Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus is a gram-negative soil bacterium which exhibits a complex life cycle and social behavior. In this study, two developmental mutants of M. xanthus were isolated through Tn5 transposon mutagenesis. The mutants were found to be defective in cellular aggregation as well as in sporulation. Further phenotypic characterization indicated that the mutants were defective in social motility but normal in directed cell movements. Both mutations were cloned by a transposon-tagging method. Sequence analysis indicated that both insertions occurred in the same gene, which encodes a homolog of DnaK. Unlike the dnaK genes in other bacteria, this M. xanthus homolog appears not to be regulated by temperature or heat shock and is constitutively expressed during vegetative growth and under starvation. The defects of the mutants indicate that this DnaK homolog is important for the social motility and development of M. xanthus.

Myxococcus xanthus is a gliding bacterium that exhibits complex social behavior (10). Upon starvation, cells aggregate to form fruiting bodies (10). This cellular aggregation process requires intercellular signaling, coordinated and directed cell movement, and temporal and spatial gene expression (20, 22, 24, 45). Previous studies showed that M. xanthus has dual motility systems (17, 18): (i) system A (adventurous) is required for the movement of single cells or small groups of cells; (ii) system S (social) is required for the coordinated movement of large cell groups. Social motility has been shown to be important for fruiting body formation (17, 18, 30). The cellular aggregation process also requires directed cell movement (45, 47). A group of frz genes, homologous to the chemotaxis genes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, were found to be important for directing M. xanthus cells into aggregation centers (32, 45, 47). To further understand the mechanism(s) of cellular aggregation, we isolated and characterized additional mutants that are defective in cellular aggregation. This paper reports two of these mutants, both of which have a mutated gene homologous to the dnaK gene of E. coli. The same gene has also been identified by Patricia Hartzell’s group at the University of Idaho (58).

E. coli dnaK encodes a heat shock protein of the hsp70 family (3). It is regulated by and required for heat shock (5, 13, 56). Many DnaK homologs have also been identified in various other bacteria (27, 37, 40, 44, 55, 57, 59, 66). DnaK generally forms a multisubunit complex with DnaJ and GrpE. All three genes are regulated by a heat-inducible alternative sigma factor (sigma-32) (8, 14, 38, 43, 48, 54, 60, 61, 65). The DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE complex serves as a molecular chaperone which is involved in cellular motility, cell division, protein folding and secretion, RNA and DNA synthesis, and the regulation of heat shock responses (9, 12, 14, 15, 26, 43, 48, 54, 60, 61, 65). Here we report that this M. xanthus DnaK homolog is required for social motility and cellular aggregation of M. xanthus and that the expression of this gene is not regulated by heat shock or by nutrient conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown and maintained in LB medium (35). M. xanthus was grown and maintained at 32°C in CYE medium (6). Other media used in this study include morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) medium (10 mM MOPS [pH 7.6], 8 mM MgSO4), A-1 minimum medium (4), and CF medium (16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| XL2-Blue MRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)Amy Camr] | Stratagene |

| M. xanthus | ||

| DZF1 | sglK+ sglA (leaky) | 36 |

| DZ2 | sglK+ sglA+ | 7 |

| SW107 | sglK:Tn5lac sglA (leaky) | This study |

| SW164 | sglK:Tn5kan903 sglA (leaky) | This study |

| SW300 | sglK:Tn5lac sglA+ | This study |

| SW301 | sglK:Tn5kan903 sglA+ | This study |

| Phages | ||

| P1::Tn5lac | Bacteriophage P1 with Tn5lac insertion | 21 |

| P4::Tn5kan903 | Bacteriophage P4 with mini-Tn5kan903 | B. Julien |

| Mx4 | General transduction phage for M. xanthus | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Cloning vector; ColE1 replicon; Apr | 63 |

| pYG109 | pUC18 with an EcoRI fragment containing the Tn5kan903 insertion and the flanking region from SW164 | This study |

| pYG111 | pUC18 with an EcoRI fragment containing partial Tn5lac and the downstream region from SW107 | This study |

Phenotypic characterization of the nonfruiting mutants.

