Abstract

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is an aggressive bone marrow cancer with disparate outcomes. Data on patient outcomes in real world settings outside of clinical trials is limited. The current study reports on outcomes for 137 ALL patients who received an adult induction and consolidation regimen derived from the CALGB 10102 trial modified without alemtuzumab. Of the 137 patients, 32 were < 40 years old, 52 were between 40 and 59, and 53 were ≥ 60 years old. Overall, 109 (79.6%) patients achieved a complete remission (< 40: 96.1%, 40–59: 86.5%, and 62.3% ≥ 60 (p = 0.0002)). Progression free survival for the entire cohort was 13.5 months and by age was 19.8 months for less than 40, 23.4 months for 40 to 59 and 6.7 months for ≥ 60; p = 0.0002. Median survival was 22.1 months for the entire cohort (32.9 months for ages < 40, 26.6 months ages 40–59, 7.8 months ≥ 60, p < 0.001).

Keywords: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Therapeutics, Chemotherapy Treatment Regimens, Real-World Outcomes

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a malignancy characterized by clonal expansion and proliferation of lymphoblasts manifesting in heterogeneous presentations ranging from bone marrow involvement to extra-nodal organ and central nervous system infiltration [1]. The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2021 there will be 5690 new cases of ALL and 1580 deaths in the United States [2]. While there have been great gains in the survival outcomes for children diagnosed with ALL, adults have not seen the same level of gains. Pediatric-inspired regimens have led to improved outcomes in young adults [3, 4], however; older patients continue to have poor outcomes. Currently there is no standard treatment regimen for adults greater than the age of 40 and the options are controversial and inconsistent across age groups [5]. While there has been recent evidence published supporting safety and efficacy of treatment with pediatric-inspired protocols for adults with age’s ≤ 60 years, the quality of evidence for patients ≥ 40 years of age with these protocols is not as robust [6].

Treatment for ALL requires induction, consolidation, and maintenance therapy with the administration of CNS prophylaxis throughout [7]. The induction regimens for patients with ALL include corticosteroids, vincristine, an anthracycline, and asparaginase with cyclophosphamide and cytarabine as common additions [8]. Complete remission (CR) rates from induction therapy in the range of 80–90% have been reported in most studies of adult ALL [5]. However, many patients who achieve complete remission will relapse. Relapse is the most common cause of treatment failure and, if it occurs, reduces long-term survival rates to less than 10% [5].

Regimen selection in the adult population remains controversial. Most data are derived from single institution experience from early phase clinical trials with carefully selected patients and may not reflect outcomes in a real-world setting. To assess outcomes of adult patients treated outside of a clinical trial, data on adult ALL patients treated as per a modified CALGB 10102 protocol without alemtuzumab were analyzed. The CALGB 10102 trial tested the addition of alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, on survival across different age groups. The results of this study were presented in abstract form and did not support the addition of alemtuzumab [9]. Following the completion of accrual to 10102, adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) at Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center (WFBCCC) with a new ALL diagnosis received treatment according to the CALGB 10102 protocol without alemtuzumab. There is currently limited literature about the outcomes of adult patients who receive therapy outside of a clinical trial. Our objective was to report the outcomes of those patients who received a modified version of the CALGB 10102 regimen off trial.

Patients and methods

Study design

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University (IRB Number IRB00038799). One hundred thirty-seven ALL patients who received the CALGB10102 regimen off trial at WFB-CCC from June 1, 2007 to December 1, 2020 were reviewed. Additional criteria for inclusion were age 18 years or older and diagnosis of ALL on bone marrow aspirate and/or tissue diagnosis. Information reviewed included a detailed medical history and disease specific outcomes. In addition, data on pertinent covariates including age, demographic data, tumor biology, white blood cell count, LDH, and comorbid conditions were collected. Patients were identified from the tumor registry and assessed for the inclusion criteria. Patients were categorized into Unfavorable, Intermediate, and Favorable cytogenetic risk groups based on the NCCN guidelines. Unfavorable risk group included hypoploidy (< 44 chromosomes and/or DNA index < 0.81); t (v; 11q23): MLL rearranged; t (9; 22) (q34; q11.2): BCR-ABL (defined as high risk in the pre-TKI era); Complex karyotype (5 or more chromosomal abnormalities). Favorable included hyperploidy (51–65 chromosomes and/or DNA index > 1.6); t (12:21) (p13; q22): TEL-AML1. A total of 327 charts were identified and 190 charts were excluded for criteria of age < 18 (75); alternative protocol/trial (110) and no treatment (5).

