Abstract

Little is known about the decision-making processes around seeking more supportive care for dementia. Persons with dementia are often left out of decision-making regarding seeking more supportive care as their dementia progresses. This paper provides a description of findings from the Decision-making in Alzheimer’s Research project (DMAR) investigating the process of decision-making about transitions to more supportive care. We conducted 61 qualitative interviews with two stakeholder groups: 24 persons with dementia, and 37 informal caregivers to explore supportive care decisions and associated decision-making factors from the perspectives of persons with dementia and their caregivers. We identified four main decisions that persons with dementia and their informal caregivers played a role in: (1) sharing household responsibilities; (2) limiting routine daily activities; (3) bringing in formal support; and (4) moving to a care facility. Based on our findings we developed a schematized roadmap of decision-making that we used to guide the discussion of our findings. Four crosscutting themes emerged from our analysis: unknowns and uncertainties, maintaining life as you know it, there’s no place like home and resource constraints. These results will be incorporated into the development of instruments whose goal is to identify preferences of persons with dementia and their caregivers, in order to include persons with dementia in care decisions even as their dementia progresses.

Keywords: Decision-making, dementia, caregiving, supportive care, decision tools

Introduction and Background

Persons with dementia are often excluded from important care planning discussions and decisions such as transitions to higher levels of supportive care (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013; Menne et al., 2009; Menne & Whitlatch, 2007). This lack of involvement often occurs because persons with dementia have more difficulty expressing their preferences as their disease progresses, especially regarding more complex decisions (Miller et al., 2019). As a result, family (informal) caregivers’ perspectives are substituted instead (Boyle, 2013; Samsi & Manthorpe, 2013; Teri & Logsdon, 1991). Although caregivers typically make surrogate decisions based either on what they predict the care recipient would choose (i.e. substituted judgement), or what is in the best interest of the care recipient (Cheung et al., 2021; Garvelink et al., 2018), prior studies indicate that caregivers’ health care preferences may differ from the person with dementia (Bamford & Bruce, 2000; Carpenter et al., 2006; Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2002). Further, their consideration for care recipients’ preferences diminishes over time and as the disease progresses (Reamy et al., 2013; Shalowitz et al., 2006).

A supported decision-making process is recommended by ethicists as the preferred alternative to surrogate decision making (Peterson, Karlawish & Largent, 2021). Ideally, it allows persons living with dementia to stay involved, and select one or more close and trusted supporters to assist them in making decisions that are aligned with their values (Jaworska & Choing, 2021). The involvement of persons with dementia in decisions regarding their own care is essential to personhood and person-centered care (Burshnic & Bourgeois, 2020; Lanzi et al., 2017; Manthorpe & Samsi, 2016; O’Connor & Kelson, 2009). Further, supported decision-making is often preferred by persons living with dementia their families (Miller, Whitlatch & Lyons, 2016). Several studies have established that persons with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are capable of stating their values for everyday care and activities (Bolt et al., 2021; Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001; Smebye et al., 2012; Whitlatch et al., 2005), and feel less marginalized and are seen as more autonomous when they participate in these decisions (Menne et al., 2008a; Miller et al., 2018). Keeping persons with dementia involved in planning and decision making can also improve their well-being and reduce dementia symptoms (Bonds et al., 2021; Menne et al., 2008a; Mitoku & Shimanouchi, 2014; Samsi & Manthorpe, 2013). However, there is a lack of research investigating how persons living with dementia manage to remain involved in decision making, and how family members can engage them in discussions about their values and preferences, especially for the many complex decisions that need to be made over time.

The spectrum of supported decisions to be made in the context of dementia ranges from everyday choices (e.g. regarding activities of daily living, physical activity, intimacy and socialization) (Miller et al., 2016, 2019; Reamy et al., 2013; Whitlatch et al., 2005) to more complex decisions regarding advance care planning and end-of-life care (Browne et al., 2021; Harrison Dening et al., 2019; Jimenez et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2021). In between these two ends of the decision-making spectrum, there are a variety of decisions that may need to be made about higher levels of supportive care such as hiring formal caregivers or other types of in-home help (e.g., use of cleaning or meal services, medical transport), using adult day care services, or seeking an appropriate care facility. However, studies on higher level supportive care decisions typically have been limited to those focusing on transitions from home to long-term care facilities (1) among non-cognitively impaired individuals (Chaulagain et al., 2021; Hirschman & Hodgson, 2018; McCullough et al., 1993; Roy et al., 2018), (2) from the perspective of caregivers for persons with dementia but not including persons with dementia themselves (Caldwell et al., 2014; Merla et al., 2018), and (3) on shared decision making between persons with dementia and caregivers among small samples (Garvelink et al., 2018).

Few studies have examined decision-making processes and decisions about supportive care from both the perspective of the caregiver and the person with dementia. We sought to address this gap in the literature by conducting a qualitative study with two objectives: 1) to understand decisions and associated decision making factors related to seeking more supportive care from the perspective of persons with dementia and 2) to explore the experiences of persons with dementia and their informal caregivers as they made decisions across the dementia care trajectory, with a focus on the largely unexplored period when supportive care needs increase. We chose to use qualitative methods to understand the lived experiences of persons with dementia and caregivers and to center the voices of persons with dementia; an important strength of our study. We describe here key decisions made and crosscutting themes related to decisions to seek more supportive care from the perspective of persons with dementia and caregivers.

Methods

This study is part of the larger Decision Making in Alzheimer’s Disease (DMAR) study (https://depts.washington.edu/hprc/projects/dmar/), a 5-year NIA-funded research project that seeks to ensure that the voice of the individual with dementia is understood regarding preferences around care decisions through the design of a discrete choice experiment (DCE) tool.

Recruitment

We used purposive sampling to recruit individuals with mild to moderate dementia and informal caregivers of persons with dementia for participation in semi-structured interviews (Patton, 2014). We expanded our sampling to include persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to gain insight on early decisions related to memory loss. When possible, persons with dementia and their caregivers were both recruited. Participants were recruited from the University of Washington’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (UW ADRC) registry, and from community partner organizations, including assisted living facilities, memory care facilities, senior centers, and the Washington state Alzheimer’s Association. We worked with community agencies and the ADRC to recruit individuals from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds.(Sharma et al, 2022) A one-page flier explaining the study was sent to liaisons at partnering community agencies for distribution.

Participant screening took place over the phone. Inclusion criteria included participants with cognitive impairment 65 years or older, fluency in written and spoken English, and caregivers 18 years or older. Although all interviews were conducted in English, an experienced bilingual Spanish-speaking interviewer was hired to facilitate recruitment and interviewing of Hispanic/Latinx participants. Exclusion criteria for persons with dementia included having a Dementia Severity Rating System (DSRS) Speech and Language score of a 4 or higher. The consent process primarily took place over Zoom. If the participant could not use Zoom, verbal consent was obtained via phone. The degree of memory loss and function were assessed through caregivers’ responses to the DSRS. Persons with dementia answered one question from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS): “During the past 12 months, have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse?” (CDC, 2019). We interviewed the caregiver solely in cases where the person with dementia had limited English proficiency, as well as when cognitive screening indicated a person with dementia would be unable to complete the interview. Caregivers who participated solely were asked to answer the BRFSS for the person with dementia.