The following experiments were performed to characterize the mutants. For fruiting body formation, cells at about 5 × 108 cells/ml were placed on MOPS or CF plates (1.5% agar) and incubated at 32°C for 2 to 3 days. For the examination of developmental spores, M. xanthus cells were spotted onto CF plates and incubated at 32°C for 7 days. Spore formation was then examined by light microscopy. The spores are refractile spherical cells which are resistant to 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. For swarming, 20 μl of cells at about 5 × 108 cells/ml was spotted on the center of a swarming plate (CYE with 0.3% agar) and incubated at 32°C for 3 to 4 days (46, 49). Cell motility was assayed by time-lapse videomicroscopy as described by Shi and Zusman (49). Social motility was further studied by microscopic observation of colony edges and by a cellular agglutination assay. The agglutination assay was performed by the method described by Wu et al. (62). The assays for chemotaxis and methylation of FrzCD were performed by methods described previously (34, 46).

Heat shock and labeling conditions.

A procedure similar to that described by Nelson and Killeen was used (39). Cells grown at 24°C in A-1 medium (4) to exponential phase were harvested, washed twice, and then resuspended at 0.1 unit of optical density at 600 nm (OD600) in A-1 medium without methionine. The cells were equilibrated at 24°C for 1 h and pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine (∼10 μCi per ml) for 15 min at 40 or 24°C. The cells were immediately put on ice and mixed with cold methionine at 10 μg per ml, harvested at 4°C, and washed twice with 15 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Whole cell lysates were prepared (34, 46) and subsequently analyzed by electrophoresis on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel (42).

Molecular techniques.

Either P1::Tn5lac (21) or P4::Tn5kan903 (courtesy of Bryan Julien, Stanford University) was used for transposon mutagenesis as described previously (25). Myxophage Mx4 was used for generalized transduction (41). EcoRI-digested pUC18 was used to clone the mutations. M. xanthus genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (2, 64), digested with EcoRI, and ligated to the vector. Tn5 insertion was used as a selectable marker (it confers kanamycin resistance) for the cloning. The mutated genes were sequenced by using primers complementary to the known DNA sequences at the ends of the Tn5 constructs. DNA sequencing was performed by the automated DNA sequencing facility at the University of California, Davis. Sequence analysis was performed with BLAST and BCM Search Launcher (1, 52). β-Galactosidase activities were assayed as described by Kroos et al. (24).

RESULTS

Isolation and phenotypic characterization of two nonfruiting mutants.

A genetic screening was carried out to identify genes involved in cellular aggregation and development of M. xanthus. Strain DZF1 is wild type with regard to fruiting body formation but contains a leaky sglA gene, a gene involved in social gliding motility (6). The strain was used for initial transposon mutagenesis because it forms fewer cell clumps. Using P4::Tn5kan903 and P1::Tn5lac, we isolated more than 10,000 Tn5 insertional mutants. These mutants were streaked on CF plates and examined for cellular aggregation and fruiting body development. About 200 mutants with various degrees of defects in fruiting body formation were identified (11a). The linkage between the fruiting defects and Tn5 insertions was confirmed by introducing the Tn5 mutations back to DZF1 and to DZ2 by Mx4-mediated generalized transduction. SW107 (Tn5lac insertion) and SW164 (Tn5kan903 insertion) are two such mutants identified in this screening (Table 1). SW300 and SW301 are the two corresponding mutants in the DZ2 background, produced by Mx4 generalized transduction (Table 1). These two mutants are reported here because they exhibited identical phenotypes and were later found to harbor mutations in the same gene, sglK.

