Abstract

Okra is an important traditional vegetable crop grown for its tender fruits in various tropical and sub tropical parts of the world. Yellow Vein Mosaic Disease (YVMD) is the major biotic factor causing severe threat to the okra fruit yield and qualities. The present study was conducted to find out the inheritance of resistance against YVMD and to identify the disease linked molecular markers through bulk segregant analysis. For this, the F1, BC1F1 and BC1F2 generations were derived from a cross between Abelmoschus manihot (PAUAcc-1) as resistant male parent and A. esculentus cv. Punjab Padmini as susceptible female parent. The whole set of populations (F1, BC1F1 and BC1F2) along with parents were subjected to artificial as well as filed screening against YVMD. Chi-square test for goodness to fit revealed that resistance against YVMD is controlled by two recessive genes. The allele of at least one gene in homozygous state mask the effect of other gene and produce a resistant phenotype. The very low polymorphism (31.5%) was detected between the parents by using SSR primers. Out of 200 SSR primers, the four primers i.e. Okra 032, Okra 049, Okra 129 and Okra 270 were found to be linked to YVMD through bulk segregant analysis. The identified SSR primers to YVMD could be further used in okra improvement for YVMD resistance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13337-023-00844-9.

Keywords: Bulk segregant analysis, Disease, SSRs, Wild hybridization, Yellow vein mosaic virus

Introduction

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench) is commonly known as lady’s finger. It is an often-cross pollinated vegetable crop of family Malvaceae originated from Africa and now cultivated in various tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. India ranks first position in the production (63.5 lakh MT) of okra from an area of 5.2 lakh ha with productivity of 12.2 MT/ha [4]. Okra has high medicinal value and its multiple uses make it prominent among fresh vegetables. Okra production is limited for economic and ecological sustainability in vegetable farming systems due to low-yielding potential, poor fruit quality and susceptibility to various biotic stresses. Okra crop is infected by about twenty-seven Begomoviruses which cause serious diseases, among them Yellow Vein Mosaic Disease (YVMD) is the most destructive [21].

Bhendi Yellow Vein Mosaic Virus (BYVMV) is grouped under the genus Begomovirus and family Geminiviridae. BYVMV consists of a monopartite DNA molecule and a betasatellite (DNA component) [15]. It is transmitted through the vector whitefly. The efficiency of transmission of begomoviruses varied with the sex, generally female whiteflies transmit with greater efficiency than males [9]. BYVMV symptoms appear as vein clearing of leaf leaving other part on leaves green, but in extreme cases whole leaf tissues become creamy or yellowish. The disease also affects the size, shape and colour of okra fruits thus reducing their marketability. Depending upon the environmental conditions, vector populations, crop characteristics and growth stage, it may cause 50–94% yield losses [27].

Therefore, any okra improvement program for varietal development will have limited scope without consideration of resistance against YVMD. Wide diversity in wild relatives of okra germplasm provides a great opportunity to find out resistant source and transfer this resistance into cultivated species. For a breeding scheme, to transfer the resistance to the cultivated species requires great knowledge about the genetics of the traits. Okra geneticists have tried to understand the inheritance pattern of YVMD resistance throughout the world without much success. In India, during 1962, it was first reported that two recessive alleles at two loci conferred resistance in intervarietal crosses of okra. This information helped in developing the first YVMD resistant variety Pusa Sawani by using IC-1542, which was free from disease under filed conditions. But later on the presence of two complementary dominant genes [11, 19, 25, 28] and single dominant gene [5, 8, 20] controlling the resistance to YVMD was reported. Further, it was hypothesized that tolerance to YVMD is quantitative, with possibly two major factors and dependent on gene dosage with incompletely dominant gene action [2].

In the year 2001, the complex genetic control to the YVMD resistance due to epistatic gene action was observed [29]. In another study, it was reported that different resistant plants exhibit different genes governing the resistance to YVMD. It was also indicated that when these genes were brought together in the F1 hybrids their effect was duplicated [6]. Later, single dominant gene along with some minor factors governing the disease tolerant trait to YVMD was observed. It was also reported that the different genes governed the resistance in different plants i.e. genotype specific [24]. Further, it was found that the two recessive genes controlling the disease resistance in additive manner [30]. Recently, in an experiment it was concluded that the genetic architecture of the parents plays an important role for YVMD resistance reaction [16].

