Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) frequency and clinical characteristics among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or spondyloarthritis (SpA) who receive biological treatments.

Patients and methods

The observational study was conducted with patients from the TReasure database, a web-based prospective observational registry collecting data from 17 centers across Türkiye, between December 2017 and June 2021. From this database, 3,147 RA patients (2,502 males, 645 females; median age 56 years; range, 44 to 64 years) and 6,071 SpA patients (2,709 males, 3,362 females; median age 43 years; range, 36 to 52 years) were analyzed in terms of viral hepatitis, patient characteristics, and treatments used.

Results

The screening rate for HBV was 97% in RA and 94.2% in SpA patients. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity rates were 2.6% and 2%, hepatitis B surface antibody positivity rates were 32.3% and 34%, hepatitis B core antibody positivity rates were 20.3% and 12.5%, HBV DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) positivity rates were 3.5% and 12.5%, and antibody against HCV positivity rates were 0.8% and 0.3% in RA and SpA patients, respectively. The HBsAg-positive patients were older and had more comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. In addition, rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity was more common in HBsAg-positive cases. The most frequently prescribed biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs were adalimumab (28.5%), etanercept (27%), tofacitinib (23.4%), and tocilizumab (21.5%) in the RA group and adalimumab (48.1%), etanercept (31.4%), infliximab (22.6%), and certolizumab (21.1%) in the SpA group. Hepatitis B reactivation was observed in one RA patient during treatment, who received rituximab and prophylaxis with tenofovir.

Conclusion

The epidemiological characteristics of patients with rheumatic diseases and viral hepatitis are essential for effective patient management. This study provided the most recent epidemiological characteristics from the prospective TReasure database, one of the comprehensive registries in rheumatology practice.

Keywords: HBV, HCV, rheumatic diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, TReasure, viral hepatitis, viral reactivation.

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a major public health problem causing significant mortality and morbidity worldwide. Accordingly, one-third of individuals in the world had been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), and these viruses are responsible for approximately 90% of the 1.4 million deaths due to viral hepatitis.[1] Recent epidemiological data on HBV and HCV in Türkiye revealed that the seroprevalence rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibody against HCV (anti-HCV) were 4% and 1%, respectively, and seropositivity rates for hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) were 31.9% and 30.6%, respectively.[2] Additionally, one of the biggest concerns about viral hepatitis is the asymptomatic infections that remain undiagnosed.

Viral hepatitis, either diagnosed or undiagnosed, is a severe risk to patients with rheumatic diseases, particularly taking biological drugs like anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Furthermore, it is well established that immunosuppressive treatment is closely associated with viral reactivation in rheumatic diseases, and professional organizations like the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases strongly recommend screening these patients for viral hepatitis before the initiation of immunosuppressive treatments.[3,4] A previous multicenter nationwide study conducted in Türkiye reported that the HBsAg positivity was determined in 2.3% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 3% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and the anti-HCV positivity was detected in 1.1% of patients in each group.[5] Given these rates, viral hepatitis is still considered a potential threat to patients with rheumatic diseases, specifically for treatment-related viral reactivation. Nevertheless, data on this topic is not satisfactory in Türkiye. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the serologic Hepatitis B and C frequency and clinical characteristics among our patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and receive biological treatments based on this background.

Patients and Methods

Study population

This observatinal study was conducted as a secondary analysis of the TReasure registry database. TReasure database is a web-based prospective observational registry collecting data from 17 centers in various geographical regions of Türkiye and includes patients with RA and spondyloarthritis (SpA). Details of the TReasure database were previously published.[6]

The data collection was started on December 2017 and ended on June 2021. At the time of the analysis, the registry database included 3,147 RA patients (2,502 males, 645 females; median age 56 years; range, 44 to 64 years) and 6,071 SpA patients (2,709 males, 3,362 females; median age 43 years; range, 36 to 52 years). The 1987 American Colleague of Rheumatology (ACR)[7] and 2010 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR)/ACR classification criteria[8] for the diagnosis of SpA, modified New York criteria,[9] the 2009 EULAR classification criteria for axial SpA[10] and peripheral SpA,[11] Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for nonradiological axial SpA,[12] and CASPAR (Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria[13] were utilized in the TReasure registry. Additionally, peripheral joint involvement or axial involvement for the diagnosis of enteropathic arthritis and Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis was included in the TReasure registry.

