Abstract

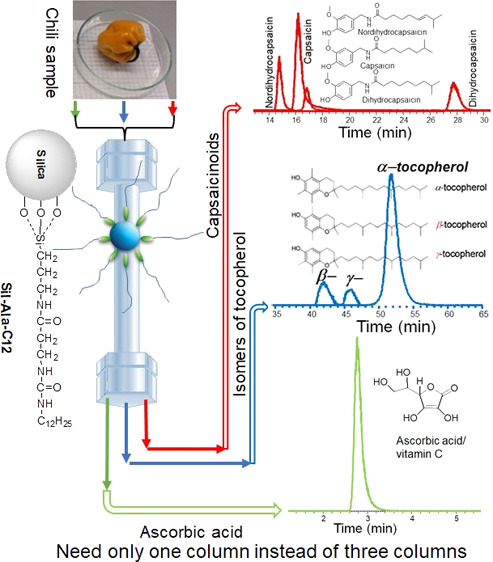

Column purchasing cost is an important issue for an analyst to analyze complex sample matrices. Here, we report the development of an amino acid (β-alanine)-derived stationary phase (Sil-Ala-C12) with strategic and effective interaction sites (amide and urea as embedded polar groups with C12 alkyl chain) able to separate various kinds of analytes. Owing to the balanced hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity of the phase, it showed exceptional separation abilities in both reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) as a hydrophobic phase and hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) as a hydrophilic phase. Remarkably, the baseline separation was achieved for the challenging β- and γ-isomers of tocopherol. Usually, three columns such as pentafluorophenyl or C30, C18, and sulfobetaine HILIC are required for the analysis of vitamin E, capsaicinoids, and vitamin C in chili peppers (Capsicum spp.), respectively. However, only Sil-Ala-C12 was able to separate these analytes. A single column can serve 3–4 purposes, which suggests that Sil-Ala-C12 had the potential to reduce column purchasing costs.

Keywords: colum purchasing cost, polar embedded group, tocopherol, chili pepper, HILIC

Introduction

The reduction of operating costs in any laboratory is very important, and analysts are also concerned. There are many approaches to reducing the operating cost in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) laboratories. For example, increasing the lifetime of a column and saving the solvents and other supplies and reagents. Column lifetime can be increased by using guard columns, high-stability phase with zirconia or silica-organic hybrids, and pH-stable polymeric columns. Solvents and reagents costs can be reduced by applying ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC), where submicron size silica and lower column diameters are used.1 However, one problem remains the same. The column price is usually very high, and one must purchase different columns for different types of analytes. For instance, for hydrophobic, basic, shape-constrained isomers, and highly polar analytes, one needs to buy a hydrophobic phase (e.g., C18), embedded polar group (EPG)-containing alky phase, high-density alkyl phase (polymeric C18) or C30 phase, and polar phase (e.g., bare silica), respectively. If we want to analyze a real sample matrix containing compounds, which can be separated only by various separation mechanisms, then we need to buy three to four columns. To solve this problem of column purchasing cost, the development of a single column/organic phase with properties for the separation of the 3–4 types of analytes mentioned above is desirable.

To consider a real sample containing various types of analytes, chili peppers (Capsicum spp.) are a good example. They contain shape-constrained isomers of tocopherol (vitamin E) and are challenging to separate in LC.2−4 The chili peppers also contain nordihydrocapsaicin, capsaicin, and dihydrocapsaicin (called capsaicinoids), which are responsible for their pungency taste.5 Therefore, their pungency level is determined by knowing the amount of capsaicinoids but a very long time analysis is needed to separate these nonpolar analytes.6 Fresh chili peppers are also a very good source of polar ascorbic acid or vitamin C. However, the amount depends on the degree of ripeness, and it degrades during the drying process.7 For example, Meckelmann et al. used three different columns for the analysis of vitamin E (isomers of tocopherol), capsaicinoids, and vitamin C (ascorbic acid) in chili peppers.4,5

On the other hand, the n-alkyl stationary phases can be divided broadly into two types (monomeric and polymeric), and their properties are dependent on the chemistry of their bonding. Considering the shape selectivity parameter, the monomeric phase shows a much lower performance than the polymeric one.8,9 Moreover, molecular shape selectivity changes on alkyl chain order or chain density,10,11 length of alkyl chain,12−15 architecture and movement of the phase,16−19 and operating temperature.20,21 Therefore, the analyst faces a problem in selecting the appropriate column to investigate complex samples. One screening of all of the columns one by one is troublesome and needs a very long time. Therefore, the analysts developed various characterization tests22 to select and classify appropriate columns for the application in a specific purpose such as Buszewski,23 Engelhardt,24 Euerby,25 Horvath,26 Kirkland,27 Majors,28 Neue,29 Sander,30 and Tanaka.31 Among the above-mentioned tests, the Tanaka31 and Neue29 tests are very common for the characterization and classification of organic phases in reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) separation mode. For the hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) separation mode, Tanaka developed another powerful test of hydrophilic column characterizations.32 In this work, we have developed a stationary phase (Sil-Ala-C12) derived from β-alanine containing two types of EPGs (amide and urea) with a short alkyl chain (C12) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of N-dodecylaminocarbonyl-β-alanine (3) and then grafting onto (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APS)-modified silica.

The phase was designed in such a way that balanced polar and nonpolar parts of the phase took part in multiple interactions with the analytes in different separation modes and mobile phase conditions. The strategy for the use of shorter alkyl chains compared to the commonly used EPG-C18 phase was the creation of an avenue for the analytes to penetrate the interaction sites (double polar groups) easily. Although the hydrophobic interaction was less here, the synergistic effect of two types of polar groups and alkyl chains created a special driving force for the separation of various types of analytes, even those that are challenging with conventional columns. As a result, Sil-Ala-C12 was able to baseline the separation of tocopherol isomers (β- and γ-isomers) and capsaicinoids (nordihydrocapsaicin and capsaicin). A single Sil-Ala-C12 column could be used for the analysis of tocopherols, capsaicinoids, and ascorbic acid in chili peppers, whereas pentafluorophenyl (PFP) or C30, C18, and HILIC columns, respectively, are usually required. Therefore, by developing this type of stationary phase, the column purchasing cost is possible to reduce greatly.

