Abstract

Objectives

To systematically assess the scientific literature for the prevalence of failure rate of fixed orthodontic bonded retainer (FOBR).

Method

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and prospective non-RCTs involving participants who had FOBR fitted were included. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of science, MEDLINE, and EMBASE via OVID were searched from inception to January 2023. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2 and Newcastle–Ottawa tools. The main outcome was the failure rate of FOBRs. The secondary outcome was to identify factors that can influence the failure of FOBR. Meta-analyses and sensitivity analyses were undertaken using Revman, version5.4. A random-effects model was used. Quality assessment using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Results

Thirty-four studies (25 RCTs and 9 prospective clinical studies) (3484 participants) were included in this review. The overall failure rate of bonded retainers, after excluding high-risk studies, was 35.22% (95% confidence interval [CI] 27.46–42.98). The failure rate is increased with the duration of follow up; with short-term follow-up rate 24.18% (95% CI 20.16–28.21), medium-term follow up 40.09% (95% CI 30.92–49.26), and long-term follow up 53.85% (95% CI 40.31–67.39). There is a low level of evidence to suggest there is no statistically significant difference in the failure rate of fixed retainers using direct versus indirect bonding methods, using liquid resin versus without liquid resin, and fibre-reinforced composite retainers compared to multi-stranded stainless steel retainers.

Discussion

There is low-quality evidence to suggest that the failure rate of FOBR is relatively high. There is a need for high-quality, well-reported clinical studies to assess factors that can influence the failure rate of FOBR.

Registration

CRD42021190910.

Introduction

Unwanted tooth movement after a course of orthodontic treatment can occur due to several factors including relapse which is defined as the partial or complete return of the original features of the presenting malocclusion. It can be challenging to predict and may occur many years following treatment [1, 2]. Retention procedures are considered essential following successful orthodontic treatment to maintain the teeth in the treated position. This phase of treatment is aimed at stabilization and maintenance of the achieved orthodontic correction, allowing settling of the occlusion, and preventing or minimizing subsequent unwanted tooth movement [3].

It is well known that certain features of malocclusion have a high relapse potential including severe pre-treatment contact point displacement, spaced dentition, rotated teeth [4, 5], and periodontally compromised teeth with bone loss [6, 7]. Moreover, some orthodontic tooth movements may be inherently unstable and more prone to relapse such as changes in the antero-posterior lower incisor position [8], expansion of lower inter-canine width [9, 10], and closure of anterior open bites [11]. Fixed Orthodontic bonded retainers (FOBRs) are commonly used in cases which have a higher potential of relapse. However, to date there is no clear evidence as to the best type of retainer.

FOBR can be preferred for several reasons including good aesthetics, minimal interference with speech, and less reliant on compliance. In the last decade, a Cochrane systematic review reported that there is weak evidence to suggest that prolonged use of a bonded retainer can decrease the risk of lower labial segment relapse [2]. Despite its increasing popularity, there are a number of reported disadvantages including time-consuming placement and technique sensitive, increased plaque or calculus accumulation, and risk of failure of the fixed retainer resulting in inadvertent tooth movement [3].

FOBR vary in their wire type (solid or multistrand), bonding protocols, and design including the number of teeth bonded. Higher failure rates have been shown to occur in the maxilla compared to the mandible, especially when there is an increased overbite [12, 13].

Rationale

Despite the fact that many studies have been published on FOBR comparing different wires, bonding materials, and construction methods synthesis of the available evidence to determine prevalence of the failure rate of maxillary and mandibular bonded retainers is lacking from the literature. Previous studies have attempted to review the risk of bonded retainer failure, however, due to the lack of high-quality evidence they were unable to do so [2, 14–20]. The prevalence of bonded retainer failure therefore remains an important clinical question.

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was to assess the prevalence of failure of both maxillary and mandibular FOBRs. The failure rate is defined as breakage, fracture, loosening, or bonding failure of the retainer. Unwanted tooth movement due to failure of the FOBR was not assessed in this review. The secondary objective was to identify factors that can influence the risk of failure of FOBRs.

Material and methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO database (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ Protocol: CRD42021190910) before study commencement and was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (www.prisma-statement.org). The PRISMA checklist for our work is available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

The following selection criteria were applied:

Study design: randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and prospective controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were considered eligible for inclusion in this review. No language or date restrictions were applied.

Participants: patients of any age who completed a course of orthodontic treatment, with either fixed or removable appliances, and retained using FOBRs.

Intervention: all types of bonded retainers were considered eligible, irrespective of the wire type, bonding materials, and the number of teeth bonded.

Outcome: primary outcome for this review was failure rate of maxillary and/ or mandibular FOBRs with respect to loosening, breakage, and bond failure. There were no limits on the observation period. Secondary outcome was to assess the influence of factors on the failure of FOBRs including type retainer wire, adhesive, and bonding technique.

Exclusion criteria: studies involving only removable retainers or auxiliary procedures for example interproximal reduction or surgical adjunctive procedures were excluded. Animal studies and case reports were excluded.

Information sources, search strategy, and study selection

Electronic systematic literature searches were performed in multiple databases: The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library January 2023 Issue 1), Web of science, MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to January 2023), and EMBASE via OVID (1980 to January 2023) (Supplementary Table 3). No language restrictions were applied. Unpublished clinical trials were accessed electronically on Clinical Trials.gov (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov), the National Research Register (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk), and Pro-Quest Dissertation Abstracts and Thesis database (http://pqdtopen.proquest.com). We contacted the authors of registered RCTs to help identify any unpublished studies. Duplicates were identified in Endnote and removed.

Reference lists of all eligible studies were hand searched for additional studies. Three authors (S.A., S.L., and A.E.) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts of identified studies to check for eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consultation with a fourth assessor (E.B).

Data items and collection

Data extraction of included studies were performed independently and in duplicate by two authors (S.A. and A.E.). Data were extracted using a customized data collection form. We attempted to contact the first-named authors of included studies by email where we required additional information or when data was missing. We requested further information relevant to the review that was not apparent in the published work.

Data extracted included (i) study design; (ii) sample size, demographic data, and study setting (iii) type of retainers used, dimensions of wire and composite used; (iv) teeth which the bonded retainer was bonded to; (v) outcome assessed; (vi) follow-up period; and (vii) failure rate of bonded retainer.

Risk of bias/quality assessment in individual studies

Risk of bias was assessed independently and in duplicate for each of the individual studies by three authors (S.A., S.L., and E.B.) as specified in the Cochrane Handbook [21]. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a fourth author (A.E). Risk of bias of RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias 2.0 tool assessing six domains: the randomization process, deviation from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall bias [22]. Non-randomized prospective clinical trials were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa analysis [23]. The following domains were assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa analysis: representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non-exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of the study, comparability of cohort in the basis of the design or analysis, assessment of outcome, was follow up long enough for outcome to occur, and adequacy of follow up of cohorts.

Data synthesis and summary measures

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed on the basis of the types of participants, the interventions, and the outcome variables and measures. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Chi² and I2 tests. Heterogeneity was considered to be significant for the Chi² test when P < .10. I² values of 30% to 60% indicated moderate heterogeneity, and > 60% substantial heterogeneity [21].

The primary outcome was pooling the proportion of failures for all studies combined, along with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The DerSimonian–Laird random-effects method was used, regardless of the degree of heterogeneity between the study results. Standard deviation was calculated from proportion [24]. We calculated mean differences with 95% CI for continuous data and risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI for dichotomous data. We contacted the corresponding authors of trials for original data where necessary. The level of evidence was applied to the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) criteria and reported.

Risk of bias across studies

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots if there were more than 10 studies assessing similar interventions identified for inclusion, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [21].