Demographic and clinical features of inflammatory arthritis

In this study, demographic and clinical data of RA and SpA patients were evaluated and compared between the diagnostic subgroups according to the seropositivity of HBV and HCV. Demographic data included sex, current age, age at diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), and presence of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia, coronary arterial disease (CAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma. Clinical data included the disease and symptom durations, RF (Immage 800; Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, and human leukocyte antigen-B27 positivity, serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, Visual Analog Scale assessments of pain, Health Assessment Questionnaire scores, number of swollen and tender joints, composite disease activity measures with Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28)-ESR and DAS28-CRP, Simplified Disease Activity Index, Clinical Disease Activity Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)-ESR, ASDAS-CRP, and the last prescribed biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) at the last visit.

Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus

Considering the recommendations of the Turkish Rheumatology Association guideline for viral hepatitis screening before biologic agent use in patients with rheumatic diseases, the serological tests were performed before bDMARD treatment.[13] HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs tests were evaluated for HBV. HBV DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) was studied in HBsAg positive patients. Anti-HCV antibody has been studied for HCV. If HBsAg or anti-HBc was positive, the patient was referred to the gastroenterology or infectious diseases department to start antiviral prophylaxis. Entecavir or tenofovir was started for HBV prophylaxis. The clinical and serological HBV reactivation in the follow-up of the patients was evaluated by looking at the HBV DNA viral loads.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and median and interquartile range for continuous variables. Categorical and continuous variables were compared between independent groups using the chi-square test, where Fisher exact test was used if the expected value was <5 and Pearson’s chi-square test was used if the expected value was >5, and the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. A type-1 error level of 5% was considered the statistical significance threshold (p<0.05).

Results

Study population

More than half of the patients with SpA were diagnosed with AS (57.4%), followed by PsA (12.3%), peripheral SpA (9.8%), axial nonradiographic SpA (8.2%), and enteropathic SpA (2.8%), and 9.6% of the cases were nonclassified. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with RA and SpA are presented in Table 1. Accordingly, there was a female predominance in the RA group (p<0.001). Patients with RA were older (p<0.001), had more prolonged disease (p<0.001) and symptom (p<0.001) durations, had more comorbidities (p<0.001), pain scores (p<0.001), number of swollen (p<0.001) and tender (p<0.001) joints, and higher ESR (p<0.001) and CRP (p<0.001) levels.

Table 1. Basal demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with RA and SpA.

| RA (n=3,147) | SpA (n=6,071) | |||||||

| n | % | Median | IQR | n | % | Median | IQR | |

| Age (year) | 56 | 44-64 | 43 | 36-52 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 2,502 | 79.5 | 2,709 | 44.6 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 43 | 32-52 | 33 | 26-42 | ||||

| Disease duration (month) | 134 | 79-207 | 102 | 55-159 | ||||

| Symptom duration (month) | 152 | 98-247 | 152 | 91-232 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.51 | 24.03-31.64 | 26.78 | 23.71-30.11 | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 960 | 31.2 | 920 | 15.6 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 383 | 12.5 | 453 | 7.7 | ||||

| Obesity | 1,045 | 34.6 | 1,502 | 26 | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 504 | 17.6 | 682 | 12.8 | ||||

| CAD | 169 | 5.8 | 123 | 2.6 | ||||

| COPD | 60 | 2.1 | 36 | 0.6 | ||||

| Asthma | 229 | 7.9 | 234 | 4.1 | ||||

| Malignity | 55 | 1.8 | 52 | 0.9 | ||||

| RF positivity | 1,892 | 66.9 | - | - | ||||

| Anti-CCP positivity | 1,397 | 59.2 | - | - | ||||

| HLA-B27 | - | - | 1889 | 51.7 | ||||

| ESR (mm/h) | 33 | 18-53 | 22 | 10-39 | ||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 14 | 5.57-34 | 11 | 3.995-24.7 | ||||

