Abstract

This evidence-based practice project educated staff about the practice of writing condolence cards to bereaved family members of deceased adult patients in the oncologic setting. In addition, staff were provided with the appropriate resources to incorporate this practice into their workflow. Staff were surveyed before and after completing an educational module to identify their perceived preparedness and access to resources. Staff were also surveyed six months postimplementation to identify the impact of the practice of writing condolence cards to support the grieving process on staff members and bereaved family members.

Keywords: bereavement, condolence cards, grief, end-of-life care, evidence-based practice

While providing end-of-life care, the healthcare team cares not only for the patient but also for the patient’s family members. After the death of a patient, surviving family members are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, complicated or prolonged grief, and social distress (Brekelmans et al., 2022; Efstathiou et al., 2019; Erikson & McAdam, 2020). In addition to losing their loved one, surviving family members also experience an abrupt cessation of their relationship with the healthcare team, which, in turn, can prevent closure, cause a sense of abandonment, and complicate the grieving process (Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Makarem et al., 2018).

The World Health Organization (2020) and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (2018) consider the care of bereaved family members to be an integral part of palliative care. Bereavement practices can support family members of deceased patients and healthcare providers through the grieving process (Efstathiou et al., 2019; Takaoka et al., 2020). However, many healthcare providers report feeling unprepared to write condolence cards because of a lack of training opportunities or access to educational resources (Efstathiou et al., 2019; Porter et al., 2021).

Condolence Cards

Impact on Family Members

A condolence card can decrease the risk of prolonged grief and lower the incidence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder among bereaved family members (Brekelmans et al., 2022). Receiving a condolence card can remind family members of the special bond that the patient and family had with the healthcare staff, validate the family members’ emotional responses to the death, and inform the family members that support is available if needed (Brekelmans et al., 2022; Costa-Requena et al., 2023; Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017). In addition, condolence cards can provide family members with feelings of support, gratitude, reassurance, closure, increased satisfaction with and trust in the healthcare team, and appreciation for an opportunity to reflect, describe their loved one, and say goodbye to the healthcare team (Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Kentish-Barnes, Cohen-Solal, et al., 2017). Although many studies do not assess family responses because of ethical considerations, in previous studies, family members who were interviewed reported that they appreciated the gesture of receiving a condolence card and described the card as meaningful, touching, and a heartfelt act of compassion (Boyle, 2019; Erikson et al., 2019).

However, some studies exploring the use of condolence cards have identified less favorable outcomes, such as ambivalence, skepticism, shock, a renewed sense of loss, and stress about replying to the healthcare team (Kentish-Barnes, Cohen-Solal, et al., 2017; Moss et al., 2021). Therefore, the intent in sending a condolence card should not be to reduce grief symptoms but to manifest support (Kentish-Barnes, Cohen-Solal, et al., 2017).

Impact on Healthcare Staff

Although the goal of writing a condolence card is to support bereaved family members, the act of writing a condolence card can positively affect healthcare staff, providing them with closure when grieving the loss of a patient (Takaoka et al., 2020). This practice creates a humanist culture, which allows healthcare providers the opportunity to reminisce on their time with the patient and the patient’s family (Takaoka et al., 2020). According to Kentish-Barnes, Cohen-Solal, et al. (2017), follow-up responses from families, although unexpected, can help prevent burnout by allowing healthcare staff to exchange a final farewell with the family and hear the impact of their actions.

In general, the content of a condolence card includes the following five key components: acknowledging the death and expressing sorrow for the loss; recalling specific memories of the patient; conveying appreciation for having cared for the patient; offering support, if available, and reminding the family of their strength; and ending with a special closing statement (Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Wolfson & Menkin, 2003). In the context of health care, each card is written by the staff members involved in the care of the patient and individualized to the specific patient (Erikson & McAdam, 2020). Ideally, these cards are handwritten and sent within a few weeks of the death notification (Erikson & McAdam, 2020). Erikson and McAdam (2020) caution that sending a card too soon may reach families still in a state of shock and sending a card too late may complicate grieving.

