Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health problem, with limited pharmacological options available beyond symptomatic relief. The renin angiotensin system (RAS) is primarily known as a systemic endocrine regulatory system, with major roles controlling blood pressure and fluid homeostasis. Drugs that target the RAS are used to treat hypertension, heart failure and kidney disorders. They have now been used chronically by millions of people and have a favorable safety profile. In addition to the systemic RAS, it is now appreciated that many different organ systems, including the brain, have their own local RAS. The major ligand of the classic RAS, Angiotensin II (Ang II) acts predominantly through the Ang II Type 1 receptor (AT1R), leading to vasoconstriction, inflammation, and heightened oxidative stress. These processes can exacerbate brain injuries. Ang II receptor blockers (ARBs) are AT1R antagonists. They have been shown in several preclinical studies to enhance recovery from TBI in rodents through improvements in molecular, cellular and behavioral correlates of injury. ARBs are now under consideration for clinical trials in TBI. Several different RAS peptides that signal through receptors distinct from the AT1R, are also potential therapeutic targets for TBI. The counter regulatory RAS pathway has actions that oppose those stimulated by AT1R signaling. This alternative pathway has many beneficial effects on cells in the central nervous system, bringing about vasodilation, and having anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative stress actions. Stimulation of this pathway also has potential therapeutic value for the treatment of TBI. This comprehensive review will provide an overview of the various components of the RAS, with a focus on their direct relevance to TBI pathology. It will explore different therapeutic agents that modulate this system and assess their potential efficacy in treating TBI patients.

Keywords: Angiotensin, Mas receptor, Neurodegeneration, Therapeutics, Brain, Injury

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains a leading cause of death in young people. Despite numerous clinical trials attempting to develop therapies, current treatment options are limited to early emergency surgery and symptomatic care [1]. TBI results in a complex cascade of pathological events. Immediately after the initial injury occurs, many cascades are activated, resulting in changes in cerebral metabolism, cerebrovascular alterations, increased inflammation, blood–brain barrier dysfunction, neuronal viability, excitotoxicity, glial reactivity, and immune modulation [2–4]. These intricate interlinked changes result in processes that lead to neurodegeneration and increase the risk for the later development of neurodegenerative disease [5, 6]. Further, the resultant processes, which occur in the minutes, hours, days, and even months after injury, amplify the initial injury, worsen the consequences, and provide a window of therapeutic intervention to improve recovery. Severe injuries lead to deficits that profoundly affect different aspects of a patient's life; even so-called "mild" TBI can result in persistent issues related to cognition, mood, sleep, and memory [7, 8]. Drugs targeting the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) have been developed to treat cardiovascular and renal diseases, including hypertension, and they have been used clinically for many years [9–12]. In addition to their known ability to lower blood pressure (BP), they have many other effects, including reducing inflammation, improving metabolic homeostasis, and decreasing oxidative stress [13]. Given the involvement of the RAS in the brain, RAS-targeting drugs have been proposed as a potential treatment for various central nervous system (CNS) conditions, including TBI [14, 15]. Angiotensin II (Ang II) receptor blockers (ARBs), drugs that act as antagonists at the Ang II Type I receptor (AT1R), enhance recovery in different rodent models of TBI [16, 17]. The efficacy of these drugs in improving multiple aspects of TBI recovery in animal models, along with their established clinical safety profile, has provided a rationale for initiating clinical trials to evaluate ARBs in TBI.

Overview of the Renin-Angiotensin System

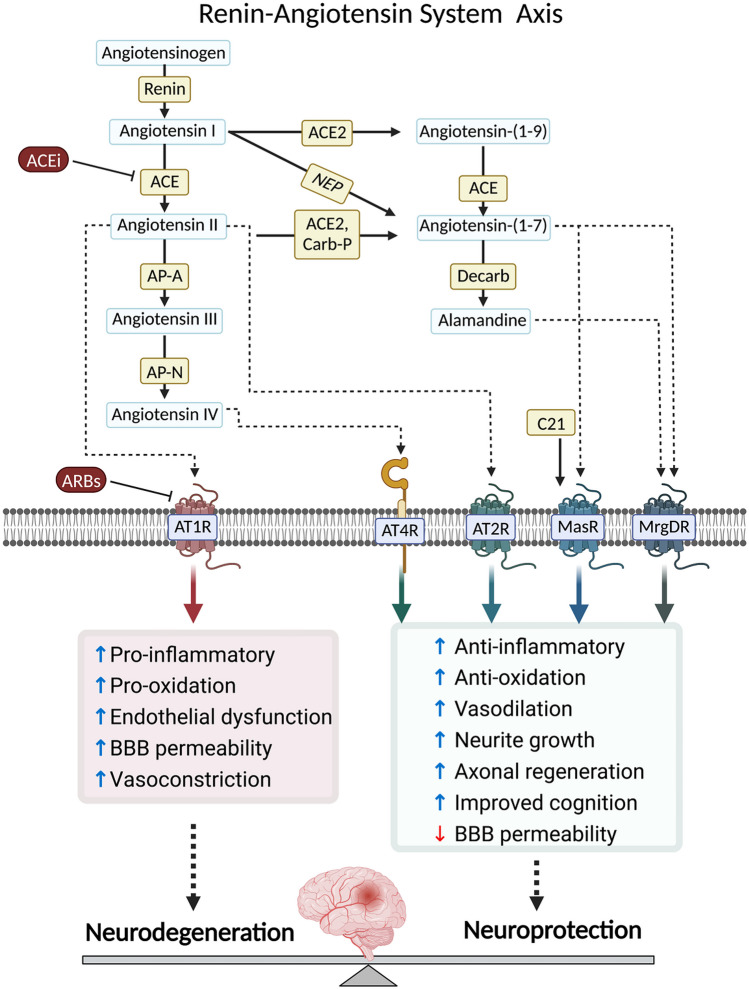

The RAS is a well-studied hormonal pathway that regulates blood pressure (BP) and fluid balance in vertebrates. In the most straightforward paradigm, a reduction of BP results in increased secretion of the enzyme renin from the kidneys into the bloodstream. Renin then breaks down the large 453 amino acid angiotensinogen (AGT) protein, to release an inactive 10 amino acid peptide called Angiotensin I (Ang I). Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), produced by the endothelial cells in the lungs, cleaves Ang I to produce the highly active 8 amino acid Ang II peptide. Ang II is the main effector peptide of the RAS. It acts as a ligand for the G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), AT1R, and Angiotensin II Type 2 receptor (AT2R) (Fig. 1). Ang II binding to AT1R in blood vessels triggers vasoconstriction, which leads to an elevation in BP. This mechanism serves as a compensatory response to counteract the initial decrease in BP, thereby restoring balance [18]. The BP can be modulated through physiological means other than RAS signaling. Likewise, RAS signaling can also affect various physiological characteristics beyond BP control [19, 20]. Furthermore, BP regulation that occurs via RAS modulation cannot be attributed solely to its classical signaling pathway. Over the last few decades, a comprehensive, counter-regulatory RAS system has been described that includes unique cleavage products of AGT, multiple enzymes that catalyze these cleavage events, and new receptors for some of these cleavage products. Almost all components of the RAS and the “counter-regulatory RAS” play a role in BP modulation [21]. However, just as with the classic RAS, the duties of the counter-regulatory RAS extend beyond hemodynamic regulation [22–25].

Fig. 1.

The renin-angiotensin system axis is involved in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection signaling pathways. The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is crucial in regulating physiological processes. The active component of RAS, angiotensin II (Ang II), is generated through the activation of renin, which converts angiotensinogen (AGT) into Ang I. Ang I is then cleaved by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) to produce Ang II. The physiological effects of RAS are mediated by Ang II type 1 receptors (AT1Rs). However, excessive Ang II production or increased AT1R activity can lead to pathological conditions, increasing pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidation proteins, endothelial dysfunction, blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown and vasoconstriction. Strategies to control an overactive RAS include reducing Ang II production using renin or ACE inhibitors or blocking AT1Rs with angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). Alternative pathways interact with the system. These pathways involve the metabolism of AGT by kallikrein to produce Ang (1–12), followed by chymase-mediated conversion to Ang II. Another pathway consists of Ang (1–9) formation from AGT or Ang I by ACE2, which is further converted to Ang-(1–7) by ACE. ACE2 can also directly generate Ang (1–7) from Ang II. Additionally, Ang I can be converted to Ang (1–7) by neutral endopeptidase (NEP). Ang (1–7) activates the Mas receptor (MasR). Ang II can be further processed into Ang III by Aminopeptidase A (APA), and Ang III can be cleaved by Aminopeptidase N (APN) to produce Ang IV. Ang III and IV are believed to stimulate AT1Rs and insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase (IRAP) respectively. Ang II also activates a second receptor, the Ang II type 2 receptor (AT2R), which can exert neuroprotective effects and counterbalance the neurotoxic effects of AT1R overstimulation. Other receptors in the RAS, such as angiotensin type 4 receptors (AT4R), Mas receptor or MAS-related G-protein coupled receptor (MrgDR) are involved in anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative pathways, vasodilation, neurite growth, axonal regeneration, cognition and reduction of BBB permeability

