Abstract

Endonuclease V (deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease), the product of the nfi gene, has a specificity that encompasses DNAs containing dIMP, abasic sites, base mismatches, uracil, and even untreated single-stranded DNA. To determine its importance in DNA repair pathways, nfi insertion mutants and overproducers (strains bearing nfi plasmids) were constructed. The mutants displayed a twofold increase in spontaneous mutations for several markers and an increased sensitivity to killing by bleomycin and nitrofurantoin. An nfi mutation increased both cellular resistance to and mutability by nitrous acid. This agent should generate potential cleavage sites for the enzyme by deaminating dAMP and dCMP in DNA to dIMP and dUMP, respectively. Relative to that of a wild-type strain, an nfi mutant displayed a 12- to 1,000-fold increase in the frequency of nitrite-induced mutations to streptomycin resistance, which are known to occur in A · T base pairs. An nfi mutation also enhanced the lethality caused by a combined deficiency of exonuclease III and dUTPase, which has been attributed to unrepaired abasic sites. However, neither the deficiency nor the overproduction of endonuclease V affected the growth of the single-stranded DNA phages M13 or φX174 nor of Uracil-containing bacteriophage λ. These results suggest that endonuclease V has a significant role in the repair of deaminated deoxyadenosine (deoxyinosine) and abasic sites in DNA, but there was no evidence for its cleavage in vivo of single-stranded or uracil-containing DNA.

Endonuclease V (Endo V) of Escherichia coli cleaves near many types of lesions in DNA. It was originally described as preferring DNA that was treated with acid, alkali, OsO4, UV radiation, or 7-bromomethylbenz(a)anthracene, as well as uracil-containing DNA and even untreated single-stranded DNA (9, 12). The enzyme was recently found to be identical to deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease (13, 39), thereby increasing its repertoire to include dIMP residues, abasic sites, urea residues, single-base mismatches, pseudo-Y structures, and flap structures in DNA (36–39).

Endo V cleaves the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to deoxyinosine in DNA (37). In E. coli, there are three other known DNA repair pathways that are initiated by cleavage of a phosphodiester bond, as opposed to cleavage of a glycosylic bond (25). The UvrABC complex excises pyrimidine dimers and nucleotides containing bulky adducts. The MutSLH system removes regions containing mismatched bases. The VSP (very short patch) repair system repairs regions containing deaminated 5-methylcytosine. The broad specificity of Endo V is rivaled only by that of UvrABC, a large protein complex. By contrast, however, Endo V is a relatively small (25-kDa) monomeric protein (37).

In this work, we produce an nfi mutant and study some of its biological properties, with an emphasis on its response to DNA-damaging agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and their construction.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study are listed in Table 1. Generalized transduction was performed with phage P1 Δdam rev6 (29). Bacterial transformations with intact plasmids (5) and with linear DNA (26) were performed as previously described. After the introduction of the nfi-1::kan mutation into any strain, its genotype was confirmed by PCR (2) with the following two primers, which are complementary to the gene: ATGGATCTCGCGTCATTAC and CAGTTTACCTGAATTAGGG.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| AB1157c | hisG4 argE3 | 3 |

| AW804c | hemH1 zbb-3055::Tn10 | J. Adler 34 |

| BW285 | KL16d dut-1 | 6 |

| BW287 | KL16 dut-1 xthA3 | 6 |

| BW299 | KL16 xthA3 | Lab straine |

| BW313 | KL16 dut-1 ung-1 | Lab straine |

| BW853 | recD1903::mini-Tn10 | Lab strain |

| BW1034 | BW1138 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1160) × BW1138 |

| BW1067 | KL16 ung-153::kan | Lab straine |

| BW1138 | ung-153::kan end thyA gal his thi sup | 13 |

| BW1155 | CR63.1 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1160) × CR63.1 |

| BW1160 | BW853 nfi-1::cat | This study |

| BW1161 | AB1157 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1160) × AB1157 |

| BW1162 | AB1157 nfi-1::cat nfo-1::kan | P1(BW1160) × RPC500 |

| BW1163 | AB1157 nfi-1::cat Δ(xth-pncA)90 nfo-1::kan | P1(BW1160) × RPC501 |

| BW1166 | AB1157 nfi-1::cat Δ(xth-pncA)90 | P1(BW1160) × BW9109 |

| BW1171 | KL16 dut-1 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1161) × BW285 |

| BW1172 | KL16 dut-1 xthA3 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1161) × BW287 |

