Abstract

Recombinant protein vaccines are commonly formulated with an immune-stimulatory compound, or adjuvant, to boost immune responses to a particular antigen. Recent studies have shown that, through recognition of molecular motifs, receptors of the innate immune system are involved in the functions of adjuvants to generate and direct adaptive immune responses. However, it is not clear to which degree those receptors are also important when the adjuvant is used as part of a novel heterologous prime-boost immunization process in which the priming and boosting components are not the same type of vaccines. In the current study, we compared the immune responses elicited by a pentavalent HIV-1 DNA prime–protein boost vaccine in mice deficient in either Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) or myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) to wildtype mice. HIV gp120 protein administered in the boost phase was formulated with either monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), QS-21, or Al(OH)3. Endpoint antibody titer, serum cytokine response and T-cell memory response were assessed. Neither TLR4 nor MyD88 deficiency had a significant effect on the immune response of mice given vaccine formulated with QS-21 or Al(OH)3. However, TLR4- and MyD88-deficiency decreased both the antibody and T-cell responses in mice administered HIV gp120 formulated with MPLA. These results further our understanding of the activation of TLR4 and MyD88 by MPLA in the context of a DNA prime/protein boost immunization strategy.

Keywords: TLR4, MyD88, MPLA, DNA Prime-protein boost vaccine, Antibody response

1. Introduction

Inclusion of an adjuvant in vaccine formulations serves to enhance immunogenicity by directing both innate and adaptive immune responses. Adjuvants can function by either improving antigen delivery (such as insoluble Al(OH)3 compounds,) or serving as immune-potentiators (such as, saponins, or monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) and its derivatives). However, the exact cellular mechanisms for many adjuvants have not been fully elucidated.

In recent years, it has been shown that many of the novel adjuvants currently under investigation activate innate immune signaling pathways to enhance the adaptive immune response. Interaction with different classes of innate immune sensors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), the retinoic acid–inducible gene I-like receptors (RIG-I) and DNA receptors results in activation of multiple innate functions, which can direct adaptive immune responses [1]. Early functions include secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and interferons, as well as activation of complement and the recruitment of inflammatory cells. Induction of this pro-inflammatory environment can shape the subsequent adaptive immune response.

Al(OH)3 salts are the most commonly used adjuvants in licensed vaccines, due to their tolerability and ability to induce vaccine-specific antibody responses [2,3]. In vitro evidence suggests that Al(OH)3 interacts with dendritic cells to increase the duration of antigen processing and leads to enhanced cell function [3–9]. Stimulation of macrophages or dendritic cells with alum in vitro resulted in NLRP3-dependent IL-1β release [5,10].

Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) with Al(OH)3 is currently approved for use as an adjuvant (AS04) in Ceravix™ and Fendrix™ vaccines (Glaxo-Smith Kline). MPLA is a derivative of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the main structural component of Gram-negative bacterial cell membranes and a potent activator of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). The immunomodulatory properties and the mechanism of action of LPS have long been known, however, LPS has some associated toxicity. These undesirable effects can be uncoupled from its immunomodulary properties through successive acid–base hydrolysis that results in MPLA [11–13]. Similar to LPS, MPLA stimulates TLR4 signaling, leading to a similar pattern of cytokine responses, although with reduced potency [14]. Following TLR4 engagement, two adapter proteins, MyD88 and TRIF, are recruited to the membrane and induce either early NF-κB activation or late interferon induction, respectively. However, the dependence on the activation of each of the downstream pathways following TLR4 engagement by MPLA is unclear [15,16]. The relative importance of each TLR4 adaptor molecule may be antigen specific through signaling via MyD88 or TRIF. For example, in a study comparing the innate and adaptive responses to OVA-antigen formulated with LPS or MPLA, it was suggested that TRIF-biased signaling with a concomitant reduction of activity via MyD88 adaptor and MyD88-dependent inflammatory responses was responsible for the reduced toxicity observed clinically with MPLA [17,18]. There is little information available on MPLA signaling in the context of clinically relevant antigens.

QS-21, a saponin-based adjuvant derived from Quillaja saponaria, has been shown to be highly effective and immunogenic adjuvant, particularly in the anti-cancer field [19–21]. QS-21 in combination with MPLA (AS02) was tested in clinical trials in the malaria vaccine, RTS,S/AS01 [22]. The vaccine afforded modest protection with a decreased incidence rate of 30% [22,23]. In more recent clinical trials, under low transmission groups RTS,S/AS01 afforded between 47 and 60% protection (AS02 versus AS01, respectively) depending on the specific formulation of MPL with QS-21 adjuvant system utilized [24]. In the context of a HIV-1 DNA prime–protein boost regiment, addition of QS-21 to vaccine formulations was shown to induce both potent T-cell and antibody responses, but was correlated with some adverse effects [25–29]. Like Al(OH)3, the mechanism of QS-21 activity is not clearly defined.