Purpose

At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, nursing staff noted inconsistencies regarding the practice of sending condolence cards. Therefore, the purpose of this project was to (a) educate nurses and staff about how to feel prepared to write condolence cards, (b) provide resources to incorporate the practice into their workflow, and (c) offer support to family members of deceased patients and staff during the grieving process.

Methods

The Scholarly Projects Review Committee in the Department of Nursing at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center reviewed the project and determined that institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required; staff members’ voluntary participation established implied consent. This evidence-based practice project was implemented during a six-month period on an inpatient unit at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Participants in this project included RNs, patient care technicians, unit assistants, social workers, and food and nutrition workers. Funding was obtained from an internal nursing grant to purchase blank condolence cards and envelopes, which were kept stocked on the unit during the project period. Three RNs, who were previously identified as unit-based supportive care champions, assisted with project implementation and served as resources for staff during the project period.

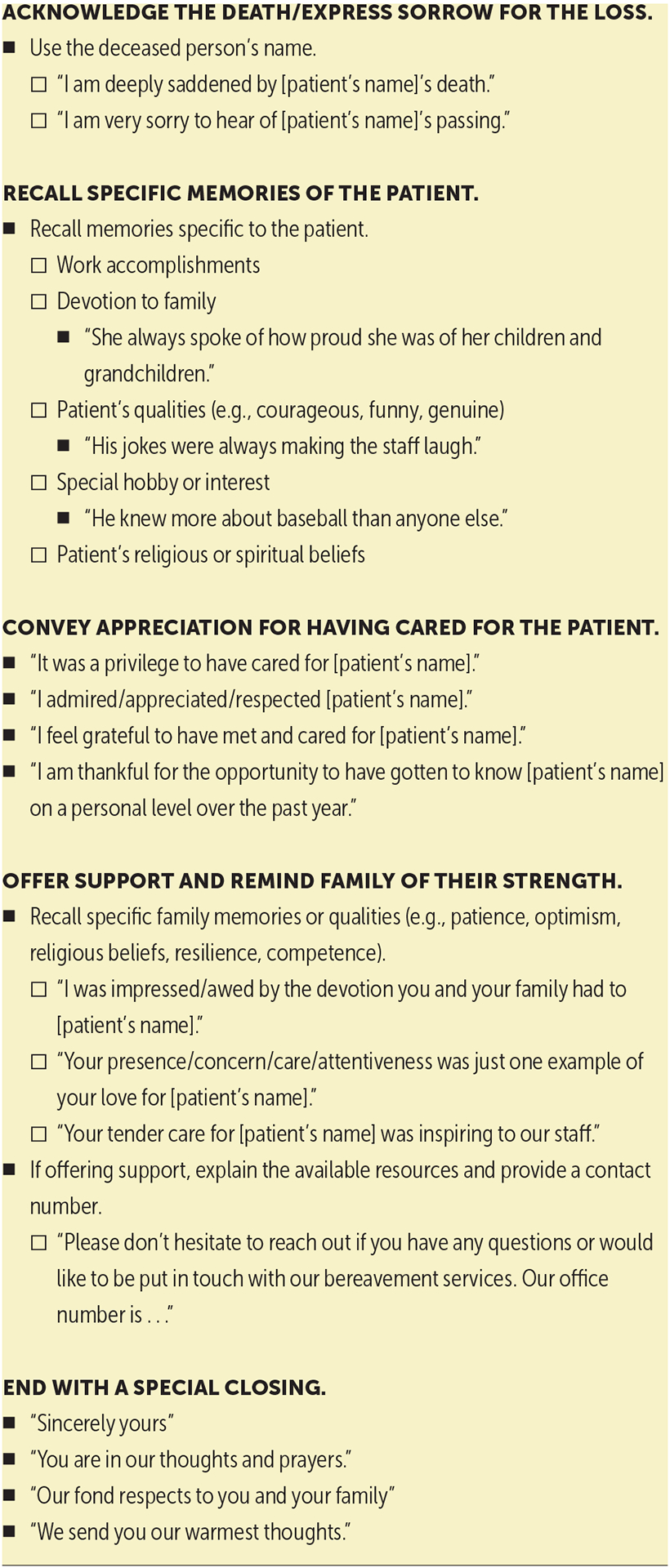

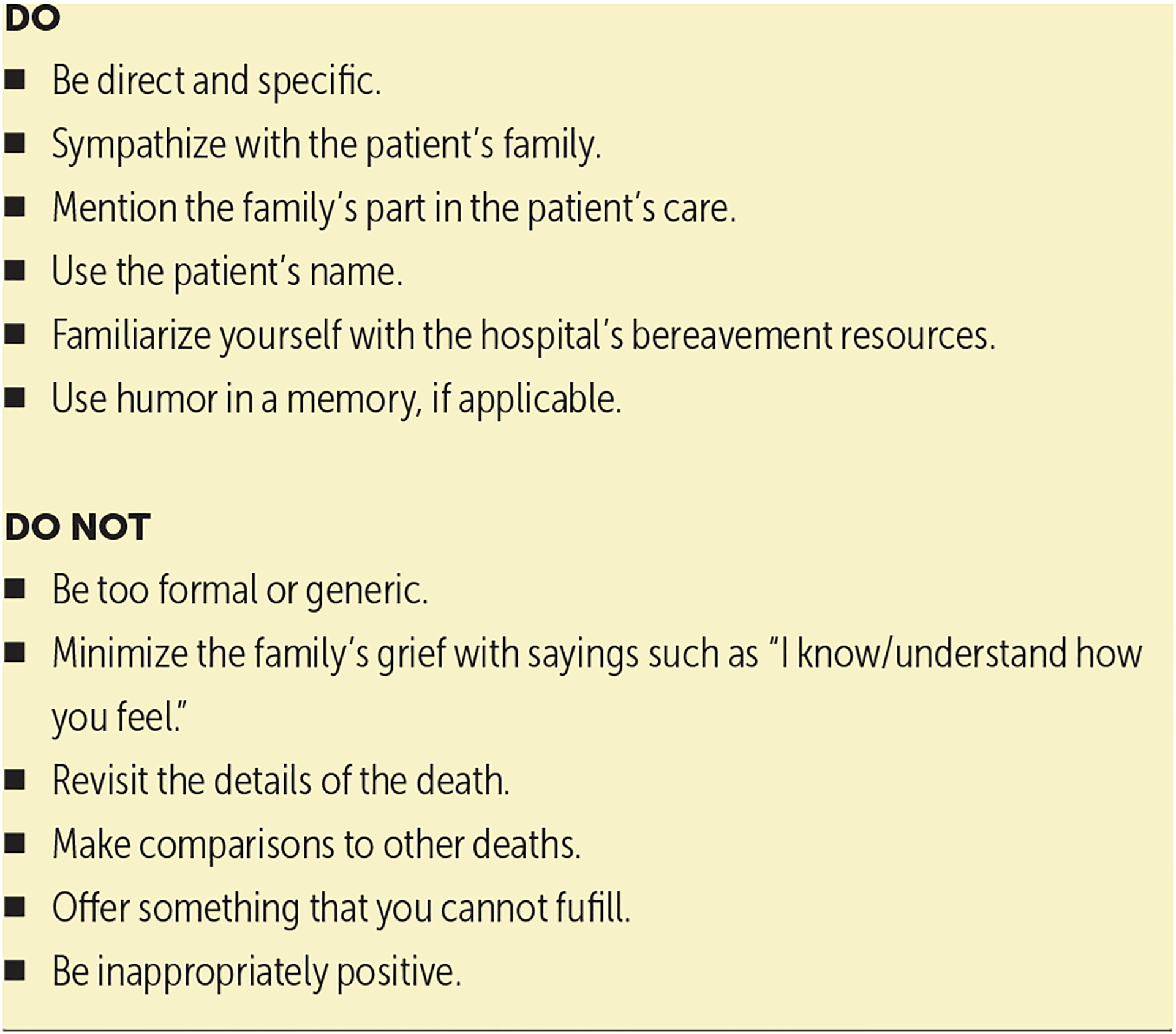

The staff preimplementation plan consisted of an 11-minute recorded educational module with audio and visual aids. The educational module’s content areas included the following: the definition of a condolence card; the clinical importance and evidence supporting the use of writing and sending condolence cards; the impact of the practice on the recipients, or bereaved family members, and the senders, or healthcare providers; the five main components of a condolence card, including specific examples and tips for writing a card (see Figure 1); tips on what to include and what to avoid when writing a condolence card (see Figure 2); and the project implementation plan. The educational module was distributed to staff via email, and staff were given opportunities to listen to and complete the educational module during their work shift.