| BW1185 | KL16 nfi-1::cat | P1(BW1160) × KL16 |

| BW1187 | KL16 hemH1 zbb-3055::Tn10 | P1(AW804) × KL16 |

| BW1188 | KL16 nfi-1::cat hemH1 zbb-3055::Tn10 | P1(AW804) × BW1185 |

| BW1422 | KL16 nfi-1::cat xthA3 | P1(BW1161) × BW299 |

| BW9109 | AB1157 Δ(xth-pncA)90 | 33 |

| CR63.1 | phx supD | L. Grossman |

| KL16 | Hfr PO-45 spoT1 rel-1 thi-1 | 3 |

| RPC500 | AB1157 nfo-1::kan | 6 |

| RPC501 | AB1157 nfo-1::kan Δ(xth-pncA)90 | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | Cloning vector, Ampr | 35 |

| pGG42 | pUC19::nfi-yjaG | 13 |

| pGG48 | pUC19::nfi, AflIII deletion of pGG42 | This study |

Bacterial strains are derivatives of E. coli K-12λ−. Unless otherwise noted, the strains are F− and genetic descriptions are complete. kan and cat are inserted gene cassettes specifying resistance to kanamycin and to chloramphenicol, respectively.

P1 transductional crosses are described as follows: P1(donor) × recipient.

For a complete listing of markers, see the cited reference.

dut-1 transductants of KL16 may not contain the nearby spoT1 marker.

Pedigree available on request.

Nomenclature.

AUr, Valr, and Strr signify resistance to 6-azauracil, valine, and streptomycin, respectively.

Media.

Luria-Bertani (LB) media (20) were used for routine growth. Medium E (32), supplemented with glucose (2%) and thiamine (1 μg/ml), was employed as a minimal medium. Tetracycline was used at 15 μg/ml, ampicillin was used at 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol was used at 25 μg/ml, and amino acid supplements were used at 100 μg/ml. Strains carrying the dut-1 mutation were propagated at 25°C in LB medium supplemented with 1 mM thymidine (30). Light-sensitive hemH mutants were grown in foil-covered tubes.

Nitrite sensitivity and mutagenesis.

Saturated cultures were centrifuged, and the cells were washed with the original volume of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.6. One-milliliter samples (about 3 × 109 cells) were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.5 ml of either the sodium acetate buffer or a fresh solution of 40 mM NaNO2 in the same buffer. After incubation of the cells at 37°C for 6, 12, or 18 min, 5 ml of cold medium A (20) was added. A small sample (0.2 ml) was diluted and plated on LB agar for measurement of survival, which was ≥95% for the buffer-treated controls. The remainder was centrifuged, resuspended in 10 ml of LB medium, and grown overnight to saturation on a shaker at 37°C to permit expression of mutations. Before being plated on any minimal selective medium, the cells were washed by centrifugation and diluted in 10 mM MgSO4.

Mutation frequencies.

Spontaneous mutation frequencies were determined by means of a modified fluctuation test (16). For each strain, 10 2-ml cultures were grown to saturation from inocula of about 100 cells. For the scoring of prototrophic revertants and Valr mutants, the cells were washed (by centrifugation) in 10 mM MgSO4 and grown for 2 days at 37°C. AUr and Strr mutants were counted after 1 day. The following selective media were used: minimal medium containing 80 μg of l-valine per ml, minimal medium containing 40 μg of azauracil per ml plus 0.2% Casamino Acids (Difco) that had been treated with Norit (30), and LB medium containing 200 μg of streptomycin sulfate per ml.

Sensitivity tests.

The following were as previously described: gradient plate sensitivity tests (6), UV irradiation with a germicidal lamp (6), gamma irradiation in oxygenated cell suspensions (7), and H2O2 treatment (8). A calibrated 60Co source (Nuclear Reactor Laboratory, University of Michigan) was used for the gamma radiation. For exposure to visible light, saturated cultures were diluted in LB broth (with ampicillin as needed) and 10 ml containing about 104 cells was placed in a petri dish at a distance of 15 cm from two 15-W cool white fluorescent tubes (Westinghouse F15T8/CW). Exposure was at ambient temperature for 4 h. Controls were covered with aluminum foil.

Other methods.

Endo V assays (13); general cloning methods (2); and growth and titration of phages M13mp18 (2, 35), φX174 (28), and λc60 (2) were as described previously. Competent cells for transfection assays were prepared by treatment with CaCl2 (2). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (2). DNA concentrations were measured with Hoechst 33528 dye (4).

RESULTS

Construction of nfi-1 mutants.