Components of the classic RAS and the counter-regulatory RAS are present in various organ systems throughout the body, including the kidney, skin, heart, and bone marrow [26]. Many tissues contain all the protein components needed to support a local RAS independent of the classical renal-pulmonary-hepatic system [27]. These locally active RAS systems have distinct microenvironment roles, contributing to physiological and pathological processes [26]. Over the last few decades, researchers have implicated the local RAS in diverse diseases, from autoimmunity and cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders [9, 23, 28]. Drugs targeting the RAS can influence both the systemic RAS and the local RAS systems, and their therapeutic benefits may arise from actions at multiple levels. The brain has its own local RAS, able to influence many normal and pathological processes independent of the systemic RAS through autocrine, paracrine, and potentially intracrine mechanisms [29]. There is substantial evidence highlighting the impact of the brain RAS on the pathophysiology of TBI, which underscores the significant potential to target the RAS for TBI therapeutics [30]. Several FDA-approved drugs that modulate the RAS exist and could be repurposed for TBI treatment. Initial studies have explored ARBs in rodent models and have advanced to clinical trials for TBI (NCT05826912). However, other classes of FDA-approved RAS-targeting drugs are available, as well as drugs under development that focus on different components of this intricate system. Hence, there exists significant potential for therapeutic engagement with the RAS system. This review summarizes the established and potential associations between the RAS and TBI. It will provide insights into the brain’s local RAS and the characteristics of different drug classes that target the RAS, and their specific benefits in addressing the molecular and clinical consequences of TBI pathophysiology.

Renin-Angiotensin System in the Brain

The mammalian brain expresses genes and peptides that encode most components of the RAS [23, 31, 32]. AGT, the initial protein in the RAS, is widely distributed and expressed in areas not related to control of blood pressure and body fluid homeostasis. Astrocytes are the major cellular source of AGT in the brain, constitutively secreting this protein into the interstitial space and cerebrospinal fluid [33–35]. Several studies have established that neurons are also capable of producing AGT. Cultured neurons express and secrete AGT [33, 36, 37]. Further, immunocytochemical localization of AGT in the brain has revealed the presence of AGT in neurons in various brain regions including the ventrolateral medulla, hypoglossal nuclei, forebrain, thalamus, hypothalamus, and brain stem, magnocellular neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), paraventricular nucleus, rostral ventral lateral medulla (RVLM), and subfornical organ (SFO) [35, 38–41].

Renin and Prorenin

The enzymatic activity of renin, responsible for cleaving AGT to generate Ang I, is the rate-limiting step in the RAS [42]. Neither renin nor AGT can pass through the blood brain barrier (BBB). Therefore, a local brain RAS will only exist in the brain if renin is also present, or if other brain enzymes generate Ang I from AGT. Renin-like enzymatic activity was first demonstrated in dog and rat brain homogenates [39, 43–45]. Further studies revealed the presence of intracellular renin in the brain [46] and its effect on blood pressure regulation [43]. However, the presence of active renin in the brain is still the subject of considerable and unresolved debate [47–49]. It is possible that the low renin levels found in the brain could enter through the bloodstream, or they could originate from intracellular sources only [50]. Studies have discovered intracellular renin within both neurons and astrocytes, although the function of intracellular components remains unclear as most RAS-related receptors are membrane-bound [42, 51–55]. Renin and its zymogen, prorenin (PRO), co-exist and possess the ability to cleave AGT into Ang I; though renin exhibits greater activity [56]. The PRO receptor (PRR) binds to both PRO and renin, enhancing their enzymatic activity [57]. While PRR serves as a biochemical catalyst to enhance PRO and renin activity, various signaling events occur following the binding of PRO to PRR [58]. In the human brain, PRR is most highly expressed in the pituitary gland and the frontal lobe [59]. Extracellular renin readily influences neuronal function, as recent in vitro studies show that renin activates MAP kinase signaling through the PRR, reducing neuronal activity [60]. PRR blockers have been developed and have demonstrated the ability to protect neuronal activity in the presence of excess renin [57, 60, 61]. Interestingly, TBI in rodents increases mRNA expression of renin but not PRR [62]. Cerebral hypoperfusion in mice, a feature often seen in TBI, also led to increased brain renin activity, and enhanced expression of angiotensinogen [63]. Treatment with the FDA approved renin inhibitor, Aliskiren, lowered brain renin activity, and reduced oxidative stress, glial activation, and spatial working memory deficits associated with this injury [51, 64–66]. Collectively, these data suggest that renin inhibition may be beneficial following TBI.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE)

After renin cleaves AGT, ACE plays a crucial role in converting the inactive decapeptide Ang I into the active vasoactive octapeptide Ang II. Initially identified in the lungs and vascular endothelium, ACE is expressed in various regions and cell types within the brain, with prominent expression in the caudate nucleus and choroid plexus, as well as in cerebrovascular endothelial cells [67–69]. ACE, a zinc carboxypeptidase, is largely extracellular, anchored by its C-terminal into the cell membrane [70]. Within the body, sACE, the main form of ACE, contains two active sites with distinct properties, allowing for differential processing of peptide substrates. This property offers the potential for targeted inhibition of ACE at specific sites [71]. In addition to Ang I, ACE also acts on other substrates in the CNS, including bradykinin, dynorphin, β-amyloid, substance P, met-enkephalin, and neurotensin [72, 73]. The activity of ACE influences the production of Ang II, with higher ACE activity leading to increased levels of Ang II in the brain.

Angiotensin II

Ang II is the primary ligand for AT1R and AT2R, initiating various signaling pathways and exerting diverse effects. Neuronal cell bodies in the PVN and SON are rich in Ang II, as evidenced by immunostaining. Additionally, Ang II has been detected in other hypothalamic nuclei, brainstem nuclei, and circumventricular organs such as the SFO, median preoptic nucleus (MnPO), and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) [74–76]. Its presence in these regions suggests a role in regulating cardiovascular function and drinking behavior, potentially functioning as a neurotransmitter [77, 78]. Although Ang II levels in the brain are generally low, systemic Ang II can influence neurons in the circumventricular organs (CVO), which are not protected by the BBB and serve as an interface between the brain and systemic circulation. The debate regarding the presence of renin in the brain and the synthesis of Ang II within the brain has led to speculation that Ang II could be produced intracellularly in neurons, acting as a neurotransmitter released at synapses by specific Ang II neurons [43, 55]. The abundant expression of AT1R on neurons in various brain regions suggests that Ang II impacts multiple brain functions [79]. However, the precise mechanism of Ang II generation and its transport to reach these receptors are still the subject of ongoing investigation.

ACE/Ang II/AT1 Receptor Signaling

AT1Rs are highly expressed in various regions of the brain, including the anterior pituitary, area postrema, lateral geniculate body, inferior olivary nucleus, median eminence, the NTS, anterior ventral third ventricle region, and the paraventricular, preoptic, and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus [31, 35, 38, 79]. They are also found in the amygdala, hippocampus, cerebellum, caudate putamen, striatum, ventral tegmental area, and substantia nigra [29, 80]. Furthermore, AT1Rs are expressed in cerebral endothelial cells, where they regulate cerebrovascular homeostasis [81]. Initial studies to localize AT1Rs utilized autoradiography and immunohistochemistry techniques. However, the specificity of some commercially available AT1R antibodies has been called into question [82], so care must be taken in evaluating localization studies by antisera alone. Rodents have two AT1R genes, Agtr1a and Agtr1b, in contrast to humans with a single Agtr1 gene [83]. These receptor subtypes exhibit functional differences and are expressed in different tissues throughout the rodent body [84, 85]. While the overall function and physiological significance of the Ang receptor system remain conserved across species, the presence of multiple Ang receptor subtypes in rodents adds a complexity when studying the role of these receptors in rodent models [84].

AT1Rs play a crucial role in mediating various detrimental effects of Ang II, including vascular proliferation, inflammation, vasoconstriction, and oxidative stress [86–88]. Activation of AT1Rs primarily triggers signaling through the Gq pathway, activating phospholipase C, increased intracellular calcium levels, and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate concentrations. This activation also involves stimulating kinase pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK, p38, JNK) and JAK/STAT pathways [89–91]. The increase in intracellular calcium levels activates myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which phosphorylates myosin and causes smooth muscle contraction, resulting in vasoconstriction [92]. These signaling cascades initiated by AT1R activation can lead to diverse and often harmful effects, depending on the cell type. In the brain, AT1R activation contributes to the physiological regulation of various functions, including cerebral circulation control, BBB integrity, central sympathetic activity, hormonal production and release, and regulation of the brain's innate immune response [93–97]. However, overactivation of brain AT1R is associated with a pro-inflammatory state that can lead to hypertension, cerebral ischemia, and behavioral and cognitive dysfunction [98–100]. AT1R plays a role in several cerebrovascular diseases, including ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, subarachnoid aneurysms, and neurodegenerative processes (e.g., Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases) [101]. One potential mechanism of action is the activation of mediators such as NF-κB [102]. Additionally, downstream substrates involved in AT1R signaling include NADPH oxidases (NOX), major sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within cells. Inhibition of NOX prevents the attenuation of endothelium-dependent relaxation caused by Ang II in cerebral arterioles, suggesting the involvement of NOX in mediating the detrimental effects of Ang II on cerebrovascular regulation [103]. Furthermore, Ang II also induces cerebrovascular remodeling [104], alters autoregulation [81] and disrupts the BBB [96]. Increased levels of Ang II in aging brains have been linked to age-related cerebrovascular damage, with elevated endothelial NOX2 activity leading to higher ROS levels and endothelial dysfunction [105]. These effects were reduced in mice with endothelial-specific Nox2 deletion [105].