Diagnosis and treatment

Patients were diagnosed according to the WHO criteria for acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma [1]. The modified CALGB 10102 regimen followed was comprised of an induction cycle, Module A, that consisted of daily dexamethasone on days 1–7 and days 15–21 (second week of steroids only in patient’s ages < 60), daily daunorubicin on days 1–3, weekly vincristine on days 1,8,15, 21, asparaginase on days 5, 8, 11, 15, 18, 22, and cyclophosphamide on day 1 [for patients younger than 60 years of age]. G-CSF was given daily starting on day 4 and continued until count recovery. Upon establishment of remission, consolidation therapy began with module B consisting of intrathecal methotrexate, intravenous methotrexate, high-dose cytarabine given on days 1–3, cytoxan given on day 1 and L-asparaginase given days 15, 18 and 22. Upon count recovery, this was followed by module C which consisted of doses of IV, oral, and IT methotrexate given every two weeks on days 1, 15 and 29 and vincristine given days 1, 15, and 29. Upon completion of module C, patients repeated each of the 3 modules again for a total of 6 courses. Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph +) patients received a tyrosine kinase inhibitor either imatinib or dasatinib starting on day 15 of module A and continued during all courses and maintenance therapy. After completion of all planned consolidation therapy, patients still in remission began maintenance therapy with POMP (6-mercaptopurine [Purinethol] daily, vincristine [Oncovin] day one, methotrexate weekly, and prednisone days 1–5 every 28) with a goal of completing a total of 2 years of treatment. Neutropenic prophylaxis was used during Modules A and B and consisted of fluconazole, a fluoroquinolone and acyclovir until ANC recovered to ≥ 500/μL. Pneumocystis prophylaxis with double strength Bactrim on every Monday, Wednesday and Friday was given throughout all consolidation therapy except when high dose methotrexate was given. If cerebrospinal fluid was involved, repeat doses of intrathecal therapy were administered until clearance. Complete remission was defined by < 5% blasts in the marrow and no morphologic evidence of leukemia along with an ANC > 1,000/μL, platelet count > 100,000/μL and freedom from blood transfusions.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics (means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, or counts with percentages) were calculated by age group and overall to describe the characteristics of subjects on the CALGB 10102 regimen. Fisher’s exact test was used to look for associations between comorbidities and remission status. Overall Survival was calculated as the start of induction chemotherapy until death or date of last follow-up. Kaplan–Meier estimation was used to estimate survival curves and median survival. Comparisons between age groups for CALGB 10102 were done using log-rank tests. Multivariable analyses of prognostic factors used the Cox proportional hazard models for overall survival with age, cytogenetic risk, and white blood cell counts as covariates. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. Briefly, a total of 137 adult patients met inclusion criteria. The median age of the cohort was 53 (range: 19–86), 126 patients (91.9%) had B-cell ALL and 11 (8.1%) had T-cell ALL. Six patients (4.3%) had central nervous system involvement at the time of diagnosis. Cytogenetics were favorable in 8 patients (5.8%), intermediate in 85 patients (62%), and unfavorable in 31 (22.6%) with the remaining 13 (9.5%) patients having incomplete cytogenetic prognostic data. The cohort was primarily Caucasian (89.8%) reflecting the catchment area of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest Baptist Health. Comorbidities were common with 77 patients (56.2%) having one or more comorbidities at time of diagnosis as assessed using the Charlson co-morbidity index [10].

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Age Group

| All N = 137 | Young (< 40) N = 32 | Old (40–59) N = 52 | Elderly (60 +) N = 53 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(sd) | 52.9 (16.3) | 29.1 (6.4) | 51.4 (5.3) | 68.8 (5.9) |

| Weight (kg), mean(sd) | 89.0 (23.8) | 83.9 (22.5) | 94.9 (28.7) | 86.3 (17.8) |

| Height (cm), mean(sd) | 169.3 (11.5) | 170.2 (13.3) | 170.5 (12.2) | 167.5 (9.6) |

| BMI, mean(sd) | 31.0 (7.5) | 28.9 (6.9) | 2.5 (8.7) | 30.8 (6.2) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 123 (89.8%) | 28 (87.5%) | 48 (92.3%) | 47 (88.7%) |

| Black | 12 (8.8%) | 3 (9.4%) | 4 (7.7%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| Asian | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Native American Gender |

1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Female | 69 (50.4%) | 13 (40.6%) | 23 (44.2%) | 33 (62.3%) |

| Male Previous Cancer |

68 (49.6%) | 19 (59.4%) | 29 (55.8%) | 20 (37.7%) |

| No | 116 (84.7%) | 32 (100.0%) | 44 (84.6%) | 40 (75.5%) |

| Yes | 21 (15.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (15.4%) | 13 (24.5%) |

| Tobacco Use | ||||

| Current | 22 (16.4%) | 8 (25.0%) | 9 (17.6%) | 5 (9.8%) |

| Former | 44 (32.8%) | 2 (6.3%) | 18 (35.3%) | 24 (47.1%) |

| Never | 68 (50.7%) | 22 (68.8%) | 24 (47.1%) | 22 (43.1%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Alcohol Abuse | ||||

| Current | 4 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.1%) | 1 (2.0%) |

| Former | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.1%) | 1 (2.0%) |

| Never | 125 (94.7%) | 32 (100.0%) | 44 (89.8%) | 49 (96.1%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 5 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Marrow | ||||

| No | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (3.1%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Yes | 134 (98.5%) | 31 (96.9%) | 51 (98.1%) | 52 (100.0%) |

| Unknown/Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CNS | ||||

| No | 131 (95.6%) | 31 (96.9%) | 50 (96.2%) | 50 (94.3%) |

| Yes Lymphoblast Lymphoma |

6 (4.4%) | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (5.7%) |

| No | 110 (90.9%) | 27 (84.4%) | 42 (89.4%) | 41 (97.6%) |

| Yes | 11 (9.1%) | 5 (15.6%) | 5 (10.6%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| Unknown/Missing Cytogenetic Risk |