Plasmid pGG13 contains a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene cassette inserted at nucleotide (nt) 443 of the 669-nt nfi gene. The insertion (nfi-1::cat) caused a ≥99% reduction in plasmid-specified Endo V activity without affecting the expression of the neighboring genes (13). The mutation was transferred to the chromosome by transformation of the recD strain BW853 with plasmid DNA that had been linearized by digestion with endonucleases ApaI and SmaI. A chloramphenicol-resistant, ampicillin-sensitive transformant (BW1160) was then used as a donor to transduce the nfi-1::cat mutation into other strains (Table 1).

The mutants had only a 40% reduction in single-strand-specific endonuclease activity as measured by the standard assay for Endo V. Because of this apparent interference by other DNases in crude extracts, PCR was used to confirm that each of the nfi-1::cat derivatives used in this study was indeed a mutant and that it did not also contain an intact copy of the gene. Wild-type and mutant copies might exist in tandem if the original mutant (BW1160), or a transductional recipient, contained a duplication of the nfi region. These merodiploids should appear among the transductants 100% of the time if the mutation is lethal or about 1% of the time if it is not (1). The PCR primers (see Materials and Methods) were chosen to bracket the insertion site. As predicted, the products from nfi+ DNAs were 0.68 kb whereas those from nfi-1::cat strains were 2.5 kb. Each strain yielded only one amplification product. Therefore, the nfi mutants are homozygous.

Construction of strains that overexpress Endo V.

The high-copy-number nfi+ plasmid pGG42 (Table 1) also contains yjaG, a gene of unknown function downstream of nfi. The plasmid was digested with endonuclease AflIII and religated, thereby deleting yjaG by removing a segment extending from the nfi-yjaG intergenic region to a point within the vector. The remaining cloned DNA extended from 433 nt upstream of nfi to 41 nt downstream of it. The resulting plasmid, pGG48, contained nfi as the only intact cloned gene and conferred a 46-fold increase in Endo V activity. Because the standard assay overestimates the activity in plasmid-free cells, the actual increase in Endo V may be over 100-fold.

Sensitivity to visible light.

nfi is 12 nt downstream from hemE, the gene for uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (23). Both genes are missing from an otherwise homologous region in Hemophilus influenzae. This physical and evolutionary association of the genes suggested a physiological relationship. hemE is involved in the biosynthesis of photosensitizing metabolites (34), and overproducers of HemE are sensitive to visible light (13), probably through the photochemical production of singlet oxygen or superoxide (22). Therefore, we hypothesized (13) that Endo V might have evolved to repair DNA damage from active oxygen species generated photochemically by protoporphyrin precursors. To test our hypothesis, we combined the nfi mutation with a hemH mutation (34) that causes photosensitivity due to accumulation of these metabolites. The strains were exposed to visible light at a level that reduced the survival of a hemH mutant (BW1187) to 18% without affecting that of the hemH+ parent (KL16). The addition of an nfi mutation to each strain produced no further detectable effect on survival. Moreover, this treatment did not produce a significant increase in mutations for resistance to azauracil, valine, or streptomycin (data not shown). Therefore, Endo V does not appear to be essential for DNA repair under these conditions.

Action on single-stranded DNA in vivo.

Endo V was originally described as a single-strand-specific DNase, and its standard assay was based on its ability to cleave the single-stranded DNA of a filamentous phage (12). However, in the cell, such activity might cause lethal damage to the replicating chromosome. To see if the enzyme manifests this activity in vivo, we tested the plating efficiencies of two phages containing single-stranded DNA: the filamentous phage M13 and the icosahedral phage φX174. M13mp18 (35) and φX174 phages were titrated on derivatives of strains KL16 and CR63.1, respectively. Similar results (±10%) were obtained for each of the following: the nfi+ parent, the corresponding nfi mutant, the nfi+ strain carrying the vector pUC19, and a strain carrying plasmid pGG48 (pUC19::nfi+). Because the infecting M13 DNA might carry some protective capsid protein into the cell, we measured the infectivity of the naked DNA as well. To compensate for variations in the levels of competence of the cell preparations used for these transfection assays, for each strain tested, the specific infectivity (PFU per nanogram) of the single-stranded viral DNA was divided by that obtained with the double-stranded plasmid, or replicative form, of M13. The resulting ratios were 42, 59, 39, and 39, respectively, for the four strains described above. Again, there was no marked difference between wild-type, mutant, and overproducing hosts. Therefore, we were unable to demonstrate any significant activity of the enzyme on single-stranded DNA in vivo.

Action on uracil-containing DNA in vivo.

