Abstract

ScaA lipoprotein in Streptococcus gordonii is a member of the LraI family of homologous polypeptides found among streptococci, pneumococci, and enterococci. It is the product of the third gene within the scaCBA operon encoding the components of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter system. Inactivation of scaC (ATP-binding protein) or scaA (substrate-binding protein) genes resulted in both impaired growth of cells and >70% inhibition of 54Mn2+ uptake in media containing <0.5 μM Mn2+. In wild-type and scaC mutant cells, production of ScaA was induced at low concentrations of extracellular Mn2+ (<0.5 μM) and by the addition of ≥20 μM Zn2+. Sca permease-mediated uptake of 54Mn2+ was inhibited by Zn2+ but not by Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, or Cu2+. Reduced uptake of 54Mn2+ by sca mutants and by wild-type cells in the presence of Zn2+ was abrogated by the uncoupler carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone, suggesting that Mn2+ uptake under these conditions was proton motive force dependent. The frequency of DNA-mediated transformation was reduced >20-fold in sca mutants. The addition of 0.1 mM Mn2+ to the transformation medium restored only partly the transformability of mutant cells, implying an alternate role for Sca proteins in the transformation process. Cells of sca mutants were unaffected in other binding properties tested and were unaffected in sensitivity to oxidants. The results show that Sca permease is a high-affinity mechanism for the acquisition of Mn2+ and is essential for growth of streptococci under Mn2+-limiting conditions.

Streptococci, pneumococci, and enterococci are human commensals colonizing a variety of human epithelial cell surfaces and have the ability to cause both superficial and life-threatening diseases. The colonization and virulence determinants of these organisms are under close scrutiny for the development of novel vaccines and inhibitors. The adhesion of streptococcal bacteria to host epithelial cells, connective tissue matrix and serum proteins, salivary components, and other bacterial cells in the environment is mediated for the most part by cell surface proteins (26, 38). Many of these proteins are anchored to the cell wall via a specialized C-terminal amino acid sequence (33). In addition, gram-positive bacteria express surface proteins that are lipid modified at the N terminus and that are associated with the outer face of the cytoplasmic membrane (36). The best characterized of these proteins in streptococci are the binding-protein components of ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type membrane transport systems involved in the uptake of peptides (1), oligopeptides (25), and multiple sugars (32).

Several laboratories independently characterized similar surface proteins produced by different streptococcal species and implicated in bacterial cell adhesion to salivary glycoproteins (17, 31), Actinomyces naeslundii (2), and fibrin (7). Members of this protein family, designated LraI (24), have now been identified in six species of streptococci (6, 9, 37) and Enterococcus faecalis (28). In Streptococcus gordonii, which colonizes tooth and mucosal surfaces, the LraI protein is a prominent surface antigen (2) and is designated ScaA (approximate molecular mass, 35 kDa). In Streptococcus parasanguis, protein homolog FimA is a candidate vaccinogen against endocarditis (37), while in Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) the PsaA protein is a virulence determinant (6). In each instance the LraI polypeptide is encoded by the third gene of a tricistronic operon encoding the components of an ABC transporter.

The sca operon in S. gordonii PK488 and DL1 comprises three genes that are transcribed from a promoter upstream of scaC (3). The scaC gene encodes an ATP-binding protein (251 amino acid [aa] residues), scaB encodes a transmembrane component (278 aa residues) which presumably dimerizes (22), and scaA encodes a lipoprotein (310 aa residues) (27). Downstream of scaA is an open reading frame (ORF4) encoding a protein of 163 aa residues with an amino acid sequence that is 52% identical overall to that of periplasmic thiol peroxidase of Escherichia coli (8), which scavenges superoxide and peroxide ions. There is evidence from transcript analysis of a homologous locus in S. parasanguis that ORF4 (designated ORF3 in S. parasanguis) is transcribed both from its own promoter and by readthrough of fimA (scaA) (16). Upstream of scaC and divergently transcribed from an overlapping promoter is a gene (ORF6) encoding a Zn2+-dependent endopeptidase (Fig. 1).

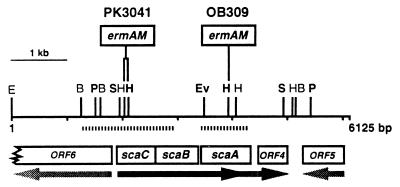

FIG. 1.

