the efficacy and safety of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) in traumatic brain injury: impact on neurofunctional outcome and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Front Neurol. 2017;8:744. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deepmala, Slattery J, Kumar N, Delhey L, Berk M, Dean O, et al. Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:294–321. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Samuni Y, Goldstein S, Dean OM, Berk M. The chemistry and biological activities of N-acetylcysteine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(8):4117–4129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colin-Gonzalez AL, Santamaria A. Probenecid: an emerging tool for neuroprotection. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(7):1050–1065. doi: 10.2174/18715273113129990090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark RSB, Empey PE, Bayir H, Rosario BL, Poloyac SM, Kochanek PM, et al. Phase I randomized clinical trial of N-acetylcysteine in combination with an adjuvant probenecid for treatment of severe traumatic brain injury in children. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauterburg BH, Corcoran GB, Mitchell JR. Mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine in the protection against the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen in rats in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1983;71(4):980–991. doi: 10.1172/JCI110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uttamsingh V, Keller DA, Anders MW. Acylase I-catalyzed deacetylation of N-acetyl-L-cysteine and S-alkyl-N-acetyl-L-cysteines. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11(7):800–809. doi: 10.1021/tx980018b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul BD, Sbodio JI, Snyder SH. Cysteine metabolism in neuronal redox homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39(5):513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBean GJ. Cysteine, glutathione, and thiol redox balance in astrocytes. Antioxidants (Basel). 2017;6(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ellis EF, Dodson LY, Police RJ. Restoration of cerebrovascular responsiveness to hyperventilation by the oxygen radical scavenger n-acetylcysteine following experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(5):774–779. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.5.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hameed MQ, Hodgson N, Lee HHC, Pascual-Leone A, MacMullin PC, Jannati A, et al. N-acetylcysteine treatment mitigates loss of cortical parvalbumin-positive interneuron and perineuronal net integrity resulting from persistent oxidative stress in a rat TBI model. Cereb Cortex. 2023;33(7):4070–4084. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicdonmez T, Kanter M, Tiryaki M, Parsak T, Cobanoglu S. Neuroprotective effects of N-acetylcysteine on experimental closed head trauma in rats. Neurochem Res. 2006;31(4):473–481. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senol N, Naziroglu M, Yuruker V. N-acetylcysteine and selenium modulate oxidative stress, antioxidant vitamin and cytokine values in traumatic brain injury-induced rats. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(4):685–692. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong Y, Peterson PL, Lee CP. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on mitochondrial function following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1999;16(11):1067–1082. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eakin K, Baratz-Goldstein R, Pick CG, Zindel O, Balaban CD, Hoffer ME, et al. Efficacy of N-acetyl cysteine in traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e90617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi JH, Hazell AS. N-acetylcysteine attenuates early induction of heme oxygenase-1 following traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2005;1033(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yi JH, Hoover R, McIntosh TK, Hazell AS. Early, transient increase in complexin I and complexin II in the cerebral cortex following traumatic brain injury is attenuated by N-acetylcysteine. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(1):86–96. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel Baki SG, Schwab B, Haber M, Fenton AA, Bergold PJ. Minocycline synergizes with N-acetylcysteine and improves cognition and memory following traumatic brain injury in rats. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(8):e12490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haber M, Abdel Baki SG, Grin’kina NM, Irizarry R, Ershova A, Orsi S, et al. Minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine synergize to modulate inflammation and prevent cognitive and memory deficits in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;249:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Haber M, James J, Kim J, Sangobowale M, Irizarry R, Ho J, et al. Minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine induces remyelination, synergistically protects oligodendrocytes and modifies neuroinflammation in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(8):1312–1326. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawless S, Bergold PJ. Better together? Treating traumatic brain injury with minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17(12):2589–2592. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.336136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangobowale M, Nikulina E, Bergold PJ. Minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine protect oligodendrocytes when first dosed 12 hours after closed head injury in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2018;682:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangobowale MA, Grin’kina NM, Whitney K, Nikulina E, St Laurent-Ariot K, Ho JS, et al. Minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine reduce behavioral deficits and improve histology with a clinically useful time window. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(7):907–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Whitney K, Nikulina E, Rahman SN, Alexis A, Bergold PJ. Delayed dosing of minocycline plus N-acetylcysteine reduces neurodegeneration in distal brain regions and restores spatial memory after experimental traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2021;345:113816. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naziroglu M, Senol N, Ghazizadeh V, Yuruker V. Neuroprotection induced by N-acetylcysteine and selenium against traumatic brain injury-induced apoptosis and calcium entry in hippocampus of rat. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2014;34(6):895–903. doi: 10.1007/s10571-014-0069-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyyriainen J, Kajevu N, Banuelos I, Lara L, Lipponen A, Balosso S, et al. Targeting oxidative stress with antioxidant duotherapy after experimental traumatic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Efendioglu M, Basaran R, Akca M, Ceman D, Demirtas C, Yildirim M. Combination therapy of gabapentin and N-acetylcysteine against posttraumatic epilepsy in rats. Neurochem Res. 2020;45(8):1802–1812. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du X, West MB, Cai Q, Cheng W, Ewert DL, Li W, et al. Antioxidants reduce neurodegeneration and accumulation of pathologic tau proteins in the auditory system after blast exposure. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;108:627–643. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anders MW, Dekant W. Aminoacylases. Adv Pharmacol. 1994;27:431–448. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)61042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wade LA, Brady HM. Cysteine and cystine transport at the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 1981;37(3):730–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb12548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandya JD, Readnower RD, Patel SP, Yonutas HM, Pauly JR, Goldstein GA, et al. N-acetylcysteine amide confers neuroprotection, improves bioenergetics and behavioral outcome following TBI. Exp Neurol. 2014;257:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Wang HD, Zhou XM, Fang J, Zhu L, Ding K. N-acetylcysteine amide provides neuroprotection via Nrf2-ARE pathway in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:4117–4127. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S179227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawoos U, Abutarboush R, Zarriello S, Qadri A, Ahlers ST, McCarron RM, et al. N-acetylcysteine amide ameliorates blast-induced changes in blood-brain barrier integrity in rats. Front Neurol. 2019;10:650. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawoos U, McCarron RM, Chavko M. Protective effect of N-acetylcysteine amide on blast-induced increase in intracranial pressure in rats. Front Neurol. 2017;8:219. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai Y, Hickey RW, Chen Y, Bayir H, Sullivan ML, Chu CT, et al. Autophagy is increased after traumatic brain injury in mice and is partially inhibited by the antioxidant gamma-glutamylcysteinyl ethyl ester. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(3):540–550. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffer ME, Balaban C, Slade MD, Tsao JW, Hoffer B. Amelioration of acute sequelae of blast induced mild traumatic brain injury by N-acetyl cysteine: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McPherson RA, Mangram AJ, Barletta JF, Dzandu JK. N -acetylcysteine is associated with reduction of postconcussive symptoms in elderly patients: a pilot study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(5):644–649. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burnell JM, Kirby WM. Effectiveness of a new compound, benemid, in elevating serum penicillin concentrations. J Clin Invest. 1951;30(7):697–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI102482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nigam SK, Bush KT, Martovetsky G, Ahn SY, Liu HC, Richard E, et al. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: a systems biology perspective. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(1):83–123. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagos FT, Adams SM, Poloyac SM, Kochanek PM, Horvat CM, Clark RSB, et al. Membrane transporters in traumatic brain injury: pathological, pharmacotherapeutic, and developmental implications. Exp Neurol. 2019;317:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wirthgen E, Hoeflich A, Rebl A, Gunther J. Kynurenic acid: the Janus-faced role of an immunomodulatory tryptophan metabolite and its link to pathological conditions. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1957. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammond CL, Marchan R, Krance SM, Ballatori N. Glutathione export during apoptosis requires functional multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(19):14337–14347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenny EM, Fidan E, Yang Q, Anthonymuthu TS, New LA, Meyer EA, et al. Ferroptosis contributes to neuronal death and functional outcome after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(3):410–418. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karuppagounder SS, Alin L, Chen Y, Brand D, Bourassa MW, Dietrich K, et al. N-acetylcysteine targets 5 lipoxygenase-derived, toxic lipids and can synergize with prostaglandin E(2) to inhibit ferroptosis and improve outcomes following hemorrhagic stroke in mice. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(6):854–872. doi: 10.1002/ana.25356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adamczak SE, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Dale G, Brand FJ, 3rd, Nonner D, Bullock MR, et al. Pyroptotic neuronal cell death mediated by the AIM2 inflammasome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(4):621–629. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inoue M, Okajima K, Morino Y. Renal transtubular transport of mercapturic acid in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;641(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90575-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagos FT, Daood MJ, Ocque JA, Nolin TD, Bayir H, Poloyac SM, et al. Probenecid, an organic anion transporter 1 and 3 inhibitor, increases plasma and brain exposure of N-acetylcysteine. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems. 2017;47(4):346–353. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2016.1187777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du L, Empey PE, Ji J, Chao H, Kochanek PM, Bayir H, et al. Probenecid and N-acetylcysteine prevent loss of intracellular glutathione and inhibit neuronal death after mechanical stretch injury in vitro. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(20):1913–1917. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi BY, Kim IY, Kim JH, Lee BE, Lee SH, Kho AR, et al. Decreased cysteine uptake by EAAC1 gene deletion exacerbates neuronal oxidative stress and neuronal death after traumatic brain injury. Amino Acids. 2016;48(7):1619–1629. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katz M, Won SJ, Park Y, Orr A, Jones DP, Swanson RA, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of N-acetylcysteine after oral administration in Parkinson’ s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(5):500–503. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spence EEM, Shwetz S, Ryan L, Anton N, Joffe AR. Non-intentional N-acetylcysteine overdose associated with cerebral edema and brain death. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2023;17(1):96–103. doi: 10.1159/000529169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clayton TA, Lindon JC, Cloarec O, Antti H, Charuel C, Hanton G, et al. Pharmaco-metabonomic phenotyping and personalized drug treatment. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/nature04648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hagos FT, Empey PE, Wang P, Ma X, Poloyac SM, Bayir H, et al. Exploratory application of neuropharmacometabolomics in severe childhood traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):1471–1479. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]