Interview Guide:

Research team members developed the interview guides with input from dementia experts and community representatives. The research team pretested the interview guide with a person with dementia and caregiver dyad and modified based on feedback. (Interview guides are available in supplemental files.) All study procedures and materials were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (UW IRB 00009803).

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between September 2020 and December 2021 by three staff experienced in qualitative interviewing. The interviews lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes and were conducted via Zoom or phone. Participants provided consent to video and/or audio recording. Participants received a $25 gift card for completion of the study.

In the case of dyads, when possible, we interviewed each person separately, interviewing the person with dementia first, to center their perspective. We asked caregivers to leave the room during the interview, but to be available in case the person with dementia required assistance.

After obtaining demographic information, the semi-structured interviews focused on the course of dementia including symptoms, assistance needed and provided, and informal or formal caregiving. Persons with dementia and caregivers were asked to describe decisions that had been made or were being considered related to memory loss and the need for supportive care. In the context of this study we defined supportive care as informal and formal (paid) care to assist the person with dementia in activities of everyday life, including support of instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs), such as driving and managing finances as well as activities of daily life (ADLs) such as dressing and personal hygiene (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Additionally, participants were asked to describe any barriers and facilitators to their decision making and to identify the key factors that influenced their decisions. Interviews were transcribed by Rev (Rev.com., n.d.). All transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and were de-identified prior to analysis.

Data Analysis

We developed an initial coding framework based on prior research involving factors related to older adults’ decisions about moving (Roy et al., 2018), decision making in the context of dementia (Garvelink et al., 2018; Orsulic-Jeras et al., 2019), person-centered care (Fazio et al., 2018; Kogan et al., 2016), as well preliminary surveys of older adults regarding factors involved in considering transitions of care.(Turner, Engelsemas et al. 2020) Research team members met weekly from January through mid-March 2021 to develop and refine the codebook, utilizing an iterative inductive qualitative analysis (Leavy, 2020) process as they read through transcripts. An investigator triangulation method was used by engaging multiple study team members to assist in coding to minimize bias and increase validity of our thematic analysis (Bennett et al., 2020; Patton, 2014). Three investigators coded 61 transcripts, double coding 50% of transcripts for each participant type, then single coding the remaining transcripts while continuing to review each other’s coding for agreement, and meeting to establish consensus on any disagreements as needed. We used the qualitative software program Dedoose (version 8.0) to manage the coding process.

General coding domains included decision timing, decision making processes (seeking diagnosis, preparing to age in place, providing/receiving IADL support, choosing in-home supportive care, obtaining adult day care services, and moving to a more supportive environment), and decision factors (health, values and beliefs, social, socioeconomic, environment, and supportive care). Using the constant comparative method, research team members collaboratively identified emergent themes from the codes for each participant group, identifying the decision processes as well as factors that influenced decisions (Glaser, 1965).

Results

Participant Description

We contacted 114 potential participants by phone and email and 61 (54 %) individuals agreed to participate. Using purposeful sampling we sought to gain input from a variety of individuals in terms of age, ethnicity, race, income and level of dementia. This is reflected in Table 1, which describes the participants. We interviewed 24 persons with dementia with a range of dementia severity of 1 to 27 (based on DSRS). Mean age of persons with dementia was 75 (range 65-88 years). We interviewed 37 informal caregivers (23 spouses/partners, 14 adult children), with a mean age of 65 (range 42-88 years). We did not interview the person with dementia for 19 of the caregivers, due to limited-English proficiency (5), unwillingness to participate (2), death (5) and severity of dementia (7).

Table 1.

Participant Descriptive Statistics

| Description | PWD* n (%) | CG* n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 24 | 37 |

| Gender Female |

8 (33%) |

27 (73%) |

| Age 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 |

NA NA NA 5 (21) 15 (63) 4 (16) |

0 4 (11) 5 (14) 17 (46) 9 (24) 2 (5) |

| Ethnicity Hispanic Not Hispanic Unknown |

0 24 (100) 0 |

5 (14) 32 (86) 0 |

| Race Asian Black / African American Mixed Race / Other White |

1 (4) 1 (4) 1 (4) 21 (88) |

3 (8) 5 (14) 5 (14) 24 (64) |

| Education Highschool diploma Some college but no degree Associates degree Bachelor’s degree Graduate degree |

2 (13) 2 (8) 12 (50) 7 (29) 0 (0) |

3 (8) 5 (14) 4 (11) 10 (27) 15 (40) |

| Average Household income (yearly) $0-24,999 $25,000-49,000 $50,000-74,999 $75,000-99,999 $100,000-124,999 $125,000 and up Prefer not to answer |

1 (4) 3 (12.5) 6 (25) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) 4 (17) 4 (17) |

0 (0) 7 (19) 7 (19) 7 (19) 1 (3) 10 (27) 5 (13) |

| Level of dementia severity (DSRS) MCI (by dx) Mild (0-18) Moderate (19-36)** Severe (37-54)** [via CG interview] |

7 12 5 0 |

10** 3** |

PWD indicates persons with dementia; CG indicates caregivers. These abbreviations are used in tables and references to excerpts throughout the text.

A subset of 13 interviewed caregivers reported DSRS scores for PWD who were not interviewed. 10 CG reported moderate dementia in non-interviewed PWD. 3 CG reported severe dementia in non-interviewed PWD.

Decision Making Around Transitions in Care

Twenty-four persons with dementia and 37 caregivers described the supportive care decisions they had already made, were currently considering, and were planning for the future. The majority of participants spoke about past and present decisions rather than future decisions. This was particularly true for persons with dementia, of whom few engaged in discussion about hypothetical or future decisions.