The DNA prime–protein boost vaccine, DP6–001, in combination with QS-21, was recently tested in Phase 1 clinical trials [27]. Significant reactogenicity in patients prompted further study of alternate adjuvants and improvement upon the vaccine formulation [30]. In our published study, we analyzed the cytokine profiles of mice immunized with DP6–001 adjuvanted with either Al(OH)3, MPLA or QS-21 in the context of the DP6–001 DNA prime–protein boost HIV vaccine formulation [30]. In the current study, we expanded upon these results to determine the relative importance of the TLR4 pathway for each of these adjuvants with DP6–001.

We observed that TLR4 and MyD88-deficient mice had normal immune responses after DP6–001 immunization containing QS-21 or Al(OH)3. However, lack of either TLR4 or MyD88 had a significant impact on immune responses in mice immunized with MPLA-formulated vaccine. Our results indicate that involvement of innate immune signaling pathways is adjuvant dependent, even in the context of a DNA prime–protein boost immunization strategy. This is one of the first studies to show the relative importance of these signaling molecules in the context of a DNA prime vaccine.

2. Results

2.1. Study design and immunization schedule

Mice were immunized with a DP6–001 DNA prime/DP6–001 protein boost formulated with adjuvant based on our previous reports on dose and schedule [30]. During the first phase, mice were immunized i.m. with either the multivalent gp120 DNA plasmids (DP6–001) or the vector DNA (pSW3891) on weeks 0, 2 and 4. DP6–001 priming was followed by two protein boosts on weeks 8 and 12 with the homologous gp120 proteins formulated with one of three adjuvants: QS-21, monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) or Al(OH)3. Animals primed with vector DNA (pSW3891) were given gp120 protein adjuvanted with MPLA. Over the course of the immunization period, serum was collected from each mouse every 2 weeks and 6 h following the final DNA prime and each protein boost. One week following the last protein boost, both antigen-specific and non-antigen specific responses were tested as described below. Experiments were performed a minimum of two times with 5 animals per group.

2.2. Antigen-specific responses involving TLR4

2.2.1. TLR4 contributes to optimal antibody responses

To determine endpoint antibody titer, serum from individual animals was assayed by ELISA. Total Env-specific IgG was quantified from mice which received either three DP6–001 DNA primes followed by two DP6–001 protein boosts formulated with one of three candidate adjuvants, or mice which received the vector control DNA followed by two DP6–001 protein boosts adjuvanted with MPLA. No detectable levels of Env-specific IgG were observed in naïve, un-immunized mice. As previously reported by our group [30], no significant differences in endpoint antibody titer were observed between wildtype mice which received DP6–001 formulated with any of the three candidate adjuvants QS-21, Al(OH)3 or MPLA (Fig. 1, black bars). When we compared antibody responses, TLR4 deficiency had no effect on Env-specific IgG levels in mice receiving the complete DP6–001 vaccine with either QS-21 or Al(OH)3. However, TLR4-deficient mice immunized with either the complete DP6–001 vaccine or vector vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA had a one-log decrease in endpoint antibody titer, indicating a significant (* p < 0.05), but not complete, reduction in antibody responses in mice deficient in TLR4. As the final antibody titers of mice immunized with DP6–001 formulated with QS-21 or Al(OH)3 were unaffected by the loss of TLR4, we focused on the effects on TLR4 deficiency on the antigen-specific and non-antigen specific responses in DNA-primed or vector primed and DP6–001protein/MPLA-immunized mice. Moreover, we were interested in the effect of DP6–001 DNA priming on these immune responses.

Fig. 1.

TLR4 contributes to optimal antibody responses in DNA primed-DP6–001/MPLA-boosted mice: gp120-specific endpoint IgG titer in wildtype (WT) and TLR4-deficient (TLR4 KO) mice immunized with DP6–001 or vector prime followed by DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with QS-21, Alum or MPLA (A); * p < 0.05. IgG isotyping of terminal sera from WT and TLR4-deficient mice; IgG1 (B), IgG2b (C), and IgG2c (D).

