Abstract

The field of HIV research has grown over the past 40 years, but there remains an urgent need to address challenges that cisgender women living in the United States experience in the HIV neutral status care continuum, particularly among women such as Black women, who continue to be disproportionately burdened by HIV due to multiple levels of systemic oppression. We used a social ecological framework to provide a detailed review of the risk factors that drive the women’s HIV epidemic. By presenting examples of effective approaches, best clinical practices, and identifying existing research gaps in three major categories (behavioral, biomedical, and structural), we provide an overview of the current state of research on HIV prevention among women. To illustrate a nursing viewpoint and take into account the diverse life experiences of women, we provide guidance to strengthen current HIV prevention programs. Future research should examine combined approaches for HIV prevention, and policies should be tailored to ensure that women receive effective services that are evidence-based and which they perceive as important to their lives.

Keywords: care continuum, HIV, nursing research, prevention, sexual and reproductive health, women

On a national and global level, women have been affected by HIV since the onset of the epidemic in the early 1980s and experience distinct barriers that limit their sustained access to resources for HIV prevention, care, and treatment (Higgins et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019a; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). Although HIV research that targets women has led to treatment advances, proven prevention methods may not be reaching the most vulnerable women (Brown et al., 2018; Schilt & Westbrook, 2009). Gender and racial disparities related to HIV prevention and treatment persist as contributing factors to women’s vulnerability to HIV in the United States and globally (CDC, 2020a; Newsome et al., 2015; United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014, 2018, 2019). Unfortunately, on both a domestic and a global level, women are still disproportionately affected by HIV across the lifespan, especially among adolescent girls and young women (Brown et al., 2018; United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2018, 2019). Globally, women account for more than half the people living with HIV (PLWH), and HIV-related illnesses remain the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age (United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2018).

Using a social ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; McLeroy et al., 1988), we review factors that contribute to HIV transmission among women in the United States. The objectives of this article are to describe how the different factors in each system interact to create an additive impact on women’s sexual behaviors; discuss clinical care and research on preventative interventions (including behavioral, biomedical, and structural); and examine the continuum of care (including treatment, adherence, and retention in care), advocacy, and policy that present opportunities for promising interventions and strategies to prevent HIV. We identify existing knowledge gaps and priority areas for future research among nursing scientists. Although there are various forms of gender identification, it is limiting to assume that all individuals who identify as women were assigned female at birth (Schilt & Westbrook, 2009). For the purposes of this article, the epidemiology, interventions, and policies discussed will focus on the historical and current perspective of the HIV care continuum among cisgender women, individuals who were assigned as female at birth and self-identified as women, and will be referred to as women throughout the article (Schilt & Westbrook, 2009).

Epidemiology of HIV Infection Among Women in the United States

In the United States, the proportion of women among new HIV cases rose from 8% in 1985 to 19% in 2018 (CDC, 2018), reaching its highest percentage at 27% in 2007 (CDC, 2009). Although new HIV diagnoses among women continued to decline between 2010 and 2017, dropping by 6% among women overall and by 18% among young women aged 13 to 24 years, as of 2018, women still accounted for nearly 1 in 5 new HIV diagnoses (CDC, 2019a). Among the estimated 7,000 women diagnosed with HIV in the United States, 85% of cases were attributed to heterosexual transmission, whereas the remaining 15% were attributed to injection drug use (15%; CDC, 2018). In 2018, women represented 24% (4,106) of all AIDS diagnoses, the most advanced form of HIV disease (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). New HIV infections and AIDS diagnoses among women are decreasing, probably because women are diagnosed earlier and engage in care at improved rates (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). Among all women living with HIV (WLWH) in 2018, eight in nine were aware of their HIV diagnosis, 66% received HIV medical care, 51% were retained in HIV care, and 53% had a suppressed viral load (CDC, 2020c).

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Among women, Blacks and Latinas (92% and 87%, respectively) accounted for a greater proportion of new HIV diagnoses due to heterosexual transmission compared with White women (65%); conversely, injection drug use accounted for a greater proportion of new HIV diagnoses among White women (34%; CDC, 2019b). The rate of new HIV infections among Black and Latina women was 14 and 3 times higher, respectively, as compared with White women in 2018 (Figure 1; CDC, 2020b; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). WLWH followed a similar pattern, with a greater proportion of WLWH being Black and Latina (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). Black and Latina women with a diagnosed HIV infection were also less likely to be linked to care and, if they did access care, it was often delayed (CDC, 2020c). Finally, American Indian and Alaska Native women were three times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV infection compared with White women, despite representing less than 1% of the total cases (CDC, 2020b, 2020c). These data showcase the need to support efforts to reduce HIV-related health disparities among women of color by expanding HIV linkages to care and treatment capacity at the community and organizational level.

Figure 1.

New HIV diagnoses among women by race/ethnicity in the United States and dependent areas, 2018. *Black refers to people having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. African American is a term often used for Americans of African descent with ancestry in North America. †Hispanics/Latinas can be of any race. Source: CDC. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (Preliminary). HIV Surveillance Report 2019; 30.

Disparities by Age Group

Although there has been significant progress, women of different age groups are affected very differently. In 2018, women in the age groups of 25–34 years and 35–44 years accounted for more than half (27% and 24%, respectively) of new HIV diagnoses in the United States among women, highlighting the need to promote and support the integration of HIV prevention strategies for women at reproductive age into sexual and reproductive health (SRH) practices (CDC, 2020b, 2020c). The high percentage of new infections among women at reproductive age has an influence on the rate of mother-to-child HIV transmission (CDC, 2020d; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). In the United States, perinatal infections disproportionately affected Black children (65%) due to missed opportunities for prevention, such as HIV testing and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), during the early stages of pregnancy (CDC, 2020d; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020).

Women are diagnosed with HIV at marginally older ages than men (CDC, 2020b). In 2018, men ages 13 to 34 years accounted for the majority of HIV diagnoses among men (60%), whereas women ages 13 to 34 years accounted for 40% of HIV diagnoses among women (CDC, 2020b). In 2018, new HIV diagnoses among women ages 45 to 54 years and those older than 55 years was 20 and 16%, respectively. (CDC, 2019b). According to the CDC, 35% of people ages 50 years and older already had late-stage infection (AIDS) when they received a diagnosis (CDC, 2020c). Adolescent girls and young women in the United States are also highly affected by HIV (14%), reflecting similar global trends among reproductive-age women (Brown et al., 2018).

Geographic Disparities

The impact of HIV varies across the United States, affecting women differently across states. In 2017, 10 states accounted for the majority of WLWH (67%), with New York, Florida, Texas, California, and Georgia accounting for nearly half (47%; CDC, 2019b; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). At a more local level, 25 counties represented 44% of WLWH in the United States, with the largest number (9,960) and highest incidence (1,576.5 per 100,000) of WLWH diagnoses found in Bronx County in New York City (CDC, 2019b; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020)