16 | 0 | 5 | 11 |

| Favorable | 8 (5.8%) | 1 (3.1%) | 4 (7.7%) | 3 (5.7%) |

| Intermediate | 85 (62.0%) | 20 (62.5%) | 36 (69.2%) | 29 (54.7%) |

| Unfavorable | 31 (22.6%) | 9 (28.1%) | 7 (13.5%) | 15 (28.3%) |

| Unknown | 13 (9.5%) | 2 (6.3%) | 5 (9.6%) | 6 (11.3%) |

| Number of Comorbidities, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0; 2.0) | 0.0 (0.0; 0.5) | 1.0 (0.0; 2.0) | 2.0 (1.0; 2.0) |

| HCT CI score, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0; 2.0) | 0.0 (0.0; 1.0) | 1.0 (0.0; 2.5) | 1.0 (0.0; 3.0) |

| Length of hospital stay during induction (days), median (IQR) | 26.0 (22.0; 31.0) | 22.0 (20.0; 24.5) | 27.5 (23.0; 32.0) | 26.0 (22.0; 32.0) |

| Number of cycles of consolidation, median (IQR) VTE occurrence |

4.0 (1.0; 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0; 5.0) | 5.0 (2.0; 5.0) | 1.0 (0.0; 5.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| No | 105 (77.2%) | 25 (78.1%) | 39 (75.0%) | 41 (78.8%) |

| Yes | 31 (22.8%) | 7 (21.9%) | 13 (25.0%) | 11 (21.2%) |

| Upper | 27 (87.1%) | 7 (100.0%) | 12 (92.3%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Lower Achieved Complete Remission |

6 (19.4%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| No | 28 (20.4%) | 1 (3.1%) | 7 (13.5%) | 20 (37.7%) |

| Yes | 109 (79.6%) | 31 (96.9%) | 45 (86.5%) | 33 (62.3%) |

| Survival | ||||

| Death within 30 days of treatment | 18 (13.1%) | 1 (3.1%) | 3 (5.8%) | 14 (26.4%) |

| Death within 60 days of treatment | 21 (15.3%) | 1 (3.1%) | 4 (7.7%) | 16 (30.2%) |

| Observed Deaths | 101 | 20 | 36 | 45 |

Clinical characteristics according to age group

sd standard-deviation; CNS Central nervous system; IQR Interquartile range; HCT Hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity Index; VTE Venous thromboembolism

Toxicity of CALGB 10102 Regimen

Overall, 18 patients (13.1%) died on or before day 30 and an additional three patients died on or before day 60 (15.3%). Most early mortality events (11 patients; 55%) were due to septic shock with the second most common cause of early mortality being venous thromboembolism events (3 patients; 15%). The majority of these deaths occurred in patients aged ≥ 60 (16; 75%). Older patients had a statistically higher 30 day and 60 day mortality compared to younger patients (p = 0.0012 and p = 0.0005; respectively). Thirty-one patients (15.3%) experienced a venous thrombosis during treatment. From the cohort of 137 patients, two patients (1.7%) experienced both upper and lower extremity venous thromboses; 27 patients (19.7%) had upper extremity venous thromboses alone with all of these events being associated with a central line, and six (4.4%) had lower extremity venous thromboses alone. Twenty-nine patients (21.2%) ultimately required ICU admission during induction with most patients requiring ICU level care for infectious complications (15 patients; 51.7%) with the second most common reason being bleeding or clotting complications (5 patients; 17.2%).

Efficacy CALGB 10102 Regimen

Overall, 109 patients achieved complete remission (79.6%) and 105 of those patients (96.3%) received post-remission therapy. Seven patients completed one cycle of post-remission therapy, 14 patients completed two cycles, 10 completed three cycles, 9 completed four cycles, and 64 completed all five cycles. Patients who completed ≤ 2 cycles of consolidation had a statistically significant inferior survival compared to patients who had ≥ 3 cycles of consolidation at 3.3 vs 32.9 months (p = < 0.0001). Of the 39 patients who did not complete all five cycles of post remission therapy, many patients were transitioned to maintenance due to complications from prior consolidation cycles (14 patients; 35.9%). Allogeneic stem cell transplant was the second most common reason for not completing the full five cycles of consolidation (11 patients; 28.2%) and ten patients (25.6%) experienced disease related mortality and four (10.2%) relapsed. Fifty-three (86.9%) of the 61 patients who completed all cycles went on to receive maintenance therapy. Patient’s ages ≥ 60 completed significantly fewer cycles of post-remission therapy compared to patients ages < 40 and patients ages 40–59 (p = < 0.0001). On average, patients completed a total of 15.4 months of maintenance chemotherapy with 100% of patients completing more than 3 months of maintenance requiring dose adjustments secondary to either toxicities or cytopenias. There were 33 (75%) patients that stopped maintenance prematurely due to either progression or toxicity.

