Abstract

Background:

Updates to the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access emphasize the “right access, in the right patient, at the right time, for the right reasons.” Although this implies a collaborative approach, little is known about how patients, their caregivers, and health care providers engage in vascular access (VA) decision-making.

Objective:

To explore how the perspectives of patients receiving hemodialysis, their caregivers, and hemodialysis care team align and diverge in relation to VA selection.

Design:

Qualitative descriptive study.

Setting:

Five outpatient hemodialysis centers in Calgary, Alberta.

Participants:

Our purposive sample included 19 patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis, 2 caregivers, and 21 health care providers (7 hemodialysis nurses, 6 VA nurses, and 8 nephrologists).

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with consenting participants. Using an inductive thematic analysis approach, we coded transcripts in duplicate and characterized themes addressing our research objective.

Results:

While participants across roles shared some perspectives related to VA decision-making, we identified areas where views diverged. Areas of alignment included (1) optimizing patient preparedness—acknowledging decisional readiness and timing, and (2) value placed on trusting relationships with the kidney care team—respecting decisional autonomy with guidance. Perspectives diverged in the following aspects: (1) differing VA priorities and preferences—patients’ emphasis on minimizing disruptions to normalcy contrasted with providers’ preferences for fistulas and optimizing biomedical parameters of dialysis; (2) influence of personal and peer experience—patients preferred pragmatic, experiential knowledge, whereas providers emphasized informational credibility; and (3) endpoints for VA review—reassessment of VA decisions was prompted by access dissatisfaction for patients and a medical imperative to achieve a functioning access for health care providers.

Limitations:

Participation was limited to individuals comfortable communicating in English and from urban, in-center hemodialysis units. Few informal caregivers of people receiving hemodialysis and younger patients participated in this study.

Conclusions:

Although patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers share perspectives on important aspects of VA decisions, conflicting priorities and preferences may impact the decisional outcome. Findings highlight opportunities to bridge knowledge and readiness gaps and integrate shared decision-making in the VA selection process.

Keywords: hemodialysis, vascular access, qualitative research, shared decision-making

Abrégé

Contexte:

Les mises à jour des lignes directrices de pratiques cliniques en matière d’accès vasculaire de la KDOQI (Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative) insistent sur la création « du bon accès, à la bonne personne, au bon moment et pour les bonnes raisons ». Ces recommandations sous-entendent une approche collaborative, mais la façon dont les patients, leurs soignants et les prestataires de soins de santé participent à la prise de décision sur l’accès vasculaire (AV) demeure mal connue.

Objectif:

Explorer les accords et les divergences dans les points de vue des patients sous hémodialyse, leurs soignants et leur équipe de soins relativement à la sélection de l’AV.

Conception:

Étude qualitative et descriptive.

Cadre:

Cinq centres d’hémodialyse ambulatoire à Calgary (Alberta).

Sujets:

Notre échantillon choisi à dessein était composé de 19 patients sous hémodialyse d’entretien, 2 soignants et 21 prestataires de soins de santé (7 infirmières en hémodialyse, 6 infirmières en AV et 8 néphrologues).

Méthodologie:

Nous avons mené des entrevues semi-structurées auprès des participants consentants. Une approche d’analyse thématique inductive a été employée pour coder les transcriptions en double et caractériser les thèmes répondant à l’objectif de recherche.

Résultats:

Certains points de vue sur la prise de décision en matière d’AV étaient partagés par tous les participants, mais nous avons identifié quelques domaines de divergence. Les participants s’entendaient sur : 1) l’optimisation de la préparation des patients — reconnaître l’état de préparation et le moment de prendre la décision; et 2) la valeur accordée aux relations de confiance avec l’équipe de soins rénaux — respecter l’autonomie décisionnelle après conseils. Les points de vue divergeaient sur : 1) les priorités et préférences à l’égard de l’AV — l’accent mis par les patients sur la minimisation des perturbations de la vie courante contrastait avec les préférences des prestataires de soins pour les fistules et l’optimisation des paramètres biomédicaux de la dialyse; 2) l’influence de l’expérience personnelle et des pairs — les patients préféraient des connaissances pragmatiques et expérientielles, tandis que les prestataires de soins mettaient l’accent sur la crédibilité de l’information; et 3) les critères d’évaluation de l’AV — la réévaluation du choix de l’AV est motivée par l’insatisfaction des patients à l’égard de l’accès et, du côté des prestataires de soins, par l’impératif médical de parvenir à un accès fonctionnel.

Limites:

Seules les personnes fréquentant une unité d’hémodialyse en centre urbain et à l’aise de communiquer en anglais ont pu participer. Les participants comptaient peu de patients plus jeunes et de soignants informels de personnes sous hémodialyse.

Conclusion:

Bien que les patients, les soignants et les prestataires de soins de santé s’entendent sur certains aspects importants de la décision concernant l’AV, celle-ci pourrait être influencée par des priorités et préférences contradictoires. Nos résultats mettent en évidence des occasions d’intégrer la prise de décision partagée dans le processus de sélection d’un AV et de combler les lacunes dans les connaissances et la préparation des patients.

Introduction

More than 2.5 million people worldwide receive kidney replacement therapy as life-sustaining treatment for kidney failure, and this number is expected to double by 2030.1,2 As the most common form of kidney replacement therapy, hemodialysis requires a safe, reliable mechanism to access the bloodstream, termed vascular access (VA). 3 Historically, arteriovenous fistulas were recommended as first-line VA due to lower complication rates and mortality than its alternatives, arteriovenous grafts or central venous catheters, reported in observational studies.4-6 Vascular access selection has been largely driven by patients’ eligibility for an arteriovenous fistula, although contemporary data suggesting access type alone does not explain the difference in observed outcomes have challenged the “fistula first” approach.7-9 As one VA type is not clearly superior under all circumstances, health care providers and patients are increasingly engaging in individualized approaches to VA selection.10,11

Shared decision-making is recommended as a collaborative approach to medical decisions, particularly when no single best option exists. 12 Patients and their loved ones actively participate in shared decision-making by discussing their values and preferences with their health care providers, who share clinical knowledge, expertise, and best available evidence about risks and benefits.12,13 In recent qualitative work by our group characterizing conditions that favor and undermine VA-related shared decision-making, patients and health care providers emphasized upstream decisions about dialysis over VA type and a need for iterative, balanced discussions, and they recognized how failure to enact timely decisions about VA almost always resulted in hemodialysis via a central venous catheter. 14 As the success of shared decision-making relies in large part on establishing mutual understanding of one another’s perspectives, an important question arising from this work is the extent to which patients’ and caregivers’ views on VA decisions align with those of health care providers. Whereas other reports suggest that patients weigh anticipated VA benefits with complication risks and impacts on daily life15-18 and health care providers prioritize reliable and durable VA,19-22 to our knowledge no study has compared the perspectives of patients and health care providers on aspects of the VA decisional process qualitatively.

With Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access emphasizing the “right access, in the right patient, at the right time, for the right reasons,” 23 VA clinicians are compelled to consider individuals’ circumstances, priorities, and values alongside their medical eligibility for a given access type. Recognizing their unique roles in the VA decision, an appreciation of the similarities and differences among the perspectives of patients, their caregivers, and health care providers on this issue is a critical first step toward shared decision-making in VA practice. Whereas shared views can identify common goals and how to achieve them, areas of divergence may suggest opportunities to bridge gaps in decision-making needs. Thus, to address a distinct and complementary research question emerging during our study of VA-related shared decision-making, we sought to explore the alignment among the perspectives of patients receiving hemodialysis, their caregivers, and health care providers regarding hemodialysis VA selection.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We used a qualitative descriptive methodology to guide our study.24,25 This approach allows for exploration of insights regarding phenomena, such as VA selection, with implications for clinical practice. 26 This study took place across 5 outpatient, in-center hemodialysis units in the Alberta Kidney Care–South program in Alberta, Canada. We adhered to principles of rigor in qualitative research, including clear statement of purpose, data collection, and analytic techniques appropriate to the methodology, provision of data extracts to support our findings, researcher and data triangulation, and reflexive note taking. 27 We have reported this study in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research. 28 The University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (REB18-1727).

Participants

Participants included adults ≥18 years of age from one of the following eligible groups: patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis for >3 months via an arteriovenous fistula or central venous catheter, their informal caregivers, and health care providers for people undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (ie, nephrologists, hemodialysis nurses, and VA nurses). Patients were excluded if they had a life expectancy of <1 year, cognitive impairment, or inability to communicate in English. Using a maximum variation approach, we sampled participants across relevant sociodemographic (age, sex, etc) and clinical characteristics (eg, dialysis duration and VA history [patients] and clinical role [health care providers]) to capture a range of experiences. A hemodialysis clinician identified eligible patients and health care provider participants, whom the research coordinator approached to discuss the study and assess their interest in participating. Eligible patients were asked to nominate potential caregiver participants, whom the research coordinator approached separately by telephone if not present during hemodialysis. Participants provided informed consent prior to each interview.

Data Collection

A research coordinator (S.L. and M.O.) with qualitative research training and experience conducted semi-structured interviews in person in hemodialysis units or by telephone, depending on participant preference, that lasted 20 to 60 minutes. The interviewer had no prior knowledge of study participants. We developed and pilot tested distinct interview guides for patients/caregivers and health care providers to explore their needs, experiences, and perceived roles related to VA decision-making (Supplementary Material). Both interview guides included open-ended questions with prompts to elicit participants’ experiences of selecting and/or living with VA. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, except for one patient interview where detailed notes were taken instead at the participant’s request. Data saturation, defined as the point at which no new information was produced from interviews, was attained. 29 We collected demographic data from all participants for the purposes of summarizing our sample and informing recruitment of potential participants by the research coordinator in hemodialysis centers to achieve a diverse sample in keeping with our purposive sampling approach.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were uploaded into NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd) to facilitate data management and storage. Two research team members (A.S. and M.J.E.) used a thematic analysis approach to inductively and systematically code, analyze, and interpret the data to address our emergent research question after data collection was completed.30-32 We first reviewed interviews repeatedly to obtain a high-level understanding of the data and key concepts. We discussed the ideas raised by patients, their caregivers, and health care providers and generated initial, descriptive codes to capture distinct concepts. We applied preliminary codes to transcripts independently and in duplicate and met after every 3 to 4 transcripts to revise our coding scheme. We then applied final codes systematically across remaining transcripts. We developed separate coding schemes for patients/caregivers and health care providers to identify unique concepts arising from different participant types. The 2 team members compared and contrasted codes and organized them into preliminary themes. We refined final themes through team discussion and presented them as key concept areas in which patient/caregiver perspectives on VA selection aligned with or diverged from those of health care providers.

Results

In total, 42 individuals participated in this study (19 patients, 2 caregivers, and 21 health care providers). We conducted interviews by telephone with 23 participants and in person with 19 participants. Most patients (n = 12) had initiated hemodialysis less than 1 year previously. Most patients (n = 15) started hemodialysis using a catheter, and over half were dialyzing with a fistula at the time of interview (n = 10) (Table 1). Six patient participants had experience with both VA types. The 2 caregivers were spouses of patient participants in the study. Participating health care providers included 8 nephrologists, 7 hemodialysis nurses, and 6 VA nurses; most were women and had a range of clinical experiences (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patient (n = 19) and Caregiver Participants (n = 2).

| Demographic characteristic (patients and caregivers) | n = 21 |

|---|---|

| Role | |

| Patient | 19 |

| Caregiver | 2 |

| Gender | |

| Man | 15 |

| Woman | 6 |

| Age (years) | |

| Below 40 | 1 |

| 40-64 | 12 |

| 65 or above | 8 |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 5 |

| High school diploma | 2 |

| College diploma | 3 |

| University degree | 10 |

| Not reported | 1 |

| Employment | |

| Full time | 3 |

| Retired | 10 |

| Other (disability, student, not employed) | 8 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 11 |

| Single | 5 |

| Divorced, separated | 3 |

| Common law | 1 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Living situation | |

| With spouse only | 10 |

| Alone | 6 |

| With other family | 3 |

| With spouse and other family | 1 |

| Other | 1 |

| Clinical characteristic (patients) | n = 19 |

| Time on hemodialysis (months) | |

| 3-12 | 12 |

| 13-24 | 4 |

| Above 24 | 3 |

| Initial vascular access type | |

| Central venous catheter | 15 |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 4 |

| Current vascular access type | |

| Central venous catheter | 9 |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 10 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Health Care Provider Participants (n = 21).

| Characteristic | n = 21 |

|---|---|

| Role | |

| Nurse (VA nurse, hemodialysis nurse) | 13 |

| Nephrologist | 8 |

| Gender | |

| Man | 6 |

| Woman | 15 |

| Age (years) | |

| Below 40 | 3 |

| 40-64 | 16 |

| 65 or above | 2 |

| Time in clinical practice (years) | |

| 5 or less | 2 |

| 6-10 | 2 |

| 11-20 | 5 |

| 21-30 | 7 |

| Above 30 | 5 |

| Time dedicated to clinical practice (%) | |

| Above 50 | 18 |

| 25-50 | 3 |

| Less than 25 | 0 |

Note. VA = vascular access.

