Abstract

Background

In recent years, flipped classrooms (FCs) have gained popularity in higher education, particularly among healthcare students. The FC model is a blended learning approach that combines online learning with in-class activity. This has prompted many instructors to assess how they teach and prepare successful graduate students for today's society. Additionally, colleges and universities have been challenged to deliver curricula that are relevant to the needs of students and to provide the rising skills and knowledge that are expected to be acquired by students.

Objective

This systematic review aims to evaluate the flipped classroom teaching approach in pharmacy education and to provide a summary of the guidance for the introduction and implementation of the flipped classroom model in pharmacy educational programs.

Method

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines. Eight databases were cross-screened by four reviewers, following key terms and predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A form was developed to extract relevant data from the reviewers. Qualitative data within the studies reporting students’ and educators’ perceptions and views on the FC model were also analyzed using a thematic analysis. Studies were appraised using the Medical Education Research Quality Instrument (MERSQI) and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for qualitative research.

Results

The reviewers screened 330 articles, of which 35 were included in the review. The themes identified were implementation, academic performance outcomes, student satisfaction with the flipped classroom model, and long-term knowledge retention. Most studies (68%) have found that flipped learning enhances students’ success and exam performance. Six (27%) studies reported no statistically significant difference in academic performance. However, two studies reported lower long-term knowledge retention in FC learning than in lecture-based learning. The students’ perceptions of the FC approach were assessed in 26 studies, and the majority reported positive feedback. However, some students found the pre-class homework difficult to complete before class, and some expressed dissatisfaction with the inconsistent grading and unclear assessment questions in the FC model. Overall, the FC model was found to enhance the students’ critical thinking and communication skills, self-confidence, and time management.

Conclusions

The findings of this review indicate that pharmacy students generally found the flipped classroom model preferable to traditional lectures. However, this preference is conditional on the effective implementation of this approach and alignment within the core instructional elements. The issue of increased workload for students associated with self-directed pre-class learning may present a challenge.

Keywords: Education research, Flipped classroom, Pharmacy education, Blended learning

1. Introduction

Several changes in students’ demographics, technological advances, and economic climate have affected current educational structures worldwide. This has prompted many instructors to assess how they teach and prepare successful graduate students to fit today's society. Additionally, colleges and universities have been challenged to deliver curricula that are relevant to the needs of students and to meet the demands of the rising skills and knowledge that are expected to be acquired by students (Arum and Roksa, 2011). However, many educational institutions have attempted to redesign their class model to achieve several goals: to focus more on application and skill development, such as critical thinking and communication skills that are considered core to higher education; providing students with greater control and a greater sense of responsibility for their learning; reducing the time spent in the class on lecturing; and opening up class time for active learning approaches (McLaughlin et al., 2014a).

Years ago, King and colleagues encouraged the College of Education at California State University to move away from remaining a “sage on the stage” to be more of a “guide on the side” in their educational techniques (King, 1993). King et al. argued that information acquired from professors or teachers was encouraged to be developed by students using the information they already knew. Additionally, Gilboy and colleagues argue that active learning strategies, such as case-based learning and other group activities, are among the best ways to promote the development of student information into knowledge (Gilboy et al., 2015).

In recent years, flipped classrooms (FCs) have gained popularity as independent learning innovations. The FC model is a blended learning approach that is increasingly widespread in the education of healthcare students and higher education (McLaughlin et al., 2014a). According to Estes et al. (2014), the FC approach is based on two primary concepts. First, self-directed learning can take place outside the classroom using a computer and the internet to provide students with pre-class materials. Second, group learning activities occur in the classroom (Estes. M. D., Ingram, R., & Liu, 2014).

The FC model has transformed education by changing traditional learning as well as by improving the interaction between students and instructors during class. Typical traditional learning usually involves students listening to educator lectures in class, followed by completing the assigned work after the class. A typical lecture flipping, or ‘inverting’, consists of three phases: pre-class, in-class, and post-class activities. In pre-class learning activities, the teacher directs students to video-recorded lectures, which are available online, or audio lectures as part of their homework, to teach them key concepts of a particular topic. In this phase, students are usually provided with the key points of the lecture content without unnecessary details. During the in-class phase, students are expected to become familiar with the basic information required to progress through in-class activities. The teacher usually acts as a facilitator for students by clarifying lecture concepts through problem solving. The students are mainly involved in interactive activities, such as case discussions, quizzes, small group discussions, pair-and-share learning activities, student presentations, and micro-lectures. The teacher or facilitator is available to answer any questions that the students might have. Post-class learning is usually similar to traditional teaching methods that involve examinations, portfolios, class projects, and other forms of learning assessments (Hew and Lo, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a disruptive force responsible for global changes in the educational system (Taylor et al., 2020). This pandemic has caused most universities to adopt online delivery of lectures instead of face-to-face classes (Taylor et al., 2020). A rapid shift to online learning has facilitated the use of online platforms for distance learning, thus influencing the use of the FC model (Camargo et al., 2020). The FC model is designed to enhance student learning by incorporating active learning into traditional lectures, making it a particularly suitable teaching approach for online and distance education (Anderson et al., 2017, McLaughlin et al., 2014a, Suda et al., 2014). The success of the FC model in medical, nursing, and pharmacy education highlights its potential for effective application in other fields of education, especially in the current era of online and distance learning (Koo et al., 2016, McLaughlin et al., 2013, Rotellar and Cain, 2016). This underscores the importance of evaluating and developing guidance for the introduction and implementation of the FC model in different educational programs. Outside the classroom, students are self-directed learners, whereas active engagement of students in problem solving and critical thinking occurs inside the classroom (Rotellar and Cain, 2016). This systematic review aimed to evaluate the flipped classroom teaching approach in pharmacy education and to provide a summary of the guidance for the introduction and implementation of the flipped classroom model within pharmacy educational programs.

2. Method

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Search strategy

The search encompassed eight electronic databases and one official website. The databases included PUBMED, SCOPUS, the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Cochrane Review, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL), Education Search Complete, Academic Search Ultimate, and the Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE). The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) website was also searched for further relevant information about the use of the flipped classroom approach in pharmacy education. Following the Population, Intervention, Control, and Outcome (PICO) framework (Aslam and Emmanuel, 2010), relevant search terms were identified and combined using Boolean operators, as presented in Appendix 1. The search strategy was tailored to each database and medical search headings (MeSH terms) were also utilized. Hand searching of the reference lists of the included studies was also conducted to identify additional articles for consideration.

The nine data sources were divided among the four authors (NJ, JS, NS, and MA) while ensuring that each data source was searched by at least two authors independently. Each author independently screened the studies by title and abstract in the first instance. Once the two reviewers completed the screening of the same databases, their results were compared. Any discrepancies in the initial screening were discussed among the authors and resolved. Once the initial screening was completed and agreed upon by title and abstract, each author reviewed the full-text articles to determine eligibility for inclusion against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between authors reviewing the studies from the same data sources were discussed and resolved by consensus.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search was limited to English language and peer-reviewed scholarly articles published until April 2021, focusing on pharmacy students at all levels. Non-peer-reviewed articles and conference proceedings were not included. General reviews relevant to the flipped classroom in healthcare/medical education were excluded unless the reviews specifically included pharmacy-related data that could be extracted separately. Studies were also excluded if the teaching approach implemented was inconsistent with the flipped classroom method, which consists of a pre-class phase that requires students to complete independent learning by accessing lecture materials before turning up to the scheduled class time via some sort of technology and an in-class phase that involves face-to-face class time devoted to interactive activities and discussion.

