Abstract

Background

Persistent symptoms are reported in patients who survive the initial stage of COVID-19, often referred to as “long COVID” or “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection” (PASC); however, evidence on their incidence is still lacking, and symptoms relevant to pain are yet to be assessed.

Methods

A literature search was performed using the electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and CHINAL and preprint servers MedRχiv and BioRχiv through January 15, 2021. The primary outcome was pain-related symptoms such as headache or myalgia. Secondary outcomes were symptoms relevant to pain (depression or muscle weakness) and symptoms frequently reported (anosmia and dyspnea). Incidence rates of symptoms were pooled using inverse variance methods with a DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model. The source of heterogeneity was explored using meta-regression, with follow-up period, age and sex as covariates.

Results

In total, 38 studies including 19,460 patients were eligible. Eight pain-related symptoms and 26 other symptoms were identified. The highest pooled incidence among pain-related symptoms was chest pain (17%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 11%-24%), followed by headache (16%, 95% CI, 9%-27%), arthralgia (13%, 95% CI, 7%-24%), neuralgia (12%, 95% CI, 3%-38%) and abdominal pain (11%, 95% CI, 7%-16%). The highest pooled incidence among other symptoms was fatigue (44%, 95% CI, 32%-57%), followed by insomnia (27%, 95% CI, 10%-55%), dyspnea (26%, 95% CI, 17%-38%), weakness (25%, 95% CI, 8%-56%) and anosmia (19%, 95% CI, 13%-27%). Substantial heterogeneity was identified (I2, 50–100%). Meta-regression analyses partially accounted for the source of heterogeneity, and yet, 53% of the symptoms remained unexplained.

Conclusions

The current meta-analysis may provide a complete picture of incidence in PASC. It remains unclear, however, whether post-COVID symptoms progress or regress over time or to what extent PASC are associated with age or sex.

Introduction

A broad range of symptoms have been reported to persist beyond the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection [1–6]. These are referred to as “long COVID” [1, 3, 5, 6], “long-hauler” [5] or “Post-COVID-19 syndrome” [4, 5]. The National Institute of Health currently advocates calling these symptoms post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) [7]. This syndrome is sometimes covered sensationally by news media or social networks, but little is known about its etiology, natural history, risk factors or therapeutic interventions. Even more, evidence on its incidence is still lacking.

On a cellular level, the spike protein in the SARS-CoV-2 virus combines with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, invades human cells, and injures multiple organs [8]. Central and peripheral nerve systems are one of the most susceptible targets for SARS-CoV-2 virus (neurotropism) [9]. Frequently reported symptoms range from fatigue, muscle weakness and memory loss to anosmia, ageusia, confusion and headache [1–6, 10]. Some of these symptoms are directly or indirectly related to chronic pain, often worsening quality of life for a long period. As well, a prolonged period of mechanical ventilation in the ICU may cause what is called “post intensive care syndrome” or “ICU-acquired weakness” [9], manifesting as cognitive dysfunction, muscle atrophy, sensory disruption and joint-related pain [8]. These patients will be at elevated risk of developing chronic pain. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 virus causes “cytokine storm”, which aggravates damage in multiple tissues including joints and muscles that possibly triggers pain-related symptoms [8]. A recent study [11] has shown that the prevalence of new-onset headache was substantially higher in COVID-19 survivors compared with those in controlled subjects. Nevertheless, pain in COVID-19 survivors has been underestimated or paid little attention. Treatment of pain in such patients is prone to be of low priority, especially due to overburdened healthcare services or difficulty in consulting with a specialist over the course of the pandemic [12].

As pain clinicians, we believe that understanding and managing pain-related symptoms along with other symptoms will help to improve the quality of life of SARS-CoV-2 survivors. Therefore, we collected currently available evidence and conducted a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies to determine the incidence of pain-related and other symptoms in SARS-CoV-2 convalescents.