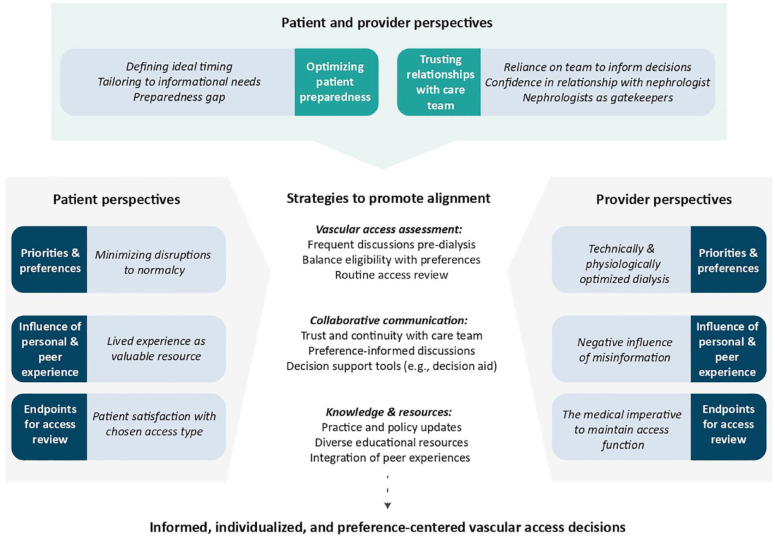

We identified 2 themes where patient, caregiver, and health care provider perspectives aligned in VA decision-making: (1) optimizing patient preparedness, and (2) value placed on trusting relationships with the kidney care team. We characterized 3 themes where patient and caregiver perspectives diverged from those of health care providers: (1) access priorities and preferences, (2) influence of personal and peer experience, and (3) endpoints for VA review. Relationships between themes are depicted in Figure 1, and exemplar quotes supporting each theme and conceptual category are provided in Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 1.

Patient and health care provider perspectives on vascular access–related decision-making.

Note. Themes highlight where perspectives align and diverge and potential strategies to promote individualized and preference-centered vascular access decisions.

Table 3.

Exemplar Quotes for Themes and Subthemes of Perspective Alignment Among Patients, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Providers.

| Theme 1: Optimizing patient preparedness | |

|---|---|

| Defining ideal timing | |

| Quote 1a | “I stayed at 20 percent [glomerular filtration rate, GFR] way longer than a lot of people, and I think they thought I was going to stay at that level for a long time. I went from 20 to 10 really fast.” (Patient 19) |

| Quote 1b | “So today your GFR could be 15 [mL/min] and now it’s four. They end up in the [emergency department] with a fractured hip. Blood work is such that they need an urgent dialysis start.” (Nurse 3) |

| Quote 1c | “When their kidney function or GFR drops to about 10-15 we start having that [access] discussion seriously. . . I find that if you do it too early it gives a lot of anxiety, and they may not need that information for months. I find that if you give it too early, they are just not going to retain it.” (Nephrologist 4) |

| Quote 1d | “Generally, when I start bringing up the conversation about access is usually around a GFR of 15 [mL/min]. That, of course, would depend on the trajectory of a patient.” (Nephrologist 7) |

| Tailoring to informational needs | |

| Quote 1e | “I think they have to tease out for that person what’s the best way to learn, or are you understanding what I’m telling you.” (Nurse 13) |

| Quote 1f | “We need to be doing an assessment of their health literacy and how do they learn, and what’s their knowledge of where things are at. Often I think we have one-size-fits-all approach to things, but people are very different and we have to understand how people actually make their decisions.” (Nephrologist 6) |

| Quote 1g | “I just think that everybody is so different. Like there’s people who really want to know everything, so if that’s your personality then definitely do all the research you can, but if you are like me, honestly, I just think it was meant to be, like this is the way I am.” (Patient 5) |

| Quote 1h | “Sometimes being able to see it and ask questions at the time is more helpful than just seeing it in a brochure.” (Caregiver 2) |

| Preparedness gap | |

| Quote 1i | “I have a good doctor, I have a good nurse, but I don’t think I got a lot of information. . . . They told me there was the two types, but that was it.” (Patient 2) |

| Quote 1j | “I think that just the notion of going into kidney failure overwhelms people, and even with the information that we give people, I don’t necessarily feel that they understand the decisions that they are making until after the decision has been made, particularly about fistulas.” (Nephrologist 7) |

| Quote 1k | “Maybe I don’t remember, but I don’t think they gave me any education on that [fistulas] . . . I was always wondering ‘how are they going to connect me to the machine?’ because with the catheter I have those two tubes, but [with a fistula], I don’t know.” (Patient 10) |

| Quote 1l | “Sometimes [patients] say, ‘Oh, the doctor never talked to me about this’. I think partially due to the patient not having a willingness to discuss it or they’re in denial about the fact that they’ll ever need [dialysis].” (Nurse 13) |

| Theme 2: Value placed on trusting relationships with care team | |

| Reliance on the healthcare team to inform decisions | |

| Quote 2a | “I like the way they presented it. They just said, these are the pros and the cons and so you know what to expect with either option. I thought I was able to make a really good decision based on that.” (Patient 13) |

| Quote 2b | “It [access selection] really depends on exploring with the patient what’s important to them in their lives and making sure they have the knowledge to make the best decision possible.” (Nurse 9) |

| Quote 2c | “I was just not in the headspace to read anything or do anything, so I just kind of left it up to him [nephrologist] and just trusted him.” (Patient 5) |

| Quote 2d | “At the end of the day, a large proportion of the patients would say—‘What do you think? What would you recommend?’” (Nephrologist 5) |

| Confidence in longitudinal relationship with nephrologist | |

| Quote 2e | “I think [nephrologist] has been really good about talking what’s going to suit your lifestyle, like, what’s going to suit you best, which is great.” (Patient 18) |

