Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system that affects mainly young adults (two to three times more frequently in women than in men) and causes significant disability after onset. Although it is accepted that immunotherapies for people with MS decrease disease activity, uncertainty regarding their relative safety remains.

Objectives

To compare adverse effects of immunotherapies for people with MS or clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), and to rank these treatments according to their relative risks of adverse effects through network meta‐analyses (NMAs).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, PubMed, Embase, two other databases and trials registers up to March 2022, together with reference checking and citation searching to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included participants 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of MS or CIS, according to any accepted diagnostic criteria, who were included in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined one or more of the agents used in MS or CIS, and compared them versus placebo or another active agent. We excluded RCTs in which a drug regimen was compared with a different regimen of the same drug without another active agent or placebo as a control arm.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods for data extraction and pairwise meta‐analyses. For NMAs, we used the netmeta suite of commands in R to fit random‐effects NMAs assuming a common between‐study variance. We used the CINeMA platform to GRADE the certainty of the body of evidence in NMAs. We considered a relative risk (RR) of 1.5 as a non‐inferiority safety threshold compared to placebo. We assessed the certainty of evidence for primary outcomes within the NMA according to GRADE, as very low, low, moderate or high.

Main results

This NMA included 123 trials with 57,682 participants.

Serious adverse events (SAEs)

Reporting of SAEs was available from 84 studies including 5696 (11%) events in 51,833 (89.9%) participants out of 57,682 participants in all studies. Based on the absolute frequency of SAEs, our non‐inferiority threshold (up to a 50% increased risk) meant that no more than 1 in 18 additional people would have a SAE compared to placebo.

Low‐certainty evidence suggested that three drugs may decrease SAEs compared to placebo (relative risk [RR], 95% confidence interval [CI]): interferon beta‐1a (Avonex) (0.78, 0.66 to 0.94); dimethyl fumarate (0.79, 0.67 to 0.93), and glatiramer acetate (0.84, 0.72 to 0.98).

Several drugs met our non‐inferiority criterion versus placebo: moderate‐certainty evidence for teriflunomide (1.08, 0.88 to 1.31); low‐certainty evidence for ocrelizumab (0.85, 0.67 to 1.07), ozanimod (0.88, 0.59 to 1.33), interferon beta‐1b (0.94, 0.78 to 1.12), interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) (0.96, 0.80 to 1.15), natalizumab (0.97, 0.79 to 1.19), fingolimod (1.05, 0.92 to 1.20) and laquinimod (1.06, 0.83 to 1.34); very low‐certainty evidence for daclizumab (0.83, 0.68 to 1.02).

Non‐inferiority with placebo was not met due to imprecision for the other drugs: low‐certainty evidence for cladribine (1.10, 0.79 to 1.52), siponimod (1.20, 0.95 to 1.51), ofatumumab (1.26, 0.88 to 1.79) and rituximab (1.01, 0.67 to 1.52); very low‐certainty evidence for immunoglobulins (1.05, 0.33 to 3.32), diroximel fumarate (1.05, 0.23 to 4.69), peg‐interferon beta‐1a (1.07, 0.66 to 1.74), alemtuzumab (1.16, 0.85 to 1.60), interferons (1.62, 0.21 to 12.72) and azathioprine (3.62, 0.76 to 17.19).

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Reporting of withdrawals due to AEs was available from 105 studies (85.4%) including 3537 (6.39%) events in 55,320 (95.9%) patients out of 57,682 patients in all studies. Based on the absolute frequency of withdrawals, our non‐inferiority threshold (up to a 50% increased risk) meant that no more than 1 in 31 additional people would withdraw compared to placebo.

No drug reduced withdrawals due to adverse events when compared with placebo.

There was very low‐certainty evidence (meaning that estimates are not reliable) that two drugs met our non‐inferiority criterion versus placebo, assuming an upper 95% CI RR limit of 1.5: diroximel fumarate (0.38, 0.11 to 1.27) and alemtuzumab (0.63, 0.33 to 1.19).

Non‐inferiority with placebo was not met due to imprecision for the following drugs: low‐certainty evidence for ofatumumab (1.50, 0.87 to 2.59); very low‐certainty evidence for methotrexate (0.94, 0.02 to 46.70), corticosteroids (1.05, 0.16 to 7.14), ozanimod (1.06, 0.58 to 1.93), natalizumab (1.20, 0.77 to 1.85), ocrelizumab (1.32, 0.81 to 2.14), dimethyl fumarate (1.34, 0.96 to 1.86), siponimod (1.63, 0.96 to 2.79), rituximab (1.63, 0.53 to 5.00), cladribine (1.80, 0.89 to 3.62), mitoxantrone (2.11, 0.50 to 8.87), interferons (3.47, 0.95 to 12.72), and cyclophosphamide (3.86, 0.45 to 33.50).

Eleven drugs may have increased withdrawals due to adverse events compared with placebo: low‐certainty evidence for teriflunomide (1.37, 1.01 to 1.85), glatiramer acetate (1.76, 1.36 to 2.26), fingolimod (1.79, 1.40 to 2.28), interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) (2.15, 1.58 to 2.93), daclizumab (2.19, 1.31 to 3.65) and interferon beta‐1b (2.59, 1.87 to 3.77); very low‐certainty evidence for laquinimod (1.42, 1.01 to 2.00), interferon beta‐1a (Avonex) (1.54, 1.13 to 2.10), immunoglobulins (1.87, 1.01 to 3.45), peg‐interferon beta‐1a (3.46, 1.44 to 8.33) and azathioprine (6.95, 2.57 to 18.78); however, very low‐certainty evidence is unreliable.

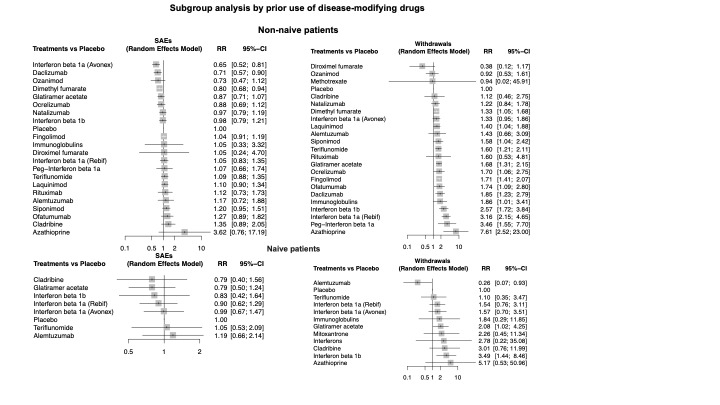

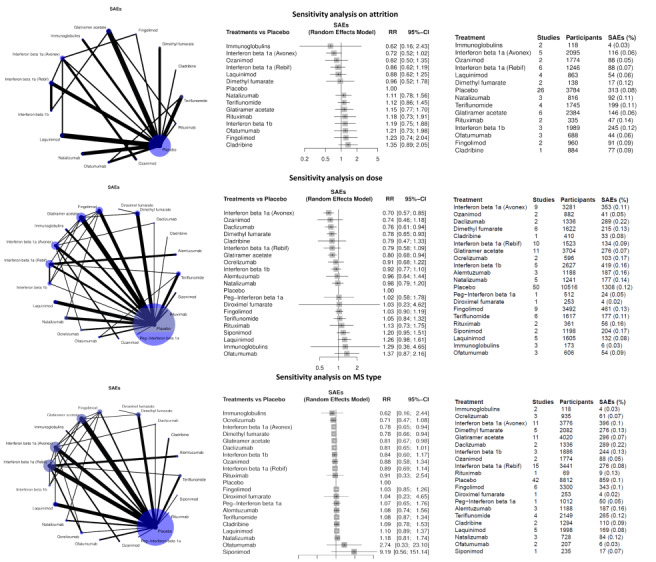

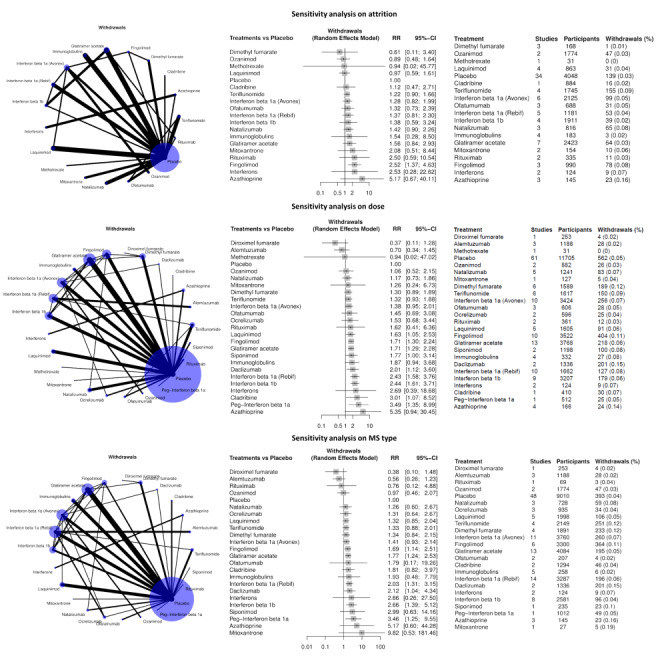

Sensitivity analyses including only studies with low attrition bias, drug dose above the group median, or only patients with relapsing remitting MS or CIS, and subgroup analyses by prior disease‐modifying treatments did not change these figures.

Rankings

No drug yielded consistent P scores in the upper quartile of the probability of being better than others for primary and secondary outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

We found mostly low and very low‐certainty evidence that drugs used to treat MS may not increase SAEs, but may increase withdrawals compared with placebo. The results suggest that there is no important difference in the occurrence of SAEs between first‐ and second‐line drugs and between oral, injectable, or infused drugs, compared with placebo.

Our review, along with other work in the literature, confirms poor‐quality reporting of adverse events from RCTs of interventions. At the least, future studies should follow the CONSORT recommendations about reporting harm‐related issues. To address adverse effects, future systematic reviews should also include non‐randomized studies.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Young Adult, Alemtuzumab, Azathioprine, Cladribine, Daclizumab, Dimethyl Fumarate, Fingolimod Hydrochloride, Glatiramer Acetate, Immunosuppressive Agents, Immunosuppressive Agents/adverse effects, Immunotherapy, Interferon beta-1a, Interferon beta-1a/adverse effects, Interferon beta-1b, Multiple Sclerosis, Multiple Sclerosis/drug therapy, Natalizumab, Network Meta-Analysis, Rituximab

Plain language summary

What are the risks of therapies for treating multiple sclerosis?

Key messages

‐ Immunotherapies used to treat multiple sclerosis appear not to increase serious health events, compared to sham drugs (placebo).

‐ Many of these drugs have unwanted effects and, for some of them, more people included in studies dropped out because of side effects compared to sham drugs.

‐ These results are only partly, or are not, reliable since serious health events are relatively rare in people with multiple sclerosis, meaning that the issue is difficult to study, and serious health events were also not well reported in the studies.

What is the condition?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects the brain and the spinal cord. MS affects more women than men. In MS, the immune system attacks the sheath that covers our body's nerves and weakens their function. Some people with severe MS may even not be able to use their arms or legs well for some time, but they usually recover. Disability, for example in walking, can arise in some people who have many attacks over the years.

How is the condition treated?

Several treatments that modulate the immune system are available that can help speed recovery from attacks and improve the course of the disease.

What did we want to find out?

We aimed to investigate the risks of the drugs used to treat MS. We wanted to assess all types of health events that are serious, for example, admissions to hospital, or events that made people stop taking the medication. We also wanted to investigate health events in specific body organs.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated drugs aiming to improve the course of MS, compared with other drugs or sham drugs, in people with recurrent episodes of the disease.

What did we find?

Serious health events were found in about one in nine people receiving a sham drug during one or two years. The following drugs were found not to increase these events: interferon beta‐1a (Avonex), dimethyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, ocrelizumab, ozanimod, interferon beta‐1b, interferon beta‐1a (Rebif), natalizumab, fingolimod, and laquinimod. We cannot tell whether the following drugs cause more serious health events than sham because the studies were small or there were few events (for cladribine, siponimod, ofatumumab, and rituximab). We were very unsure about daclizumab, immunoglobulins, diroximel fumarate, peg‐interferon beta‐1a, alemtuzumab, interferons and azathioprine because the evidence regarding serious health events was of very poor quality.

Unwanted effects causing people to stop taking the medication were found in one in 16 people receiving a sham drug for one or two years. The following drugs may have increased these dropouts: teriflunomide, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, interferon beta‐1a (Rebif), daclizumab and interferon beta‐1b. We cannot tell whether ofatumumab causes more dropouts than sham because the studies were small or there were few events. We are very unsure about diroximel fumarate, alemtuzumab, methotrexate, corticosteroids, ozanimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, dimethyl fumarate, siponimod, rituximab, cladribine, mitoxantrone, interferons, cyclophosphamide, laquinimod, interferon beta‐1a (Avonex), immunoglobulins, peg‐interferon beta‐1a and azathioprine because the evidence regarding dropouts was of very poor quality.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Most of the evidence came from studies conducted in ways that may have introduced errors into their results, including the fact that harms were not well reported. Moreover, serious health events and unwanted effects are rare in people with MS and, thus, difficult to study.