FIGURE 1.

5 CONTENT AREAS WITH SPECIFIC EXAMPLES AND TIPS FOR WRITING CONDOLENCE CARDS

Note. Based on information from Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Wolfson & Menkin, 2003.

FIGURE 2.

THE DOs AND DO NOTs OF WRITING CONDOLENCE CARDS

Note. Based on information from Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Wolfson & Menkin, 2003.

To evaluate the project, the project team electronically distributed preimplementation, postimplementation, and six-month follow-up surveys. Surveys were distributed using REDCap electronic data capture tools. The pre- and postimplementation surveys aimed to identify and compare staff members’ interest as well as perceived preparedness and access to resources to incorporate condolence card writing into their workflow. The six-month follow-up survey aimed to identify staff members’ intended and actual use, perceived sustainability of the practice, the impact of the practice on staff members (e.g., reported sense of closure, disruption of workflow, barriers and facilitators for implementation, average length of time to complete a condolence card), and the impact of the practice on family members (i.e., whether staff received feedback from recipients and, if so, whether that feedback was positive or negative).

The implementation period was from March to September 2022. All staff were contacted via email to complete the surveys using a unique link. Reminder emails were sent prior to the closing of each survey to staff members who had not yet completed the survey. Every 14 days, the unit assistants and supportive care champions received an automated report of patients who had died in the past 14 days on the unit. Unit assistants placed one card per patient in a designated binder in the nursing station. The binder also contained a copy of the slides from the educational module. The supportive care champions started each card at the beginning of the two-week period and reviewed the cards before giving them to the unit assistants to address and mail. Staff members were welcome to contribute to the card as desired during each two-week period.

Survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were summarized by count and percentage. Continuous variables were summarized using median averages.

Results