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analysis was undertaken to compare the findings from the pooled RCTs after excluding high-risk studies. Meta-analyses and sensitivity analyses were undertaken using Revman 5.4.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

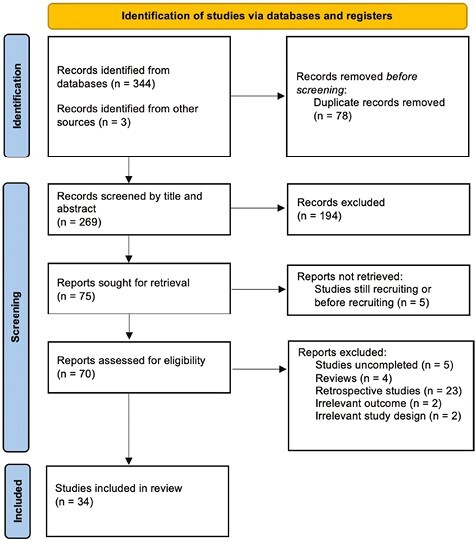

A total of 269 studies were identified from electronic searching and hand-searching reference lists after the removal of duplicates (Fig. 1). Potentially relevant abstracts were screened, and full-text articles were retrieved (n = 70). A total of 34 studies (Table 1) met the inclusion criteria [12, 25–57]. Thirty-six studies were excluded due to the studies being retrospective in design (Supplementary Table 3). Of the 34 included studies, 25 were RCTs [25, 27–31, 33–35, 37–40, 42, 43, 45–52, 55, 56] and 9 were prospective clinical trials [12, 26, 32, 36, 41, 44, 53, 54, 57]. The study design, participants, intervention, outcome, and follow-up period of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| No. | Study | Study design | Participants and setting | Interventions | Outcome | Follow-up Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Artun et al. 1997 | Prospective study |

n = 49 University of Washington, USA |

(i) Thick plain wire; 0.032 inch; mandible: only canines; n = 11 (ii) Thick spiral wire; 0.032 inch; mandible: only canines; n = 13 (iii) Thin, flexible spiral wire; 0.0205 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 11 (iv) Removable retainers; n = 14 |

Retainer failure | 3 years |

| 2. | Bazargani 2012 | RCT |

n = 52 (26 M, 26 F) Mean age 18.3 ± 1.3 years Orebro County Council, Sweden. |

(i) Resin, optibond FL; n = 26 (ii) Non-resin tetric evoflow; n = 26 Mandibular canine to canine Wire: 0 0.0195 inch multi-stranded penta-one wire |

Failure rate, incidence of retainer loss or breakage failure rate | 2 years |

| 3. | Taner 2012 | RCT |

n = 66 (52 F, 14 M) Mean age: 15.96 ± 3.21 in the direct group 19.44 ± 6.79 in the indirect groups University of Hacettepe, Turkey |

(i) Eight-braided flattened stainless steel; 0.022 inch −0.016 inch; mandible: all 6; direct bonding; n = 32 (2) Eight-braided flattened stainless steel; 0.022 inch −0.016 inch; mandible: all 6; indirect bonding; n = 34 Composite: phase II (CC) |

Failures of retainers as a result of debonding, fracture, debonding and fracture, or retainer loss | 6 months |

| 4. | Bolla et al. 2012 | RCT |

n = 85 (29 male, 56 female) Mean age: male 23.7 years, female 21.9 years |

(i) Glass fibre reinforced; maxilla: all incisors (n = 14); mandible: all 6 (n = 34) (ii) Multi-stranded wire, 0.0175 inch; maxilla: all incisors (n = 18); mandible: all 6 (n = 32) Composite: ENA bond LC primer and flowable composite (LC) |

The total number of detachments or bond failure and breakages | 6 years |

| 5. | Lee 2009 | Prospective study |

n = 300 Mean age: 15.6 ± 2.7 years Private practice, Canada. |

(i) Multi-stranded stainless steel; 0.0175 inch; straight wire; maxilla and mandible: all incisors or all 6; n = 153 (ii) Black Australian stainless steel; 0.016 inch; V-loop design; maxilla and mandible: all incisors or all 6; n = 147 Composite: Transbond LR (LC) |

Wire fractures, detachment rate due to bond failure | 6 months |

| 6. | Forde et al. 2018 | RCT |

n = 60 (15 F and 15 M with median age 16 in BR) (12 M and 18 F with median age of 17 in VFR) St Luke’s Hospital, York Hospital, and Leeds Dental Institute; UK. |

(i) BR (0.195 in three-stranded twist flex SS wire); n = 30 (ii) VFR; n = 30 Composite: Trasbond XT |

Retainer survival | 1 year |

| 7. | Gunay 2018 | RCT |

n = 120 Mean age 15.7 years (17 M and 43 F) in extraction group Mean age of 16.2 years (20 M and 40 F) in non-extraction group Ondokuz Mayıs University, Turkey |

(i) Extraction and 0.0175 in 60 stranded SS (n = 60) (ii) Non-extraction and 0.0195 in dead soft coaxial wire (n = 60) Composite: Trasbond XT |

Failure rate | 1 year |

| 8. | Ardeshna 2011 | Prospective study |

n = 51 University of Connecticut, USA |

(i) Maxilla: fibre-reinforced thermoplastic—FRP formula A; 0.53 mm; n = 1 (ii) FRP formula A; 1.02 mm; n = 1 (iii) FRP formula B; 0.53 mm; n = 6 (iv) FRP formula B; 1.02 mm; n = 8 (v) Mandible: fibre-reinforced thermoplastic—FRP formula A; 0.53 mm; n = 15 (vi) FRP formula A; 1.02 mm; n = 6 (vii) FRP formula B; 0.53 mm; n = 10 (viii) FRP formula B; 1.02 mm; n = 29 |

Retainer failure | 24 months |

| 9. | Zachrisson 1977 | Prospective study |

n = 43 Age: 14–17 years University of Oslo, Norway |

(i) Heat-treated and polished blue Elgiloy; 0.036 inch or 0.032 inch; mandible: only canines; held with finger during placement; n = 22 (ii) Heat-treated and polished blue Elgiloy; 0.036 inch or 0.032 inch; mandible: only canines; ligated during placement; n = 21 Composite: Concise (CC) |

Retainer loosening | 12 months |

| 10. | Salehi et al. 2013 | RCT |

n = 142 (59 male, 83 female) Age: 14–28 years |

(i) Polyethylene woven ribbon; maxilla and mandible: all 6; n = 68 (ii) Flexible spiral wire; 0.0175 inch; maxilla and mandible: all 6; n = 74 Composite: Fluoro Bond (sealant) and Heliosit Orthodontic (LC) |

Bond failure | 18 months |

| 11. | Talic 2016 | Prospective study |

n = 100 (37 F and 13 M in first group; 30 F and 20 M in second group) Mean age 21.4 ± 5.3 years for first group Mean age 20.48 years for second group King Saud University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia |

(i) Fixed canine to canine retainers with a light-cured nano-hybrid composite based on nano-optimized technology (Tetric-N-Flow, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) (ii) Fixed canine-to-canine mandibular and maxillary lingual retainers that were bonded with a light-cured LV composite (Transbond Supreme LV, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, California, USA) |

Failure rate | 6 months |

| 12. | Tacken et al. 2010 | RCT |

n = 184 patients (90 M, 94 F; 169 analysed) Mean age: 14 years University of Brussels, Belgium |

(i) Glass fibre reinforced (GFR500) maxilla: lateral incisor to lateral incisor (n = 45); mandible: all 6 (n = 45) (ii) Glass fibre reinforced (GFR1000); maxilla: lateral incisor to lateral incisor (n = 48); mandible: all 6 (n = 48) (iii) Six-stranded coaxial wire, 0.0215 inch; maxilla: lateral incisor to lateral incisor (n = 91); mandible: all 6 (n = 91) Composite: Excite and Tetric Flow (LC) |

Bond failure Retainer failure |

24 months |

| 13. | Egli et al. 2017 | RCT |

n = 64 Mean age 19.8 years in direct, 17.2 in indirect 61% F and 39% F in direct group 50% M and 50% F in indirect University of Geneva, Switzerland. |

(i) Direct bonding; n = 30 (ii) Indirect bonding; n = 30 Composite: direct bonding—Trasbond LR (LC), Indirect—maximum cure A and B (CC) Wire: Multi-stranded SS wire 0.0215 inch Mandibular laterals to laterals or canine to canine |

Failure rate | 2 years |

| 14. | Bovali 2014 | RCT |

n = 60 patients Mean age: 19.8 years (direct bonding), 17.2 years (Indirect bonding) University of Geneva, Switzerland. |

(i) Multi-stranded steel wire 0.0215 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 29; direct bonding (ii) Multi-stranded steel wire 0.0215 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 31; indirect bonding Composite: direct bonding, Transbond LR (LC); indirect bonding, Maximum Cure A and B (CC) |

Retainer failure | 6 months |

| 15. | Tang et al. 2013 | RCT |

n = 45 22 retainers in 18 patients 31 retainers in 27 patients Karolinska Institute and Uppsala County Council, Sweden |

(i) Transbond LR composite paste with liquid resin; n = 20 (ii) Liquid resin excluded; n = 20 Wire: 0.0215-inch multi-stranded wire Maxilla: all incisors; mandible: all 6 |

Failure rate | 5 years |

| 16. | Pandis et al. 2013 | RCT |

n = 220 (Median age, 16 years; interquartile range, 2 years; range, 12–47 years) Private practice, Greece. |

(i) Tru-Chrome multi-stranded wire; 0.022 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 110; Reliance (CC) (ii) Tru-Chrome multi-stranded wire; 0.022 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 110; Flow Tain (LC) Composite: Reliance (CC) and Flow Tain (LC) |

Bond failure | 3.64 years |

| 17. | Rose et al. 2002 | RCT | 20 patients (8 F, 12 M) Mean age 22.4 years Freiburg University, Germany |

(i) Polyethylene woven ribbon; mandible: all 6; n = 10 (ii) Multi-stranded steel wire; 0.0175 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 10 Composite: Heliosit Orthodontic (LC) |

Resin fracture or Retainer loosening | 2years |

| 18. | Arash et al. 2020 | RCT |

n = 260 (44 M and 68 F) Age: 13–30 years (20 ± 4.35 years) Babol University of Medical Sciences, Islamic Republic of Iran |