All the above reports are contradictory to each other and there is lot of variation regarding the genetics of resistance to YVMD. On the other hand, limited information regarding use of molecular markers in okra is available. Very few reports are available regarding the use of Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [1, 17] and Sequence Related Amplified Polymorphism (SRAP) markers for cultivars and germplasm characterization in okra [14]. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) developed for Medicago truncatula were used in okra cultivars [22], but SSRs for okra were not available. During 2013, the combined leaf and fruit transcriptome based SSR markers of okra were developed and used for diversity analysis. There are no reports on linked markers to YVMD or development of genetic maps in okra, till date. Therefore, present research was planned to know about inheritance of YVMD resistance in okra and to identify the linked molecular markers through bulk segregant analysis.

Materials and methods

Plant material

In the present study three sets of population F1, BC1F1 and BC1F2 were involved which were derived from a cross between susceptible A. esculentus cv. Punjab Padmini as female parent and previously selected resistant plants of wild species A. manihot (PAUAcc-1) as pollen parent. The resistance of A. manihot (PAUAcc-1) plants used in the crossing program was confirmed against resistance to YVMD for 2 years under artificial conditions with mass inoculation method (Fig. 1). Further, the resistance in plants was checked using begomovirus specific primers [10].

Fig. 1.

YVMV innoculms maintained under insect proof cage

Phenotypic evaluation

Plant material of all the generations under testing were planted in the rainy season of the year 2019 at Vegetable Research Farm, Department of Vegetable Science, Punjab Agricultural University Ludhiana which is hot spot location for natural screening against YVMD. The seeds of parents namely A. manihot (PAUAcc-1) and A. esculentus cv. Punjab Padmini, their interspecific FI hybrid, BC1F1 and BC1F2 generations were sown in plug trays (Fig. 2). These trays were kept under insect proof cage. For artificial screening against YVMD, the mass inoculation method was adopted. The non-viruliferous whitefly culture was maintained on cotton (Gossipium hirsutum L.) plants grown in pots of size 12 × 8 cm in the insect-proof cage. The inoculums of YVMD were maintained on susceptible okra cultivar “Pusa Sawani” in a separate insect proof cage. To prepare the viruliferous whiteflies for the experiment, clean, healthy whiteflies were given both acquisition and inoculation access period of 48 h. After germination of plants at 2–3 leaf stage, the viruliferous whiteflies were continuously released on the screening material under insect proof cage. One month old plants were sown in the field for natural screening. Row to row and plant to plant spacing for the plant material was 60 × 45 cm. Highly susceptible okra cultivar Pusa Sawani was planted as every 5th row of the experiment and also as border row of the experimental plot. The plants showing symptoms of disease up to 90 days were observed and considered as susceptible plants. This material was kept unsprayed to maintain the whiteflies population for the spread of YVMD under natural epiphytotic conditions. General cultivation practices for raising the good crop were followed as per package of practices book prepared by Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana [3].

Fig. 2.

Okra sown in plug trays

Data analysis

For all segregating generations the observed data was classified according to the expected groups and the deviations of the observed numbers from the calculated numbers were determined. The Chi-square (χ2) value was computed, and the corresponding probability value obtained.

The Chi-square (χ2) test for goodness of fit was made by subjecting the data to the following formula:

where N = Number of genotypic classes, D.F. = Degrees of Freedom, ∑ = Summation, O = Observed number of plants in each class, E = Expected number of plants in each class

Parental polymorphism

Genomic DNA of 168 BC1F2 plants along with both the parents (A. esculentus cv. Punjab Padmini and A. manihot PAUAcc-1) were isolated by using modified cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method [13]. A total volume of 10 µL reaction mixture composed of lµL Taq polymerase (3U), 2.0 µL 5X PCR buffer, 0.6 µL MgCl2, 3.0 µL template DNA (50 ng/l µL), 0.6 µL of each primer (10 mM), 2.0 µL dNTP mix and 0.2 µL ddH2O was applied for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR profile involved in the thermal cycler consisted of initial denaturation at temperature of 94 °C (5 min), denaturation at 94 °C (1 min), annealing at 50–60 °C (1 min) and extension at 72 °C (2 min) involving 35 cycles. The final extention of 7 min at temperature of 72 °C was applied. The PCR product was kept at 4 °C after the completion. After amplification, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the amplified PCR product was done by loading it in 6% polyacrylamide gel prepared in 0.5X TBE buffer. To evaluate the polymorphism between the parents 200 primer pairs of SSR primers were used [23]. List of primers is enlisted in Supplementary Table 1.

Bulked segregant analysis

The SSR primers exhibiting polymorphism between the parents were verified following bulked segregant analysis (BSA). Two DNA bulks, resistant bulk (comprising 8 homozygous-resistant plants) and susceptible bulk (comprising 8 homozygous-susceptible plants), were prepared [18]. Genomic DNA of BC1F2 individuals was bulked after determining the genotype of BC1F2:3 individuals for disease resistance during phenotypic evaluation. Primer pairs putatively associated with YVMD resistance were validated on individual resistant and susceptible plants that comprised the bulks.