Methods

We defined long-term complications as symptoms from which patients suffered for more than 1 month after onset of the first COVID-19 symptoms or after discharge from hospital. A meta-analysis was conducted according to the reporting guidelines for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [13]. The protocol was previously registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021228393).

Search strategy

Three reviewers (HH, SH and TS) searched the electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus and CHINAL and preprint servers MedRχiv and BioRχiv. No language restriction was applied. The last search was done on January 15, 2021. The full search strategy is described in S1 Appendix. Reference lists of all identified articles on “long-covid” were manually searched. All relevant references obtained in the RIS (Research Information Systems) formats were transferred to EndNote X8.2 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and web-platform manager Covidence (Melbourne, Australia).

Eligibility criteria

Studies involving adults (>18 years old) with a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 were included, as were studies that followed up patients for a minimum of 2 weeks after discharge. Studies only focusing on acute symptoms from admission without any mention of long-term symptoms were excluded. Prospective and retrospective cohort studies were also included. Reviews, editorials, meta-analyses, case reports, case series and case-control studies were excluded. Regardless of whether a reported symptom was pain-related or not, studies reporting any relevant “long-covid” symptoms were included. Studies reporting only radiological findings of lung or brain were excluded.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (HH and TS) independently screened titles and abstracts of the obtained references by using Covidence. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SH). Data extraction was performed by five reviewers (HH, TM, HS, SH and TS), and the extracted data were saved in an Excel spreadsheet. Extracted data included study setting, country where study was performed, patient setting, diagnostic criteria of SARS-CoV-2, respiratory support, mean age, percentage of males, follow-up period and information for evaluating study quality. The primary outcome was defined as pain-related symptoms such as headache or myalgia. The secondary outcome was defined as symptoms other than but relevant to pain such as depression or fatigue, or frequently reported symptoms such as anosmia or dyspnea. When data were reported as a graph only, we reproduced numerical data using Plot Digitizer (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net).

Assessment of study quality

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies [14] was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies by the five reviewers. Briefly, the scale consists of three subcategories: selection, comparability and outcome and 9 items. However, we focused on pooled incidence of long-COVID symptoms rather than any treatment effects and all patients exposed to SARS-Cov-2 virus (excluding the non-exposed cohort); therefore, some of the items were impossible to evaluate such as selection of the non-exposed cohort and comparability. Thus, these two items were excluded from the checklist, and study quality was assessed by the rest of the items (S1 Appendix). One point was given for each item, for a maximum score of 6 and a minimum score of 0.

Statistical analysis

At least 3 studies were required per one symptom, due to constraints in performing data synthesis. The proportions of symptoms in an individual study were pooled using inverse variance methods following logit transformation [15]. Between-study variances were quantified using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator [16]. To calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in an individual study, the Clopper-Pearson interval was used. The I2 statistic was used as a measure of heterogeneity (I2 >60%: high heterogeneity; 40–60%: moderate heterogeneity; <40%: low heterogeneity). Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were not performed because our aim in this meta-analysis was to exploratorily collect currently available evidence of overall incidence. Because of possible selection bias, the top 3 most frequent symptoms were ranked in each study, and we aggregate them in an overall ranking.

We explored the source of heterogeneity by meta-regression using a mixed-effects model [17]. We incorporated three covariates (follow-up period, mean age and percentage of males) with fixed effects, and each study as a random effect. R2 was used as a measure of the amount of heterogeneity that could be accounted for by the covariate. Briefly, an index R2 value is defined as the ratio of explained heterogeneity to total heterogeneity, with a range of 0% to 100%. We plotted the logit transformed incidence of each symptom on the Y axis and the covariate on the X axis, along with predicted regression line (bubble plot).

Statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed α = .05. To evaluate small-study effects (publication bias), a funnel plot was depicted and Egger test was performed [18], with significance applied at P < .010. All statistical analyses were conducted using the meta package of R version 4.0.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and RStudio 1.4 (Boston, MA).