Demographic information collected from participants included their staff role (see Table 1). Of the 42 participants who completed the preimplementation survey, 27 reported that they had no prior experience with writing or sending a condolence card. Of those participants without prior experience, 18 reported they felt that they had access to resources to write condolence cards. On a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 indicating participants felt very prepared, the median score for perceived preparedness was 6.7. Preimplementation, 21 participants expressed interest in incorporating the practice of writing condolence cards into their workflow.

TABLE 1.

PRE, POST, AND 6-MONTH SURVEY RESULTS

| VARIABLE | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Role | ||

| RN | 35 | - |

| Food and nutrition worker | 4 | - |

| Patient care technician/nursing assistant | 1 | - |

| Social worker | 1 | - |

| Unit assistant | 1 | - |

| Had prior experience writing condolence cards | ||

| No | 27 | 16 |

| Yes | 15 | 8 |

| Perceived an access to resources a | ||

| Yes | 18 | 15 |

| No | 9 | 1 |

| Reported an interest in incorporating writing condolence cards into workflow a | ||

| Yes | 21 | 14 |

| No | 6 | 2 |

| VARIABLE | ||

| Intended to continue writing condolence cards | ||

| Yes | 16 | |

| No | 2 | |

| Reported a disruption in workflow | ||

| No | 18 | |

| Yes | - | |

| Reported feeling a sense of closure | ||

| Yes | 17 | |

| No | 1 | |

| Reported sustainability to effectively continue practice beyond project period | ||

| Yes | 18 | |

| No | - | |

| Reported actual continuation of practice | ||

| Yes | 13 | |

| No | 5 | |

| Cards completed per participant (N = 13) | ||

| 1–5 | 4 | |

| 6–9 | 7 | |

| 10–15 | - | |

| 16 or more | 2 | |

| Received feedback from family (N = 13) | ||

| No | 9 | |

| Yes | 4 | |

| Time to complete card (minutes) (N = 13) | ||

| 10 or fewer | 13 | |

| 11–12 | - | |

| 21–30 | - | |

| More than 30 | - |

N values include only the number of participants who indicated that they had no prior experience writing condolence cards.

post—postimplementation; pre—preimplementation

Note. On a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater perceived preparedness, the pre median score was 6.7, and the post median score was 8.3.