Contributing Factors to HIV Vulnerability Among Women

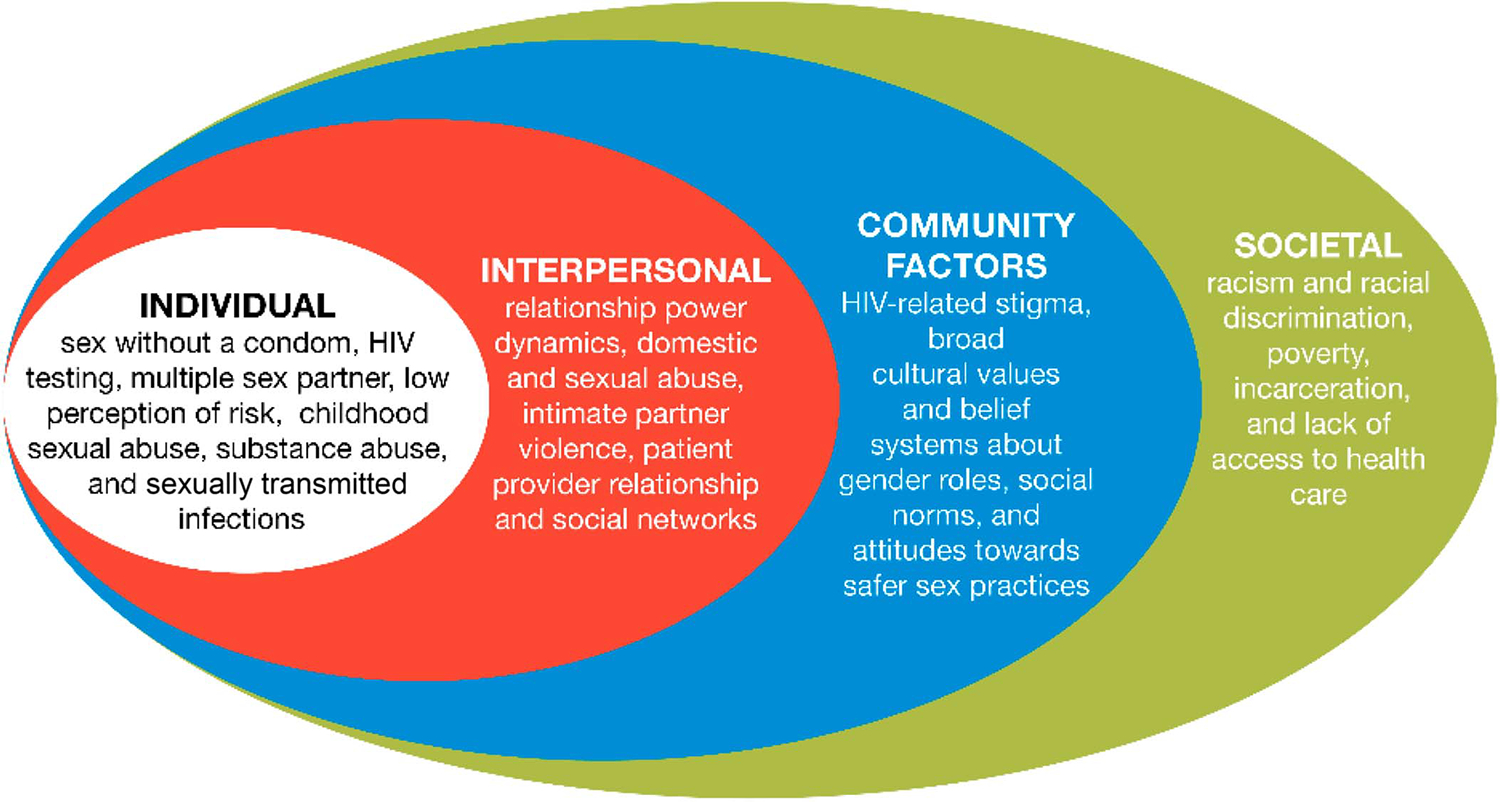

Using a social ecological framework, we will discuss the contributing factors to HIV diagnoses among women across the areas of HIV prevention, treatment, adherence, and retention. The ecological framework considers the complex interplay between individual (i.e., sex without a condom, HIV testing, multiple sex partners, low perception of risk, childhood sexual abuse, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted infections [STIs]), interpersonal (i.e., relationship power dynamics, domestic and sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, patient provider relationship, and social networks), community (i.e., HIV-related stigma, broad cultural values and belief systems about gender roles, social norms, and attitudes toward safer sex practices), and societal factors (i.e., racial discrimination, poverty, incarceration, and lack of access to health care; El-Bassel et al., 2009). Research suggests that several multilevel factors contribute to women’s vulnerability to HIV across the continuum (Chapman Lambert et al., 2017; El-Bassel et al., 2009; Flash et al., 2014; Frew et al., 2016; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Social ecological framework applied to contributing factors of HIV among women in the United States.

At the individual level, personal factors such as condomless sex, irregular or outdated HIV testing, concurrent partnering, and low risk perception increase women’s risk for HIV infection (Crosby et al., 2013; Dyson et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2018; Hall et al., 2014; McLaurin-Jones et al., 2015; Noar et al., 2012; Seth et al., 2015; Siegel et al., 2010; Teitelman et al., 2015). Research has focused on addressing these individual factors, such as interventions designed to increase condom use (Crosby et al., 2013). Interpersonal level factors that influence HIV risk transmission refer to relationship contexts, such as domestic and sexual abuse and intimate partner violence (El-Bassel et al., 2009). For example, it has been shown that women who have not been in abusive relationships are less likely than women who have been in abusive relationships to engage in high-risk behaviors, such as having sex for drugs, having sex with multiple partners, not using condoms, or not adhering to ART (Champion & Collins, 2012; Hess et al., 2012; Senn et al., 2006; Seth et al., 2015; Teitelman et al., 2015).

Community factors include broad cultural values and belief systems that influence HIV risk transmission and treatment (Corneli et al., 2016). Multiple studies suggest that community factors related to gender roles and disclosing HIV status to partners and health care providers (HCPs) influence engagement in medical care (Corneli et al., 2016; Darlington & Hutson, 2017; Earnshaw et al., 2013; Relf et al., 2019; Relf, Silva, et al., 2015).

Finally, societal level factors are those that influence one’s environment and increase the likelihood of engaging in high-risk HIV transmission behaviors. There is a growing body of literature that reports that structural level factors, such as racism and racial discrimination, and patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter pose significant health risks to individuals and communities of color, specifically Black and Latinx populations (Dale et al., 2018; Ford et al., 2009; Logie et al., 2011; Prather et al., 2018; Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). For example, several studies have shown that racial discrimination is associated with high-risk sexual behaviors among Black communities (Braksmajer et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2017; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020). There is extensive literature that supports that poor patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter has a direct impact on the quality of care and health outcomes of Blacks (Agénor et al., 2015; Beach et al., 2011; Dolezsar et al., 2014; Earl et al., 2013; Eliacin et al., 2020; Hagiwara et al., 2016; Sutton et al., 2020). Although patients in HIV care settings report greater patient–provider communication, there remain differences for Black women compared with White women (Beach et al., 2011). For example, in a study of 354 patient–provider encounters to explore the role of the patient–provider relationship in explaining racial and ethnic disparities in HIV care, providers were more controlling in conversations with Black patients as compared with White patients, and Black patients were provided with less information (Beach et al., 2011). This supports the need for improved communication between HIV providers and their Black patients.

Based on the social ecological framework, contributing factors at one level influence factors at another level, thus interventions that consider these complexities are more likely to sustain prevention intervention efforts over time, favorably modulate behaviors, and influence social norms (El-Bassel et al., 2009). Taking into account the multiple contributing factors to HIV across the continuum among women in the United States, we will examine the CDC’s evidence-based intervention (EBI) compendium and other examples of EBIs under the categories of behavioral, biomedical, and structural.