How up‐to‐date is the evidence?

This review is up‐to‐date until March 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings 1. Immunotherapies compared to placebo for adults with multiple sclerosis.

| Immunotherapies compared to placebo for adults with multiple sclerosis | |||||||

|

Population: adults with multiple sclerosis Interventions: immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory drugs Comparator: placebo Outcome: serious adverse events (SAEs), mostly at 1 or 2 years Setting: specialist setting Equivalence criterion: RR between 0.67 and 1.50, also meaning that non‐inferiority with placebo was achieved if RR ≤ 1.50, with no more than 1 in 18 additional people having a SAE compared to placebo, at a baseline SAE occurrence of 1 in 9 patients (11.3%) | |||||||

| Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | |||||||

| Drug (vs. placebo) | No. of studies for network meta‐analysis (no. of participants in the drug‐specific arm) | No. of studies with direct comparison to placebo (total no. of participants in the drug‐specific arm and in the placebo arm) | Assumed placebo risk (per 1000) | Corresponding intervention risk (95% CI) | Mixed RR (95% CI) | Certainty of evidence | P score |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Avonex) | 11 (3776) | 5 (1885) | 113 | 88 (73, 105) | 0.78 (0.66, 0.94) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.87 |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 6 (2109) | 5 (2834) | 113 | 89 (77, 105) | 0.79 (0.67, 0.93) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.86 |

| Daclizumab | 2 (1336) | 1 (621) | 113 | 93 (76, 114) | 0.83 (0.68, 1.02) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and incoherence2 |

0.79 |

| Glatiramer acetate | 13 (4688) | 8 (4984) | 113 | 95 (81, 111) | 0.84 (0.72, 0.98) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.78 |

| Ocrelizumab | 4 (1421) | 2 (889) | 113 | 96 (76, 121) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.07) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.76 |

| Ozanimod | 2 (1774) | 0 (0) | 113 | 99 (66, 149) | 0.88 (0.59, 1.33) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 and imprecision4 |

0.67 |

| Interferon beta‐Ib | 6 (2674) | 1 (939) | 113 | 106 (88, 127) | 0.94 (0.78, 1.12) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 |

0.62 |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) | 17 (3692) | 7 (2384) | 113 | 110 (91, 131) | 0.96 (0.80, 1.15) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.57 |

| Natalizumab | 5 (1309) | 4 (2134) | 113 | 111 (90, 136) | 0.97 (0.79, 1.19) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.55 |

| Diroximel fumarate | 1 (253) | 0 (0) | 113 | 119 (2 6, 5 27 ) | 1.05 (0.23, 4.6 6 ) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.50 |

| Immunoglobulins | 3 (234) | 3 (407) | 113 | 119 (37, 375) | 1.05 (0.33, 3.32) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.49 |

| Peg‐interferon beta‐1a | 1 (1012) | 1 (1512) | 113 | 121 (75, 200) | 1.07 (0.66, 1.74) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.43 |

| Fingolimod | 10 (4088) | 5 (3774) | 113 | 119 (104, 136) | 1.05 (0.92, 1.20) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.41 |

| Teriflunomide | 7 (3207) | 4 (3044) | 113 | 122 (99, 148) | 1.08 (0.88, 1.31) |

Moderate Due to risk of bias3 |

0.39 |

| Cladribine | 2 (1294) | 2 (1935) | 113 | 123 (89, 171) | 1.10 (0.79, 1.52) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 and imprecision4 |

0.39 |

| Rituximab | 3 (404) | 2 (543) | 113 | 127 (82,195) | 1.12 (0.73, 1.73) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 and imprecision4 |

0.38 |

| Interferons | 1 (77) | 0 (0) | 113 | 183 (24, 1000) | 1.62 (0.21, 12.72) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.35 |

| Laquinimod | 7 (2278) | 7 (4360) | 113 | 12 7 (104, 155) | 1.12 (0. 92, 1.37) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.33 |

| Alemtuzumab | 3 (1188) | 0 (0) | 113 | 132 (96, 182) | 1.16 (0.85, 1.60) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision4 |

0.31 |

| Siponimod | 2 (1334) | 2 (1941) | 113 | 133 (105, 168) | 1.20 (0.95, 1.51) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 and imprecision4 |

0.26 |

| Ofatumumab | 4 (1153) | 2 (295) | 113 | 142 (99, 202) | 1.26 (0.88, 1.79) |

Low Due to risk of bias3 and imprecision4 |

0.24 |

| Azathioprine | 2 (243) | 1 (354) | 113 | 409 (86, 1000) | 3.62 (0.76, 17.19) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.07 |

Mixed RR: risk ratio obtained from network meta‐analysis

P score: the mean extent to which a treatment is likely to be better than an alternative intervention averaged over all interventions

Explanations for certainty of evidence: averaged over all interventions

Explanations for certainty of evidence:

- Major concerns regarding risk of bias in most studies (downgrade ‐2)

- Some concerns regarding incoherence (downgrade ‐1)

- Some concerns regarding risk of bias in most studies (downgrade ‐1)

- Some concerns regarding imprecision (downgrade ‐1)

- Major concerns regarding imprecision (downgrade ‐2)

- Some concerns regarding heterogeneity (downgrade ‐1)

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings 2: Immunotherapies compared to placebo for adults with multiple sclerosis.

| Immunotherapies compared to placebo for adults with multiple sclerosis | ||||||||

|

Population: adults with multiple sclerosis Interventions: immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory drugs Comparator: placebo Outcome: withdrawals due to adverse effects, mostly at 1 or 2 years Setting: specialist setting Equivalence criterion: RR between 0.67 and 1.50, also meaning that non‐inferiority with placebo was achieved if RR ≤ 1.50, with no more than 1 in 31 additional people withdrawing compared to placebo, at a baseline withdrawal occurrence of 1 in 16 patients (6.5%) | ||||||||

| Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Drug (vs. placebo) | No. of studies for network meta‐analysis (no. of participants in the drug‐specific arm) | No. of studies with direct comparison to placebo (total no. of participants in the drug‐specific arm and in the placebo arm) | Assumed placebo risk (per 1000) | Corresponding intervention risk (95% CI) |

Mixed RR (95% CI) |

Certainty of evidence | P score | |

| Diroximel fumarate | 1 (253) | 0 (0) | 65 | 25 (7, 84) | 0.38 (0.11, 1.27) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, imprecision2 and incoherence6 |

0.95 | |

| Alemtuzumab | 3 (1188) | 0 (0) | 65 | 40 (21, 75) | 0.63 (0.33, 1.19) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, imprecision2 and incoherence6 |

0.92 | |

| Ozanimod | 2 (1774) | 0 (0) | 65 | 67 (37, 123) | 1.06 (0.58, 1.93) |

Very low Due to risk of bias4, imprecision5 and incoherence6 |

0.76 | |

| Natalizumab | 5 (1309) | 4 (2134) | 65 | 80 (51, 124) | 1.20 (0.77, 1.85) |

Very Low Due to risk of bias4, imprecision2 and incoherence3 |

0.71 | |

| Corticosteroids | 2 (87) | 0 (0) | 65 | 68 (10, 464) | 1.05 (0.16, 7.14) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, imprecision2 and incoherence6 |

0.66 | |

| Ocrelizumab | 4 (1421) | 2 (889) | 65 | 84 (51, 136) | 1.32 (0.81, 2.14) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision2 |

0.64 | |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 6 (1948) | 4 (2578) | 65 | 88 (63, 123) | 1.34 (0.96, 1.86) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, imprecision2 and incoherence6 |

0.64 | |

| Teriflunomide | 7 (3207) | 4 (3044) | 65 | 89 (66, 120) | 1.37 (1.01, 1.85) |

Low Due to risk of bias4 and heterogeneity7 |

0.63 | |

| Methotrexate | 1 (31) | 1 (60) | 65 | 61 (1, 1000) | 0.94 (0.02, 46.7) |

Very low Due to risk of bias4, imprecision5 and incoherence6 |

0.61 | |

| Laquinimod | 7 (2278) | 7 (4360) | 65 | 83 (56, 124) | 1.42 (1.01, 2.00) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision7 |

0.60 | |

| Ofatumumab | 4 (1153) | 2 (295) | 65 | 99 (57, 171) | 1.50 (0.87, 2.59) |

Low Due to risk of bias4, imprecision2 and incoherence5 |

0.55 | |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Avonex) | 13 (4007) | 6 (2169) | 65 | 98 (72, 134) | 1.54 (1.13, 2.10) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and heterogeneity7 |

0.54 | |

| Rituximab | 3 (404) | 2 (543) | 65 | 106 (37, 303) | 1.63 (0.53, 5.00) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.50 | |

| Siponimod | 2 (1334) | 2 (1941) | 65 | 97 (55, 171) | 1.63 (0.96, 2.79) |

Very low Due to risk of bias4, incoherence5 |

0.49 | |

| Cladribine | 2 (1294) | 2 (1935) | 65 | 111 (59, 213) | 1.80 (0.89, 3.62) |

Very low Due to risk of bias4, imprecision2 and incoherence3 |

0.43 | |

| Glatiramer acetate | 15 (4752) | 9 (5032) | 65 | 114 (88, 147) | 1.76 (1.36, 2.26) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.43 | |

| Fingolimod | 11 (4118) | 5 (3774) | 65 | 115 (90, 147) | 1.79 (1.40, 2.28) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.41 | |

| Immunoglobulins | 7 (533) | 7 (1003) | 65 | 122 (66, 224) | 1.87 (1.01, 3.45) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, heterogeneity7, incoherence3 |

0.40 | |

| Mitoxantrone | 3 (182) | 2 (242) | 65 | 137 (33, 575) | 2.11 (0.50, 8.87) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1, imprecision5 and inconsistency3 |

0.39 | |

| Interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) | 16 (3886) | 7 (2693) | 65 | 135 (99, 185) | 2.15 (1.58, 2.93) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.29 | |

| Daclizumab | 2 (1336) | 1 (621) | 65 | 139 (84, 232) | 2.19 (1.31, 3.65) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.29 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1 (72) | 0 (0) | 65 | 251 (29, 1000) | 3.86 (0.45, 33.50) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and imprecision5 |

0.24 | |

| Interferons | 2 (124) | 0 (0) | 65 | 226 (62, 826) | 3.47 (0.95, 12.72) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and incoherence3 |

0.21 | |

| Interferon beta‐1b | 12 (3615) | 6 (2601) | 65 | 177 (122, 258) | 2.59 (1.87, 3.77) |

Low Due to risk of bias1 |

0.20 | |

| Peg‐interferon beta‐1a | 1 (1012) | 1 (1512) | 65 | 225 (94, 540) | 3.46 (1.44, 8.33) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and incoherence3 |

0.16 | |

| Azathioprine | 6 (369) | 4 (513) | 65 | 452 (167, 1000) | 6.95 (2.57, 18.78) |

Very low Due to risk of bias1 and incoherence3 |

0.04 | |

Mixed RR: risk ratio obtained from network meta‐analysis

P score: the mean extent to which a treatment is likely to be better than an alternative intervention averaged over all interventions

Explanations for certainty of evidence:

- Major concerns regarding risk of bias in most studies (downgrade ‐2)

- Some concerns regarding imprecision (downgrade ‐1)

- Major concerns regarding incoherence (downgrade ‐2)

- Some concerns regarding risk of bias in most studies (downgrade ‐1)

- Major concerns regarding imprecision (downgrade ‐2)

- Some concerns regarding incoherence (downgrade ‐1)

- Some concerns regarding heterogeneity (downgrade ‐1)

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Background

Description of the condition

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic immune‐mediated disease of the central nervous system. A total of 2.8 million people are estimated to live with MS worldwide (35.9 per 100,000 population). MS prevalence has increased in every world region in the last decade but gaps in prevalence estimates persist. The pooled incidence rate across 75 reporting countries is 2.1 per 100,000 persons/year, and the mean age of diagnosis is 32 years. Females are twice as likely to live with MS as males (Walton 2020).

MS is pathologically characterized by inflammation, demyelination, axonal and neuronal loss. Clinically, it is characterized by recurrent relapses or progression, or both, typically striking young adults and ultimately leading to severe disability. In 1996, the clinical course of MS was classified as relapsing‐remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), primary progressive MS (PPMS), and progressive relapsing MS (PRMS) (Lublin 1996). These forms of MS were used to design trials of interventions over two decades and to approve disease‐modifying treatments (DMTs) for relapsing MS. In 2013, an updated classification of MS forms was produced (Lublin 2014). The concept of disease activity was added based on the presence of clinical relapse or new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesions. The new classification included: (i) active or inactive relapsing MS, with or without worsening; and (ii) active or inactive primary or secondary progressive disease, with or without progression. Two new forms were also added, clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS), and PRMS was eliminated.