Experimental Section

Materials and Reagents

Dodecyl isocyanate, β-alanine, toluene-p-sulfonic acid (monohydrate), benzyl alcohol, 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APS), diethylphosphorocyanidate (DEPC), and triethylamine (TEA), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Various solvents such as tetrahydrofuran, diethyl ether, methanol, ethanol, and chloroform were purchased from VWR (Darmstadt, Germany). Potassium phosphates (mono- and dibasic), palladium on carbon, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The isomers of tocopherol (α-tocopherol, 97.0%, β-tocopherol, 98.9%, and γ-tocopherol, 97.5%, respectively) were purchased from CalBiochem (Darmstadt, Germany) as standard tocopherol isomers. The Tanaka and Neue test probes (Tables S1 and S2) for RPLC and the Tanaka test probes (Table S3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Capsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, and dihydrocapsaicin were acquired from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) as standard capsaicinoid samples. The tocopherol isomers, capsaicinoids, and ascorbic acid standards were used to monitor the behavior of the new stationary phases before the analysis of the real samples and to achieve a high level of confidence in the identification of these compounds in real samples.

The synthesized β-alanine-derived organic phase (Sil-Ala-C12) was characterized and then packed into a narrow bore of a 150 mm × 2.1 mm i.d. stainless steel column. The silica particles with a diameter of 3 μm, pore size of 10 nm, and 331 m2/g of surface area were obtained from Maisch GmbH, Germany. Many reference commercial columns were purchased for comparing the chromatographic results with our developed column in RPLC, and HILIC mode separations such as alkyl C18 or Reprospher 100 C18-NE, polar amide bonded C18 or Ascentis RP-Amide, and zwitterionic or were obtained from Dr. Maisch, and Merck, Germany. On the other hand, alkyl C30 or Develosil PRAQEOUS-AR, amine or Luna-NH2, and diol or Luna-Diol were purchased from Phenomenex, USA). To compare the chromatographic results and interaction mechanisms, it is also important to compare the physical properties of the columns, and therefore the properties are presented in Table 1. The detailed experimental section is given in the Supporting Information.

Table 1. Parameters for the Physical Properties of the Developed Sil-Ala-C12 Column and the Studied Reference Phasesa.

| surface area (μmol/m2) | pore size (nm) | end-capping | carbon loading (%) | particle size (μm) | bonded phase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reprospher 100 C18-NE | 350 | 10 | no | 15.0 | 3 | monomeric C18 |

| adevelosil PRAQEOUS-AR (C30) | 300 | 14 | yes | 18.0 | 3 | monomeric C30 |

| ascentis RP-amide | 450 | 10 | yes | 19.5 | 3 | amide group embedded C18 |

| Luna-Diol | 200 | 20 | 5.70 | 3 | cross-linked diol | |

| ZIC-HILIC | 10 | 3.5 | sulfobetaine | |||

| Luna-NH2 | 450 | 10 | 9.50 | 3 | free NH2 | |

| Sil-Ala-C12 | 331 | 10 | no | 16.60 | 3 | amide and urea groups embedded C12 |

Column dimensions: 150 × 2.1 mm, a, 150 × 2.0 mm.

Sample and Sample Preparation

Sample

Habanero, rawit, and padrone chili peppers were purchased in a local supermarket in Essen (Germany).

Extraction and Separation of Tocopherols

Fresh chili peppers were ground in a blender, and about 2 g of sample was taken in a 20-mL centrifuge tube. The isomers of tocopherol were extracted with 10 mL of isopropanol and shaken for 4 h. The samples were heated and agitated in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min. To dilute the crude extract, acetonitrile–water and methanol–water were used as these were also used as mobile phases. The diluted crude extracts were filtered through a syringe filter of 0.2 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF). In this study, we excluded δ-tocopherol and tocotrienols for all the samples.

Extraction and Separation of Capsaicinoids

Two grams of fresh ground chili pepper was placed in a 20-mL centrifuge tube, and 15 mL of acetonitrile and methanol (50:50, v/v) were taken. The sample was kept in the dark for 16 h at 4 °C. Then the sample was heated to 80 °C in an oven for 4 h and ultrasonicated at intervals of 30 min. To inject into the HPLC system, the concentration of the crude extract was reduced by diluting with acetonitrile/0.5% acetic acid (50:50, v/v) followed by filtration with a PVDF syringe filter of 0.2 μm. Minor capsaicinoids were not identified in this study.

Extraction and Separation of Ascorbic Acid

In a centrifuge tube, 2 g of chili sample was taken in 10 mL of acetonitrile-ammonium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 6.8) (70:30, v/v without any stabilizer) mixture. The mixer was shaken at room temperature for 2 h. After centrifugation, the crude extract was filtered with the PVDF syringe filter of 0.2 μm.

Results and Discussion

Various kinds of polar groups such as ether, amide, urea, carbamate, sulfonyl, and thiocarbamate have been incorporated with the C18 alkyl chain.33 Their target was to separate polar and basic analytes with a good peak shape. Here, we chose two important polar groups (amide and urea) and shorter/less hydrophobic alkyl chain (C12) not only for the separation of polar and basic analytes but also for shape-constrained and nonpolar isomers in RPLC and hydrophilic analytes in HILIC to reduce the column purchasing cost (Figure 1). The combined polar groups (urea and amide)synergistically provided the sources of hydrogen bonding sources,34−38 carbonyl−π interactions, wettability, and hydrophilicity.17−19 The characterization of the β-alanine-derivative modified silica (Sil-Ala-C12) was carried out with various methods such as elemental analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and 13C cross-polarization magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (13C CP/MAS NMR) spectroscopy (Figure 2). Finally, the chromatographic characterization was performed after packing the material into a stainless steel column of 150 mm × 2.1 mm i.d.

Figure 2.

Solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum of Sil-Ala-C12 at 30 °C.