Structure of the sca locus in S. gordonii PK488 and delineation of the coding sequences and directions of transcription (arrows). Sites of insertion of ermAM to generate scaC (PK3041) and scaA (OB309) mutants of S. gordonii DL1 are indicated. Segments amplified by PCR for subsequent insertional inactivation are shown as striped bars. Base pair numbers are in accordance with sequence L11577 deposited in GenBank. Abbreviations of restriction enzymes: B, BglII; E, EcoRI; Ev, EcoRV; H, HindIII; P, PstI; S, SalI. Sites confirmed to be present in both PK488 and DL1 are shown in boldface type.

Recently, in S. pneumoniae another ABC transporter operon (adc) (12) with sequence similarity to psa was discovered. Evidence indicates that the Adc permease is a high-affinity transporter for Zn2+ and is necessary for DNA-mediated transformation of pneumococcus (11). Furthermore, it was shown that expression of the psa operon was associated with a Mn2+ requirement (11). We have characterized further the function of the sca operon in S. gordonii and now provide evidence that this operon encodes the components of a high-affinity Mn2+ transporter that is inhibited by Zn2+. This is the first report of a Mn2+ permease in oral streptococci that appears to be necessary both for growth of cells in environments with low concentrations of Mn2+ and for DNA-mediated transformation. Putative Mn2+-binding lipoprotein ScaA, which is inducible under Mn2+-limiting conditions, would thus provide a vital mechanism for the acquisition of Mn2+ by streptococci for growth and survival in the human host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth media.

S. gordonii DL1 (Challis) and PK488 are wild-type strains (2, 25). Strain OB309 (scaA1::ermAM) was an isogenic derivative of DL1 and is similar to strain OB470 (scaA2::tet) (23) but contains an ermAM cassette (25) replacing the tet cassette inserted into scaA. Strain PK3041 was an isogenic derivative of DL1 which contained an ermAM insertion in scaC. This strain was generated by cloning a 1,659-bp PCR amplimer obtained from genomic PK488 DNA with primers corresponding to regions between base pairs 1335 and 1362 and between base pairs 2969 and 2994 within the sca locus (GenBank accession no., L11577), replacing an internal 134-bp HindIII-HindIII fragment with ermAM (Fig. 1), and transforming the resistance determinant into S. gordonii DL1 by double crossover of the erythromycin resistance determinant into the coding region of the chromosomal gene (10, 23, 25). Candidate transformants for chromosomal gene conversion in the sca locus were confirmed by Southern blot analysis using scaA or scaC and ermAM as probes (25).

Bacterial cultures were grown without shaking at 37°C in brain heart infusion-yeast extract (BHY) medium, tryptone-yeast extract (TY)-glucose medium, or defined medium containing amino acids, vitamins, and glucose (25) with adjustments to concentrations of Mn2+ and Zn2+, etc., as described below. Growth was assessed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm and by determining the numbers of CFU on BHY agar.

Protein extraction, antisera, and immunoblotting.

Proteins were extracted from bacterial cells following treatment with mutanolysin (10) and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Antiserum was raised in rabbits to recombinant ScaA protein purified from inclusion bodies obtained from E. coli BL21 expressing the scaA gene cloned in pBluescript KS(+). Western blots of proteins were probed with antibodies to ScaA or HppA (25) at a dilution of 1:500 and were developed with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (25).

54Mn2+ uptake assay.

Mid-exponential-phase cells in TY-glucose medium were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh TY-glucose medium at a density of 2 × 109 cells/ml. Assays were initiated by the addition of 0.5 μCi (75 pmol) of 54Mn2+/ml and nonradioactive MnCl2 where appropriate. To test the effects of ZnSO4, other cations, or carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) on 54Mn2+ uptake, cells were preincubated for 5 min with these compounds before the addition of the label. To test 2-deoxyglucose (dGlc) inhibition of 54Mn2+ uptake, bacterial cells were resuspended in TY-dGlc medium and preincubated at 37°C for 10 min. Assays were performed at 37°C, and samples were removed at intervals into ice-cold 0.1 M LiCl. Cells were collected by vacuum filtration (25), and radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting at the 32P window setting (34). As noted for E. coli (34), significant and reproducible uptake of 54Mn2+ by streptococcal cells was achieved by utilizing buffered growth medium (TY-glucose).