(i) 0.0175” twist flex wire (ii) Single stranded ribbon titanium Composite:Transbond XT (Mandibular anterior teeth) |

Failure rate Detachments, time of debonding, side effects |

2 years |

| 19. | Kartal et al. 2020 | RCT |

n = 52 (13 F and 13 M in first group; 19 F and 27 M in second group) Mean age 15.65 ± 2.17 18.42 ± 5.17 Private Practice, Turkey |

(i) Memotain retainers (CAD-CAM technology) 0.014” (ii) 0.0215” five-stranded retainers Composite:Transbond XT |

Success rate | 6 months |

| 20. | Scribante 2011 | RCT |

n = 34 patients (9 male, 25 female) Mean age: 14.3 years University of Pavia, Italy |

(i) Multi-stranded Stainless steel; 0.0175 inch; mandible: all 6, n = 17 (ii) Polyethylene ribbon-reinforced resin composite; mandible: all 6; n = 15 Composite: Transbond XT (LC) |

Bond failure | 12 months |

| 21. | Kramer et al. 2020 | RCT |

n = 104 (52 F and 52 M) Mean age 17.1 years in VFR Mean age 17.1 year in BR Orthodontic Clinic in Gavle, Sweden. |

(i) Cuspid to cuspid retainer (ii) VFR Wire: 0.8 Hard Remanium wire Composite:Tetric Flw composite |

Failure rate | 18 months |

| 22. | Gokce 2019 | Prospective study |

n = 100(61 F and 39 M) Age: 16.5–18 years Başkent University, Turkey |

(i) 0.0215 “MSW direct technique 0.0125 MSW indirect (ii) 0.0175 “MSW direct 0.0175 “MSW indirect Removable essix Transbond XT primer, 3M Unitek |

Failure rate | 6 months |

| 23. | Pop et al. 2018 | Prospective study |

n = 53 Age: 11–53 years Private clinic, Romania |

(i) 0.0175 inch Round fixed retainers (ii) 0.010–0.022-inch Flat wire retainers |

Success rate | 6 months |

| 24. | Sobouti et al. 2016 | RCT |

n = 150 Mean age 18 ± 3.6 years 23 M and 24 F in FRC splint 17 M and 24 F in FSW 20 M and 25 F in TW Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Iran |

(i) 0.0175-inch FSW (ii) FRC splint (iii) Twisted 2—0.009-inch dead soft wire Composite: Two layers of light-curable primer (Ormco, Orange, CA, USA) |

Failure rate, detachment, breakage, or distortion | 2 years |

| 25. | Stormann 2002 | RCT |

n = 103 Age: 22.4 ± 9.7 years Age: 13–17 years Orthodontic practice, Germany |

(i) Coaxial stainless steel 0.0215 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 36 (ii) Coaxial stainless steel 0.0195 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 30 (iii) Prefabricated; mandible: only canines; n = 32 Composite: Heliosit Orthodontic (LC) or Concise (CC) |

Bond failure | 2 years |

| 26. | Sfondrini 2014 | RCT |

n = 87 (52 F and 35 M) Age: 24 years (14–62 years) University of Pavia, Italy |

(i) Glass fibre reinforced; mandible: all 6; n = 40 (ii) Multi-stranded wire; 0.0175 inch; mandible: all 6; n = 47 Composite: Transbond XT (LC) |

Detachments of retainers from the teeth | 12 months |

| 27. | Nagani et al. 2020 | RCT |

n = 56 Age 20.88 ± 3.45 FRC 22.15 ± 3.68 MSW 4 M and 22 F in FRC 4 M and 22 F in MSR Dow University of Health Sciences, Pakistan |

(i) Fiber reinforced retainers; n = 27 (ii) Multi-stranded retainers; n = 27 Composite: Flowable composite resin (3 M ESPE) |

Retainer failure | 12 months |

| 28. | Shim 2022 | RCT |

n = 81 9 M,7 F, age median 16.5 in CAD/CAM 4 M, 12 F, median age 15.8 in Lab 5 M, 9 F, age median 15.2 in traditional group Saint Louis University, Missouri |

(i) CAD/CAM; n = 16 (ii) Lab; n = 16 (iii) Traditional; n = 14 |

Stability, failure of retainer | 6 months |

| 29. | Wegrodzka et al. 2021 | RCT |

N = 133 patients Median age, 24.6 years; 25th percentile, 17.2 years; 75th percentile, 32.4 years; minimum, 15.1 years; maximum, 49.8 years Private practice, Poland |

0.0215-inch stainless-steel three-strand RT wire retainer (Ortho Organizers, Lindenberg, Germany) 0.0265-inch 3 0.0106-inch eight-strand Bond-a-Braid wire retainer (Reliance Orthodontic Products, Itasca, Ill) |

Retainer failure, periodontal index, bleeding on probing, plaque index, gingival index, and probing depth. | 2 years |

| 30. | Cornelis et al. 2022 | RCT |

N = 64 participants University of Geneva, Switzerland |

Indirect bonding 26 Direct bonding 26 0.0215-inch multi-stranded stainless steel wire Transbond LR Light Cure Adhesive (3M, Monrovia, California) composite. |

Survival rate, the inter-canine and inter-premolar distances, and the observation of unexpected posttreatment changes | 5 years |

| 31. | Gera et al. 2022 | RCT |

N = 181 patients 98 in Centre 1, 83 in Centre 2 Aarhus University, Denmark University of Oslo, Norway. |

CAD/CAM group (n = 90) Conventional group (n = 91) |

Stability, retainer failures and patient satisfaction. | 6 months |

| 32. | Jowett et al. 2022 | Multicentre RCT |

N = 68 patients Leeds Dental Institute, St Luke’s Hospital, and Beverley Orthodontic Centre; UK |

Upper and lower Memotain® bonded retainers (n = 34) Upper and lower Ortho-FlexTechTM bonded retainers (n = 34) Separate etch and bond along-side Transbond LR (3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) resin-based composite: |

Stability of the inter-canine width and alignment of the labial segments, failure rate, patient satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness. | 6 months |

| 33. | Danz et al. 2022 | Prospective cohort study |

N = 200 participants Median age 14.7 (Range 11.1–57.0) University of Bern, Switzerland. |

0215 inches MW with separate curing of resin and composite (n = 200) 016 inches 022 inches SS wire with simultaneous curing of resin and composite (SS1C) (n = 200) 016 022 inches SS wire with separate curing of resin and composite (SS2C) (n = 200) |

Retention success, emergency, detachment, and retainer failure. | 1 year |

| 34. | Cokakoglu et al. 2023 | RCT |

N = 100 patients 70 females and 30 males Pamukkale University, Turkey |

Group 1, direct bonding (DB) with two-step adhesive (n =25) Group 2, DB with one-step adhesive (n = 25) Group 3, indirect bonding (IDB) with two-step adhesive (n = 25) Group 4, IDB with one-step adhesive (n = 25) The fixed retainer, a 0.0215-inch, five-strand stainless steel wire (Pentaflex; GC Orthodontics America Inc, Alsip, Ill) Bonded with the direct or indirect method using either the primer integrated one-step (GC Ortho Connect Flow; GC Corp, Tokyo, Japan) or two-step (conventional) retainer adhesive (Transbond LR; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, California) |

Plaque index, gingival index, and calculus index, failure rate. | 12 months |

A total of 3484 participants with 4540 FOBR were included in the 34 studies, with participants age ranging from 9 to 60 years. Out of the 34 included studies in this review 6 were conducted in Switzerland [29, 31–33, 43, 56], 5 studies were conducted in Turkey [30, 36, 37, 39, 54], 3 studies in Italy [28, 47, 48], USA [12, 26, 49] and Iran [25, 46, 50], 2 studies were conducted in Germany [45, 51], Sweden [27, 40], Saudi Arabia [44, 53], Norway [35, 57], and UK [34, 38], and 1 study in China [55], Belgium [52], Canada [41], and Pakistan [42]. The majority of studies included (n = 26) were conducted in a university hospital setting where the participants were treated by both specialist orthodontists as well as postgraduate students under supervision. Eight studies [26, 39, 41, 43, 44, 51, 55, 56] were conducted in an orthodontic practice setting. The percentage of participants lost to follow up in the studies ranged from 0% to 38%. Interventions evaluated in the identified studies included: nine studies comparing multi-stranded wire (MSW) versus fibre-reinforced retainers [25, 26, 28, 42, 45, 46, 48, 50, 52], nine studies comparing different dimensions of wire [12, 19, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41, 44, 51], six studies comparing direct versus indirect bonding [29–31, 33, 36, 54], three studies comparing different types of composite bonding material [30, 47, 53], three studies comparing CAD/CAM versus lab made fixed retainers [35, 38, 49], two studies comparing bonding with liquid resin versus without liquid resin composite [55, 57], two studies assessing vacuum formed retainer verses bonded retainers [34, 40], and one study comparing light cured and chemical cure composite [43].