Overview of Evidence-Based HIV Risk-Reduction Interventions

Effective HIV risk-reduction interventions require a combination of behavioral, biomedical, and structural strategies (Prevention Research Synthesis [PRS], 2020; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009). The CDC maintains an active compendium of EBIs and evidence-informed interventions that have been proven effective and are identified through ongoing systematic reviews (PRS, 2020). Even with successful behavioral interventions, women continue to be affected disproportionately by HIV (Brown et al., 2018; CDC, 2020b). Most HIV-related interventions for women that have been recognized by the CDC’s Evidence-Based Interventions database are led by medicine, social work, or public health, and two include nurses as intervention facilitators. Among the 18 CDC EBIs that address HIV care across the spectrum for women (Table 1), two are led by nursing: (a) Centering Pregnancy and (b) Sisters Saving Sisters (Jemmott et al., 2005; Kershaw et al., 2009). The compendium defines EBIs as those interventions supported by well-designed randomized controlled trials that showed significant outcomes relative to a comparison group. EBIs are defined as interventions with significant HIV-related outcomes; however, they may include fewer participants or a weaker design and, therefore, need further testing (PRS, 2020). Currently, 197 EBIs are included in the compendium, with 33 being directed specifically at women (PRS, 2020). Of these, 29 are categorized as risk reduction, with the remaining four addressing structural interventions. Notably, three of the four structural interventions involve women outside of the United States, with two in Uganda and one in China (Ortblad et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Centers for Disease Control Evidence-Based and Informed Interventions

| Name of Intervention | Location | Intervention Type | Target Population | Method of Intervention Delivery | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral interventions | ||||||

| AMIGAS | USA | Risk reduction | Latina women | Education sessions by Latina health educators. Topics are culturally tailored and include videos of Latina women living with HIV, risk-reduction strategies, cultural norms and issues that may affect sexual health | Reduce HIV risk behaviors | Wingood et al. (2011) |

| Centering Pregnancy Plus | USA | Risk reduction | Young pregnant women receiving prenatal care | Sessions on self-care, childbirth prep, prenatal and postpartum care, HIV prevention skills, and sexual communication skills | Reduce STI incidence Reduce sexual risk behavior Reduce repeat pregnancy Reduce psychosocial risk factors | Ickovics et al. (2003); Kershaw et al. (2009) |

| CHAT | USA | Risk reduction | High-risk heterosexual women and their social network | Group and individual counseling sessions to discuss HIV and STI risk reduction | Davey-Rothwell et al. (2011) | |

| Connect: Couples Connect: Woman-Alone | USA | Risk reduction | Minority, inner-city heterosexual couples | Orientation and relationship-based sessions that can be delivered to couple or to woman alone; goal to enhance relationship communication, safer sex negotiation, and problemsolving skills | Increase safer sex practices among couples (i.e., increasing condom use, decreasing STD transmission, and reducing number of sex partners) Increase relationship communication | El-Bassel et al. (2001,2003) |

| Connect 2 | USA | Risk reduction | Drug-involved, uninfected, concordant, high-risk heterosexual | Sexual and drug risk reduction via weekly 2-hr sessions; can be delivered to couple together or just the partner who is drug-involved | Reduce unprotected sex Reduce STI incidence Reduce dyadic drug risk behaviors | El-Bassel et al. (2011) |

| Couples HIV Intervention Program (CHIP) | USA | Risk reduction | Transgender women and their primary cisgender male partner | Three counseling sessions on sexual transmission, condom use, HIV testing, HIV risk in relationships, stigma on gender identity (for trans women) and sexuality (for cis male partners); final session included role-playing communication skills | Reduce HIV risk behavior Improve relationship communication Improve partner interpersonal dynamics | Operario et al. (2017) |

| Eban | USA | Risk reduction | African American HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couple | Eight weekly sessions on interpersonal factors associated with sexual risk reduction (condom usage, problem solving, communication, monogamy) | Increase overall condom use Increase consistent condom use Reduce unprotected sex Reduce STD incidence |

El-Bassel et al. (2010) |

| Female Condom Skills Training | USA | Risk reduction | Uninfected, heterosexual women attending family planning | Increase knowledge about safe sex, condom use, and ability to negotiate condom use, as well as barriers and facilitators for female condom usage | Increase use of female condoms Increase protected sex |

Choi et al. (2008) |

| Healthy Love | USA | Risk reduction | Black women | Single session for preexisting group of black women; delivers HIV prevention info and teaches condom skills in interactive manner; eroticizes safer sex and creates a safe space where women can connect with sexuality in ways that are positive and self-loving | Diallo et al. (2010) | |

| Motivational Interviewing-Based HIV Risk Reduction | USA | Risk reduction | Recently incarcerated, HIVnegative women at risk for HIV | One-on-one intervention sessions in motivation enhancement; four components: recent substance use, self-assessed risk for HIV and other STIs, assessment of readiness to address her risk, stage-based discussions on behavior change; can also identify life concerns | Weir et al. (2009) | |

| Project LifeSkills | USA | Risk reduction | Young transgender women | HIV risk and transmission information, sexual partner communication, and negotiation; info on trans pride and skill building, as well as access to other services | Reduce sexual risk | Garofalo et al. (2018) |

| Safer Sex Skills Building (SSSB) | USA | Risk reduction | Heterosexually active women in drug treatment | HIV risk awareness, condom use, partner negotiation skills; problem solving, behavioral modeling, role-play rehearsal, peer feedback, and support; emphasis on women’s safer sex negotiation skills and safeguard against the risk of partner abuse | Increase condom use Decrease unsafe sexual behaviors Increase safer sex negotiation skills Increase HIV/STD risk awareness | Tross et al. (2008) |

| Sisters Saving Sisters | USA | Risk reduction | Inner-city African American female clinic patients | Culturally sensitive single sessions by African American nurses demonstrating condom use, practice with an anatomical model, and roleplaying skills to negotiate condom use | Eliminate or reduce sex risk behaviors Prevent new STD infections |

Jemmott et al. (2005) |

| WiLLOW—Women Involved in Life Learning | USA | Risk reduction | Sexually active, female clinic patients living with HIV | Skills for women living with HIV to identify and maintain supportive social networks, discredits myths regarding HIV prevention, negotiating safer sex | Reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors Reduce STDs Enhance HIV-preventative psychosocial and structural factors | Wingood et al. (2004) |

| Women on the Road to Health (WORTH) | USA | Risk reduction | Drug-involved, high-risk female offenders under community supervision | Group sessions for drug-involved women on HIV knowledge, risk reduction, and problem solving, as well as negotiation, access to services, and partner abuse risk assessment | Increase proportion of condom protected sex Increase consistent condom use Reduce unprotected vaginal and anal sex Reduce HIV and STD incidence | El-Bassel et al. (2014) |

| Biomedical interventions | ||||||

| No CDC EBIs for women | ||||||

| Structural interventions | ||||||

| County-Township-Village Allied Intervention | China | Structural intervention | Female sex workers and persons who use drugs | Local CDC provides resources to township hospitals to support training clinics. Village clinics organize HIV awareness campaigns, services for those at risk, education; FSWs as peer educators | Increase HIV testing Increase linkage to care Increase ART initiation | Yu et al. (2017) |

| Provision of Coupons for Free HIV Self-tests among Female Sex Workers in Uganda | Uganda | Structural intervention | Female sex workers | FSWs trained as peer educators to give out coupons to participants for free oral HIV self-tests; FSW educators teach participants how to perform and interpret test and help them get linked to care if positive | Increase HIV testing Increase linkage to care Increase ART initiation | Ortblad et al. (2017) |

| Direct Provision of Free HIV Self-tests among Female Sex Workers in Uganda | Uganda | Structural intervention | Female sex workers | FSWs trained as peer educators and provide onsite free oral HIV tests; continue to meet with participants individually over the following three sessions to provide condoms, educate, and screen for adverse events; last study session, free test is repeated | Increase HIV testing Increase linkage to care Increase ART initiation | Ortblad et al. (2017) |

| Provision of Coupons for Free HIV Self-tests among Female Sex Workers in Uganda | Uganda | Structural intervention | Female sex workers | FSWs trained as peer educators to give out coupons to participants for free oral HIV self-tests; FSW educators teach participants how to perform and interpret test and help them get linked to care if positive | Increase HIV testing Increase linkage to care Increase ART initiation | Ortblad et al. (2017) |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FSW = female sex worker; STD = sexually transmitted disease; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral interventions focus on eliminating or reducing HIV transmission behaviors, reducing rates of new HIV or STI transmissions, or increasing HIV-protective behaviors. Many behavioral interventions include both males and females or males alone (PRS, 2020). Women-focused interventions are far less common. We highlight individual, couple-level, and group-level interventions that target women and are included in CDC evidence-based studies (Table 1). Across individual and small group interventions, major outcomes included increased safer sex practices, such as condom usage, reduced STI and HIV occurrence, and reduced number of sexual partners. Most often, these interventions were delivered through individual or group counseling sessions, health education, and skills training (Choi et al., 2008; Davey-Rothwell et al., 2011; Diallo et al., 2010). Few interventions were solely one-to-one individual interactions developed specifically for women; however, several interventions had an individual component (Jemmott et al., 2005; Wenzel et al., 2016).

