Abstract

Adaptive platform trials were implemented during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to rapidly evaluate therapeutics, including the placebo-controlled phase 2/3 ACTIV-2 trial, which studied 7 investigational agents with diverse routes of administration. For each agent, safety and efficacy outcomes were compared to a pooled placebo control group, which included participants who received a placebo for that agent or for other agents in concurrent evaluation. A 2-step randomization framework was implemented to facilitate this. Over the study duration, the pooled placebo design achieved a reduction in sample size of 6% versus a trial involving distinct placebo control groups for evaluating each agent. However, a 26% reduction was achieved during the period when multiple agents were in parallel phase 2 evaluation. We discuss some of the complexities implementing the pooled placebo design versus a design involving nonoverlapping control groups, with the aim of informing the design of future platform trials.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT04518410.

Keywords: COVID-19, adaptive platform trials, pooled placebo, randomization

Adaptive platform trials are randomized clinical trial designs that enable the evaluation of multiple interventions in a single, standardized trial framework [1–4]. Compared with a traditional randomized clinical trial, adaptive clinical trials have preplanned changes or adaptations. Examples of planned adaptations include dropping arms for futility or efficacy, changing allocation ratios across randomized arms, seamless phase 2 to 3 transitions, and sample size reestimation [5, 6]. A fundamental adaptation is the allowance for interventions to be added, dropped, or modified while the study is ongoing [1].

Adaptive platform trials have been used in diverse diseases including infections and cancers [7–10]. To address the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, several adaptive platform studies were deployed to evaluate potential treatments [11–16], including the ACTIV-2 trial. The ACTIV-2 trial is a phase 2/3 adaptive platform trial for the evaluation of novel therapeutics for COVID-19 treatment in nonhospitalized adults (NCT04518410). ACTIV-2 was developed by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group as one of several trials under the umbrella of the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) initiative, a public-private partnership between the United States National Institutes of Health and other government agencies with pharmaceutical collaborators [17]. A key aim of the trial was to rapidly undertake placebo-controlled evaluations of multiple novel investigational agents, with agents being added and dropped during the study. To allow for efficient evaluation of agents in parallel by reducing overall sample size requirements, there was sharing of a concurrent pooled placebo control group that included participants who received placebos for different agents. The aim of this report is to describe our experience using a pooled placebo control group in the ACTIV-2 trial, with the goal of informing use of such control groups in future trials.

METHODS

Overview of the ACTIV-2 Study

ACTIV-2 was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of monoclonal antibodies and other antiviral therapies, with diverse modes of administration, for the treatment of nonhospitalized adults with documented acute severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and symptoms of mild-to-moderate COVID-19. The study included a phase 2 evaluation with transition into a larger phase 3 evaluation for promising agents. To promote collaboration with industry partners in the early stages of product development and expedite phase 2/3 evaluation of multiple agents, the study was designed to evaluate each agent versus placebo and not to compare agents with each other. Details on study objectives and sample size considerations are provided in the Supplementary Material, with full details of the initial design available [18].

Choice of Control Group

A key principle in designing ACTIV-2 was to use a concurrently randomized control group for evaluating each agent and not to include previously enrolled participants as historic controls [19]. The pooled placebo control group for evaluating an agent was composed of participants who could have been randomized to receive that agent, but were instead randomized to receive either the placebo for that agent or a placebo for another investigational agent enrolling concurrently. The decision not to use historic controls reflected concerns about potential bias in the face of a rapidly evolving emergent pandemic, including possible changes to at-risk populations; access to, type of, and timing of diagnostic testing; management of persons with COVID-19; vaccine availability; and viral evolution. There was also a strong desire to use a blinded placebo-controlled design rather than an open-label design, in particular to reduce potential bias in evaluating agents regarding subjectively assessing outcomes, including safety profiles, COVID-19 symptoms, and need for hospitalization.