Results

Segregation analysis

All the plants in F1 and BC1F1 generations showed susceptible reaction to BYVMV disease (Table 1). Out of 168 plants assessed for resistance in BC1F2, 89 were observed susceptible and 79 were found to be resistant. The calculated chi square value of 0.73 was found to be non-significant at one degrees of freedom as the table value was 3.84. So, there is no significant difference between the observed and expected ratios (9:7). It was depicted that the two recessive genes are controlling the resistance of the YVMD disease. When the recessive allele of either of gene is in homozygous state it masks the effect of the other gene (recessive epistatis).

Table 1.

Frequency of segregates showing susceptible/resistance reaction to YVMD

| Generation | Susceptible | Resistant | Total | Ratio | χ2 Calculated value | χ2 Table value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 8 | 0 | 8 | – | – | – |

| BC1F1 | 26 | 0 | 26 | – | – | – |

| BC1F2 | 89 | 79 | 168 | 9:7 | 0.73 | 3.84 |

χ2 at 5% level of significance p value − 0.39

Parental polymorphism

A total of 200 SSR markers were analyzed on Punjab Padmini and A. manihot (PAUAcc-1) inbred lines for parental polymorphism and a detailed list of SSR markers surveyed is enlisted in Supplementary Table 1. Out of 200 SSR markers, 61 were polymorphic, 61 not amplified and 78 were monomorphic showing overall 31.5% of polymorphism.

Bulked segregant analysis

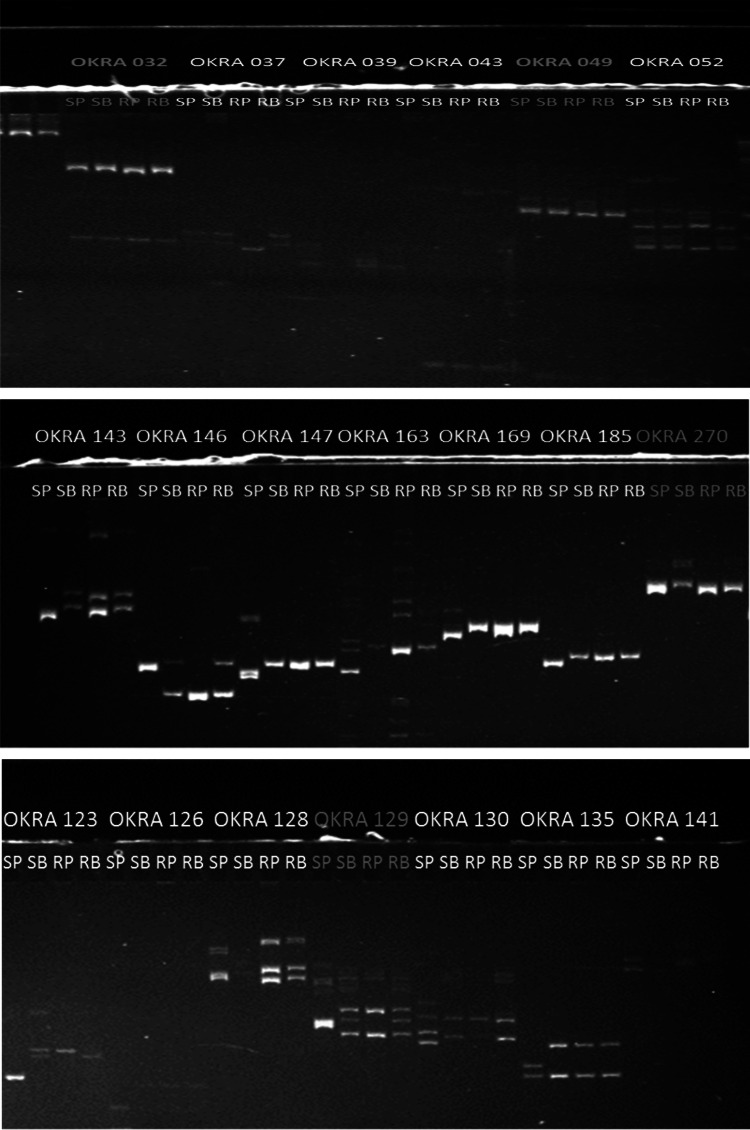

Out of 200 primer pairs, 61 polymorphic primer pairs identified based on the parental polymorphism were used to distinguish the resistant and susceptible bulked DNA samples. The polymorphism consisted of upper and lower DNA amplicon difference in fluorescence intensity between the two bulked DNA samples along with the parental DNA samples (Fig. 3). Four SSR markers viz. Okra 032, Okra 049, Okra 129 and Okra 270 out of 61 polymorphic primer pairs in parental DNA samples differentiated the YVMD resistant and susceptible bulks. These primers were further amplified on individual YVMD resistant and susceptible plants that comprised the respective DNA bulks. These four SSR markers clearly distinguished the YVMD resistant and susceptible plants.