The majority of couple-level interventions for women and their male sexual partners focus on high-risk heterosexual couples. A few CDC EBIs used a couple-based approach to address risk reduction among heterosexual couples (El-Bassel et al., 2011, 2019; Operario et al., 2017). These couple-level interventions focused on relationship communication, negotiation, problem-solving skills, and goal setting. The majority of couple-based interventions for women focused on high-risk women, drug-using women, and their male partners (El-Bassel et al., 2011; McMahon et al., 2013, 2015).

Biomedical Interventions

Many HIV prevention strategies have been biomedical interventions that target both men and women, such as ART for prevention (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009), or those that target women only, such as vaginal microbicides (Abdool Karim et al., 2010). Both treatments as prevention (ART taken by PLWH to reduce HIV transmission) and pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP; ART taken by HIV-negative individuals to prevent HIV acquisition) demonstrate effectiveness in preventing HIV acquisition or transmission (Baeten et al., 2012; Cohen et al., 2011). Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of ART for PLWH for improving health outcomes and reducing HIV transmission (Abdool Karim et al., 2010; Baeten et al., 2012; Cohen et al., 2011); however, many persons remain unaware of ART for HIV prevention. This lack of awareness is especially relevant for women because they are more susceptible to vaginal–penile transmission of HIV than men (Krakower et al., 2015).

There are limited data regarding the awareness of and utilization of PEP for sexual exposure among women outside the emergency department (Donnell et al., 2010; Draughon & Sheridan, 2012), but more attention is being given to PEP usage since the introduction of PrEP (Krakower et al., 2015). PrEP represented an historic breakthrough in HIV prevention for women because it can be used without dependency on their male sex partners (Bond & Gunn, 2016). When taken daily, it is more than 90% effective in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV to women (Donnell et al., 2014). In 2014, both the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued clinical practice guidelines for women’s PrEP eligibility (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014; CDC, 2014). Despite the benefits of PrEP in preventing sexual transmission of HIV, less than 4% of the eligible women in the United States had used it by the end of 2016 (Mera-Giler et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2015). Moreover, although Black and Latina women accounted for 60% and 17%, respectively, of new adult female HIV diagnoses in 2016, they accounted for only 20% and 10% of female PrEP users (Bush et al., 2016). The extent to which these findings generalize to U.S. women at risk of HIV is unknown. Also unknown are women’s rates of retention and adherence to PrEP (Sheth et al., 2016).

There is an urgency for more women-focused interventions aimed at increasing their uptake and adherence to PrEP (Blackstock et al., 2017; Bond & Gunn, 2016; Bond & Ramos, 2019). Currently, there are few studies published on the PrEP care continuum for women (Dale, 2020) and no CDC EBI focused on PrEP uptake among women.

Structural Interventions

Central to the success of HIV interventions among women is recognition of the systematic factors that contribute to the elevated risk of infection, particularly among women of color. Studies over the past 20 years have shown that structural racism and oppression influence the SRH of Black women (Ford et al., 2009; Newsome et al., 2015; Prather et al., 2018; Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Three structural interventions in the CDC compendium focused on women outside of the United States, with two in Uganda and one in China (Table 1). No structural interventions were found specific to U.S. women. Given the contributing factors that have been repeatedly documented for women in the United States, CDC EBI structural interventions are urgently needed that address societal factors such as racism, discrimination, and access to care (Prather et al., 2018; Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020).

To date, there have been few studies outside of the EBIs that have specifically measured the impact of racism or racial discrimination on the lives of women at risk of HIV infection or WLWH (Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005; Kalichman et al., 2016). Several researchers have begun to emphasize the importance of examining how racism and discrimination influence the HIV epidemic among women in terms of prevention, treatment, and retention (Adimora & Schoenbach, 2005; Dale et al., 2019; Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020; Relf et al., 2019; Turan et al., 2017). For example, a study of Black WLWH in the southeastern United States examined the cross-sectional association between racial discrimination, HIV-related discrimination, gendered racial microaggressions, and barriers to care (Dale et al., 2019). Findings of this study showed that discrimination related to race significantly predicted a higher total of barriers to care (Dale et al., 2019). In another study that explored how perceived structural racism and discrimination experienced by Black women contribute to their participation in health services, results indicated that barriers to utilization of health services were grounded in personal experiences and historical medical mistrust of the health care system (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Women perceived a lack of communication by providers in the clinical encounter, and some women believed that false medical information was given to patients who were Black (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Frameworks such as Critical Race Theory (West et al., 1995) and Black feminism (Collins, 2000) may be valuable to future researchers seeking to address gaps in HIV interventions for minority women.

Limitations of CDC Evidence-Based Intervention Compendium for Women

The CDC’s EBI Compendium includes a wide range of interventions across the spectrum of HIV care, from addressing structural factors to individual prevention and linkage to continuation of treatment (Table 1). Yet, interventions targeted at women primarily focus on risk reduction; therefore, they only address one area of the HIV spectrum and create a gap in knowledge, particularly related to the unique needs of WLWH. As technology has become widely used for health education and maintenance, interventions that use mobile applications, for example, are warranted (Noar et al., 2009). Current technology-based interventions for women across the continuum have the potential to be included in the CDC’s compendium in the future (Bond & Ramos, 2019; Chandler, Hernandez, et al., 2020; Njie-Carr et al., 2018; Relf, William, et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2020). Similarly, there is a lack of interventions across the HIV care spectrum that focus on minority women, specifically Black and Latinx women. Of the 33 women-focused interventions identified, only 8 were directly targeted toward Black women and 6 toward Hispanic/Latinx women, with none directed at Indigenous or First Nations women (Table 1). As such, there is a need for more interventions in the biomedical aspect of HIV care, particularly focused on the needs of minority women. Further, among the one PrEP CDC EBI (Liu et al., 2019) and the two evidence-informed interventions in the compendium (Desrosiers et al., 2019; Mayer et al., 2017), none had a focus on women; all focused on men who have sex with men (Liu et al., 2019).

Additionally, researchers have reported a multitude of reasons for the limited effectiveness of EBIs in real-world settings that included the fact that they are not designed for providers or consumers, required training of practitioners, and lacked adoption fidelity by practitioners and community-based organizations (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009). “Development and dissemination of EBIs is a resource-intensive process that has not progressed as quickly as has our understanding of the epidemiology of HIV” (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009, p. 3). Multilevel interventions that take into consideration contributing factors of HIV among women are critical, and nurses are in a unique position to lead such efforts.

Nursing’s Role in HIV Prevention, Advocacy, and Policy for Women

Nurses have a unique role in developing and carrying out HIV interventions. Situated at the intersection of society and medicine, nurses have a key perspective on HIV care, particularly the recognition that root causes of HIV include both social and biomedical factors (Pittman, 2019). The holistic practice of nursing is, therefore, well-aligned with the needs of HIV care, including related interventions. Indeed, only 2 of the 33 EBIs were nurse-led or nurse-involved, potentially limiting the extent for interdisciplinary approaches to HIV interventions (Jemmott et al., 2005; Kershaw et al., 2009). Furthermore, the historic lack of investment in HIV research targeting women may be a key factor in the current lack of women-centered interventions, disproportionately affecting Black women who are often at high risk due to structural factors (Durvasala, 2018; Randolph, Johnson, et al., 2020; Relf et al., 2019). Nursing is currently engaged in advocacy and policy; however, there is an opportunity to expand the presence of nursing representation on health care boards and other decision-making platforms at the local, state, national, and international levels to influence policy across the HIV care continuum.