Of the 24 participants who completed the postimplementation survey, 16 reported that they had no prior experience with writing or sending a condolence card. Of those participants, almost all (n = 15) reported that they had the resources to do so following the educational module. Postimplementation, the median perceived preparedness score increased to 8.3. In addition, 14 participants expressed interest in incorporating this practice into their workflow postimplementation.

In total, 18 participants completed the six-month follow-up survey. Of those participants, 17 reported that the practice provided a sense of closure for the staff member regarding the patient’s death, 16 reported that they intend to send or continue to send condolence cards, and all reported that they felt that writing condolence cards did not disrupt workflow and could effectively continue on the unit. Of the 13 participants who reported that they had sent condolence cards after the project period, four sent 1–5 cards, seven sent 6–9 cards, and two sent 16 cards or more. Participants reported that each card required 10 minutes or fewer to complete. Postimplementation, four participants reported receiving feedback from bereaved family members, with all feedback being positive.

Discussion and Implications for Nursing

Overall, the results from this project support the practice of writing and sending condolence cards to bereaved family members. The results also highlight the need for education and training about bereavement practices, particularly the act of writing condolence cards, for staff members. Staff members’ perceived preparedness scores and reported access to the necessary resources to write condolence cards increased from pre- to posteducation. Staff members received initial education prior to implementation and continuous access to educational resources and supportive care champions throughout the project. The educational module provided Staff members with recommendations for messages in general content areas and examples but strongly emphasized the impact of personalizing the cards to each specific patient, aligning with evidence-based practice (Kentish-Barnes, Chevret, et al., 2017; Takaoka et al., 2020).

Cards were sent during two-week intervals based on results from a prior study in which family members identified that within two weeks was an appropriate time frame to receive cards (Erikson et al., 2019). This project was implemented as an adjuvant intervention to the current standard of care and did not require mandatory participation from Staff. Long and Curtis (2017) noted that requiring Staff to send condolence cards regardless of level of experience in writing cards or extent of prior relationship between the patient and Staff may affect the quality and sincerity of the card.

Postimplementation, Staff members reported feeling a sense of closure from incorporating this practice into their workflow. This response was consistent with responses reported in other studies (Kentish-Barnes, Cohen-Solal, et al., 2017; Takaoka et al., 2020). Staff members reported that sending condolence cards could continue effectively on the unit without disrupting the current workflow.

The project team refrained from seeking feedback from family members who received cards because of the ethical implications of involving this potentially vulnerable population (Brekelmans et al., 2022). However, in alignment with previous studies, multiple patients’ families reached out to Staff during the project period and responded positively to the condolence card practice (Boyle, 2019; Erikson et al., 2019).

Staff reported that designating roles to the supportive care champions and unit assistants and placing the binder and resources in the nursing station facilitated implementation. Barriers to project implementation included obtaining initial buy-in from Staff and recalling specific memories of deceased patients if too much time had passed between the patient’s stay on the unit and the patient’s death.

Limitations

This project has several limitations. Because of the small sample size on a single inpatient unit at an urban cancer center, the project’s findings may not be generalizable to Staff members in other settings. In addition, no data were collected from the card

“Receiving a condolence card can remind family members of the special bond that the patient and family had with the healthcare staff.”

recipients, so assumptions cannot be made on whether all cards were perceived positively. Finally, given the increased use of technology and electronic communication in the current healthcare system, future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of sending personalized electronic cards compared to handwritten cards.

