Abstract

Social phobia (SP) refers to excessive anxiety about social interactions. College students, with their exposure to academic, familial, and job-related pressures, are an ideal population for early screening and intervention of social phobia. Additionally, COVID-19 prevention measures including keeping social distance may further impact social phobia. This study aims to investigate the influencing factors of social phobia among Chinese college students and to tentatively explore the impact of COVID-19 prevention measures on social phobia. Respondents were recruited through Chinese Internet social platforms for an online survey. College students’ social phobia scores in pre- and early-COVID-19 periods were measured using Peters' short form of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale (SIAS-6/SPS-6). Demographic information, family information, social relations, self-evaluation, and subjective feelings regarding the impact of COVID-19 preventive measures on social phobia were collected. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors. A total of 1859 valid questionnaires were collected, revealing that the social phobia scores increased from 12.3 ± 11.9 to 13.4 ± 11.9 between pre- and early-COVID-19 periods, with an increase of 1.0 ± 6.4 (p < 0.001). Low GPA rank, mobile phone dependence, distant family relationships, indulgent parents, childhood adversity, and childhood bullying were risk factors for social phobia among Chinese college students. Female gender, being a senior university student or postgraduate, satisfaction with physical appearance, self-reported good mental health and high level of interpersonal trust were protective factors for social phobia. Although most respondents believed that COVID-19 prevention measures (e.g., mask wearing and social distancing rules) reduced their social phobia, these measures were not significantly associated with social phobia levels in the multivariable analyses. In conclusion, Chinese college students’ social phobia was widely influenced by diverse factors and warrants increased attention, with early intervention aimed at high-risk individuals being crucial for their mental health. Additional research is necessary to understand the impact of COVID-19 preventive measures on social phobia among college students.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Risk factors, Psychology

Introduction

Social phobia (SP) refers to excessive fear of social situations, fear of attracting attention to oneself in front of others or the public, abnormal trepidation, anxiety, and avoidance of new circumstances or unfamiliar objects1,2. SP is a negative psychological emotion that begins in adolescence and is most common in adolescents3. It is often accompanied by excessive discomfort, negative reflections, and somatic symptoms (such as blushing, trembling, and sweating that happen before, during, and after social activities), seriously affecting the study and everyday life of young people4. Given the early onset and persistence of social phobia5, college students are an ideal group for early screening of social phobia as they are new to society and are under pressure from academics, family, job hunting, and courtship6. By focusing on the social phobia of college students and the factors influencing them, we can identify groups that are vulnerable to social phobia and provide early intervention and care.

According to previous studies, the factors affecting college students’ social phobia could be divided into three aspects of individual, family, and social relations. Individual factors included physiological reasons, nationality, educational level, childhood adverse experiences, personality, self-efficacy, self-esteem, academic performance, and satisfaction with their appearance7–10. Family factors included monthly family income, parenting style, family structure, family relationship, only children or not, rural or urban residence7,8,11–13. Social relation factors included school environment, whether they have served as student leaders, social support system7,8,11–16. Developed countries have carried out extensive research on the influencing factors of young people's social phobia17,18. However, the research on social phobia in China occurred late such a concept was not proposed until 199319. Previous studies on the influencing factors of Chinese college students' social phobia often led to unstable or even contradictory results7 because the objects were collected from single regions11,13, colleges with specific majors8,12, or the sample size was relatively small20,21. Many studies focused on a certain province or city, and nationwide studies were rare7,8,11–13.

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, governments introduced various policies to prevent and control the spread of the pandemic. World Health Organization (WHO) advocated that people wear masks and maintain a “one-meter line” social distance, and schools adopted online teaching, questioning, and tests instead of offline mode during the pandemic22,23. As of 2022, there have been three rounds of COVID-19 outbreaks in China, namely from January to March 2020, from March to May 2022, and at the end of 202224. During the period from April 2020 to August 2021 after the first-round outbreak (hereinafter referred to as the early-COVID-19 period), Chinese colleges implemented many precautionary measures against the COVID-19 pandemic, such as setting barriers in the canteen, appealing to keeping social distance and conducting online teaching25. These measures reduced college students' social contact and may have an impact on their social phobia. Studies in developed countries showed that COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control measures may, on the one hand, alleviate the social phobia of college students in the short term by removing the social stimuli that originally triggered their fears (e.g., shared meals, and club activities); but on the other hand, they may be at risk of increased social phobia symptoms when they resume normal social interaction after the outbreak26–28. However, the impact of COVID-19 prevention and control measures on the social phobia of Chinese college students is still unclear.

This study aims to investigate the influencing factors of social phobia among Chinese college students and to tentatively explore the impact of COVID-19 prevention measures on social phobia in early-COVID-19 period.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted this cross-sectional survey from August 13 to 23, 2021, by inviting Chinese college students to participate in a web-based survey through the Wenjuanxing platform. We published recruitment notices on Chinese Internet social platforms (WeChat, QQ, and Baidu Post Bar). Risk control measures were taken during the data collection process, for example, the questionnaire was anonymous, all information was kept strictly confidential, and respondents had the right to refuse to answer. Each respondent who completed and submitted the questionnaire was paid 2 China Yuan as a subsidy. Inclusion criteria: Chinese college students (including junior college students, undergraduates, and postgraduates). Out of ethical considerations and control of potential confounding factors, we have developed exclusion criteria: (1) Under 18 or over 35 years old; (2) Pregnant or lactating women; (3) Suffering from serious physical or mental diseases and not yet recovered; (4) Taking psychotropic drugs in recent 2 weeks.

Measurement of social phobia

We used the Peters short form of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale (SIAS-6/SPS-6)29 to measure the social phobia score of college students in pre- and early-COVID-19 periods. Many studies from different populations and countries have demonstrated the satisfactory reliability and validity of this scale. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients of the SIAS-6 and SPS-6 in the Chinese university sample, were 0.742 and 0.868, respectively30–32. Each of the 12 items used a 5-point Likert scale response. A summative score was calculated from these 12 items (0–48 points), whereby a higher score reflects a higher degree of social phobia.

Respondents were asked to fill in SIAS-6/SPS-6 according to their status in early-COVID-19 period (August 2021, current date) and pre-COVID-19 period (before December 2019, retrospectively collected) respectively, representing their self-reported early- and pre-COVID-19 social phobia scores, the latter of which was scored retrospectively. Retrospective self-reported change in social phobia was assessed based on the difference between the early- and pre-COVID-19 social phobia scores. A reduction in social phobia score was defined as a difference less than 0, an unchanged score was defined as a difference equal to 0, and an increase was defined as a difference greater than 0.

Questionnaire content

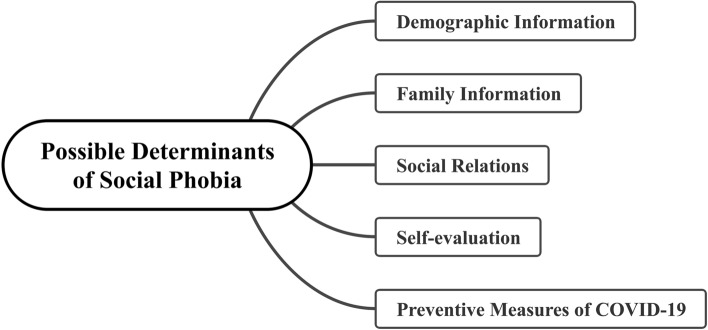

The questionnaire included two SIAS-6/SPS-6 scales (for pre- and early-COVID-19 periods) and five types of factors that may affect students’ social phobia status (Fig. 1), including demographic information, family information, social relations, self-evaluation, and subjective feelings about the impact of COVID-19’s preventive measures on social phobia.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of possible influencing factors of social phobia.