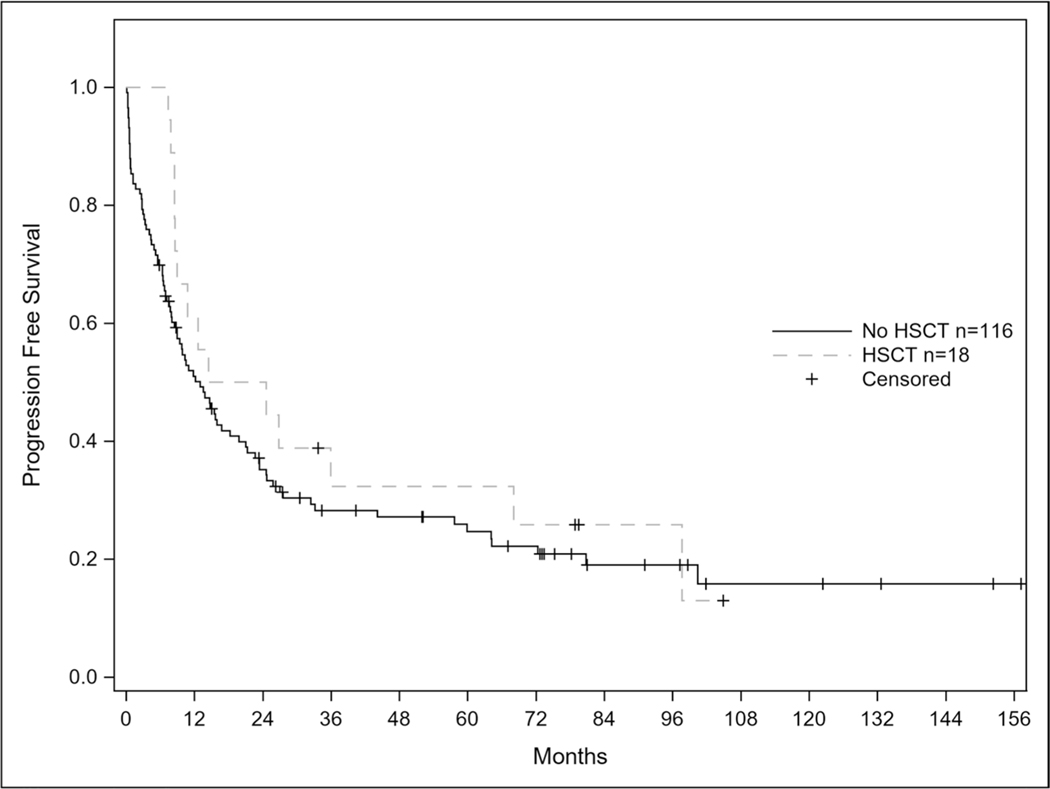

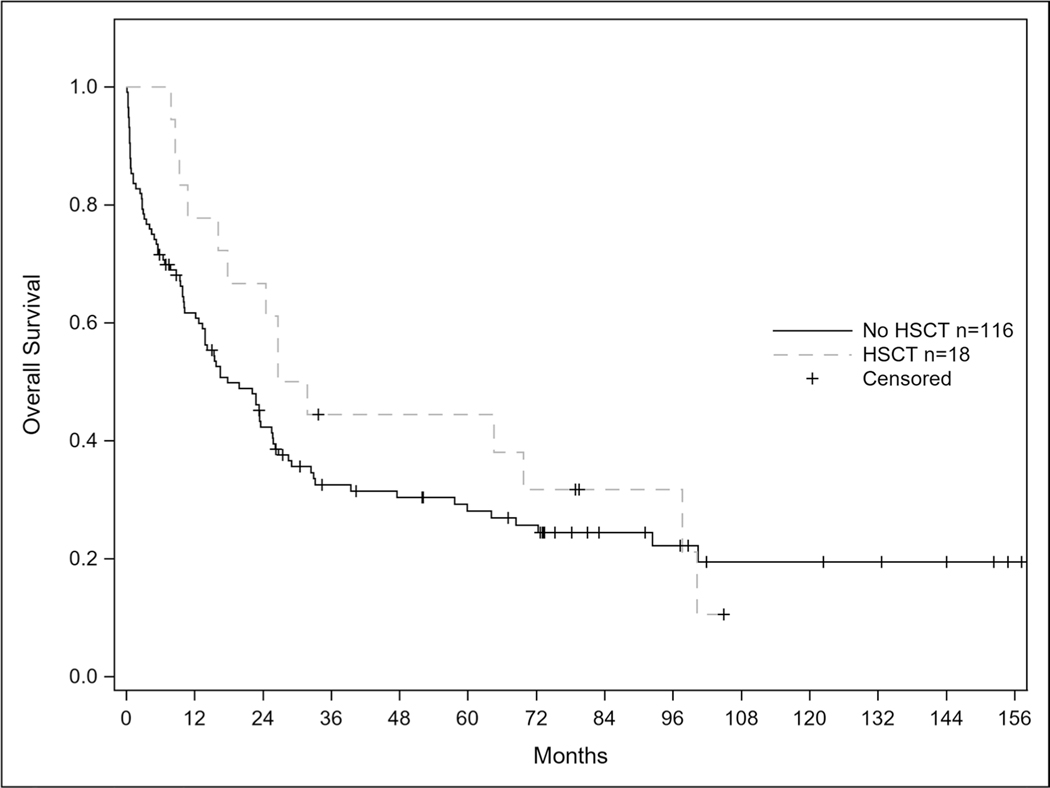

Of the 109 patients who achieved remission, 50 patients (45.9%) relapsed. Seven of the 50 relapses (21.2%) involved the CNS and 4 of the patients with CNS involvement had isolated relapse in the CNS Out of the 10 patients who had measurable residual disease (MRD) testing by multi-parameter flow cytometry at the end of their induction cycle with this regimen, 9 patients achieved a MRD negative state. Median OS from time of relapse was 6.2 months. Median survival for the entire cohort was 22.1 months (95% CI: 13.9–25.8) and median progression free survival was 13.5 months (95% CI: 8.9–19.0). Twenty-three of the patients (46%) that relapsed achieved a second complete remission with salvage therapy and the median OS from time of initial relapse was 6.2 months. In total, 18 patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Median progression free survival for patients receiving HSCT was 19.55 months vs 13.01 months for patients not receiving transplant; p = 0.37. There was no statistical difference in overall survival for patients receiving HSCT vs no HSCT (29.21 vs 17.77 months; p = 0.35) shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Progression Free Survival in Patients Receiving Transplant after CALGB 10102.

Progression free survival curves according to transplant status (p-value 0.37)

Fig. 2.

Overall Survival in Patients Receiving Transplant after CALGB 10102. Caption: Overall survival curves according to transplant status (p-value 0.35)