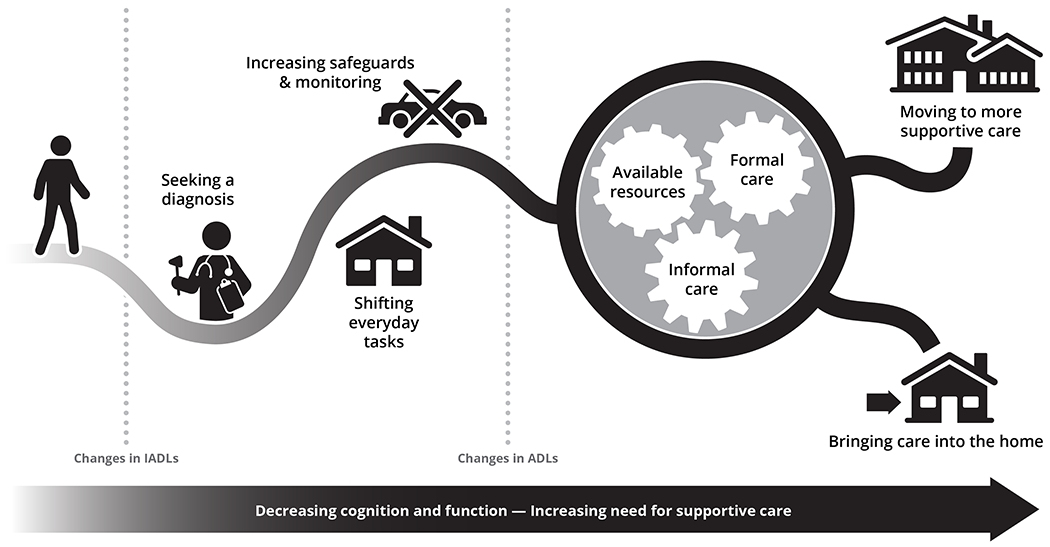

While each person’s decision timing and choices were unique, we identified common decisions about seeking supportive care that took place over time. These decisions often included: (1) seeking a dementia diagnosis, (2) shifting everyday tasks and household responsibilities to others, (3) increasing safeguards and monitoring for the persons with dementia, and (4) increasing care by either expanding informal support from family and friends, moving formal caregivers into the home, or moving to a more supportive care environment. Figure 1 depicts a simplified path encompassing various common decisions participants described ranging over the disease trajectory. It is worth noting that persons with dementia have varied trajectories and may not all face the decisions shown in Figure 1. Further, their disease trajectory and decision-making path may not be linear, and they may navigate different tensions and tradeoffs based on their individual situations. Still, Figure 1 provides a starting point to think about some of the common decision points that arise for persons with dementia and their caregivers. The following section describes these decisions in more detail. See Table 2 for a summary with representative excerpts.

Figure 1.

Decision-Making Path

Table 2.

Supportive Care Decisions with Representative Excerpts

| Decision | Description | Participants | Excerpts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeking diagnosis | Early decision to take steps to meet with health care provider(s) about memory loss or associated symptoms | 34 Participants (25 CG, 9 PWD) | I went to see my … doctor and … he suggested that I start to see some people who could see if they could figure out what’s going on and why. (PWD_111) |

| Sharing household responsibilities | Early decision to shift previously held household tasks (IADL tasks, etc.) such as paying the bills, managing appointments and scheduling to spouse or adult children. Often not an explicit decision but a gradual taking over of a task by another individual, involving both implicit and explicit decisions making among the dyad. | 28 Participants (17 CG, 11 PWD) |

I do not pay bills or manage finances. [CG_129] does all of that now. I just can’t get it straight, and sometimes I don’t know how the hell I made a mistake, but I sure did. (PWD_129) I think I slowly began to incrementally … to take on other stuff. (CG_106) |

| Reducing activities outside the household |

Early/Middle decision Decisions to reduce scope of job or leave employment because of difficulties performing job duties, such as driving, employment |

25 Participants (19 CG, 6 PWD) | I remember we were driving one day and it was foggy, and he couldn’t find his way out of the parking lot. And I realized that this cognition problem was bigger than I thought. …. So I made him stop the car, and I drove from that day forward. (CG_129) |

| Increasing informal supportive care | Middle decision: Decision to bring in or move closer to family and friends or retirement community to increase access to support. | 18 Participants (18 CG, 1 PWD) |

It would be great if [CG_111] could take care of whatever I need, I’d rather have that, rather than pay somebody to come in. (PWD_111) Well, it was just very clear that he was not able to do the jobs that were required of him. And I was working at another place. And so I quit that job … to take over the role that he played at the bakery. … He knew that he couldn’t do it anymore. (CG_111) |

| Bringing in formal support | Middle decision: Deciding to hire formal care giver or attend an adult day care, seek help with specific activities or provide monitoring | 15 Participants (14 CG, 1 PWD) | People coming in to help, that’s probably going to happen…. If we have to bring people in to take care of me and that makes it easier for [CG_113], then I’m okay with that. (PWD_113) |

| Moving to a care facility |

Early decision: to move to retirement facility with spectrum of care Late decision: Decision to move out of home and into a more supportive living environment (assisted living or memory care) |

13 Participants (10 CG, 3 PWD) |

Well, we decided, CG_109 and I and our kids, that it would be best if I was not doing all of the things in the house and then, getting groceries, all of that sort of thing... (PWD_109) Well, … I guess if I had no brain function, and someone’s got to take care of me, and I have no conversations with anybody at that point, if it was better for the family to put me into a facility and we could work it financially, absolutely. (PWD_134) |

Seeking a diagnosis

The earliest decisions described by participants were driven by the initial changes in cognition that impacted everyday activities. One of the first decisions was to seek a diagnosis. This process, referenced by roughly one third (9/24) of persons with dementia and two thirds (25/37) of caregivers, was often long and the decision to seek a diagnosis, while typically made by the affected individual, was often precipitated by suggestions from a concerned partner or adult child.

And then, he suggested that I start to see some people who could see if they could figure out what’s going on and why. And so that was when I started to look for doctors and then, took about three years to finally find a doctor that knew what was going on with me. (PWD_111)

Shifting of responsibility for everyday tasks

As dementia symptoms surfaced, roughly half of both persons with dementia (11/24) and caregivers (17/37) described incremental decisions connected to a gradual shift in everyday responsibilities, such as managing information, medication, paying household bills, and performing household chores. Among couples, decisions to take over these tasks were often shared, which meant a continuation of identity as a team within the household, with the non-affected partner starting to take more of the load.

As dementia symptoms progressed, informal caregivers took over more tasks that had either been shared or performed solely by the persons with dementia. Often these decisions were explicitly made by the couple. However, multiple caregivers described that the reassignment of tasks was complicated by the person with dementia’s general lack of awareness of their change in function and increased needs.

Increasing safeguards and supportive care at home

Participants described the progression of dementia as being characterized by increasing memory loss and a resulting need for increased oversight and monitoring. (See Figure 1.) Eight caregivers described strategies of monitoring the person with dementia based on the realization that it was no longer safe to leave them unattended, particularly due to wandering and concerns about cooking safety.

Family members sometimes had to alter their work schedules to be home more, which often involved making decisions about finances and scheduling. Decisions by caregivers to increase safeguards related to wandering included physically altering the home environment through installation of locks on doors, cameras, and fenced in yards. These decisions often raised tensions as they limited the independence of the person with dementia.

That’s been a fear for me, that if he wandered away from the house, that something terrible would happen to him. So that’s why my doors are the way they are and the yard’s locked. (CG_105)

Tensions around increasing safety at the expense of limiting the person with dementia’s independence often involved struggles between the person with dementia and family members, particularly in the decision for the person with dementia to stop driving. This decision came up frequently in interviews with both persons with dementia (6/24) and caregivers (13/37). Most participants described the decision to stop driving as one that was based on the guidance of family members or medical professionals, and not generally initiated by the person with dementia. These conversations involved many discussions over time. In some cases, family members described avoiding overt shared decision-making to avoid conflict, resorting to hiding the car keys, or selling the car to deter the person with dementia from driving.

