Abstract

Background Panel management is essential for residents to learn, yet challenging to teach. To our knowledge, prior literature has not described curricula utilizing a financially incentivized competition to improve resident primary care metrics.

Objective We developed a panel management curriculum, including a financially incentivized quality competition, to improve resident performance on quality metrics.

Methods We developed a cancer screening and diabetes metric quality competition for internal medicine residents at Vanderbilt University Medical Center for their primary care clinics for the 2020-2021 (pilot) and 2021-2022 academic years. Residents received several educational tools, including a 1-hour introduction to the health maintenance dashboard within the electronic medical record (EMR) and instructions on how to access the quality dashboard outside the EMR, and were encouraged to discuss panel management with preceptors. Chief residents distributed measures to trainees 3 times annually, so residents were aware of their competition ranking. Residents’ composite metrics at year end were compared to baseline to determine top performers. The top 15 performers received $100 gift cards as incentives. We also assessed the curriculum’s impact on the residents’ metrics in aggregate.

Results At curriculum completion, residents (n=100) demonstrated an average improvement of 1.9% from baseline composite metrics for the percent of patients receiving screening. In aggregate, residents improved in every measure except HbA1c testing. Breast cancer screening had the largest improvement from 69.5% (1518 of 2183) to 75.6% (1646 of 2178) of all patients receiving recommended screening.

Conclusions The curriculum resulted in more patients receiving recommended cancer and diabetes screenings.

Introduction

Panel management is an essential skill for internal medicine (IM) residents and involves proactively identifying patients requiring routine screenings and patient outreach to achieve this goal.1 Panel management benefits patients, institutions, and payors, but is difficult to teach.2-4 Competition has been shown to enhance learning and motivation and engage health care trainees in learning skills.5-7 While prior studies have used financial incentives for residents to improve quality measures, none have, to our knowledge, used this method to teach panel management skills.8,9

We developed a panel management curriculum with a financially incentivized quality metric competition tracking IM residents’ performance of cancer screening and diabetes measures. We herein report the curriculum’s feasibility and effects on quality measures.

Methods

Setting and Participants

With support from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) IM program and department leadership, chief residents led this quality metric competition in 2020-2021 (pilot) and 2021-2022. The VUMC IM residency program consists of approximately 40 residents per year and has a Veteran Affairs and a Vanderbilt primary care clinic. All IM residents were included in the quality competition. We describe the 2021-2022 curriculum for residents with Vanderbilt primary care clinics whose primary care patient panel data was used in data analysis via the Epic electronic medical record (EMR). The patient population included resident primary care physician (PCP) patients.

Interventions

Chief residents announced the competition to IM residents at the beginning of each academic year. The 2020-2021 academic year curriculum tracked 3 cancer metrics and expanded in 2021-2022 to include 3 diabetes metrics. Novel to the intervention, residents received the following educational tools (provided as online supplementary data):

One-hour, mandatory didactic session on the preventive care dashboard in the EMR and how to access the quality metrics dashboard maintained outside the EMR, which is updated in real-time and available at any time to residents

Dashboard summary guide

Guide to review their patient panel, patients’ eligibility for screening, and how to bulk message patients through the EMR patient portal

Sample scripts for patient outreach

Approximately every 2 to 3 months, chief residents sent emails encouraging residents to discuss with their preceptors how to improve their metrics and consider barriers to improvement.

Measures for the pilot were cancer screening (colorectal, cervical, breast). In the second year, the competition also included diabetes measures (A1c testing frequency, nephropathy screening, and eye examinations). Measures were defined as the number of eligible patients who had received the recommended screening metric divided by all patients eligible for the specific measure based on a diagnosis or gender or age seen in a primary care department within the 24 months prior to the data download. Patients were excluded from the metric if they did not qualify for screening. Cancer screening measures were based on United States Preventive Services Taskforce recommendations. The diabetes measures were calculated for all patients ages 18 to 75 with an active diabetes diagnosis in the EMR based on ICD codes. The measure “Diabetes Hemoglobin A1c” (HbA1c) testing was defined as a completed HbA1c test within 12 months. “Diabetes Eye Examination” was defined as a completed diabetic dilated eye examination or an in-clinic RetinaVue screen within 12 months. “Diabetes Nephropathy” measure was defined as nephropathy screening or evidence of nephropathy within 12 months. A resident’s composite metric was calculated as the average of all metrics.