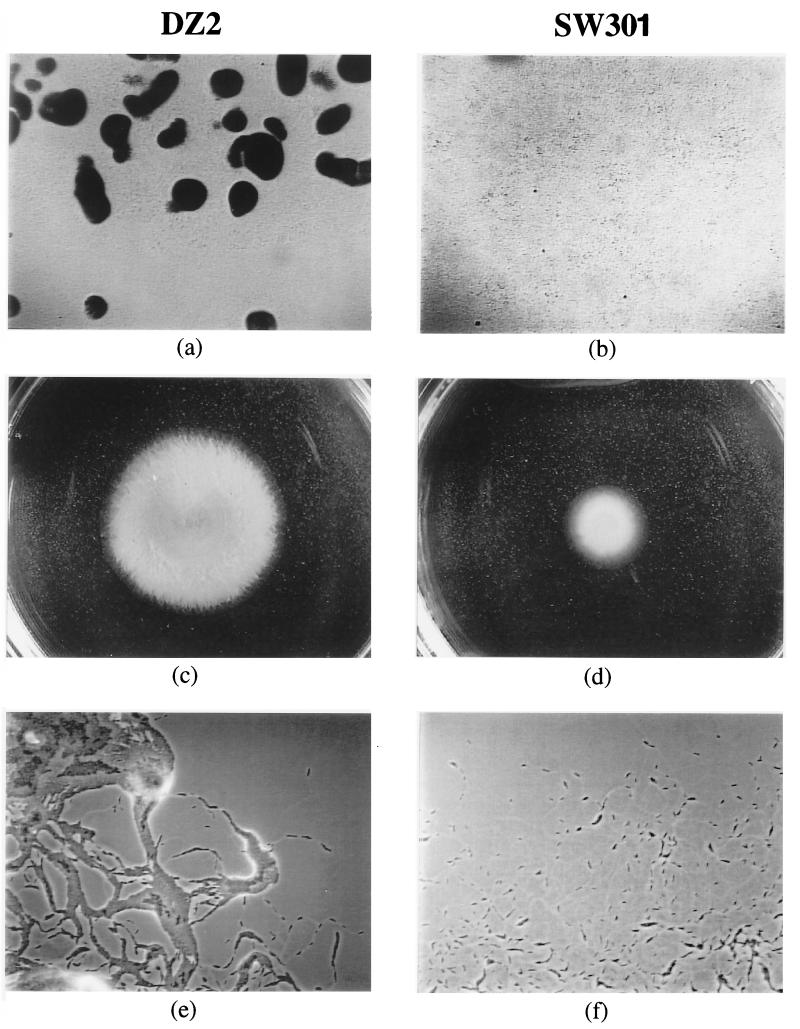

Figure 1 shows the phenotypes of the mutant SW301 in comparison with the wild-type strain DZ2. SW300 showed the same phenotypes as SW301 (data not shown). After 2 days of incubation on CF plates, wild-type DZ2 cells formed visible fruiting bodies (Fig. 1a), in which portions of cells eventually developed into myxospores after 5 to 7 days. The mutants did not form any cellular aggregates even after 5 days (Fig. 1b), and only a small portion of the mutant cells developed into spores (<5% of the wild-type parent DZ2). We also tested the swarming ability of the mutants and found that they were defective in swarming on CYE plates with 0.3% agar (Fig. 1d).

FIG. 1.

Phenotypic characterization of wild-type and mutant M. xanthus strains, performed as described in Materials and Methods. Wild-type DZ2 forms fruiting bodies on CF agar after 2 days of incubation (a); SW301 does not form any fruiting bodies even after 5 days (b). On CYE plus 0.3% agar, DZ2 forms a swarming colony about 4.0 cm in diameter after 5 days (c); the colony formed by SW301 is 1.5 cm in diameter (d). On 1.5% agar, advancing colony edges of DZ2 contain both single cells and large cell groups (e), while those of SW301 contain only single cells and small cell groups (f). SW300 shows the same phenotype as SW301.

The two nonfruiting mutants are normal in directed cell movement but defective in social motility.

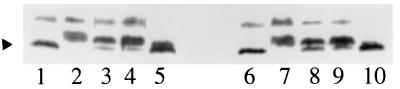

The swarming and fruiting defects of the mutants may result from defects either in directed cell movement or in cellular motility. Previous studies showed that wild-type M. xanthus exhibits directed cell movements in response to various chemicals (31, 47). These chemotactic movements were found to be associated with cellular reversal frequency and the modification of FrzCD, a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (31, 47). The methylation of FrzCD was found to be modulated over the course of development (33). Moreover, such changes in FrzCD methylation play important roles in directed cell movement during fruiting body formation (33, 47, 53). SW300 and SW301 were tested with the various assays mentioned above and found to respond to various chemicals as did the wild-type strain. For example, they increased their cellular reversal frequency from once every 4 to 6 min to about once every minute in response to 0.1% isoamyl alcohol. Furthermore, the methylation patterns of the mutants are similar to that of the wild type in response to fresh CYE, starvation, and 0.1% isoamyl alcohol (Fig. 2). These data indicate that both SW300 and SW301 are normal for directed cell movements under the conditions examined.