2.3. Data extraction and analysis

Data were independently extracted by four reviewers. The reviewers developed a form to standardize the extracted information, as shown in Table 1. The following data were extracted: country where the study was conducted, study design, number of students/participants, educational level of participants (year or level), description of the flipped classroom implementation (pre-class preparation strategies and in-class active learning strategies), course/program using the flipped classroom, duration of the FC model implementation in the course, and outcomes measured or assessed following the use of the flipped classroom method. In addition, information from studies reporting guidance on how best to introduce and use a flipped classroom approach in pharmacy educational programs was collated. Table 1 presents the findings of the studies.

Table 1.

Details of the included studies.

| # | Author/ Year | Study Design | Country | Participants' Number/ Sample Size | Level of Participants/ Course | Description of Intervention | Duration of Intervention | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anderson/2017 | Quantitative- experimental -RCT | USA | FC538; TL532 | First professional year /pharmaceutical calculations | Flipped Classroom: pre-work for each class meeting (lectures, reading assignments, group/individual activities), student readiness assessments, active learning, 100 min per session. Control: lecture and modeling of problems, 50 min per session. | Six weeks | MERSQI Score = 15 |

| 2 | Koo/2016 | Quasi-experimental | USA | 89 students in both groups | Second-year pharmacy students/ pharmacotherapy course | Flipped Classroom: students viewed short online videos about the foundational concepts and answered self-assessment questions before face-to-face sessions involving patient case discussions. Control: all faculty members delivered traditional lectures enriched with active-learning activities such as patient cases and interactive questions using an audience response system. When delivered by distance faculty members, the lectures and activities were transmitted using synchronous video conferencing technology. | First and last day of the course in 2012 | MERSQI Score = 12.5 |

| 3 | Lockman/2017 | Non-randomized control trial | USA | TC = 156 and FC = 162 | First professional year course in Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD)/Pharmacology and Therapeutics | Flipped Classroom: classroom-based sessions were held live. Pre-class learning activities: pre-recorded lectures, YouTube-style videos, online interactive modules, case-based guided learning questions, reading textbooks, reading guidelines, reading review articles, and reading clinical trials. Post-class learning activities included reviewing pre-class and in-class learning activities. No incentives. Control: lectures were delivered live in a classroom; recordings were posted on the media site. Students had access to the PowerPoint slides for each lecture. They were given one ungraded problem set for the module and were expected to read relevant chapters in the required textbooks to supplement in-class learning. No incentives. Post-class learning activities included reading the textbook and reviewing notes, slides, and the problem set. | Spring 2016 | MERSQI Score = 12.5 |

| 4 | Munson/2015 | Cohort of Single group pre-test and post-test | USA | Control group 2012n = 88; control group 2013n = 118; flipped group 2014n = 118 | First professional (P1) year course in pharmacy curriculum/The Essentials of Pharmacogenomics | Flipped Classroom: pre-class activities: students were directed to review pre-recorded video mini-lectures. In the class session, students completed a voluntary pre-test. The subsequent in-class activity consisted of a brief review of genetic concepts, student participation in answering questions, and an in-class activity. Within 12 h of completion of the class session, students were requested to complete a voluntary post-test. Control: the lecture material was presented as two live lectures during the scheduled class, recorded, and made available for viewing on iTunes University after class. | 15 weeks | MERSQI Score = 13.5 |

| 5 | Gloudeman/2018 | Non-randomized control trial | USA | Control = 104; intervention = 102 | First-year pharmacy students/ pharmaceutical calculations | Flipped Classroom: pre-class: videos posted, slides from modules posted, reading materials posted, and class problems posted. In-class activities: review of materials before class required, announced quiz, introduction, answer questions, active learning activity, and solutions posted at the end of class. Post-class: block exams. Control: lecture slides posted, reading materials posted, and class problems posted. A review of materials before class was advised. In-class activity: live lecture, active learning activity, solutions posted at the end of class. Post-class activity: block exams. | Six weeks | MERSQI Score = 11.5 |

| 6 | Camiel/2016 | Randomized controlled trial | USA | 305 students | Fourth-year (PY4) students/Over the Counter Drugs/Self-Care | Flipped Classroom: pre-class: review pre-recorded materials, reading assignments, and study guides. In-class activity: the instructor summarized the questions posted previously on Facebook, quizzes. Control: live lecture. | One semester | MERSQI Score = 11.5 |

| 7 | Patanwala/2017 | Cross‐sectional study | USA | 100 students | Second-year students/ therapeutics course | In one section of the course (four sessions) all content was provided in the form of lecture videos that students had to watch before class. Class time was spent discussing patient cases. Intervention: for half of the sessions, there was an electronic quiz due before class. | One semester | MERSQI Score = 11.5 |

| 8 | Taglieri/2017 | Non-randomized control trial | USA | Control = 283, intervention TBL group = 305 students | Third professional year/Over-the-Counter Drugs/Self-Care Products (OTC) course | Flipped Classroom: pre-class activity: pre-recorded materials, reading assignments, study guides, and readiness assurance test (RAT). In-class activity: exercises for 75 min and team readiness assurance test (tRAT). Control: live lecture and active learning was incorporated into lectures by cases, audience response clickers, and think–pair–share activities. | One semester | MERSQI Score = 13 |

| 9 | Ferreri/2013 | Descriptive, retrospective | USA | Before course redesign (n = 146); after course redesign, year 1 (n = 152); after course redesign, year 2 (n = 151) | Second year of the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program/self-care course |

Flipped Classroom: required reading for class preparation and small group case-based activities in class; 80 min session 2x/wk Control: 2 hr session once per wk |

Two years | MERSQI Score = 11.5 |

| 10 | Persky/2014 | Retrospective, quantitative (8 years) | USA | LAL and LAL (n = 250) LAL and CBL (n = 143) REC and CBL (n = 435) TBL and CBL(n = 459) |

Second professional year/foundational pharmacokinetics course and a clinical pharmacokinetics course | Flipped Classroom: pre-class activity: e-book, animated module, PowerPoint slides, abridged readings, textbook chapters with reading guides, and primary literature. In-class activity: discussion or case studies in smaller groups. Control: video-conferenced to satellite campuses using lecture-with-active-learning (LAL) strategies. | Eight years | MERSQI score = 10 |

| 11 | Marshall/2014 | Non-randomized, experimental cross-over study with a questionnaire | USA | Class enrolment was 128 for the first year and 141 for the second year | Third-year pharmacy students/gout and osteoarthritis; the course was Pharmaco-therapeutics | Abbreviated Lecture Format: Abbreviated lecture (30 %), case-based questions (70 %). Pre-class: learning objectives, assigned readings, and PowerPoint presentations with multiple mini-cases posted to the platform. In-class: individual readiness assurance test (iRAT) Post-class: examination questions on subsequent examination. Traditional Lecture Format: traditional lecture (70 %), guided discussion of one comprehensive case (30 %); no in-class assessment of individual performance during the case. | One year each arm | MERSQI Score 13.5 |