Twenty‐two DMTs have been approved over the past 20 years for treatment of RRMS. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved intravenous infusion of ocrelizumab also for PPMS, oral siponimod and oral ozanimod for CIS, RRMS and active SPMS (aSPMS), oral cladribine for RRMS and aSPMS. For the first time, by the beginning of 2019, these FDA's approvals allowed people with SPMS to be treated with DMTs.

Several national and international guidelines on the use of DMTs for MS have been produced after the 2013 classification (Lublin 2014). Recommendations vary amongst guidelines concerning specific drugs, reflecting — amongst other things — the differences in the regulatory agency's recommendations and different regional or local health policies (Montalban 2018; Rae‐Grant 2018).

Description of the intervention

We considered all immunotherapies that are used, whether approved or off‐label, for people with MS or CIS up to September 30, 2020.

Approved

Injectable medications

Beta interferons (Betaferon®; Extavia®; Rebif®; Avonex®) and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®, Brabio® or generic) were the first medicines approved for RRMS by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the US FDA in the years 1993 to 2002. Betaferon® and Extavia® are injected subcutaneously every other day. Rebif® is injected subcutaneously three times a week. Avonex® is injected into a muscle once a week. Copaxone® or Brabio® are injected subcutaneously daily, or three times a week at a higher dose. Glatiramer acetate generic (Glatopa®) is injected subcutaneously daily.

Peginterferon beta‐1a (Plegridy®) was approved for RRMS in 2014 by EMA and FDA. It is injected subcutaneously at a dose of 125 μg every two weeks.

Daclizumab (Zenapax® or Zinbryta®) was approved by the FDA and EMA in 2016 for treatment of RRMS. It is injected subcutaneously once monthly. The medicine was withdrawn in the European Union in 2018 due to the risk of serious and potentially fatal immune reactions affecting the brain, liver and other organs.

Ofatumumab (Kesimpta®) was approved by the FDA in 2020 for CIS, RRMS and active SPMS. It is injected subcutaneously at an initial dose of 20 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, followed by a dose of 20 mg, once monthly.

Oral medications

Fingolimod (Gilenya®) was approved for RRMS by the FDA in 2010 and EMA in 2011. It is taken as a capsule of 0.5 mg, once daily. The first dose is taken under medical supervision to monitor heart rate and blood pressure.

Teriflunomide (Aubagio®) was approved for RRMS by the FDA in 2012 and EMA in 2013. It is taken as a tablet at a dose of 7 or 14 mg, once daily.

Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®) was approved for RRMS by the FDA in 2013 and EMA in 2014. It is taken as a capsule of 120 mg, twice daily.

Laquinimod (Nerventra®) was approved for RRMS by the Russian Ministry of Health in 2013. EMA refused marketing authorisation in 2014 because the benefits of the medicine at the dose studied were not sufficient to outweigh the potential risks in people with MS. The FDA also refused approval.

Cladribine (Mavenclad® orMovectro®) was approved by EMA in 2017 and the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of highly‐active RRMS and active SPMS. It is taken as a pill at a dose of 1.75 mg/kg for up to five consecutive days in the first month and for up to five consecutive days in the second month, with the same course repeated a year later. This may need to be repeated at some point in the future.

Siponimod (Mayzent®) was approved by the FDA in 2019 and EMA in 2020 for treatment of CIS, RRMS and active SPMS. It is taken as a tablet and the maintenance dose is 1 mg or 2 mg daily.

Diroximel fumarate (Vumerity®) was approved by the FDA in 2019 for CIS, RRMS and active SPMS. It is administered as two 231 mg capsules a day.

Ozanimod (Zeposia®) was approved by the FDA and EMA in 2020 for CIS, RRMS and active SPMS. It is taken as a capsule at a maintenance dose of 0.92 mg, once daily.

Monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam®) was approved by the FDA in 2020 for CIS, RRMS and active SPMS. It is taken as a capsule at a maintenance dose of 190 mg (administered as two 95 mg capsules), twice a day orally.

Infused medications

Mitoxantrone (Novantrone®) was approved in 2000 by the FDA and EMA for the treatment of people with active RRMS and progressive MS. It is taken as a short intravenous infusion (approximately 5 to 15 minutes) of 12 mg/m2 every 3 months.

Natalizumab (Tysabri®) was approved in 2006 for people with highly active RRMS by EMA and the FDA. It is taken as an intravenous infusion via a drip at a dose of 300 mg, once every four weeks.

Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®) was approved for RRMS by EMA in 2013 and the FDA in 2014. It is taken as two treatment courses. The first course consists of intravenous infusions at a dose of 12 mg on five consecutive days (60 mg total dose). The second course is taken 12 months later and consists of intravenous infusions on three consecutive days (36 mg total dose). Some people may need a third or further infusion.

Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus®) was approved for RRMS and PPMS by the FDA in 2017 and by EMA in 2018. It is taken as an intravenous infusion at a dose of 300 mg/10 mL (30 mg/mL) in a single‐dose vial and then further infusions every six months.

Used off‐label

Azathioprine is used for the treatment of MS in many countries. The American guidelines (Rae‐Grant 2018) recommend the use of azathioprine for people with MS who, for financial or geographical reasons, do not have access to approved DMTs. The German guidelines recommend that, for people with MS who have a stable course under existing therapy with azathioprine, the therapy can be continued as long as the duration of the therapy is not exceeded by ten years. Azathioprine is taken as a tablet at a maintenance dose of 2 mg/kg per day.

Rituximab is not officially approved for treatment of MS, but its off‐label use for active RRMS and active SPMS is widely used in high‐, medium‐ and low‐income countries (Bourdette 2016). It is taken as an intravenous infusion in single doses of 500‐1000 mg two weeks apart, then, every 6 months, 500 to 1000 mg or 375 mg/m2 every week for four weeks. However, a treatment protocol has not been established.

Methotrexate is used in progressive forms of MS. It is taken as a tablet at a dose of 7.5 mg weekly (with 1 mg daily folic acid supplementation).

Cyclophosphamide has been administered to people with MS since 1991 on various schedules as an intravenous infusion at a dose of 1 g over three days, or 400 to 500 mg once daily over five days. The medicine has also been given orally at 2 mg/kg, once daily.

Intravenous immunoglobulins have been used for people with severe and frequent relapses, for whom other treatments have been contraindicated.

Long‐term corticosteroids have been proposed for the treatment of patients with MS since 1961, with controversial results. They have been administered by different schedules as pulsed periodic high‐dose methylprednisolone or oral continuous low‐dose prednisolone.

How the intervention might work

The harm profile of an intervention is strictly related to its mechanism of action, its modality of administration and pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and possibly pharmacogenetic aspects of drug response (Goodman 2006).

According to the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH 2015), adverse events (AEs) are classified in terms of system organ class (SOC), that is, by identifying the anatomical or physiological system affected by the AE itself.

Immunotherapies for MS belong to different pharmacological categories, have different modalities of administration (by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection, by infusion or by mouth) and have different metabolism; although all target the immune system, they are characterized by different effects, as follows: (1) immunomodulation (interferons, glatiramer acetate, pegylated interferon beta‐1a, dimethyl fumarate, monomethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, laquinimod, siponimod, ozanimod, immunoglobulins); (2) systemic immunosuppression, inducing a reduction in activation or efficacy of the immune system through cytostatic or cytotoxic effects (mitoxantrone, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, long‐term corticosteroids, cladribine, azathioprine, teriflunomide); and (3) selective immunosuppression, as with monoclonal antibodies or biological agents directed towards exactly defined antigens (natalizumab, fingolimod, alemtuzumab, daclizumab, rituximab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab).

These aspects must be considered when the safety profile of a drug is determined, because safety is usually a consequence of the drug’s primary pharmacological effect.

We might classify the main types and the etiopathogenesis of AEs of MS immunotherapies according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Organ Classes (MedDRA SOC), as follows.

Immune system disorders. All immunotherapies may cause acute or delayed systemic reactions due to allergic response, anaphylaxis, autoimmune disorder, cytokine release syndrome and serum sickness. Such reactions occur in particular during monoclonal antibody treatment (Lycke 2015) but also with immunomodulating agents, such as interferons. The exact process of flu‐like interferon syndrome is poorly understood but probably is related to increased endogenous pyrogens such as interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) (Martìnez‐Càceres 1998). Autoimmune diseases such as thyroiditis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis are more frequent in people treated with immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive drugs than in naive patients (Chouhfeh 2015).

Blood and lymphatic system disorders. Cytostatic effects or selective antagonism versus critical cell antigens might cause complete or partial myelosuppression, or lymphopenia. This latter AE occurs, for example, in fingolimod‐treated people, as the result of prevention of egress from secondary lymphoid tissues or following use of alemtuzumab, which selectively causes depletion of T and B lymphocytes. The mechanisms of these AEs during immunomodulating therapies (interferons, dimethyl fumarate) remain uncertain.

Infections and infestations. These might occur during immunosuppressive therapies that impair the immune system and induce immunosurveillance depression. Opportunistic infection such as progressive multi‐focal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in people treated with natalizumab seems to be due to inhibition of effector T‐cell trafficking from blood to CNS, which might favour local John Cunningham virus (JCV) replication (Van Assche 2005). PML has also been reported in people treated with fingolimod or dimethyl fumarate, probably resulting from similar causes. Other opportunistic infections such as herpes virus reactivation and tuberculosis are associated with immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapies (Williamson 2015).

Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions. Pregnancy and fetal damage have been reported with all therapies, although with different severity of harm or risk for reproductive potential and pregnancy category rating (Federal Register 2015). They are probably related to pharmacological effects on DNA and RNA replication (Amato 2015).

Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified. The association between MS and cancer has long been investigated but has led to conflicting results. No studies have reported an increased risk of cancer after long‐term exposure to injectable immunomodulatory drugs (interferons and glatiramer acetate). Several reports suggest an increase in cancer risk amongst MS patients treated with immunosuppressant drugs such as mitoxantrone, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. Because of their action on the immune system, and due to a lack of available long‐term data, a special warning of the potential risk of cancer accompanies the use of cladribine, fingolimod, natalizumab or alemtuzumab. Regulatory agencies recommend using risk management plans for fingolimod, natalizumab, alemtuzumab, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, daclizumab and ocrelizumab (Lebrun 2018).

AEs such as hepatic disorders are common to all types of drugs; others seem to be strictly related to a specific compound. Fingolimod causes transient activation of sphingosine‐1‐phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) in atrial myocytes, which is associated with a transient reduction in heart rate, while lung hyperreactivity leading to bronchospasms and airway constriction is mediated by S1P1 and sphingosine‐1‐phosphate receptor 3 (S1P3) activation. Alemtuzumab treatment is associated with risk of secondary autoimmunity due to reconstitution of the lymphocyte repertoire. Dimethyl fumarate‐treated people have experienced flushing and gastrointestinal problems, although the causes of these events remain uncertain (Bomprezzi 2015).

Many of these AEs are known and expected on the basis of a drug’s mechanism of action and pharmacodynamic aspects; other reactions remain of uncertain origin or appear during long‐term monitoring of people. Familiarity with the safety profile of each drug is critical for identification of potential mitigation strategies (Farber 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Although it is accepted that immunotherapies for people with MS may decrease disease activity, uncertainty regarding their relative safety remains. This uncertainty is due to the limited number of direct comparison trials, which provide the most rigorous and valid research evidence on the relative safety of different, competing treatments. A summary of the results, including both direct and indirect comparisons, may help to clarify the stated uncertainty.

There is uncertainty about what early treatment approach is best in MS, particularly in relapsing MS. Recently, there is a tendency to advocate the use of an early intensive approach starting high‐efficacy treatments earlier in relapsing MS (Hartung 2021; Prosperini 2020; Simpson 2021). However, this approach is limited by safety concerns and the preferred approach in clinical practice is the use of moderately effective drugs initially and switching to more efficacious and potentially higher risk agents if MS activity is insufficiently controlled. Consequently, there is an urgent need to evaluate if there are significant differences in the occurrence of serious adverse effects between first‐line (e.g. interferons beta or glatiramer acetate) and second‐line disease treatments (e.g. natalizumab, rituximab, or ocrelizumab).

Network meta‐analysis (NMA) is the most recent and best method that summarizes the evidence of multiple interventions within a single analysis and allows researchers to estimate the relative treatment effect between each two treatments, also those that have never been compared in a trial, by using direct and indirect evidence (Nikolakopoulou 2018). NMA also allows ranking interventions by benefits and harms (Salanti 2011), and thus is used in clinical guidelines to support recommendations (Kanters 2016).