ACE/Ang II/AT2 Receptor Signaling

Ang II can also activate a distinct G protein-coupled AT2R, which shares only 34% amino acid similarity with the AT1R [106]. The affinity of Ang II for the AT2R is ten-fold higher than that for the AT1R, making AT2R signaling more prominent in tissues where both receptors are present [107]. However, at least in the central nervous system (CNS), AT1R and AT2R are rarely co-expressed within the same cells [108]. While AT2R expression is high in neonates, it becomes more limited and localized in adults [109]. Nevertheless, AT2R expression is increased in a multitude of disease states in adults [110]. Determining the expression of AT2R in the brain has been challenging due to its low expression levels and the questionable specificity of commercial AT2R antibodies [111, 112]. However, the use of AT2R-eGFP reporter mice has facilitated a more detailed characterization of AT2R in the rodent brain [113]. In the brain, AT2R expression appears to be predominantly neuronal. It is found in regions associated with regulating BP, fluid balance, metabolism, cognitive function, stress responses, and mood [113]. AT2Rs are moderately expressed in certain cardiovascular regulatory nuclei such as the NTS and RVLM, as well as the medial amygdala, cerebral cortex, and locus coeruleus [31, 79, 114]. Stimulation of AT2Rs generally leads to anti-fibrotic, vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, and neuroregenerative effects [109, 115, 116]. In neurons, AT2R functions to modulate excitability and promote neurite outgrowth [114, 117, 118]. Mice lacking AT2R display anxiety-like behavior and alterations in normal exploratory tendencies [119]. Activation of the AT2R generally results in protective signaling that mitigates some deleterious disease-related pathways and acts to counteract signaling by the AT1R [115, 120, 121]. AT2R signaling, therefore, constitutes part of the counter-regulatory pathways [109, 110]. AT2R activation reduces oxidative stress in ischemic stroke [122]. The intracellular signaling initiated by AT2R is more diverse than many other GPCRs. AT2R stimulates phosphatases such as MAPK phosphatase (MKP-1), serine-threonine protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A), and SH2 domain-containing phosphatase (SHP-1), leading to reduced protein phosphorylation. Additionally, AT2R can activate non-canonical G protein and β-arrestin-independent pathways, which appear to be cell-specific [123]. AT2R activation reduces oxidative stress, inhibits NF-κB signaling, and decreases cytokine expression, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects that oppose AT1R stimulation [88]. Furthermore, AT2R stimulation has been shown to induce the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), promoting neuronal survival [124].

ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR Axis

Ang II and its subsequent actions on AT1Rs and AT2Rs does not represent the final stage of the RAS. Another crucial enzyme, ACE2, cleaves a single amino acid from Ang II, specifically the terminal phenylalanine, generating a heptapeptide called Ang-(1–7) [125–128]. The loss of this single residue from Ang II dramatically alters ligand-receptor interactions. Ang-(1–7) signals through the Mas receptor (MasR) and possesses little ability to stimulate AT1R signaling [129, 130]. Ang-(1–7) can also signal through the related GPCR MAS-related G-protein coupled receptor MrgD [131], and potentially also through the AT2R [132]. Neprilysin, a neutral endopeptidase, can also generate Ang-(1–7) directly from Ang I [133]. Multiple signaling cascades are initiated upon the binding of Ang-(1–7) to MasR. In vitro studies that over-express and activate MasR in HEK293 cells describe intracellular increases of cAMP [129]. MasR activation promotes phosphorylation of Akt and upregulation of eNOS [134]. Ang-(1–7) possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive properties; effects in opposition to Ang II /AT1R signaling [128, 135, 136]. Just as Ang II increases MAPK signaling, promotes immune cell proliferation, and increases blood pressure, Ang-(1–7) signaling via the MasR reduces MAPK signaling, attenuates immune cell proliferation, and lowers blood pressure [137–140]. Furthermore, both MasR and AT2R form heterodimers with AT1R that result in its inactivation. There is therefore a possibility that some of the observed neuroprotective benefits of MasR and AT2R activation are due to their ability to inactive AT1R [141, 142].

Thus, ACE2 catalyzes a major shift in the RAS, from the pro-inflammatory, vasoconstrictive Ang II to the vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory actions of Ang-(1–7). ACE2 is a type 1 transmembrane protein whose active site is found on the extracellular surface of many different cell types [143] and which gained notoriety as the cellular receptor for SARS-CoV2 [144]. ACE2 is expressed in both neurons and cerebroendothelial cells [23, 55, 145, 146]. MasR is present in the murine forebrain, where it co-localizes with neurons in the RVLM, cerebral cortex, thalamus, and hippocampus, as well as within cerebroendothelial cells [147, 148]. However, its presence has also been observed in microglia within the mouse brain, and in vitro, studies have demonstrated its effects in primary rat astrocytes [149, 150]. Each component of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis has been identified in the mammalian brain, and their function has been partially characterized following brain injury [23]. The ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis is therefore thought to be neuroprotective, promoting neuron survival and preserving brain function after various CNS insults.

Ang IV/AT4R/IRAP Receptor Signaling

The hexapeptide Ang IV is formed following sequential cleavage of Ang II by aminopeptidase A then Aminopeptidase N. Ang IV binds to the transmembrane IRAP, that is localized mainly on intracellular endosomes, often together with the glucose transporter GLUT4 [15, 38, 151–153]. Ang IV binding inhibits IRAP activity [154], resulting in the increased half-life of several peptide substrates of IRAP including vasopressin, oxytocin, somatostatin and eNOS [155]. Ang IV binding to IRAP also inhibits intracellular GLUT4 trafficking, leading to increased neuronal glucose uptake which could have beneficial effects on neuronal function [152, 156]. IRAP is highly expressed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and amygdala and plays a key role in cerebral microcirculation and cognition [157, 158]. Ang IV also may signal through the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor, c-Met [159] which has many beneficial effects in the CNS. Ang IV signaling appears to affect many targets within the CNS, and Ang IV administration parallels benefits of cognition seen with AT2R and MasR signaling. Interestingly, Ang IV can bind to the AT2R, with an IC50 value in the nanomolar range, and can thus also be considered as an AT2R agonist [107]. Nonetheless, most Ang IV effects are mediated through IRAP (which is designated the AT4R). Ang IV signaling via the AT4R is a potent enhancer of memory and cognition potentially through increased release of acetylcholine and enhancement of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus [160–162]. AT4R signaling is anti-inflammatory, improves memory and cognition, and enhances cerebral blood flood (CBF) [157, 158]. Ang IV administration has also been proven protective against ischemic stroke in rats [163]. Ang IV dose dependently decreased neurological deficits, cerebral infarct volume, and overall mortality. Further, it promoted a redistribution of CBF to ischemic regions within minutes of arterial occlusion [163]. Ang IV administration also restored short-term memory, as well as spatial learning and memory in amyloid precursor protein (APP) mice [164]. Interestingly, it has been suggested that some of the beneficial cognitive effects of ARBs are mediated by the AT4R. There have not been studies on AT4R signaling or targeting after TBI. As AT4R stimulation enhanced memory, increased CBF and reduced inflammation and oxidative stress within the CNS, it is a valid and intriguing target for TBI therapeutics.

Sex Differences in Brain RAS

Sex differences exist in the functioning of the RAS, which contributes to variations in RAS activity in the brain [165, 166]. Both estrogen (E2) and testosterone regulate the RAS [165, 167]. E2 activity is inversely associated with RAS activation [168], as it increases AGT levels while decreasing renin and ACE activity [169–171]. E2 also downregulates the expression of AT1R and upregulates the expression of AT2R, shifting the balance of the RAS towards a more vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory state [172]. Additionally, E2 promotes the production of Ang-(1–7) through ACE2 regulation, further enhancing the anti-inflammatory state [173]. When E2 levels are high during pregnancy, renal and urinary levels of Ang-(1–7) and ACE2 expression significantly increase [174]. E2 regulation of ACE2 also provides protection against cardiac dysfunction [175]. In contrast, testosterone can increase the expression of AGT, ACE and AT1R, leading to a more vasoconstrictive and pro-inflammatory state [167, 172]. These differences in RAS contribute to the lower arterial pressure levels observed in premenopausal women compared to men [176]. These sex differences likely extend to the local brain RAS system as well, suggesting that the balance of the brain RAS in premenopausal women is more anti-inflammatory with reduced levels of oxidative stress compared to postmenopausal women and all men. This aligns with the higher inflammatory responses observed in male mice compared to female mice following brain injury [177]. Some sex specific behavioral responses to Ang II and drugs that target this system are now being reported [166] but this area requires further study. These studies imply that males and post-menopausal women could display a greater response to ARBs and other RAS targeting drugs after TBI compared to younger women, where higher E2 levels have reduced the prominent pro-inflammatory ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis.