Randomization Framework With a Pooled Placebo Control Group

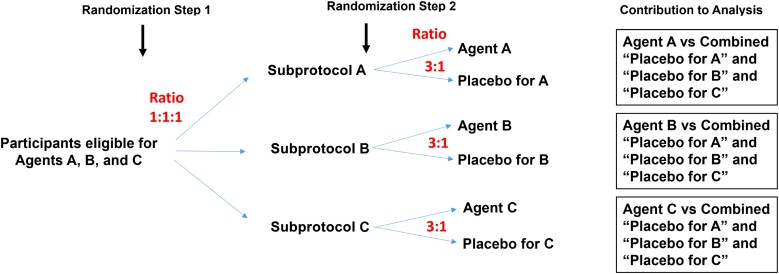

In ACTIV-2, the type-I error rate was controlled separately for each agent, rather than controlling the family-wise error rate control across all agents, which has sometimes been advocated for in platform trials [19, 20]. Separate error rate control for each agent is considered acceptable in guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration [21]. Thus, a randomization framework designed to have an equal number of participants assigned to an active agent as to its pooled placebo control group is optimal in terms of power. With this principle in mind, ACTIV-2 implemented the blinded design using 2 randomization steps within strata defined by the set of agents that a participant was eligible to receive. For a stratum involving r agents, the first step involved unblinded randomization to each of r groups, corresponding to the r agents, with equal probability. In the study's protocol we referred to these groups as agent groups, but here we call them subprotocols as in another COVID-19 platform trial [14]. This reflects the fact that all participants in a subprotocol received the same agent or its placebo, and may have had agent-specific assessments (eg, for adherence or safety issues) besides the standard set of assessments. As an example (Figure 1), in a stratum where participants were eligible to receive any of the 3 agents A, B, and C, randomization was 1:1:1 to subprotocol A, subprotocol B, and subprotocol C.

Figure 1.

Illustrative example of randomization scheme for a stratum of participants eligible for 3 agents, A, B, and C.

The second randomization step was blinded and occurred within subprotocol, where participants were randomized at a ratio of r-to-1 to active agent or its placebo (eg, agent A or the placebo for agent A, within subprotocol A). Using the r-to-1 ratio gave approximately the same number of participants on a specific agent as in the group of participants who received any of the r placebos (see illustrative example in the Supplementary Material). Statistical analysis of a specific agent would then pool from all strata involving that agent. Outcomes among participants assigned that agent would then be compared to outcomes among participants concurrently randomized to placebo, irrespective of which agent's placebo they were assigned (Figure 1). This 2-step randomization results in approximately equal size comparison groups, which maximizes statistical power when the type-I error rate is controlled separately for each agent, irrespective of the number of subprotocols.

Adaptation of the Randomization for Different Schedules of Assessments in Phase 2 Versus Phase 3

The ACTIV-2 randomization had an additional complexity as the schedule of assessments was more intensive in phase 2 than phase 3, with more frequent visits and sample collection for assessing biomarkers. Thus, participants who were randomized to placebo for an agent in phase 3 evaluation did not have all necessary assessments to be included in the pooled placebo group for an agent in phase 2 evaluation. The randomization system therefore had an additional restriction to account for study phase. In the first step, if a participant was assigned to a subprotocol for an agent under phase 2 evaluation, then the second randomization would occur at a ratio of r2:1, where r2 was the number of agents the participant was eligible for that were in phase 2 evaluation. Similarly, if a participant was assigned to a subprotocol for an agent in phase 3 evaluation, the second randomization would occur at a ratio of r3:1, where r3 was the number of agents the participant was eligible to receive that were in phase 3 evaluation. The pooled placebo control group for an agent was then composed of participants eligible to receive that agent, who were randomized to receive a placebo for any agent in the same phase of evaluation.