Endo V also specifically cleaves uracil-containing double-stranded DNA. Bacteriophage λ that is grown on a dut-1 ung host contains uracil in place of some of its DNA thymine residues (10). The leaky (nonlethal) dut (dUTPase) mutation reduces the synthesis of TTP and permits the accumulation of dUTP, which is then incorporated into the DNA in place of some of the TTP. The ung (uracil-DNA glycosylase) mutation blocks the base-excision repair of this DNA, which would otherwise produce lethal double-strand breaks. Therefore, the uracil-containing λ phage has a high plating efficiency only on an ung mutant (10). To test if Endo V is active on uracil-containing λ DNA in vivo, we determined the effect of Endo V deficiency and overproduction on the plating efficiency of the λ phage (Table 2). The hosts were either ung+ or had a tight insertion mutation in ung. Whereas an ung mutation increased the survival of the λ phage 104-fold, an nfi mutation had little effect (experiment 1). In experiment 2 (Table 2), we used an ung mutation to eliminate the high background of bacteriophage restriction initiated by the glycosylase. However, even under these circumstances, neither the absence nor the overproduction of Endo V affected the plating efficiencies. Therefore, we were unable to demonstrate any significant activity of Endo V on uracil-containing phage DNA in vivo.

TABLE 2.

Effect of nfi gene dose on the growth of uracil-containing λ bacteriophages

| Expt | Host genotypea

|

Efficiency of platingb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Plasmid | ||

| 1 | Wild type | None | 1.0 × 10−4 |

| nfi-1 | None | 1.3 × 10−4 | |

| ung-153 | None | (1.0) | |

| 2 | Wild type | pUC19 | 8.6 × 10−5 |

| ung-153 | pUC19 | (1.0) | |

| ung-153 nfi-1 | pUC19 | 1.1 | |

| ung-153 | pUC19::nfi | 1.2 | |

The bacterial hosts were strains KL16, BW1067, BW1185, and BW1034 for experiment 1 and AB1157, BW1138, and BW1034 for experiment 2. Plasmid pUC19::nfi is pGG48.

Efficiency of plating is the ratio of the PFU to the normalized control value, which is enclosed in parenthesis. The uracil-containing phages used were λc60 that had been grown on BW313 (dut-1 ung-1).

Action at apyrimidinic sites in vivo.

Endo V has AP endonuclease activity (37), i.e., it cleaves near abasic (apyrimidinic or apurinic) sites in DNA. Abasic sites may be generated by the action of uracil-DNA glycosylase on the uracil residues in the DNA of a dut mutant. Because a tight dut mutation is lethal (11), we chose to use the dut-1 allele, which specifies a dUTPase that appears to be temperature sensitive in vivo (30). Even at 42°C, however, there is enough residual activity of the mutant enzyme to enable a high level of survival, unless the cells also contain a mutation affecting the repair of abasic sites. One such mutation is in xth, the gene for exonuclease III, the enzyme that possesses the major AP endonuclease activity in E. coli. Consequently, a dut-1 xth double mutant has a low level of survival at 42°C, whereas a dut-1, an xth, or a dut-1 xth ung triple mutant is almost fully viable (30). These findings had indicated that although unrepaired abasic sites (in the dut xth mutant) are lethal, the same number of single-strand breaks (in the dut mutant) or persistent uracil residues (in the dut xth ung mutant) are not. Previously, it was found that an nfo (endonuclease IV) mutation increased the lethality of the dut xth combination (6), indicating that endonuclease IV also has a significant role in the repair of apyrimidinic sites. We now tested our nfi mutation to see if it would have a similar effect (Table 3). Although the nfi-1 mutation did not significantly increase the temperature sensitivity of a dut-1 or an xth mutant, it produced a fourfold decrease in the survival of the double mutant, suggesting that Endo V contributes to the repair of apyrimidinic sites in vivo.

TABLE 3.

Effect of nfi on the repair of apyrimidinic sites in vivo

| Strain | Genotype | Relative survivala (42°C/30°C) |

|---|---|---|

| BW1422 | dut+ xthA3 nfi-1 | 9.7 (± 0.3) × 10−1 |

| BW285 | dut-1 | 4.3 (± 1.8) × 10−1 |

| BW1171 | dut-1 nfi-1 | 4.0 (± 1.4) × 10−1 |

| BW287 | dut-1 xthA3 | 9.4 (± 1.2) × 10−5 |

| BW1172 | dut-1 xthA3 nfi-1 | 2.3 (± 0.8) × 10−5 |

Arithmetic mean (± standard deviation) of results for three or more experiments. The standard deviations are presented only to indicate experimental variation; the data are not expected to be normally distributed.

Sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

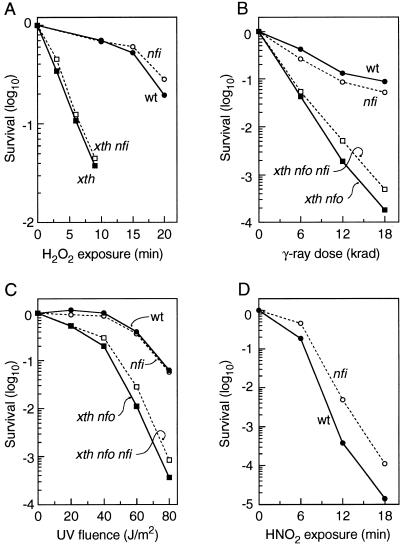

Endo V can recognize DNAs that have been damaged by a variety of agents. To assess the relative importance of the enzyme in some DNA repair pathways, we measured the sensitivity of nfi mutants to DNA-damaging compounds. Because individual DNases may be redundant in some pathways, we also tested the nfi mutation in combination with others. We asked, for example, if an nfi mutation enhances the known sensitivity of an xth (exonuclease III) mutant to H2O2 or of an nfo (endonuclease IV) mutant to mitomycin. The cells were exposed to the lethal agents either in liquid cultures (Fig. 1) or during growth on an agar plate containing a linear concentration gradient of the compound (Table 4). The nfi mutation specified an increased sensitivity to nitrofurantoin and to bleomycin (Table 4), both of which produce free radical damage to DNA. However, the nfi mutant did not appear to be significantly more sensitive to mitomycin, methyl methanesulfonate, or tert-butyl hydroperoxide under conditions in which either the nfo or xth mutant was more sensitive than the wild type (Table 4).

FIG. 1.

Survival curves. Cell suspensions were exposed to DNA-damaging agents at the following levels: H2O2, 10 mM; γ rays, 1 krad/min; UV light (peak at 254 nm), 1 W/m2; and HNO2, 40 mM. Dashed lines and open symbols are used for nfi mutants, and solid lines with filled symbols denote the corresponding nfi+ parents. The following sets of congenic strains were used for the experiments whose results are shown in panels A to C: AB1157 (wild type), BW1161 (nfi), BW9109 (xth), BW1166 (xth nfi), and BW1163 (xth nfo nfi). (D) The strains were KL16 (wild type) and BW1185 (nfi). Each datum point in the graphs in panels A, C, and D represents the average of results for two experiments in which each set of strains demonstrated the same order of sensitivities. (B) Each point is the result obtained with a separate oxygenated cell suspension; therefore, each set of vertical points represents the results of an independent experiment consisting of equally treated samples of four different strains. wt, wild type.

TABLE 4.

Gradient plate sensitivity tests

| Strain | Genotype | Growth (mm across gradient)a on agar containing:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrofurantoin (0 → 10 μg/ml) | Bleomycin (0 → 0.57 μg/ml) | Mitomycin (0 → 1.7 μg/ml) | MMS (0 → 0.83 μg/ml) | tert-Bu(OH)2 (0 → 0.33 μg/ml) | ||

| AB1157 | Wild type | 71, 72 | 80, 80 | 70, 70 | 70, 70 | 80, 80 |

| BW1161 | nfi | 50, 46 | 68, 65 | 70, 60 | 75, 75 | 80, 80 |

| BW9109 | Δxth | 44, 44 | 35, 50 | |||

| BW1166 | Δxth nfi | 40, 40 | 35, 50 | |||

| RPC500 | nfo | 42, 40 | 55, 55 | 35, 55 | 70, 70 | |

| BW1162 | nfo nfi | 38, 38 | 35, 35 | 35, 53 | 70, 65 | |

To minimize the effects of the gradient variation, both within and between plates, all the strains tested against a given agent were applied to a single plate as duplicate samples in a staggered array. The test for nitrofurantoin sensitivity was an exception in that two plates were used for each experiment, both of which contained AB1157 and BW1161 for reference. Each number is an average of results for duplicate samples. The results are presented in the following format: experiment 1, experiment 2. MMS, methyl methanesulfonate; tert-Bu(OH)2, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

An nfi mutation produced only slight effects, of questionable significance, on the resistance of various strains to H2O2, γ radiation, and UV radiation (Fig. 1). However, nfi mutants were found to have a modest increase in resistance to the lethal effect of nitrous acid (Fig. 1D). This difference was also consistently noted during other experiments (see below, under “Nitrite-induced mutation”). Nitrous acid causes deamination of DNA: cytosine is converted to uracil, adenine is converted to hypoxanthine, and guanine is converted to xanthine. The resulting deoxyuridine and deoxyinosine (hypoxanthine deoxyribonucleoside) in DNA are possible targets for Endo V. The poorer survival of nfi+ strains might be explained by the production of double-strand breaks by Endo V when both DNA strands contain deaminated bases in the same vicinity.