| 12 | Almanasef/2020 | Non-randomized, two-group questionnaire for students on their opinions | Saudi Arabia | 24 students | Level 8 PharmD students/ Pharmacoepidemiology | Flipped Classroom: pre-class: self-learning materials; video clips, reading materials, and online voice-over PowerPoint lectures. In class: brief recap Q/A, interactive tasks such as group discussions, educational games, and calculations. Traditional Classroom: comprises 22 h of PowerPoint slide-assisted lecturing. | Five classes | MERSQI Score 13.5 |

| 13 | Kangwantas/2017 | Non-randomized, two-group questionnaire for students on their opinions | Thailand | Traditional arm = 21 students, flipped classroom = 29 students | Second-year Doctor of Pharmacy students/Fundamental Nutrition course, the principle of nutrition focusing on carbohydrates in diabetes mellitus | Flipped Classroom Arm: pre-class preparation: a package of pre-assigned self-learning materials relevant to the learning objectives including video clips, reading materials, and group activities. In-class activities: quizzes, real-life case discussions, and problem solving. The Traditional Arm: traditional lecture format and student self-directed learning. The teaching load was shared by three instructors independently. | 15-week semester | MERSQI Score 11.5 |

| 14 | Morrissey/2016 | Non-randomized, three flipped groups, no comparator arm. Questionnaire for students on their opinion | Australia | In module one: 20 students. Module four: six pairs of students thus 12 students, thus the known total is 32 students. The number of students in modules two and three was not mentioned. | First-, third- and fourth-year students. The flipped classroom approach was used for year three and year four students. The units for the third year were clinical pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring. The units for the fourth year were advanced therapeutics (pediatrics, geriatrics, oncology, and palliative care). | Four projects were conducted: first--, third-, and fourth-year students were asked to prepare for the in-class activities at home using the lectures or simulation software. First Year: addressing the issue most identified by students as being lacking. Third Year: simulation and flipping the classroom for two units. Fourth Year: simulation and flipping the classroom for one unit. Flipping the Classroom Strategies: case and problem-based learning, group activities, and peer review. | 12 weeks | MERSQI Score 11 |

| 15 | Cotta/2016 | Non-randomized, two-group comparator study. Questionnaire for students on their perceptions. | United States of America | The flipped classroom cohort was made up of 151 students; the traditionally taught cohort was made up of 165 students. The response rate to the questionnaire was 100 %. | First-year students/Pharmaceutical calculations | Flipped Classroom Arm: pre-class activities: pre-recorded video modules, consisting of PowerPoint presentation, along with the instructor’s voice, and the feature for the instructor to annotate slides and homework problems from the assigned textbook. In-class activities: students to ask questions about the material covered in the modules, and to work on the in-class problems and discussions. Traditional Arm: Live in-class lectures followed by solving assigned problems, with the instructor available to assist students who requested help. | Five weeks | MERSQI Score 14 |

| 16 | Muzyk/2015 | Non-randomized, two-group comparator study. Questionnaire for students on their perceptions of the flipped arm only. | USA | One hundred and four students. > 85 % of students completed the pre- and post-module attitudinal surveys | Third-year Pharm D students/ Psychopharmacotherapy in a pharmacotherapeutics course | Flipped Classroom Arm: pre-class activities: students were asked to view posted materials and to complete assignments pr. Posted material consisted of a PowerPoint presentation, general review articles, a question set for each respective session topic, and patient cases. In-class activities: active learning exercises and discussion. Traditional Arm: This was conducted in 2012, two years before the flipped arm. | A two-week period consisting of five class sessions | MERSQI Score 14.5 |

| 17 | Chan/2020 | A non-randomized, one-group questionnaire study. A survey was distributed as a questionnaire (ten questions total, two open-ended questions). | Malaysia | 320 students approached 256 students, and 80.3 % responded | Second-, third-, or fourth-year students/N/A | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | MERSQI Score 8 |

| 18 | He, Yuan/2019 | A clustered randomized controlled study. | China | 137 students in total. Eighty-one students participated in three FC groups, while fifty-six students participated in two LBL groups. The sample size had a calculated 80 % statistical power. | Junior year (perhaps the year before graduation, but it was not specified)/ pharmaceutical marketing course | Flipped Classroom Arm: pre-class preparation: narrated micro videos and reading materials, including PowerPoint courseware, textbook sections, self-learning materials, and exercise information. The students were divided into groups and required to prepare a presentation before class time. In-class activities: lecture (ten minutes). The students were allocated eight minutes to present, and three to four minutes for a question-and-answer session. This was followed by group-based discussions and group-based learning exercises, which took ninety minutes. Traditional Arm: pre-class preparation: learning materials, including teaching materials, classic cases, quizzes, and exercises. In-class: 110-minute lecture, followed by 10 min of communication between the teacher and students. | Four consecutive weeks | MERSQI Score 15.5 |

| 19 | Suda KJ/ 2014 | Non-randomized, two-group comparator study. Questionnaire for students on their perceptions. | USA | Over the two course offerings, 319 student pharmacists completed the traditional course n = 176 (55.2 %) and the blended learning course n = 143 (44.8 %). (140 students; 97.9 %) responded to the survey. | Third-year pharmacy students/drug information and literature evaluation | Flipped Classroom Arm: online pre-recorded video lectures. All recorded lectures were available for viewing from the beginning of the semester until a specific weekly expiration date. Classroom time: active learning activities using team-based learning, multiple-choice quizzes at the beginning of class as individual readiness assurance tests (iRATs), and team readiness assurance tests (tRATs). Traditional Arm: traditional course (live lectures with active learning recitations). | The whole semester. A total of 30 lectures were presented throughout the semester; four were delivered live during scheduled class time and 26 lectures were pre-recorded and available online only. | MERSQI Score 13.5 |

| 20 | Ghoneim and El-Lakany/2017 | Mixed methods: survey and qualitative in-class-solicitedvoluntary feedback from student comments | Lebanon | The number of responding students is 17–21 out of 102 total class enrolments for the survey and 10 students for the voluntary comments | Students in the last year (9th semester) of the 5-year (total of 10 semesters)/ Pharmacotherapeutics program | Pre-class activities: introductory discussions, preliminary reading, online resources, online free videos reliable web links, and question and answer sessions. In-class activities: group presentations, drug information resources appraisal, oral quizzes, formative/ summative assessments, case studies, mini-lectures, and didactic lectures. | 1 Academic year 2014–2015, 3 h delivered once weekly along with 15 weeks ofthe fall semester | MERSQI = 8 |

| 21 | Khanova/2015 | An inductive qualitative analysis of students' comments from mid-course and end-of-course evaluations of 10 flipped courses | USA | 6010 students' comments | All students across the program/10 courses (Science and Pharmacotherapy) | Half of the courses used video lectures as the primary format for pre-class learning, and the other half utilized various text-based materials (e.g., textbooks, online modules, scholarly articles) for pre-class study. In-class activities included: micro lectures, small group discussions, the use of an audience response system, and instructor-led case analysis. | Data were collected from flipped courses running between 2012 and 2014 | JBI = high |