Results

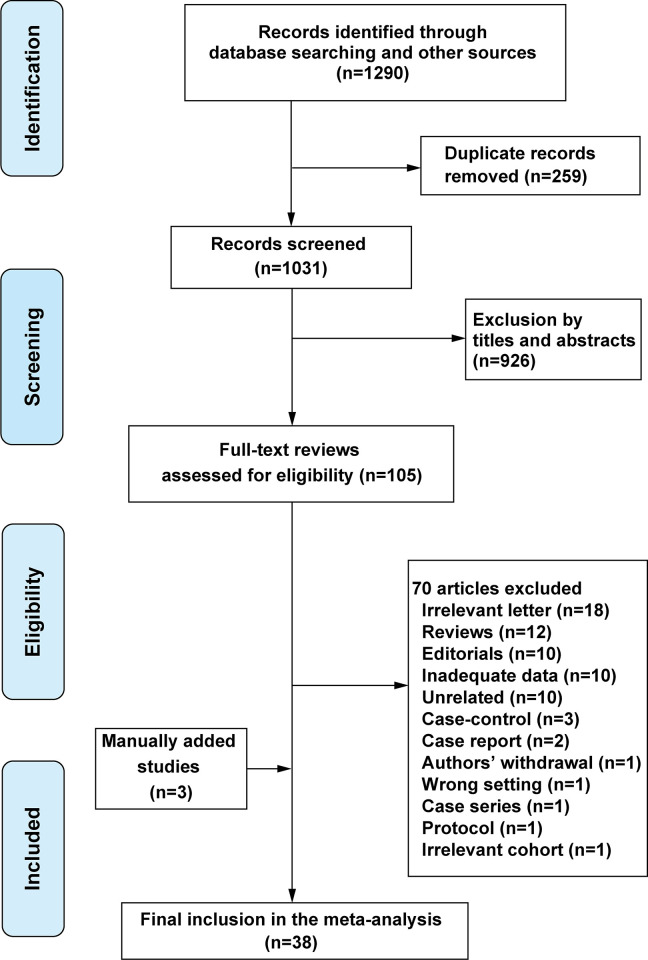

The initial search yielded 1290 citations, of which 105 potentially relevant studies were assessed in full text. Thirty-five studies [19–53] were included. Three studies were manually added according to a reviewer’s suggestion during the revision process of the manuscript [54–56]. Finally, 38 studies comprising 19,460 patients were included in the meta-analysis (Fig 1).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram for literature search, study screening and selection.

All studies were written in English. A summary of the included studies is presented in S1 Table. Studies were reported mainly from Europe, followed by the USA and China. Follow-up duration ranged from 0.5 to 7 months.

The results of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale are shown in S1 Table. Most of the studies (33/38, 87%) scored 5 or 6, and the median score of the 38 studies was 5 (range: 3–6).