Demographic information included gender, nationality, height, weight, registered residence, region (urban or rural), college type (according to China's “985 Project”33, universities were classified into 985 universities and non-985 universities, and the former was a group of Chinese high-level universities), grade, major, grade point average (GPA) ranking, and weekly exercise frequency (only consider a physical activity or exercise ≥ 1 h). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and divided into underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24.0), overweight (24.0 ≤ BMI < 28.0), and obesity (BMI ≥ 28.0) based on the Chinese population standard. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China’s economic zone division34, a sum of 31 provinces, autonomous zones, and municipalities in China were divided into eastern, central, western, and northeast economic zones. The economic level of Macao and Taiwan was adjacent to the Eastern zone, thus incorporated into the Eastern zone for analysis. Family information included a family's monthly income per capita, family structure, parenting style, closeness of family's relationship, the number of siblings, and childhood adversity experience. Social relations included whether being in love, the number of love affairs, whether having been participated in student organizations, and childhood bullying experience. Self-evaluation included anxious feelings when one has yet to check the message or turn on the mobile phone for a period (reflecting the degree of mobile phone dependence), satisfaction of self-appearance, self-assessment of mental health, and degree of trust in strangers. Subjective feelings about the impact of COVID-19 preventive measures on social phobia included respondents' belief about wearing a mask, setting a baffle on the canteen dining table, keeping a one-meter social distance, vaccination against COVID-19, online presentation, or online asking or answering questions could alleviate or aggravate the social phobia degree.

According to data provided by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China and the National Bureau of Statistics, the cumulative prevalence of COVID-19 in Chinese mainland was only 6.68/100,000 (94,260/1,411,778,724) as of August 12th, 202135,36, when almost no respondents were diagnosed with COVID-19. Therefore, we did not investigate whether the respondent was diagnosed with COVID-19.

Quality control methods

Quality control procedures were carried out collaboratively by two data managers, and a data checker verified the correctness of the quality control process. Specifically, data quality checks restricted responses to one occurrence per social media platform, electronic device, and Internet Protocol (IP) address. Furthermore, respondents were excluded from the database if the questionnaires showed: (1) Logic errors, (2) identical answers, (3) completion time of less than 90 s, (4) height below 150 cm, and (5) weight under 30 kg. Respondents with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 35 kg/m2 were considered as an error, and this was modified by dividing weight by 2. This adjustment was made to account for the use of jin as a unit of measurement for weight in China (twice the value of kilograms). Although the questionnaire was labeled in kilograms, some respondents might still habitually provide their weight in jin.

Ethics statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Peking University Medical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-21054, June 10, 2021).

Statistical analyses

Both the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Shapiro–Wilk test showed that college students’ SIAS-6/SPS-6 scores were not normally distributed (P < 0.001), so we used median (P50) and quartile (P25, P75) to describe their distribution. A multivariable binary logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors of college students’ social phobia. Since there was no threshold for social phobia diagnosis in SIAS-6/SPS-6, we divided the current social phobia score into 2 groups of low score (0–10, n = 956) and high score (11–48, n = 903) according to the median as the outcome variable for best statistical power. Independent variables included demographic information, family information, social relations, and self-evaluation. We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select variables by stepwise regression. McFadden’s R2 was used to evaluate the model's goodness of fit (generally > 0.2 could be considered to have a satisfied goodness of fit). Generalized variance inflation factors (GVIF) were used to evaluate the existence of multicollinearity (> 5 indicated multicollinearity). Subgroup analyses were conducted based on gender, region, and whether the respondent was the only child. Sensitivity analyses were conducted from two perspectives: variable selection methods and outcome variable classification criteria. The following 3 methods were used to select variables based on AIC: (1) backward regression; (2) forward regression; and (3) stepwise regression first, followed by the optimal subset regression. (Optimal subset regression was not used directly because it was limited by computational complexity and could only calculate all possible subsets of up to 15 variables. However, this study had up to 24 variables, therefore, the stepwise regression was preliminarily used to reduce the number of variables included, and then the optimal subset regression was used to obtain the optimal regression model.) In addition, the current social phobia scores were divided into ordinal variables according to tertiles (P33, P67) and quartiles (P25, P50, P75), respectively, as outcome indicators for ordinal logistic regression in sensitivity analyses to reflect the robustness of regression results.

A multivariable three-level ordinal logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors of retrospective self-reported change in college students’ social phobia between early- and pre-COVID-19 periods. The outcome was an ordinal three-level variable: social phobia scale score increased (difference > 0), unchanged (difference = 0), and reduced (difference < 0), as defined previously. The subjective feelings about the impact of COVID-19’s preventive measures on social phobia were considered independent variables. Demographic information, family information, social relations, and self-evaluation were used as covariates. We also used AIC to select variables by stepwise regression.

Microsoft Excel was used to establish the database. R 4.1.2 (R Statistics, Vienna, Austria) was used for statistical analyses, and a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was viewed as statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

A sum of 2469 questionnaires was collected, of which 1859 were valid, with an effective rate of 75.29%. In the study sample, just over half were males and nearly all the students were of Han ethnicity, about two-thirds were from urban areas. 49.0% were from the eastern zone, 25.9% were from the central zone, 20.5% were from the western zone, and 4.6% were from the northeast zone. The sample population composition ratio in this study was close to the college-age young adults in the 2020 Population Census of China in terms of gender, ethnicity, and economic zone37, therefore, it had a certain representativeness. Detailed characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics (n = 1859). a1 CNY = 0.1543 USD on August 14, 2021. BMI body mass index, GPA grade point average, CNY China Yuan, USD United States dollar.

| Characteristic | Total n (%) |

Social phobia score median (P25–P75) |

Characteristic | Total n (%) |

Social phobia score median (P25–P75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | Childhood bullying experience | ||||

| Gender | Never | 756 (40.7) | 5.0 (1.0–12.0) | ||

| Male | 1002 (53.9) | 12.0 (4.0–24.8) | Seldom | 709 (38.1) | 10 (4–20) |

| Female | 857 (46.1) | 8.0 (3.0–18.0) | Sometimes | 326 (17.5) | 23.5 (14.0–31.0) |

| Nation | Often | 68 (3.7) | 32.5 (21.0–38.5) | ||

| Ethnic Han | 1763 (94.8) | 10.0 (3.0–22.0) | Family Information | ||

| Ethnic minorities | 96 (5.2) | 9.5 (2.8–16.0) | Monthly household income per capitaa | ||

| Economic zone | < 2000 CNY | 108 (5.8) | 12.0 (5.0–23.2) | ||

| Eastern | 911 (49.0) | 10.0 (3.0–22.0) | (< 309 USD) | ||

| Central | 481 (25.9) | 11.0 (4.0–22.0) | 2000–5000 CNY | 527 (28.3) | 12.0 (4.0–22.0) |

| Western | 382 (20.5) | 11.0 (4.0–21.0) | (309–772 USD) | ||

| Northeast | 85 (4.6) | 6.0 (2.0–12.0) | 5000–10,000 CNY | 720 (38.7) | 10.0 (3.0–21.0) |