| Quote 2f | “I still think the best decision would be after discussion between the patient and the primary nephrologist. Because the primary nephrologist knows the total medical background of the patient, and the primary nephrologist may have preferences based on, say, I know my patient, he is so fearful of pain so why would I insist to have a fistula?” (Nurse 5) |

| Nephrologists as gatekeepers | |

| Quote 2g | “The doctor didn’t ask me whether I liked it or not. I didn’t know, [about] this or that. He did the surgery and I was very happy.” (Patient 1) |

| Quote 2h | “For older people who use dialysis as a trial, I mean that they are older, they are sitting on the fence [about dialysis]. Then we say, well you can always have a trial. For patients starting dialysis as a trial, I don’t even mention a fistula.” (Nephrologist 5) |

| Quote 2i | “We usually email the nephrologist first, just to ask if we can talk to their patient and discuss vascular access options. . . So it will depend on their answer, if they tell us the patient is a [fistula] candidate, or maybe we hold off for a bit before talking to them. . . . It’s still the nephrologist that makes that decision.” (Nurse 11) |

Table 4.

Exemplar Quotes for Themes and Subthemes of Perspective Divergence Among Patients, Caregivers, and Health Care Providers.

| Patients and caregivers | Health care providers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 3: Differing vascular access priorities and preferences | |||

| Minimizing disruptions to normalcy | Desire for technically and physiologically optimized dialysis | ||

| Quote 3a Quote 3b Quote 3c Quote 3d Quote 3e Quote 3f |

“I didn’t realize how much the needles hurt going [in], and you’ve got to do a different spot each time and that wasn’t for me.” (Patient 9) “With the central line, you have two hands being able to manipulate to make it connect up. If you have a fistula, you just have the one hand that you are relying on . . . So we didn’t really see any benefit of that one [fistula].” (Caregiver 2) “I think if I was told you’ll never receive a transplant, there’s no option, I would probably move to a fistula . . . just because of the thought of, for the rest of your life you can never go swimming, go in the ocean, have a proper bath or shower [with a catheter]. That’s a little tough to swallow.” (Patient 19) “I needled [my fistula] for a short time, but the thing that made my decision was when my daughter one night helped me. We spent three hours and we could not get the needle in, and I said, ‘I’m not doing this much longer’, because my dialysis is only for four [hours], but now all of a sudden to get it in and out, I’m talking about, another four . . . Sorry, I don’t have that much time to give.” (Patient 3) “I was a guitar player, so they talked about which is the better arm to go in so I could continue to play guitar, because I didn’t want to lose [my non dominant arm], and they weren’t really interested. They said, ‘Yeah we prefer to leave your dominant arm to be able to use’. That’s probably more convenient to them than my guitar, right.” (Patient 3) “I really did not want anything sticking out of my body, like tubes or anything like that. So, the fistula was for me the immediate go-to option that I wanted to do. There was no question about it. I mean, I felt [my] life would be changed significantly with just having to do dialysis. I didn’t want to have to deal with more changes with appearance.” (Patient 13) |

Quote 3g Quote 3h Quote 3i Quote 3j Quote 3k Quote 3l |

“Well from my perspective, I tell all patients that the fistula is your best option because there is much less, if any, recirculation, whereas a catheter has recirculation at any pump speed, and that amount of circulation diminishes the effectiveness of that dialysis treatment.” (Nephrologist 1) “You can describe some of the pros of the fistula, like maybe you can get higher flows, maybe you get better clearance. . . I just try and provide as unbiased an opinion as possible, but if they are going to need dialysis for five, 10 years or longer, I do try and encourage the fistula first as an option.” (Nephrologist 3) “I’m not opposed to [‘fistula first’ policy]. I think there needs to be caveats, like an asterisk, in regards to the patient selection. I’ve seen enough times where we put the fistula in and the patient ends up having trouble using it and they end up just getting catheter and sticking with the catheter afterwards. So, I do agree in principal with having fistula [first], but I think that we need to be a little bit careful with choosing the right patient population.” (Nephrologist 4) “I still feel fistulas come first . . . we were encouraged by our manager to, day one, visit them and talk about fistulas right off the bat.” (Nurse 3) “I kind of like the [‘fistula first’] idea actually, but I don’t know the process of why refer patient to catheter first versus fistula.” (Nurse 8) “No [does not have a vascular access preference]. It’s more along the lines of, as long as it’s a functioning catheter or fistula, that’s what we want.” (Nurse 9) |

| Theme 4: Influence of personal and peer experience | |||

| Lived experience as a valuable resource | Negative influence of misinformation | ||

| Quote 4a Quote 4b Quote 4c Quote 4d Quote 4e |

“[Spouse’s] case was a little bit unique in that he’d had those [dialysis] experiences before already, so he knew very clearly what he wanted. . . For me, it was a learning experience. . . You get all of this training about what to do in case something goes wrong and then you are left with this feeling of—well they didn’t tell me what everything working would feel like.” (Caregiver 1) “I ran into a fellow once when I was going through blood tests. He got a kidney transplant, and he told me which [access] is the better one, which is the not so good one, you know . . . just a gentleman who was at the lab.” (Patient 14) “To be honest, that’s the way you find out most things, patients talk among themselves. You share experiences and you start to learn a lot more.” (Patient 15) “I was walking through there, I kind of peeked in where they were doing the [hemodialysis], and walked through there a little bit, and then I thought, well, you know, they are all doing it that way, that looks like the best way.” (Patient 16) “He [brother] had a transplant, so he had catheter, and I know based on how he was experiencing it that he didn’t like dealing with it because he had to make sure it was clean. He developed an infection at one point and so that was the major factor for me.” (Patient 13) |