… all the things that were important to him are absolutely juxtaposed to what we needed to do to help keep him safe, and healthy, and all that. And yeah, big, big, big clash. (CG_141)

Increasing Care

As memory and function declined further, decisions often involved increasing informal care, bringing in formal care to the home, or moving to a more supportive environment.

So now it’s like trying to come to that decision. It’s like where are we going to need help? And are we going to bring that help here to the house, or are we going to have my mom going to a nursing home, and visit her every day? I mean, it’s a lot of decisions to be made. (CG_119)

Increasing and expanding informal care:

In the context of increasing needs, many family members and informal caregivers described a desire to continue to keep their loved one home. This desire was often based on wanting to honor the voiced preference of the person with dementia, or the cultural value of caring for family members at home. Half of caregivers (18/37) described meeting the need for additional care within the family system. At times, these decisions raised tensions within a family. For example, one participant described family conflict surrounding the possibility of having an adult child who was perceived as being irresponsible help with care. Usually, these decisions depended on the availability of family members and at times necessitated changes to a caregiver’s employment (e.g., retiring or quitting one job to take on another). Some dyads chose to move to be closer to family for support, sometimes moving in with family members, or chose to minimize household duties by downsizing.

Bringing in Formal Support:

The decision to seek part-time formal supportive care was often precipitated by the need for increased monitoring and safety to offset caregiver or family burden. Fourteen CG described making this decision when they were not able to provide the level of supportive care needed because of behavior and symptoms related to dementia, such as sleeplessness, incontinence, aggressive behavior, wandering, and unsafe household behavior (e.g., leaving things on the stove). While a few persons with dementia explicitly volunteered their concerns about the burden that their illness was putting on their spouse or family members, most did not mention how much support they were getting from others, or caregiver burden as a factor influencing their decisions.

Moving to supportive care environment:

Several participants in early stages of dementia described being involved in the decision to seek formal care. In particular, anticipation of the more severe stages of dementia led three dyads to choose early on to move to a retirement facility that provided a continuum of care. However, it was generally difficult to engage participants with dementia in concrete discussions regarding transitioning to more supportive care in the future. Nine caregivers and 6 participants with dementia mentioned thinking about the possibility of needing to move to obtain formal care sometime in the future but were not actively planning ahead.

Others (4 caregivers, 5 persons with dementia) did not want to even entertain the idea of a future need for more supportive care. Caregivers of persons with severe dementia indicated in hindsight that lack of planning contributed to a stressful and reactive decision-making process in the later stages of dementia. For example, precipitating events such as hospitalization, or the caregiver’s inability to continue providing informal care often necessitated rapid decisions under emergency circumstances, and the preferences of the person with dementia could not be incorporated into the decision-making process.

Emergent Themes in Supportive Care Decision Making

We identified four recurring, cross-cutting themes related to supportive care decision-making in interviews with persons with dementia and caregivers: “uncertainty and unknowns,” “maintaining life as you know it,” “there’s no place like home,” and “challenges of resource constraints.” Additionally, in the context of these themes, we identified several factors that influenced decision-making: cognitive function, participant values, environmental realities, and social structures.

Theme 1: Unknowns and uncertainty

The first theme was a lack of understanding and uncertainty about the unknown, including the unpredictable progression of disease and ramifications for future supportive care needs.

So, I think that would be really helpful to some people, like a definition of what the illness is. I know they don’t want to scare people, but the inevitability of it with this particular disease is pretty…, people should know what they’re up against and prepare. (CG_129)

The lack of experience and understanding about the course of the disease and care options led to a dependence on preconceived opinions based on stereotypes or past experiences.

I feel like if I put her in a home, she’s going to be dead, and I’m not having that. (CG_120)

Decisions about events and situations that one could not predict, much less control, felt like guesswork. This uncertainty led to difficulty making decisions, second guessing, and sometimes regret.

It’s almost impossible to plan adequately because, again, you just don’t know what you’re planning for. You’re planning for one year. You’re planning for 10 years. (CG_137)

Contributing to the unknown were challenges in accessing information about the disease and navigating the system to obtain care.

But, that’s the kind of attitude that this kind of thing gives to not just me, but people in general that have to deal with that because you have so many hoops to jump through, basically, and you got to find the right ones and it’s just … There is no direction, really. (CG_118)

On the other hand, individuals with familiarity with the disease, because of experience with another family member or as a health care provider, were more likely to have discussed making plans for the future.

I mean, we talked about certain things watching both of our parents kind of go through health situations, what kind of care they had or didn’t have. … So you kind of talk about things hypothetically. (CG_123)

Theme 2. Maintaining life as you know it

Many participants, both persons with dementia and caregivers, expressed a desire to live in the present and to preserve life as they knew it for as long as possible. Efforts to maintain the status quo throughout the progression of the disease were often mentioned and transcended planning or active decision making. Reasons for living in the present and consequently avoiding discussions about planning for the future included denial, a deep desire to stay at home, difficulty in predicting the future, and the advice of others (including health care providers) to live “one day at a time.”

Participants exhibited a general reluctance to talk about future supportive care decisions that would involve a greater level of care or loss of autonomy, such as bringing formal care into the home or moving to assisted living or memory care. In response to being asking about future supportive care decisions, participants typically responded as follows:

It looks to me it’s like we’re on a path, or a road, and we haven’t come to that bridge yet, so I haven’t really thought about it that much. (PWD_113)

But we’ll deal with that when we… get there. (CG_103)

In some cases, this seemed to be connected to uncertainty and unknowns. However, for at least some participants with dementia, the focus on the present appeared to be connected to decreasing cognitive abilities, which impacted planning and decision-making throughout the course of the illness.

Generally, caregivers were more likely than the person with dementia to discuss current or future care needs. In particular, caregivers would raise concerns about safety, including decisions about driving or wandering. Participants with dementia rarely mentioned issues related to safety or the increased need for monitoring their activities. Letting go of the independence afforded by driving a car or accepting help from outside the family was in direct conflict with the determination to maintain one’s current life.

If you ask [PWD_101], he thinks that he’s got all that going on still…. He can totally be by himself without any problem. I feel there’s a certain amount of unawareness, not self-awareness. I feel that’s typical to a lot of folks if you’re a person with dementia, trying to plan things out. (CG_101)

Theme 3: There’s no place like home

Closely related to the desire to maintain life as you know it was the importance of home. There were many references by both persons with dementia and caregivers at different stages of the dementia journey to the value of home, whether that meant one’s physical home, connection with family and friends, or a community. Home represented familiarity, continuity, safety, and being with others, as well as physical details such as favorite foods or one’s garden. In some cases, home was described as a place that was integral to one’s identity and many participants with dementia expressed resistance to the idea of ever moving elsewhere despite changes which were occurring due to their dementia.

No. I’m not leaving. I love our house. (PWD_104)

Family members described their priority of having the person with dementia stay home for “as long as possible” (CG_122), working to juggle availability of informal care in conjunction with bringing in differing levels of formal supportive care they could afford as the dementia symptoms progressed. Many caregivers expressed wanting to honor the preference of the person with dementia. Some were motivated by the cultural value of caring for family members.