Transformation.

Competent cells were prepared in TY-glucose medium containing 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and transformed to streptomycin resistance (Str) with DNA isolated from a streptomycin-resistant derivative of S. gordonii DL1 as described previously (25). Competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) pherotype 1 (21) was synthesized and kindly supplied by L. S. Håvarstein (Agricultural University of Norway, Ås).

RESULTS

S. gordonii exhibits a sca operon-dependent growth requirement for Mn2+.

Sequence analysis, restriction mapping, and blot hybridization all suggest that the genetic structures of the sca loci are similar in S. gordonii PK488 and DL1. Mutants of S. gordonii DL1 with the scaA or scaC genes inactivated were generated by insertion of the ermAM cassette into the respective coding sequences (Fig. 1). Production of the ScaA protein was abolished in the strain OB309 scaA mutant as determined by immunoblotting and by whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with ScaA-specific antibodies (23) (data not shown). In contrast, production of the ScaA protein by PK3041 (scaC::ermAM) cells was apparently unaffected (Fig. 2), suggesting that ermAM did not carry a strong transcriptional terminator, thus permitting readthrough of scaBA. This is consistent with the previously observed nonpolar effects of ermAM insertion into operons (1).

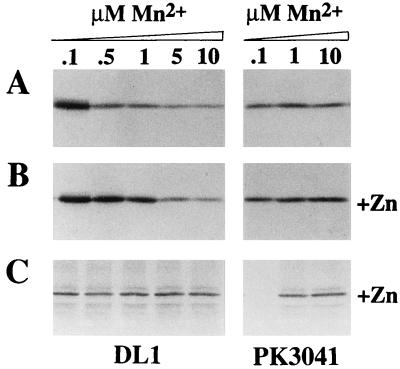

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot detection of ScaA expression in wild-type (DL1) or scaC mutant (PK3041) cells in defined media containing Mn2+ (0.1 to 10 μM) in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 20 μM Zn2+. Cultures were grown for 12 h at 37°C and the cells were harvested. Surface proteins were extracted, subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Panels A and B show reactions with ScaA antibodies, and as a control Panel C shows a reaction with antibodies to HppA oligopeptide-binding lipoprotein from S. gordonii (25). Protein loadings were equalized (50 μg per lane) except for PK3041 cells grown in 0.1 μM Mn2+ with Zn2+, where <10 μg of protein was loaded because of the 80%-reduced growth yield of cells (see text and Fig. 3).

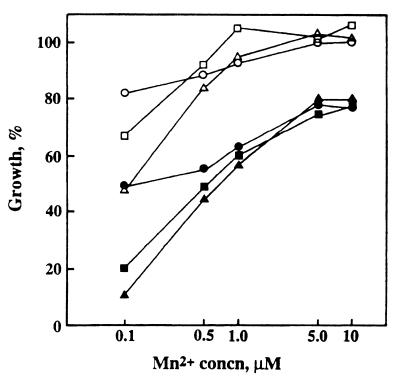

Both scaA and scaC mutants showed an increased lag phase and reduced growth rates in BHY and TY-glucose media. Growth yields of the strains in these media and in defined medium containing 0.1 μM Mn2+ were approximately 50% of that of the wild type (Fig. 3). Maximal growth of sca mutants in these media was restored by the addition of >1 μM Mn2+ (Fig. 3). Changing the concentrations of other ions such as Fe3+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ in the defined medium did not reveal any further growth differences between the wild type and mutants. The addition of ≥40 μM Zn2+ led to 40% growth inhibition of wild-type cells and to 80% inhibition of growth of sca mutants in defined medium containing 0.1 μM Mn2+ (Fig. 3). These results suggested that scaC and scaA genes were necessary for the activity of a high-affinity Mn2+ uptake system that was inhibitable by Zn2+. The addition of Zn2+ to Mn2+-replete medium was less inhibitory, with growth yields of all strains of about 80% of the wild type in the absence of Zn2+ (Fig. 3). Therefore S. gordonii contains, in addition to a Sca-dependent Mn2+ uptake system, one or more lower-affinity uptake systems that allow growth of cells under Mn2+-replete conditions.

FIG. 3.