| Region | (772–1543 USD) | ||||

| Urban | 1257 (67.6) | 10.0 (3.0–22.0) | > 10,000 CNY | 504 (27.1) | 7.50 (2.0–20.0) |

| Rural | 602 (32.4) | 11.0 (4.0–21.0) | (> 1543 USD) | ||

| College type | Family structure | ||||

| Non-985 | 1307 (70.3) | 11.0 (3.0–23.0) | Two-parents family | 1698 (91.3) | 9.0 (3.0–20.8) |

| 985 | 552 (29.7) | 9.0 (3.0–18.2) | Single parent family | 104 (5.6) | 19.0 (8.8–28.0) |

| Grade | Restructured family | 37 (2.0) | 23.0 (14.0–33.0) | ||

| 1 | 229 (12.3) | 12.0 (5.0–23.0) | Others | 20 (1.1) | 15.0 (8.0–28.2) |

| 2 | 600 (32.3) | 11.0 (3.0–24.0) | Parenting style | ||

| 3 | 688 (37.0) | 10.0 (3.0–21.0) | Authoritative | 1293 (69.6) | 8.0 (3.0–20.0) |

| 4 or 5 | 277 (14.9) | 8.0 (3.0–19.0) | Authoritarian | 233 (12.5) | 16.0 (7.0–26.0) |

| Postgraduate | 65 (3.5) | 6.0 (2.0–12.0) | Neglectful | 295 (15.9) | 12.0 (5.0–23.5) |

| Major | Permissive | 38 (2.0) | 16.0 (7.2–28.8) | ||

| Literature or history | 345 (18.6) | 10.0 (3.0–21.0) | Closeness of family relationship | ||

| Science or technology | 911 (49.0) | 11.0 (3.0–23.0) | Close | 1405 (75.6) | 8.0 (3.0–19.0) |

| Medicine | 342 (18.4) | 10.0 (4.0–20.0) | General | 411 (22.1) | 16.0 (8.0–27.0) |

| Economy or management | 177 (9.5) | 9.0 (3.0–17.0) | Alienated | 43 (2.3) | 20.0 (12.5–25.0) |

| Others | 84 (4.5) | 14.0 (3.0–22.2) | Number of siblings | ||

| GPA ranking | 0 | 873 (47.0) | 8.0 (3.0–19.0) | ||

| Top 20% | 323 (17.4) | 8.0 (3.0–16.0) | 1 | 676 (36.4) | 11.0 (4.0–21.0) |

| 20–40% | 731 (39.3) | 10.0 (3.0–21.0) | 2 | 253 (13.6) | 16.0 (7.0–28.0) |

| 40–60% | 573 (30.8) | 11.0 (4.0–23.0) | ≥ 3 | 57 (3.1) | 11.0 (4.0–22.0) |

| 60–80% | 179 (9.6) | 10.0 (3.0–23.5) | Childhood adversity experience | ||

| After 80% | 53 (2.9) | 17.0 (8.0–25.0) | Never | 756 (40.7) | 5.0 (1.0–12.0) |

| BMI | Seldom | 709 (38.1) | 10 (4–20) | ||

| Normal | 1198 (64.4) | 10.0 (3.0–22.0) | Sometimes | 326 (17.5) | 23.5 (14.0–31.0) |

| Overweight | 193 (10.4) | 9.0 (3.0–20.0) | Often | 68 (3.7) | 32.5 (21.0–38.5) |

| Obesity | 57 (3.1) | 13.0 (6.0–28.0) | Self-evaluation | ||

| Underweight | 411 (22.1) | 10.0 (4.0–21.0) | Mobile phone dependence | ||

| Exercise frequency | No | 462 (24.9) | 4.0 (0.0–8.0) | ||

| < Once a week | 438 (23.6) | 14.0 (6.0–23.0) | General | 863 (46.4) | 10.0 (4.0–21.0) |

| 1–2 times a week | 882 (47.4) | 12.0 (4.0–24.0) | Yes | 534 (28.7) | 18.0 (10.0–29.0) |

| ≥ 3 times a week | 539 (29.0) | 6.0 (2.0–14.0) | Appearance satisfaction | ||

| Social relations | Not very satisfied | 317 (17.1) | 17.0 (9.0–26.0) | ||

| Being in love now | Moderately satisfied | 858 (46.2) | 11.0 (5.0–21.0) | ||

| No | 958 (51.5) | 11.0 (4.0–22.0) | Quite satisfied | 684 (36.8) | 6.0 (2.0–17.0) |

| Yes | 901 (48.5) | 9.0 (3.0–21.0) | Mental health self-assessment | ||

| Number of love affairs | Not very healthy | 116 (6.2) | 21.0 (12.0–30.0) | ||

| 0 | 445 (23.9) | 11.0 (4.0–21.0) | Moderately healthy | 626 (33.7) | 17.0 (9.0–26.0) |

| 1–2 | 1233 (66.3) | 10.0 (3.0–22.0) | Quite healthy | 1117 (60.1) | 6.0 (2.0–15.0) |

| ≥ 3 | 181 (9.7) | 9.0 (3.0–18.0) | Degree of trust in strangers | ||

| Student organizations participation | Not very trust | 585 (31.5) | 12.0 (5.0–21.0) | ||

| Ever | 1373 (73.9) | 9.0 (3.0–21.0) | Moderately trust | 845 (45.5) | 9.0 (3.0–21.0) |

| Never | 486 (26.1) | 13.0 (5.0–24.0) | Quite trust | 429 (23.1) | 8.0 (3.0–25.0) |

Influencing factors of college students’ social phobia

The GVIF of all variables in the main analysis, subgroup analyses, and sensitivity analyses were less than 1.66, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. McFadden’s R2 of all models in the main analysis and subgroup analyses were greater than 0.27, reflecting a satisfied goodness of fit.

Multivariable logistic regression results showed that risk factors for social phobia were: lower GPA (OR: 1.40–2.36, as compared with those in the top quintile), higher frequencies of bullying experience (OR: 1.31–3.44, vs non-bullied students), permissive parents (OR = 2.82, vs authoritative parents), general family relationships (OR = 1.35, vs close family relationships), having 1 or 2 siblings (OR: 1.35–2.18, vs no sibling), higher frequencies of childhood adversity (OR: 1.63–11.35, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 2.32–5.12).