The elemental analysis results8 were used to calculate the surface coverages of the silica particles modified with 3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APS) grafted silica (Sil-APS) and Sil-Ala-C12 to 4.34 and 2.43 μmol/m2, respectively (Table S4). To observe the surface of the silica particles after immobilization of compound 3, the SEM was measured, and the image showed no agglomeration on silica indicating proper removal of nongrafted molecules (Figure S1). The TGA was measured for further confirmation of the organic content on the silica surface as determined by the elemental analyses (Table S4 and Figure S2). Furthermore, the ATR-FTIR analyses confirmed the immobilization of compound 3 on the silica surface. For example, the C–H bond stretching (long alkyl chains) of Sil-Ala-C12 was observed at 2925 and 2851 cm–1 (Figure S3). The urea- and amide-bonded phases also showed intense bands at 1634 and 1559 cm–1. A broad band at 3320 cm–1 indicates N–H stretching (Figure S3).

The solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR39 measurement (Figure 2) was carried out at 30 °C for investigating the alkyl chain conformations and mobility of the grafted compound 3 onto silica. The conformation of alkyl chains (CH2)n can be identified by the chemical shift of methylene groups in 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy under the state of dipolar coupling of protons and magic angle spinning. Generally, the 13C signals of alkyl chains are observed at two resonances, at around 32.6 and 30.0 ppm, attributed to trans conformation or crystalline state, and the gauche conformation or mobile state, respectively.40 The solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy of Sil-Ala-C12 shows almost gauche conformation with a low trans conformation of the alkyl chain.41,42 Usually, at higher temperatures (e.g., 50 °C), the alkyl chains change from trans to gauche conformation.17 It has been proved with solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR that the alkyl chains in polymeric C18 and monomeric C18 are almost all trans and all gauche conformations, respectively.43 It also has been investigated with the solid-state NMR spectra with extended alkyl chains (C18 to C34) that the trans conformation of alkyl chains enhances for longer and denser alkyl chains, and as a result, the molecular shape selectivity increases.44,45 Although the alkyl chains were shorter in Sil-Ala-C12, higher trans conformation was observed compared to monomeric C18 which might be due to the weak intermolecular interactions among the polar groups leading to little ordering of alkyl chains.43

Before analysis of a real complex sample or a specific type of analyte, it is helpful to apply the column selection system.46 Therefore, the Sil-Ala-C12 column was characterized for the RPLC mode separation with the Tanaka and Neue test protocols to compare the results to the reference commercial columns. Again, Tanaka tests for the HILIC separation mode were applied for the new phase to evaluate and compare the chromatographic results with the commercial HILIC columns, which were originally developed for the HILIC separation mode. The reason for the evaluation with both RPLC and HILIC mode separation for the developed columns was to find out the chromatographic properties of the phase to apply for the analysis of complex real samples with a single column. The Tanaka test parameters for the RPLC separation mode were measured and compared with the commercial columns, as given in Table S5. The test probes for the Tanaka test were selected to analyze the retention and selectivity properties of various columns used in RPLC. The presentation of the Tanaka test properties for different columns with spider/radar plots is easily understandable.47 Hence, to construct the spider plot, the Tanaka test data of various columns given in Table S5 were used (Figure 3). The spider/radar plot was created by normalizing the data for a uniform comparison of properties among the studied columns, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Normalized radar plot of the Tanaka test for Sil-Ala-C12 and the columns used as references.

To simplify the radar plot, negative values were considered zero. The relative differences and similarities as well as the strongest properties of a column for the individual parameter can be found in the radar plot (Figure 3). For example, the amount of alkyl chains was the least in the Sil-Ala-C12 column, although the CH2 selectivity or hydrophobicity was almost the same among the columns. Similarly, the least hydrophobicity was observed compared to the reference columns, which is logical due to the least length of the alkyl chains. However, surprisingly the highest shape selectivity was found with the Sil-Ala-C12 column compared to the reference C18, C30, and EPG (amide) containing C18 columns (Figure 3), although the chain length was the least (Figure S4, Table S5). Moreover, Liu et al. selected eight various columns of EPG-C18 to compare the shape selectivities among them and found maximum shape selectivity of 2.3, while Sil-Ala-C12 reached 2.49 (Table S5) with the same chromatographic conditions,48 indicating the synergistic effect of amide and urea groups of the developed phase. It was an interesting finding as the shape selectivity increased with increasing alkyl chain length,12−15 chain density,12−15 degrees of chain ordering,10,11 and lower temperature20,21 and none of them was applicable for the Sil-Ala-C12 phase. High shape selectivity is an important characteristic of an RPLC column. Because there are huge numbers of analytes with similar structure and polarity, differing in their molecular shapes such as PAHs and natural products.49 Planar triphenylene and nonplanar o-terphenyl were applied as probes for the determination of shape selectivity in the Tanaka test protocol.

The determination of silanol groups on the silica surface of columns indicates their H-bonding capacity (hydrogen bonding capacity) as well as ion exchange capacity at lower and higher pH values (Table S1). In the Tanaka test method, H-bonding capacity (degree of end-capping) was determined by the selectivity between phenol and caffeine. The Sil-Ala-C12 and RP-Amide showed lesser H-bonding capacity compared to the other columns due to the existence of EPGs (Figure 3). Again, due to the polar groups and end-capping, the EPG-C18 exhibited the least H-bonding capacity. The reference C18 and C30 columns showed the highest H-bonding capacities although the C30 column was end-capped, which may be due to incomplete end-capping.31 The selectivities between benzylamine and phenol at pH 7.6 indicated the total ion exchange capacity. The highest value was obtained for the C18 column as expected as it was not end-capped. As the existence of two polar groups or their “shielding” effect, the Sil-Ala-C12 revealed an exceptionally less total ion-exchange capacity, although it was nonend-capped. The acidic ion exchange capacity of Sil-Ala-C12 was very low (negative value), which may be due to the rejection of benzylamine by the phase (Table S5).50

From the above findings on the good properties of Sil-Ala-C12, including shape selectivity (Figure 3), we selected the isomers of vitamin E (α-, β-, γ-isomers tocopherol) as bioactive and shape-constrained isomers. Among the isomers of tocopherol, the separation of the β-, and γ-isomers is very challenging due to their similar hydrophobicity and chemical structure. It is not possible to separate these two isomers with baseline in conventional HPLC on C18 column.51 Strohschein et al. first separated (not baseline) these isomers with a C30 column.52 Mallik et al. separated (baseline) with an alternating copolymer-modified silica column.49 Again, Meckelmann et al. reported baseline separation of β- and γ-isomers using the PFP phase.5 However, the use of a PFP phase with 1.7 μm core–shell silica particles or a UHPLC system was needed. The reduced particle size-based phase (3 μm) showed better separation of β- and γ-isomers of tocopherol than the larger particle size (5 μm) phase.53 Surprisingly, baseline separation of them was achievable on the Sil-Ala-C12 phase (Figures 4 and S5).