Growth yields of wild-type and sca mutant strains after 16 h of incubation at 37°C in defined media containing different concentrations of Mn2+ (0.1 to 10 μM) in the absence (open symbols) or presence (filled symbols) of 40 μM Zn2+ (as ZnSO4 · 7H2O). Data are expressed as percentages of the growth yield of wild-type cells in 10 μM Mn2+ without added Zn2+, where 100% was equivalent to an optical density at 600 nm of 2.69 (5.4 × 109 cells/ml). Symbols: circles, DL1 (wild type); triangles, OB309 (scaA1::ermAM); squares, PK3041 (scaC::ermAM).

ScaA is induced by growth-limiting Mn2+ concentrations.

Production of ScaA protein by wild-type (DL1) cells was induced at an [Mn2+] of ≤0.5 μM (Fig. 2A). Production of ScaA was enhanced further in the presence of 20 μM Zn2+ (Fig. 2B). Levels of HppA oligopeptide-binding lipoprotein did not change under these different growth conditions (Fig. 2C). Production of ScaA protein by PK3041 cells was enhanced at all Mn2+ concentrations, although production at 0.1 μM Mn2+ was less than in the wild type (Fig. 2A). At the lowest [Mn2+] tested (0.1 μM) the growth of a PK3041 culture in 20 μM Zn2+ was reduced by 80% (Fig. 3), only small amounts of total cell protein were obtained for analysis, and HppA was not detectable on immunoblots (Fig. 2C). Under these conditions the ScaA protein was highly expressed (Fig. 2B). These data show that ScaA production in wild-type cells is under Mn2+ control and, furthermore, that ScaA production may be influenced by a Zn2+-responsive regulator.

S. gordonii expresses at least two uptake systems for Mn2+.

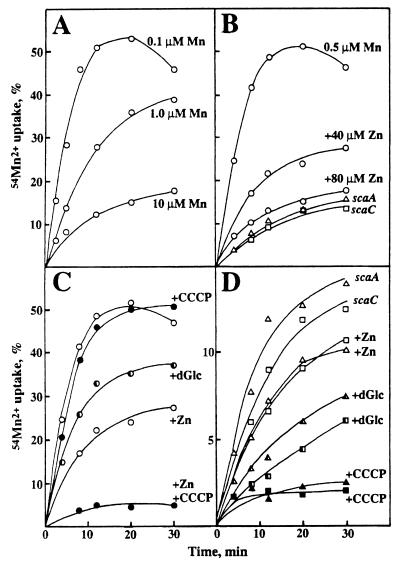

Uptake of 54Mn2+ by wild-type cells was dependent upon the extracellular [Mn2+] and was saturable as expected for active transport (Fig. 4A). The apparent Km for uptake was estimated to be 0.1 to 0.3 μM. Mutants OB309 and PK3041 both showed about 70%-reduced uptake of 54Mn2+ in 0.5 μM Mn2+ (Fig. 4B). Inhibition by Zn2+ of 54Mn2+ uptake by wild-type cells was dose dependent, and at 80 μM Zn2+, the uptake of 54Mn2+ was equivalent to that of the sca mutants (Fig. 4B). Divalent cations Mg2+, Ca2+, Hg2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ had no effect on 54Mn2+ uptake, while there was a slight enhancement with 50 μM Fe3+ (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

54Mn2+ uptake by wild-type or sca mutant cells. (A) Uptake by wild-type cells (open circles) in the presence of nonradioactive Mn2+ (as MnCl2 · 4H2O); (B) uptake in 0.5 μM Mn2+ by wild-type cells (open circles) and scaA (open triangles) and scaC (open squares) mutant cells and the effect of Zn2+ on uptake by wild-type cells; (C) uptake in the presence of 0.5 μM Mn2+ by wild-type cells (control; open circles) or in the presence of 50 mM dGlc and the effect of the addition of 100 μM CCCP (solid circles) in the absence or presence of 40 μM Zn2+; (D) effect of Zn2+, dGlc, or CCCP on uptake in 0.5 μM Mn2+ by scaA (triangles) and scaC (squares) mutants. Values are plotted as percentages of initial 54Mn2+ uptake, where 100% uptake was equivalent to 3.8 pmol of Mn2+/108 cells.

