Abstract

Approximately 20 % of human cancers are associated with virus infection. DNA tumor viruses can induce tumor formation in host cells by disrupting the cell's DNA replication and repair mechanisms. Specifically, these viruses interfere with the host cell's DNA damage response (DDR), which is a complex network of signaling pathways that is essential for maintaining the integrity of the genome. DNA tumor viruses can disrupt these pathways by expressing oncoproteins that mimic or inhibit various DDR components, thereby promoting genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Recent studies have highlighted the molecular mechanisms by which DNA tumor viruses interact with DDR components, as well as the ways in which these interactions contribute to viral replication and tumorigenesis. Understanding the interplay between DNA tumor viruses and the DDR pathway is critical for developing effective strategies to prevent and treat virally associated cancers. In this review, we discuss the current state of knowledge regarding the mechanisms by which human papillomavirus (HPV), merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) interfere with DDR pathways to facilitate their respective life cycles, and the consequences of such interference on genomic stability and cancer development.

1. Introduction

The ability to rapidly and accurately repair damaged DNA is essential to cell survival and the maintenance of genome stability. To accomplish these goals, cells have evolved complex mechanisms for DNA damage detection and repair, collectively known as the DNA damage response (DDR) [1]. The DDR is a critical tumor suppressor pathway consisting of DNA damage sensors as well as transducers and effectors that coordinate cell cycle regulation with DNA repair. The DDR also responds to viruses and can impact virus growth either positively or negatively through direct effects on the viral genome or through the activation of signaling pathways that can impact the viral life cycle. Oncogenic virus infection and DDR activation are tightly linked to the expression of viral oncoproteins, which induce cellular stress as well as perturb cellular DNA repair pathways to provide an environment conducive to viral replication and persistence. Because of DDR deregulation, DNA tumor viruses can inadvertently predispose infected cells to genomic instability and cancer development. This review will focus on the interplay between the DDR and the life cycle of four DNA tumor viruses: HPV and MCPyV as representative small DNA tumor viruses, and the gamma-herpesviruses KSHV and EBV as representative large DNA tumor viruses. We will first provide an overview of the cellular DDR sensing pathways, then discuss the mechanisms by which each virus modulates the DDR over the course of their respective life cycles. Additionally, we will discuss how induction of host DNA damage and DDR deregulation by these oncogenic viruses can lead to genomic instability, a hallmark of virally-induced cancers [2].

2. Overview of the DNA damage response

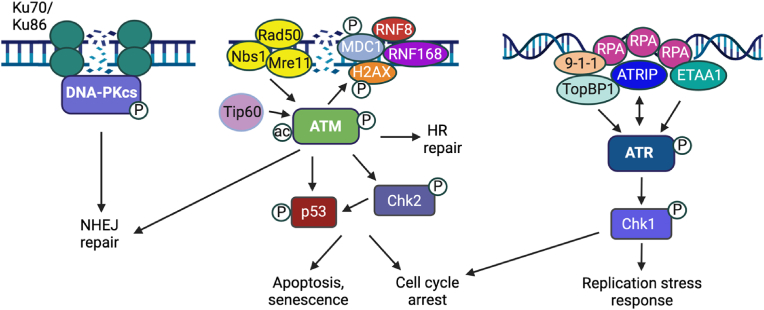

DNA damage can occur through endogenous sources, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA replication errors, as well as through exogenous sources, including ionizing radiation (IR), ultraviolet light (UV), and chemical mutagens. The DNA damage response (DDR) is primarily initiated by serine-threonine kinases of the PIKK family that recognize certain types of DNA damage [3] (Fig. 1). ATM (ataxia–telangiectasia mutated) and DNA-PKcs (DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit) are activated in response to double strand DNA breaks (DSBs) during all phases of the cell cycle, while ATR (ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related) is activated by single strand DNA (ssDNA) that forms in response to resection of DSBs as well as stalled replication forks in S-phase. DDR kinases are activated by DNA damage sensing proteins or complexes. Upon binding to DSBs, the MRN complex (MRE11, RAD50, NBS1) recruits and activates ATM; the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recruits and activates DNA-PKcs; and ATRIP (ATR-interacting protein) binding to ssDNA recruits ATR to initiate its activation. Once activated, these kinases phosphorylate numerous downstream targets to recruit DDR factors to sites of DNA damage. The DDR also initiates cell cycle checkpoints to allow time for DNA to be repaired, but also to prevent cells with persistent DSBs from progressing through the cell cycle and being repaired aberrantly, which can lead to chromosomal rearrangements and cellular transformation. Extensive DNA damage can lead to the activation of apoptotic pathways that are largely mediated downstream of ATM activation via p53 [1] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the cellular DNA damage response. ATM and DNA-PKcs are activated in response to double-strand DNA breaks (DSB). The MRN complex is a DSB sensor and recruits ATM to promote its autophosphorylation and activation. Tip60-mediated acetylation of ATM is required for its full activation. ATM can facilitate repair through HR or NHEJ by initiating a chromatin-based signaling cascade through phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX), resulting in the recruitment of the RNF8 and RNF168 ubiquitin ligases to sites of DNA damage. RNF168 ubiquitinates H2A on lys15 to recruit 53BP1, which promotes NHEJ repair, or the BARD1-BRCA1 complex to promote HR repair (not shown). DNA-PKcs is recruited to DSBs by the Ku70/Ku86 complex, which promotes DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation and activation, resulting in repair through NHEJ. ATR is activated in response to ssDNA that forms upon replication fork stalling or resection of DSBs. ATR is recruited to RPA-coated ssDNA by ATRIP. ATR is fully activated by TopBP1, which is recruited to ssDNA by the 9-1-1 complex, or by ETAA1, which is recruited to RPA-coated ssDNA at stalled replication forks. Signaling through DNA damage kinases result in the activation of cell cycle checkpoints to allow time for DNA to be repaired or for cells to undergo apoptosis or senescence if the damage is too severe. Ac = acetylation. P = phosphorylation. Additional details in text. Created using BioRender.com.

DSBs are the most deleterious type of DNA lesions and are primarily repaired by one of two major pathways: Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR) [4]. NHEJ ligates broken ends together and can occur throughout the cell cycle, while HR is restricted to the S- and G2-phases due to the need of a homologous template for precise repair, typically a sister chromatid [5]. NHEJ is typically considered error prone but is the predominant pathway used during interphase for the repair of two-ended DSBs. In contrast, single-ended DSBs that form due to the collapse of replication forks in S-phase must be repaired by HR as NHEJ repair could be toxic due to the re-legation of DNA ends on different chromosomes [6].

ATM can facilitate DNA repair through NHEJ as well as HR. Upon recruitment to DSBs, ATM initiates a chromatin-based signaling cascade through the phosphorylation of the histone variant H2AX (referred to as γH2AX), which ultimately recruits the ubiquitin ligases RNF8 and RNF168. RNF168 mono-ubiquitinates histone H2A on lysine 15 (H2AK15ub), which along with H4K20me2 deposited on mature chromatin, recruits 53BP1 to promote NHEJ repair [7,8]. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of 53BP1 triggers the recruitment of downstream factors (e.g., RIF1, Shieldin complex) that block DSB end resection, the critical step for HR initiation [9,10]. In S/G2 phases, however, RNF168-mediated H2AK15ub, along with H4K20me0 on newly replicated DNA, recruits the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, whereby BRCA1 overcomes the 53BP1 anti-resection barrier to stimulate HR [[11], [12], [13]]. Initial end resection is mediated by MRE11 of the MRN complex along with the resection factor CtIP, which results in the removal of the Ku complex from DNA ends, preventing NHEJ [14]. Long range resection is then carried out by BLM-DNA2 helicase-nuclease or Exo1, forming ssDNA that is coated by RPA. RPA is replaced by Rad51 through the BRCA2/PALB2/BRCA1 complex to stimulate strand invasion into the sister chromatid, which serves as a template for repair. RPA-coated ssDNA also recruits ATR via its binding partner ATRIP [15]. The 5’ ended ssDNA-dsDNA junction serves as a loading point for the 9-1-1 complex, which recruits the ATR activator TopBP1, allowing for the accumulation of ATR and phosphorylation of specific downstream substrates, including RPA and Chk1. ETAA1 can also promote ATR activation and is recruited to stressed replication forks through direct interactions with RPA-coated ssDNA [16]. ATM and ATR also initiate cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damage through phosphorylation of Chk2 and Chk1, which in turn phosphorylate p53 and Cdc25, respectively, leading to the degradation of Cdc25 and cell cycle arrest or apoptosis [3] (Fig. 1).