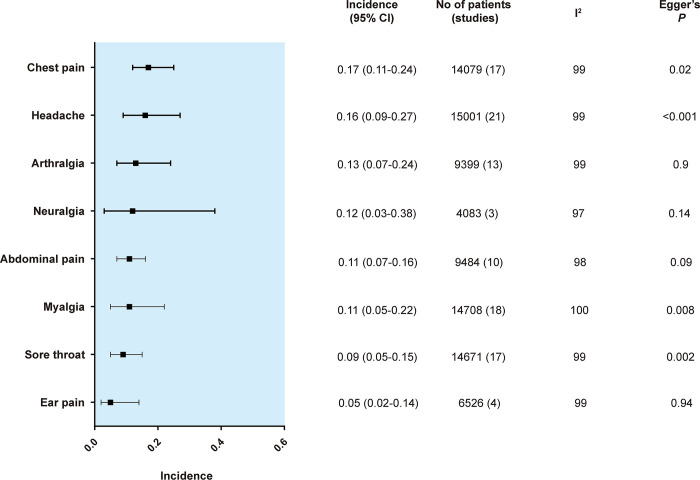

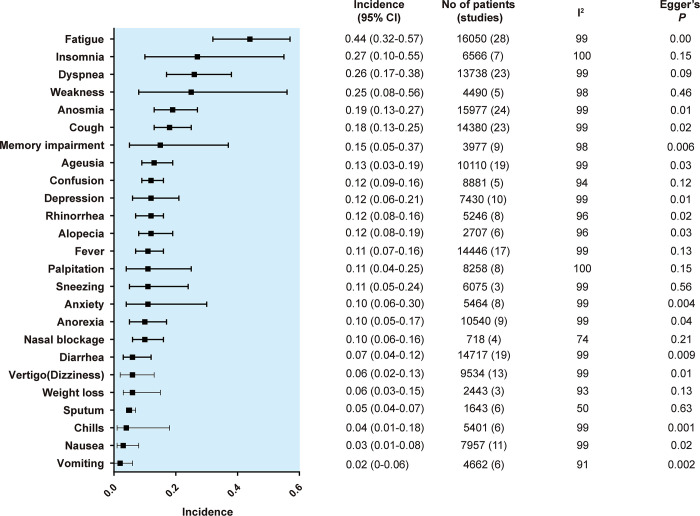

The results of each symptom on the forest plot are shown in S1 Fig. The pooled incidence of each primary and secondary outcome is shown in order of frequency in Figs 2 and 3, respectively.

Fig 2. Summary random effects estimates with 95% confidence interval (CI) from 8 meta-analyses on the incidence of pain-related symptoms.

I2 represents the degree of heterogeneity, and Egger’s P represents publication bias.

Fig 3. Summary random effects estimates with 95% confidence interval (CI) from 8 meta-analyses on the incidence of other symptoms.

I2 represents the degree of heterogeneity, and Egger’s P represents publication bias.

The most frequent symptom among pain-related symptoms was chest pain (17%, 95% CI, 12%-25%), followed by headache (16%, 95% CI, 9%-27%), arthralgia (13%, 95% CI, 7%-24%), neuralgia (12%, 95% CI, 3%-38%) and abdominal pain (11%, 95% CI, 7%-16%). The most frequent symptom in the secondary outcomes was fatigue (45%, 95% CI, 32%-59%), followed by insomnia (26%, 95% CI, 9%-57%), dyspnea (25%, 95% CI, 15%-38%), weakness (25%, 95% CI, 8%-56%) and anosmia (19%, 95% CI, 13%-27%).

Regarding the most frequent symptoms reported in each article, 35 articles were included after excluding articles focusing on a single symptom such as headache [39]. Our results showed that the three most frequent symptoms summarized were fatigue (n = 20), dyspnea (n = 17), cough (n = 13), followed by anosmia (n = 12) and fever (n = 6) (S1 Table).

The results of R2 obtained by meta-regression are shown in the Table 1, and those of the statistical analyses and bubble plots are detailed in S1 Fig.

Table 1. Results of meta-regression to explore the source of heterogeneity.

| No of studies | Heterogeneity (I2) | Amount of heterogeneity accounted for (R2) (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up period | Age | Gender (male) | |||

| Pain-related symptoms | |||||

| Chest pain | 17 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 21 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 13 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neuralgia | 3 | 97 | 100 (+) | 92 (-) | 69 (+) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 18 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sore throat | 17 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ear pain | 4 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other symptoms | |||||

| Fatigue | 28 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 7 | 100 | 44 (+) | 28 (-) | 75 (+) |

| Dyspnea | 23 | 99 | 34 (+) | 0 | 0 |

| Weakness | 5 | 98 | 0 | 64 (-) | 0 |

| Anosmia | 24 | 99 | 0 | 35 (-) | 0 |

| Cough | 23 | 99 | 0 | 42 (-) | 10 (-) |

| Ageusia | 19 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 19 (-) |

| Memory impairment | 9 | 98 | 73 (+) | 5 (+) | 40 (+) |

| Confusion | 5 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 10 | 99 | 55 (-) | 0 | 23 (+) |

