Abstract

Identification of risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease in adults could facilitate their appropriate vaccine recommendations. We conducted a systematic literature review (last 10 years in PubMed/Embase) to identify quantitative estimates of risk factors for severe RSV infection outcomes in high-income countries. Severe outcomes from RSV infection included hospitalization, excess mortality, lower respiratory tract infection, or a composite measure: severe RSV, which included these outcomes and others, such as mechanical ventilation and extended hospital stay. Among 1494 articles screened, 26 met eligibility criteria. We found strong evidence that the following increased the risk of severe outcomes: age, preexisting comorbid conditions (eg, cardiac, pulmonary, and immunocompromising diseases, as well as diabetes and kidney disease), and living conditions (socioeconomic status and nursing home residence). The frequency of severe outcomes among younger adults with comorbidities was generally similar to that experienced by older adults, suggesting that immunosenescence and chronic conditions are both contributing factors for elevated risk.

Trial registration

PROSPERO (CRD42022315239).

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, risk factors, severe

Older age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, immunodeficiency, and crowded living conditions were associated with more severe respiratory syncytial virus outcomes in adults. The increase in relative risk associated with older age was comparable to that associated with comorbidities.

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was first identified in chimpanzees in 1956, and RSV infection has been reported in adults with pneumonia for >50 years [1]. However, it was only in the 1990s that epidemiologic studies suggested that the clinical impact of RSV in certain adult populations—including those aged ≥65 years with chronic heart or lung diseases or immunocompromised status—may be similar to that of nonpandemic influenza [1]. Recent estimates from US-based meta-analyses indicate that annually there may be 159 000 hospitalizations and 9500 to 12 700 inpatient deaths from RSV infection in adults aged >65 years [2]. Globally there may be 787 000 RSV-related hospitalizations and 47 000 related deaths annually in high-income countries alone [3].

Until recently, there were limited management options for adult RSV infections [4, 5]. Only 1 antiviral drug, ribavirin, is currently used to treat RSV infection in adults who are immunocompromised; however, high-quality evidence of efficacy [6] in this population is lacking, and no large studies supporting its use exist in older adults [7]. RSV vaccines (Arexvy, GlaxoSmithKline; Abrysvo, Pfizer) have recently been approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease in older adults (≥60 years) in the United States [4, 5] and European Union [8]. On 21 June 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that persons aged ≥60 years may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine via shared clinical decision making (ie, based on discussion between the patient and health care provider to determine whether the RSV vaccination is right for the patient) [7, 9].

With the recent approvals of the first RSV vaccines, it is critical to understand risk factors for severe RSV infection outcomes, which can inform risk-benefit assessments regarding population-level vaccine programs as well as discussions between physicians and patients regarding RSV vaccination. We performed a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify quantitative estimates of the relative risk of severe RSV infection outcomes in adults with comorbid conditions and other patient characteristics, including age, type of residential area, and nursing home residence. Our results may be used for vaccine program policy purposes, providing information for policy makers on adult populations that would potentially benefit the most from effective RSV vaccines as they become available for different age groups.

METHODS

The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration CRD42022315239).

Search Strategy

Articles published in Embase and PubMed from 7 March 2012 to 7 March 2022 were searched. The systematic electronic database searches were supplemented by hand searches in the bibliographies of articles identified in the systematic database searches. The PubMed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

For this review, severe RSV infection outcomes of interest included RSV-associated hospitalization, mortality, lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) or pneumonia, or a composite measure that included 1 or all of the following outcomes: hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, emergency department visit, reconsultation with new or worsened symptoms, receipt of mechanical/noninvasive ventilation or vasopressor support, mortality, pneumonia, myocarditis, or encephalitis. We sought results for all individuals aged ≥18 years and by age group (eg, 18–64 and ≥65 years) and the presence or absence of comorbid conditions or other potential risk factors for severe RSV disease outcomes.

Inclusion was limited to English-language articles from high-income countries as classified by the World Bank [10]. We focused the review on high-income countries in hopes of collating a more homogeneous group of studies from which we could draw conclusions, because risk factors for severe disease would likely differ in developed vs developing countries. The selection criteria are included in the Supplementary Table 2. The current search for risk factors for severe RSV infection outcomes was part of a larger systematic literature search, which identified studies that presented data on the prevalence or incidence of RSV outcomes of interest, as well as descriptive analyses of patient characteristics for those with poor outcomes from adult RSV infection (Supplementary Table 2). Literature review results for these other outcomes are not reported in this article.

Screening and Data Extraction

The study selection process was performed in 2 phases (level 1, titles and abstracts; level 2, full-text articles) independently by 2 researchers (M. L., W. N., J. M., A. N.) to determine eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, as documented in a PRISMA 2020 chart (Supplementary material). Where there was disagreement about study inclusion, the final determination was made by a third researcher (J. M., A. N., A. M.). Data were extracted from full-text articles by 1 researcher and checked against the published work for correctness by a second researcher.

Quality Assessment of Individual Studies

For each study, 1 researcher conducted a quality assessment according to the standards recommended by CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) for case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies. Completed quality assessments were checked by a second researcher.

RESULTS

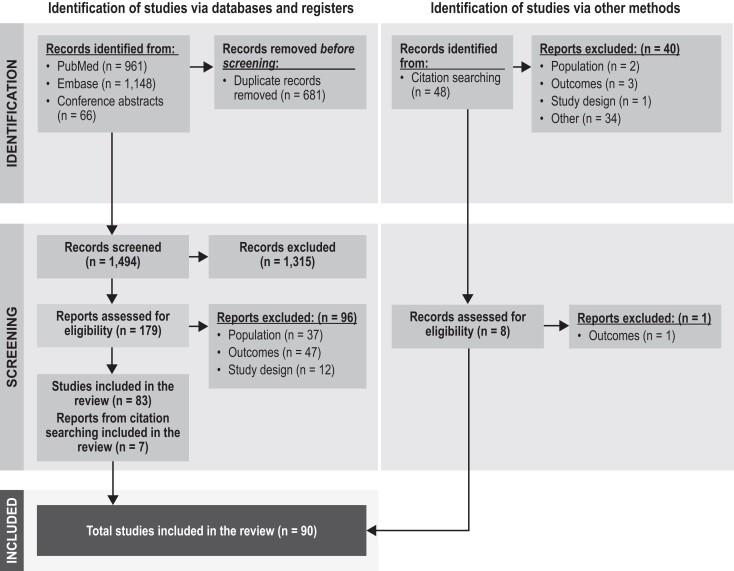

The database and hand searches resulted in 1542 titles and abstracts (1494 unique entries after removal of duplicates) for the level 1 screen. Of these, 187 were retained for the level 2 screen: 90 articles were then passed through for data extraction and 1 was excluded because of data duplication (Figure 1). The quality assessments based on the CASP checklists showed that the studies generally met the criteria in terms of clarity of the research aims, appropriateness of the recruitment method, measurement of exposure and outcome, and selection of controls for case-control studies. However, reporting of how confounding variables were handled in each study was limited. The CASP checklists do not provide a scoring system. The quality assessments are summarized in Supplementary Tables 3 to 5.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram for studies. Of the 90 included studies, 89 were extracted, and 26 reported risk factors for hospitalization, mortality, lower respiratory tract infection or pneumonia, and severe outcomes.

This article focuses on quantitative estimates of the relative risks of severe RSV infection for various patient characteristics. Of the 89 articles identified for extraction, 26 are presented in this review that include estimates of the relative risk of RSV hospitalization, mortality, LRTI or pneumonia, or severe RSV in adults for various age groups, comorbid conditions, or living conditions. Data originated in the United States (13 studies), Europe (6 studies), East Asia (5 studies), and New Zealand (2 studies). Diagnosis of RSV infection was based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in 14 studies; viral culture or antigen/antibody testing in 4; PCR or antigen/antibody testing in 2; PCR or culture in 3; PCR, culture, or antigen/antibody testing in 1; and diagnosis codes in 2 (Supplementary Table 6).

Relative risks were estimated in the studies as odds ratios (ORs), incidence rate ratios (IRRs), or hazard ratios, adjusted by potential confounders in most studies. Tables 1 to 3 present relative risks for 3 severe RSV infection outcomes: RSV-related hospitalization, mortality during or following an RSV hospitalization, and LRTI or pneumonia. Table 4 presents relative risks for the composite outcome: severe RSV, as defined in each source article.

Table 1.