FIG. 2.

Modification of FrzCD in wild-type and mutant strains. The methylation/demethylation pattern of FrzCD was assayed by Western blotting as previous described (34, 46). The arrowhead indicates the position of methylated FrzCD. Wild-type and mutant cells were treated with fresh CYE (chemoattractants) or 0.1% isoamyl alcohol (chemorepellents) for 1 h or starved in MOPS buffer for various lengths of time with shaking and then collected for FrzCD methylation assay. Lanes 1 and 6, DZ2 and SW301 in fresh CYE medium, respectively; lanes 2 and 7, DZ2 and SW301 in MOPS plus 0.1% isoamyl alcohol; lanes 3 to 5, DZ2 cells starved in MOPS buffer for 1, 8, and 24 h; lanes 8 to 10, SW301 cells starved in MOPS buffer for 1, 8, and 24 h. SW300 shows the same methylation/demethylation patterns of FrzCD as SW301 and DZ2.

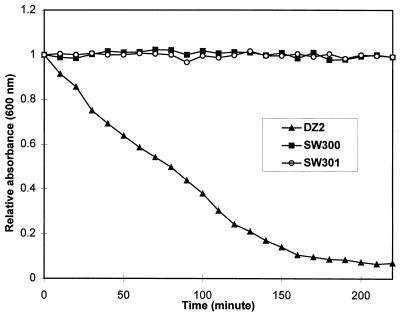

Using videomicroscopy, we also found that single cells of SW300 and SW301 are as motile as wild-type cells. The mutant cells are also proficient in swarming on 1.5% agar plates. Therefore, the mutants are normal in A motility. As shown in Fig. 1f, the edges of the mutant colonies only have single cells or small cell groups, indicating that the mutant cells are defective in S motility. Moreover, unlike the wild-type DZ2 cells, mutant cells grown in liquid culture do not form cell clumps, which is another indication of defective S motility. It is known that defects in S motility may result in reduced cellular cohesion, which can be measured by an agglutination assay (50, 62). Figure 3 shows that both mutants are defective in agglutination, indicating that these strains are defective in cellular cohesion. The defects of the mutants in fruiting body formation and in swarming on 0.3% agar plates are also consistent with defects in S motility (18, 23, 49).

FIG. 3.

Agglutination assay. Cells were grown in CYE at 32°C overnight to an OD600 about 0.5 and allowed to agglutinate at room temperature, and the OD600 was measured every 10 min. The relative absorbance was calculated by dividing the absorbance at a given time by the initial absorbance. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. DZ2 is the wild-type strain, whereas SW300 and SW301 are the two sglK mutants in the DZ2 background.

SW300 and SW301 harbor mutations in the same gene, which is highly homologous to the gene for heat shock protein DnaK.

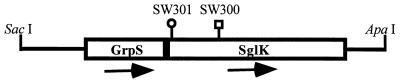

Using the Tn5 insertion as a selectable marker, the mutated genes in SW300 and SW301 were cloned and partially sequenced. Sequence analysis indicates that both SW300 and SW301 have Tn5 inserted in a region encoding homologs of two heat shock proteins of E. coli, GrpE and DnaK. A GenBank search indicated that the DNA sequence is identical to the M. xanthus sequence of grpS and sglK recently submitted by Hartzell’s group at the University of Idaho (accession no. U83800). About 5 kb of DNA in this genetic locus, a region which contains an operon consisting of the grpE and dnaK homologs, has been sequenced by Hartzell’s group. Based on the DNA sequence, we found that both SW300 and SW301 have the Tn5 insertions at the N terminus of the sglK gene (Fig. 4). The phenotypes of SW300 and SW301 are also largely consistent with what they have described (28, 29, 58).

FIG. 4.