Advocacy and Policy

Advocacy and policies arekey strategies to improve prevention and the continuum of care, including treatment, adherence, and retention aiming to enhance the lives of WLWH. A resurgence of social justice advocacy in nursing, beginning in the early 21st century and expanding over the last decade, is valuable for reshaping practice and policies surrounding the care of PLWH (Boutain, 2005; Watson, 2018). A focus on the social influencers of health and understanding that racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities play a role in care (Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 2009) have been critical for the adoption of policies and models of care that align with the goals of HIV prevention and management. For example, the Medicaid Health Home State Plan Option, authorized through the Affordable Care Act, presents a model of care including care coordination, individual and family support, and community-based referrals for the management of complex chronic diseases such as HIV. Advocacy for sustained funding to develop evidence-based treatment allowed for the introduction of PrEP in 2012 and the first clinical practice guidelines for PrEP usage in 2014. Finally, the reintroduction of social justice principles into nursing education over the past decade, specifically in the care of PLWH, may be valuable for driving forward equitable policies and practices for PLWH (Groh et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2016).

Currently, the federal proposal to invest in HIV treatment and prevention to end the HIV epidemic in the next decade has brought increased attention to HIV policy. The proposal, announced in February 2019, invests approximately $117 million to increase capacity for testing and PrEP distribution, as well as to target geographic hotspots (Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2020). As such, an opportunity exists for nursing to become increasingly engaged with HIV policy, particularly through the profession’s revamped social justice lens. Nurses have a critical understanding of the ways in which medical and social factors, such as PrEP utilization, risk reduction, stigma and health inequities, combine in caring for marginalized populations, such as PLWH (Pittman, 2019). Advocacy and policy involvement informed by this framework are key to advancing evidence-based practice and policy in the care of PLWH and those at risk for HIV.

Future Areas for Future Research/Recommendations

Addressing the challenges in HIV among women in the United States, especially women of color, will require a response beyond the traditional medical model. Contributing factors for HIV among U.S. women operate at multiple levels, including individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. Identifying determinants of risk and protective behaviors among women is significantly important to ensure interventions are appropriate and socially relevant. The need for a combination of HIV intervention strategies across the HIV care continuum, incorporating strategies that address biological, behavioral, and structural factors, is critical to affecting the epidemic among women in the United States. Research is urgently needed on identifying and selecting these combinations for greatest effect as significant gaps in HIV interventions across the continuum for women remain. Recommendations for future research should use a combination prevention approach for women. The recommendations for future research highlight studies that expand across behavioral, biomedical, and structural interventions. Exemplars are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

HIV Prevention Research Gaps for Women in the United States: Exemplars

| Area | Exemplars |

|---|---|

| Behavioral | • Engage women who are at risk for or living with HIV as community health workers in the community in interventions from conception to evaluation. • Target interventions to expand outcomes from individual-level outcomes (increase condom use) to community-level outcomes (improve HIV-related stigma). • Create interventions that mobilize assets in the community and social networks of women. Use technology-based (i.e., mobile applications) interventions that have proven efficacy through randomized control trials for women of color (Black and Latinx). |

| Biomedical | • Increase the inclusion of women of color into clinical trials for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). • Fund needed research to determine the efficacy of ART adherence to improve health outcomes in already developed evidence-based interventions. • Initiate clinical and community interventions that focus on Black women to improve the uptake of PrEP, especially in the U.S. south. • Fund research that examines the awareness of and utilization of postexposure prophylaxis for sexual exposure among women beyond the emergency department, in primary care and community settings. |

| Structural | • Design exploratory studies using models that account for racism and its effects on health, such as Critical Race Theory, Black Feminist Thought, and intersectionality. • Initiate interventions that examine how structural racism influences efforts to develop and implement viable strategies to protect women of color, specifically Black women from HIV infection and to maximize care for women living with HIV. • Initiate interventions that address implicit bias and improve patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter. • Train physicians to more effectively engage patients in nonstigmatizing dialogue and empower Black women to address specific topics with their providers to improve communication and satisfaction with HIV care services. |

Recommendations for HIV-Related Research for Women

Recommendation 1: Develop, implement, and evaluate tailored women’s interventions using technology-based platforms, such as mobile phone apps, interactive games, or socially and culturally relevant videos.

Developing technology-based interventions that focus on women is imperative, given that past research has demonstrated technology-delivered HIV prevention interventions were more effective when they focused on either men or women but not both; interventions that focus specifically on women showed large effect sizes (Blackstock et al., 2015; Noar et al., 2009). Despite the potential of technological HIV prevention interventions, the vast majority have not targeted women and are not tailored to women’s needs (Blackstock et al., 2015). Future interventions using these platforms have the potential to increase knowledge regarding underused HIV prevention methodologies among women, such as PrEP (Blackstock et al., 2015). Future studies should also assess the effects of technology-based interventions over longer time periods and evaluate user engagement.

Technology has the potential to provide a non-traditional method for health education delivery and can potentially affect the uptake of HIV prevention and treatment options through the dissemination of electronic health (eHealth) strategies that are customized for women (Bond & Ramos, 2019). In an eHealth intervention using an avatar-led video to increase knowledge of PEP and PrEP for Black women, the avatar video product was found to be informative and engaging (Bond & Ramos, 2019). In addition, participants were willing to adopt the innovation and share it more broadly within their social networks, including social media networking sites (Bond & Ramos, 2019). There is evidence to support that the use of diffusion of innovation theory into HIV prevention programs can be useful for changing risk behaviors and increasing HIV risk reduction knowledge (Bertrand, 2004). A qualitative study exploring Black women’s preferences regarding usability, acceptability, and design of a mobile HIV prevention app found that participants had a preference for an app that included HIV prevention into the topic of optimal sexual health promotion (Chandler, Hernandez, et al., 2020). These studies reflect the need to reach more diverse samples of subpopulations affected by the HIV epidemic using web-based technologies (Bond & Ramos, 2019).

Recommendation 2: Engage women throughout the research process to identify and prioritize outcomes that matter to them, from development of concept through evaluation and dissemination.

Nurse scientists should continue their work to design, implement, and evaluate interventions to improve care on the HIV continuum with a focus on hot spots. By engaging the local communities of women, nurse scientists can identify their needs and develop or implement tailored interventions to address the unique needs of communities. The use of community engagement approaches can address health disparities in ways that traditional approaches cannot (Barrett et al., 2020). For example, engaging Black women with diverse perspectives and experiences in intervention development provides opportunities for sharing real-world examples that will help to better understand contributing factors to HIV risk (Barrett et al., 2020). Community organizations and partners can collaborate with patients to provide support when developing and implementing programs and engaging communities in research (Barrett et al., 2020).

Gaining insight from women as partners in intervention development from planning to evaluation (Randolph, Johnson, et al., 2020) allows for the development of culturally and socially relevant interventions. For example, engaging social networks of women through beauty salons for improved uptake of PrEP has been found acceptable (Randolph, Johnson, et al., 2020). Future research should consider Black women’s participation as consultants, advisory council members, and members of research teams in the development of interventions to improve the potential for sustainability.