Frequencies of spontaneous mutation.

In vitro, Endo V cleaves DNA near bases that are mispaired, oxidized, or hydrolytically deaminated. All of these lesions can occur in the chromosome during normal growth in the absence of external mutagens. Spontaneous mutations were scored for several markers (Table 5). The his and arg mutations were ochre (TAA) codons that could revert by intragenic mutations only of A · T base pairs or by suppressor mutations that might occur at G · C base pairs as well. The Valr and AUr traits represent a broad spectrum of mutational changes. Mutations to Valr occur by loss of function of any of five genes involved in the transport of branched-chain amino acids or by alterations in either the structure or expression of any of six others involved in the feedback-inhibitable biosynthesis of isoleucine and valine (19). AUr results from loss of function of the upp (uracil phosphoribosyltransferase) gene (19). Relative frequencies of spontaneous mutation were analyzed by a modified fluctuation test that minimizes jackpot effects. An nfi mutant demonstrated about a twofold increase in the mutation frequencies for three of the traits tested (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Frequencies of spontaneous mutations

| Mutation | No. of mutants per samplea

|

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AB1157 (nfi+) | BW1161 (nfi-1::cat) | ||

| hisG4 → His+ | 5.2 (± 2.9) | 12.3 (± 5.5) | <0.01 |

| argE3 → Arg+ | 3.0 (± 2.1) | 5.9 (± 3.5) | 0.06 |

| AUr | 114 (± 45) | 215 (± 74) | <0.01 |

| Valr | 177 (± 58) | 125 (± 67) | >0.1 |

Mutation frequencies were determined by a modified fluctuation test (16) in which occasional jackpot results (greater than twice the mean) were discarded. Each value is the mean (± standard deviation) of results for 10 independent cultures. The sample size was 6 × 108 cells.

P, probability as determined by Student’s t test for unpaired values.

Nitrite-induced mutation.

An nfi+ strain and an nfi mutant strain were compared with respect to their levels of mutagenicity after treatment with nitrous acid (Table 6). The nfi mutant consistently displayed a greater survival than the wild type, confirming the results shown in Fig. 1. Nitrous acid produced about two to three times as many AUr and Valr mutants of the nfi mutant strain as of the wild type. The results were more striking for streptomycin resistance. The nitrite-treated nfi+ samples showed great variability, because their low frequency of Strr mutations and low rates of survival combined to produce occasional jackpot results. Nevertheless, the average frequency of nitrite-induced Strr mutants was 12-fold higher in the nfi mutant strain than in the wild type. The difference was about 1,000-fold if jackpot results were offset by comparing the median (rather than the mean) values (Table 6, footnote d).

TABLE 6.

Nitrous acid-induced mutagenesisa

| Treatment | Strain | Surviving fraction | Mutants (CFU/ml)c

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUr | Valr | Strr | |||

| Bufferb alone | KL16 (nfi+) | 1.0 | 5.8 (± 1.2) × 103 | 2.0 (± 0.4) × 101 | 5.3 (± 5.0) × 100 |

| BW1185 (nfi-1) | 1.0 | 6.9 (± 1.5) × 103 | 5.9 (± 2.9) × 101 | 3.2 (± 1.0) × 100 | |

| Buffer + HNO2 | KL16 (nfi+) | 5.5 (± 1.9) × 10−4 | 4.6 (± 2.1) × 105 | 9.6 (± 3.3) × 104 | 9.8 (± 20) × 101d |

| BW1185 (nfi-1) | 3.8 (± 0.4) × 10−3 | 1.3 (± 0.1) × 106 | 1.7 (± 0.7) × 105 | 1.2 (± 0.2) × 103 | |

Means (± standard deviations). With one exception (see footnote d), three culture samples were subjected to each treatment. The standard deviations are presented only to indicate experimental variation and do not imply that the data are normally distributed.

Buffer, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.6.

The concentrations of mutants were determined after outgrowth of the cultures to saturation (3 × 109 cells/ml).

Six culture samples were tested. The individual results ranged from 0 to 494 Strr mutants per ml, with a median value of 6.