| VAS global | 70 | 50-80 | 70 | 50-80 | ||||

| VAS pain | 75 | 60-85 | 70 | 50-80 | ||||

| VAS fatigue | 70 | 50-80 | 70 | 50-80 | ||||

| HAQ | 0.8 | 0.5-1.25 | 0.6 | 0.35-0.85 | ||||

| Number of swollen joints | 4 | 1-6 | 0 | 0-0 | ||||

| Number of tender joints | 6 | 3-10 | 0 | 0-2 | ||||

| DAS28-ESR | 4.88 | 3.67-5.86 | - | - | ||||

| DAS28-CRP | 4.34 | 3.14-5.4 | - | - | ||||

| CDAI | 23.5 | 16-31 | - | - | ||||

| SDAI | 40 | 26.83-63 | - | - | ||||

| BASDAI | - | - | 6 | 4.4-7 | ||||

| BASFI | - | - | 4.3 | 2.7-6 | ||||

| ASDAS-ESR | - | - | 3.16 | 2.51-3.82 | ||||

| ASDAS-CRP | - | - | 3.535 | 2.855-4.19 | ||||

| RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; SpA: Spondyloarthritis; IQR: Interquartile range; BMI: Body mass index; CAD: Coronary arterial disease; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RF: Rheumatoid factor; Anti-CCP: Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; HLA-B27: Human leukocyte antigen-B27; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; DAS: Disease Activity Score; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Scores. | ||||||||

Prevalence of HBV and HCV serology

Table 2 summarizes the serological analyses in the study group. Accordingly, 97% (n=2,809) of the patients in the RA group and 94.2% (n=5130) in the SpA group had HBV testing. HBsAg positivity rates were 2.6% (n=71) and 2% (p=99), anti-HBs positivity rates were 32.3% (n=876) and 34% (n=1,663, p=0.147), anti-HBc positivity rates were 20.3% (n=480) and 12.5% (n=524, p<0.001), HBV DNA positivity rates were 3.5% (n=16) and 12.5% (n=35, p<0.001), and anti-HCV positivity rates were 0.8% (n=22) and 0.3% (n=16, p=0.005) in the RA and SpA groups, respectively.

Table 2. Serological analyses in the study groups.

| RA group | SpA group | |||||

| n | n | % | n | n | % | |

| Hepatitis testing | 2,896 | 2,809 | 97.0 | 5,444 | 5,130 | 94.2 |

| HBsAg positivity | 2,750 | 71 | 2.6 | 5,017 | 99 | 2 |

| Anti-HBs positivity | 2,708 | 876 | 32.3 | 4,893 | 1,663 | 34 |

| Anti-HBc positivity | 2,362 | 480 | 20.3 | 4,194 | 524 | 12.5 |

| HBV DNA positivity | 454 | 16 | 3.5 | 637 | 35 | 5.5 |

| Anti-HCV positivity | 2,602 | 22 | 0.8 | 4,627 | 16 | 0.3 |

| RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; SpA: Spondyloarthritis; HBsAg; Hepatitis B surface antigen; Anti-HBs; Hepatitis B surface antibody; Anti-HBc: Hepatitis B core antibody; HBV DNA; Anti-HCV, antibody against hepatitis C virus. | ||||||

The comparison of clinical features with regard to HBV and HCV serologies

The comparisons of patient characteristics between RA patients with and without HBsAg positivity revealed that HBsAg-positive patients were older (median 61 vs. 56 years, p=0.001) and had a more advanced age at diagnosis (median 49 vs. 43 years, p<0.001, Table 3). RF positivity was more frequent in HBsAg-positive cases (80% vs. 66.9%, p=0.026) regarding rheumatism biomarkers. When the demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between anti-HBc positivity subgroups, the proportion of females was higher in the anti-HBc-negative group, but the comorbidities including hypertension (p<0.001), hyperlipidemia (p=0.022), CAD (p=0.003), COPD (p=0.003), and asthma (p=0.033) were more frequent in the anti-HBc-positive patients. There was no difference in disease activity index according to HBsAg and anti-HBc positivity.