Protective factors for social phobia were female gender (OR = 0.63), being a postgraduate or grade 4/5 student (OR: 0.38–0.60, vs grade 1), being quite satisfied with their appearance (OR = 0.64, vs not very satisfied), self-perceived mentally quite healthy (OR = 0.37, vs not very healthy), and moderately trust in strangers (OR = 0.72, vs not very trust) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression of influencing factors for social phobia (main analysis). The outcome variable was divided by median into 2 groups of low score (0–10, n = 956) and high score (11–48, n = 903). McFadden’s R2 = 0.285. GVIF for all variables is less than 1.58. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, GPA grade point average.

| Factor | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | ||

| Gender (female vs male) | 0.63 (0.50–0.79) | < 0.001 |

| Region (rural vs urban) | 0.82 (0.63–1.07) | 0.136 |

| Grade (vs 1) | ||

| 2 | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | 0.322 |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.54–1.14) | 0.206 |

| 4 or 5 | 0.60 (0.39–0.94) | 0.025 |

| Postgraduate | 0.38 (0.19–0.78) | 0.008 |

| GPA ranking (vs top 20%) | ||

| 20–40% | 1.40 (1.00–1.96) | 0.049 |

| 40–60% | 1.47 (1.04–2.09) | 0.030 |

| 60–80% | 1.04 (0.65–1.68) | 0.867 |

| After 80% | 2.36 (1.07–5.21) | 0.033 |

| Exercise frequency (vs < once a week) | ||

| 1–2 times a week | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) | 0.397 |

| ≥ 3 times a week | 0.82 (0.59–1.15) | 0.246 |

| Social relations | ||

| Never participate in student organizations (vs ever) | 1.26 (0.97–1.66) | 0.089 |

| Childhood bullying experience (vs never) | ||

| Seldom | 1.31 (1.00–1.71) | 0.047 |

| Sometimes | 2.91 (1.95–4.33) | < 0.001 |

| Often | 3.44 (1.36–8.65) | 0.009 |

| Family Information | ||

| Parenting style (vs authoritative) | ||

| Authoritarian | 1.08 (0.75–1.56) | 0.691 |

| Neglectful | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) | 0.511 |

| Permissive | 2.82 (1.21–6.60) | 0.017 |

| Closeness of family relationship (vs close) | ||

| General | 1.35 (1.01–1.82) | 0.044 |

| Alienated | 1.26 (0.49–3.21) | 0.627 |

| Number of siblings (vs 0) | ||

| 1 | 1.35 (1.04–1.75) | 0.027 |

| 2 | 2.18 (1.52–3.14) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.08 (0.55–2.14) | 0.814 |

| Childhood adversity experience (vs never) | ||

| Seldom | 1.63 (1.23–2.14) | < 0.001 |

| Sometimes | 2.64 (1.84–3.80) | < 0.001 |

| Often | 11.35 (4.47–28.79) | < 0.001 |

| Self-evaluation | ||

| Mobile phone dependence (vs no) | ||

| General | 2.32 (1.72–3.13) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 5.12 (3.63–7.22) | < 0.001 |

| Appearance satisfaction (vs not very satisfied) | ||

| Moderately satisfied | 0.83 (0.59–1.17) | 0.293 |

| Quite satisfied | 0.64 (0.43–0.93) | 0.021 |

| Mental health self-assessment (vs not very healthy) | ||

| Moderately healthy | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.348 |

| Quite healthy | 0.37 (0.21–0.66) | < 0.001 |

| Degree of trust in strangers (vs not very trust) | ||

| Moderately trust | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | 0.016 |

| Quite trust | 0.99 (0.71–1.36) | 0.929 |

Subgroup analyses by gender, region, and whether the respondent was the only child

The influencing factors of Chinese students’ social phobia were diverse by gender, region, and whether he/she was the only child.

For male students, risk factors for social phobia were sometimes or often being bullied (OR: 3.52–4.56, vs never been bullied), middle-high household income (OR = 2.48, vs low household income), general family relationships (OR = 1.68, vs close family relationships), having 1 or 2 siblings (OR: 1.43–2.55, vs no sibling), higher frequencies of childhood adversity (OR: 1.59–8.37, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 2.27–4.10); protective factors were being from northeast of China (OR = 0.27, vs eastern China), being a postgraduate student (OR = 0.22, vs grade 1), and being quite satisfied with their appearance (OR = 0.50, vs not very satisfied).

For female students, risk factors for social phobia were sometimes being bullied (OR = 2.44, vs never been bullied), having 2 siblings (OR = 1.84, vs no sibling), higher frequencies of childhood adversity (OR: 1.78–21.46, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 2.61–7.56); protective factor was self-perceived mentally quite healthy (OR = 0.17, vs not very healthy) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of the influencing factors of social phobia between males and females (subgroup analysis). aMcFadden's R2 = 0.308. GVIF for all variables is less than 1.66. bMcFadden's R2 = 0.271. GVIF for all variables is less than 1.51. – for variables without statistical significance that were removed by stepwise regression. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

| Factor | Male (n = 1002)a | Female (n = 857)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Demographic information | ||||

| Economic zone (vs Eastern) | ||||

| Central | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) | 0.193 | – | – |

| Western | 0.96 (0.62–1.48) | 0.862 | – | – |

| Northeast | 0.27 (0.09–0.77) | 0.014 | – | – |

| Grade (vs 1) | ||||

| 2 | 0.83 (0.49–1.38) | 0.465 | – | – |

| 3 | 0.99 (0.59–1.66) | 0.983 | – | – |

| 4 or 5 | 0.59 (0.32–1.10) | 0.096 | – | – |

| Postgraduate | 0.22 (0.08–0.64) | 0.006 | – | – |

| Exercise frequency (vs < once a week) | ||||

| 1–2 times a week | 1.41 (0.91–2.19) | 0.121 | – | – |

| ≥ 3 times a week | 0.72 (0.44–1.17) | 0.183 | – | – |

| Social relations | ||||

| Being in love now (yes vs no) | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | 0.108 | – | – |

| Never participate in student organizations (vs ever) | 1.40 (0.96–2.06) | 0.081 | 1.39 (0.95–2.04) | 0.091 |

| Childhood bullying experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.10 (0.76–1.60) | 0.604 | 1.46 (1.00–2.15) | 0.052 |

| Sometimes | 3.52 (2.00–6.22) | < 0.001 | 2.44 (1.37–4.34) | 0.002 |

| Often | 4.56 (1.20–17.35) | 0.026 | 3.09 (0.76–12.53) | 0.113 |

| Family information | ||||

| Monthly household income per capita (vs < 309 USD) | ||||

| 309–772 USD | 1.99 (0.95–4.19) | 0.070 | – | – |

| 772–1543 USD | 2.48 (1.17–5.22) | 0.017 | – | – |

| > 1543 USD | 1.72 (0.80–3.67) | 0.164 | – | – |

| Closeness of family relationship (vs close) | ||||

| General | 1.68 (1.10–2.56) | 0.016 | – | – |

| Alienated | 1.92 (0.47–7.85) | 0.363 | – | – |

| Number of siblings (vs 0) | ||||

| 1 | 1.43 (1.01–2.03) | 0.045 | 1.13 (0.78–1.65) | 0.521 |

| 2 | 2.55 (1.49–4.35) | < 0.001 | 1.84 (1.14–2.98) | 0.013 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.27 (0.44–3.69) | 0.664 | 0.70 (0.28–1.76) | 0.454 |

| Childhood adversity experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.59 (1.07–2.35) | 0.021 | 1.78 (1.20–2.64) | 0.004 |

| Sometimes | 2.84 (1.73–4.67) | < 0.001 | 2.40 (1.41–4.10) | 0.001 |

| Often | 8.37 (2.77–25.28) | < 0.001 | 24.16 (2.99–195.48) | 0.003 |

| Self-evaluation | ||||

| Mobile phone dependence (vs no) | ||||

| General | 2.27 (1.53–3.38) | < 0.001 | 2.61 (1.62–4.20) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 4.10 (2.54–6.63) | < 0.001 | 7.56 (4.54–12.61) | < 0.001 |

| Appearance satisfaction (vs not very satisfied) | ||||

| Moderately satisfied | 0.72 (0.42–1.22) | 0.219 | – | – |

| Quite satisfied | 0.50 (0.28–0.89) | 0.019 | – | – |

| Mental health self-assessment (vs not very healthy) | ||||

| Moderately healthy | 1.17 (0.53–2.62) | 0.693 | 0.44 (0.19–1.03) | 0.059 |

| Quite healthy | 0.64 (0.29–1.43) | 0.273 | 0.17 (0.08–0.39) | < 0.001 |

| Degree of trust in strangers (vs not very trust) | ||||

| Moderately trust | – | – | 0.70 (0.48–1.03) | 0.072 |

| Quite trust | – | – | 1.12 (0.71–1.76) | 0.637 |

For students from urban areas, risk factors for social phobia were never participating in student organizations (OR = 1.66), sometimes or often being bullied (OR: 2.07–3.37, vs never been bullied), low-middle household income (OR = 2.79, vs low household income), permissive parents (OR = 4.67, vs authoritative parents), having 1 or 2 siblings (OR: 1.41–2.82, vs no sibling), higher frequencies of childhood adversity (OR: 1.73–12.23, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 2.04–4.64); protective factors were female gender (OR = 0.73), being from northeast of China (OR = 0.40, vs eastern China), and self-perceived mentally quite healthy (OR = 0.30, vs not very healthy).