Effects of age, comorbidities, and cytogenetic risk scores

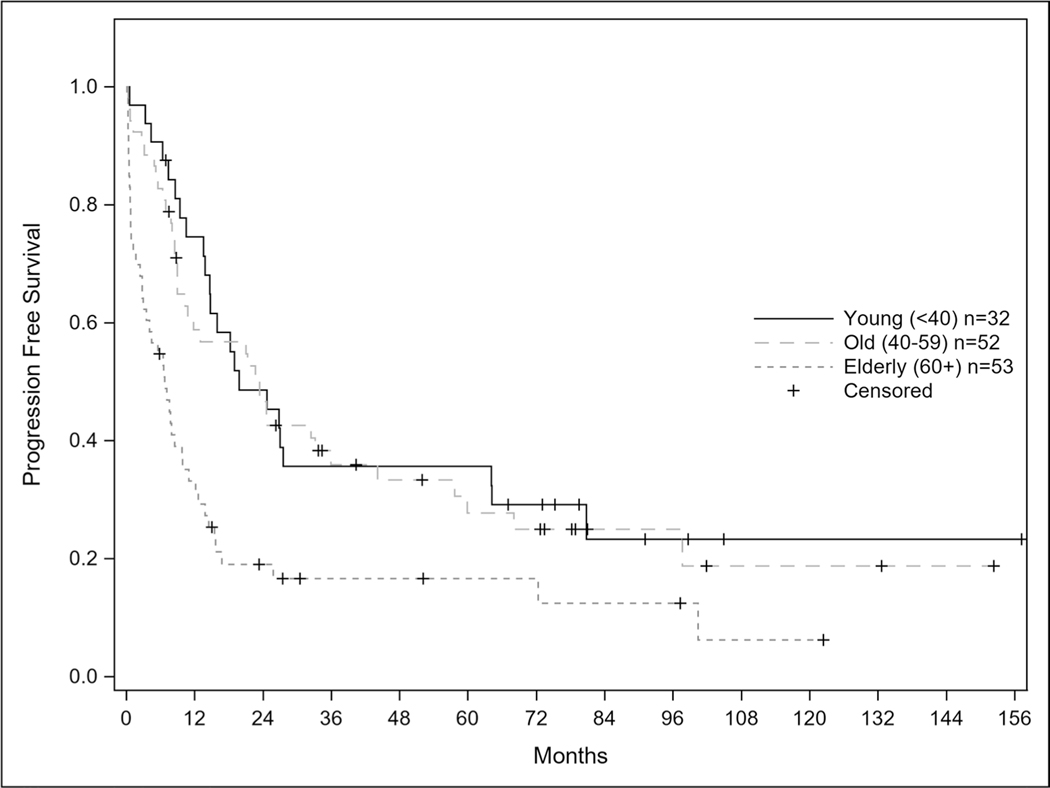

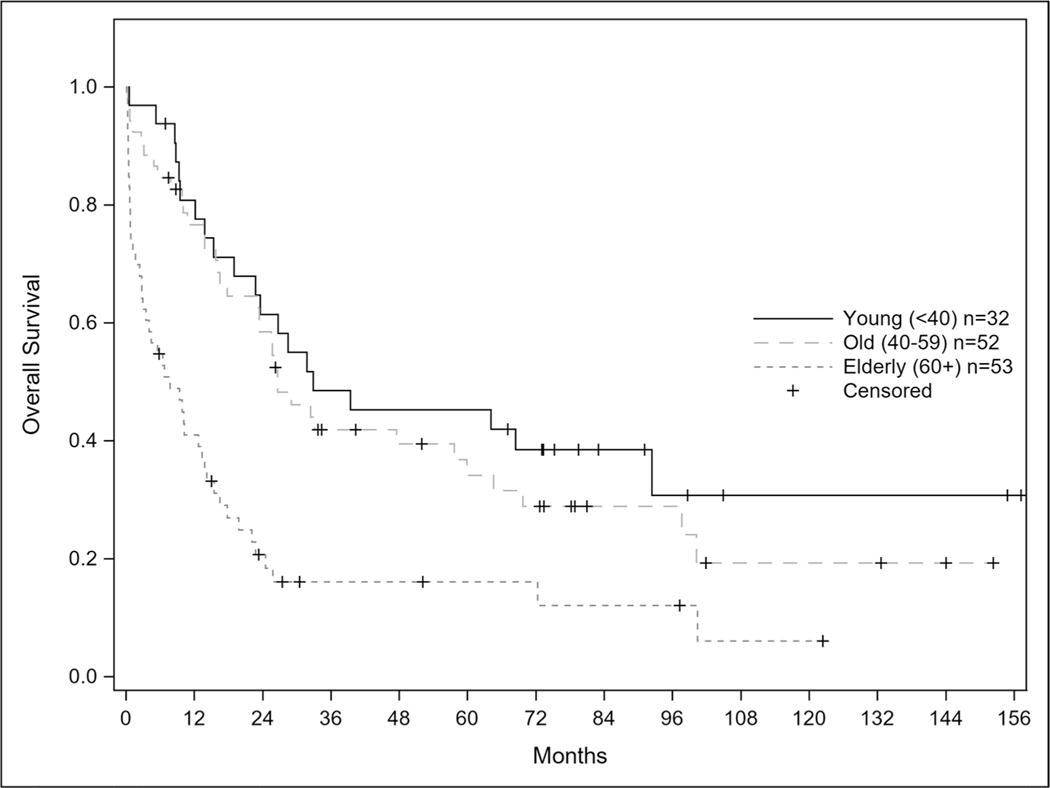

Progression free survival for the entire cohort was 13.5 months and statistically longer for patients ages 40–59 at 23.4 months compared to ages < 40 and ≥ 60 cohort at 19.8 and 6.7 months respectively (Fig. 3); p = 0.0002. When stratified by age < 40, 40–59, and ≥ 60 years of age, the median overall survival was 32.9, 26.6, and 7.8 months respectively (Fig. 4) with a p-value < 0.001. For patients less than 40 years old, 31/32 (96.9%) achieved remission and 18 (58%) of those relapsed. For patients 40 to 59 years of age, 45/52 (86.5%) achieved remission and 15 (33.3%) relapsed. In patients 60 years of age and older, 33/53 (62.3%) achieved remission and 12 (36.3%) of those patients relapsed. As age increased; patients were statistically less likely to achieve a complete remission p = 0.0002.

Fig. 3.

Progression Free Survival of CALGB 10102 Patients. Caption: Progression free survival curves for entire patient population according to age (p-value 0.0002)

Fig. 4.

Overall Survival of CALGB 10102 Patients. Caption: Overall survival curves for entire patient population according to age (p-value < 0.001)

As expected, this analysis found a strong correlation between failure to achieve remission and comorbidities. There were 77 patients with comorbidities identified in the cohort, and they were statistically less likely to achieve a complete remission