When we tested a small, representative panel of IgG isotypes in as an indication of a Th1- or Th2-biased immune response, significant decreases in TLR4-deficient mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine were observed in all isotypes tested (Fig. 1B–D). A one-log decrease in IgG1 was observed between WT and TLR4-deficient mice and antibody levels of both IgG2b and IgG2c in TLR4-deficient mice were two orders of magnitude lower than WT mice. Similar trends were observed in WT and TLR4-deficient animals primed with vector DNA and DP6–001 protein boosted adjuvanted with MPLA. Levels of IgG1 were reduced, whereas significant decreases were observed in levels of IgG2b and IgG2c in vector immunized TLR4-deficient mice compared to WT (Fig. 1B–D). Overall, the lack of TLR4 affected antibody levels of both Th1- and Th2-associated isotypes following DP6–001 immunization, though this difference was more pronounced in levels of IgG2b and IgG2c. Moreover, the lack of TLR4 had a significant impact upon IgG2b and IgG2c levels in mice immunized with vector vaccine.

2.2.2. TLR4 contributes to T-cell mediated IFNγ responses

One week following the final protein boost, spleens were harvested and cells were stimulated with either overlapping 15mers representing a small region from a clade B consensus sequence within gp120, phorbol myistate acetate/ionomycin (PMA/I) or mock treated. Env-specific peptide pools induced production of both Th1 (IFNγ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4 and IL-6) cytokines by vaccine-specific T-cells from WT mice as measured by ELISpot.

No differences in IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-6 were observed between WT and TLR4-deficient splenocytes from any groups in response to PMA/I (data not shown). We have previously shown that a strong IFNγ and IL-6 induction in gp120-stimulated splenocytes from mice immunized with DP6–001 adjuvanted with QS-21 [30]. When levels of IFNγ were measured, significant decreases were observed in both DNA primed and vector primed/DP6–001protein/MPLA boosted in TLR4-deficient animals (Fig. 2). Moreover, levels of IFNγ elicited from splenocytes harvested from mice immunized with the vector vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA were significantly lower compared to those harvested from mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine indicating a requirement for DNA priming for optimal T-cell responses.

Fig. 2.

TLR4 contributes to T-cell mediated IFNγ responses in DNA primed-DP6–001/MPLA-immunized mice: Single cell suspensions of splenocytes were seeded into 96-well multiscreen filter plates and stimulated for 18 h with gp120-specific peptides or media alone. IFNγ release was measured by ELISpot assay and spots quantified using CTL software; * p < 0.05.

2.3. Non-antigen specific responses involving TLR4

2.3.1. TLR4 contributes to pro-inflammatory responses

In an initial screen, pro-inflammatory cytokines in serum at each time point were tested. Results from these screens indicated no significant increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines one week following DNA priming alone [30]. DNA priming followed by adjuvanted protein induced inflammatory responses. Based on this screen, a smaller panel was designed to test target analytes observed to be significant 6 h following each protein boost (Fig. 3A–C). We found that DNA priming followed by DP6–001 protein with adjuvant induced some inflammatory response. Overall, no differences in the pro-inflammatory panel were observed between WT and TLR4-deficient mice immunized with DNA followed by DP6–001 adjuvanted with either QS-21 or Al(OH)3 (data not shown). However, significant decreases in RANTES, IL-6 and G-CSF were observed between WT and TLR4-deficient mice immunized with either DP6–001 DNA or vector DNA followed by DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with MPLA (Fig. 3A–C). This was especially true for G-CSF and IL-6, where levels in TLR4-deficient mice were near pre-immune levels (Fig. 3, #). These results suggest that the pro-inflammatory environment induced by DP6/001/MPLA in the context of the DP6–001 DNA prime/protein boost is dependent upon TLR4.

Fig. 3.

TLR4 contributes to pro-inflammatory responses in DNA primed-DP6–001/MPLA immunized mice: Sera samples were harvested 6 h following each protein boost and were assayed by Luminex multiplex array; * p < 0.05.

2.4. Antigen-specific responses involving MyD88

2.4.1. MyD88 contributes to antibody responses

We also tested the role of MyD88 in eliciting an immune response in DP6–001 immunized mice. Endpoint antibody titer from individual animals was assayed by ELISA. Total Env-specific IgG was quantified in mice immunized with either three DP6–001 DNA primes followed by two DP6–001 protein boosts formulated with one of three candidate adjuvants (full DP6–001 vaccine), or in mice immunized with vector DNA followed by two protein boosts adjuvanted with MPLA (vector vaccine).