So culturally, I would say that we pretty much come from a family culture that does try to care for our elders as much as possible, in the home or in their home and not facilities, unless absolutely necessary. (CG_121)

Several participants with dementia, early in the disease progression, expressed conflict between their wanting to stay at home and concern about being a burden.

There’s a lot of things that you can do, but again, there’s just that deep-down feeling like I just hate to have my family just having to spend all their time trying to care for me. (PWD_134)

At the same time, those with dementia tended to depend on their family members to provide support, and many viewed home in the context of their family relationships. Some participants described moving closer to family to access support.

I think the primary factor for [PWD_126] was family, was being able to be where family is and having that support. I would say that’s the major factor for choosing to move. (CG_126)

In such instances, the concept of home was closely tied to family and friends providing supportive care.

Theme 4. Challenges of resource constraints

The tension between decision-making ideals and the reality of limited resources was a theme throughout. Resources that were identified by participants as limited included availability of informal caregivers, the ability to pay for formal caregivers, and access to affordable care facilities. Eventually, despite the strong preference to stay in the present and to manage caregiving as a family at home, many caregivers expressed that it became unsustainable. Some caregivers who were willing and able to look ahead described expecting that at some point they would not be able meet all the needs of their loved one because of resource constraints.

I don’t really want him to go anywhere else. I mean, he’s built this house so that that doesn’t have to happen. So, it would be a matter of just the finances of having a caregiver and then there’s multiple caregivers because I know when you’re talking about one, you’re probably talking about five to seven. … between the hours and the availability and people calling in sick and things it’s a lot. (CG_103)

For those who were able to articulate preferences related to a moving to a supportive care facility, there were often tensions between concerns about caregiver burden and safety and the realities of financial and informal care resources.

She wouldn’t want to be a problem to anybody, and she doesn’t want anyone to spend any money on her. … But to care for her, I would have to … hire someone. (CG_107)

As participants faced the possibility of seeking formal care (whether at home or in a facility), they considered the financial ramifications of these choices.

I was anxious about the fact that I was learning that there isn’t as much available in terms of housing for seniors, whether it just be an individual unit, that was within my financial range. (PWD_115)

A number of caregivers described the lack of available facilities, whether because of limitations regarding the stage of dementia, or out-of-pocket costs related to access to Medicaid, long-term care insurance, or personal financial resources. High quality facilities were available for some, but out of the realm of possibility for others. Some participants described achieving official caregiver status or support through Medicaid. Others chose facilities that they suspected might provide lower quality care because there was no other choice.

My sister found what my mom could afford… She (mother) was single, she had a very small pension, she had Medicare and very limited resources. The facility was very substandard. (CG_121)

Finally, for some the need for formal care would necessitate selling their home, which was difficult to contemplate for the informal caregiver as well as the person with dementia.

But, this is the only place I can live now. I have so much equity here that I can’t move. And, I love this place, too. I wouldn’t want to move unless I actually had to. (CG_118)

Discussion

Our study aimed to advance our understanding of the lived experiences of persons aged 65 and older with dementia and their informal caregivers as they made decisions across the dementia care trajectory, with a focus on the time between diagnosis and major decisions about transitions in living situation. Key strengths of our study were the inclusion of persons with dementia as well as the sociodemographic diversity of our participant sample. We found that decisions regarding transitions toward more supportive care varied over the course of dementia and focused primarily around four main decision categories: 1) a shift from everyday tasks and household responsibilities 2) an increase in the safeguards and monitoring for the person with dementia, 3) an increase in informal or formal caregivers and 4) consideration of an alternate place of care. Across these different decisions we identified four themes: the challenges of unknowns and uncertainty, maintaining life as you know it, the importance of home, and resource constraints.

Participants with dementia and their caregivers discussed both implicitly and explicitly the values that informed their decisions. Researchers have previously developed measures for identifying the values of persons with dementia during every day decision making, as well as factors associated with perceptions of their care values (Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001; Menne et al., 2008b; Miller et al., 2018, 2019; Whitlatch et al., 2005). It is clear that soliciting care values is an important part of the decision-making process. Other prior studies have focused on learning about the preferences of persons with dementia and incorporating them in end-of-life decisions (Dening et al., 2013; Hill et al., 2017; Winter & Parker, 2007), and working with clinicians to optimize person-centered palliative care (Eisenmann et al., 2020; Harrison Dening et al., 2019; Walsh et al., 2021). In the current study, although individual values were a key aspect of decision making, contextual factors such as environment and community were also identified as essential to decision making. Further, the results of this study indicate that persons with dementia and their family members undergo a process of weighing the various tradeoffs of supportive care decisions within the context of contextual factors and competing values, which can make the supportive care decision-making process more tense and complex.

Many of the decisions described in our study involved tradeoffs between safety concerns and minimizing caregiver burden, and values related to autonomy, finances, family culture, and quality of care. Unknowns and uncertainties (Theme 1) were a constant, adding ambiguity or delays to decision making. Although several of our participants referred to this process as being on a road or path, (reflected in Figure 1) participants’ experiences underscored the reality that while there are commonalities, each person’s journey through dementia is unique, unpredictable and often nonlinear (Hall & Sikes, 2018). As memory loss progressed and safety concerns (for the person with dementia and others) increased, tradeoffs often involved participants with dementia giving up some level of autonomy in favor of increased safety often at the expense of greater caregiver burden. The decision for the person with dementia to stop driving was described as especially challenging, fraught with tensions between safety and autonomy (Sanford et al., 2020; Stasiulis et al., 2020). This tension was acknowledged by some participants with dementia but was generally described more by caregivers. They detailed the tradeoff of preserving autonomy for as long as possible for the person with dementia (e.g. driving, managing finances), while also being fearful of the ramifications. Thus, decisions such as whether to continue driving were made with the influence of others (family members or health care professionals) sometimes after a precipitating event such as getting lost or dangerous driving, when it became clear that prioritizing autonomy could threaten the well-being and safety of the persons with dementia, caregivers, family members, or others.

Uncertainty about the disease and its progression and difficulty with planning also appeared to be connected to a lack of available information sources (Allen et al., 2020). It has been noted that older adults and their family members have a tendency to turn to what and who they know best for information and help (Walker et al., 2017). Participants in this study applied the experience of dementia (e.g. through family history or as healthcare professionals) to motivate future planning discussions early on with family and friends. Others carried stigmatizations or misconceptions about the disease and care facilities and thus avoided planning. In our interviews, many caregivers noted in retrospect that they did not fully understand the diagnosis or the importance of planning soon enough. It is important for health care professionals and organizations to assess an individual’s level of knowledge and experience (Rutkowski et al., 2021; Soong et al., 2020). Tailored levels of information at appropriate points in time may help to ensure understanding of the disease progression and support decision making and planning for the future (Washington et al., 2011; Werner et al., 2017). At the same time, the uncertainty expressed by many participants could be related to fear, denial and stigma associated with Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias (Kaldy, 2014; Macquarrie, 2005). Future research should explore more deeply the interaction of these variables in the context of information provision.