The failure rate of FOBR was assessed using different criteria and measurements; retainer failure [30–32, 35, 38], debonding rate [32, 44, 48], fracture in either the wire or composite with or without partial or total loosening of the retainer from the teeth [12, 26, 28, 29, 41, 45, 46, 51] and incidence of retainer loss or breakage [25, 27, 28, 36, 39, 47, 50, 53]. All 34 studies reported failure rate of mandibular retainers, with 9 studies reporting failure rate of both maxillary and mandibular retainers [26, 28, 34, 35, 38, 44, 46, 52, 53]. Nine studies had a short follow-up period of 6 months [29, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 49, 53, 54], 22 studies had a medium-term follow-up period of between 1 and 4 years [12, 25–27, 30, 33, 34, 37, 38, 40, 42–48, 50–52, 57], and 3 studies had a long-term follow-up period of 5–6 years [28, 31, 55].

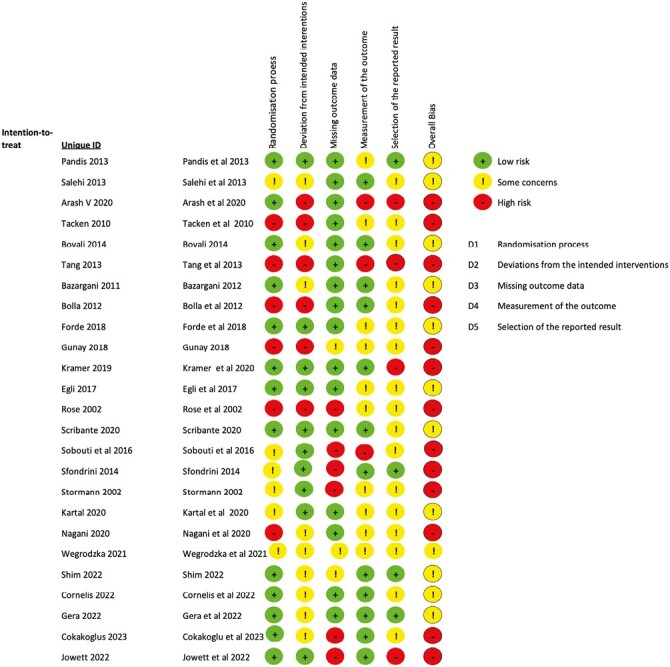

Risk of bias in included studies

None of the included studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in all domains. Of the 25 RCTs included 12 studies were assessed as having some concerns [12, 27, 29, 31, 33–35, 43, 46, 47, 49, 56] due to lack of information on allocation concealment, potential bias in the randomization process, and attrition bias. Thirteen studies had a high overall risk of bias [25, 28, 30, 37, 38, 40, 42, 45, 48, 50–52, 55] due to issues with allocation concealment, lack of blinding of the participants, and outcome assessors and attrition bias (Fig. 10). Among the nine included non-RCT prospective studies, one study was rated as high quality [12], six were rated as fair [26, 32, 36, 41, 44, 54], and two were assessed as poor-quality studies [53, 57] due to lack of information on baseline characteristics and the presence of potential confounding factors (Table 2).

Figure 10.

Risk of bias for RCTs.

Table 2.

Risk of bias summary table for non-RCT.

| No. | Representativeness of the exposed cohort (*) | Selection of the non-exposed cohort (*) (Drawn from same community as exposed) | Ascertainment of exposure (*) On Secure record (study Model) |

Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study (*) | Comparability of cohorts in the basis of the design or analysis (**) | Assessment of outcome (*) | Was follow up long enough for outcomes to occur (*) | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts (*) | Overall rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Artun et al. 1997 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding * |

* 3 years |

* | 7* Good quality |

| 2.Taner 2012 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | Only 6/12 | * | 5* Fair quality |

| 3. Lee 2009 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | Only 6/12 | No statement | 4* Fair quality |

| 4.Ardeshna 2011 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | * Baseline, 1 week, 1 month, 3month interval ? 22 censored |

* | 6* Fair quality |

| 5.Zachrisson 1977 | No description | No description | ? No description |

* | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | * | No statement | 2* Poor quality |

| 6.Talic 2016 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | Only 6 months | No statement | 4* Fair quality |

| 7. Gokce 2019 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | Only 6 months | * | 5* Fair quality |

| 8. Pop et al. 2018 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | * 1 year |

No statement | 6* Fair quality |

| 9. Danz et al. 2022 | * | * | * | * | Did not control for confounders | No blinding | * 1 year |

No statement | 5* Fair quality |

Results of individual studies, meta-analysis, and additional analyses

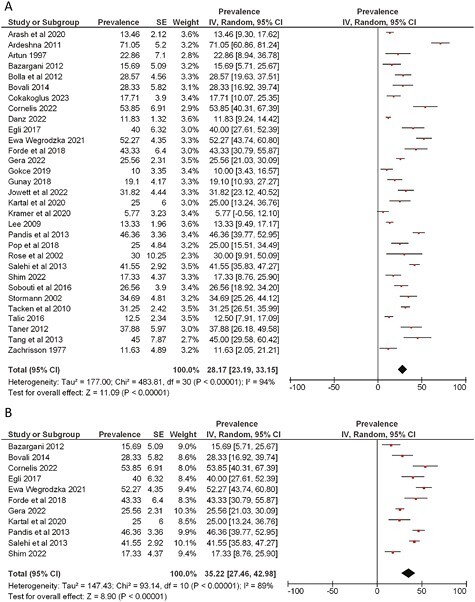

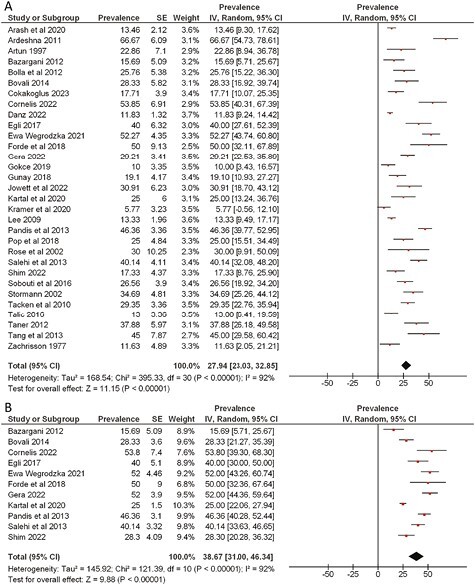

Prevalence of failure rate of fixed orthodontic bonded retainers

Thirty-one studies identified for inclusion assessed the failure rate of FOBR with the whole retainer as the unit of assessment [12, 25–41, 43–46, 49–57]. Three studies [42, 47, 48] used teeth as the unit of assessment and therefore were excluded from the main meta-analysis. The 31 studies [12, 25–41, 43–46, 49–57] included 22 RCTs (10 RCTs rated as high risk of bias and 12 RCTs rated as some concerns) and 9 non-RCTs (1 prospective study was rated as reasonably high quality, 6 studies were rated as fair, and 2 studies were rated as poor quality) with 4241 FOBR. The overall pooled failure rate of FOBR in both maxillary and mandibular arches was estimated at 28.17% (95% CI 23.19–33.15; I2 = 94%; 31 studies) (Fig. 2). The GRADE of evidence was categorized as very low quality. A random-effects model was used to account for the between study differences. This result, however, should be viewed with caution due to the high statistical heterogeneity evident and the high risk of bias in some of the included studies. Following a sensitivity analysis, excluding the non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs, a slight increase in the prevalence of failure was estimated at 35.22% (95% CI 27.46–42.98, I2 = 89%: 22 studies) (Fig. 2). The GRADE of evidence was categorized as very low quality (Supplementary Table 4). This reported difference of 7.05% is clinically insignificant indicating that the inclusion of the high risk of bias studies did not significantly influence the mean failure rate.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the failure rate with 95% CI of (A) all the included studies and (B) all the low or some concern RoB RCT studies.

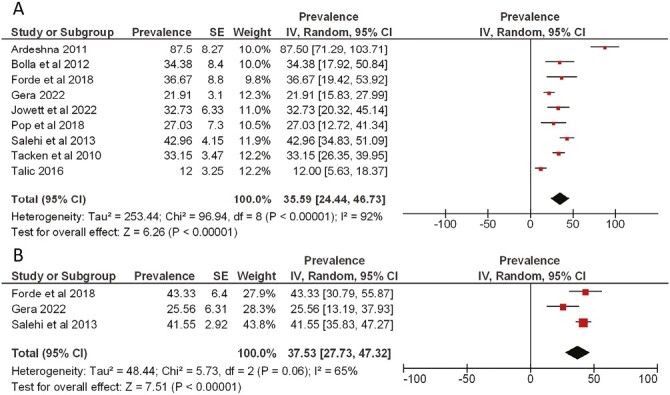

Maxillary fixed orthodontic retainers

A total of nine studies including six RCTs (three rated as high risk of bias and three rated as some concerns) and three non-RCTs (two rated as fair quality and one poor quality prospective study) with 774 FOBR [26, 28, 34, 35, 38, 44, 46, 52, 53] assessed the failure in the maxillary arch. The pooled failure rate of maxillary FOBR was 35.59% (95% CI 24.44–46.73: I2 = 92%, 9 studies) (Fig. 3). The GRADE of evidence was categorized as very low quality (Supplementary Table 4). Due to the substantial heterogeneity between the studies and the high risk of bias in some of included studies this finding should be interpreted with caution. Sensitivity analysis undertaken with exclusion of non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs demonstrated a similar prevalence of bonded retainer failure (37.53% [95% CI 27.73–47.32: I2 = 65%, 6 studies]) (Fig. 3). The GRADE of evidence was categorized as low quality. This reported difference of 1.93% is clinically insignificant, indicating that the inclusion of the high risk of bias studies did not significantly influence the mean failure rate.