For students from rural areas, risk factors for social phobia were sometimes been bullied (OR = 5.93, vs never been bullied), often experienced childhood adversity (OR = 19.78, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 3.05–5.89); protective factors were female gender (OR = 0.58), being a postgraduate or grade 4/5 student (OR: 0.22–0.38, vs grade 1), exercise ≥ 3 times a week (OR = 0.54, vs less than once a week), being quite satisfied with their appearance (OR = 0.48, vs not very satisfied), and moderately trust in strangers (OR = 0.59, vs not very trust) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression of the influencing factors of social phobia between urban and rural college students (subgroup analysis). aMcFadden's R2 = 0.294, GVIF for all variables is less than 1.58. bMcFadden's R2 = 0.287, GVIF for all variables is less than 1.53. – for variables without statistical significance that were removed by stepwise regression. OR odds ratio, USD United States dollar.

| Factor | Urban (n = 1257)a | Rural (n = 602)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Demographic information | ||||

| Gender (female vs male) | 0.73 (0.55–0.96) | 0.027 | 0.58 (0.38–0.89) | 0.013 |

| Economic zone (vs Eastern) | ||||

| Central | 1.09 (0.77–1.56) | 0.630 | – | – |

| Western | 0.95 (0.65–1.38) | 0.792 | – | – |

| Northeast | 0.40 (0.20–0.79) | 0.009 | – | – |

| Grade (vs 1) | ||||

| 2 | – | – | 0.66 (0.37–1.16) | 0.149 |

| 3 | – | – | 0.65 (0.37–1.14) | 0.136 |

| 4 or 5 | – | – | 0.38 (0.18–0.80) | 0.011 |

| Postgraduate | – | – | 0.22 (0.06–0.75) | 0.015 |

| Exercise frequency (vs < once a week) | ||||

| 1–2 times a week | – | – | 1.12 (0.70–1.80) | 0.642 |

| ≥ 3 times a week | – | – | 0.54 (0.31–0.95) | 0.034 |

| Social relations | ||||

| Never participate in student organizations (vs ever) | 1.66 (1.17–2.36) | 0.004 | ||

| Childhood bullying experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.15 (0.83–1.59) | 0.402 | 1.47 (0.93–2.34) | 0.102 |

| Sometimes | 2.07 (1.28–3.36) | 0.003 | 5.93 (2.87–12.24) | < 0.001 |

| Often | 3.37 (1.13–10.04) | 0.029 | 3.63 (0.64–20.48) | 0.144 |

| Family information | ||||

| Monthly household income per capita (vs < 309 USD) | ||||

| 309–772 USD | 2.79 (1.21–6.41) | 0.016 | – | – |

| 772–1543 USD | 2.11 (0.94–4.77) | 0.072 | – | – |

| > 1543 USD | 1.69 (0.74–3.87) | 0.212 | – | – |

| Parenting style (vs authoritative) | ||||

| Authoritarian | 1.38 (0.88–2.15) | 0.156 | – | – |

| Neglectful | 1.01 (0.67–1.53) | 0.965 | – | – |

| Permissive | 4.67 (1.44–15.17) | 0.010 | – | – |

| Number of siblings (vs 0) | ||||

| 1 | 1.41 (1.03–1.93) | 0.031 | – | – |

| 2 | 2.82 (1.75–4.55) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| ≥ 3 | 0.95 (0.26–3.40) | 0.933 | – | – |

| Childhood adversity experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.73 (1.24–2.43) | 0.001 | 1.52 (0.94–2.47) | 0.090 |

| Sometimes | 3.60 (2.28–5.69) | < 0.001 | 1.50 (0.82–2.74) | 0.183 |

| Often | 12.23 (4.38–34.17) | < 0.001 | 19.78 (2.17–180.54) | 0.008 |

| Self-evaluation | ||||

| Mobile phone dependence (vs no) | ||||

| General | 2.04 (1.42–2.93) | < 0.001 | 3.05 (1.76–5.27) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 4.64 (3.07–7.02) | < 0.001 | 5.89 (3.12–11.13) | < 0.001 |

| Appearance satisfaction (vs not very satisfied) | ||||

| Moderately satisfied | 1.10 (0.71–1.70) | 0.670 | 0.60 (0.34–1.08) | 0.089 |

| Quite satisfied | 0.79 (0.50–1.26) | 0.331 | 0.48 (0.24–0.94) | 0.032 |

| Mental health self-assessment (vs not very healthy) | ||||

| Moderately healthy | 0.83 (0.41–1.65) | 0.586 | 0.85 (0.32–2.27) | 0.746 |

| Quite healthy | 0.30 (0.15–0.61) | < 0.001 | 0.51 (0.19–1.38) | 0.186 |

| Degree of trust in strangers (vs not very trust) | ||||

| Moderately trust | – | – | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) | 0.024 |

| Quite trust | – | – | 0.59 (0.32–1.08) | 0.085 |

For students who were the only child in the family, risk factors for social phobia were sometimes been bullied (OR = 2.32, vs never been bullied), higher frequencies of childhood adversity (OR: 1.52–12.23, vs never experienced childhood adversity), high level of mobile phone dependence (OR: 5.19); protective factors were being from northeast of China (OR = 0.34, vs eastern China), and being quite satisfied with their appearance (OR = 0.34, vs not very satisfied).