A significant finding identified in our interviews was that many participants with dementia and some caregivers wanted to live in the present (Theme 2), to maintain autonomy and resist making choices that would reduce quality of life and the scope of their world. Some had difficulty contemplating future needs, let alone discussing planning for the future. The difficulty participants with dementia had in imagining and discussing future decline and the need for supportive care served as a barrier to planning and decision making. The commonly voiced response that “we will make that decision when we get there” underscored both the uncertainty of the progression of the disease, and a desire to avoid more concrete planning for the future. This preference was voiced by both individuals very early with minimal cognitive decline, as well in more advanced stages. This underlines the complexity of helping support persons with dementia in making decisions related to care transitions in the context of impaired insight, executive function, and challenges with prospection (future thinking) which may impact their ability to imagine future scenarios (Irish & Piolino, 2016; Kensinger, 2009; Orfei et al., 2010; Requena-Komuro et al., 2020).

The overriding desire to keep the person with dementia at home (Theme 3) for as long as possible was motivated by personal, familial and cultural values and reflected the statistic that two-thirds of persons with moderately severe dementia live at home (Harrison Dening et al., 2019). Although these values were held across our sample, the value of filial piety, or “we take care of our own” (Brewster et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2015) emerged most frequently in interviews with racially and ethnically minoritized individuals as well as adult children. As the needs of the persons with dementia increased, a tension sometimes developed between these cultural values, caregiver burden, and resources that was embedded in complex family relationships that often went beyond dyads. Tensions related to safety, caregiver burden, and external environmental constraints were of particular concern to adult children who were caregivers. Some families had available resources (Theme 4) to bring more informal or formal support into the home, but not all. Available resources included proximity of family members (Choi et al., 2021), insurance, savings, and availability of affordable facilities. Participants (mostly caregivers) discussed a challenging process of weighing the availability of family members to provide care in the home with the need to minimize caregiver burden. A common solution seemed to be developing a patchwork of informal support that in some cases included formal care (in the home and/or adult day care). These tensions suggest that new solutions, such as more home-based dementia care (HBDC) programs, especially those supported by new payment models and rewards, may be especially important (Samus et al., 2018).

The eventual decision to move to a long-term care facility is preceded by varying combinations of informal and formal care, and often raises conflicts between values of belonging and home, the burden on others, and the challenge of minimal resources (Førsund et al., 2018; Roy et al., 2018). Only a few participants in our study reported choosing to move to a retirement home early in the progression of dementia. Most descriptions of the decision to move included navigating tensions between uncertainty about the progression of the illness, availability of financial resources, guilt about moving the person with dementia from home, and concerns about caregivers’ quality of life, safety, or burden. In cases where caregivers anticipated burden and safety demanding a move, having adequate resources was a concern.

Our sample of persons with MCI, mild and moderate dementia experienced tensions and tradeoffs in unique ways and demonstrated variability in how they participated in decision-making - from active involvement to deference to family members, friends and providers who were trusted to take into consideration their values and preferences. A clearer understanding of these tensions and tradeoffs, as well as underlying environmental realities, is necessary to operationalize models of person-centered or supportive decision-making in dementia care transitions that facilitate living in the present and planning for the future.

Future Research

Based on our findings, we recommend the following next steps in researching person-centered decision making for supportive dementia care:

Further investigate tensions between the goal for persons with dementia to be involved in decision making for supportive care vs. their challenges with prospective thinking and desire to live in the present.

Explore factors that contribute to the ideal timing for eliciting preferences and discussing future care in the context of cognitive change.

Investigate methods to assess informational needs of persons with dementia and their informal caregivers (dyads) and provide tailored and timely information regarding dementia resources.

Explore supportive processes and tools for preparing dyads and family members for decision making.

Develop effective ways to help dyads and family members weigh tradeoffs associated with different decisions, to support effective future care planning. Example: through discrete choice experiments.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, recruitment and conduct of study interviews occurred during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the virtual nature of the interviews may have affected interview content and rapport-building with the persons with dementia and their caregivers. In addition, because we conducted interviews over Zoom, our study sample was limited to participants with access to and support with using technology. Second, although we utilized multiple approaches to try and recruit a diverse sample of persons with dementia and informal caregivers, the majority of our study participants identified as Non-Hispanic white. Additionally, although approximately two thirds of people with dementia are women, our sample of persons with dementia was approximately two thirds male. The majority of participants (63%) were recruited from the ADRC Research Registry, a participant pool that are generally with higher education levels and income than the general United States population of individuals affected with dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2022). Interpretation of the interview transcripts may have been subject to researcher bias. However, the research team is experienced in qualitative analysis and used triangulation and double coding to minimize research bias in interpretation of our results.

Conclusion

As persons with dementia and caregivers travel down the path of progressive memory loss there are common decisions that are made to provide the supportive care needed. Understanding the types of decisions and the factors that are weighed in making those decisions is critical to supporting both the person with dementia and informal caregivers as they navigate seeking additional care. Given the difficulty most individuals experienced in discussing future care decisions, as well as the complexity of trade-offs and the variety of factors weighed in making those decisions, our team is exploring the use of Discrete Choice Experiment tools to easily and efficiently identify preferences of people in cognitive decline and their caregivers in making decisions about transitions in care. Our hope is that by identifying preferences and differences between individuals and their caregivers our tool can facilitate discussions and help person with dementia remain in the decision-making process even as their cognition declines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Miriana Duran for her assistance with interviewing, Wes O’Seadna for his work on the figure design and Alyssa Bosold and Annie Chen for their review of the manuscript.

AUTHOR BIOs

Jean O Taylor is a research scientist at the University of Washington in the Department of Health Services. Her training and research has focused on consumer based health information technology and decision sciences in the context of aging, dementia, breast cancer, and HIV.

Claire Child is a physical therapist, teaching associate, and PhD student in the School of Medicine, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Washington. Her clinical and research interests are in supporting people living with chronic diseases and disabilities to optimize safety, physical function and activity levels as they age.

Mary Grace Asirot is a Research Coordinator at the University of Washington. She has been involved in a number of research studies related to neurology, including dementia, cerebrovascular accidents, and epilepsy.

Rashmi Kumar Sharma is a palliative care physician and health services researcher at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Her research focuses on improving care for patients with serious illness and their families, particularly for minoritized populations, through communication-based interventions.

Lyndsey M Miller is research investigator with the Oregon Center for Aging & Technology and assistant professor of nursing at Orgon Health & Science University. Her work emphasizes ways to maintain engagement in life, independence in everyday function, and involvement in care planning among persons living with dementia and their family care partners.