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the failure rate of maxillary bonded retainer with 95% CI of (A) all the included studies and (B) all the low or some concern RoB RCT studies.

Mandibular bonded fixed retainers

A total of 31 studies with 3467 fixed retainers assessed the failure rate of mandibular retainers. These included 22 RCTs (12 RCTs rated as high risk of bias and 10 as some concerns) and 9 non-RCTs (1 prospective study rated as reasonably high quality, 6 studies as fair quality, and 2 studies as poor quality) [12, 25–41, 43–46, 49–57]. The pooled prevalence of mandibular fixed retainer failure was estimated to be 27.94% (95% CI 23.03–32.85; I2 = 92%, 31 studies) (Fig. 4). The GRADE of evidence however was categorized as very low quality (Supplementary Table 4) and substantial statistical heterogeneity was evident between the studies. Sensitivity analysis excluding non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs demonstrated an increase in the prevalence of failure (38.67% [95% CI 31.00–46.34, I2 = 92%: 22 studies]) (Fig. 4). This reported difference of 10.73% can be considered clinically significant indicating that the inclusion of the high risk of bias studies significantly influenced the mean failure rate.

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the failure rate of mandibular bonded retainer with 95% CI of (A) all the included studies and (B) all the low or some concern RoB RCT studies.

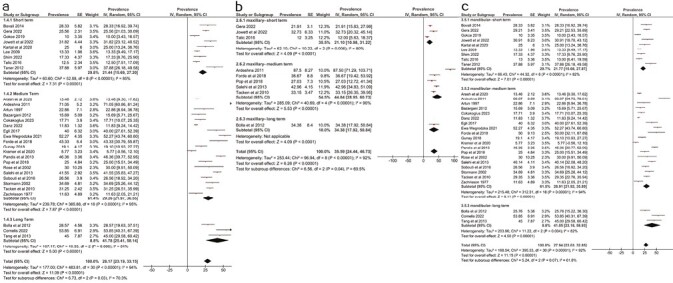

Duration of follow-up period

The follow-up period varied amongst the studies from as short as 6 months up to 6 years. In the current review we decided to sub-categorize the meta-analysis of the failure rate of the bonded retainer into short-term follow up (up to 12 months), medium-term follow up (1–4 years), and long-term follow up (more than 4 years).

Short-term (up to 1 year) follow up

Nine studies including six RCTs (three studies rated as high risk and three studies rated as some concerns) and three non-RCTs (two fair quality and one poor quality rated prospective clinical study) with 1299 FOBR assessed failure rate with a short-term follow-up period of 6–12 months [29, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 49, 53, 54]. The pooled failure rate in both arches combined in the first year following placement was estimated at 21.44% (95% CI 15.69–27.20; I2 = 85%; 9 studies) (Fig. 5). When assessing the individual arches, the short-term failure rate of maxillary bonded retainers was 21.10% (95% CI 10.98–31.22; I2 = 80%; 3 studies) (Fig. 5) and mandibular retainers was found to be 21.77% (95% CI 15.68–27.87; I2 = 82%;8 studies) (Fig. 5). GRADE for all evidence was classified as very low quality. Following a sensitivity analysis, excluding the non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs, the prevalence in the failure rate of both arches combined, maxillary arch, and mandibular arch in the first year following placement was estimated as 24.18% (95% CI 20.16, 29.21; I2 = 10%; 4 studies), 21.91% (95% CI 15.83–27.99; 1 study) and 25.02% (95% CI 19.10–30.94; I2. = 32%; 4 studies) respectively (Fig. 6). The heterogeneity of both the overall failure rate and the mandibular bonded retainer failure rate decreased. The GRADE of evidence was classified as moderate and low quality respectively (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing the failure rate of bonded retainer after short-term, medium-term, and long-term follow up with 95% CI reporting (A) overall failure rate, (B) maxillary bonded retainer failure rate, and (C) mandibular bonded retainer failure rate.

Figure 6:

Forest plot showing the failure rate of bonded retainer after short-term, medium-term, and long-term follow up with 95% CI in low or some concern RoB studies reporting (A) overall failure rate, (B) maxillary bonded retainer failure rate, and (C) mandibular bonded retainer failure rate.

Medium-term (1–4 years) follow up

Nineteen studies including 14 RCTs (7 studies rated as high risk of bias and 7 studies rated as some concerns) and 5 non-RCTs (1 high quality, 3 fair quality, and 1 poor quality rated prospective study) with 2752 FOBR assessed a follow-up period of 1–4 years [12, 25–27, 30, 32–34, 37, 40, 41, 43–46, 51, 52, 57]. The pooled medium-term failure rate of FOBR in both arches was 29.26% (95% CI 21.97–36.55; I2 = 95%; 19 studies) (Fig. 5). When assessing the individual arches, the medium-term failure rate of maxillary bonded retainers was 44.84% (95% CI 28.95–60.73; I2 = 90%, 5 studies) (Fig. 5) and 28.91% (95% CI 21.92–5.89; I2 = 94%, 19 studies) (Fig. 5) for mandibular FOBR.

Following a sensitivity analysis, excluding the non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs, a marked increase was evident in the medium-term failure rate when assessing both arches combined, a slight decrease was found in the maxillary arch and a marked increase in the mandibular arch with failure rates of 40.09% (95% CI 30.92–49.26; I2 = 85%;6 studies), 41.07% (95% CI 35.63–6.50; 2 studies) and 45.60 (95% CI 40.83–50.37; I2. = 23%; 6 studies), respectively (Fig. 6). GRADE for all evidence was classified as very low quality (Supplementary Table 4).

Long-term (5–6 years) follow up

Three RCTs (two rated as high risk of bias and one rated as some concern) with 190 participants assessed the failure rate of fixed retainers with a follow-up period of 5–6 years [28, 31, 55]. The pooled estimate demonstrated a failure rate of 41.78% (95% CI 25.41–58.14; I2 = 81%, 3 studies) (Fig. 5). When assessing the individual arches, the failure rate of maxillary FOBR was 34.38% (95% CI 17.92–50.84; 1 study) (Fig. 5) and 41.05% (95% CI 23.18–58.93; I2 = 82%, 3 studies) (Fig. 5) for mandibular FOBR.

Following a sensitivity analysis, excluding non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs, a marked increase in the prevalence of long-term mandibular arch failure was estimated at 53.85% (95% CI 40.31, 67.39; 1 study) (Fig. 6). It was not possible to pool the maxillary arch long-term failure rate prevalence after excluding non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs. GRADE for all evidence was classified as very low quality (Supplementary Table 4).

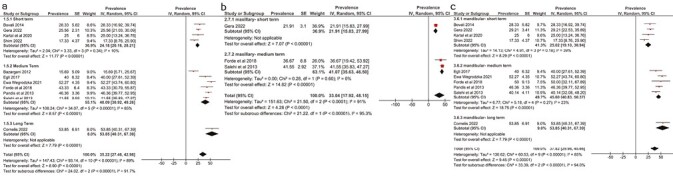

Effects of intervention

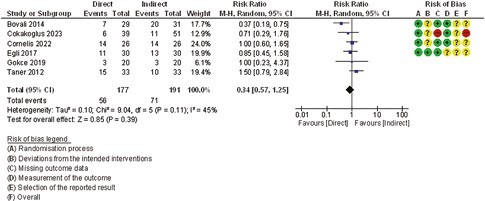

Direct versus indirect bonding

Six studies (three RCTs [29, 31, 33] rated as some concerns, one RCT [30] rated as high risk, and two non-RCTs [36, 54] rated as fair quality) with 368 participants compared direct verses indirect bonding failure rates. No statistically significant difference in retainer failure was found between direct and indirect bonding with a RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.57–1.25; P = 0.39; I2 = 45%, 6 studies) (Fig. 7). The GRADE of evidence was classified as low quality (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 7:

Comparison 1. Failure rate of bonded fixed retainer (direct bonding vs indirect bonding).