Table 3. Demographic and clinical data of RA patients.

| HBsAg (-) (n=2,679) | HBsAg (+) (n=71) | Anti-HBc (-) (n=1,882) | Anti-HBc (+) (n=480) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | p | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | p | ||||||||||

| Age (year) | n | % | 56 | 44-64 | n | % | 61 | 54-67 | 0.001 | n | % | 54 | 42-62 | n | % | 61 | 54-69 | <0.001 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 2,160 | 80.6 | 54 | 76.1 | 0.337 | 1,530 | 81.3 | 371 | 77.3 | 0.048 | ||||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 43 | 32-52 | 49 | 41-56 | <0.001 | 41 | 30-51 | 48 | 40-56 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Disease duration (monts) | 134 | 79-207 | 122 | 82.5-195 | 0.457 | 127 | 74-200 | 140 | 82-232 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Symptom duration (month) | 152 | 98-249 | 139 | 103-249 | 0.913 | 147 | 91-237 | 176 | 103-261 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.55 | 24.14-31.96 | 28.54 | 24.79-31.38 | 0.455 | 2,7.24 | 23.88-31.59 | 28.23 | 24.77-32.02 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||

| RF positivity | 1,667 | 66.9 | 52 | 80 | 0.026 | 1143 | 65.5 | 316 | 69.9 | 0.074 | ||||||||||||

| Anti-CCP positivity | 1,219 | 59.2 | 38 | 67.9 | 0.195 | 863 | 58.9 | 230 | 61.3 | 0.393 | ||||||||||||

| Abatacept | 384 | 14.3 | 10 | 14.1 | 0.953 | 248 | 13.2 | 75 | 15.6 | 0.164 | ||||||||||||

| Adalimumab | 782 | 29.2 | 17 | 23.9 | 0.337 | 549 | 29.2 | 137 | 28.5 | 0.786 | ||||||||||||

| Anakinra | 23 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.433 | 17 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.287 | ||||||||||||

| Canakinumab | 5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.716 | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.986 | ||||||||||||

| Etanercept | 724 | 27 | 19 | 26.8 | 0.96 | 539 | 28.6 | 105 | 21.9 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||

| Golimumab | 179 | 6.7 | 3 | 4.2 | 0.411 | 131 | 7 | 23 | 4.8 | 0.086 | ||||||||||||

| Infliximab | 228 | 8.5 | 5 | 7 | 0.661 | 142 | 7.5 | 44 | 9.2 | 0.239 | ||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 562 | 21 | 10 | 14.1 | 0.158 | 385 | 20.5 | 111 | 23.1 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||

| Secukinumab | 16 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.514 | 10 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.442 | ||||||||||||

| Certolizumab | 327 | 12.2 | 4 | 5.6 | 0.093 | 244 | 13 | 37 | 7.7 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Tofacitinib | 661 | 24.7 | 16 | 22.5 | 0.68 | 462 | 24.5 | 128 | 26.7 | 0.339 | ||||||||||||

| Tocilizumab | 610 | 22.8 | 7 | 9.9 | 0.01 | 450 | 23.9 | 106 | 22.1 | 0.4 | ||||||||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1,913 | 71.4 | 45 | 63.4 | 0.14 | 1,333 | 70.8 | 348 | 72.5 | 0.471 | ||||||||||||

| Leflunomide | 1,543 | 57.6 | 32 | 45.1 | 0.035 | 1,038 | 55.2 | 287 | 59.8 | 0.068 | ||||||||||||

| Methotrexate | 2,209 | 82.5 | 55 | 77.5 | 0.276 | 1,554 | 82.6 | 389 | 81 | 0.433 | ||||||||||||

| Sulfasalazine | 1,301 | 48.6 | 36 | 50.7 | 0.722 | 884 | 47 | 242 | 50.4 | 0.177 | ||||||||||||

| Steroid | 2,295 | 85.7 | 58 | 81.7 | 0.347 | 1,605 | 85.3 | 417 | 86.9 | 0.375 | ||||||||||||

| RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; HBsAg; Hepatitis B surface antigen; Anti-HBc: Hepatitis B core antibody; IQR: Interquartile range; Q: Quartile; BMI: Body mass index; RF: Rheumatoid factor; Anti-CCP: Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 4 presents the comparisons of demographic and clinical data between seropositive and seronegative subgroups among SpA patients. Accordingly, the ages at diagnosis (p=0.043) and the symptom durations (p=0.003) were significantly higher in the HBsAg-positive group. The comparisons according to the anti-HBc positivity revealed that the proportion of females (p=0.039), age (p<0.001), age at diagnosis (p<0.001), disease (p<0.001) and symptom (p<0.001) durations, BMI (p<0.001), the presence of hypertension (p<0.001), diabetes mellitus (p<0.001), obesity (p=0.003), hyperlipidemia (p<0.001), CAD (p<0.001), COPD (p<0.001), asthma (p=0.002), and malignities (p<0.001), and the BASDAI scores (p=0.012) were all significantly higher in the anti-HBc-positive group.