Also, the utilization of women as community health workers (CHWs) in interdisciplinary approaches is critical for promoting high-quality care for PLWH (Busza et al., 2018). CHWs are specially trained laypersons who provide basic medical services, advocate for their community’s population health needs, and bridge the gap between the medical care system and communities themselves (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2014). As CHWs hail from the communities they serve, they are often more reflective of a community’s diversity than a medical professional and can therefore help to build trust between clinicians and community members. The literature shows an increasing number of interventions using CHWs across the spectrum of HIV prevention and management that have had positive effects on psychosocial domains, such as quality of life, self-efficacy, social support, and stigma (Busza et al., 2018; Han et al., 2018). Although a few interventions exist, understanding the impact of CHW-led programs on outcomes, such as HIV testing and management, remains largely unaddressed (Ortblad et al., 2017). As care for PLWH continues to move toward a team-based approach in community settings, the role of CHWs may continue to grow in importance for HIV prevention and management.

Recommendation 3: Use the RE-AIM framework to improve the scalability and sustainability of interventions to prevent, treat, and manage vulnerability to HIV among women.

The RE-AIM framework was “developed to address the issue that the translation of scientific advances into practice, and especially into public health impact and policy, have been slow and inequitable” (Glasgow et al., 2019, p. 1). The RE-AIM dimensions include reach (R), effectiveness (E), adoption (A), implementation (I), and maintenance (M). Despite the successful history of coordinated national strategy, EBIs are still not widely integrated into clinical practices (Grimshaw et al., 2012). To move women forward in the HIV care continuum, we need to translate EBIs into policy and practice. In other words, our aim for intervention research should be implementation of these strategies in a real-world setting beyond a clinical trial environment; however, implementation in real-world settings can be challenging for women. One of the major challenges with implementation science in the United States is that most of the studies focus on men who have sex with men, in contrast to other countries where greater attention is given to women regarding implementation of interventions (Alonge et al., 2019). To achieve the 90–90–90 goal in the United States, strategies and interventions that address barriers to HIV testing, linkage to ART, and HIV care adherence among vulnerable subpopulations of women are needed (Hall et al., 2019). “Gender-focused, behavioral interventions that address multiple risk-taking behaviors can facilitate PrEP and ART initiation and retention” (Wechsberg et al., 2017, p. 2).

For implementation science to become an established field in HIV research, there needs to be better coordination between funders of research and funders of service delivery, and greater consensus on scientific research approaches and standards of evidence (Schackman, 2010). With improved funding support, better coordination, and greater scientific clarity, researchers will be able to deliver interventions grounded in implementation science (Lambdin et al., 2015; Schackman, 2010). Contextual understanding encourages the consideration of the real-life social, political, and technical environments that may influence how well an intervention or policy performs (Logan et al., 2002). For example, key populations, such as Black women, are often stigmatized and historically have been denied access to quality health services (Prather et al., 2018). Therefore, if an intervention study aims to increase women’s participation, especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups, it would likely need to move beyond the traditional clinical setting to a more innovative community-centered approach (Levison et al., 2018).

Behavioral Intervention for Women

Recommendation 4: Explore the efficacy and long-term impact of couple-based HIV interventions that focus on the value of the romantic relationship to enact couples’ decisions and behaviors that will promote the SRH of women.

Couple-based approaches are advantageous for HIV prevention because they recognize the importance of the relationship and partners in HIV acquisition and place mutual responsibility for HIV prevention on both members of the couple. Couple-based interventions also allow both members to jointly engage in intervention activities. There is a need for more couple-based research to better understand the effects and research that includes the perspectives of both members of the couple. Couple-based interventions have been found to be effective in increasing safe sexual practices, including increased condom use and HIV testing (El-Bassel et al., 2019; Jiwatram-Negrón & El-Bassel, 2014).

For women, intimate or romantic relationships are a highly important context for HIV prevention and intervention (Higgins et al., 2014). The majority of women acquire HIV from their male partners within romantic relationships. This has led to the emergence of a body of research that explores the role of partner and relationship characteristics on HIV risk. For example, considerable research has explored the role of partner age discordance on women’s HIV risk (Akullian et al., 2017; Garnett & Anderson, 1993; Ritchwood et al., 2016). There is also evidence that relationship-level factors, such as length of relationship, satisfaction, commitment, and trust, are influential in sexual decision making (Ewing & Bryan, 2015; Harvey & Bird, 2004; Norris et al., 2004). Within romantic relationships, however, there are often gender power differentials that increase women’s vulnerability to HIV (Altschuler & Rhee, 2015; Worth, 1989). For example, women who may be financially dependent on their male partners may be less likely to refuse unwanted or undesired sex and to negotiate safe sexual practices such as the use of male and/or female condoms (Altschuler & Rhee, 2015).

Biomedical Interventions for Women

Recommendation 5: Increase the number of clinical trials tailored for women with the goal of improving PrEP uptake to prevent new infections and ART adherence to sustain viral suppression.

Although there have been monumental developments surrounding PrEP use, cisgender women have been substantially overlooked as high-priority participants in clinical trials of PrEP, antiretrovirals, and HIV vaccines (Falcon et al., 2011; Curno et al., 2016), including recent clinical trials of Descovy (TDF/FTC) and long-term injectable cabotegravir/rilpivirine efficacy. Barriers to PrEP uptake among Black women have been well-documented in the literature (e.g., financial barriers, lack of awareness, low risk perception, and structural barriers); however, the exclusion of Black women within such seminal studies is a considerable barrier to PrEP uptake (Ojikutu et al., 2018). With the advent of new PrEP medications (Flash et al., 2017), there is a need for studies to assess the acceptability and efficacy of these medications among Black women, as well as testing ways to educate them and provide resources about PrEP.

Optimal ART regimens to achieve durable viral load suppression are essential for the survival of PLWH. Yet, most clinical trials have enrolled majority male samples (Lambert et al., 2018), despite ample evidence that women have unique needs requiring tailored intervention. Because clinical trials are the gold standard for determining the safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of medical and behavioral interventions, greater inclusion of women participants is needed to determine their effects on women’s health outcomes.

Recommendation 6: Increase the number of PrEP interventions that consider the social contributors to health for Black and Latina women in both clinical and community settings. Ensure that providers across settings have the appropriate knowledge and skills to engage women effectively in the clinical encounter through interventions that focus on improving patient-provider communication.

Black and Latina women are faced with dual health disparities related to HIV because they have disproportionately high rates of HIV infection and low rates of PrEP use for HIV prevention (Cohen et al., 2015; Mera-Giler et al., 2017). This imbalance will lead to greater health disparities in HIV incidence and prevalence among women if not effectively addressed (Blackstock et al., 2017; Calabrese et al., 2017). Low awareness of PrEP is believed to be a critical barrier for women’s PrEP uptake, but even with reported high willingness to use PrEP among women of color, other factors may impede PrEP linkage, acceptance, retention, and adherence, such as the newness of the drug, side effects, medical mistrust, and stigma (Bond & Gunn, 2016). Interventions that involve a larger range of HCPs (e.g., primary care and obstetrician-gynecologist) who are trained in the provision of PrEP are necessary to initiate utilization and sustain engagement in care for women (Krakower & Mayer, 2016). Consistent with historical evidence, Black and Latina women who are significantly affected by HIV are not a population of focus for EBIs for PrEP uptake. There is an urgent need for PrEP interventions designed for Black and Latina women that will focus on their experiences of stigma within community and health care settings and the expansion of PrEP training for HCPs to support those challenges.

Structural Interventions for Women

Recommendation 7: Design exploratory studies using models that account for racism and its effects on health, such as Critical Race Theory, Black Feminist Thought, and intersectionality, to understand how structural racism influences efforts to develop and implement viable strategies to protect women of color, specifically Black women, from HIV infection and to maximize care for WLWH.