Drugs that Target RAS: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

ARBs are FDA approved drugs that act as antagonists at the AT1R. They are widely used for treating hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, renal disorders, and metabolic conditions [13, 123, 178]. They were developed in the 1990s after the discovery of aldosterone antagonists and ACE inhibitors, which also target the RAS [178]. ARBs offer improved safety profiles compared to these drugs [179]. ARBs selectively bind to AT1R with significantly greater affinity (approximately 10,000-fold) than AT2R, although the specific drug used can affect this binding affinity [180, 181]. Currently, there are currently eight clinically used ARBs: azilsartan, candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, and valsartan [123, 182]. These ARBs are non-peptide compounds with chemical heterogeneity, leading to differences in their pharmacokinetic profiles and mechanisms of binding to AT1R (extensively discussed elsewhere [180, 183]). Among them, candesartan is considered the most potent for treating hypertension, and eprosartan is the least potent [183]. Most ARBs are administered orally. Azilsartan, candesartan, and olmesartan are prodrugs that are converted into active forms by enzymes in the gut, liver, or serum [180]. Some ARBs, such as irbesartan, telmisartan, candesartan, and olmesartan, act as insurmountable antagonists at the AT1R, while others are surmountable [123]. Additionally, valsartan exhibits inverse antagonistic effects on the AT1R, allowing it to have an impact via the receptor even in the absence of Ang II [184].

Blood Brain Barrier Permeability of ARBs

ARBs have many beneficial effects within the CNS. Whether ARBs achieve their CNS benefits via their influence on cerebroendothelial cells, through peripheral mechanisms or through crossing the BBB to directly impact cells in the CNS remains unknown. Another possible route of influence is by modulating cells in the hypophysis and other CVOs that are not protected by the BBB but express the AT1R [108]. During pathological conditions such as stroke, meningitis, and TBI, the BBB is compromised, allowing easier penetration of molecules, including ARBs [123], into the brain. The extent to which different ARBs can cross the BBB has been debated. However, there is a growing consensus that telmisartan and candesartan can cross the BBB [185].

Telmisartan has the strongest evidence that it can cross the BBB. It has the highest lipid permeability of all the ARBs [186, 187], and its ability to enter the CNS, was demonstrated in PET scans in macaque monkeys [188]. The BBB permeability of candesartan is more debatable. While some studies have shown that candesartan crosses the BBB and inhibits central AT1R effects in non-injured brains [189–191], one report indicated that candesartan did not penetrate the BBB in rats infused with Ang II [192]. Additionally, candesartan is less lipophilic than telmisartan. The therapeutic relevance of BBB crossing ARBs was recently demonstrated in a metaanalysis that showed that telmisartan and candesartan, designated as “the BBB crossing ARBs”, promoted better protection against memory decline in older adults than non-BBB crossing ARBs when used as chronic antihypertensive medications [193]. Further evidence supporting the protective effects of BBB-penetrating ARBs in the CNS was observed in Alzheimer's disease patients, with or without APOE e4 carrier status, who showed reduced cognitive decline when treated with these ARBs [194, 195]. Therefore, while there are evident neuroprotective benefits from the peripheral effects of ARBs, the ability to permeate the CNS directly may confer additional therapeutic advantages.

AT1R Effects of ARBs

AT1R overactivity is a contributing factor to endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and oxidative damage in various brain disorders [123, 178, 196]. In the CNS, AT1R hyperactivity generates cellular damage, leading to BBB breakdown, amplified leukocyte infiltration, mitochondrial dysfunction, glutamate excitotoxicity, and metabolic complications. Blocking AT1R activation is therefore therapeutic in many chronic disease states. It is now recognized that some effects of ARBs are mediated indirectly by the increased availability of Ang II. For instance, the protective effect of irbesartan against acute lung injury in mice is completely blocked by a MasR antagonist, indicating that the protection is mediated through the generation of Ang-(1–7) from excess Ang II [197]. Additionally, in the presence of an ARB, there is more Ang II to activate AT2Rs, providing an indirect agonistic effect on AT2R [123]. Since AT2R signaling counteracts that of AT1Rs, this AT2R agonism in the presence of ARBs is thought to augment ARB effects [198].

RAS-Independent Effects of ARBs

Telmisartan, and to a lesser extent candesartan, irbesartan, and losartan, exhibit partial agonistic activity on the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) receptor [180, 199, 200]. Among these, telmisartan demonstrates the strongest partial agonism of PPARγ and many of its effects can be blocked by PPARγ antagonists, indicating the importance of this activity in telmisartan's actions [180]. In a mouse model of TBI, the neuroprotective effects of both telmisartan and candesartan were reduced by a PPARγ antagonist, showing that this partial PPARγ agonism contributes to the efficacy of both ARBs following TBI [201]. The ability of certain ARBs to activate PPARγ signaling expands their target range, as PPARγ receptors are widely expressed, and this activation leads to additional anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and metabolic effects [202, 203]. It is worth noting that although AT1R blockade and PPARγ agonism can act as independent mechanisms, there is a connection between these pathways, as AT1R signaling suppresses PPARγ induction, and PPARγ signaling reduces AT1R activation [204]. In particular, telmisartan exhibits other non-AT1R dependent anti-inflammatory effects by stimulating CaMKKβ-dependent AMPK activation in microglia, reducing microglial activation induced by Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [205]. Furthermore, telmisartan has been shown to activate the PPARγ pathway, adding to its unique anti-inflammatory and metabolic regulatory actions [206]. Overall, telmisartan stands out among the ARBs due to its distinct stimulation of other pathways and non-AT1R-dependent effects, making it a unique drug with diverse anti-inflammatory and metabolic regulatory actions.

Benefits of ARBs in TBI Pathology

Effects of ARBs on Animal Models of TBI

In animal TBI models AT1R blockade improves outcomes post-injury (Table 1, Fig. 2). Interestingly, the neuroprotective effects of ARBs in TBI models were seen at doses that did not reduce blood pressure [201]. These drugs improved CBF, reduced inflammatory markers and oxidative stress, and stabilized the BBB [17, 201]. Candesartan has consistently demonstrated beneficial effects on neurological function and secondary outcomes in rodent models of TBI [16, 17, 201, 207–211]. The therapeutic window for candesartan and telmisartan to reduce lesion volume was up to 6 h post-TBI [201], similar to the timeframe for acute stroke treatment [212].

Table 1.

Effects of ARBs on TBI based on preclinical studies. Fluid percussion injury (FPI), controlled cortical impact injury (CCI), days post-injury (dpi), hours post-injury (hpi), Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), cerebral blood flow (CBF), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, Angiotensin II type 1 receptor knockout (AT1R-KO) mice, subcutaneous (s.q.), intraperitoneal (i.p.)., endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), interleukin (IL)

| Drug | In vivo model | Administration route and dose | Sex | Treatment duration | Therapeutic Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | CCI in mice | 0.1 mg/kg, i.p, 6 hpi, randomized | males | 3, 29 dpi | Reduces expression of genes involved in the inflammatory response, and altered genes involved in angiogenesis, interferon signaling, extracellular matrix regulation including integrins and chromosome maintenance and DNA replication | [208] |

| Candesartan | CCI in mice | 1 mg/kg/day, s.q. at 5 h before injury, randomized and blinded | males | 1, 3, 28 dpi | Decreases the number of dying neurons, activated microglial cells, lesion volume, increased CBF and reduced the expression of TGF- β1, while increasing expression of TGF- β3. Improves motor and cognitive function | [17] |

| Candesartan | CCI in mice | 0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/kg, s.q., 4 hpi, randomized and blinded | males | 5 dpi | Reduces brain damage, brain edema formation, microglia activation, IL-6, IL-1β, iNOS, TNF-α, and improves neurologic function | [16] |

| Candesartan | CCI in mice | 0.1 mg/kg s.q. at 0.5hpi, randomized and blinded | males | 5 dpi | Reduces brain damage, microglial activation, and neutrophil infiltration, and increases of anti-inflammatory markers (arginase 1 and chitinase3-like 3) | [212] |

| Candesartan | Marmarou weight drop injury in rats | 0.3 mg/kg i.p. at 0.5hpi, randomized and blinded | males | 1 dpi | Reduces intracranial pressure, oxidative stress, and improves neurological outcome | [215] |