Factors Associated With an Increased Risk of an RSV-Related Hospitalization

| Reference | Region, Country | No. of RSV Cases | Population Age, ya | Event Being Compared | Relative Risk Estimate Description | Comparators | Point Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors: demographics | ||||||||

| Schubert [11] | Austria | 103 RSV+ adults seeking care at hospital | 57 (40–73) | Need for admission for inpatient care | OR | >65 vs 18–65 y | 5.25 (2.2–12.5) | |

| Prasad [12] | New Zealand | 348 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

18–49, n = 64 50–64, n = 93 65–79, n = 118 ≥80, n = 73 |

Incidence rate/100 000 | IRR, adjusted for SES, and ethnicity | 50–64 vs 18–49 y 65–79 vs 18–49 y ≥80 vs 18–49 y |

4.63 (3.42–6.70) 13.4 (9.96–18.1) 31.3 (22.3–44.0) |

|

| Nolen [13] | Native Alaskan, US | 8 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

68 (52–77) | Incidence rate/10 000 | IRR | ≥65 vs 18–49 y | 11.9 (4.0–39.1) | |

| Wyffels [14] | US | 1795 RSV diagnosis Adults, ≥18 y: 793 in hospital and 835 outpatient |

IHHR, 77.1 (13.4) IHLR, 71.9 (17.1) OHR, 73.6 (14.5) OLR, 71.1 (12.3) |

Logistic regression prediction of hospitalization | OR, adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, previous evidence of pneumonia, number of conditions, and the number of inpatient and ED visits during the baseline period | 65–74 vs <65 y 75–84 vs <65 y ≥85 vs <65 y Female vs male |

0.93 (.62–1.39) 1.73 (1.15–2.6) 2.53 (1.67–3.84) 1.06 (.8–1.41) |

|

| Walsh [15] | US | 111 RSV adults: outpatients, 61; hospitalized, 50 | Outpatients, 56.7 (17.1) Hospitalized, 70.5 (14.7) |

Multivariable analysis of severe outcomes, hospitalization | OR adjusted for comorbid conditions and presenting symptoms | For every 10-y increase Female vs male |

1.4 (.96–2.1) 5.4 (1.2–23.8) |

|

| Risk factors: chronic conditions | ||||||||

| Schubert [11] | Austria | 103 RSV+ adults seeking care at hospital | 57 (40–73) | Need for admission for inpatient care | OR | Respiratory illness vs not Cardiac illness vs not Diabetes vs not Dialysis vs not Cancer vs not Solid organ transplant vs not |

3.35 (1.41–7.96) 4.03 (1.75–9.28) 2.96 (1.07–8.21) 3.38 (.97–11.79) 2.17 (.86–5.49) 1.82 (.66–5.02) |

|

| Prasad [16] | New Zealand | 281 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

18–49, n = 64 50–64, n = 93 65–80, n = 281 |

Incidence rate/100 000 | IRR, adjusted for ethnicity | 50–64 y, COPD vs not 65–80 y, COPD vs not 18–49 y, asthma vs not 50–64 y, asthma vs not 65–80 y, asthma vs not 18–49 y, CAD vs not 50–64 y, CAD vs not 65–80 y, CAD vs not 18–49 y, CHF vs not 50–64 y, CHF vs not 65–80 y, CHF vs not 50–64 y, stroke/TIA vs not 65–80 y, stroke/TIA vs not 18–49 y, diabetes vs not 50–64 y, diabetes vs not 65–80 y, diabetes vs not 50–64 y, ESRD vs not 65–80 y, ESRD vs not |

9.58 (6.18–14.84) 9.72 (6.33–14.94) 6.69 (4.06–11.04) 7.55 (4.92–11.59) 8.18 (5.48–12.23) 10.79 (4.41–26.41) 5.29 (3.3–8.47) 2.52 (1.74–3.67) 36.45 (14.11–94.16) 6.31 (3.14–12.7) 4.59 (2.91–7.24) 1.74 (.42–7.17) 1.43 (.63–3.26) 5.63 (2.97–10.69) 1.21 (.74–1.95) 1.69 (1.13–2.54) 6.57 (2.55–16.94) 1.06 (.26–4.29) |

|

| Nolen [13] | Native Alaskan, US | 8 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

68 (52–77) | Incidence rate/10 000 | IRR | COPD vs not Asthma vs not Bronchiectasis vs not |

32.4 [(27.3–38.4) −42.1] 14.4 (5.9–33.3) 14.8 (10.0–21.5) |

|

| Wyffels [14] | US | 1795 RSV diagnosis Adults ≥18 y: 793 in hospital and 835 outpatient |

IHHR, 77.1 (13.4) IHLR, 71.9 (17.1) OHR, 73.6 (14.5) OLR, 71.1 (12.3) |

Logistic regression prediction of hospitalization | OR, adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, previous evidence of pneumonia, number of conditions, and the number of inpatient and ED visits during the baseline period | COPD vs not Asthma vs not Previous evidence of pneumonia vs not CAD vs not CHF vs not Stroke vs not CKD vs not Stem cell transplant vs not Hematologic malignancy vs not Solid organ transplant vs not |

2.12 (1.49–3.02) 0.79 (.5–1.24) 1.16 (.82–1.65) 2.79 (1.88–4.15) 2.06 (1.4–3.02) 2 (1.02–3.96) 4.37 (2.74–6.98) 2.53 (.21–29.7) 5.17 (2.02–13.2) 2.52 (.88–7.22) |

|

| Branche [17] | Rochester and New York City, NY, US | 469 RSV in hospital 570 RSV in hospital |

69 (59–80) 69 (57–82) |

Incidence rate/100 000 | IRR | 18–49 y, COPD vs not 50–64 y, COPD vs not ≥65 y, COPD vs not 18–49 y, asthma vs not 50–64 y, asthma vs not ≥65 y, asthma vs not 18–49 y, CAD vs not 50–64 y, CAD vs not ≥65 y, CAD vs not 20–39 y, CHF vs not 40–59 y, CHF vs not 60–79 y, CHF vs not ≥80 y, CHF vs not 18–49 y, obesity vs not 50–64 y, obesity vs not ≥65 y, obesity vs not 18–49 y, diabetes vs not 50–64 y, diabetes vs not ≥65 y, diabetes vs not |

Rochester | New York City |

| 3.18 (.99–10.17) 6.35 (2.0–20.11) 13.41 (4.29–41.98) 2.41 (.74–7.86) 2.34 (.74–7.39) 2.52 (.81–7.86) 7.04 (2.19–22.57) 3.74 (1.19–11.78) 6.46 (2.06–20.09) 33.23 (10.14–108.9) 18.78 (5.92–59.55) 7.63 (2.43–23.93) 3.99 (1.29–12.63) 1.71 (.52–5.62) 2.05 (.65–6.53) 3.05 (.97–9.55) 11.16 (3.45–36.13) 3.36 (1.06–10.63) 6.44 (2.06–20.17) |

5.58 (1.72–18.12) 6.3 (3.75–10.58) 3.51 (2.63–4.69) 2.04 (1.02–4.07) 3.6 (2.24–5.79) 2.27 (1.67–3.09) 0.87 (.12–6.33) 4.41 (2.37–8.21) 3.75 (2.82–4.98) 14.45 (1.95–107.0) 13.32 (5.94–29.89) 5.86 (4.07–8.46) 5.4 (3.8–7.67) 1.41 (.72–2.74) 0.83 (.50–1.36) 0.68 (.50–.92) 11.43 (5.27–24.81) 3.58 (2.21–5.79) 2.35 (1.82–3.04) |

|||||||

| Walsh [15] | US | 111 RSV adults: outpatients, 61; hospitalized, 50 | Outpatients, 56.7 (17.1) Hospitalized, 70.5 (14.7) |

Multivariable analysis of severe outcomes, hospitalization | OR adjusted for age and presenting symptoms | Underlying medical conditions vs not | 18.4 (5.1–65.9) | |

| Chatzis [18] | Switzerland | 175 RSV and immunocompromised adults: inpatients, 107; outpatients, 68 | Inpatients, 60.5 (48–70.6) Outpatients, 50.8 (37.3–59.4) |

Multivariable analysis of hospitalization | OR adjusted for immunosuppressive categories, age, bacterial infection, and absolute lymphocyte count | Leukemia/lymphoma vs not Solid tumor vs not |

1.5 (.4–5.2) 5.2 (1.4–20.9) |

|

| Risk factors: living situation | ||||||||

| Holmen [19] | US | 1713 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y | >80, 29% 65–79, 31% 50–64, 25% 18–49, 15% |

Incidence rate/100 000 | IRR adjusted for age | ≥20% vs 0%–4.9% < poverty level 10%–19.9% vs 0%–4.9% < poverty level 5%–9.9% vs 0%–4.9% < poverty level High vs low crowding Medium high vs low crowding Medium low vs low crowding |

2.58 (2.23–2.98) 1.38 (1.20–1.58) 1.12 (.98–1.28) 1.52 (1.33–1.73) 1.14 (.98–1.33) 1.14 (1.01–1.28) |

|

| Prasad [12] | New Zealand | 348 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y | 18–49, n = 64 50–64, n = 93 65–79, n = 118 ≥80, n = 73 |

Incidence rate/100 000 | IRR, adjusted for SES and ethnicity | SES quintile 2 vs 1 SES quintile 3 vs 1 SES quintile 4 vs 1 SES quintile 5 vs 1 |