compared to patients without comorbidities (p = 0.0005). On a univariate analysis, the presence of stroke, DM, HTN, renal dysfunction, and previous cancer was associated with a statistically significant lower chance of achieving a complete remission (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comorbidities and Remission Analysis

| All | Achieved Complete Remission | Fisher’s Exact p-value | Achieved Complete Remission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.0844 | |||

| No | 128 (93.4%) | 24 (85.7%) | 104 (95.4%) | |

| Yes | 9 (6.6%) | 4 (14.3%) | 5 (4.6%) | |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 0.0692 | |||

| No | 125 (91.2%) | 23 (82.1%) | 102 (93.6%) | |

| Yes | 12 (8.8%) | 5 (17.9%) | 7 (6.4%) | |

| Stroke | 0.0003 | |||

| No | 132 (96.4%) | 23 (82.1%) | 109 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 5 (3.6%) | 5 (17.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Diabetes | 0.0089 | |||

| No | 109 (79.6%) | 17 (60.7%) | 92 (84.4%) | |

| Yes | 28 (20.4%) | 11 (39.3%) | 17 (15.6%) | |

| COPD | 1.0000 | |||

| No | 130 (94.9%) | 27 (96.4%) | 103 (94.5%) | |

| Yes | 7 (5.1%) | 1 (3.6%) | 6 (5.5%) | |

| Hypertension | < .0001 | |||

| No | 82 (59.9%) | 7 (25.0%) | 75 (68.8%) | |

| Yes | 55 (40.1%) | 21 (75.0%) | 34 (31.2%) | |

| Renal Dysfunction | 0.0013 | |||

| No | 131 (95.6%) | 23 (82.1%) | 108 (99.1%) | |

| Yes | 6 (4.4%) | 5 (17.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Previous Cancer | 0.0400 | |||