At regular intervals during the 2021-2022 academic year (baseline, mid-year, and year-end), a data management specialist downloaded residents’ performance data along with peer and institutional data and institutional goals. Chief residents distributed the data to IM residents whose names were not de-identified in order to promote competition. “Most improved” was determined by the greatest change in composite at baseline to composite at competition completion. At conclusion, $100 gift card prizes were awarded to the 2 most improved and 3 with highest composite metric per postgraduate year in training (PGY-1-3). The division of general internal medicine (DGIM) provided $1,500 to purchase gift cards for 15 unique winners. Additionally, each metric was analyzed using aggregate data from all residents to assess effectiveness of the competition.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center IRB approved this study for IRB exemption.

Results

The 2021-2022 academic year competition included 100 IM residents equally divided across PGY level. The average resident panel size was 159 patients with a total number of 15 910 patients with resident PCPs. Selected patient demographics are reported in the Table. During the competition period, residents saw 7143 unique patients in 10 629 visits. Of these visits, 10.5% (1119 of 10 629) had a diabetes diagnosis.

Table.

Demographics of an Average Resident Patient Panel

| Demographics | Average Resident Panel |

| Number of patients | 82.4 |

| Age, mean | 47 |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (45) |

| Patients with diabetes, n (%) | 12 (14.6) |

| Patients eligible for breast cancer screening, n (%) | 16.6 (20.2) |

| Patients eligible for cervical cancer screening, n (%) | 36 (43.9) |

| Patients eligible for colorectal cancer screening, n (%) | 31.3 (38.2) |

| Race (%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.3 |

| Asian Indian | 0.5 |

| Black or African American | 21.1 |

| Chinese | 0.2 |

| Filipino | 0.2 |

| Guamanian or Chamorro | <0.1 |

| Japanese | 0.1 |

| Korean | 0.1 |

| Native Hawaiian | <0.1 |

| Othera | 13.4 |

| Other Asian | 2.4 |

| Other Pacific Islander | <0.1 |

| Vietnamese | 0.1 |

| White | 61.4 |

Race category other includes “Null”, “Decline to Answer”, “Other”, and “Unknown” in electronic medical record.

Note: Patient panel was defined as any patient seen within 24 months at time of data download and included in the competition data set.

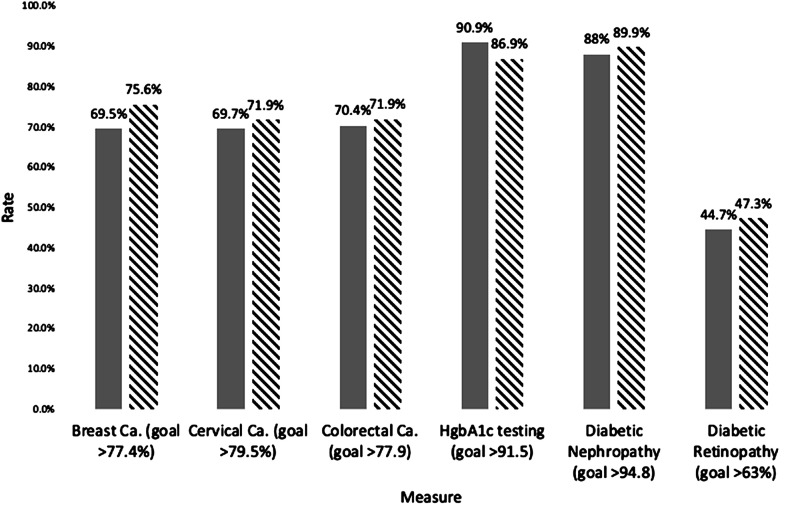

Aggregate data during the pilot year (n=98 residents) demonstrated an increase from 68.7% (1294 of 1885) to 70.9% (1315 of 1856) for breast cancer, 63.9% (2212 of 3463) to 70.3% (2438 of 3467) for cervical cancer and 68.3% (2395 of 3506) to 72.3% (2521 of 3487) for colorectal cancer (online supplementary data). For competition 2021-2022, residents aggregate metrics improved from baseline in every measure except for HbA1c testing but did not meet the institutional goal for any measure (Figure). The margin between current rate and goal decreased on average by 1.7%. There was, on average, a 1.9% increase in the composite measure for all residents. Sixty-three percent (63 of 100) of residents demonstrated improvement in their composite measure. Fifteen residents received awards for a total of $1,500.