The recruitment of the DNA-PKcs to DSBs by the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer complex results in DNA-PKcs activation and formation of the DNA-PK holoenzyme, which is essential for NHEJ repair [17]. DNA-PKcs undergoes autophosphorylation on multiple sites, which promotes the repair process by facilitating synapsis of the broken ends as well as DNA-PK dissociation from DNA ends [[18], [19], [20]]. DNA ligase 4, in complex with its partner XRCC4 and one of the core NHEJ factors XLF or PAXX, catalyzes ligation of the broken ends. NHEJ accessory factors include nucleases (Artemis) and polymerases (μ and λ), which are not required for NHEJ but promote DSB repair under specific conditions [17]. DNA-PK is also regulated by phosphorylation by ATM and ATR. In addition to DNA repair, DNA-PK can activate apoptosis, regulate transcription, and act as a sensor of foreign DNA in the cytoplasm [21].

3. Human papillomavirus

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are small, non-enveloped viruses with a circular double-stranded DNA genome (episome) that commonly infect skin and mucous membranes, causing cutaneous warts, benign genital warts as well as certain types of cancer [22]. High-risk HPV types, including HPV-16, -18, −31, −45, are the causative agents of 99 % of cervical cancers and are associated with several other cancers such as anal, vaginal, vulvar, penile, and a large percentage of head and neck cancers. The HPV life cycle is unique in that the productive phase is tightly linked to epithelial cell differentiation. The viral life cycle is characterized by three phases of replication: establishment, maintenance and productive [23]. Establishment replication occurs when the virus enters the undifferentiated, basal cells of the stratified epithelium. Upon entry into the nucleus, the viral genome undergoes a rapid, transient amplification to a low copy number of 50–100 episomal copies/cell. Viral genomes are subsequently maintained at a constant number in the undifferentiated epithelial cells. The productive phase of the life cycle is triggered upon epithelial differentiation, resulting in the expression of late viral genes, viral genome amplification to hundreds to thousands of copies per cell as well as virion assembly and release from the upper-most layer of the epithelium [24]. Epithelial cells normally exit the cell cycle upon differentiation; however, the HPV E6 and E7 proteins disrupt normal cell cycle checkpoints, causing differentiating cells to re-enter S-phase. Subsequently, the differentiating cells arrest in a G2-like environment that allows HPV access to cellular factors required for efficient viral replication [25].

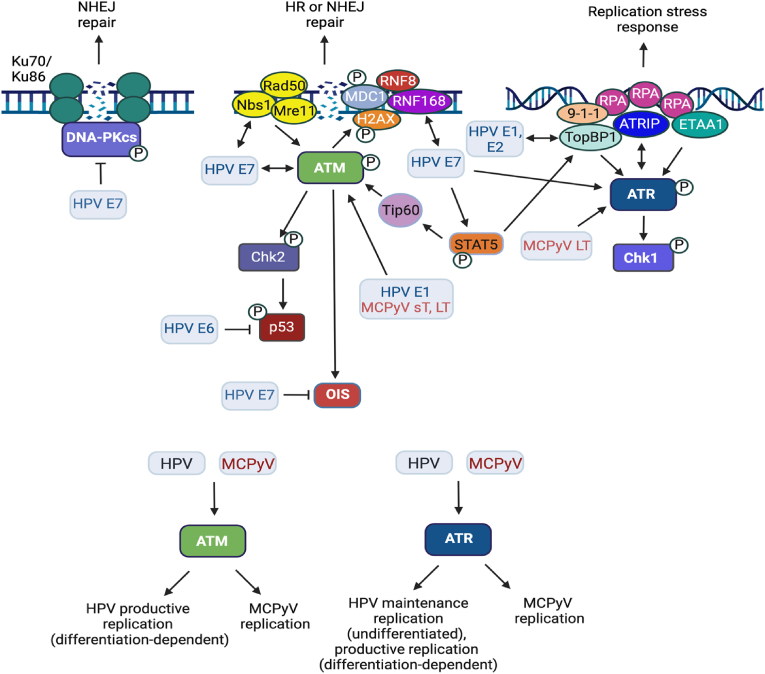

One of the key characteristics of high-risk HPVs is their ability to use host DDR pathways to facilitate viral replication [26] (Fig. 2). Several labs have established that high-risk HPVs exploit the activation of the ATM and ATR DDR pathways to promote viral replication [26]. The first indication that HPVs manipulate DNA repair pathways for viral replication was the observation that high-risk HPV31 positive cells exhibit constitutive activation of the ATM-dependent DDR [27]. Undifferentiated and differentiated HPV31 positive cells exhibit activation of the ATM signaling pathway characterized by phosphorylation of numerous downstream effectors, including ATM itself, as well as Chk2, NBS1, and BRCA1 [27]. Activation of the ATM-dependent DDR has also been observed in keratinocytes stably maintaining high-risk HPV16 or HPV18 episomal genomes [28]. Despite constitutive ATM activation, ATM activity is only required for productive replication upon epithelial differentiation. Inhibition of ATM kinase activity has no discernible effect on episome maintenance in undifferentiated cells [27]. The activation of ATM effector Chk2 is also necessary for productive replication. These results suggest viral genome amplification in differentiating epithelial cells has a specific requirement for the ATM-dependent DDR.

Fig. 2.

Interplay between HPV, MCPyV and the DNA damage response. HPV and MCPyV proteins activate components of the ATM and ATR pathways, while HPV E7 blocks DNA-PK activation. HPV episomes are maintained at a low copy number in the undifferentiated, basal cells of the stratified epithelium in a manner that is dependent on ATR activity. In contrast ATM activity is only required for productive replication, which is triggered by epithelial differentiation. Downstream ATM effectors, including RNF168 and factors involved in HR repair (e.g., MRN complex, Rad51, BRCA1) localize to sites of viral replication and are also specifically required for productive replication, indicating that viral genome amplification in differentiating cells occurs in a recombination-dependent manner. E7 interacts pATM, Nbs1 and RNF168, though the impact of these interactions on viral replication is unclear. The E7-RNF168 interaction may provide a pool of RNF168 for recruitment to viral replication foci at the expense of cellular DSB repair, which may contribute to genomic instability in infected cells. Additionally, E7 induces persistent cellular replication stress and activation of the ATR DDR due to unscheduled entry into S-phase. Viral replication in undifferentiated and differentiated cells also results in replication stress that recruits ATR pathway components to viral replication foci. HPV hijacks the ATR replication stress response to increase RRM2 levels and provide dNTPs for viral replication. HPV bypasses oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) associated with DDR signaling through the actions of E7, further fueling genomic instability. MCPyV also requires ATM and ATR activity for replication, though how ATM/ATR signaling contributes to viral replication is currently unclear. ATM and ATR DDR factors localize to sites of viral replication in a manner dependent on LT and the viral origin, including ATM, ATR, γH2AX, Nbs1, pChk2, and pChk1. Full-length LT induces DNA damage and cell cycle arrest in an ATM-p53-dependent manner, which may limit progression to cancer. This may explain why mature merkel cell carcinomas (MCC) express a truncated LT that lacks the C-terminal helicase domain and is impaired for DDR activation and cell cycle arrest. Additional details in text. Created using BioRender.com.

Multiple ATM effectors localize to sites of HPV replication in both undifferentiated and differentiated cells, including pATM, γH2AX, pChk2, 53BP1, RPA, the MRN complex, as well as the HR repair proteins Rad51 and BRCA1 [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. However, like ATM activity, the MRN complex as well as Rad51 and BRCA1 are only required for productive replication upon differentiation. Together, these results indicate that productive viral replication in differentiating epithelial cells occurs in manner that is dependent on recombination [30,32]. Several factors involved in DNA repair promote HR factor recruitment to amplifying viral DNA upon differentiation. Both SIRT1 and the histone acetyltransferase TIP60 modulate cellular chromatin to direct the pathway of choice for DSB repair to HR [33,34]. The SIRT1 histone deacetylase is elevated in HPV positive cells in an E7-dependent manner, and SIRT1 activity contributes to the binding of Rad51 and NBS1 to viral DNA [35,36]. TIP60 is necessary for productive replication but whether this is through the acetylation and activation of ATM and/or histone modifications of viral chromatin is unclear [37]. Additionally, a recent study from our laboratory showed that histone modifications associated with active transcription, specifically trimethylation of H3K36 (H3K36me3) by the SETD2 methyltransferase, contribute to the recruitment of Rad51 to amplifying HPV31 genomes upon differentiation [38]. Actively transcribed genes are preferentially repaired by HR, which is initiated through the cellular protein LEDGF, a reader of H3K36me3 [39]. In response to DNA damage, LEDGF recruits the resection factor CtIP, which facilitates DSB resection to yield ssDNA that is ultimately bound by Rad51. LEDGF, CtIP and Rad51 are bound to HPV31 DNA in a SETD2-and H3K36me3-dependent manner and are required for productive replication [38]. Transcription inhibition increases DNA damage on viral DNA and decreases Rad51 recruitment, identifying an important role for transcription in recruiting HR factors to viral DNA through epigenetic modifications [38]. BRCA1 is required for productive replication and may also influence repair pathway choice to HR on viral DNA by overcoming the 53BP1-dependent barrier to end resection [32,40]. Another mechanism that may influence HR factor recruitment to productively replicating viral DNA is E7's direct interaction with RNF168. Sitz et al. showed that E7 sequesters RNF168 from cellular DSBs, disrupting repair [41]. 53BP1 localizes to viral replication foci upon differentiation [29], indicating that RNF168 is active on viral chromatin. RNF168 is a rate-limiting component in the recruitment of DDR factors to DSBs and is required specifically for productive replication of HPV31 [[41], [42], [43]]. The E7-RNF168 interaction may serve to direct RNF168 ubiquitin machinery to viral DNA, facilitating the recruitment of BRCA1 and subsequently Rad51 to facilitate repair. Overall, the studies highlight that HPV employs multiple mechanisms to ensure the recruitment of HR factors to viral DNA and the amplification of viral genomes upon differentiation.