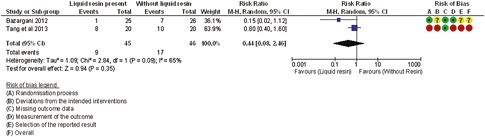

Liquid resin present versus without liquid resin

Two RCTs (one study rated as some concern [27] and one study rated as high risk of bias [55]) with 91 FOBR compared using composite with and without resin. No statistically significant difference in retainer failure between resin and non-resin composites was evident (RR 0.44 [95% CI 0.06–2.95; P = 0.35; I2 = 58%, 2 studies]) (Fig. 8). The GRADE of evidence was classified as very low quality (Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 8:

Comparison 2. Failure rate of bonded fixed retainer (liquid resin vs without liquid resin).

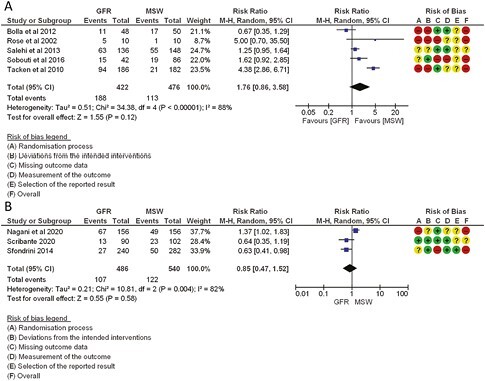

Fibre-reinforced composite versus multi-stranded wire

Eight RCTs [28, 42, 45–48, 50, 52] (five studies rated as high risk of bias and three studies rated as some concerns) compared failure rate of bonded retainers using fibre-reinforced and multi-stranded retainers. Three studies [42, 47, 48] used teeth as the unit of assessment and five studies [28, 45, 46, 50, 52] used the whole retainer as the unit of assessment. The pooled estimates of five studies (898 FOBR) which used the whole retainer as the unit of assessment indicated no statistically significant difference between MSW and fibre-reinforced composite (FRC) (RR 1.76 [95% CI 0.86–3.58; P = 0.12; I2 = 88%]) (Fig. 9). The pooled estimate of three studies (1026 teeth units involved) which used teeth as the unit of assessment indicated no difference in failure between MSW and FRC RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.47–1.52; P = 0.58; I2 = 82%) (Fig. 9). The GRADE of evidence however was classified as very low quality (Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 9:

Comparison 3. Failure rate of bonded fixed retainer FRC versus MSW (A) used the retainer as a unit of assessment and (B) used tooth as a unit of assessment.

Publication bias

Funnel plots were constructed to assess non-reporting bias for overall failure rate of FOBR, the failure rate of mandibular FOBR, and the reporting bias after excluding non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs (Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Failure rates of maxillary FOBR were not reported, as less than 10 articles were included. The asymmetrical plot suggests the potential for non-reporting bias or a discrepancy in the prevalence reported between high and low precession studies. It seems that there is a trend with the low precession studies more skewed towards overestimating the prevalence reported, while the high precision studies possibly were more towards underestimating the prevalence of FOBR failure. The reported high heterogeneity amongst the included studies might have also contributed to the asymmetric funnel plot. After the exclusion of non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs, the symmetry of the funnel plot appeared to improve. This indicates the findings of this review should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

A total of 34 studies (25 RCTs and 9 prospective clinical studies) involving 3484 participants with 4540 FOBR were included in this review. Three studies were excluded in the meta-analysis due to assessment of failure rate using the tooth as the unit of outcome assessment rather than the whole retainer. Therefore, 31 studies (22 RCTs and 9 non-RCTs) involving 3201 FOBR were included in the meta- analysis. The overall level of evidence in this review is low however with several studies rated as high risk of bias and high heterogeneity amongst studies.

Failure rate of FOBR

The overall prevalence of the failure rate of FOBR in general (both maxillary and mandibular arches combined) is 28.17% (95% CI 23.19–33.15). The prevalence of the failure rate of maxillary FOBR is 35.59% (95% CI 24.44–46.73) and that of mandibular FOBR is 27.94% (95% CI 23.03–32.85). Sensitivity analysis undertaken with exclusion of non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs, demonstrated a slight increase in the failure rate of FOBR overall (35.22% [95% CI 27.46–42.98]), a slight increase in the maxillary arch estimated as 37.53% (95% CI 27.73–47.32) and a marked increase in the mandibular arch with failure rate of 38.67% (95% CI 31–46.34).

According to the results, the failure rate of maxillary bonded retainers was noticeably higher than that of mandibular retainers. However, after exclusion of high-risk RCTs and non-RCTs, a similar failure rate was evident in both arches. Of the 31 studies included in the meta-analysis, 9 studies compared the failure rates of both maxillary and mandibular FOBR. The remaining 22 articles all reported failure rates for FOBR mandibular retainers only. All but three studies reported higher failure rates for maxillary bonded retainers [34, 35, 53]. Several studies suggested that the higher rate of maxillary FOBR failure may be due to occlusal interference [26, 38, 52, 53]. Both Forde et al. and Jowett et al. hypothesize that the difference in failure rates of maxillary and mandibular FOBR may be due to the inexperience of the operators [34, 38].

When assessing the included studies, it was noted that some studies had a short follow-up period (few months) while others had a longer follow-up period (few years). It was essential to assess if the failure rate of the FOBR increased dramatically with time. This finding could possibly influence the decision of the clinician on the length of long-term follow-up appointments. Failure rate was found to be highest in long-term follow up (5–6 years) at 41.78% which was higher than the failure rate in the short-term follow up (6 months to 1 year) and medium-term follow up (1–4 years) which was 21.70% and 29.26%, respectively. However, after exclusion of non-RCTs and high risk of bias RCTs there was a marked increase in both medium and long-term failure rates of 40.09% and 53.85%, respectively and a slight increase in the short-term failure rate (24.18%). It is interesting to note that half of the failures occurred in the first year with the majority reported in the first 6 months. Several factors may contribute to this early failure including the increased tooth mobility in the early retention phase which can increase the strain on the FOBR as well as the adequacy of moisture control during placement thus reducing the bond strength leading to an early failure. The failure rate of FOBR continues to increase with the duration of follow up doubling from 1 to 6 years. This suggests that bonded retainers require both a short and long-term maintenance plan. The first 12 months routinely require regular FOBR reviews to identify any early failure when the dentition is more prone to relapse with the periodontium remodelling. In the longer term, however, the FOBR will require review during routine dental check-up appointments where the general practitioner should have training to identify and repair retainers or have a referral pathway for timely access to orthodontic clinicians.

FOBR may fail at the wire-composite interface, composite-enamel interface or can be subject to stress fracture of the wire [58]. Failure at the enamel-composite interface was reported to be the most common of these [30, 33, 35]. Possible explanations for this could be incomplete preparation of enamel surfaces, moisture contamination, or polymerization shrinkage [29, 30, 32, 33, 36]. Debonding could also be related to the undesirable biting pattern of patients [29]. Failure between the wire and composite interface is a much less common site of failure. Some retainers have a polished surface to improve patient comfort, however, a smooth surface can be detrimental at the bonding site [38]. In addition, wear and attrition of composite can also accelerate this type of failure [26]. Failure with fracture of the FOBR has been found to be rare [26].

The most common site of failure in the mandibular arch is the central incisors most likely due to their concave morphology [13, 33, 54]. The concave lingual surface of the central incisors may lead to insufficient tooth-wire contact. Careful preparation and adaptation of the wire, along with strict moisture control and an adequate amount and distribution of adhesive, are all essential for bonded retainer success.

Factors that influence failure rate

There is low-quality evidence to suggest that there is no significant difference between failure rate of FOBR using direct versus indirect bonding procedure in the mandibular arch. The follow-up period ranges from 6 months to 5 years. In two studies Bovali et al. and Egli et al. [29, 33] chemical polymerization adhesive was used in the indirect group and photo polymerization in the direct groups. This difference in curing type could be a potential confounding factor influencing the outcome from these two studies. The results from the meta-analysis comparing direct versus indirect bonding has to be interpreted with caution due to the high clinical heterogeneity due to the variation in the wire dimension and the adhesives used.

There is low-quality evidence to suggest there is no significant difference in failure rate of FOBR using composite with or without liquid resin. In a study by Tang et al., [55] FOBRs bonded without liquid resin remained in place for a clinically acceptable time and tended to show more favourable survival rates although it was not statistically significant. On the contrary, Bazargani et al., [27] reported better retainer retention with the use of liquid resin, with a significantly lower failure incidence in the resin group. It is important to interpret these findings from the meta-analysis with caution due to clinical heterogeneity related to the difference in etching time (60 s in Tang et al. [55] and 30 s in Bazargani et al. [27]) and the use of different composite types (Reliance III which is a two paste composite and Tetric Evo flow, respectively).

There is very low-level evidence to suggest that there is no statistically significant difference between failure rate of FOBR using FRC and MSW. However, the result from this forest plot should be interpreted with caution due to the high level of heterogeneity. FRC materials and thickness used varied between studies. Generalisability of the results may be limited due to all but one of the studies being single centred. Some studies used rubber dam during bonding of FRC and this was found to be a critical factor on the long-term success rate of FRC retainers.