1.8 (1.4–2.5) 2.1 (1.1–3.0) 2.8 (1.7–3.4) 2.8 (1.7–3.3) |

|

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; IHHR, in-hospital high risk; IHLR, in-hospital low risk; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OHR, outpatient high risk; OLR, outpatient low risk; OR, odds ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SES, socioeconomic status; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

aMean (SD) or median (IQR).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With an Increased Risk of an RSV-Related Lower Respiratory Tract Infection

| Reference | Country | No. of RSV Cases | Population Age, ya | Event Being Compared | Relative Risk Estimate Description | Comparators | Point Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors: demographics | |||||||

| Boattini [24] | Portugal, Italy, Cyprus | 166 RSV Adults aged ≥65 y in hospital |

80.9 (8.7) | Logistic regression prediction of pneumonia | OR, adjusted for age and sex | Older age Male vs female |

1.04 (.99–1.09) 1.81 (.84–3.90) |

| Yoon [30] | South Korea | 118 RSV Adults aged ≥19 y in hospital |

67.77 (13.94) | Logistic regression prediction of RSV pneumonia | OR, adjusted for age, sex, RSV serotype, symptoms, and underlying disease except for hematologic malignancy | 50–64 vs 19–49 y ≥65 vs 19–49 y Males vs females |

0.68 (.22–2.12) 0.70 (.25–1.94) 1.47 (.80–2.71) |

| Azzi [25] | US | 181 HM Adults aged ≥18 y |

59 (18–87) | Logistic regression prediction of LRTI | OR, adjusted for age, sex, type of HM, chemotherapy or corticosteroid use within last month, type of immunodeficiency, smoking | Older age | 1.22 (.96–1.55) |

| Chatzis [18] | Switzerland | 175 RSV and immunocompromised Adults aged ≥18 y |

Inpatients: 60.5 (48–70.6)b Outpatients: 50.8 (37.3–59.4)b |

Multivariable analysis of progression to LRTI and pneumonia | OR, adjusted for immmunosuppressive category, age, bacterial infection, and ALC | Increasing age by 10-y range | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Lehners [26] | Germany | 56 RSV Hematologic inpatients Adults aged ≥18 y |

57.5 (18–78) | Multivariable analysis of LRTI | OR, adjusted for age, allogeneic or autologous transplantation, preexisting respiratory disease, duration of aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, ribavirin treatment | ≥65 vs < 65 y | 1.21 (.26–5.71) |

| Risk factors: Preexisting chronic conditions | |||||||

| Boattini [24] | Portugal, Italy, Cyprus | 166 RSV Adults aged ≥65 y in hospital |

80.9 (8.7) | Logistic regression prediction of pneumonia | OR, adjusted for age and sex | COPD or asthma vs not CKD vs not CHF vs not |

1.05 (.51–2.17) 2.57 (1.12–5.91) 0.52 (.24–1.12) |

| Lehners [26] | Germany | 56 RSV Hematologic inpatients Adults aged ≥18 y |

57.5 (18–78) | Multivariable analysis of LRTI | OR, adjusted for age, allogeneic or autologous transplantation, preexisting respiratory disease, duration of aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, ribavirin treatment | Chronic respiratory condition vs not Allogeneic transplant vs not Autologous transplant vs not |

2.72 (.48–15.49) 1.55 (.31–7.65) 4.61 (.55–38.47) |

| Yoon [30] | South Korea | 118 RSV Adults aged ≥19 y in hospital |

67.77 (13.94) | Logistic regression prediction of RSV pneumonia | OR, adjusted for age, sex, RSV serotype, symptoms, and underlying disease except for hematologic malignancy | Solid cancer vs not CKD vs not Stroke vs not CVD vs not Diabetes vs not |

3.85 (1.65–9.02) 0.89 (.40–1.99) 0.61 (.29–1.28) 1.38 (.69–2.77) 1.0 (.51–1.95) |

| Azzi [25] | US | 181 HM Adults aged ≥18 y |

59 (18–87) | Logistic regression prediction of LRTI | OR, adjusted for age, sex, type of HM, chemotherapy or corticosteroid use within last month, type of immunodeficiency, smoking | Neutropenia vs not Lymphocytopenia vs not Neutropenia/lymphocytopenia vs not Leukemia vs lymphoma Myeloma vs lymphoma |

1.92 (.47–7.82) 1.01 (.26–3.89) 7.17 (1.94–26.53) 1.74 (.59–5.16) 2.45 (.74–8.06) |

| Chatzis [18] | Switzerland | 175 RSV and immunocompromised Adults aged ≥18 y |

Inpatients: 60.5 (48–70.6)b Outpatients: 50.8 (37.3–59.4)b |

Multivariable analysis of progression to LRTI and pneumonia | OR, adjusted for immmunosuppressive category, age, bacterial infection, and ALC | SOT vs not Leukemia/lymphoma vs not Solid tumor vs not |

0.7 (.3–1.5) 1.2 (.4–3.9) 0.8 (.2–2.8) |

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HM, hematologic malignancy; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SOT, solid organ transplant.

aMean (SD) or median (range).

bMedian (IQR).

Table 4.

Factors Associated With an Increased Risk of Severe RSV

| Reference | Country | No. of RSV Cases | Population Age, ya | Event Being Compared | Relative Risk Estimate Description | Comparators | Point Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors: age and sex | |||||||

| Goldman [31] | US | 403 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

69 (57.2–82.1) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and/or in-hospital death) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities | 18–49 vs 50–64 y 65–79 vs 50–64 y ≥80 vs 50–64 y Male vs female |

1.73 (.75–4) 1.76 (.86–3.61) 1.25 (.58–2.70) 1.20 (.7–2.07) |

| Lui [32] | Hong Kong, China | 71 RSV Adults in hospital |

77 (67–83) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (noninvasive ventilation, intensive care, or death within 30 d) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, and presenting symptoms | ≥65 vs 19–49 y Male vs female |

1.04 (.95–1.15) 2.00 (.25–16.2) |

| Bruyndonckx [33] | Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Wales | 144 RSV Adults ≥18 y |

18–59 y, n = 84 60–74 y, n = 41 ≥75 y, n = 19 |

Linear regression prediction of severe outcomes (reconsultation with new or worsened complaints or hospitalization within 28 d of the initial consultation) | OR, adjusted for influenza vaccination, smoking status, days coughing before consultation, and presence of other viruses as well as comorbid conditions | ≥75 vs 18–59 y 60–74 vs 18–59 y ≥75 vs 60–74 y |

1.98 (1.04–4.64) 1.08 (.49–1.64) 1.82 (.98–5.64) |

| Belongia [34] | US | 243 RSV Adults ≥60 y |

72.2 (8.7) | Poisson regression prediction of severe outcomes (acute care hospitalization, ED visit for acute illness, or pneumonia occurring within 28 d after enrollment) | Relative risk, adjusted for high-risk comorbid conditions and previous use of health care services | 65–74 vs 60–64 y ≥75 vs 60–64 y Female vs male |

2.72 (.98–7.57) 3.64 (1.33–9.95) 0.87 (.51–1.47) |

| Lee [21] | Hong Kong, China | 123 RSV Adults ≥18 y in hospital |

78 (15) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (LRT complications causing respiratory insufficiency, evidenced by requirements for bronchodilator and supplemental oxygen) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, time from illness onset, and other major comorbid conditions | Older age | 1.03 (1–1.06) |

| Risk factor: chronic condition | |||||||

| Goldman [31] | US | 403 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

69 (57.2–82.1) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and/or in-hospital death) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities | Respiratory condition vs not Immunodeficiency vs not Cardiac condition vs not Neurologic condition vs not |

1.36 (.8–2.33) 0.89 (.48–1.68) 0.73 (.42–1.27) 0.6 (.3–1.18) |

| Smithgall [35] | US | 192 RSV in hospital Adults ≥65 y |

≥65 y | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (respiratory support with CPAP, ventilation, or ECMO and/or ICU admission or death during the RSV hospitalization) | OR, adjusted for sex, race, age, and other comorbid conditions | Chronic respiratory condition vs not CHF vs not Neurologic condition vs not |

6.1 (2.6–14.4) 3 (1.3–7) 9.4 (2.8–31.4) |

| Lee [21] | Hong Kong, China | 123 RSV Adults ≥18 y in hospital |

78 (15) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (LRT complications causing respiratory insufficiency, evidenced by requirements for bronchodilator and supplemental oxygen) | OR, adjusted for sex, time from illness onset, and other major comorbid conditions | Chronic respiratory condition vs not | 11.73 (4.23–32.49) |

| Park [36] | South Korea | 227 RSV Adults ≥18 y |

65.3 (13.9) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (ICU admission, mechanical ventilation use, in hospital death) | OR, adjusted for other comorbid conditions, RSV symptoms, and fever ≥38 °C | Chronic respiratory condition vs not LRTI vs not |

3.37 (1.43–7.97)b 4.45 (1.8–11.03)b |

| Belongia [34] | US | 243 RSV Adults ≥60 y |

72.2 (8.7) | Poisson regression prediction of severe outcomes (acute care hospitalization, ED visit for acute illness, or pneumonia occurring within 28 d after enrollment) | Relative risk adjusted for high-risk comorbid conditions and previous use of health care services | COPD vs not Asthma vs not Moderate-severe LRTI vs not Immunodeficiency vs not CHF vs not Diabetes vs not |

2.18 (1.27–3.76) 1.39 (.78–2.47) 2.99 (1.83–4.88) 1.81 (.84–3.89) 2.38 (1.33–4.25) 1.44 (.82–2.52) |

| Risk factor: living situation | |||||||

| Goldman [31] | US | 403 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

69 (57.2–82.1) | Logistic regression prediction of severe outcomes (ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and/or in-hospital death) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities | Living in a facility at admission vs living in the community with or without assistance | 6.64 (2.92–15.08) |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; LRT, lower respiratory tract; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

aMean (SD) or median (IQR).