Quote 4f Quote 4g Quote 4h Quote 4i Quote 4j |

“They [patients] come with a lot of preconceived notions because a lot of discussion happens in our waiting room. They look at each other’s arms and see the big bumps, or they hear the stories, like, ‘I’m having problems with my needling’, or ‘I blew [my fistula] last time’, or ‘Don’t get that nurse, get this nurse’. . . So a lot of times it’s just trying to get people the facts as opposed to the gossip.” (Nurse 2) “It’s usually the patient, the nurse, and myself [involved in access conversations] because my concern would be that different points of view will confuse the patient as to what their options are and what their preferences might develop into.” (Nephrologist 1) “We’ve had issues with, like, some of our younger patients are in the waiting room and they’ll see those patients that have the fistulas that are massive, that you can see across the room, you can see the deformity of the arm. So they see those, and it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m never going to have that.’” (Nurse 9) “The other approach that has been tried, and it has mixed reviews, is that you have a forum where patients come and they discuss various things, good and bad, about aspects of dialysis including the access. The problem is that it becomes information overload for the new patient, and they sort of throw their hands in the air and say, ‘Well, that didn’t help me make a decision’, and they come back to the physician to have him make it for them.” (Nephrologist 1) “If we are going to talk about hemodialysis, we will say there are two different accesses—one is a catheter, one is a fistula that is surgically created. [A catheter] has about 90 times or 80 times more infections than the fistula but the same mortality rate, and on average fistulas fail 30-40% [of the time] when they first surgically create them.” (Nephrologist 2) |

| Theme 5: Endpoints for vascular access review | |||

| Patient satisfaction with chosen access type | The medical imperative to maintain access function | ||

| Quote 5a Quote 5b Quote 5c |

“I haven’t really felt the need to try something different because this has gone fairly well for me, I think.” (Patient 18) “If I would have known the trouble I had with my fistula, I never would have had it done . . . [A fistula] wasn’t for me. It’s because I was getting too many clots. I was getting lumps in my arm and it hurt like hell.” (Patient 9) “I mean, there was a lot of pressure at the time to go that route [fistula], because [healthcare providers] were concerned about infection, and you were almost given the impression there wasn’t really a choice.” (Patient 15) |

Quote 5d Quote 5e Quote 5f |

“I think the biggest challenge is if we can’t seem to get a working access after the patient has committed to a choice. I think that’s one of the things that is a bit annoying, so to speak.” (Nephrologist 4) “The line [catheter] works or it doesn’t work, and if it becomes a problem, then I go back to them and I say, ‘Well, you had your chance with the line—what do you think? Do we want to try the fistula now?’ And sometimes they bite, and sometimes they say let’s make the best of the line if we can even though it might involve several changes.” (Nephrologist 1) “I would say [reviewing access choice] as soon as possible, because the fistula needs the time to create and then needs the time to mature.” (Nurse 12) |

Perspective Alignment

Optimizing patient preparedness

Patients, their caregivers, and health care providers all identified the importance of adequately preparing patients for decisions about VA, yet acknowledged the difficulty of timing and engaging in VA decisions well in advance of dialysis need (Table 3). Despite efforts to address patient and caregiver knowledge gaps, participants noted that most patients lacked readiness to make informed decisions about dialysis and VA.

Defining ideal timing

Participants across roles discussed how difficulty predicting when a person might require kidney replacement therapy made it challenging to plan for VA discussions in predialysis kidney care programs (quotes 1a-b). Whereas several patients indicated that delaying conversations about access led to insufficient time for deliberation about their options, providers described how premature access discussions could lead to low information retention and precipitate unnecessary anxiety (quote 1c). Nephrologists suggested introducing dialysis modality and transplant options followed by VA when patients’ eGFR declines below 10 to 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or they are progressing rapidly toward kidney failure (quotes 1c-d).

Tailoring to informational needs

Patients and providers emphasized the need to adapt the content of access discussions to patients’ informational needs (quotes 1e-g). Patients and caregivers varied in the amount, type, and format of information they felt was needed to support an informed, confident VA decision (quotes 1g-h)—whereas most appreciated the educational sessions provided by their care team and/or materials they could review independently, some suggested this information was difficult to digest and heightened their fears about dialysis. Participants across roles agreed that information should be shared in an incremental, iterative, and individualized manner to avoid overwhelming patients preparing for kidney failure.

Preparedness gap

Even where repeated discussions about VA options take place during clinical encounters, participants across roles noted that many patients lacked knowledge and confidence to select a VA when a decision was needed (quotes 1i-j). Some patients did not recall having discussed VA with their health care providers, and several had unanswered questions at the time of fistula or catheter placement that they felt should have been addressed earlier in their disease course (quote 1k). These included how different access types are established and used (eg, surgery and needling with a fistula), how to care for their access (eg, keeping a catheter clean), and impact of each VA type on activities (eg, ability to swim). One nurse suggested that patients’ lack of readiness or willingness to receive VA information adversely influenced their attempts to close this preparedness gap (quote 1l).

Value placed on trusting relationships with the kidney care team

Participants discussed how trusting relationships between patients and their healthcare providers facilitated VA decision-making. Moreover, once a decision about VA was made or needed imminently, enacting that decision ultimately required physician support (Table 3).

Reliance on the healthcare team to inform decisions

Patient and provider participants noted how the degree of desired autonomy in VA decisions varies across individual patients. While some patients held firm preferences for VA types and advocated for their choice, many patients and their loved ones relied on their kidney care providers to guide the decision-making process (quotes 2a-b). Providers suggested that patients who play an active role in the VA decision are more likely to pursue a fistula, which they recognized as invariably requiring more advanced planning than a catheter. However, several patients described not having a clear VA preference or not being ready to select one access type and deferring the decision to their nephrologist, whom they trusted to make the “right” decision in their best interests (quotes 2c-d).

Confidence in longitudinal relationship with nephrologist

Patients, their caregivers, and other health care providers identified the nephrologist as the provider who knows the patient best through longitudinal relationships established early in their kidney disease journey. Patient and nurse participants described turning to the primary nephrologist for guidance about VA decisions given their breadth of clinical experience and knowledge of their patients’ medical status, preferences, and support structures (quotes 2e-f).

Nephrologists as gatekeepers

Although many health care providers discussed the importance of informed decision-making about VA with support from their care team, participants across roles indicated how establishing VA could only proceed with endorsement from the physician, meaning the nephrologist or access surgeon must ultimately approve the request to create a fistula or place a catheter (quotes 2g-h). Participants suggested that although the decision about VA ultimately lay with the nephrologist, it should be informed by previous discussions and patients’ expressed preferences where possible (quote 2i).

Perspective Divergence

Differing VA priorities and preferences

Most patients and their caregivers prioritized minimizing disruptions to their predialysis life over a specific access type. This contrasted with health care providers’ prioritization of physiologically and technically optimized hemodialysis, resulting in a predominant preference for fistulas (Table 4).