| Fever | 17 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhinorrhea | 8 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 99 | 66 (+) | 0 | 67 (+) |

| Palpitation | 8 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sneezing | 3 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alopecia | 6 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 9 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nasal blockage | 4 | 74 | 33 (-) | 0 | 70 (+) |

| Diarrhea | 19 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vertigo (Dizziness) | 13 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 13 | 93 | 23 (-) | 0 | 40 (+) |

| Sputum | 6 | 50 | 65 (-) | 0 | 0 |

| Chills | 6 | 99 | 72 (+) | 0 | 77 (+) |

| Nausea | 11 | 99 | 54 (+) | 1 (-) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 6 | 91 | 7 (+) | 0 | 0 |

R2 represents a measure of the amount of heterogeneity that can be explained by the covariate. Bold numbers indicate that a significant correlation was found between the symptom and the covariate. + or–in parenthesis indicates a positive or negative coefficient in the regression model. Note that for insomnia and follow-up period, for instance, the incidence of insomnia is significantly higher when the follow-up period increases (positive correlation). Note that for ageusia and sex, the incidence of ageusia is significantly higher when the ratio of males in a study population decreases (inverse correlation).

Among pain-related symptoms, significant correlations were identified only for neuralgia: however, only three studies with this symptom were included. For instance, the regression coefficient for follow-up period was 0.39 (logit transformed), which means that every one month of follow-up corresponds to an increase of 1.45 units (45% increase) in prevalence in patients who developed neuralgia after acute COVID-19 infection. For the other symptoms, significant correlations were found for insomnia, dyspnea, weakness, anosmia, cough, ageusia, memory impairment, depression, anxiety, nasal blockage, weight loss, sputum, chills and nausea. Among the symptoms overall, 53% remained unexplained when using the three covariates in the model.

The results of the funnel plots are shown in S1 Fig. For pain-related symptoms, small-study effects as assessed by Egger test were observed for 4 of 8 symptoms. For other symptoms, small-study effects were observed for 15 of 26 symptoms. In total, small-study effects were identified for 56% of the symptoms.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis suggested three main findings. First, pain-related symptoms in COVID-19 survivors were multifarious with an incidence of 5–17%. Second, other symptoms were more multifaceted with incidences ranging from 2% to 45%. Third, every symptom varied extensively in its incidence, and the three major covariates (follow-up, age and sex) could not explain the heterogeneity.

Among pain-related symptoms, the highest pooled incidence was chest pain (17%), followed by headache (16%), arthralgia (13%), neuralgia (12%) and abdominal pain (11%). Chest pain is also referred to as “lung burn”, which is considered to be a result of lung injury by SARS-CoV-2 infection [6]. Alternatively, other researchers pointed out that chest pain may result from pericarditis caused by infection [29]. Headache is one of the most common central nervous system symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [57, 58]. It can persist over the period of the initial infection [59], or it can develop as a new-onset form during healing [11]. Proposed mechanisms include direct invasion of trigeminal nerve endings by SARS-CoV-2 via disruption of the brain-blood barrier, trigeminovascular activation via involvement of endothelial cells with ACE2 expression, or triggering of perivascular trigeminal nerve endings by release of cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators [59].

Among other symptoms, almost half of the patients developed fatigue. Generally, fatigue is considered to be closely related to chronic pain. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) [60] or fibromyalgia [61] are good examples. A recent report suggested that there are similarities and overlap in pathology between long COVID symptoms and ME/CFS [4, 60]. As fatigue is often refractory to a single approach, holistic management such as rehabilitation or cognitive behavioral therapy is required [6]. Weakness, often accompanied by myalgia and arthralgia, is a musculoskeletal manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection [62]. Muscle fiber atrophy, extensive use of corticosteroids, prolonged mechanical ventilation or systematic inflammation may be the causes of weakness [62].