RESULTS

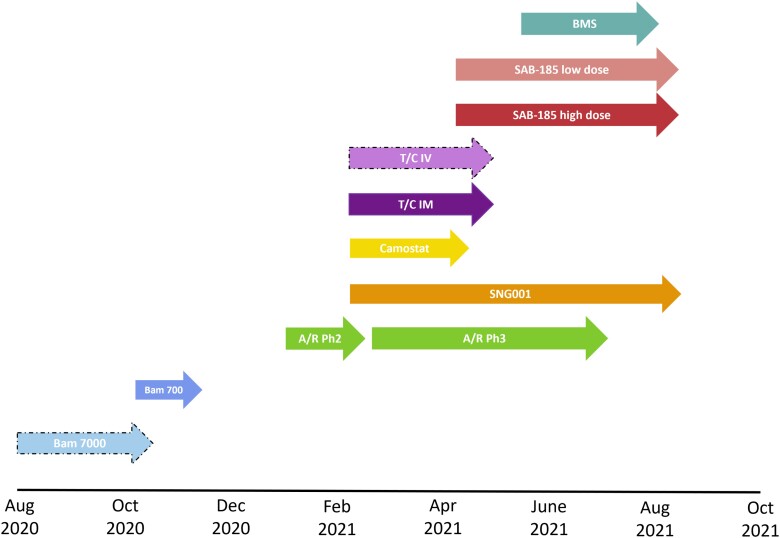

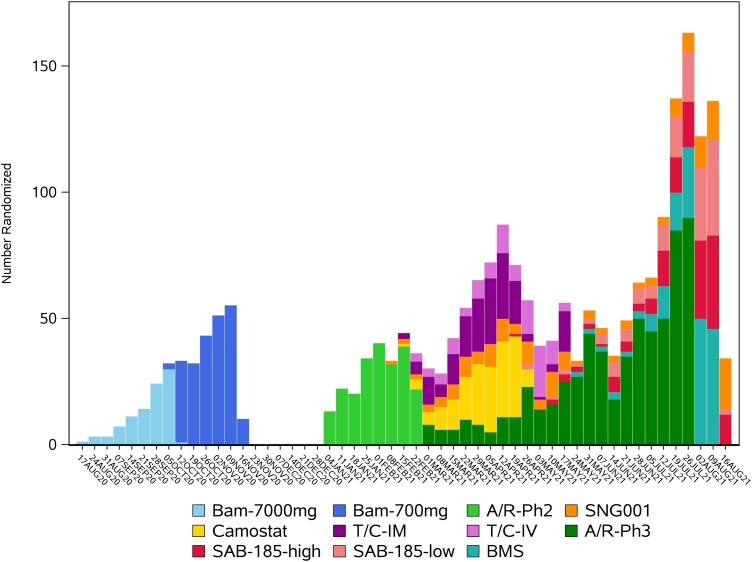

Participants were enrolled between August 2020 and September 2021 to the placebo-controlled evaluations of 7 agents, including 2 evaluated at 2 doses, and 1 evaluated using 2 modes of administration (Table 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). The modes of administration and frequency of dosing were diverse, affirming the decision not to pursue a stricter, double-blind double-dummy design (see Supplementary Material for additional discussion on this decision). Agents given by intravenous infusion or injection were administered at study entry; however, 2 agents had multiday dosing. Only 1 agent, amubarvimab/romlusevimab, underwent placebo-controlled evaluation in both study phases [22]. In terms of enrollment, 2 agents had longer enrollment periods during phase 2 evaluation compared to other agents: for SNG001, this was primarily because of limitations on product availability, and for SAB-185, because enrollment was initially limited to only participants at higher risk of severe COVID-19 progression. Ultimately, the successful development of several very effective agents outside of ACTIV-2 led to ending further placebo-controlled evaluation in our study [23–26]. A more detailed summary of the progression of agents through ACTIV-2 is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Investigational Agents Evaluated in Placebo-Controlled Comparisons ACTIV-2

| Investigational Agent |

Subprotocol | Route of Administration | Risk Group for Severe COVID-19 Progression | Protocol Version Introducing Agent | Total Randomized to Subprotocol (Total Initiated Agent/Placebo) |