Objectives

To compare the adverse effects of immunotherapies for people with MS or CIS, and to provide a ranking of these treatments according to their relative risks of adverse effects through NMA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all RCTs that examined one or more of the agents used in MS or CIS and compared them versus placebo or another active agent. We excluded RCTs in which a drug regimen was compared with a different regimen of the same drug without another active agent or placebo as a control arm. We excluded RCTs that compared treatment‐switch strategy versus continuing treatment.

Types of participants

We included participants 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of MS or CIS according to any accepted diagnostic criteria (Lublin 1996; McDonald 2001; Polman 2005; Polman 2011; Poser 1983). We included all participants regardless of sex, degree of disability or disease duration.

We considered MS type (relapsing‐remitting MS or clinically isolated syndrome, versus primary or secondary progressive MS) to be the main participant characteristics that could potentially threaten the transitivity assumption in NMAs.

Types of interventions

We included the following immunotherapies (even if they were not licenced in any country) used as monotherapies (i.e. we excluded combination treatments). We excluded interventions administered by a non‐approved route and not used in clinical practice. For example, cladribine is approved and used in clinical practice as an oral medication for the treatment of highly‐active relapsing or active progressive MS; we excluded studies in which cladribine was given by intravenous infusions.

Interferon beta‐1b;

Interferon beta‐1a (Avonex, Rebif);

Glatiramer acetate;

Pegylated interferon beta‐1a;

Ofatumumab;

Fingolimod;

Teriflunomide;

Dimethyl fumarate;

Cladribine;

Siponimod;

Diroximel fumarate;

Ozanimod;

Monomethyl fumarate;

Mitoxantrone;

Natalizumab;

Alemtuzumab;

Ocrelizumab;

Azathioprine;

Rituximab;

Methotrexate;

Cyclophosphamide;

Immunoglobulins;

Long‐term corticosteroids;

Daclizumab;

Laquinimod.

We included regimens as defined in the primary studies, irrespective of their dose and treatment duration. We considered that drug doses could be a source of heterogeneity and lead to violation of the transitivity assumption. We took a pragmatic approach and pooled all dosages in primary analyses, and conducted a sensitivity analysis restricted to dosages higher than the median of the study arms for each drug. We did not expect variation due to route of administration and treatment duration, since these are specific to each drug.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We estimated the relative risks of adverse effects at longest follow‐up of competing interventions according to the following primary outcomes:

Number of participants with any (one or more) serious adverse events (SAEs)

Number of withdrawals due to adverse events (AEs)

In this chapter, we use the term adverse event for an unfavourable or harmful outcome that occurs during, or after, the use of a drug, but is not necessarily caused by it (Peryer 2020), and a serious adverse event as any event or reaction, occurring at any dose, that results in death, a life‐threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, a persistent or significant incapacity or substantial disruption of the ability to conduct normal life functions, a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or important medical events based on appropriate medical judgment (ICH 2015; FDA 2020).

We considered that study duration post hoc would not be a source of heterogeneity since two‐thirds of the studies lasted between one and two years and about one fifth between two years and three years, which would allow the detection of most short‐ or medium‐term harms. Thus, we did not adopt a specific time frame for outcome collection.

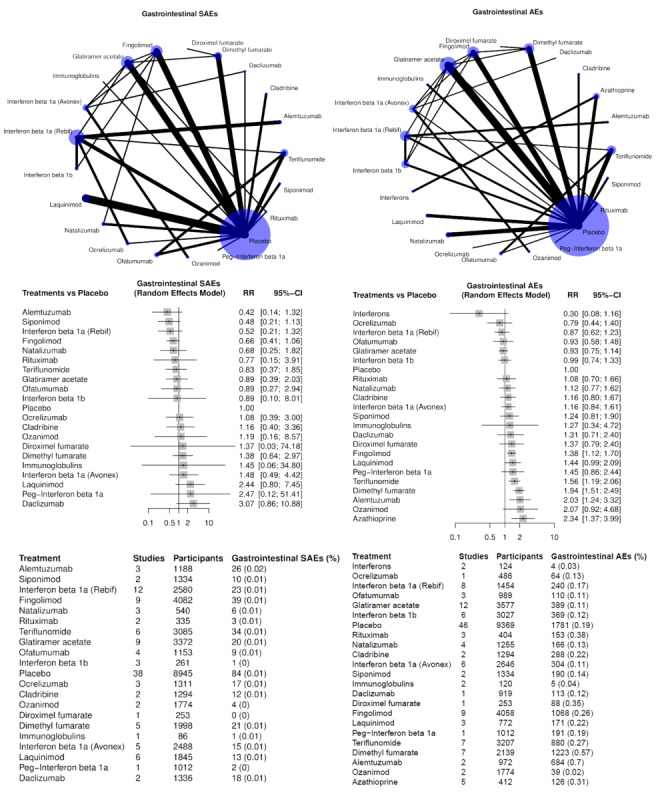

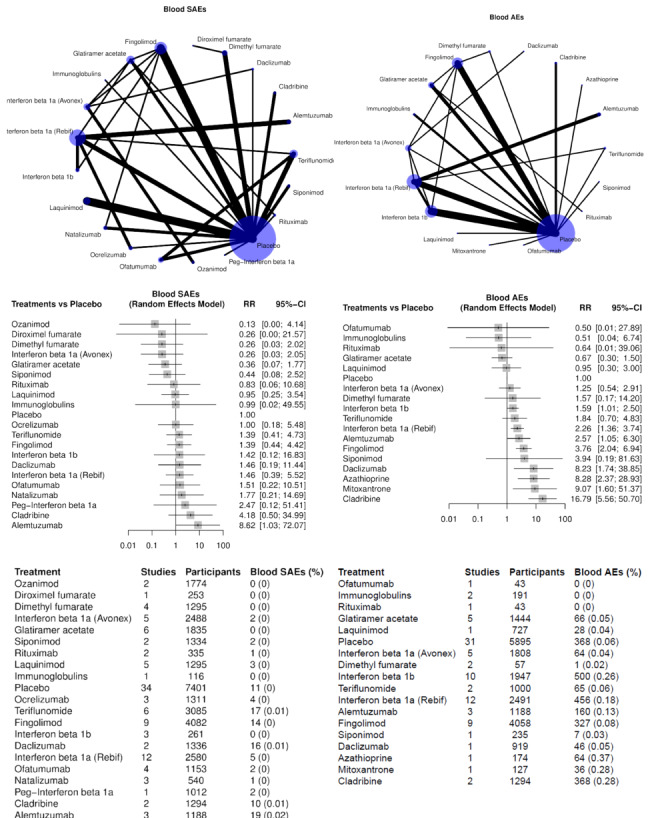

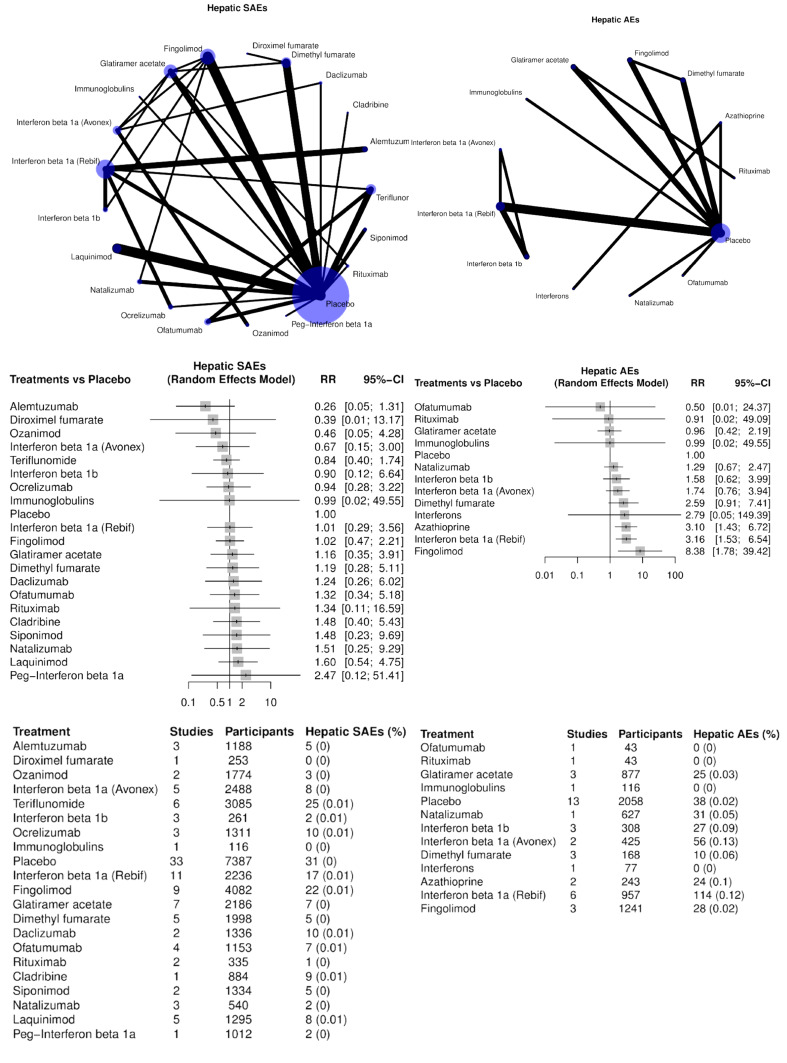

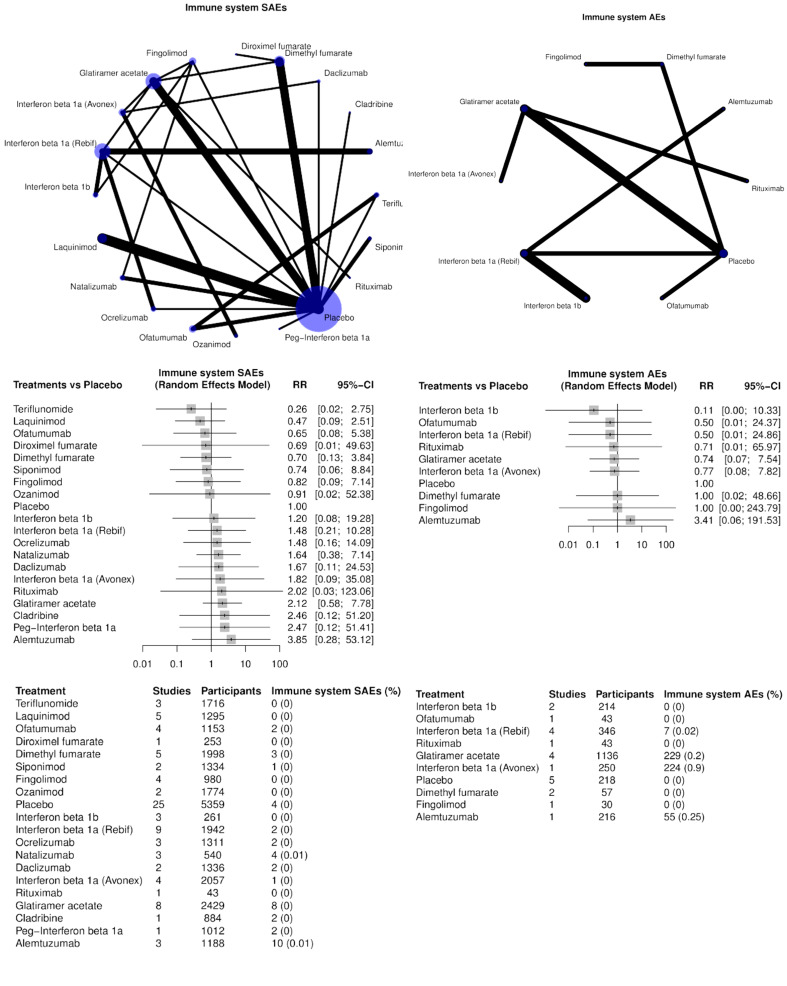

Secondary outcomes

We estimated the relative risks of adverse effects at longest follow‐up of competing interventions according to the following secondary outcomes, as classified by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Organ Classes (MedDRA SOC) (version 18.0) (ICH 2015).