Anne M. Turner is a professor and physician at the University of Washington, Seattle, Washington in the Department of Health Systems and Population Health/ Department of Biomedical Informatics and Medical Education. Her research interests include public health informatics, aging and the design of technologies to improve the health of older adults with and without cognitive decline.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethical Approval

All study procedures and materials were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (UW IRB 00009803).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen F, Cain R, & Meyer C (2020). Seeking relational information sources in the digital age: A study into information source preferences amongst family and friends of those with dementia. Dementia, 19(3), 766–785. 10.1177/1471301218786568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2022). 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bamford C, & Bruce E (2000). Defining the outcomes of community care: The perspectives of older people with dementia and their carers. Ageing & Society, 20(5), 543–570. 10.1017/S0144686X99007898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DM, Landahl MR, & Phillips BD (2020). Qualitative Disaster Research. In Leavy P (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research (p. 0). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190847388.013.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt SR, Steen JT, Khemai C, Schols JMGA, Zwakhalen SMG, & Meijers JMM (2021). The perspectives of people with dementia on their future, end of life and on being cared for by others: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, jocn.15644. 10.1111/jocn.15644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonds K, Song M, Whitlatch CJ, Lyons KS, Kaye JA, & Lee CS (2021). Patterns of Dyadic Appraisal of Decision-Making Involvement of African American Persons Living With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 61(3), 383–391. 10.1093/geront/gnaa086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle G (2013). ‘She’s usually quicker than the calculator’: Financial management and decision-making in couples living with dementia. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(5), 554–562. 10.1111/hsc.12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster GS, Bonds K, McLennon S, Moss KO, Epps F, & Lopez RP (2020). Missing the Mark: The Complexity of African American Dementia Family Caregiving. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(4), 294–301. 10.1177/1074840720945329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne B, Kupeli N, Moore KJ, Sampson EL, & Davies N (2021). Defining end of life in dementia: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 35(10), 1733–1746. 10.1177/02692163211025457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burshnic VL, & Bourgeois MS (2020). A Seat at the Table: Supporting Persons with Severe Dementia in Communicating Their Preferences. Clinical Gerontologist, 1–14. 10.1080/07317115.2020.1764686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell L, Low L-F, & Brodaty H (2014). Caregivers’ experience of the decision-making process for placing a person with dementia into a nursing home: Comparing caregivers from Chinese ethnic minority with those from English-speaking backgrounds. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(3), 413–424. 10.1017/S1041610213002020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter BD, Lee M, Ruckdeschel K, Van Haitsma KS, & Feldman PH (2006). Adult Children as Informants About Parent’s Psychosocial Preferences. Family Relations, 55(5), 552–563. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00425.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2019). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey (BRFSS) Questionnaire. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Chaulagain S, Pizam A, Wang Y, Severt D, & Oetjen R (2021). Factors affecting seniors’ decision to relocate to senior living communities. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102920. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung DSK, Tang SK, Ho KHM, Jones C, Tse MMY, Kwan RYC, Chan KY, & Chiang VCL (2021). Strategies to engage people with dementia and their informal caregivers in dyadic intervention: A scoping review. Geriatric Nursing, 42(2), 412–420. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Heisler M, Norton EC, Langa KM, Cho T-C, & Connell CM (2021). Family Care Availability And Implications For Informal And Formal Care Used By Adults With Dementia In The US. Health Affairs, 40(9), 1359–1367. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dening KH, Jones L, & Sampson EL (2013). Preferences for end-of-life care: A nominal group study of people with dementia and their family carers. Palliative Medicine, 27(5), 409–417. 10.1177/0269216312464094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann Y, Golla H, Schmidt H, Voltz R, & Perrar KM (2020). Palliative Care in Advanced Dementia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, & Kallmyer B (2018). The Fundamentals of Person-Centered Care for Individuals With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S10–S19. 10.1093/geront/gnx122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, & Whitlatch CJ (2001). Are Persons With Cognitive Impairment Able to State Consistent Choices? The Gerontologist, 41(3), 374–382. 10.1093/geront/41.3.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, & Whitlatch J (2002). Decision-making for persons with cognitive impairment and their family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 17(4), 237–244. 10.1177/153331750201700406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, & Nay R (2013). Being central to decision making means I am still here!: The essence of decision making for people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(2), 143–150. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Førsund LH, Grov EK, Helvik A-S, Juvet LK, Skovdahl K, & Eriksen S (2018). The experience of lived space in persons with dementia: A systematic meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 33. 10.1186/s12877-018-0728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvelink MM, Groen-van de Ven L, Smits C, Franken R, Dassen-Vernooij M, & Légaré F (2018). Shared Decision Making About Housing Transitions for Persons With Dementia: A Four-Case Care Network Perspective. The Gerontologist. 10.1093/geront/gny073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG (1965). The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, & Sikes P (2018). From “What the Hell Is Going on?” to the “Mushy Middle Ground” to “Getting Used to a New Normal”: Young People’s Biographical Narratives Around Navigating Parental Dementia. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 26(2), 124–144. 10.1177/1054137316651384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening K, Sampson EL, & De Vries K (2019). Advance care planning in dementia: Recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliative Care: Research and Treatment, 12, 1178224219826579. 10.1177/1178224219826579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SR, Mason H, Poole M, Vale L, Robinson L, & on behalf of the SEED team. (2017). What is important at the end of life for people with dementia? The views of people with dementia and their carers: End-of-life care for people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(9), 1037–1045. 10.1002/gps.4564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman KB, & Hodgson NA (2018). Evidence-Based Interventions for Transitions in Care for Individuals Living With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S129–S140. 10.1093/geront/gnx152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, & Piolino P (2016). Impaired capacity for prospection in the dementias—Theoretical and clinical implications. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 49–68. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, & Ho AHY (2018). Overview of Systematic Reviews of Advance Care Planning: Summary of Evidence and Global Lessons. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 56(3), 436–459.e25. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldy J (2014). Denial: When It Helps, When It Hurts. Caring for the Ages, 15(10), 1–7. 10.1016/j.carage.2014.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA (2009). Cognition in Aging and Age-Related Disease. In Squire LR (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Neuroscience (pp. 1055–1061). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-008045046-9.00569-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan AC, Wilber K, & Mosqueda L (2016). Person-Centered Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions and Functional Impairment: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(1), e1–e7. 10.1111/jgs.13873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzi A, Burshnic V, & Bourgeois MS (2017). Person-Centered Memory and Communication Strategies for Adults With Dementia. Topics in Language Disorders, 37(4), 361–374. 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living1. The Gerontologist, 9(3_Part_1), 179–186. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavy P (2020). Introduction to The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Second Edition. In Leavy P (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research (p. 0). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190847388.013.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macquarrie CR (2005). Experiences in early stage Alzheimer’s disease: Understanding the paradox of acceptance and denial. Aging & Mental Health, 9(5), 430–441. 10.1080/13607860500142853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe J, & Samsi K (2016). Person-centered dementia care: Current perspectives. Clinical Interventions in Aging, Volume 11, 1733–1740. 10.2147/CIA.S104618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough LB, Wilson NL, Teasdale TA, Kolpakchi AL, & Skelly JR (1993). Mapping Personal, Familial, and Professional Values in Long-term Care Decisions1. The Gerontologist, 33(3), 324–332. 10.1093/geront/33.3.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Judge KS, & Whitlatch CJ (2009). Predictors of quality of life for individuals with dementia: Implications for intervention. Dementia, 8(4), 543–560. 10.1177/1471301209350288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Tucke SS, Whitlatch CJ, & Feinberg LF (2008a). Decision-Making Involvement Scale for Individuals With Dementia and Family Caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 23(1), 23–29. 10.1177/1533317507308312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Tucke SS, Whitlatch CJ, & Feinberg LF (2008b). Decision-Making Involvement Scale for Individuals With Dementia and Family Caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 23(1), 23–29. 10.1177/1533317507308312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, & Whitlatch CJ (2007). Decision-Making Involvement of Individuals With Dementia. The Gerontologist, 47(6), 810–819. 10.1093/geront/47.6.810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merla C, Wickson-Griffiths A, Kaasalainen S, Dal Bello-Haas V, Banfield L, Hadjistavropoulos T, & Di Sante E (2018). Perspective of Family Members of Transitions to Alternative Levels of Care in Anglo-Saxon Countries. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2018, e4892438. 10.1155/2018/4892438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer OL, Nguyen KH, Dao TN, Vu P, Arean P, & Hinton L (2015). The Sociocultural Context of Caregiving Experiences for Vietnamese Dementia Family Caregivers. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(3), 263–272. 10.1037/aap0000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Lee CS, Whitlatch CJ, & Lyons KS (2018). Involvement of Hospitalized Persons With Dementia in Everyday Decisions: A Dyadic Study. The Gerontologist, 58(4), 644–653. 10.1093/geront/gnw265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lee CS, & Caserta MS (2019). Care Values in Dementia: Patterns of Perception and Incongruence Among Family Care Dyads. The Gerontologist, 59(3), 509–518. 10.1093/geront/gny008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, & Lyons KS (2016). Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia, 15(5), 1141–1157. 10.1177/1471301214555542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoku K, & Shimanouchi S (2014). The Decision-Making and Communication Capacities of Older Adults with Dementia: A Population-Based Study. The Open Nursing Journal, 8, 17–24. 10.2174/1874434620140512001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor D, & Kelson E (2009). Personhood, Dementia and the Use of Formal Support Services. In Decision-making, personhood and dementia: Exploring the interface (pp. 159–171). Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Orfei MD, Blundo C, Celia E, Casini AR, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G, & Varsi AE (2010). Anosognosia in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Alzheimer’s Disease: Frequency and Neuropsychological Correlates. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12), 1133–1140. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsulic-Jeras S, Whitlatch CJ, Szabo SM, Shelton EG, & Johnson J (2019). The SHARE program for dementia: Implementation of an early-stage dyadic care-planning intervention. Dementia, 18(1), 360–379. 10.1177/1471301216673455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2014). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). Sage Publishing. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-research-evaluation-methods/book232962 [Google Scholar]