RSV-Related Hospitalization

The risk of RSV-related hospitalization in adults increased with age [11–14] (Table 1), with increased risks in those aged ≥65 years. For example, in New Zealand, Prasad et al [12] estimated an IRR of 31.3 (95% CI, 22.3–44.0) for adults aged ≥80 years vs 18 to 49 years, adjusting for socioeconomic group and ethnicity. In the United States, Wyffels et al [14] estimated increased risks for individuals aged ≥75 years, adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, previous pneumonia, number of health conditions, and number of inpatient and emergency department visits during the baseline period, and reported an OR of 2.53 (95% CI, 1.67–3.84) for those aged ≥85 years vs 18 to 64 years [14].

Branche et al [17] and Prasad et al [16] showed that the IRR for hospitalization was increased in those with comorbid conditions in the United States and New Zealand. IRRs (95% CI) associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma ranged from 2.04 (1.02–4.07) to 13.41 (4.29–41.98); IRRs (95% CI) for coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke or transient ischemic attack, diabetes, or end-stage renal disease ranged from 0.87 (.12–6.33) to 36.45 (14.11–94.16; Table 1) [16, 17]. In the United States, Walsh et al [15] documented an increased risk of hospitalization for any person with a clinically significant comorbid condition (OR, 18.4; 95% CI, 5.1–65.9).

Two studies revealed that immunodeficiency in patients with RSV was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. Wyffels et al [14] reported that the odds of hospitalization was 5 times higher (OR, 5.17; 95% CI, 2.02–13.2) in patients with hematologic malignancies as compared with those without hematologic malignancies. Similarly, Schubert et al [11] revealed increased odds of hospitalization in patients with oncologic illness vs no oncologic illness, which was not statistically significant (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, .86–5.49).

Patient living conditions and sex were shown to affect the risk of RSV hospitalization (Table 1). A recent US study found that poverty and crowded living conditions increased the age-adjusted risk of an RSV hospitalization [19]. In New Zealand, Prasad et al [12] noted that Māori or Pacific ethnicity and low neighborhood socioeconomic status were also independently associated with an increased risk of RSV-associated hospitalization. Walsh et al [15] estimated an increased risk of hospitalization for women vs men (OR, 5.4; 95% CI, 1.2–23.8), controlling for comorbid conditions, age, and presenting symptoms, but Wyffels et al [14] estimated an OR of 1.06 (.8–1.41), controlling for age, comorbidities, and other variables.

RSV-Related Mortality

Overall, the same factors that increased the risk of hospitalization with RSV infection (age, comorbid conditions) increased the risk of dying in the hospital or within 30, 60, or 365 days after hospital admission (Table 2). Tseng et al [20] reported that, after adjusting for comorbid and presenting conditions, the highest mid- to long-term mortality risk (61–365 days after admission) was in patients with RSV aged 75 to 84 years as compared with 60 to 64 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 5.37; 95% CI, 1.32–22.9). Short-term mortality (within 60 days after admission) was highest in hospitalized patients with RSV aged ≥85 years vs 60 to 64 years (aHR, 2.79; 95% CI, .83–9.35) [20].

Table 2.

Factors Associated With an Increased Risk of Death During Hospital Stay and Up to 1 Year After Start of RSV-Associated Hospitalization

| Reference | Country | No. of RSV Cases | Population Age, ya | Event Being Compared (Time Since Admission) | Relative Risk Estimate Description | Comparators | Point Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors: demographics | |||||||

| Schubert [11] | Austria | 103 RSV+ Adults ≥18 y 43.7% in hospital |

57 (40–73)b | Pearson correlation and Spearman ρ for mortality (in hospital) | OR | >65 vs ≤65 y | 1.13 (1.00–12.74) |

| Tseng [20] | US | 664 RSV in hospital Adults ≥60 y |

78.0 (60.0–103.0) | Stepwise multivariable analysis of mortality (by 60 d) | HR, adjusted for age and sex, presenting and in-hospital symptoms, and comorbid conditions | 65–74 vs 60–64 y 75–84 vs 60–64 y ≥85 vs 60–64 y Female vs male |

1.51 (.4–5.64) 2.48 (.73–8.49) 2.79 (.83–9.35) 1.05 (.64–1.7) |

| Tseng [20] | US | 664 RSV in hospital Adults ≥60 y |

78.0 (60.0–103.0) | Stepwise multivariable analysis of mortality (61–365 d) | HR, adjusted for age and sex, presenting and in-hospital symptoms, and comorbid conditions | 65–74 vs 60–64 y 75–84 vs 60–64 y ≥85 vs 60–64 y Female vs male |

3.3 (.75–14.6) 5.37 (1.32–22.9) 5.12 (1.17–22.4) 0.69 (.46–1.05) |

| Lee [21] | Hong Kong, China | 123 RSV Adults ≥18 y in hospital |

78 (15) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (by 30 d) | OR, adjusted for viral RNA concentration and corticosteroid administration | Older age | 1.10 (1.01–1.19) |

| Lee [22] | Hong Kong, China | 607 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 y |

75.1 (16.4) | Stepwise backward regression for prediction of mortality (by 30 d) Stepwise backward regression for prediction of mortality (by 60 d) |

HR, adjusted for sex, major systemic comorbidities, chronic lung disease exacerbations, hospital site, and use of systemic corticosteroids | >75 y >75 y |

2.85 (1.43–5.68) 2.10 (1.18–3.73) |

| Pilie [23] | US | 174 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 |

SCT, 53.78 (11.82) SOT, 55.0 (15.12) No transplant, 62.08 (19.83) |

Logistic regression prediction of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, absolute lymphocyte count on admission, transplant status, chronic lung disease, fever, computed tomography findings, and URTI symptoms | >60 vs ≤60 y Male vs female |

8.41 (1.43–49.52) 3.32 (.61–18.20) |

| Boattini [24] | Portugal, Italy, Cyprus | 166 RSV Adults ≥65 y in hospital |

80.9 (8.7) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age or sex and clinically significant comorbidity or presenting symptoms | Per 1 additional year of age Male vs female |

1.05 (.98–1.12) 3.3 (1.07–10.1) |

| Azzi [25] | US | 181 HM+ RSV Adults ≥18 y |

59 (18–87) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (by 90 d) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, type of HM, chemotherapy or corticosteroid use within last month, type of immunodeficiency, smoking | Per 1 additional year of age Male vs female |

1.35 (.98–1.87) 1.35 (.48–3.85) |

| Lehners [26] | Germany | 56 RSV Hematologic inpatients |

57.5 (18–78) | Multivariable analysis of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age, allogeneic or autologous transplantation, preexisting respiratory disease, duration of aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, ribavirin treatment | ≥65 vs < 65 y | 0.73 (.07–2.87) |

| Boattini [27] | Portugal, Italy, Cyprus | 74 RSV pneumonia Adults ≥18 y |

71.2 (16.9) | Multivariable analysis of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age and sex | Older age Male vs female |

0.97 (.93–1.02) 2.88 (.65–12.68) |

| Risk factors: preexisting chronic conditions | |||||||

| Tseng [20] | US | 664 RSV in hospital Adults ≥60 y |

78.0 (60.0–103.0) | Stepwise multivariable analysis of mortality (by 60 d) | HR, adjusted for age and sex, presenting and in-hospital symptoms, and other comorbid conditions | Lymphoma in 12 mo prior to admission vs not 1 hospital stay in previous 6 mo vs 0 2 hospital stays in previous 6 mo vs 0 |

3.87 (1.32–11.3) 1.14 (.61–2.13) 2.02 (1.15–3.55) |

| Tseng [20] | US | 664 RSV in hospital Adults ≥60 y |

78.0 (60.0–103.0) | Stepwise multivariable analysis of mortality (61–365 d) | HR, adjusted for age and sex, presenting and in-hospital symptoms, and other comorbid conditions | Lymphoma in 12 mo prior to admission vs not ESRD in 12 mo prior to admission vs no ESRD CHF with exacerbation vs no CHF CHF without exacerbation vs no CHF Dementia in 12 mo prior to admission vs no dementia 1 hospital stay in previous 6 m vs 0 2 hospital stays in previous 6 m vs 0 |