For students with siblings, risk factors for social phobia were middle-level GPA (OR: 1.87–2.03, as compared with those in the top quintile), underweight (OR = 1.66), sometimes or often being bullied (OR: 3.63–4.57, vs never been bullied), general family relationships (OR = 1.73, vs close family relationships), having 2 siblings (OR: 1.72, vs having 1 sibling), seldom or often experienced childhood adversity (OR: 1.67–11.63, vs never experienced childhood adversity), and mobile phone dependence (OR: 2.97–5.01); protective factors were female gender (OR = 0.42), being from rural areas (OR = 0.70), overweight (OR = 0.53), being quite satisfied with their appearance (OR = 0.57, vs not very satisfied), and self-perceived mentally quite healthy (OR = 0.26, vs not very healthy) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic regression of the influencing factors of social phobia between the only child and child with siblings (subgroup analysis). aMcFadden's R2 = 0.312. GVIF for all variables is less than 1.57. bMcFadden's R2 = 0.285. GVIF for all variables is less than 1.61. – for variables without statistical significance that were removed by stepwise regression. / for not applicable. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, GPA grade point average, USD United States dollar.

| Factor | The only child (n = 873)a | Child with siblings (n = 986)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Demographic information | ||||

| Gender (female vs male) | – | – | 0.42 (0.30–0.59) | < 0.001 |

| Nation (ethnic minorities vs ethnic Han) | 2.05 (0.95–4.46) | 0.069 | – | – |

| Economic zone (vs Eastern) | ||||

| Central | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | 0.338 | – | – |

| Western | 0.77 (0.48–1.24) | 0.284 | – | – |

| Northeast | 0.34 (0.17–0.69) | 0.003 | – | – |

| Region (rural vs urban) | – | – | 0.70 (0.51–0.98) | 0.037 |

| College type (985 vs non-985) | – | – | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | 0.144 |

| GPA ranking (vs top 20%) | ||||

| 20–40% | – | – | 2.03 (1.27–3.24) | 0.003 |

| 40–60% | – | – | 1.87 (1.14–3.08) | 0.013 |

| 60–80% | – | – | 1.47 (0.74–2.91) | 0.275 |

| After 80% | – | – | 2.39 (0.91–6.32) | 0.078 |

| BMI (vs normal) | ||||

| Overweight | – | – | 0.53 (0.30–0.93) | 0.028 |

| Obesity | – | – | 1.68 (0.62–4.58) | 0.308 |

| Underweight | – | – | 1.66 (1.13–2.44) | 0.010 |

| Exercise frequency (vs < once a week) | ||||

| 1–2 times a week | 0.99 (0.62–1.57) | 0.954 | – | – |

| ≥ 3 times a week | 0.66 (0.40–1.11) | 0.120 | – | – |

| Social relations | ||||

| Being in love now (yes vs no) | – | – | 0.78 (0.57–1.08) | 0.141 |

| Never participate in student organizations (vs ever) | – | – | 1.32 (0.92–1.89) | 0.127 |

| Childhood bullying experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.33 (0.89–1.99) | 0.165 | 1.13 (0.79–1.63) | 0.504 |

| Sometimes | 2.32 (1.29–4.18) | 0.005 | 3.63 (2.06–6.40) | < 0.001 |

| Often | 2.43 (0.70–8.40) | 0.161 | 4.57 (1.11–18.74) | 0.035 |

| Family information | ||||

| Monthly household income per capita (vs < 309 USD) | ||||

| 309–772 USD | 2.22 (0.85–5.82) | 0.104 | – | – |

| 772–1543 USD | 1.61 (0.63–4.15) | 0.322 | – | – |

| > 1543 USD | 1.19 (0.46–3.11) | 0.716 | – | – |

| Closeness of family relationship (vs close) | ||||

| General | – | – | 1.73 (1.17–2.54) | 0.006 |

| Alienated | – | – | 1.12 (0.39–3.23) | 0.830 |

| Number of siblings (vs 1) | ||||

| 2 | / | / | 1.72 (1.19–2.48) | 0.004 |

| ≥ 3 | / | / | 0.85 (0.43–1.70) | 0.654 |

| Childhood adversity experience (vs never) | ||||

| Seldom | 1.52 (1.00–2.31) | 0.049 | 1.67 (1.15–2.45) | 0.008 |

| Sometimes | 5.09 (2.95–8.78) | < 0.001 | 1.46 (0.89–2.39) | 0.137 |

| Often | 12.23 (3.71–40.32) | < 0.001 | 11.63 (2.51–53.90) | 0.002 |

| Self-evaluation | ||||

| Mobile phone dependence (vs no) | ||||

| General | 1.49 (0.95–2.35) | 0.086 | 2.97 (1.96–4.50) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 5.19 (3.15–8.54) | < 0.001 | 5.01 (3.09–8.14) | < 0.001 |

| Appearance satisfaction (vs not very satisfied) | ||||

| Moderately satisfied | 1.02 (0.48–2.15) | 0.962 | 0.86 (0.54–1.36) | 0.523 |

| Quite satisfied | 0.34 (0.16–0.71) | 0.004 | 0.57 (0.34–0.96) | 0.035 |

| Mental health self-assessment (vs not very healthy) | ||||

| Moderately healthy | – | – | 0.54 (0.22–1.34) | 0.182 |

| Quite healthy | – | – | 0.26 (0.11–0.66) | 0.004 |

| Degree of trust in strangers (vs not very trust) | ||||

| Moderately trust | – | – | 0.76 (0.53–1.08) | 0.125 |

| Quite trust | – | – | 1.18 (0.75–1.87) | 0.475 |

Sensitivity analyses

The three different variable selection methods, namely the backward regression, forward regression, and stepwise regression followed by optimal subset regression, all provided models that were completely consistent with the main analysis (stepwise regression), indicating that the variable selection method in this study did not affect the robustness of the regression results. The results based on two different outcome variable classification criteria, namely the tertiles and quartiles (Supplementary Tables S1, S2), are basically consistent with the main analysis, indicating that the regression results were robust for different outcome variable classification criteria. Very few variables with significant margins transition to insignificant in sensitivity analysis results, which may be due to the loss of statistical power in the division of ordered multinomial outcomes compared to binary classification outcomes in the regression.

College students’ social phobia score in pre- and early-COVID-19 periods

Before the outbreak of COVID-19, the college students’ average social phobia score was 12.3 ± 11.9, with a median (P25–P75) of 9 (2–20). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the average score was 13.4 ± 11.9, with a median (P25–P75) of 10 (3–21), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. During the pandemic, college students’ social phobia scores increased by 1.0 ± 6.4, with a median (P25–P75) of 0 (− 1 to 2), as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test showed as statistically significant (P < 0.001). During the pandemic, 28.8% of respondents’ social phobia was alleviated (score reduced), 27.5% had no significant change (score unchanged), and 43.7% were intensified (score increased).

Influencing factors of retrospective self-reported change between college students’ social phobia in pre- and early-COVID-19 periods

The proportions of respondents who considered wearing a mask, online asking or answering questions, online presentation, setting a baffle on the canteen dining table, keeping a one-meter social distance, and getting COVID-19 vaccinated alleviated their social phobia were 46.4%, 43.9%, 41.3%, 41.2%, 40.0%, and 33.1%, respectively. Nearly half of the respondents considered these measures to have no impact on their social phobia status. Only about 10% of the respondents considered these measures aggravated their social phobia (Supplementary Table S3).

Multivariable 3-level ordinal logistic regression showed that the potential risk factors for social phobia aggravation might be: thinking the table baffle did not affect social phobia (OR = 1.30, vs thinking that could alleviate social phobia), having 2 siblings (OR = 1.38, vs no sibling), and obesity (OR = 1.78). The potential protective factors might be thinking COVID-19 vaccination did not affect social phobia (OR = 0.73, vs thinking that could alleviate social phobia), exercise 1–2 times a week (OR = 0.80, vs less than once a week) (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

This study is one of the few nationwide studies in China focusing on college students’ SP and its influencing factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infectious disease pandemics have a lasting impact on mental health38,39. The following study showed that psychological distress slowly declined over 28 months during an avian influenza pandemic38; another study showed that among those infected with SARS, the psychiatric effects were long-term39. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic led to dramatic changes in lifestyles around the world and has had detrimental effects on mental health40, and it appeared unlikely that mental health would return to pre-pandemic levels in the near future41. Our study showed that the social phobia level among Chinese college students slightly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. This may be related to the increase in measures such as quarantine and lockdowns, avoidance of non-essential social interactions, and online learning during COVID-19, which reinforced social avoidance and took away the sense of well-being gained from interacting with others42.