LTFU Prior to day 28 No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamlanivimab | Bam 7000mga | IV | H + L | 1 | 94 (94) | 4 (4) |

| Bam 700mg | IV | H + L | 1 (LOA) | 225 (223) | 6 (3) | |

| Amubarvimab/ romlusevimab |

A/R (phase 2 assessments)b | IV | H | 2 | 222 (220) | 9 (4) |

| A/R (phase 3 assessments)b | IV | H | 2 | 624 (617) | 13 (2) | |

| SNG001 | SNG001 | Inhaled (14 d of dosing) |

Initially H + Lc | 3 | 163 (162) | 7 (4) |

| Camostat | Camostat | Oral (7 d of dosing) |

Initially H + Lc | 3 | 167 (160) | 11 (7) |

| Tixagevimab/ cilgavimab |

T/C IM | IM injection | Initially H + Lc | 3 | 164 (160) | 9 (6) |

| T/C IVa | IV | Initially Hc | 3 | 94 (91) | 5 (5) | |

| SAB-185 | SAB high dose | IV | Initially Hc | 4 | 156 (151) | 6 (4) |

| SAB low dose | IV | Initially Hc | 4 | 149 (142) | 2 (1) | |

| BMS-986414 + BMS-986413 |

BMS | SC injection | Initially H + Lc | 5 | 173 (169) | 11 (7) |

Abbreviations: A/R, amubarvimab/romlusevimab; BMS, Bristol Myers Squibb; H, higher risk; IM, intramuscular injection; IV, intravenous infusion; L, lower risk; LOA, letter of amendment; LTFU, lost to follow-up; SC, subcutaneous injection; T/C, tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

Subprotocols for which phase 2 enrollment was terminated early for administrative reasons.

A/R was the only agent with placebo-controlled evaluation in both phase 2 and phase 3.

Initially, agents administered IV were restricted to higher-risk individuals; however, protocol version 6.0 changed inclusion criteria to restrict phase 2 enrollment to only those at lower risk for progression to severe COVID-19, regardless of the route of administration.

Figure 2.

Enrollment timelines for placebo-controlled evaluation of agents in ACTIV-2. Dashed arrow perimeters indicate agents for which phase 2 enrollment was terminated early for administrative reasons. Enrollment shown is for placebo-controlled phase 2 evaluation for all agents and placebo-controlled phase 3 evaluation of A/R (the only agent that underwent placebo-controlled phase 3 evaluation in ACTIV-2). Abbreviations: A/R, amubarvimab/romlusevimab; Bam, bamlanivimab; IM, intramuscular injection; IV, intravenous infusion; Ph, phase; T/C, tixagevimab/cilgavimab.

Figure 3.

Enrollment over time for the placebo-controlled evaluation of agents in ACTIV-2. Abbreviations: A/R-Ph2, amubarvimab/romlusevimab phase 2; A/R-Ph3, amubarvimab/romlusevimab phase 3; Bam-700 mg, bamlanivimab 700 mg; Bam-7000 mg, bamlanivimab 7000 mg; BMS, BMS-986414 + BMS-986413; SAB-185-high, SAB-185 high dose; SAB-185-low, SAB-185 low dose; T/C IV, tixagevimab/cilgavimab by intravenous infusion; T/C-IM, tixagevimab/cilgavimab by intramuscular injection.

The number of subprotocols available for enrollment varied over time (Figure 2 and Figure 3). This also varied among sites due to product availability of some agents and ethical/regulatory approval timelines. A total of 2231 participants from 138 sites were randomized to between 1 and 7 subprotocols during placebo-controlled enrollment (Table 2). Of these, 57% could only have been randomized to 1 subprotocol. There were 4 major reasons for this. First, between August 2020 and January 2021, only a single subprotocol was available for enrollment at any point (accounting for 24% of the 2231). Second, enrollment at non-US sites was limited to the phase 3 evaluation of 1 agent and hence to enrollment to a single subprotocol (13% of 2231). Third, the evolving treatment landscape for nonhospitalized persons with COVID-19 impacted eligibility of participants at lower and higher risk of COVID-19 progression. Agents entering the study later were restricted in the phase 2 evaluation to lower-risk participants and in the phase 3 evaluation of amubarvimab/romlusevimab to higher-risk participants (11% of 2231). The fourth reflects factors such as product availability and differences in eligibility requirements (including that initially only participants at higher risk of severe COVID-19 could be randomized to an infused agent because the logistical demands of infusions were unlikely to be worthwhile in clinical practice for lower-risk individuals; 9% of 2231).