3.57 (1.2–10.6) 2.13 (1.08–4.17) 1.86 (1.11–3.13) 0.99 (.59–1.68) 1.86 (1.08–3.19) 1.80 (1.09–2.96) 1.87 (1.09–3.22) |

| Pilie [23] | US | 174 RSV in hospital Adults ≥18 |

SCT, 53.78 (11.82) SOT, 55.0 (15.12) No transplant, 62.08 (19.83) |

Logistic regression prediction of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age (>60, ≤ 60 y), sex, absolute lymphocyte count on admission, transplant status, chronic lung disease, fever, computed tomography findings, and URTI symptoms | Chronic lung disease vs not SCT vs no transplant SOT vs no transplant |

1.15 (.21–6.35) 0.60 (.09–4.12) 0.41 (.05–3.50) |

| Boattini [24] | Portugal, Italy, Cyprus | 166 RSV Adults ≥65 y in hospital |

80.9 (8.7) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, and clinically significant comorbidity or presenting symptoms | Solid neoplasm vs not | 9.06 (2.44–33.54) |

| Azzi [25] | US | 181 RSV with HM Adults ≥18 y |

59 (18–87) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (by 90 d) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, type of HM, chemotherapy or corticosteroid use within last month, type of immunodeficiency, smoking | Neutropenia and lymphocytopenia at RSV diagnosis vs not Neutropenia vs not Lymphocytopenia vs not Leukemia vs lymphoma Myeloma vs lymphoma |

4.32 (1.24–15.0) 2.09 (.39–11.13) 4.09 (.85–19.67) 2.16 (.55–8.58) 0.94 (.19–4.68) |

| Vakil [28] | US | 154 RSV LRTI with HM Adults ≥18 y |

54 (18–79) | Logistic regression prediction of mortality (by 60 d) | OR adjusted for neutropenia or lymphopenia | Allogenic HCT vs not Autologous HCT vs not Neutropenia at RSV diagnosis vs not Lymphopenia at RSV diagnosis vs not |

3.7 (1.2–11.9) 1.6 (.4–6.4) 8.3 (2.8–24.2) 3.7 (1.7–8.2) |

| Schubert [11] | Austria | 103 RSV Adults ≥18 y 43.7% in hospital |

57 (40–73)b | Pearson-correlation and Spearman ρ for mortality (in hospital) | OR | Oncologic illness vs not Dialysis vs not Cardiac illness or not Diabetes or not Respiratory illness |

7.09 (.61–81.9) 0.87 (.81–.94) 1.85 (.16–21.02) 9.11 (.78–106.01) 4.45 (.39–50.95) |

| Lehners [26] | Germany | 56 RSV Hematologic inpatients |

57.5 (18–78) | Multivariable analysis of mortality (in hospital) | OR adjusted for age, allogeneic or autologous transplantation, preexisting respiratory disease, duration of aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, ribavirin treatment | Respiratory condition vs not Allogenic transplant vs not Autologous transplant within 6 mo before RSV disease vs not |

5.21 (.74–36.71) 1.14 (.17–7.62) 0.81 (.09–7.39) |

| Bolton [29] | US | 62 125 patients with RSV, 14 895 patients with RSV with heart failure | Mean: CHF, 74; without CHF, 64 | Multivariable regression analysis of mortality (in hospital) | OR, adjusted for age, sex, race, insurance status, median income by zip code, hospital type and location, and 16 comorbidities | CHF vs not | 1.66 (1.28–2.00) |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; HM, hematologic malignancy; HR, hazard ratio; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SCT, stem cell transplant; SOT, solid organ transplant; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

aMean (SD) or median (range).

bMedian (Q1-Q3).

Although the presence of malignancies or immunosuppression posttransplant was not always significantly associated with hospitalization [11, 14], several studies reported an association between RSV infection with the presence of solid tumors or hematologic malignancies and in-hospital death or death within 365 days after an RSV hospitalization [20, 24, 25, 28]. Tseng et al [20] estimated an increased risk of mortality within 365 days after an RSV hospitalization in persons with dementia in the 12 months before admission as compared with persons without dementia (aHR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.08–3.19).

When age, clinically significant comorbid conditions, and presenting symptoms were controlled for, a study conducted in Portugal, Italy, and Cyprus found that the risk of in-hospital mortality for people aged ≥65 years was higher for men than for women (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.07–10.1) [24]. However, this difference was not identified in 1 US study that controlled for age, sex, lymphocyte count, transplant status, lung conditions, fever, and computed tomography findings [23].

RSV-Related LRTI Including Pneumonia

Risk factors for LRTI including pneumonia are presented in Table 3. Two studies [24, 30] that estimated risks for LRTI by age in adults hospitalized with RSV infection did not show significant effects of older age. Of the 3 studies [18, 25, 26] that presented risks for LRTI by age in adults who were immunocompromised or adults with hematologic malignancies, only Chatzis et al [18] showed a significant increase when including age in their analyses in 10-year ranges. Five studies estimated risks for LRTI according to preexisting chronic conditions [18, 24–26, 30]. Two studies [24, 30] estimated risks for LRTI by preexisting chronic condition in adults hospitalized with RSV infection. Boattini et al [24] noted an increased risk for LRTI in individuals with chronic kidney disease, while Yoon et al [30] did not find such effect but revealed an increased risk for LRTI for individuals with solid cancers vs those without. Of the 3 studies [18, 25, 26] that presented risks for LRTI by age in adults who were immunocompromised or adults with hematologic malignancies, only Azzi et al [25] demonstrated a significant increase for those with neutropenia or lymphocytopenia.

Severe RSV

Severe RSV was a composite endpoint that was variably defined across the studies as combinations of >1 of the following events: hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, emergency department visit, reconsultation with new or worsened symptoms, receipt of mechanical/noninvasive ventilation or vasopressor support, mortality, pneumonia, myocarditis, and encephalitis (Table 4).

Age as a risk factor was assessed in 5 studies controlling for comorbid conditions and presenting symptoms [21, 31–34] (Table 4); increased risks by age were statistically significant only for persons aged >75 years in 2 of these studies [33, 34] (Table 4). Thus, in a group of European countries, Bruyndonckx et al [33] reported an increased risk of severe RSV for individuals aged ≥75 years vs 18 to 59 years (OR for illness deterioration, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.04–4.64) but not when compared with those aged 60 to 74 years. In the United States, Belongia et al [34] noted an increase in severe RSV risk in patients aged ≥75 years vs 60 to 64 years (relative risk, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.33–9.95), with a smaller difference in persons aged 65 to 74 years vs 60 to 64 years (2.72; 0.98–7.57).

Five studies presented estimates of the increased risk of severe RSV in patients with various comorbid conditions [21, 31, 34–36]. Preexisting chronic respiratory conditions were associated with increased risks of severe RSV in 4 studies [21, 31, 35, 36]. Belongia et al [34] reported an increased risk for persons with COPD (statistically significant) but separately for persons with asthma (not statistically significant). Two studies [31, 34] examined the association between immunosuppressive conditions (eg, HIV infection, transplantation, chemotherapy for cancer) and severe RSV: neither study revealed statistical significance (Table 4), although one suggested that immunosuppressive conditions might be a risk factor for severe RSV [34]. Two studies showed that CHF was a significant predictor of severe RSV [34, 35]. Smithgall et al [35] noted a significant increased risk of severe RSV in patients with a neurologic condition, while Goldman et al [31] indicated a nonsignificant protective effect.

Goldman et al [31] demonstrated an increased risk of severe RSV in individuals living in a group facility at hospital admission as compared with community dwellers. Finally, 3 studies that explored sex as a risk factor demonstrated no statistically significant difference in risk of severe RSV between men and women but suggested a possibly increased risk in males [31, 32, 34].