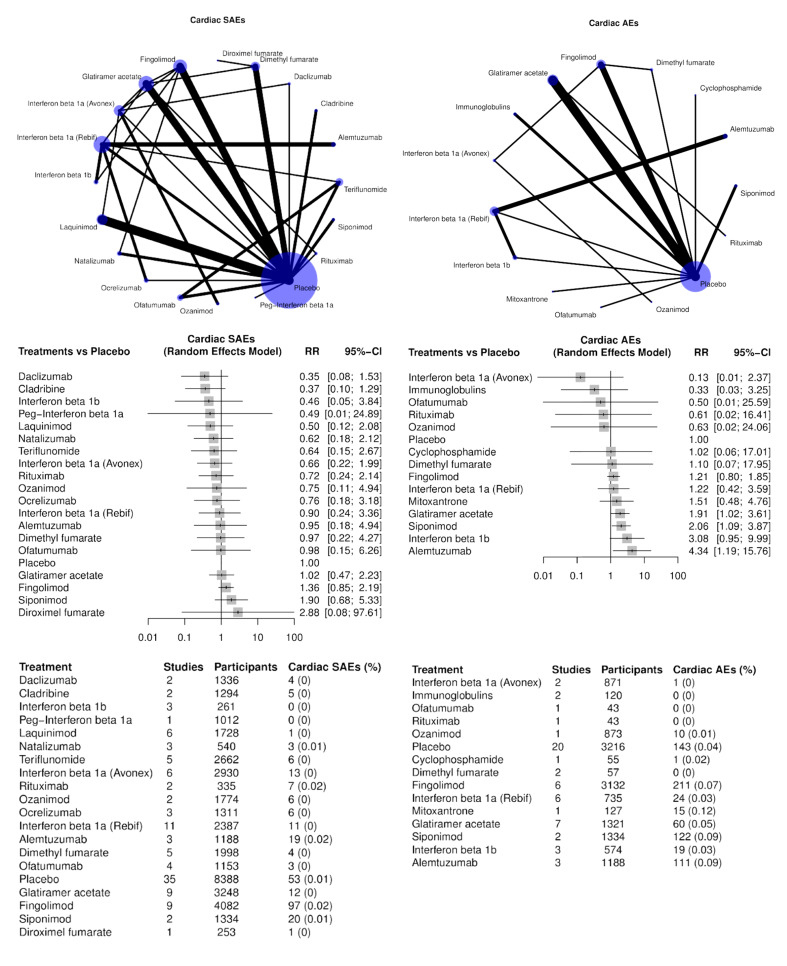

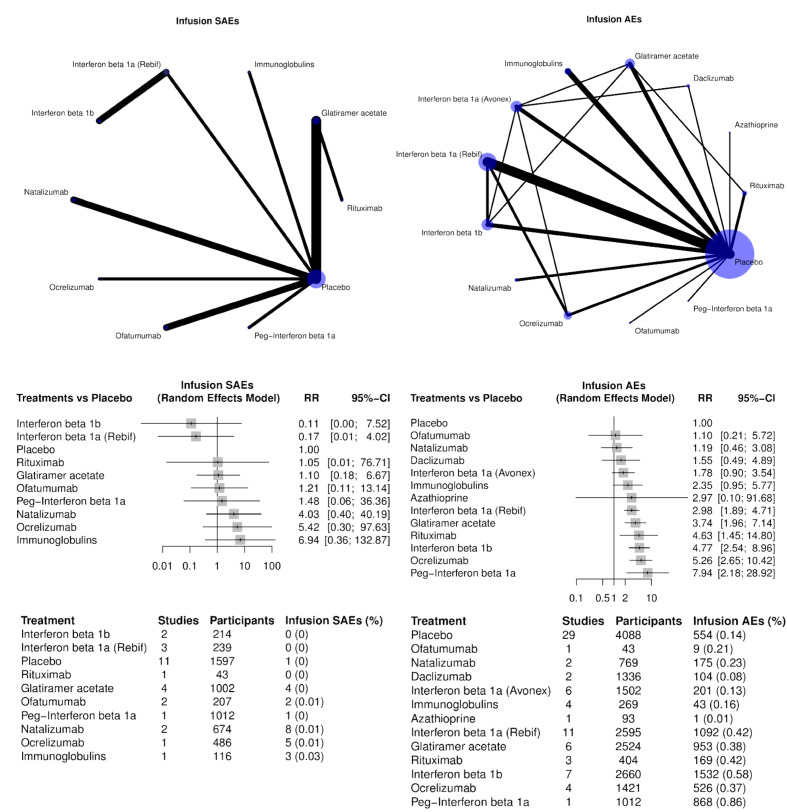

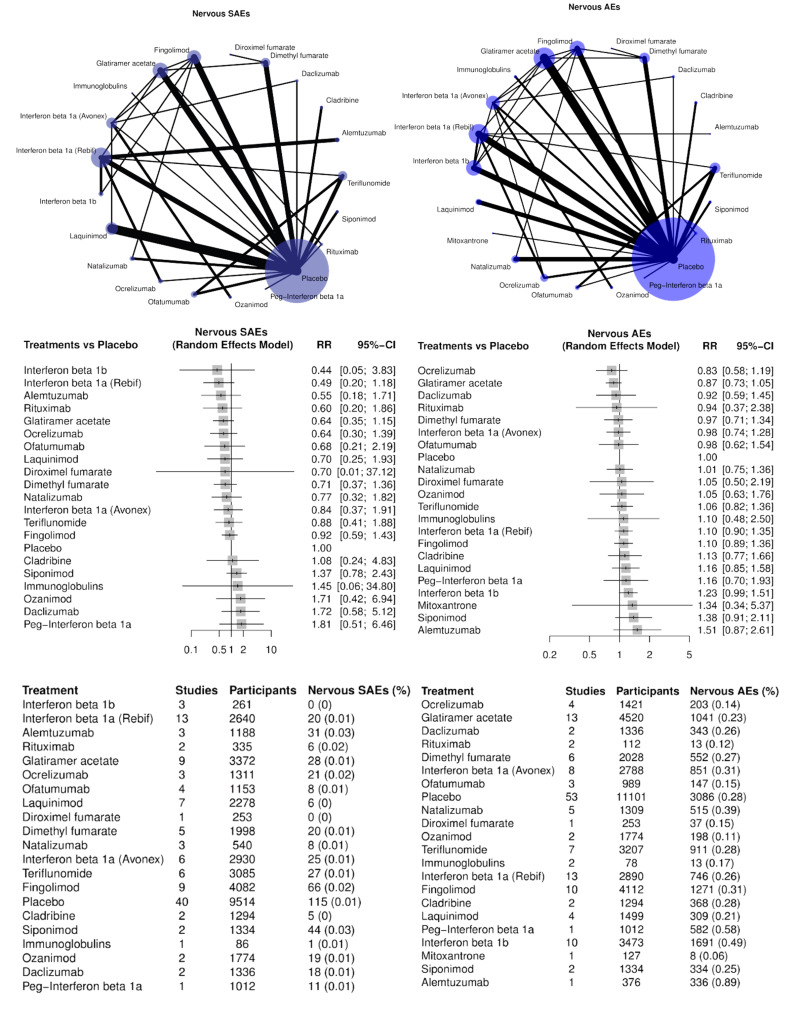

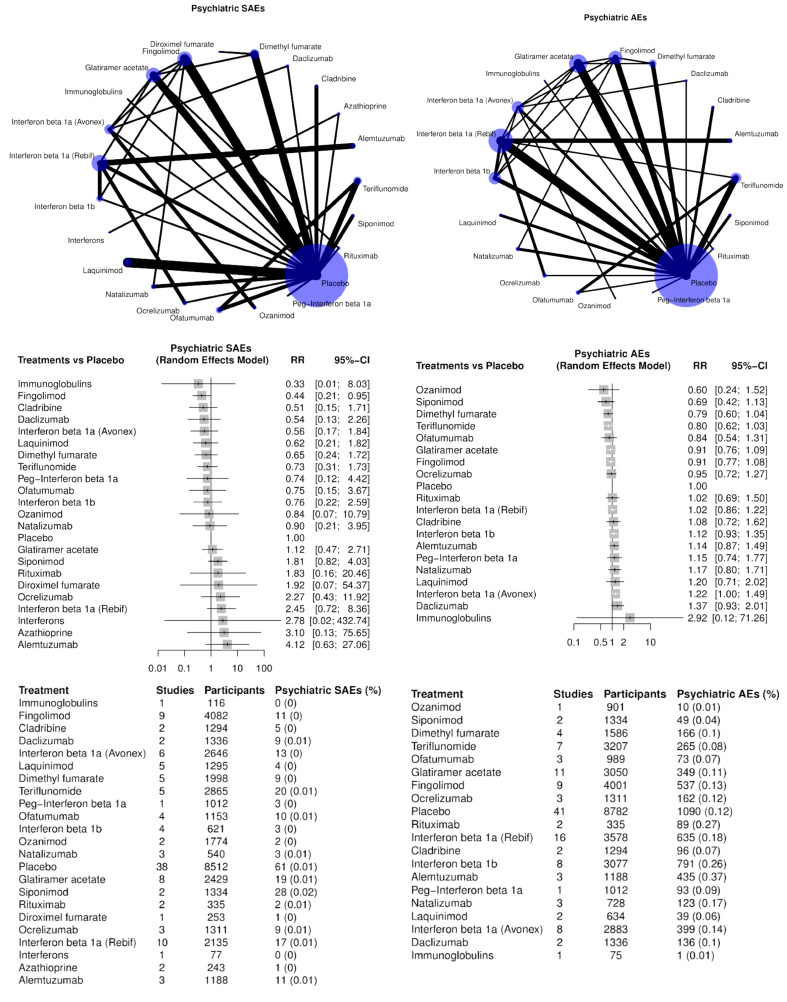

Cardiac disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Infections and infestations (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Infusion and injection site reactions (SAEs and AEs, separately) ; for intravenous medications, the number of infusion reactions were extracted and for subcutaneous or intramuscular medications, injection site reactions were extracted;

Nervous system disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Psychiatric disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Gastrointestinal disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Blood and lymphatic system disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Hepatobiliary disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Immune system disorders (SAEs and AEs, separately);

Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions;

Deaths;

Neoplasms.

We expressed all outcomes for each SAE category as percentages of participants with any (one or more) SAEs.

Search methods for identification of studies

This review fully incorporates the results of searches conducted until March 2022.

Electronic searches

We conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials without language, publication year or publication status restrictions up to 04 March 2022:

PubMed (1946 to 04 March 2022);

Embase.com (Elsevier) (1974 to 04 March 2022);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2022, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library;

CINAHL Complete EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1981 to 04 March 2022);

LILACS Bireme (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database; 1982 to 04 March 2022).

To identify RCTs and controlled clinical trials in the databases, we used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision); PubMed format (Lefebvre 2022) with a modification to truncate the search line for trial[ti] (line 70, PubMed strategy, Appendix 1). The modification to trial*[ti] increased the sensitivity of the filter slightly and enabled the search to capture a known study reference (Miller 1961) and post hoc or pooled analyses with eligible studies. We also used the Cochrane Embase RCT filter for Embase.com (Glanville 2019), the Cochrane CINAHL Plus RCT filter (Glanville 2019a), and the highly sensitive search strategy for clinical trials in LILACS (Manríquez 2008).

We searched the following trial registers on March 04, 2022:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (trialsearch.who.int);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

Search strategies for databases and trial registers are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also searched the following agency websites for pre‐ and post‐ marketing reports up to 04 March 2022:

United States Food and Drug Administration (fda.gov);

European Medicines Agency (ema.eurpoa.eu);

Australian Medicines Regulatory Authority ‐ Therapeutic Goods Administration (tga.gov.au).

Finally, we reviewed the references from relevant systematic reviews and included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to help assess the search results. Screen4Me comprises three components: known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and been labeled as an RCT or as Not an RCT; the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs; and, if appropriate, Cochrane Crowd – Cochrane’s citizen science platform where the Crowd help to identify and describe health evidence.

For more information about Screen4Me and the evaluations that have been done, please go to the Screen4Me webpage on the Cochrane Information Specialist’s portal (community.cochrane.org/organizational‐info/resources/resources‐ groups/information‐specialists‐portal). In addition, more detailed information regarding evaluations of the Screen4Me components is available (Marshall 2018; McDonald 2017; Noel‐Storr 2018; Thomas 2017).

After using the search strategy described above and the Screen4Me workflow to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review, two teams of two review authors each (GC and SF; MGL and MC) independently screened titles and abstracts and discarded studies that were not applicable; however, we retained studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on trials. Two teams of two review authors each (GC and SF; MGL and MC) independently assessed the retrieved abstracts and, when necessary, the full text of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. We compared multiple reports of the same study and used the most comprehensive report. We resolved discrepancies in judgment by discussion with a third review author (IT).

Data extraction and management

Two teams of two review authors each (GC and SF; MGL and MC) independently extracted data using a predefined data extraction form within an Excel spreadsheet. Disagreements were solved by discussion with a third review author (IT).

Outcome data

We extracted from each included study the number of participants who:

had any SAE;

withdrew because of any AE;

experienced any specific AE or SAE according to the MedDRA SOC (ICH 2015), as defined in the Types of outcome measures section;

were randomized; and

took one or more doses of the interventions included in the review.

We extracted arm‐level data. When data were not reported or were unclear in the primary studies, we consulted reports from FDA, EMA and TGA.