Similar to the results observed in TLR4-deficient mice, when we compared antibody responses between wildtype (WT) and MyD88-deficient mice (MyD88 KO), MyD88 deficiency had no effect on Env-specific IgG levels in DNA primed mice receiving DP6–001 protein adjuvanted by either QS-21 or Al(OH)3 (Fig. 4A). MyD88-deficient mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA had approximately a one-log decrease in endpoint antibody titer (* p <0.05). Similar to results in our studies in TLR4-deficient mice, no significant differences were observed between WT and MyD88-deficient mice that were immunized with the vector vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA. This result suggests that the presence of gp120 in the DNA component of the vaccine could influence signaling pathways induced by the subsequent gp120 protein with MPLA adjuvant immunization. We observed that TLR4 deficiency resulted in a significant reduction in both primed and unprimed animals whereas MyD88 deficiency resulted in a significant reduction in only DNA primed animals (Fig. 4B). Moreover, we observed significant differences between TLR4-and MyD88-deficient mice in the context of DNA primed, but not unprimed, animals. The difference we see between TLR4 and MyD88 deficient animals suggests that TRIF may be also be contributing to the optimal antibody generation following vaccination.

Fig. 4.

MyD88 contributes to antibody responses in DNA primed-DP6–001/MPLA immunized mice: gp120-specific endpoint IgG titer in wildtype (WT) and MyD88-deficient mice immunized with DP6–001 or vector DNA prime followed by DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with QS-21, Al(OH)3 or MPLA (A). gp120-specific endpoint titer in WT, TLR4-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice (cumulative data from two experiments) (B) * p <0.05 IgG isotyping of terminal sera from WT and MyD88-deficient mice. IgG1 (C), IgG2b (D), and IgG2c (E).

Since the final antibody titers of mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with either QS-21 or Al(OH)3 were unaffected by the absence of MyD88, we focused on the impact of MyD88 deficiency on the antigen-specific and non-antigen specific responses in mice immunized with either the full DP6–001 vaccine or the vector vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA. Moreover, we were interested in the effect of DNA priming on these responses.

To determine Th1- or Th2-biased antibody responses in immunized mice, IgG isotyping was conducted from sera samples from WT and MyD88-deficient mice. Similar to TLR4-deficient mice, we observed significant differences in total IgG1, IgG2b and Ig2c in MyD88-deficient mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA compared to WT (Fig. 4A–E). Differences were also observed in levels of IgG2c between WT and MyD88-deficient mice that received vector vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA (Fig. 4E). Clearly, MyD88 deficiency has less of an impact on IgG levels in vector-primed animals compared to those that received the DP6–001 DNA priming.

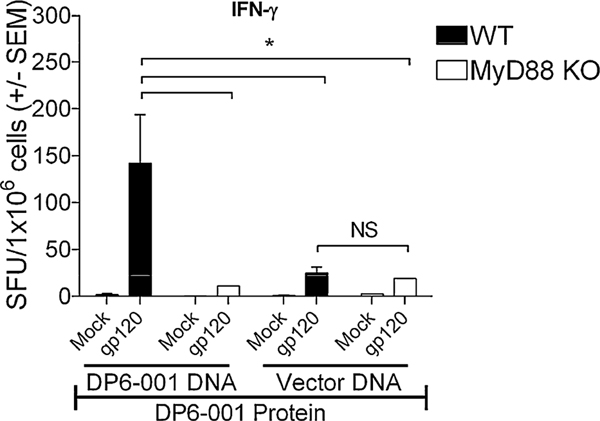

2.4.2. MyD88 is required for T-cell mediated IFNγ responses

One week following the last protein boost, spleens were harvested and cells were stimulated with either overlapping 15mers representing a small region from a clade B consensus sequence within gp120, phorbol myistate acetate/ionomycin (PMA/I) or mock treated. Env-specific peptide pools induced production of both Th1 (IFNγ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4 and IL-6) cytokines by vaccine-specific T-cells as measured by ELISpot. No differences between WT and MyD88-deficient splenocytes were observed in levels of IFNγ, IL-2 and IL-6 in response to PMA/I. Strong IFNγ and IL-6 induction was observed in Env-stimulated splenocytes from mice immunized with DP6–001 DNA primed/DP6–001 adjuvanted with QS-21 [30]. No significant differences in levels of IL-2 or IL-6 were observed from WT and MyD88-deficient splenocytes immunized with DP6–001 DNA primed followed by DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with MPLA. However, when we compared levels of IFNγ induced from splenocytes between WT and MyD88-deficient mice, significant decreases were observed in DP6–001 DNA primed-DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with MPLA, but not the vector DNA primed-DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with MPLA group (Fig. 5). Moreover, levels of IFNγ elicited from WT splenocytes were significantly lower when we compared full DP6–001 vaccine with MPLA and vector vaccine with MPLA, indicating a requirement for DNA priming for optimal T-cell responses.