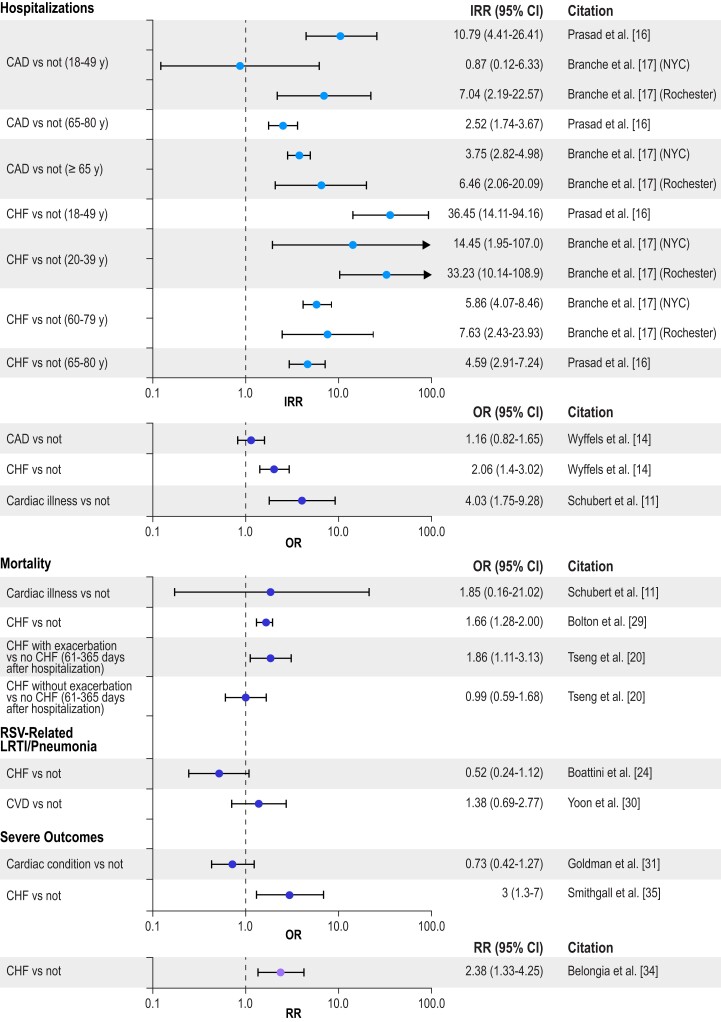

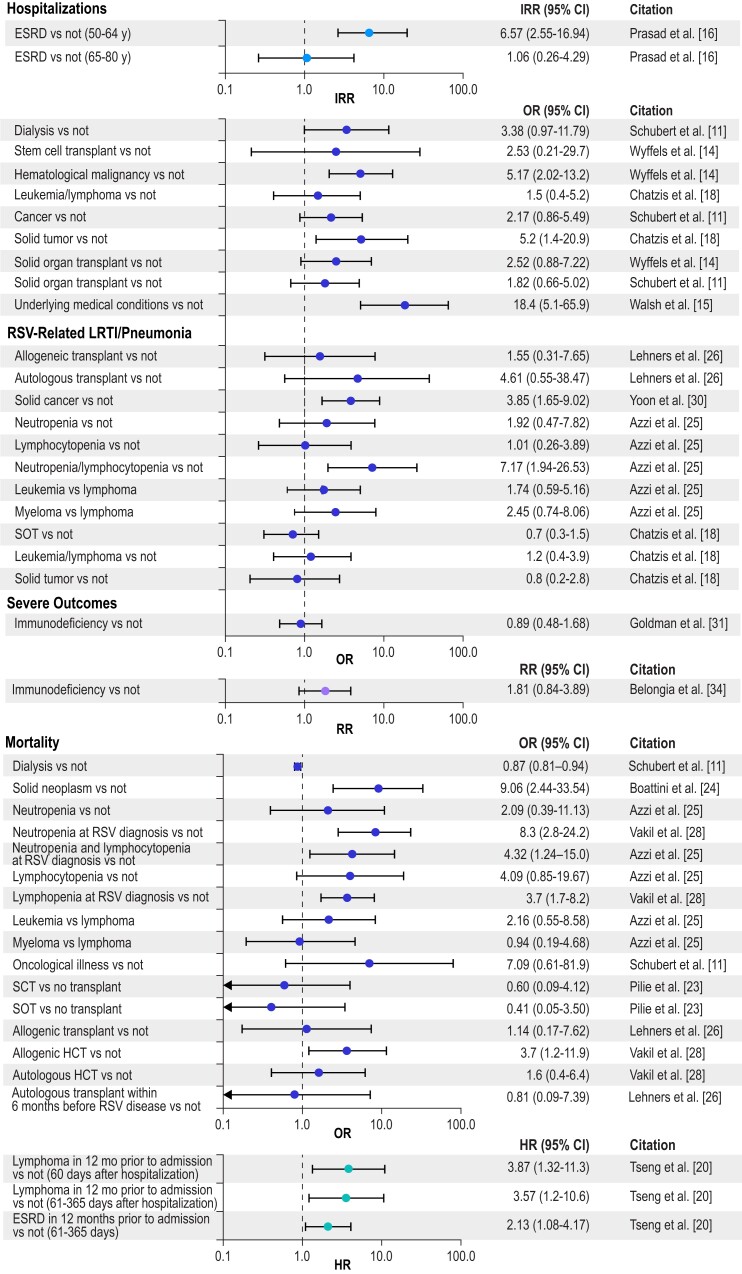

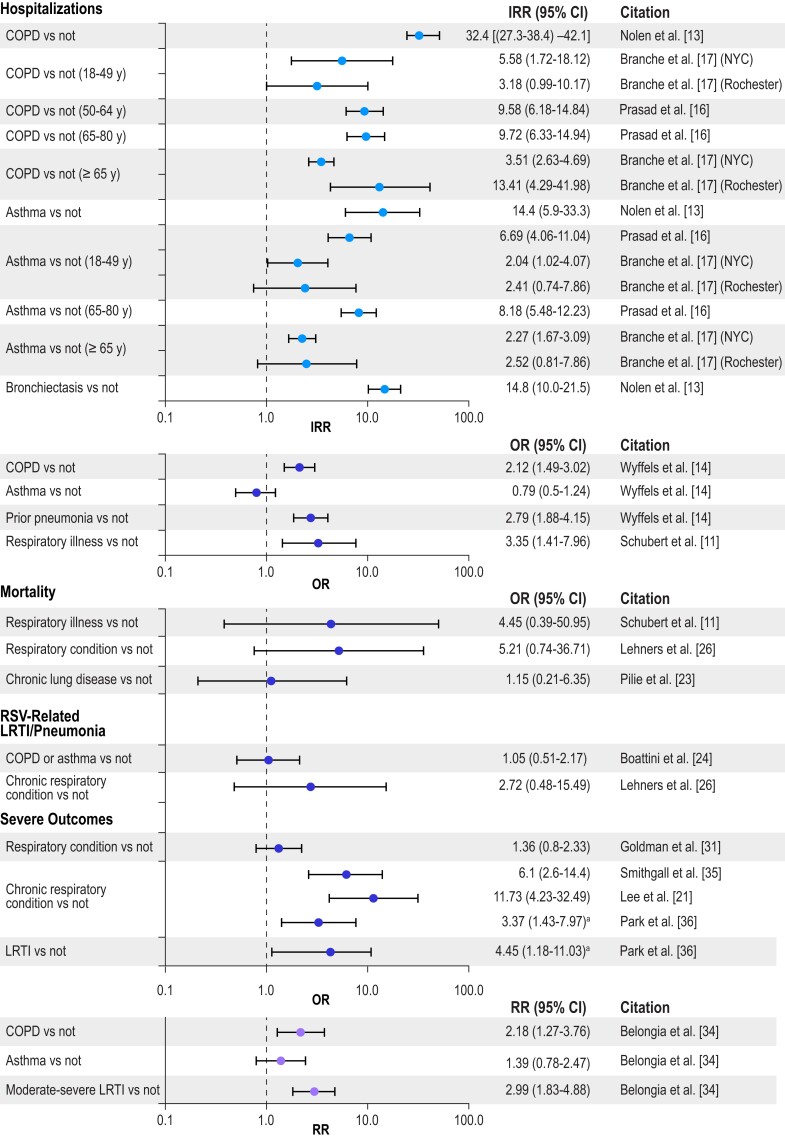

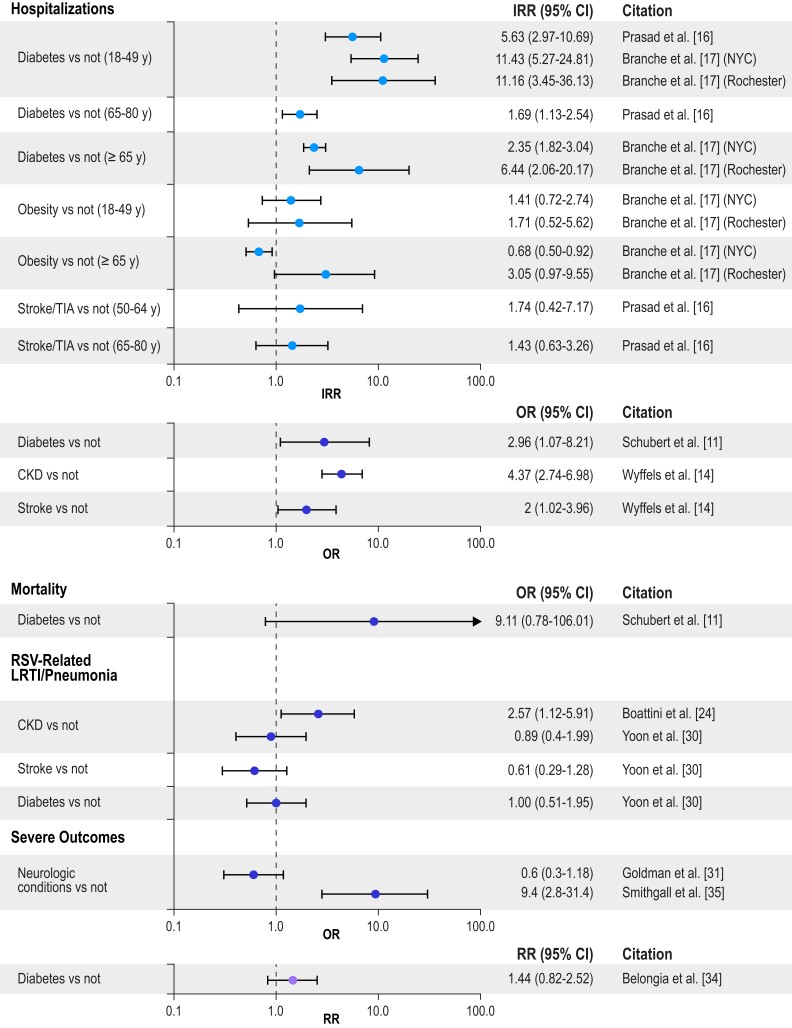

RSV-Related Hospitalization, Mortality, and Severe Infection by Chronic Condition