The ATR/Chk1 pathway is also constitutively active in high-risk HPV-infected cells, which may occur due to replication stress induced by E7 [27,28,[43], [44], [45], [46]]. However, ATR DDR signaling components (e.g., γH2AX, ATRIP, and TopBP1) accumulate at sites of transient viral replication in a manner dependent on the E1 viral helicase [43], indicating that replication stress occurs during the initial amplification of viral genomes. In contrast to ATM, the ATR/Chk1 pathway is essential the stable maintenance of viral episomes in undifferentiated cells as well as productive viral replication following differentiation [[45], [46], [47]]. HPV31 exploits activation of the ATR/Chk1 pathway to maintain high levels of the transcription factor E2F1 upon differentiation, which drives expression of genes involved in entry into S phase as well as DNA repair [46]. Downstream of ATR/Chk1 activity, E2F1 promotes the expression of RRM2, the small subunit of the ribonucleotide reductase complex, which is the rate limiting factor for the de novo synthesis of dNTPs [48,49]. Increased RRM2 expression is critical for tolerance to persistent replication stress [49]. In HPV31-positive cells, the ATR/Chk1/E2F1/RRM2 pathway is necessary for the maintenance of nucleotide pools for viral replication [46]. Activation of this pathway occurs in an E7-dependent manner [46,50]. These results suggest that E7-mediated cell cycle re-entry leads to replication stress and activation of the ATR/Chk1/E2F1 response, which HPV then commandeers to maintain E2F signaling, tolerate replication stress and create an environment conducive to productive viral replication [51]. Additionally, E7 increases levels of numerous DNA repair factors [52], which may also occur through activation of the ATR/Chk1/E2F1 pathway [53].

4. HPV proteins modulate DDR pathways and interact with DNA repair proteins

Several HPV proteins have been implicated in activating DDR pathways. Expression of the E1 helicase as well as E2 from episomal viral copies can initiate replication from integrated viral origins of replication, resulting in an “onion-skin” type of replication [54]. This mode of replication generates aberrant DNA structures that activate the DDR and recruits ATM pathway components to sites of integrated HPV, including the MRN complex, Chk2, and γH2AX [54]. Additionally, the overexpression of E1 from different HPV types in keratinocytes induces cell cycle arrest in S- and G2-phases and activates an ATM-dependent DDR [28,55]. ATM activation requires the origin-binding domain and ATPase activities of E1 and most likely results due to the non-specific binding of E1 to cellular DNA in the absence of E2. In the presence of E2, E1 and E2 form nuclear viral replication centers, which recruit multiple DNA repair factors, such as phosphorylated ATM (pATM), γH2AX, Chk2, and MRN components [[54], [55], [56]]. Additionally, two components of the ATR response, Chk1 and TopBP1, are also recruited to these replication foci [43]. These studies indicate ATM and ATR activation in the early phases of infection is triggered, at least in part, by replication stress occurring during establishment replication.

Several studies suggest that TopBP1, a critical upstream activator of ATR, plays a key role in mediating E1-E2 initiation of replication from the viral origin, which may generate aberrant DNA structures and activate the DDR [[57], [58], [59], [60]]. E1 and E2 can independently interact with TopBP1 [58,59], and HPV16 E2 mutants compromised in TopBP1 interaction fail to establish viral episomes in primary human keratinocytes [57,60]. In addition, TopBP1 localizes to E1-E2 replication complex, and TOPBP1 depletion by small hairpin RNAs leads to the failure to form E1-E2 replication foci. These studies suggest that TopBP1 may mediate E1/E2-dependent initiation of replication and response to the DDR.

E7 may contribute to the establishment of a replication-competent environment by regulating ATM and ATR activation [24]. Expression of E7 induces ATM as well as ATR/Chk1 activity in a STAT5-dependent manner through an increase in Tip60 and TopBP1, respectively [45,61], and the expression of E7 alone is sufficient to induce activation of ATM, Chk1, and Chk2 upon epithelial differentiation [25,27]. Additionally, E7 interacts with pATM and NBS1, though the impact of these interactions on modulation of the DDR or viral replication is currently unclear [27,30]. High-risk HPV E6 and E7 can trigger oncogene-induced replication stress through improper re-entry into the cell cycle, which may lead to replication fork collapse, DSB formation, and the activation of the ATR and ATM pathways [44,62]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that HPV proteins modulate DDR pathways to facilitate viral replication through multiple mechanisms.

5. Use of DDR pathways by HPV for replication may drive oncogenesis

While DDR activation can facilitate viral replication by providing necessary DNA repair factors, DDR activation can also interfere with normal cellular processes that contribute to genomic instability and the initiation of cancer development. HPV-associated cervical cancers often exhibit integration of high-risk HPV DNA into cellular DNA, and frequently the integration of viral genomes occurs in close proximity to common fragile sites, which are particular regions on chromosomes that are vulnerable to replication stress and DNA damage [63]. Integration events can lead to abnormal expression of E6 and E7, which can promote the development of cancer by enhancing genomic instability [64]. HPV may also drive genomic instability through its ability to interfere with the repair of host DSBs. E6 and E7 can independently induce DNA damage and increase the frequency of integration of foreign DNA into the host genome [65,66]. Additionally, E7's sequestration of RNF168 from cellular DSBs may alter repair pathway choice, resulting in genomic instability [41]. In support of this, E7 has been shown to impair NHEJ repair by blocking DNA-PK activation, resulting in an increase in error-prone microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), which often marks sites of HPV integration into cellular DNA [67].

The activation of the ATM and ATR pathways initiates cell cycle checkpoints at S- and G2/M-phases [3]. However, E7 can abrogate these checkpoints through the degradation of the tumor suppressor pRb and by blocking the activities of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27, allowing uncontrolled cell proliferation and the persistence of damaged DNA into mitosis [[68], [69], [70], [71]]. The possibility of senescence or apoptosis upon abnormal entry into S-phase and induction of DNA damage is significantly reduced by the ability of E6 to degrade p53 as well as E7's ability to target Rb for degradation [72,73]. Additionally, E7 facilitates replication stress tolerance and bypasses oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) through an increase in the levels of the histone demethylase KDM6A [74]. KDM6A epigenetically de-represses p21 expression through the removal of repressive H3K27me3 marks. p21 suppresses replication stress by binding to PCNA and inhibiting cellular DNA replication [75]. The ability of E7 to abrogate p21's inhibition of CDK2 allows infected cells to remain active in the cell cycle and survive in the face of persistent replication stress [76,77]. These effects collectively lead to the accumulation of genetic mutations, chromosomal aberrations, and genomic instability, which are hallmarks of cancer development [2].

6. Merkel cell polyomavirus

Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) has a double-stranded, circular DNA genome contained in a non-enveloped capsid. MCPyV is found in at least 80 % of Merkel cell carcinomas, which constitute an aggressive skin malignancy and typically occur on the sun-exposed areas of the skin [78]. While MCC is rare, MCPyV infection is generally considered ubiquitous in humans. In MCPyV-positive MCC tumors, the viral genome is present as clonal, integrated sequences within the host genome [79]. MCPyV genomes tend to integrate into open chromatin through non-homologous end joining at host DSBs or through microhomology-mediated break-induced replication [80]. Tumorigenesis is perpetuated by the continual expression of the small T (sT) and truncated large T (LT) oncoproteins, which are driven by the integrated viral promoter region [81]. In contrast to virus-negative MCC, which exhibit a UV mutational signature, virus-positive MCC are characterized by a low mutational burden [82]. Merkel cells are not believed to be the primary reservoir for MCPyV. Rather other dermal cells, specifically fibroblasts, may support viral replication to achieve high levels of viral particles and viral shedding [83].