| 22 | Nazar/2019 | Student perceptions towards the blended learning approach were assessed using a validated survey tool and followed up with focus group discussions | UK | 53 students completed the survey from a total of 63 students. Consenting students (n = 39) were invited to one of four focus groups, in groups of 10–12 aiming to achieve groups of 8–10 students. | Second-year students/ Pharmacy law | Nine hours of flipped classroom sessions. Pre-class activities included online videos and in-class activities that explored the application and nuances of law through simulated cases. | 1:Blended learning approach was introduced in 2015. 2: Survey given in 2017 and focus groups conducted between Jan-March 2017. 3: Data about the performance of students were obtained from the previous two cohorts (2015–2016 and 2014–2015). | MERSQI = 13.5 |

| 23 | McLaughlin/2013 | Mixed methods: survey and qualitative course evaluation | USA | 19 of the 22 students completed the survey | First-year students/ Pharmaceutics | Recorded course lectures were placed on the course website for students to watch before class. Scheduled class periods were dedicated to participating in active learning exercises. | The flipped course was introduced in 2012. A survey was administered at the beginning and end of the flipped course in 2012. Performance data were collected from 2011 to 2012. | MERSQI = 14.5 |

| 24 | Khanova/ 2015 | Pre-course and post-course survey instruments | USA | The class cohort is 171 and 134 students completed the survey | Third-year students/ Pharmacotherapy | Pre-class activities: Introductory video, a series of linked webpages containing comprehensive information about the topic and pop-up definitions, embedded interactive assessments termed “Quick Check” questions, and real-time discussion forums for students. The in-class learning activities incorporated a variety of active-learning strategies, such as audience-response (aka “clicker”) questions, peer discussions, use of videos and review of diagnostic criteria, and interactive exercises. | In spring 2014, the 5-week course was redesigned using the flipped model. At least six of the courses 2 years before the study had incorporated some form of blended or flipped learning for all or part of the course. | MERSEQI = 10.5 |

| 25 | Wilson/2016 | A questionnaire was designed to assess student perceptions of retention and preparedness for advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) rotations, as well as measure long-term retention through a quiz. Short-term retention was evaluated by comparing performance on course exams between the two cohorts. | USA | The email was sent to a total of 189 students (87 from the traditional cohort and 102 from the TBL cohort). Overall, 97 responses (37 responses from the traditional cohort and 60 from the TBL cohort). Incomplete questionnaires were excluded; therefore, 77 responses were used in data analysis (31 responses from the traditional cohort and 46 from the TBL cohort). | Second-year students/ OTC Pharmacotherapy | Pre-class reading and the use of team readiness assurance processes (RAPs), or readiness assurance tests (RATs). In-class activities included discussions and activities. | 1: TBL was introduced in the fall of 2013. 2: Comparing the actual exam scores between the two cohorts in fall 2012 and fall 2013. 3: The questionnaire was distributed in spring 2014 (to the cohort that completed the course in fall 2012) and spring 2015 (to the cohort that completed the course in fall 2013). | MERSQI 13.5 |

| 26 | Hughes/2016 | Pre- and post-exposure surveys to allow for paired analysis of six opinion-based surveys | UK | Of 127 students in the class, 115 (90 %) completed the pre-exposure survey and 88 (76 %) completed the post-exposure survey | First-year students/ foundational drug information course | Pre-class activities: narrated video focusing on specific learning outcomes. In class: sessions were designed to allow students to reinforce and apply the material that was presented in the online videos the previous week and consisted of exercises dedicated to drug information. | Blended learning was introduced in 2013 (the course was a one-credit-hour required course delivered during the first five weeks). A survey was conducted in 2013 at the end of the 5 weeks and secondary data (such as student performance) were collected between 2012 and 2013. | MERSQI = 14 |

| 27 | McLaughlin/2014 | A design experiment | USA | The control group = 153 students, the intervention group = 163 students | First-year professional students/Basic Pharmaceutics II | Flipped Classroom: Viewing online videos, assigned textbook and background reading, and four active learning exercises (75 min). Audience response and open questions, pair and share activities, student presentation and discussion, individual or paired quiz, and micro-lectures (2–3) minutes, as needed. Control Group: 75 min lecture and an occasional 15-minute active learning activity (quiz or pair and share activity). | 13 weeks, 25 classes (each lasting 75 min) | MERSQI 11.5 |

| 28 | Kugler/2019 | A pre- and post-course survey design | USA | 2014: pre-course survey 110, post-course survey 58; 2015: pre-course survey 110, post-course survey 80 | Second-year (P2) studentsin a four-year Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD)program/ Gastrointestinal and Liver Pharmacotherapy | Flipped Classroom: Viewing online videos and responding to a set of self-assessment questions, discussing key points, asking questions, completing individual assessment (ARS), developing case-based examination questions, team case activity, and classroom discussion. Control Group: homework reading from a required textbook, an in-class lecture session with audience response questions, a small group discussion of a case, submission of a team SOAP note or similar assignment, and a final discussion of the case. | One week, two days | MERSQI 11.5 |

| 29 | Goh CF/2019 | Quasi-experimental pre- and post-test control group design | Malaysia | The control group = 114 students, the intervention group = 109 students; n = 105 students completed the flipped classroom perception survey | Second-year pharmacy students/Dosage Form II (sterile preparations) | Flipped Classroom: Viewing online videos (60–85 min), posting questions on the eLearning portal, analogical learning and team discussion during class time, online games, and question asking as a post-class activity. Control Group: conventional lecturing allows students to post their questions on the eLearning portal. | Three classes | MERSQI 13.5 |

| 30 | Zeeman/ 2018 | Cross-sectional study | USA | 402 students | First-year PharmD students/Orientation program | Flipped Classroom: the pre-class phase involved completing an asynchronous online orientation program, and this was followed by attending onsite orientation activities and discussion sessions. | One program | MERSQI 7 |

| 31 | Duffy/2020 | Single-group pre-test and post-test | USA | Five students | Third-year Doctor of Pharmacy Students/ “Oncology Pharmacotherapy didacticelective” | Flipped Classroom: the pre-class phase involved completing assigned reading, prescription verification, preparing for mock patient counseling, and completing a self-reflection questionnaire related to the topic being covered; the in-class phase involved a 20 min PowerPoint presentation covering key concepts and integrating the responses for the self-reflection questionnaire, think–share–pair activity, developing a revised prescription order, small group mock counseling, real-life patient counseling with feedback, and a question and answer session. | One class | MERSQI 7.5 |

| 32 | Mitroka/2020 | Retrospective analysis | USA | The number of students enrolled in the course ranged between 58 and 80 students; the total number of students included in the retrospective analysis was 517 students | First-year pharmaceuticalscience/Principles of Drug Action I | Flipped Classroom: pre-class activities involved listening to voice-over presentation slides, and this was followed by in-class activities that involved individual and team readiness assessment quizzes, and team discussions (team-based learning). Control Group: using the lecture-based approach with the use of interactive polling on lecture content. | One month | MERSQI 10.5 |

| 33 | Wong/2014 | Non-randomized, two groups | USA | Flipped classroom group = 101 students, control group = 105 students; 68 out of 101 students completed the flipped classroom satisfaction survey | First-year pharmacy students/basic sciences, pharmacology, and therapeutics on cardiac arrhythmias | Flipped Classroom: the pre-class activities involved reviewing pre-recorded lectures (90–130 min), learning objectives, lecture notes, and reading materials, and the in-class activities involved short, multiple-choice quizzes, 20-minute question and answer sessions, active-learning exercises that included reading and interpreting electrocardiograms in basic sciences, performing calculations in pharmacology, and discussing and managing cardiac arrhythmia patient cases in therapeutics. The Control Group: traditional teaching method. | Three classes | MERSQI 11.5 |

| 34 | Giuliano/2016 | Quasi-experimental design | USA | Flipped classroom group = 99 students, control group = 94 students; 82 out of 94 students completed the flipped classroom satisfaction survey | First-year pharmacy students/drug literature evaluation course | Flipped Classroom: the pre-class phase involved viewing online lectures, followed by in-class interactive activities. Control Group: traditional teaching method. | Entire course | MERSQI 14.5 |

| 35 | Pierce/2012 | A design experiment | USA | 71 Students | 8 % had 1–2 years of undergraduate education, 11 % had associate degrees 20 % had more than three years of undergraduate education, and58% have bachelor’s degrees/Renal Pharmacotherapy |