Operator experience is expected to influence failure rate. However, Lie Sam Foek et al. [59] reported that neither different operators nor experience played a significant role in failure. It was not possible to assess this variable in the current review as no studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria that assessed this variable. Eight studies were carried out in a primary care setting with the remaining studies conducted in a university hospital setting with orthodontists as well as postgraduate students treating participants. It is interesting to note that in the current review, the studies conducted in a university hospital setting showed a lower failure rate 24.29% (95% CI 19.55–29.04; I2 = 91%; 23 studies) compared to the reported failure rate from studies conducted in primary care practice 38.94% (95% CI 24.03–53.85; I2.= 96%; 8 studies).

Clinical implication

The outcome from this current review suggests that failure of FOBR occurred in approximately one third of participants. Although, the reported failure rate is relatively high, FOBR is recommended in cases with a high risk of relapse as it has been shown that wear compliance with removable retainers tends to reduce with time [17]. Supplementation with a removable retainer is usually considered to minimize relapse risk and unwanted tooth movement.

It is a common perception amongst clinician to expect higher failure of maxillary FOBR compared to mandibular arch. In the current systematic review, after pooling the data from all studies that met the inclusion criteria it was noted that the failure rate of maxillary FOBR was higher when compared to the mandibular arch. However, after excluding all high-risk studies it was noted that the failure rate in both arches was similar. This indicates that the failure rate of FOBR is relatively high with no high-quality evidence to suggest superiority based on jaw selection.

The findings from this current meta-analysis indicate that approximately 25% of FOBR fail during the first 12 months. It is recommended to review patients with FOBR regularly during this period to allow for prompt repair. Moreover, the risk of failure tends to still increase with time, albeit with a slower rate, indicating the need for long-term review of FOBR. This could always be part of a regular dental check-up appointment if the general dental practitioners have adequate training to manage failure or have quick access to orthodontic referral. It is important to value the benefits of FOBR in preventing relapse, however, patients should be made aware from the outset that FOBR will need long-term maintenance with a relatively high risk of failure in the long-term.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In the last decade, several systematic reviews [14, 18] published investigated the failure of FOBR with randomized CCTs, prospective clinical trials, and retrospective clinical studies included. The reported overall failure rate was 12%–50% [14] and 7.3%–50% [18]. The authors reported that there was low-quality evidence to suggest there is no difference in the failure rate between MSW and FRC. The findings of these previous reviews are in agreement with the well-conducted Cochrane systematic review [2] as well as this current review.

Limitation

The quality of evidence from this review is low. This is mainly due to the high risk of bias rated in most of the included studies. We included both RCTs and prospective non-RCTs therefore the lack of randomization and allocation concealment in the non-randomized studies could introduce selection bias. However, sensitivity analyses were carried out to assess the impact of the non-RCTs and high-risk RCTs on the outcomes.

In the majority of studies, baseline characteristics of the participants were not reported therefore comparability of participants is difficult to determine and they may have issues with confounding. Sample size calculations were not reported in the majority of the individual studies which makes power of the studies questionable. In addition, we included in this review patients who had undergone orthodontic treatment with either fixed or removable appliances. This is more reflective of orthodontic daily practice with wide generalizability; however, it could be claimed that the occlusal outcome from different orthodontic appliances may be different leading to a higher risk of bonded retainer failure rate. It is worth noting that only one study included in the current review stated clearly that some of the participants had orthodontic treatment using removable appliances [51]. The majority of studies included in this review were conducted in a hospital setting which may influence the generalisability of the review outcomes. However, subgroup analysis was conducted to demonstrate the difference in the failure rate in the hospital setting and primary care setting.

In the current review, we realize the relevance of long-term follow up for the failure of the FOBR. However, sample attrition is one of the challenges of prospective long-term studies as participants are often unwilling to attend follow-up appointments. The percentage of participants lost to follow up in the included studies ranged from 0% to 38% with most studies not applying an intention to treat analysis. This attrition bias may have influenced the reported outcomes.

In addition, a high degree of statistical heterogeneity was found in this review ranging from 60% to 98%. Clinical heterogeneity was also considered high within the included studies as patients were treated by operators with varying clinical experience, using different orthodontic appliances and treatment strategies as well as the use of a variety of FOBR designs (including the type of wire used, the number of teeth bonded, and the bonding agent, method of bonding retainers such as direct or indirect, chemical cure, or photo polymerization). The asymmetrical funnel plot suggests the potential for non-reporting bias or a discrepancy in the prevalence reported between high and low precession studies. This indicates the findings of this review should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

The failure rate of fixed bonded retainers is relatively high, 38.67% in the mandible and 37.53% in the maxilla. Almost 25% of FOBR failed in the first 12 months with the risk of failure increasing over time to almost 50% at 6 years follow up.

Indirect bonding, FRC, and the use of liquid resin with composite do not have a significant influence on the failure rate of fixed bonded retainers.

There is a need for high-quality, well-reported clinical studies to assess factors that influence the failure rate of fixed-bonded retainers.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Orthodontics online.

Supplementary Figure 1. Forest plot showing the failure rate of maxillary and mandibular bonded retainer with 95% CI reporting on hospital setting studies vs private practice setting.

Supplementary Figure 2. Funnel Plot of (A) overall bonded retainer failure, (B) mandibular bonded retainer failure rate.

Supplementary Figure 3. Funnel Plot of studies with low or some concern RoB RCTs of (A) overall bonded retainer failure, (B) mandibular bonded retainer failure rate.

Supplementary Table 1. PRISMA abstract checklist.

Supplementary Table 2. PRISMA checklist.

Supplementary Table 3. Excluded studies and Reasons for exclusion.

Supplementary Table 4. GRADE summary of findings table: what is the prevalence of fixed bonded retainer?

Supplementary Table 5. GRADE summary of findings table: direct bonding compared to indirect bonding for fixed orthodontic retainers.

Supplementary Table 6. GRADE summary of findings table: composite with liquid resin compared to without liquid resin for fixed orthodontic retainers.

Supplementary Table 7. GRADE summary of findings table: FRC compared to MSW for fixed orthodontic retainer.

Supplementary Text 1. Search strategy.

Contributor Information

Su Thae Aye, Division of Dentistry, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, UK.

Shiyao Liu, Division of Dentistry, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, UK.

Emer Byrne, University Dental Hospital of Manchester, MFT NHS Trust, UK.

Ahmed El-Angbawi, Division of Dentistry, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, UK.