Table 4. Demographic and clinical data of spondyloarthritis patients.

| HBsAg (-) (n=4,918) | HBsAg (+) (n=99) | Anti-HBc (-) (n=3,670) | Anti-HBc (+) (n=524) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | p | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Q1-Q3 | p | ||||||||||

| Age (year) | n | % | 43 | 36-52 | n | % | 46 | 38-52 | 0.097 | n | % | 42 | 35-50 | 51 | 43-59 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 2,212 | 45 | 47 | 47.5 | 0.621 | 1,638 | 44.6 | 259 | 49.4 | 0.039 | ||||||||||||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 33 | 26-42 | 37 | 26-45 | 0.043 | 33 | 26-41 | 39 | 32-48 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Disease duration (month) | 98 | 54-159 | 98 | 54-149 | 0.809 | 94 | 50-152 | 115 | 61-183 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Symptom duration (month) | 147 | 91-225 | 161.5 | 130-258.5 | 0.003 | 147 | 87-220 | 174 | 110-261 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.81 | 23.67-30.36 | 27.78 | 24.89-31.24 | 0.063 | 26.71 | 23.53-30.12 | 27.965 | 24.86-31.21 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| HLA-B27 | 1,511 | 50.8 | 29 | 59.2 | 0.246 | 1,159 | 50.7 | 132 | 51.4 | 0.835 | ||||||||||||

| Abatacept | 18 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.546 | 14 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.494 | ||||||||||||

| Adalimumab | 2,420 | 49.2 | 40 | 40.4 | 0.083 | 1,768 | 48.2 | 282 | 53.8 | 0.016 | ||||||||||||

| Anakinra | 27 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.46 | 21 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.6 | 0.999 | ||||||||||||

| Canakinumab | 16 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.57 | 12 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.6 | 0.378 | ||||||||||||

| Etanercept | 1,532 | 31.2 | 33 | 33.3 | 0.643 | 1,133 | 30.9 | 159 | 30.3 | 0.806 | ||||||||||||

| Golimumab | 798 | 16.2 | 12 | 12.1 | 0.272 | 592 | 16.1 | 84 | 16 | 0.953 | ||||||||||||

| Infliximab | 1,136 | 23.1 | 20 | 20.2 | 0.498 | 832 | 22.7 | 135 | 25.8 | 0.116 | ||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 11 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.638 | 6 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.6 | 0.058 | ||||||||||||

| Secukinumab | 524 | 10.7 | 15 | 15.2 | 0.153 | 393 | 10.7 | 72 | 13.7 | 0.039 | ||||||||||||

| Certolizumab | 1,076 | 21.9 | 22 | 22.2 | 0.935 | 798 | 21.7 | 112 | 21.4 | 0.848 | ||||||||||||

| Tofacitinib | 35 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 28 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.8 | 0.999 | ||||||||||||

| Tocilizumab | 28 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.452 | 19 | 0.5 | 5 | 1 | 0.215 | ||||||||||||

| Ustekinumab | 73 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.664 | 54 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.9 | 0.445 | ||||||||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 528 | 10.7 | 8 | 8.1 | 0.397 | 371 | 10.1 | 64 | 12.2 | 0.139 | ||||||||||||

| Leflunomide | 417 | 8.5 | 5 | 5.1 | 0.224 | 298 | 8.1 | 61 | 11.6 | 0.007 | ||||||||||||

| Methotrexate | 1,555 | 31.6 | 27 | 27.3 | 0.357 | 1,129 | 30.8 | 168 | 32.1 | 0.548 | ||||||||||||

| Sulfasalazine | 2,974 | 60.5 | 61 | 61.6 | 0.818 | 2,197 | 59.9 | 317 | 60.5 | 0.782 | ||||||||||||

| Steroid | 1,485 | 30.2 | 23 | 23.2 | 0.135 | 1,103 | 30.1 | 154 | 29.4 | 0.756 | ||||||||||||

| HBsAg; Hepatitis B surface antigen; Anti-HBc: Hepatitis B core antibody; IQR: Interquartile range; Q: Quartile; BMI: Body mass index; HLA-B27: Human leukocyte antigen-B27. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