In the presence of dGlc, 54Mn2+ uptake by wild-type cells was reduced by 50%, which is consistent with a direct ATP requirement for transport (Fig. 4C). The addition of CCCP, which causes a collapse of the proton gradient, did not inhibit uptake (Fig. 4C). However, 54Mn2+ uptake in the presence of 40 μM Zn2+ was abrogated by CCCP, suggesting that a major component of the lower-affinity 54Mn2+ uptake system was proton motive force dependent. In accordance with these interpretations, the uptake of 54Mn2+ in 0.5 μM Mn2+ by scaA and scaC mutants was slightly inhibited by Zn2+, was reduced by 50% in the presence of dGlc, and was abolished by the addition of CCCP (Fig. 4D).

Transformation in S. gordonii is Sca dependent.

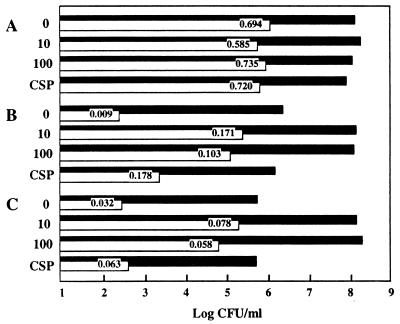

Wild-type cells of S. gordonii at the early exponential phase of growth exhibited approximately 0.7% transformability (Fig. 5). Cells of OB309 and PK3041 grew more slowly in transformation medium (which was low in Mn2+) and their transformabilities were reduced by >20-fold (Fig. 5). The addition of CSP to sca mutants growing in non-Mn2+-supplemented medium did not affect their growth rates but increased their transformabilities (Fig. 5), with scaA mutants being more responsive than scaC mutants (Fig. 5), suggesting that sca mutations affect CSP production. Growth rates of sca mutants were restored to the wild-type rate and their transformabilities were improved by the addition of 10 μM Mn2+ to the transformation medium. However, transformation frequencies of sca mutants were only 10 to 20% of wild-type levels even at 100 μM Mn2+ (Fig. 5). This indicates that Sca permease is also required for another (undefined) stage in the transformation process that is not related directly to Sca-mediated uptake of Mn2+.

FIG. 5.

Growth and transformability to Str of a wild-type strain (A) and scaA (B) and scaC (C) mutant strains in transformation medium (<0.1 μM Mn2+) without (0) or with Mn2+ (10 or 100 μM) or with CSP (400 ng/ml added 20 min prior to the addition of 50 ng of Str-transforming DNA/ml). Early-exponential-phase cells were incubated with DNA for 30 min, 10 μg of DNAse I/ml was then added, and the cultures were incubated for a further 90 min before the numbers of total CFU (filled bars) and Str CFU (open bars) were determined by viable-cell agar plate count. Values are percentages of Str transformants.

Phenotypic effects of sca mutations.

Despite the evidence for ScaA and homologous proteins in other streptococci being involved in bacterial adhesion (24), OB309 and PK3041 mutant cells were not affected in their abilities to adhere to A. naeslundii cells or to an experimental salivary glycoprotein pellicle (data not shown). An important Mn2+-requiring enzyme in streptococci is superoxide dismutase, which is essential for aerobic growth (29) and for the removal of inhibitory superoxide ions. Accordingly, growth rates of a wild-type strain and sca mutants in medium containing 0.1 μM Mn2+ were measured under anaerobiosis, with aeration, or in the presence of 5 mM paraquat, a superoxide ion generator. The anaerobic culture doubling time of the wild-type strain (50 min) was increased to 120 min under aeration and to 80 min by the addition of paraquat. Neither aeration nor the addition of paraquat had any significantly greater inhibitory effects on the growth rates of the sca mutants (data not shown), suggesting that these cells were no more sensitive to oxidants than wild-type cells.

DISCUSSION

There is currently a resurgence of interest in studying the requirement of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells for trace metals as important cofactors in many cellular processes. For example, Zn2+ is estimated to be required for the activities of more than 300 proteins, but only recently has the first bacterial ABC transporter for Zn2+ been described (11). An ABC transporter for Ni2+ in E. coli was reported and was shown to be necessary for nickel-containing hydrogenase activity (30). The requirement of Fe2+ and Fe3+ for growth of bacterial pathogens is well documented, and a variety of iron-capturing and iron uptake systems that are essential for the growth of bacteria in the iron-depleted host environment have been characterized (14). Group A streptococci exhibit a growth requirement for iron (15). The addition of Mn2+ to the growth medium was required for optimal growth of Streptococcus cricetus (13) and S. pneumoniae (11); Mn2+ was shown to be essential for the glucan-associated adhesion of some mutans group streptococcal species (5) and for pneumococcal transformation (11). We now provide evidence for a high-affinity Mn2+ transport system in S. gordonii that is necessary for the growth of cells in low-Mn2+-concentration environments and for DNA-mediated transformation. The genes encoding the Mn2+ transporter system are found in S. gordonii, S. parasanguis, and S. pneumoniae. Furthermore, since sequences highly similar to that of the scaA gene are found in S. sanguis, Streptococcus crista, and E. faecalis, it seems likely that the transporter functions in all these organisms.