Author contributions

Su Thae Aye (selection of studies, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing), Shiyao Liu (data analysis, manuscript writing), Ahmed El-Angbawi (selection of studies, data analysis, manuscript writing), and Emer Byrne (Quality assessment, manuscript writing).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by University of Manchester.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and supplementary materials are available at European Journal of Orthodontics online. I have read the journal’s requirements for reporting the data underlying my submission (data policy in EJO Author instructions) and have included a Data Availability Statement within the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sadowsky C, Sakols EI.. Long-term assessment of orthodontic relapse. Am J Orthod 1982;82:456–63. 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90312-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Littlewood SJ, Millett DT, Doubleday Bet al. Retention procedures for stabilising tooth position after treatment with orthodontic braces. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016:CD002283. 10.1002/14651858.CD002283.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katsaros C, Livas C, Renkema A-Met al. Unexpected complications of bonded mandibular lingual retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;132:838–41. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edwards JG. A long-term prospective evaluation of the circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy in alleviating orthodontic relapse. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;93:380–7. 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90096-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Surbeck BT, Årtun J, Hawkins NRet al. Associations between initial, posttreatment, and postretention alignment of maxillary anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1998;113:186–95. 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70291-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharpe W, Reed B, Subtelny JDet al. Orthodontic relapse, apical root resorption, and crestal alveolar bone levels. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1987;91:252–8. 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90455-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hösl E, Hösl E, Zachrisson BUet al. Orthodontics and Periodontics. Quintessence Publishing Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Houston, WJB, Edler, R.. Long-term stability of the lower labial segment relative to the A-Pog line. Eur J Orthod 1990;12:302–10. 10.1093/ejo/12.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadowsky C, Schneider BJ, BeGole EAet al. Long-term stability after orthodontic treatment: nonextraction with prolonged retention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1994;106:243–9. 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Contemporary Orthodontics, Vol. 226, 6th edn. Br Dent J, 2019, 828. 10.1038/s41415-019-0429-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lopez-Gavito G, Wallen TR, Little RMet al. Anterior open-bite malocclusion: a longitudinal 10-year postretention evaluation of orthodontically treated patients. Am J Orthod 1985;87:175–86. 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90038-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Artun J, Spadafora AT, Shapiro PA.. A 3-year follow-up study of various types of orthodontic canine-to-canine retainers. Eur J Orthod 1997;19:501–9. 10.1093/ejo/19.5.501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lumsden KW, Saidler G, McColl JH.. Breakage incidence with direct-bonded lingual retainers. Br J Orthod 1999;26:191–4. 10.1093/ortho/26.3.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iliadi A, Kloukos D, Gkantidis Net al. Failure of fixed orthodontic retainers: a systematic review. J Dent 2015;43:876–96. 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bellini-Pereira SA, Aliaga-Del Castillo A, dos Santos CCOet al. Treatment stability with bonded versus vacuum-formed retainers: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Eur J Orthod 2022;44:187–96. 10.1093/ejo/cjab073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmed A, Fida M, Habib Set al. Effect of direct versus indirect bonding technique on the failure rate of mandibular fixed retainer—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthod 2021;19:539–47. 10.1016/j.ortho.2021.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Moghrabi D, Pandis N, Fleming PS.. The effects of fixed and removable orthodontic retainers: a systematic review. Prog Orthod 2016;17:24. 10.1186/s40510-016-0137-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jedliński M, Grocholewicz K, Mazur Met al. What causes failure of fixed orthodontic retention?—systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Head Face Med 2021;17:32. 10.1186/s13005-021-00281-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kartal Y, Kaya B.. Fixed orthodontic retainers: a review. Turk J Orthod. 2019;32:110–4. 10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2019.18080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alraheam IA, Ngoc CN, Wiesen CAet al. Five-year success rate of resin-bonded fixed partial dentures: a systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent 2019;31:40–50. 10.1111/jerd.12431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler Jet al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2 edn: Wiley, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJet al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell Det al. (eds), The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. ScienceOpen. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan S. Meta-analysis on one proportion. In: Khan S (ed), Meta-Analysis: Methods for Health and Experimental Studies. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020, 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arash V, Teimoorian M, Farajzadeh Jalali Yet al. Clinical comparison between multi-stranded wires and single strand ribbon wires used for lingual fixed retainers. Prog Orthod 2020;21:22. 10.1186/s40510-020-00315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ardeshna AP. Clinical evaluation of fiber-reinforced-plastic bonded orthodontic retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;139:761–7. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bazargani F, Jacobson S, Lennartsson B.. A comparative evaluation of lingual retainer failure bonded with or without liquid resin. Angle Orthod 2012;82:84–7. 10.2319/032811-222.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bolla E, Cozzani M, Doldo Tet al. Failure evaluation after a 6-year retention period: a comparison between glass fiber-reinforced (GFR) and multistranded bonded retainers. Int Orthod 2012;10:16–28. 10.1016/j.ortho.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bovali E, Kiliaridis S, Cornelis MA.. Indirect vs direct bonding of mandibular fixed retainers in orthodontic patients: a single-center randomized controlled trial comparing placement time and failure over a 6-month period. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2014;146:701–8. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Çokakoğlu S, Kızıldağ A.. Comparison of periodontal status and failure rates with different retainer bonding methods and adhesives: a randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod 2023;93:57–65. 10.2319/031622-224.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cornelis MA, Egli F, Bovali Eet al. Indirect vs direct bonding of mandibular fixed retainers in orthodontic patients: comparison of retainer failures and posttreatment stability. A 5-year follow-up of a single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2022;162:152–161.e1. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Danz JC, Scherer-Zehnder I, Pandis N.. A comparative assessment of three mandibular retention protocols: a prospective cohort study. Oral Health Prev Dent 2022;20:77–84. 10.3290/j.ohpd.b2805357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egli F, Bovali E, Kiliaridis Set al. Indirect vs direct bonding of mandibular fixed retainers in orthodontic patients: comparison of retainer failures and posttreatment stability. A 2-year follow-up of a single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017;151:15–27. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Forde K, Storey M, Littlewood SJet al. Bonded versus vacuum-formed retainers: a randomized controlled trial. Part 1: stability, retainer survival, and patient satisfaction outcomes after 12 months. Eur J Orthod 2018;40:387–98. 10.1093/ejo/cjx058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gera A, Pullisaar H, Cattaneo PMet al. Stability, survival, and patient satisfaction with CAD/CAM versus conventional multistranded fixed retainers in orthodontic patients: a 6-month follow-up of a two-centre randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Orthod 2023;45:58–67. 10.1093/ejo/cjac042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gökçe B, Kaya B.. Periodontal effects and survival rates of different mandibular retainers: comparison of bonding technique and wire thickness. Eur J Orthod 2019;41:591–600. 10.1093/ejo/cjz060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gunay F, Oz AA.. Clinical effectiveness of 2 orthodontic retainer wires on mandibular arch retention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2018;153:232–8. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jowett AC, Littlewood SJ, Hodge TMet al. CAD/CAM nitinol bonded retainer versus a chairside rectangular-chain bonded retainer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. J Orthod 2022;50:55–68. 10.1177/14653125221118935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kartal Y, Kaya B, Polat-Özsoy O.. Comparative evaluation of periodontal effects and survival rates of Memotain and five-stranded bonded retainers: a prospective short-term study. J Orofacial Orthop 2021;82:32–41. 10.1007/s00056-020-00243-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krämer A, Sjöström M, Hallman Met al. Vacuum-formed retainer versus bonded retainer for dental stabilization in the mandible—a randomized controlled trial. Part I: retentive capacity 6 and 18 months after orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 2020;42:551–8. 10.1093/ejo/cjz072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee KD, Mills CM.. Bond failure rates for V-loop vs straight wire lingual retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009;135:502–6. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nagani NI, Ahmed I, Tanveer Fet al. ‘Clinical comparison of bond failure rate between two types of mandibular canine-canine bonded orthodontic retainers- a randomized clinical trial’. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:180. 10.1186/s12903-020-01167-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pandis N, Fleming PS, Kloukos Det al. Survival of bonded lingual retainers with chemical or photo polymerization over a 2-year period: a single-center, randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;144:169–75. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pop SI, Păcurar M, Gânscă O-Met al. The success rate of two types of orthodontic bonded retainers. Med Surg J 2018;122:834–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rose E, Frucht S, Jonas IE.. Clinical comparison of a multistranded wire and a direct-bonded polyethylene ribbon-reinforced resin composite used for lingual retention. Quintessence Int 2002;33:579–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salehi P, Zarif Najafi H, Roeinpeikar SM.. Comparison of survival time between two types of orthodontic fixed retainer: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Prog Orthod 2013;14:25. 10.1186/2196-1042-14-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scribante A, Sfondrini MF, Broggini S, D’Allocco M, Gandini P.. Efficacy of Esthetic Retainers: Clinical Comparison between Multistranded Wires and Direct-Bond Glass Fiber-Reinforced Composite Splints. International Journal of Dentistry 2011;2011:5, Article ID 548356. 10.1155/2011/548356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sfondrini M, Fraticelli D, Castellazzi Let al. Clinical evaluation of bond failures and survival between mandibular canine-to-canine retainers made of flexible spiral wire and fiber-reinforced composite. J Clin Exp Dent 2014;6:e145–9. 10.4317/jced.51379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shim H, Foley P, Bankhead Bet al. Comparative assessment of relapse and failure between CAD/CAM stainless steel and standard stainless steel fixed retainers in orthodontic retention patients. Angle Orthod 2022;92:87–94. 10.2319/121720-1015.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sobouti F, Rakhshan V, Saravi MGet al. Two-year survival analysis of twisted wire fixed retainer versus spiral wire and fiber-reinforced composite retainers: a preliminary explorative single-blind randomized clinical trial. Korean J Orthod 2016;46:104–10. 10.4041/kjod.2016.46.2.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Störmann I, Ehmer U.. A prospective randomized study of different retainer types. J Orofac Orthop 2002;63:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tacken MPE, Cosyn J, De Wilde Pet al. Glass fibre reinforced versus multistranded bonded orthodontic retainers: a 2 year prospective multi-centre study. Eur J Orthod 2010;32:117–23. 10.1093/ejo/cjp100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Talic NF. Failure rates of orthodontic fixed lingual retainers bonded with two flowable light-cured adhesives: a comparative prospective clinical trial. J Contemp Dent Pract 2016;17:630–4. 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taner T, Aksu M.. A prospective clinical evaluation of mandibular lingual retainer survival. Eur J Orthod 2012;34:470–4. 10.1093/ejo/cjr038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tang ATH, Forsberg C-M, Andlin-Sobocki Aet al. Lingual retainers bonded without liquid resin: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;143:101–4. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Węgrodzka E, Kornatowska K, Pandis Net al. A comparative assessment of failures and periodontal health between 2 mandibular lingual retainers in orthodontic patients. A 2-year follow-up, single practice-based randomized trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2021;160:494–502.e1. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zachrisson BU. Clinical experience with direct-bonded orthodontic retainers. Am J Orthod 1977;71:440–8. 10.1016/0002-9416(77)90247-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Renkema AM, Renkema A, Bronkhorst Eet al. Long-term effectiveness of canine-to-canine bonded flexible spiral wire lingual retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;139:614–21. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lie Sam Foek DJ, Ozcan M, Verkerke GJet al. Survival of flexible, braided, bonded stainless steel lingual retainers: a historic cohort study. Eur J Orthod 2008;30:199–204. 10.1093/ejo/cjm117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and supplementary materials are available at European Journal of Orthodontics online. I have read the journal’s requirements for reporting the data underlying my submission (data policy in EJO Author instructions) and have included a Data Availability Statement within the manuscript.