Research suggests that social determinants of health (e.g., poverty, unemployment, limited education) are contributors to HIV disparities, with racism being a probable underlying determinant of all these social conditions (Bailey et al., 2017). Yet, despite racism’s distressing impact on health and the abundance of scholarship that outlines its ill effects, research addressing disparities often fails to integrate racism as a critical driver of racial health inequities. Examination of the impact of structural racism and discrimination on health decision making of marginalized groups, such as low-income Black women, is integral to elimination of health disparities and promotion of health equity. Structural racism refers to “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice; these patterns and practices in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources” (Bailey et al., 2017, p. 1455).

There is little examination of the views of women of color affected by the HIV epidemic regarding their experiences related to structural racism in the health care system. In a recent study by Randolph et al., Black women reported ways that they perceived that structural racism impeded their abilities to access health care and preventive services and to carry out certain health behaviors (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Listed among these were mistrust of HCPs and institutions, perceived bias based on race, and lack of patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Exploring further effects that racism has on Black women’s participation in health practices and programs warrants further investigation (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020). Interventions that address implicit bias among providers and improve patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter are warranted (Randolph, Golin, et al., 2020).

Recommendation 8. Provide preventive HIV services to Black women and other women of color regardless of educational attainment and socioeconomic status.

Current clinical and research efforts tend to focus highly on low-income Black women who may not have high educational attainment and who may not have access to resources (Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020; Newsome et al., 2018); however, several studies have shown that Black women of higher socioeconomic status are still vulnerable to HIV infection, and this vulnerability is even higher while in college due to environmental and cultural influences (Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020; Heath, 2016; Newsome et al., 2018). Factors such as high socioeconomic status and education offer the impression that Black women of the middle class are less vulnerable to HIV compared with Black women of a lower socioeconomic status, yet little is known about HIV vulnerability among college-age Black women (Caldwell & Mathews, 2015; Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020; Fray & Caldwell, 2017; Painter et al., 2012). This assumption may lead to missed opportunities for HIV and STI prevention and testing within health care settings, including access to PrEP (Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020). Black women of higher education levels and socioeconomic status are less likely to screen for HIV and STIs due to having a low perception of HIV risk among themselves, as well as HCPs having a low perception of women’s risk (Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020). Ultimately, limiting HIV prevention to only women from lower socioeconomic status can be of great detriment to all Black women because Black women have smaller sexual networks and there is a higher prevalence of HIV and STIs within Black communities in the United States (Chandler, Guillaume, et al., 2020; Newsome et al., 2018).

Nursing Role in the HIV Care Continuum for Women

Recommendation 9: Increase educational efforts to support nurses’ and nurse practitioners’ specialized training in HIV care as part of HIV care teams’ provision of treatment and management of care for women at risk for and living with HIV.

Eliminating the HIV epidemic calls for the collaboration of HCPs across all disciplines (e.g., nursing, medicine, public health) at different levels, from national to state to local. With a long history of working as the frontline HCP combating HIV, nurses should continue to provide quality care to women across the HIV care continuum. Guidelines for the primary care management of PLWH indeed call for multidisciplinary, team-based care because this approach has been shown to improve adherence to treatment, address social and cultural aspects of care, and identify and respond to unmet patient needs (Bares et al., 2018; Gardner et al., 2005; Mavronicolas et al., 2017; Pittenger et al., 2019; Tran et al., 2019). Increasingly, the management of PLWH is moving into primary care and other community-based settings; therefore, the nursing workforce is poised to have a larger presence over the coming years (Aberg et al., 2014; Pittman, 2019). As these settings move toward a team-based model, nurses’ leadership and involvement is critical, and the importance of this approach will become of even greater importance to ensure the delivery of highest quality care. For example, nurse practitioners are found to provide HIV care of the same quality as physicians with HIV expertise and better-quality care compared with physicians without HIV expertise (Wilson et al., 2005). Nurse practitioners can function as the leading clinicians in HIV care either as part of HIV care teams or after high-level training or experience (Wilson et al., 2005). Thus, nurse practitioners or nurses with HIV expertise could significantly contribute to maintaining access to HIV care in settings where access to physicians is limited because the greatest loss of patients in the HIV care continuum occurs between diagnosis and care engagement. Additionally, nurses can also serve as the frontline HCP to integrate clinical care and public health activities, to reduce new infections by engaging communities to increase the test rates, to reduce stigma associated with HIV, and to encourage partner notifications.

Given the complex medical and social needs of PLWH, as well as the holistic, biopsychosocial nursing approach to care, nurses are well positioned to lead multidisciplinary care teams for this population. Nurses can fill roles such as coordination of care, initiating and following up on referrals to social services, and leading interventions for prevention and treatment adherence (Jemmott et al., 2008; Treston, 2019). Yet, effectively carrying out these tasks and promoting better patient outcomes requires the involvement of a multitude of professionals including, but not limited to, pharmacists, public health workers, physicians, and social workers. Nurses and other professionals must therefore work to understand effective team-based approaches to caring for PLWH that maximize and integrate the expertise of each discipline.

Recommendation 10: Incorporate interdisciplinary, team-based approaches in clinical practices to provide care for not only women but all PLWH.

Several examples of this approach have been documented over the past 5 years, and primarily consist of integrated didactic and clinical training for medical and nursing students, as well as other disciplines, such as pharmacy and social work (Bares et al., 2018; Kiguli-Malwadde et al., 2020; Rubin et al., 2018). Among other components, these interventions have included features such as participation in interprofessional rounds, team capstone projects, and case-based learning. Although such interventions have been rated by students as valuable learning opportunities, more evidence is needed to discern the impact of multidisciplinary approaches on clinical outcomes for PLWH.

Conclusions

HIV prevention efforts have shifted from focusing on individual behaviors (substance use) to structural and social contributing factors (such as racism, gender inequalities, and lack of access to health care) that place women at risk (Newsome et al., 2015). Combination prevention approaches that expand behavioral interventions to include biomedical strategies for prevention, incorporate technology, and use research to support policy changes to combat barriers to health equity surrounding HIV may be particularly beneficial to addressing the challenges that women continue to experience (PRS, 2020; Rotheram-Borus et al., 2009). Although the literature supports that efforts to address HIV among women in the United States have been effective, given the rates of HIV among women, specifically Black women, more work is urgently needed. A critical review of EBIs and other interventions in the current literature shows that multilevel interventions are warranted; studies that integrate contributing factors into intervention development, implementation, and evaluation are desperately needed. For example, it is well known that stigma, medical mistrust, and patient–provider communication affect HIV across the continuum. Therefore, intervention studies should expand their range of outcomes to include not only increased condom use and decreased number of sexual partners but also reduced HIV-related stigma, improved medical trust between providers and women, improved patient–provider communication in the clinical encounter, and improved access to transportation and health care. Failure to address the contextual factors within interventions will very likely hinder progress in this epidemic among women in the United States.

Key Considerations.

Factors that contribute to women’s vulnerability to HIV transmission and barriers to HIV care are complex and warrant complex, multilevel approaches to address them.

To address the HIV epidemic among women in the United States, prevention and treatment strategies need to integrate behavioral, biomedical, and structural approaches.

Interventions to improve the uptake and adherence of PrEP among women of color, particularly Black women, are urgently needed to reduce new infections.

Structural interventions are needed that address systemic racism and implicit bias in the patient–provider clinical experience to improve follow-up and adherence to treatment among women in the HIV status-neutral care continuum.

Engaging women throughout the research process using intersectional approaches and incorporating technology as an intervention delivery mode are two potential ways to improve sustainability of interventions over time.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Keosha T. Bond, Department of Community Health and Social Medicine, City University of New York School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA..

Rasheeta Chandler, School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA..

Crystal Chapman-Lambert, School of Nursing, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Loretta Sweet Jemmott, Health and Health Equity, and Professor, College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Yzette Lanier, School of Nursing, New York University, New York, New York, USA..

Jiepin Cao, School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA..

