This cross-sectional study assesses the odds of discharge against medical advice from the emergency department by patient race and ethnicity in the US.

Key Points

Question

Do odds of emergency department (ED) discharge against medical advice (DAMA) vary by patient race and ethnicity?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 33 147 251 visits to 989 US hospitals, Black and Hispanic patients had greater odds of ED DAMA than their White counterparts. These findings persisted for Black patients but not Hispanic patients after adjusting for patient characteristics.

Meaning

The findings suggest that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to receive care in hospitals with higher overall DAMA rates, suggesting interventions should address medical segregation.

Abstract

Importance

Although discharges against medical advice (DAMA) are associated with greater morbidity and mortality, little is known about current racial and ethnic disparities in DAMA from the emergency department (ED) nationally.

Objective

To characterize current patterns of racial and ethnic disparities in rates of ED DAMA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample on all hospital ED visits made between January to December 2019 in the US.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was odds of ED DAMA for Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients nationally and in analysis adjusted for sociodemographic factors. Secondary analysis examined hospital-level variation in DAMA rates for Black, Hispanic, and White patients.

Results

The study sample included 33 147 251 visits to 989 hospitals, representing the estimated 143 million ED visits in 2019. The median age of patients was 40 years (IQR, 22-61 years). Overall, 1.6% of ED visits resulted in DAMA. DAMA rates were higher for Black patients (2.1%) compared with Hispanic (1.6%) and White (1.4%) patients, males (1.7%) compared with females (1.5%), those with no insurance (2.8%), those with lower income (<$27 999; 1.9%), and those aged 35 to 49 years (2.2%). DAMA visits were highest at metropolitan teaching hospitals (1.8%) and hospitals that served greater proportions of racial and ethnic minoritized patients (serving ≥57.9%; 2.1%). Odds of DAMA were greater for Black patients (odds ratio [OR], 1.45; 95% CI, 1.31-1.57) and Hispanic patients (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.04-1.29) compared with White patients. After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, income, and insurance status), the adjusted OR (AOR) for DAMA was lower for Black patients compared with the unadjusted OR (AOR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.09-1.28) and there was no difference in odds for Hispanic patients (AOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.15) compared with White patients. After additional adjustment for hospital random intercepts, DAMA disparities reversed, with Black and Hispanic patients having lower odds of DAMA compared with White patients (Black patients: AOR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.90-0.98]; Hispanic patients: AOR, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.63-0.72]). The intraclass correlation in this secondary analysis model was 0.118 (95% CI, 0.104-0.133).

Conclusions and Relevance

This national cross-sectional study found that Black and Hispanic patients had greater odds of ED DAMA than White patients in unadjusted analysis. Disparities were reversed after patient-level and hospital-level risk adjustment, and greater between-hospital than within-hospital variation in DAMA was observed, suggesting that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to receive care in hospitals with higher DAMA rates. Structural racism may contribute to ED DAMA disparities via unequal allocation of health care resources in hospitals that disproportionately treat racial and ethnic minoritized groups. Monitoring variation in DAMA by race and ethnicity and hospital suggests an opportunity to improve equitable access to health care.

Introduction

Discharges against medical advice (DAMA), defined as a patient’s decision to leave a medical encounter before health care practitioners recommend discharge,1 are associated with higher readmission rates, worse health outcomes, and significantly higher mortality compared with medically routine discharges.1,2 Thus, DAMA events represent avoidable morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.2,3,4,5 They also signify an erosion of therapeutic alliance between patients, medical teams, and health institutions, especially given recent emergency department (ED) crowding and hospital capacity crises.6,7,8,9,10

Previous literature from hospital inpatient settings has documented sociodemographic disparities in DAMA. Patients who are Black or Hispanic experience significantly higher DAMA rates compared with White patients.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Although race-related DAMA disparities have been documented, it has been difficult to elucidate the specific mechanisms.

Patient factors such as young age, male sex, absence of insurance, low income, and substance use disorder are known to be associated with DAMA rates.3,11,14,15,16,18,19 Studies that adjust for patient-level factors like age, gender, and psychiatric comorbidities have observed mixed results; such adjustment for these factors has been found to increase, reduce, or have no effect on analytic findings on racial DAMA disparities depending on the study.11,16,20 Moreover, beyond patient-level factors, previous literature has shown that hospital-level factors contribute to variation in DAMA rates.3,11,16,20 A study of a limited number of hospitals within 3 states found that DAMA rates vary widely across hospitals.11

Recent studies have focused on DAMA in the inpatient setting,11,16,20 precluding analysis in the ED setting, where there are implications in access to hospital-based care and where patients are clinically undifferentiated and experience a more explicit waiting time. Few studies have examined national patterns in DAMA from the ED across all conditions, which serves as the most common gateway to inpatient hospitalization and may better include racial and ethnic minoritized patients who disproportionately rely on the ED for health care access.21,22

To our knowledge, this is the first national and comprehensive study to examine racial inequities in DAMA rates among ED patients across conditions. Accordingly, we investigated disparities in ED DAMA among racial and ethnic minoritized patients in unadjusted analysis and then accounting for both sociodemographic-level and hospital-level factors. As a secondary aim, we examined hospital-level variation in DAMA rates among Black, Hispanic, and White patients. We specifically sought to compare interhospital and intrahospital variation in DAMA disparities. We studied the period just before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using the 2019 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), which is the largest all-payer ED database in the US. This study was approved by the Yale University Human Research and Protection Program and complied with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Informed consent was not obtained as the study used retrospective, deidentified data.