From the results of the meta-regression, the incidence of neuralgia was significantly associated with follow-up period, age or sex to some extent; however, only 3 studies were included with this symptom. Therefore, it is difficult to consider this result to be valid. As another example, an inverse association was found between the incidence of weakness and age, but we could not explain this well. In any case, we are aware that these statistical models are preliminary and exploratory, and 53% of symptoms were not explainable despite three typical covariates being incorporated into the model. Symptoms of long COVID are reported to be on-and-off, cyclic or multiphasic [5], which is why the linear regression model did not fit well.

During the course of our study, a similar meta-analysis related with pain were published [63]. Although this might weaken the originality of our study, in the publication, the most frequently reported pain-related symptoms and their incidence were comparable with those reported in our studies. For instance, chest pain is the most reported symptoms, and its incidence ranges between 7.8–23.6%.

This study has several limitations. First, considerable heterogeneity was found in most of the symptoms, and meta-regression could not explain it in just over half of the symptoms. Possible reasons may be the following: in the light of the nature of observational studies, the subjects are not homogenous. The current study includes reports from a wide range of countries; thus, the definition and diagnostic criteria of symptoms might vary from study to study. The majority of data were collected via telephone interview or online survey. A face-to-face visit was not always possible during the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore, recall bias might possibly have occurred. Second, pain-related symptoms were less frequent compared with other symptoms. Selection bias in each study might be possible because pain-related symptoms might be underdiagnosed. Third, the current study did not include “brain fog”, “covid toe” or “post-exertional malaise”, which are widely known as post-COVID symptoms [2, 6, 26, 62], because these symptoms did not fulfill our inclusion criteria of at least three studies being required for data synthesis. However, we will be able to update this review if more reports are published on these symptoms in the future. Fourth, publication bias was identified for 56% of all symptoms. This suggested that the point estimates of the incidence of symptoms in our study might have been overestimated or underestimated. Lastly, studies performed in different geographical regions might be a potential factor contributing to the heterogeneity, which was suggested in a recent meta-analysis [64].

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis highlighted the incidence of pain-related and other typical symptoms in patients with PASC. It remains uncertain whether post-COVID symptoms progress or regress over time and to what extent PASC are associated with age or sex.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the article and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by International University of Health and Welfare with funding for TS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lancet The. Facing up to long COVID. Lancet. 2020; 396(10266): 1861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32662-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yelin D, Wirtheim E, Vetter P, Kalil AC, Bruchfeld J, Runold M, et al. Long-term consequences of COVID-19: research needs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 20(10): 1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30701-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahase E. Covid-19: What do we know about "long covid"? BMJ. 2020; 370: m2815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long COVID: let patients help define long-lasting COVID symptoms. Nature. 2020; 586(7828): 170. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02796-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Soc Sci Med. 2021; 268: 113426. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelson M, Nel J, Blumberg L, Madhi SA, Dryden M, Stevens W, et al. Long-COVID: An evolving problem with an extensive impact. S Afr Med J. 2020; 111(1): 10–12. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v111i11.15433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. NIH launches new initiative to study “Long COVID”. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/nih-launches-new-initiative-study-long-covid. Accessed April 18, 2021.

- 8.Su S, Cui H, Wang T, Shen X, Ma C. Pain: A potential new label of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87: 159–160. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp HI, Corner E, Colvin LA. Chronic pain after COVID-19: implications for rehabilitation. Brit J Anaesth. 2020; 125(4): 436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott HC. Outcomes for patients following hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021; 325(15): 1511–1512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soares FHC, Kubota GT, Fernandes AM, Hojo B, Couras C, Costa BV, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of new-onset pain in COVID-19 survivors, a controlled study. Eur J Pain. 2021: doi: 10.1002/ejp.1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lokugamage AU, Bowen MA, Blair J. Long covid: doctors must assess and investigate patients properly. BMJ. 2020; 371: m4583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PRISMA: transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. http://www.prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/ Accessed April 28, 2021.