Minimizing disruptions to normalcy

Patients did not uniformly prefer one access type over another, but rather that which would optimize their quality of life. For some, this meant minimizing pain and technical difficulty associated with the creation, potential revision, and use of a fistula (quotes 3a-b). For others, this included maintaining their ability to engage in recreational activities and minimizing time dedicated to dialysis-related tasks (quotes 3c). For example, one patient described how the additional time required to needle his fistula underlay his preference for a catheter, and another worried about how fistula creation in his nondominant hand might affect his ability to play the guitar (quotes 3d-e). Several patients also described wanting to avoid notable changes to their physical appearance, which might occur with both access types—whereas some preferred a catheter that they could hide under clothing, others preferred a fistula to avoid living with a visible device (quote 3f).

Desire for technically and physiologically optimized dialysis

Nephrologists largely prioritized physiological optimization and access longevity, resulting in a predominant preference for fistulas (quote 3g-h). However, they acknowledged that fistulas were not suitable for all patients and endorsed instead an approach that one nephrologist referred to as fistula first with “caveats” (quote 3i). In other words, they preferred a fistula for someone they perceived was an ideal candidate (eg, younger age, suitable vascular anatomy, and anticipated long-term hemodialysis) but indicated that a catheter would be a reasonable alternative under many circumstances, such as shorter life expectancy, unfavorable vascular anatomy, or anticipated transplantation.

Most VA nurses, whose training had largely encouraged fistula use, indicated a preference for fistulas for most individuals (quotes 3j-k). In contrast, bedside hemodialysis nurses did not express a preferred access type but rather whichever VA would facilitate a complete dialysis session free of technical complications (quote 3l). Despite acknowledging their VA preferences, most providers discussed attempts to balance their own priorities with those of their patients and individualize VA choice to their medical and personal context.

Influence of personal and peer experience

Patients and their caregivers discussed the value of their own and others’ experiences as an important resource for access-related decision-making (Table 4). Health care providers described how others’ negative VA experiences could unduly influence patients’ decisions and underscored a need for accurate, unbiased information.

Lived experience as a valuable resource

Patients discussed how their own prior experiences with VA influenced their willingness to consider a given access type (quote 4a). For example, patients who had experienced catheter infections or fistula revisions described being more likely to opt for the alternative when presented with the choice. They also described learning about living with hemodialysis and VA from other patients, whose anecdotes often centered on negative experiences with a given access type and left lasting impressions on patients making VA decisions (quotes 4b-e).

Negative influence of misinformation

While healthcare providers acknowledged the potential positive impact of others’ lived experiences on access decisions, they cautioned that fixating on poor VA experiences or outcomes could perpetuate misinformation (quote 4f-g). Several nurses and nephrologists gave the example of a patient observing aneurysmal fistula dilatation and concluding that this was an inevitable outcome (quote 4h). They recognized that patients may have difficulty discerning the accuracy of VA information and indicated it was providers’ responsibility to ensure patients have access to varied, pragmatic, and evidence-informed resources on the risks and benefits of VA options (quotes 4i-j).

Endpoints for VA review

While participants across roles conveyed the importance of reviewing VA selection once established, they differed in the indications and timing prompting VA reassessment (Table 4).

Patient satisfaction with chosen access type

Patients and caregivers appreciated periodic check-ins from their health care providers to ensure ongoing VA satisfaction. However, unless they had experienced complications, access-related pain, or repeated access interventions, they indicated they were unlikely to want to switch to the alternative VA type (quote 5a). Conversely, unintended negative VA sequelae, such as pain and needling difficulty described by one patient upon their switch from catheter to fistula, led to dissatisfaction and a desire to review their chosen access type (quote 5b). Some patients with catheters disclosed feeling pressured to pursue a fistula as a result of routine VA review initiated by health care providers, regardless of their satisfaction with their existing catheter (quote 5c).

The medical imperative to maintain access function

While health care providers wanted patients to be satisfied with their chosen VA, they indicated that regular access review went hand in hand with assessment of the ongoing safety and efficacy of hemodialysis. Nephrologists and VA nurses described a professional responsibility to review VA proactively both before and after starting hemodialysis and identify complications early that might prompt intervention or a change in VA type, such as progressive central vein stenosis from catheter use or poor fistula maturation (quote 5d). Health care providers acknowledged their tendency to review patients with catheters more readily than those with fistulas, which they related to their training, preferences for fistulas, and/or recognized need for advanced planning to establish a fistula (quotes 5e-f).

Discussion

In characterizing the perspectives of patients, their caregivers, and health care providers related to hemodialysis VA decision-making, we identified opportunities and strategies to promote alignment and collaboration in the VA selection process (Figure 1). Although participants recognized the importance of timely information sharing and a strong foundation of trust in the care relationship, they noted that many patients remained underprepared to choose their preferred access when a decision was needed. Our observed differences in perspectives across participant roles could challenge the VA decision-making process when, for example, providers’ preferences for a given access type influence how access options are introduced and reviewed or if they conflict with patients’ own priorities and goals. The experiences of patient participants and others with specific access types emerged as a valuable resource that could help patients prepare for decisions about VA, provided the information is credible and accurate.

Our findings underscore variability in the extent to which patients and their caregivers want to engage in VA decision-making—while some preferred a greater degree of involvement, others deferred the decision to their providers, particularly their nephrologist. This finding is compatible with medical decision-making literature that distinguishes patient participation in decision-making processes from decisional autonomy. 33 Whereas patients may defer a decision for reasons, including lack of medical and experiential knowledge or perceived contextual barriers (eg, too little time to decide), most want to be involved in the deliberative processes leading up to the decision.34-36 As “deciding not to decide” about VA would nearly always lead to central venous catheter placement as the most accessible and least invasive option,14,37 our findings underscore how reviewing the implications of VA options and patients’ preferences can engage patients in the decisional process, even for those who choose to defer the decision.