Table 2.

Number of Subprotocols for Which Participants Were Eligible at the Time of Randomization

| Number of Subprotocols for Which a Participant Was Eligible | No. (%) of Participants |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1262 (57) |

| 2 | 294 (13) |

| 3 | 344 (15) |

| 4 | 253 (11) |

| 5 | 74 (3) |

| 6 | 1 (<0.5) |

| 7 | 3 (<0.5) |

The efficiency of using a pooled placebo control group in terms of sample size reduction is difficult to exactly determine due to early termination of 2 subprotocols for administrative reasons; however, we can calculate an approximate value by focusing on the remaining 9 subprotocols that fully accrued. If each of these subprotocols had enrolled their own distinct placebo control groups, the total sample size would have been 2382 participants (220 per agent evaluated in phase 2, plus 622 for the phase 3 evaluation of amubarvimab/romlusevimab). The actual total of 2231 participants therefore achieved a 6% reduction by using pooled placebo controls. This modest reduction largely reflects the large proportion of participants described above who could be randomized to only 1 subprotocol. If we focus only on agents in phase 2 evaluation during the period of parallel evaluation, from 10 February 2021 onwards, using pooled placebo controls achieved a 26% reduction in sample size, from the 1320 participants required if distinct placebo groups had been used, to the 972 participants actually enrolled. This contrasts with the maximum reduction that could have been achieved in the idealistic situation in which all participants were eligible for all these agents and enrollment was completely concurrent, where a 42% reduction in sample size could be achieved.

As there was no blinding of subprotocol, a potential concern was there might be differential uptake of study intervention or rate of loss to follow-up of participants according to the subprotocol to which they were randomized. Table 1 includes a summary of these parameters by subprotocol suggesting there was no notable concern in ACTIV-2 (see Supplementary Material for additional details).

DISCUSSION

Adaptive platform trials offer the opportunity to study multiple investigational agents in a standardized protocol using the same infrastructure (eg, sites, laboratories, data management, and monitoring), which may be attractive during emergent pandemics when new therapies are being rapidly developed and require expedited evaluation. Utilizing pooled placebo control groups can improve efficiency by reducing the total number of trial participants required to evaluate a set of agents, with greater reductions in sample size as the number of agents evaluated in parallel increases. This can accelerate evaluation of safety and clinical efficacy of a set of agents compared to a trial that required distinct placebo control groups for each agent. In addition, the favorable ratio for receiving a potentially active agent versus placebo may be attractive to potential participants (as we observed anecdotally), and possibly enhance the rate of enrollment.

In ACTIV-2, the estimated reduction in sample size overall was small, only 6%, due to the availability of only a single agent for evaluation due to different facets of the trial. However, for 5 agents evaluated in phase 2 (including 1 evaluated at 2 doses) with substantial overlapping periods of evaluation, a larger 26% reduction in sample size was achieved (requiring 348 fewer participants), facilitating earlier decision making about whether to further evaluate these agents.

It is possible, however, that alternative designs might have achieved earlier decisions for the phase 2 evaluation of these 5 agents, although perhaps requiring larger enrollment numbers. For example, ACTIV-2 required participants to be willing to be randomized to any agent available at the site where they enrolled. This was done in part to provide equal opportunity across agents, potentially important for collaborating companies. However, a design allowing participants to choose among modes of administration of agents might have increased the number of interested participants. Similarly, sites might have been able to enroll more participants on a given day if they had flexibility as to what agents could be offered. For example, many agents evaluated in ACTIV-2 were infused and so a potential limiting factor for enrollment might have been infusion capacity and time.