Students viewed vodcasts (video podcasts) of lectures before the scheduled class and then discussed interactive cases of patients with end-stage renal disease in class. A process-oriented guided inquiry learning (POGIL) activity was developed and implemented that complemented, summarized, and allowed for the application of the material contained in the previously viewed lectures. | Module occurred in an 8-week pharmacy-integrated therapeutics course that met twice weekly for 2 h. | MERSQI Score = 12 |

FC = Flipped classroom; TC = traditional classroom; MERSQI = Medical Education Research Quality Instrument; JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute.

Qualitative data within the studies reporting students’ and teachers’ perceptions and views about the FC methods were also analyzed using thematic analysis. We followed the six phases proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) (Braun and Clarke, 2006), which consisted of (1) familiarizing oneself with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report.

2.4. Quality assessment

Two tools were used to appraise articles that met the inclusion criteria. These were the Medical Education Research Quality Instrument (MERSQI) (Cook and Reed, 2015), with outcome scores ranging from 2 (low-quality research) to 18 (high-quality research), and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for qualitative research (16), with studies being graded as high, medium, or low. At least two authors completed the quality assessment of each article. Any discrepancies in the quality assessment results between reviewers were resolved through discussion. Further details of the quality assessment tools used are provided in Appendix 2.

3. Results

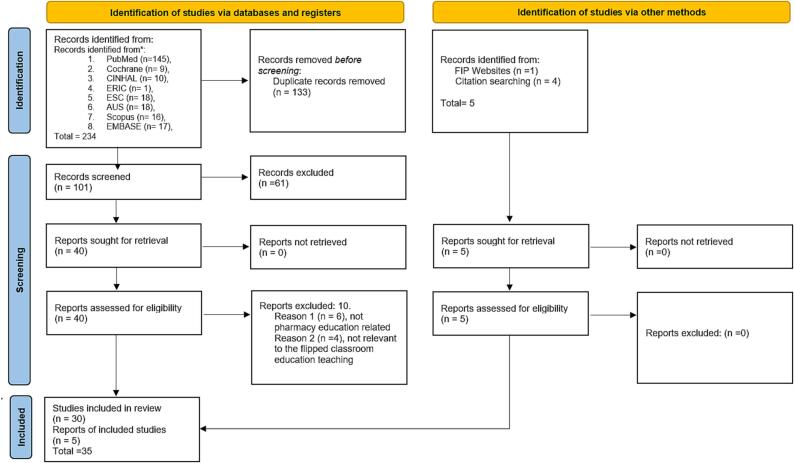

A total of 239 articles from nine data sources were identified. Duplicates were removed. Following the initial screening by abstract and title, 61 articles were deemed irrelevant and were removed.

The remaining 40 articles were screened by at least two reviewers according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following full-text screening, 35 articles were assessed and identified for inclusion in the review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

3.1. Quality assessment

MERSQI was used to assess the quality of 34 of the included studies that combined qualitative and quantitative data. The highest observed score was 15.5/18 (Anderson et al., 2017) and the lowest score was 7/18 (Zeeman et al., 2018), with a mean score of 11.8 for all studies. None of the studies received a score of 18. The JBI was used to appraise the quality of one qualitative study (Khanova et al., 2015b), which scored highly. Several included studies scored low in the MERSQI because all the studies were conducted within one institution, and there was missing information relevant to the predictive correlation with other variables in the study. Furthermore, some of the studies lacked internal structural evidence, such as reliability (internal consistency and test–retest) and factor analysis. No study was excluded because of its quality assessment scores.

3.2. Study characteristics

The included studies were different in study design, sample size, duration of use of the FC model, and outcome measures; however, all of them were conducted at a single university rather than a multi-center. As shown in Table 2, the FC model has been implemented in various undergraduate pharmacy education programs, mostly in the United States. The duration of the FC intervention varied between studies, with the longest implementation observed at a pharmacy institution in the USA where the FC model has been used for eight years (Persky and Dupuis, 2014). The use of the FC model within particular courses ranged from using it for only one class (Ferreri and O’Connor, 2013) to using it throughout the whole module/course throughout the semester (Duffy et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

3.3. Implementation

Several studies have described how the FC model is implemented in their research. The studies utilized FC implementation methods, which included using technology to provide the course content beyond the scheduled class time, allowing the instructor to engage students in learning activities during the in-class sessions. However, variations were found in the nature and type of implemented pre-class and in-class learning activities.

As observed in most studies (n = 29, 40 %) (Camiel et al., 2016, Cotta et al., 2016, Kangwantas et al., 2017, Koo et al., 2016, Lockman et al., 2017, Munson and Pierce, 2015, Suda et al., 2014, Taglieri et al., 2017), pre-recorded lectures were the most commonly used means of delivering the off-load content of the course, which allowed students to complete their independent learning. The format used for the pre-recorded lectures and their duration varied. Previous studies have reported that some pre-recorded lectures lasted only 20 min in length (Khanova et al., 2015b), while others were up to 130 min in length (Wong et al., 2014).

The pre-class learning modalities used in the FC model varied and included the use of multimedia such as lecture recording (using videos, podcasts, PowerPoint slides with voiceover, and simulation videos) and/or reading materials (such as textbooks, guidelines, guided readings, primary literature, and handouts) that were accessed online through module/course sites or social media. A few studies have required students to complete assigned pre-class work and then answer self-assessment questions before engaging in face-to-face sessions (Koo et al., 2016, Taglieri et al., 2017, Wilson et al., 2016). Completing the pre-work assigned by students is key to the success of the flipped classroom teaching model (Patanwala et al., 2017). Adding a motivating element that aimed to encourage students to complete pre-class tasks was observed in one study using graded quizzes (Patanwala et al., 2017). Various interactive learning activities were incorporated during the scheduled class time in all reviewed studies. This includes different strategies that facilitate active learning, such as case-based learning (Munson and Pierce, 2015), problem-based learning (Munson and Pierce, 2015), discussions of key points of the lecture (Munson and Pierce, 2015), students working in groups and applying the information to patient cases (Koo et al., 2016), PowerPoint presentations (Duffy et al., 2020), and quizzes (Gloudeman et al., 2018). One study reported that students’ preparation for in-class interactive sessions decreased with time; however, this was improved when quizzes were assigned (Patanwala et al., 2017). Two studies used exercises and a team readiness assurance test (tRAT) (Taglieri et al., 2017, Wilson et al., 2016) that consisted of five to ten multiple-choice questions based on material reviewed first individually at home (iRAT) and then taking the same RAT as a team (tRAT) at the start of each in-class session (Taglieri et al., 2017).