Organization of grpS and sglK and insertion of Tn5 in SW300 and SW301. A 3.68-kb SacI-ApaI fragment is depicted. The open reading frames of grpS and sglK are marked. The arrows indicate the directions of the two open reading frames, which are 8 bp apart. The predicted GrpS and SglK peptide sequences exhibit 26 and 58.5% identity with E. coli GrpE and DnaK, respectively. grpS and sglK were also isolated by Hartzell’s group (GenBank accession no. U83800). The insertions in SW300 and SW301 are indicated. The circle indicates the insertion of Tn5kan903 in SW301, whereas the square indicates the insertion of Tn5lac in SW300.

The DnaK homolog of M. xanthus is not regulated by temperature or by growth conditions.

E. coli dnaK mutants are temperature sensitive in growth and in cell division (5, 14, 15). We therefore examined the growth of the mutants on CYE plates and their cell morphology under a microscope. At 40°C, the absolute temperature maximum for M. xanthus growth (19), both the mutant and the wild-type strains showed scattered growth with no obvious defects in cell morphology. At all other temperatures examined (15, 24, 32, and 38°C), normal growth and cell morphology were observed for the mutants and the wild type alike. Thus, it is unlikely that sglK in M. xanthus is the functional equivalent of dnaK in E. coli.

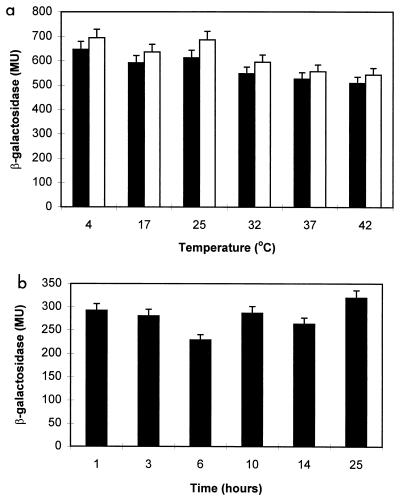

It is known that the expression of DnaK in E. coli is regulated by heat shock. Since SW300 contains a promoterless lacZ gene inserted in the same orientation as the sglK gene, we were able to assay its expression via the level of β-galactosidase. We found that the expression of the M. xanthus dnaK homolog remained the same at different temperatures (Fig. 5a), indicating that the sglK gene may not be regulated by heat shock. In addition, sglK appears to be constantly expressed during vegetative growth (data not show) and shows little fluctuation under developmental starvation (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Expression of the sglK gene assayed by β-galactosidase activity from an sglK-lacZ fusion. β-Galactosidase activity was determined in strain SW300 as described by Kroos et al. (24) and is presented in Miller units (MU) (35). (a) Effect of temperature on the expression of sglK. SW300 cells grown at 32°C were shifted to various temperatures for either 5 min (solid bars) or 30 min (open bars) and then collected for β-galactosidase assay. (b) Effect of starvation on expression of the sglK gene. SW300 cells grown in CYE medium were resuspended in starvation medium (MOPS buffer). Samples were collected for β-galactosidase assay at different time points during starvation. The data shown are averages of duplicate samples.

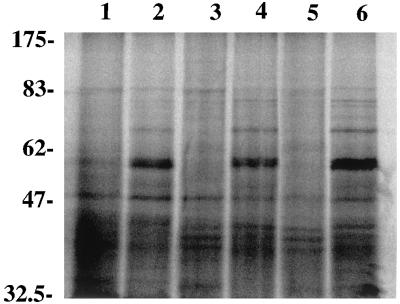

It was somewhat surprising that sglK, a homolog of E. coli dnaK, seems not to be regulated by heat shock. Pulse-labeling experiments were therefore performed to evaluate the expression of heat shock proteins in both the mutant and the wild-type strains. As shown in Fig. 6, when cells were shifted from 24 to 40°C, a number of heat shock proteins were expressed in both the wild-type and the mutant strains. The mutants have almost the same expression patterns of heat shock proteins as the wild type. There is no band missing in the mutants around the calculated molecular mass of SglK (65.3 kDa). Therefore, unlike E. coli DnaK, SglK is not a major heat shock protein in M. xanthus.

FIG. 6.

Production of heat shock proteins by M. xanthus. Cells grown at 24°C were labeled as described in Materials and Methods for 15 min with [35S]methionine and then either shifted to 40°C for heat shock treatment (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or kept at 24°C (lanes 2, 4, and 6). Whole-cell lysates from the same amount of cells were loaded on each lane. DZF1 lysates were loaded on lanes 1 and 2, SW107 lysates were loaded on lanes 3 and 4, and SW164 lysates were loaded on lanes 5 and 6. Molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons on the left.