Our study indicated that SP among Chinese college students was widely influenced by factors from individuals, families, social relations, and self-evaluations, and were diverse by gender, region, and whether he/she was the only child.

On the aspect of individuals, we found that senior students are associated with a decrease in the risk of SP. Concerning relevant studies in other countries, we found similar patterns to our research43–45. The possible reasons for this are that lower-grade students may live away from their parents for the first time, out of a comfortable social environment, and on the other hand, as they age and progress in learning, they might gradually adapt to new life and social environments46. The subgroup analysis showed that this protective effect mainly appears in rural students. This may be because the new students from rural areas have relatively little experience in urban university life, and with the growth of grades, life experience, and interpersonal relationships increase, alleviating their SP.

With regard to family and social relations, college students with permissive parents demonstrated a higher risk of SP than those from authoritative parents. It is possible that children with highly permissive parents may develop a self-centered personality that may contribute to poor interpersonal interactions out of the home, leading to a higher risk of SP47. But it is also possible that growing up with highly permissive parents will lead to the less independence in the child and lowered self-confidence in their social interactions48. We also found that the SP risk of the only child is lower than that of students with siblings, which was consistent with a study in China47. According to a study conducted in Canada, non-only children are more likely to have conflicts and social contagion (i.e. adolescents are more prone to mimic their siblings’ expressions) with their siblings, which has been associated with the onset and exacerbation of both anxiety and social phobia49. In subgroup analysis, the association between having siblings and SP was mainly manifested in urban students. This may be because urban families are relatively more independent from neighbors, so children may have more communication with siblings, but less with other peers, leading to SP. Childhood adversity and peer bullying experiences were risk factors for SP, which was consistent with studies in China and other countries50,51. Childhood adversity and peer bullying experience will lead to lower self-esteem and self-evaluation in adulthood and will produce distrust and insecurity towards others51,52, resulting in social phobia in interpersonal communication.

On the aspect of self-appraisal and self-image, our study showed that individuals who consider themselves mentally healthy had a lower risk of developing SP, and notably, this phenomenon was particularly pronounced among females, aligning with previous research findings53. We also found that the satisfaction of self-appearance was negatively associated with SP, suggesting that self-abasement due to their outer appearance may prefer avoiding social contact and developing SP54. Similar findings from a study in the United Kingdom also imply that negative self-imagery is associated with a higher degree of social disengagement and an increased risk of SP55. Besides, in our study, students with low level of interpersonal trust score higher on SP. A previous study showed that during a pandemic, the level of trust between people may be reduced, leading to negative psychological states such as interpersonal trust crisis, social phobia, and loneliness56, which might explain the aggravation of social phobia during the pandemic among college students in our study. Mobile phone dependence had a very high risk on SP, and this effect seemed to be universal since it existed in all subgroups of this study. An Indian undergraduates-based study also showed that students with social phobia were more unable to cut down on smartphone usage57. Many other studies also indicated that smartphones could both alleviate loneliness and increase anxiety when not available58,59.

Our descriptive study showed that more people believed that the COVID-19 prevention measures would alleviate SP, however, SP score had slightly increased during the pandemic. This might be due to the influence of unconsidered confounding factors. For example, the outbreak itself can increase anxiety levels in the population, which may aggravate SP. According to our regression results, setting canteen baffles was a potential protective factor against social phobia aggravation. A prior study indicated that individuals with SP were more likely to use voice or text media rather than visual media60, and the baffles blocked the visual media, which might alleviate their SP degree. Unfortunately, McFadden’s R2 of this regression model was only 0.011, suggesting that it had insufficient explanatory power and there were unknown influencing factors, which need further research in the future.

College administrators should pay more attention to the SP among students and can carry out screening, assessment, tracking, and early intervention of high-risk groups. Especially for freshmen (particularly boys from rural areas), students with lower GPA rankings, and students with other psychological disorders. In addition, eliminating campus bullying and promoting the reduction of smartphone dependence are also measures recommended for college administrators to prevent students from SP.

Limitations

Recall bias in the retrospective collection of social phobia status in pre-COVID-19 period was the major limitation in our study. We were very cautious in interpreting the exploratory results of the retrospective self-reported change in social phobia between pre- and early-COVID-19 periods and have mainly focused our research on the influencing factors of the current social phobia status among college students. In addition, although SIAS-6/SPS-6 is simple and applicable to Chinese college students, it lacks a threshold for the diagnosis of social phobia, so we cannot calculate the prevalence of social phobia to compare with previous studies.

Conclusions

Social phobia among Chinese college students was widely influenced by individuals, families, social relations, and self-evaluations, and was diverse by gender, region, and whether he/she was the only child. The results have a reference value for early screening and risk factor intervention of Chinese college students’ social phobia. Most participants subjectively believed that COVID-19 prevention and control measures could alleviate social phobia to a certain extent in early-COVID-19 period, but its real effect is still uncertain, and more in-depth research needs to be carried out in the future.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Zhou Fuchun, chief physician of Beijing Anding Hospital Capital Medical University, for his valuable time and support when conducting this study.

Abbreviations

- SP

Social phobia

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease

- SIAS-6/SPS-6

The Peters short form of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale

- SIAS

Social Interaction Anxiety Scale

- SPS

Social Phobia Scale

- BMI

Body mass index

- GPA

Grade point average

- CNY

China Yuan

- USD

United States dollar

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- IP

Internet Protocol

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- GVIF

Generalized variance inflation factors

Author contributions

Z.Y., H.L. and H.Y. contributed to the overall design and conceptualization. H.L., Z.Y., S.H., C.S., Z.Z. and Y.R. collected the data. Z.Y. and H.L. contributed to data analysis. H.L., Z.Y., S.H., C.S., Z.Z. and Y.R. contributed to data interpretation and the original draft writing. H.Y. contributed to the editing and revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the China Population Welfare Foundation, through a “Family Development Fund for Respecting the Elderly and Caring for the Young (ID 2021010)”.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hai Lin and Ziming Yang.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-48225-y.