- 14.Wells GA, Shea B,O’Connell D, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale(NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed April 18, 2021.

- 15.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013; 67(11): 974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7(3): 177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JT, Rothstein HR, eds. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997; 315(7109): 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, Morley AJ, Viner J, Attwood M, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: Results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2020; 76(4): 399–401. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boscolo-Rizzo P, Borsetto D, Fabbris C, Spinato G, Frezza D, Menegaldo A, et al. Evolution of altered sense of smell or taste in patients with mildly symptomatic COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 146(8): 729–732. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020; 324(6): 603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 27(2): 258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng D, Calderwood C, Skyllberg E, Ainley A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of adult patients admitted with COVID-19 in East London: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021; 8(1): e000813. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiesa-Estomba CM, Lechien JR, Radulesco T, Michel J, Sowerby LJ, Hopkins C, et al. Patterns of smell recovery in 751 patients affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Neurol. 2020; 27(11): 2318–2321. doi: 10.1111/ene.14440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cirulli ET, Schiabor Barrett KM, Riffle S, Bolze A, Neveux I, Dabe S, et al. Long-term COVID-19 symptoms in a large unselected population. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.10.07. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.07.20208702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re’em Y, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.12.24. doi: 10.1101/2020.12.24.20248802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis A, Wamil M, Kapur S, Alberts J, Badley AD, Deckeret GA, et al. Multi-organ impairment in low-risk individuals with long COVID. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.10.14.20212555. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.14.20212555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eiros R, Barreiro-Perez M, Martin-Garcia A, Almeida J, Villacorta E, Perez-Pons A, et al. Pericarditis and myocarditis long after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a cross-sectional descriptive study in health-care workers. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.07.12. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.12.20151316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, Delbressine JM, Vaes AW, Meys R, Machado FVC, et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020; 6(4): 00542–2020. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2): 1013–1022. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021; 397(10270): 220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein H, Asseo K, Karni N, Benjamini Y, Nir-Paz R, Muszkat M, et al. Onset, duration, and persistence of taste and smell changes and other COVID-19 symptoms: longitudinal study in Israeli patients. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.09.25.20201343. doi: 10.1101/2020.09.25.20201343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovato A, Galletti C, Galletti B, de Filippis C. Clinical characteristics associated with persistent olfactory and taste alterations in COVID-19: a preliminary report on 121 patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020; 41(5): 102548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, Brown JS, Denneny EK, Hare SS, et al. ’Long-COVID’: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2020. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moradian ST, Parandeh A, Khalili R, Karimi L. Delayed symptoms in patients recovered from COVID-19. Iran J Public Health. 2020; 49(11): 2120–2127. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49i11.4729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandão Neto D, Fornazieri MA, Dib C, Di Francesco RC, Doty RL, Voegels RL, et al. Chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19: prevalences, recovery rates, and clinical associations on a large Brazilian sample. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021; 164(3): 512–518. doi: 10.1177/0194599820954825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, Danielsen ME, Á Steig B, Gaini S, et al. Long COVID in the Faroe Islands:-a longitudinal study among non-hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020: ciaa1792. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilotto A, Cristillo V, Piccinelli SC, Zoppi N, Bonzi G, Sattin D, et al. COVID-19 severity impacts on long-term neurological manifestation after hospitalisation. medRxiv. 2021: 2020.12.27. doi: 10.1101/2020.12.27.20248903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poncet-Megemont L, Paris P, Tronchere A, Salazard JP, Pereira B, Dallel R, et al. High prevalence of headaches during Covid-19 infection: a retrospective cohort study. Headache. 