Like HPV, the MCPyV genome is histone-associated and has a single replication origin. The 5.4 kb genome encodes two subsets of viral proteins, early and late, from bi-directional promoters near the origin that are transcribed in opposite directions. The early genes encode the full-length LT, sT, 57kd (57 kT), and alternate LT open reading frame (ALTO) tumor antigens expressed from an alternatively spliced common transcript [83]. LT has a primary role in promoting viral replication through its origin binding and helicase activity domains and through the recruitment of cellular DNA replication factors, including DDR factors [84]. LT also contains a pRB binding domain that aids in cellular transformation through the inactivation of pRB [85]. sT contains a protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) binding domain that promotes modulation of the cell cycle [86]. Independent of the PP2A domain, studies have also observed that sT aids LT in viral replication as well as cellular transformation, including through promoting the hyperphosphorylation of eIF4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), deregulating cap-dependent translation [87]. sT also affects gene expression in MCC cells by interacting with MYCL and the EP400 histone acetylase and chromatin remodeling complex [88]. Although much less is known about the function of 57 kT and ALTO, 57 kT may enhance some of the pro-oncogenic roles of LT, and ALTO can encode circular RNAs that may affect transcriptional regulation [84]. The late region encodes the major capsid protein VP1 and the minor capsid protein VP2. In between the early and late regions is the non-coding region, which contains the origin of replication [83].

7. MCPyV and the DDR

Like other DNA viruses, MCPyV uses the LT and sT oncoproteins to manipulate cellular processes and facilitate viral replication [89]. While there is still much unknown about the role of the DDR during MCPyV infection, several studies have shed light on interactions between the virus and DDR pathways. MCPyV infection with virions or transfection of viral DNA robustly induces ATM and ATR activation, and LT expression alone is sufficient to elicit this response [90]. Interestingly, activation of ATM leads to the phosphorylation of LT in the C-terminal domain on Ser816 (pLT) [91]. ATM-dependent phosphorylation of full-length LT contributes to decreased cellular proliferation and increased apoptosis, accompanied by p53 activation. ATM activity may be necessary to establish an S-phase environment for viral replication but at the same time prevents uncontrolled cellular growth. As a result, MCPyV-positive MCCs typically carry a truncated LT with the C-terminal DNA-binding and helicase domains removed but retains the N-terminal pRb binding domain [89]. An additional study demonstrated a role for ATM and ATR activity in MCPyV DNA replication [92]. Components of both ATM and ATR DDR pathways, including ATM, Chk2, NBS1, ATR, Chk1, RPA32, and γH2AX, colocalize with LT-positive nuclear foci, and several of these factors also localize to active regions of viral DNA replication. Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown or inhibition of ATM/ATR reduces MCPyV replication [92]. The expression of sT in MCPyV-positive MCC cells is also sufficient to activate the DDR. Overexpression of sT leads to increased γH2AX levels and activation of the ATM pathway as evidenced by phosphorylation of ATM, 53BP1, and Chk2 in HEK293 cells [93]. Currently, how LT and sT activate DDR pathways as well as what effect activation of the DDR has on tumorigenesis is unclear. However, sT has been shown to induce genomic instability through interacting with E3 ubiquitin ligases, resulting in the formation of supernumerary chromosomes, increased aneuploidy and chromosomal breakage [94]. Treatment of MCPyV-positive MCC with ATR, ATM, or DNA-PK inhibitors alone does not induce cell death; however, the use of DDR inhibitors in coordination with low-dose radiation may serve as a promising avenue for MCC therapy [95]. As with other DNA viruses that closely rely on host DNA replication machinery, it is evident that MCPyV requires the activation of DDR pathways to facilitate the creation of a cellular environment conducive to viral replication and directly promote the integrity of nascent viral genomes. However, there is still much to learn regarding how MCPyV's manipulation of DDR pathways contributes to viral replication and the consequences on host genomic instability and MCC development.

8. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)

KSHV, or human gamma-herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), is a double-stranded DNA virus that is associated with multiple human cancers, including the endothelial neoplasm Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) and the lymphoproliferative disorders primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and multi-centric castleman's disease [96]. As with other herpesviruses, KSHV has a biphasic life cycle, consisting of a latent and lytic replication state. KSHV establishes a life-long infection due to its ability to establish latency in B-cells and endothelial cells. Although KSHV-associated tumors consist predominantly of latently infected cells, a small fraction of cells undergoing spontaneous lytic reactivation are thought to contribute to tumorigenesis in a paracrine manner through the secretion of cytokines and angiogenic factors that impact latently infected cells and induce an inflammatory environment [97].

In the virion, the viral genome is linear and devoid of histones. However, upon de novo infection, the viral genome circularizes and is rapidly chromatinized [98,99]. Upon de novo infection, KSHV enters the latent phase, where few viral genes are expressed, including the latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), viral FLICE inhibitory protein (vFLIP), vIRF3, viral cyclin (v-cyclin), Kaposin, and 12 viral miRNAs, and no virions are produced [100]. Multiple copies of the viral genome are maintained, and viral replication occurs in sync with the cell cycle. Disruption of latency activates the lytic cycle, which is characterized by the expression of the full repertoire of lytic genes and the production of new virions. During the lytic phase, viral replication occurs in a rolling circle mechanism that generates long head-to-tail concatemers of viral genomes that are cleaved into individual units for packaging [101]. Several studies have identified a role for DDR activation during both the latent and lytic phases of viral replication.

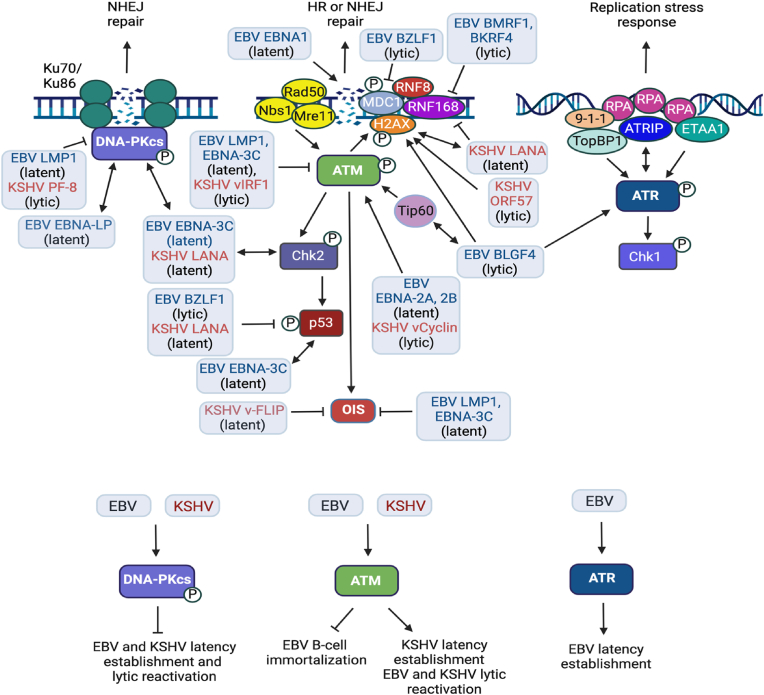

9. The role of the DDR in the establishment of KSHV latency

KSHV engages the DDR as a mechanism to establish latency both in endothelial cells and B-cells (Fig. 3). De novo KSHV infection of endothelial cells rapidly activates an ATM-dependent DDR characterized by the phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX), Chk2, Chk1 and BRCA1 [102]. Inhibition of ATM activity reduces H2AX phosphorylation and LANA expression, resulting in a significant decrease in the formation of LANA puncta, a marker of latency establishment [102]. γH2AX colocalizes with LANA at KSHV DNA foci and is bound to the terminal repeats (TRs) [103], which can function as a replication origin during latency [104,105]. LANA directly interacts with H2AX, and H2AX depletion results in decreased binding of LANA to the TRs and a reduction in viral copy number [102,103]. These results indicate that H2AX plays a role in tethering LANA to the viral genome and contributes to LANA-mediated episome persistence. De novo KSHV infection of B-cells also results in the activation of ATM and the phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX) [103]. LANA has also been reported to interact with the ATM target Chk2 to deregulate cell cycle control during latency [106]. In addition to H2AX, the DNA repair factor PARP1 (Poly ADP-Ribose Polymerase 1) has been reported to bind to the TRs and regulate latent replication through catalyzing the post-translational polymerization of ADP-ribose units onto LANA [107,108]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that the ATM-dependent DDR is critical for the initial stages of KSHV infection and establishment of viral latency. How ATM is activated upon infection is unclear but may occur in response to nicks and gaps that are present in the incoming KSHV genome [102]. In contrast to ATM/ATR activation, DNA-PKcs as well as Ku70, both effectors of NHEJ repair, negatively regulate KSHV latency, possibly by interacting with LANA [109]. LANA is a target for phosphorylation by DNA-PK, but how this impacts LANA's function is currently unclear. Overexpression of Ku70 as well as inhibition of DNA-PK activity blocks KSHV transient replication, indicating that the DNA-PK/Ku70 complex negatively affect LANA-associated activity in latent replication [109].

Fig. 3.