ACTIV-2 was designed to undertake phase 2 evaluation of agents followed by phase 3 evaluation with a reduced schedule of assessments for promising agents. A consequence of the reduced schedule is that recipients of a placebo for an agent being evaluated in phase 3 could not be included as part of the pooled placebo control group for the phase 2 evaluation of another agent (and therefore reduce sample size requirements for the whole trial even further). The differences in assessments between phase 2 and phase 3 corresponded with the differing objectives of the 2 phases. The phase 2 evaluation included a virologic outcome, requiring frequent nasopharyngeal sampling, and more frequent safety and pharmacokinetic assessments that would have been burdensome, and costly, to include in a large phase 3 evaluation focused on determining efficacy for reducing hospitalizations and deaths. It would have been possible to construct a pooled placebo group for an agent in phase 3 that also included participants concurrently randomized to receive placebos for agents in phase 2 evaluation, but this was not undertaken in ACTIV-2. The value of this approach may deserve consideration in other phase 2/3 platform trials, but such a design would likely require a more complex statistical analysis approach to handle time-varying probability of assignment to a specific agent versus pooled placebo group based on the varying number of agents in phase 2 versus phase 3 evaluation.

From a site perspective, implementing and running a platform trial can be complex, although running multiple separate trials to evaluate a similar number of agents in parallel can also be difficult. Compared with using distinct placebo control groups for evaluating each agent, a significant complexity of randomizing to multiple subprotocols with a shared placebo group is that the informed consent process becomes more onerous, requiring information to be provided to participants for each agent/placebo to which they might be assigned. In ACTIV-2, this also involved review of both phase 2 and phase 3 procedures, as not only were multiple agents and placebos possible, but randomization into either a phase 2 or phase 3 evaluation was also possible. Packaging the information and consent forms is further complicated by variation in the set of agents evaluated over time. Even though a substantial effort was made in ACTIV-2 to limit eligibility criteria specific to individual agents, some agent-specific criteria were needed, further complicating the informed consent process. Ultimately, the complexity for sites, and other aspects of the trial infrastructure required to randomize participants among a large number of agents needs to be balanced against the sample size reductions that might be achieved. Although there is not a maximum number of agents a trial could consider, based on our experience, concurrent enrollment to 4 agents is likely an upper bound on the complexity that could be reasonably handled.

A study design complexity that arose in ACTIV-2 was a need to monitor the long-term safety of some antibody treatments to 72 weeks after administration because of their long half-lives. To maintain blinded follow-up and precision in evaluating these outcomes, this required following all participants for 72 weeks to maintain the pooled placebo control groups for evaluating these agents. This included participants randomized to subprotocols for agents with relatively short half-lives, which otherwise would not have required such extended follow-up, potentially increasing costs relative to what might have been needed if a distinct placebo control group was used for each agent. However, in ACTIV-2, the longer-term follow-up for all agents provided the benefit of being able to evaluate so-called long COVID outcomes across the platform. In future studies, such long-term safety follow-up might be restricted to certain subprotocols and so the randomized comparison would be for a specific agent versus its own placebo control with the caveat this would have reduced statistical precision.

An additional limitation of using a pooled placebo group is when protocol objectives are introduced that are specific to a given agent (such as related to the mechanism of action or administration) and thus require agent-specific assessments. For these analyses, the active agent could be compared to participants randomized to the placebo group for that subprotocol only, or perhaps among placebo recipients in the subset of subprotocols involving agents with the same mechanism of action or mode of administration. A decrease in precision in estimating the effects would be expected by restricting the control group in these ways, but may be necessary depending on the outcome of interest. Similarly, an important assumption in using a pooled placebo is that a participant's outcomes would not differ based on the specific placebo received. If this assumption is not valid, such that a control group for a particular agent needs to be restricted to recipients who received the placebo for that agent, then this will also result in loss in precision when evaluating effects of the agent.