| No | 116 (84.7%) | 20 (71.4%) | 96 (88.1%) | |

| Yes | 21 (15.3%) | 8 (28.6%) | 13 (11.9%) | |

| Any Comorbidity above | 0.0005 | |||

| No | 60 (43.8%) | 4 (14.3%) | 56 (51.4%) | |

| Yes | 77 (56.2%) | 24 (85.7%) | 53 (48.6%) |

Comorbidity impact on achieving a complete remission

Thirty-one (22.6%) patients had an unfavorable cytogenetic risk score as outlined by the NCCN guidelines at diagnosis while eight (5.8%) had a favorable risk score. The remaining 85 (62.0%) patients were classified as intermediate, and 13 (9.4%) patients had incomplete cytogenetic data to be appropriately risk stratified. There was no statistically significant association between cytogenetic risk and age group (p = 0.5110). Finally, patients age ≥ 60 had a longer length of stay for induction therapy at 27 days compared to patients age ˂40 at 22 days (p = 0.0004).

Discussion

There has been continued published success with the use of pediatric inspired regimens that are now the standard of care for AYA population with ALL [3, 6, 11, 12]. Outcomes in ALL have seen little improvement in the adult (ages > 40) and elderly populations. Here we report a single institution’s experience in the treatment of ALL patients according to a modified 10102 protocol previously published [9]. These findings are also consistent with prior retrospective comparisons and meta-analyses which have shown higher remission rates, lower central nervous system relapses, and superior event free and overall survival [13].

As reported in literature and further supported in this analysis, overall survival decreases significantly with age. There is currently no standard of care for the treatment of adult ALL patients over the age of 40, and this study compares favorably with previously reported adult patient treatment regimens [14]. Furthermore, tolerability of pediatric inspired regimens with patients over the age of 55 has been found to be limited [15]. Older patients are also at a much higher risk for early death. While these outcomes are disappointing, the findings of older patients treated according to this modified CALGB 10102 protocol are comparable to outcomes reported recently [16]. Treatment with hyper-CVAD (methotrexate, cytarabine followed by 6-mercaptopurine, vincristine, methotrexate and prednisone) led to a high CR rate in patients ≥ 60 years old at 84% but also led to high early mortality of 10% and a poor 5 year overall survival of 20% [17]. Moderate intensity regimens in adult patients have also led to high initial remission rates with high early mortality and poor survival [18, 19]. This demonstrates the need for further novel therapy in older patients and efforts to explore novel approaches are actively being investigated. In Ph + ALL, regimens with steroids combined with TKIs demonstrated great tolerance and excellent outcomes and recently combination of the TKI ponatinib with the bispecific monoclonal antibody blinatumomab demonstrated an 87% complete molecular response in a promising phase II trial [20, 21]. In patients aged 30–70, Litzow reported improved overall survival data when blinatumomab was added to consolidation phase of primary induction chemotherapy for patients treated with BFM like backbone chemotherapy (NR vs 71.4 months; p < 0.003) [22]. MD Anderson is investigating the combination of a dose reduced hyper-CVAD regimen combined with inotuzumab with or without blinatumomab in patients ≥ 60 has led to an impressive CR rate of 98% with no early deaths recorded and a 3 year overall survival of 56% [23, 24]. In patients ≥ 65, blinatumomab was combined with POMP maintenance and led to a high CR rate of 66% without early mortality and a 3 year overall survival of 37% [25]. It is apparent that getting older patients in remission with standard ALL regimens is achievable, however, keeping these patients in remission is more challenging.

As a real-world analysis, our observations are an important contribution to the literature in the treatment of patients over the age of 40. Analyses of real-world experience are limited in ALL especially in the upfront treatment of adult patients [16, 26, 27]. While clinical trials are critical in evaluating the safety and effectiveness of clinical therapies, real world results are essential to understanding the effectiveness of a therapy as it is applied to the target population. Additionally, there are important limitations to clinical trials. Screening criteria tend to select for healthier and more robust participants with higher performance status. Previous studies have reported that clinical trials exclude patients on the basis of age, comorbidity, and history of cancer, thus creating a cohort of individuals that do not represent the general population. Second, the interventions of a clinical trial occur in much more controlled and artificial environments and thus do not accurately represent real world scenarios [28, 29].

There are several important limitations to this analysis. First, it is a retrospective analysis with a limited sample size. Adult ALL is an uncommon malignancy and therefore the limited number of patients in this study reduces the statistical power. Despite these limitations, we believe the data presented is a significant contribution to the evolution of the ALL regimen as it represents real world application and is therefore more applicable to clinical practice. These results support the need for novel therapies for adult and older patients diagnosed with ALL which are currently under active investigation.

Conclusions

While pediatric inspired regimens have shown improved outcomes for patients less than 40 years of age, the prognosis of adult and elderly patients with ALL remains disappointing and no consensus regimen currently exists. Based on our results, patients over the age of 60 require novel strategies to help maintain their remission and improve their outcomes. This study provides an additional data set to inform discussion about treatment regimens and expected outcomes with patients being treated for ALL.