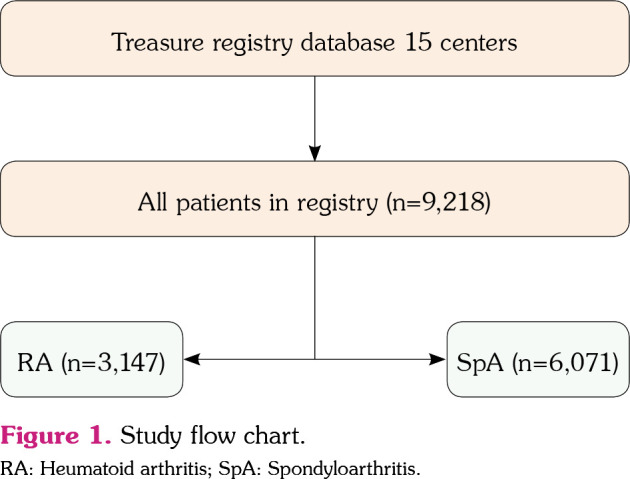

The most frequently prescribed bDMARDs were adalimumab (28.5%), etanercept (27%), tofacitinib (23.4%), and tocilizumab (21.5%) in the RA group, whereas adalimumab (48.1%), etanercept (31.4%), infliximab (22.6%), and certolizumab (21.1%) were the most frequently used in the SpA group (Figure 1). Comparison of the last prescribed medication in patients with RA showed that tocilizumab (p=0.01) and leflunomide was more recommended to HBsAg-negative patients, steroids were more prescribed to anti-HBs-positive patients, and etanercept (p=0.003) and certolizumab (p=0.001) were more prescribed to anti-HBc-negative cases (Table 3). Comparisons among SpA patients revealed that rituximab (p=0.001) and sulfasalazine (p=0.011) were more prevalent in the anti-HBs-positive group, and adalimumab (p=0.016), secukinumab (p=0.039), and leflunomide (p=0.007) were more commonly prescribed to anti-HBc-positive cases (Table 4).

Figure 1. Study flow chart. RA: Heumatoid arthritis; SpA: Spondyloarthritis.

Hepatitis B virus reactivation during biological DMARDs

Hepatitis B virus reactivation was observed in one patient with RA during treatment. The patient (71-year-old male) was HBsAg negative and anti-HBs positive before treatment. Tenofovir prophylaxis was started for the patient for whom rituximab treatment was planned. In the seventh year of treatment, HBV activation developed.

Figure 2. Prescription proportions of mediations in the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis (SpA) groups.

Discussion

Hepatitis B virus infections are commonly seen in patients with rheumatic diseases and are an important risk factor, mainly if the patient receives biological drugs.[14] However, epidemiological data on HBV infections, particularly the reactivation during biological treatment, is not satisfactory despite its importance. This study evaluated the general characteristics of RA and SpA patients receiving biological medications, identified the essential differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between serologically positive and negative patients, and retrospectively analyzed an extensive series of registry records for the viral infection reactivation in rheumatic disorders. Based on our findings, the HBV testing rates were satisfactory in both disease groups, but the 97% testing rate in the RA group was significantly higher than the 94.2% in the SpA group. Data for hepatitis screening in rheumatic disseases are scare, it was reported to be approximately 69% in a study.[15] Thus, the results of our study were considered adequate for determining the epidemiological characteristics.