To illustrate the impact of different chronic conditions on RSV-related hospitalization, mortality, LRTI/pneumonia, and severe RSV (the composite outcome) by age group, Figures 2 to 5 present selected data from Tables 1 to 4 organized into 4 groups: cardiac conditions, respiratory conditions, other conditions (nonimmunocompromised), and immunocompromising conditions. For IRR estimates, only 2 subsets per study are presented—specifically, estimates for the youngest group and one other age group in each study. Figure 2 illustrates that cardiac conditions generally resulted in IRRs >1 for hospitalization in young and older adults [16, 17]; cardiac conditions also generally resulted in ORs >1 in all adults for hospitalization, mortality, LRTI, and severe RSV [11, 14, 29, 35]. Figure 3 presents similar IRRs >1 for hospitalization in young and older adults with respiratory conditions [16, 17] and more consistently ORs >1 in all adults for hospitalization, mortality, LRTI, and severe RSV [11, 13, 14, 23, 25, 26, 31, 35]. Diabetes resulted in IRRs >1 for hospitalizations in young and older adults (Figure 4) [16, 17], and end-stage renal disease in adults (50–64 years) resulted in an IRR >1 for hospitalizations (Figure 5) [16]. The ORs were more mixed for all adults for all the severe RSV infection outcomes of the other nonimmunocompromised conditions. In Figure 5, immunocompromise was reported as an important risk factor for all severe RSV infection outcomes in all adults.

Figure 2.

Risk of severe RSV outcomes by cardiac conditions. IRRs were included only for a subset of the adult age groups presented in the study; all other outcomes included adults aged ≥18 years, and all age groups in the study are included in the tables. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; NYC, New York City; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 5.

Risk of severe RSV outcomes by immunocompromised conditions. IRRs were included only for a subset of the adult age groups presented in the study; all other outcomes included adults aged ≥18 years, and all age groups in the study are included in the tables. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; HR, hazard ratio; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SCT, stem cell transplant; SOT, solid organ transplant.

Figure 3.

Risk of severe RSV outcomes by respiratory conditions. IRRs were included only for a subset of the adult age groups presented in the study; all other outcomes included adults aged ≥18 years, and all age groups in the study are included in the tables. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. aThis number is reported as a β coefficient obtained from logistic regression in Table 2 of the article, but it appears to be an OR based on the counts reported in Table 1 of the article. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; NYC, New York City; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 4.

Risk of severe RSV outcomes by nonimmunocompromised conditions. IRRs were included only for a subset of the adult age groups presented in the study; all other outcomes included adults aged ≥18 years, and all age groups in the study are included in the tables. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. CKD, chronic kidney disease; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; NYC, New York City; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the SLR findings provide strong evidence that identifiable risk factors in adults, such as age, preexisting comorbid conditions (eg, cardiac, pulmonary, and immunocompromising diseases, as well as diabetes and kidney disease), and living conditions, increase the risk of experiencing severe manifestations of RSV infection. While there was less available literature, risk factors were largely similar to those identified for influenza [37]. The magnitude of measured relative risks was not consistent across studies, likely because of substantial differences in methodology and population. The importance of age as a risk factor for severe RSV infection outcomes is likely due to immunosenescence, because of which milder RSV disease may progress to complications such as LRTI or pneumonia, and to the increasing presence of underlying comorbid conditions with age. However, the impact of comorbid conditions independent of age was also illustrated by the increased rate of hospitalization in individuals aged <65 years with comorbid conditions. Where comparable, the frequency of severe outcomes among younger adults with comorbidities was generally similar to that experienced by older adults, suggesting that immunosenescence and chronic conditions are both contributing factors for elevated risk. These findings are consistent with observations in individuals with other respiratory infections, such as community-acquired pneumonia. A recent SLR, for example, reported that the risk of pneumococcal disease “is comparable in healthy older adults and younger adults with immunocompromising conditions” [38].

The studies in our SLR generally showed cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for severe RSV infection outcomes, but again the sizes of the risks were heterogeneous [11, 14, 16, 22]. The heterogeneity in the findings may be explained by differences among studies, such as the populations (eg, age, race/ethnicity), risk factor definitions, evaluated outcomes for which a given risk factor may confer a different risk, and degrees of adjustment for study confounders. Heterogeneity for other risk factors, such as chronic respiratory conditions, may be similarly explained.

Immunocompromised status was significantly associated with a higher risk of mortality from RSV infection, but results for hospitalization and severe in-hospital outcomes were mixed. This could be related to more frequent screening among persons who are immunocompromised and to a lower threshold for hospitalization resulting in identification and hospitalization of more infections associated with mild illness. Among patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and lung transplantation, RSV is a well-established risk factor for severe sequelae, such as graft vs host disease, decline in lung function, and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; thus, physicians of such patients would likely have a heightened interest in identifying such infections [39]. Unlike other adult populations, persons who are immunocompromised are treated with ribavirin for RSV infection [6], which would be another rationale for more frequent testing in this group than other adult populations where only supportive care is available.

For some conditions, such as cardiac disease and diabetes, the relative effect of risk factors varied by age so that risk factors appeared to have a stronger effect among younger patients [16]; this phenomenon is known in epidemiology as effect measure modification. Here, these findings would likely be due to a higher risk in the reference population among older groups, owing to immunosenescence translating into a lower relative risk for the older group with a specific comorbid condition as compared with younger groups. A recent SLR and meta-analysis illustrated that risk of hospitalization from RSV infection associated with older age was comparable to that associated with comorbidities among younger groups (Supplementary Figure 1) [2], suggesting that age and comorbidity should be indications for vaccination, consistent with vaccines for other respiratory infections [40].

Two studies in this review showed an increased risk for RSV hospitalization in adults linked to socioeconomic status or ethnicity in New Zealand [16] and the United States [19]. Similar disparities in the risks of adverse health outcomes in the United States have been shown for other infectious respiratory diseases. A study in Louisville, Kentucky, revealed that a higher concentration of adults hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia came from impoverished areas of the city [41]. A study of US population–based surveillance data found that influenza hospitalization and in-hospital deaths in adults were higher among Black Americans than White Americans [42].

To our knowledge, this is the first SLR focused on collating published quantitative estimates of risk factors for severe RSV disease among adults in high-income countries. A 2017 SLR of RSV epidemiology and outcomes examined disease risk factors, but it was limited to US studies [43]. Our SLR included studies published through 7 March 2022. Unlike the earlier SLR from Colosia et al [43], we were able to identify several recent studies that quantified the impacts of different risk factors for severe outcomes from RSV infection in adults.

The strengths of this SLR are the use of systematic processes that identified and summarized recent studies presenting estimates of the impacts of various risk factors for different manifestations of severe RSV infection, by using standard processes for such reviews and following a protocol submitted to the PROSPERO repository in advance. A limitation is that the studies identified were heterogeneous in design, in definitions used for risk factors and outcomes (especially the risk of severe outcomes), and in the use of laboratory testing for RSV infection. Because of this heterogeneity, we did not conduct a meta-analysis. The risk factors poverty, crowding, and socioeconomic status were ascertained from census-based information from the United States [19] and New Zealand [12] rather than at the individual level: while these results are, in theory, susceptible to the ecological fallacy, they are consistent despite arising from different times and locations; this provides robustness to the findings. In addition, many studies did not report confounding factors, or they did not adjust for all potential confounders. However, almost all studies conducted multivariate analysis or compared age-matched populations, and because the estimates from such heterogeneous studies generally reported the same statistically significant risk factors for the different serious RSV outcomes, this supports the robustness of our findings.

A final limitation of our study is that our search strategy identified studies presenting risk factors published only through 7 March 2022. To determine whether more recent studies were available, the searches were repeated on 13 July 2023. One study author (J. M.) screened the recent publications, and 3 studies were identified that included estimates of quantitative risk factors for outcomes similar to those in our study [44–46]. The results in these studies were generally consistent with those identified in our SLR. Using 2015–2017 surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Respiratory Syncytial Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network, Kujawski et al [45] estimated significantly increased risks of hospitalization with CHF in individuals aged <65 and ≥65 years, with those in the former group having a higher risk ratio for CHF. Using US Medicare data between 2007 and 2019 from individuals with a medically attended diagnosis of RSV, DeMartino et al [44] estimated IRRs for RSV-related complications, defined as pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, CHF, hypoxia/dyspnea, non-RSV lower/upper respiratory tract infection, or chronic respiratory disease up to 6 months after RSV diagnosis. The study showed higher IRRs for those in older age ranges vs 60 to 64 years as well as for those with a previous diagnosis of acute respiratory failure, CHF, hypoxia or dyspnea, pneumonia, non-RSV lower/upper respiratory tract infection, and COPD. Celante et al [46] used Parisian hospital data for 2015 through 2019 to estimate risk factors for in-hospital mortality and invasive mechanical ventilation using multivariable mixed-effect regression models. In-hospital mortality was significantly greater in individuals aged >85 years. The use of invasive mechanical ventilation was greater in those with chronic respiratory failure, chronic heart failure, and coinfection.