Figure 4.

Typical extracted ion chromatograms of β-, γ-, and α-tocopherol isomers in the extracted matrix of fresh chilli pepper (habanero) on Sil-Ala-C12. Mobile phase: methanol–water (0.1% formic acid) (82:18, v/v). Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min, Column temperature: 40 °C. Injection volume: 5 μL. Mass range: m/z = 416.3612–416.3696 for β- and γ-tocopherol and 430.3768–430.3854 for α-tocopherol. The other peaks are those of matrix compounds.

To separate isomers of tocopherol in the extracts of fresh chili peppers, three kinds (habanero, rawit, and padrone) were analyzed, and only habanero showed a clear peak of α-tocopherol on nonsensitive UV detection. The amounts of tocopherols in fresh chilli peppers are very low and depend on the type.5 Therefore, we used LC-ESI-orbitrap-MS (details in the Supporting Information) for the detection of β- and γ- isomers of tocopherol. Figure 4 shows the ion chromatograms of the isomers of tocopherol in the extract of fresh chili pepper (habanero) with LC-ESI-orbitrap-MS.

Again, capsaicin is an active compound in chili peppers not only used for its pungency, taste, and aroma but also for the treatment of various diseases.54 Chili pepper also contains dihydrocapsaicin and nordihydrocapsaicin, which together with capsaicin are the three major capsaicinoids. Capsaicinoids have similar chemical structures and possess difficulty (especially capsaicin and nordihydrocapsaicin) in separation by HPLC. The baseline separation of capsaicin and nordihydrocapsaicin by the common RPLC in isocratic elution and UV detection is challenging due to the similar structure (Figure 5). Capsaicin contains one more CH2 group than norhydrocapsaicin, leading to an increase in retention time; however, the introduction of unsaturation in the side chain decreases retention time. Usually, the C18 column is used for the analysis of capsaicinoids.4 Jin et al. added silver nitrate in the mobile phase for better separation of capsaicin and nordihydrocapsaicin.55 Surprisingly, Sil-Ala-C12 shows very good separations of capsaicinoids even in real sample matrixes regardless of using silver nitrate (Figure 5). Therefore, it was possible to analyze tocopherols and capsaicinoids in chili pepper on Sil-Ala-C12 column.

Figure 5.

Typical extracted ion chromatograms of 1: nordihydrocapsaicin, 2: capsaicin, and 3: dihydrocapsaicin in the extracted matrix of fresh chili pepper (habanero) on Sil-Ala-C12. Mobile phase: Acetonitrile: 0.5% acetic acid (30:70, v/v). Flow rate: 0.4 mL/min. Column temperature: 50 °C. Injection volume: 5 μL. Mass range: m/z = 294.2049–294.2079, 306.2049–306.2079, and 308.2205–308.2235 for nordihydrocapsaicin, capsaicin, and dihydrocapsaicin, respectively. The other peak is that of a matrix compound.

As mentioned earlier, the phase Sil-Ala-C12 was also characterized by the Neue test (Table S6). The Neue test parameters and the radar plot (Figure 6) were calculated and constructed by using the equations in Tables S2 and S6, respectively. To construct the radar plot with comparative values fairly, for the negative values, reciprocal values were taken, omitting negative signs. Both the Neue test and the Tanaka test are used for the characterization of RP columns. However, direct comparison of the parameters for different columns is not possible due to different probes and chromatographic conditions although the Sil-Ala-C12 column showed similar hydrophobic parameters (Figure 6).29

Figure 6.

Normalized radar plot of the Neue test for Sil-Ala-C12 and the commercial columns used as references.

The Sil-Ala-C12 phase also showed the least amount of silanophilic interactions in the Neue test results (Figure 6). Another important parameter of the Neue test is the extended or extra polar selectivity, and the highest value was found for the Sil-Ala-C12 column (Figure 6). The double polar groups (urea and amide) probably synergistically worked to increase the polar selectivity. The phenolic selectivity was also different for the EPG-containing columns than that of the classical bonded columns (Figure 6). EPGs were inserted into the alkyl bonded columns due to the problems (peak tailing and high retention) of analyzing basic elutes on classical bonded columns.33,56,57Figure 7 shows a very high retention time and peak tailing for propranolol and amitriptyline (basic analytes) on C30 and C18 phases. However, the Sil-Ala-C12 phase separated basic, nonpolar, and polar molecules as a test sample very nicely with good peak shapes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Separation of basic, nonpolar, and polar molecules as a test sample on Sil-Ala-C12, RP-Amide, C30, and C18 columns. Mobile phase: methanol:K2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) (70:30, v/v, for Sil-Ala-C12, 55:45, v/v). Flow rate: 0.2 mL/min, column temperature: 30 °C. UV detection: 254 nm.