When evaluating multiple agents using overlapping pooled placebo control groups, maintaining blinding for evaluating each agent is more complex than in trials with distinct placebo control groups, increasing the potential for bias in randomized comparisons [27, 28]. This complexity arises when collating information about the study population to evaluate a specific agent. In ACTIV-2, it was potentially a more significant issue than it might be in some platform trials as the primary outcomes were evaluated after 28 days of follow-up, but there was blinded long-term follow for 72 weeks. As a simple illustrative example, consider a participant with a particular baseline characteristic or an uncommon adverse event. If this participant appears in a table of baseline characteristics or adverse events summarizing 1 specific agent (even if this table only shows results pooled over arms), then the blind of investigators at their site could be broken if they recognize this participant was actually randomized to the subprotocol for a different agent. In addition, if this participant appeared in summary tables for other agents, or conversely if they did not appear in other tables this could inadvertently reveal if this participant was on a placebo or not, which has broad implications for trial conduct and analysis. Thus, in ACTIV-2, accrual monitoring for an agent was done by unblinded personnel who controlled the released information about reaching a particular target to avoid incidental unblinding for participants who most recently enrolled, and quality assurance of data for interim and primary analyses for a specific agent was performed in a blinded manner where groups of participants who could have potentially been assigned to the agent were determined based on calendar time of enrollment. For interim reviews of a specific agent by a data monitoring committee, so-called open reports did not include baseline characteristics for that agent, and the results of primary analyses provided to blinded personnel and disseminated publicly were summarized in a manner that minimized the possible risk of unblinding.

CONCLUSION

Despite the challenges, ACTIV-2 succeeded in implementing phase 2/3 evaluations of multiple novel agents with different routes of administration, mechanisms and durations of action, and toxicity profiles, employing a pooled placebo design that provided for reductions in sample size requirements. This allowed for rapid evaluation of a broad spectrum of investigational agents.

Based on our experience, the gains in efficiency from using pooled placebo control groups in an adaptive platform trial is likely most valuable in settings where multiple agents with good product availability can be introduced simultaneously across all study sites, with minimal differences in eligibility requirements and study assessments across agents. Even with additional complexities in the informed consent process, more rapid accrual (and attendant cost savings) and hence more rapid evaluation of agents may be achieved if there is increased appeal to participants due to higher probability of receiving a potentially active agent than a placebo, compared with studies evaluating agents with unique placebo control groups. However, as the number of agents being evaluated in parallel increases, so does the complexity of implementing the study, and the potential benefits of using pooled placebo control groups are reduced. Distinct placebo control groups for each agent may then be preferred and, if implemented within a platform trial rather than separate trials for each agent, can still leverage the efficiencies and cost savings achieved through use of a highly standardized trial infrastructure and established network of clinical sites.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Carlee B Moser, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Kara W Chew, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Justin Ritz, Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Matthew Newell, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Arzhang Cyrus Javan, Division of AIDS/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Joseph J Eron, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Eric S Daar, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California, USA.

David A Wohl, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Judith S Currier, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Davey M Smith, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA.

Michael D Hughes, Department of Biostatistics and Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

for the ACTIV-2/A5401 Study Team:

Lara Hosey, Jhoanna Roa, Nilam Patel, Grace Aldrovandi, William Murtaugh, Marlene Cooper, Howard Gutzman, Kevin Knowles, Rachel Bowman, Mark Giganti, Bill Erhardt, and Stacey Adams

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants, site staff, site investigators, and the entire ACTIV-2/A5401 study team; the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, including Lara Hosey, Jhoanna Roa, and Nilam Patel; the ACTG Laboratory Center, including Grace Aldrovandi and William Murtaugh; Frontier Science, including Marlene Cooper, Howard Gutzman, Kevin Knowles, and Rachel Bowman; the Harvard Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research and ACTG Statistical and Data Analysis Center including Mark Giganti; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/Division of AIDS; Bill Erhardt; the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership, including Stacey Adams; and the Pharmaceutical Product Development (PPD) clinical research business of Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Disclaimer . The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UM1 AI068634 to M. D. H., UM1 AI068636 to J. S. C., and UM1 AI106701 to G. A.).