Fig. 5.

MyD88 is required for T-cell mediated IFNγ responses in DP6–001/MPLA immunized mice: Single cell suspensions of splenocytes were seeded into 96-well multiscreen filter plates and stimulated for 18 h with Env-specific peptides or media alone. IFNγ release was measured by ELISpot assay and spots quantified using CTL software; * p < 0.05.

Overall, T-cell mediated IFNγ responses in DP6–001 DNA primed-DP6–001 protein with MPLA-immunized animals were dependent upon both the presence of TLR4 and MyD88protein with MPLA-immunized animals, TLR4, but not MyD88, was required for full vaccine efficacy in the context of vector immunization.

2.5. Non-antigen specific responses involving MyD88

2.5.1. MyD88 is necessary for pro-inflammatory responses

Utilizing the smaller cytokine/chemokine panel described above, we next assayed pro-inflammatory cytokines responses. Serum samples harvested 6 h after the first and second protein boosts yielded significant increases in pro-inflammatory analytes. Overall, no differences in the pro-inflammatory panel were observed between WT and MyD88-deficient mice immunized with the full DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with either QS-21 or Al(OH)3 (data not shown). However, decreases in our cytokine panel were observed between WT and MyD88-deficient mice immunized with DP6–001 DNA and protein adjuvanted with MPLA, where levels in MyD88-deficient mice were almost undetectable (Fig. 6A–C, #). In particular, high expression of G-CSF was dependent upon DNA priming, as vector primed animals had significantly lower levels of circulating G-CSF when compared to WT.

Fig. 6.

MyD88 is necessary for pro-inflammatory responses in MPLA-immunized mice following protein boosting: Sera samples harvested 6 h following each protein boost were assayed by Luminex multiplex array; * p < 0.05.

3. Discussion and conclusion

Overall, we observed that both TLR4 and MyD88 were necessary for a strong humoral and cell-mediated immune response as well as induction of acute pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice immunized with DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with MPLA, but not in mice immunized with DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with QS-21 or Al(OH)3. Differences in T-cell memory responses, specifically in IFNγ levels, were observed between WT and TLR4-deficient mice as well as between WT and MyD88-deficient mice immunized with DP6–001 vaccine with MPLA, but not in mice immunized with the same full DP6–001 vaccine adjuvanted with QS-21 or Al(OH)3. Moreover, gp120 DNA priming had a significant role in the immune response observed, as shown by differences between DP6–001 DNA primed and vector primed groups. We observed that gp120 DNA priming had a significant effect on the downstream immune response and that this might reflect antigen-specific effects. In the context of the DP6–001 DNA primed-DP6–001 protein adjuvanted with MPLA immunization strategy, the presence of both TLR4 and MyD88 played a significant role in the downstream adaptive immune response.

Earlier work has demonstrated that the species of TLR4/MD-2 may determine activation of certain lipid A structures with structural information and activity studies [31–33]. This previous work has however mostly focused on the responses to hypo-acylated lipid A compounds and less on lipids with differences in phosphorylation status. There are some indications that de-phosphorylated lipid A may have a somewhat lower response toward certain human cells in vitro than those observed with mouse cells but this is incompletely understood [16]. However, MPLA as an adjuvant appears to be well suited for both mouse and human vaccines. MPLA is now extensively used as an adjuvant in an array of both licensed vaccines (Ceravix™ and Fendrix™) and those undergoing clinical evaluation (Engerix™, LEISH-111f+MPL-SE and the norovirus bivalent VLP).

It has been proposed that MPLA induces a suboptimal TLR4-MD-2 hetero-complex formation, resulting in its decreased activation of TLR4-dependent inflammation [34]. CD14 is a GPI-anchored molecule expressed on myeloid cells that is known for binding LPS and enhancing TLR4-mediated effects. Recently it has been suggested that MPLA induces reduced CD14-dependent tight dimerization of the TLR4/MD-2 complex [35]. These findings hint at possible explanations for reduced MPLA-induced inflammatory reactions compared to those induced by LPS, as the absence of a phosphate group will inevitably lead to differences in electrostatic interactions between ligand and key residues of TLR4/MD-2 [31,32,36]. The availability of X-ray structural data on how MPLA interacts with the TLR4/MD-2 receptor complex would greatly aid in the understanding of the molecular mechanism behind MPLA-induced cellular responses. It has been proposed that the use of MPLA in vaccination induces a TRIF bias in terms of TLR4 signaling adapter utilization [17]. It is possible that MPLA has a reduced activation of the TLR4 complex at the cell surface, as discussed above, disproportionally affecting MyD88 signaling. One hypothesis could be that initiation of intracellular TLR4-TRIF signaling in the endosome is better preserved [37], although little data supporting this is available. An alternative explanation could be that differences in thresholds for some MPLA-induced responses via MyD88 and TRIF could exist, with both TLR4 adaptors participating in optimal adjuvant effects for MPLA.