Sil-Ala-C12 contains short alkyl chains and double polar groups, so it was assumed to work in the HILIC separation mode. Therefore, the Tanaka test probes for HILIC separation mode (Table S3) were applied for the evaluation of the developed column.32 The Tanaka test for HILIC used various types of probes (Figure S6) to characterize the selected columns for a targeted kind of analytes (Table S3) in HILIC. The Tanaka test parameters for the Sil-Ala-C12 column were judged with the commercial and common HILIC phases like diol (Luna-Diol)-, zwitterionic (ZIC-HILIC)-, and amine (Luna-NH2)-phase (Table 2), which were designed only for HILIC. Surprisingly, the highest hydroxyl group, configurational, shape, and anion exchange selectivity were observed on the Sil-Ala-C12 phase compared to commercial HILIC columns (Table 2, Figure S7). The selectivity between theobromine and theophylline (α(Tb/Tp)) indicates the pH on the stationary phase. The pH, 1.00–1.15, less than 1.00 and 1.15 to above indicates neutral, basic, and acidic surface, respectively. Therefore, the surface of Sil-Ala-C12 was basic (Table 2).

Table 2. Parameters for Tanaka Test on Sil-Ala-C12(SIL) and Commercial HILIC Columnsa.

| property tested | SIL | Luna-Diol | ZIC-HILIC | Luna-NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydrophilicity of the phase (k (U)) | 0.41 | 0.65 | 3.12 | 2.76 |

| hydrophobicity/methylene selectivity (α(CH2)) | 1.03 | 1.17 | 1.69 | 1.29 |

| hydroxyl group selectivity (α(OH)) | 3.58 | 1.35 | 2.02 | 1.79 |

| configurational selectivity (α(V/A)) | 1.54 | 1.30 | 1.48 | 1.52 |

| regio selectivity (α(2′-dG/3′-dG)) | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.11 | 1.06 |

| shape selectivity (α(NPαGlu/NPβGlu)) | 1.46 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.10 |

| anion exchange selectivity (AX) | 9.99 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 6.89 |

| cation exchange selectivity (CX) | 0.49 | 2.43 | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| pH on the surface of the stationary phase (α(Tb/Tp)) | 0.11 (basic) | 1.04 (neutral) | 1.16 (neutral) | 0.68 (basic) |

Chromatographic condition: mobile phase: Acetonitrile-ammonium acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 4.7) (90:10, v/v). Flow rate: 0.2 mL/min. Column temperature: 30 °C. UV detection: 254 nm. Injection volume: 5 μL.

The highest shape selectivity on Sil-Ala-C12 was also observed in RPLC. 4-Nitrophenyl α-d-glucopyranoside (NPαGlu) and 4-nitrophenyl β-d-glucopyranoside (NPβGlu) were used as shape-selective parameter in HILIC-like triphenylene and o-terphenyl in RPLC.32 On the other hand, amide group-containing C18 (Ascentis RP-Amide) did not show any retention for the hydrophilic analytes in HILIC (e.g., nucleosides and nucleobases) (Figure S8). Theoretical plates and asymmetry factors were also in an acceptable range for the Sil-Ala-C12 phase (Table S8). The above findings encouraged us to apply the Sil-Ala-C12 phase for real sample analysis in the HILIC mode. We again chose chili peppers because they require a HILIC phase for analysis of ascorbic acid or vitamin C. It is like “killing three birds with one stone”. HILIC is a good method to separate the ascorbic acid from the complex food matrices due to its high polarity.58 Extraction of vitamin C from fresh chili pepper is problematic as it degrades quickly, and some of them may contain Vitamin C below the detection level.4 However, using the LC-ESI-orbitrap-MS system, it was easy to detect ascorbic acid in fresh chili pepper (habanero). Figure 8 shows the extracted ion chromatogram of ascorbic acid in a fresh chili pepper extract on Sil-Ala-C12.

Figure 8.

Extracted ion chromatogram of ascorbic acid in chili pepper (habanero) extract on Sil-Ala-C12. Mobile phase: ACN:ammonium acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 6.8) (80:20, v/v). Flow rate: 0.4 mL/min. Column temperature: 35 °C. Injection volume: 5 μL. Mass range: m/z = 175.0230–175.0266.

The Sil-Ala-C12 with only C12 showed unique and excellent selectivity toward o-terphenyl and triphenylene, tocopherols (especially baseline separation of β- and γ-isomers), and neutral, polar, and basic analytes in RPLC compared to conventional C18, C30, and EPG-C18 phases. In general, the shape selectivity on the C18 column improves with higher carbon grafting onto silica10,11 and alkyl chain length.12−15 This is not due to direct interaction with the guest molecules but rather an increase of carbon loading or surface coverage and a slight increase in chain length in alkyl chain ordering. However, Sil-Ala-C12 showed better selectivity, regardless of the least chain length and lower carbon loading than C30 (%C 18.0) and Ascentis RP-Amide (%C 19.5%) (Table 1). The surface coverage of Sil-Ala-C12 was not so high (2.43 μmol/m2). Therefore, to explain the surprising baseline separation of the β-and γ-isomers of tocopherol, we propose the direct interaction with the carbonyl groups of Ala-C12 and π-electrons from the benzene ring of tocopherol, as illustrated schematically (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration for the recognition of β- and γ-isomers of tocopherol on Sil-Ala-C12. Carbonyl-π interactions are supposed to be the driving forces for this challenging separation. Intermolecular interactions may work to facilitate this interaction by partially ordering the alkyl chains.

Alkyl chains in Sil-Ala-C12 have slight trans conformation (Figure 2) due to the possibility of intermolecular interactions among the polar groups as illustrated in Figure 9. It was reported that the planar and liner analytes have more chance to have multiple carbonyl−π interactions than that of the nonplanar and nonlinear analytes.49 This carbonyl−π interaction is very important for the separation of shape-constrained isomers as it is stronger than π–π and CH4–π interactions.59 Stronger carbonyl−π interaction is possible for the γ-isomer compared to the β-isomer due to more penetration into the interaction site (Figure 9). Again, the Sil-Ala-C12 phase showed very nice separation of the Neue test probes with good peak shape supposed to be for the synergistic effect of both amide and urea groups (Figure 7). The very high separation ability of the Sil-Ala-C12 column was also observed in the HILIC separation mode, and we need to explain it.