Fig. 3.

SSR markers linked to YVMD in BSA SP: susceptible parent, SB: susceptible bulk, RP: resistant parent, RB: resistant bulk

Discussion

The knowledge about inheritance to YVMD resistance is very important for the incorporation of resistant genes from one species to other species. It helps in planning a breeding scheme and choosing an appropriate breeding method for developing new varieties against YVMD. The results from the present study depicted that the two recessive genes are found to be contributing in controlling the resistance against YVMD. Alleles of at least one recessive gene in homozygous state are required to impart resistance against disease. Homozygous state of alleles of either one of the genes masks the effect of other gene and produces a resistant phenotype. The results of the study were confirmed with the resistance to YVMD controlled by two recessive genes in okra [26, 30]. On contrary, a complementary dominant gene controlling the resistance to YVMD was reported [16]. The differences in the results may be due the use of different source of plant materials. It was reported that the resistance to YVMD depends upon the genetic architecture of the plants [6, 16, 24]. The solution to this problem could be the genotyping of the okra for YVMD trait. There is no information regarding construction of genetic maps or gene sequencing of okra crop.

Bulked segregant analysis is an approach to identify the makers linked to specific regions in the genome. Through this technique, two contrasting bulks for a particular gene of interest that differentiate them (e.g. resistant and susceptible to a specific disease) are examined to find out linked markers [18]. Polymorphic markers between the contrasting bulks will be heritably linked to the loci defining the trait used to construct the bulks. Bulked segregant analysis approach has immediate application for genetic maps development by studying the inheritance of randomly selected genetic markers in a single population. This approach was used over bulks for the mapping of verticillium wilt through SSR markers [7] and similarly, molecular markers linked with genetic male sterility were identified in cotton [12].

Conclusion

Yellow vein mosaic virus disease is very destructive disease which reduces okra fruit yield and quality. The knowledge about the inheritance to the resistance is very important for the breeders which is still controversial for this disease. The study concluded that the resistance to yellow vein mosaic disease is controlled by two recessive genes. There is also very limited information on the use of molecular markers in okra and still no genetic map is constructed. The four primer pairs viz. Okra 032, Okra 049, Okra 129 and Okra 270 identified through bulk segregant analysis that could be further used for constructing genetic maps.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Authors are grateful to the authorities of Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana for providing the required resources and support for the conduct of this research work. The first author is the student of Mamta Pathak, for his Ph. D thesis submitted to Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana.

Data availabilty

All data generated for this study are included in the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study does not include results of studies involving animals or humans.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aladele SE, Ariyo OJ, Pena DLR. Genetic relationships among West African okra (Abelmoschus caillei) and Asian genotypes (Abelmoschus esculentus) using RAPD. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7:1426–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali M, Hossain MZ, Sarker NC. Inheritance of Yellow Vein Mosaic Virus (YVMV) tolerance in a cultivar of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) Euphytica. 2000;111:205–209. doi: 10.1023/A:1003855406250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. Package and practices for cultivation of vegetables. Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, Punjab; 2018.

- 4.Anonymous. Area, production and productivity of okra in India. http://www.Indiastat.com. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

- 5.Arumugum R and Muthukrishnan CR. Studies on resistance to yellow vein mosaic in bhindi (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench). Proc Natl Seminar Dis Res Crop Pl. Coimbatore, India;1980.

- 6.Arora D, Jindal SK, Singh K. Genetics of resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus in inter-varietal crosses of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench) SABRAO J Breed Genet. 2008;40(2):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolek Y, El-Zik KM, Pepper AE, Bell AA, Magill CW, Thaxton PM, Reddy OUK. Mapping of verticillium wilt resistance genes in cotton. Pl Sci. 2005;168:1581–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonsirichai K, Phadvibulya V, Adthalungrong A, Srithongchai W, Puripunyavanich V, Chookaew S. Genetics of the radiation induced yellow vein mosaic disease resistance mutation in Okra. Induced plant mutations in the genomics era food and agriculture organization of the United Nations, Rome; 2009:352–4.