It is possible that autophagy contributes to the TLR4-mediated vaccine responses we see, as TLR4 ligands have been shown to promote autophagy, and that increased autophagy is associated with increased adaptive immune responses to vaccine [38,39]. Both TRIF and MyD88 have been proposed to participate in this process, but little information is available on how MPLA would impact autophagy and downstream antigen presentation.

Our study shows that MyD88 may have a significant effect on the adaptive immune responses in MPLA-adjuvanted vaccine in the context of a novel and clinically relevant DNA prime–protein boost strategy. Several studies have shown that TRIF contributes to the MPLA adjuvant effects [17], specifically the involvement of TRIF in upregulating co-stimulatory molecules by LPS and MPLA [40,41]. Hoebe et al. also suggested the need for TRIF to optimally induce co-stimulatory molecules downstream of LPS/TLR4, however, it is important to note that actual co-stimulation was impacted by both MyD88 and TRIF [41]. Recent work has shown that, compared to wild type mice, T-cell expansion [40] is poorly supported in TRIF deficient mice following MPLA adjuvanted vaccination. This study was conducted by administration of a single peptide antigen (OVA) with MPLA, indicating a role for TRIF in this context. Adenoviral delivery of HIV-1 Gag in mice, with MPLA or LPS as adjuvants, also observed impact of both MyD88 and TRIF on antigen-specific CD8+ lymphocytes [42]. Although we have not directly tested the effect of TRIF in our immunization scheme, it must be noted that the effect of MyD88 is significant, leading us to speculate that the role of TRIF in adaptive immune responses following MPLA containing vaccines may be partial. Our data indicate that antibody end point titers in TLR4 KO mice were significantly lower than in DNA primed MyD88 KO mice, consistent with a role for both MyD88 and TRIF. Thus, TRIF and MyD88 may both impact MPLA-adjuvanted DNA prime–protein boost vaccine responses. Our findings provide a basis for understanding innate immune signaling in a DNA-vaccine prime adjuvanted protein-boost scheme, and these findings may contribute to the development of improved vaccines.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Mice and reagents

C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). TLR4−/− and MyD88−/− were generated as previously described [43,44]. All mice were housed in a pathogen-free rodent barrier facility and fed a standard diet of rodent chow and water ad libitum. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA). Purified monosphosphoryl lipid-A (MPLA, derived from Salmonella minnesota, R595) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). QS-21 was purchased from Antigenics Inc. (Woburn, MA) and Aluminum hydroxide gel (Al(OH)3) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). ELISA antibodies were from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). ELISpot assay kits for the detection of IFNγ, IL-2, and IL-4 were purchased from Mabtech (Mariemont, OH). ELISPot kits for detection of IL-6 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). ELISpot plates were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Phorbol 12-myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

4.2. DP6–001 vaccine formulation

The gp-120-expressing DNA vaccine component was composed of equal amounts of five plasmids encoding codon-optimized gp120 from primary HIV-1 isolates: A (92UG037.8), B (92US715.6), Ba-L, Czm (96ZM651) and E (93TH976.17) in the common vector (pSW3891) as previously described [30]. Plasmids were grown in Escherichia coli, strain HB101, and purified using the Giga Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Plasmid expression was confirmed by transient expression in 293T cells and Western blot. The protein component of DP6–001 was comprised of equal amounts of the five cognate HIV-1 gp120 proteins as above. These gp120 proteins were produced in CHO cell lines by Advanced Bioscience Laboratories (Kensington, MD) as previously described [30].

4.3. Immunizations

DNA vaccines (120 μg/dose) were administered intramuscularly. Vector control plasmid, pSW3891, has been described previously [30]. Protein vaccine (35 μg total/dose) was administered either with QS-21 (5 μg/dose), Al(OH)3 (175 μg/dose) or MPLA (25 μg/dose). Mice were immunized with DNA on weeks 0, 2 and 4 followed by protein boosting on weeks 8 and 12. Serum samples were taken every 2 weeks and 6 h following each protein boost. One week following the last protein boost, mice were euthanized and assays conducted as described. Immunization groups consisted of five animals per group and each experiment was repeated at least twice.