Jacqueline Nikpour, School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA..

Schenita D. Randolph, School of Nursing, and Co-director, Community Engagement Core, Duke Center for Research to Advance Healthcare Equity (REACH Equity), Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA..

References

- Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, Kharsany AB, Sibeko S, Mlisana KP, Omar Z, Gengiah TN, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Morris L, & Taylor D (2010). Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science, 329(5996), 1168–1174. 10.1126/science.1193748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA, & Infectious Diseases Society of America. (2014). Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV medicine association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58(1), e1–e34. 10.1093/cid/cit665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adimora AA, & Schoenbach VJ (2005). Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191(Suppl 1), S115–S122. 10.1086/425280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agénor M, Bailey Z, Krieger N, Austin SB, & Gottlieb BR (2015). Exploring the cervical cancer screening experiences of black lesbian, bisexual, and queer women: The role of patient-provider communication. Women & Health, 55(6), 717–736. 10.1080/03630242.2015.1039182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akullian A, Bershteyn A, Klein D, Vandormael A, Bärnighausen T, & Tanser F (2017). Sexual partnership age pairings and risk of HIV acquisition in rural South Africa. AIDS, 31(12), 1755–1764. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonge O, Rodriguez DC, Brandes N, Geng E, Reveiz L, & Peters DH (2019). How is implementation research applied to advance health in low-income and middle-income countries? BMJ Global Health, 4(2), e001257. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler J, & Rhee S (2015). Relationship power, sexual decision making, and HIV risk among midlife and older women. Journal of Women & Aging, 27(4), 290–308. 10.1080/08952841.2014.954499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2014). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus. Retrieved August 26, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/05/preexposure-prophylaxis-for-the-prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus

- Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. (2009). Position statement: Health disparities. https://www.nursesinaidscare.org/files/public/PS_HealthDisparities_App_01_2009.pdf

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, Tappero JW, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Katabira E, Ronald A, Tumwesigye E, Were E, Fife KH, Kiarie J, Farquhar C, John-Stewart G, Kakia A, Odoyo J, Mucunguzi A, … Celum C (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 399–410. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, & Bassett MT (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bares SH, Swindells S, Havens JP, Fitzgerald A, Grant BK, & Nickol DR (2018). Implementation of an HIV clinic-based interprofessional education curriculum for nursing, medical and pharmacy students. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 11, 37–42. 10.1016/j.xjep.2018.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett NJ, Ingraham KL, Bethea K, Hwa-Lin P, Chirinos M, Fish LJ, Randolph S, Zhang P, Le P, Harvey D, Godbee RL, & Patierno SR (2020). Project PLACE: Enhancing community and academic partnerships to describe and address health disparities. Advances in Cancer Research, 146, 167–188. 10.1016/bs.acr.2020.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Wilson IB, Eggly S, Cooper LA, Roter D, Sankar A, & Moore R (2011). Patient–provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS and Behavior, 15(4), 805–811. 10.1007/s10461-009-9664-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JT (2004). Diffusion of innovations and HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Communication, 9(Suppl 1), 113–121. 10.1080/10810730490271575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock OJ, Patel VV, & Cunningham CO (2015). Use of technology for HIV prevention among adolescent and adult women in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 12(4), 489–499. 10.1007/s11904-015-0287-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock OJ, Patel VV, Felsen U, Park C, & Jain S (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care, 29(7), 866–869. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1286287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond KT,& Gunn AJ (2016). Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexually active black women: An exploratory study. Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, 3(1), 1–24. 10.1353/bsr.2016.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond KT, & Ramos SR (2019). Utilization of an animated electronic health video to increase knowledge of post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among African American women: Nationwide cross-sectional survey. JMIR Formative Research, 3(2), e9995. 10.2196/formative.9995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutain DM (2005). Social justice as a framework for professional nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(9), 404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braksmajer A, Simmons J, Aidala A, & McMahon JM (2018). Effects of discrimination on HIV-related symptoms in heterosexual men of color. American Journal of Mens Health, 12(6), 1855–1863. 10.1177/1557988318797790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Williams DB, Kinchen S, Saito S, Radin E, Patel H, Low A, Delgado S, Mugurungi O, Musuka G, Tippett Barr BA, Nwankwo-Igomu EA, Ruangtragool L, Hakim AJ, Kalua T, Nyirenda R, Chipungu G, Auld A, Kim E, Payne D, … Voetsch AC (2018). Status of HIV epidemic control among adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years—Seven African countries, 2015–2017. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(1), 29–32. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings K, Hawkins T, McCallister S, & Mera Giler R (2016, June 16–20). Racial characteristics of FTC/TDF for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the US. ASM microbe 2016/ICAAC 2016, Boston, MA. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from http://www.natap.org/2016/HIV/062216_02.htm [Google Scholar]

- Busza J, Dauya E, Bandason T, Simms V, Chikwari CD, Makamba M, Mchugh G, Munyati S, Chonzi P, & Ferrand RA (2018). The role of community health workers in improving HIV treatment outcomes in children: Lessons learned from the ZENITH trial in Zimbabwe. Health Policy and Planning, 33(3), 328–334. 10.1093/heapol/czx187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, & Mayer KH (2017). Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 107(12), 1883–1889. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell K, & Mathews A (2015). The role of relationship type, risk perception, and condom use in middle socioeconomic status black women’s HIV-prevention strategies. Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, 2(2), 91–120. 10.1353/bsr.2016.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). New guidelines recommend daily HIV prevention pill for those at substantial risk. Retrieved August 26, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2014/prep-guidelines.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among heterosexuals at increased risk of HIV infection—National HIV behavioral surveillance, 17 U.S. cities, 2016. (HIV Surveillance Special Report, Issue). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-number-19.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). HIV surveillance report, diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018, Retrieved August 26, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/infographics/cdc-hiv-surveillance-vol-31-infographic.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). NCHHSTP AtlasPlus. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/index.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). HIV and African Americans. Retrieved January 30, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). HIV and women. Retrieved January 13, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020c). HIV surveillance report, 2018 (updated). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020d). HIV and pregnant women, infants, and children. Retrieved January 30, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/gender/pregnantwomen/cdc-hiv-pregnant-women.pdf

- Champion JD, & Collins JL (2012). Comparison of a theory-based (AIDS Risk Reduction Model) cognitive behavioral intervention versus enhanced counseling for abused ethnic minority adolescent women on infection with sexually transmitted infection: Results of a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(2), 138–150. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler R, Guillaume D, Tesema N, Paul S, Ross H, & Hernandez ND (2020). Social and environmental influences on sexual behaviors of college black women: Within group diversity between HBCU vs. PWI experiences. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40615-020-00843-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler R, Hernandez N, Guillaume D, Grandoit S, Branch-Ellis D, & Lightfoot M (2020). A community-engaged approach to creating a mobile HIV prevention app for Black women: Focus group study to determine preferences via prototype demos. JMIR Mhealth and Uhealth, 8(7), e18437. 10.2196/18437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman Lambert CL, Azuero A, Enah CC, & McMillan SC (2017). A psychometric examination of an instrument to measure the dimensions of Champion’s Health Belief Model Scales for cervical cancer screening in women living with HIV. Applied Nursing Research, 33, 78–84. 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, & Hussey W (2008). The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1841–1848. 10.2105/ajph.2007.113050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J,… Fleming TR (2011). Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(6), 493–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Doblecki-Lewis S, Coleman M, Bacon O, Elion R, Kolber MA, Buchbinder S, & Liu AY (2015). Authors’ reply: Race and the public health impact potential of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 70(1), e33–e35. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, Agot K, Ahmed K, Taylor J, Malamatsho F, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, & Van Damme L (2016). Participants’ explanations for nonadherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 71(4), 452–461. 10.1097/qai.0000000000000880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]