| Candesartan | Marmarou weight drop injury in rats | 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg i.p. at 0.5hpi, randomized | females | 1 dpi | Interaction with 17β-estradiol brain edema and intracranial pressure | [209] |

| Candesartan, Telmisartan | CCI in mice | 0.1, 0.5 or 1 mg/kg, i.p. and s.q., 6 hpi randomized and blinded | males | 3, 28 dpi | Reduces lesion volume, neuronal injury and apoptosis, astrogliosis, neutrophil infiltration, nitrated proteins, astrogliosis, microglial activation, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increases CBF. Improves motor and cognitive function | [202] |

| Telmisartan | CCI in mice | 5 to 40 mg/kg by oral gavage 1 h before injury, randomized | males | 1, 3 dpi | Reduces cerebral edema, apoptosis, lesion volume, and expression levels of NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-1β and IL-18 expression | [216] |

| Losartan | CCI in mice | 3 to 10 mg/kg by oral gavage, 1 hpi randomized and blinded | males | 3 dpi | Reduces brain lesion volume, neuronal apoptosis and ER stress protein ATF4 and eIF2α. Improves neurological and motor function. Reduces TNF-α expression and increased IL-10 expression | [217] |

| none | CCI in AT1R-KO mice | none | males | 3 dpi | Protects BBB integrity and rescued occludin and ZO-1. Decreases APP expression and Aβ 1–42, Aβ 1–40 levels. Inhibits AQP4 depolarization | [218] |

| Ang-(1–7) | CCI in mice | 1 mg/kg dose, by i.p., 2 hpi, randomized | males | 5 dpi | Reduces pTau and GFAP expression in cortical and hippocampal regions | [371] |

| Ang-(1–7) | CCI in mice | 1 mg/kg/day, s.q., 1 or 6 hpi randomized | males | 3, 29 dpi | Reduces lesion volume at 3, 10, 24, and 29 dpi. Attenuates motor deficits at 3 dpi and improves performance in learning and memory. Reduces microgliosis, astrogliosis and neuronal and capillary loss | [211] |

| ACEi: Captopril, Enalapril | Marmarou weight drop injury in rats | 5 hpi randomized | males | 3, 7 dpi | Captopril increases substance P and exacerbates motor deficits. Enalapril exacerbates motor deficits | [210] |

| AT2R agonist, compound 21 (C21) | CCI in mice | 0.03 mg/kg, i.p. 1 and 3 hpi randomized | males | 1, 5 dpi | Ameliorates NSS, reduces activation of PARP and caspase 3. Reduces inflammatory markers IL-1β and TNF-α, and eNOS phosphorylation | [213] |

| AT2R agonist, compound 21 (C21), and AT2R KO | CCI in mice | 0.03 and 0.1 mg/kg, i.p. at 0.5hpi, randomized | males | 1, 5 dpi | C21 and AT2R KO did not show differences in the extent of the TBI-induced lesions and secondary damage | [348] |

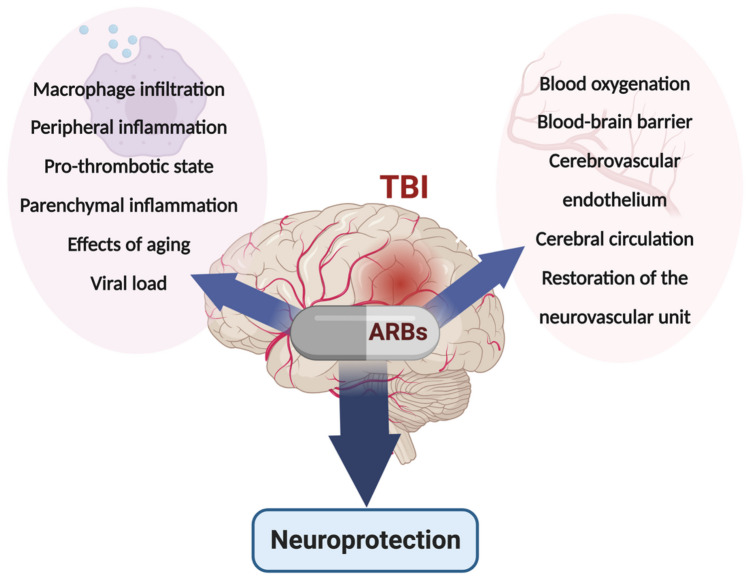

Fig. 2.

Neuroprotective effects of ARBs. Direct mechanisms of brain injury include blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakage, endothelial damage, macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, parenchymal inflammation, local thrombosis, and alterations in cerebrovascular flow. Direct mechanisms of ARB neuroprotection from TBI include protection of the blood–brain barrier, the vascular endothelium, the neurovascular unit, cerebrovascular flow, and reduction of parenchymal inflammation, macrophage and neutrophil infiltration, and local thrombosis

Administration of candesartan via intraperitoneal (i.p.) or subcutaneous (s.q.) routes at doses ranging from 0.1 to 1 mg/kg during the first four weeks post-TBI resulted in a wide range of neuroprotection. Candesartan effectively reduced brain damage, CBF, astrogliosis, and inflammation while improving neurological function [201, 207, 208, 211, 213]. Telmisartan achieved similar neuroprotective effects as candesartan following a controlled cortical impact injury, although its behavioral benefits were not as robust [201]. Another ARB, losartan, significantly reduced lesion volume, neuronal apoptosis, ER stress, and proinflammatory cytokines three days post-TBI [214]. Further, global AT1R knockout (KO) mice demonstrated more favorable outcomes after TBI than wild type mice [201, 215], suggesting that endogenous AT1R signaling impedes recovery from TBI in this mouse model. Removal of AT1R expression produced protection of BBB integrity and rescued occludin and ZO-1 expression and resulted in decreased APP expression at 3 days post-TBI [215]. Although these studies show that ARBs can enhance cognitive and motor abilities while also decreasing brain inflammation and lesion size, the majority of these studies employed methodology that does not translate easily to inform clinical studies. The reduction in lesion size in rodent TBI experiments has limited value in translating these results to clinical TBI patients. Of the nine published studies that examined efficacy of ARBs in rodent TBI models, seven started treatment either before injury or within 1 h afterwards (Table 1). Additionally, most studies were terminated within the first week after injury, not allowing for longer term assessment of efficacy (Table 1). Only one study, started treatment 6 h after injury, and examined behavioral and histopathology out to 29 days [201]. Also, all but one of these studies were performed on male mice and rats. Thus, more research is required to examine larger therapeutic windows for initiation of drug administration, and determining drug efficacy through different outcomes and at more chronic time points.

Anti-Inflammatory Actions of ARBs

TBI is characterized by acute cell injury and inflammation, which progresses to low level chronic inflammation that inflicts sustained secondary injury to CNS tissues [216, 217]. Protracted neuronal injury due to persistent neuroinflammation over months to years culminates in potential neurodegenerative or neuropsychiatric disorders that can potentially be mitigated by anti-inflammatory drugs [218]. ARBs have multiple anti-inflammatory mechanisms that can be utilized either acutely after injury, or more chronically to deal with persistent inflammation [13]. Considerable clinical data has accumulated to indicate that long term ARB administration has minimal side effects, and indeed may have positive cognitive benefits [219, 220].

There are multiple mechanisms of inflammation after TBI [216]. The release of damage associated molecular pattern mediators (DAMPs) from dead and injured cells can trigger inflammatory responses from microglia, as well as astrocytes and neurons [221, 222]. Breach of the BBB after TBI allows neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes to converge on injured CNS tissue to augment the inflammatory process [216]. Any breach to the external surface, depending on the severity of damage, can also introduce pathogens, which are potent inflammogens. One of the key DAMPs critical in neuroinflammation is HMGB1 [223–227]. Inhibition of HMGB1 has been associated with beneficial effects both in stroke and TBI [224, 226–228]. Various ARBs, including candesartan, irbsartan and telmisartan, inhibit the HMGB1 pathway when administered after stroke. Thus, they may also reduce inflammation after TBI [229].

Overactivation of brain AT1R by Ang II is associated with a pro-inflammatory state with the potential to exacerbate glial reactivity, cerebral ischemia, behavioral dysfunction, and various other disease processes [191, 230–232]. Although activation of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R pathway has not been conclusively shown after TBI, it is probable that AT1R signaling is activated. We have shown that Ang II is increased in the plasma and brain after controlled cortical impact injury in mice (unpublished data). Support for a detrimental role for AT1R signaling in the brain after TBI was shown by the reduced lesion volume in AT1R KO mice after a controlled cortical impact injury [201]. Additionally, these AT1R KO mice had reduced TUNEL positive cells, and reduced astrogliosis in comparison to wild type mice [201], indicating that the presence of the AT1R after injury was deleterious. Interestingly, there was no difference in Iba1 + staining, at 1 day post injury suggesting a lack of an immediate direct anti-inflammatory effect of the AT1R on microglia [201]. ARBs have powerful anti-inflammatory activity [232]. They can control dysregulated and excessive inflammation associated with increased AT1R activity in the CNS and the cerebrovasculature [233]. ARBs can reduce microglial activation and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases [234]. The anti-inflammatory effects of ARBs, evident even at low, sub-hypotensive doses, are crucial in reducing endothelial and vascular senescence, another acute injury mechanism [13]. Therefore, the ability of ARBs to antagonize AT1R signaling should significantly reduce inflammation.