Conclusion

Based on this project’s results from an oncologic medical-surgical inpatient unit, Staff members and card recipients support the practice of sending condolence cards to bereaved family members of deceased adult patients. After receiving education about writing condolence cards, nursing and support Staff reported increased perceived preparedness and access to resources for writing cards. The majority of Staff members reported a sense of closure from incorporating this practice into their workflow, as well as an intent to continue this practice beyond the project period. Although limited, feedback from bereaved family members who received condolence cards was positive.

AT A GLANCE.

Bereavement practices, particularly condolence cards, can support not only family members of deceased patients but also healthcare providers during the grieving process.

Although bereavement practices are recognized as an essential component of end-of-life care, many healthcare staff report feeling unprepared because of a lack of education and training.

Condolence cards should be individualized for each patient and include staff members who had a relationship with the patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors take full responsibility for this content. This work was supported, in part, by a grant (P30 CA008748) from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center through funding from the National Cancer Institute.

Contributor Information

Kelly Preti, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center;.

Elizabeth Giles, Aspire Health;.

Mary Elizabeth Davis, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, all in New York, NY..

REFERENCES

- Boyle DA (2019). Nursing care at the end of life: Optimizing care of the family in the hospital setting. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23(1), 13–17. 10.1188/19.CJON.13-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekelmans ACM, Ramnarain D, & Pouwels S (2022). Bereavement support programs in the intensive care unit: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 64(3), e149–e157. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Requena G, Vivó-Benlloch C, Roig-Roig G, & Pérez Del Caz MD (2023). Condolence letter in the burn unit. HERD, 16(1), 303–304. 10.1177/19375867221127418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou N, Walker W, Metcalfe A, & Vanderspank-Wright B (2019). The state of bereavement support in adult intensive care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Journal of Critical Care, 50, 177–187. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson A, & McAdam J (2020). Bereavement care in the adult intensive care unit: Directions for practice. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 32(2), 281–294. 10.1016/j.cnc.2020.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson A, Puntillo K, & McAdam J (2019). Family members’ opinions about bereavement care after cardiac intensive care unit patients’ deaths. Nursing in Critical Care, 24(4), 209–221. 10.1111/nicc.12439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Champigneulle B, Thirion M, Souppart V, Gilbert M, … Azoulay E (2017). Effect of a condolence letter on grief symptoms among relatives of patients who died in the ICU: A randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Medicine, 43(4), 473–484. 10.1007/s00134-016-4669-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish-Barnes N, Cohen-Solal Z, Souppart V, Galon M, Champigneulle B, Thirion M, … Azoulay E (2017). “It was the only thing I could hold onto, but …”: Receiving a letter of condolence after loss of a loved one in the ICU: A qualitative study of bereaved relatives’ experience. Critical Care Medicine, 45(12), 1965–1971. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long AC, & Curtis JR (2017). Aligning intention and effect: What can we learn from family members’ responses to condolence letters? Critical Care Medicine, 45(12), 2099–2100. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarem M, Mohammed S, Swami N, Pope A, Kevork N, Krzyzanowska M, … Zimmermann C (2018). Experiences and expectations of bereavement contact among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21(8), 1137–1144. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss SJ, Wollny K, Poulin TG, Cook DJ, Stelfox HT, des Ordons AR, & Fiest KM (2021). Bereavement interventions to support informal caregivers in the intensive care unit: A systematic review. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 66. 10.1186/s12904-021-00763-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (4th ed.). National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp [Google Scholar]

- Porter AS, Weaver MS, Snaman JM, Li C, Lu Z, Baker JN, & Kaye EC (2021). “Still caring for the family”: Condolence expression training for pediatric residents. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(6), 1188–1197. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Vanstone M, Neville TH, Goksoyr S, Swinton M, Clarke FJ, … Cook DJ (2020). Family and clinician experiences of sympathy cards in the 3 Wishes project. American Journal of Critical Care, 29(6), 422–428. 10.4037/ajcc2020733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson R, & Menkin E (2003). Writing a condolence letter. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6(1), 77–78. 10.1089/10966210360510145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Palliative care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care