DISCUSSION

When M. xanthus cells are under the stress of starvation, they undergo a developmental program in which cells aggregate to form fruiting bodies and eventually differentiate into myxospores (10). Identification of the molecular components involved in this cellular process would facilitate the elucidation of the underlying mechanisms of such a complex developmental process. Even though many developmental genes of M. xanthus have been identified (11, 51), their physiological functions are for the most part not directly related to one another. Therefore, more components involved in this cellular process are yet to be identified.

In this study, two mutants defective in fruiting body formation were isolated through a genetic screening. Both mutants exhibited wild-type behavior in single-cell motility and directed cell movement. The mutants also showed modification of FrzCD similar to that of the wild-type strain during starvation and in response to various chemicals (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, they showed little or no aggregation under developmental conditions (Fig. 1b). It was then discovered that the mutants are defective in social motility (Fig. 1d and f), which could possibly result in the defects in aggregation and fruiting body development because of the impaired cell-cell interaction and communication. Cloning and sequencing analysis indicated that both mutations occurred in the same gene, encoding a DnaK homolog of the hsp70 family.

As a stress protein, DnaK has been found to be required for various stress responses in other bacteria, including responses to heat shock, oxidative damage, and starvation (9, 12, 14, 15, 26, 43, 48, 54, 60, 61, 65). Considering that the developmental process of M. xanthus is in essence a well-orchestrated stress response to starvation, it is perhaps not too surprising that a DnaK homolog is involved in this process. It should be noted, however, that the expression of dnaK genes in other bacteria is up-regulated by heat shock or starvation (8, 14, 38, 43, 48, 54, 60, 61, 65), whereas this M. xanthus dnaK homolog (sglK) is apparently not regulated by heat shock or starvation. Instead, it is constitutively expressed during both vegetative growth and starvation (Fig. 5).

In E. coli, DnaK forms a protein complex with DnaJ and GrpE, and such a complex has been found to be involved in a variety of cellular processes, including cell motility, cell division, cell growth, phage infection, protein transport, and heat shock response (9, 12, 14, 15, 26, 43, 48, 54, 60, 61, 65). In contrast, M. xanthus sglK seems to be involved only in some specific cellular functions: the sglK mutants show no defect in cell division, cell growth, single-cell motility, heat shock response, and Mx4 phage infection, but they are defective in social motility and fruiting body formation.

It would be interesting to find out how sglK may affect these social processes of M. xanthus. The dnaK mutation causes reduced expression of the flagellar genes in E. coli (48). It is possible that SglK is involved in the regulation of the synthesis of social motility appendages in M. xanthus. The lack of such appendages may lead to defects in social motility. Since sglK encodes a homolog of a molecular chaperone, it is also conceivable that SglK in M. xanthus is directly involved in the assembly of some apparatus required for social motility. Alternatively, SglK could be involved indirectly in motility by affecting the function of proteins in the regulatory hierarchy of the social motility genes. Our preliminary results indeed indicate that sglK may negatively regulate the expression of a DnaK-like protein other than itself (data not shown). It should be noted, however, that sglK mutants still possess A motility (Fig. 1f). Whatever structure or appendage is affected by sglK mutations, either directly or indirectly, it must be unique to S motility. It is not yet known whether this DnaK homolog is directly required for fruiting body formation or whether it is the defects in social motility which then lead to the nonfruiting phenotype. The expression of sglK is not regulated by starvation, indicating that it is more likely involved in a general housekeeping function rather than specifically in fruiting body development. Future experiments will focus on the studies of cellular surface structures of sglK mutants and on further understanding the involvement of SglK in social motility and development of M. xanthus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. R. Zusman, Y. W. Han, Y. Li, P. Hartzell, and P. Youderian for very helpful discussions. We also thank Bryan Julien for kindly providing Tn5kan903.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM54666 to W. Shi and training grant 5-T32-AI-07323 to Z. Yang.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery L, Kaiser D. In situ transposon replacement and isolation of a spontaneous tandem genetic duplication. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;191:99–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00330896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardwell J C, Craig E A. Major heat shock gene of Drosophila and the Escherichia coli heat-inducible dnaK gene are homologous. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:848–852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Nutrition of Myxococcus xanthus, a fruiting myxobacterium. J Bacteriol. 1978;133:763–768. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.2.763-768.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukau B, Walker G C. Cellular defects caused by deletion of the Escherichia coli dnaK gene indicate roles for heat shock protein in normal metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2337–2346. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2337-2346.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos J M, Geisselsoder J, Zusman D R. Isolation of bacteriophage MX4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos J M, Zusman D R. Regulation of development in Myxococcus xanthus: effect of 3′:5′-cyclic AMP, ADP, and nutrition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:518–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowing D W, Bardwell J C, Craig E A, Woolford C, Hendrix R W, Gross C A. Consensus sequence for Escherichia coli heat shock gene promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2679–2683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig E A, Gross C A. Is hsp70 the cellular thermometer? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin M, Kaiser D, editors. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin M. Recent advances in the social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Geng, Y. and W. Shi. Unpublished data.