Interplay between KSHV, EBV and the DNA damage response. The latent and lytic phases of the KSHV and EBV life cycle each involve commandeering DDR pathways for viral replication as well as disrupting the repair of cellular DSBs, which contributes to genomic instability. KSHV establishes latency in endothelial cells as well as B-cells. EBV primarily establishes latency in memory B-cells but can also establish latency in epithelial cells. De novo KSHV infection of B-cells and endothelial cells induces ATM activation, which is required for the establishment of latency. LANA interacts with γH2AX, which is needed for LANA-mediated persistence of KSHV episomes. Additionally, LANA bypasses cell cycle arrest and apoptosis associated with the DDR by interacting with the ATM effector Chk2 and by blocking the function of p53, respectively. De novo EBV infection of primary B-cells also results in DNA damage and ATM activation due to hyperproliferation driven by the latent proteins EBNA-2A and -2B. ATM activity is ultimately blocked by the latent protein EBNA-3C, allowing for B-cell immortalization and lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) outgrowth. In contrast, ATR activity is required for B-cell immortalization upon de novo EBV infection. ATM activity is required for both KSHV and EBV lytic replication, and numerous DDR factors localize to sites of viral replication (see text for details). KSHV and EBV lytic proteins contribute to ATM activation, including BGLF4 (EBV) and v-cyclin (KSHV) v-cyclin. While DNA-PK serves as a restriction factor for latent and lytic replication of KSHV and EBV, both viruses encoded proteins that block DNA-PK activation. Several KSHV and EBV proteins induce DNA damage and modulate DNA repair to cause genomic instability. EBNA1 induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative DNA damage. Additionally, EBNA1 directly causes cellular DSBs by binding to DNA. KSHV LANA (latent) and EBV BKRF4 (lytic) prevent RNF168 recruitment to cellular DSBs, disrupting NHEJ and possibly HR repair. Additionally, EBV BZLF1 (lytic) disrupts cellular DSB repair by blocking the MDC1-RNF8 interaction at damaged DNA. KSHV ORF57 (lytic) causes genomic instability by inducing DSBs through the formation of R-loops. EBV and KSHV proteins also induce replication stress and DSBs that activate ATM, resulting in OIS. However, both viruses can bypass OIS through the actions of viral proteins, including LMP1 and EBNA-3C for EBV, and vFLIP for KSHV. KSHV (e.g., vIRF1) and EBV (e.g., LMP1, EBNA-3C) proteins also attenuate DDR pathway activation, further contributing to the disruption of cellular DSB repair and genomic instability. Created using BioRender.com.

The maintenance of KSHV latency also requires DDR factors. Cytoplasmic localization of the MRN components MRE11 and RAD50 promotes KSHV latency by activating NF-κB in response to cytoplasmic DNA, which occurs during herpesvirus infections [110,111]. NF-κB has been reported to promote latency by blocking lytic gene expression [112,113]. Interestingly, however, while nuclear LANA promotes latency, cytoplasmic variants of LANA promote lytic reactivation by interacting with MRE11 and RAD50, in turn blocking NF-κB activation and activating lytic gene expression [110]. Cytoplasmic LANA also promotes lytic reactivation by interfering with the activity of the cytoplasmic DNA sensor, cGAS, in turn blocking a type I IFN response [114].

10. The role of the DDR in KSHV lytic replication

KSHV undergoes spontaneous lytic reactivation sporadically throughout the lifetime of the host, though the signals that elicit reactivation are not well understood [100]. RTA serves as the major transactivator of the lytic phase, and viral genes are expressed in a temporal manner (e.g., immediate early, early, late), allowing for viral replication and the production of new virions [100,115,116]. Multiple oncogenes are expressed during the lytic replication cycle, which facilitate a replication competent environment by altering signaling pathways commonly associated with oncogenesis, including metabolism, survival, immune evasion as well as the DDR [2]. Similar to latent infection, lytic reactivation is accompanied by an increase in DNA damage and DDR activation in B-cells as well as endothelial cells [117,118].

Lytic reactivation in RTA-inducible KSHV-infected B-cells results in ATM, ATR and DNA-PK activation, and subsequent phosphorylation of downstream substrates, including γH2AX [119] (Fig. 3). DDR activation is also observed upon lytic reactivation of KSHV in endothelial cells [119]. Interestingly, during lytic replication the ATR substrates RPA and NBS1 are phosphorylated, while Chk1 is not [119]. Whether this is a deliberate strategy of KSHV to disable signaling to certain ATR substrates is currently unclear. DDR activation does not require amplification of viral DNA or late lytic gene expression, indicating that early or immediate early gene expression drives DNA damage signaling [119]. In support of this, Jackson et al. demonstrated that expression of the early lytic gene ORF57 is sufficient to induce DDR activation [117] (Fig. 3). ORF57 is a multifunctional protein that facilitates all stages of viral mRNA processing [120]. ORF57 sequesters the cellular mRNA export hTREX complex at viral RNAs, resulting in cellular DSB formation and genomic instability through the formation of co-transcriptional RNA-DNA hybrids (R-loops) [117,121].

The DSB sensing complexes MRN and Ku70 consistently localize to sites of KSHV lytic replication [119]. Downstream DDR factors, however, including γH2AX, MDC1 and 53BP1, form foci adjacent to viral replication centers, representing sites of cellular DNA damage. HR factors are also not consistently detected at viral replication centers [119]. Interestingly, ATM and ATR kinase activity as well as MRE11 nuclease activity are required for lytic replication [119], though how these DDR factors contribute to viral replication is unclear. In contrast, inhibition of DNA-PK or depletion of Ku70 results in increased amplification of viral DNA [122], indicating a restrictive role for NHEJ in lytic replication as well as latent replication. Collectively, these findings suggest that DDR proteins play an important role in the KSHV lytic replication process and may represent a potential target for antiviral therapies.

11. Latent and lytic KSHV proteins contribute to genomic instability

DNA damage and modulation of the DDR can lead to host genomic instability, one of the most common hallmarks of cancer that is an enabling characteristic of tumorigenesis [123]. KSHV induces signaling pathways associated with the hallmarks of cancer, but rarely promotes transformation, indicating that other genetic alterations must take place [2]. Indeed, multiple studies have shown that KSHV-infected cells as well as KSHV-associated tumors exhibit chromosomal instability [[124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129]], allowing the accumulation of additional genetic alterations that drive KSHV tumor progression. KSHV is predominantly latent in associated tumors; however, spontaneous lytic reactivation is thought to contribute to tumorigenesis in a paracrine manner [130]. Both latent and lytic KSHV oncogenes induce genomic instability through effects on the cell cycle as well by as interfering with cellular DNA repair. Moreover, KSHV can modulate the DNA damage response to evade immune surveillance, allowing the virus to persist in a latent state and promote tumorigenesis [131].

LANA directly interacts with p53 and Rb, disrupting normal DNA damage signaling and promoting proliferation and cell survival to support viral replication. Establishment of a replication-competent environment, in turn, contributes to the development and maintenance of KSHV-associated tumors [[132], [133], [134]]. LANA has been reported to induce genomic instability by interacting with and promoting the degradation of the mitotic spindle checkpoint protein Bub1, resulting in micronuclei formation and multinucleation [135]. LANA may also contribute to genomic instability by impeding the repair of cellular DSBs. LANA interferes with the binding of RNF168 to H2A at cellular DSBs, in turn blocking the recruitment of 53BP1 to promote NHEJ repair and may also impact the recruitment of BRCA1-BARD1 to promote HR repair [11,136]. The latency protein v-cyclin, a structural homolog to cellular D type cyclins, may also contribute to DNA damage and genomic instability. V-cyclin forms an active kinase complex with cellular CDK6, which phosphorylates Rb, resulting in unscheduled entry into S-phase and replication stress that triggers ATM activation and OIS in telomere-immortalized endothelial cells [[137], [138], [139]] (Fig. 3). However, v-FLIP blocks v-cyclin-induced OIS by suppressing autophagy, allowing for the growth and proliferation of latently infected cells [140]. ATM DDR activation is predominantly observed in early stage KS lesions, suggesting that the DDR serves as an anti-cancer barrier that may enforce selective pressure for mutations that bypass this response [139]. V-cyclin-induced DDR activation may confer a barrier against tumorigenesis in KSHV-infected cells during the early stages of infection. However, v-cyclin induced oncogenic stress could cause genomic instability that contributes to the onset of carcinogenesis.

In KSHV-associated tumors, lytic infection cannot sustain the malignant phenotype as these cells are destined to die. However, early events in primary infection involve the expression of latent as well as lytic viral genes [141]. As mentioned above, lytic replication directly triggers DSBs, a significant cause of genome instability [117,118]. The induction of DNA damage early in infection by lytic proteins such as ORF57, prior to the establishment of latency or during abortive lytic replication, may give rise to a background of genomic instability in premalignant lesions [118]. The lytic protein vIRF1 may also contribute to the accumulation of mutations and chromosomal errors by suppressing ATM-dependent activation of p53 to block DNA-damage-induced apoptosis, and by activating ROS production, which can result in oxidative DNA damage, respectively [142,143]. Additionally, the lytic viral processivity factor PF-8 may contribute to genomic instability by blocking the interaction between the Ku complex and DNA-PKcs, impairing NHEJ repair of cellular DSBs [118]. PF-8 also targets PARP1 for degradation to promote lytic reactivation [144]. Overall, the dysregulation of the DNA damage response by KSHV is a critical factor in promoting tumorigenesis, and further understanding these mechanisms will provides insight into the development of therapeutic strategies targeting KSHV-associated cancers.