The separation mechanism in HILIC is very complicated.60−62 The partitioning mechanism was assumed by Alpert63 who coined the HILIC separation mode. In this mechanism, it is postulated that partition of the analytes occurred between the stagnant water-rich and moving organic-rich layers due to the formation of a stagnant water layer on the stationary phase surface. There are also many reports that many other interactions like adsorption, ion exchange, dipole–dipole interaction, π–π, hydrogen bonding, and n−π supposed to be the driving forces for the separation in HILIC mode retention depending on the properties of stationary phase and analytes.60,64−66 Multiple interactions including partitioning were supposed to be the driving forces for the separation on the Sil-Ala-C12 column in HILIC mode. Moreover, since all of the amine groups were not reacted, free amine groups on the silica surface acted as interaction sites. Therefore, Sil-Ala-C12 exhibited a very high hydroxyl group, configurational, shape, and xanthene selectivities compared to the conventional HILIC columns (Table 2). However, it was certain that these higher selectivities were not from the unreacted free amine groups in the Sil-Ala-C12 phase as these were much higher than the selectivities on the Luna-NH2 column (Table 2).

Conclusions

Herein, we have described the development of a C12 organic phase with an aβ-alanine derivative containing amide and urea groups and its successful applications in RPLC and HILIC separation modes. The organic phase was evaluated/characterized with the Tanaka and Neue tests in RPLC and Tanaka protocol for HILIC and compared with related commonly used commercial columns. Remarkable results were observed on Sil-Ala-C12 compared to the commercial phases, and surprising performance for the separation of versatile analytes was shown. Furthermore, the baseline separation of challenging β- and γ-isomers of tocopherol was achieved on it. Therefore, we applied it for the separation of vitamin E, capsaicinoids, and vitamin C in a complex matrix sample of chili peppers. Generally, three different commercial columns are needed to analyze these three types of analytes from chili peppers, whereas a single Sil-Ala-C12 column does the same job.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Abul K. Mallik highly acknowledges Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for their fellowship and partial research grant for this research work. Thanks to Prof. Matthias Epple, University of Duisburg-Essen, for giving permission to characterize the phase with the ATR-FTIR and SEM. We also acknowledge Dr. Michael Fechtelkord for measuring the solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany (Institute for Geology, Mineralogy and Geophysics).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.3c11932.

More details are in the experimental, materials and method sections; additional physical properties of the stationary phase and other comparative results (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Major E. R. Current Trends in HPLC Column Usage. LC GC Eur. 2012, 25 (1), 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Buszewski B.; Krupczynska K.; Bazylak G. Effect of Stationary Phase Structure on Retention and Selectivity Tuning in the High-Throughput Separation of Tocopherol Isomers by HPLC. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen 2012, 7 (4), 383–391. 10.2174/1386207043328788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentel C.; Strohschein S.; Albert K.; Bayer E. Silver-Plated Vitamins: A Method of Detecting Tocopherols and Carotenoids in LC/ESI-MS Coupling. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70 (20), 4394–4400. 10.1021/ac971329e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckelmann S. W.; Riegel D. W.; Van Zonneveld M. J.; Ríos L.; Peña K.; Ugas R.; Quinonez L.; Mueller-Seitz E.; Petz M. Compositional Characterization of Native Peruvian Chili Peppers (Capsicum Spp.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61 (10), 2530–2537. 10.1021/jf304986q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckelmann S. W.; Riegel D. W.; van Zonneveld M.; Ríos L.; Peña K.; Mueller-Seitz E.; Petz M. Capsaicinoids, Flavonoids, Tocopherols, Antioxidant Capacity and Color Attributes in 23 Native Peruvian Chili Peppers (Capsicum Spp.) Grown in Three Different Locations. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 240 (2), 273–283. 10.1007/s00217-014-2325-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozukue N.; Han J. S.; Kozukue E.; Lee S. J.; Kim J. A.; Lee K. R.; Levin C. E.; Friedman M. Analysis of Eight Capsaicinoids in Peppers and Pepper-Containing Foods by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Liquid Chromatography - Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53 (23), 9172. 10.1021/jf050469j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh M. N.; Wolf W.; Tevini D.; Jung G. Influence of Processing Parameters on the Drying of Spice Paprika. J. Food Eng. 2001, 49 (1), 9172–9181. 10.1016/S0260-8774(00)00185-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L. C.; Pursch M.; Wise S. A. Shape Selectivity for Constrained Solutes in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71 (21), 4821–4830. 10.1021/ac9908187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno K.; Nagoshi T.; Tanaka N.; Fetzer J. C.; Biggs W. R. Eluation Behaviour of Planar and Non-Planar Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Various Chemically Bonded Stationary Phases in Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1987, 392, 75–82. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)94255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey J. G.; Dill K. A. The Molecular Mechanism of Retention in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89 (2), 331–346. 10.1021/cr00092a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Rahman M. M.; Czaun M.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Facile Synthesis of High-Density Poly(Octadecyl Acrylate)-Grafted Silica for Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography by Surface-Initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1187 (1–2), 119–127. 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N.; Sakagami K.; Araki M. Effect of Alkyl Chain Length of the Stationary Phase on Retention and Selectivity in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography: Participation of Solvent Molecules in the Stationary Phase. J. Chromatogr. A 1980, 199, 327–337. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)91384-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L. C.; Wise S. A. Effect of Phase Length on Column Selectivity for the Separation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Reversed Phase LC. Anal. Chem. 1987, 59 (5), 2309–2313. 10.1021/ac00145a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. M.; Sander L. C.; Wise S. A. Temperature Dependence of Carotenoids on C18, C30, and C34 Bonded Stationary Phases. J. Chromatogr. A 1997, 757 (1–2), 29–39. 10.1016/S0021-9673(96)00664-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L. C.; Sharpless K. E.; Craft N. E.; Wise S. A. Development of Engineered Stationary Phases for the Separation of Carotenoid Isomers. Anal. Chem. 1994, 66 (10), 1667–1674. 10.1021/ac00082a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnle M.; Friebolin V.; Albert K.; Rimmer C. A.; Lippa K. A.; Sander L. C. Architecture and Dynamics of C18 Bonded Interphases with Small Molecule Spacers. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81 (24), 10136–10142. 10.1021/ac901911w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Qiu H.; Sawada T.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Molecular Shape Recognition through Self-Assembled Molecular Ordering: Evaluation with Determining Architecture and Dynamics. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84 (15), 6577–6585. 10.1021/ac300791x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Qiu H.; Sawada T.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Molecular-Shape Selectivity by Molecular Gel-Forming Compounds: Bioactive and Shape-Constrained Isomers through the Integration and Orientation of Weak Interaction Sites. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (37), 10341–10343. 10.1039/c1cc13397g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursch M.; Vanderhart D. L.; Sander L. C.; Gu X.; Nguyen T.; Wise S. A.; Gajewski D. A. C30 Self-Assembled Monolayers on Silica, Titania, and Zirconia: HPLC Performance, Atomic Force Microscopy, Ellipsometry, and NMR Studies of Molecular Dynamics and Uniformity of Coverage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (29), 6997–7011. 10.1021/ja993705d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L. C.; Lippa K. A.; Wise S. A. Order and Disorder in Alkyl Stationary Phases. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 382 (3), 646–668. 10.1007/s00216-005-3127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Qiu H.; Oishi T.; Kuwahara Y.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Design of C18 Organic Phases with Multiple Embedded Polar Groups for Ultraversatile Applications with Ultrahigh Selectivity. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87 (13), 6614–6621. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens H. A.; Van Straten M. A.; Cramers C. A.; Jezierska M.; Buszewski B. Comparative Study of Test Methods for Reversed-Phase Columns for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 826 (2), 135–156. 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00749-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buszewski B.; Schmid J.; Albert K.; Bayer E. Chemically Bonded Phases for the Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Separation of Basic Substances. J. Chromatogr. A 1991, 552, 415–427. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)95957-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt H.; Arangio M.; Lobert T. A Chromatographic Test Procedure for Reversed-Phase HPLC Column Evaluation. LC GC Europe 1997, 15 (9), 856–866. [Google Scholar]