DISCUSSION

The most striking effect of an Endo V deficiency is on the ability of the cell to repair nitrous acid-induced DNA damage. Compared to wild-type strains, nfi mutants displayed a greater frequency of nitrous acid-induced mutations but, paradoxically, the nfi mutants had an increased rate of survival. Apparently, at high doses of the agent, the strand breakage caused by the enzyme might be more lethal than the unrepaired mutagenic DNA lesions. As reviewed in reference 15, nitrous acid oxidatively deaminates the bases in DNA. Adenine is deaminated to hypoxanthine (in deoxyinosine), which pairs mainly with cytosine, resulting in A · T → G · C transitions. The deamination of cytosine to uracil results in G · C → A · T transitions. Xanthine produced from guanine can pair with thymine and has been blamed for G · C → A · T transitions; however, we do not know how well the DNA replication machinery of E. coli discriminates among alternative xanthine-containing base pairs. Of the traits tested in this study, the greatest increase in mutation frequency was that seen for Strr after nitrite exposure. All known mutations to Strr occur at one of two AAA (lysine) codons in the rpsL gene and are predominantly A · T → G · C transitions (31). Therefore, our result is consistent with the nfi mutant being defective in the repair of deaminated deoxadenosine (i.e., deoxyinosine) in DNA. Experiments are now in progress to determine the precise base pair changes induced by nitrous acid in the nfi mutant.

Considering the specificity of Endo V, the nature of its role in dealing with nitrous acid-induced lesions is not surprising but the magnitude of its role is, given that there are other enzymes in E. coli that can deal with dIMP in DNA. There is a hypoxanthine-DNA glycosylase activity (18) that is now known to be a property of 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase II, the AlkA protein (27). A putative second hypoxanthine-DNA glycosylase, with a reportedly different molecular weight, was also described (14); however, it may be the same protein because an alkA mutant had no detectable hypoxanthine glycosylase activity (27). In addition, the MutSLH mismatch repair system might be able to recognize the unstable hypoxanthine · thymine base pairs as a mismatch, but only in newly replicated DNA (21). Our results indicate that whereas these other systems can deal effectively with most spontaneous deamination mutations, they are not adequate to protect the cell from mutagenesis by nitrous acid.

Endo V also helps to protect the cell against killing by bleomycin and nitrofurantoin. Both agents bind to DNA and produce free-radical-mediated DNA damage, which has been better characterized for bleomycin (24) than for nitrofurantoin (17, 40). However, we do not know what specific lesions the enzyme recognizes. Experiments with dut mutants suggested that Endo V might make a significant contribution to the repair of apyrimidinic sites, even though there are several other E. coli endonucleases and endolyases that cleave at such sites (25). Although our apyrimidinic sites were generated by transient uracil incorporation, other experiments in this study indicated that Endo V had little effect on the DNA uracil itself.

Some of our negative results were of equal importance to the positive results. In the first studies of Endo V, it was uniquely characterized as specific for single-stranded DNA and for uracil-containing DNA. However, we were unable to demonstrate either activity in vivo. Its cleavage of single-stranded DNA, although it formed the basis for a standard assay (12), is admittedly so slow relative to its activity on dIMP-containing DNA that it was not detected at first in some studies (37). It is likely that its specificity for single-stranded DNA results from its ability to recognize base mismatches (38, 39); thus, it may cleave at unpaired or mispaired bases produced by transient hydrogen bonding of nearly homologous regions. (If this is true, the enzyme should have no activity on a homopolymer, a prediction that has not yet been tested.) Opportunities for such annealing would be extensive in a large single-stranded M13 or φX174 DNA molecule, upon which Endo V appeared to have no activity in vivo. Moreover, if the enzyme were to cleave single-stranded regions of the chromosome, such as those near replication forks, it would produce lethal double-strand breaks. Therefore, we presume that either single-stranded DNA is protected in the cell by proteins that bind to it or that the specificity of Endo V in vivo may be different from that in vitro, perhaps as a result, for example, of its being part of a repair complex.