Study Population

In our primary analysis, we included all hospital ED visits made from January to December 2019. The NEDS variable used to define our outcome was disposition from the ED. NEDS includes the following categories within this variable: routine (category 1); transfer to short-term hospital (category 2); other transfers, including skilled nursing facility, intermediate care, and another type of facility (category 5); home health care (category 6); against medical advice (category 7); admitted as an inpatient to this hospital (category 9); died in ED (category 20); discharged or transferred to court or law enforcement (category 21); not admitted, destination unknown (category 98); and discharged alive, destination unknown (but not admitted) (category 99). We excluded visits resulting in death in the ED. Given that we were interested in ED visits that resulted in DAMA discharge, we focused on ED visits that resulted in DAMA (category 7), inpatient admission (including category 9), routine discharge from the ED (including categories 1 and 6), transfer (including categories 2 and 5), and other or unknown disposition (including categories 21, 98, and 99). In our secondary analysis, hospitals with a DAMA visit count of less than 5 in each race category were excluded. eTable 1 in Supplement 1 describes the hospitals in that more limited sample compared with all hospitals in the unweighted NEDS.

Our primary variable was patient race and ethnicity, defined in NEDS as Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Native American, White, or other (not explicitly defined within NEDS). The method for collecting race and ethnicity data in NEDS is not specified and likely varies across states.23 Additional patient-level variables of interest included sex (male, female, and other, which was a data term capturing nonspecific sex labels including missing, invalid, inconsistent, nonmale, and nonfemale), age, income (represented by zip code–derived median household income by quartile), primary payer insurance status (self-pay [uninsured], no charge, Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance), and principal visit diagnosis based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision code and categorized into the 50 most common clinically meaningful conditions using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR).24 Hospital-level variables included hospital census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West), hospital ownership status (government or nonfederal [public], private or not for profit [voluntary], or private or investor owned [proprietary]), teaching status (metropolitan nonteaching, metropolitan teaching, or nonmetropolitan hospital), urban-rural designation (large metropolitan, small metropolitan, micropolitan, not metropolitan or micropolitan, or other), ED annual visit volume, and proportion of racial and ethnic minoritized patients served (by quartile).

Statistical Analysis

In our primary analysis, the unadjusted odds of DAMA for Black and Hispanic patients (compared with the White reference group) were reported from a logistic regression model with robust SEs for clustering at the hospital level (model 1). We then reported adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of DAMA based on race and ethnicity category in a model including patient age, sex, insurance status, and income (model 2). We report descriptive results (counts and percentages) for Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and other racial and ethnic groups, but these groups were excluded in all statistical analyses and models due to small sample sizes.

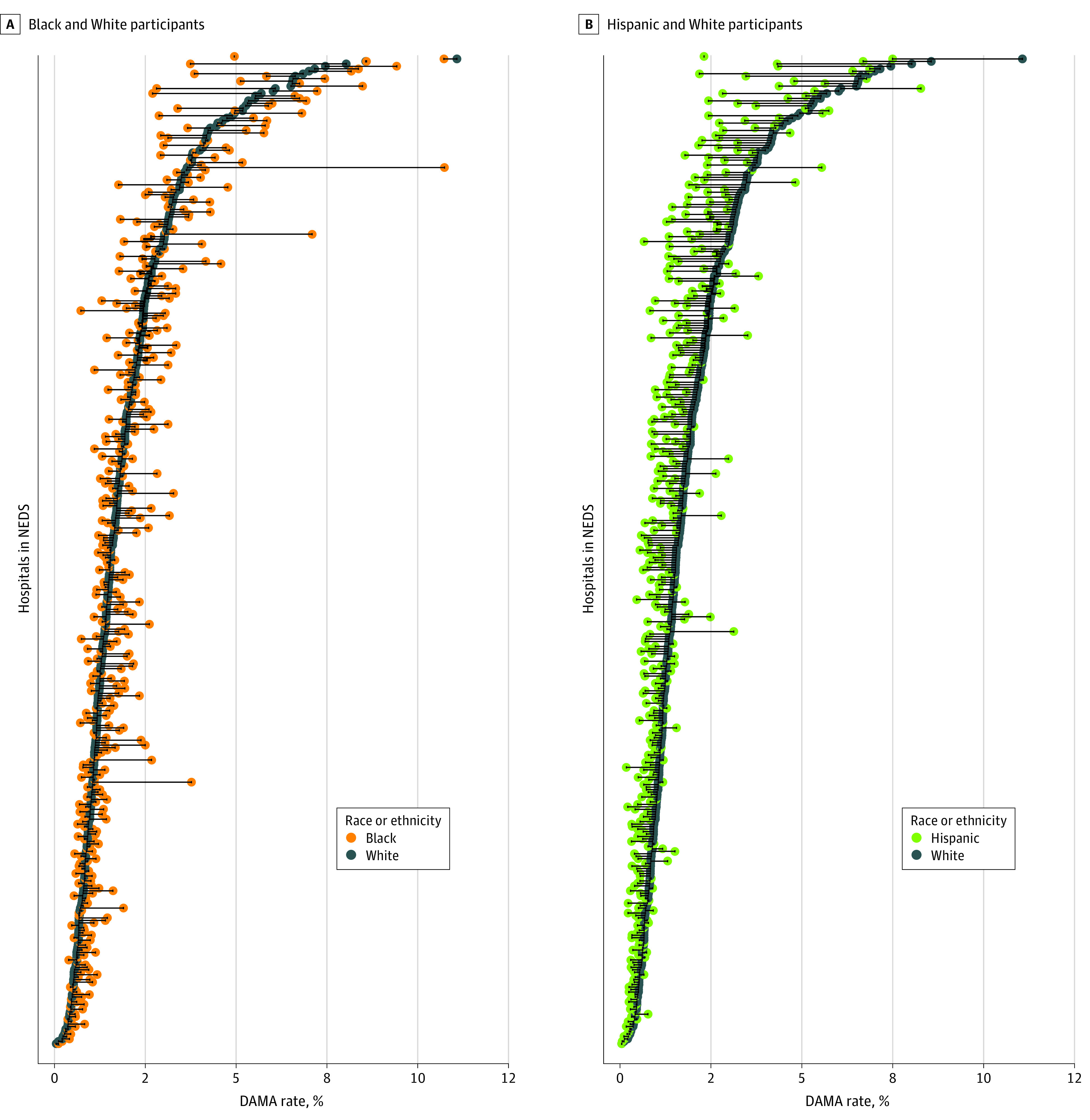

We conducted a secondary analysis to examine the association of hospital-level factors with patient DAMA in 3 ways. We first used a hierarchical linear regression model with random effects to control for sociodemographic covariates and hospital random intercepts (model 3) to estimate the odds of DAMA. Second, we also assessed the amount of variation in DAMA that could be explained at the hospital level. This was done by reporting the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which in this case was calculated as the ratio of the between-hospital variance to the total variance. The ICC indicates the proportion of variation in DAMA rates that was explained between hospitals rather than within hospitals.25 Lastly, we plotted within-hospital DAMA rates by race and ethnicity, sorted by the overall hospital DAMA rate, to visualize variation across and within hospitals.

Data analyses were carried out from August 2022 to February 2023. Missing data elements are reported in summary tables. Statistical models exclude visits with missing data elements (4.1% of overall records). Summary statistics are reported using weighted nationally representative counts and proportions. Statistical modeling was performed on the unweighted data. Analyses were done in R, version 4.1.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) and Stata, version 17 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

After excluding 46 326 ED visits resulting in death in the ED, the final sample included 33 147 251 unweighted ED visits across 989 hospitals, representing 143 432 284 weighted ED visits nationwide. Weighted to be nationally representative, visits were predominately made by White patients (55.0%) followed by Black (20.7%), Hispanic (15.4%), Asian or Pacific Islander (2.1%), and Native American (0.5%) patients; 3.6% of visits were made by patients with other race and ethnicity. More visits were also made by those with Medicaid (30.4%), female patients (55.0%) compared with male patients (45.0%), and patients from the lowest-income zip codes (median household income <$47 999; 34.4%). The median age of patients was 40 years (IQR, 22-61 years). Among these ED visits, 2 294 532 (1.6%) resulted in DAMA. DAMA visits were highest for Black (2.1%) and Hispanic (1.6%) patients followed by Native American (1.7%); White (1.4%), and Asian or Pacific Islander (1.1%) patients; 1.9% of patients with other race and ethnicity had DAMA visits (Table 1).

Table 1. Total ED Visits and Visits for DAMA by Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | ED visits, nationally weighted No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 143 432 284) | Resulting in DAMA (n = 2 294 532) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3 050 921 (2.1) | 33 943 (1.1) |

| Black | 29 592 795 (20.7) | 615 048 (2.1) |

| Hispanic | 22 101 883 (15.4) | 362 604 (1.6) |

| Native American | 784 668 (0.5) | 13 307 (1.7) |

| White | 78 715 399 (55.0) | 1 123 868 (1.4) |

| Othera | 5 087 458 (3.6) | 94 893 (1.9) |

| Missing | 3 898 465 (2.7) | 50 860 (1.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 78 803 475 (55.0) | 1 173 342 (1.5) |

| Male | 64 417 142 (45.0) | 1 120 756 (1.7) |

| Other or missing | 10 971 (<0.1) | 425 (3.9) |

| Age, y | ||

| <18 | 26 066 588 (18.2) | 174 390 (0.7) |

| 18-34 | 34 857 729 (24.3) | 737 304 (2.1) |

| 35-49 | 25 973 070 (18.1) | 585 501 (2.2) |

| 50-64 | 26 028 634 (18.2) | 514 122 (2.0) |

| 65-79 | 19 585 123 (13.7) | 215 070 (1.1) |

| ≥80 | 10 720 443 (7.5) | 68 135 (0.6) |

| Income, $b | ||

| <47 999 | 49 305 775 (34.4) | 945 392 (1.9) |

| 48 000-60 999 | 36 780 172 (25.7) | 549 129 (1.5) |

| 61 000-81 999 | 31 066 928 (21.7) | 427 634 (1.4) |

| ≥82 000 | 23 664 046 (16.5) | 300 863 (1.3) |

| Missing | 2 414 666 (1.7) | 71 506 (3.0) |

| Primary payer | ||

| Medicare | 35 391 643 (24.7) | 431 715 (1.2) |

| Medicaid | 43 528 464 (30.4) | 826 738 (1.9) |

| Private insurance | 40 317 314 (28.1) | 443 152 (1.1) |

| Self-pay | 17 597 365 (12.3) | 498 204 (2.8) |

| No charge | 677 667 (0.5) | 19 009 (2.8) |

| Missing | 5 719 135 (4.0) | 75 705 (1.3) |

Abbreviations: DAMA, discharges against medical advice; ED, emergency department.

Other race is not explicitly defined in the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

Based on zip code–derived median household income.

Weighted nationally, men had higher DAMA rates compared with women (1.7% vs 1.5%), although both had lower DAMA rates than those with other or missing sex (3.9%). Younger patients had generally higher DAMA rates, although lower rates of DAMA were observed in the youngest and oldest age ranges: younger than 18 years (0.7%), 18 to 34 years (2.1%), 35 to 49 years (2.2%), 50 to 64 years (2.0%), 65 to 79 years (1.1%), and 80 years or older (0.6%). The DAMA rate was highest for patients residing in zip codes with the lowest median income: $1 to $47 999 (1.9%), $48 000 to $60 999 (1.5%), $61 000 to $81 999 (1.4%), and more than $82 000 (1.3%). Uninsured patients had an overall DAMA rate more than double that of privately insured individuals: self-pay (2.8%), Medicare (1.2%), Medicaid (1.9%), private (1.1%), and no charge (2.8%).

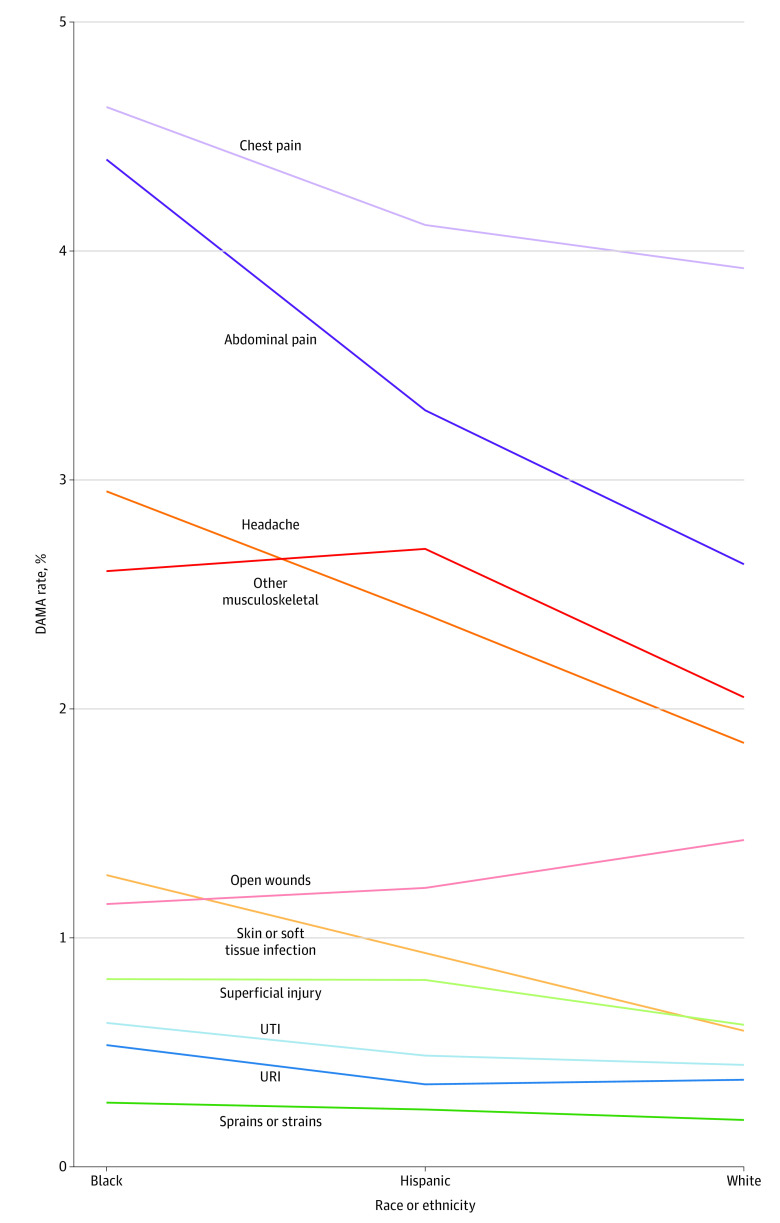

Among the 50 most common CCSR codes in NEDS, weighted national DAMA rates were highest for abdominal pain, nonspecific chest pain, syncope, headache, and alcohol-related disorders (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Seven CCSR codes, representing 5.1% (7.3 million) of all ED visits, were associated with DAMA rates of 4% or greater (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Conditions included miscellaneous mental and behavioral disorders or conditions, opioid-related disorders, nonspecific chest pain, and poisoning by drugs, initial encounter. Among the 10 most common ED diagnosis groups, which represented 43 million weighted ED visits (30.5%) within our sample, the median DAMA rate was 1.7% (range, 0.2%-4.1%). DAMA rates for Black and Hispanic patients were higher than those for White patients for 9 of the 10 conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differences in Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rates by Race and Ethnicity for the 10 Most Common Emergency Department Conditions.

URI indicates upper respiratory tract infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Across all hospitals in NEDS, the mean pooled hospital DAMA rate was 1.3%, ranging from 0.3% at the 10th percentile to 2.6% at the 90th percentile. Hospitals in the South had the highest regional DAMA rate at 1.8% followed by the West (1.7%), Northeast (1.6%), and Midwest (1.2%). Public hospitals had higher DAMA rates than private hospitals (2.1% vs 1.2%). Large metropolitan hospitals had the highest DAMA rate (1.8%) compared with hospitals with other urban-rural designations. Among hospitals in metropolitan settings, teaching hospitals had higher DAMA rates (1.8%) than nonteaching hospitals (1.4%). We also found higher DAMA rates as ED visit volume increased by 20 000 annual visit volume increments. Lastly, we found increasing DAMA rates in hospitals that served greater proportions of racial and ethnic minoritized patients, with the quartile of hospitals treating the greatest disproportion of these patients (serving ≥57.9%) having a DAMA rate of 2.1% (0%-12.1% served: 1.1%; >12.1% to 28.9% served: 1.2%; >28.9% to 57.9% served: 1.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Total ED Visits and Visits for DAMA by Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | ED visits, nationally weighted No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 143 231 588) | Resulting in DAMA (n = 2 294 523) | |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 25 912 644 (18.1) | 403 441 (1.6) |

| Midwest | 32 104 424 (22.4) | 370 036 (1.2) |

| South | 58 272 441 (40.7) | 1 063 104 (1.8) |

| West | 26 942 079 (18.8) | 457 942 (1.7) |

| Hospital control status | ||

| Government or private (collapsed category) | 18 672 735 (13.0) | 278 977 (1.5) |

| Government, nonfederal (public) | 17 743 977 (12.4) | 377 341 (2.1) |

| Private, not-for-profit (voluntary) | 75 813 188 (52.9) | 1 197 671 (1.6) |

| Private, investor-owned (proprietary) | 16 763 212 (11.7) | 277 363 (1.6) |

| Private (collapsed category) | 14 238 476 (9.9) | 163 171 (1.2) |

| Teaching status | ||

| Metropolitan nonteaching | 29 615 068 (20.7) | 424 670 (1.4) |

| Metropolitan teaching | 91 600 509 (64.0) | 1 628 520 (1.8) |

| Nonmetropolitan hospital | 22 016 011 (15.4) | 241 333 (1.1) |

| Urban-rural designation | ||

| Large metropolitan | 73 097 776 (51.0) | 1 301 843 (1.8) |

| Small metropolitan | 45 678 792 (31.9) | 715 446 (1.6) |

| Micropolitan | 13 483 688 (9.4) | 144 101 (1.1) |

| Not metropolitan or micropolitan | 7 020 848 (4.9) | 80 038 (1.1) |

| Collapsed categories or other | 3 950 484 (2.8) | 53 096 (1.3) |

| ED visit volume | ||

| <20 000 | 17 143 498 (12.0) | 191 709 (1.1) |

| 20 000-39 999 | 27 453 156 (19.2) | 382 856 (1.4) |

| 40 000-59 999 | 32 180 578 (22.5) | 470 047 (1.5) |

| 60 000-79 999 | 24 477 348 (17.1) | 404 883 (1.6) |

| 80 000-99 999 | 16 495 019 (11.5) | 279 403 (1.7) |

| ≥100 000 | 25 481 987 (17.8) | 565 625 (2.2) |

| Racial and ethnic minority community served, % | ||

| 0-12.1 | 18 201 963 (12.7) | 193 292 (1.1) |

| >12.1 to 28.9 | 30 592 830 (21.3) | 358 124 (1.2) |

| >28.9 to 57.9 | 45 708 030 (31.9) | 702 253 (1.5) |

| >57.9 | 48 929 461 (34.1) | 1 040 854 (2.1) |

Abbreviations: DAMA, discharges against medical advice; ED, emergency department.

Adjusted Modeling of the Association Between Race and Ethnicity and DAMA

In our unweighted, unadjusted model (model 1), we found that odds of DAMA were greater for Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients (Black: OR, 1.45 [95% CI, 1.31-1.57]; Hispanic: OR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.04-1.29]). There was no difference in odds between the other race and ethnicity group and White patients (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.89-1.36) (Table 3). After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, income, and insurance status [model 2]), the AOR for DAMA compared with White patients decreased to 1.18 (95% CI, 1.09-1.28) for Black patients and there was no difference for Hispanic patients (AOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.15) (Table 3).

Table 3. Odds Ratios for DAMA by Race and Ethnicity Categorya.

| Race and ethnicity | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All hospitals in 2019 NEDS | Hospitals with ≥5 DAMAs per race and ethnicity category | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3b | |

| Black | 1.45 (1.31-1.57) | 1.18 (1.09-1.28) | 1.36 (1.23-1.48) | 1.08 (0.99-1.18) | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) |

| Hispanic | 1.16 (1.04-1.29) | 1.03 (0.92-1.15) | 1.02 (0.92-1.15) | 0.89 (0.79-0.99) | 0.68 (0.63-0.72) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 1.10 (0.89-1.36) | 1.11 (0.96-1.28) | 1.20 (1.04-1.39) | 1.13 (1.00-1.28) | 0.96 (0.90-1.03) |

Abbreviations: DAMA, discharges against medical advice; NEDS, Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

Data are for 33 147 251 visits at 989 hospitals in the 2019 NEDS and 23 534 064 visits and 401 hospitals with 5 or more DAMAs per race and ethnicity category. Model 1 was the unadjusted model; model 2 was adjusted for sex, income, age, and insurance; and model 3 was adjusted for sex, income, age, insurance, and a hospital random intercept.

The model 3 intraclass correlation was 0.118 (95% CI, 0.104-0.133).

In our secondary analysis, 401 hospitals with at least 5 DAMA events in each race and ethnicity category were included (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). After adjusting for sociodemographic factors and hospital random intercepts (model 3), the odds of DAMA were lower for Black patients compared with White patients (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.90-0.98) and lower for Hispanic patients compared with White patients (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.63-0.72) (Table 3). The ICC in this secondary analysis model was 0.118 (95% CI, 0.104-0.133), indicating that 11.8% of the overall variance in DAMA rates was explained at the hospital level. Figure 2 plots DAMA rates of Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients by hospital and demonstrates that within-hospital DAMA disparities were attenuated as in model 3. Median hospital-level DAMA rate for Black patients was 1.7% (IQR, 1.0%-2.7%) compared with 1.2% (IQR 0.7%-1.9%) for Hispanic patients and 1.6% (IQR, 1.0%-2.5%) for White patients.

Figure 2. Distribution of Estimated Within-Hospital Emergency Department Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rates by Race and Ethnicity Category.

NEDS indicates Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

Discussion

In this contemporary, national cross-sectional study of ED DAMA rates, we found that 1.6% of ED visits resulted in DAMA. DAMA rates were highest for patients from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups, including Black and Hispanic people, those with lower income, and those without insurance. For example, DAMA rates for uninsured patients were 2.8% compared with a DAMA rate of 1.1% for privately insured individuals. Hospitals serving the highest proportion of racial and ethnic minoritized patients by quartile had DAMA rates of 2.1% compared with 1.1% DAMA in hospitals serving the lowest proportion of this group. Hospitals with over 100 000 ED visits had higher DAMA rates than hospitals with less than 20 000 ED visits.

Overall, we found that the mean DAMA rates among ED patients was similar to that in inpatient settings.16 DAMA rates were particularly high for high-risk diagnoses related to opioid use, syncope, coma or brain damage, and chest pain, which represent conditions for which patients are at risk of poor outcomes without complete treatment. A 2021 study26 demonstrated that among patients with an opioid overdose–related visit, the mortality hazard was 7 times higher for patients with DAMA. Additionally, given that patients who experience DAMA receive fewer medical interventions, including cardiac procedures and coronary revascularization,11,16 implications of DAMA for chest pain may include missed detection of myocardial infarction and higher morbidity and mortality.

In our unadjusted models, we found higher odds of DAMA among Black and Hispanic patients compared with White patients, even for high-risk conditions like chest pain, headache, heart failure, and syncope. Based on the unadjusted differences in rate in Table 1, we estimate that if Black patients had DAMA rates similar to those of White patients, there would be 191 871 fewer DAMAs in the Black patient population per year. These findings, however, were reversed, attenuated, or rendered insignificant after adjusting for other patient-level sociodemographic factors and for each hospital’s baseline DAMA rate, demonstrating that within-hospital effects were likely primarily driven by hospital factors. This finding further suggests that variations in DAMA rates and racial and ethnic DAMA disparities may be more substantial between hospitals than within hospitals.

That much of the variation in racial and ethnic DAMA disparities was associated with the location where patients received treatment (the hospital random effect) also suggests that higher DAMA rates among Black and Hispanic patients are associated with the context in which they seek care rather than their individual characteristics. It is notable that hospitals serving a larger proportion of racial and ethnic minoritized patients experienced higher DAMA rates (Table 2). This descriptive data, paired with our modeling analysis, suggests that Black and Hispanic patients are more likely to receive care in hospitals with higher overall DAMA rates. For example, by extrapolating from model 3 (Table 3), we estimate that at a population level, if ED care of Black patients was distributed evenly across hospitals in the US rather than more concentrated in a small number of hospitals with high DAMA rates, there would be 217 544 fewer DAMAs in the Black patient population per year. Taken together, our analyses show how health disparities are not merely a result of independent biologic or behavioral risk factors at the patient level.

Several hypotheses may explain structural origins of race and ethnicity–related DAMA disparities, including manifestations of institutional racism, such as government-sponsored segregation, urban design, care fragmentation, and structural disinvestment, that funnel racial and ethnic minoritized patients to different hospitals that are disadvantaged, deprived, and lower performing directly because of unequal resource allocation.27,28,29,30 Previous literature has suggested that higher inpatient DAMA rates are found within hospitals caring for higher proportions of patients from racial and ethnic minoritized groups, noting this may be related to resource constraints involving nursing shortages, insufficient budgets, and inadequate technical support that compound high ED visit volumes.11,16,20,31,32 Thus, our findings join a growing body of literature demonstrating how racial and ethnic health inequities are significantly associated with the setting where racial and ethnic minoritized patients are more likely to receive care.31,33,34,35,36,37,38 That health outcomes are worse in hospitals that care for a disproportionate number of racial and ethnic minoritized patients is inconsistent with the premise of the “separate but equal” doctrine and may represent breach of health justice and civil rights.28,39

Relatedly, previous discussions about DAMA have generally characterized an association of DAMA with breakdowns in the communication or therapeutic alliance between patient and health care practitioner,1,20,40 such as disagreement with physician judgement, interpersonal conflict, prior negative health care experiences, dissatisfaction with care quality, or cultural factors.11,16 While important to consider that patients from racial and ethnic minoritized groups may experience disrespect (rather than perceive disrespect), trauma, and unfair treatment at higher rates in the health care system, analysis on DAMA and other health disparities should expand to consider realities of institutional inequity. Given extensive economic, educational, geographic, and criminal justice disparities across racial and ethnic groups, minoritized patients may face heightened financial hardships, transportation difficulties, caregiving responsibilities, or occupational limitations that translate to greater odds of DAMA. Furthermore, racial and ethnic minoritized patients might be more likely to be labeled as having DAMA compared with their White counterparts, which is important given that notation of previous DAMA can arouse prejudice, stigma, and even worsen quality of and access to care. In one study,41 patient history of DAMA was seen by clinicians as a red flag for drug seeking on par with tampering with analgesia devices.

Policy makers, particularly those at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, have called for more hospital quality and accountability measures to improve equity. Because of known and significant consequences of DAMA2,3,4,5,17,18 and because analyses have demonstrated that intrahospital racial disparities in DAMA rates were particularly wide in hospitals with high overall DAMA rates,3,11,16 the measurement and reporting of DAMA may serve as a feasible and high-impact target for equity and access-focused quality improvement initiatives. To maximize the potential benefits of monitoring DAMA as a distal measure of health care disparities, such advances should be mindful of the context of institutional inequity. For example, given the likely relationship between hospital resources and DAMA, such quality measures would not be well suited to the pay-for-performance context, as implementing such measures without recognizing the underlying imbalance of wealth concentration might simply reward well-resourced hospitals and possibly risk further structural disinvestment.

Quality improvement efforts to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in DAMA rates should focus on interventions that target medical segregation and equitable distribution of resources. To address structural factors associated with increased likelihood of DAMA, policy interventions are needed at both the health system and public health scale, including hospital administrative interventions to address hospital capacity and boarding crises and federal and state policies to facilitate care coordination, insurance coverage, and other social services that may address barriers in hospital admission and allow for safe discharge plans home, particularly in neighborhoods with poor health outcomes.6

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the way in which race and ethnicity data were captured within NEDS is not clearly defined and likely varied; thus, we cannot appraise the quality of race and ethnicity data. Additionally, although we observed DAMA rates of 1.1% and 1.7% for Asian or Pacific Islander and Native American patients, respectively, we could not model odds of DAMA in these groups due to small sample sizes. Furthermore, criteria for designating visit dispositions as DAMA were unavailable in NEDS and likely varied across systems and health care practitioners. There may also be bias in which patient populations are labeled as DAMA. Although we attempted to control for covariates known to be associated with DAMA rates, due to administrative data limitations, we could not control for all relevant factors associated with DAMA, including degree of clinical severity, ED wait times, and practitioner-level factors.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study of national ED DAMA rates found enduring and significant DAMA disparities for Black and Hispanic patients. Black and Hispanic patients had greater odds of ED DAMA than White patients in unadjusted analysis. Disparities were reversed after patient-level and hospital-level risk adjustment, suggesting that place of hospitalization is a more significant factor associated with DAMA than individual patient characteristics, such as race, age, sex, income, and insurance. Among several contextual factors, structural racism likely contributes to ED DAMA disparities by perpetuating conditions that cause unequal investment of health care resources in hospitals that disproportionately care for racial and ethnic minoritized patients. Measuring and addressing hospital-level variations in DAMA rates and disparities is an opportunity to improve equitable access to hospital care.

eTable 1. Sample Hospital Characteristics (Primary Analysis and Secondary Analysis)

eTable 2. Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rates By Race and Ethnicity for Fifty Most Common Emergency Department (ED) Conditions

eTable 3. Emergency Department (ED) Conditions With Average Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rate >4%

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255-260. doi: 10.4065/84.3.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594-602. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-929. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1371-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger JT. Discharge against medical advice: ethical considerations and professional obligations. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):403-408. doi: 10.1002/jhm.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albayati A, Douedi S, Alshami A, et al. Why do patients leave against medical advice? reasons, consequences, prevention, and interventions. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(2):111. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stepanikova I. Racial-ethnic biases, time pressure, and medical decisions. J Health Soc Behav. 2012;53(3):329-343. doi: 10.1177/0022146512445807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wigboldus DH, Sherman JW, Franzese HL, van Knippenberg A. Capacity and comprehension: spontaneous stereotyping under cognitive load. Soc Cogn. 2004;22(3):292-309. doi: 10.1521/soco.22.3.292.35967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelen GD, Wolfe R, D’Onofrio G, et al. Emergency department crowding: the canary in the health care system. NEJM Catal. Published online September 28, 2021. doi: 10.1056/CAT.21.0217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janke AT, Melnick ER, Venkatesh AK. Hospital occupancy and emergency department boarding during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233964. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Discharges against medical advice: are race/ethnicity predictors? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):955-960. doi: 10.1007/BF02743144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalrymple AJ, Fata M. Cross-validating factors associated with discharges against medical advice. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38(4):285-289. doi: 10.1177/070674379303800411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DB, Telles JL. Discharges against medical advice at regional acute care hospitals. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(2):212-215. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.2.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy E, Bartman BA. Race and hospital discharge against medical advice. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88(10):658-660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325-327. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2002.tb11268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204-2208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baptist AP, Warrier I, Arora R, Ager J, Massanari RM. Hospitalized patients with asthma who leave against medical advice: characteristics, reasons, and outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):924-929. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiscella K, Meldrum S, Barnett S. Hospital discharge against advice after myocardial infarction: deaths and readmissions. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1047-1053. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anis AH, Sun H, Guh DP, Palepu A, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV. Leaving hospital against medical advice among HIV-positive patients. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):633-637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. Discharge against medical advice in the United States, 2002-2011. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(4):525-535. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services . Trends in the utilization of emergency department services, 2009-2018. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/trends-utilization-emergency-department-services-2009-2018

- 22.Venkatesh AK, Chou SC, Li SX, et al. Association between insurance status and access to hospital care in emergency department disposition. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):686-693. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(HCUP) HCaUP . HCUP NEDS Description of Data Elements. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(HCUP) HCaUP . Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feaster D, Brincks A, Robbins M, Szapocznik J. Multilevel models to identify contextual effects on individual group member outcomes: a family example. Fam Process. 2011;50(2):167-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01353.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moe J, Chong M, Zhao B, Scheuermeyer FX, Purssell R, Slaunwhite A. Death after emergency department visits for opioid overdose in British Columbia: a retrospective cohort analysis. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(1):E242-E251. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tikkanen RS, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, et al. Hospital payer and racial/ethnic mix at private academic medical centers in Boston and New York City. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(3):460-476. doi: 10.1177/0020731416689549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarrazin MS, Campbell ME, Richardson KK, Rosenthal GE. Racial segregation and disparities in health care delivery: conceptual model and empirical assessment. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1424-1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00977.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burlage RK. From campus to corporation: New York City medical empires, 1960-1985. Urban planning, regional policy, and the structure of health care institutions. Cornell University; 1994. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/docview/304122574?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- 31.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the Hospital Quality Alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1233-1239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himmelstein G, Ceasar JN, Himmelstein KE. Hospitals that serve many black patients have lower revenues and profits: structural racism in hospital financing. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(3):586-591. doi: 10.1007/s11606-022-07562-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005;43(4):308-319. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hausmann LR, Ibrahim SA, Mehrotra A, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pneumonia treatment and mortality. Med Care. 2009;47(9):1009-1017. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a80fdc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1177-1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):e407-e415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skinner J, Chandra A, Staiger D, Lee J, McClellan M. Mortality after acute myocardial infarction in hospitals that disproportionately treat black patients. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2634-2641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asch DA, Islam MN, Sheils NE, et al. Patient and hospital factors associated with differences in mortality rates among Black and White US Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112842. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calman N, Ruddock C, Golub M, Le L. Separate and Unequal: Medical Apartheid in New York City. Institute for Urban Family Health. 2005. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.latinoshe.org/pdf/MedicalApartheidNYC.pdf

- 40.Windish DM, Ratanawongsa N. Providers’ perceptions of relationships and professional roles when caring for patients who leave the hospital against medical advice. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1698-1707. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0728-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haywood C Jr, Lanzkron S, Hughes MT, et al. A video-intervention to improve clinician attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease: the results of a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):518-523. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1605-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Sample Hospital Characteristics (Primary Analysis and Secondary Analysis)

eTable 2. Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rates By Race and Ethnicity for Fifty Most Common Emergency Department (ED) Conditions

eTable 3. Emergency Department (ED) Conditions With Average Discharges Against Medical Advice (DAMA) Rate >4%

Data Sharing Statement