3.4. Outcome measured

The included studies measured the effectiveness of the FC model by measuring students’ academic performance, long-term knowledge retention, and perceptions. Quantitative studies compared students’ performance before and after implementing the FC model, while qualitative studies explored students’ perceptions, and some combined both.

3.5. Academic performance

The assessment of academic performance varied throughout the study. Evaluating the effectiveness of FC learning outcomes by comparing students’ mean exam scores with either traditional lectures or other teaching approaches was reported in 21 studies (Cotta et al., 2016, Ferreri and O’Connor, 2013, Giuliano and Moser, 2016, Goh and Ong, 2019, He et al., 2019, Kangwantas et al., 2017, Koo et al., 2016, Kugler et al., 2019, Lockman et al., 2017, McLaughlin et al., 2014a, Mitroka et al., 2020, Morrissey and Ball, 2016; Pierce and Fo 012; Suda et al., 2014, Wilson et al., 2016, Wong et al., 2014)). The majority of studies (n = 15, 68 %) (Cotta et al., 2016, Ferreri and O’Connor, 2013, Giuliano and Moser, 2016, Goh and Ong, 2019, He et al., 2019, Kangwantas et al., 2017, Koo et al., 2016, Kugler et al., 2019, Lockman et al., 2017, McLaughlin et al., 2014a, Mitroka et al., 2020, Morrissey and Ball, 2016, Pierce and Fox, 2012, Suda et al., 2014, Wilson et al., 2016, Wong et al., 2014) found that flipped learning enhanced students’ success and exam performance when compared with the traditional model. Six studies (27 %) reported no statistically significant differences in academic performance between students who received traditional lectures and those taught using the FC model (Camiel et al., 2016, Gloudeman et al., 2018, Hughes et al., 2016, Marshall et al., 2014, Munson and Pierce, 2015, Taglieri et al., 2017).

3.6. Long-term knowledge retention

Three studies (Anderson et al., 2017, Taglieri et al., 2017, Wilson et al., 2016) compared long-term knowledge retention between lecture-based and FC learning. Two of them (Anderson et al., 2017, Taglieri et al., 2017) reported that knowledge retention in the long term was lower in FC learning than in lecture-based learning, while one study (Wilson et al., 2016) reported no statistical difference in the knowledge retention of students in the long term after comparing students’ learning through FC and lecture-based learning.

3.7. Students’ perceptions

The students’ perceptions after experiencing the FC model were explored in 26 of the 35 included studies. The students’ perceptions were assessed through surveys (that had close-ended questions and open-ended questions). Students’ written feedback was analyzed using a thematic analysis approach; four main themes were identified from the studies: (1) general course design and FC implementation, (2) pre-class learning, (3) in-class learning, and (4) assessments of critical thinking and skills development.

3.7.1. General course design and FC implementation

Among the positive perceptions of the FC approach and benefits mentioned by students, in one of the studies, students reported that the FC model improved participation during class time (as they were able to independently prepare for the lectures), which gave them more time to process new information (Khanova et al., 2015b). There was some negative feedback regarding the FC approach. In two studies, student perceptions and satisfaction with the learning experience were negatively affected by the FC design (Chan et al., 2020, Khanova et al., 2015a). In a study conducted by Chan and colleagues (Chan et al., 2020), the majority of the students expressed a negative impression of FC learning, indicating that they thought it was an ineffective approach due to the time constraints for pre-class preparation and the low quality of the recorded lectures. Furthermore, one study guided by Khanova (Khanova et al., 2015a) illustrated the challenges of the FC model. The module length and time required to complete pre-class preparation were the most frequently mentioned challenges by the students. One study reported that students prefer a combination of traditional lectures and flipped classrooms (Camiel et al. 2016). In another study, students were dissatisfied with inconsistent grading, unclear assessment questions, and general course policies in the FC model (Ferreri and O’Connor, 2013).

3.7.2. Pre-class learning

In two studies, students expressed satisfaction with pre-class materials that could be accessed at their convenience and allowed them to pause the video lecture and return to it at any time (Khanova et al., 2015b, Nazar et al., 2019). In studies conducted by Khanova et al. (Khanova et al., 2015b, Khanova et al., 2015a), students reported satisfaction with online modules because they could be excellent references for the future and they were able to independently prepare for lectures, which gave them more time to process new information (Khanova et al., 2015b). Some of the students reported that the FC model required a long time for class preparation and increased workload, which made the pre-class homework difficult to complete before the class (Khanova et al., 2015a, Khanova et al., 2015b).

3.7.3. In-class learning

In one of the studies, students reported that the FC model improved their participation during class time, and they found the in-class discussion interesting and enjoyable (Khanova et al., 2015b). In the study by Ghoneim and El-Lakany (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017), students stated that they preferred topics to be presented by the instructor rather than by their peers who had presented the content less clearly and correctly and with less organization. The students also negatively commented on the long presentation time (30–45 min) and the large number of students per group, which led to some students not actively participating in the discussion (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017, Nazar et al., 2019). Students expressed a strong need for in-class review “before jumping right into cases” (Khanova et al., 2015a).

3.7.4. Assessments of critical thinking and skills development

In five studies, students reported a positive perception of improvement in their self-confidence (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017, Goh and Ong, 2019, Kangwantas et al., 2017, Taglieri et al., 2017, Zeeman et al., 2018), while another stated that FC learning had no benefit and that self-confidence was similar in both groups (Taglieri et al., 2017). Ghoneim and El-Lakany students reported that FC learning enhanced the communication and presentation skills of instructors, improved data collection and research, and encouraged and developed continued learning (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017). Students reported that they were more engaged in five studies as their interaction with their instructors and peers increased (He et al., 2019, Khanova et al., 2015b, McLaughlin et al., 2013, Morrissey and Ball, 2016, Muzyk et al., 2015). Improved time management was also reported (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017).

4. Discussion

This systematic review examined the use of the FC approach in pharmacy education across international studies. From 330 articles identified across nine data sources, 35 articles were included in the review. We found that the FC model has been applied to either an entire course or on a more limited scale, such as covering one specific topic. All included studies were relevant to undergraduate pharmacy programs across different institutions, with the majority of the studies conducted in the USA. The studies varied in course, content, and size. In most of the reviewed studies, the role of the instructors was similar and involved preparing pre-class learning material, including video lectures, creating and facilitating in-class activities, and answering students’ questions.

The application of the FC model varies greatly across studies, suggesting that it is not a one-methods-fits-all-all intervention. Therefore, variability was observed across the studies reviewed in flipped classroom implementation. Recorded lectures were the most commonly used means for delivering the pre-class content that enables students to prepare for in-class activities, as this is thought to ally well with the learner preferences of the digital natives of the “Net Generation” (Prensky, 2001). Additionally, watching and listening to a video, particularly on different devices, would enable students to review the material conveniently.