In S. gordonii, production of the ScaA protein is induced by Mn2+ depletion and by the addition of Zn2+. The uptake data suggest that Zn2+ competes with Mn2+ for uptake and therefore would act to reduce the effective intracellular concentration of Mn2+. Growth of sca mutants in 0.1 μM Mn2+ was still possible but was not possible in the presence of Zn2+. This indicates the activity of a second lower-affinity transporter that also is Zn2+ sensitive. This might be equivalent to the Adc Zn2+ transporter recently characterized for S. pneumoniae, which was proposed to also be able to transport Mn2+ (11). Furthermore, the uptake inhibition data suggest that there is a third Mn2+ transporter, essentially proton motive force dependent, that mediates the uptake of and satisfies the growth requirement for Mn2+ under Mn2+-replete conditions and that is not significantly inhibited by Zn2+. The notion of a combination of specific metal ion transporters working to cover all eventualities fits well with recent data on Mn2+ transport in other systems. For example, uptake of Mn2+ by the cyanobacterium Synechocystis occurs via a high-affinity ABC transporter, which has sequence similarity to Sca, and also through a lower-affinity system (4). Similarly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains at least two Mn2+ transport systems with differing affinities for Mn2+ (35).

The expression of ScaA is up-regulated in a low concentration of Mn2+, and therefore it is likely that transcription of the sca operon is under the control of a Mn2+-responsive regulator. Transcript analyses of the sca operon (3) and of the analogous operon in S. parasanguis (16) have shown a single polycistronic mRNA, consistent with operon structure. In addition, evidence was obtained for transcriptional readthrough of downstream ORF3 (16) (ORF4 in Fig. 1), the product of which shows sequence homology to a thiol peroxidase. It is possible then that under Mn2+-limiting conditions, up-regulation of sca transcription may result not only in increased ScaA production and Sca transporter activity but also in increased production of thiol peroxidase. Since superoxide dismutase activity in streptococci is dependent upon Mn2+ (20, 29), increased production of thiol peroxidase under Mn2+-limiting conditions might provide streptococcal cells with additional protection against oxidant stress. This could account for sca mutants being no more sensitive to oxidants than the wild type. It is also possible that the ORF4 promoter may be under direct Mn2+-responsive regulation.

The fact that S. gordonii cells exhibit a growth requirement for Mn2+ could present a problem for the growth of the organism within the human host, where most available Mn2+ is complexed with albumin and transferrin (19). We suggest that the Sca transporter operates in vivo as an Mn2+-scavenging system. While ScaA is a lipoprotein and is presumably tethered to the cytoplasmic membrane, it has been shown that streptococcal lipoproteins may not remain held simply within the immediate confines of the membrane permease. Lipoproteins have been detected in extracellular culture fluid (36), and in particular there is evidence that FimA may be found distal to the membrane and associated with cell surface fimbriae (16). We suggest that the LraI proteins, by binding Mn2+ or Mn2+ complexes, may provide a means of concentrating environmentally depleted Mn2+ within the bacterial community.

Since substrates generally show a fast association with binding proteins and since there is slow dissociation of substrate, it is possible that Mn2+ may be “shuttled” in a community or may be brought membrane proximal to the permease. Furthermore, since Mn2+ is not held tightly by albumin (19) it may be sequestered directly by ScaA from albumin or shuttled first through proteins and glycoproteins on the surfaces of other bacterial cells or other host proteins. If the binding protein can bind Mn2+ that is complexed with albumin or other proteins, then this process may be revealed to have an adhesive function, which may account for the consistent evidence that the ScaA-like (or LraI family) polypeptides are adhesins (24). Since streptococci bind many serum proteins (26) and produce a number of proteases, it may be that Mn2+ is also released from protein-bound complexes as a result of bacterial proteolytic activity. Although it remains speculative as to how LraI polypeptides function in vivo it would appear that Sca and related transporters in streptococci are essential for growth of the bacteria in low-Mn2+-concentration environments. This could account for the reduced ability of S. parasanguis fim mutants to cause endocarditis (7) and for the virulence defects of pneumococcal psa mutants (6).