2020; 60(10): 2578–2582. doi: 10.1111/head.13923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahmani H, Davoudi-Monfared E, Nourian A, Nabiee M, Sadeghi S, Khalili H, et al. Comparing outcomes of hospitalized patients with moderate and severe COVID-19 following treatment with hydroxychloroquine plus atazanavir/ritonavir. Daru. 2020; 28(2): 625–634. doi: 10.1007/s40199-020-00369-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salmon-Ceron D, Slama D, De Broucker T, Karmochkine M, Pavie J, Sorbets E, et al. Clinical, virological and imaging profile in patients with prolonged forms of COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. J Infect. 2020; 82(2): e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savarraj JPJ, Burkett AB, Hinds SN, Paz AS, Assing A, Juneja S, et al. Three-month outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.10.16. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.16.20211029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stavem K, Ghanima W, Olsen MK, Gilboe HM, Einvik G. Persistent symptoms 1.5–6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study. Thorax. 2020; thoraxjnl-2020–216377. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of Long-COVID: analysis of COVID cases and their symptoms collected by the Covid Symptoms Study App. medRxiv. 2020: 2020.10.19.20214494. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.19.20214494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(30): 993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomasoni D, Bai F, Castoldi R, Barbanotti D, Falcinella C, Mulè G, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms after virological clearance of COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Milan, Italy. J Med Virol. 2021; 93(2): 1175–1179. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, Dunne J, Mooney A, Gaffney F, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One. 2020; 15(11): e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.024078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Xu H, Jiang H, Wang L, Lu C, Wei X, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of discharged coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a prospective cohort study. QJM. 2020; 113(9): 657–665. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weerahandi H, Hochman KA, Simon E, Blaum C, Chodosh J, Duan E, et al. Post-discharge health status and symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021; 36(3): 738–745. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06338-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu C, Hu X, Song J, Yang D, Xu J, Cheng K, et al. Mental health status and related influencing factors of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China. Clin Transl Med. 2020; 10(2): e52. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiong Q, Xu M, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, et al. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021; 27(1): 89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan N, Wang W, Gao Y, Zhou J, Ye J, Xu Z, et al. Medium term follow-up of 337 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Shelter Hospital in Wuhan, China. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020; 7: 373. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao YM, Shang YM, Song WB, Li QQ, Xie H, Xu QF, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 25: 100463. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174(4): 576–578. doi: 10.7326/M20-5661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Le Bot A, Hamon A, Gouze H, et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect 2020; 81(6): e4–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moreno-Pérez O, Merino E, Leon-Ramirez JM, Andres M, Ramos JM, Arenas-Jiménez J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Incidence and risk factors: A Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect 2021; 82(3): 378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berger JR. COVID-19 and the nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020; 26(2): 143–148. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00840-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niazkar HR, Zibaee B, Nasimi A, Bahri N. The neurological manifestations of COVID-19: a review article. Neurol Sci. 2020; 41(7): 1667–1671. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04486-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bolay H, Gül A, Baykan B. COVID-19 is a real headache! Headache. 2020; 60(7): 1415–1421. doi: 10.1111/head.13856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman KJ, Murovska M, Pheby DFH, Zalewski P. Our evolving understanding of ME/CFS. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021; 57(3): 200. doi: 10.3390/medicina57030200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bair MJ, Krebs EE. Fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 172(5): ITC33–ITC48. doi: 10.7326/aitc202003030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Disser NP, De Micheli AJ, Schonk MM, Konnaris MA, Piacentini AN, Edon DL, et al. Musculoskeletal consequences of COVID-19. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020; 102(14): 1197–1204. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.20.00847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Navarro-Santana M, Plaza-Manzano G, Palacios-Cena D, Arendt-Nielsen L. Time course prevalence of post-COVID pain symptoms of musculoskeletal origin in patients who had survived severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2022;163(7):1220–1231. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alkodaymi MS, Omrani OA, Fawzy NA, et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022;28(5):657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]