The HBV seroprevalence was reported about 3% globally, but the rate of chronic HBV infections was slightly higher in Türkiye, which was reported by a previous multicenter study as 4% for HBsAg positivity and 30.6% for anti-HBc positivity.[2] On the contrary, the HCV prevalence is lower than the world data, with about 3% in the world but 0.3-1.7% in Türkiye.[16] The data on the HBV and HCV infections in rheumatic diseases are also limited. Ayar et al.[17] reported in their study on RA patients that the prevalence of naturally immune patients, anti-HBc IgG positivity only, and chronic HBV infection was 25.7%, 4.4%, and 3.5%, respectively. In another study, Dagli and Aksoy[18] reported that the prevalence of anti-HBs was 22.4%, anti-HCV was 1.5%, and isolated anti-HBc IgG was 23.8% in patients with AS. In a more extensive multicenter study including 1,517 RA and 886 AS patients in our country by Yilmaz et al.,[5] the HBsAg prevalence was reported as 2.3% in RA and 3% in AS patients, and the anti-HCV prevalence was 1.1% in both groups. In our study, the HBsAg positivity was similar to those reported by previous studies, particularly with the nationally representative multicenter large-scale studies. Still, the anti-HCV positivity rates were slightly lower. This difference may be associated with our study population, which was confined to only those receiving biological treatment.

The comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics of patients between serologically positive and negative groups revealed that the patients with HBsAg and anti-HBc positivity were older than the negative patients. This difference was also stated in Yilmaz et al.’s[5] study, in which HBsAg and anti-HCV-positive patients were older than the negative patients. Furthermore, although not conducted in rheumatic diseases, studies by Köse et al.[19] and Guclu et al.[20] also reported that seropositive patients were older in our country. Other than age, the comorbidities tended to be more frequent in serologically positive patients. Several population-based studies revealed increased rates for nonhepatic comorbid conditions among patients with chronic HBV infections, such as diabetes, CAD, atherosclerotic diseases, and kidney disorders, and our results were in conjunction with this evidence.[21]

In our study, the treatment choice in RA and SpA and the proportions of bDMARDs in each disease were significantly different, except for anakinra and canakinumab prescribed to patients at similar rates. Biological drugs, such as TNF inhibitors, B-cell/T-cell/IL-6 blockers, or JAK (Janus kinase) inhibitors used in rheumatic diseases, are safe and effective medications.[22] However, the treatment choice is based on various factors, including guideline recommendations, patient characteristics, previous medications, and availability and access to treatment. The drug choice differences in our study between RA and SpA should be cautiously interpreted as the results were only limited to the last prescribed treatment and did not include any data about the previous therapies. A switch between two bDMARDs is frequently seen, particularly once an ineffectiveness, adverse event, and patient or physician choice occurs.[22,23] A study by Kalyoncu et al.,[24] also conducted on the TReasure database, evaluated the switches in the bDMARDs in RA and SpA patients and revealed that the main reasons for switching were ineffectiveness and adverse or side effects, as anticipated. Although the changes in treatment choice were not assessed in this study, the most frequently prescribed drugs were generally similar to the TReasure database's previous assessments.

Retrospective screening of the database found only one patient with HBV reactivation in the study population. The most feared and known risk drug for HBV reactivation is rituximab. Interestingly, there was no difference in rituximab use preferences in RA patients according to HBsAg or anti-HBc positivity. The fact that only one patient had reactivation in the results of our study suggests that there is no obstacle in choosing rheumatology physicians in patients who received appropriate prophylaxis.

Viral reactivation is a severe concern in rheumatic diseases, primarily when the biological drugs are used for treatment. These drugs can effectively suppress the disease activity but may also cause severe adverse events like latent tuberculosis, demyelinating diseases, or HBV or HCV reactivation.[25,26] HBV reactivation is classically defined as the progression of HBV DNA positivity in negative patients or an increase of HBV DNA levels by more than 1 log10 compared to baseline.[27] In addition, the progression of active necroinflammatory liver disease characterized by five times higher levels of ALT (alanine transaminase) and HBeAg reversion is also classified as HBV reactivation. The HCV reactivation is called a two to three times increase in ALT levels and more than 1 log10 increase in HCV RNA (ribonucleic acid) levels.[13] Given the severity of the viral reactivation under immunosuppressive treatments, screening and serological assessment of all patients that will receive bDMARDs are recommended. Karadağ et al.[13] published the guideline for viral hepatitis screening before biologic agent initiation in patients with rheumatic diseases and underlined the essential key points for our population. Accordingly, four risk groups were defined, and routine oral antiviral prophylaxis against HBV was recommended in higher-risk groups. Vaccination is also recommended in patients with negative markers. Unfortunately, prophylaxis against HCV reactivation is not available.