12. Epstein-Barr virus

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a gamma-herpesvirus originally identified in an African (endemic) Burkitt's lymphoma (BL). EBV has since come to be associated with several cancers, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and some gastric cancers as well as certain lymphomas, and is associated with 1.5 % of human cancers [145]. EBV is transmitted through saliva where the virus is thought to first infect epithelial cells. Newly synthesized virions released from epithelial cells then encounter circulating B-cells, the primary cell type that supports EBV latency and lytic reactivation. Persistence of the virus occurs in memory B-cells. Although EBV latency can be established in epithelial cells, this process is thought to require pre-existing genetic alterations [146,147]. Similarly to other DNA tumor viruses, viral genes are expressed in a manner to manipulate cellular processes in order to promote viral replication and the production of viral progeny [145].

As with other herpesviruses, EBV employs a replication strategy involving a period of latent infection, where minimal viral protein expression occurs, and a lytic stage, which results in the production of numerous viral progeny [148]. EBV has an approximately 172 kb linear double-stranded DNA genome that potentially encodes 80 proteins during lytic replication; however, not all of the genes are well characterized. The EBV genome also encodes several small untranslated RNAs during the lytic cycle. An additional eight viral genes (described below) are expressed during different phases of the latency program. In the capsid, the EBV genome is linear, unmethylated and histone-free. However, during the latent phase, EBV genomes are circularized via HR of the terminal repeats and become CpG methylated as well as histone-associated to mimic host chromatin and to regulate viral gene expression [149]. Replication of the EBV genome during the latent phase occurs from the plasmid origin of replication (oriP) concomitantly with replication of chromosomal DNA [150].

The EBV latency program is responsible for the establishment of infection and has been best studied in B-cell lymphomas, which is modeled by the generation of lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) from infection of primary B-cells in vitro. Latency is divided into four subtypes based on the viral gene expression pattern: latency 0, I, IIa, III [145]. Upon infection, eight viral genes, including the nuclear proteins EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, LP and latent membrane proteins LMP1, 2A, and 2B, and several non-coding RNAs (e.g., EBERS, BARTS) are expressed in LCLs during latency III, also known as the growth program. The Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen leader protein (EBNA-LP) and EBNA2 are the first EBV proteins produced during EBV infection. Both EBNA2 and EBNA-LP are critical to the transcriptional activation of other latent phase proteins as well as initial modulation of host cell gene expression. Another latent protein EBNA1 coordinates localization of cellular DNA replication machinery to the oriP, and EBNA1 promotes episomal maintenance through facilitating viral replication and partitioning of viral genomes to daughter cells [151]. EBNA1 is expressed throughout the latency program, and while not required for the generation of LCLs, EBNA1 significantly enhances the efficiency of LCL formation [152]. The latency IIa program involves the expression of only EBNA1, LMP1, and LMP2 and is believed to encompass the period of B-cell maturation in the germinal centers [145]. Finally, the EBV life cycle can enter periods of no viral gene expression, referred to as latency 0, or only the expression of EBNA1, called latency I, which may primarily function in memory B-cell populations to maintain viral genomes. EBV latency programs are also observed to occur during EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders, including EBV-associated cancers, with latency III being common in immunocompromised individuals, and latency I and II in immunocompetent individuals [153].

Latently infected B-cells periodically undergo lytic reactivation [148]. The lytic viral phase is divided into three stages based on gene expression: immediate-early, early, and late, with replication requiring early gene expression. The immediate-early viral transactivators BZLF1 (Zta) and BRLF1 (Rta) control lytic gene expression. During the lytic viral phase, EBV genomes are amplified from two copies of the oriLyt. Replication from the episomal genomes occurs by rolling circle replication, forming long concatemers that are cleaved into linear viral genomes [150]. In addition to BZLF1 and BRLF1, six other lytic phase proteins function at OriLyt to ensure DNA replication, including BALF5 (DNA polymerase catalytic subunit), BALF2 (ssDNA-binding protein), BMRF1 (DNA polymerase processivity factor), BBLF4 (DNA helicase), BSLF1 (primase), and BBLF2/3 (primase-associated factor). Following replication, late genes are expressed, which promote the encapsidation of linear viral genomes and the release of viral particles [148]. Recent studies have shown that both latent and lytic genes are involved in activating the DDR and may contribute to host cell transformation, which we review below

13. The role of the DDR during EBV establishment and latency

Several studies have found that the ATM and ATR DDR is activated during a period of hyperproliferation induced by de novo EBV infection of primary B-cells. Activation of the ATM-dependent DDR occurs due to increased DSBs that result from an unscheduled entry into the cell cycle, culminating in cell cycle arrest and senescence [154]. Inhibition of ATM and/or Chk2 markedly increases the efficiency of LCL formation, indicating that DDR activation acts as a barrier to transformation [154]. EBV infection of primary B-cells also triggers activation of the ATR/Chk1 pathway due to replication stress induced by reduced nucleotide pools [155,156]. Early proliferating EBV-infected B-cells are more sensitive to ATR and Chk1 inhibition, and LCL formation is significantly inhibited [155]. These results indicate that in contrast to ATM, early proliferating EBV-infected B-cells rely on the ATR-dependent replication stress response for survival and outgrowth. Following the initial period of hyperproliferation, which is induced by EBNA-LP and EBNA2, EBNA-3C is required to limit the DDR, facilitating survival and outgrowth of LCLs [154,157] (Fig. 3). EBNA-3C has been shown to disrupt the G2/M checkpoint by interacting with the ATM effector Chk2 and may also mitigate the growth restriction of EBV-infected primary B-cells by downregulating levels of the p16INK4a tumor suppressor [158]. Additionally, EBNA-3C interacts with p53 and substantially represses its transcriptional activity in LCLs in part by reducing the ability of p53 to bind DNA [159]. While much less is known about the role of the DNA-PK pathway during EBV infection, EBNA-LP has been observed to interact with DNA-PKcs, which leads to the DNA-PKcs-mediated phosphorylation of p53 as well as EBNA-LP itself [160] (Fig. 3).

The formation and maintenance of EBV DNA as an episome in host cells is vital to viral replication and contributes to B-cell transformation. Members of the MRN complex, MRE11 and NBS1, associate with OriP during S-phase and potentially promote the formation of replication-associated recombination junctions, which may allow segregation of the replicated episomes [161]. In the absence of MRE11 or NBS1, EBV episomes are not maintained, and in a patient-derived NBS1-mutated LCL, EBV genomes were found integrated into host cell DNA [161].

14. The role of the DDR during EBV lytic reactivation

Several studies indicate that EBV manipulates DDR pathways during the lytic phase. In contrast to latent infection, ATM activity is necessary for lytic reactivation [162] (Fig. 3). EBV lytic infection triggers the activation of an ATM-dependent DDR, with phosphorylated ATM as well as members of the MRN complex localizing to sites of lytic viral replication [163,164]. Additionally, MRE11 and RPA, along with the HR factors Rad51 and Rad52, are loaded onto newly synthesized genomes [163]. Depletion of Rad51 or Rad52 blocks viral genome synthesis, indicating a requirement for HR in lytic viral replication [164]. Interestingly, Bailey et al. showed that BZLF1 interacts with the NHEJ mediator 53BP1, and that 53BP1 is required for lytic replication [165]. How 53BP1 contributes to viral replication is currently unclear. ATM activity is required for lytic replication in BL, NPC and gastric carcinoma cells [166]. Interestingly, lytic reactivation leads to an increase in p53, which has been reported to enhance viral replication [167,168]. However, BZLF1 overcomes p53 activity upon lytic reactivation through multiple mechanisms [169,170], including promoting p53 degradation by interacting with the ECS ubiquitin ligase complex [171]. Disruption of p53 signaling may allow the virus to replicate in an extended S-phase environment [164].

Several EBV lytic proteins have been shown to support ATM activation (Fig. 3). Li et al. showed in BL cells that the early lytic protein BGLF4, a serine/threonine kinase, triggers ATM activation by binding to and phosphorylating/activating the histone acetyltransferase TIP60 [172,173]. Tip60 localizes to the oriLyt promoter, and inhibition of ATM as well as depletion of Tip60 reduces EBV lytic reactivation. γH2AX increases at several regions in the EBV genome in lytic reactivation, which may occur through BGLF4, which is known to induce H2AX phosphorylation [174,175]. BGLF4 also induces activation of ATR [173]. The phosphorylation of ATM, H2AX and 53BP1 occurs early in the pre-replicative lytic phase and does not require viral replication [176]. Furthermore, the expression of BZLF1 is sufficient to induce ATM activation upon lytic reactivation in a DNA binding-dependent manner [176].