4.4. Serum antibody responses

For endpoint titers, serum gp120-specific antibody responses were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay (ELISA) as described previously [45] Briefly, EIA/RIA microtiter plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were pre-coated with 5 μg/well ConA for 1 h. After washing (AquaMax2000, Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, CA), plates were coated with 1 μg/ml gp120 protein mix. After blocking overnight (4% whey and 5% powdered milk), plates were incubated with mouse sera for 1 h. For detection of IgG, biotinylated anti-mouse IgG was added followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Serum titers were determined as the highest dilution of immune serum producing ELISA values (A450 nm) greater than or equal to two times the binding detected with a corresponding dilution of pre-immune serum. Plates were coated with 0.5 μg/ml gp120 (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Kensington, MD). Dilution series of sera was performed. The end titration was determined as the highest dilution at which the absorbance at OD450 equaled twice the absorbance of negative control wells. For isotyping of serum, standard curves for each isotype were performed. The end titration was determined as the highest dilution at which the absorbance at OD450 equaled twice the absorbance of negative control wells.

4.5. T-cell stimulation assay

Spleens were harvested 7 days following the final protein boost. Organs were homogenized manually in RPMI 1640 (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with 10% heat inactivated FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 1% Ciprofloxacin. Cell suspensions were filtered through 40 μm mesh and red blood cells lysed with RBC Lysis Buffer (Sigma). Splenocytes were seeded in triplicate into pre-coated ELISpot plates at 2.5×105/well in RPMI with 10% FBS (HyClone) and ciprofloxacin. Antigen-specific stimulation was performed with truncated peptide pools derived from clade B consensus Env peptide pool at 2 μg/ml. Cells were stimulated with Env-specific peptides [G pool (peptides 8840–8853) or V3 pool (8836–8844), NIH] as previously described [46]. Control wells contained either media alone (mock) or with 20 ng/ml PMA and 500 ng/ml ionomycin. Cells were stimulated for 18–20 h at 37 C in 5% CO2. Assays were conducted per the manufacturer’s directions. Spots were visualized using a CTL Imager and counted with Immunospot™ software (Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights OH).

4.6. Cytokine and chemokine analyses

Serum levels of target analytes and were measured by multiplex suspension array purchased from Biorad, and read on a Bio-Plex 200 analyzer using Bio-Plex Manager Software using the manufacturer’s directions (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Individual serum samples were diluted 1:4 in sample diluent. A ten-point standard curve was used for each analyte and any high-end saturation points were removed from the standard curves for determining sample concentrations.