Data on potential effect modifiers

We extracted from each included study data on the following potential effect modifiers:

Population: age (range), forms of MS (CIS, RRMS, SPMS, PPMS and PRMS), disease duration (mean if provided or median), days since symptom onset and randomisation for CIS, baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score (mean), previous treatment with immunotherapies (no or yes/possible);

Duration of follow‐up;

Intervention: dose, frequency or duration of treatment;

Risk of bias: blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data;

Funding source.

Other data

We extracted data from each included study on the following additional information.

Study: first author or acronym, year of publication, recruitment period, publication type (full‐text publication, abstract publication, unpublished data);

Study design: inclusion criteria, sequence generation, allocation concealment, selective outcome reporting, early termination of trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of each included study by using the Cochrane criteria (Higgins 2011). These include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. We judged the risk of bias in each study on the basis of each criterion and classified the study as having ’low’, ’high’, or ’unclear’ risk of bias. We judged incomplete outcome data as showing a low risk of bias when numbers and causes of dropouts were balanced (i.e. in the absence of a significant difference) between arms and appeared to be unrelated to studied outcomes. We judged selective outcome reporting as showing a low risk of bias when study results included the three outcome categories relevant to the review, i.e. SAEs, AEs and withdrawals due to AEs.

To summarize the quality of studies across the two primary outcomes, we considered blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors and incomplete outcome data to classify each study as having low risk of bias when we judged all the selected criteria as having low risk of bias; high risk of bias when we judged at least one criterion amongst those selected as having high risk of bias; and moderate risk of bias in the remaining cases.

We assessed characteristics associated with monitoring and reporting AEs by considering two qualitative components that may have a large influence on the completeness of AE data: (1) whether authors defined SAEs according to an accepted international classification and reported the number of each specific type of SAE per arm; and (2) whether authors actively monitored for AEs asking participants about the occurrence of specific AEs in structured questionnaires or interviews or predefined laboratory tests at prespecified time intervals, or simply provided AEs that the study participants spontaneously reported on their own initiative (Ioannidis 2004; Peryer 2020). Passive surveillance of AEs leads to fewer recorded adverse events than active surveillance (Ioannidis 2004).

Two teams of two review authors each (GC and SF; MGL and MC) assessed the risk of bias of each study independently and resolved disagreements by discussion to reach consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

Relative treatment effects

We estimated, through pairwise meta‐analysis, the safety of competing interventions by using the risk or rate ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each outcome. We presented results from the NMA as summary relative effect sizes (RR) with 95% CIs for each possible pair of treatments.

Relative treatment ranking

We estimated ranking probabilities for all treatments at each possible rank for each intervention for each outcome. In the protocol, we had planned to determine a treatment hierarchy by using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and mean ranks (Salanti 2011). Since in the review phase we used the R package netmeta for analyses (see below for further details), we estimated ranking by means of P scores, a frequentist version of SUCRA (Rucker 2015). By definition, the P score of a treatment is the mean extent to which a treatment is likely to be better than an alternative intervention averaged over all interventions. More specifically, such an extent of certainty is calculated, under a normality assumption, as one minus the P value of the one‐sided test rejecting the null that the treatment is not better than the alternative intervention. As such, a P score gives the rank of a treatment within the range of all interventions, with 0 corresponding to the worst treatment and 1 to the best.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster and cross‐over trials have not been carried out to evaluate immunotherapies for the treatment of people with MS or CIS.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For multi‐arm trials, the intervention groups of relevance are those that could be included in a pairwise comparison of intervention groups, which, if investigated alone, would have met the criteria for inclusion of studies in the review. For example, if we identify a study comparing 'interferon beta versus natalizumab versus interferon beta plus natalizumab', only one comparison (interferon beta vs natalizumab) addresses the review objective, and no comparison involving combination therapy does. Thus, the 'interferon beta plus natalizumab' therapy group is not relevant to the review. However, if the study compared 'interferon beta‐1b versus interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) versus interferon beta‐1a (Avonex)', all three pairwise comparisons of interventions are relevant to the review. In this case, we treated multi‐arm studies as multiple independent two‐arm studies in pairwise meta‐analysis and accounted for the correlation between effect sizes in multi‐arm studies through NMA. Due to inclusion of multi‐arm studies, for treatment comparisons where direct evidence is available, the results (estimates) derived from pairwise meta‐analyses and NMA may differ.

Dealing with missing data

A likely scenario for assessment of effects of missing data on AE outcomes (i.e. rates of AEs) is not feasible, and on SAE outcomes is nonsense (i.e. assuming that participants who contributed to missing outcome data had a SAE); therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis including only trials with low risk of attrition bias and discussed the extent to which missing data could have altered results or conclusions of the review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Assessment of clinical heterogeneity within treatment comparisons

To evaluate the presence of heterogeneity derived from different characteristics of study participants, we had planned to assess differences in age, gender, MS type, and disease duration across trials using information reported in the Characteristics of included studies table. Since age, gender and disease duration were similar within MS type subgroups (relapsing‐remitting MS vs. progressive MS), we considered MS type (relapsing or progressive MS) only in a subgroup analysis.

Assessment of transitivity across treatment comparisons

We considered the following participants’ characteristics as a source of heterogeneity potentially threatening the transitivity assumption in the NMAs: MS type (relapsing‐remitting MS or clinically isolated syndrome, versus primary or secondary progressive MS), and prior use of disease‐modifying drugs (naive versus non‐naive).

Assessment of reporting biases

Given that it is not mandatory for investigators to publish results of clinical trials, it is difficult for review authors to obtain an estimate of the number of unpublished trials on MS. We presented the proportion of participants for whom each primary and secondary outcome was reported.

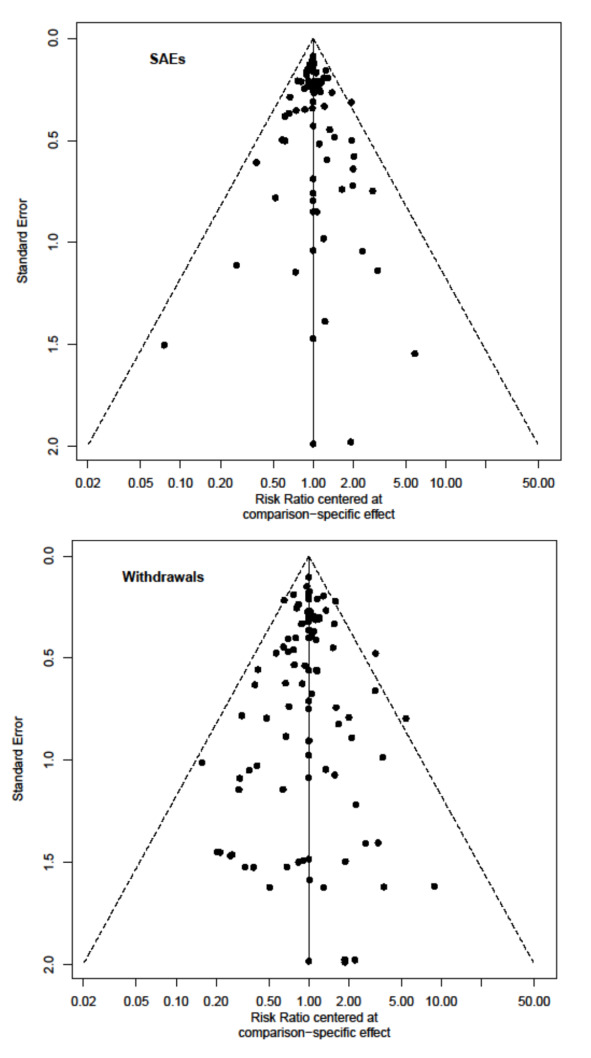

In the protocol, we had planned to evaluate the possibility of reporting bias by creating contour‐enhanced funnel plots (Peters 2008), which show areas of statistical significance and can help to distinguish reporting bias from other possible reasons for asymmetry. In this review, since each study estimated the relative effects of different interventions, we used the comparison‐adjusted funnel plot (Chaimani 2012; Chaimani 2013).

Data synthesis

Methods for direct treatment comparisons

We performed conventional pairwise meta‐analyses for each primary outcome using a random‐effects model for each treatment comparison with at least two studies (DerSimonian 1986). We have used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for pooling, adding an increment of 0.5 to each cell counts for studies with a zero cell count. Because of the large number of drugs included in the review, we presented pairwise meta‐analyses in the upper part of league tables to allow comparisons of direct and mixed estimates.

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

We performed NMAs using random‐effects models within a frequentist setting, assuming common heterogeneity across all comparisons, and we accounted for correlations induced by multi‐arm studies (Miladinovic 2014; Salanti 2012). These models enabled us to estimate the probability that each intervention is at each possible rank for each outcome, given the relative effect sizes as estimated in the NMA.

We had planned to perform NMA in Stata using the 'mvmeta' command (Chaimani 2013; Multiple‐Treatments Meta‐analysis (MTM); White 2011; White 2012). In the review phase, we performed NMAs using random‐effects models within a frequentist setting using the R package netmeta (Rucker 2015; Schwrtzer 2015). netmeta is based on a graph‐theoretical approach for NMA that was found to be equivalent to methods based on weighted least squares regression (Rucker 2012). We used forest plots to visualize mixed estimates of pairwise comparisons with placebo as a reference, and network graphs to represent the evidence network with edge widths proportional to the number of studies comparing two treatments and node sizes proportional to the number of studies assessing a treatment. A common between‐study variance was assumed in NMA models.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity

Assumptions when heterogeneity is estimated

In NMA, we assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across different comparisons.

Measures and tests for heterogeneity

Assessment of statistical heterogeneity in the entire network was based on the magnitude of the heterogeneity variance parameter (τ2), estimated by using NMA models (Jackson 2014).

Assessment of statistical inconsistency

We assumed that any patient who met the inclusion criteria was, in principle, equally likely to have been randomized to any of the eligible interventions.

Local approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To evaluate the presence of inconsistency locally, we used the method proposed by Dias (Dias 2010) and implemented in the netmeta package. This method is based on back‐calculation and infers the contribution of indirect evidence from the direct evidence and the output of a NMA.

Global approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To test global heterogeneity and inconsistency, we used the method proposed by Rucker (Rucker 2012) and implemented in the netmeta package. This method calculates the Q statistic measuring the deviation from consistency. The global Q statistic can be decomposed into the sum of within‐design Q statistics (corresponding to individual pairwise meta‐analyses) and the between‐designs Q‐statistic corresponding to the remaining design inconsistency between comparisons.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted subgroup analysis by prior disease‐modifying treatments to assess whether SAEs or withdrawals due to AEs varied between naive and non‐naive participants.

Other sources of heterogeneity

In the protocol, we had planned to take into account the predefined effect modifiers by performing meta‐regression or, if any, by discussing the extent to which they could have altered the results or conclusions of the review (age, gender, disease duration). Since age, gender and disease duration were similar within MS type subgroups (relapsing‐remitting MS versus progressive MS), we considered MS type (relapsing or progressive MS) only in subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

For each primary outcome, we performed planned sensitivity analyses with the inclusion of only trials with low risk of attrition bias. We also conducted two additional sensitivity analyses, one including only studies with doses that were higher than the median dose of each treatment across all studies and one including only studies on relapsing‐remitting MS or clinically isolated syndrome.

We had planned a sensitivity analysis on the exclusion of trials with a total sample size of fewer than 50 randomized participants, to detect potential small study effects. In the review, we explored the possibility of small‐study effects using the comparison‐adjusted funnel plot.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

In the protocol, we had planned to present seven outcomes in the SoF. In the review phase, due to the large number of outcomes and treatments, we decided to present two SoFs, one for each primary outcome (Table 1; Table 2). Comparisons of all drugs versus placebo were the focus of these SoFs.

In the two SoFs, we presented the main results of this review, according to recommendations provided in Chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.1.0) (Schünemann 2011) and according to Yepes‐Nuñez 2019. We provided estimates derived from the NMA in accordance with the methods of the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group (GRADE Working Group 2004). We included in the SoF tables the outcomes at longest available follow‐up for each drug.

We had planned to grade the certainty of evidence for each outcome by considering study limitations, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates and risk of reporting bias. In the review phase, we used the Confidence in Network Meta‐Analysis (CINeMA) as a methodological framework to evaluate the confidence in the results from NMAs (Nikolakopoulou 2020). This approach required further steps with respect to assess the certainty of evidence, and it covers six domains: (i) within‐study bias (referring to the impact of risk of bias in the included studies), (ii) reporting bias (referring to publication and other reporting bias), (iii) indirectness, (iv) imprecision, (v) heterogeneity, and (vi) incoherence. Heterogeneity and incoherence are two dimensions of inconsistency which refer, respectively, to the extent to which the prediction interval overlapped with the confidence interval, and the significance testing of the difference between direct and indirect evidence when both were available for comparison.