Growth of psaA mutants of S. pneumoniae is stimulated by Mn2+ in media containing 0.3 μM MnSO4 (11). However, in contrast to the inhibition of growth by Zn2+ observed with S. gordonii, an excess (33-fold) of Zn2+ had no inhibitory effect on the growth of psaA mutants in media containing 1.2 μM Mn2+. While both S. gordonii and S. pneumoniae appear to exhibit Mn-dependent DNA-mediated transformation, only pneumococcal transformability could be totally restored by the addition of 3 μM Mn2+. These points underpin the possibility that among streptococci common systems may play alternate roles in bacterial cell physiology and that this may be especially true for the ABC-type transporters, the activities of which may impinge on multiple cell functions.

Within a 5.2-kb putative transport-related operon (tro) of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, the first gene, troA, encodes a ScaA homolog (18). Four of the six potential gene products of the operon are homologous to proteins found in ABC systems associated with metal ion transport. Of interest is a fifth putative protein, TroR, which has a sequence similar to those of gram-positive iron-activated repressor proteins (DesR, DtxR, IdeR, and SirR). These results provide further evidence that the ScaA-like (LraI) proteins are part of a large family of substrate-binding proteins (cluster 9) (12) serving transporters associated with metal ion uptake and with Mn2+ (or Fe2+)-regulated gene expression in bacteria. This emphasizes the significance of our findings that ScaA was induced under Mn2+-depleted conditions and indicates a direct link between the transport of Mn2+, environmental sensing of trace ions, and gene regulation in streptococci.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful to J.-P. Claverys for helpful discussions and for communicating, prior to publication, data suggesting that pneumococcal Psa was a Mn2+ transporter. We thank S. Norris and J. Radolf for providing a manuscript in press, and we thank L. S. Håvarstein for providing CSP.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. P.E.K. was in receipt of a University of Otago William Evans Visiting Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloing G, dePhilip P, Claverys J-P. Three highly homologous membrane-bound lipoproteins participate in oligo-peptide transport by the Ami system of the gram-positive Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:44–48. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen R N, Ganeshkumar N, Kolenbrander P E. Cloning of the Streptococcus gordonii PK488 gene, encoding an adhesin which mediates coaggregation with Actinomyces naeslundii PK606. Infect Immun. 1993;61:981–987. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.981-987.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen R N, Lunsford R D, Kolenbrander P E. Determination of the transcript size and start site of the putative sca operon of Streptococcus gordonii ATCC 51656 (formerly strain PK488) Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:657–660. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartsevich V V, Pakrasi H B. Manganese transport in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26057–26061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer P D, Trapp C, Drake D, Taylor K G, Doyle R J. Acquisition of manganous ions by mutans group streptococci. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:819–825. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.819-825.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry A M, Paton J C. Sequence heterogeneity of PsaA, a 37-kilodalton putative adhesin essential for virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5255–5262. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5255-5262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnette-Curley D, Wells V, Viscount H, Munro C L, Fenno J C, Fives-Taylor P, Macrina F L. FimA, a major virulence factor associated with Streptococcus parasanguis endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4669–4674. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4669-4674.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha M-K, Kim H-K, Kim I-H. Mutation and mutagenesis of thiol peroxidase of Escherichia coli and a new type of thiol peroxidase family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5610–5614. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5610-5614.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correia F F, DiRienzo J M, McKay T L, Rosan B. scbA from Streptococcus crista CC5A: an atypical member of the lraI gene family. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2114–2121. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2114-2121.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demuth D R, Duan Y, Brooks W, Holmes A R, McNab R, Jenkinson H F. Tandem genes encode cell-surface polypeptides SspA and SspB which mediate adhesion of the oral bacterium Streptococcus gordonii to human and bacterial receptors. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dintilhac A, Alloing G, Granadel C, Claverys J-P. Competence and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Adc and PsaA mutants exhibit a requirement for Zn and Mn resulting from inactivation of putative ABC metal permeases. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:727–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5111879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dintilhac A, Claverys J-P. The adc locus, which affects competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae, encodes an ABC transporter with a putative lipoprotein homologous to a family of streptococcal adhesins. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:119–131. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(97)87643-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake D, Taylor K G, Doyle R J. Expression of the glucan-binding lectin of Streptococcus cricetus requires manganous ion. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2205–2207. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2205-2207.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earhart C F. Uptake and metabolism of iron and molybdenum. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1075–1090. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichenbaum Z, Green B D, Scott J R. Iron starvation causes release from the group A streptococcus of the ADP-ribosylating protein called plasmin receptor or surface glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1956–1960. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1956-1960.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenno J C, Shaikh A, Spatafora G, Fives-Taylor P. The fimA locus of Streptococcus parasanguis encodes an ATP-binding membrane transport system. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:849–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganeshkumar N, Hannam P M, Kolenbrander P E, McBride B C. Nucleotide sequence of a gene coding for a saliva-binding protein (SsaB) from Streptococcus sanguis 12 and possible role of the protein in coaggregation with actinomyces. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1093–1099. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1093-1099.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardham J M, Stamm L V, Porcella S F, Frye J G, Barnes N Y, Howell J K, Mueller S L, Radolf J D, Weinstock G M, Norris S J. Identification and transcriptional analysis of a Treponema pallidum operon encoding a putative ABC transport system, an iron-activated repressor protein homolog, and a glycolytic pathway enzyme homolog. Gene. 1997;197:47–64. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris W R, Chen Y. Electron paramagnetic resonance and difference ultraviolet studies of Mn2+ binding to serum transferrin. J Inorg Biochem. 1994;54:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(94)85119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan H M, Schrum L W. Roles of manganese and iron in the regulation of the biosynthesis of manganese-superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Håvarstein L S, Gaustad P, Nes I F, Morrison D A. Identification of the streptococcal competence-pheromone receptor. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:863–869. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.521416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins C F. ABC transporters from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes A R, McNab R, Jenkinson H F. Candida albicans binding to the oral bacterium Streptococcus gordonii involves multiple adhesin-receptor interactions. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4680–4685. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4680-4685.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkinson H F. Cell surface protein receptors in oral streptococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson H F, Baker R A, Tannock G W. A binding-lipoprotein-dependent oligopeptide transport system in Streptococcus gordonii essential for uptake of hexa- and heptapeptides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:68–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.68-77.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkinson H F, Lamont R J. Streptococcal adhesion and colonization. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:175–200. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolenbrander P E, Andersen R N, Ganeshkumar N. Nucleotide sequence of the Streptococcus gordonii PK488 coaggregation adhesin gene, scaA, and ATP-binding cassette. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4469–4480. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4469-4480.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe A M, Lambert P A, Smith A W. Cloning of an Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis antigen: homology with adhesins from some oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1995;63:703–706. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.703-706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakayama K. Nucleotide sequence of Streptococcus mutans superoxide dismutase gene and isolation of insertion mutants. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4928–4934. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4928-4934.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro C, Wu L-F, Mandrand-Berthelot M-A. The nik operon of Escherichia coli encodes a periplasmic binding-protein-dependent transport system for nickel. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1181–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oligino L, Fives-Taylor P. Overexpression and purification of a fibria-associated adhesin of Streptococcus parasanguis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1016–1022. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1016-1022.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell R R B, Aduse-Opoku J, Sutcliffe I C, Tao L, Ferretti J J. A binding protein-dependent transport system in Streptococcus mutans responsible for multiple sugar metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4631–4637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneewind O, Fowler A, Faull K F. Structure of the cell wall anchor of surface proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 1995;268:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.7701329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silver S, Johnseine P, King K. Manganese active transport in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.3.1299-1306.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Supek F, Supekova L, Nelson H, Nelson N. A yeast manganese transporter related to the macrophage protein involved in conferring resistance to mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5105–5110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutcliffe I C, Russell R R B. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1123-1128.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viscount H B, Munro C L, Burnette-Curley D, Peterson D L, Macrina F L. Immunization with FimA protects against Streptococcus parasanguis endocarditis in rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:994–1002. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.994-1002.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whittaker C J, Klier C M, Kolenbrander P E. Mechanisms of adhesion by oral bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:513–552. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]