The anti-inflammatory action of ARBs may involve both their AT1R antagonism and their drug-specific activation of PPARγ. PPARγ can block NF-κB signaling, scavenge transcriptional co-factors to reduce transcription, and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [203, 235]. Indeed, in human monocytes that do not express the AT1R, candesartan reduced ROS and NF-κB signaling, ameliorating inflammation produced by LPS, presumably by activating PPARγ [236, 237]. PPARγ protein is induced in the perilesional area after TBI in the mouse [238] and PPARγ agonists are protective in rodent models of TBI [239]. Telmisartan, uniquely, has other anti-inflammatory signaling properties, likely making it the most potent anti-inflammatory ARB [205]. Despite this, telmisartan was not as effective as candesartan at promoting recovery in mice after TBI suggesting that better control of inflammation was not the most critical factor in promoting recovery [201]. Both telmisartan and candesartan reduced microgliosis, neutrophilic infiltration, and overall lesion volumes [201]. This effect was reduced but not eliminated by a PPARγ antagonist [201]. Therefore, in a mouse model of TBI, ARB’s protective effects are mediated by both AT1R and PPARγ -dependent mechanisms.

ARBS Provide Neuroprotection by Regulating Cerebral Blood Flow

The expression of AT1R is high in both endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells [240, 241]. Ang II activation of AT1R leads to vasoconstriction, resulting in decreased CBF [242]. Prothrombotic effects of AT1R signaling can further compromise CBF through the formation of cerebral microthrombi [243, 244]. ARBs are beneficial in maintaining CBF in conditions such as hypertension and stroke [245, 246]. Following TBI, vasoconstriction leads to reduced CBF alongside disturbances in cerebral microcirculation [247, 248]. Studies have shown that ARBs can mitigate the reduction in CBF associated with TBI in mice [17]. ARBs therefore have the potential to preserve physiological CBF after TBI, that will contribute to optimal recovery.

Capillary density loss following TBI can occur due to mechanical damage or secondary biochemical processes [249]. Loss of vascular density compromises access of blood to the healthy brain parenchyma and can further exacerbate damage [250]. Therefore, preserving vascular density is crucial for enhancing TBI recovery. ARBs are known to increase the expression of angiogenic growth factors, promoting the development of blood vessels. In animal stroke models, candesartan has been shown to protect the vasculature and increase VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and BDNF [251, 252].

Additionally, candesartan promotes cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation in cultures of human brain endothelial cells under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions [253, 254]. Thus, it is worth investigating whether ARBs can reduce capillary loss following TBI. In addition to causing vasoconstriction of the cerebrovasculature, Ang II signaling via the AT1R triggers various molecular signaling pathways in cerebrovascular endothelial cells [86, 255]. Particularly relevant to TBI is Ang II's ability to induce a pro-inflammatory state through endothelial-dependent mechanisms. By stimulating COX-2 and NADPH oxidase, Ang II promotes endothelial dysfunction and increases the production of ROS, which can cause significant damage to brain tissue [242, 256–258]. Ang II signaling in endothelial cells also promotes the expression of cytokines, and chemoattractants such as endothelin-1, VCAM-1, I-CAM1, and integrins, which recruit inflammatory cells towards the vasculature [259, 260]. Similar molecular patterns are observed in the cerebrovasculature of spontaneously hypertensive rats. In rats, various ARBs can restore the endothelial/inducible nitric oxide synthase ratio, decrease TNFα levels, reduce ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA expression, and reverse macrophage infiltration in the cerebrovasculature [256, 261, 262]. Cerebral microvascular dysfunction can be functionally identified by assays of cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR). Global CVR is reduced in chronic TBI patients [263]. Although there is no literature as yet of the effect of ARBs on CVR after TBI, there is evidence that candesartan improves CVR in patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease or with vascular cognitive impairment [264]. The improvement in CVR in patients after a year of candesartan treatment was not seen in those patients who were taking the ACE inhibitor lisinopril [264].

Thus, the ability of ARBs to maintain CBF, acutely reduce inflammation in the cerebrovasculature, and enhance vascular recovery and angiogenesis in the long term are important factors that contribute to the effectiveness of ARBs after TBI. The blockade of AT1R's vasoconstrictive effects together with their anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties makes ARBs beneficial for maintaining and restoring the cerebral circulation after TBI.

ARBS Exert Neuroprotective Effects by Ameliorating Cerebral Edema and Improving Blood–Brain Barrier Function

Much of the BBB disruption that ensues immediately after TBI is caused by mechanical shear force. However, lasting BBB permeability is likely due to prolonged inflammation and deregulated astrocytic function, and here a role for Ang II/AT1R signaling could exist. Ang II/AT1R signaling increases BBB permeability in cultured brain microvessel endothelial cells [265]. In mice, chronic infusion of Ang II for 14 days led to cerebral microvascular inflammation and increased BBB permeability [266]. Interestingly, deletion or inhibition of AT1R attenuated Ang II-induced cognitive impairment by reducing BBB permeability [267, 268]. Therefore, induction of Ang II following TBI could weaken BBB permeability, and the use of ARBs may be be beneficial in blocking these effects and repairing a potentially leaky BBB beyond the immediate impact area. Cerebral edema is a common complication of TBI and contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality [269, 270]. Cerebral edema negatively impacts CNS tissues by its pressor effects within the restrictions of the cranium and reduction in cerebral perfusion pressure, further complicating ischemia. Increased intracranial pressure can progress to brain herniation and death [269]. Cerebral edema is mediated by several mechanisms after TBI, including disruption of the BBB and leakage of vascular fluid into the CNS, referred to as vasogenic edema [271]. Astrocytes play a major role in cytotoxic edema, which occurs when there is a failure of fluid regulation within cells, resulting in intracellular fluid shifts and CNS swelling [272, 273]. Edema in TBI can also be caused by compromised drainage of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) via the arachnoid granulations or the glymphatic system [270]. ARBs have demonstrated the ability to reduce cerebral edema in different disease models, although the exact mechanism is not fully understood. Candesartan and losartan decreased cerebral edema in ischemic rats [274] and cats [275] respectively. The detrimental effects of excessive AT1R activity on the BBB are well recognized [276]. Therefore, the beneficial effects of ARBs may be attributed to their inhibition of excessive Ang II/AT1R signaling in the cerebral microcirculation. ARBs may also act to alleviate cerebral edema through inhibition of aquaporin 4 (AQP4) expression on astrocytes. AQP4 expression increases after TBI; thus, it has become a potential therapeutic target for reducing cerebral edema [270]. Notably, in mice, deletion of AQP4 was associated with decreased cerebral edema formation following a controlled cortical impact in mice [277]. Further, ARBs reduced AQP4 expression in the peritoneum [278], suggesting that they may also decrease AQP4 expression in astrocytes after TBI, providing a mechanism through which they could reduce cerebral edema.

ARBs Reduce Fibrosis and Inhibit the Formation of Gliotic Scars after TBI

Neuroprotection can be achieved by reducing fibrosis and gliotic scar formation following TBI. Glial scarring, which occurs after penetrating brain injuries, can hinder recovery and contribute to TBI pathology [279]. Scar formation can serve as foci for abnormal neuronal firing resulting in post-traumatic epilepsy. Additionally, gliotic scar formation can impede axon regeneration when repair is possible [279, 280]. Astrocytes primarily mediate scar formation in the brain, but pericytes, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, and meningeal fibroblasts also contribute to this process [281–283]. The anti-fibrotic effects of many ARBs are likely due to their AT1R antagonism [284]. Indeed, genetic deletion of AT1R robustly reduces the astrogliosis following a controlled cortical impact injury in mice [201]. One possible mechanism through which ARBs may reduce fibrosis is by inhibition of signaling of the pro-fibrotic cytokine TGF-β [284, 285]. ARBs decrease TGF-β signaling [286, 287] and have been inaccurately referred to as TGF-β antagonists [288]. For instance, losartan can inhibit TGF-β signaling-driven extracellular matrix remodeling, preventing the development of recurrent seizures [286, 289]. Additionally, ARBs with partial PPARγ agonist activity have strong antifibrogenic effects [290]. Therefore, through multiple mechanisms, these ARBs could reduce CNS fibrosis and associated complications following TBI.