Different interactive learning activities that facilitate active learning were utilized in all reviewed studies during the contact time. These involved case-based learning, pair-and-share activities, problem-based learning, and an audience response system. In-class active learning activities aim to improve students’ engagement, cognitive skills, and attitude and performance. Wong's study found that the flipped classroom is more effective in therapeutics and pharmacology courses than in basic science courses (Wong et al., 2014). The nature of in-class activities, such as patient case discussions, is more enjoyable and effective than the discussion of calculations (Wong et al., 2014).

Students’ preparation before the interactive class time and completing the assigned pre-work is fundamental for the success of the flipped classroom teaching model because it will develop a pattern for the student's strategy of learning and to obtain better outcomes (McLaughlin et al., 2014b). Moreover, experiences that emerged from using the flipped learning approach were claimed to have profound consequences on students’ mastery of the topic, as it enables them to add to the existing knowledge and make inferences based on those knowledge resources (Mitroka et al., 2020). In some studies, viewing a pre-recorded lecture was the only task assigned to students before attending a scheduled interactive class. In addition to the video lectures, assigned pre-class learning also involved completing reading materials and online quizzes. One study added a graded quiz as a motivating element that aimed to encourage students to complete assigned pre-class tasks. Quizzes can be employed as a method to test students’ comprehension by the teacher, measuring students’ understanding of the class material. Bergmann and Sams (Bergmann, J., and Sams, A., 2012) pointed out the use of videos and quizzes as powerful instruments for teachers to share, build content, and refine practice. Pre-class quizzes can also help focus students’ attention on areas with which they are struggling, so the instructor can customize the class activities around those areas. In addition, quizzes serve as an incentive for students to engage with the material on their own as well as with their team (Patanwala et al., 2017) (Khanova et al., 2015a).

The scheduled class time is allocated for interactive exercises and activities, where the instructor plays a facilitative role in guiding students and providing them with formative feedback. Active learning enables students to reinforce their learning of the topic being covered (McLaughlin et al., 2014b). Moreover, the nature of these activities and group work allows students to interact more with their peers and instructors, challenges students to think creatively, and provides expert insight and feedback (McLaughlin et al., 2013).

The findings from the current literature review showed that the FC model enhanced the academic performance of pharmacy students. Some studies have shown that the FC approach does not significantly improve the academic performance of students, suggesting that FC learning enhances the educational experience without significantly impacting summative outcomes (Camiel et al., 2016, Gloudeman et al., 2018, Hughes et al., 2016, Marshall et al., 2014, Munson and Pierce, 2015, Taglieri et al., 2017).

The findings of this review indicate that students generally find the flipped classroom model preferable to traditional lectures (Zeeman et al., 2018, Khanova et al., 2015b, Taglieri et al., 2017, Kangwantas et al., 2017, Goh and Ong, 2019). However, our study also demonstrates that this preference is conditional on the effective implementation of this approach and alignment within the core instructional elements. The issues of increased workload for students associated with self-directed pre-class learning, specifically the length of video lectures, have been noted in several studies (Khanova et al., 2015b, Khanova et al., 2015a, Chan et al., 2020). Our review suggests that the cumulative workload quickly becomes overwhelming and stressful. Additionally, an unmanageable volume of pre-class learning may lead to students coming to class unprepared, preventing them from properly engaging in the classroom. For these reasons, students' preparation decreased over time unless incentives were added to encourage them to prepare before the class (such as graded quizzes) (Patanwala et al., 2017).

Some factors explain why FCs are preferred over TCs. First, FCs provide students with more control and a greater sense of responsibility for their learning, allowing them to obtain personalized learning that suits their needs. Flipping the classroom shifts attention from instructors to learners, generating a student-centered education environment (King, 1993). In FCs, students can access more advanced content before class and move from passive to active learners (King, 1993).

Second, students can learn at their own pace and speed with FCs, which creates more flexibility in terms of place and time (Khanova et al., 2015b, Nazar et al., 2019). If the pre-class homework involved viewing a video lecture, the students could speed up the video content if they understood it and slow down or review the content if they did not.

Third, The FC model can help instructors promote critical and independent thinking in their students (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017) as well as build capacity for lifelong learning, thus preparing pharmacy graduates for their future job environments. Furthermore, understanding the concepts through critical thinking and problem-solving skills rather than spending time in the classroom to explain and clarify the basic concepts enhances peer and student–instructor interactions in FCs (Ghoneim and El-Lakany, 2017, Khanova et al., 2015a, Khanova et al., 2015b, McLaughlin et al., 2013).

Although there is no standardization when applying the FC model, there are a few recommendations collated from the studies included to help introduce and implement the flipped classroom model within pharmacy educational programs (Box 1).

Box 1. Recommendations for implementing FCs in pharmacy programs.

|

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our review had several strengths, such as searching multiple databases, validation by multiple reviewers, and quality assessment of studies conducted by several researchers to reduce bias.

This review could have limitations owing to the heterogeneity of the study designs. In addition to randomized controlled studies and quasi-experimental studies, we included several non-experimental descriptive and qualitative studies to cover the range of available evidence. Moreover, the reported results were mainly from the United States. Therefore, cultural and regional biases may have been present in these studies. Thus, future research should be conducted in other settings, including low- and middle-income countries, to strengthen the evidence base.

The lengths of the implementation of the FC model were wide. Some academic outcomes were examined after a single topic and an entire semester. All the studies involved were relevant to undergraduate pharmacy programs. Therefore, it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to graduate pharmacy education. The variation in terminology in the literature is an issue. Moreover, blended learning and other terms have been used to describe FC approaches, which complicates the search process.

We propose the repeated use of flipped classrooms and related modified strategies on a trial-and-error basis. Furthermore, flipped classroom models should be congruent with the current digitally savvy college students. Moreover, it is important to understand the various influences of today’s student culture, study style, study habits, and use of devices. Further studies are warranted to allow for more detailed conclusions about student performance.

5. Conclusion

This review indicates that pharmacy students generally prefer the flipped classroom (FC) model over traditional lectures. However, the success of this model is conditional on its effective implementation. Key strategies to enhance its effectiveness include incentivizing pre-class preparations with graded quizzes, simplifying pre-class assignments with clear instructions, improving in-class activities for active student participation, encouraging group discussions, investing in digital resources, and targeting courses that best suit the FC approach, such as those with clinical cases. Despite the potential challenges of the FC approach, such as an increased student workload due to pre-class tasks, this learning model cannot be overlooked.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101873.

Contributor Information

Najwa Aljaber, Email: 444203117@student.ksu.edu.sa.

Jamilah Alsaidan, Email: jalsaidan@ksu.edu.sa.

Nada Shebl, Email: n.a.shebl@herts.ac.uk.

Mona Almanasef, Email: malmanasaef@kku.edu.sa.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Almanasef, 2020. Flipping pharmacoepidemiology classes in a Saudi Doctor of Pharmacy program. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. TJPR. https://doi.org/10.4314/tjpr.v19i4.27.

- Anderson, H.G., Frazier, L., Anderson, S.L., Stanton, R., Gillette, C., Broedel-Zaugg, K., Yingling, K., 2017. Comparison of pharmaceutical calculations learning outcomes achieved within a traditional lecture or flipped classroom andragogy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Arum R., Roksa J. University of Chicago Press; 2011. Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam S., Emmanuel P. Formulating a researchable question: A critical step for facilitating good clinical research. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS. 2010;31:47–50. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.69003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, J., & Sams, A., B., J.,.&. Sams, A., 2012. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. International Society for Technology in Education, Washington DC.