CONCLUSIONS

Older age, chronic cardiac and pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, immunocompromising conditions, socioeconomic status, and nursing home residence were risk factors associated with more severe RSV infection outcomes in adults. Identification of risk factors for severe RSV infection outcomes in adults may facilitate appropriate vaccine recommendations for those at risk due to age or comorbidity and encourage vaccine uptake in these adults as RSV vaccines become available.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Annete Njue, Department of Market Access and Outcomes Strategy, RTI Health Solutions, Manchester, UK.

Weyinmi Nuabor, Department of Market Access and Outcomes Strategy, RTI Health Solutions, Manchester, UK.

Matthew Lyall, Department of Market Access and Outcomes Strategy, RTI Health Solutions, Manchester, UK.

Andrea Margulis, Department of Pharmacoepidemiology and Risk Management, RTI Health Solutions, Barcelona, Spain.

Josephine Mauskopf, Department of Health Economics, RTI Health Solutions, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA.

Daniel Curcio, Global Medical Development & Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Vaccines, Pfizer Inc, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

Samantha Kurosky, Global Medical Development & Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Vaccines, Pfizer Inc, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

Bradford D Gessner, Global Medical Development & Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Vaccines, Pfizer Inc, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

Elizabeth Begier, Global Medical Development & Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Vaccines, Pfizer Inc, Collegeville, Pennsylvania, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments . Manuscript formatting and editing support was provided by John Forbes at RTI Health Solutions and funded by Pfizer; no contribution was made to editorial content.

Financial support. This work was supported by a contract to RTI Health Solutions, a business unit of RTI International from Pfizer.

References

- 1. Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13:371–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McLaughlin JM, Khan F, Begier E, Swerdlow DL, Jodar L, Falsey AR. Rates of medically attended RSV among US adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 225:1100–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Y, Kulkarni D, Begier E, et al. Adjusting for case under-ascertainment in estimating RSV hospitalisation burden of older adults in high-income countries: a systematic review and modelling study. Infect Dis Ther 2023; 12(4):1137–49. doi: 10.1007/s40121-023-00792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Food and Drug Administration . FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine. 3 May 2023. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine. Accessed 19 July 2023.

- 5. Pfizer . US FDA approves ABRYSVO, Pfizer's vaccine for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in older adults. 31 May 2023. Available at: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/us-fda-approves-abrysvotm-pfizers-vaccine-prevention. Accessed 19 July 2023.

- 6. Avery L, Hoffmann C, Whalen KM. The use of aerosolized ribavirin in respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in adult immunocompromised patients: a systematic review. Hosp Pharm 2020; 55:224–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Villanueva DH, Arcega V, Rao M. Review of respiratory syncytial virus infection among older adults and transplant recipients. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2022; 9:20499361221091413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. GSK . European Commission authorises GSK's Arexvy, the first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine for older adults. 7 June 2023. Available at: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/european-commission-authorises-gsk-s-arexvy-the-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine-for-older-adults. Accessed 19 July 2023.

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC recommends RSV vaccine for older adults. 29 June 2023. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/s0629-rsv.html. Accessed 19 July 2023.

- 10. World Bank . High income. 2022. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/high-income. Accessed 1 March 2022.

- 11. Schubert L, Steininger J, Lötsch F, et al. Surveillance of respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults, Austria, 2017 to 2019. Sci Rep 2021; 11:8939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prasad N, Newbern EC, Trenholme AA, et al. The health and economic burden of respiratory syncytial virus associated hospitalizations in adults. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0234235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nolen LD, Seeman S, Desnoyers C, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza hospitalizations in Alaska native adults. J Clin Virol 2020; 127:104347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wyffels V, Kariburyo F, Gavart S, Fleischhackl R, Yuce H. A real-world analysis of patient characteristics and predictors of hospitalization among US Medicare beneficiaries with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Adv Ther 2020; 37:1203–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walsh EE, Peterson DR, Kalkanoglu AE, Lee FE, Falsey AR. Viral shedding and immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection in older adults. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:1424–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prasad N, Walker TA, Waite B, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations among adults with chronic medical conditions. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Branche AR, Saiman L, Walsh EE, et al. Incidence of respiratory syncytial virus infection among hospitalized adults, 2017–2020. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 74:1004–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chatzis O, Darbre S, Pasquier J, et al. Burden of severe RSV disease among immunocompromised children and adults: a 10 year retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holmen JE, Kim L, Cikesh B, et al. Relationship between neighborhood census-tract level socioeconomic status and respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations in US adults, 2015–2017. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21:293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tseng HF, Sy LS, Ackerson B, et al. Severe morbidity and short- and mid- to long-term mortality in older adults hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:1298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee N, Chan MC, Lui GC, et al. High viral load and respiratory failure in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1237–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee N, Lui GC, Wong KT, et al. High morbidity and mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1069–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pilie P, Werbel WA, Riddell J 4th, Shu X, Schaubel D, Gregg KS. Adult patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection: impact of solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on outcomes. Transpl Infect Dis 2015; 17:551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boattini M, Almeida A, Christaki E, et al. Severity of RSV infection in southern European elderly patients during two consecutive winter seasons (2017–2018). J Med Virol 2021; 93:5152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Azzi JM, Kyvernitakis A, Shah DP, et al. Leukopenia and lack of ribavirin predict poor outcomes in patients with haematological malignancies and respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:3162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lehners N, Schnitzler P, Geis S, et al. Risk factors and containment of respiratory syncytial virus outbreak in a hematology and transplant unit. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48:1548–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boattini M, Charrier L, Almeida A, et al. Burden of primary influenza and respiratory syncytial virus pneumonia in hospitalized adults: insights from a two-year multi-centre cohort study (2017–2018). Intern Med J 2023; 53:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vakil E, Sheshadri A, Faiz SA, et al. Risk factors for mortality after respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in adults with hematologic malignancies. Transpl Infect Dis 2018; 20:e12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bolton A, Carnahan R, Robinson J. Worse outcomes in older adults with comorbid heart failure complicating respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77:737. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoon JG, Noh JY, Choi WS, et al. Clinical characteristics and disease burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection among hospitalized adults. Sci Rep 2020; 10:12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldman CR, Sieling WD, Alba LR, et al. Severe clinical outcomes among adults hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus infections, New York City, 2017–2019. Public Health Rep 2022; 137:929–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lui G, Wong CK, Chan M, et al. Host inflammatory response is the major marker of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in older adults. J Infect 2021; 83:686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bruyndonckx R, Coenen S, Butler C, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus infection in adult primary care patients: association of age with prevalence, diagnostic features and illness course. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 95:384–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Belongia EA, King JP, Kieke BA, et al. Clinical features, severity, and incidence of RSV illness during 12 consecutive seasons in a community cohort of adults ≥60 years old. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5:ofy316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smithgall M, Maykowski P, Zachariah P, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and resource utilization associated with respiratory syncytial virus in the community and hospital. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2020; 14:247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park SY, Kim T, Jang YR, et al. Factors predicting life-threatening infections with respiratory syncytial virus in adult patients. Infect Dis (Lond) 2017; 49:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, United States, 2021–22 influenza season. MMWR Recommendations Rep 2021; 70:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pelton SI, Shea KM, Bornheimer R, Sato R, Weycker D. Pneumonia in young adults with asthma: impact on subsequent asthma exacerbations. J Asthma Allergy 2019; 12:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Begier E, Ubamadu E, Betancur E, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus sequelae among adults in high income countries: a systematic literature review. Presented at: 12th International RSV Symposium; 29 September–2 October 2022; Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grant LR, Slack MP, Yan Q, et al. The epidemiologic and biologic basis for classifying older age as a high-risk, immunocompromising condition for pneumococcal vaccine policy. Expert Rev Vaccines 2021; 20:691–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. O’Halloran AC, Holstein R, Cummings C, et al. Rates of influenza-associated hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital death by race and ethnicity in the United States from 2009 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2121880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Colosia AD, Yang J, Hillson E, et al. The epidemiology of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus in older adults in the United States: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0182321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. DeMartino JK, Lafeuille M-H, Emond B, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus–related complications and healthcare costs among a Medicare-insured population in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10:ofad203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kujawski SA, Whitaker M, Ritchey MD, et al. Rates of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)–associated hospitalization among adults with congestive heart failure—United States, 2015–2017. PLoS One 2022; 17:e0264890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Celante H, Oubaya N, Fourati S, et al. Prognosis of hospitalised adult patients with respiratory syncytial virus infection: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29:943.e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.