ARBs Enhance Neuronal Survival and Contribute to Improved Cognitive Outcomes in TBI

ARBs have been found to improve neuronal survival and cognitive outcomes in various studies. Ang II/AT1R signaling can harm neuronal viability, leading to cognitive decline [291]. In neuronal cell culture models, ARBs reduce excitotoxic neuronal death caused by excessive glutamate or nutrient deprivation. This is achieved through the reduction of caspase-3 activation and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway [292, 293]. Studies on embryonic rat neurons subjected to stretch injury demonstrated that pre-treatment with losartan reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine release and neuronal death mediated by Ang II/AT1R signaling [294]. Furthermore, valsartan increased dendritic spine density in rat hippocampal neurons and enhanced cell surface expression of AMPA receptor subunits. These molecular changes indicate a potential mechanism for improving learning and memory [295]. In animal models, ARBs have attenuated adverse neurobehavioral and cognitive effects associated with various insults and pathological conditions. In rodent models of ischemic insult, AT1R signaling exacerbated neuronal death through apoptotic pathways [296]. Blocking AT1Rs mitigated cognitive deficits following ischemic stroke in rats [296, 297]. Treatment with ARBs following moderate TBI reduced motor function deficits and spatiotemporal memory deficits in TBI mice [201]. In multiple rodent models of AD, administration of different ARBs resulted in improvements in spatial memory and recall in behavioral tests, such as the Morris Water Maze [291, 298]. Importantly, these cognitive improvements were independent of any effect on BP.

ARBs Provide Neuroprotection by Correcting Abnormal Metabolism in the Context of TBI

Major alterations in CNS metabolism occur after TBI [299]. Impairment of insulin signaling, glucose metabolism [300], glutamate metabolism [301], lipid metabolism [302], autophagy [303] and mitochondrial function [304] have been shown after TBI. Even mild TBI can result in metabolic disturbances, despite negative CT and MRI scans [305]. While the exact mechanisms behind these metabolic derangements are multifactorial, some evidence suggests that Ang II/AT1R signaling plays a role in these alterations. Therefore, ARBs may offer potential benefits for mitigating the metabolic consequences of TBI — however, direct evidence for RAS involvement in these processes after TBI is lacking. Ang II/AT1R signaling has been associated with increased ROS production and the induction of insulin resistance through various mechanisms [306]. ARBs reduced insulin resistance in various tissues and the vasculature, which could indirectly impact glucose uptake in the CNS [234, 307, 308]. Those ARBs targeting PPARγ could be particularly effective at tackling insulin resistance and the metabolic derangements following TBI. Telmisartan, the only ARB with AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity, could further enhance its beneficial effects on metabolism after TBI [309]. While the direct evidence for RAS involvement in these metabolic processes is limited, ARBs hold promise in addressing the metabolic consequences of TBI. By reducing insulin resistance, improving glucose uptake, and targeting mitochondrial dysfunction, ARBs, especially those with PPARγ activation or AMPK activity, could offer therapeutic benefits in restoring normal metabolism and promoting neuroprotection after TBI.

The Systemic Effects of ARBs Contribute to Their Neuroprotective Actions in TBI

TBI impacts the CNS and disrupts various systemic metabolic functions, which has a detrimental effect on neuronal survival and function [99]. For example, TBI affects liver metabolism [201, 310, 311], weight changes [312], non-CNS insulin resistance, [313], the cardiovascular system [314–316] and peripheral immune function [317, 318]. ARBs have the potential to modulate these systemic dysfunctions, mitigating their negative impacts on the CNS. Importantly, the doses of ARBs that demonstrate benefits in animal models of TBI are lower than those required to reduce BP, alleviating concerns about potential hypotension and further harm following ARB administration immediately after TBI [201]. By addressing the broader metabolic and physiological disturbances associated with TBI, ARBs possess systemic effects that could provide neuroprotective benefits.

Systemic inflammation is crucial in TBI pathophysiology’s early and chronic stages. Inflammation can persist for extended periods, in the brain and the periphery [319]. The impact of TBI on the peripheral immune response is complex. While proinflammatory states have been observed, TBI can also induce a relative suppression of the peripheral immune system, known as TBI-induced immune suppression [320]. While it is unclear whether peripheral immune suppression is beneficial or detrimental, it is associated with increased infection in hospitalized patients [320]. ARBs can potentially play a significant role in reducing systemic inflammation, benefiting both CNS and non-CNS tissues. Further investigation is required to examine how the RAS system is altered in crucial organs such as the liver, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and heart following TBI. Understanding these alterations will provide valuable insights into manipulating the peripheral RAS to regulate inflammation and achieve optimal effects.

ARB Use in the Clinical Management of TBI-Related Symptoms

The lack of therapeutics targeting TBI specifically, means that clinicians treat TBI patients with symptom-specific medications/therapies that have not necessarily been studied in the TBI population. Many clinical decisions to treat TBI-related symptoms require extrapolation from non-TBI data. ARBs and other RAS-related molecules have utility for treating a plethora of TBI-related symptoms that include depression, anxiety, PTSD, sleep disorders, headache, lethargy, diplopia/visual disturbance, attention disorders, cognitive decline, amnesia, and dizziness/balance disturbance [321].

Headache

Headache remains one of the most common symptoms after TBI, with headaches occurring in up to 30% of victims [322]. Various studies have suggested that ARBs, particularly candesartan, may be effective in the treatment of headache disorders. In a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial candesartan was better than placebo in the reduction of days with headache over a 12-week period [323]. In a second randomized trial both candesartan and propranolol achieved a statistically significant reduction of the number of days with moderate or severe headache [324] in comparison to placebo. In addition, multiple retrospective cohort studies have demonstrated candesartan’s beneficial effects for migraine prophylaxis [325]. Candesartan for migraine treatment receives a Level C recommendation by the American Academy of Neurology [326]. Telmisartan demonstrated a mild reduction in migraine symptoms vs placebo in certain patient populations [326, 327]. A small, more recent, study reported that 90% or patients, who were not responsive to calcium channel blockers, noted benefits from telmisartan – with significantly decreased frequency of headache days and headache severity [328]. Thus, telmisartan and candesartan both have utility in treatment of headache.

Mood/Anxiety/PTSD

Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are common conditions that can occur after a traumatic brain injury (TBI). In addition to pre-clinical data demonstrating the involvement of the RAS in regulating these conditions [329, 330], there is clinical evidence that suggest a role for RAS-based Mood/Anxiety/PTSD-therapy.

Cortisol is often increased during states of stress or fear. In a small study of patients with Type 2 Diabetes mellitus (DM), 3 months of daily candesartan significantly decreased cortisol response, and significantly improved interpersonal sensitivity and depression scores suggesting that candesartan impacts the HPA axis of patients with Type 2 DM and improves their affect [331]. Similarly, in the SCOPE trial (Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly) candesartan reduced anxiety scores and increased positive well-being scores, in addition to conferring reduced relative risk of strokes [332, 333]. Although retrospective studies suggested that ARBs would be beneficial in the treatment of PTSD symptoms [334], the LOSe-PTSD trial did not find a clinically significant difference between 10 week administration of losartan over placebo [335] in PTSD symptoms. It is tempting to speculate that there could be differences in the abilities of different ARBs to influence the CNS, particularly in light of the classification of candesartan as a BBB crossing ARB, but losartan as a non-BBB crossing drug [185]. However, the ability of candesartan, at the least, to have a beneficial effect in some studies on mood, anxiety and stress suggest that this would be an added bonus of efficacy in TBI patients.

Cognition

Cognitive slowing, or a decrease in processing speed, is a common and persistent symptom following brain injury. It can affect a wide range of cognitive functions, including attention, memory, and executive functioning. Currently, first line treatment for cognitive dysfunction remains cognitive rehabilitation and lifestyle modification. However, medication classes such as NMDA-receptor antagonist and stimulants have been studied and show modest benefits [336]. Though clinical evidence of cognitive benefits from ARBs is lacking with specific regard to TBI patients, data supports that ARBs can serve a neuroprotective role. For example, the 2020 Candesartan vs Lisinopril Effects on the Brain (CALIBREX) trial, compared cognitive function amongst 176 hypertensive adults treated with either candesartan or lisinopril. The study showed that 12-months of treatment with candesartan was associated with improvement in executive function and episodic memory compared with lisinopril [337]. Candesartan was also associated with decreased amyloid markers in CSF and in the hippocampal region on amyloid PET imaging, improved executive function and enhanced brain connectivity in multiple brain networks [338]. Additionally, a sub-analysis from the early SCOPE trial showed that patients taking candesartan had a diminished rate of cognitive decline compared to patients in the other arms of the trial, despite finding no overall difference in patient function on the MMSE test [339–341].

Retrospective studies have demonstrated that ARBs were associated with a lower risk of progression to dementia compared with both ACE inhibitors and other classes of anti-hypertension medications (β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics) [220]. Indeed, there are multiple clinical studies that show a benefit to ARBs with regard to cognitive decline in dementia [291, 342, 343]. Collectively, it appears that the benefits of ARBs on cognition are independent of their antihypertensive properties. However, the cognitive dysfunction secondary to dementia/aging is pathophysiologically distinct from TBI-related cognitive dysfunction, and thus it is difficult to extrapolate from these data to potential benefits of ARBs for cognitive improvement after TBI. Additional studies comparing cognition in hypertensive, brain-injured patients taking ARBs vs other anti-hypertensive agents would be of great value to the medical community.