When providers neglect to initiate or invite patients to engage in decision-making discussions, patients may be unsure if or how they are meant to contribute.35,38 In an international survey on VA-related decision priorities, the low priority assigned by providers to patient involvement in care suggests the role of patients in VA selection may be underappreciated and that providers may not sufficiently consider patients’ needs and values in the decision. 20 For many providers, involving patients in decision-making does not come naturally but is a learned skill that requires training and practice.39,40 A historical lack of patient involvement in VA selection and clinician familiarity and experience with shared decision-making may amplify the VA “preparedness gap” identified by our study participants. 10

Patients’ prioritization of enhanced quality of life contrasted with health care providers’ focus on delivery of complication-free dialysis through access longevity and physiological optimization of dialysis delivery. Although these are not mutually exclusive, for some patients prioritizing access functionality and longevity comes at the cost of pain, procedures, and complications (eg, fistula aneurysm). 41 Participants indicated that most VA informational resources available to patients tend to focus on the medical risks and benefits of each access type and underemphasize their implications for day-to-day living. Across roles, participants suggested that integration of hands-on experiences into VA patient education, including exposure to others with experience of different VA types, could help patients anticipate the impact of VA on quality of life while minimizing inaccuracies that may be shared during informal peer encounters.42-44

Most health care providers expressed a preference for fistulas or, at minimum, an individualized approach to access selection, whereas patients did not endorse a uniformly preferred VA type. Providers’ support for a “fistula first” approach may reflect their training, adherence to historical guideline recommendations or local policy, and the fact that while no randomized trial evidence has demonstrated fistula superiority over catheters, no compelling data have suggested fistula inferiority either.7,45 In a 2014 survey of European VA experts, 85% of respondents indicated the evidence base was sufficiently robust to support a “fistula first” policy, although authors acknowledged a potential disconnect between perceived and actual evidence strength. 21 Emerging evidence has since characterized both patient- and access-related influences on VA outcomes and underscores the need for individualization.46-48 Moving away from “fistula first” policy does not mean fistula avoidance, but rather supporting appropriate fistula use among eligible and interested individuals. 49 Although several of our patient and provider participants suggested that fistulas offer the best clinical outcomes and quality of life, they acknowledged that a blanket approach was inappropriate and could conflict with patients’ priorities.

Our study provides a strong rationale for the integration of shared decision-making in VA selection. Shared decision-making does not mean patients and their health care providers agree on all aspects of a medical decision, but rather that they reach a mutual understanding of patients’ priorities and implications of the decision. 50 However, there remains a paucity of primary research on how to “do” shared decision-making in VA practice. By examining complementary perspectives, our study presents pragmatic aspects of VA care that can be targeted by future interventions to enhance shared decision-making. For example, recognizing alignment on the need to optimize patient preparedness could justify development of decision support resources (eg, decision aids) to enhance knowledge, decisional readiness, and relationships between patients and their care team (Figure 1). Conversely, identifying how VA preferences and priorities diverge could prompt changes to how clinicians are trained in VA selection and create opportunities for VA exposure for patients. Bridging such gaps can help reduce decisional conflict, distill informational burden, and improve patient satisfaction with the outcome. 51 Our findings support standardized, iterative VA review processes with the kidney care team, leading up to and after hemodialysis initiation and irrespective of VA type.

Our study was strengthened by the inclusion of diverse perspectives on an issue with implications for practice and policy, yet we acknowledge some limitations. As participation was limited to English-speaking participants from urban, in-center hemodialysis units, it is possible that individuals from other regions or predialysis care programs may have expressed differing views. Furthermore, as few women, younger patients, and people from ethno-cultural minority groups participated, we could not explore or present findings attributable uniquely to these subgroups. We also had few caregiver participants, which we attribute to the lack of caregiver presence on site during hemodialysis sessions and reliance on nomination by patient participants. We recommend further dedicated study of VA selection perspectives in the populations underrepresented in our study or not captured by our inclusion criteria (eg, home hemodialysis). Our study also included many participants dialyzing via a catheter, whereas outside of Canada fistula use is much more common. 52 As arteriovenous graft use is low in Canada (<5%), we did not include individuals dialyzing via this access type. However, we did capture perspectives from several individuals who had changed VA type and with varying VA experiences, which provided depth to our findings. Last, participant perspectives reflect regional practices and policies, which may differ from hemodialysis programs internationally with different care models or where fistula use is tracked as a quality indicator and/or is financially incentivized. As expressed VA views and preferences relate both to long-held VA practices and to a more recent global shift toward VA individualization, findings are likely to be transferable to other similar contexts.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore opportunities to enhance the experience of VA selection for people receiving hemodialysis. Although many patients and caregivers lack readiness to engage in VA decisions, they wish to be informed of their options and involved in the deliberative process. Preference-focused discussions and pragmatic educational approaches that integrate the implications of VA for day-to-day living can promote confidence and satisfaction with the VA choice. The fact that many patients receiving hemodialysis described deferring the VA decision to their nephrologist suggests a high degree of trust in their physician’s judgment but also a burden of responsibility to ensure that the decisional outcome reflects patients’ priorities and values. Acknowledging how the diverse perspectives of patients, caregivers, and kidney care providers align and diverge is a critical first step toward innovative decision support resources, such as decision aids and “hands-on” educational opportunities, that bridge knowledge and readiness gaps.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581231215858 for Alignment Among Patient, Caregiver, and Health Care Provider Perspectives on Hemodialysis Vascular Access Decision-Making: A Qualitative Study by Angela R. Schneider, Pietro Ravani, Kathryn M. King-Shier, Robert R. Quinn, Jennifer M. MacRae, Shannan Love, Matthew J. Oliver, Swapnil Hiremath, Matthew T. James, Mia Ortiz, Braden R. Manns and Meghan J. Elliott in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Sarah Gil for her graphic design expertise in figure development and Ms Corri Robb for her transcription services.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study was approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB18-1727).

Consent for Publication: All authors contributed to critical revisions of the article and approved the final draft.

Availability of Data and Materials: This study used individual, participant-level data collected during interviews. We are unable to make our data set available due to restrictions on sharing potentially identifiable data as outlined in our Research Ethics Board certification. Inquiries related to this study’s data set can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions: A.R.S., M.J.E., K.M.K.-S., and P.R. contributed to research idea and study design. S.L. and M.O. contributed to participant recruitment and data collection. A.R.S. and M.J.E. contributed to data analysis and thematic generation. M.J.E. contributed to supervision or mentorship. All authors contributed to interpretation. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agrees to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: S.H. serves on the board of NephJC (www.nephjc.com), which is a 503c organization that supports social media in medical education and has multiple industry and academic supporters. S.H. receives no remuneration for this position. M.J.O. is sole owner of Oliver Medical Management Inc which is a private corporation that licenses the Dialysis Measurement Analysis and Reporting (DMAR) software system; has received honoraria from Baxter Healthcare; and is contracted Medical Lead at Ontario Renal Network, Ontario Health. R.R.Q. is co-inventor of the Dialysis Measurement Analysis and Reporting (DMAR) software system and has received honoraria from Baxter Healthcare. No other authors have disclosures.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research project grant (FRN162369) and Kidney Foundation of Canada Health Research grant (KFOC190009). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, or the decision to submit for publication.