Supplement sponsorship . This article appears as part of the supplement “Findings From the ACTIV-2/AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5401 Adaptive Platform Trial of Investigational Therapies for Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19,” sponsored by the National Institutes of Health through a grant to the University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- 1. Adaptive Platform Trials Coalition . Adaptive platform trials: definition, design, conduct and reporting considerations. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019; 18:797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berry SM, Connor JT, Lewis RJ. The platform trial: an efficient strategy for evaluating multiple treatments. JAMA 2015; 313:1619–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park JJH, Harari O, Dron L, Lester RT, Thorlund K, Mills EJ. An overview of platform trials with a checklist for clinical readers. J Clin Epidemiol 2020; 125:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Woodcock J, LaVange LM. Master protocols to study multiple therapies, multiple diseases, or both. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhatt DL, Mehta C. Adaptive designs for clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pallmann P, Bedding AW, Choodari-Oskooei B, et al. Adaptive designs in clinical trials: why use them, and how to run and report them. BMC Med 2018; 16:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer EL, Mesenbrink P, Dunger-Baldauf C, et al. The evolution of master protocol clinical trial designs: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther 2020; 42:1330–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barker AD, Sigman CC, Kelloff GJ, Hylton NM, Berry DA, Esserman LJ. I-SPY 2: an adaptive breast cancer trial design in the setting of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 86:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Angus DC, Berry S, Lewis RJ, et al. The REMAP-CAP (randomized embedded multifactorial adaptive platform for community-acquired pneumonia) study. Rationale and design. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17:879–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. PREVAIL II Writing Group; Multi-National PREVAIL II Study Team; Davey RT Jr, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of ZMapp for Ebola virus infection. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1448–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vanderbeek AM, Bliss JM, Yin Z, Yap C. Implementation of platform trials in the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid review. Contemp Clin Trials 2022; 112:106625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Files DC, Matthay MA, Calfee CS, et al. I-SPY COVID adaptive platform trial for COVID-19 acute respiratory failure: rationale, design and operations. BMJ Open 2022; 12:e060664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bunning B, Hedlin H, Purington N, et al. The COVID-19 Outpatient Pragmatic Platform Study (COPPS): study design of a multi-center pragmatic platform trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2021; 108:106509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pericàs JM, Derde LPG, Berry SM. Platform trials as the way forward in infectious disease’ clinical research: the case of coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29:277–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Connors JM, Brooks MM, Sciurba FC, et al. Effect of antithrombotic therapy on clinical outcomes in outpatients with clinically stable symptomatic COVID-19: the activ-4b randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 326:1703–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Collins FS, Stoffels P. Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV): an unprecedented partnership for unprecedented times. JAMA 2020; 323:2455–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chew KW, Moser C, Daar ES, et al. Antiviral and clinical activity of bamlanivimab in a randomized trial of non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19. Nat Commun 2022; 13:4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berry SM. Potential statistical issues between designers and regulators in confirmatory basket, umbrella, and platform trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020; 108:444–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collignon O, Gartner C, Haidich A-B, et al. Current statistical considerations and regulatory perspectives on the planning of confirmatory basket, umbrella, and platform trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020; 107:1059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Food and Drug Administration . COVID -19 master protocols evaluating drugs and biological products for treatment or prevention, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/covid-19-master-protocols-evaluating-drugs-and-biological-products-treatment-or-prevention. Accessed 21 July 2022.

- 22. Evering TH, Chew KW, Giganti MJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of combination sars-cov-2 neutralizing monoclonal antibodies amubarvimab plus romlusevimab in nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2023; 176:658–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGEN-COV antibody combination and outcomes in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bernal A J, da Silva MM G, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of COVID-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al. Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Day SJ, Altman DG. Blinding in clinical trials and other studies. BMJ 2000; 321:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995; 273:408–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.