Clinical Trials for the Acute Treatment of TBI Using ARBs

Candesartan is one arm of a new multi-arm, multi-stage adaptive Phase 2 trial for acute TBI, that is about to start recruiting patients (APT-TBI-01, NCT05826912). This trial will start treatment within 12 h of injury. Inclusion criteria include Glasgow Coma Scale between 9–15, CT positive lesion with acute trauma related neuroimaging abnormality, and serum Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) > 100 pg/ml. Patients will be randomized to treatment with either atorvastatin, minocycline, candesartan or placebo, and treatment will continue for 28 days. The primary outcome measure will be assessment of patients on the GOSE scale from 2 weeks to 3 months after injury. Secondary outcome measures include biomarkers (GFAP and Neurofilament), MRI imaging and cognitive and symptom assessments. This is the first clinical trial to assess efficacy of an ARB, and it will be assessed in comparison to atorvastatin, minocycline and placebo. Although the pre-clinical data for candesartan is somewhat limited in terms of models and time points, there are numerous mechanisms through which candesartan could have a beneficial effect after TBI and it will be exciting to see the outcome of this trial. However, it is sobering to recall the number of failed clinical trials for TBI including those with therapeutics with good pre-clinical data.

Drugs that Target RAS: AT2R Agonists

ACE/Ang II/AT2R signaling generally exhibits effects that counteract AT1R activation, benefiting brain function. Activation of AT2R leads to decreased BP, inhibition of inflammation and fibrosis, and reduced cell proliferation [109, 123]. In animal models of stroke [344] and TBI [345] AT2Rs are upregulated in the CNS and it is postulated that this upregulation could be therapeutic [123]. Two AT2R agonists, CGP42112A and Compound 21 (C21), possess neuroprotective properties in various paradigms. In ischemic stroke, C21 has been found to attenuate damage and deficits in rats [67]. Stimulation of AT2R by C21 following a stroke in rats was associated with increased levels of IL-10 and BDNF [124, 346, 347], both of which suppress pro-inflammatory microglial activation. These data suggest that the neuroprotective effects of C21 on AT2R may involve non-neuronal AT2R activation [348]. Furthermore, AT2R can signal through PPARγ, and blocking AT1R may increase the action of Ang II on AT2R, contributing to the PPARγ signaling observed with ARBs [349]. While the presence of the AT2R in astrocytes was initially debated, recent reports suggest that it is indeed present and necessary for functional MAS signaling [132]. There have been several studies explicitly investigating the role of AT2R in TBI with somewhat mixed results. Administration of the AT2R agonist CGP42112A provides neuroprotection, promotes neurogenesis, and increases expression of the neurotrophic factor BDNF after closed head injury in mice [135, 350]. The other AT2R agonist, C21, improved the neurological severity score, reduced proinflammatory cytokine expression in the cortex, and increased expression of IL-10 and phosphorylation of eNOS, after CCI in mice at 1 day post lesion [351]. However, a more recent report found no benefit of C21 in treating mice after CCI in terms of lesion volume, cytokine expression, or neurological severity score [345]. Further, they reported that there was no difference in the response to injury between wild type and AT2R knockout mice at 5 days post injury, suggesting that the endogenous AT2R did not play a major role in the early response to TBI [345]. There are differences in the injury model, treatment paradigm, read outs, and timing that could explain these differences in AT2R agonist efficacy. But these conflicting data do suggest that any AT2R dependent effect after TBI may not be as robust as that of inhibition of the AT1R through ARBs. The potential exists for AT2R signaling, and an AT2R agonist to have more efficacy in treating the later response to injury, but it’s possible that the lower expression of the AT2R in the adult brain may reduce the potential of AT2R agonists to be useful drugs for treating TBI.

Drugs that Target RAS: ACE Inhibitors

ACE inhibitors (ACEi) were the first class of drugs targeting the RAS approved by the FDA for the treatment of hypertension and are generally well tolerated [352]. By inhibiting the formation of Ang II, they reduce signaling through AT1R and AT2R. However, due to the wide range of potential ACE substrates, ACE inhibitors can have effects that are not directly related to their activity on the RAS [353]. In rodent models of ischemic stroke, ACE inhibitors have demonstrated neuroprotective benefits. For instance, the ACE inhibitor enalapril enhanced neurological activity, reduced cerebral infarct size, and decreased brain swelling following acute ischemic stroke in rats [354].

Enalapril exacerbated motor deficits following TBI in rats, suggesting that the benefits of ACE inhibition following ischemia may differ from those in TBI [209]. Long-term use of ACE inhibitors in patients with hypertension has been associated with a reduced risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and slower cognitive decline after diagnosis, indicating potential cognitive benefits of ACE inhibitors, particularly those that can penetrate the BBB such as captopril and perindopril [355–357]. However, it should be noted that ARBs have a more significant effect in reducing the progression of dementia compared to ACE inhibitors, and this difference could be partially attributed to ACE's ability to degrade β-amyloid [220, 358, 359].

Polymorphisms in the ACE gene can influence ACE expression levels. One well-known polymorphism is the Alu element insertion-deletion (I-D) polymorphism. Homozygous individuals for the deletion allele tend to have higher circulating and tissue ACE [360]. Interestingly, carriers of the deletion allele are at an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease and cognitive dementia [361–363]. ACE deletion carriers performed worse on various neuropsychological tests after moderate and severe TBI [364]. These findings suggest that increased ACE levels may have harmful effects on the pathophysiological progression of TBI. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that ACE inhibitors can increase the production of Ang-(1–7), which could benefit TBI recovery [365, 366]. Nevertheless, further in vivo studies are required to fully evaluate the potential value of ACE manipulation following TBI.

Drugs that Target RAS: Ang-(1–7) and MasR Agonists

In contrast to the largely detrimental effects of the classical ACE/Ang II/ AT1R axis of RAS, the counter regulatory ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR axis is beneficial to the CNS, particularly after injury, as it can reduce oxidative stress, increase vasodilation, provide neuroprotection and reduce inflammation [115, 367]. As inhibition of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis is beneficial for recovery from TBI, so too should stimulation of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR axis. There have been many studies on the favorable effects of stimulating this axis in stroke models [367, 368], and initial reports also indicate that this is true in mouse models of TBI [210, 369, 370]. Stimulation of MasR signaling can be achieved by activating ACE2, or by using a MasR agonist. Diminazene aceturate (DIZE) is an activator of ACE2: its administration increases Ang-(1–7) and decreases Ang II in systems where Ang II is present [371]. Ang-(1–7) is the endogenous MasR agonist, and has been administered directly in animal models, both through i.c.v. and s.q. routes to improve recovery after CNS injury [210, 372]. Other MasR agonists have been tested in clinical trials, and are safe in humans, but as yet, there is no FDA approved MasR agonist [373, 374].

The beneficial effects of manipulating the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR axis in rat stroke models has been clearly demonstrated and is a helpful indicator that this counter regulatory axis holds promise as a target for TBI therapeutics. Administration of the ACE2 activator, DIZE, following MCAO stroke in rats reduced the lesion size [375] and administration of the MasR antagonist, A779, attenuated this effect [375]. Transgenic mice with neuronal over-expression of ACE2 were protected against ischemic insult. Following MCAO, neuronal ACE2 over-expression reduced infarct volume and neurological deficits, and increased cerebral microvascular density and CBF in the peri-infarct area [376]. In spontaneously-hypertensive rats prone to hemorrhagic stroke, Ang-(1–7) administration reduced mortality, lesion volume and the stroke-induced increase of CD11b, IL-1α, iNOS, CXCR4 and IL-6 mRNA expression, in the infarcted tissue 24 h after insult [368]. In a different study, pre-treatment with either Ang-(1–7) or DIZE reduced lesion volume and neurological deficits in a rat model of MCAO, without affecting blood pressure or CBF, and these effects were removed upon cotreatment with A779 [147, 372].

The favorable effects of MasR activation for treating TBI rely on its ability to reduce inflammation, promote neuronal survival, protect the cerebrovasculature and enhance the BBB [198]. Many of these effects have been shown either in cell culture models, or in different animal models including in mice that are deficient in expression of the MasR. MasR KO mice exhibit an exacerbated systemic and cerebral inflammatory response when exposed to LPS, with significantly higher levels of IL-1β observed in both the brain and plasma compared to WT mice receiving LPS treatment [377]. Furthermore, MasR KO mice subjected to LPS treatment show increased leukocyte presence in the brain microvasculature compared to WT mice under the same conditions [377]. These findings emphasize the critical role of the MasR in maintaining proper neuroinflammatory function and suggest its involvement in the inflammatory cascade following TBI.