Figure.

Residents’ Aggregate Measure Rate at Baseline and Competition Completion

Note: Comparison of baseline and competition completion rates across all residents for all measures 2021-2022. Patients were included if they were eligible for the given metric and had been seen within the 24 months prior to the data being downloaded. The gray column is baseline aggregate resident rates and dashed column is aggregate resident rate at competition completion. Institutional goal is listed below the respective measure.

Balancing measures were not assessed; however, residents directly outreached to patients by phone calls or patient portal messaging, limiting workload on clinic staff. This required approximately 4.5 hours per month from a data management specialist who was housed within the DGIM and 4.5 hours per month by the chief resident.

Discussion

We developed a panel management curriculum, including a financially incentivized quality metric competition, educational tools, and regular data review for IM residents, and documented an improvement in residents’ performance across multiple institutional measures. Competition and financial incentives have been used in health care settings, but to our knowledge have not been used in panel management education.8 The percent improvement in the second year was smaller than in the pilot year, likely because residents’ baseline rates were higher. We do not know if the percent change is statistically significant. It is unclear why the HbA1c testing went down in isolation. Residents were encouraged to meet with preceptors to discuss potential barriers and options to improve measures (eg, direct outreach). There was variability among preceptors as to the degree to which this was done, and formalizing the preceptor role in panel management is an opportunity moving forward. We cannot confirm the improvement was due to the panel management curriculum, including the additional education provided and financial incentives, or routine improvements in care. Additionally, our resident clinic patient population is largely insured and has few financial barriers to completing quality measures, thus limiting our model’s generalizability.

Nonetheless, a similar model could easily be utilized at other residency programs to incentivize and facilitate panel management, especially for programs that do not address these topics routinely but would like to start. For the 2022-2023 academic year, the decision was made to not run the competition as the residents’ baseline rates were high, possibly due to the effects of the 2 years of competition. We felt that 2 years of an incentive program had ingrained these behaviors into residents’ workflow, removing the need for the competition though the remainder of the educational curriculum continued. Additionally, patient outreach was shifted to care coordinators as part of population health efforts starting 2022-2023.

Conclusions

The VUMC panel management curriculum was associated with an improvement in patient cancer and diabetes screening among IM residents.

Supplementary Material

Editor’s Note

The online version of this article contains tools and further data from the study.

Author Notes

Funding: Funding provided by the Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Conflict of interest: Silas P. Trumbo, MD purchased stock in a company that makes Cologuard, a colon cancer screening tool.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency) February . 2020;3 Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/common-program-requirements/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chase SM, Miller WL, Shaw E, Looney A, Crabtree BF. Meeting the challenge of practice quality improvement: a study of seven family medicine residency training practices. Acad Med . 2011;86(12):1583–1589. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823674fa. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernald DH, Deaner N, O’Neill C, Jortberg BT, degruy FV, 3rd,, Dickinson WP. Overcoming early barriers to PCMH practice improvement in family medicine residents. Fam Med . 2011;43(7):503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadley Strout EK, Landrey AR, MacLean CD, Sobel HG. Internal medicine resident experiences with a 5-month ambulatory panel management curriculum. J Grad Med Educ . 2018;10(5):559–565. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00172.1. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorbanev I, Agudelo-Londoño S, González RA, et al. A systematic review of serious games in medical education: quality of evidence and pedagogical strategy. Med Educ Online . 2018;23(1):1438718. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1438718. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cagiltay NE, Ozcelik E, Ozcelik NS. The effect of competition on learning in games. Computer Educ . 2015;87:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.001. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokadam NA, Lee R, Vaporciyan AA, et al. Gamification in thoracic surgical education: using competition to fuel performance . J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 201515051052–1058.doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner DA, Bae J, Cheely G, Milne J, Owens TA, Kuhn CM. Improving resident and fellow engagement in patient safety through a graduate medical education incentive program. J Grad Med Educ . 2018;10(6):671–675. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00281.1. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen EH, Losak MJ, Hernandez A, Addo N, Huen W, Mercer MP. Financial incentives to enhance participation of resident physicians in hospital-based quality improvement projects. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf . 2021;47(9):545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.04.004. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.