Funding

Funding for this research was supported by the Frances P. Tutwiler Fund, the Doug Coley Foundation for Leukemia Research, The McKay Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Institute of Health (TSP is supported by NCI 1R01CA197991-01A1 and SI is supported by NCI P30CA012197). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations

Statements and declarations The authors have no financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose that are directly or indirectly related to the manuscript.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Given the retrospective nature of this analysis, the institution’s IRB appropriately waived informed consent for inclusion in this analysis.

Conflict of interest Daniel Reed declares that he has no conflict of interest. Margaux Wooster declares that she has no conflict of interest. Scott Isom declares that he has no conflict of interest. Leslie Ellis declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dianna Howard declares that she has no conflict of interest. Megan Manuel declares that she has no conflict of interest. Sarah Dralle declares that she has no conflict of interest. Susan Lyerly declares that she has no conflict of interest. Rupali Bhave declares that she has no conflict of interest. Bayard Powell declares that he has no conflict of interest. Timothy Pardee declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Swerdlow SH et al. (2016) The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 127(20):2375–2390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL et al. (2021) Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 71(1):7–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stock W et al. (2019) A pediatric regimen for older adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of CALGB 10403. Blood 133(14):1548–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advani AS, Hanna R (2020) The treatment of adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 61(1):18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H (2009) Improvement in survival in younger patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia from the 1980s to the early 21st century. Blood 113(7):1408–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geyer MB et al. (2020) Pediatric-inspired chemotherapy incorporating pegaspargase is safe and results in high rates of minimal residual disease negativity in adults up to age 60 with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 106(8):2086–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson RA et al. (1995) A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood 85(8):2025–2037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowe JM (2009) Optimal management of adults with ALL. Br J Haematol 144(4):468–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stock W et al. (2009) Alemtuzumab can be incorporated into frontline therapy of adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL): final phase I results of a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study (CALGB 10102). Blood 114(22):838–838 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlson ME et al. (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seftel MD et al. (2016) Pediatric-inspired therapy compared to allografting for Philadelphia chromosome-negative adult ALL in first complete remission. Am J Hematol 91(3):322–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen EC et al. (2016) Dexamethasone and high-dose methotrexate improve outcome for children and young adults with high-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from children’s oncology group study AALL0232. J Clin Oncol 34(20):2380–2388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel SE et al. (2018) Pediatric-inspired treatment regimens for adolescents and young adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review. JAMA Oncol 4(5):725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geyer MB et al. (2017) Overall survival among older US adults with ALL remains low despite modest improvement since 1980: SEER analysis. Blood 129(13):1878–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huguet F et al. (2018) Intensified therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: report of the randomized GRAALL-2005 clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 36(24):2514–2523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim C et al. (2019) Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and mortality in elderly patients newly diagnosed with ALL. Leuk Lymphoma 60(6):1462–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien S et al. (2008) Results of the hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone regimen in elderly patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer 113(8):2097–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goekbuget N et al. (2012) Moderate intensive chemotherapy including CNS-prophylaxis with liposomal cytarabine is feasible and effective in older patients with Ph-negative Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL): results of a prospective trial from the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult ALL (GMALL). Blood 120(21):1493–1493 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribera JM et al. (2016) Feasibility and results of subtype-oriented protocols in older adults and fit elderly patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of three prospective parallel trials from the PETHEMA group. Leuk Res 41:12–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieduwilt MJ et al. (2018) A phase II study of dasatinib and dexamethasone as primary therapy followed by transplantation for adults with newly diagnosed Ph/BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL): final results of alliance/CALGB study 10701. Blood 132:309 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jabbour E et al. (2023) Ponatinib and blinatumomab for Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a US, single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 10(1):e24–e34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litzow MR et al. (2022) Consolidation therapy with blinatumomab improves overall survival in newly diagnosed adult patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia in measurable residual disease negative remission: results from the ECOG-ACRIN E1910 randomized Phase III national cooperative clinical trials network trial. Blood 140(Supplement 2):LBA-1-LBA−1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantarjian H et al. (2018) Inotuzumab ozogamicin in combination with low-intensity chemotherapy for older patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 19(2):240–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Short NJ et al. (2020) Reduced-intensity chemotherapy with minihyper-CVD plus inotuzumab ozogamicin, with or without blinatumomab, in older adults with newly diagnosed philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results from a phase II study. Blood 136:15–17 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Advani AS et al. (2022) SWOG 1318: a phase II trial of blinatumomab followed by POMP maintenance in older patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-negative B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 40(14):1574–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rees MJ et al. (2021) The real-world tolerability and efficacy of asparaginase in adults aged 40 years and older with Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 62(10):2531–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R et al. (2020) Characteristics and trends of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a large, public safety-net hospital. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 20(6):e320–e327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deeren D et al. (2020) Management of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in routine clinical practice: Minimal residual disease testing, treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in Belgium, Greece and Switzerland. Leuk Res 91:106334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saillard C et al. (2014) Evaluation of comorbidity indexes in the outcome of elderly patients treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 55(9):2211–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]