Decisions regarding the imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence require the specification of a range of equivalence for relative effects (RR) based on absolute effects. We selected a range of equivalence between RR = 0.67 and RR = 1.50. This choice was made post hoc by the authors after discussion of its implications on relative and absolute effects of the primary outcomes, since the CINeMA platform had been made available only after our protocol was published. The use of thresholds for clinically important effects of different sizes has recently been recommended also by the GRADE Working Group to rate imprecision in NMAs (Brignardello‐Petersen 2021).

Summary of Findings tables were not constructed for secondary outcomes, but we used the same threshold to contextualize the impact of our RR estimates on secondary outcomes. For some events that were very rare, we also presented the impact of doubling the risk of harms (RR = 2), also in terms of absolute estimates of effect.

Reporting

We reported the results of the review by completing the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) harms checklist (Zorzela 2016, available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/vujxa/?view_only=d90fac4ebe994de9985a2fb3acc21d84).

Results

Description of studies

For a full description of studies, see the Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

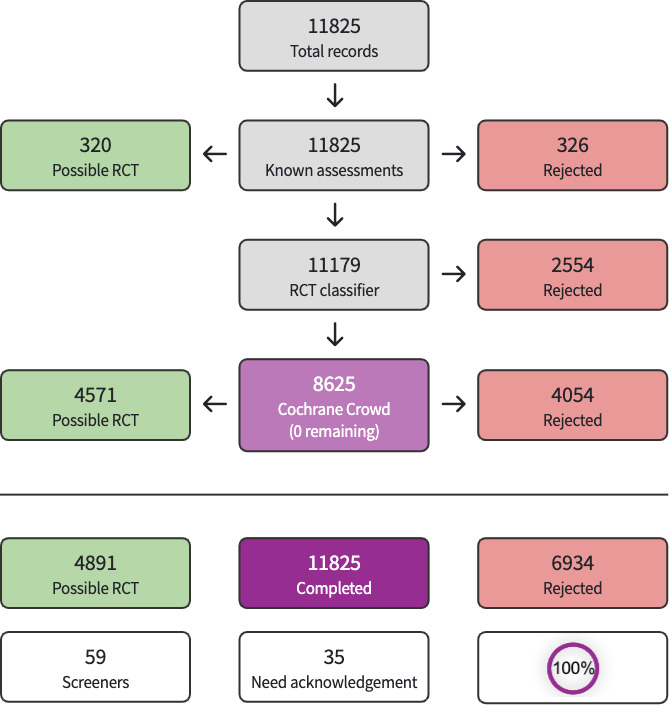

The search identified a total of 16,643 records. After removing duplicates in EndNote and the Cochrane Register of Studies, Cochrane's Screen4Me workflow helped to identify potential reports of randomized trials for the remaining 11,825 records. The results of the Screen4Me assessment process can be seen in Figure 1. 6934 records were rejected as describing studies with ineligible designs. The remaining 4891 records were assessed for eligibility by Cochrane Crowd. The Crowd rejected an additional 675 records, and we evaluated the remaining 4216 records for reported data on adverse effects.

1.

Screen4Me assessment process for eligible study designs.

From 4891 possible RCT records, Cochrane Crowd rejected an additional 675 records, and we evaluated the remaining 4216 records for reported data on adverse effects.

We provisionally selected a total of 191 studies as potentially fulfilling the inclusion criteria. After full‐text assessment, we included 123 studies and excluded 59 studies, together with nine ongoing studies. For a further description of our screening process, see the PRISMA study flow diagram (Figure 2).

2.

Prisma flow diagram

Included studies

One hundred and twenty‐three trials (57,682 participants; median sample size: 278; range: 13 to 2220) were included in the review. Included studies were published between 1961 and 2022 (median 2009). Ten (8.1%) trials included CIS only, seven (6.0%) trials PP only, 71 (57.7%) trials RR only, 11 (8.9%) trials SP only and, in 24 (19.5%) trials, different forms of MS. Forty (32.5%) trials included only naive patients. One hundred (81.3%) trials were funded by pharmaceutical companies. Forty‐six (37.4%) trials included three or more study arms, which were generally different doses or regimens, since only five studies included three interventions. Eighty‐four (68.3%) trials used a placebo comparator, 36 (29.3%) trials used an active comparator, and the remaining three (2.4%), both a placebo and an active comparator. Median follow‐up was 24 months (< 12‐month follow‐up from 22 studies, 12‐ < 24‐month follow‐up from 29 studies, 24‐month follow‐up from 51 studies, and > 24‐36‐month follow‐up from 21 studies).

Nine studies were excluded from the statistical analysis since they did not report any data on the predefined selected outcomes (Ashtari 2011; BPSM 1995; Calabrese 2012; Etemadifar 2006; Koch‐Henriksen 2006; Miller 1961; Mokhber 2014; Motamed 2007; Tubridy 1999).

We identified nine ongoing trials (Characteristics of ongoing studies). We will include these studies in a future update of this review.

Excluded studies

After full‐text review, we excluded 59 studies: six studies on interventions administered by route not approved/not used in clinical practice; 44 studies which did not meet the PICO of the review (38 wrong intervention, 3 wrong participants and 3 wrong study design), eight articles reporting secondary or pooled analyses of included studies, and one withdrawn study. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risks of bias in the included studies are summarized in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Considering our predefined criteria (blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors and incomplete outcome data) to assess the overall risk of bias of a study, we judged 8 (7%) out of 123 trials as having low risk of bias (ASCLEPIOS II 2020; CLARITY 2010; Comi 2001; Comi 2008; Fazekas 2008; GATE 2015; MIRROR 2018; Ziemssen 2017); we judged 42 (34%) as having moderate risk of bias (Achiron 1998; Achiron 2004; AFFIRM 2006; APEX 2019; APOLITOS 2021; BOLD 2013; Bornstein 1991; Boyko 2016; CHAMPS 2000; ETOMS 2001; EXPAND 2018; FUMAPMS 2021; GALA 2013; Goodkin 1995; IFNB MS Group 1993; IMPROVE 2010; Johnson 1995; Kappos 2006; Knobler 1993; Leary 2003; Lewanska 2002; Miller 1961; Miller 2003; Montalban 2009; Noseworthy 2000; O'Connor 2006; OLYMPUS 2009; Pakdaman 2007; Polman 2005; PRISMS 1998; RADIANCE 2019; REFLEX 2012; Saida 2012; Saida 2017; SELECT 2013; SPECTRIMS 2001; SUNBEAM 2019; TEMSO 2011; TOPIC 2014; TRANSFORMS 2010; Tubridy 1999; Wolinsky 2007); and we judged 73 (59%) as having high risk of bias (ADVANCE 2014; ALLEGRO 2012; Andersen 2004; ARPEGGIO 2020; ASCEND 2018; ASCLEPIOS I 2020; Ashtari 2011; ASSESS 2020; AVANTAGE 2013; BECOME 2009; BENEFIT 2006; BEYOND 2009; Bornstein 1987; Boyko 2017; BPSM 1995; BRAVO 2014; British and Dutch 1988; Calabrese 2012; CAMMS223 2008; CARE‐MS I 2012; CARE‐MS II 2012; CCMSSG 1991; Cheshmavar 2021; CombiRx 2013; CONCERTO 2022; CONFIRM 2012; DECIDE 2015; DEFINE 2012; Ellison 1989; Etemadifar 2006; Etemadifar 2007; European Study Group 1998; EVIDENCE 2002; EVOLVE‐MS‐2 2020; Fazekas 1997; FREEDOMS 2010; FREEDOMS II 2014; Ghezzi 1989; GOLDEN 2017; Goodkin 1991; Hartung 2002; Hauser 2008; Hommes 2004; IMPACT 2002; INCOMIN 2002; INFORMS 2016; Kappos 2008; Kappos 2011; Koch‐Henriksen 2006; Likosky 1991; MAIN TRIAL 2014; Masjedi 2021; Milanese 1993; Millefiorini 1997; Mokhber 2014; Motamed 2007; MOVING 2020; MSCRG 1996; NASP 2004; OPERA I 2017; OPERA II 2017; ORACLE 2014; ORATORIO 2017; OWIMS 1999; Pohlau 2007; PreCISe 2009; PROMESS 2017; REFORMS 2012; REGARD 2008; REVEAL 2020; TENERE 2014; TOWER 2014; Van de Wyngaert 2001).

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Serious AE definitions were not applicable when the study did not report serious AE (empty row).

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study. Serious AE definitions were not applicable when the study did not report serious AE (empty cells).

Allocation

No study was considered at high risk of bias regarding sequence generation, 29 (24%) were unclear, and 94 (76%) at low risk. Three (2%) studies were considered at high risk of bias (mainly for open allocation), 59 (48%) were unclear, and 61 (50%) at low risk for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Thirty‐three studies (27%) were considered at high risk of performance bias (mainly for single‐blinding), 51 (41%) were unclear, and 39 others (32%) trials were at low risk. Twenty‐seven (23%) studies were considered at high risk for detection bias (mainly for open‐label design), 79 (64 %) were unclear, and 14 (12%) trials were at low risk. Overall, we judged seven studies (6%) as having low risk in both domains.

Incomplete outcome data

Forty‐seven trials (38%) were considered at high risk of attrition bias (because of unbalanced numbers, reasons for dropouts, or both between the comparison groups); 15 (12%) were at unclear risk, and 61 trials (50%) at low risk.

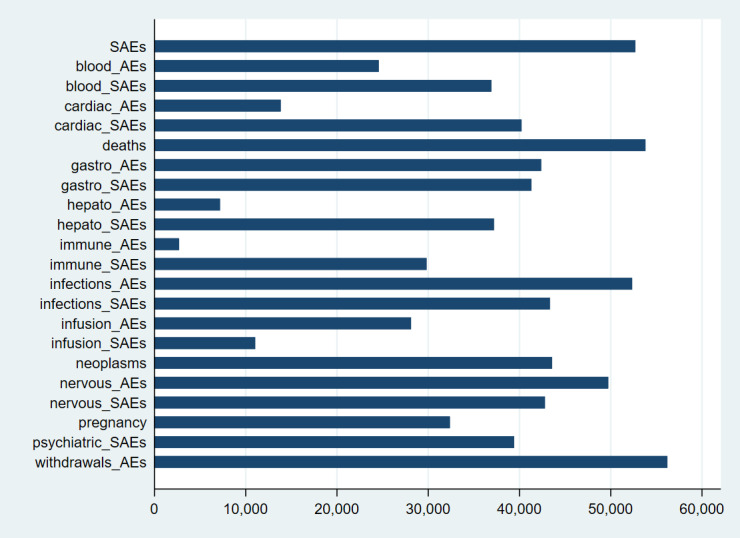

Selective reporting

Reporting of our primary outcomes, SAEs and withdrawals due to AEs, was explicit in most studies, totalling respectively 51,833 (89.9%) and 55,320 (95.9%) participants out of 57,682 patients in all studies. On the other hand, many studies did not report explicitly our secondary outcomes, types of SAEs or AEs. In Figure 5, we report the total number of participants in studies reporting each type of AEs. We used available data in analyses and did not attempt missing imputation techniques.

5.

Reporting of adverse events in studies: bar length corresponds to the number of participants for which an adverse event was reported.

Definition of serious adverse events

Only 37% of trials had adequate definition and reporting of SAEs according to the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). In ClinicalTrials.gov (Study Results), these trials reported the total number of serious clinical or laboratory‐determined adverse effects and gave numbers of specific types of serious adverse events per arm. There was an improvement in reporting after the release of the CONSORT checklist, with new recommendations about reporting harms‐related issues in randomized trials (Ioannidis 2004).

Forty‐eight trials (39%) did not report any definition of SAEs and key information is missing on criteria used to assess and select SAEs per arm. The majority of these trials reported the total number of SAEs but did not specify their types. Two trials (2%) reported only generic statements without specific numbers.

Twenty‐seven trials (22%) did not provide data on SAEs.

Method of AE monitoring

We assessed whether authors actively monitored for AEs, or simply provided AEs that the study participants spontaneously reported on their own initiative. We judged that the majority (58%) of trials specified the time frame of surveillance and did active monitoring for AEs because participants were asked about the occurrence of specific adverse events in questionnaires or interviews, or predefined laboratory tests were performed at prespecified time intervals. Different methods were adopted for monitoring the adverse effects of each drug with variable reliability of the different approaches. The median duration of the surveillance period was 24 months. We found data to assess our judgment in the published article, in the study protocol, or in ClinicalTrials.gov. Forty‐four (36%) of included studies did not report the method used to monitor adverse events, and so we classified them as having 'unclear risk'. Seven studies were classified as having high risk because the recorded adverse events were those that the study participants spontaneously reported on their own initiative.