- Euerby M. R.; Petersson P. Chromatographic Classification and Comparison of Commercially Available Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatographic Columns Using Principal Component Analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 994 (1–2), 13–36. 10.1016/S0021-9673(03)00393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. K.; Horváth C. Evaluation of Substituent Contributions to Chromatographic Retention: Quantitative Structure-Retention Relationships. J. Chromatogr. A 1979, 171, 15–28. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)95281-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler J.; Chase D. B.; Farlee R. D.; Vega A. J.; Kirkland J. J. Comprehensive Characterization of Some Silica-Based Stationary Phase for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1986, 352, 275–305. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)83386-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majors R. E.; MacDonald F. R. Practical Implications of Modern Liquid Chromatographic Column Performance. J. Chromatogr. A 1973, 83, 169–179. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)97036-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neue U. D.; van Tran K.; Iraneta P. C.; Alden B. A. Characterization of HPLC Packings. J. Sep. Sci. 2003, 26 (3–4), 174–186. 10.1002/jssc.200390025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sander L. C.; Wise S. A. Shape Selectivity in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography for the Separation of Planar and Non-Planar Solutes. J. Chromatogr. A 1993, 656 (1–2), 335–351. 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80808-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata K.; Iwaguchi K.; Onishi S.; Jinno K.; Eksteen R.; Hosoya K.; Araki M.; Tanaka N. Chromatographic Characterization of Silica C18 Packing Materials. Correlation between a Preparation Method and Retention Behavior of Stationary Phase. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1989, 27 (12), 721–728. 10.1093/chromsci/27.12.721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Y.; Ikegami T.; Takubo H.; Ikegami Y.; Miyamoto M.; Tanaka N. Chromatographic Characterization of Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Stationary Phases: Hydrophilicity, Charge Effects, Structural Selectivity, and Separation Efficiency. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218 (35), 5903–5919. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan G. P.; Scully N. M.; Glennon J. D. Polar-Embedded and Polar-Endcapped Stationary Phases for LC. Anal. Lett. 2010, 43 (10–11), 1609–1629. 10.1080/00032711003653973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Esch J.; Schoonbeek F.; de Loos M.; Kooijman H.; Spek A. L.; Kellogg R. M.; Feringa B. L. Cyclic Bis-Urea Compounds as Gelators for Organic Solvents. Chem.—Eur. J. 1999, 5 (3), 937–950. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F.; Hanke B.; Lysetska M.; Lambright G.; Harms G. S. Gelation of a Highly Fluorescent Urea-Functionalized Perylene Bisimide Dye. Org. Lett. 2005, 7 (6), 967–970. 10.1021/ol0475820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Zhang D.; Zhu D. A Low-Molecular-Mass Gelator with an Electroactive Tetrathiafulvalene Group: Tuning the Gel Formation by Charge-Transfer Interaction and Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127 (47), 16372–16373. 10.1021/ja055800u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medda A. K.; Park C. M.; Jeon A.; Kim H.; Sohn J. H.; Lee H. S. A Nonpeptidic Reverse-Turn Scaffold Stabilized by Urea-Based Dual Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. Org. Lett. 2011, 13 (13), 3486–3489. 10.1021/ol201247x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesciotta E. N.; Bornhop D. J.; Flowers R. A. Backscattering Interferometry: An Alternative Approach for the Study of Hydrogen Bonding Interactions in Organic Solvents. Org. Lett. 2011, 13 (10), 2654–2657. 10.1021/ol200757a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitza M.; Wegmann J.; Bachmann S.; Albert K. Investigating the Surface Morphology of Triacontyl Phases with Spin-Diffusion Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39 (19), 3486–3489. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli A. E.; Schilling F. C.; Bovey F. A. Conformational origin of the nonequivalent carbon-13 NMR chemical shifts observed for the isopropyl methyl carbons in branched alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106 (4), 1157–1158. 10.1002/chin.198421061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleiderer B.; Albert K.; Bayer E.; Lork K. D.; Unger K. K.; Brückner H. Correlation of the Dynamic Behavior of N-Alkyl Ligands of the Stationary Phase with the Retention Times of Paracelsin Peptides in Reversed Phase HPLC. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1989, 28 (3), 327–329. 10.1002/anie.198903271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson M.; Unger K. K.; Schmid J.; Albert K.; Bayer E. Effect of the Chain Mobility of Polymeric Reversed-Phase Stationary Phases on Polypeptide Retention. Anal. Chem. 1993, 65 (17), 2249–2253. 10.1021/ac00065a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ansarian H. R.; Derakhshan M.; Mizanur Rahman M.; Sakurai T.; Takafuji M.; Taniguchi I.; Ihara H. Evaluation of Microstructural Features of a New Polymeric Organic Stationary Phase Grafted on Silica Surface: A Paradigm of Characterization of HPLC-Stationary Phases by a Combination of Suspension-State 1H NMR and Solid-State 13C-CP/MAS-NMR. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 547 (2), 179–187. 10.1016/j.aca.2005.05.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pursch M.; Sander L. C.; Albert K. Peer Reviewed: Understanding Reversed-Phase LC with Solid-State NMR. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71 (21), 733A–741A. 10.1021/ac990790z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursch M.; Brindle R.; Ellwanger A.; Sander L. C.; Bell C. M.; Händel H.; Albert K. Stationary Interphases with Extended Alkyl Chains: A Comparative Study on Chain Order by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 1997, 9 (2–4), 191–201. 