References

- 1.Wu C. A Study on the Alleviation of Social Phobia Among College Students. Liaoning University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo Z. Causes of social phobia in college students and intervention strategies. J. Kaifeng Inst. Educ. 2014;34:192–193. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan Z, Zhang D, Hu T, Pan Y. The relationship between psychological Suzhi and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-esteem and sense of security. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health. 2018;12:50. doi: 10.1186/s13034-018-0255-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, Roberson-Nay R. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein DJ, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: Data from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. BMC Med. 2017;15:143. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0889-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng J. Changes in the Mental Health Level of College Students from 2008 to 2018: A Case Study of a University in Guangxi. University Education; 2019. pp. 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu G, Jiang J. Research progress on social anxiety in adolescents in China. J. Xinyang Normal Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2015;35:24–28+74. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H, Zhai C, Ding G. Research on the status quo and influencing factors of social phobia in clinical college students of a medical college in Shandong Province. J. Taishan Med. Coll. 2019;40:699–702. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baptista CA, et al. Social phobia in Brazilian university students: Prevalence, under-recognition and academic impairment in women. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;136:857–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu W, et al. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese college students: The moderating roles of social phobia and perceived family economic status. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;139:106113. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qianwen LLC. Survey and analysis of college students’ mental health. J. Campus Life Ment. Health. 2022;20:433–439. doi: 10.19521/j.cnki.1673-1662.2022.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Li G, Chen H. A follow-up study on social phobia and Internet addiction in college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2022;36:805–809. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du C. Investigation and Analysis of College Students’ Social Anxiety: Take Tianjin as an Example. Tianjin University of Finance and Economics; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melkam M, Segon T, Nakie G. Social phobia of Ethiopian students: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2023;12:41. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakie G, Melkam M, Desalegn GT, Zeleke TA. Prevalence and associated factors of social phobia among high school adolescents in Northwest Ethiopia, 2021. Front. Psychiatry. 2022;13:949124. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, Cao Q. Survey and analysis of college students’ mental health. J. Campus Life Ment. Health. 2022;20:433–439. doi: 10.19521/j.cnki.1673-1662.2022.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennifer C, Brynjar H, Cathy C. Mental imagery in social anxiety in children and young people: A systematic review. Clin. Child Family Psychol. Rev. 2020;23:379–392. doi: 10.1007/s10567-020-00316-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefferies P, Ungar M. Social anxiety in young people: A prevalence study in seven countries. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, Z. Attention should be paid to the study of social anxiety. Fujian Forum (Economic and Social Edition), 60–61 (1993).

- 20.Qian Z. Analysis on the status and influencing factors of social anxiety of college students in a university in Changchun city. Med. Soc. 2020;33:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Han ZX, Zhang S, Zhao Y, An H. Analysis of present situation and influencing factors of social anxiety disorder in adolescents aged 13 to 19 in Weifang. Chin. J. Hosp. Stat. 2016;23:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Considerations for public health and social measures in the workplace in the context of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Adjusting_PH_measures-Workplaces-2020.1

- 23.World Health Organization. Considerations for school-related public health measures in the context of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/considerations-for-school-related-public-health-measures-in-the-context-of-covid-19 (2020).

- 24.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. The prevention and control COVID-19 pandemic. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/xxgzbd/gzbd_index.shtml (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. Notice on technical guidelines for the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic in key places, key units, and key populations. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202004/b90add4a70d042308b8c3d4276ec76a7.shtml (2020).

- 26.Khan AN, Bilek E, Tomlinson RC, Becker-Haimes EM. Treating social anxiety in an era of social distancing: Adapting exposure therapy for youth during COVID-19. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson C, Mancebo MC, Moitra E. Changes in social anxiety symptoms and loneliness after increased isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;298:113834. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrissette M. School closures and social anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021;60:6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters L, Sunderland M, Andrews G, Rapee RM, Mattick RP. Development of a short form Social Interaction Anxiety (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS) using nonparametric item response theory: The SIAS-6 and the SPS-6. Psychol. Assess. 2012;24:66–76. doi: 10.1037/a0024544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouyang X, Cai Y, Tu D. Psychometric properties of the short forms of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale in a Chinese college sample. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:2214. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunderland M, et al. Comparing scores from full length, short form, and adaptive tests of the social interaction anxiety and social phobia scales. Assessment. 2020;27:518–532. doi: 10.1177/1073191119832657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carleton RN, et al. Comparing short forms of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Psychol. Assess. 2014;26:1116–1126. doi: 10.1037/a0037063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China and Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China: Opinions on continuing to implement the construction project of “985 Project”. China Modern Educational Equipment, 71–73 (2004).

- 34.National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. IV. Statistical system and classification standards (17). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjzs/cjwtjd/201308/t20130829_74318.html

- 35.National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Census data. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/ (2021).

- 36.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Update on the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Outbreak as of 24:00 on August 12. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202108/de4bafbc9a164100b1a32c04f7b54486.shtml (2021).

- 37.Office of the Leading Group for the 7th National Population Census of the State Council . China Population Census Yearbook 2020. China Statistics Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau JTF, Tsui HY, Kim JH, Chan PKS, Griffiths S. Monitoring of perceptions, anticipated behavioral, and psychological responses related to H5N1 influenza. Infection. 2010;38:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mak IWC, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MGC, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2009;31:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbay RY, Kurtulmuş A, Arpacıoğlu S, Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quintana-Domeque C, Proto E. On the Persistence of Mental Health Deterioration during the COVID-19 Pandemic by Sex and Ethnicity in the UK: Evidence from Understanding Society. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy. 2021;22:361–372. doi: 10.1515/bejeap-2021-0394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kindred R, Bates GW. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on social anxiety: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023 doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desalegn GT, Getinet W, Tadie G. The prevalence and correlates of social phobia among undergraduate health science students in Gondar, Gondar Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:438. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabie M, et al. Screening of social phobia symptoms in a sample of Egyptian university students. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clín. 2019;46:27–32. doi: 10.1590/0101-60830000000188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seidi P. Prevalence of social anxiety in students of college of education—University of Garmian. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2017;8:79. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Djidonou A, et al. Associated factors and impacts of social phobia on academic performance among students from the University of Parakou (UP) Open J. Psychiatry. 2016;6:151–157. doi: 10.4236/ojpsych.2016.62018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren S. Investigation and analysis of social anxiety in college students. J. Yangzhou Univ. Higher Educ. Res. Ed. 2007;6:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, Y. Analysis and reflection on the harm of doting in children's family education. Sci. Educ. Cult.2 (2010).

- 49.Poirier CS, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Dionne G, Boivin M. Contagion of anxiety symptoms among adolescent siblings: A twin study. J. Res. Adolesc. 2016;27:65–77. doi: 10.1111/jora.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norton AR, Abbott MJ. The role of environmental factors in the aetiology of social anxiety disorder: A review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Behav. Change. 2017;34:76–97. doi: 10.1017/bec.2017.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Q. Association of childhood intrafamilial aggression and childhood peer bullying with adult depressive symptoms in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3:e2012557. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma, A., Yu, X., Liu, X., Dong, J. & Wang, X. Childhood abuse, coping style, self-esteem and adolescent social phobia (2022).

- 53.Vaingankar JA, et al. Understanding the relationships between mental disorders, self-reported health outcomes and positive mental health: Findings from a national survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020;18:55. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu, W. & Xie, X. The relationship between college students’ self-esteem and social anxiety. China Electric Power Education (2011).

- 55.Chiu K, Clark DM, Leigh E. Characterising negative mental imagery in adolescent social anxiety. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022;46:956–966. doi: 10.1007/s10608-022-10316-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J. Anxiety, rationality and order in the “stranger society” in major epidemics—Also on the countermeasures to weaken the irrational order of “stranger society” in the epidemic situation of New Coronavirus pneumonia. J. Xihua Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020;39:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Honnekeri BS, Goel A, Umate M, Shah N, De Sousa A. Social anxiety and Internet socialization in Indian undergraduate students: An exploratory study. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2017;27:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chai, X. Investigation and analysis of College Students’ mobile phone dependence and social anxiety—A case study of a university in Hainan. Shang1 (2014).

- 59.Sun J, Dong B, Yu Y. The relationship between College Students' mobile phone dependence, social anxiety and loneliness. J. Gannan Norm. Univ. 2017;38:4. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oren-Yagoda R, Aderka IM. The Medium is the message: Effects of mediums of communication on perceptions and emotions in social anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021;83:102458. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.