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, C.P., Tempski, P.Z., Busnardo, F.F., Martins, M. de A., Gemperli, R., 2020. Online learning and COVID-19: a meta-synthesis analysis. Clin. Sao Paulo Braz. 75, e2286–e2286. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2020/e2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Camiel L.D., Mistry A., Schnee D., Tataronis G., Taglieri C., Zaiken K., Patel D., Nigro S., Jacobson S., Goldman J. Students’ attitudes, academic performance and preferences for content delivery in a very large self-care course redesign. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016;80:67. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.-Y., Lam Y.K., Ng T.F. Student’s perception on the initial experience of the flipped classroom in pharmacy education: Are we ready? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2020;57:62–73. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2018.1541189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D.A., Reed D.A. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2015;90:1067–1076. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta K.I., Shah S., Almgren M.M., Macías-Moriarity L.Z., Mody V. Effectiveness of flipped classroom instructional model in teaching pharmaceutical calculations. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016;8:646–653. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, A.P., Henshaw, A., Trovato, J.A., 2020. Use of active learning and simulation to teach pharmacy students order verification and patient education best practices with oral oncolytic therapies. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 1078155220940395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155220940395. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Estes. M. D., Ingram, R., & Liu, J.C., 2014. A review of flipped classroom research, practice, and technologies. Int. HETL Rev. 4.

- Ferreri S.P., O’Connor S.K. Redesign of a large lecture course into a small-group learning course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2013;77 doi: 10.5688/ajpe77113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim A., El-Lakany A. Student perceptions of a modified flipped classroom model for accreditation in a pharmacotherapeutics course. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017;7:15–20. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2017.71103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboy M.B., Heinerichs S., Pazzaglia G. Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015;47:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano C.A., Moser L.R. Evaluation of a flipped drug literature evaluation course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016;80:66. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloudeman M.W., Shah-Manek B., Wong T.H., Vo C., Ip E.J. Use of condensed videos in a flipped classroom for pharmaceutical calculations: Student perceptions and academic performance. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018;10:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh C.F., Ong E.T. Flipped classroom as an effective approach in enhancing student learning of a pharmacy course with a historically low student pass rate. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019;11:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Lu J., Huang H., He S., Ma N., Sha Z., Sun Y., Li X. The effects of flipped classrooms on undergraduate pharmaceutical marketing learning: A clustered randomized controlled study. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hew K.F., Lo C.K. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2018;18:38. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes P.J., Waldrop B., Chang J. Student perceptions of and performance in a blended foundational drug information course. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016;8:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangwantas K., Pongwecharak J., Rungsardthong K., Jantarathaneewat K., Sappruetthikun P., Maluangnon K. Implementing a flipped classroom approach to a course module in fundamental nutrition for pharmacy students. Pharm. Educ. 2017;17:329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Khanova J., McLaughlin J.E., Rhoney D.H., Roth M.T., Harris S. Student Perceptions of a Flipped Pharmacotherapy Course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015;79:140. doi: 10.5688/ajpe799140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanova J., Roth M.T., Rodgers J.E., McLaughlin J.E. Student experiences across multiple flipped courses in a single curriculum. Med. Educ. 2015;49:1038–1048. doi: 10.1111/medu.12807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. From sage on the stage to guide on the side. Coll. Teach. 1993;41:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, C.L., Demps, E.L., Farris, C., Bowman, J.D., Panahi, L., Boyle, P., 2016. Impact of flipped classroom design on student performance and perceptions in a pharmacotherapy course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kugler A.J., Gogineni H.P., Garavalia L.S. Learning outcomes and student preferences with flipped vs lecture/case teaching model in a block curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019;83:7044. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockman K., Haines S.T., McPherson M.L. Improved learning outcomes after flipping a therapeutics module: results of a controlled trial. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2017;92:1786–1793. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L.L., Nykamp D.L., Momary K.M. Impact of abbreviated lecture with interactive mini-cases vs traditional lecture on student performance in the large classroom. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014;78:1–8. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J.E., Griffin, L.M., Esserman, D.A., Davidson, C.A., Glatt, D.M., Roth, M.T., Gharkholonarehe, N., Mumper, R.J., 2013. Pharmacy student engagement, performance, and perception in a flipped classroom. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.E., Roth, M.T., Glatt, D.M., Gharkholonarehe, N., Davidson, C.A., Griffin, L.M., Esserman, D.A., Mumper, R.J., 2014b. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and in a health professions school. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 89, 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin J.E., Roth M.T., Glatt D.M., Gharkholonarehe N., Davidson C.A., Griffin L.M., Esserman D.A., Mumper R.J. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and in a health professions school. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2014;89:236–243. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitroka J.G., Harrington C., DellaVecchia M.J. A multiyear comparison of flipped-vs. lecture-based teaching on student success in a pharmaceutical science class. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2020;12:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2019.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey H., Ball P. Education case study reports reflection on teaching strategies for pharmacy students. Pharm. Educ. 2016;16:112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Munson A., Pierce R. Flipping content to improve student examination performance in a pharmacogenomics course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015;79:103. doi: 10.5688/ajpe797103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyk A.J., Fuller S., Jiroutek M.R., Grochowski C.O., Butler A.C., Byron May D. Implementation of a flipped classroom model to teach psychopharmacotherapy to third-year doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students. Pharm. Educ. 2015;15:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nazar H., Omer U., Nazar Z., Husband A. A study to investigate the impact of a blended learning teaching approach to teach pharmacy law. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019;27:303–310. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., McGuinness L.A., Stewart L.A., Thomas J., Tricco A.C., Welch V.A., Whiting P., Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patanwala A.E., Erstad B.L., Murphy J.E. Student use of flipped classroom videos in a therapeutics course. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017;9:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persky A.M., Dupuis R.E. An eight-year retrospective study in “flipped” pharmacokinetics courses. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014;78:190. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce R., Fox J. Vodcasts and active-learning exercises in a “flipped classroom” model of a renal pharmacotherapy module. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012;76:196. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. Horiz. 2001;9:1–6. doi: 10.1108/10748120110424816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rotellar, C., Cain, J., 2016. Research, perspectives, and recommendations on implementing the flipped classroom. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Suda K.J., Sterling J.M., Guirguis A.B., Mathur S.K. Student perception and academic performance after implementation of a blended learning approach to a drug information and literature evaluation course. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2014;6:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Taglieri C., Schnee D., Dvorkin Camiel L., Zaiken K., Mistry A., Nigro S., Tataronis G., Patel D., Jacobson S., Goldman J. Comparison of long-term knowledge retention in lecture-based versus flipped team-based learning course delivery. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2017;9:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D., Grant J., Hamdy H., Grant L., Marei H., Venkatramana M. Transformation to learning from a distance. MedEdPublish. 2020;9 doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000076.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J.A., Waghel R.C., Free N.R., Borries A. Impact of team-based learning on perceived and actual retention of over-the-counter pharmacotherapy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2016;8:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong T.H., Ip E.J., Lopes I., Rajagopalan V. Pharmacy students’ performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014;78:185. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman J.M., Wingo B.L., Cox W.C. Design and evaluation of a two-phase learner-centered new student orientation program. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018;10:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.