- 9.Czosnek H, Ghanim M, Morin S, Rubinstein G, Fridman V, Zeidan M. Whiteflies: vectors, and victims of geminiviruses. In: Harris KH, Smith OP, Duffy JE, editors. Virus–vector–plant interactions. New York: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng D, Mcgrath PF, Robinson DJ, Harrison BD. Detection and differentiation of whitefly transmitted geminiviruses in plants and vector insects by the polymerase chain reaction with degenerate primers. Ann Appl Biol. 1994;125:327–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1994.tb04973.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhankhar SK, Dhankhar BS, Yadava RK. Inheritance of resistance to yellow veinmosaic virus in an inter-specific cross of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Indian J Agric Sci. 2005;75:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dharmalingam R, Marappan SK, Ponnuswamy RD, Sankaran L, Kamalasekharan R, Nallathambi K, Vaidyanathan S. Identification of molecular markers associated with genic male sterility in tetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) through Bulk segregant analysis using a cotton SNP 63K Array. Czech J Genet Pl Breed. 2018;54:154–160. doi: 10.17221/25/2017-CJGPB. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh R, Paul S, Ghosh SK, Roy A. An improved method of DNA isolation suitable for PCR-based detection of begomoviruses from jute and other mucilaginous plants. J Virol Methods. 2009;159:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulsen O, Karagul S, Abak K. Diversity and relationships among Turkish okra germplasm by SRAP and phenotypic marker polymorphism. Biol Bratislava. 2007;62:41–45. doi: 10.2478/s11756-007-0010-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jose J, Usha R. Bhendi yellow vein mosaic disease in India is caused by association of a DNA-β satellite with a begomovirus. Virology. 2003;305:310–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khade YP, Kumar R, Yadav RK. Genetic control of yellow vein mosaic virus resistance in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Indian J Agric Sci. 2020;90:606–609. doi: 10.56093/ijas.v90i3.101497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinello GE, Leal NR, Amaral AT, Pereira MG, Daher RF. Comparison of morphological characteristics and RAPD for estimating genetic diversity in Abelmoschus spp. Acta Hort. 2001;546:101–104. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2001.546.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michelmore RW, Pran I. Kesseli RV Identification of markers linked to disease-resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9828–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pullaiah N, Reddy TB, Moses GJ, Reddy BM, Reddy DR. Inheritance of resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench) Indian J Genet. 1998;58:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rattan RS, Bindal A. Development of okra hybrids resistant to yellow vein mosaic virus. Veg Sci. 2000;27(2):121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanwal SK, Singh M, Singh B. Naik PS Resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus and okra enation leaf curl virus: challenges and future strategies. Curr Sci. 2014;106:1470–1471. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawadogo M, Ouedraogo JT, Balma D, Ouedraogo M, Gowda BS, Botanga C, Timko MP. The use of cross species SSR primers to study genetic diversity of okra from Burkina Faso. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:2476–2482. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schafleitner R, Kumar S, Lin C, Hegde SG, Ebert A. The okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) transcriptome as a source for gene sequence information and molecular markers for diversity analysis. Gene. 2013;517:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senjam P, Senapati BK, Chattopadhyay A, Dutta S. Genetic control of yellow vein mosaic virus disease tolerance in Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench. J Genet. 2018;97:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s12041-017-0876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma BR, Dhillon TS. Genetics of resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus in inter-specific crosses of okra (Abelmoschus species) Genet Agraria. 1983;37:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh HB, Joshi BS, Khanna PP, Gupta PS. Breeding for field resistance to yellow vein mosaic in bhindi. Indian J Genet Pl Breed. 1962;22:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solankey SS, Akthar S, Kumar R, Verma RB, Kumar S. Seasonal response of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench) genotypes for okra yellow vein mosaic virus incidence. Afr J Biotech. 2014;13(12):1336–1425. doi: 10.5897/AJB2014.13624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thakur MR. Inheritance of resistance to yellow vein mosaic in a cross of okra species, Abelmoschus esculentus × A. manihot ssp manihot. SABRAO J Breed Genet. 1976;8:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vashisht VK, Sharma BR, Dhillon GS. Genetics of resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus in okra. Crop Improve. 2001;28:218–225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasala S, Senevirathne SI, Senanayake JB, Navoditha A. Genetics analysis of okra yellow vein mosaic virus disease resistance in wild relative of okra Abelmoschus angulosus Wal ex Weight & Arn. Pl Gen Resour. 2019 doi: 10.1017/S1479262119000078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated for this study are included in the manuscript.