10.1016/S0926-2040(97)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Žuvela P.; Skoczylas M.; Jay Liu J.; Baczek T.; Kaliszan R.; Wong M. W.; Buszewski B. Column Characterization and Selection Systems in Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3674–3729. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale C.; Soliven A.; Schuster S. A Simple Approach for Reversed Phase Column Comparisons via the Tanaka Test. Microchem. J. 2021, 162, 105793 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Bordunov A.; Tracy M.; Slingsby R.; Avdalovic N.; Pohl C. Development of a Polar-Embedded Stationary Phase with Unique Properties. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1119 (1–2), 120–127. 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.12.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Sawada T.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Novel Approach for the Separation of Shape-Constrained Isomers with Alternating Copolymer-Grafted Silica in Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82 (8), 3320–3328. 10.1021/ac1001178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne J. Characterization and Comparison of the Chromatographic Performance of Conventional, Polar-Embedded, and Polar-Endcapped Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography Stationary Phases. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 957 (2), 149–164. 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abidi S. L. Chromatographic Analysis of Tocol-Derived Lipid Antioxidants. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 881 (1–2), 197–216. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00131-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohschein S.; Pursch M.; Lubda D.; Albert K. Shape Selectivity of C30 Phases for RP-HPLC Separation of Tocopherol Isomers and Correlation with MAS NMR Data from Suspended Stationary Phases. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70 (1), 13–18. 10.1021/ac970414j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik A. K.; Noguchi H.; Rahman M. M.; Takafuji M.; Ihara H. Selectivity Enhancement for the Separation of Shape-constrained Isomers by Particle Size-derived Molecular Ordering and Density in Reversed-phase Liquid Chromatography. Sep. Sci. Plus 2021, 4 (8), 296–304. 10.1002/sscp.202100017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Y.; Li Wan Po A. The Effectiveness of Topically Applied Capsaicin - A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994, 46 (6), 517–522. 10.1007/BF00196108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R.; Pan J.; Xie H.; Zhou B.; Xia X. Separation and Quantitative Analysis of Capsaicinoids in Chili Peppers by Reversed-Phase Argentation LC. Chromatographia 2009, 70 (5–6), 1011–1013. 10.1365/s10337-009-1248-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara J. E.; Alden B. A.; Walter T. H.; Neue U. D.; Petersen J. S.; Niederländer C. L. Simple Preparation of a C8 HPLC Stationary Phase with an Internal Polar Functional Group. Anal. Chem. 1995, 67 (20), 3809–3813. 10.1021/ac00116a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara J. E.; Walsh D. P.; Alden B. A.; Casellini P.; Walter T. H. Systematic Study of Chromatographic Behavior vs Alkyl Chain Length for HPLC Bonded Phases Containing an Embedded Carbamate Group. Anal. Chem. 1999, 71 (15), 2992–2997. 10.1021/ac9900331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nováková L.; Solichová D.; Pavlovičová S.; Solich P. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquis Chromatography Method for the Determination of Ascorbic Acid. J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31 (9), 1634–1644. 10.1002/jssc.200700570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaki S.; Kato K.; Miyazaki T.; Musashi Y.; Ohkubo K.; Ihara H.; Hirayama C. Structures and Binding Energies of Benzene-Methane and Benzene-Benzene Complexes. An Ab Initio SCF/MP2 Study. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1993, 89 (4), 659–664. 10.1039/FT9938900659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jandera P.; Janás P. Recent Advances in Stationary Phases and Understanding of Retention in Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography. A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 967, 12–32. 10.1016/j.aca.2017.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga S.; Bocian S.; Buszewski B. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Columns Classification by Effect of Solvation and Chemometric Methods. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1278, 89–97. 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszewski B.; Noga S. Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC)-a Powerful Separation Technique. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 231–247. 10.1007/s00216-011-5308-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpert A. J. Hydrophilic-Interaction Chromatography for the Separation of Peptides, Nucleic Acids and Other Polar Compounds. J. Chromatogr. A 1990, 499, 177–196. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)96972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D. W.; Jin H. L. Evaluation of the Liquid Chromatographic Separation of Monosaccharides, Disaccharides, Trisaccharides, Tetrasaccharides, Deoxysaccharides and Sugar Alcohols with Stable Cyclodextrin Bonded Phase Columns. J. Chromatogr. A 1989, 462, 219–232. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)91349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H.; Wanigasekara E.; Zhang Y.; Tran T.; Armstrong D. W. Development and Evaluation of New Zwitterionic Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Stationary Phases Based on 3-P,P-Diphenylphosphonium-Propylsulfonate. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218 (44), 8075–8082. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Gaiki S. Retention and Selectivity of Stationary Phases for Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218 (35), 5920–5938. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.