- 12.Georgopoulos C, Ang D, Liberek K, Zylicz M. Properties of the Escherichia coli heat shock proteins and their role in bacteriophage λ growth. In: Morimoto R I, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C, editors. Stress proteins in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1990. pp. 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgopoulos C, Tilly K, Drahos D, Hendrix R. The B66.0 protein of Escherichia coli is the product of the dnaK+ gene. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:1175–1177. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.3.1175-1177.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross C A. Function and regulation of the heat shock proteins. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Masgasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1382–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross C A, Straus D B, Erickson J W, Yura T. The function and regulation of heat shock proteins in Escherichia coli. In: Morimoto R I, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C, editors. Stress proteins in biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1990. pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagen D C, Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus (Myxobacterales): genes controlling movement of single cells. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;171:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus: two gene systems control movement. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;171:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen G R, Wireman J W, Dworkin M. Effect of temperature on the growth of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:561–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.561-562.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S K, Kaiser D, Kuspa A. Control of cell density and pattern by intercellular signaling in Myxococcus development. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Construction of Tn5 lac, a transposon that fuses lacZ expression to exogenous promoters, and its introduction into Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5816–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Expression of many developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus depends on a sequence of cell interactions. Genes Dev. 1987;1:840–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroos L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. Defects in fruiting body development caused by Tn5 lac insertions in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:484–487. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.484-487.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroos L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. A global analysis of developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:252–266. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuner J M, Kaiser D. Introduction of transposon Tn5 into Myxococcus for analysis of developmental and other nonselectable mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:425–429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaRossa R A, Van Dyk T K. Physiological roles of the DnaK and GroE stress proteins: catalysts of protein folding or macromolecular sponges? Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:529–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macario A J, Dugan C B, Conway de Macario E. A dnaK homolog in the archaebacterium Methanosarcina mazei S6. Gene. 1991;108:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90498-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacNeil S D, Calara F, Hartzell P L. New clusters of genes required for gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacNeil S D, Mouzeyan A, Hartzell P L. Genes required for both gliding motility and development in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:785–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McBride M J, Hartzell P, Zusman D R. Motility and tactic behavior of Myxococcus xanthus. In: Dworkin M, Kaiser D, editors. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McBride M J, Kohler T, Zusman D R. Methylation of FrzCD, a methyl-accepting taxis protein of Myxococcus xanthus, is correlated with factors affecting cell behavior. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4246–4257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4246-4257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBride M J, Weinberg R A, Zusman D R. “Frizzy” aggregation genes of the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus show sequence similarities to the chemotaxis genes of enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:424–428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride M J, Zusman D R. FrzCD, a methyl-accepting taxis protein from Myxococcus xanthus, shows modulated methylation during fruiting body formation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4936–4940. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4936-4940.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCleary W R, McBride M J, Zusman D R. Developmental sensory transduction in Myxococcus xanthus involves methylation and demethylation of FrzCD. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4877–4887. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4877-4887.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrison C E, Zusman D R. Myxococcus xanthus mutants with temperature-sensitive, stage-specific defects: evidence for independent pathways in development. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:1036–1042. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.1036-1042.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motohashi K, Taguchi H, Ishii N, Yoshida M. Isolation of the stable hexameric DnaK-DnaJ complex from Thermus thermophilus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27074–27079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakahigashi K, Yanagi H, Yura T. Isolation and sequence analysis of rpoH genes encoding sigma 32 homologs from gram negative bacteria: conserved mRNA and protein segments for heat shock regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4383–4390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson D R, Killeen K P. Heat shock proteins of vegetative and fruiting Myxococcus xanthus cells. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1100–1106. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1100-1106.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimura K, Yoshikawa H, Takahashi H. Sequence analysis of the third dnaK homolog gene in Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:2016–2017. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor K A, Zusman D R. Genetic analysis of Myxococcus xanthus and isolation of gene replacements after transduction under conditions of limited homology. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:744–748. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.2.744-748.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroder H, Langer T, Hartl F U, Bukau B. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat-induced protein damage. EMBO J. 1993;12:4137–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Segal G, Ron E Z. The dnaKJ operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: transcriptional analysis and evidence for a new heat shock promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5952–5958. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5952-5958.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi W, Zusman D R. The frz signal transduction system controls multi-cellular behavior in Myxococcus xanthus. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi W, Kohler T, Zusman D. Motility and chemotaxis in Myxococcus xanthus. In: Adolph K W, editor. Molecular microbiology techniques. Vol. 3. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi W, Kohler T, Zusman D R. Chemotaxis plays a role in the social behaviour of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:601–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi W, Zhou Y, Wild J, Adler J, Gross C A. DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE are required for flagellum synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6256–6263. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6256-6263.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi W, Zusman D R. The two motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus show different selective advantages on various surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3378–3382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimkets L J. Correlation of energy-dependent cell cohesion with social motility in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:837–841. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.837-841.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimkets L J. The myxobacterial genome. In: Dworkin M, Kaiser D, editors. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith R F, Wiese B A, Wojzynski M K, Davison D B, Worley K C. BCM Search Launcher—an integrated interface to molecular biology data base search and analysis services available on the World Wide Web. Genome Res. 1996;6:454–462. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sogaard-Andersen L, Kaiser D. C factor, a cell-surface-associated intercellular signaling protein, stimulates the cytoplasmic Frz signal transduction system in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2675–2679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Straus D, Walter W, Gross C A. DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE heat shock proteins negatively regulate heat shock gene expression by controlling the synthesis and stability of sigma 32. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2202–2209. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12a.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tilly K, Hauser R, Campbell J, Ostheimer G J. Isolation of dnaJ, dnaK, and grpE homologues from Borrelia burgdorferi and complementation of Escherichia coli mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:359–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tilly K, McKittrick N, Zylicz M, Georgopoulos C. The DnaK protein modulates the heat-shock response of Escherichia coli. Cell. 1983;34:641–646. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Varela P, Jerez C A. Identification and characterization of GroEL and DnaK homologues in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;77:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90147-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weimer, R., P. L. Hartzell, and P. Youderian. Personal communication.

- 59.Wetzstein M, Dedio J, Schumann W. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis dnaK gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2172. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickner S, Skowyra D, Hoskins J, McKenney K. DnaJ, DnaK, and GrpE heat shock proteins are required in oriP1 DNA replication solely at the RepA monomerization step. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10345–10349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wild J, Rossmeissl P, Walter W A, Gross C A. Involvement of the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE chaperone team in protein secretion in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3608–3613. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3608-3613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu S S, Wu J, Kaiser D. The Myxococcus xanthus pilT locus is required for social gliding motility although pili are still produced. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:109–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1791550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yee T, Inouye M. Reexamination of the genome size of myxobacteria, including the use of a new method for genome size analysis. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1257–1265. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1257-1265.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ziemienowicz A, Skowyra D, Zeilstra-Ryalls J, Fayet O, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. Both the Escherichia coli chaperone systems, GroEL/GroES and DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE, can reactivate heat-treated RNA polymerase. Different mechanisms for the same activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25425–25431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zuber M, Hoover T A, Dertzbaugh M T, Court D L. Analysis of the DnaK molecular chaperone system of Francisella tularensis. Gene. 1995;164:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00489-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]