In conclusion determining the epidemiological characteristics for patients with rheumatic diseases and viral hepatitis is essential to identify the roadmaps for more effective interventions or to imply the clinical characteristics to be considered during patient management. This study provided the most recent epidemiological characteristics from the prospective TReasure database, one of the comprehensive registries in rheumatology practice. According to the results of our study, it can be suggested that there is a low risk in the choice of treatment by the rheumatologist in patients who receive appropriate prophylaxis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to study design, material preparation, data collection, analysis, interpretation and writting of the manuscript and take full responsibility for the integrity of the study and the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial Disclosure: The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

References

- 1.Jefferies M, Rauff B, Rashid H, Lam T, Rafiq S. Update on global epidemiology of viral hepatitis and preventive strategies. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6:589–599. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tozun N, Ozdogan O, Cakaloglu Y, Idilman R, Karasu Z, Akarca U, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections and risk factors in Turkey: A fieldwork TURHEP study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. lEectronic address: easloffice@easloffice. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560–1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.29800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yılmaz N, Karadağ Ö, Kimyon G, Yazıcı A, Yılmaz S, Kalyoncu U, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: A multicenter countrywide study. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:51–54. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheumatol.2014.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalyoncu U, Taşcılar EK, Ertenli Aİ, Dalkılıç HE, Bes C, Küçükşahin O, et al. Methodology of a new inflammatory arthritis registry: TReasure. Turk J Med Sci. 2018;48:856–861. doi: 10.3906/sag-1807-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Chou CT, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): Validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–783. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, CASPAR Study Group Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karadağ Ö, Kaşifoğlu T, Özer B, Kaymakoğlu S, Kuş Y, İnanç M, et al. Romatolojik hastalarda biyolojik ilaç kullanımı öncesi (viral) hepatit tarama kılavuzu. RAED Dergisi. 2015;7:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ditto MC, Parisi S, Varisco V, Talotta R, Batticciotto A, Antivalle M, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and risk of reactivation in rheumatic population undergoing biological therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toka B, Eminler AT, Gönüllü E, Tozlu M, Uslan MI, Parlak E, et al. Rheumatologists' awareness of hepatitis B reactivation before immunosuppressive therapy. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:2077–2085. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04437-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Çildağ S, Şentürk T. Correlation between hepatitis B and C positivity and rheumatoid factor levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Viral Hepatitis Journal. 2014;20:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayar K, Asan A, Onart O, Türk M, Demıray TD. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus serological groups in rheumatoid arthritis and association of previous hepatitis B virus infection with demographic data and parenteral therapies. Turk J Int Med. 2021;3:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dagli O, Kasapoğlu Aksoy M. Ankilozan spondilitli hastalarda hepatit B ve hepatit C enfeksiyonu prevalansı. Ortadoğu Tıp Dergisi. 2018;10:297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köse Ş, Mandıracıoğlu A, Çavdar G, Ulu Y, Türken M, Gözaydın A, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C: A community based study conducted in İzmir, Turkey. Kafkas J Med Sci. 2014;4:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guclu E, Ogutlu A, Karabay O. A study on the agerelated changes in hepatitis B and C virus serology. Eurasian J Med. 2016;48:37–41. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2015.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei MT, Henry L, Nguyen MH. Nonliver comorbidities in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2019;14:126–130. doi: 10.1002/cld.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Favalli EG, Raimondo MG, Becciolini A, Crotti C, Biggioggero M, Caporali R. The management of firstline biologic therapy failures in rheumatoid arthritis: Current practice and future perspectives. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:1185–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MY, Shin JY, Park SY, Kim D, Cha HS, Lee EK. Persistence of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: An analysis of the South Korean National Health Insurance Database. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalyoncu U, Ertenli Aİ, Küçükşahin O, Dalkılıç HE, Erden A, Bes C, et al. Switching between biological DMARDs and associated reasons in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis treatments: TReasure study-real life data. Ulusal Romatoloji Dergisi. 2019;11:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Nam JL, Smolen JS, Buch M, Gossec L, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: A systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:529–535. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT, American Gastroenterological Association Institute American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:215–219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B. S156-65Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl) doi: 10.1002/hep.22945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]