Similarly, we were unable to demonstrate activity of Endo V on uracil-containing DNA. Unlike uracil-DNA glycosylase (10), Endo V requires a high level of uracil substitution in its DNA substrates (9), and we do not know to what extent this was achieved in our λ phages. Therefore, we can conclude only that the activity of Endo V, even in overproducers, is not enough to affect the viability of a uracil-containing λ phage under conditions in which an ung mutation does affect its viability. Studies in progress, of specific mutation rates (e.g., G · C → A · T), may provide a more sensitive determination of the relative roles of Endo V and uracil-DNA glycosylase in the repair of uracil in DNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Fred Kung for his capable technical assistance and Robert B. Blackburn of the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project for assistance with the γ-ray experiments.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant ES06047 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Computer facilities were provided in part by NIH grant MO1 RR00042.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson R P, Roth J R. Tandem genetic duplications in phage and bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:473–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.002353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann B J. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2460–2488. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesarone C F, Bolognesi C, Santi L. Improved microfluorometric DNA determination in biological material using 33258 Hoechst. Anal Biochem. 1979;100:188–197. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung C T, Niemela S L, Miller R H. One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2172–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham R P, Saporito S M, Spitzer S G, Weiss B. Endonuclease IV (nfo) mutant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1120–1127. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1120-1127.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham R P, Weiss B. Endonuclease III (nth) mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:474–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demple B, Halbrook J, Linn S. Escherichia coli xth mutants are hypersensitive to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1079–1082. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.2.1079-1082.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demple B, Linn S. On the recognition and cleavage mechanism of Escherichia coli endodeoxyribonuclease V, a possible DNA repair enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:2848–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan B K. Isolation of insertion, deletion, and nonsense mutations of the uracil-DNA glycosylase (ung) gene of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:689–695. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.689-695.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Hajj H H, Zhang H, Weiss B. Lethality of a dut (deoxyuridine triphosphatase) mutation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1069–1075. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1069-1075.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gates F T, Linn S. Endonuclease V of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1647–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo G, Ding Y, Weiss B. nfi, the gene for endonuclease V in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:310–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.310-316.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harosh I, Sperling J. Hypoxanthine-DNA glycosylase from Escherichia coli. Partial purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3328–3334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman Z, Henrikson E N, Hartman P E, Cebula T A. Molecular models that may account for nitrous acid mutagenesis in organisms containing double-stranded DNA. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1994;24:168–175. doi: 10.1002/em.2850240305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoess R H, Herman R K. Isolation and characterization of mutator strains of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1975;122:474–484. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.2.474-484.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins S T, Bennett P M. Effect of mutations in deoxyribonucleic acid repair pathways on the sensitivity of Escherichia coli K-12 strains to nitrofurantoin. J Bacteriol. 1976;125:1214–1216. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.3.1214-1216.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karran P, Lindahl T. Enzymatic excision of free hypoxanthine from polydeoxynucleotides and DNA containing deoxyinosine monophosphate residues. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5877–5879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRossa R A. Mutant selections linking physiology, inhibitors, and genotypes. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2527–2587. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modrich P, Lahue R. Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination, and cancer biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:101–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahigashi K, Nishimura K, Miyamoto K, Inokuchi H. Photosensitivity of a protoporphyrin-accumulating, light sensitive mutant (visA) of Escherichia coli K-12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10520–10524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura K, Nakayashiki T, Inokuchi H. Cloning and sequencing of the hemE gene encoding uroporphyrinogen III decarboxylase (UPD) from Escherichia coli K-12. Gene. 1993;133:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90233-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Povirk L F. DNA damage and mutagenesis by radiomimetic DNA-cleaving agents: bleomycin, neocarzinostatin and other enediynes. Mutat Res. 1996;355:71–89. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rupp W D. DNA repair mechanisms. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 2277–2294. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell C B, Thaler D S, Dahlquist F W. Chromosomal transformation of Escherichia coli recD strains with linearized plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2609–2613. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2609-2613.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saparbaev M, Laval J. Excision of hypoxanthine from DNA containing dIMP residues by the Escherichia coli, yeast, rat, and human alkylpurine DNA glycosylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5873–5877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinsheimer R L. Purification and properties of bacteriophage φX174. J Mol Biol. 1959;1:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sternberg N L, Maurer R. Bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:18–23. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor A F, Weiss B. Role of exonuclease III in the base-excision repair of uracil-containing DNA. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:351–357. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.351-357.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timms A R, Steingrimsdottir H, Lehmann A R, Bridges B A. Mutant sequences in the rpsL gene of Escherichia coli B/r: mechanistic implications for spontaneous and ultraviolet light mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:89–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00299141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogel H J, Bonner D M. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White B J, Hochhauser S J, Cintrón N M, Weiss B. Genetic mapping of xthA, the structural gene for exonuclease III in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:1082–1088. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.3.1082-1088.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang H, Inokuchi H, Adler J. Phototaxis away from blue light by an Escherichia coli mutant accumulating protoporhyrin IX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao M, Hatahet Z, Melamede R J, Kow Y W. Deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease, a novel deoxyinosine-specific endonuclease from Escherichia coli. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;726:315–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao M, Hatahet Z, Melamede R J, Kow Y W. Purification and characterization of a novel deoxyinosine-specific enzyme, deoxyinosine 3′ endonuclease, from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16260–16268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao M, Kow Y W. Strand-specific cleavage of mismatch-containing DNA by deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31390–31396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao M, Kow Y W. Cleavage of insertion/deletion mismatches, flap and pseudo-Y DNA structures by deoxyinosine 3′-endonuclease from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30672–30676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Youngman R J, Osswald W F, Elstner E F. Mechanisms of oxygen activation by nitrofurantoin and relevance to its toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:3723–3729. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]