4.7. Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All experiments were repeated at least two times. Statistical evaluations were performed using either a Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney rank-sum analysis where indicated.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by NIH grants 5 U19 AI082676 and 5 P01 AI082274. We thank Anna Cerny, Gail Germain and Kelly Army for animal husbandry.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Tritto E, Mosca F, De Gregorio E. Mechanism of action of licensed vaccine adjuvants. Vaccine 2009;27(25–26):3331–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Guy B. The perfect mix: recent progress in adjuvant research. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007;5(7):505–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marrack P, McKee AS, Munks MW. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9(4):287–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Flach TL, et al. Alum interaction with dendritic cell membrane lipids is essential for its adjuvanticity. Nat Med 2011; 17(4):479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kool M, et al. Cutting edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 2008;181(6):3755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McKee AS, et al. Alum induces innate immune responses through macrophage and mast cell sensors: but these sensors are not required for alum to act as an adjuvant for specific immunity. J Immunol 2009;183(7):4403–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sharp FA, et al. Uptake of particulate vaccine adjuvants by dendritic cells activates the NALP3 inflammasome. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2009;106(3):870–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ghimire TR, et al. Alum increases antigen uptake, reduces antigen degradation and sustains antigen presentation by DCs in vitro. Immunol Lett 2012; 147(1–2):55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mori A, et al. The vaccine adjuvant alum inhibits IL-12 by promoting PI3 kinase signaling while chitosan does not inhibit IL-12 and enhances Th1 and Th17 responses. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42(10):2709–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eisenbarth SC, et al. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 2008;453(7198):1122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ribi E. Beneficial modification of the endotoxin molecule. J Biol Response Mod 1984;3(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ribi E, et al. Lipid A and immunotherapy. Rev Infect Dis 1984;6(4):567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thompson BS, et al. The low-toxicity versions of LPS: MPL adjuvant and RC529, are efficient adjuvants for CD4+ T cells. J Leukocyte Biol 2005;78(6):1273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Alving CR, Rao M. Lipid A and liposomes containing lipid A as antigens and adjuvants. Vaccine 2008;26(24):3036–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kolanowski ST, et al. TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory dendritic cell differentiation in humans requires the combined action of MyD88 and TRIF. Innate Immun. 2014; 20(4): 423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chilton PM, et al. Adjuvant activity of naturally occurring monophosphoryl lipopolysaccharide preparations from mucosa-associated bacteria. Infect Immun 2013; 81(9):3317–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mata-Haro V, et al. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science 2007;316(5831):1628–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cekic C, et al. Selective activation of the p38 MAPK pathway by synthetic monophosphoryl lipid A. J Biol Chem 2009;284(46):31982–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Behboudi S, Morein B, Villacres-Eriksson M. In vivo and in vitro induction of IL-6 by Quillaja saponaria molina triterpenoid formulations. Cytokine 1997;9(9):682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].den Brok MH, et al. Saponin-based adjuvants create a highly effective antitumor vaccine when combined with in situ tumor destruction. Vaccine 2012; 30(4):737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cristillo AD, et al. Preclinical evaluation of cellular immune responses elicited by a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost HIV-1 vaccine. Virology 2006;346(1):151–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Agnandji ST, et al. A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(24):2284–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Agnandji ST, et al. First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African children. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(20):1863–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bejon P, et al. Efficacy of RTS,S malaria vaccines: individual-participant pooled analysis of phase 2 data. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13(4):319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pal R, et al. Immunization of rhesus macaques with a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine elicits protective antibody response against simian human immunodeficiency virus of R5 phenotype. Virology 2006;348(2):341–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pal R, et al. Polyvalent DNA prime and envelope protein boost HIV-1 vaccine elicits humoral and cellular responses and controls plasma viremia in rhesus macaques following rectal challenge with an R5 SHIV isolate. J Med Primatol 2005;34(5–6):226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang S, et al. Cross-subtype antibody and cellular immune responses induced by a polyvalent DNA prime–protein boost HIV-1 vaccine in healthy human volunteers. Vaccine 2008;26(31):3947–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bansal A, et al. Multifunctional T-cell characteristics induced by a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine regimen given to healthy adults are dependent on the route and dose of administration. J Virol 2008;82(13):6458–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kennedy JS, et al. The safety and tolerability of an HIV-1 DNA prime–protein boost vaccine (DP6–001) in healthy adult volunteers. Vaccine 2008;26(35):4420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Buglione-Corbett R, et al. Serum cytokine profiles associated with specific adjuvants used in a DNA prime–protein boost vaccination strategy. PLoS One 2013; 8(9):e74820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Meng J, Lien E, Golenbock DT. MD-2-mediated ionic interactions between lipid A and TLR4 are essential for receptor activation. J Biol Chem 2010;285(12):8695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ohto U, et al. Structural basis of species-specific endotoxin sensing by innate immune receptor TLR4/MD-2. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2012;109(19): 7421–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hajjar AM, et al. Humanized TLR4/MD-2 mice reveal LPS recognition differentially impacts susceptibility to Yersinia pestis and Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog 2012;8(10):e1002963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Inefficient TLR4/MD-2 heterotetramerization by monophosphoryl lipid A. PLoS One 2013;8(4):e62622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tanimura N, et al. The attenuated inflammation of MPL is due to the lack of CD14-dependent tight dimerization of the TLR4/MD2 complex at the plasma membrane. Int Immunol 2014; 26(6):307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Park BS, et al. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4–MD-2 complex. Nature 2009;458(7242):1191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kagan JC, et al. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-beta. Nat Immunol 2008;9(4):361–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu Y, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity 2007;27(1):135–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schmid D, Munz C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity 2007;27(1):11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gandhapudi SK, Chilton PM, Mitchell TC, TRIF is required for TLR4 mediated adjuvant effects on T cell clonal expansion. PLoS One 2013; 8(2):e56855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hoebe K, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol 2003;4(12):1223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Meerak J, Wanichwecharungruang SP, Palaga T. Enhancement of immune response to a DNA vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85B by incorporation of an autophagy inducing system. Vaccine 2013;31(5): 784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Adachi O, et al. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1-and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity 1998;9(1):143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hoshino K, et al. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol 1999;162(7):3749–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vaine M, et al. Antibody responses elicited through homologous or heterologous prime-boost DNA and protein vaccinations differ in functional activity and avidity. Vaccine 2010;28(17):2999–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Brown LE, et al. Synthetic peptides representing sequences within gp41 of HIV as immunogens for murine T- and B-cell responses. Arch Virol 1995;140(4):635–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]