- Reamy AM, Kim K, Zarit SH, & Whitlatch CJ (2013). Values and Preferences of Individuals With Dementia: Perceptions of Family Caregivers Over Time. The Gerontologist, 53(2), 293–302. 10.1093/geront/gns078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena-Komuro M-C, Marshall C, Bond R, Russell L, Greaves C, Moore K, & Agustus J (2020). Altered Time Awareness in Dementia. Front. Neurol, 11(291), 1–12. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rev.com. (n.d.). Transcribe Speech to Text. Rev. Retrieved October 20, 2022, from https://www.rev.com/

- Roy N, Dubé R, Després C, Freitas A, & Légaré F (2018). Choosing between staying at home or moving: A systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults. PLoS ONE, 13(1). 10.1371/journal.pone.0189266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski RA, Ponnala S, Younan L, Weiler DT, Bykovskyi AG, & Werner NE (2021). A process-based approach to exploring the information behavior of informal caregivers of people living with dementia. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 145, 104341. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsi K, & Manthorpe J (2013). Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 949–961. 10.1017/S1041610213000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samus QM, Black BS, Bovenkamp D, Buckley M, Callahan C, Davis K, Gitlin LN, Hodgson N, Johnston D, Kales HC, Karel M, Kenney JJ, Ling SM, Panchal M, Reuland M, Willink A, & Lyketsos CG (2018). Home is where the future is: The BrightFocus Foundation consensus panel on dementia care. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(1), 104–114. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford S, Naglie G, Cameron DH, & Rapoport MJ (2020). Subjective Experiences of Driving Cessation and Dementia: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Literature. Clinical Gerontologist, 43(2), 135–154. 10.1080/07317115.2018.1483992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, & Wendler D (2006). The Accuracy of Surrogate Decision Makers: A Systematic Review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(5), 493–497. 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smebye KL, Kirkevold M, & Engedal K (2012). How do persons with dementia participate in decision making related to health and daily care? A multi-case study. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 241. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong A, Au ST, Kyaw BM, Theng YL, & Tudor Car L (2020). Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 61. 10.1186/s12877-020-1454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiulis E, Rapoport MJ, Sivajohan B, Naglie G, & on behalf of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging Driving and Dementia Team. (2020). The Paradox of Dementia and Driving Cessation: “It’s a Hot Topic,” “Always on the Back Burner.” The Gerontologist, 60(7), 1261–1272. 10.1093/geront/gnaa034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, & Logsdon RG (1991). Identifying pleasant activities for Alzheimer’s disease patients: The pleasant events schedule-AD. The Gerontologist, 31(1), 124–127. 10.1093/geront/31.1.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Crotty BH, O’Brien J, Dierks MM, Lipsitz L, & Safran C (2017). Addressing the Challenges of Aging: How Elders and Their Care Partners Seek Information. The Gerontologist, 57(5), 955–962. 10.1093/geront/gnw060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SC, Murphy E, Devane D, Sampson EL, Connolly S, Carney P, & O’Shea E (2021). Palliative care interventions in advanced dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9. 10.1002/14651858.CD011513.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington KT, Meadows SE, Elliott SG, & Koopman RJ (2011). Information needs of informal caregivers of older adults with chronic health conditions. Patient Education and Counseling, 83(1), 37–44. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner NE, Stanislawski B, Marx KA, Watkins DC, Kobayashi M, Kales H, & Gitlin LN (2017). Getting what they need when they need it. Identifying barriers to information needs of family caregivers to manage dementia-related behavioral symptoms. Applied Clinical Informatics, 8(1), 191–205. 10.4338/ACI-2016-07-RA-0122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF, & Tucke SS (2005). Measuring the Values and Preferencesfor Everyday Care of Persons With Cognitive Impairment and Their Family Caregivers. The Gerontologist, 45(3), 370–380. 10.1093/geront/45.3.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter L, & Parker B (2007). Current health and preferences for life-prolonging treatments: An application of prospect theory to end-of-life decision making. Social Science & Medicine, 65(8), 1695–1707. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.