The late lytic gene BPLF1 functions as a ubiquitin and NEDD8 deconjugase and is important for viral DNA synthesis [177]. BPLF1 has been reported to recruit the specialized DNA repair polymerase Pol η to EBV genomes, which repairs damaged viral DNA [178]. In response to DNA damage, the ubiquitination of PCNA recruits Pol η, allowing for the replication of damaged DNA [179]. Interestingly, BPLF1 has been observed to deubiquitinate PCNA and disrupt cellular DNA repair at stalled replication forks following UV treatment or hydroxyurea treatment [178]. Whether BPLF1 disrupts PCNA ubiquitination at cellular sites of DNA damage to allow for recruitment of Pol η to damaged viral genomes is currently unclear.

Several studies have shown that EBV attenuates DDR signaling at sites of cellular DNA damage by preventing histone ubiquitylation and RNF168 recruitment to DSBs through the actions of several lytic viral proteins [[180], [181], [182]] (Fig. 3). The BZFL1 immediate early protein has been reported to impair DSB signaling by preventing the recruitment of RNF8 to DNA damage sites by blocking the MDC1-RNF8 interaction, suppressing 53BP1 accumulation at DNA damage sites [180]. The early lytic protein BMRF1, the DNA polymerase processivity factor, interferes with the DDR by inhibiting RNF168 recruitment and histone ubiquitination at DSBs through interacting with the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation (NURD) complex [182], while the BKRF4 tegument protein prevents the recruitment of RNF168 to DSBs by directly binding histones [181]. BKRF4 is expressed throughout viral infection and is thought to play a role in silencing the DDR in both the lytic and latent phases [183].

15. EBV induces DNA damage and genomic instability

Tumor cells of EBV-associated cancers are derived from infected cells that express a small subset of latency genes. The latent proteins EBNA1, EBNA-3C and LMP1 have been shown to induce DNA damage, DDR activation and genomic instability through independent mechanisms [184]. EBNA1's ability to induce DNA damage and genomic instability is attributed to the production of reactive oxygen species via transcriptional upregulation of Nox2, the catalytic subunit of the NADPH oxidase [184,185]. Additionally, a recent study showed that EBNA1 triggers breakage of chromosome 11q23 in a dose-dependent manner by binding to EBV-like 18bp palindromic sequences, inducing genomic instability that could contribute to EBV-associated cancers [186]. Importantly, whole genome sequencing revealed that 81 % of EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinomas exhibit an enrichment of chromosome 11 rearrangements [186]. Whether 11q23 breakage and rearrangements occur in other EBV-associated cancers has yet to be examined; however, this study supports a direct role for EBNA1 in cancer development. LMP1 has been reported to attenuate DNA repair by downregulating expression of ATM [184]. LMP1 also inhibits DNA-PKcs phosphorylation and activation [187]. EBNA-3C does not cause DNA damage or impair DNA repair, but rather disrupts the mitotic spindle checkpoint through decreasing the expression of Bub1R, resulting in aneuploidy [184]. EBNA-3C may also facilitate abnormal mitotic progression by bypassing the G2 checkpoint through interacting with Chk2 [188]. EBV-encoded microRNAs may also contribute to genomic instability by deregulating DDR activity. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, EBV encoded BART-microRNAs reduce ATM signaling and downregulate BRCA1 levels [189]. Furthermore, the activity of the BART miRNAs was shown to sensitize nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to DNA damage inducing drugs, including cisplatin and doxorubicin.

Although EBV's latent phase is most commonly associated with EBV-associated malignancies, there is increasing evidence that the lytic phase contributes to EBV-mediated oncogenesis, similar to that of KSHV [190]. Lytic infection contributes to EBV's oncogenic potential through the regulation of tumorigenic properties, including immunomodulation and immune evasion, angiogenesis and invasion, cell cycle and apoptosis, as well as genomic instability [191]. Lytic reactivation in NPC as well as BL lines results in increased DNA damage and DDR activation [192]. In BL cells, lytic reactivation is associated with markers of genomic instability, including increased centriole formation, formation of micronuclei and multinucleation [193]. Similarly to KSHV, de novo EBV infection results in transient expression of immediate early and early lytic genes prior to the establishment of latency, and several studies using SCID and humanized mice have demonstrated that the early lytic phase contributes to lymphomagenesis [97,191,[194], [195], [196], [197]]. Additionally, the immediate early lytic protein BZLF1 as well as several early lytic proteins have been reported to induce DNA damage and genomic instability, including BALF3 (terminase), BGLF4 (S/T protein kinase), BGLF5 (exonuclease) [191]. Some late lytic genes have also been detected in BL, NPC and gastric carcinomas [191,198]. Since completion of the lytic phase leads to cell death, these results indicate that EBV-associated tumors harbor cells undergoing incomplete or abortive lytic infection, characterized by the expression of a limited subset of lytic genes and no production of viral particles [198]. However, the expression of late lytic genes in the absence of early genes involved in viral replication suggests that viral gene expression may be differentially regulated in EBV-associated tumors. An increased understanding of how lytic proteins contribute to the development and maintenance of EBV-associated tumors through the induction of DNA damage and the accumulation of chromosomal instability may identify therapeutic targets for the treatment of EBV-associated cancers.

16. Conclusions

To establish an environment conducive to replication and persistence, viruses must manipulate the cellular environment. Here, we have discussed how HPV, MCPyV, KSHV and EBV regulate the PIKK signaling cascades of the cellular DDR to promote their respective life cycles. DNA tumor viruses impinge on the DDR on several levels. Viral genomes may activate the DDR due to formation of aberrant DNA structures. Viral genome amplification may also result in replication stress and damage that activates the DDR, resulting in the recruitment of repair factors to viral DNA. Despite the potential detrimental effects of the DDR, viruses use aspects of DDR signaling to promote viral replication, while blocking components that would be inhibitory. Viral proteins can directly or indirectly affect the DDR through effects on the cell cycle, apoptosis, replication, and transcription. Viral oncoprotein expression is linked to DDR activation through the need to provide an S-phase environment for viral replication, resulting in cellular replication stress. Viral proteins can also directly interact with components of the DDR, modulating DDR responses. Consequently, viral modulation of DDR pathways can lead to disruption of cellular DNA repair, culminating in genomic instability that predisposes infected cells to transformation. A further understanding of the mechanisms by which DNA tumor viruses interface with DDR pathways may reveal novel mechanisms of genomic instability as well as expose vulnerabilities in DSB repair that can be exploited to disrupt viral replication and treat virus-associated cancers.