ORCID iDs: Pietro Ravani  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6973-8570

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6973-8570

Swapnil Hiremath  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0010-3416

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0010-3416

Matthew T. James  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1876-3917

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1876-3917

Braden R. Manns  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8823-6127

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8823-6127

Meghan J. Elliott  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5434-2917

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5434-2917

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canadian Institute for Health Information. CORR final treatment modality for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on December 31: 2011 to 2020—Quick Stats 2021. https://www.cihi.ca/en/corr-final-treatment-modality-for-end-stage-renal-disease-esrd-patients-on-december-31-2011-to-2020. Accessed September 15, 2022.

- 4. Lok CE. Fistula first initiative: advantages and pitfalls. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(5):1043-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murea M, Geary RL, Davis RP, Moossavi S. Vascular access for hemodialysis: a perpetual challenge. Semin Dial. 2019;32(6):527-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vascular Access 2006 Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(suppl 1):S248-S273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quinn RR, Ravani P. Fistula-first and catheter-last: fading certainties and growing doubts. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(4):727-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ravani P, Palmer SC, Oliver MJ, et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):465-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grubbs V, Jaar BG, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Impact of pre-dialysis nephrology care engagement and decision-making on provider and patient action toward permanent vascular access. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murea M, Grey CR, Lok CE. Shared decision-making in hemodialysis vascular access practice. Kidney Int. 2021;100(4):799-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murea M, Woo K. New frontiers in vascular access practice: from standardized to patient-tailored care and shared decision making. Kidney360. 2021;2(8):1380-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Légaré F, Thompson-Leduc P. Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elliott MJ, Ravani P, Quinn RR, et al. Patient and clinician perspectives on shared decision making in vascular access selection: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81(1):48-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balamuthusamy S, Miller LE, Clynes D, Kahle E, Knight RA, Conway PT. American Association of Kidney Patients survey of patient preferences for hemodialysis vascular access. J Vasc Access. 2020;21(2):230-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woo K, Pieters H. The patient experience of hemodialysis vascular access decision-making. J Vasc Access. 2021;22(6):911-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casey JR, Hanson CS, Winkelmayer WC, et al. Patients’ perspectives on hemodialysis vascular access: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(6):937-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor MJ, Hanson CS, Casey JR, Craig JC, Harris D, Tong A. “You know your own fistula, it becomes a part of you”—patient perspectives on vascular access: a semistructured interview study. Hemodial Int. 2016;20(1):5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray MA, Thomas A, Wald R, Marticorena R, Donnelly S, Jeffs L. Are you SURE about your vascular access? exploring factors influencing vascular access decisions with chronic hemodialysis patients and their nurses. CANNT J. 2016;26(2):21-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Veer SN, Haller MC, Pittens CA, et al. Setting priorities for optimizing vascular access decision making—an international survey of patients and clinicians. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0128228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Veer SN, Ravani P, Coentrão L, et al. Barriers to adopting a fistula-first policy in Europe: an international survey among national experts. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(2):113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viecelli AK, Tong A, O’Lone E, et al. Report of the standardized outcomes in nephrology-hemodialysis (SONG-HD) consensus workshop on establishing a core outcome measure for hemodialysis vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(5):690-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(4)(suppl 2):S1-S164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson JL, Adkins D, Chauvin S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(1):7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2014;9:26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589-597. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nota I, Drossaert CH, Taal E, van de Laar MA. Arthritis patients’ motives for (not) wanting to be involved in medical decision-making and the factors that hinder or promote patient involvement. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(5):1225-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Politi MC, Dizon DS, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Stiggelbout AM. Importance of clarifying patients’ desired role in shared decision making to match their level of engagement with their preferences. BMJ. 2013;347:f7066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):531-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saeed F, Moss AH, Duberstein PR, Fiscella KA. Enabling patient choice: the “deciding not to decide” option for older adults facing dialysis decisions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(5):880-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ho YF, Chen YC, Li IC. A qualitative study on shared decision-making of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nurs Open. 2021;8(6):3430-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P. Shared decision-making in primary care: the neglected second half of the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(443):477-482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Greenwood S, Kingsmore D, Richarz S, et al. ‘It’s about what I’m able to do’: using the capabilities approach to understand the relationship between quality of life and vascular access in patients with end-stage kidney failure. SSM Qual Res Health. 2022;2:100187. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park J, Zuniga J. Effectiveness of using picture-based health education for people with low health literacy: an integrative review. Cogent Med. 2016;3(1):1264679. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferreira da Silva P, Talson MD, Finlay J, et al. Patient, caregiver, and provider perspectives on improving information delivery in hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:20543581211046078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xi W, Harwood L, Diamant MJ, et al. Patient attitudes towards the arteriovenous fistula: a qualitative study on vascular access decision making. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(10):3302-3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravani P, Quinn R, Oliver M, et al. Examining the association between hemodialysis access type and mortality: the role of access complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(6):955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dumaine CS, Brown RS, MacRae JM, Oliver MJ, Ravani P, Quinn RR. Central venous catheters for chronic hemodialysis: is “last choice” never the “right choice”? Semin Dial. 2018;31(1):3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grubbs V, Wasse H, Vittinghoff E, Grimes BA, Johansen KL. Health status as a potential mediator of the association between hemodialysis vascular access and mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(4):892-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allon M. Vascular access for hemodialysis patients: new data should guide decision making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(6):954-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kalloo S, Blake PG, Wish J. A patient-centered approach to hemodialysis vascular access in the era of fistula first. Semin Dial. 2016;29(2):148-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T. Deliberation before determination: the definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expect. 2010;13(2):139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shay LA, Lafata JE. Where is the evidence? a systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(1):114-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pisoni RL, Zepel L, Port FK, Robinson BM. Trends in US vascular access use, patient preferences, and related practices: an update from the US DOPPS practice monitor with international comparisons. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(6):905-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581231215858 for Alignment Among Patient, Caregiver, and Health Care Provider Perspectives on Hemodialysis Vascular Access Decision-Making: A Qualitative Study by Angela R. Schneider, Pietro Ravani, Kathryn M. King-Shier, Robert R. Quinn, Jennifer M. MacRae, Shannan Love, Matthew J. Oliver, Swapnil Hiremath, Matthew T. James, Mia Ortiz, Braden R. Manns and Meghan J. Elliott in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease