Abstract

Background

Email is one of the most widely used methods of communication, but its use in healthcare is still uncommon. Where email communication has been utilised in health care, its purposes have included clinical communication between healthcare professionals, but the effects of using email in this way are not well known. We updated a 2012 review of the use of email for two‐way clinical communication between healthcare professionals.

Objectives

To assess the effects of email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals on healthcare professional outcomes, patient outcomes, health service performance, and service efficiency and acceptability, when compared to other forms of communicating clinical information.

Search methods

We searched: the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 9 2013), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to August 2013), EMBASE (OvidSP) (1974 to August 2013), PsycINFO (1967 to August 2013), CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (1982 to August 2013), and ERIC (CSA) (1965 to January 2010). We searched grey literature: theses/dissertation repositories, trials registers and Google Scholar (searched November 2013). We used additional search methods: examining reference lists and contacting authors.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, quasi‐randomised trials, controlled before and after studies, and interrupted time series studies examining interventions in which healthcare professionals used email for communicating clinical information in the form of: 1) unsecured email, 2) secure email, or 3) web messaging. All healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers in all settings were considered.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, assessed the included studies' risk of bias, and extracted data. We contacted study authors for additional information and have reported all measures as per the study report.

Main results

The previous version of this review included one randomised controlled trial involving 327 patients and 159 healthcare providers at baseline. It compared an email to physicians containing patient‐specific osteoporosis risk information and guidelines for evaluation and treatment versus usual care (no email). This study was at high risk of bias for the allocation concealment and blinding domains. The email reminder changed health professional actions significantly, with professionals more likely to provide guideline‐recommended osteoporosis treatment (bone density measurement or osteoporosis medication, or both) when compared with usual care. The evidence for its impact on patient behaviours or actions was inconclusive. One measure found that the electronic medical reminder message impacted patient behaviour positively (patients had a higher calcium intake), and two found no difference between the two groups. The study did not assess health service outcomes or harms.

No new studies were identified for this update.

Authors' conclusions

Only one study was identified for inclusion, providing insufficient evidence for guiding clinical practice in regard to the use of email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals. Future research should aim to utilise high‐quality study designs that use the most recent developments in information technology, with consideration of the complexity of email as an intervention.

Keywords: Humans, Electronic Mail, Health Personnel, Interprofessional Relations, Reminder Systems, Osteoporosis, Osteoporosis/diagnosis, Osteoporosis/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Using email for healthcare professionals to contact each other

Email is now a popular method of communication but it is not so commonly used in health care. We wanted to discover how the use of email by healthcare professionals to communicate with each other might affect patients, healthcare professionals and health services. We were also interested in how it might fit into health systems.

In this review, we found only one study that focused on the effects of healthcare professionals using email to communicate with each other. This study included 327 patients and 159 healthcare providers, and compared an email reminder for physicians with usual care. It found that healthcare professionals who received an email reminder were more likely to provide guideline‐recommended osteoporosis treatment than those who did not, and this may or may not have improved patient care. We were unable to properly assess its impact on patient behaviours or actions as the results were mixed. The study did not measure how email affects health services, or whether email can cause harms. This evidence is current to August 2013.

As there is a lack of evidence for the effects of healthcare professionals using email to communicate with each other, high‐quality research is needed to evaluate the use of email for this purpose. Future research should look at the costs of using email and take into account ongoing changes in technology.

Background

Related systematic reviews

This review forms part of a suite of reviews, incorporating two other reviews:

email for the provision of information on disease prevention and health promotion (Sawmynaden 2012);

email for clinical communication between patients or caregivers and healthcare professionals (Atherton 2012).

The use of email

The use of email as a medium for business and social communication is increasingly common (Pew 2005). This is consistent with the global expansion of users on the Internet, with 90% of Internet users said to use email (Pew 2005; IWS 2007). While industries such as insurance and banking have readily embraced such new technology in order to compete on the global stage (CBI 2006), the healthcare sector has been more cautious in accepting it (Neville 2004). The vast majority of literature on the use of email originates in North America and it is uncertain whether the results of such research will be applicable to other international healthcare environments, where email availability and technology can be very different.

Email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals

Healthcare professionals have been communicating via email since the early 1990s, for varying purposes such as consulting with colleagues and scheduling meetings (Moyer 1999). Communication between healthcare professionals can occur on several different levels, from one‐on‐one communication to that between members of a multidisciplinary team, and official communication such as that between healthcare professionals and organisations. A survey of over 4000 US physicians reported that nearly two thirds (64%) were using email to contact other healthcare professionals (Brooks 2006).

In primary care, email is routinely used by healthcare professionals to communicate within and between institutions about a range of issues, from diagnoses to logistical issues. Messages can convey multiple topics and can be sent to several recipients (Stiles 2007). Healthcare professionals can use email to request prescriptions from pharmacists; in the US this has been shown to reduce the enquiries pharmacists make about handwritten prescriptions (Podichetty 2004).

Email can also provide a facility for referring patients; it allows requests to be sent between clinicians or their offices quickly, and clerical staff can be integrated into the system to maintain records of referrals (Kassirer 2000). It can also be used to obtain information from staff at hospital laboratories, for instance, to obtain test results (Couchman 2005).

For surgeons practising in remote locations internationally, email communication can create valuable access to outside opinion, since it allows low‐cost communication of photographic images. More traditional methods have included using the telephone or fax machines, but email can offer a richness of communication that these methods cannot. Digital photographs for diagnosis have proven useful in several fields of surgery (Stutchfield 2007). Similar systems have been used for surgical pre‐screening to guide referral to relevant centres outside of remote areas, or to provide prior information for visiting surgeons travelling to remote areas of the world (Lee 2003). It can be used in areas of conflict such as the Middle East to support local doctors and improve healthcare (Patterson 2007).

Public health systems rely on healthcare professionals' reporting of data on disease outbreaks in order to respond and plan accordingly. Laboratory reporting has seen improved notification rates of late, but the maintenance of good communication is vital (Ward 2008), and many healthcare professionals typically fail to comply because of a lack of information and reminders (Voss 1992). Email communication can offer a method of reminding healthcare professionals about notification, and provide links to websites with the appropriate forms and a list of notifiable diseases.

Advantages and disadvantages

The key advantages of email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals include the following (adapted from Freed 2003; Car 2004a).

Timely and low cost delivery of information (relative to conventional mail) (Houston 2003).

Convenience: emails can be sent and subsequently read at an opportune time, outside of traditional office hours where convenient (Leong 2005).

'Read receipts' can be used to confirm that communications have been received.

Relative to oral communication, the written nature of the communication can be valuable as reference for the recipient, aiding recall and providing evidence of the exchange (Car 2004a; Car 2004b).

Emails can be archived in online or offline folders separate from the inbox of the email account so that they do not use up space in the inbox but can be kept for reference (Car 2004a; Car 2004b).

Email networks allow the wide dissemination of information amongst a specific group of professionals (Thede 2007).

Digital images can be transferred easily and quickly between healthcare professionals (Stutchfield 2007).

Email's convenience facilitates communication among healthcare professionals that may otherwise not occur (Stiles 2007), thus extending the breadth of communication.

There are, however, some potential downsides.

There is evidence of concerns regarding privacy, confidentiality, and potential misuse of information when healthcare professionals communicate via email (Harris 2001; Kleiner 2002; Moyer 2002; Katzen 2005).

Physicians may be wary of the potential for email to generate an increased workload, as a consequence of the depth of content permitted by this method of communication (Podichetty 2004).

Potential medico‐legal issues (including informed consent and use of non‐encrypted email) exist when communicating information about a patient via email (Bitter 2000).

Email is not appropriate for all communication situations, particularly those requiring urgency, since email may not be read immediately upon receipt (Stiles 2007).

Email as a communication tool provides a different context for interaction. The various layers of communication experienced during a face‐to‐face encounter or a telephone call are lost in an email: for example, the emotive cues from vocal intonation or body language (Car 2004a).

Technological issues may occur, such as recipients having a full inbox causing email to bounce back to the sender (Virji 2006).

Systems may be at risk of failure: for instance, a loss of the link to a central server (a computer which provides services used by other computers, such as email) (Car 2008). There may be several causes for technological system failure, from local power failure to natural disasters.

The potential for human error can lead to unintended content or incorrect recipients.

Quality and safety issues

The main quality and safety issues around email communication include: confidentiality, potential for errors and ensuing liability, identifying clinical situations where email communication between healthcare professionals is inefficient or inappropriate, incorporating email into existing work patterns and achievable costs (Kleiner 2002; Gaster 2003; Gordon 2003; Hobbs 2003; Houston 2003; Car 2004b).

Privacy and confidentiality are a formidable challenge in the adoption of email communication (Couchman 2001; Moyer 2002). Web messaging systems can address issues around security and liability that are associated with conventional email communication, since they offer encryption capability and access controls (Liederman 2003). However, not all healthcare institutions are capable of providing such a facility, and rely instead on standardised mail (Car 2004b).

Medico‐legal issues that are of substantial concern when implementing email communication in practice include potential liability for breaches in security allowing a third party to access confidential medical information, and the possibility of identity fraud (Moyer 1999; Couchman 2001; Car 2004b).

Suggestions for minimising the legal risks of using email in practice have included adherence to the same strict data protection rules that must be followed in business and industry, and adequate infrastructure to provide encrypted secure email transit and storage (Car 2004b).

Education and training results in capable and competent end‐users of any technology. This can be costly and time consuming, but enhances the chance of effective implementation of such systems and thus should be a priority. As well as the requirement for initial training, ongoing support is usually necessary to ensure continuing use and further development (Car 2008).

We aimed to investigate these issues further in the context of the studies included in this review.

Forms of electronic mail

In the absence of a standardised email communication infrastructure in the healthcare sector, email has been adopted in an ad‐hoc fashion and this has included the use of unsecured and secured email communication.

Standard unsecured email is email that is sent unencrypted. Secured email is encrypted; encryption transforms the text into an uninterpretable format as it is transferred across the Internet. Encryption protects the confidentiality of the data, but both sender and recipient must have the appropriate software for encryption and decoding (TechWeb Network 2008).

Secure email also includes various specifically developed applications that utilise web messaging. Such portals provide proformas into which users can enter their message. The message is sent to the recipient in the manner of an email (TechWeb Network 2008).

Secure websites are distributed by secure web servers. Web servers store and disseminate web pages. Secure servers ensure data from an Internet browser is encrypted before being uploaded to the relevant website. This makes it difficult for the data to be intercepted and deciphered (TechWeb Network 2008).

There are significant differences in terms of the applications. Bespoke secure email programmes may incorporate special features such as standard forms guiding the use and content of the email sent, ability to show read receipts (in order to confirm the addressee has received the correspondence) and, if necessary, facilities for receiving payment (Liederman 2005). However, they are costly to set up and may require a greater degree of skill on the part of the user than standard unsecured email (Katz 2004). For the purpose of the review we included all forms of email, although secured versus unsecured email was to be considered in a subgroup analysis.

Methods of accessing email

Methods of accessing the Internet and thus an email account have changed with time. Traditionally access was via a personal computer or laptop at home or work, connecting to the Internet using a fixed line. There are now several methods of accessing the Internet including via mobile devices. For the purposes of the review we included all access methods.

Objectives

To assess the effects of email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals on healthcare professional outcomes, patient outcomes, health service performance, and service efficiency and acceptability, when compared to other forms of communicating clinical information.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised trials. We included trials with individual and cluster randomisation. We included controlled before and after (CBA) studies where they met the following criteria:

there were at least two intervention sites and two control sites;

the pre‐ and post‐intervention periods of measurement for the control and intervention groups were the same);

the intervention and control groups were comparable on key characteristics.

We included interrupted time series (ITS) studies that met the following criteria:

the intervention occurred at a clearly defined point in time, and this was specified by the researchers;

there were at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention was introduced.

We also included relevant trials with economic evaluations.

Types of participants

We included all healthcare professionals regardless of age, gender and ethnicity. We included studies in all settings: i.e. primary care settings (services of primary health care), outpatient settings (outpatient clinics), community settings (public health settings), and hospital settings. We did not exclude studies according to the type of healthcare professional (e.g. surgeon, nurse, doctor, allied staff).

We considered participants originating the email communication, receiving the email communication, and copied into the email communication.

Types of interventions

We included studies in which email was used for two‐way clinical communication between healthcare professionals to facilitate inter‐service consultation. We included interventions that used email to allow healthcare professionals to contact each other: e.g. to send information about a patient, to provide notifications for public health purposes, or to facilitate the sharing of relevant information about the healthcare institution.

We included interventions that used email in any of the following forms for communication between healthcare professionals:

unsecured standard email to or from a standard email account;

secure email which is encrypted in transit and sent to or from a standard email account with the appropriate encryption decoding software;

web messaging, whereby the message is entered into a pro‐forma which is sent to a specific email account, the address of which is not available to the sender.

We included all methods of accessing email.

We excluded studies of email between professionals solely for educational purposes. We excluded studies which considered the general use of email for communication between healthcare professionals for multiple purposes but did not separately consider clinical communication between healthcare professionals. Studies where email was one part of a multifaceted intervention were included where the effects of the email component were individually reported, even if they did not represent the primary outcome. However, these were only considered where they achieved the appropriate statistical power. Where this could not be determined or where it was not possible to separate the effects of the multifaceted intervention they were not included.

We included studies comparing email communication to no intervention, as well as comparing it to other modes of communication such as face‐to‐face, postal letters, calls to a landline or mobile telephone, text messaging using a mobile telephone, and if applicable, automated versus personal emails.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes of interest focused on whether the email had been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, and secondary outcomes focused on whether email was an appropriate mode of communication.

Primary outcomes

Healthcare professional outcomes resulting from whether the email had been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, e.g. professional knowledge and understanding, inter‐professional communication and relationships, professional behaviour, actions or performance.

Patient outcomes associated with whether the email had been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, such as patient understanding, patient health status and well‐being, treatment outcomes, skills acquisition, support, patient behaviours or actions.

Health service outcomes associated with whether email had been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient as intended by the sender, e.g. service use, management or coordination of a health problem.

Harms e.g. effects on safety or quality of care, breaches in privacy, technology failures.

Secondary outcomes

Professional, patient or carer outcomes associated with whether email was an appropriate mode of communication, e.g. knowledge and understanding, effects on professional or professional‐carer communication, evaluations of care (such as convenience, acceptability, satisfaction).

Health service outcomes associated with whether email was an appropriate mode of communication, e.g. use of resources or time, costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched:

Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Specialised Register (searched January 2010);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library Issue 9, 2013) (searched September 2013);

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to August 2013);

EMBASE (OvidSP) (1974 to August 2013);

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1967 to August 2013);

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (1982 to August 2013);

ERIC (CSA) (1965 to January 2010).

We present detailed search strategies in Appendices 2 to 6 (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6). John Kis‐Rigo, Trials Search Co‐ordinator at the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group and Nia Roberts, Information Specialist at the University of Oxford, compiled the strategies.

There were no language or date restrictions.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched for grey literature via theses and dissertation repositories, trials registers and Google Scholar.

We searched using the following sources:

Australasian Digital Theses Program (http://trove.nla.gov.au/) (searched November 2013);

Index to Theses (http://www.theses.com/) (searched November 2013);

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (http://www.ndltd.org/serviceproviders/scirus‐etd‐search) (searched November 2013);

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I: Health & Medicine (http://search.proquest.com/health/advanced?accountid=13042) (searched November 2013);

Clinical trials register (Clinicaltrials.gov) (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home (searched November 2013);

WHO Clinical Trial Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx (searched November 2013);

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/) (searched November 2013);

Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com) (searched November 2013). We examined first 500 results for each set of terms, date restricted to 2010 to 2013.

We searched online trials registers for ongoing and recently completed studies and contacted authors where relevant. We kept detailed records of all the search strategies applied.

Reference lists

We examined the reference lists of retrieved relevant studies.

Correspondence

We contacted the authors of included studies for advice as to any further studies or unpublished data. Many of the authors of included studies were also experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HA and CG) independently assessed the potential relevance of all titles and abstracts identified from electronic searches. We retrieved full‐text copies of all articles judged to be potentially relevant. Both HA and CG independently assessed these retrieved articles for inclusion. Where HA and CG could not reach consensus a third author, MC, examined these articles.

During a meeting of all review authors, we verified the final list of included and excluded studies. We resolved any disagreements about particular studies by discussion. Where the description of a study was insufficiently detailed to allow us to judge whether it met the review's inclusion criteria, we contacted the study authors to obtain more detailed information to allow a final judgement to be made regarding inclusion or exclusion. We have retained detailed records of these communications.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from included studies using a standard form derived from the data extraction template provided by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. We extracted the following data.

General information: title, authors, source, publication status, date published, language, review author information, date reviewed.

Details of study: aim of intervention and study, study design, location and details of setting, methods of recruitment of participants, inclusion/exclusion criteria, ethical approval and informed consent, consumer involvement.

Assessment of study quality: key features of allocation, contemporaneous data collection for intervention and control groups; and for interrupted time series, number of data points collected before and after the intervention, follow‐up of participants.

Risk of bias: data to be extracted depended on study design (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies).

Participants: description, geographical location, setting, number screened, number randomised, number completing the study, age, gender, ethnicity, socio‐economic grouping and other baseline characteristics, health problem, diagnosis, treatment.

-

Intervention: description of the intervention and control including rationale for intervention versus the control (usual care):

delivery of the intervention including email type (standard unsecured email, secure email, web portal or hybrid);

type of clinical information communicated (e.g. diagnostic test results, information on an individual patient);

content of communication (e.g. text, image);

purpose of communication (e.g. obtaining information, providing information);

communication protocols in place;

who delivers the intervention (e.g. healthcare professional, administrative staff);

how consumers of interventions are identified;

sender of first communication (health service, professional, patient or carer, or both);

recipients of first communication (health service, professional, patient or carer, or both);

whether communication is responded to (content, frequency, method of media);

any co‐interventions included;

duration of intervention;

quality of intervention;

follow‐up period and rationale for chosen period.

Outcomes: principal and secondary outcomes, methods for measuring outcomes, methods of follow‐up, tools used to measure outcomes, whether the outcome is validated.

Results: for outcomes and timing of outcome assessment, control and intervention groups if applicable.

HA and PS piloted the data extraction template to allow for unforeseen variations in studies. For the included study, both HA and PS independently extracted data. HA and PS discussed and resolved any discrepancies between the review authors' data extraction sheets. Where necessary, we involved YP to resolve discrepancies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011) and the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2013), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias (baseline imbalance between groups and contamination). We considered blinding separately for different outcomes where appropriate (e.g. blinding may have the potential to differently affect subjective versus objective outcome measures). We judged each item as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria provided by Higgins 2011, and provided a quote from the study report and a justification for our judgement for each item in the risk of bias table.

RCTs were deemed to be at the highest risk of bias if they were scored as high or unclear risk of bias for either the sequence generation or allocation concealment domains, based on growing empirical evidence that these factors are particularly important potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011).

In all cases, two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion to reach consensus. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods as required. We incorporated the results of the risk of bias assessment into the review through standard tables, and systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the elements, leading to an overall assessment the risk of bias of included studies and a judgment about the internal validity of the review's results.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, when outcomes were measured in a standard way, we reported the odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) and confidence intervals (CI). For continuous data, where outcomes were measured in a standard way across studies, we reported the mean values for the intervention versus control group. It was not possible to calculate a mean difference and confidence intervals because standard deviations were not available and the data required to calculate these (mean difference, sample size and standard error values) were not available. Therefore, we have presented data as per the published report.

Data synthesis

As we identified only one study it was not possible to conduct a quantitative meta‐analysis. The methods that we would have applied had data analysis and pooling been possible are outlined in Appendix 1 and will be applied to future updates of the review.

Ensuring relevance to decisions in healthcare (consumer input)

We asked two consumers, a health services researcher (UK) and healthcare consultant (Saudi Arabia), to comment on the completed review before submitting the review for the peer‐review process, with a view to improving the applicability of the review to potential users. The review also received feedback from two consumer referees as part of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group's standard editorial process.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

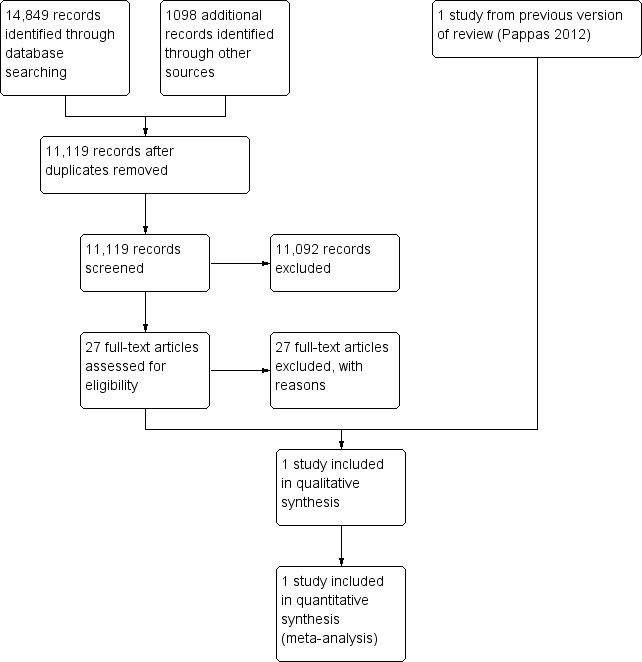

We conducted a common search for this review and the linked review 'Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals' (Atherton 2012). Relevant studies were allocated to each review after being assessed at the full text stage. Figure 1 shows the search and selection process at the update stage.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

No new studies were identified for this update. One randomised controlled trial involving 327 patients and 159 primary care providers at baseline (Feldstein 2006, see also Characteristics of included studies) was identified in the previous version of this review (Pappas 2012). This trial assessed two intervention groups (electronic medical record (EMR) reminder and EMR reminder plus patient reminder) and one control group (usual care pathway). For the purposes of this review we were interested in the comparison between the EMR reminder group and the usual care group. Feldstein 2006 estimated that 100 patients per group were needed to have an 80% chance of detecting an effect size of 0.40. Three hundred and twenty‐seven female patients were randomised across three groups, and after drop outs there were 101 in the usual care group, 101 in the EMR reminder group and 109 in the EMR reminder + patient reminder group. We only report data from the usual care and EMR reminder group in the review.

This US study was set in a Pacific Northwest, non‐profit, health maintenance organisation (HMO) with about 454,000 members. Randomised women were aged 50 to 89, had suffered a fracture in 1999 and had not received bone mineral density (BMD) measurement or medication for osteoporosis. The intervention was delivered to the primary care physicians of the randomised female patients. All healthcare professionals within the HMO had access to an EMR‐based email account with the capacity to reply to messages received.

Interventions

The purpose of the intervention was to increase guideline‐recommended osteoporosis treatment. Primary care providers in both intervention arms (EMR and EMR + patient reminder) received patient‐specific EMR 'in‐basket' messages for their enrolled patients from the chairman of the osteoporosis quality improvement committee. 'In basket' messages are an EMR‐based email communication used exclusively for patient care activities.

The letter‐style message informed the provider of the patient's risk of osteoporosis based upon the patient's age and prior fracture, and stated the need for evaluation and treatment. Three months later, a reminder (specific to individual patients) was sent to primary care providers who had not ordered a BMD measurement or pharmacological osteoporosis treatment for enrolled patients. The provider could contact the message sender for additional information.

Patients in the usual care arm continued to receive care at the HMO through the normal pathway.

Outcomes

The study examined both primary and secondary outcomes relevant to this review.

Health professional outcomes

This study reported health professional actions and performance in terms of whether the care provider ordered a BMD measurement, prescribed osteoporosis medication, or both for women who had suffered a fracture.

Patient outcomes

This study reported the primary outcome of patient behaviours, in terms of the effect on women's calcium intake, regular activity and calorific expenditure, and the secondary outcome of evaluation of care in terms of satisfaction with care and services received for bone health.

Health service outcomes

No outcomes relating to health services are reported in the study.

Harms

No outcomes relating to harms are reported in the study.

Excluded studies

We excluded twenty‐seven studies at the update stage (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded the majority of these because they featured one‐way rather than two‐way communication between healthcare professionals; in cases of ambiguity, we contacted the authors directly to confirm the nature of the email communication (Atlas 2011; Lobach 2013). Other studies were excluded on the basis of study design (Quan 2013) or because the intervention was primarily educational in content (Kerfoot 2010; Schopf 2012). We also excluded if email was a component of a multifaceted intervention and the effect of email was not separately assessed (McKee 2011).

We excluded eleven studies in the original review (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We excluded eight of these because they concerned one‐way rather than two‐way communication between healthcare professionals (Lester 2004; Feldman 2005; Mandall 2005; Lester 2006; Edward 2007; Ward 2008; Johansson 2009; Chen 2010). In three studies, email was part of a multifaceted intervention and the email component was not assessed separately (Jaatinen 2002; Persell 2008; Ward 2008). One study concerned communication for educational purposes (Murtaugh 2005).

Risk of bias in included studies

We based the risk of bias ratings on the published report (Feldstein 2006). Where aspects of the trial methodology were unclear, we contacted the author of the study to obtain further information .

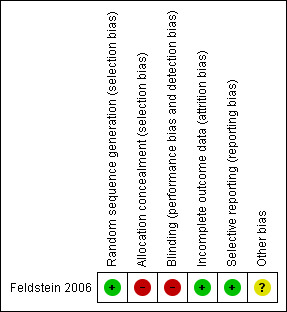

Figure 2 summarises the risk of bias for the included study. Further details can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

A computer random‐number generator was used to produce the random sequence. We judged allocation concealment to be inadequate. The study report does not describe the method of concealment, and the author confirmed that the person allocating could tell the group to which the participants were assigned.

Blinding

Neither the study nurse conducting the interventions nor the participants (providers or patients) were blinded to group assignment. However, the study analyst assessing the outcomes was blinded to the treatment groups.

Incomplete outcome data

Incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed.

Selective reporting

There was no evidence of selective reporting in this study.

Other potential sources of bias

There were some other sources of bias in this study, but the overall consensus was that the risk of bias was unclear. Some instruments used to measure the outcomes were not validated, and some may have been subject to reliability issues. An example is patient‐completed questionnaires concerning activity and calorific expenditure. Such questionnaires are more at risk from reporter bias, that is, the participant gives the answers they believe they should according to social norms, rather than their true answers.

Effects of interventions

We report the effects of interventions on primary and secondary outcomes (see Data and analyses) for the included study (Feldstein 2006). We only report data for the EMR message group versus the usual care group.

Primary outcomes

Healthcare professional actions or performance

Reported outcomes relating to healthcare professional actions or performance all favoured the EMR intervention.

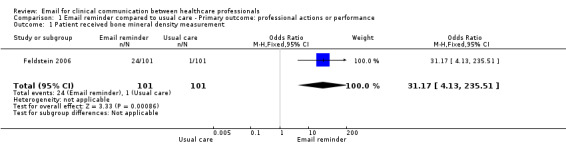

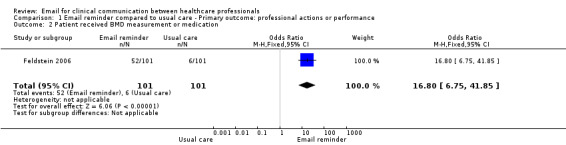

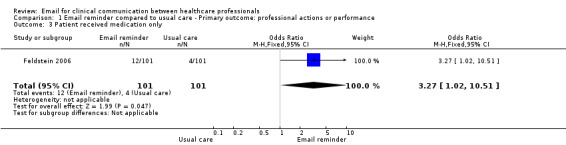

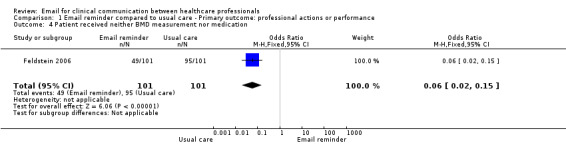

Patients whose physicians received the EMR message were more likely to receive the recommended care than those in the usual care group; specifically, a bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (OR 31.17; 95% CI 4.13 to 235.51); a BMD measurement or osteoporosis medication (OR 16.80; 95% CI 6.75 to 41.85); or osteoporosis medication only (OR 3.27; 95% CI 1.02 to 10.51). Those in the usual care group were more likely to receive neither a BMD measurement nor osteoporosis medication (OR 0.06; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.15) (see Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 1 Patient received bone mineral density measurement.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 2 Patient received BMD measurement or medication.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 3 Patient received medication only.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 4 Patient received neither BMD measurement nor medication.

The study included a regression model adjusted for fracture type, age, weight less than 127 pounds, diagnosis of osteoporosis and Charlson Comorbidity Index to predict the probability of a patient receiving the recommended care. The EMR reminder increased the probability of receiving a BMD measurement, osteoporosis medication, or both (see Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 5 Absolute change in probability of receiving BMD measurement.

| Absolute change in probability of receiving BMD measurement | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Feldstein 2006 | 0.39 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.50) |

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 6 Absolute change in probability of receiving osteoporosis measurement.

| Absolute change in probability of receiving osteoporosis measurement | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Feldstein 2006 | 0.23 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.33) |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Email reminder compared to usual care ‐ Primary outcome: professional actions or performance, Outcome 7 Absolute change in probability of receiving either a BMD measurement or osteoporosis medication.

| Absolute change in probability of receiving either a BMD measurement or osteoporosis medication | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Feldstein 2006 | 0.47 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.59) |

Patient behaviour

The study examined three measures relating to patient behaviours. The results favoured the intervention for all measures, but the difference was only significant for one measure.

Pre‐ and post‐intervention measurements in each group indicated that the women whose physicians received the EMR message had a higher calcium intake after the intervention; an increase of 194.9 mg/day from 116.5 mg/day to 1311.4 mg/day, whereas those in the usual care group had a reduced calcium intake after the intervention, reduced by 457.4 mg/day, from 1308.6 mg/day to 851.2 mg/day.

For regular activity, the mean number of participants engaging in activity long enough to break a sweat at least once a week was reduced by one for the intervention group (‐1) and increased by three in the usual care group (3). For Calorific expenditure this was decreased in both groups; in the EMR group by 770.2 Kcal from 3082.9 Kcal to 2312.7 Kcal and in the usual care group by 344.8 Kcal from 2325.7 Kcal to 1980.9 Kcal.

The study authors carried out comparison tests for all of these measures and found that there was a significant difference between the EMR and usual care groups for calcium intake (P = 0.02) but there was no significant difference between groups for reporting regular activity (P = 0.17) and calorific expenditure (P = 0.96).

Health service outcomes

No primary outcomes relating to health services were assessed in the included study.

Harms

No primary outcomes relating to harms were assessed in the included study

Secondary outcomes

Patient evaluation of care

The study examined one measure of evaluation of care, namely mean change in satisfaction with care and services received for bone health. The EMR group had a positive mean change from baseline (0.07) in satisfaction with care and the usual care group had a negative mean change from baseline (‐0.07). The differences between groups were reported as non‐significant by the authors.

No other secondary outcomes were reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review contains only one study and this study was rated at unclear to high risk of bias. Therefore, the reported results should be interpreted with caution.

The primary outcomes of interest related to whether the email had been understood and acted upon correctly by the recipient, as intended by the sender.

The study compared an electronic medical record (EMR) reminder with usual care. There was evidence that the EMR reminder changed professional actions in a positive way compared to those in the usual care group. The evidence for patient behaviour was inconclusive, with one measure finding that the EMR message impacted patient behaviour positively and two measures finding no difference between the two groups. No primary health service outcomes or harm outcomes were measured in the included study.

The secondary outcomes of interest were whether email was an appropriate mode of communication. Patient evaluation of care showed a positive increase in favour of the intervention, based on the reported data. However, it was not possible to calculate a mean difference and the study authors did not carry out a test for comparison between groups, and so this evidence is inconclusive. No other secondary outcomes were reported.

Based on the findings of this review, it is not possible to determine the benefits of email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals. The nature of the evidence base means that we are uncertain about the majority of primary and secondary outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

With only one study in the review (Feldstein 2006), the findings are incomplete with regard to outcome measures and the applicability of evidence. There were no health service outcomes or outcomes relating to harms reported in this review.

The identification of only one relevant study means that the review's applicability to other settings is minimal. The included study featured a specific type of email: an Internet portal comprising the electronic medical record, with an 'in basket' message function. The email sent to healthcare professionals concerned management of a specific condition (osteoporosis) in particular patients (those having had a fracture). Healthcare professionals could respond if they required further information, but response was not measured. This web portal type of email is very different to standard email, which we might have expected to see being used as a tool for more generic two‐way communication.

As well as targeting specific types of patient and condition, the included study was set in a HMO in the United States of America (USA), a high income country with English as the predominant language. The USA has a mixed healthcare system with both government and insurance‐based coverage schemes. The findings may not be applicable outside this setting.

In addition, the study was carried out in 2006. Developments in technology have occurred since then such as the rise of 'smartphones'. The rapid spread of the Internet has changed the landscape with regard to technology use in society. These changes pose a problem for any reviews of evidence concerning Internet‐based technologies.

Quality of the evidence

The included study had unclear to high risk of bias, with a high risk of bias for allocation concealment and blinding status. There was an uncertain risk of other types of bias; this was because we were unable to obtain some details about the study despite contact with the author.

Potential biases in the review process

Searches

As well as database searches we conducted an extensive search of the grey literature which helped to ensure that we did not miss ongoing studies and dissertation theses. Terminology is an ongoing problem when searching for evidence on new technologies, especially those used for communication. Several different terms can be used to describe email, including electronic mail, electronic messaging, web messaging, and web consultation. Our searches used a wide selection of terms and their truncations to ensure that all variations were found. However, we may have missed other relevant terms.

As we were unable to produce funnel plots, it was not possible to ascertain the likelihood of publication bias for individual outcomes. Despite our sensitive search strategy, it is possible that data were unavailable to us. For instance, if companies have carried out trials and found these results to be negative or equivocal, they may choose not to publicise these results. The need for trial registration may not be apparent to corporations embarking on their first trials.

Scope of the review

The broad question addressed in this review and the wide‐ranging criteria used for studies, participants, interventions, and outcome measures will have ensured that studies were not unnecessarily excluded. However, restricting the review to studies of two‐way communication led to the exclusion of several studies where email was used in a one‐way fashion. These included a study of email used to provide discharge summaries (Chen 2010) and another for referring patients for orthodontic treatment (Mandall 2005). Several studies attempted to influence health professional behaviour via email with regard to prescribing behaviours (Lester 2006; Edward 2007; Persell 2008), reporting of adverse drug reactions (Johansson 2009), knowledge of and management of tests pending at discharge (Dalal 2012) and provision of health care (Lester 2004; Feldman 2005; Murtaugh 2005; Atlas 2011).

These studies could be deemed relevant for a separate review considering email use between healthcare professionals for administrative purposes (e.g. discharge summaries, disease reporting and referral) or a review considering email for delivering material that facilitates changes in practice (e.g. prescribing behaviour) though this may have some overlap with reviews that consider behavioural interventions.

Unlike interventions with a directly measurable impact on health (drug treatments, surgical procedures), email is a complex intervention and its potential impact may come from any number of factors. A complex intervention is one with several interacting components. The complexity can have several dimensions; these may include the organisational levels targeted by the intervention (administrative staff, nurses, doctors, management) or degree of flexibility or tailoring of the intervention permitted (standard email allowing free text, web‐based systems with a pro‐forma for entering text) (Craig 2008). As a consequence of this complexity it may be more difficult to determine what should be tested and how, and doing this in the context of a controlled trial may be perceived as difficult. We decided to include other types of study designs as well as randomised controlled trials in this review, but only one randomised controlled trial was identified.

Possible reasons for the lack of studies meeting the inclusion criteria may be that studies approaching the use of email between healthcare professionals are firstly concerned with solutions relating to individual diseases (e.g. osteoporosis) rather than with email itself as an intervention. In addition, we must consider that for some purposes specific functionality has been developed that facilitates health professional communication. In the UK, the Electronic Prescription Service run by the NHS 'enables prescribers to send prescriptions electronically to a dispenser (such as a pharmacy) of the patient's choice' (NHS Connecting for Health 2011). The development and proliferation of sophisticated and tailored software may have negated the need to use email with its associated disadvantages, such as privacy and security concerns.

Conversely, day‐to‐day communication between healthcare professionals may not be deemed an intervention in the same way it would be if used with a patient. Especially when we consider that email is used extensively in the workplace in many sectors, the impact on patients of day‐to‐day contact between healthcare professionals may not have been considered or deemed important.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other reviews addressing the use of email between healthcare professionals. The limited literature on communication between healthcare professionals via email consists of brief reports of systems in use in clinical practice (Dhillon 2010), and discussions that include normative suggestions of how such communication could be used effectively (Thede 2007; Lomas 2008). There is consensus that email has the potential to facilitate communication between healthcare professionals (Lomas 2008; Abujudeh 2009) but effective implementation is subject to incorporating emails into allocated administration times (Dhillon 2010). Issues around workload and administration were not addressed in the included study.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

No recommendations for practice can be made given the current lack of evidence of benefit (or harm).

Implications for research.

This review highlights the need for high‐quality studies to evaluate the effects of using email for clinical communication between healthcare professionals. Future studies need to be rigorous in design and delivery, with subsequent reporting to include high‐quality descriptions of all aspects of methodology to enable appraisal and interpretation of results. Prompting the development of such studies may involve addressing the barriers to trial development and implementation, and addressing any perception that studies of health professional communication and associated effects are unnecessary.

We have highlighted the possible reasons why there may be a lack of evidence in this review. With regard to further research, it would be beneficial to consider what researchers wish to measure in carrying out trials. Physician‐related concerns to be considered would be factors such as the security of email messaging and workload concerns (Car 2004b). At the moment these factors are not addressed in the evidence base.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 February 2015 | Amended | Author's affiliation updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2009 Review first published: Issue 9, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 February 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Addition of new authors to the review, Clare Goyder, Mate Car, Carl Heneghan. No new studies were identified in the update. |

| 18 February 2014 | New search has been performed | New electronic searches performed August 2013, grey literature search November 2013. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank Yannis Pappas and Prescilla Sawmynaden, authors of the original version of this review.

We thank Mariana Bernardo for providing research support during the conduct of the review update.

We thank the staff and editors of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group, especially Megan Prictor, Sophie Hill and Sue Cole, for their prompt and helpful advice and assistance.

We thank John Kis‐Rigo, Trials Search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group, for compiling the original search strategy and working on the amended strategies for the update.

We thank Nia Roberts, Information Specialist, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, for creating and running the searches for the update.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods for application in future updates

Outlined here are methods to be applied in any future updates of this review, should studies be identified for inclusion.

Selecting outcome measures

We will list the outcomes for each trial and decide which are clinically important. The decision will be made independently by two reviewers, with a third author to check and discuss discrepancies. The decision about which outcome is most clinically important will be made irrespective of the size of the effect or its statistical significance.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

If quasi‐RCTs are included in the review we will assess and report them as at a high risk of bias on the random sequence generation item of the risk of bias tool.

If cluster RCTs are included in the review we will also assess and report the risk of bias associated with an additional domain: selective recruitment of cluster participants (described in Ryan 2013).

If CBA studies are included in the review, we will assess their risk of bias systematically using adaptations to the above tool developed by the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group, outlined in Ryan 2013. Specifically, CBA studies will be assessed against the same criteria as RCTs but reported as being at high risk of bias on both the random sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment items; and studies will be excluded from the review if intervention and control groups are not reasonably comparable at baseline.

If ITS studies are included in the review, we will assess their risk of bias systematically using adaptations to the above tool developed by the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group, outlined in Ryan 2013. Specifically, we will assess and report the following individual items for ITS studies: intervention independence of other changes; pre‐specification of the shape of the intervention effect; likelihood of intervention affecting data collection; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias; and baseline imbalance between groups and contamination.

Measures of treatment effect (where more than one study is included)

For dichotomous outcomes, we will analyse data based on the number of events and the number of people assessed in the intervention and comparison groups. We will use these to calculate the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous measures, we will analyse data based on the mean, standard deviation (SD) and number of people assessed for both the intervention and comparison groups to calculate mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. If the MD is reported without individual group data, we will use this to report the study results. If more than one study measures the same outcome using different tools, we will calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI using the inverse variance method in Review Manager 5. For CBAs we will analyse appropriate effect measures for dichotomous outcomes (RR, adjusted RR) and for continuous outcomes (relative % change postintervention, SMD).

For ITS studies we plan to report the following estimates, and their P values, from regression analyses which adjust for autocorrelation: (i) change in level of the outcome at the first point after the introduction of the intervention (immediate effect of the intervention), (ii) the post‐intervention slope minus the pre‐intervention slope (long term effect of the intervention).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster RCTs

If cluster RCTs are included we will check for unit‐of‐analysis errors. If errors are found, and sufficient information is available, we will reanalyse the data using the appropriate unit of analysis, by taking account of the intracluster correlation (ICC). We will obtain estimates of the ICC by contacting authors of included studies, or impute them using estimates from external sources. If it is not possible to obtain sufficient information to reanalyse the data we will report effect estimates and annotate 'unit‐of‐analysis error'.

Dealing with missing data

We will attempt to contact study authors to obtain missing data (participant data, outcome data, or summary data). For participant data, we will, where possible, conduct analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis; otherwise data will be analysed as reported. We will report on the levels of loss to follow‐up and assess this as a source of potential bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where studies are considered similar enough in relation to study design, setting, intervention, follow‐up and outcome measures to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we will assess the degree of heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. Heterogeneity will be quantified using the I2 statistic. An I2 value of 50% or more will be considered to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but this value will be interpreted in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value from the Chi2 test (Higgins 2011).

Where we detect substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity across included studies we will not report pooled results from meta‐analysis but will instead use a narrative approach to data synthesis. In this event we will attempt to explore possible clinical or methodological reasons for this variation by grouping studies that are similar in terms of study design, setting, intervention, follow‐up and outcome measures to explore differences in intervention effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

We will assess reporting bias qualitatively based on the characteristics of the included studies (e.g. if only small studies that indicate positive findings are identified for inclusion), and if information that we obtain from contacting experts and authors of studies suggests that there are relevant unpublished studies. If we identify sufficient studies (at least 10) for inclusion in the review we will construct a funnel plot to investigate small study effects, which may indicate the presence of publication bias. We will formally test for funnel plot asymmetry, with the choice of test made based on advice in Higgins 2011, and bearing in mind that there may be several reasons for funnel plot asymmetry when interpreting the results.

Data synthesis

The decision to meta‐analyse data or not will be based on an assessment of whether the interventions in the included trials are similar enough in terms of participants, settings, intervention, comparison and outcome measures to ensure meaningful conclusions from a statistically pooled result. Due to the anticipated variability in the populations and interventions of included studies, we will use a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis.

Only RCTs, quasi‐RCTs and cluster RCTs will be included in any meta‐analysis. Descriptive statistics will be presented for CBA and ITS studies. This will include median effect sizes, inter‐quartile ranges and any other relevant measures from the included studies.

If meta‐analysis is not possible we will group the data based on the category that best explores the heterogeneity of studies and makes most sense to the reader (i.e. by interventions, populations or outcomes). Within each category we will present the data in tables and narratively summarise the results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there are sufficient data we will conduct subgroup analysis. This will allow the examination of the effect of certain studies on the pooled effects of the intervention.

1. Age

Consideration of the acceptability to different age groups (for both healthcare professionals and patients). This will be important as there is clear evidence that the use of email is predicted by age with a clear tailing off in the generation who have not grown up in the digital age. Therefore, it is important to consider the intervention's effects in the groups which are accustomed to the technology, since it is likely to become more generalisable to the population as it ages. This will be considered where the primary studies have sought to consider age group from the outset. We will distribute patients into three age subgroups: 0 to 17, 18 to 64, over 65. This distribution was made on the basis of two surveys by The Pew Internet & American Life survey (Pew 2005).

2. Location

Location of the study will also be considered, since differing environments may condition the accessibility of the technology. For instance, we would expect communication technologies and their accessibility to differ according to country and even region within a country, such as rural or urban areas.

3. Type of email communication

Additionally, we propose to analyse the results by method of electronic mail utilised, e.g. standard email versus a secure web messaging service.

4. Year of publication

Lastly, we will consider results by year of publication, as those more recent studies may be more relevant given evidence of increasing usage and, therefore, assumed acceptability.

Sensitivity analysis

RCTs and quasi‐RCTs deemed to be at high risk of bias after examination of individual study characteristics will be removed from the analysis to examine the effect on the pooled effects of the intervention.

We will exclude studies according to the following filters:

• outlying studies after initial analysis;

• largest studies;

• unpublished studies;

• language of publication;

• source of funding (e.g. public versus industry).

Summary of findings table

We will prepare a 'Summary of findings' table to present the results of meta‐analysis, based on the methods described in chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We will present the results of meta‐analysis for the major comparisons of the review, for each of the major primary outcomes, including potential harms, as outlined in the 'Types of outcome measures' section. We will provide a source and rationale for each assumed risk cited in the table(s), and will use the GRADE system to rank the quality of the evidence using the GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro) software (Schünemann 2011). If meta‐analysis is not possible, we will present results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table format (Chan 2011).

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

| 1 | electronic mail/Multimedia |

| 2 | (electronic mail* or email* or e‐mail* or web mail* or webmail* or internet mail* or mailing list* or discussion list* or listserv*).tw.Multimedia |

| 3 | ((patient or health or information or web or internet) adj portal*).tw.Multimedia |

| 4 | (patient adj (web* or internet)).tw.Multimedia |

| 5 | ((web* or internet) adj5 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or sent or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 6 | ((www or electronic* or online or on‐line) adj2 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 7 | ((online or on‐line or web* or internet) adj4 (service* or intervention* or therap* or treatment* or counsel*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 8 | (e‐communication* or e‐consult* or econsult* or e‐visit* or evisit* or e‐refer* or erefer* or e‐booking* or e‐prescri* or eprescri*).tw.Multimedia |

| 9 | exp internet/Multimedia |

| 10 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9Multimedia |

| 11 | exp professional patient relations/Multimedia |

| 12 | professional family relations/Multimedia |

| 13 | ((professional* or physician* or doctor* or clinician* or therapist* or dentist* or psychiatrist* or surgeon* or nurse*) adj2 (patient* or family or carer* or caregiver* or care giver*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 14 | exp interprofessional relations/Multimedia |

| 15 | interdisciplinary communication/Multimedia |

| 16 | ((professional* or interdisciplinary) adj3 (relation* or discussion* or collaborat* or communicat*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 17 | patient care team/Multimedia |

| 18 | interprofessional.tw.Multimedia |

| 19 | exp education continuing/Multimedia |

| 20 | continuing medical education.tw.Multimedia |

| 21 | staff development/Multimedia |

| 22 | ((professional or staff) adj (development or meeting* or forum)).tw.Multimedia |

| 23 | exp "referral and consultation"/Multimedia |

| 24 | clinical communication.tw.Multimedia |

| 25 | (consult* or visit? or referral*).tw.Multimedia |

| 26 | exp telemedicine/Multimedia |

| 27 | (telemedicine or telehealth or telecare).tw.Multimedia |

| 28 | disease notification/Multimedia |

| 29 | (disease* adj2 notif*).tw.Multimedia |

| 30 | reminder systems/Multimedia |

| 31 | exp "appointments and schedules"/Multimedia |

| 32 | office visits/Multimedia |

| 33 | (remind* or appointment*).tw.Multimedia |

| 34 | exp drug prescriptions/Multimedia |

| 35 | (prescrib* or prescription*).tw.Multimedia |

| 36 | diagnostic tests routine/Multimedia |

| 37 | diagnostic services/Multimedia |

| 38 | (diagnostic adj (test* or service*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 39 | (test* adj3 result*).tw.Multimedia |

| 40 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39Multimedia |

| 41 | 10 and 40Multimedia |

| 42 | randomized controlled trial.pt.Multimedia |

| 43 | controlled clinical trial.pt.Multimedia |

| 44 | clinical trial.pt.Multimedia |

| 45 | evaluation studies.pt.Multimedia |

| 46 | comparative study.pt.Multimedia |

| 47 | random*.tw.Multimedia |

| 48 | placebo*.tw.Multimedia |

| 49 | trial.tw.Multimedia |

| 50 | research design/Multimedia |

| 51 | follow up studies/Multimedia |

| 52 | prospective studies/Multimedia |

| 53 | cross over studies/Multimedia |

| 54 | (experiment* or intervention*).tw.Multimedia |

| 55 | (pre test or pretest or post test or posttest).tw.Multimedia |

| 56 | (preintervention or postintervention).tw.Multimedia |

| 57 | time series.tw.Multimedia |

| 58 | (cross over or crossover or factorial* or latin square).tw.Multimedia |

| 59 | (assign* or allocat* or volunteer*).tw.Multimedia |

| 60 | (control* or compar* or prospectiv*).tw.Multimedia |

| 61 | (impact* or effect? or chang* or evaluat*).tw.Multimedia |

| 62 | 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61Multimedia |

| 63 | exp animals/ not humans.sh.Multimedia |

| 64 | 62 not 63Multimedia |

| 65 | 41 and 64Multimedia |

| 66 | (2010* or 2011* or 2012* or 2013*).ed,ep,dc.Multimedia |

| 67 | 65 and 66Multimedia |

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

| 1 | e‐mail/Multimedia |

| 2 | (electronic mail* or email* or e‐mail* or web mail* or webmail* or internet mail* or mailing list* or discussion list* or listserv*).tw.Multimedia |

| 3 | ((patient or health or information or web or internet) adj portal*).tw.Multimedia |

| 4 | (patient adj (web* or internet)).tw.Multimedia |

| 5 | ((web* or internet) adj5 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or sent or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 6 | ((www or electronic* or online or on‐line) adj2 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 7 | ((online or on‐line or web* or internet) adj4 (service* or intervention* or therap* or treatment* or counsel*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 8 | (e‐communication* or e‐consult* or econsult* or e‐visit* or evisit* or e‐refer* or erefer* or e‐booking* or e‐prescri* or eprescri*).tw.Multimedia |

| 9 | Internet/Multimedia |

| 10 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9Multimedia |

| 11 | doctor nurse relation/ or doctor patient relation/ or nurse patient relationship/Multimedia |

| 12 | human relation/Multimedia |

| 13 | public relations/Multimedia |

| 14 | interdisciplinary communication/Multimedia |

| 15 | ((professional* or interdisciplinary) adj3 (relation* or discussion* or collaborat* or communicat*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 16 | interprofessional.tw.Multimedia |

| 17 | continuing education/Multimedia |

| 18 | continuing medical education.tw.Multimedia |

| 19 | ((professional or staff) adj (development or meeting* or forum)).tw.Multimedia |

| 20 | patient referral/ or patient scheduling/Multimedia |

| 21 | consultation/Multimedia |

| 22 | clinical communication.tw.Multimedia |

| 23 | (consult* or visit? or referral*).tw.Multimedia |

| 24 | exp telehealth/Multimedia |

| 25 | (telemedicine or telehealth or telecare).tw.Multimedia |

| 26 | (disease* adj2 notif*).tw.Multimedia |

| 27 | reminder system/Multimedia |

| 28 | (remind* or appointment*).tw.Multimedia |

| 29 | (patient* adj2 schedul*).tw.Multimedia |

| 30 | *prescription/Multimedia |

| 31 | (prescrib* or prescription*).tw.Multimedia |

| 32 | diagnostic test/Multimedia |

| 33 | preventive health service/Multimedia |

| 34 | (diagnostic adj (test* or service*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 35 | (test* adj3 result*).tw.Multimedia |

| 36 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35Multimedia |

| 37 | 10 and 36Multimedia |

| 38 | randomized controlled trial/Multimedia |

| 39 | controlled clinical trial/Multimedia |

| 40 | single blind procedure/ or double blind procedure/Multimedia |

| 41 | crossover procedure/Multimedia |

| 42 | random*.tw.Multimedia |

| 43 | trial.tw.Multimedia |

| 44 | placebo*.tw.Multimedia |

| 45 | ((singl* or doubl*) adj (blind* or mask*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 46 | (experiment* or intervention*).tw.Multimedia |

| 47 | (pre test or pretest or post test or posttest).tw.Multimedia |

| 48 | (preintervention or postintervention).tw.Multimedia |

| 49 | (cross over or crossover or factorial* or latin square).tw.Multimedia |

| 50 | (assign* or allocat* or volunteer*).tw.Multimedia |

| 51 | (control* or compar* or prospectiv*).tw.Multimedia |

| 52 | (impact* or effect? or chang* or evaluat*).tw.Multimedia |

| 53 | time series.tw.Multimedia |

| 54 | 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53Multimedia |

| 55 | 37 and 54Multimedia |

| 56 | (2010* or 2011* or 2012* or 2013*).dp,dd,em,yr.Multimedia |

| 57 | 55 and 56Multimedia |

Appendix 4. PsycINFO (OvidSP) search strategy

| 1 | computer mediated communication/Multimedia |

| 2 | electronic communication/Multimedia |

| 3 | (electronic mail* or email* or e‐mail* or web mail* or webmail* or internet mail* or mailing list* or discussion list* or listserv*).tw.Multimedia |

| 4 | ((patient or health or information or web or internet) adj portal*).tw.Multimedia |

| 5 | (patient adj (web* or internet)).tw.Multimedia |

| 6 | ((web* or internet) adj5 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or sent or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 7 | ((www or electronic* or online or on‐line) adj2 (messag* or communicat* or contact* or transmi* or transfer* or request* or send* or deliver* or receiv* or receipt* or feedback or letter* or interactiv* or input* or report* or order* or forum or appointment* or booking* or remind* or referral* or consult* or prescri* or test result?)).tw.Multimedia |

| 8 | ((online or on‐line or web* or internet) adj4 (service* or intervention* or therap* or treatment* or counsel*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 9 | (e‐communication* or e‐consult* or econsult* or e‐visit* or evisit* or e‐refer* or erefer* or e‐booking* or e‐prescri* or eprescri*).tw.Multimedia |

| 10 | internet/Multimedia |

| 11 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10Multimedia |

| 12 | psychotherapeutic processes/ or therapeutic processes/Multimedia |

| 13 | ((professional* or physician* or doctor* or clinician* or therapist* or dentist* or psychiatrist* or surgeon* or nurse*) adj2 (patient* or family or carer* or caregiver* or care giver*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 14 | exp Employee Interaction/Multimedia |

| 15 | interdisciplinary treatment approach/Multimedia |

| 16 | ((professional* or interdisciplinary) adj3 (relation* or discussion* or collaborat* or communicat*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 17 | interprofessional.tw.Multimedia |

| 18 | exp continuing education/Multimedia |

| 19 | continuing medical education.tw.Multimedia |

| 20 | professional development/Multimedia |

| 21 | ((professional or staff) adj (development or meeting* or forum)).tw.Multimedia |

| 22 | professional referral/ or self referral/Multimedia |

| 23 | clinical communication.tw.Multimedia |

| 24 | (consult* or visit? or referral*).tw.Multimedia |

| 25 | telemedicine/Multimedia |

| 26 | (telemedicine or telehealth or telecare).tw.Multimedia |

| 27 | (disease* adj2 notif*).tw.Multimedia |

| 28 | (remind* or appointment* or visit* or schedul*).tw.Multimedia |

| 29 | exp "Prescribing (Drugs)"/ or Prescription Drugs/Multimedia |

| 30 | (prescrib* or prescription*).tw.Multimedia |

| 31 | (diagnostic adj (test* or service*)).tw.Multimedia |

| 32 | (test* adj3 result*).tw.Multimedia |

| 33 | 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32Multimedia |

| 34 | 11 and 33Multimedia |

| 35 | random*.ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |

| 36 | (experiment* or intervention*).ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |

| 37 | trial*.ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |

| 38 | placebo*.ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |

| 39 | ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |

| 40 | treatment effectiveness evaluation/Multimedia |

| 41 | mental health program evaluation/Multimedia |

| 42 | (pre test or pretest or post test or posttest).ti,ab,hw,id.Multimedia |