Author statement

Cary Moody, Michelle Mac and Caleb Studstill conceptualized, wrote and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Moody lab for helpful discussions. Work on human papillomaviruses in the Moody lab was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Ciccia A., Elledge S.J. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 2010;40(2):179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. PubMed PMID: 20965415; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2988877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesri E.A., Feitelson M.A., Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15(3):266–282. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.011. Epub 2014/03/19. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.011. PubMed PMID: 24629334; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3992243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackford A.N., Jackson S.P. ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK: the trinity at the heart of the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. 2017;66(6):801–817. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.015. PubMed PMID: 28622525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scully R., Panday A., Elango R., Willis N.A. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20(11):698–714. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0152-0. Epub 2019/07/03. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0152-0. PubMed PMID: 31263220; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7315405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hustedt N., Durocher D. The control of DNA repair by the cell cycle. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb3452. Epub 2016/12/23. doi: 10.1038/ncb3452. PubMed PMID: 28008184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groelly F.J., Fawkes M., Dagg R.A., Blackford A.N., Tarsounas M. Targeting DNA damage response pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2023;23(2):78–94. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00535-5. Epub 2022/12/06. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00535-5. PubMed PMID: 36471053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellegrino S., Michelena J., Teloni F., Imhof R., Altmeyer M. Replication-coupled dilution of H4K20me2 guides 53BP1 to pre-replicative chromatin. Cell Rep. 2017;19(9):1819–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.016. Epub 2017/06/01. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.016. PubMed PMID: 28564601; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5857200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fradet-Turcotte A., Canny M.D., Escribano-Diaz C., Orthwein A., Leung C.C., Huang H., et al. 53BP1 is a reader of the DNA-damage-induced H2A Lys 15 ubiquitin mark. Nature. 2013;499(7456):50–54. doi: 10.1038/nature12318. Epub 2013/06/14. doi: 10.1038/nature12318. PubMed PMID: 23760478; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3955401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escribano-Diaz C., Orthwein A., Fradet-Turcotte A., Xing M., Young J.T., Tkac J., et al. A cell cycle-dependent regulatory circuit composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP controls DNA repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. 2013;49(5):872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.001. Epub 2013/01/22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.001. PubMed PMID: 23333306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta R., Somyajit K., Narita T., Maskey E., Stanlie A., Kremer M., et al. DNA repair network analysis reveals Shieldin as a key regulator of NHEJ and PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Cell. 2018;173(4):972–988 e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.050. Epub 2018/04/17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.050. PubMed PMID: 29656893; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8108093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker J.R., Clifford G., Bonnet C., Groth A., Wilson M.D., Chapman J.R. BARD1 reads H2A lysine 15 ubiquitination to direct homologous recombination. Nature. 2021;596(7872):433–437. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03776-w. Epub 2021/07/30. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03776-w. PubMed PMID: 34321663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura K., Saredi G., Becker J.R., Foster B.M., Nguyen N.V., Beyer T.E., et al. H4K20me0 recognition by BRCA1-BARD1 directs homologous recombination to sister chromatids. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21(3):311–318. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0282-9. Epub 2019/02/26. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0282-9. PubMed PMID: 30804502; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6420097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Densham R.M., Garvin A.J., Stone H.R., Strachan J., Baldock R.A., Daza-Martin M., et al. Human BRCA1-BARD1 ubiquitin ligase activity counteracts chromatin barriers to DNA resection. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23(7):647–655. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3236. Epub 2016/05/31. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3236. PubMed PMID: 27239795; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6522385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao F., Kim W., Kloeber J.A., Lou Z. DNA end resection and its role in DNA replication and DSB repair choice in mammalian cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020;52(10):1705–1714. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00519-1. Epub 2020/10/31. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00519-1. PubMed PMID: 33122806; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8080561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saldivar J.C., Cortez D., Cimprich K.A. The essential kinase ATR: ensuring faithful duplication of a challenging genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.67. PubMed PMID: 28811666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niedzwiedz W. Activating ATR, the devil's in the dETAA1l. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18(11):1120–1122. doi: 10.1038/ncb3431. PubMed PMID: 27784903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis A.J., Chen B.P., Chen D.J. DNA-PK: a dynamic enzyme in a versatile DSB repair pathway. DNA Repair. 2014;17:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.02.020. Epub 2014/04/01. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.02.020. PubMed PMID: 24680878; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4032623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham T.G., Walter J.C., Loparo J.J. Two-stage synapsis of DNA ends during non-homologous end joining. Mol. Cell. 2016;61(6):850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.010. Epub 2016/03/19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.010. PubMed PMID: 26990988; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4799494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobbs T.A., Tainer J.A., Lees-Miller S.P. A structural model for regulation of NHEJ by DNA-PKcs autophosphorylation. DNA Repair. 2010;9(12):1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.019. Epub 2010/10/30. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.019. PubMed PMID: 21030321; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3045832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammel M., Yu Y., Mahaney B.L., Cai B., Ye R., Phipps B.M., et al. Ku and DNA-dependent protein kinase dynamic conformations and assembly regulate DNA binding and the initial non-homologous end joining complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(2):1414–1423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065615. Epub 2009/11/07. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065615. PubMed PMID: 19893054; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2801267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang H., Yao F., Marti T.M., Schmid R.A., Peng R.W. Beyond DNA repair: DNA-PKcs in tumor metastasis, metabolism and immunity. Cancers. 2020;12(11) doi: 10.3390/cancers12113389. Epub 2020/11/20. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113389. PubMed PMID: 33207636; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7698146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBride A.A. Human papillomaviruses: diversity, infection and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022;20(2):95–108. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00617-5. Epub 2021/09/16. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00617-5. PubMed PMID: 34522050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McBride A.A. Mechanisms and strategies of papillomavirus replication. Biol. Chem. 2017;398(8):919–927. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2017-0113. PubMed PMID: 28315855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moody C. Mechanisms by which HPV induces a replication competent environment in differentiating keratinocytes. Viruses. 2017;9(9) doi: 10.3390/v9090261. PubMed PMID: 28925973; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5618027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banerjee N.S., Wang H.K., Broker T.R., Chow L.T. Human papillomavirus (HPV) E7 induces prolonged G2 following S phase reentry in differentiated human keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(17):15473–15482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.197574. PubMed PMID: 21321122; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3083224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studstill C.J., Moody C.A. For better or worse: modulation of the host DNA damage response by human papillomavirus. Annu Rev Virol. 2023 doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-111821-103452. 10 (1) 325–345. Epub 2023/04/12. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-111821-103452. PubMed PMID: 37040798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moody C.A., Laimins L.A. Human papillomaviruses activate the ATM DNA damage pathway for viral genome amplification upon differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000605. PubMed PMID: 19798429; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2745661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakakibara N., Mitra R., McBride A.A. The papillomavirus E1 helicase activates a cellular DNA damage response in viral replication foci. J. Virol. 2011;85(17):8981–8995. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00541-11. PubMed PMID: 21734054; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3165833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillespie K.A., Mehta K.P., Laimins L.A., Moody C.A. Human papillomaviruses recruit cellular DNA repair and homologous recombination factors to viral replication centers. J. Virol. 2012;86(17):9520–9526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00247-12. PubMed PMID: 22740399; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3416172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anacker D.C., Gautam D., Gillespie K.A., Chappell W.H., Moody C.A. Productive replication of human papillomavirus 31 requires DNA repair factor Nbs1. J. Virol. 2014;88(15):8528–8544. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00517-14. PubMed PMID: 24850735; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4135936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKinney C.C., Hussmann K.L., McBride A.A. The role of the DNA damage response throughout the papillomavirus life cycle. Viruses. 2015;7(5):2450–2469. doi: 10.3390/v7052450. PubMed PMID: 26008695; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4452914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chappell W.H., Gautam D., Ok S.T., Johnson B.A., Anacker D.C., Moody C.A. Homologous recombination repair factors Rad51 and BRCA1 are necessary for productive replication of human papillomavirus 31. J. Virol. 2015;90(5):2639–2652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02495-15. PubMed PMID: 26699641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberdoerffer P., Michan S., McVay M., Mostoslavsky R., Vann J., Park S.K., et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135(5):907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. PubMed PMID: 19041753; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2853975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang J., Cho N.W., Cui G., Manion E.M., Shanbhag N.M., Botuyan M.V., et al. Acetylation limits 53BP1 association with damaged chromatin to promote homologous recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20(3):317–325. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2499. PubMed PMID: 23377543; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3594358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langsfeld E.S., Bodily J.M., Laimins L.A. The deacetylase sirtuin 1 regulates human papillomavirus replication by modulating histone acetylation and recruitment of DNA damage factors NBS1 and Rad51 to viral genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005181. PubMed PMID: 26405826; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4583417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allison S.J., Jiang M., Milner J. Oncogenic viral protein HPV E7 up-regulates the SIRT1 longevity protein in human cervical cancer cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1(3):316–327. doi: 10.18632/aging.100028. PubMed PMID: 20157519; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2806013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong S., Dutta A., Laimins L.A. The acetyltransferase Tip60 is a critical regulator of the differentiation-dependent amplification of human papillomaviruses. J. Virol. 2015;89(8):4668–4675. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03455-14. PubMed PMID: 25673709; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4442364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mac M., DeVico B.M., Raspanti S.M., Moody C.A. The SETD2 methyltransferase supports productive HPV31 replication through the LEDGF/CtIP/Rad51 pathway. J. Virol. 2023;97(5) doi: 10.1128/jvi.00201-23. Epub 2023/05/08. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00201-23. PubMed PMID: 37154769; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC10231177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aymard F., Bugler B., Schmidt C.K., Guillou E., Caron P., Briois S., et al. Transcriptionally active chromatin recruits homologous recombination at DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21(4):366–374. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2796. Epub 2014/03/25. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2796. PubMed PMID: 24658350; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4300393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ceccaldi R., Rondinelli B., D'Andrea A.D. Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-strand break. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(1):52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.009. PubMed PMID: 26437586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sitz J., Blanchet S.A., Gameiro S.F., Biquand E., Morgan T.M., Galloy M., et al. Human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein targets RNF168 to hijack the host DNA damage response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116(39):19552–19562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906102116. Epub 2019/09/11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906102116. PubMed PMID: 31501315; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6765264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gudjonsson T., Altmeyer M., Savic V., Toledo L., Dinant C., Grofte M., et al. TRIP12 and UBR5 suppress spreading of chromatin ubiquitylation at damaged chromosomes. Cell. 2012;150(4):697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.039. Epub 2012/08/14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.039. PubMed PMID: 22884692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinson T., Toots M., Kadaja M., Pipitch R., Allik M., Ustav E., et al. Engagement of the ATR-dependent DNA damage response at the human papillomavirus 18 replication centers during the initial amplification. J. Virol. 2013;87(2):951–964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01943-12. PubMed PMID: 23135710; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3554080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bester A.C., Roniger M., Oren Y.S., Im M.M., Sarni D., Chaoat M., et al. Nucleotide deficiency promotes genomic instability in early stages of cancer development. Cell. 2011;145(3):435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.044. PubMed PMID: 21529715; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3740329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]