The majority of studies reported only the adverse events observed at a certain frequency or rate threshold (for example, > 3%, > 5%, or > 10% of participants).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged 117 (95%) trials as having low risk of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

The dataset used in the analyses is available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/vujxa/?view_only=d90fac4ebe994de9985a2fb3acc21d84.

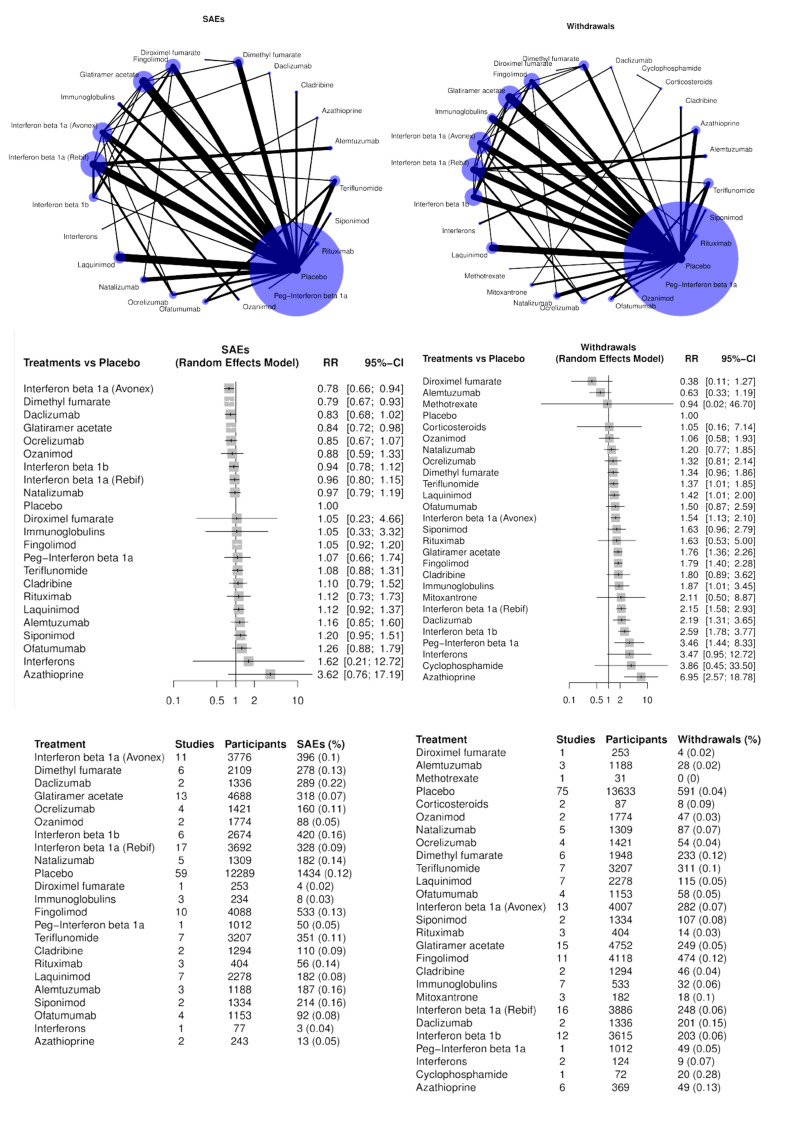

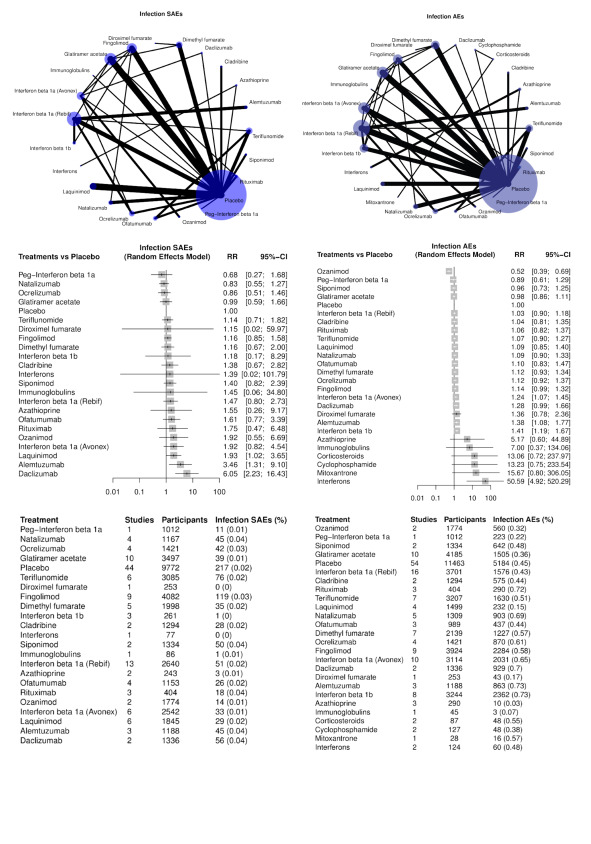

Primary outcome: SAEs

Eighty‐four (68%) studies, including 5696 (11%) events in 51,833 (89.9%) of 57,682 participants, provided data for this analysis (Figure 6). The raw overall SAE frequency was 10.3% and was used as an assumed risk in Table 1. Adopting a 1.5 RR threshold for clinical importance, the corresponding increase in absolute risk would be 5.5% (1 more SAE in 18 participants). Table 1 shows the number of studies (participants or events) for each drug in the NMA on SAEs, together with relative and absolute effects (95% CIs) with an assumed risk estimate of 110 SAEs per 1000 people. This table also presents the certainty of evidence for each drug versus placebo and reasons for downgrading it.

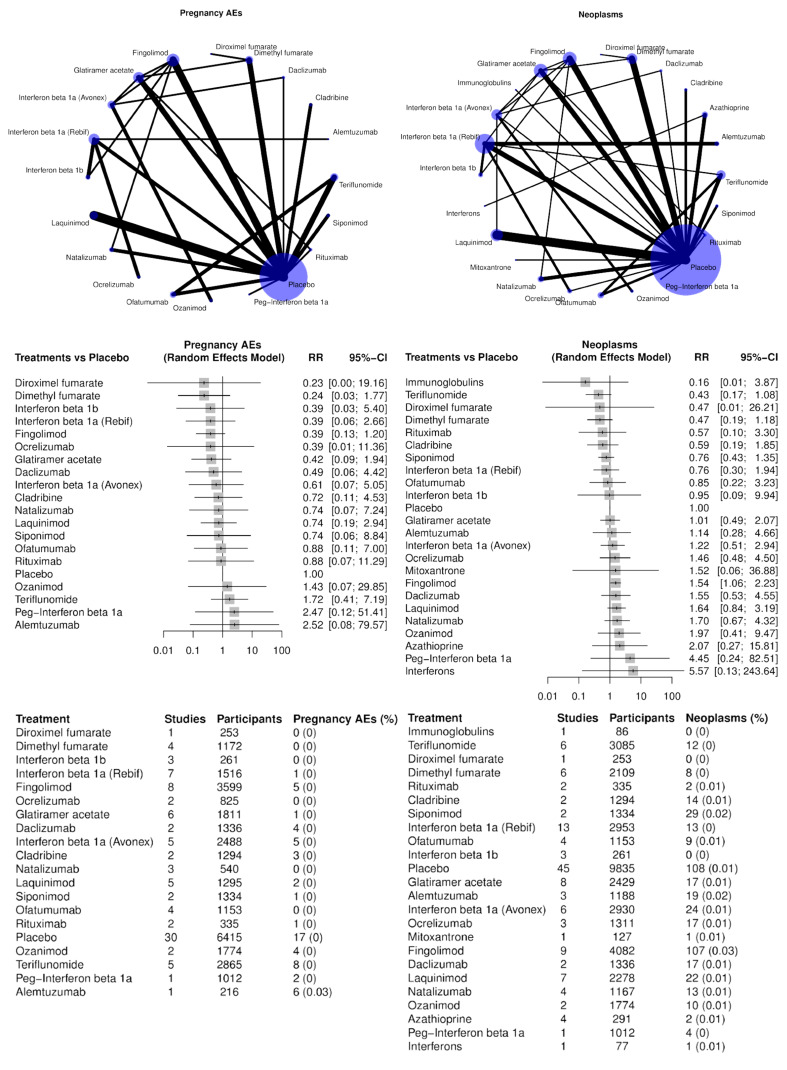

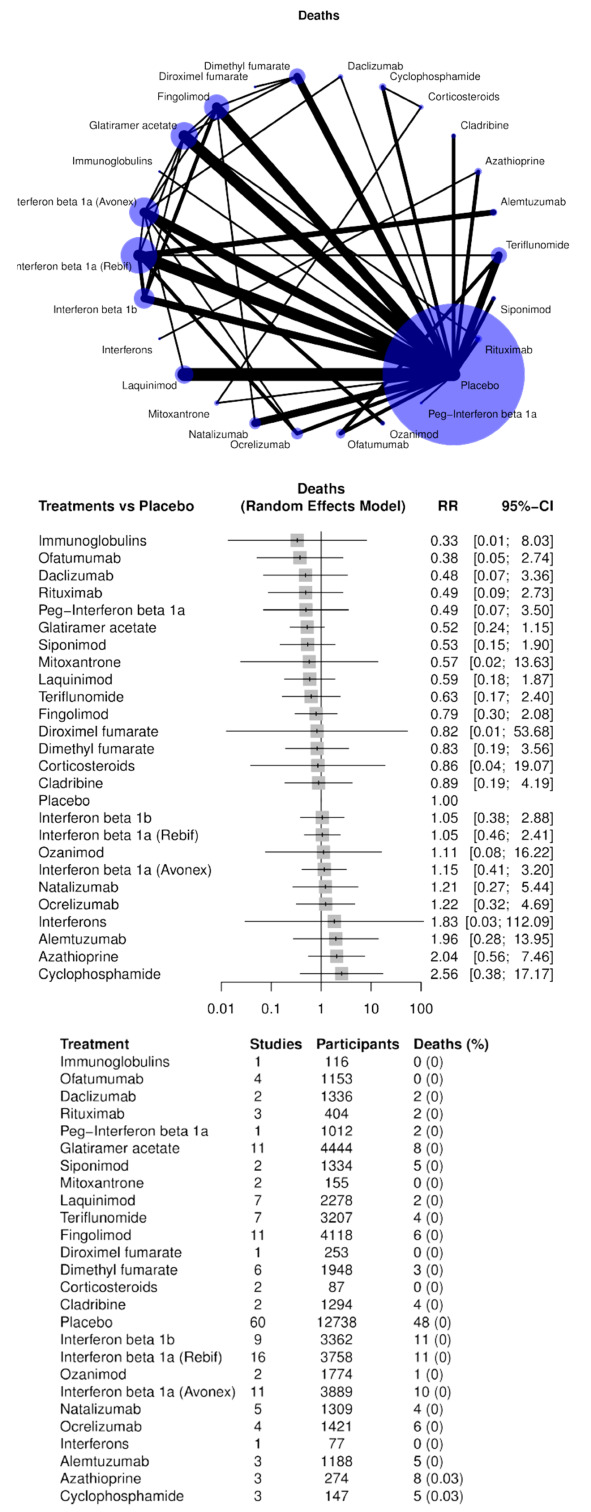

6.

NMA estimates for primary outcomes serious adverse events (SAEs, left) and withdrawals (right). In the summary tables at the bottom, % stands for the ratio between the number of events and the number of participants comprised between 0 and 1.

Three drugs may decrease SAEs compared to placebo (RR, 95% CI):

low‐certainty evidence for interferon beta‐1a (Avonex) (0.78, 0.66 to 0.94), dimethyl fumarate (0.79, 0.67 to 0.93) and glatiramer acetate (0.84, 0.72 to 0.98).

Several drugs met our non‐inferiority criterion versus placebo (an upper 95% CI RR limit of 1.5 or lower):

moderate‐certainty evidence for teriflunomide (1.08, 0.88 to 1.31);

low‐certainty evidence for ocrelizumab (0.85, 0.67 to 1.07), ozanimod 0.88 (0.88, 0.59 to 1.33), interferon beta‐1b (0.94, 0.78 to 1.12), interferon beta‐1a (Rebif) (0.96, 0.80 to 1.15), natalizumab (0.97, 0.79 to 1.19), fingolimod (1.05, 0.92 to 1.20) and laquinimod (1.06, 0.83 to 1.34);

very low‐certainty evidence for daclizumab (0.83, 0.68 to 1.02).

Non‐inferiority with placebo was not met due to imprecision for the following drugs, although none of the drugs with effects in the direction of more SAEs increased harm to a statistically significant extent:

low‐certainty evidence for cladribine (1.10, 0.79 to 1.52), siponimod (1.20, 0.95 to 1.51), ofatumumab (1.26, 0.88 to 1.79) and rituximab (1.01, 0.67 to 1.52);